Escambia County, FL v. McMillan Joint Appendix Vol. I

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1982

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Escambia County, FL v. McMillan Joint Appendix Vol. I, 1982. e4ac5ff9-b09a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/6d7c37ea-c0ac-497c-8194-e13e462e8466/escambia-county-fl-v-mcmillan-joint-appendix-vol-i. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

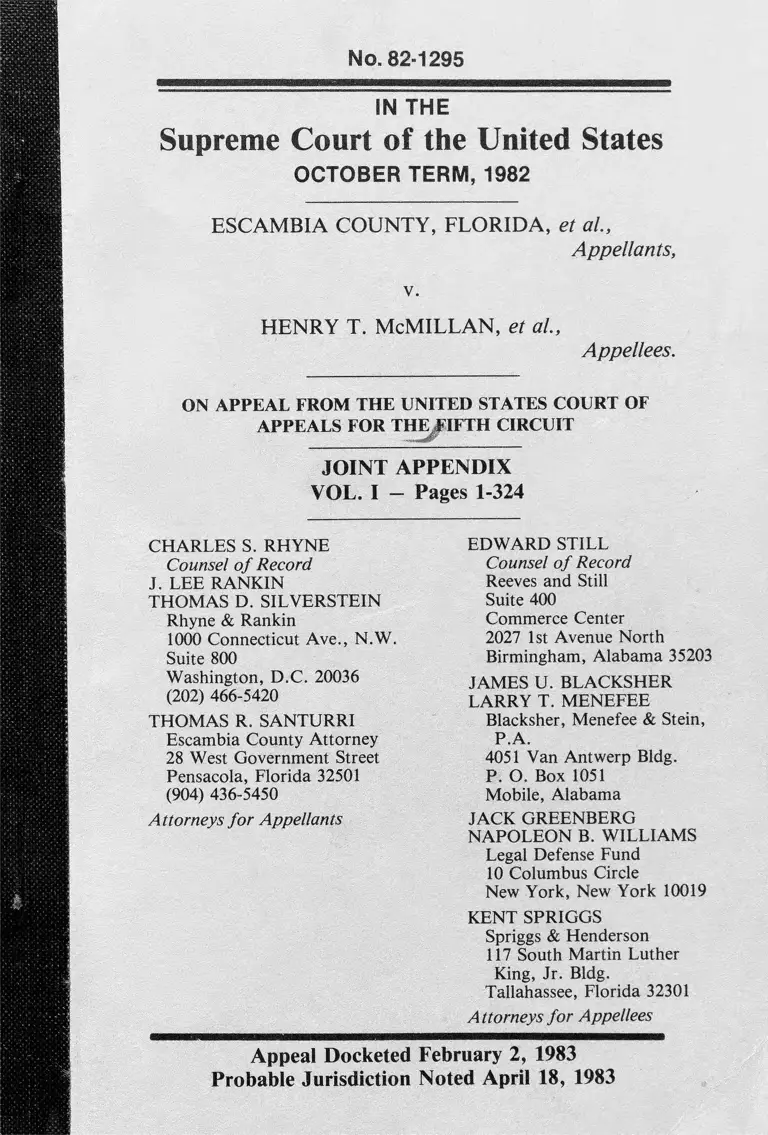

No. 82-1295

IN THE

Supreme Court of the United States

OCTO BER TERM, 1982

ESCAMBIA COUNTY, FLORIDA, et a l,

Appellants,

v.

HENRY T. McMILLAN, et al.,

Appellees.

ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES COURT OF

APPEALS FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

JOINT APPENDIX

VOL. I - Pages 1-324

CHARLES S. RHYNE

Counsel o f Record

J. LEE RANKIN

THOMAS D. SILVERSTEIN

Rhyne & Rankin

1000 Connecticut Ave., N.W.

Suite 800

Washington, D.C. 20036

(202) 466-5420

THOMAS R. SANTURRI

Escambia County Attorney

28 West Government Street

Pensacola, Florida 32501

(904) 436-5450

Attorneys for Appellants

EDWARD STILL

Counsel o f Record

Reeves and Still

Suite 400

Commerce Center

2027 1st Avenue North

Birmingham , Alabama 35203

JAMES U. BLACKSHER

LARRY T. MENEFEE

Blacksher, Menefee & Stein,

P.A.

4051 Van Antwerp Bldg.

P. O. Box 1051

Mobile, Alabama

JACK GREENBERG

NAPOLEON B. WILLIAMS

Legal Defense Fund

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

KENT SPRIGGS

Spriggs & Henderson

117 South Martin Luther

King, Jr. Bldg.

