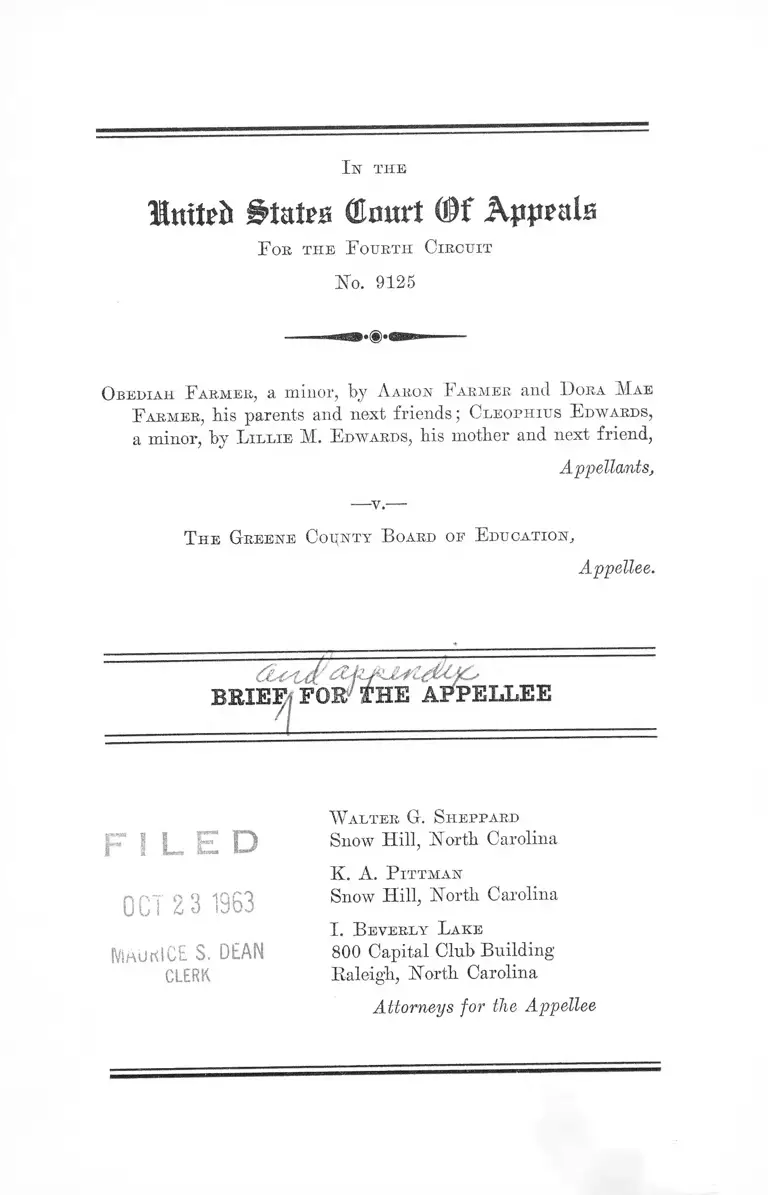

Farmer v. Greene County Board of Education Brief for the Appellee and Appendix

Public Court Documents

October 23, 1963

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Farmer v. Greene County Board of Education Brief for the Appellee and Appendix, 1963. 223d016c-b19a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/6d616cf3-d8eb-4f53-8856-6d4871834826/farmer-v-greene-county-board-of-education-brief-for-the-appellee-and-appendix. Accessed February 19, 2026.

Copied!

In t h e

Initefc States CEourt (§f Appeals

F oe t h e F ourth C ir cu it

Ho. 9125

O bediah F ar m er , a m inor, by A aron Farm er and D ora M ae

F ar m er , his parents and next friends ; C leophitts E dwards,

a m inor, by L il l ie M . E dwards, his m other and next friend,

Appellants,

T h e Greene C ounty B oard of E ducation ,

Appellee.

BRIEF FOR' f HE APPELLEE

F ! L E D

OCT 2 3 1963

(VImukICE S. DEAN

CLERK

W a l te r G. Sh eppard

Snow Hill, Forth Carolina

K. A. P it t m a n

Snow Hill, Forth Carolina

I . B everly L ak e

800 Capital Club Building

Raleigh, Forth Carolina

Attorneys for the Appellee

1

I N D E X

P A G E

S ta te m e n t of th e Case ...................................

Q uestions I n v o l v e d ........................................... .................. 3

S ta te m e n t of t h e F acts ............................... ...................... 3

A bgum ent :

I. The District Court Did Not Err In Denying

The Plaintiffs’ Motion For A Preliminary

Injunction...................................................................... 8

(a) The Plaintiffs Cannot Maintain This

Action As A Class Action ................................ 8

(b) Plaintiffs Are Not Entitled To The

Order They Seek Concerning School

Teachers And Other School Personnel .......... 9

(c) The Plaintiffs Have Failed To Pursue

Their Plain And Adequate Administra

tive Remedy ........................................................ 10

(d) This Is Not A Proper Case For Issuance

Of A Preliminary Injunction ......................... 15

(e) The Plaintiffs Are Not Entitled To The

Relief Sought In Their Alternative Prayer .... 18

( f ) The Plaintiffs Have Shown No Reason

For A Transfer To Any Other School .......... 18

II. The District Court Did Not Err In Striking

From The Complaint Paragraphs 9 And 1 0 ........... 19

(a) Paragraph 9 Of The Complaint Was

Properly Stricken ............................................. 19

(b) Paragraph 10 Of The Complaint Was

Properly Stricken ............................................. 20

III. The District Court Did Not E rr In Refusing

To Admit Evidence Offered By The Plaintiffs....... 22

(a) The Depositions Of Gerald I). James

And H. Maynard Hicks .................................. 22

(b) The Record Of The 1959 Hearing Be

fore The Board ................................................. 25

C onclusion .......................................................................................... 26

A p p e n d ix ............................................................................................... 27

TABLE OF CITATIONS

Cases:

P A G E

Allen v. County School Board of Prince Edward County,

249 F. 2d 462, cert, den., 355 IT. S. 953 (4th Circuit,

1957) .................................................................................... 17

Benson Hotel Corp. v. Woods, 168 F. 2d 694 (8th Circuit,

1948) .................................................................................... 15

Best Foods v. General Mills, 3 F. R. I). 459 (I). C. Del.,

1944) .................................................................................... 19

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483 (1954) ........ 17, 19

Burke v. Mesta Machine Co., 5 F. R. D. 134 (I). C. Pa.,

1946) .................................................................................... 19

Carson v. Board of Education of McDowell County, 227

F. 2d 789 (4th Circuit, 1955) .................................... 9, 10, 11

Carson v. Warlick, 238 F. 2d 728, cert, den., 353 U. S.

910 (4th Circuit, 1956) ............................................. 10,11,15

Cement Enamel Development, Inc. v. Cement Enamel of

New York, Inc., 186 F. Supp. 803 (D. C. 1ST. Y.,

1960) .................................................................................... 15, 16

Covington v. Edwards, 264 F. 2d 780 (4tli Circuit, 1959).. 10, 11

De Vargas v. Brownell, 251 F. 2d 869 ( 5th Circuit, 1958).. 24

Doeskin Products, Inc. v. United Paper Company, 195 F.

2d 356 (7th Circuit, 1952) ............................................... 15, 16

Gamlen Chemical Co. v. Gamlen, 79 F. Supp. 622 (D. C.

Pa., 1948) ........................................................................... 15

Hershel California Fruit Products Co. v. Hunt Foods,

Inc., I l l F. Supp. 732 (D. C. Cal., 1953) .................... 15

Heuer v. Loop, 198 F. Supp. 546 (D. C. Ind., 1961) .......... 19

Holt v. Raleigh City Board of Education, 164 F. Supp.

853, affd, 261 F. 2d 527 (E. D. N. C., 1958) ............ 10

Jeffers v. Whitley, 309 F. 2d 621 (4tli Circuit,

1962) ...................................................................... 14,15, 17,19

McKissick v. Durham City Board of Education, 176 F.

