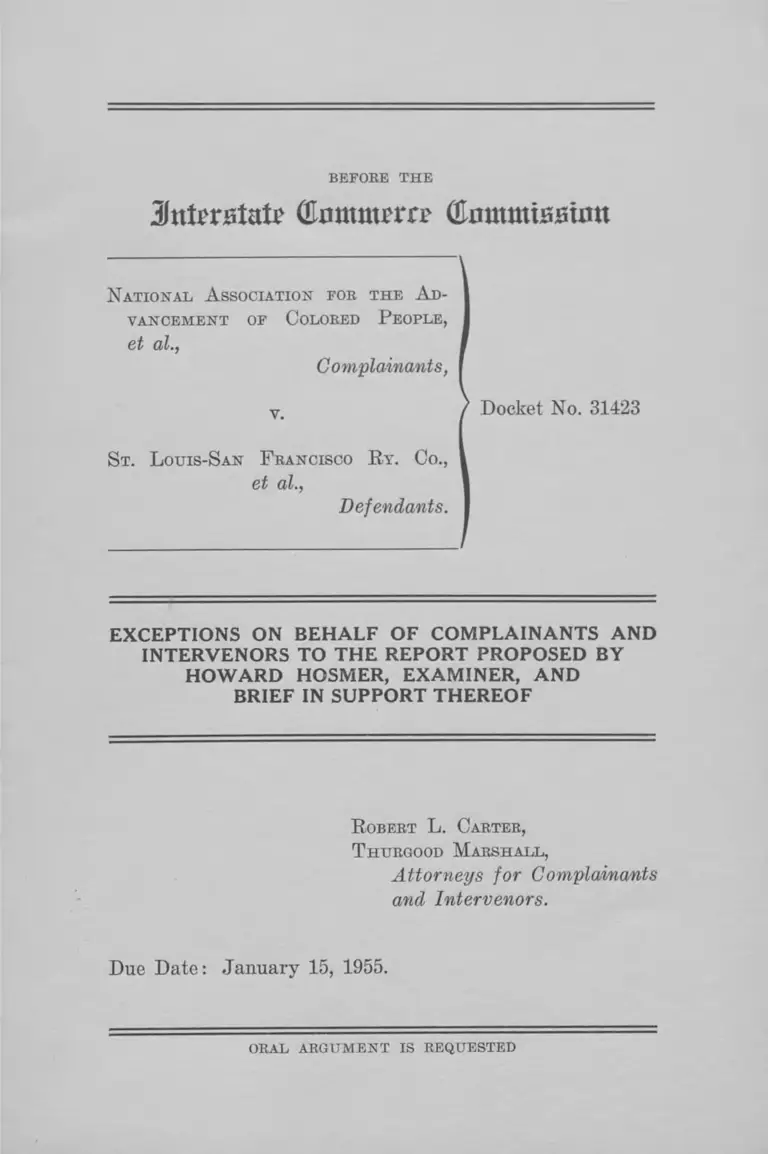

NAACP v. St. Louis-San Francisco RY. Co. Exceptions on Behalf of Complainants and Intervenors to the Report

Public Court Documents

January 15, 1955

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. NAACP v. St. Louis-San Francisco RY. Co. Exceptions on Behalf of Complainants and Intervenors to the Report, 1955. 09026440-bf9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/6d3be749-25b9-4aa4-abb2-f43ed5d433c0/naacp-v-st-louis-san-francisco-ry-co-exceptions-on-behalf-of-complainants-and-intervenors-to-the-report. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

BEFOBE THE

31 ttlmitali' (Cmmm'rrr Commtajeton

N ational A ssociation fob the A d

vancement of Colobed People,

et al.,

Complainants,

v.

St. L ouis-San F bancisco Ry. Co.,

et al.,

Defendants.

Docket No. 31423

EXCEPTIONS ON BEHALF OF COMPLAINANTS AND

INTERVENORS TO THE REPORT PROPOSED BY

HOWARD HOSMER, EXAMINER, AND

BRIEF IN SUPPORT THEREOF

R obebt L. Cabteb,

T hubgood M abshall,

Attorneys for Complainants

and Intervenors.

Due Date: January 15, 1955.

