Wheeler v. Montgomery Brief for Appellees

Public Court Documents

August 28, 1969

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Wheeler v. Montgomery Brief for Appellees, 1969. 296093ec-c89a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/6d6e4133-852f-4d6d-a5c4-462b46efea0a/wheeler-v-montgomery-brief-for-appellees. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

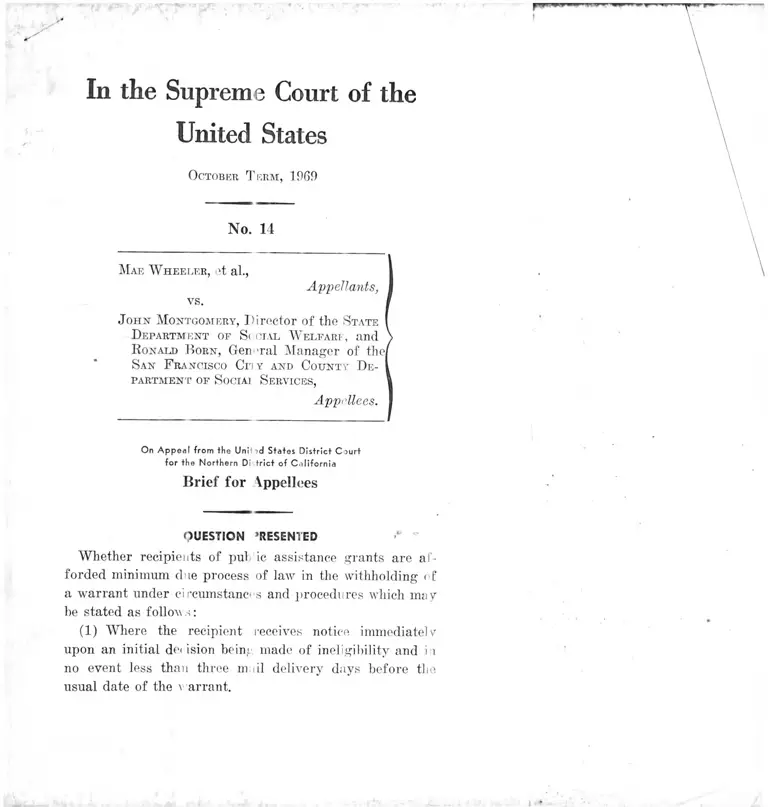

In the Supreme Court of the

United States

October T erm, 1969

No. 14

Mae W heeler, et al.,

Appellants,

vs.

John M ontgomery, Director of the State

D epartmi:nt of Sccial W elfare, and

Ronald B orn, Gen >ral Manager of the/

San F ra ncisco Ch y and County De

partment of Sociaj S ervices,

Appellees.

On A p p ea l from the Unil States District C iu r t

for the Northern D: trict of Ca l iforn ia

Brief for \ppellees

OUESTION ’RESENTED

Whether recipients of pul ic assistance grants are af

forded minimum due process of law in the withholding of

a warrant under circumstanens and procedures which may

he stated as follov s :

(1) "Where the recipient receives notice immediately

upon an initial decision be ini made of ineligibility and in

no event less than three mail delivery days before the

usual date of the \ arrant.

2

(2) Where the notice or notification specifies and con

tains the following elements:

(a) The county’s propo 'd action,

(b) the grounds therefor,

(c) information needec or action required of the

recipient to determine eli ibility,

(d) that the recipient with legal counsel or other

person may meet with an agency n presentative at a

specified time or during a specified time period of not

exceeding three working days, the last day of which

shall be at least one day prior to the usual delivery

date of the warrant at wli eh time:

(e) the county’s eviden e will be ally disclosed,

(f) the recipient shall have the opportunity to pro

duce the information or e planation referred to in (c)

above and any other infoi mation he desires, and,

(g) the entire matter will be discussed for clarifica

tion and, where possible, resolution.

(3) where the warrant may be withheld only when the

county’s evidence is substantial in nature and reliable in

source indicating probable ineligibility.

STATUTES AND REGULATIONS INVOLVED

’I’lie present < ase involves the constitutional, statutory

and regulatory provisions set forth in the single appendix

heretofore filed with this court under Rule 3(5 (hereinafter

referred to as “A ” ).

The case also involves the Department of Health, Educa

tion and Welfare (HEW) Handbook of Public Assistance

Administration (hereinafter referred to as Federal Hand

book) Part IV, sections 2300 (d), (e), (f). and (g) “ Criteria

foi the Administration of the Plans” and section (1400 "In

terpretation” which are set forth in Appendix I to the

instant brief pages 1 through 5 (the Appendices infra will

be referred to as “ App.” )

The present case also involves California Welfare md

Institutions Code sections 12200-12202 set forth in Appen

dix IT page 6, infra.

Also involved herein are the following: the California

State Department of Social Welfare Public. Social Services

Manual (hereinafter referred to as PSS) section 44-325

“ Changes in Amount of Pa ment” : section 40-155 “ P in-

ciples and Methods of Investigation” ; section 40-1S1 “ ( on-

tinuing Activities and Tnvesi gation” ; section 48-001 “ C< un-

ty Department Responsibili y for Case Records” ; sec ion

48-013 “Inspection of Records by Applicant or Recipient” ;

which are set forth in Appendix III infra, pp. 7-20.

Further to be considered is the California State Depart

ment of Social Welfare Op< rations Manual section 22 109

“ Request for Review and Fair Hearing: County Depart

ment Responsibility” ; section 22-113 “ State Department of

Social Welfare Responsibility” ; and recommended proce

dures set forth in section 22-200 “ Client Complaints md

Fair Hearings in Public Social Services” ; section 22 203

“ Concepts and Considerations” ; section 22-203.4 “Wri ten

Confirmation of County Welfare Department Action” ; ;ec-

tion 22-205 “ Establishment of Complaints and Appeals

Unit” which are set forth in Appendix III infra pp. 20- 0.