Tallahassee, Florida 32301

Attorneys for Appellees

Appeal Docketed February 2, 1983

Probable Jurisdiction Noted April 18, 1983

TABLE OF CONTENTS

VOLUME I

Page

Docket E ntries........................................................ ................ .................. 1

District C ourt................................................................................... 1

Court of Appeals ....................................................................................30

Complaint ........................................................................... 45

Answer and Affirmative Defenses — Escambia County ................... 52

Consolidation O rder......................................... 59

Arnow, C. J. Letter to Counsel of Record ..................... .................. .61

Pretrial Stipulation ......................................... 64

Pretrial Order.................... 77

Notice of Proposed County Charter ..................................................... 82

Excerpts of Trial Transcript................... .............. ............................... 146

Testimony of Dr. Jerrell H. Shofner ........................................ .. 146

Testimony of Dr. Glenn David C urry........................................ 229

Testimony of Charlie L. Taite ....................................................255

Testimony of Otha Leverette ............................................ 271

Testimony of Dr. Donald Spence .......... ................................... 280

Testimony of Billy Tennant ............................. .................. .. 310

VOLUME II

Testimony of Julian B anfell......................................... 325

Testimony of Orellia Benjamin Marshall ....................................334

Testimony of F. L. Henderson ..................... ...............................338

Testimony of Elmer Jenkins..................... ............................... 341

Testimony of Nathaniel Dedmond..................... ...................... .. 348

Testimony of James L. Brewer ........................... ...................... 357

Testimony of Cleveland McWilliams ....................................... .361

Testimony of Earl J. Crosswright ...... ..................................... .363

(0

Testimony of William H. Marshall ............................................ 374

Testimony of Dr. Charles L. Cottrell ........................................398

Testimony of James J. Reeves .................................................... 436

Testimony of Hollice T. W illiam s......................... .................... 438

Testimony of Governor Reubin A skew ............................... .. 452

Testimony of Marvin G. Beck .....................................................470

Testimony of Kenneth J. Kelson ................................................ 495

Testimony of Charles Deese, Jr.................................................... 507

Testimony of Jack Keeney ............................................ .............. 532

Testimony of A. J. B oland ............................. .............................549

Testimony of Laurence Green ......................... .......................... 560

Testimony of Dr. Manning J. D auer..........................................578

Colloquy Between the Court and Counsel ................................598

VOLUME III

Plaintiffs’ Exhibits......................................................................... .. 603

Exhibit 6 Demographic Tables — Pensacola Florida........... -603

Exhibit 8 Voter Registration, City of Pensacola....................731

Exhibit 14 Excerpts — Computer Printouts Analyzing

Voting Patterns for Selected Elections................... 733

Exhibit 16 Statistical Analysis of Racial Element in

Escambia County, Pensacola City Elections . . . . 771

Exhibit 17 Neighborhood Analysis, Pensacola SMSA ...........799

VOLUME IV

Exhibit 21 United Way of Escambia County, Inc. —

Community Planning Division Composite

Socio-Economic Index for the 40 Census

Tracts .............................................................................919

Exhibit 23 Excerpt — Statistical Profile of Pensacola

and the SMSA........................................................... 1006

Exhibit 25 Escambia County and Pensacola SMSA —

Population Trends; Racial Composition;

Population by Tract; Age Distribution.................. 1016

(ii)

(iii)

Exhibit 32 Selected Deeds Conveying Property Located

in Escambia County ........... ..................... • • ■ 1^36

Exhibit 33 Votes Cast for all Candidates in Selected

Precincts - September 1976 Primary ................1047

Exhibit 55 Materials Relating to the City of Pensacola:

Adoption of At-large Election System in 1959 .. 1052

Exhibit 66 County Boards and Committees . . . . . . . . . . . . 1106

Exhibit 70 Excerpt - 1976-77 Annual Budget of

Escambia .......................................1108

Exhibit 71 Summary Analysis (County Recreation) ......... 1111

Exhibit 73 Transcript of Proceedings of Escambia Coun

ty Board of County Commission at August

31, 1977 Public Hearing . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . H31

Exhibit 80 1973-77 Escambia County, City of Pensacola

EEO-4 Summary Job Classification and

Salary Analysis ............. . 1142

Exhibit 92 Letter Appearing in the Pensacola News Jour

nal, August 23, 1959 ......... ............................... 1152

Exhibit 95 Editorial Appearing in the Pensacola Journal,

August 13, 1959 .............................. 11^3

VOLUME V

Exhibit 98 Proposal of Charter Commission Appointed

in 1975 ........... 1155

Exhibit 99 Recommendations by Minority of Charter

Commission Appointed in 1975 . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1225

Exhibit 100 Proposal of Charter Commission Appointed

in 1977 ............................................................ 1228

(iv)

District Court Order Denying Stay of December 3, 1979

Remedial O rd er...................................... 1261

Excerpts o f Trial o f Testimony o f Dr. Glenn David

Curry......................................................................................................... 1267

Excerpts o f Trial Testimony of Dr. Manning F.

Dauer ............................................ 1284

NOTE

The following opinions, decisions, judgments, and orders have been

omitted in printing the Joint Appendix because they appear in the

Appendices to the Jurisdictional Statement as follows:

Page

Decision on Rehearing of the Fifth Circuit in

McMillan v. Escambia County, Florida, 688

F.2d 960 (5th Cir. 1982) ...................................... ........................... A -la

Decision o f the Fifth Circuit in McMillan v.