OBAL ABGUMENT IS EEQUESTED

I N D E X

Exceptions on Behalf of Complainants and Inter-

venors ......................................................................... 1

Brief in Support of Exceptions.................................... 3

I.—The Lease Between the Richmond Rail

way Terminal Company and the Union

News Company Sanctions the Use of the

Premises of the Terminal Company for the

Operation of Segregated Restaurant Fa

cilities ............................................................ 4

II.—An Interstate Carrier May Not Avoid Its

Duty to Refrain From Undue Discrimina

tion Against Travelers in Interstate Com

merce Merely by Leasing Portions of Its

Terminal Premises to Private Parties .. 5

III. —Union News Company is a Proper Party

Defendant in these Proceedings and it

was Error to Dismiss the Complaint as to

Them .............................................................. 7

IV. —The Operation of Restaurant Facilities in

the Station or Terminal of an Interstate

Carrier is Subject to Regulation by Con

gress Pursuant to its Plenary Powers

Over Commerce ........................................... 8

V.—Section 3(1) is Broad Enough to Reach

the Discrimination Here in Question . . . . 12

VI.—The Precedents Support Our Contentions

that the Commission Has Authority to

Prohibit the Maintenance of Segregated

Restaurants in Railroad Stations ................. 14

Conclusion .......................................................................... 18

PAGE

11

Table of Cases Cited

American Warehousemen’s Association v. Inland

Waterways Corp., 188 I. C. C. 13 (1931) .............. 11

Baltimore & Ohio R. R. Co. v. United States, 305

U. S. 507 (1939) ........................................................ 11

California v. United States, 320 U. S. 577 (1944) . . . 8

Chesapeake & Ohio Ry. v. United States, 11 F. Supp.

588 (S. D. D. Va. 1935), aff’d 296 U. S. 1 8 7 .......... 13

Crosby v. St. Louis, San Francisco Ry. et al., 112

I. C. C. 239 (1926) .................................................. 16

Dayton Union Ry. Co. Tariff for Redcap Service,

256 I. C. C. 289 (1943) ............................................. 2,17

Dining Car Employees Union v. Atchison, Topeka &

Saute Fe Ry., 263 I. C. C. 789 (1945) ................... 18

Hastings Commercial Club, et al. v. Chicago Mil

waukee & St. Paul Ry. Co., et al., 69 I. C. C. 489

(1922) .......................................................................... 15

Houston East & West Texas Ry. Co. v. United States,

234 U. S. 342 (1914) .................................................. 13

Howitt, et al. v. United States, 328 U. S. 189 (1946) . 13

Interstate Commerce Commission v. Chicago Rock

Island & Pacific Ry. Co., 218 U. S. 88 (1910) . . . . 13

Kirschbaum v. Walling, 316 U. S. 517 (1942) .......... 9

Louisville & Nashville R. R. Co. v. United States,

282 U. S. 740 (1931) ................................................. 18

McCall v. California, 136 U. S. 104 (1890) .............. 12fn

Merchants Warehouse Co. v. United States, 283

U. S. 501 (1931) ......................................................... 13

Missouri, Kansas & Texas Ry., et al., Valuation

Docket No. 828, 34 Valuation Reports (I. C. C.)

293 ................................................................................ 15

Mitchell v. United States, 313 U. S. 80 (1941) . . . . 13

PAGE

Ill

Montgomery v. Chicago, B. & Q. R. R. Co., 228 F.

616 (CA 8th 1915)...................................................... 14

Mornford v. Andrews, 151 F. 2d 511 (CA 5th 1945) . 8, 9

New York v. United States, 331 U. S. 284 (1947)___ 13

Simpson v. Shepard, 230 U. S. 352 (1913) .............. 10

Southern Pacific Terminal Co. v. Interstate Com

merce Commission, 219 U. S. 498 (1911)..............8,10,11

Southern Ry. Co. v. Hussey, 42 F. 2d 70 (CA 8th

1930), aff’d 283 U. S. 1 3 6 ......................................... 5, 6

Southwestern Produce Distributors v. Wabash R.

Co., 20 I. C. C. 458 (1911) ....................................... 16,17

Swift & Co. v. United States, 196 U. S. 375 (1905) .. 12fn

Tobin v. Hudson Transit Lines, Inc., 95 F. Supp. 530

(D. N. J. 1951) .......................................................... 8,9

United States v. Baltimore & Ohio R. R., 333 U. S.

169 (1948) ............................................................... 5,6,8,13

United States v. Pennsylvania R.R. Co., 105 F. Supp.

615 (E. D. Pa. 1952) ................................................. 9

Walling v. Atlantic Greyhound Corp., et al., 61 F.

Supp. 992 (E. D. S. C. 1945) ................................. 8, 9

Walling v. Palmer, 67 F. Supp. 12 (M. D. Pa. 1946) .. 8

Other Authorities Cited

2 Sharfman, The Interstate Commerce Commission

(1931)

PAGE

15

BEFORE THE

JttfrrBtate (Emmtu'm (Eommiasimt

N ational A ssociation for the A d

vancement of Colored People,

et al.,

Complainants,

v.