ST A" 1MENT

Appellant, Mrs. Wheeler, >s of August 30, 1907, recei md

monthly Old Age Security lOAS) benefits in the ameunt

of $113.95 and Social Securil y benefits of $14.00 per month.

(A.50) On August 30, 1907. the San Francisco City and

County Department of Sue il Services received informa

tion that Mrs. Wheeler lm 1 received some $0,000.01 in

insurance proceeds and otlie death benefits upon the d< ith

of a son. (A.42) On the same day the county agency q es-

3

ti( icd Mrs. Wheeler by tele] one about this. She admitted

rei living these funds, and in >rmed the county that during

A| ril 11)67 she had transfer] 1 a Veterans Administration

cli ck for $4,528.15 to her gra Ison, nephew of the deceased

so in accordance with the equest of her deceased son

(A.56)^ Although Mrs. Wh *]er during this five-month

pe 'iod on several occasions had been in touch with her

so ial worker, she did not r port receipt of any of these

fu ids (as required by Cal We f & Inst Code § 12203) (A.42).

Che county withheld Mrs. Wheeler’s September 1, 1967

w< ifare check pending com iletion of its investigation.

( / .56)1

)n November 7, 1967 the oi nty agency concluded that

th transfer was made to avoid discontinuance of welfare

benefits and determined tha Mrs. Wheeler’s action ren-

de ed her ineligible for contii led benefits.2 (A. 42)

During the months of Sep ■mber and October and until

ab mt November 10, 1967, M s. Wheeler lived on her “ al

lowable reserve” and Social Security payments (A. 17).3

T) e “allowable reserve” for OAS may not exceed $1200.00

ca h.4

Ybout November 25, 1967 she received an emergency food

or ler from the county for $15.60, presumably as a result of

having notified the county that her reserve funds were

ex lausted. (A. 18) With no cash assets she was considered

1. PSS 44-325.423 effective April 1, 1908 prohibits such pre

cipitous county suspension.

•. Cal. Wei. & Inst. Code § 1:4)50(e).

'!. The allegation that for nearly three months appellant sub-

sis'ed solely on her $44.60 monthly Social Security check does not

conform to the facts (A.B. 6).

1. Cal. W elf. & Inst. Code § 11154.

eligible for County General Assistance as of Decemb< r 1,

19G7 in the sum of $53.90 (A. 57)5 6

Appellant’s request for a fair hearing was filed No 'em

ber 21, 19(57 (A. 41).° The hearing was originally sched

uled for December 15, 19(57. Tt was postponed at Mrs.

Wheeler's request and came on for hearing on December

22, 1967. (A. 39-40). The referee’s decision was ad( pted

by the Director of the State Department of Social Wo fare

on January 12, 1968 (A. 57). The decision ordering Mrs.

Wheeler restored to OAS effective September 1, 1965 (A.

57) was rendered within 52 days of her request foi the

hearing. The HEW regulation (Hand Book of F iblic

Assistance Administration section 6200( j )) not eff< dive

until July 1, 1968, requires the hearing and decisi- n to

be made within 60 days of the request for a hearing (A 65).

Old Age Security payments were restored by a rtue

of a temporary restraining order issued by the court 1 elow

on December 1967. The district court judge entered a class

action order concluding that the prerequisites of Fe deral

Rules of Civil Procedure 23(b) (2) were met. The court,

finding that the provision; of 42 USC section 2281 were

satisfied, ordered the convening of a three judge c mrt.

Appellee John Montgomery, Director of the California

5. The Sun Francisco General Assistance program, financed

solely by the county, not only includes the cost of living ex enses

in accordance with the gene ml assistance standards hut in dudes

as well such special needs as ■ pecial diet allowances and nee ssary

medical care. (Declaration of Ronald H. Born, December 1 1967

Docket Entries 7-8 A. 1) Mrs. Wheeler was receiving n 'dical

care at Hahnemann Hospital in late November 1967 when si > exe

cuted her Affidavit in Supper of Motion for Temporary Re train

ing Order (A . 18).

6. Mrs. Wheeler could luu e requested a fair hearing ii medi

ately upon being notified that her welfare check' was being wi lheld.

Cal.' W elf. & Inst. Code § 1 ()!)• (). Operations Manual Section 12.021

requires “ Written Notice of the right to a fair hearing si ill be

included in every Notification . . of the . . . suspension of aiu . . .

5

G

1 tate Department ol Soci; Welfare tin n promulgated

R egulation PSS 44-325.43. rJ lie court below found that the

i ‘gulation comports with C e due process clause of the

1 ourteenth Amendment to 1 ie United States Constitution

a* d dismissed the action. (A. 45).

e

SU M M ARY C ARGUMENT

The essence of Appellant attack upon the decision of

t e court below is contains in Appellants Jurisdictional

f atemont, page 16, heading ! :

̂ F. I he informal c< • iference prior to termination

and the I1EW lair hearing after termination

do not combine to meet due process of law.

“ The lower court opinion was based upon a feeling

that a combination ol the informal c( nference prior

to termination and the fair hearing after termination

would jointly create due process of law.”

However, Appellants are unable to cite authority directly

in point with their above c utention but rather rely on

ca-;es which state broad cons tutional principles.

