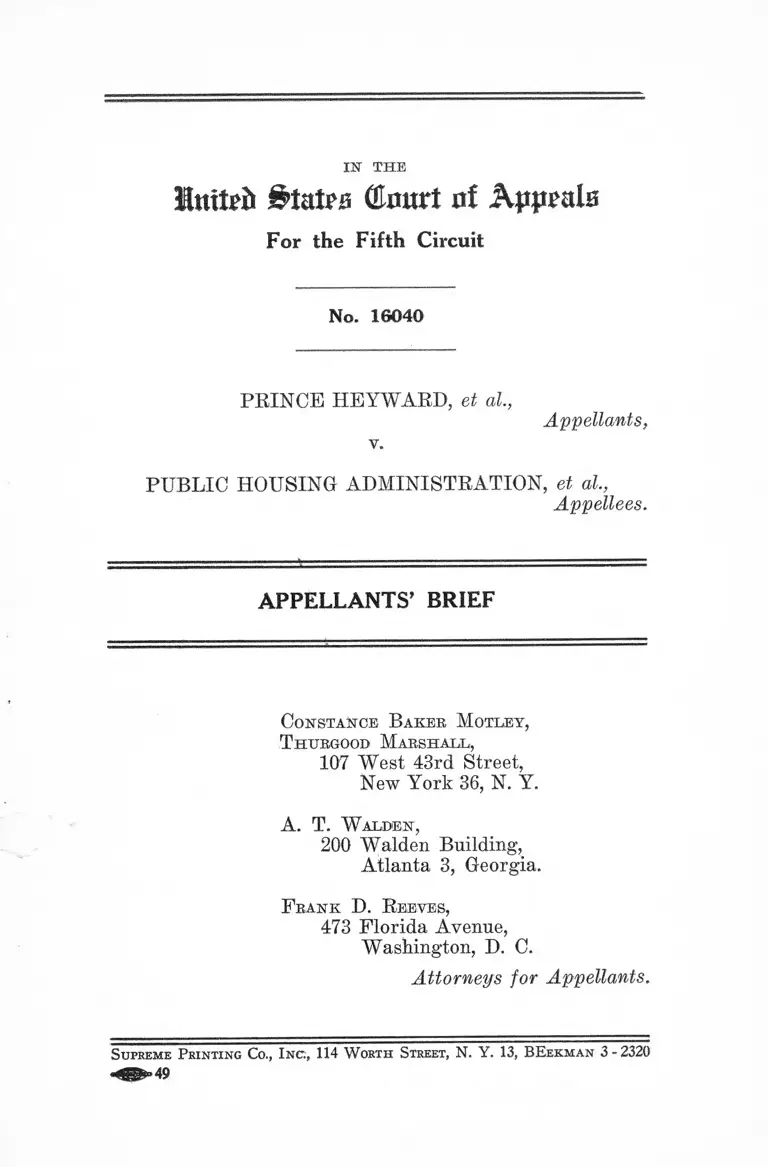

Heyward v. Public Housing Administration Appellants' Brief

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1956

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Heyward v. Public Housing Administration Appellants' Brief, 1956. 5848e41d-b89a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/6d3522a7-e697-4c5c-8dab-dfc39bad2f55/heyward-v-public-housing-administration-appellants-brief. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

IN T H E

Itttteii States dmtrt rtf Appeals

For the Fifth Circuit

No. 16040

PEINCE HEYWARD, et al,

v.

Appellants,

PUBLIC HOUSING ADMINISTRATION, et al,

Appellees.

APPELLANTS’ BRIEF

Constance B aker Motley,

T htjrgood Marshall,

107 West 43rd Street,

New York 36, N. Y.

A. T. W alden,

200 Walden Building,

Atlanta 3, Georgia.

P rank D. R eeves,

473 Florida Avenue,

Washington, D. C.

Attorneys for Appellants.

Supreme P rinting Co., I nc., 114 W orth Street, N. Y. 13, BEekman 3 - 2320

« “49

I N D E X

Statement of the Case ............................................. 1

Specification of E r ro r s ............................................. 5

Argument ................................................................... 6

I. Jurisdiction.................................................... 6

II. V enue............................................................. 10

III. Justiciable Case or Controversy ................ 15

A. Nature and Extent of PH A Participation

In The Limitation of Certain Projects to

White Occupancy.................................... 15

B. By Placing Requirement of Title 42,

United States Code, §§ 1410(g) and

1415(8) (c) in its Contract with SHA,

PHA Has Not Discharged Its Obligation 22

C. Plaintiffs Have Sufficient Legal Interest

in Expenditures of Funds By PHA To

Give Them Standing To Challenge Vali

dity of Such Expenditures .................... 24

1. Nature and Extent of PHA’s Financial

Assistance................................................. 24

2. Nature of Plaintiffs’ Interest in PHA

Expenditures ............................................ 26

IV. The Separate But Equal Doctrine ............. 28

Tabe of Cases

Armstrong v. Townsend (S. D. Ind. ), 8 F. Supp. 953 7

Bitterman v. Louisville & N. R. Co., 207 U. S. 205 .. 7, 8

Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U. S. 497 ............................... 6

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60 ........................... 28, 29

PAGE

11

Chesapeake & Del. Canal. Co. v. Glring (C. A. 4th),

159 F. 662, cert, den., 212 U. S. 571 .................... 7

City of Birmingham v. Monk (C. A. 5th), 185 F. 2d

859, cert, den., 341 U. S. 940 .................................. 29

City of Memphis v. Ingram (C. A. 8th), 195 F. 2d

338 ............................................. ............................ 9

Crabh v. Weldon Bros. (S. D. Iowa), 65 F. Snpp. 369

rev. on other grds., 164 F. 2d 797 ........................ 23

Detroit Housing Commission v. Lewis (C. A. 6th),

226 F. 2d 180 ........................................................ 28

Doremus v. Board of Education, 342 U. S. 429 . . . . 27

Downs v. Wall (C. A. 5th), 176 Fed. 657 ................ 11

Ebensherger v. Sinclair Refining Co. (C. A. 5th), 165

F. 2d 803, cert, den., 335 U. S. 816........................ 7,8

Federal Housing Administration v. Burr, 309 U. S.

242 .......................................................................... 10

Federal Trade Commission v. Winsted Hosiery Co.,

258 U. S. 483 ...................................................... 26

Giles v. Harris, 189 U. S. 475 .................................. 6

Glenwood Light & Power Co. v. Mutual Light, Heat

and Power Co., 239 H. S. 121............................... 7

Hague v. C. I. O., 307 U. S. 496 ............................... 6

Heard v. Ouachita Parish School Board (W. D. La.),

94 F. Supp. 897 .................................................... 11

Heyward v. PHA (C. A. D. C.), 214 F. 2d 222 . . . . 4,16

Housing Authority of San Francisco v. Banks, 120

Cal. App. 2d 1, 260 P. 2d 668, cert, den., 347 H. S.

974 .......................................................................... 28

Hurd v. Hodge, 334 U. S. 2 4 .................................... 6

International Shoe Co. v. Washington, 326 U. S. 310 11,14

Joint Anti-Fascist Refugee Comm. v. McGrath, 341

U. S. 123

PAGE

26

I l l

Jones v. City of Hamtramek (S. D. Mich.), 121 F.