St. L ouis-S an F rancisco R y . Co.,

et al.,

Defendants.

Docket No. 31423

EXCEPTIONS ON BEHALF OF COMPLAINANTS AND

INTERVENORS TO THE REPORT PROPOSED BY

HOWARD HOSMER, EXAMINER, AND

BRIEF IN SUPPORT THEREOF

Come now the complainants, the National Association

for the Advancement of Colored People, Ruby Hurley,

Hattie Ballard, Wendell Ferguson, Clarence Morgan,

Charlie Mae Hayes, A. S. Crishon, Gelene Payte, Russell

L. Anderson, Jr., Ethel I. Berry, Elvira Craig, George

Johnson, Eugene Gordon, Elliott J. Beal, Dorothy M.

Scott Green, Janies Green, James G. Baptiste, and Warren

Stetzel and intervenors, A. L. James, John L. LeFlore and

T. E. McKinney, Jr., in the above-entitled proceedings and

in the following particulars take issue with and except to

the findings and conclusions in the report proposed by

Howard Hosmer, Examiner.

I .

The complainants and intervenors except to the state

ment in the proposed report (Sheet 17, paragraph 2, line

10 et seq.) which states:

2

‘ 1 The lease is silent as to racial segregation.

Terminal has certain powers of supervision for a

purpose which may be described as policing. The

lessee is obligated to comply with the requirements

of the Department of Public Health, City of Rich

mond, and with all other lawful governmental rules

and regulations. The context, however, indicates

that this requirement is for the purpose of keeping

the premises in a neat, clean, and orderly condition,

and does not render the lessee vicariously liable for

violations of the Interstate Commerce Act.”

II.

Complainants and intervenors except to the statement

in the proposed report (Sheets 17, 18, paragraph 3, line

21 et seq.) which states:

‘ ‘ Even if the lunch rooms were directly operated

by Terminal, however, it would be at least doubtful

whether the operation could be regulated by the

Commission, which on several occasions has ex

pressed the view that, while station lunch-rooms and

restaurants may serve the convenience of the general

public, they are not on the same footing as waiting

rooms in respect of the common-carrier responsi

bilities of railroads. Southwestern Produce Dis

tributors v. Wabash R. Co., 20 I. C. C. 458; Dayton

Union Ry. Co. Tariff for Redcap Service, 256 I. C. C.

289, 299. It is concluded, therefore, that the opera

tions of the lunch rooms in the Broad Street Station

may not be regulated under the Interstate Com

merce Act.”

I I I .

Complainants and intervenors submit that it was error

for the Commission to dismiss the complaint against the

Union News Company.

3

BRIEF IN SUPPORT OF EXCEPTIONS

Statement

Complainants instituted the instant proceedings to test

the legality of defendants’ practices in maintaining racially

segregated facilities for Negro interstate passengers in

railroad coaches, passenger waiting rooms and in station

restaurants. Complainants contended that such practices

constituted undue and unreasonable prejudice within the

purview of Section 3(1) of the Interstate Commerce Act.

Mr. Hosmer, Examiner, has found that the practices com

plained of with respect to railroad coaches and passenger

waiting rooms constitute unlawful discrimination pro

scribed under the Interstate Commerce Act and has recom

mended that an order prohibiting such practices in the

future be entered. With this phase of the report com

plainants are in full accord.

Mr. Hosmer also concluded that the segregation of

Negro and white passengers with respect to the use and

enjoyment of railroad station restaurant facilities is not

subject to the jurisdiction of the Commission under the

Interstate Commerce Act. With this phase of the report

we take exception.

The authorities conclusively demonstrate, we submit,

that jurisdiction has been conferred upon the Commission

to prohibit discrimination in the use and enjoyment of

restaurant facilities operated within railway terminals.

The Commission has unquestioned power to issue cease

and desist orders binding both the carrier and lessee opera

tor to operate the restaurant facility without discrimina

tion as to race or color and in conformity with the require

ments of the Interstate Commerce Act.

We further submit that the Union News Company is

a proper party defendant to these proceedings, and it was

error for the Commission to have ordered the complaint

dismissed as to them.

4

I .

The lease between the Richmond Railway Terminal

Company and the Union News Company sanctions the

use of the premises of the Terminal Company for the

operation of segregated restaurant facilities.

The Richmond Railway Terminal Company, pursuant

to a lease which is filed as Exhibit 2 as a part of this rec

ord, grants to the Union News Company the exclusive

right to operate eating facilities within the Broad Street

Station. The lease itself makes manifest the fact that the

Richmond Terminal Railway Company is aware of and

condones the use of its premises by the Union News Com

pany for the operation of racially segregated restaurant

facilities, and, we submit, to conclude that the lease is

silent as to racial segregation is to misread its provisions.