Supp. 3, (M. D. N. C., 1959) 10

P A G E

McNeese v. Board of Education, 305 F. 2d 783 (7th Cir

cuit, 1962) ........................................................................... 10

Parham v. Dove, 271 F. 2d 132 (8th Circuit, 1959) ........ 10

Pocket Books, Inc. v. Walsh, 204- F. Supp. 297 (D. C.

Conn., 1962) ........................................... 15

Salem Engineering Co. v. National Supply Co., 75 F.

Supp. 933 (IX C. Pa., 1948) .......................................... 19

Schenley Distillers Corp. v. Kenken, 34 F. Supp. 578

(D. C. S. C., 1940) ............................................................ 19

School Board of the City of Newport News v. Atkins,

246 F. 2d 325 (4th Circuit, 1957) .................................. 17

Seagram Distillers Corp. v. NewT Cut Bate Liquors, 221

F. 2d 815, cert, den., 350 U. S. 828 (7th Circuit,

1955) ................................................................................. 15

Shuttlesworth v. Birmingham Board of Education, 162 F.

Supp. 372 (N. D. Ala., 1958) ........................................ 10

Steinberg v. American Bantam Car Co., 76 F. Supp. 426

(IX C. Pa. 1948) .................. .......... .................................. 15

Thompson v. County School Board of Arlington County,

144 F. Supp. 239, afPd, 240 F. 2d 59, cert, den., 77

S. Ct. 667 (E. D. Va., 1956) .......................................... 17

Westinghouse Electric Corp. v. Free Sewing Machine Co.,

256 F. 2d 806 { 7th Circuit, 1958 ) .................................. 15, 16

Wheeler v. Durham City Board of Education, 309 F. 2d

630 (4th Circuit, 1962) ................................................... 14

Statutes:

North Carolina General Statutes, Chapter 115, .

Section 72 ......................................................................... 7, 9, 30

North Carolina Pupil Assignment A c t .................................. 6, 27

North Carolina General Statutes, Chapter 115,

Section 115-176 .................................................................. 27

North Carolina General Statutes, Chapter 115,

Section 115-177 .................................................................. 27

IV

P A G E

[North Carolina General Statutes, Chapter 115,

Section 115-178 ................................................................... 10, 28

[North Carolina General Statutes, Chapter 115,

Section 115-179 ................................................................... 28

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure:

Rule 8 (a) ................................................................................ 19

Rule 8 (e) ................................................................................ 19

Rule 12 ( f ) ............................................................................. 19

Rule 26 (d) (2) .................................................................... 24

Rule 26 (d ) (4 ) .................................................................... 23

I n t h e

Imteb States Court (§f Appeals

F oe t h e F ourth C ir cu it

No. 9125

O bediah F ar m e r , a minor, by A aron F arm er , and D ora M ae

F ar m e r , his parents and next friends; Clboph iu s E dw ards,

a minor, by L iu lie M. E dw ards, his mother and next friend,

Appellants,

— v.—

T h e G reen e Co u n ty B oard of E ducation

Appellee.

B E I E F F O E T H E A P P E L L E E

STATEM EN T OF TH E CASE

This is an appeal by the plaintiffs from interlocutory orders

of the District Court for the Eastern District of North Carolina,

denying their motion for preliminary injunction and granting the

motion of the defendant to strike paragraphs 9 and 10 of the

complaint.

The minor plaintiffs are two Negro high school students. For

many years they have been and are now enrolled in the public

schools of Greene County, North Carolina. Pursuant to the North

Carolina Act for the Assignment and Enrollment of Pupils each

.of them has .been assigned, year by year, by the defendant to a

public school in the county. Neither of the minor plaintiffs, nor

anyone acting on behalf of either of them, has ever filed with the

defendant any objection to their respective assignments or any

application or request for assignment to a different school.

2

In their complaint the plaintiffs do not ask for assignment- to

any specified school. They seek a decree, general in nature, en

joining the Board of Education “ from operating a bi-racial

school system in Greene County” , and “ from assigning teachers,

principals and other professional school personnel . . . on the

basis of the race and color of the children attending the school to

which the personnel is to be assigned” .

In the alternative they seek a decree directing the Board to

present “ a complete plan” for the reorganization of the entire

school system of the county and the assignment of teachers, prin

cipals, and other professional school personnel on a nonracial basis.

Following the institution of the suit the plaintiffs, filed their

motion for a preliminary injunction granting the relief prayed for

in the complaint. The defendant moved to strike certain portions

of the complaint.

The answer of the defendant wTas not filed until after the ruling

of the District Court upon these motions. It has now been filed

and no hearing in or trial of the action has been had other than

the hearing on the said motions.

The motions came on for hearing before Hon. John D. Larkins,

District Judge, one hearing being had in Washington, ETorth

Carolina, and another in Trenton, Forth Carolina. The plaintiffs

introduced oral testimony of four witnesses. The defendants in

troduced affidavits of the Chairman of the Board of Education and

the Superintendent of Schools. The rules adopted by the defendant

for assignment of children to the public schools of Greene County,

ETorth Carolina, for the year 1962-63 are attached to the Chair

man’s affidavit.

The District Court entered its order (Appendix to plaintiffs’

brief, page 224a), finding the facts and denying the motion for

preliminary injunction, and another order granting the motion

of the defendants to strike paragraphs 9 and 10 of the complaint

but denying the motion of the defendants to strike other para

graphs of the complaint. The District Court retained jurisdiction

of the action for determination of such other issues of fact and

law as may arise. From these orders the plaintiffs appeal.

3

QUESTION'S IN VOLVED

1. Did the District Court err in denying the plaintiffs’ motion

for preliminary injunction?

2. Did the District Court err in striking from the complaint

paragraphs 9 and 10 ?

3. Did the District Court err in sustaining the defendant’s ob

jection to the plaintiffs’ offering in evidence depositions taken

but not introduced in evidence in another action and transcripts

of administrative hearings upon other applications in 1959 ?

STATEM EN T OF TH E FACTS

At the hearing counsel for the plaintiffs stated: “ We are not..

litigating whether the,named plaintiffs are to be transferred to

affy'pStTcuIar schools” . Counsel for the defendants inquired:

"May I inquire if counsel for the plaintiffs know to what school

these named plaintiffs want to transfer?” Counsel for the plain

tiffs replied: “ Counsel for plaintiffs does not know.” (Appendix

to plaintiffs’ brief, pages 89a-90a.)

There are approximately 3,000 Negro children and 2,000 white

children enrolled in the public schools of Greene County. No

application has ever been made to the defendant Board by or on

behalf of any Negro child now enrolled in any public school of

Greene County for assignment or reassignment to a public school

attended by white children, and no application has ever been

made to the Board by or on behalf of any white child for assign

ment or reassignment to any school attended by Negro children.

(Appendix to plaintiffs’ brief, pages 60a, 79a, 80a, 159a, 175a,

184a, 197a, 198a.)

Obediah Farmer, 16 years of age, has been enrolled in the

Greene County schools since 1953 without objection or complaint

to the Board. He has enrolled in and attended in each year since

that time the school to which he has been assigned by the Board—

first the North Greene Elementary School, and then the Greene

County Training School in which he is now enrolled. At no time

has he, or any person acting on his behalf, filed with the Board

4

any objection to bis assignment or any request for reassignment.

(Appendix to plaintiffs’ brief, pages 33a, 34a, 44a, 56a, 58a,

146a, 160a.)

Cleophius Edwards, 16 years of age, has been enrolled in the

public schools of Greene County each year since 1952— first in

the North Greene Elementary School and then in the Greene

County Training School, in which he is now enrolled. At no time

has he, or any other person acting on his behalf, objected to his

assignment to the school to which he has been assigned or his

enrollment for instruction therein. At no time has he, or any other

person acting on his behalf, made any application to the Board for

assignment or reassignment to a different school. (Appendix to

plaintiffs’ brief, pages 32a, 69a, 77a, 146a, 160a. 1

In 1955 the State of North Carolina adopted an Act, herein

after called The Pupil Assignment Act, governing the assignment

and enrollment of pupils in the public schools, which is set forth

in the Appendix to this brief. In June of each year since the

adoption of that statute the defendant Board has assigned to a

public school of the county every child eligible to attend such

schools. No known deviation from that statute has ever occurred

in the assignment of any child. (Appendix to plaintiffs’ brief, pages

132a, 138a, 193a.). No assignment of any child is for a period

longer than the end of the then coming school year. (Appendix to

plaintiffs’ brief, pages 25a, 131a, 160a, 193a.)