Supp. 123 ............................................................... 28

Jones v. Fox Film Corp. (C. A. 5th), 68 F. 2d 116 .. 11

Kelley v. Lehigh Nav. Coal Co. (C. A. 3d), 151 F. 2d

743, cert, den., 327 U. S. 779 ............................... 7

Keifer v. Reconstruction Finance Corp., 306 U. S.

381 .......................................................................... 10

.Lansden v. Hart (C. A. 4th), 180 F. 2d 679 ............. 7

Lisle Mills, Inc. v. Arkay Infants Wear (E. D. N. Y.),

84 F. Supp. 697 ..................................................... 11

Lone Star Package Car Co. v. Baltimore & Ohio R.

Co. (C. A. 5th), 212 F. 2d 147....................... 11

Massachusetts v. Mellon, 262 U. S. 447 .................... 27

Mississippi & Missouri R. R. v. Ward, 67 U. S.

(2 Black) 485 .......................................................... 7

Nixon v. Condon, 286 U. S. 7 3 .............................. 6

Nixon v. Herndon, 273 U. S. 536 ................................. 6

Nueces Valley Townsite Co. v. McAdoo (W. D. Tex.),

257 Fed. 143 ............................................................ 9

Perkins v. Benquet Consol. Min. Co., 323 U. S. 437 .. 11

Pollack v. Public Utilities Commission (C. A. I). C.),

191 F. 2d 450 ............................................................ 20

Public Utilities Commission v. Pollack, 343 U. S.

451............................................................... 18,19,20

Roberts v. Curtis, 93 F. Supp. 604 ........................... 6

Scott v. Donald, 165 U. S. 107.................................... 7

Seawell v. McWhithey, 2 N. J. Super. 255, 63 Atl. 2d

542, rev. on other grds., 2 N. J. 563, 67 Atl. 2d 309 29

Seven Oaks Inc. v. Federal Housing Administration

(C. A. 4th), 171 F. 2d 947 ...................................... 10

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1.................................. 29

PAGE

XV

Sigora v. Slusser (D. C. Conn.), 124 F. Supp. 327 .. 10

Smith v. Adams, 130 U. S. 167.................................. 7

Smith v. Allwright, 321 U. S. 649 ............................... 6

Smith v. Merrill (C. A. 5th), 81 F. 2d 609 .................. 11

Swafford v. Templeton, 185 XL S. 487 ....................... 6

Taylor v. Leoxxard, 30 N. J. Super. 116, 103 Atl. 2d,

633 .......................................................................... 29

Travelers Health Assoc, v. Com. of Va., 339 IT. S.

643 .......................................................................... H

Vann v. Toledo Metropolitan Housing Authority

(N. D. Ohio), 113 F. Supp. 210 ........................... 28

Wiley v. Sinkler, 179 U. S. 5 7 .................................. 6

Young v. Kellex Corp. (E. D. Tenn.), 82 F. Supp.

953 .......................................................................... 23

Statutes

Title 5, United States Code, 113y-113y-16................... 10

Title 28, United States Code, § 1331......................... 1, 6

Title 28, United States Code, § 1343(3) .................... 1

Title 28, United States Code, § 1391(c).................... 10

Title 28, United States Code, § 1392 ......................... 11

Title 42, United States Code, § 1401, et seq................. 3

Title 42, United States Code, § 1403a........................ 10

Title 42, United States Code, § 1404a........................ 10,19

Title 42, United States Code, § 1405a........................ 10

Title 42, United States Code, §1409, § 1410(a),

§ 1410(c) ................................................................. 24

Title 42, United States Code, § 1410(g) .............1, 6,19, 22

Title 42, United States Code, § 1411(a), 1413........... 25

Title 42, United States Code, § 1415(7) (a) ............... 24

Title 42, United States Code, § 1415(7) ( b ) .............. 18

Title 42, United States Code, § 1415(8) (c) . . . .1, 6,19, 22, 23

PAGE

V

Title 42, United States Code, § 1421a....................... 26

Title 42, United States Code, § 1982 ......................... 1, 6, 28

Title 42, United States Code, § 1983 ......................... 1

Housing Authorities Law of Georgia, 99 Ga. Code

Annotated, 1101 et seq............................................ 3

Other Authorities

Annotation 30 A. L. R. 2d, 602, 621 (1953) ............ 7

Annotation 30 A. L. R. 2d, 602, 619 (1953) ............. 7

Form PHA-1954, Rev. July 1950 ....... ...................... 15

HHFA-PHA Low Rent Housing Manual, Feb. 21,

1951, § 102.1 ........................................... ................ 15

Journal of Housing Yol. 13, No. 4, April 1956, p. 134 8

Restatement of Torts, § 876 ...................................... 27

Sen. Rep. No. 84, 81st Cong. 1st Sess., 2 U. S. Code

Congressional Service 1569 (1949) ........................ 22

Sen. Rep. No. 84, 81st Cong. 1st Sess., 2 U. S. Code

Congressional Service 1566, 1570 (1949) ............. 23

PAGE

Terms and Conditions Constituting Part II of Annual

Contributions Contract Between Local Authority

and Public Housing Administration, Form No.

PHA-2172, Rev. Sept. 1, 1951, 107-110, 115, 118,

123(B), 124, 204, 205, 214, 215, 305(D), 308, 404,

407 .......................................................................... 13

Terms and Conditions Constituting Part II of Annual

Contributions Contract Between Local Authority

and Public Housing Administration, Form No.

PHA-2172, Rev. Sept. 1, 1951, § 106(B) .............. 12

IN T H E

Huttefc States Court of Appeals

For the Fifth Circuit

No. 16040

----------------o----------------

P rince H eyward, et al.,

Y.

Appellants,

P ublic H ousing A dministration, et al..

Appellees.

— -------------------------------------o — ----------------------------------- --

APPELLANTS’ BRIEF

Statement of the Case

The gravamen of the Complaint is that defendants, as

governmental officials, are enforcing a policy of racial

segregation in public housing projects in the City of

Savannah, Georgia, in violation of rights secured to plain

tiffs by the 5th and 14th Amendments to the Federal Con

stitution and by Federal Statutes, i.e., Title 42, United

States Code, § 1982 (formerly Title 8 U. S. C. 42) and Title

42, United States Code, §§ 1410(g), 1415(8)(c) (R. 9-10).

The jurisdiction of the court below was invoked pursuant

to Title 28, United States Code, §§1331 and 1343(3) and

Title 42, United States Code, § 1983 (formerly Title 8

U. S. C. 43) (R. 3).

Relief sought is 1) a declaration that defendants may

not pursue a policy of racial segregation in public housing

and a declaration regarding the legality of numerous prac

tices and procedures inherent in the enforcement of such

2

a policy, 2) an injunction enjoining all defendants from

enforcing the segregation policy and the practices inherent

therein, 3) an injunction also enjoining defendant Public

Housing Administration and its field office director, defend

ant Hanson, from giving federal financial aid and other

federal assistance to the Savannah Housing Authority for

the planning, construction, operation, or maintenance of

any project which excludes plaintiffs, solely because of

race and color, and 4) an award of $5,000 damages to

each plaintiff against each defendant (EL 11-14).

Plaintiffs-appellants, hereinafter referred to as plain

tiffs, are all adult Negro citizens of the United States and

of the State of Georgia, residing in Savannah, Georgia.