Conversely, the correctness of the decision of the court

be oav and the constitutional ■ p\ ol the notiee and hearing

provisions herein involved must be measured in light of

tli fact that: (1) determinations as to continued eligibility

must be made promptly and no less often than once a

111 "ntli with respect to over one and one-quarter million

pi blic assistance recipients, a id (2) the State of California

provides recipients with the fair hearing process called

for and required by both the Social Security Act and the

provisions of state law (Welfare & Institutions Code

§§ 10950-10905); the latter providing for judicial review.

With approximately 1,276,000 recipients of the various

categorical aid programs in California, County welfare

departments must make an (mormons number of decisions

daily respecting continued eligibility—and thus must de

velop a rapid method of fairly determining whether to sus

pend, terminate or withdraw public assistance grants for

all recipients. The number of determinations required and

the need for an expeditious and fair review of these le-

terminations are essential factors in assessing the con: ti-

tutional adequacy of the regulation and procedures uph hi

by the court below.

ARGUMENT

I. The California Suspension and Termination of Aid Procedt res

Fully Comport with Due Process Requirements

IN T R O D U C T IO N

The State of California does not dispute the right of

welfare recipients to some bearing prior to suspension or

termination of aid. This is precisely the claim originally

pressed by appellants (A. 13). After this action was in

stituted and the temporar; restraining order issued, ap

pellee John Montgomery, D rector of the California State

Department of Social Wei are, adopted new regulations

to implement existing proe lures to assure that prc-wi h-

holding of aid procedures v add meet due process require

ments. At no time howev< , has appellee conceded that

there is a constitutional < titlement to welfare benefits

with the concomitant entitle: tent to the protections required

for First Amendment right.

Due process is a flexible oncept dependent on the ] ar

ticular circumstances.

“The very nature of < ue process negates any concept

of inflexible procedures iniversally applicable to ev my

imaginable situation.’ ' -afeteria £ Restaurant Work

ers Union etc. v. McK, oy, 3(17 IT.S. 886, 895 (1961)

“ [D]ue process,” unli 1 some legal rules, is not a

technical conception wiili a fixed content unrelated to

time, place and circumstances. . . Joint Anti-Fascist

Comm. v. McGrath, 341 U.S. 123, 162-163 (1951) (con

curring opinion).”

7

' 'lie pre-withholding invest gation and post conference

procedures discussed below, ; well as the pre-witliholding

coi ference, demonstrate tha these combined procedures

act ord aid recipients all of he due process that is con

stitutionally required.

A. A N fo vE S T IG A T IO N CONDUCTEC W ITH THE C O N SE N T O F THE RE

C IP IEN T PRECED ES N O T IC E O F i ilT IA L D E C IS IO N TO W IT H H O L D A

W A R R A N T

lie notice given a recipien , pursuant to PSS 44-325.43,

ol the county’s initial decision to withhold a warrant, does

no come as a bolt from the b ie. Eligibility is reconsidered

an ‘ redetermined periodicall and whenever the situation

requires it. (Federal Handbook Part IV, 2300(d) App. 1

p. .) Roinvestigation entails a personal interview with the

rec pient.7 (PSS 40-181.3.)

EW has made explicit tha “ in the process of determin

ing initial and continuing eligibility: . . .

(2) i’he agency takes no steps in the exploration of

eligibility to which the applicant or recipient does not

agree; it obtains specific consent for outside contact

(whether with social agencies, doctors, hospitals, and

similar resources, or with relatives or other indi

viduals); the consent covers the purpose of the con

tact as well as the individual or agency to be consulted;

and where collateral sources are contacted, a clear

interpretation is furnished of w hat information is de

sired, why it is needed, and how it will be used. Tf

other procedures are followed in an exceptional situa

tion, they are consistent with lV-2200(a) and TV-

2300 (a), and the case record specifies the reasons why

7 In McCullough v. Tcrzian, now pending in the Court of A p

peal State of California, First Appellate District, 1 Civil No.

25830 and dealing with this same issue, Mrs. McCullough, prior

to being interviewed by a county investigator, was advised that

she had a right to have counsel present at the interview. At the

interview the evidence regarding ineligibility was discussed with

her. (CT (14-71)

they were needed and the specific procedures fol

lowed.” (Federal Hand Book Part TY 2300(e)(2).)

State regulations are to the same effect, (PSS 40-155.24,

App. TIT, p. 12; PSS 40-181.31, p. 14). Information secured

shall he evaluated qualitatively rather than quant itively and

in light of its internal consistency (PSS 40-155.1, App. IT,

p. 10). Only when the evidence “ is both substantial in

nature and reliable in source” indicating probable ineli ;i-

hUity of recipient is the not ce given under PSS 44-325 13

(PSS 44-325.421 App. 1 IT. p. 7).

The initial decision regarding probable inelligibilitv must

he based on adequately substantiated facts, not rumor,

gossip or surmise.

9

B. THE REG U LAT IO N PRO V ID ES FOP A D EQ U A T E A N D Y IM ELY N O T IC E

PSS 44-325.43 provides that the recipient shall be no!i-

fied of the county’s initial decision to withhold welfa 'e

benefits and the grounds therefor at least “ three (3) m; il

delivery days prior to the usual delivery date of the wa -

rant.” The notice must stab in addition to the grounc 5

lor the proposed action “what information, if any, is neede I

or action is required to re-establish eligibility or to dote -

mine a correct grant.” Also, the regulation requires a. hon e

call by appropriate personnel if the county has reason to

believe that the notice may not be delivered or the recipient

will not understand it. This < learlv meets the duo process

requirement that there be . . notice reasonably ca7

ciliated, undei all the circum ances, to apprise interest!

parties of the pendency of (1 > action and afford them a

opportunity to present their o! jections.” Mullane v. Centro

Hanover Tr. Co., 359 U.S. 3Cb, 314; Schrocder v. City ,

New York, 371 U.S. 208, 211.