Each year the rules governing assignment and reassignment of

pupils for the then coming year are published in a newspaper of

general circulation in the county and each child already enrolled

in the public schools of the county is given a report card on which

his assignment for the next year is shown. (Appendix to plaintiffs’

brief, pages 31a, 157a, 158a, 160a, 168a, 193a.) The rules and

regulations governing the assignments and reassignments of chil

dren for the year 1962-63, which are substantially the same as the

rules for each previous year since the adoption of the above

mentioned statute, were so published in June, 1962, and each of

the minor plaintiffs was given a report card at the end of the

1961- 62 school year showing his assignment for the following

year. (Appendix to plaintiffs’ brief, pages 31a, 61a, 194a.) The

1962- 63 rules are attached to the affidavit of H. Maynard Hicks.

(Appendix to plaintiffs’ brief, pages 31a, 254a-258a.)

5

For children proposing to enter the first grade the Board con

ducts pre-school registration in the spring preceding the year in

which the child is to enter school. The public is informed of the

time and the place of the holding of these registrations for each

school by a notice published in a newspaper of general circulation

in the county, stating, as to each school in the county, the name of

the school, and the date and hour of the pre-school registration

at that school with no reference to race. (Appendix to plaintiffs’

brief, pages 119a, 120a, 122a, 166a.) The children and their

parents have presented themselves for this pre-school registration

and the children have been assigned to the school to which they

presented themselves. (Appendix to plaintiffs’ brief, pages 119a,

120a, 122a.) There is no difference in method for the Negro and

the white children with reference to this pre-school registration.

The published notice does not direct anyone where to take his

child for pre-school registration. (Appendix to plaintiffs’ brief,

pages 120a, 166a.) There has never been a situation in which a

Negro school child has presented himself, or has been presented,

for pre-school registration at a school attended by white children

nor has there ever been a situation in which a white child has

presented himself, or been presented, for pre-school registration

at a school attended by Negro children. (Appendix to plaintiffs’

brief, pages 125a, 166a.)

Children transferring to the Greene County public schools from

another school system present themselves to a public school, for

enrollment therein, without any instruction or direction from the

defendant as to the school to which they are to so present them

selves. (Appendix to plaintiffs’ brief, pages 138a, 139a.) The

Superintendent of the Greene County schools makes an interim

assignment in such instance until the Board meets and then the

Board makes a permanent assignment. The superintendent has

never assigned a child in such instance to a school other than the

one to which the child presented himself, or was presented, for

enrollment. (Appendix to plaintiffs’ brief, page 174a.) No Negro

child has ever sought such an interim enrollment in any school

attended by white children in Greene County and no* white child

has ever sought such an interim enrollment in a school attended by

Negro children in Greene County. (Appendix to plaintiffs’ brief

175a.) The superintendent’s authority over assignments is limited

to such interim assignments. (Appendix to plaintiffs’ brief, page

6

198a.) No Negro child coming into the Greene County public

school system from another public school system has ever applied

to the Board for reassignment to a different school from that to

which he has been assigned. (Appendix to plaintiffs’ brief, page

198a.)

In all the history of the Greene County public school system

there has been only one instance in which Negro children have

applied for assignment to a school attended by white children.

(Appendix to plaintiffs’ brief, pages 61a, 78a 80a, 184a, 189a,

193a, 199a.) This was in 1959. Five high school boys, then en

rolled in the Greene County Training School, applied to the

Board for reassignment to the Walstonburg High School. (Ap

pendix to plaintiffs’ brief, pages 58a, 78a, 80a, 147a, 180a, 200a.)

These applicants came from only three families. One of these

families no longer resides in Greene County. The present plain

tiffs are the other two. (Appendix to plaintiffs’ brief, pages 61a,

181a.) Prior to their applications the Board had already deter

mined to close the Walstonburg High School. (Appendix to plain

tiffs’ brief, pages 183a, 200a.) Their applications were denied and

they were given full opportunity, in accordance with the statute

of the State of North Carolina, and in accordance with the rules

of the defendant Board governing assignments and reassignments

for the year 1959-60, to present themselves to the Board and give

evidence at a hearing in support of their applications. (Appendix

to plaintiffs’ brief, pages 81a, 180a, 199a, 200a.)

Each of those applications was considered by the Board on the

basis of the criteria set forth under its rules and regulations and,

upon the denial of the application, formal written reasons for the

denials were given to the parents. These applications were denied

because in the judgment of the Board, and in the light of all the

evidence, the granting of them would not be in the best interests

of the child involved. (Appendix to plaintiffs’ brief, page 183a.)

The evidence in the opinion, of the Board.was_such as would have

justified the Board in denying the applications had the applicants

been white children.' (Appendix to plaintiff's5 brief, page 184a.)

Eaet-appli'Cafibn"m that instance was considered and heard sep

arately and determined on the basis of the evidence with reference

to it. (Appendix to plaintiffs’ brief, pages 180a, 199a.) The

Walstonburg High School, to which those applicants applied for ad

7

mission is no longer in existence. (Appendix to plaintiffs’ brief,

pages 58a, 78a, 183a.)

Those five applicants returned to the Greene County Training

School and attended it for the year 1959-60 and in subsequent

years until they graduated or dropped out of school. Their assign

ments for the year 1959-60 terminated at the end of that school

year. They never applied for assignment to a different school in

any subsequent year. (Appendix to plaintiffs’ brief, pages 80a,

81a, 189a, 199a.) They brought an action in the District Court

seeking an order for their reassignment, but they did not prosecute

the action and, after all the applicants involved had either grad

uated, moved out of the County or dropped out of school, the

action was dismissed without any hearing of the merits or even

the filing of an answer by the defendant Board. (Appendix to

plaintiffs’ brief, pages 48a, 199a.) Ho appeal was taken from that

decision of the District Court. (Appendix to plaintiffs’ brief,

page 199a.)

Although the plaintiffs in their complaint seek an order direct

ing the defendant to assign teachers, principals and other school

personnel to schools without regard to the race of the children

attending the schools, the record establishes that none of the plain

tiffs is or ever has been a teacher, principal or other school em

ployee. (Appendix to plaintiffs’ brief, pages 28a, 36a, 59a.)

There are 170 public school teachers employed in the schools of

Greene County, of whom 95 are bTegroes. (Appendix to plaintiffs’

brief, page 139a.) Ho teacher, principal or other school employee

of the Negro race, or of the white race, has ever applied to the

defendant for assignment to a school attended by a race different

from that of the teacher. (Appendix to plaintiffs’ brief, pages

27a, 35a, 159a.) Under the laws of the State of north Carolina

(G.S. 115-72, set forth as an appendix to this brief) the defendant

has no authority to elect teachers, principals, or other school per

sonnel. (Appendix to plaintiffs’ brief, pages 34a, 141a, 142a, 143a,

162a, 177a, 197a, 198a, 202a.) These school employees are under

contract which designates the school where they are to work.

(Appendix to plaintiffs’ brief, page 162a.) The defendant has no

authority to transfer them to a different school. (Appendix to

plaintiffs’ brief, pages 35a, 143a, 162a, 177a, 197a, 198a, 202a.)

8

A E G U I E N T

I

T h e D istr ic t C ourt D id N ot E rr I n D e n yin g th e P l a in t if f s ’

M o tion for A P r e l im in a r y I n ju n c t io n .

The plaintiffs, by their motion, asked the District Court, with

out waiting for the defendants to file an answer and without wait

ing for a trial on the merits, to take from the hands of the

defendant Board of Education its authority over the assignment

of pupils to the public schools of Greene County and to require the

defendant Board to assume authority, which it does not have, with

reference to the employment of teachers, principals and other school

personnel. This the District Court refused to do. The evidence

at the hearings on the motion supports the findings of fact by

the District Court and those findings support its denial of the

motion.