Each plaintiff has been or will be displaced from the site of

his or her residence to make way for construction of a

public housing project in Savannah known as Fred Wessels

Homes. Although each plaintiff meets all requirements

established by law for admission to public housing, each

was denied consideration for admission and admission to

Fred Wessels Homes and certain other public housing

projects limited by defendants to occupancy by white

families (R. 6, 9-10). Each plaintiff has a statutory

preference for admission to public housing as a displaced

and needy family. Plaintiffs bring this action on behalf of

themselves and all other Negroes similarly situated (R.

5-7).

Defendant-appellee, Public Housing Administration,

hereinafter referred to as defendant PHA, is a corporate

agency and instrumentality of the United States. Its

principal office is in the District of Columbia and the Com

missioner of PHA resides there. However, pursuant to

authority vested in it, PHA has established branch offices

in various states. It has a branch office in Atlanta, Georgia

known as the Atlanta Field of the PHA. Defendant-

appellee, Arthur R. Hanson, hereinafter referred to as

3

defendant Hanson, is the director of said office. PHA

administers the Federal low-rent housing program involved

in this case. United States Housing Act of 1937, as amended,

Title 42, United States Code, § 1401, et seq. (R. 8).

Defendant-appellee,, Savannah Housing Authority, here

inafter referred to as defendant SHA, is a public body

corporate which administers the low-rent housing program

of the City of Savannah, Georgia. Housing Authorities

Law of Georgia, 99 Ga. Code Annotated 1101 et seq. The

other defendants in this case are the members and the

executive director of the SHA (R. 8).

Pursuant to provisions of the United States Housing

Act of 1937, as amended, and the Housing Authorities Law

of the State of Georgia, six low-rent projects have been

built in Savannah and are presently in operation: Fellwood

Homes (Ga-2-1) with 176 units, Yamocraw Village (Ga-2-2)

with 480 units, Garden Homes Estate (Ga-2-3) with 314

units, Fred Wessels Homes (Ga-2-4) with 250 units,

Fellwood Annex (Ga-2-5) with 127 units and Garden Homes

Annex (Ga-2-6) with 86 units (R>. 41).

At the time of the filing of the Complaint in this action,

May 20, 1954, there were at least three remaining public

defense housing projects in Savannah. These projects

were built pursuant to provisions of various Federal enact

ments. Title to these projects was in the United States.

They were operated by the SHA under lease from the

United States acting through the Federal Public Housing

Authority or its successor PHA (PHA Exhibit 7). Since

the filing of the Complaint, PHA has conveyed title to two

of these projects to the SHA for use as low-rent projects;

these are Nathanael Green Villa, consisting of 250 units

(conveyed March 31, 1955) and Francis Bartow Place,

consisting of 150 units (conveyed June 1, 1955). A third

project, Deptford Place, was conveyed on June 17, 1953

for the purpose of eventually removing the dwelling units

4

thereon and conveyance of the land to the city for industrial

purposes (R. 35, 43-44).

With the exception of three of the above-named projects,

i.e., Yamocraw Village, Fellwood Homes and Fellwood

Annex, containing a total of 783 unite, all other public low-

rent housing projects in Savannah, i.e., Garden Homes

Estate, Fred Wessels Homes, Garden Homes Annex,

Nathanael Greene Villa, Francis Bartow Place, with a

total of 1050 units., are barred to qualified Negro families,

solely because of race and color. In addition, Deptford

Place is limited to white occupancy (R. 27, 31, 35).

Qualified Negro families are permitted to occupy a

certain specified percent of the units determined by applica

tion of an administrative formula known as the PH A

Racial Equity Formula (R. 33, 37). The determination

made as a result of application of this formula forms a

part of the contracts between PHA and SHA, Heyward

v. PHA (C. A. D. C.) 214 F. 2d 222.

As of August 30, 1955, 73 white families, whose applica

tions for admission have been reviewed and whose eligibility

for public low-rent housing has been determined, were

awaiting admission. As of the same date, 319 Negro

families similarly situated were awaiting admission (R.

36). Not one of the 250 families now living in Fred

Wessels Homes is a displaced family (R. 36).

A motion for summary judgment was filed on behalf

of PHA and Hanson (R. 38). A motion to dismiss and

an answer were filed on behalf of SHA and the other-

defendants (R. 15, 21). Both motions were heard on Sep

tember 30, 1955 (R, 74).

The court below granted the motion for summary judg

ment on the following grounds: 1) the complaint fails to

show that the matter in controversy as to each plaintiff

exceeds $3,000.00; 2) PHA and Hanson are not acting

under color of any state law; 3) court lacks venue of the

5

action under Title 28, United States Code, § 1391(b) in that

PHA is not a corporation doing business in the judicial

district within the meaning of Title 28, United States Code,

§ 1391(c) ; 4) plaintiffs lack sufficient legal interest in the

expenditure of Federal funds by PHA to give them stand

ing to challenge the validity of such expenditures; 5) that

PHA by placing in its annual contributions contract with

SHA a requirement that the latter shall extend preferences

in occupancy required by Title 42, United States Code,

§ 1410(g) has fulfilled its obligation under that statutory

provision; 6) in view of the fact that PHA has not pre

scribed any policy as to whether low-rent housing in

Savannah shall be occupied by any particular race but has

left the determination of that policy to the SHA, there is no

justiciable controversy between plaintiffs and PHA and

Hanson; and 7) since Hanson as Field Office Director of

PHA has no official function or duty with respect to dis

pensing or withholding of Federal funds to SHA, plaintiffs

fail to make out a claim on which any relief can be granted

against defendant Hanson (R. 47).

The court below granted the motion to dismiss on the

ground that “ the legal doctrine of separate but equal

facilities is still the law of the land and controls this case” ,

135 F. Supp. 217 (R. 51, 52).

From the orders entered granting the above motions,

plaintiffs appeal (R. 57).

Specification of Errors

The court below erred in granting the motion of defend

ants PHA and Hanson for summary judgment on the

grounds set forth in its order of October 15, 1955.

The court below erred in granting the motion to dismiss

on the ground that the doctrine of separate but equal

facilities is still the law of the land and controls this case.

6

ARGUMENT

I. Jurisdiction

One of the grounds upon which the court below granted

the motion of defendants PHA and Hanson for summary

judgment is that the complaint fails to show that the matter

in controversy as to each plaintiff exceeds $3,000. as re

quired by 28 IT. S. C. § 1331.

In this action, plaintiffs allege they have been denied

admission to Fred Wessels Homes, and certain other pub

lic housing projects, by these defendants, solely because

of race and color (R. 10). Plaintiffs’ right not to be

deprived of a public housing unit by these defendants

solely because of race and color is secured by the provi

sions of 42 H. S. C. § 1982, the requirements of 42 H. S. C.

§§ 1410(g) and 1415(8) (c), the due process clause of the

Fifth Amendment to the Federal Constitution and by the

public policy of the United States. Cf. Hurd v. Hodge,

334 U. S. 24; cf. Roberts v. Curtis, 93 F. Supp. 604; cf.

Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U. S. 497.

In civil rights actions at law, as in other actions at law,

the amount necessary for jurisdiction under § 1331 is deter

mined by the sum claimed in good faith by the plaintiff

seeking to redress the violation of his civil rights, Giles v.

Harris, 189 U. S. 475; Swafford v. Templeton, 185 U. S.