These regulations require a recipient to he more fulh

informed of the grounds for the county’s proposed actioi

than the California Administrative Proceduie Acts requires

for the initiation of full scale a,judicatory proceedings

against the holder of a business or professio lal license, e.g.,

(h ctor, pharmacist, barber, pest control operator, etc.

Government Code section 11 503 provides in relevant part:

r“A hearing to determine whether a right, authority,

license or privilege sir uld lie revok >d, suspended,

limited or conditioned s lall be initiated by tiling an

accusation. The accusation s!iall be a written state

ment of charges which s all set forth i i ordinary and

concise language the act or omissions with which the

respondent is charged, t< the end that the respondent

will be able to prepare h s defense. It s iall specify the

statutes and rules which the respondent is alleged to

have violated, but shall not consist merely of charges

phrased in the language < f such statutes and rules . .

California provides that tin welfare case record shall be

open to inspection by the recipient and his authorized

representatives at all times. PSS 48-013, App. Ill p. 20.)

Eligibility investigation repc ts including “ the pertinent

information obtained during the investigation, and, the

sources from which relevant < ata was secured,” art1 part of

the case record. (PSS 48-001.11, App. Ill pp. 17-18.) (See

also Cal Welf & Inst Code § 10850.1)

This is not true for the In Ider of a business or profes

sional license. Only after the accusation is filed does the

licensee have limited right of discovery. (Calif. Gov. Code

§ 11507.6.) Thus, there is no relevant comparison between

a minimum of three mail deliv my days’ notice for a welfare

recipient to answer and the twenty-five days for answer

un ler the California Administrative Procedure Act. (Gov.

Code §§ 11505(b) and 11509.9)

Notice of charges of student misconduct received two

days before the disciplinary hearing, was held to lie ade-

f:. California Government Code §§ 11500-11528.

! . Amicus curiae brief App. B, p. 13.

10

11

quate and timely by the court in .Tones v. State Board of

Education of and for State of Tenn., 279 F.Supp. 190, 0)9

(M.D.Tenn. 1968). The court in Jones pointed out thal in

Due v. Flordia A.SM. University, 233 F.Supp. 396 (N.R.Fla.

1963) “a letter was read to the students for the first time

at the hearing against them. This was the only notice of lie

charge that the plaintiffs were afforded, yet the court held

the notice to be both adequate and timely.”

Appellants allege that the conference is not schedul ‘d

for a particular time or with a particular person and t ic

recipient is not advised of her right to appear. (Appellan s’

Brief p. 11.) Appellants disregard the specific requiremei ts

of PSS 44-325.434 that the recipient be informed that !ie

“ may have an opportunity to meet with his case worker, m

eligibility worker, or another responsible person in t'ie

county department, at a specified time or during a git en

time period . . . at a place specifically designated. . . .” (E n-

phasis added.)

The “ Notice of Action” ( Appellants’ Appendix V pp.

21-22) is only one piece of the information required by 1he

regulation. If the only information received by a recipient

was the notice of action as alleged by appellants,10 11 there

has been a clear violation if the regulation. The noti ;e

form, if used, must be aecom >anied by a letter or otlierwi <Q

include the information regarding:

(1) The right to, an 1 time and place for a c< i-

ference;

(2) the grounds for t ie proposed action;

(3) what informatioi is needed from the recipie t;

(4) his right to be n iresented at the, conference. 1

10. Appellants’ Brief p. IS.

11. Operations Manual 22-2' 1.4 App. I l l , p. 22.

12

in addition, tlie recipient is advised that the evidence

r yarding ineligibility will be fully discussed with him and

h i representative. Further, this information is available at

a v time by inspecting the case record.

Vompt resolution of questioned eligibility is clearly to

tii recipient’s advantage. In California eligibility for an

f VS grant is not dependent on indigency.12 If aid is re

el' ired to be paid pending a fair hearing and the recipient

i found ineligible the county may obtain restitution.13 This

m v entail exhaustion of reserve lands, sale of home prop

er v and other assets to the same extent as any other judg-

n lit debtor.

A. quick and simple procedure is to the advantage of the

e mty and state as well as the recipient in obviating the

I le consuming process of (the fair hearing. Moreover,

“ ! rotection of the fisc” has not been rejected by the appel-

ha s.14 The statement “ cost to the state has not been put in

is; ue” was largely based on the incompleteness of the

statistics on such costs stemming from the McCullough

peremptory writ. The Calif >rnia. Court of Appeal com-

m nted that the proferred “ e idence” did not purport to be

a urate.

C THE P R E -W IT H H O L D IN G O F A ID C O N FER EN C E , D ES IG N ED TO A FFO R D

REC IP IEN TS PRO M PT R ESO LU T IO N O F EL IG IB IL ITY Q UEST ION S, M EETS

DUE P R O C E SS R EQ U IREM EN TS

Che pre-withholding of aid conference conforms to

II IW ’s requirement for:

“ Effective complaint and adjustment procedures,

whereby corrective action may be easily requested and

readily taken without the need for a [fair] hearing,

12. See San Bernardino County v. Simmons, 4(> Cal. 2d 394, 400,

2!)i» Pac. 2d 329, (1956).

