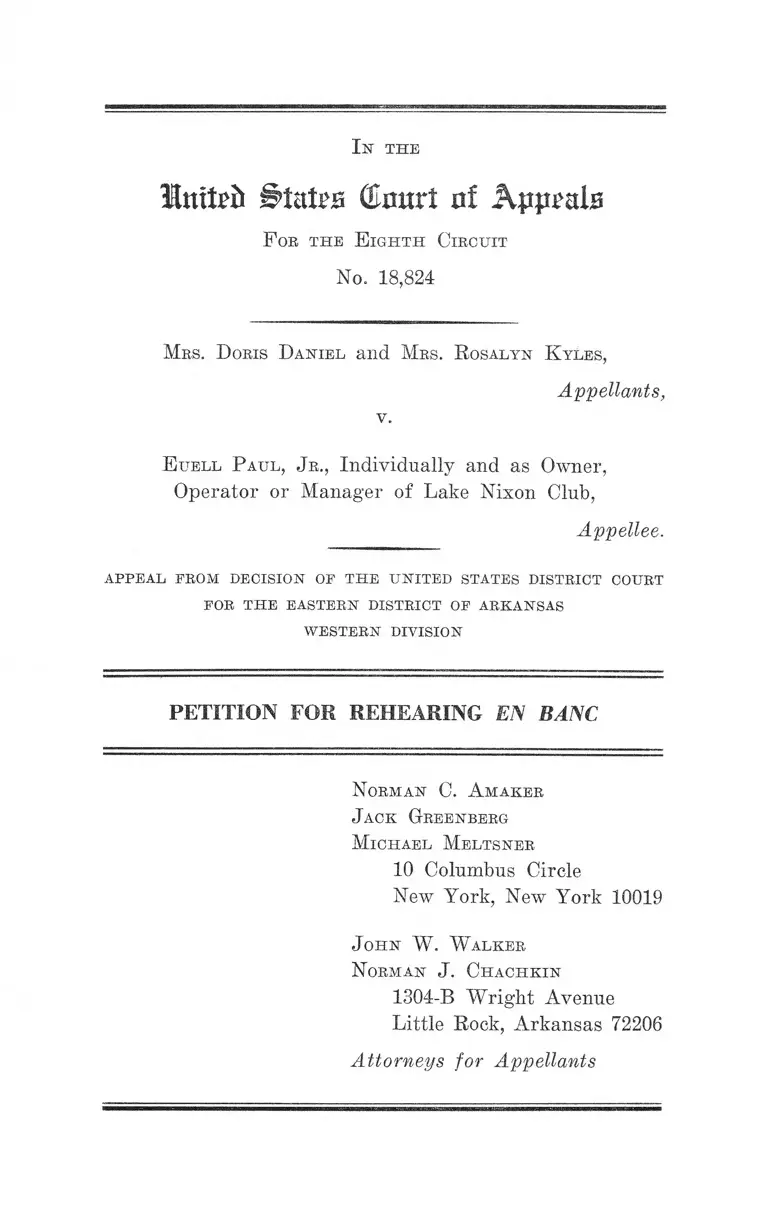

Daniel v. Paul Petition for Rehearing En Banc

Public Court Documents

May 31, 1968

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Daniel v. Paul Petition for Rehearing En Banc, 1968. 35c1f8f1-ae9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/6d3ebd7d-ec59-43c8-b1f5-10a3b666d63c/daniel-v-paul-petition-for-rehearing-en-banc. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

Hntteii BXhU b (Eourt nt Appeals

F ob the E ighth Circuit

No. 18,824

In the

Mbs. Doris Daniel and Mbs. Rosalyn K yles,

Appellants,

v.

E uell Paul, Jb., Individually and as Owner,

Operator or Manager of Lake Nixon Club,

Appellee.

A P PE A L FBOM DECISION OF T H E U N IT E D STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR T H E EA STE R N DISTRICT OF AR K A N SAS

W ESTE R N DIVISION

PETITION FOR REHEARING EN BANC

Norman C. A m a k e r.

Jack Greenberg

M ichael Meltsner

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

John W . W alker

Norman J. Chaciikin

13Q4-B Wright Avenue

Little Rock, Arkansas 72206

Attorneys for Appellants

In the

B u Ub CExmrt nf Kppmlz

F ob the E ighth Circuit

No. 18,824

Mbs. Dobis Daniel and Mbs. Rosalyn K yles,

v.

Appellants,

E uell Paul, Jb., Individually and as Owner,

Operator or Manager of Lake Nixon Club,

Appellee.