487; Wiley v. Sinkler, 179 U. S. 57. See, Hague v. C.I.O.,

307 U. S. 496, 507; cf. Smith v. AUwright, 321 U. S. 649;

cf. Nixon v. Condon, 286 U. S. 73; cf. Nixon v. Herndon,

273 U. S. 536.

In the Wiley case, supra, plaintiff sought redress against

election officials claiming that they had denied him the

right to vote in a congressional election. He sought

damages which he alleged were $2500. At that time, $2000.

was the required jurisdictional amount. The Supreme

7

Court held that since plaintiff alleged that his damages

exceeded $2000., the jurisdictional requirement had been

met.

In this case, plaintiffs allege that the amount in con

troversy as to each plaintiff exceeds $3000. exclusive of

interest and costs (R. 3) and pray damages in the amount

of $5000. for each plaintiff against each and all defend

ants (R. 13).

These allegations, as indicated by the Wiley case, clearly

meet the jurisdictional requirements of § 1331.

In civil lights cases, as in other cases, when injunction

is sought to restrain defendant from interfering with plain

tiff’s right, there are two criteria which have been estab

lished by the courts for determining amount or matter in

controversy: 1) the value of that which the plaintiff seeks

to gain or protect, and, 2) the value of what defendant will

lose should requested relief be granted, Smith v. Adams,

130 U. S. 167; Armstrong v. Townsend (S. D. Ind.), 8 F.

Supp. 953; Cheseapeahe <& Del. Canal Co. v. Gring (C. A.

4th), 159 F. 662, cert, den., 212 U. S. 571. See Annot. 30

ALR 2d 602, 619 (1953).

The result of applying either criterion need not be the

same. See Mississippi <& Missouri R.B. v. Ward, 67 U. S.

(2 Black) 485, where the defendants’ criterion was adopted.

See Kelley v. Lehigh Nav. Coal Co. (C. A. 3d), 151 F. 2d

743, cert, den., 327 U. S. 779, where plaintiffs’ criterion

was employed.

But the overwhelming majority of eases have employed

the plaintiffs’ criterion, Scott v. Donald, 165 U. S. 107;

Bitterman v. Louisville & N. B. Co., 207 U. S. 205; Glen-

wood Light <& Power Co. v. Mutual Light, Heat and Power

Co., 239 U. S. 121; Ebensberger v. Sinclair Refining Co.

(C. A. 5th), 165 F. 2d 803, cert, den., 335 U. S. 816; Lans-

den v. Hart (C. A. 4th), 180 F. 2d 679. See also Annot. 30

8

ALR 2d 602, 621 (1953) for collection of cases employing

the plaintiffs’ point of view criterion.

Employing plaintiffs’ criterion to the instant case, each

plaintiff here seeks to gain a public housing family unit.

The value of such a unit, per se, as well as to each plaintiff,

clearly exceeds $3,000. The record shows that maximum

cost of construction and equipment per room in Fred Wes-

sels Homes is to be $1,750. (See Exhibit 1. pg. 1, at

tached to Slusser Affidavit and sent up to the court in

original form.) A family unit would obviously consist

of at least three rooms (R, 35). Thus construction cost

of even the smallest family unit exceeds the jurisdictional

amount.1

The group of cases which are perhaps most closely

analogous to the instant case are those in which plaintiff

has sought specific performance of a contract for the sale

of real property. In these cases the courts have said that

the test of jurisdiction is the value of the property which

plaintiff seeks to acquire, and have rejected claims that

plaintiff failed to meet the requisite jurisdictional amount

because he did not show that his damages would exceed

$3,000 if defendant failed to perform his contract. Eb'ens-

berger v. Sinclair Refining Co., supra.

It should be noted at this point that no formal plea

to the jurisdiction was made by defendants PHA and

Hanson. Bitterman v. Louisville & N. R. Co., 207 U. S. 205,

224. The motion filed by them was a motion for summary

judgment on the ground that there is no genuine issue as

to any material fact (R. 38). Their motion is supported

by an affidavit which does not challenge the jurisdictional

amount (R. 39). These defendants raised a question re

garding jurisdictional amount by brief and oral argument

(R. 79).

1 See Journal of Housing, Vol. 13 No. 4 April 1956 p. 134 where

it is stated that construction costs of Fred Wessels Homes were

$1538 per room, or about $7234 per unit.

9

While it is true that where challenged the burden is on

plaintiff to show that the amount in controversy exceeds

$3,000, to justify dismissal where there is an adequate

formal allegation of amount, it must appear to a legal

certainty that the claim is for less than the jurisdictional

amount. City of Memphis v. Ingram (C. A. 8th), 195 F. 2d

338. Here, on the contrary, it seems clear that the amount

in controversy exceeds the requisite $3,000.

Applying the defendants’ point of view, there appears

to be still another basis for jurisdiction. One form of

relief sought here is an injunction enjoining PHA and

Hanson from giving federal financial and other federal

assistance to 8HA for projects from which plaintiffs are

excluded solely because of race and color (R. 13). By the

admission of these defendants at least three of these proj

ects are limited to white occupancy (R. 78). The financial

assistance given by PHA to the SHA is in the form of a

loan and a subsidy (R. 78). The loan which PHA agreed

to make to finance Fred Wessels Homes (GA-2-4), Yama-

craw Village (GA-2-5) (Negro), and Garden Homes An

nex (GA-2-6) (white) as of May 8, 1953 was $3,337,019.00

(Exhibit 1, Amendatory Agreement No. 3 attached thereto).

The rate of interest charged by PHA on this loan to SHA

appears to be 2%% per annum (Exhibit 1, pg. 1).

It thus appears that if plaintiffs succeed in enjoining

these defendants from giving such financial aid in the

future (R. 36), PHA would lose the interest it would earn

on such loans which is clearly in excess of $3,000 per annum

on a single project loan.

In Nueces Valley Townsite Co. v. McAdoo (W. D. Tex.),

257 Fed. 143, the plaintiff sought to enjoin acts of a Fed

eral governmental official, alleging that if the injunction

was granted, the government would save $400 per month

for 21 months. The court held that this constituted the

requisite jurisdictional amount. Thus another view of the

10

amount in controversy may be expressed in terms of the

amount of money which PHA would save by being enjoined

from furnishing loans and subsidies for the construction

of segregated projects. From the Annual Contributions

Contracts it is clear that the amount so saved would

exceed $3,000 (Exhibit 1).

II. Venue

PHA, being successor to the United States Housing-

Authority, is a public body corporate which Congress has

authorized to sue and to be sued with respect to its func

tions under the United States Housing Act of 1937 and the

National Defense Housing Projects Acts [42 U. S. C. 1403a,

1404a, 1405a; 5 U. S. C. 133y-133y-16, Reorganization Plan

No. 3 effective July 27, 1947]. It may, therefore, be sued

in the same manner as any other corporation. Sigora v.

Slusser, (D. C. Conn.), 124 F. Supp. 327; cf. Keifer

v. Reconstruction Finance Corp., 306 U. S. 381; cf. Federal

Housing Administration v. Burr, 309 U. S. 242; cf. Seven

Oaks Inc.'Y. Federal Housing Administration (C. A. 4th),

171 F. 2d 947.

The court below ruled that venue was improper as to

PHA since it is not doing- business in the judicial district

within the meaning of 28 U. S. C. § 1391(c).