(a) The Plaintiffs Cannot Maintain This Action As A Class

Action.

The plaintiffs purport to bring this action on behalf of a class

to which they belong. Their own evidence establishes that there is

no class situated similarly to the plaintiffs or for the benefit of

which the plaintiffs are entitled to sue. The evidence establishes

that no other child, Negro or white, and no other parent of any

child, now enrolled in or eligible to be enrolled in the public

schools of Greene County, has ever shown any interest whatsoever

in attending, or in having his or her child attend, a school in which

children of a different race are enrolled. (Appendix to plaintiffs’

brief, pages 28a, 57a, 60a, 61a, 77a, 78a, 80a, 159a, 166a, 175a,

184a, 189a, 197a.)

The pre-school registrations for first grade children are held

pursuant to published notices stating simply the dates at which

such registrations are to be held at the respective schools without

any indication of the school to which Negro children or white

children are to present themselves. (Appendix to plaintiffs’ brief,

page 119a.) No Negro child has even been presented for pre-school

registration at a school attended by white children. (Appendix to

plaintiffs’ brief, page 116.)

9

The plaintiffs’ own evidence shows that these plaintiffs stand

alone. Of all the other three "thousand Fegro children enrolled in

the public schools of Greene County, and all of the parents of

those children, not a single one has indicated to the defendants,

or to the Court, any interest in attending a school attended by

white children, or any intention to authorize these plaintiffs to

bring this action on their behalf, or to do anything in this action

designed to bring about the mixing of their children in schools

with white children.

The evidence of the plaintiffs shows that none of the plaintiffs

is a teacher, principal or other employee in the Greene County

public school system. There is no evidence whatever to show that

they are authorized in this action to represent the interests of any

teacher, principal or other school employee.

The plaintiffs’ own evidence, therefore, shows there are no other

persons similarly situated and similarly interested. The plaintiffs

rights in this action are individual rights and they cannot maintain

this action either as a class action or as a spurious class action.

See, Carson v. Board of Education of McDowell County, 227

F. 2d 789 (4th Cir., 1955).

(b) Plaintiffs Are Not Entitled To The Order They Seek Con

cerning School Teachers And Other School Personnel.

Under the law of the State of Forth Carolina, teachers, princi

pals and other school employees are not elected by the defendant

Board of Education, bnt by the local District School Committee.

(G.S. 115-72, set forth in the Appendix to this brief.) The Board

of Education has a veto power in this matter but cannot compel tbe

election of any school employee by the District Committee. (Ap

pendix to plaintiffs’ brief, pages 177a, 197a.)

When a teacher is elected, he or she signs a contract for the

school year for work at the school named in the contract. The de

fendant Board has no authority to transfer the teacher or other

school employee to work in a different school. Therefore, even if

the order sought by tbe plaintiffs with reference to the teachers and

other school personnel were issued there would be no power in the

defendant to comply with it. The refusal of the District Court to

grant this portion of the relief sought by tbe plaintiffs’ motion for

preliminary injunction was clearly correct.

10

(c) The Plaintiffs Have Failed To Pursue Their Plain And

Adequate Administrative Remedy.

The evidence of the plaintiffs at the hearing on their motion

shows that the defendant Board in the matter of assigning children

to public schools has followed the Worth Carolina Pupil Assign

ment Act, set forth in the Appendix to this brief, and regulations

adopted by the defendant pursuant to that Act. There has been no

deviation from this statute and these regulations. (Appendix to

plaintiffs’ brief, pages 126a, 131a, 132a, 138a.)

The constitutionality of the Worth Carolina Pupil Assignment

Act has been sustained by this Court- and by the Supreme Court.

Carson v. Warlick, 238 F. 2d 728, Cert. Den., 353 IT. S. 910

(4th. Cir., 1956).

Similar statutes adopted in Alabama and Arkansas have also

been held constitutional. Shuttlesivorth v. Birmingham Board of

Education, 162 F. Supp. 372 (W. D. Ala., 1958) ; Parham v.

Dove, 271 F. 2d 132 (8th. Cir., 1959 ).

This Worth Carolina statute (G-.S. 115-178) provides a plain

and adequate administrative remedy for the parent or guardian of

any child dissatisfied with the assignment of such child. I f the

application for reassignment is not approved, notice is required to

be given to the applicant and the applicant is thereupon entitled

to a prompt and fair hearing by the Board, the decision by the

Board after such hearing to be given to the applicant by registered

mail.

This Court and the District Courts of this circuit have re

peatedly held that the administrative remedy so afforded is an

adequate remedy and must be exhausted before resort can be had

to the courts of the United States to compel the reassignment of a

pupil in the public schools. Carson v. Warliclc, 238 F. 2d 724,

Cert. Den., 353 U. S. 910 (4th. Cir., 1956); Carson v. Board of

Education of McDowell County, 227 F. 2d 789 (4th. Cir.,

1955); Covington v. Edwards, 264 F. 2d 780 (4th. Cir., 1959) ;

Holt v. Raleigh City Board of Education, 164 F. Supp. 853,

AfPd 261 F. 2d 527 (E. D. W. C., 1958); McKissick v. Dur

ham City Board of Education, 176 F. Supp. 3 (M. D. W. C.,

1959). See also: McNeese v. Board of Education, 305 F. 2d

783 (7th. Circuit, 1962).

11

Iii Carson v. Board of Education of McDowell County, supra,

this Court said:

“ It is well settled that the Courts of the United States will

not grant injunctive relief until administrative remedies have

been exhausted. . . . This rule is especially applicable to a

case such as this, where injunction is asked against state or

county officers with respect to the control of schools maintained

and supported by the State. Federal Courts manifestly can

not operate the schools. . . . Where the state law provides

adequate administrative procedure for the protection of such

rights, the Federal Courts manifestly should not interfere

with the operation of the schools until such administrative

procedure has been exhausted and the intervention of the

Federal Courts is shown to be necessary.”

Again, in Carson v. Warlich, supra, Judge Parker, speaking for

this Court said:

“ Somebody must enroll the pupils in the schools. They can

not enroll themselves; and we can think of no one better

qualified to undertake the task than the officials of the schools

and the school boards having the schools in charge. It is to be

presumed that these will obey the law, observe the standards

prescribed by the Legislature, and avoid the discrimination

on account of race which the Constitution forbids. Hot until

they have been applied to and have failed to give relief

should the courts be asked to interfere in school administra

tion.”

Again, in Covington v. Edwards, supra-, this Court said:

“ The County Board of Education, however, is entitled under

the Forth Carolina statute, to consider each application on its

individual merits and if this is done without unnecessary de

lay and with scrupulous observance of individual constitu

tional rights, there can be no just cause for complaint.”

The evidence of the plaintiffs themselves shows that they have

made no application whatever to the defendant Board prior to the

bringing of this action late in the school year of 1962-63. Obediah

Farmer had then been enrolled in public schools of Greene County

12

for 9 years and Cleophius Edwards had then been, enrolled in

those schools for 10 years. Each year each of them was assigned

to a school. He attended that school without complaint and with

no effort on his behalf by any person to apply to the Board for

reassignment. Even now the plaintiffs say they do not know to what

school they want these students assigned. (Appendix to plaintiffs’

brief, page 90a.) They admit in their complaint (Paragraph 11,

Appendix to plaintiffs’ brief, page 6a) they have made no effort

to comply with the North Carolina Pupil Assignment Act and the

regulations adopted pursuant thereto.

The record shows no course of action by the Board justifying

this ignoring of its authority by the plaintiffs. Their own witnesses

testified that no application has ever been filed with the defendant

Board by or on behalf of any of the 3,000 Negro children now

enrolled in the Greene County public schools for assignment of

any child to a different school for any reason whatsoever. (Appen

dix to plaintiffs’ brief, pages 60a, 19a, 159a, 166a, 197a.)

In Paragraph 4 of their complaint (Appendix to plaintiffs’

brief, page 3a) the plaintiffs allege, “ The defendants are charged

by the laws of the State of North Carolina with the duty of operat

ing a system of free public education in Greene County, North

Carolina, and said Board is presently operating public schools in

said city (sic.) pursuant to said laws.” These are the laws which

this Court and the Supreme Court have said are constitutional.