13. Cal. W elf. & Inst. Code §§ 12203, 12205.

14. Appellants’ Br. pp. 16 n. 17, 17.

13

are necessary, when indicated. Advance opportunity

afforded the recipient 1o respond to questions which

could result in change of grant or termination is a

significant part of such procedures. So is written, nd

whenever practical, oral information of the reasons for

change, denial, or termination. This is particularly

important where the agency decision is based on judg

mental factoi's or eligibility, requirements that entail

evaluative decisions on the part of workers, as com

pared to decisions based on non-debatable facts (su h

as receipt of OASI. death, etc.). However, the State

and local agency adjustment procedures cannot be

allowed to interfere with the hearing process.”15 16

1. Confrontation and cross-examination are not essentia! to "due process" at

the time of and under the circumstances of these proceedings

Appellants assert that the regulation is constitutionally

deficient in that it fails to afford the recipient the right * fo

confront and cross exan ine” . This alleged defect is with* at

merit. The court in Dixon v. Alabama State Board of

Education, 294 F.2d, 150, 159 (5th Cir.) expressly rejected

the right to cross-examine witnesses. Nor was such condi

tion considered essential in Knight v. State Board of Educa

tion, (M.D. Tenn.) 200 V. Supp. 174, 178 (1901). In Knight

the court concluded that “ the rudiments of fair play a id

the requirements of due process vested in the plaintiffs

[suspended students] the right to be forewarned or. advis'd

of the charges to lie made against them and to be afford d

an opportunity to pres*' it their side of the case.”

Nonetheless the Dixon and Knight decisions are cited y

Appellants as creating a due process requirement for a “ f 11

trial-type hearing” for students at state schools.1®

15. Federal Handbook Part IV , 6400(a), Ap]>. I, p. 4. See also

section 2300(d) (5 ), App. I, p. 1.

16. Comment, “ Withdrawal of Public W elfare: The Right t > a

Prior Hearing,” 76 Vale L.J. 1234, 1239 (1967).

2. Due process does not require an impartial decision maker for an administra-

tive proceeding such as this one

Kven in a full-scale trial type administrative proceeding

tin combination of ajudicating function with prosecuting

01 investigating functions will not ordinarily constitute a

d< nial of due process. Marcello v. Ronds, 349 U.S. 302, 311

( 155); Federal Trade Comm’n. x. Cement Institute, 333

V S. OSS, 700-703 (1948), Fair/bur, v. C. 1.5., 311 F.2d 349,

370 (1st Cir. 1902); Holt v. Raleigh City Board of Educa

tion, 205 F.2d 95, 98 (2d Cir. 1959) cert. den. 301 U.S. 818.

2 Davis, Administrative Law Treatise (1958) p. 175 et seep

in California an administrative agency need not use the

th > services of an impartial hearing officer unless required

h\ statute to do so. This is so even though the board makes

the initial decision to terminate employment and conducted

its own investigation. Griggs v. Board of Trustees, 01 Cal.

2d 93, 97-98, 37 Cal. Rptr. 194, 389 P.2d 722, (1904).

However in the interest of reaching an immediate and

equitable decision without the necessity of going to a fair

hearing appellee Montgomery has recommended to the

counties the establishment of a Complaints and Appeals

Unit,17 Many counties have such a unit which is separate and

apart from the “ line” , (i.e., case worker, supervisor,) in

volved in the initial decision to withhold aul. Jn the small

counties the unit, necessarily, might be composed solely of

the director.

3 Appellants other due process attacks on the pre-withholding procedures are

not supported by fact or law

Appellants make the unfounded contention that the reg

ulations fail to require a decision based on the evidence at

the hearing or that there even be a decision. The regulations

require full disclosure of the county’s evidence and the

recipient has access to the case records plus the opportunity

17. Operations Manual 22-205, App. H I, p. 24.

14

foi production of whatever information and evidence he

desires to introduce. Tin' county’s decision to terminate aid

or withhold aid for further investigation must lie based m

evidence both substantial in nature and reliable in source

indicating probable ineligibility. Tn Sniadacli v. Family

Finance Corporation, ...... TT.R......... , 37 U.S. Law We >k,

4520 (June 0, 1009) Mr. Justice Harlan concurring

stated, “ I think that due process is afforded only by l ie

kinds of “notice” and “hearing” which are aimed at estab

lishing the validity, or a/ least the probable validity, of the

underlying claim against the alleged debtor before he can

be deprived o! Ins property [wages] or its unrestricted

use.” (Emphasis added.) This is precisely what is requir >d

by the regulation. Substantial evidence has been defined by

this Court as relevant evidence that a reasonable m'nd

might accept as adequate to support a conclusion, that is,

whether a fair and reasonable mind would accept it as

probative1 of the issue.18

Appellants decry the lack of a transcript or record of the

proceedings. Tn Due v. Florida A and M University, 233

E.Supp. (N.T). Florida) .">9(1, -103 (1903) the court held due

process was satisfied in that:

“ There was notice to each of these plaintiffs, the

charge was ni; de explicit, and each was afforded full-

opportunity to lie heard, and, in fact, was heard to Hie

point where each said he had nothing more to say.

“ A fair reading of the Dixon case shows that it is not

necessary to due process requirements that a full scale

judicial trial be conducted by a university disciplinary

committee with qualified attorneys either present or

formally waived as in a felonious charge under the

criminal law. There need be no stenographic or me

chanical recording of the proceedings.”

18. Consolidated Edison Co. v. National Labor Relations Board,

305 U.S. 197, 229 (1938).

15

16

i the instant situation no useful purpose would be served

y making such a record since it is clear that the designated

ext administrative step is the ‘‘fair I aring” which is de

ovo'and transcribed, thus 1 ‘ing available for court review

; fter administrative remedies have been exhausted.

