Jones v. Caddo Parish School Board Brief for Appellants

Public Court Documents

April 15, 1974

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Jones v. Caddo Parish School Board Brief for Appellants, 1974. 3bcf2d4d-b99a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/6d2593e8-22e5-4ecc-9887-23e6923298f7/jones-v-caddo-parish-school-board-brief-for-appellants. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

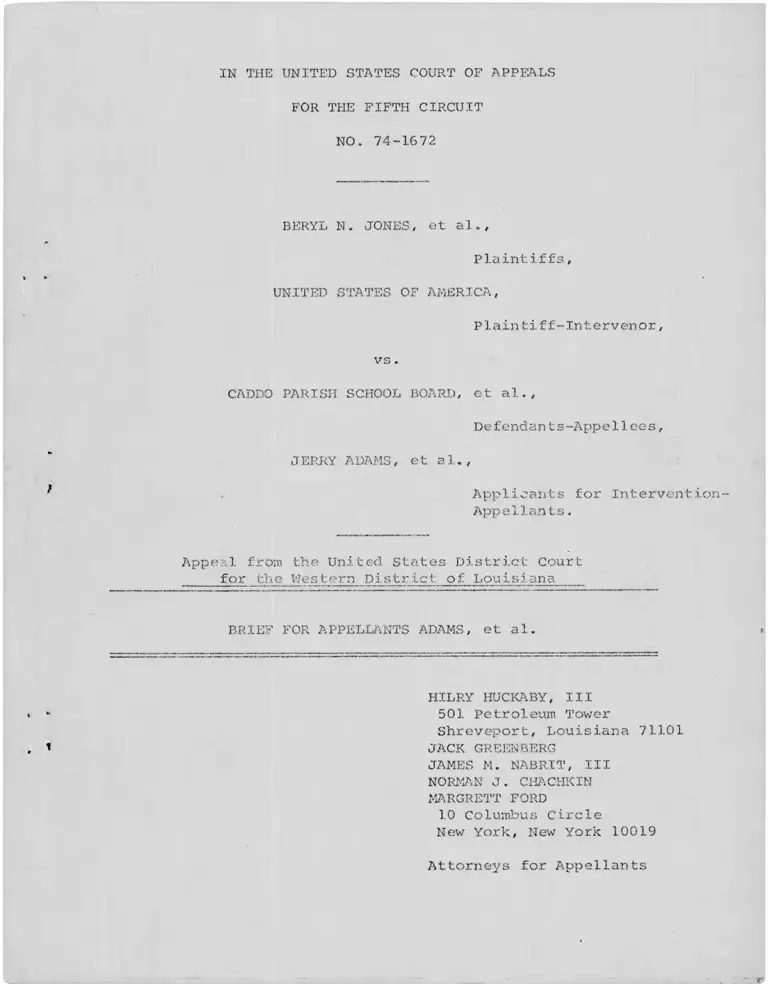

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

NO. 74-1672

BERYL N. JONES, et a'l.. ,

Plaintiffs,

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Plaintiff-Intervenor,

vs.

CADDO PARISH SCHOOL BOARD, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees,

JERRY ADAMS, et al.,

Applicants for Intervention

Appellants.

Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Western District of Louisiana

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS ADAMS, et al.

HILRY HUCKABY, III

501 Petroleum Tower

Shreveport, Louisiana 71101

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

NORMAN J. CHACHKIN

MARGRETT FORD

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Appellants

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

NO. 74-1672

BERYL N. JONES, et al.,

Plaintiffs,

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

vs .

Plaintiff-Intervenor,

CADDO PARISH SCHOOL BOARD, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees,

JERRY AD/aMS , et al.,

Applicants for Intervention-

Appellants .

Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Western District of Louisiana

CERTIFICATE REQUIRED BY LOCAL RULE 13(a)

The undersigned, counsel of record for the applicants for

intervention-appellants, certifies that the following listed

parties have an interest in the outcome of this case. These

representations are made in order that Judges of this Court may

evaluate possible disqualification or recusal pursuant to Local

Rule 13(a) :

1. The original plaintiffs who commenced this action in

1965 include Rev. E. E. Jones, who sued individually and on

behalf of his minor children Beryl N. Jones and Ernest E. Jones,

Jr.; Mrs. Bernice Smith, who sued individually and on behalf of

her minor children Brenda Braggs and Renee Skannal; and Mrs.

Dorothy Saxton, who sued individually and on behalf 0 1 her minor

children Brenda Louise Saxton and Kenneth Saxton. A fourth

original plaintiff, C.C. McLain, was dismissed as a party plain

tiff on his own behalf and on behalf of his minor children on

June 14, 1965.

2. The original plaintiffs above named commenced and

maintained this action as a class aclion pursuant to F.R. Civ. P.

23 on behalf of “other Negro children and their parents in CJiddo

Parish.

3. The United States of America, admitted as a plaintiff-

intervenor in this cause.

4. The defendants are the Caddo Parish School Board, a

public body corporate responsible for the operation of the

public schools of Caddo Parish, Louisiana; and the current

President of the said School Board and Superintendent of the

Caddo Parish Public Schools.

5. Appellants, unsuccessful applicants for intervention

as plaintiffs, are Mrs. Fannie Adams, suing individually and

on behalf of her minor children Jerry Adams, Vicki Adams and

-2-

William Adams; Mrs. Marjorie R. Ford, suing individually and

on behalf of her minor children Tracy Roderick Ford, Vivian

Ray Ford, Toni Lynn Ford and Alan Craig Ford; David L. Roberson,

suing individually and onbehalf of his minor child Kevin Dwayne

Roberson; Rev. Curtis F. Roberson; and Mr. and Mrs. Eddie Clark,

suing individually and on behalf of their minor children Jeanette

Clark, Janet Marie Clark, Azzie Lee Clark and Eddie Clark, Jr.

6. Appellants sought to intervene in this litigation m

order to represent the interests of a class defined as follows:

"present and future black public schoolchildren who are or will

be eligible to attend the public schools of Caddo Parish . . .

[and] parents and guardians of such black public schoolchildren

with the exception of the subclass of such adults who have

accepted the presently operative plan of desegregation and who

do not desire to have its constitutionality determined by this

Court."

({(Ccu/it

NORMAN J. CH^CHKIN

Attorney of Record for

Applicants for Intervention-

Appellants.