No deviation from these laws is alleged in the complaint or shown

by the evidence offered at the hearing on the plaintiffs’ motion for

preliminary injunction.

The only effort made by the plaintiffs to justify their complete

ignoring of the plain and adequate administrative remedy afforded

them by the laws of North Carolina and by the regulations of the

defendant Board of Education is their contention that in 1959,

four years before this suit was instituted, the defendant Board

denied the application of five Negro students for reassignment to

the Walstonburg High School. None of those five students is now

enrolled in the public schools of Greene County. Two of them no

longer live in the county. The evidence offered by the plaintiffs

with reference to this shows that before those five students sought

such assignment to the Walstonburg High School the defendant

Board had already decided to close that school. Those applications

13

were all filed at the same time, June 9, 1959. They were acted

upon separately and individually by the defendant Board. They

were rejected by the Board for reasons which the Board believes

were sufficient, and would have led to the same result had the

applicants been white. (Appendix to plaintiffs’ brief, pages 183a,

184a.) The reasons for the rejection of their applications were

given to those applicants by registered mail. The applicants were

given an opportunity to appear before the Board and present evi

dence in support of their applications. This record does not show

why those five applicants sought transfer to the Walstonburg High

School, or what evidence they presented to the Board, or the rea

sons for the Board’s action unless it be that the Walstonburg High

School had already been ordered closed.

After those applications were denied, those applicants instituted

a suit in the District Court to compel their reassignment to the

Walstonburg School. Those five applicants remained in the public

school to which they were assigned for the year 1959-60. In the

following year they returned to that school and never made any

other application for reassignment from it, notwithstanding the

fact that assignments of children to the Greene County public

schools are for one year only and expire with the expiration of the

school year following the date of the assignment.

That action was dismissed by the District Court, without an

answer having been filed by the defendant and without- any hearing

on the motion, after all the applicants there involved had either

graduated from high school, moved from the county or dropped out

of school. (Appendix to plaintiffs’ brief, page 48a.) Ho appeal was

taken from the judgment of the District Court dismissing that

action.

Ho application for reassignment of any Hegro child to any

school other than that to which he or she has been assigned has

ever been received by the defendant Board of Education since

1959, notwithstanding the fact that every year since that time

there have been approximately 3,000 Hegro children enrolled in

the public schools of Greene County. (Appendix to plaintiffs’ brief, .

pages 58a, 78a, 79a, 80a.) Thus, the plaintiffs’ own evidence

clearly shows that the Hegro people of Greene County, like the

white people of Greene County, are content with the school

system as operated by the defendant Board. ^

14

Counsel for the plaintiffs stipulated at the hearing in the Dis

trict Court that there have never been any applications to the

Board from Negro children for assignment to schools, other than

those in which they were enrolled, except the five applications in

1959. (Appendix to plaintiffs’ brief, page 189a.)

Obviously, the plaintiffs have failed completely to show any

justification for their refusal to apply to the Board for the ad

ministrative remedy available to them under the statutes and the

rules of the Board. There is no showing in this, record of any

established practice of denying applications for transfer. There is

no showing of any use of criteria with reference to applications

from Negro children different from those used with reference to

applications from white children. There is no showing of compul

sion of Negro children in the matter of pre-school registration. On

the contrary, the evidence offered by the plaintiffs shows clearly

that the notice of pres-school registration does not designate the

school to which any child is to be presented. (Appendix to plain

tiffs’ brief, page 166a.) Nevertheless, no Negro child has ever

been presented for pre-school registration for the first grade at a

school attended by white children. (Appendix to plaintiffs’ brief,

page 166a.) These circumstances clearly distinguish the present

case from the case of Wheeler et al. v. Durham City Board of

Education, 309 F. 2d 630, decided by this Court October 12,

1962.

The case of Jeffers et al. v. Whitley, 309 F. 2d 621, decided

by this Court October 12, 1962, is also clearly distinguishable

from the present case. There, a large number of the plaintiffs had

applied to the Board and their reassignment had been denied

whereas here the plaintiffs have not attempted to apply to the

Board. Not only did the plaintiffs in the Jeffers case apply before

bringing suit, but they also re-applied for the following school

year. There, the Board gave the applicants no explanation of its

action and “ acknowledged no set of principles governing its deter

mination.” In the present case, the Board has published clear,

specific rules which it follows in all applications for reassignment,

whether the applicant be white or Negro. In the Jeffers case this

Court found “ invariable denial of transfer applications” . Here

there is no such record. In the Jeffers case the Court said, “ the

school board here has turned to the North Carolina Pupil Enroll-

15

meat Act only when dealing with inter-racial transfer requests.”

The evidence in the present case shows clearly that the Board

has followed the Act in all cases and that it has followed its rules,

adopted and published pursuant to that Act, in all applications

regardless of the race of the applicant. In the Jeffers case this

Court said that some of the plaintiffs at least had exhausted their

administrative remedies. Here neither plaintiff has attempted to

do so.

There is no allegation, or any statement by any witness offered

by the plaintiffs at the hearing upon their motion for preliminary

injunction, to justify an assumption by this Court that the de

fendant will not pass promptly and property upon any application

for reassignment pursuant to the procedure prescribed by the

North Carolina Pupil Assignment Act and in accordance with

the standards prescribed by that statute, which procedure and

standards have been held constitutional by this Court and by the

United States Supreme Court in Carson v. Warticle, supra.

(d ) This Is Not A Proper Case For Issuance Of A Preliminary

Injunction.

A preliminary injunction is a provisional remedy designed to

preserve the status quo until the case can be heard on its merits.

The status quo is the last uncontested status which preceded the

pending controversy. Westinghouse Electric Corp. v. Free Seiving

Machine Go., 256 P. 2d 806 (7th Circuit, 1958). See also: Sea-

gram-Distillers Corp. v. Neiv Cut Bate Liquors, 221 P. 2d 815,

Cert. Den., 350 U. S. 828 (7th Circuit, 1955) ; Doeskin Products,

Inc. v. United Paper Co., 195 P. 2d 356 (7th Circuit, 1952);

Benson Hotel Corp. v. Woods, 169 P. 2d 694 (8th Circuit, 1948);

Hershel California Fruit Products Co. v. Hunt Foods, Inc.,

I l l F. Supp. 732 (D. C. Cal., 1953); Gamlen Chemical Co. v.

Gamlen, 79 F. Supp. 622 (D. C. Pa., 1948); Steinberg v. Ameri

can Bantam Car Co., 76 P. Supp. 426 (D. C. Pa., 1948).

The granting of a preliminary injunction in this case would not

preserve the status quo but would completely upset it. A prelimi

nary injunction is a drastic remedy which generally will not be

granted where doubtful issues of fact exist. Pocket Books, Inc. v.

Walsh, 204 P. Supp. 297 (D. C. Conn., 1962) ■ Cement Enamel

16

Development, Inc., v. Cement Enamel of New York, Inc., 186 F.

Supp. 803 (D. C. 1ST. Y., 1960).

The granting or denial of such an injunction is in the discretion

of the District Court, and its decision may not properly he reversed

on appeal except for abuse or discretion. Westinghouse Electric

Corp. v. Free Sewing Machine Co., supra,. Doeskin Products v.

United Paper Co., supra.

(e) The Plaintiffs Are Not Entitled To The Belief Sought In

Their Alternative Prayer.

In their prayer for alternative relief the plaintiffs requested the

District Court to enter a decree directing the Board to present a

plan for the complete reorganization of the school system of

Greene County, including wholesale transfer of teachers, principals

and other school personnel. The evidence which they presented to

the District Court disclosed not one teacher, not one principal, not

one school employee who desires such a reorganization or would

consent to teach or work in a school other than that for which he or

she has a contract. The evidence shows that of the 3,000 JSTegro

children enrolled in the Greene County public school system not

one has ever applied to the defendant Board for such a reorganiza

tion of the school system, or even for the assignment of the in

dividual child to any school other than that in which he or she

is presently enrolled.