Appellants’ final attack on the regulatory procedure is

1 mt the burden of proof is placed on the recipient to prove

I a is entitled to public assistance; this apparently based on

1 le “ initial ex parte decision to terminate aid.”10

The initial decisions of all administrative agencies

a hether they be to terminate employme it, a driver’s license

i r welfare benefits are ex parte decisions on the part of the

; gency.19 20 The fact that tin1 county agency has made an

initial but still tentative ex parte determination that aid

i muld be withheld cannot be interpretc 1 as constituting an

< ffective shift in the formal and legal concept of burden of

] roof.21

t A V A IL A B L E POST C O N F E R E N C E PR O C ED U R ES A FFO RD REC IP IEN TS A D

D IT IO N A L DUE P R O C ESS

Tf the decision following the conference is not to the

i ecipient’s liking he may request review by the county

d ‘partment staff designated for that purpose.22 This is

< ' particular importance if the conference has been with

the recipient’s social worker or direct supervisor. The reg

ulation requires the review staff to promptly reassess the

recipient’s situation and to take immediate action and effect

19. Appellants’ Brief p. 22.

20. Griggs v. Board of Trusters, 61 Cal. 2d 93, 97, 37 Cal. Rptr.,

194, 389 P.2d 722 (1964).

21. “ This phase of the plaintiffs’ argument resolves itself basi

cally into an unfounded argument of semantics brought by the use

of the word ‘ readmit’ by the F .A .C .” Jones v. State Board of Edu

cation, 279 F.Supp. 190, 202 (M .l). Tenn. 1968).

22. Operations Manual section 22-109. App. I l l pp. 20-21.

any adjustment as may be appropriate. The recipient is

again informed of his right to a fair hearing. Then if the

recipient “has not achieved an understanding with the

county” he may request review by the State Department of

Social Welfare Complaints Staff who shall reassess and

review the situation promptly. The State Staff shall request

the county to promptly reassess the problem and may in

form the county of the intent or meaning of applicable

regulations. The •ecipient is again informed of his rights

to a fair hearing.-3 None of these adjustment procedures,

conferences, county and state review can be allowed to

interfere with the fair hearing process.23 24

Tn Robertson v. Bowman, Civil Action No. 51364 (N.D.

Cal. June 21, 1969) the Court order for a full hearing p lor

to termination of county welfare, does not support appel

lants’ contention that the procedures before this Court are

inadequate.25 26 The- basis for the Court’s order in Bober son

was that the county had no procedures at all prior to ac ual

notice of termination with no provision for a fair healing

following termination. General assistance in California is

financed and administered solely by tbe county under ] ro-

cedures and standards determined solely by each indivic ual

county.

As of July 1, 1968, TIIOW has required that the heaiing

and decision be made within 60 days from the request for

the fair hearing.2'1

23. Operations Manual sections 22-113. App. ITT p. 21.

24. Federal Handbook Part IV section 6400(a). A}ip. I p. 4.

25. Appellants’ Grief p. 23.

26. Federal Ilam book Part IV, section 6200 ( j ). California lias

not been able to achieve full compliance with the 60-day reqi de

ment because of th greatly increased welfare caseload and the

number of requests i >r fail hearing with no comparable increas in

the number of hearing referees.

17

Thus there is provision for i “ trial” which is to be held

and decided within a limited and defined time following

wi hholding or termination of aid;27 precluding the defects

ap »ellants attribute to the pre-withholding of aid pro

cedures.

II. The Social Securify Act Does Not Require Continuation of

Welfare Assistance Pending a Fair Hearing

'idle Social Security Act in plain and simple language

requires a state plan to “ Provide for granting an opportu

nity for a fair hearing before the State agency to any

individual whose claim for assistance under the plan is

d mied or is not acted upon with reasonable prompt-

n ss. . . .”2S

There is nothing in the foregoing that hints, implies, or

insinuates that the “ fair hearing” must be held before

a sistance is suspended or denied. The Department of

Health, Education and Welfare has not heretofore so in

terpreted it. The HEW regulation requiring continuation

of aid pending the fair hearing decisions was originally

issued in proposed form on November 3d, 1968, to be etlec-

tive July 1, 1969, (33 Fed. Reg. at 17853) as the result of

a promise made by then Secretary Cohen to the Reverend

Ralph Abernathy.29 There is no evidence that it was the

result of intensive analysis and review (Appellants’ Brief

p. 20). The regulation was finally issued over the vigorous

pr (tests of all the States in Volume 31 Fed. Reg. No. 16,

p. 1144, January 23, 1969 to be effective October 1, 1969.

>7. The Family Finance Corporation v. tfniadach, 37 Wis. 2d

163, 154 Northwest 2d 259, 269 dissenting opinion.

28. Appellants’ Brief, App. 1.

29. Jurisdictional Statement p. 7.

18

19

The delay can he attributed only to these objections and not

“ to allow those States where no such system existed to

adapt to the new procedures.”30

Every State participates in one or more of the aid pro

grams and every State is required by the Social Security

Act to establish, and has established, a fair hearing pro

cedure.

Heretofore and until October 1, 1969, (unless repealed or

revised), the HEW regulations authorized termination, sus

pension or withholding of aid prior to a fair hearing. For

example Section (>000 (k) o! the Federal Handbook pro

vides, “When the hearing decision is favorable to the claim

ant, or when the agency decides in favor of the claimant

prior to the hearing, the agency will make the correct d

'payments retroactively to the date the incorrect action was

taken.” (Emphasis added.)

Section 6300(g) reads in part, “ Insofar as may be applic

able, a decision in favor of the claimant applies retroactive

ly to the date the incorrect action was taken, and also ap

plies prospectively.” (Emphasis added.)

Section 6500 provides that Federal Financial Participa

tion is available in : “ (a) Payments made to carry out hear

ing decisions, or o take corrective action prior to the

hearing, including corrected payments retroactively to the-

date the incorrect administrat ive action was taken, (b) Pa \r-

ments of assistance continued pending a hearing decision.”