-3-

I N D E X

Page

Table of Authorities . ........................... ii

Issues Presented for Review .................... 1

Statement

Background of the C a s e .................... 2

Proceedings for Further Desegregation . . . . 3

Substitution of Counsel and Entry

of Consent Decree .................. 6

The Attempted Intervention ................ 8

ARGUMENT —

I. The District Court Erred in Denying

Intervention.......... ..................10

'A. The interests sought to be represen

ted by the appellants were not ade

quately protected by the original

plaintiffs in the proceedings before

the District C o u r t .................. 10

B. Appellants complied with the require

ments of Hines v. Rapides Parish

School Bd. , supra .................. 13

C. Intervention would have corrected

the error committed by the District

Court in the substitution of counsel . 14

D. The intervention was timely.......... 16

II. This Case Should Be Remanded To Another

District Judge With Instructions To

Disapprove The Biracial Committee Plan . . 20

A. A reversal of the intervention ruling

alone, or with a remand to the District

Court to reconsider its approval of

the biracial committee plan will lead

only to delay and is unnecessary since

the holding and principles of Calhoun

v. Cook, 487 F.2d 680 (5th Cir. 1973),

are so clearly controlling.......... 21

l

I N D E X (continued)

B. This Court should also instruct the

District Court on remand that the

biracial committee plan is unconsti

tutionally insufficient on this

record because it fails to desegre

gate the Caddo Parish public schools . 26

C. This case should be remanded with

instructions that it be transferred

to another district judge . . . . . . 28

oqConclusion.............................. ..

Page

Table of Authorities

Cases:

Alexander v. Holmes County Bd. of Educ., 396 U.S.

19 (1969) . .............................* 19

Allen v. Board of Public Instruction of Broward

County, 432 F.2d 362 (5th Cir. 1970) . . . . 27

Ashback v. Kirtley, 289 F.2d 159 (8th Cir. 1961) 22

Atlantis Development Corp. v. United States,

379 F.2d 818 (5th Cir. 1967).............. 12n

Bradley v. Board of Public Instruction of Pinellas

County, 431 F.2d 1377 (5th Cir. 1970) . . . 27

Brown v. Board of Educ., 347 U.S. 483 (1954) . . 23, 24

Calhoun v. Cook, 487 F.2d 680 (5th Cir. 1973) . . 2, 13, 14,19-20, 21,

Calhoun v. Cook, 469 F.2d 106 7 (5th Cir. 1972) . -an

Cameron v. President & Fellows, 157 F.2d 993

(Ist Cir. 1946) ..........................

16,

22n

xi

Carter v. West Feliciana Parish School Bd.,

396 U.S. 290 (1970)........................ 3, 19

Carter v. WTest Feliciana Parish School Bd.,

396 U.S. 226 (1969)........................ 19

Cascade Natural Gas Corp. v. El Paso Natural Gas

Co., 386 U.S. 129 (1967) ............ .. 12n, 17

Cisneros v. Corpus Christi Independent School

Dist., 467 F.2d 142 (5th Cir. 1972) . . . . . 27

Cohen v. Young, 127 F.2d 721 (6th Cir. 1942) . . . 22

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1 (1958) ............... 24

Davis v. Board of School Comm1rs of Mobile, 402 .

U.S. 33 (1971) ......................... 27

Dowell v. School Bd. of Oklahoma City, 430 F.2d

865 (10th Cir. 1970; ...................... 12

Ellis v. Board of Public Instruction of Orange

County, 465 F.2d 878 (5th Cir. 1972), cert,

denied, 410 U.S. 966 (1973)................ 18

Flax v. Potts, 313 F.2d 284 (5th Cir. 1963) . . . 23, 25, 28

Hall v. St. Helena Parish School Bd., 417 F.2d

801 (5th Cir.), cert, denied, 396 U.S.

904 (1969) . . . . . ................ . . . 3

Hatton v. County Bd. of Educ. of Maury County,

422 F.2d 457 (6th Cir. 1970) .............. 11

Henry v. Clarksdale Municipal Separate School

Dist., 433 F.2d 387 (5th Cir. 1970) . . . . . 27

Hines v. Rapides Parish School Bd., 479 F.2d

762 (5th Cir. 1973)........................ 8, 10, 13, 14

Jones v. Caddo Parish School Bd., 421 F.2d

313 (5th Cir. 1970)........................ 3

Lee v. Macon County Bd. of Educ., 482 F.2d

1253 (5th Cir. 1973) ...................... 13

Norman v. McKee, 431 F.2d 769 (9th Cir. 1970) . . 22

Table of Authorities (continued)

Page

iii

Northcross v. Board of Educ. of Memphis, 412

U.S. 427 (1973)............................ 30

Pate v. Dade County School Bd., 434 F.2d 1141

(5th Cir. 1970)............................ 27

Sertic v. Cuyahoga Lake, etc., Carpenters Dist.

Council, 459 F.2d 579 (6th Cir. 1972) . . . . 22

Sheffield v. Itawamba County Bd. of Supervisors,

439 F. 2d 35 (5th Cir. 1971)................ 25

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1 (1948)........... 25, 28

Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate School

Dist., 432 F.2d 927 (5th Cir. 1970) . . . . . 27

Smuck v. Hobson, 408 F.2d 175 (D.C. Cir. 1968),

rev1 g 44 F.R.D. 18 (D.D.C. 1968) .......... 12

Steele v. Board of Public Instruction of Leon

County, 448 F.2d 767 (5th Cir. 1971) . . . . 19

Stell v. Savannah-Chatham County Bd. of Educ.,

333 F.2d 55 (5th Cir.), cert, denied, 379

U.S. 933 (1964)............................ H

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ.,

402 U.S. 1 (1971).......................... 3, 9n, 27

Trbovich v. United Mine Workers of America, 404

U.S. 528 (1972)............................ 12

United States v. Hinds County School Bd., No.

28030 (5th Cir., March 20, 1974) .......... 19

United States v. Jefferson County Bd. of Educ.,

372 F.2d 836 (1966), aff'd en banc, 380 F.2d

385 (5th Cir.), cert, denied sub nom. Caddo

Parish School Bd. v. United States, 389 U.S.