This effort by these plaintiffs is a blatant, arrogant attempt to

procure the assistance of the District Court in by-passing the

statutes of the State of North. Carolina and the authority of the

defendant over the administration of the schools of Greene County,

without even affording the defendant an opportunity to file its

answer and be heard and without the slightest effort on the part

of the plaintiffs to apply to the defendant Board for assignment of

the minor plaintiffs to the school of their choice. Even in their

complaint, and again at the hearing (Appendix to plaintiffs’ brief,

page 90a), the plaintiffs through their counsel refuse to state the

school to which they wish the named minor plaintiffs to be as

signed.

Without regard to the wishes of all the other pupils in the

public schools, without regard to the wishes of the principals,

17

teachers and other school employees, these plaintiffs now ask this

Court, without waiting for a hearing upon the issues of fact, sub

sequently raised by the answer of the defendant, to issue a pre

liminary injunction taking from the Board of Education authority

to administer and direct the public school system, to reassign

pupils in all of the schools on a basis which apparently is in opposi

tion to the desires of the pupils and their parents, and to re-shuffle

the teachers, principals and school employees together on a basis

which meets the whims of two Negro children.

Time and time again, this Court has said that the decision of

the United States Supreme Court in Brown v. Board of Education,

347 LT. S. 483, 74 St. Ct. 686, 98 L. Ed. 873 (1954), does not re

quire such an order. In Joffers v. Whitley, supra, this Court said:

' ‘On behalf of others, similarly situated, the appellants are

not entitled to an order requiring the School Board to effect a

general intermixture of the races in the schools” .

In Thompson v. County School Board of Arlington County, 144

F. Supp. 239 (E.D. Va., 1956), Affd, 240 E. 2d 59, Cert. Den.,

77 S. Ct. 667, Judge Bryan said:

“ It must be remembered that the decisions of the Supreme

Court of the United States in Brown v. Board of Education

. . . do not compel the mixing of the different races, in the

public schools. No general reshuffling of the pupils in any

school system has been commanded. . . . Indeed, just so a

child is not through any form of compulsion or pressure re

quired to stay in a certain school or denied transfer to another

school because of his race or color, the school heads may allow

the pupil, whether white or Negro, to go to the same school

as he would have attended in the absence of the ruling of the

Supreme Court.”

That is precisely what the evidence in this case shows the defendant

Board has done.

The foregoing remarks of Judge Bryan were quoted with ap

proval by this Court in School Board of the City of Newport News

v. Atkins, 246 F. 2d 325 (4th. Circuit, 1957). Again, in Allen

v. County School Board of Prince Edward County, 249 F. 2d

462, Cert. Den., 355 U. S. 953 (1957), this Court said:

18

“ This does not mean that the defendants should require mix

ing of white and Negro children in the schools, hut merely

that they should abolish the requirement of discrimination.

I f the children of the different races should voluntarily attend

different schools, this would not be violative of the Constitu

tion or of the Court’s order, so long as there is no requirement

of the school authority to that effect.”

The evidence offered by the plaintiffs shows: Not one of the

3,000 Negro children enrolled in the schools of Greene County

has ever applied to the defendant Board for reassignment; not one

of the Negro children transferring to the schools of Greene County

from another system has ever sought admission to a school attended

by white children; not one of the Negro children presented for

pre-school registration for the first grade has ever been presented

by his or her parents to a school attended by white children; no

white child has ever sought admission to or reassignment to a school

attended by Negro children. This is a record which shows a volun

tary separation of the children in the public schools. The plaintiffs,

and the plaintiffs alone, are dissatisfied, but even the plaintiffs

have not gone to the Board to ask for reassignment. The District

Court was clearly correct in denying their motion for preliminary

injunction.

( f ) The Plaintiffs Have Shown No Reason For A Transfer To

Any Other School.

The evidence shows that the plaintiffs are and have been en

rolled in the Greene County Training School. The evidence also

shows that it is a well equipped, well operated school. (Appendix

to plaintiffs’ brief, pages 26a, 33a.) None of the plaintiffs has

ever complained to the defendant Board of the equipment, cur

riculum, instruction, food or any other aspect of the operation of

this school. (Appendix to plaintiffs’ brief, pages 33a, 44a, 58a.)

The plaintiffs bring this action not because they are dissatisfied

with their school, not because there is any reason to think that they

would be more conveniently situated, more comfortable, or better

educated if they transferred to another school. Their only reason

for seeking a transfer is race.

19

While, as this Court said in Joffers v. Whitley, supra, “ one does

not lose his constitutional rights by complaining of their violation” ,

the Supreme Court has not gone so far as to hold that race alone

is a sufficient ground for transfer of children from a school in

which those children are now receiving adequate education. The

Court in the Brown case held that a child could not be assigned to

a school on the basis of race alone. The plaintiffs seek assignment

on that factor and that factor alone.

I I

T h e D is t r ic t C ourt D id H ot E rr 1st St r ik in g F rom T h e

C o m p la in t P aragraph s 9 an d 10.

Pule 8 (a) of the Federal Pules of Civil Procedure requires

that a complaint must set forth “ a short and plain statement of the

claim showing that the pleader is entitled to relief” . Pule 8 (e)

requires that “ each averment of a pleading shall be simple, precise

and direct.” Pule 12 ( f ) provides that upon motion the Court may

order stricken any immaterial or impertinent matter.

Pursuant to these rules portions of a complaint relating to mat

ters for which the plaintiff could not obtain relief will be stricken.

Heuer v. Loop, 198 F. Supp. 546 (D. C. Ind., 1961).

Any allegation in a pleading which is not germane to the issues

of the case should be stricken on motion of the adverse party.

Best Foods v. General Mills, 3 F. R. D. 459 (D.C. Del., 1944) ;

Burke v. Mesta Machine Co-., 5 F. R. D. 134 (D.C. Pa., 1946) ;

Salem Engineering Co-, v. National Supply Co., 75 F. Supp. 993

(D.C. Pa., 1948); Schenley Distillers Cor-p. v. Benken, 34 F.

Supp. 678 (D.C. S.C., 1940).

(a) Paragraph 9 Of The Complaint Was Properly Stricken.

Paragraph 9 of the complaint which was stricken by the District

Court, contains nothing but allegations about the facts of an en

tirely different lawsuit. That suit was dismissed by the judgment

of the District Court before any answer was filed by the defend

ants therein. (Appendix to plaintiffs’ brief, page 48a.) The Hegro

children on whose behalf that action was instituted are no longer

enrolled in public schools of Greene County. Two of them no longer

20

reside in the county. Two of them have graduated from high school

and the other dropped out of school. (Paragraph 10 of the present

complaint, Appendix to plaintiffs’ brief, page 5 a). That action

has no relation to the present action. Different issues were in

volved. The plaintiffs there sought assignment to a high school

not now in existence. Had the Court not dismissed that action as

moot, the defendants therein would have filed answers asserting a

number of defenses to the merits of that action. The defendants in

that action have never been heard on the merits of that case.

To allow the allegations of Paragraph 9 to remain in this

complaint would require the defendant in this action to plead

the defenses which the defendants in that action would have as

serted had it been necessary to file an answer therein. Thus, the

trial of this action would have been cluttered and obscured by the

trial of the merits of the former action already dismissed as moot.

To allow Paragraph 9 to remain in the complaint would have

been prejudicial to the defendant because the inference of that

allegation is that the defendant acted improperly in denying the

requests for assignment involved in the former case. To have

allowed this allegation to remain in this complaint would have

required the defendant to allege and present evidence in this case

to prove that in the former case it acted properly and in accordance

with its lawful authority. Thus, to have allowed this paragraph

to remain in the complaint would have prolonged the trial of the

present case unnecessarily and would have confused the issues in

this case.

(b) Paragraph 10 Of The Complaint Was Properly Stricken.

Paragraph 10 of the complaint relates entirely to the contents

of depositions alleged to have been taken in a different lawsuit.

That action was dismissed before the defendant filed any answer

and there was never any hearing on the merits of that case.