In paragraph one of the current lease, the terminal

space in question is described in the following terms:

“ Luncheonette and soda fountain room; kitchen

previously used as Oyster bar; storeroom adjacent

to kitchen which was part of the original kitchen;

colored lunchroom and kitchen.’ ’

Paragraph seven of the lease refers to “ the marble counter

in the colored lunch room” as being the property of the

Richmond Terminal Railway Company. Certainly these

references make clear that, at the very least, the Richmond

Terminal Railway Company was aware of the fact that

the Union News Company was maintaining within the

Broad Street Station segregated eating facilities—a lunch

room for colored persons and one for white persons. While

the lease does appear to envisage independent operation

by Union News, paragraph nine of the lease empowers the

Richmond Terminal to require that employees of Union

News comply with reasonable requirements with respect

5

to the propriety of their conduct. Pursuant to this pro

vision it seems clear that Richmond Terminal meant to

protect itself and its premises against impropriety on the

part of Union News and its employees. Certainly it does

not stretch the imagination or the law to construe this

provision as vesting in the Richmond Terminal power to

insist that the Union News Company in its operations

within the Broad Street Station comply with the law. That

this provision authorized the Richmond Terminal to require

Union News to serve all persons without restrictions based

upon race or color pursuant to the Interstate Commerce

Act seems evident beyond question.

We submit that the lease sanctions the practices which

are the subject of complaint and that the carrier had ulti

mate authority under the lease to prohibit the discrimina

tion here involved.

I I .

An interstate carrier may not avoid its duty to

refrain from undue discrimination against travelers in

interstate commerce merely by leasing portions of its

terminal premises to private parties.

In our judgment the Examiner has properly found that

carriers may not segregate passengers in railway stations

without violating their duties under the Interstate Com

merce Act. Once it is established that a carrier owes a

statutory duty to travelers in interstate commerce, the

carrier may not avoid this obligation simply by leasing

parts of its premises to other parties. It is a well-estab

lished principle, both under the Interstate Commerce Act

and at common law, that a common carrier may not avoid

its obligations to interstate shippers or to the traveling

public by a mere leasing device. United States v. Baltimore

& Ohio R. R. Co., 333 U. S. 169 (1948); Southern Ry. Co. v.

Hussey, 42 F 2d 70 (C A. 8th 1930),aff’d 283 U. S. 136.

6

In United States v. Baltimore <& Ohio R. R., supra,

Justice Black speaking for the Court asserted, at page

175, that “ It would be strange had this legislation left a

way open whereby carriers could engage in discriminations

merely by entering into contracts for the use of trackage.

In fact, this Court has long recognized that the purpose of

Congress to prevent certain types of discriminations and

prejudicial practices could not be frustrated by contracts

even though the contracts were executed long before enact

ment of the legislation.”

In Southern Ry. Co. v. Hussey, supra, it was held that

where a lessor carrier owes a clear legal duty toward a

person, the duty may not be avoided by any arrangement

which a carrier may make with any other person. If

any part of the duty is delegated to another, the Court

stated, the latter becomes an agent of the carrier and in

that respect the carrier is held responsible for the agents’

acts.

Thus, in the instant case the defendant carrier, owing

a clear duty to travelers in interstate commerce not to

discriminate against them on terminal premises owned

by the carrier, may not avoid this duty by a lease to third

parties which practices racial discrimination with respect

to use and enjoyment of the leased premises.

It is somewhat unrealistic to conclude that the carrier

is somehow an innocent bystander as between the lessee

operator and the Negro passenger complaining of dis

crimination. For it is the carrier itself which determines

the practices on its premises. Here the signs and segre

gated waiting rooms in the Broad Street Station (although

segregation is not rigidly enforced) were the practices

which led to and condoned the Union News Company in its

operation of segregated eating facilities within the Broad

Street Station. No problem such as the discriminatory

practices here complained of would have arisen, if the Bich-

7

mond Terminal Railway Company had operated its termi

nal in the manner required by the Interstate Commerce Act.

We submit that here the carrier is primarily responsible

for the fact that Union News Company discriminates

against Negro passengers with respect to the use and

enjoyment of restaurant facilities within the Broad Street

Station. As such it should be required to cease discrimi

nating against Negro passengers within the terminal and

should be held required to prohibit such practices on part

of persons operating a public facility on its premises.

I I I .

Union News Company is a proper party defendant

in these proceedings and it was error to dismiss the

complaint as to them.