840 (1967) ................................ 3

United States v. Quattrone, 149 F. Supp. 240

(D.D.C. 1957) .............................. 28

United States v. Texas Educ. Agency, 467 F.2d

848 (5th Cir. 1972)........................ 27

Table of Authorities (continued)

Page

IV

Table of Authorities (continued)

M i

Walpert v. Bart, 44 F.R.D. 359 (D. Md. 1968) . . . 18

Wright v. Board of Public Instruction of Alachua

County, 431 F.2d 1200 (5th Cir. 1970) . . . . 27

Wright v. Board of Public Instruction of Alachua

County, 445 F.2d 1397 (5th Cir. 1971) . . . . 19

Young v. Katz, 447 F.2d 431 (5th Cir. 1971) . . . . 22

Youngblood v. Board of Public Instruction of Bay

County, 448 F.2d 770 (5th Cir. 1971) . . . . 19

Statutes and Rules:

F.R. Civ. P. 23 ................ .. 16, 19, 22.,

F.R. Civ. P. 24 ............ 10

Local Rule 1, U.S. Dist. Ct., E.D. La. . . . . . . 15

Other Authorities:

4 Pomeroy, Equity Jurisprudence (5th Ed. 1941) . . 24

v

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

NO. 74-1672

BERYL N. JONES, et al.,

Plaintiffs,

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Plaintiff-Intervenor,

vs.

CADDO PARISH SCHOOL BOARD, et al.,

Defendant s-Appellees,

JERRY ADAMS, et al.,

Applicants for Intervention-

Appellants „

Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Western District of Louisiana

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS ADAJMSf_jet_a

Issues Presented for Review

1. Did the District Court err in denying appellants

motion to intervene in this case where appellants are all

members of the class on whose behalf this action was commenced

by the original plaintiffs, and appellants objected to the

settlement of the lawsuit upon the terms to which the original

plaintiffs had agreed because, appellants alleged, that settle

ment fails to protect the rights of the class?

2. Did the District Court err in striking from the docket

the names of plaintiffs' original counsel without their filing

motions to withdraw, endorsing a motion to substitute other

counsel for them, before notice of the motion had reached them,

and without, considering the necessity to insure adequate repre

sentation of the class on whose beha]f this suit was brought?

3. Did the District Court err in approving a purported

desegregation plan for the Caddo Parish school system by issu

ance of a consent decree in this class action, without making

findings and conclusions as to the constitutional sufficiency

of the plan? Calhoun v. Cook, 487 F.2d 680 (5th Cir. 1973) .

Statement

This appeal brings to the Fifth Circuit another unfortunate,

ugly instance in which a United States Court has become enmeshed *

in a scheme to frustrate the effectuation of the Fourteenth

Amendment.

Background of the Case

This is a classic school desegregation suit which was

brought May 4, 1965. Its progress through the years is reflected

in the major decisions of this Court which directly applied to

-2-

it, e.g., United States v. Jefferson County Bd. of Educ.,

372 F.2d 836 (1966), aff'd en banc, 380 F.2d 385 (5th Cir.),

cert, denied sub noin. Caddo Parish School Bd. v. United States,

389 U.S. 840 (1967); Hall v. St. Helena Parish School Bd., 417

F.2d 801 (5th Cir.), cert, denied, 396 U.S. 904 (1969); see

Jones v. Caddo Parish School Bd., 421 F.2d 313 (5th Cir. 19/0) .

Following this Court's Carter" remand in 1970, the District

Court approved, as modified, a school board geographic zoning

2/

plan of desegregation (R. 12). That plan did not utilize

pairing (con liguous or non—contiguous) , non-contiguous zoning,

or pupil transportation to facilitate the elimination of racially

identifiable schools in Caddo Parish. Minor modifications to the

zone lines were made on several occasions (R. 12—16).

Proceedings for Further' Desegregation

On March 6, 1972, plaintiffs filed an Amended Motion for

Further Relief (R. 22-33) seeking comprehensive desegregation

of the Caddo Parish public schools in accordance with the prin

ciples enunciated by the United States Supreme Court in Swann

v. Charlotte—Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ., 402 U.S. 1 (1971) and

companion cases. The school board responded on May 2, 1972 (R.

1/ Carter v. West Feliciana Parish School Bd., 396 U.S. 290 (1970).

2/ Citations to the reproduced Record filed with this Brief. The

record initially transmitted by the District Court Clerk has

been supplemented in accordance with this Court s Order of April

1, 1974. The entire Record as supplemented has been consecutively

paginated in the lower left-hand corner of each page.

-3-

16) but there were no further proceedings with respect to

3/school desegregation until March 5, 1973

when the school board moved to modify certain attendance zones

(R. 17) .

On March 20, 1973, plai.ntiff-intervenor United States of

America filed a "Response" to plaintiffs' year-old Amended

Motion for Further Relief (R. 34-40). The pleading noted, in

pertinent part, that:

ft]he desegregation plan approved by the

Court on February 9, 1970 projected the

continued existence of 22 all black or

predominantly black schools which were

all black schools under the dual school

system. . . . Defendants' reports to the

court reflect that these schools, and 4

other schools, are operated as all black

or predominantly black schools at the pres

ent time. The plan also projected that 19

all white or predominantly white schools

under the dual school system would continue

their racial identity under the present

plan. Defendants' reports to the court

indicate that the school system presently

operates 15 all white or predominantly

white schools.

Moreover, the present desegregation plan

does not utilize desegregation tools which

have since specifically been approved . . .

such as rezoning and pairing . . . . [R. 37]

However, the government suggested the appointment of a bi-racial

committee (whose, specific membership it proposed) to formulate

3/ A separate phase of the case involving the method of elec

tion to the school board was tried during this period. On

February 27, 1973 the matter was reassigned to District Judge

Scott upon Judge Dawkins' recusal for reasons of health.

-4-

alternative desegregation plans for the school system. The

"Response" appended a suggested Order to this effect (R. 41-

49), which was signed and issued the same date, March 20, 1973.

The Order specifically recited the Court's finding that the

school board had not carried its burden of showing that the one-

race schools were not the result of past or present discrim

inatory action (R. 44-45).

4/

The biracial committee commenced a series of meetings in

the spring of 1973, leading ultimately to its submission to

the District Court on June 1, 1973 of its proposed "desegregation

plan" (R. 82-123). On June 11, 1973, plaintiffs filed objections

to the committee's plan (R. 124-26) requesting disapproval of

its student assignment provisions. Subsequently, the United

States commented upon the committee's plan as follows (R. 130-34)

[T]he student desegregation plan also

proposes the continued operation of 34

one-race or predominantly one-race

schools. With regard to these schools,

the plan does not, as required by the

March 20, 1973 order, state the facts

relied upon to justify their continued

operation, provide options to fully

desegregate them, or state the feasibility

of implementing all or parts of deseg

regation plans for these schools on record

in this case. . . . we are unable to

respond at this time to the question

whether the plan in regard to these

schools conforms with constitutional

standards. [R. 132-33]

4/ The United States cited Calhoun v. Cook, 469 F.2d 1067

(5th Cir. 1972) in support of its implied suggestion that

the biracial committee should seek an agreed settlement of

the case (R. 38-39).