In the second sentence of Paragraph 10 it is alleged that those

depositions contained “ information providing ample support for

plaintiffs’ contention that the defendant Board did not utilize the

North Carolina Pupil Placement Act as a method by which chil

dren assigned initially on a racial basis, could obtain interracial

transfers Tor the asking’ ” . Not only is this a pleading of evi

21

dential matter; it is a pleading of immaterial evidential matter.

The depositions in question were taken, hut, since the case was

never called for trial, they were never offered or admitted in evi

dence. Obj ections to many questions were entered when the deposi

tions were taken and it was stipulated therein that other objections

could be made when and if the deposition was offered at the trial

of that former case. Wone of these objections has been ruled upon.

To have allowed this allegation to remain in the present complaint

would have required this defendant to go through two very lengthy

depositions, not related to the present litigation, and show from the

depositions themselves the falsity of the present allegation in Para

graph 10 o f the complaint.

This allegation in Paragraph 10, by inference, states and rests

upon a false conclusion of law by the plaintiff, namely, that the

Worth Carolina Pupil Assignment Act should be used to provide

“ interracial transfers for the asking” . That Act prescribes certain

standards by which an application for reassignment must be judged

by the Board. Wo' transfers, interracial or other, are to he given

under the Worth Carolina Pupil Assignment Law “ for the asking” .

Paragraph 10 of the complaint does not purport to allege any

violation by this defendant in this action of the Worth Carolina

Pupil Assignment Act. On the contrary, Paragraph 4 specifically

alleges that the defendant is presently operating the public schools

“ pursuant to said laws” .

Sub-paragraphs (a ), (b ), (c) and (d) of Paragraph 10 purport

to he summaries of the depositions referred to in the first part of

the paragraph. This is, of course, a pleading of evidential matter

and evidential matter which relates to an entirely different lawsuit.

To have allowed these allegations to remain in the complaint would

have required the defendant in its answer to allege, in detail the

defendant’s construction of these depositions and its interpretation

of various portions of the Worth Carolina Pupil Assignment Act.

Such pleadings would unnecessarily complicate and clutter the

record of this lawsuit and prolong the trial of it.

An illustration of the irrelevancy of Paragraph 10 and all of

its sub-paragraphs, and of the complexity which they would neces

sitate in the answer of the complaint by the defendant, is seen in

the second sentence of sub-paragraph (a ). Wone of the plaintiffs

22

is a teacher. None of the plaintiffs is authorized to maintain this

action on behalf of any teacher. This defendant has no authority

under the law to assign any teacher to any school other than that

in which the teacher has contracted to teach. This defendant has

no authority under the law to elect any teacher. I f this allegation

had been allowed to remain in the complaint, the defendant, in

order to absolve itself from the implied charge that it has im

properly employed Negro teachers to teach these Negro children,

would have had to answer by alleging in detail how teachers are

elected and would have had to show that the plaintiffs are not

damaged by receiving instruction from Negro teachers.

In sub-paragraph (c ), of Paragraph 10, the plaintiffs allege

that these depositions taken in the former action would show that

“ no information is provided to Negroes as to what standards they

must meet in order to obtain transfer.” Those standards are pre

scribed by the North Carolina Pupil Assignment Act and the pub

lished rules of the defendant Board. There is no contention any

where in the complaint or in the evidence offered at the hearing

that the defendant has departed from the statute with reference to

requests for reassignment.

Sub-paragraph (d) of Paragraph 10 of the complaint relates to

what the depositions taken in the former action would show con

cerning the defendant’s interpretation of the North Carolina Pupil

Assignment Act. It is an allegation concerning the defendant’s

understanding of the law, not an allegation concerning facts upon

which the plaintiff is entitled to relief. The legal training of the

defendant Board is not relevant in this complaint and allegations

as to evidence in another lawsuit concerning its knowledge of the

law should be stricken as irrelevant to the action.

I ll

T h e D is tr ic t C ourt D id N ot E rr I k R efusing T o A dm it

E vidence Offer ed B y T h e P l a in t if f s .

(a) The Depositions of Gerald D. James and H. Maynard

Hicks.

At the hearing of their motion for preliminary injunction the

plaintiffs called as their witnesses Gerald D. James, Superinten

23

dent of Schools, and H. Maynard Hicks, Chairman of the de

fendant Board of Education, and examined them at length. At the

conclusion of their testimony the plaintiffs sought to put in evi

dence depositions of these witnesses taken in 1961 for possible use

in the action brought in 1960 by the five Negro pupils who in

1959 applied for reassignment to the Walstonburg High School.

(Appendix to plaintiffs’ brief, page 203a.) The District Court

sustained the defendant’ s objection.

The depositions in question do not appear in the record, so

there is no showing that their exclusion, if error, was prejudicial

to the plaintiffs. Without such showing the denial of the motion for

preliminary injunction should not be disturbed.

Furthermore, the exclusion of these depositions was proper. As

this record shows (Appendix to plaintiffs’ brief, pages 5a, 48a,

204a), the action in connection with which those depositions were

taken was dismissed as moot. No answer was ever filed. No trial

of the merits was had. No use of the depositions was made. No

court ever has passed upon the numerous objections stated therein

and, of course, no court, has passed upon objections yet to be stated

upon the reservation of right to enter other objections if and when

the depositions were offered at the trial of that action.

This case is a wholly different action brought by different plain

tiffs and involves different issues.

Rule 26 (d) (4) of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, re

lied upon by the plaintiffs in their brief, is not applicable. This is

not an instance of substitution of parties in the same action in

which the depositions were taken. This is an entirely different

action. This is not “ another action involving the same subject

matter . . . brought between the same parties or their representa

tives or successors in interest” . The subject matter of the earlier

action, in which the depositions were taken, involved the alleged

right of five Negro pupils to be assigned, pursuant to their applica

tions, to the Walstonburg High School, which school is no longer

in existence and none of which pupils is now enrolled in the

Greene County public schools. The subject matter of the present

action is the alleged right of two different pupils to go to whatever

school they wish to attend, without even bothering to apply to the

Board for reassignment, and the alleged right to have teachers,

24

principals and other school employees assigned to duties in schools

other than those in which they contracted to work. The present

plaintiff pupils are not successors in interest or representatives of

the plaintiff pupils in the former case, which was dismissed.

Rule 26 (d) (2 ), also relied upon by the plaintiffs in their

brief, is likewise inapplicable. That rule deals only with the pur

pose for which a deposition may be used, assuming that the

deposition is “ admissible under the rules of evidence” . It does not

purport to state what depositions are admissible.

The depositions covered one hundred seven pages of transcript.

(Appendix to plaintiffs’ brief, page 205a.) Neither of them was

ever offered in evidence in the case in which it was taken. That

case was dismissed without any trial of the merits when it became

moot through all of the plaintiff pupils therein having graduated,

dropped out of school or moved out of the county. The numerous

objections to specific questions in those depositions (See, Appendix

to plaintiffs’ brief, page 205a) were never considered. Thus the

admissibility of the answers to those questions in the case in which

the depositions were taken has not been determined. Before the

District Court in this case could have admitted the depositions,

in their entirety, as offered, it would have had to go through one

hundred seven pages of transcript and rule upon all the objections

therein stated with reference to that case, and upon all such

further objections as might be made with reference to the present-

case.

The same men testified in person in this case. Any question in

the depositions, relevant to and proper in the present case, could

have been asked while the same witness was on the stand in the

present case. These witnesses were not called by the defendant.

They were the plaintiffs’ witnesses, so the depositions could not be

used to impeach them even if it could be assumed that they would

contradict any testimony given in the present case, which the plain

tiffs did not contend before the District Court (Appendix to plain

tiffs’ brief, pages 202a to 208a) and do not now suggest in their

brief. “ At a de novo trial, testimony at prior hearing is inadmissi

ble unless it is shown that the presence of the witnesses who testi

fied at the hearing cannot be secured.” De Vargas v. Brownell,

251 F. 2d 869 (5th Cir., 1958).

25

Had the Court allowed the plaintiffs to introduce these deposi

tions in evidence, it would have been necessary for the defendant

to have offered evidence to show the propriety of its actions in the

matter of the five applications in 1959. The plaintiffs cannot, by

this device, try in this action the merits of the former action, dis

missed as moot prior to the bringing of the present action.