We do not accepi the apparent contention that HEW has

violated the Social Security Act in enacting the abo e

referred to regulations. Tf Congress had thought so it woii 1

have rectified IIEW’s “ erroneous” interpretation durin *

the course of its massive revisions of the Social Security A(

effective January ’2, 1967. (P.L. 90-248.)

30. Appellants’ Pi ief p. 26 n. 32.

20

Hi The Hearing Provided by the Regulation Meets the Hearing

Requirements of the California Welfare c .id Institutions Code

Authorizing the County to Cancel, Suspend or Revoke Aid

"For Cause".

t is contended by amicus curiae Legal Aid Society of

Alameda County that certain sections of the Welfare and

In -litutions Code require a hea ing prior !o the suspension

of aid inasmuch as said section authorizes the county to

suspend aid only “ for cause.” The sections referred to are

Welfare and Institutions Code sections- 12'JOO (O.A.S.);

12700 (Blind); 11458 (A FD C ); 10750 (Disabled). (Welf.

& Inst. Code §§ 12200-12202, App. IT, ] . 5.) We have no

quarrel with this contention with one exception; California

Welfare and Institutions Code section 12202 provides: “ If

at any time the [county] department has reason to believe

that aid lias been obtained improperly it shall cause an in

quiry to be made and may sus}>end payment of any install

ment pending the inquiry. . . .” (App. IT, p. G) (Emphasis

ad led.)

But more to the point herein, appellants’ right to an in-

foi mat hearing or conference with the county agency under

the regulation prior to suspension of aid and the right to

a formal hearing before the appellee-director of the State

D( partment of Social Welfare after suspension is precisely

the procedure the California Supreme Court found to be

re uired under the Vehicle Code in Ratliff v. Lampion, 32

C; 1. 2d 22G, 231-232 (1948), 195 P. 2d 792. In Ratliff the

co irt held that:

“Wien read together, these sections may be con

strued as providing for an investigation and hearing

conducted by the department which Avould afford the

licensee an opportunity to present evidence under the

rule in the Carroll and Steen cases. If the department

determined as a result of such investigation and hear

ing that good cause existed therefor, it might suspend

or revoke, but the order would not become effective

until 10 days after notice of the action taken. At any

time within GO days after such notice the licensee was

entitled to have the action of the department reviewed

in a more formal hearing before the director or his

representatives, in which the final decision was to be

made by the director. The action of the department in

suspending or revoking a license would not be stag 1,

however, by an application for a hearing, and the

order would become effective at the expiration of f le

10-dav period notwithstanding the pendency of a re

view by the director.” (Emphasis added; 32 Cal 2d

220, 231-2)

All that the court required in Ratliff v. Lampton, was “ a

prior opportunity to be heard . . . regardless of whet! or

there is right to administrative review,” (32 Cal. 2d at 230)

“which would afford the licensee an opportunity to present

evidence under the rule in the Carroll and Steen cases.” (i.d.

page 231). And what is the rule in these cases? In Steen

v. Board of Civil Service Commissioners, 26 Cal. 2d 71G;

1G0 p. 2d, 81G (1045) it should be noted the Civil Service

employee was already discharged or suspended without

any hearing. The Court’s concern was not the summary

suspension but the hearing before the Civil Service Com

mission to review that decision; the latter was much the

same as the function of the fair hearing under Welfare &

Institutions Code sections 10050, et seq. If the department

finds for the well ere recipient, the county is directed to

re-instate and reimburse the recipient. In Steen, the law

provided that the county employee may be reinstated by

the Civil Service board following an investigation bv the

board or the board may make an order sustaining the dis

charge. The full hearing required under Steen was before

the Civil Service Commission and followed the employee’s

suspension by the appointing power, i.e., the Department

of Water and Power. To (he same effect: See also LaPrade

21

v. Department of Water £ Potvi , 27 Cal. 2d 47 162 p. 2d 13

(1945); English v. City of Long Peach, 37 Cal. 2d 155 217

p. 2 1 22 (1950).

Ii Carroll v. California Hors Racing i oard, 16 Cal. 2d

164 05 p. 2d 110 (1940), conc< rning the revocation of a

hor. i trainer’s license, the court held that nee the statute

pro\ ided that no license may be revoked without just cause

the Legislature intended notice and hearing io enable the

licensee to appear and answer any charge or complaint

lodged against him. The court held that this necessarily

requires.a fair consideration of any evidence offered by

the accused licensee. CSS 44-325.43 requires that recipients

receive notice and may have a hearing to answer the charge

of ineligibility and that a fair consideration be given to

the evidence offered.

Amicus Curiaes’ statement (Br. 26) that “ Procedures

virtually identical to those provided by PSS 44-325.43 were,

as a practical matter, undoubtedly available in Ratliff also,

since the statute required 10 days not ice prior t o the revoca

tion of the' license” is no where substantiated in the decision.

The Department of Motor Vehicles had established no

procedures at all and maintained that it could take sum-

marv action. Further, the department contended that the

10 days notice of revocation was to give the licensee an

opportunity to arrange for his affairs, thus belying any

presumption that the department was willing to meet and

confer with the licensee. The court required a hearing but

held that the department hearing could be less formal than

the administrative hearing before the Director of the

Department.

Keenan v. San Francisco Unified School District, 34 Cal.

2d 708; 214 P.2d 382 (1950) is cited by Amicus Curiae (Br.