-5-

The Caddo Parish School Board notified the District Court

that it would accept the biracial committee's plan only if

it were entered as a consent decree (R. 135-38).

Also during the spring of 1973, plaintiffs retained edu

cational experts to draw a desegregation proposal for Caddo

Parish; this plan was presented to the biracial committee during

its deliberations and thereafter filed with the District Court

(R. 50-81). Three days after plaintiffs filed objections to

the committee plan, they sought to add additional adult and

minor named plaintiffs to the case, noting that many of the

original minor plaintiffs were no longer attending the Caddo

Parish schools (R. 127-29).

Substitution of Counsel and Entry of Consent Decree

It was at this juncture in the proceedings, while plain

tiffs' motion to add additional representative parties, and

their objections to the biracial committee plan, were both

pending, that a "Motion to Enroll Substitute Counsel" for the

plaintiffs was filed. This document was purportedly submitted

by one of original counsel for the plaintiffs who was then a

State official and unable to continue in his capacity as attorney

for the plaintiffs. It was signed by his law partner, who was

at that time a member of the Caddo Parish School Board. It

contained neither the signatures of other counsel for the plain

tiffs nor representations of knowledge or acquiescence in the

motion. It was unsigned by the attorney sought to be substituted

-6-

i

in place of all of these individuals, to represent the plain

tiffs and the class on whose behalf suit was brought. It was

accompanied by an affidavit signed by one of the original

plaintiffs which indicated that three of the four original

adult named plaintiffs (including one who had been dismissed

from the lawsuit in 1965) desired to discharge their attorneys

and employ new counsel. (R. 139-41).

The day after the "motion" was filed, the Order was signed

by Judge Scott striking original counsel from the case and

substituting therefor Murphy W. Bell, Esq. as attorney for the

plaintiffs and the class (R. 140).

Newly enrolled counsel then filed a motion to strike from

the record, the objections to the biracial committee plan

6/which had been filed previously (R. 154-58); this motion was

granted the same day it was submitted; and on that same day,

without any hearing or notice to the class members, the District

7/Court entered a consent decree approving the biracial committee's

plan (R. 160-61) .

5/ In the meantime, upon receiving the "motion," several of

the former attorneys for the original plaintiffs prepared

and forwarded a response to the District Court (R. 150-52) in

which they suggested that the original named plaintiffs were

no longer fairly representative or could adequately protect the

interests of the class, that the pending motion to add named

plaintiffs should be granted, that new counsel should be allowed

to represent the original named plaintiffs, that the merits of

the plans should first be considered and determination of class

representation matters postponed until after that determination

was made. While the response was in the mail, the District Court

denied the pending motion to add parties plaintiff (R. 144-45) .

6/ and 7/ continued on next page

-7-

The Attempted Intervention

On November 19, 1973, the present appellants filed their

Motion to Intervene as plaintiffs and proposed complaint (R.

170-74, 184-95). As elaborated upon in their supporting

Memorandum (R. 175-83), appellants sought to comply with this

Court's ruling in Hines v. Rapides Parish School Bd., 479 F.2d

762 (5th Cir. 1973) by specifying their claims and indicating

what consideration, if any, had been given them by the District

Court in the prior proceedings- The Motion for Leave to Inter

vene asserted:

Specifically, applicants for intervention

seek to present to the court, for resolution

on their merits, contentions which were

abandoned by the original plaintiffs after

July 13, 1973 and which have never been

explicitly ruled upon by this Court; i.e.,

that the presently operative plan of

desegregation in Caddo Parish is consti

tutionally insufficient. [R. 172]

Applicants for intervention and the class or

subclass they represent are not adequately

represented by the original plaintiffs

herein. Nor are their interests protected

by the United States of America, which was

permitted to intervene as a plaintiff

herein but which acceded to the approval and

implementation of the current plan of operation

despite its earlier expressed position that

[continued] •

<3/ Counsel for the present appellants first saw this motion

when the record on this appeal was withdrawn for purposes

of reproduction.

7/ The United States did not consent but endorsed entry of the

Order in the following statement (R. 160):

-8- [continued next page]

such approval, without a showing to justify

the continued existence of one-race schools,

was improper. [R. 173]

Present appellants also addressed, in their Motion and the

supporting Memorandum, the question of timeliness:

Intervention will not delay nor unduly

prejudice the rights of the original parties.

The presently operative plan of desegregation

was approved by this Court on July 20, 1973,

on the basis that none of the parties had

filed objection thereto [the Court having

permitted new counsel for original plaintiffs

to withdraw previously filed objections]

and without a determination that the plan

meets constitutional standards. Intervening

decision of the United States Court of Appeals

for the Fifth Circuit in Calhoun v. Cook, No.

73-2020 (August 21, 1973) will require an

evidentiary hearing and determination on the

merits by this Court in any event. . . .

[R. 173]

On February 4, 1974, the District Court denied leave to

intervene (R. 204—05), finding (a) that the original plaintiffs

adequately represented the class, and (b) that the application

was untimely. (R. 205). As a result, the public schools of

Shreveport remain largely segregated under the District Court's

Order, and unless appellants are permitted to intervene and

challenge that plan, the schools will remain segregated unto

eternity.

[continued]

The present posture of this lawsuit considered,

the United States of America, intervenor here

in, interjects no objection to ordering imple

mentation of this plan, as is more fully set

out in its response filed herein.

That response, of course, had noted the inadequacy of the plan

under Swann.

-9-

ARGUMENT

I

The District Court Erred

In Denying Intervention

Present appellants contend here, as they did before the

District Court, that their intervention is supported by law and

justice, and that their moving papers adequately complied not

only with the technical requirements of F.R. Civ. P. 24(a) and

(b) [governing both mandatory and permissive intervention], but

also with the special considerations governing intervention in

school desegregation actions outlined by this Court in Hines v.

Rapides Parish School Bd., 479 F.2d 762 (5th Cir. 1973) . A

detailed treatment of the Federal Rules issues can be found in

our Memorandum submitted to the District Court (R. 175-83), and

we respectfully refer the Court to that portion of the record.

We shall not duplicate that discussion here but rather seek to

elucidate the most compelling reasons why intervention should

have been allowed.