(b) The Record of the 1959 Hearing Before the Board.

At the hearing in the District Court the plaintiffs called as their

witness, H. Maynard Hicks, Chairman of the defendant Board.

Counsel for the plaintiffs examined Mr. Hicks extensively con

cerning the Board’s action upon the simultaneous applications in

1959 of five Megro pupils for reassignment to the Walstonburg

High School, now closed, and with reference to the hearing held

by the Board upon those applications. The witness answered all

such questions. In the midst of his direct testimony on this matter,

counsel for the plaintiffs offered in evidence the record of the

hearing held by the Board in 1959 upon those applications. In so

doing, counsel for plaintiffs stated this was not offered for the

purpose of impeaching the witness (Appendix to Plaintiffs’ Brief,

page 186a), which he could not do, of course.

The document in question is not included in the record before

this Court so there is no showing of any prejudice to the plaintiffs

resulting from this ruling, even if it was erroneous, which is not

the case. Without such showing, the ruling of the District Court

on the motion for preliminary injunction should not be disturbed.

The hearing in question was an informal, administrative pro

ceeding at which unsworn statements were received by the Board

concerning the alleged right of five pupils, then, but no longer, in

the Greene County public schools, to be reassigned, pursuant to

applications filed with the Board, to a high school then, but no

longer, in existence. The present case involves the alleged right

of two different pupils to attend the school of their choice without

even making any application to the Board of Education. The state

ments made in 1959 by those applicants concerning their alleged

rights to attend the Walstonburg High School, even if they had

been made under oath, which was not the case, would not be rele

vant to the alleged right of these present plaintiff pupils to go to

the school of their choice without even applying to the Board for

26

a reassignment. The District Court did not, therefore, err in sus

taining the objection to the introduction in evidence of that collec

tion of unsworn, irrelevant statements.

C O N C L U S I O N

Since the District Court did not err in denying the motion of

the plaintiffs for a preliminary injunction, or in striking Para

graphs 9 and 10 from the complaint, or in sustaining objections

to the introduction in evidence of depositions taken, but never used,

in a different lawsuit and of the transcript of an administrative

hearing by the Board of Education four years before the present

action arose concerning applications not involved in the present

action, the orders of the District Court from which this appeal

was taken should be affirmed.

Respectfully submitted

W alte r . G. S h eppar d ,

Snow Hill, North Carolina

K . A. P it t m a n ,

Snow Hill, North Carolina

I . B ev er ly L ak e

800 Capital Club Building,

Raleigh, North Carolina

Attorneys for the Appellee

27

A P P E N D I X

G en er al S tatu tes of N orth Carolin a

Chapter 115, Article 21

Assignment and Enrollment of Pupils

§ 115-176. Authority to provide for assignment and enrollment

of pupils; rules and regulations.— Each county and city board of

education is hereby authorized and directed to provide for the

assignment to a public school of each child residing within the

administrative unit who is qualified under the laws of this State

for admission to a public school. Except as otherwise provided in

this article, the authority of each board of education in the mat

ter of assignment of children to the public schools shall be full

and complete, and its decision as to the assignment of any child

to any school shall be final. A child residing in one administrative

unit may be assigned either with or without the payment of tuition

to a public school located in another administrative unit upon such

terms and conditions as may be agreed in writing between the

boards of education of the administrative units involved and en

tered upon the official records of such boards. No child shall be

enrolled in or permitted to attend any public school other than the

public school to which the child has been assigned by the appro

priate board of education. In exercising the authority conferred by

this section, each county and city board of education shall make

assignments of pupils to public schools so as to provide for the

orderly and efficient administration of the public schools, and pro

vide for the effective instruction, health, safety, and general welfare

of the pupils. Each board of education may adopt such reasonable

rules and regulations as in the opinion of the board are necessary

in the administration of this article. (1955, c. 366, s. 1; 1956,

Ex. Sess., c. 7, s. 1.)

§ 115-177. Methods of giving notice in making assignments

of pupils.—In exercising the authority conferred by § 115-176,

each county or city board of education may, in making assignments

of pupils, give individual written notice of assignment, on each

pupil’s report card or by written notice by any other feasible

means, to the parent or guardian of each child or the person stand

ing in loco parentis to the child, or may give notice of assignment

of groups or categories of pupils by publication at least two times in

28

some newspaper having general circulation in the administrative

unit. (1955, c. 366, s. 2 ; 1956, Ex. Sess., c. 7, s. 2.)

§ 115-178. Application for reassignment; notice of disapprov

al; hearing before board.— The parent or guardian of any child,

or the person standing in loco parentis to any child, who is dissatis

fied with the assignment made by a board of education may, within

ten (10) days after notification of the assignment, or the last pub

lication thereof, apply in writing to the board of education for the

reassignment of the child to a different public school. Application

for reassignment shall be made on forms prescribed by the board of

education pursuant to rules and regulations adopted by the board

of education. I f the application for reassignment is disapproved,

the board of education shall give notice to the applicant by regis

tered mail, and the applicant may within five (5 ) days after re

ceipt of such notice apply to the board for a hearing, and shall be

entitled to a prompt and fair hearing on the question of reassign

ment of such child to a different school. A majority of the board

shall be a quorum for the purpose of holding such hearing and

passing upon application for reassignment, and the decision of a

majority of the members present at the hearing shall be the deci

sion of the board. If, at the hearing, the board shall find that the

child is entitled to be reassigned to such school, or i f the board shall

find that the reassignment of the child to such school will be for the

best interests of the child, and will not interfere with the proper

administration of the school, or with the proper instruction of the

pupils there enrolled, and will not endanger the health or safety

of the children there enrolled, the board shall direct that the child

be reassigned to and admitted to such school. The board shall

render prompt decision upon the hearing, and notice of the decision

shall be given to the applicant by registered mail. (1955, c. 366,

s. 3 ; 1956, Ex. Sess., c. 7, s. 3.)

§ 115-179. Appeal from decision of board— Any person ag

grieved by the final order of the county or city board of education

may at any time within ten (10) days from the date of such order

appeal therefrom to the superior court of the county in which such

administrative unit or some part thereof is located. Upon such

appeal, the matter shall be heard de novo in the superior court be

fore a jury in the same manner as civil actions are tried and dis

posed of therein. The record on appeal to the superior court shall

29

consist of a true copy of the application and decision of the board,

duly certified by the secretary of such, board. I f the decision of the

court be that the order of the county or city board of education

shall be set aside, then the court shall enter its order so providing

and adjudging that such child is entitled to attend the school as

claimed by the appellant, or such other school as the court may find

such child is entitled to attend, and in such case such child shall be

admitted to such school by the county or city hoard of education

concerned. From the judgment of the superior court an appeal may

be taken by an interested party or by the board to the Supreme

Court in the same manner as other appeals are taken from judg

ments of such court in civil actions. (1955, c. 366, s. 4.)

30

G e n e r a l S t a t u t e s o f N o r t h C a r o l i n a

Chapter 115, Article 7

School Committees — Their Duties and Powers

§ 115-72. How to employ principals, teachers, janitors and

maids.— The district committee, upon the recommendation of the

county superintendent of schools, shall elect the principals for the

schools of the district, subject to the approval of the county board

of education. The principal of the district shall nominate and the

district committee shall elect the teachers for all the schools of the

district, subject to the approval of the county superintendent of

schools and the county board of education. Likewise, upon the rec

ommendation of the principal of each school of the district, the dis

trict committee shall appoint janitors and maids for the schools of

the district, subject to the approval of the county superintendent

of schools and the county board of education. No election of a

principal or teacher, or appointment of a janitor or maid, shall be

deemed valid until such election or appointment has been approved

by the county superintendent and the county board of education.

No teacher under eighteen years of age may be employed, and the

election of all teachers and principals and the appointment of all

janitors and maids shall be done at regular or called meetings of

the committee.

In the event the district committee and the county superinten

dent are unable to agree upon the nomination and election of a

principal or the principal and district committee are unable to