The Commission erred in dismissing this complaint

against the Union News Company. It is a proper party

defendant and is subject to the Commission’s jurisdic

tion with respect to violations of the Interstate Commerce

Act complained of in these proceedings.

Section 42 of the Interstate Commerce Act provides

that “ In any proceeding for the enforcement of the provi

sions of the statutes relating to interstate commerce, . . .

it shall be lawful to include as parties, in addition to the

carrier, all persons interested in or affected by the rate,

regulation, or practice under consideration, and inquiries,

investigations, orders and decrees may be made with refer

ence to and against such additional parties in the same

manner, to the same extent, and subject to the same provi

sions as are or shall be authorized by law with respect to

carriers.”

8

Thus, in United States v. Baltimore & Ohio R. R., supra,

the Supreme Court found that a stockyard company which

had entered into an agreement with a carrier which re

sulted in a discrimination against persons and commodi

ties, was properly made a party to a proceeding against

the carrier and that a cease and desist order against it

was justified by the terms of Section 42. Justice Black

stated at page 172, note 2 that:

“ We . . . find no merit to the contention that we

should by interpretation restrict that section’s [§ 42]

broad language. . . . ”

Similarly, in the instant case, the Union News Company

as a party interested and affected by the practice under

consideration, falls within the purview of Section 42 and is

a proper party defendant in these proceedings.

IV.

The operation of restaurant facilities in the station

or terminal of an interstate carrier is subject to regula

tion by Congress pursuant to its plenary powers over

commerce.

The federal courts in upholding various types of regu

lation have held that terminal facilities owned by interstate

carriers are within the reach of Congress under its com

merce powers. California v. United States, 320 U. S. 577

(1944); Southern Pacific Terminal Co. v. Interstate Com

merce Commission, 219 U. S. 498 (1911); Mornford v.

Andrews, 151 F. 2d 511 (C. A. 5th 1945); Tobin v. Hudson

Transit Lines, Inc., 95 F. Supp. 530 (D. N. J. 1951); Wall

ing v. Atlantic Greyhound Corp. et al., 61 F. Supp. 992

(E. D. S. C. 1945); Walling v. Palmer, 67 F. Supp. 12 (M .D.

Pa. 1946).

9

The courts have held that janitors, porters and other

employees performing services in terminals of interstate

carriers are within the reach of the wage and hour pro

visions of the Fair Labor Standards Act. Mornford v.

Andrews, supra; Tobin v. Hudson Transit Lines, Inc.,

supra; Walling v. Atlantic Greyhound Corp., supra.

In these cases, the courts have reasoned that the opera

tion of a terminal is a necessary part of the business of an

interstate carrier and is a part of interstate commerce.

Thus, janitorial employees are held to be “ in commerce”

and under the jurisdiction of the Fair Labor Standards

Act. Mornford v. Andrews, supra; Walling v. Atlantic

Greyhound Corp., supra.

It may be noted also that the operation of the Fail-

Labor Standards Act has been extended even to main

tenance workers employed by the owner of a loft building

in which space was rented by persons producing goods

principally for interstate commerce. Kirsclihaum v. Wall-

ing, 316 U. S. 517 (1942). In the Kirschbaum case, the court

specifically noted that this application of the law was proper

even though Congress, in enacting the Fair Labor Stand

ards Act, did not legislate to the full extent of its power to

regulate commerce, as it had done in enacting the discrim

ination provisions of the Interstate Commerce Act.

Thus, it would seem difficult to rebut a contention that

Congress may prohibit an interstate carrier from using its

property in such a manner as to accomplish or allow dis

crimination against travelers in interstate commerce.

There is also no question but that if these restaurant

facilities were operated directly by the Richmond Terminal

Railway Company that in such operation the carrier must

conform to the provisions of the Interstate Commerce Act.

See United States v. Pennsylvania Railroad Co., 105 F.

Supp. 615, 619 (E. D. Pa. 1952).

10

In Southern Pacific Terminal Co. v. Interstate Com

merce Commission, supra, the Supreme Court held that it

was within the power of Congress under the Commerce

Clause and within the jurisdiction of the Interstate Com

merce Commission under Section 3(1) of the Interstate

Commerce Act to prohibit the use of terminal property by

a carrier in such a manner as to give an undue preference

to a shipper by affording him facilities not afforded to other

shippers for the storage and manufacture of products

destined for shipment in interstate commerce. In the

Court’s view, the fact that the goods in question were

stored on terminal property and destined for interstate

commerce was sufficient to bring this case within the regu

latory power of Congress and the jurisdiction of the Inter

state Commerce Commission.