A. The interests sought to be represented by the appellants

were not adequately protected by the original plaintiffs

in the proceedings before the District Court____________

A classic ground for intervention is to permit the repre

sentation and protection of interests which would be affected by

the outcome of a lawsuit but would otherwise go unheard. Such

a notion forms the basis of F.R. Civ. P. 24(a)(2), setting forth

-10-

the requirements for intervention as of right. There can be no

question but that appellants will be affected by the progress of

this litigation, for minor appellants are public schoolchildren

of Caddo Parish whose school assignments, and chances for re

ceiving their constitutional entitlement of an integrated education,

are entirely dependent upon the orders of the District Court.

Indeed, the lower court's holding is not grounded upon any

lack of an affected interest in appellants, but rather upon

the court's belief that appellants' interests were adequately

represented by the existing parties. That belief is nothing

less than incredible upon this record, which fairly shrieks of

the inadequate representation afforded appellants and the class

they sought to represent.

This case is unlike most of those in which intervention law

in school desegregation suits has been fashioned. Commonly,

these have involved attempts by white parents to intervene in

1order to add their voice to that of the school authorities in

resisting desegregation. E .g., Hatton v. County Dd. of Educ.

of Maury County, 422 F.2d 457 (6th Cir. 1970) ; Stell v. Savannah-

Chatham County Bd. of Educ., 333 F.2d 55 (5th Cir.), cert, denied,

379 U.S. 933 (1964). In such cases, traditionally intervention

as of right has been disallowed since it was evident that no

party could resist integration harder nor more effectively than

the school boards themselves were already doing. See Hatton,

supra, 422 F.2d at 461. And although appellants' right to

ri

-11-

intervene stands on a different footing, the more recent

holdings that white parents in the circumstances outlined above

should be entitled to intervene cannot but support appellants'

position here. See, e.g., Smuck v. Hobson, 408 F.2d 175 (D.C.

Cir. 1968) , rev1g 44 F.R.D. 18 (D.D.C. 1968) ; Dowell v. School

Bd■ of Oklahoma City, 430 F.2d 865 (10th Cir. 1970).

In the instant case, however, the situation is the converse

of that in the cases involving intervention by white parents.

The record clearly establishes that appellants met their "minimal

burden" of demonstrating that representation of their interests

by the original plaintiffs "may be inadequate." Trbovich v.

United Mine Workers of America, 404 U.S. 528, 538 n.10 (1972) .

Here, appellants noted in their moving papers that they joined

in objections to the biracial committee plan originally filed by

the plaintiffs (R. 174). Their interest was the approval of a

constitutional plan of desegregation for Caddo Parish, which

they asserted was not provided by the biracial committee's sub

mission. They posited no hypothetical lack of representation,

for their request to intervene was filed after the original

plaintiffs withdrew the objections and consented to the entry of

a decree which leaves 34 Caddo Parish schools with one-race

8/student bodies.

8/ We treat the issue of timeliness below, but we pause here

to emphasize that the request to intervene was not untimely

simply because it was post-judgment. See Cascade Natural Gas

Corp. v. El Paso Natural Gas Co., 386 U.S. 129 (1967); Atlantis

Development Corp. v. United States, 379 F.2d 818 (5th Cir. 1967).

-12-

r

The point can be stated almost syllogistically. Appellants

claim that the biracial committee plan is unconstitutional. At

the time the District Court approved the plan, no party to the

lawsuit had expressed this position on the record, previous

objections having been withdrawn. The District Court made no

finding as to the constitutionality of the plan when it approved

it (R. 160-61). Thus, appellants' interests were not only not

adequately represented before the District Court at the time of

judgment: their concerns were not even voiced!

Despite these facts, the District Court's order denying

intervention offers no explanation for its bald conclusion that

"[c]onsidering the record, the Court finds that the original

plaintiffs adequately represent the class" (R, 205). Under rhe

circumstances, therefore, the order must be reversed.

B. Appellants complied with the requirements of Hines v.

Rapides Parish School Bd., supra.____________________

This Circuit has required particular clarity of inter

vention papers in school desegregation cases, to the ends of

judicial economy and prompt adjudication. Hines v. Rapides

Parish School Bd., supra; Lee v. Macon County Bd. of Educ., 482

F.2d 1253 (5th Cir. 1973). See Calhoun v. Cook, supra, 487 F.2d

at 683. Appellants were aware of these decisions at the time

of their attempted intervention, and complied with them.

Hines describes the determinations which must be made by

district courts passing upon applications to intervene in school

-13-

I

desegregation cases, and which pleadings should facilitate, as

follows (479 F.2d, at 765):

The district court could then determine

whether these matters had been previously

raised and resolved and/or whether the

issues sought to be presented by the new

group were currently known to the court

and parties in the initial suit. If the

court determined that the issues these new

plaintiffs sought to present had been

previously determined or if it found that

the parties in the original action were

aware of these issues and completely com

petent to represent the interests of the

new group, it could deny intervention.

[emphasis supplied]

The pleadings of the appellants state the issues with clarity.

The issues not resolved in the litigation were the

constitutionality of the biracial committee's plan and the

adequacy of continuing class representation by the original

plaintiffs. The application to intervene did not rest upon

allegations of collusion in the entry of the consent decree,

as did such requests, in part, in Calhoun v. Cook, supra, see

487 F.2d, at 683. Under the circumstances of this case, there

fore, the pleadings need not be reframed, ibid., and this Court

should return the case to the District Court with directions

to permit intervention.

C. Intervention would have corrected the error committed by

the District Court in the substitution of counsel.______

Intervention by appellants was additionally desirable be

cause it would have dissipated the effects of the District

Court's failure to protect the interests of the class on whose

-14-

behalf this suit was brought, both at the time the District

Court permitted substitution of counsel, and at the time it

allowed withdrawal of objections to the biracial committee plan

previously filed and simultaneously entered a consent decree

approving the plan.

This record bears eloquent witness to the unfortunate

failure of the District Court, to shoulder its responsibility

under the Constitution and laws of the United States. Indeed,

it is euphemistic to term the 1970 proceedings in this case as

"highly irregular." The actions of the District Court provide

anything but a lesson in due process.

Plaintiffs' Amended Motion for Further Relief, for example,

elicited no judicial response whatsoever for more than a year.