There is no question raised as to the residence of defend

ants SHA, its members, and executive director. They

reside in the southern judicial district of Georgia. There

is no question that defendant Hanson resides in Atlanta

or the northern judicial district of the state. There is

apparently no question that PHA is doing business in

Atlanta where its Field Office is located. By virtue of an

amendment to the Judicial Code in 1948, 28 U. S. C. 1391(c),

the judicial district in which a corporation is doing busi

ness “ shall be regarded as the residence of such corpora

tion for venue purposes.” The question raised by the

11

ruling of the court below is whether it is necessary to find

that P ITA is doing business in the southern district before

it can become amenable to suit there.

In this action, suit is brought against different defend

ants “ residing” in the same state but in different judicial

districts thereof. In such case, the Judicial Code provides,

in language too clear to be misunderstood, that suit may be

brought in any of such districts, except where the suit is

one of a local nature. 28 U. S. C. § 1392; Jones v. Fox Film

Corp. (C. A. 5th), 68 F. 2d 116; Smith v. Merrill (C. A.

5th), 81 F. 2d 609; Downs v. Wall (C. A. 5th), 176 Fed. 657;

Lisle Mills, Inc. v. Arkay Infants Wear (E. D. N. Y.), 84

F. Supp. 697; Heard v. Ouachita Parish School Board

(W. D. La.), 94 F. Supp. 897. Therefore, in deciding

whether venue is proper as to PHA, appellants are not

limited to a determination whether, under the facts of this

case, PHA is doing business in the southern district of

Georgia. If PHA was doing business anywhere in Georgia

at the time this suit was instituted, then venue is properly

laid in the southern district where other defendants reside.

In this case, appellants assert rights secured by the

Constitution and laws of the United States (R. 3). This

is therefore not a case in which federal jurisdiction is

founded solely upon diversity of citizenship. In such a

case, determination as to what constitutes doing business

by a corporation for venue purposes is to be governed “ by

basic principles of fairness.” Lone Star Package Car Co.

v. Baltimore & Ohio R. Co. (C. A. 5th), 212 F. 2d 147;

International Shoe Co. v. Washington, 326 U. S. 310;

Travelers Health Assoc, v. Com. of Va., 339 U. S. 643;

Perkins v. Benquet Consol. Min. Co., 323 U. S. 437. Under

the basic principles of fairness established by the United

States Supreme Court in the International Shoe Co. case

and followed by this Court in the Lone Star Package Car

case, the facts of this case require that the court below

exercise jurisdiction over PHA.

1 2

PHA has established in the City of Atlanta, Georgia, a

Field Office, the director of which is defendant Hanson.

The record in this case discloses that this office has been

in existence at least since March 19, 1952 when an Annual

Contribution’s Contract between SHA and PHA was en

tered into regarding the planning, construction, operation

and maintenance of Fred Wessels Homes and other

projects. The agreement is signed by the then Director

of the Atlanta Field Office for PHA, and an amendment

thereto dated March 18, 1953 was signed by defendant

Hanson (Exhibit 1). The record also discloses that con

tracts between PHA and SHA have existed since November

25, 1940 and that the latest contract between SHA and

PHA entered into on January 21, 1954 regarding the opera

tion of existing projects which were the subject of a 1940

contract, was signed by the Acting Director of the Atlanta

Field Office (Exhibit 1). It is thus clear that the function

of the Atlanta Field Office of PHA is to enter into con

tracts with local public housing agencies in Georgia cover

ing planning, construction, operation and maintenance of

low-rent projects.

Part I of the Annual Contributions Contract reveals

the nature and extent of PHA financial involvement in the

housing involved in this controversy (Exhibit 1).

Part II of the Annual Contributions Contract reveals

the detailed involvement of PHA in planning, construction,

operation and maintenance of these projects (Exhibit 1).

Examination of this latter document demonstrates that

SHA is subject to complete regulation and control by PHA.

Under the terms of this agreement, for example, PHA

approves the plans and specifications of the local authority

for construction of the project,2 all construction contracts

2 Term and Conditions Constituting Part II of Annual Contri

butions Contract Between Local Authority and Public Housing

Administration. Form No. PHA-2172, Rev. Sept. 1, 1951, § 106(B).

13

including bids for same,3 prevailing wages to be paid by

local authority to all architects, technical engineers, drafts

men, and technicians employed in the development of the

projects;4 PHA prescribes the forms to be used by con

tractors and subcontractors in preparing their payrolls and

instructions with respect to same; 5 6 PHA approves form

of contractor’s release from liability to local agency f PHA

approves salaries paid to local agency personnel,7 develop

ment cost,8 budgets,9 income limits and rent schedules; 10

PHA approves acceptance of work done under construction

or equipment contract,11 insurance coverage,12 settlement

for damaged or destroyed project,13 and sale of excess

property.14

On the question whether PHA does business in Savan

nah, it should be noted that Section 121 of Part II of the

Contract requires that “ The local authority shall provide

and maintain or require that there shall be provided and

maintained, during the construction of each Project, ade

quate facilities at the site for the use of PHA’s representa

tives who may be assigned to the review of such Project.”

It should also be noted that the affidavit of PHA Com

missioner Slusser, which supports the motion for summary

judgment, admits that by virtue of the contracts existing

between PHA and SHA, PHA has control over the projects

here in controversy to the extent indicated and that this

3 Id., §§ 107. 108, 109, 110.

*Id., § 115.

6 Id., § 118.

6 Id,., § 123(B).

7 Id., §215.

8 Id., § 404.

9 Id., § 407.

10 Id., §§ 204, 205.

11 Id., § 124.

12 Id., § 305(D).

13 Id., § 214.

14 Id., §308.

u

control extends to the occupancy of such projects as re

quired by the United States Housing Act of 1937, as

amended, and the regulations promulgated by PHA pur

suant thereto (E. 41).

And finally, it should be noted that PHA’s Eacial

Equity Formula is the basis for the limitation of Fred

Wessels Homes and certain other projects to white occu

pancy (E. 27, 31, 33, 36-37).

In short, the record clearly exhibits that there are six

projects which have been built in Savannah pursuant to

contracts entered into by PHA and SHA (Exhibit 1); that

since the filing of this suit PHA has turned over to SHA

two former defense public housing projects located in

Savannah for use as low-rent projects (E. 43); that the

planning, construction, operation and maintenance of

projects entails financial involvement on the part of PHA

amounting to millions of dollars; that the PHA interest

in these projects is substantial and continuing; that PHA

exercises control over these projects, including occupancy;

and that the limitation of certain projects to white occu

pancy is a PHA determination.

In International Shoe Co. v. Washington, supra, the

Supreme Court said at 317:

“ ‘Presence’ in the state . . . has never been

doubted when the activities of the corporation there

have not only been continuous and systematic, but

also give rise to the liabilities sued on, even though

no consent to be sued or authorization to an agent to

accept service of process has been given.”

15

III. Justiciable Case or Controversy

A. Nature and Extent of PH A Participation In T he

Lim itation O f Certain Projects To W hite O ccupancy.

PHA’s racial policy is as follows:

“ The following general statement of racial policy

shall be applicable to all low-rent housing projects

developed and operated under the United States

Housing Act of 1937, as amended:

1. Programs for the development of low-rent

housing in order to be eligible for PHA assistance,

must reflect equitable provision for eligible families

to all races determined on the approximate volume

and urgency of their respective needs for such hous

ing.