In the instant case the major reason for the mainte

nance of a restaurant in Broad St. Station is for the con

venience of the travelling public using the station. Thus,

the fact that the defendant carrier uses its terminal prop

erty in such a manner as to cause a discrimination against

persons destined for travel in interstate commerce is suf

ficient to bring this case within the control of Congress and

the jurisdiction of the Interstate Commerce Commission.

Nor may the cases be distinguished by a claim that res

taurant facilities operated on a carrier’s terminal property

serve some persons who do not travel in interstate com

merce. It is well established that the power of Congress

to regulate interstate commerce is not limited by the fact

that intrastate transactions may have become so inter

woven therewith that the effective government of the for

mer is incidental to control of the latter. Simpson v. Shep

ard, 230 U. S. 352 (1913).

11

Certainly whether the services from which the dis

crimination arises are a necessity is of no relevance in

determining whether Congress has the power or the Inter

state Commerce Commission the jurisdiction to prohibit

a particular form of discrimination. Indeed the dis

crimination held within the power of Congress and the

Interstate Commerce Commission to prohibit in the

Southern Pacific Terminal Co., supra, was not one arising

from the operation of services which the carrier was

required to provide. Storage and warehousing services

are not functions which a carrier is required to perform

either at common law or under the Interstate Commerce

Act, Yet the Supreme Court held in the Southern Pacific

Terminal Co. that Congress has the power to prohibit

discrimination in affording such services on a carrier’s

terminal property when the carrier elects to render them.

American Warehousemen’s Association v. Inland Water

ways Corp., 188 I. C. C. 13 (1931). This principle was

reiterated in Baltimore & Ohio R. R. Co. v. United States,

305 U. S. 507 (1939). There the Supreme Court held that

Section 3(1) was violated by defendant carriers’ furnishing

to shippers warehousing services, including storage, handl

ing and insurance, for less than the cost to defendants

where such services at similar rates were not open to all

shippers alike. The Court upheld the Interstate Commerce

Commission’s order even though in another part of the

opinion it noted that these practices by carriers were not

transportation services.

Thus, even if it be conceded that terminal restaurants

are not necessary carrier services, it is clear that Congress

has the power to prohibit discrimination arising against

12

travelers in interstate commerce from the operation of

euch services when provided.1

V .

Section 3(1) is broad enough to reach the dis

crimination here in question.

Section 3(1) of the Interstate Commerce Act provides

that: “ It shall be unlawful for any common carrier . . . to

make, give or cause any undue or unreasonable preference

or advantage to any particular person . . . in any respect

whatsoever or to subject any particular person . . . to

any undue or unreasonable prejudice or disadvantage in

any respect whatsoever.”

It will be noted that this section is not in any way

qualified or limited in its terms and has been construed

1 If there exists a test based upon the nature of the service pro

vided rather than upon the persons whom it serves, it is perhaps the

one propounded by the Supreme Court in McCall v. California, 136

U. S. 104 (1890). In that case the court struck down as a burden

on interstate commerce a municipal license tax imposed upon an

agent of a railroad company whose duties were to solicit passenger

traffic and who sold no tickets but merely took customers to railroad

companies which would sell them. There the court rejected the

suggestion that the essentiality of the business to the commerce of

the road was the test of whether the business was a part of inter

state commerce. Rather, the court said, “ The test is, was the busi

ness a part of the commerce of the road? Did it assist or was it

carried on with the purpose to assist, in increasing the amount of

passenger traffic on the road?”

There is little question that a restaurant business operated on

terminal property would be subject to regulation as commerce under

this test. Moreover, it should be noted that the criterion used in the

McCall case was for the purpose of determining whether a state regu

lation was a burden on interstate commerce, a test more stringent

than that used to determine whether Congress has the right to enact

legislation under its power to regulate interstate commerce. Swift &

Co. v. United States, 196 U. S. 375, 399 (1905).

13

by the courts as a sweeping prohibition against all forms

of discrimination which Congress had the power to pro

scribe. Thus, in Houston East & West Texas Ry. Co. v.

Lnited States, 234 U. S. 342 (1914), Justice Hughes, speak

ing for the Court at page 356, said of Section 3(1) that

“ this language is certainly sweeping enough to embrace

all of the discriminations of the sort described, which it

was within the power of Congress to condemn. . . . It is

apparent from the legislative history of the act that the

evil of discrimination was the principal thing aimed at

and there is no basis for the contention that Congress

intended to exempt any discriminatory action or practice

of interstate carriers affecting interstate commerce which

it had authority to reach.”