The same day the United States filed its Response thereto, how

ever, suggesting the novel procedure of placing responsibility

for the development of a new plan not upon the school authorities

but upon a "citizens committee," the Court issued an Order to

this effect. Subsequently, without awaiting or seeking responses

from all of plaintiffs' counsel in this class action, the Court

within one day granted a highly unusual motion to strike all

of plaintiffs' counsel from the case and substitute in their

stead a newcomer to the litigation, nonresident within the judicial

district. Compare, e.g., Local Rule 1(H)(1), U.S. Dist. Ct., E.D.

La •

-15-

Since there was pending before the District Court at that

time, a motion to add additional representative parties plain

tiff which specifically noted that many of the minor original

plaintiffs no longer attended Caddo Parish public schools the

District Court should have been alerted to the problems of

class representation which needed to be resolved. The District

Court only compounded the error when, after receiving a Response

from some of plaintiffs’ original counsel which expressed doubt

that original plaintiffs adequately represented the class (R.

150), it did not reconsider its Order substituting counsel; and

when it subsequently permitted withdrawal of the objections to

the biracial committee plan and compromised this class action

without either notice or hearing. F.R. Civ. P. 23; Calhoun v.

Cook, supra.

These defects could have been vitiated by the granting of

intervention to appellants, for the District Court could then

have entertained the necessary proceedings and held the necessary

hearings to determine the constitutionality of the committee

plan. The denial of intervention thus serves to carry other

District Court errors forward in this cause and makes reversal

even more critical.

D. The intervention was timely.

The District Court denied intervention on two grounds: that

appellants' interests were adequately represented throughout

the proceedings (see above) and that, "[a]t any rate, the Motion

-16-

to Intervene comes too late" (R. 205). This second basis for

decision is no more satisfactory than the first.

If the District Court meant that the intervention would

have been timely only if filed before entry of its consent judg

ment, it was requiring virtually a physical impossibility as

well as a legal irrelevancy. Appellants include many of the

individuals sought to be added as plaintiffs prior to the

substitution of counsel on July 13, 1973. Their present coun

sel were not served with the motion to substitute counsel until

four days prior to the entry of the consent judgment; they did

not become aware that the District Ccurt had granted it (without

allowing them an opportunity to respond) until after- the consent

decree was issued on July 20, 1973. The District Court's order

denying the motion to add additional plaintiffs was denied just

two days prior thereto, on July 18, but again counsel for appel

lants did not receive notice of this action until after the

consent judgment was entered.

Of course, there is no legal support for the notion that

post-judgment interventions are per se untimely. Indeed, this

case bears a striking resemblance to the leading decision in

the area, Cascade Natural Gas Corp. v. El Paso Natural Gas Co.,

supra. There, as here, the district court was confronted with

the problems of "dismantling an illegal structure." Also, as

here, the applicants asserted an interest in how the dismantling

-17-

should be accomplished, pointing out the potential injury

that would be done if the court proceeded in implementing the

divestiture plan as proposed by the United States. Significantly,

after a costly and time-consuming appeal prosecuted by the

applicants, they were permitted intervention by the Supreme Court

after entry of a consent decree.

The District Court's conclusion is no more well-founded

in general terms. Courts have been especially reluctant to

dispose of applications for intervention on grounds of untime

liness. E_. cj_., Cameron v. President. & Fellows, 157 F.2d 993

(1st Cir. 1946) ; Walpert v. Bart, 44 F.R.D. 359, 361 (D. Md.

1968). The most important interests served by time requirements

for intervention are already satisfied here: finality and

avoidance of prejudice to opposing parties.

As to considerations of finality, it is true that the

application to intervene came after the plan of the biracial

committee had been implemented in Shreveport for the 1973-74

school year. However, unlike other types of litigation, decrees

in school desegregation cases are subject to repeated modification

and reopening to insure compliance with current legal standards.

See Ellis v. Board of Public Instruction of Orange County, 465

F.2d 878, 879-80 (5th Cir. 1972), cert, denied, 410 U.S. 966

(1973). It cannot fairly be maintained that intervention by

-18-

1

appellants was sought after this case had "come to rest," since

in this Circuit school desegregation suits must be maintained

on the docket for at least three years following entry of supposedly

"terminal" decrees, Youngblood v. Board of Public Instruction

of Bay County, 448 F.2d 770 (5th Cir. 1971) ; Steele v. Board of

Public_Instruction of Leon County, 448 F.2d 767 (5th Cir. 1971);

V.'right v. Board of Public Instruction of Alachua County, 445 F.2d

1397 (5th Cir. 1971), and even thereafter may be reopened upon

motion. See, e.g., United States v. Hinds County School Bd.

[Lauderdale County School Dist.], No. 28030 (5th Cir., March 20,

1974) .

Nor would intervention, if granted when sought or if ordered

now, prejudice the rights of the other parties. Clearly the

Caddo Parish school authorities have no right to continue

operating an unconstitutional school system. Nor have the

original plaintiffs any right to defeat the constitutional rights

of the class of minor schoolchildren in the Parish by acquiescing

in such a plan. Appellants have not sought midyear disruption

of the biracial committee plan so the parties did not have to

face possible prejudice of that nature, if prejudice to rights

it is. Compare Alexander v. Holmes County Bd. of Educ., 396 U.S.

19 (1969); Carter v. West Feliciana Parish School Bd., 396 U.S.

226 (1969), 396 U.S. 290 (1970).

Furthermore, this case is clearly controlled by Rule 23,

F.R. Civ. P. as authoritatively interpreted in Calhoun v. Cook,

-19-

l

supra, to invalidate approval of desegregation plans by entry

of consent decrees. Thus, if the minimal legal requirements

are to be carried out in this case, there must be further

hearings and findings about the constitutionality of the biracial

committee plan by the District Court. Those hearings had not

been scheduled or held at the time appellants sought to intervene,

nor have they been scheduled or held since that time. For

this reason, none of the other parties to this lawsuit would have

or will suffer the slightest prejudice from the intervention as

plaintiffs of the appellants at this time.

II.

This Case Should Be Remanded To Another

District Judge With Instructions To

Disapprove The Biracial Committee Plan

In the circumstances of this case, we believe the Court

must go farther than merely reversing the District Court's

denial of intervention. We respectfully suggest the Court's

heavy responsibility to insure enforcement of the Fourteenth

Amendment requires that it vacate the Order approving the bi

racial committe's plan and remand the matter for further pro

ceedings before another district judge, with instructions that

the committee plan is facially insufficient on this record to

meet the constitutional mandate.