2. While the selection of tenants and assigning

of dwelling units are primarily matters for local

determination, urgency of need and the preferences

prescribed in the Housing Act of 1949 are the basic

statutory standards for the selection of tenants.” 15 16

In accordance with this policy, the Development Pro

gram., 1S< which is a form prepared by PHA for use by SHA

in malting application for federal assistance and federal

approval of its program, required SHA to indicate the

racial composition of each federally-aided project and each

proposed federally-aided project and to show, by the number

of units alloted or to be alloted to white and non-white

families, that equitable provision for eligible families of

both races have been or will be provided, determined on

the approximate volume and urgency of their respective

needs for such housing. This determination must be based

15 HHFA PHA Low-Rent Housing Manual, Section 102.1

February 21, 1951.

16 Form PHA-1954 Rev. July 1950, referred to in Exhibit 1,

Part I, Section 2.

16

solely on the volume of substandard housing occupied by

each group. The Development Programs submitted by

SHA for approval, and which constitute the basis upon

which federal financial assistance is being given to Savan

nah, indicated that Fred Wessels Homes and two other

projects would be limited to white families and that three

others would be limited to Negro occupancy. They also

indicated that equitable provision for both races, determined

on the approximate volume and urgency of their respective

need, would require an allocation of 63.7% of the dwelling

units to non-white families and only 36.7% of the dwelling

units to white families. Before any federal financial assist

ance was granted, PHA, as required by law and its own

rules and regulations, approved these Development Pro

grams clearly indicating these limitations and indicating

that PHA’s racial equity requirements would be met by

the above-percentage allocations. These Development Pro

grams became a part of Part One of the Annual Contribu

tions Contracts entered into between PHA and SHA.

Heyward v. PHA (C. A. D. C.) 241 F. 2d 222.

The nature of the role played by the PHA with respect

to local racial policies can be pinpointed in the following

manner: If a local authority is interested in securing

approval for a Development Program, it has two alterna

tives. First, it can agree to make all low-rent housing

projects to be constructed by it available for occupancy to

all racial groups without discrimination or segregation of

any kind. However, if such a plan is unacceptable to the

local authority, it has a second alternative. It can agree

to provide a specified number of units for the occupancy

of white families and a specified number for the occupancy

of Negro families, the families to be housed on a racially

segregated basis. If the percentage for white families and

the percentage for Negro families meet the standards for

achieving racial equity determined by the PHA, then the

Development Program is approved insofar as this aspect

is concerned. Once it is approved, it becomes a part of the

17

contractual relationship between PHA and SHA. There

ie, of course, logically a third possible alternative. The

local authority could conceivably have complete freedom

of choice. But a local housing authority has no such free

dom, and it is the determination of PHA which deprives

local authorities of such freedom.

In the instant case, SHA was obviously unwilling to

agree to the first alternative noted above—i.e., open oc

cupancy. Therefore, it was required by PHA to agree

to the second alternative plan, i.e., segregated housing with

a specified percentage allocation to white families and to

Negro families. For short-hand reference, we shall term

the second plan the “ segregation-quota” plan. Once the

SHA agreed to the “ segregation quota” plan, and once

the number of units for white and the number of units for

Negroes was agreed upon and thus made a part of the

contractual relationship between the parties, SHA has

no contractual right to deviate. SHA obviously has no

right to lease to white persons all units in all projects

including those units designated exclusively for Negroes.

Similarly, it has no right to lease all units in all projects

to Negroes. In other words, SHA has no right to deviate

in any way from the quota system agreed upon. If SHA

decided to integrate projects designated exclusively for

whites, while leasing projects designated exclusively for

Negroes in conformance with the overall plan, then Negroes

in Savannah would be securing a disproportionate number

of units in violation of PHA’s racial equity formula. Such

action by SHA would be in violation of its contract.

A hypothetical situation may help clarify the above

analysis. Assume that a local housing authority chooses

the “ segregation-quota” plan of development. Assume

further that the local authority agrees with PHA’s deter

mination that an allocation of 200 units for whites and 200

units for Negroes will provide racial equity. This agree

ment of course becomes a part of the contractual relation

ship between the local authority and PHA. Assume further

18

that the Negro project is completed first and that 200 Negro

families were given occupancy. If 50 additional Negroes

were to apply to the local housing authority and were able

to prove that they were more qualified and had a higher

priority than 50 white families who were scheduled to be

given occupancy in the 200 unit white project, could the

local housing authority admit those 50 Negro families

along with 150 white families to the project originally

designated for whites? Plaintiffs submit that the local

authority would have no contractual right to admit these

50 Negroes because such an act on the part of the local

authority would be in violation of the racial equity formula

agreed upon, and required by PHA. Thus, it is the PHA

which determines whether any given Negro family can be

admitted to Fred Wessels Homes.

Aside from PHA’s racial equity formula which resulted

in the racial limitations complained of here, there is still

another basis upon which this Court may find that the

racial limitations are a result of PHA action.

There is, as demonstrated above, a sufficiently close

relationship between PHA and SHA to make it necessary

for this Court to consider whether PHA has violated

rights secured to plaintiffs by the Constitution and laws of

the United States, cf. Public Utilities Commission v.

Pollack, 343 U. S. 451. Here we have a public corporation

which has a monopoly on all decent, safe and sanitary

housing available in Savannah at rents charged for public

housing. [There must be a gap of at least 20 per cent

between the upper rental limits for admission to public

housing and the lowest rents at which private enterprise

unaided by public subsidy is providing housing. Title 42

U. S. C. 1415(7)(b)]. This monopoly position is made

possible by financial assistance from the federal govern

ment [annual contributions are given to SHA by PHA to

help maintain the low rent character of the projects]. This

public corporation is closely regulated by a federal agency,

19

as demonstrated, supra. It is closely regulated by PHA

in order to assure that this housing is made available only

to qualified low income families. The federal agency in

this case has the duty, imposed upon it by the federal act,

to protect eligible low income families, e.g., it must insert

in its contract with SHA a provision requiring SHA to

abide by the statutory preferences for admission [Title 42

U. S. C. 1410(g), 1415(8) (c)]. The federal agency in this

case has the power to make all rules and regulations neces

sary to carry out its functions, powers and duties [Title 42

U. S. C. 1404(a)], Finally, the federal agency is under

a duty, imposed by the Constitution, laws, and public policy

of the United States, to prevent discrimination wherever

the federal authority extends. It is under a duty imposed

by Congress to enforce the requirements of 42 U. S. C.

§§ 1410(g) and 1415(8) (c). Yet, despite this relationship,

PHA has permitted, and has specifically approved the racial

segregation policy. Plaintiffs contend that under these

circumstances, the action of PHA in permitting and approv

ing this policy must be regarded as the action of PHA.

cf. Public Utilities Commission, v. Pollack, supra.

The Pollack case arose out of the practice of Capital

Transit Co., a street railway company, in receiving and

amplifying radio programs through loud-speakers in its

passenger vehicles. Capital Transit is a privately owned

public utility owning an extensive railway and bus system

which it operates in the District of Columbia under a

franchise from Congress. Its services and equipment are

subject to the regulation of the Public Utilities Commis

sion of the District of Columbia. On its own motion, the

Commission ordered an investigation of Capital Transit’s

practice in order to determine whether the use of such

receivers was “ consistent with public conveniences, public

comfort and safety.” Two protesting passengers were

allowed to intervene. The Commission found that the use

of these radios was not inconsistent with public conveni

20

ence, comfort, etc., and dismissed its investigation. The

two protesting passengers appealed. The District Court

denied relief, but on appeal the Court of Appeals reversed.