This principle, that Section 3(1) is comprehensive

enough to prohibit any discrimination which Congress had

the powei to reach under the Commerce Clause, along with

the principle that the Act itself was primarily aimed at

erasing discrimination in all of its various manifestations

and at establishing uniformity of treatment for all users

of interstate transportation facilities, has been reaffirmed

many times by federal courts. Interstate Commerce Com

mission v. Chicago Rock Island & Pacific Ry. Co., 218

U. S. 88 (1910); Merchants Warehouse Co. v. United

States, 283 U. S. 501 (1931); Mitchell v. United States,

313 U. S. 80 (1941); Howitt, et al. v. United States, 328

U. S. 189 (1946); New York v. United States, 331 U. S.

284 (1947); United States v. Raltimore & Ohio R. R. Co.,

supra; Chesapeake & Ohio Ry. v. United States, 11 F.

Supp. 588 (S. W. W. Va. 1935), aff’d 296 U. S. 187.

It is clear, we submit, that Congress possesses power

under the Commerce Clause to prohibit discrimination

against interstate travelers in the furnishings of eating

facilities upon the terminal property of an interstate

14

carrier. Moreover, the language of Section 3(1) is suffi

ciently inclusive to leave no doubt that Congress intended

to accomplish this purpose with the enactment of the

Interstate Commerce Act.

V I .

The precedents support our contentions that the

Commission has authority to prohibit the maintenance

of segregated restaurants in railroad stations.

It is clear from the decisions that the federal courts

have considered the regulation of restaurants and other

facilities maintained on terminal property as within the

primary jurisdiction of the Interstate Commerce Commis

sion and thus, necessarily within the power of Congress

to regulate under the commerce clause.

In Montgomery v. Chicago B. <£ Q. R. R. Co., 228 F.

616 (C. A. 8th 1915) plaintiff brought an action claiming

that defendant railroad operated its station restaurant,

which was open to the public, passengers and railroad

employees in a manner which resulted in an undue preju

dice against the plaintiff. Taking note of a rule of the

Interstate Commerce Commission that carriers subject to

the act might provide eating houses for passengers and

employees, subject to certain regulations, and that prop

erty for the use of eating houses might be regarded as

necessary and intended for the use of carriers in the con

duct of their business, the court held that the complaint

was within the primary jurisdiction of the Interstate Com

merce Commission.

The court stated that the “ case presented is one which

calls for primary reference to the Commission, to determine

whether the establishment of a railway eating house . . .

15

was a legitimate exercise of administrative discretion on

the part of the carrier and whether the reasonable rule

established by the Commission has been fairly observed in

the present instance.”

In making valuations of property called for by Section

19 of the Interstate Commerce Act the Interstate Com

merce Commission is required to divide property owned

by a carrier into that owned or used for the purpose of a

common carrier and that held for other purposes. See

Section 19(b). It may be noted that under this section the

Commission has held a building in a railroad terminal,

which is leased to private parties for restaurant purposes

and used primarily by the carrier’s passengers and em

ployees, to be a necessary common carrier facility. Mis

souri, Kansas <& Texas Ry. et al., Valuation Docket No. 828,

34 Valuation Reports (I. C. C.) 293, 328.

The Commission, however, would not be required to

hold that restaurant facilities are necessary common car

rier facilities in order to hold that they are within the

jurisdiction of the Interstate Commerce Act, for as noted

supra, Congress has prohibited all common carrier activi

ties resulting in unreasonable prejudice which it has the

authority to regulate. Moreover, the Act in defining a rail

road as a common carrier subject to its provisions states

that a railroad “ shall include . . . terminal facilities of

every kind used or necessary in the transportation of

persons or property designated herein.” (emphasis added.)

Section 1(3). This phrase has been interpreted so as to

include, inter alia, “ station grounds” , Hastings Commer

cial Club, et al. v. Chicago Milwaukee & St. Paul Ry. Co.,

et al., 69 I. C. C. 489, 494 (1922) and has been construed

as vesting in the Commission jurisdiction of railroads and

all of their physical facilities. 2 Sharfman, T he I nter

state Commerce Commission, p. 5, 1931.

16

In addition, in specific instances the Interstate Com

merce Commission has indicated that it would exercise

jurisdiction over restaurant and similar facilities in rail

road terminals where discrimination resulted from their

operation. Southwestern Produce Distributors v. Wabash

R. R. Co., 20 I. C. C. 458 (1911), Crosby v. St. Louis, Scm

Francisco Ry. et al., 112 I. C. C. 239 (1926).

Southwestern Produce Distributors v. Wabash R. R. Co.,

supra, cited by the Examiner at sheet 17 of his proposed

report as precedent for holding that the Interstate Com

merce Commission has no jurisdiction over the operation

of station lunchrooms, is in fact authority for quite the

opposite proposition. In that case the Commission held

that the defendant railroad, which had given the use of its

terminal premises to a company for the purpose of con

ducting a fruit auction, did not unjustly discriminate

against plaintiff by refusing to accord it equal facilities

for conducting such operations. But the basis for the hold

ing was that while a common carrier must serve the travel

ing and shipping public on equal terms, the carrier owed

no duty to a plaintiff who fell into neither class.