-20-

A. A reversal of the intervention ruling alone, or with a

remand to the District Court to reconsider its approval

of the biracial committee plain will lead only to delay

and is unnecessary since the holding and principles of

Calhoun v. Cook, 487 F.2d 680 (5th Cir. 1973), are so

clearly controlling._______________________ ___________

A ruling by this Court that appellants should have been

permitted to intervene but which did not also vacate the

District Court's consent judgment approving the biracial

committee plan for Caddo Parish would insure yet another delay

in the effectuation of the Fourteenth Amendment in the parish's

school system. We submit that, inasmuch as appellants sought

to intervene to challenge the plan and even brought this Court's

disapproval of consent decrees in school desegregation cases to

the attention of the District Court, and since Calhoun v. Cook,

supra, is so clearly applicable to the facts of this suit, that

this Court should vacate the lower court's approval of the plan

and obviate unnecessary delay which would result from remanding

to the District Court for consideration in light of Calhoun and

with the participation of appellants as intervenors.

As this Court said in Calhoun:

At least some of the attorneys representing

the original plaintiffs assert no such

compromise was made. The attempted inter

venors sought to demonstrate that still other

parties whom they assert are class members

would object. In these circumstances the

advisability of approval and the viability

of the plan submitted could not properly be

adjudicated on the basis oil Rule 23(e) [, F.R.

Civ. P.] . (487 F. 2d, at 682)

Calhoun is but the logical extension of the settled principle

that the judgment of a court approving a settlement of a class

21-

action under Rule 23(e) must be founded on facts. Cohen v.

Young, 127 F.2d 721 (6th Cir. 1942); Sertic v. Cuyahoga Lake,

etc., Carpenters Dist. Council, 459 F.2d 579 (6th Cir. 1972);

cf. Ashback v. Kirtley, 289 F.2d 159 (8th Cir. 1961) . Here, of

course, there was no factual presentation by opponents of the

plan nor did the District Court make factual findings about the

proposals before it, nor draw conclusions as to the legal and

9/constitutional sufficiency of the plan embodied in the decree.

The acquiescence of counsel for the United States, the

defendants, and the named representative plaintiffs did not

relieve the District Court of its obligation to hear evidence

and make findings. Cohen v. Young, sip ra. Accord, Young v.

Katz, 447 F.2d 431 (5th Cir. 1971).

When presented with the consent decree and the acquiescence

of the existing parties, it was the District Court's obligation

— even apart from the peculiar circumstances of withdrawal of

previous objections, etc. — to examine the proposal as the

"guardian" of the rights of the absent class members affected

by the judgment. Norman v. McKee, 431 F.2d 769, 774 (9th Cir.

1970). For a number of reasons, this role is particularly crit-

9/ The District Court refers to the proceedings of the biracial

committee as if to suggest that the presentation of appellants'

objections and proposed plan to that body was a sufficient sub

stitute for judicial consideration (R. 204-05). But the judicial

power, and judicial responsibility, is non—delegable. Cf.

Calhoun v. Cook, supra, 487 F.2d, at 683.

-22-

ical in school desegregation cases.

The first reason stems from the very nature of class

actions to enforce Fourteenth Amendment rights under Brown v.

Board of Educ., 347 U.S. 483 (1954). This Court's illuminating

decision in Flax v. Potts, 313 F.2d 284 (5th Cir. 1963), shows

that by the vary nature of the controversy, litigation attacking

a school system's practice of racial discrimination cannot be

limited in its operative effect to individual plaintiffs. Decrees

in cases challenging entrenched dual systems of segregation

touch upon and determine whether or not discriminatory practices

will continue or be eliminated for each pupil i.n the system.

In some types of class action litigation non-participating

members of the class may exercise an option not to be bound by

the litigation and "opt out" of a case. No such choice is avail—

â-)le to students attending a public school system operated as

a dual system. Either the system is transformed into a unitary

system where all vestiges of discrimination are eliminated or

it continues as an unconstitutional system for all the pupils.

Another reason the court must function as a guardian for

absent parties in considering compromise of a school case is

the fact that the case involves the precious constitutional

rights of persons who are children unable to protect their own

rights. The right of a student not to be segregated on racial

^f^c^^ds in schools so maintained is indeed so fundamental and

-23-

pervasive that it is embraced in the concept of due process

of law." Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1, 19 (1958). Minors,

unable to protect their own rights in court, must be the subject

of the special solicitude and protection of courts of equity.

The tradition of equity is that infants are "wards of the court."

4 Pomeroy, Equity Jurisprudence 871 (5th Ed. 1941).

Still another reason proposed settlements of school

segregation litigation must be scrutinized with great care is

that resistance to implementation of the Brown decision has been

so widespread that the courts must constantly guard against

schemes to avoid and evade the law of school desegregation. The

Court is familiar with the history of interposition resolutions,

massive resistance laws, school closing, pupil placement laws,

tuition grants, and other overt and covert plans to evade and

avoid compliance with Brown. Currently there is widespread

political activity against "busing" to promote school desegre

gation. Some black people, as well as white people, have

advocated continuing segregation — particularly those who,

as have some of the actors in the instant case, have attained

positions within the political apparatus still dominated by whites.

In this situation the courts' task of enforcing the Constitution

requires a difficult vigilance to ensure that court-approved

compromises of school cases do not accomplish indirectly that

which the interposition resolutions failed to achieve by direct

defiance of Brown.

-24-

Yet such is clearly the result of the proceedings below,

in which the District Court, which had every reason to doubt

the validity of the consent judgment, ignored its responsibilities

to the absent class members. This action by the lower court

amounts to plain error which is subject to correction on this

appeal. As this Court said in 1971, affirming a district court's

order refusing to permit plaintiffs to dismiss a class action

voting rights suit,

. . . having instituted a public lawsuit to

secure rectification for a constitutional

wrong of wide dimension, [plaintiffs] cannot

privately determine its destiny.

Sheffield v. Itawamba County Bd. of Supervisors, 43 9 F.2d 3 5,

36 (5th Cir. 1971). The discretionary powers of the District

Court in determining whether to approve a proposed settlement

are necessarily limited by the Court's duty to avoid approval

of a decree which affirmatively authorizes continued discrimin

ation (Flax v. Potts, supra; Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1

(1948)) .

In sum, the District Court's action in approving the

biracial committee's plan because it had the "consent" of the

parties, cannot be reconciled with the Court's obligations under

the Fourteenth Amendment and the Judicial Code. ’That order must

be vacated and the cause remanded with instructions to permit

intervention, to hold hearings and to make findings in support

of the ultimate decree of the court.