A PPE A L EBOM DECISION OF T H E U N IT E D STATES D ISTRICT COURT

FOB T H E EASTERN D ISTRICT OF AR K A N SAS

W E STE R N DIVISION

PETITION FOR REHEARING EIS BANC

Appellants respectfully urge that this appeal, decided

adversely to them on May 3, 1968, by a 2-1 decision of a

panel of this court (Judges Mehaffy, Van Oosterhout,

Judge Heaney dissenting), be set down for rehearing

en banc because of (1) the importance of the issues in

volved herein and their crucial relationship to effective

enforcement of Title II of the Civil Rights Act of 1964:

(2) the conflict between the majority opinion and the

Fifth Circuit’s en banc decision in Miller v. Amusement

Enterprises, Inc. interpreting Sections 201(b)(3) and

(c)(3 ) of the Act; (3) the conflict between the majority

opinion here and the Fifth Circuit’s opinion in Fazzio

Real Estate Co., Inc. v. Adams interpreting Section 201

2

(b )(4 ) of the Act; (4) the disagreement within the panel

itself on these important issues. The panel’s majority

interpretation of these sections of the Act, if permitted

to stand, will so seriously interfere with enforcement of

Title II of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 that it should be

reexamined by the entire membership of this court en banc.

I

There can be little doubt concerning the importance of

the case. It is this court’s first major interpretation of

Title II of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, probably the most

important legislation passed by the Congress in a quarter

of a century or more and the most sweeping and far-

reaching piece of civil rights legislation enacted since the

Reconstruction Era. The policy expressed in Title II of

the Act is one “ that Congress considered of the highest

priority.” Newman v. Piggie Park Enterprises, 390 U.S.

400, 402, 19 L.ed. 2d 1263, 1265 (1968).

The majority’s interpretation of the sections of the

Act here involved differs so markedly from that expres

sion of Congressional policy as to require a thoroughgoing

reexamination by the full court. An additional highly

important reason necessitating en banc consideration by

this court is because the decision of the majority is now

in conflict with the full Fifth Circuit Court as to the

interpretation of §§ 201(b) (3) and (c)(3 ) of the Act and

with a panel of that court as to § 201(b) (4). Obviously,

the full bench of this court should consider whether these

conflicts shall be permitted to stand.

II

A. Appellants have consistently maintained throughout

this litigation that Lake Nixon is subject to the prohibition

against racial discrimination contained in the Civil Rights

3

Act of 1964 because it is a “ place of entertainment” as

that term is used in § 201(b) (3) of Title II (42 U.S.C.

§ 2000a(b) (3 )). The district judge rejected this conten

tion based upon a distinction between “ entertainment”

(spectator) and “ recreation” (participant) which he felt

was written into the Act. Kyles v. Paul, 263 F. Supp. 412,

419-20 (E.D. Ark. 1967). The same issue was involved

in the recent decision in Miller v. Amusement Enterprises,

------ F.2d ------ (5th Cir. No. 24259, April 8, 1968) (en

banc). The Fifth Circuit rejected the distinction:

We are unable to agree with those concepts which

would prefer, or those which would demand, that the

Civil Rights Act be narrowly construed, i.e., the es

tablishments referred to in § 201(b) (3) must be places

of entertainment which present exhibitions for spec

tators and that such exhibitions must move in inter

state commerce. However, while not necessary to our

decision, as will be seen by a further reading of this

opinion, we find that Fun Fair is covered by the lit

eral terms of the Act. Although it may be that the

types of exhibition establishments listed in § 201(b) (3)

are those which most commonly come to mind, no

one would dispute the proposition that such list is

not complete or exhaustive. Therefore, any establish

ment which presents a performance for the amuse

ment or interest of a viewing public would be included.

In our view Fun Fair is such an establishment. The

amusement park presents a performance of small chil

dren riding on various mechanical “kiddie” rides plus

a performance of ice skating. It is obvious to us that

many of the people who assemble at the park come

there to be entertained by watching others, particu

larly their own children, participate in the activities

available. In fact Mrs. Miller’s presence at the park

4

was to see her children perform on ice.9 While the

record does not explicitly and clearly show this to

he a fact, aside from Mrs. Miller’s statement, we as

Judges may take judicial knowledge of the common

ordinary fact that human beings are “people watchers”

and derive much enjoyment from this pastime.10

9 In Mrs. Miller’s deposition she stated:

“Yes, my little boy particularly was interested in show

ing off—showing me how well he could skate, too.”

10 The following is from the record:

“ How many people would you say were present?