The Commission emphasized that its holding was predi

cated on the fact that the evidence disclosed no discrimina

tion against shippers or members of the traveling public.

After equating the auction with restaurants and other

facilities conducted on terminal property, the Commission

held that it was without authority to act “ unless in some

way, such use of a terminal property [for an auction] cre

ates preferences or discriminations as between shippers or

travelers.” [emphasis added]. If this were the fact, the

Commission declaimed, the case “ might stand in quite a

different light.”

In Crosby v. St. Louis San Francisco Ry. et al., supra,

the Commission again indicated that where ample proof of

17

discrimination was produced, it would prohibit such dis

crimination in restaurant facilities on a carrier’s terminal

premises. In that case defendant filed motions to dis

miss the specifications in plaintiffs’ complaint on the ground

that the allegations even if true did not constitute violations

of the Act. Defendant’s motions were sustained except as

to certain allegations, among which was plaintiff’s com

plaint that Negro passengers were discriminated against

in restaurant facilities furnished at defendant’s depot.

Although the Commission later held for defendant on the

ground that plaintiff had not produced sufficient evidence

to warrant the finding of undue prejudice, it specifically

assumed jurisdiction of plaintiff’s claim that the opera

tion of a restaurant in defendant’s terminal resulted in

undue discrimination.

Thus, the Interstate Commerce Commission has indi

cated that where undue prejudice in the operation of ter

minal restaurant facilities is proved (as it has been in the

instant case), the Commission will exei'cise its jurisdiction

to prohibit such discrimination.

Dayton Union Ry. Co., 256 I. C. C. 289 (1943) is not

authority to the contrary. There the Commission held

merely that Section 6 of the Interstate Commerce Act

required defendant carrier to file a tariff stating the

charge made by it for the service of carrying baggage

by its porters in railway stations. The Commission, in

passing, distinguished redcap service from other con

veniences including lunch counter services which a rail

road might provide. In making this distinction, the Com

mission employed language quite similar to that used in

Southwestern Produce Distributors v. Wabash R. R. Co.,

supra, and nowhere even implied that the Interstate Com

merce Commission was without authority or jurisdiction to

halt discrimination against Negroes traveling in interstate

18

commerce, arising out of the operation of restaurant facili

ties on an interstate carrier’s terminal property.

Nor does Dining Car Employees Union v. Atchison,

Topeka £ Sante Fe Ry., 263 I. C. C. 789 (1945) aid defend

ant’s cause. There the Interstate Commerce Commission

held that it was not unlawful discrimination for railroads

to issue free transportation to some of its employees while

refusing to issue them to plaintiffs. This holding was in

harmony with the ruling of the Supreme Court in Louisville

& Nashville R.R. Co. v. United States, 282 U. S. 740 (1931)

that the distribution of free passes is an exceptional case

not within the purview of Section 3(1) because special

provision is made for it in other sections of the Interstate

Commerce Act (specifically Sections 1 and 22). Thus,

holdings in pass cases have no application to other cases

brought under Section 3(1) of the Interstate Commerce

Act and do not support the contention that the Com

mission lacks jurisdiction to prohibit the type of dis

crimination complained of here. Both court decisions and

holdings of the Commission itself leave no doubt that the

Commission has power to require the restaurant facilities

operated upon terminal property be open to all members

of the travelling public without distinction as to race or

color.

Conclusion

W herefore, for the reasons hereinabove stated, it is

respectfully submitted that those portions of the report

proposed by the Examiner, Howard Hosmer, which would

hold that restaurant facilities in railway stations are not

subject to the Interstate Commerce Act be rejected and

an order issued granting complainants, intervenors and

19

all the Negro travelling public relief against being sub

jected to racial discrimination in the use and enjoyment

of restaurant facilities operated within railroad stations.

In all other particulars we respectfully submit that the

proposed report should be adopted.

Robert L. Carter,

T hurgood M arshall,

Attorneys for Complainants

and Intervenors.

Due Date: January 15, 1955.

Certificate of Service

I hereby certify that I have this day served the fore

going document upon all parties of record in this proceeding

by mailing a copy thereof properly addressed to counsel

for each party of record.

Dated at New York, N. Y., this 14th day of January,

1955.

R obert L. Carter.

Supreme Printing Co., Inc., 114 W orth Street, N. Y. 13, BEekman 3-2320