25-

i-

B. This Court should also instruct the District Court on remand

that the biracial committee plan is unconstitutionally

insufficient on this record because it fails to desegregate

the Caddo Parish public schools.____________________________

We further submit that this Court's decision should also

eliminate the necessity for the District Court to delay the

implementation of a comprehensive desegregation plan for Caddo

Parish by holding hearings or taking additional time to deter

mine whether the biracial committee plan could be constitutional.

The fatal deficiencies of the settlement proposal to eliminate

racial segregation of pupils attending the schools of the Caddo

Parish system are evident and apparent on the face of the plan.

Some objections to the plan would require factual inquiry; however,

looking at the face of the plan and at the documents in this

record, it is clear that the plan's major defects preclude any

approval under this Court's governing precedents.

The plan reveals it will leave 34 one-race schools in

Caddo Parish; it does not employ any assignment technique

except contiguous geographic zoning (often misnamed the "neigh

borhood school" method of assignment). It was characterized

by the Response of the United States, a signatory to the consent

decree, as constitutionally inadequate for its f&ilure to explain

why alternate desegregation proposals for these schools, contained

in the plaintiffs' plan (filed prior to removal of plaintiffs'

counsel) of even the 1969 IIEW plan, were not feasible. No further

explanation was ever offered or accepted.

-26-

Anyone familiar with the course of the development of

school desegregation law in this Circuit would recognize that

more than four years ago — a year before the Swann decision —

this Court required school districts at a minimum to pair

contiguous segregated schools. Caddo Parish has not yet met

the standards applied in such cases as Allen v. Board of

Public Instruction of Broward County, 432 F.2d 362, 367 (5th

Cir. 1970); Pate v. Dade County School Bd., 434 F.2d 1141 (5th

Cir. 1970); Bradley v. Board of Public Instruction of Pinellas

County, 431 F.2d 1377 (5th Cir. 1970); Wright v. Board of

puklic _Jjnstruction of Alachua County, 431 F.2d 1200 (5th Cir.

19,70) ; Henry v. Clarksdale Municipal Separate School Dist., 433.

F.2d 387 (5th Cir. 1.970); Singleton v. Jackson Municipal

Sepa rate S choo1 D i s t., 432 F.2d 927 (5th Cir. 1970). Now, under

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklcnburq Bd. of Educ., 402 U.S. 1 (1971)

and Davis v. Board of School Comm'rs of Mobile, 402 U.S. 33

(1971), the law requires the use of such remedial techniques as

busing, non—contiguous zones, grouping of schools and the like

if necessary to desegregate. See Cisneros v. Corpus Cnristi

Independent School Dist., 467 F.2d 142 (5th Cir. 19/2) ; United.

States v. Texas Educ. Agency, 467 F.2d 848 (5th Cir. 1972).

The Caddo Parish settlement plan approved by the District Court

does not even remotely approach compliance with this standard.

The plan is unconstitutional on its face as a matter of law.

-27-

Each of the black children attending the schools of Caddo

Parish has a "personal and present" constitutional right to

equal protection of the laws. Each of these children has a

right to require that the defendants operate the public schools

in accordance with the Constitution. No one has a right to

demand otherwise. "The Constitution confers upon no individual

the right to demand action by the State which results in the

denial of equal protection of the laws to other individuals."

Shelley v. Kraemer, supra, 334 U.S., at 22. The District Court

had no power to decree otherwise, by "consent" of anyone. Flak

v. Potts, supra. Recently, this Court opined that in this case,

"[e]ight years of litigation between the original parties has

final],y come to an end" (R. 164) . Unfortunately that statement

is wrong. There is but one way to brxng the case to a lawful

end and that is to desegregate the Caddo Parish public schools

as required by the Constitution.

C. This case should be remanded with instructions that it

be transferred to another district judge._____________

It has often been remarked that courts should avoid the

appearance of impropriety as well as impropriety itself. Cf.,

e.g., United States v. Quattrone, 149 F. Supp. 240 (D.D.C. 1957) .

It is in accord with this spirit that appellants reluctantly

and respectfully advise this Court that here, the appearance

of impropriety is great; and we respectfully suggest that it

-28-

would be appropriate for further proceedings on remand in this

matter to be conducted before another district judge, upon

the direction of this Court in the exercise of its supervisory-

jurisdiction and responsibility.

We do not believe that the strange history of these proceed

ings, nor the apparent disregard by the District Court of its

obligations toward the class, need be repeated. We submit,

however, that the events are subject to interpretation which

does not reflect well upon the Courts of the United States. We

allege no impropriety nor do we possess extralegal evidence of

any; yet we cannot brand such an interpretation of the events

as irrational. But the question can best be removed from these

proceedings, we submit, by transferring them to another district

judge or by this Court retaining jurisdiction to approve a

constitutional plan of operation for the Caddo Parish schools.

CONCLUSION

WI-IEREFOP.E, for the foregoing reasons, appellants respec-

fully pray that the Order of the District Court denying intervention

be reversed, that the Order of the District Court approving the

desegregation plan of the biracial committee be vacated, that

either jurisdiction of the cause be retained by this Court or

the cause be remanded to another district judge with instructions

to consider the plaintiffs' plan and any new plan to be submitted

by either the United States or the school board, to make findings

-29

thereon, and to approve and supervise the implementation of a

plan which removes all vestiges of the dual system from Caddo

Parish, as required by the Fourteenth Amendment, the decisions

of the United States Supreme Court and of this Court.

Appellants further respectfully pray that this Court grant

them reasonable attorneys' fees in connection with this appeal

Northcross v. Board of Educ. of Memphis, 412 U.S. 427 (1973),

as well as their costs.

Respectfully submitted.

HILRY HUCKABY, III

501 Petroleum Tower

Shreveport, Louisiana 71101

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

NORMAN J. CHACHKIN

MARGRETT FORD

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Appellants

ADAMS, et al.

-30-

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

i.

I hereby certify that on this 15th day of April, 1974,

I served two copies of the Brief for Appellants Adams, et al.

upon counsel for the appellees herein, by depositing same in

the United States mail, first class postage prepaid, addressed

to each as follows:

Murphy W. Bell, Esq.

617 North Boulevard

Baton Rouge, Louisiana

John R. Pleasant, Esq.

1004 Mid South Towers

P. O. Drawer 1092

Shreveport, Louisiana 71163

Hon. Donald E. Walter, Esq.

United States Attorney

Federal Building

Shreveport, Louisiana 71101

Brian Landsberg, Esq.

Civil Rights Division

Department of Justice

Washington, D.C. 20530

-31-