“ Well, I can’t say exactly. There were people skating;

there were people sitting in the seats; there were people

standing waiting to be served.”

(Slip opinion pp. 10-11) (Footnotes in court’s opinion)

Thus, the Fifth Circuit has held that the participative-

exhibitive dichotomy adopted by the district court below

and accepted by the panel is not a viable distinction in

light of the Act’s purpose. Surely the swimming, boating,

picnicking, sun-bathing and dancing activities occurring at

Lake Nixon are as much, if not more, spectator activities

as those which occur at Fun Fair Park. In any event, the

Fifth Circuit’s conclusion was reached after extensive

examination by the full court. This court should do no

less.

B. The panel’s majority sustained the district court’s

interpretation of the “ entertainment” provisions of Title II

on another ground—that no effect upon interstate com

merce had been shown.

Appellants are unable to accept the statement of the

majority that there was a “ total lack of any evidence that

the operations of Lake Nixon in any fashion affect com

merce” (Slip opinion, p. 17). We particularly call to the

attention of the court the fact that Lake Nixon placed

5

an advertisement in the magazine, “Little Rock Today.”

This magazine was described by the district court as “a

monthly magazine indicating available attractions in the

Little Rock area,” Kyles v. Paul, 263 F.Supp. 412, 418

(E. D. Ark. 1967). This magazine fulfills the same func

tion in Little Rock that the “ Key” magazine fulfills in

St. Louis, and we note the following statement from the

masthead of the May, 1968 edition:

Published monthly and distributed free of charge by

Metropolitan Little Rock’s leading hotels, chambers

of commerce, motels and restaurants to their guests,

new comers and tourists, and to reception rooms.

It should be obvious that any facility which places an

advertisement in a magazine summarizing available at

tractions including entertainment opportunities and which

magazine is distributed in hotels, willingly accepts, and

indeed expects, the patronage of interstate travelers.1

Certainly this Court may take judicial notice of the char

acter of this magazine if it may take judicial notice of

the “common knowledge” that a type of boat is manu

factured in Arkansas (Slip opinion, p. 14), leading to an

inference in the court’s opinion that Lake Nixon’s boat

ing equipment was entirely intrastate, an inference clearly

contradicted by the record (R. 14).2 * * Furthermore, the

Fifth Circuit concluded that the operations of the Fun

Fair Amusement Park did affect commerce even though

there was no proof whatsoever that the food sold at the

1 The Club also advertised in Little Bock Air Force Base pub

lished at an Air Force base near Little Rock and over an area

radio station (R. 11). Clearly, the facilities of Lake Nixon—in

cluding the concession stand—were “ offered” to interstate travelers.

2 Whether or not some boats of this type are manufactured in

Arkansas, the boats involved in this ease were imported from

Oklahoma (Slip opinion, p. 25).

6

concession stand originated outside Louisiana. In this

case, the district court specifically found that ingredients

of the hamburger buns and soft drinks originated outside

Arkansas (263 F. Supp. at 418). The district court also

discounted the influence of juke box records shipped in

from outside the state,8 but this reasoning was specifically

condemned in the Miller case (see slip opinion at p. 17),

and see Twitty v. Vogue Theatre Cory., 242 F.Supp. 281

(M.D. Fla. 1965). Again, the rationale of the Miller case,

if accepted by this Court, is clearly controlling and de

mands a reversal. (See especially, slip opinion, pp. 17-21.)

That rationale should either be accepted or rejected by

the entire Eighth Circuit where matters so important are

concerned.

Ill

A. The consequences for the Civil Rights Act of 1964

will be equally grave if the concept of a “unitized opera

tion,” a locution which permits public accommodations to

circumvent section 201(b)(4) of Title II is permitted to

stand. This theory was first proposed by the district

judge, without any authority therefor, and was approved

in the majority opinion of the panel. Judge Heaney’s

dissenting opinion exposes the irrational logic of the con

cept more clearly and eloquently than we are able, but we

should like to emphasize the practical consequences of

permitting this erroneous interpretation of the law to bear

the stamp of this circuit. Thousands upon thousands of

individual and corporate proprietors throughout the coun

try who wish to discriminate against Negroes, or any

8 “ There is no dispute that the juke boxes were manufactured

outside of Arkansas, and the same thing may be said about at

least many of the records played on the machines” 263 F. Supp. at

417.