26) for the proposition that an informal interview with ad

ministrative officers “did not constitute a hearing contem

plated bv the statutes” hence the “ informal conference”

provided by the regulation is fatally defic ent. The informal

interviews Mrs. K< enan had with administrative officers of

the Board of Ednc ition which were held not to he the heat

ing contemplated by the ‘‘ for cause” provision of the

Education Code, did not purport to be a “hearing”. These

interviews were preliminary to the board’s formal action

dismissing her. “Mrs. Keen.au was not notified of the meet

ing and was not p esent. . . . It was stipulated at the ti'al

that she was not a orded a hearing.” 34 Cal. 2d at 711. rl he

court concluded “ i lat the cause relied upon by the school

authorities must > specified and a hearing afforded ic

the teacher to mee the charge.” Id. p. 715.

Subsequently, in Tucker v. San Francisco Unified Sch ol

District, 111 Cal. pp. 2d 87 . 880, 882 2-15 P.2d 597 (19; )

the court (in cons dering rules adopted by the Board f

Education follow n • the Keenan decision to implement d -

missal “ for cans* ’ of probationary teachers) stated that

“ dismissal for can; > onh obviously implies a hearing a id

finding of cai se” but then concluded (despite Amicus

Curiae’s assertion ; to the contrary), “neither did the

Keenan case o • any of the cases cited therein,31 determine

what is necessary o meet the requirment of notice and <

hear in y.” Id. 882. ( Imph isis added.)

Finally, Ratliff i either specifically nor impliedly rejecls

the appellee’s eonfintion thal the hearing required by the-

“ for cause” stain8 need be no more and could very well be

less than procidurd due process requii-es. Tn Ratliff ar l

Keenan the court ited thal I though the Constitution do< <

not require a hen. ing (he f.egislature could and had r ■

quired one in the statutes under consideration. It is f< ■

these statutorily impost d Inn rings that the court used tl '

fundamental due ; rocess requirements of notice and o]

31. Ratliff v. Lain it on, 32 (Ml. 2d 226; 195 I\2d 792 (1948.,

Carroll v. Californio torse liacintj Hoard, 16 Cal. 2d 164 (1940 ;

Covert v. State Board of Equalization, 29 Cal. 2d 125 173 P.2d 545

(1946).

23

2 -

po1 unity to ]>e heard. See Anderson Katunal Bank v.

Lvi < It, 3121 U.S. 233, 243, 24(1- 7 (1944). In Anderson this

Coi hold that the sufficiency the notice and hearing is

to i determined by consider!) the purpose of the proce-

dui . its effec-t on rights ass< ted and .11 otlier circum-

sta 'is which may render the roceedin^ appropriate, id.

p. 16.

Amicus Curiae is in error in tating that six months is

per nitted before a decision is rendered in a fair liearing

under Welfare & Institutions Code sections L0950 et seq.

(Bi 27). Effective July 1, 49(18, the Depa tment of Health,

Edi ation and Welfare, in est; dishing one of the require-

men s for state plans provide) that the decision must be

mat e within (iO days. Federal Handbook of Public Assist-

an Administration, Section (i300(.j) reads, ‘ ‘Prompt, de

fine ive and final administrative action will be taken within

60 lays from the date of the request for a fair hearing.”

In ompliance with IJEW’s n |uirement, appellee Mont-

goi ery adopted implementing regulations. In order to

maintain conformity with federal .requirements the Legis

lature has specifically provided that any statute “ shall be

come inoperative to the extent that it is not in conformity

with federal requirements.” (Welf. & Inst. Code § 11003.)

U ider the regulation the recipient is afforded prior ap-

pris I of the proposed action, the grounds therefor and

what information is needed from him. The recipient is

info med of the nature and ext at. of the information upon

win h the county has based its proposed action. lie is en

title! to be re]iresented by counsel to present his evidence

and an opportunity to meet with a County Welfare De

partment representative in order to discuss and, if possible,

resolve the question of eligibility. The county may with

hold aid payments only if it has substantial evidence of

probable ineligibility.

Amicus Curiae assert that (lie recipient is only afforded

an “ informal conference” thereby implying that such a

hearing ipso facto fails to meet the “ for cause” requir ment.

This is simply not true. The Federal HEW Regulati m re

lating to the full scale adjudicatory type fair hearing re

quires that even this last hearing he an informal one.

Section 0400(a) Federal Handbook of Public Assistance

Administration provides that the fair hearing “ is con

ducted in an informal raiher than formal court type pro

cedure in order to serve the best interests of the claimant,

however, the hearing is to be subject to (he requirements of

due process” (Emphasis added).

CO N CLU SIO N

The statutes and regulations involved together wi it the

policies and procedures evolved therefrom fully ; ccord

due process of law and any other constitutional safe,; lards

heretofore enunciated in the welfare context. That thi is so

has been demonstrated by the present brief and by ti lack

in opposing briefs of anv citation of authority deali g di

rectly with the matters which wore the subject of d< ision

by the court below.

die Court of Appeal of the State of California, First

A ipellate District, Division Three, on August 19, 1969,

is ued its decision in McCullough v. Terzian (1 Civil No.

2.' 330) reversing the judgment of the Superior Court and

r aching the same conclusion as the court below that the

c illenged procedures are constitutional. Heavy reliance

has been placed by appellants on the decision of the lower

court in McCullough, set out in full in the Jurisdictional

Statement, Appendix H. We desire to place 1he McCullough

appellate court decision before this Honorable Court and

to this end have added Appendix IV.

For the foregoing reasons, the judgment below should

be affirmed.

Dated: August 28, 1969.

Respectfully submitted,

26

r uomas M. O’Connor

City Attorney City and

County of San Francisco

1 vymond D. W illiamson,

Deputy City Attorney

Of Counsel

T homas C. Lynch

Attorney General

R ic h a r d L. M a y e r s

Deputy Attorney General

E lizabeth Palmer

Deputy Attorney General

6000 State Building

San France eo, California 94102

Telephone: 557-0266

Counsel for Appellees

(Appendices Follow)