The latter court held that this forced listening deprived

passengers of liberty without due process of law in viola

tion of the Fifth Amendment. In order for the court to

reach such a conclusion, however, it was necessary for it

to find governmental action rather than mere private

action. The Court of Appeals found the necessary gov

ernmental action in the action of Congress in giving Capital

Transit a franchise to use the streets and a virtual mon

opoly of the entire local business of mass transportation

of passengers in the District of Columbia. In this way,

Congress was really forcing persons dependent on Capital

Transit to listen to the radio. In addition, the Court of

Appeals found governmental action in the fact that the

Commission had sanctioned the conduct of Capital Transit

by dismissing its investigation and failing to take action

to prohibit the broadcasts. Pollack v. Public Utilities Com

mission (C. A. D. C.), 191 F. 2d 450.

On certiorari, the Supreme Court reversed on the

ground that no constitutional right of the passengers had

been violated. From plaintiffs point the important part

of the opinion is that dealing with the presence of govern

mental action. The Supreme Court agreed with the con

clusion of the Court of Appeals that there was a sufficiently

close relationship between the Federal Government and

the radio services to make it necessary to consider whether

the 1st and 5th Amendments had been violated. The perti

nent part of the Supreme Court’s opinion is set forth

below:

“ We find in the reasoning of the court below a

sufficiently close relation between the Federal Gov

ernment and the radio service to make it necessary

for us to consider those Amendments. In finding this

relation we do not rely on the mere fact that

21

Capital Transit operates a public utility on the

streets of the District of Columbia under authority

of Congress. Nor do we rely upon the fact that,

by reason of such federal authorization, Capital

Transit now enjoys a substantial monopoly of street

railway and bus transportation in the District of

Columbia. We do, however, recognize that Capital

Transit operates its service under the regulatory

supervision of the Public Utilities Commission of

the District of Columbia which is an agency author

ized by Congress. We rely particularly upon the

fact that that agency, pursuant to protests against

the radio program, ordered an investigation of it

and, after formal public hearings, ordered its inves

tigation dismissed on the ground that the public

safety, comfort and convenience were not impaired

thereby” (at 462).

A close reading of the above passage yields the follow

ing interpretation: The Court gave either no considera

tion or minimal consideration to the fact that Capital

Transit used the streets of the District of Columbia under

authority of Congress and the fact that, by reason of such

authorization, Capital Transit enjoyed a substantial mon

opoly. Substantial consideration, however, was given to

the fact that Capital Transit operates under the regulatory

supervision of a governmental commission. And greatest

weight was given to the fact that a governmental agency,

with power to prohibit or to permit this activity, permitted

it to continue.

22

B. By Placing- Requirem ents o f T itle 42, U nited States

Code, §§ 1 4 1 0 (g ) and 1 4 1 5 (8 ) (c ) in its Contract w ith

SHA, PH A H as Not D ischarged Its O bligation.

PHA contended in the court below that its only obliga

tion under Title 42, United States Code, §§ 1410(g) and

1415(8) (c) is to insert these provisions in its contract with

SHA. This contention, although contrary to the state

ments made by PHA Commissioner Slusser in his affidavit

in support of motion for summary judgment (R. 41, 44)

and the regulations promulgated by PHA itself (R. 37),

was sustained by the Court below (R. 47).

Title 42 U. S. C. 1410(g) provides that every contract

made by PHA with a local agency for annual contributions

shall require that the local agency, as among eligible low

income families for occupancy, shall extend first preference

to displaced families, with priority among such families to

disabled veterans. PHA argued below that Congress in

tended nothing by this requirement except a mere direc

tive to PHA as to the expenditure of federal funds, and it

was not intended by Congress to create any legal rights in

third persons such as plaintiff. Not only was it the express

intention of Congress by this requirement to give first

preference for admission to displaced families, but it was

the express intention of Congress that PHA have the

duty to see to it that this requirement is complied with

by the local authority.

With respect to this requirement the Senate Committee

said:

“ Families who are displaced or are about to be

displaced by public slum-clearance or redevelopment

projects will be given a first preference for admis

sion to low-rent housing.” 17

17 Sen. Rep. No. 84, 81st Cong., 1st Sess., 2 U. S. Code Con

gressional Service 1569 (1949).

23

With respect to this requirement and PHA’s duty the

Committee said:

“ The prime responsibility for the provision of

low-rent housing is thus in the hands of the various

localities. The role of the Federal Government is

restricted to the provision of financial assistance to

the local authorities, the furnishing of technical aid

and advice, and assuring compliance with statutory

requirements.” 18 (Emphasis added.)

Title 42 U. S. C. § 1415(8)(e) requires that PHA’s

contract with SHA provide that in initially selecting ten

ants, SHA shall be required to give preference to families

with the most urgent housing needs and that thereafter

consideration must be given to the urgency of such needs.

With respect to this requirement the Senate Committee

had this to say:

“ Moreover, in the initial selection of tenants for

a project, the local authority will be required to give

preference to families with the most urgent housing

needs. Thereafter, consideration must be given to

the urgency of such needs.” 10

Therefore, it is clear that Congress intended to confer

a right on displaced and needy families, i.e., a right to a

first preference to admission to low-rent housing. It se

cured this right by requiring that it be made a part of

PHA’s contract with every local agency. The legal sig

nificance of this is that by so requiring, the plaintiffs and

other displaced families could sue as third party bene

ficiaries of the provision. In this case PHA had admittedly

inserted this requirement in its contract with SHA. cf.

Young v. Kellex Corp. (E. D. Tenn.), 82 F. Supp. 953;

cf. Crahb v. Weldon Bros. (S. D. Iowa), 65 F. Supp. 369,

rev. on other grds., 164 F. 2d 797. 18 19

18 Id. at 1566.

19 Id. at 1570.

24

C. Plaintiffs H ave Sufficient Legal Interest In Ex

penditure O f Funds By PH A To G ive Them Standing

To C hallenge V alid ity o f Such Expenditures.

1. N ature and Extent o f P H A ’s Financial A ssistance.

PHA’s financial assistant to a project in Savannah may

precede the actual construction of a project and continue

for as long a period as sixty years after its construction.

PHA is authorized to make loans to local public housing

agencies.20 These loans may be made for the purpose of

assisting the local agency in defraying the costs involved

in developing, acquiring or administering a project.21 PHA

may therefore commence involving the federal government

financially by making a preliminary loan to the local agency

in order that it may have the funds with which to proceed

to make plans for the proposed project and to conduct any

necessary surveys in connection therewith.22 PHA may

then make a further loan which enables the local agency

to meet the cost of construction and to repay the prelimi

nary loans.23 It may even loan money to pay any costs

in administering the project.24

PHA is authorized by the basic enactment to specify

in a contract with a local agency that it will contribute a

fixed sum annually over a predetermined period of years

“ to assist in achieving and maintaining the low-rent char

acter” of the project.25 PHA may therefore commit the

federal government to financially subsidizing a project,

after it is constructed, for a period as long as sixty years.26

20 Title 42 U. S. C. § 1409. Loans may not exceed 90% of

development or acquisition cost.