7

other racial or religious group, and whom Congress wished

to prohibit from engaging in such discrimination, will now

be free to segregate their establishments by applying the

circular reasoning of this ease. First, it is said that Lake

Nison is not within section 201(b) (2) because it is not prin

cipally engaged in selling food. This statement is true

enough—the major purpose of Lake Nixon’s existence is

not to sell food. However, the proprietor then argues

that there is no coverage under section 201(b)(4) because

the food stand cannot be considered by itself to determine

whether its principal intent is selling food (and thus

whether it is a covered establishment within the prem

ises of Lake Nixon and therefore whether Lake Nixon it

self is covered). All this because the food stand is said

to be merely an “adjunct” to the principal business of

Lake Nixon. In effect, the food stand disappears from

the view of the district court and the panel’s majority

in attempting to determine whether Lake Nixon is within

the purview of the Civil Eights Act. And this despite

the fact, which can hardly be contested, that the princi

pal business of the food stand is selling food.

There was no basis for the district court’s belief that

Section 201(b)(4) contemplated an establishment under

different ownership within the parent establishment. Even

if that were so, the record here shows that while Lake

Nixon was owned by Mr. and Mrs. Paul, the snack bar

was jointly owned by them and Mrs. Paul’s sister (R.32).

Thus, Lake Nixon meets even the judges’ erroneous

standard for coverage under Section 201(b)(4).

B. Beyond this, as a consequence of the Fifth Circuit’s

recent decision in Fassio Real Estate Co., Inc. v. Adams

(No. 24825, May 24, 1968) affirming Adams v. Fassio Real

Estate Co., 268 F. Supp. 630 (E.D. La. 1967), there now

exists a clear-cut conflict between the decision of this

8

panel and that of the unanimous panel in Fazzio Real

Estate [Judges Coleman and Clayton (who dissented from

the en banc decision of the court in Miller) ; district judge

Johnson], The Fifth Circuit has affirmed a district court

decision which rejected the “ unitized operation” (263 F.

Supp. 419) with sales “purely incidental to the recrea

tional facilities” (263 F. Supp. 417) approach of the dis

trict court below and endorsed by the panel’s majority

here. As the court said:

“ . . . [I ] f it he found—as it was in this case—

that a covered establishment exists within the struc

ture of a unified business operation, then under the

provisions of Section 201(b)(4) of the Act the entire

business operation located at those premises becomes

a ‘covered establishment.’ The Act draws no distinc

tion with regard to the principal purposes for which

a business enterprise is carried on. Had a substan

tial business purpose test been intended, as urged by

Fazzio, it would have been a very simple matter to

include it in the Act. No such test was included with

respect to the question of when the presence of one

covered ‘establishment’ in a business enterprise will

result in the entire operation’s being treated as one

establishment for the purpose of coverage under Sec

tion 201(b) (4). In fact, the face of the Act specifically

rebuts the existence of any substantial business pur

pose or ‘functional unity’ limitation on the meaning

of the term ‘establishment’ as used throughout Sec

tion 201. Under Section 201(b)(4)(a) coverage may

extend to both establishments within covered estab

lishments and to an establishment ‘within the prem

ises of which is physically located any such covered

establishment.’ ” (Slip opinion pp. 6-7)

# * # # #

9

“ Fazzio’s Bridge Bowl as an entity is not covered be

cause it is principally engaged in selling food for

consumption on the premises under Section 201(b) (2).

Rather, Fazzio’s is covered (1) because the refresh

ment counter is a covered establishment principally

engaged in selling food for consumption on the prem

ises within the meaning of Section 201(b)(2), and (2)

because the covered refreshment counter is physically

located within the premises of Fazzio’s bowling oper

ation [Section 201(b) (4) (a) ( ii) ] and the two stand

ready to and do serve each others patrons. [Section

201 (b )(4 )(b )].” (Slip opinion pp. 7-8)

Obviously, the conflict of interpretation on this point

should also be reviewed by the full court.

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, appellants urge that this

petition for rehearing en banc be granted.

Respectfully submitted,

Norman C. A makeb

Jack Greenberg

Michael Meltsneb

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

John W . W alker

Norman J. Chachkin

1304-B Wright Avenue

Little Rock, Arkansas 72206

Attorneys for Appellants

10

Certificate

I hereby certify that the above petition is submitted in

good faith and is not filed for delay. It is believed to he

meritorious.

Norman C. A maker

Certificate of Service

This is to certify that on this 31st day of May, 1968,

I served a copy of Appellants’ Petition for Rehearing

En Banc upon Sam Robinson, Esq., Adkins Building, 115

East Capitol Street, Little Rock, Arkansas, by mailing a

copy thereof to him at the above address via United States

airmail, postage prepaid.

Norman C. A maker

Attorney for Appellants

ME1LEN PRESS INC. — N. Y. C.«^H&*>219