21 Ibid.

22 Title 42, U. S. C. § 1415(7) (a).

23 Ibid., and Title 42, U. S. C. §1409.

24 Id., § 1409.

25 Id., § 1410(a).

20 Id., § 1410(c).

25

From this subsidy the local agency may presumably repay

any monies loaned to it by the federal government for

construction of the project or in connection with its admin

istration.

The annual contribution made by PHA is one of two

methods provided whereby the federal government may

subsidize a public housing project. The alternate method

of effecting a federal subsidy provided for in the act pro

vides for a capital grant to a local agency in connection

with the development or acquisition of a project which

will thereby enable it to maintain the low rent character

of the project.27 PHA may make a capital grant in any

amount which it considers necessary to assure the low rent

character of the project.28 It may, therefore, make a capi

tal grant to a local agency which will pay the entire cost

of development or acquisition of a project.

In addition to this financial assistance which may be

given to a local agency, PHA is further authorized to in

volve the federal government financially in the event of

any foreclosure by any party on, or in the event of any sale

of, any project in which the federal government has a

financial interest.29 In the event of foreclosure, PHA may

bid for and purchase such project, or it may acquire and

take possession of any project which it previously owned

or in connection with which it has made a loan, annual

contribution or capital grant. In such case it may com

plete the project, administer the project, pay the principal

of and interest on any obligation issued in connection with

the project, thus further involving the federal government

financially.

Finally, in the event of any substantial contractual

default on the part of the local agency, PHA may involve

27 Id., § 1411(a).

28 Ibid.

28 Id., § 1413.

26

the federal government to the extent of taking title or

possession of a project as then constituted and must involve

the federal government further financially by continuing

to make annual contributions available to such projects to

pay the principal and interest on any obligation for which

these contributions have been pledged as security.30

2. Nature o f P laintiffs’ Interest In PH A Expenditures.

There can be no doubt that Fred Wessels Homes and

the other all-white projects involved here were made pos

sible by PHA expenditures and by PHA agreements to

make further expenditures (Exhibit 1). A part of the

relief against PHA and Hanson which is sought is a pro

hibiting injunction against the use of federal funds for

the construction and maintenance of such projects. The

court below ruled that plaintiffs do not have standing to

challenge such expenditures (B. 47).

The expenditures by PHA constitute more than minor

assistance—the expenditure of federal funds makes the

illegal projects possible. By these expenditures, PHA

knowingly supplies the state agency with the means whereby

the latter can effectively discriminate in violation of the

Fourteenth Amendment. In doing so, PHA flagrantly vio

lates plaintiffs’ rights and the public policy of the United

States. There is a firm basis in the common law to support

plaintiffs’ contention that a justiciable case or controversy

exists. See Joint Anti-Fascist Refugee Comm. v. McGrath,

341 U. S. 123, 159. For example, it has long been the law

of unfair competition that one who furnishes another with

the means of consummating a fraud is also guilty of unfair

competition. See, Federal Trade Commission v. Wins ted

Hosiery Co., 258 U. S. 483, 494. Section 876 of the Bestate-

ment of Torts expresses general principles which are firmly

imbedded in the common law.

30 Id., § 1421a.

27

“ Section 876. Persons Acting in Concert

For harm resulting to a third person from the

tortious conduct of another, a person is liable if

he * * *

“ (b) knows that the other’s conduct constitutes

a breach of duty and gives substantial assistance or

encouragement to the other so to conduct himself, or

“ (c) gives substantial assistance to the other in

accomplishing a tortious result and his own conduct,

separately considered, constitutes a breach of duty

to the third person.’’

The above principles can be used by analogy to demon

strate that even if the injury which plaintiffs receive origi

nates from the unlawful conduct of the SHA, PHA’s par

ticipation nevertheless can be considered a legal cause of

plaintiffs’ injury.

As a result of the expenditure of funds for an all-white

housing project in Savannah, plaintiffs are deprived of

federally-aided housing solely because of their race and

color. Plaintiffs can therefore show “ a direct dollar s-and-

cents injury” from the mere disbursement of federal funds.

Dorewms v. Board of Education, 342 U. S. 429, 434. If

plaintiffs were suing here as mere taxpayers, then it might

be said that their interest in the expenditures are too con

tingent and infinitesimal to be the subject of judicial action.

Massachusetts v. Mellon, 262 U. S. 447. But plaintiffs do

not sue as mere taxpayers here. They bring this action on

behalf of themselves and on behalf of all other qualified

low-income Negro families similarly situated. Their in

terest is that of families who would suffer a direct pecuni

ary loss by the improper expenditure of federal funds

which Congress intended be used to provide housing for

the class which plaintiffs represent, i.e., qualified low in

come families. In addition, this deprivation of federally-

28

aided housing, solely because of race and color, violated

rights secured to these plaintiffs by Constitution and laws

of the United States.

The fact that the funds involved are not actually dis

pensed by defendant Hanson or his office, but by the Wash

ington office of PHA is not a material. The fact is that

defendant Hanson must approve all requests made by

SHA before the Washington office will pay (Exhibit 2

attached to Slusser affidavit and sent up to this Court in

original form).

IV. The Separate But Equal Doctrine

The court below ruled that the complaint be dismissed

as to defendants SHA, its officers and members on the

ground that “ the legal doctrine of separate but equal

facilities is still the law of the land and controls this case.”

This ruling is clearly erroneous. The separate but equal

doctrine has never been extended to property rights.

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60, 81. Application of the

separate but equal doctrine here deprives plaintiffs of the

right to lease certain units of public housing, which are

leased to qualified applicants by public officials, solely

because of plaintiffs’ race and color.

The right to lease real property free from govern-

mentally imposed racial restrictions is a right not only

secured by the due process and equal protection clauses of

the Fourteenth Amendment to the Federal Constitution

but is secured by a specific Federal Civil Rights Statute,

Title 42 U. S. C. § 1982. Detroit Housing Commission v.

Lewis (C. A. 6th), 226 F. 2d 180; Jones v. City of Ham-

tramck (S. D. Mich), 121 F. Supp. 123; Vann v. Toledo

Metropolitan Housing Authority (N. D. Ohio), 113 F. Supp.

210; Housing Authority of San Francisco v. Banks, 120

Cal. App. 2d 1, 260 P. 2d 668, cert, den., 347 U. S. 974;

29

Seawell v. McWhithey, 2 N. J. Super. 255, 63 Atl. 2d 542,

rev. on other grds., 2 N. J. 563, 67 Atl. 2d 309; Taylor v.

Leonard, 30 N. J. Super. 116, 103 Atl. 2d 633.

Cf. Buchanan v. War ley, 245 U. S. 60; City of Birming

ham v. Monk (C. A. 5th), 185 F. 2d 859, cert, den., 341 U. S.

940; Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1.

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, a p p e llan ts subm it that the

judgments below granting m otion fo r sum m ary ju d g

ment and motion to dism iss shou ld be rev ersed .

Respectfully submitted,

Constance B aker M otley,

T hurgood Marshall,

107 West 43rd Street,

New York 36, N. Y.

A. T. W alden,

200 Walden Building,

Atlanta 3, Georgia.

F rank D. R eeves,

473 Florida Avenue,

Washington, I). C.

Attorneys for Appellants.