Escambia County, Florida, 638 F.2d 1239

(5th Cir. 1981) ........................................................................ ........ B-30a

Decision o f the Fifth Circuit in McMillan v.

Escambia County, Florida, 638 F.2d 1249

(5th Cir. 1981) ............................................................................ .... B-52a

Memorandum Decision and Order of the United

States District Court for the Northern District

of Florida in McMillan v. Escambia County,

Florida, PCA No. 77-0432 (N.D. Fla. Dec. 3, 1979) ............... B-54a

Memorandum Decision o f the United States District

Court o f the Northern District of Florida in

McMillan v. Escambia County, Florida

PCA No. 77-0432 (N.D. Fla., Sept. 24, 1979) . . . . . . . . . . . . . B-66a

Memorandum Decision and Judgment o f the United

States District Court of the Northern District

of Florida in McMillan v. Escambia County,

Florida, PCA No. 77-0432 (N.D. Fla. July 10, 1978) .............B-71a

(V)

Judgment in McMillan v. Escambia County,

Florida, 688 F.2d 960 (5th Cir. 1982)........... C-116a

DOCKET SHEETS

District Court

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF FLORIDA

PENSACOLA DIVISION

HENRY T. McMILLAN, ROBERT CRANE,

CHARLES L. SCOTT, WILLIAM F.

MAXWELL and CLIFFORD STOKES,

Plaintiffs,

vs.

ESCAMBIA COUNTY, FLORIDA; GERALD

WOOLARD, KENNETH KELSON, ZEARL

LANCASTER, JOHN E. FRENKEL, JR.,

MARVIN BECK, individually and in their

official capacities as members of the BOARD

OF COUNTY COMMISSIONERS OF

ESCAMBIA COUNTY; SCHOOL DISTRICT OF

ESCAMBIA COUNTY: THE SCHOOL

BOARD OF ESCAMBIA COUNTY: PETER

R. GIND, CAROL MARSHALL, RICHARD

LEEPER, LOIS SUAREZ, A.P. BELL, FRANK

BIASCO and JAMES BAILEY, individually

and in their capacities as members of the

ESCAMBIA COUNTY SCHOOL BOARD:

JOE OLDMIXON, individually and in his

official capacity as SUPERVISOR OF

ELECTIONS OF ESCAMBIA COUNTY

Defendants

Civil Action

No. 77-0432

FILED

Mar 18

OFFICE OF CLERK

U.S. DISTRICT CT.

NORTH DIST. FLA.

PENSACOLA,FLA.

CAUSE Suit in equity arising out of Constitution &

action for declaratory judgment under 28 USC

2201 & 2202

2

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT DOCKET

DC-III (REV. 1/75)

DATE NR PROCEEDINGS

3/18/77 1 Filed: 0 + 30 complaints (civil rights)

alleging violation of election laws of

Escambia County, Florida & seeking

declaratory judgment of enjoinment

from holding, supervising or certifying

results of elections for School Board &

County Commissioners & award of attys

fees and costs

3/18/77 Issued: 0 + 31 summons and del. same to

US Marshal w/30 copies of complaint &

USM/285 service forms on 3/21/77

3/18/77 Filed: Cert, of Good Standing from S/D

ALA for James U. Blacksher

3/18/77 Cert, of Good Standing from S/D ALA

for Larry T. Menefee

3/21/77 Mailed Rule 6 letter to all counsel for

Plfs./Rule 3 letter to NY attys JS-5

prepared

3/28/77 2 Filed: Summons & USM/285 showing

service on Escambia County, Florida by

serving Cindy Majewski, authorized

agent for Kenneth Kelson, Chairman of

Board of County Commissioners on

3/25/77

3/28/77 3 Filed: USM/285 showing service on

Board of County Commissioners of

Escambia County by serving Cindy Ma

jewski, authorized agent for Kenneth

Kelson, Chairman of Board on 3/25/77

3

3/28/77

3/28/77

3/28/77

3/28/77

3/28/77

4/11/77

4/11/77

4/11/77

3/ 28/77 4 Filed: USM/285 showing service on Ken

neth Kelson, individually, by serving

Cindy Majewski, authorized agent 'for

service on Kenneth Kelson, on 3/25/77

5 Filed: USM/285 showing service on Ken

neth Kelson, Board of County Commis

sioners of Escambia County, by serving

Cindy Majewski, authorized agent for

Kenneth Kelson, on 3/25/77

6 Filed: USM/285 showing service on

Marvin Beck, individually, by serving

Cindy Majewski authorized agent for

service on Marvin Beck, on 3/25/77

7 Filed: USM/285 showing service on

Marvin Beck, Board of County Commis

sioners of Escambia County, by serving

Cindy Majewski, authorized agent for

service on Marvin Beck, on 3/25/77

8 Filed: USM/285 showing personal serv

ice on Joe Oldmixon, individually, on

3/25/77

9 Filed: USM/285 showing personal serv

ice on Joe Oldmixon, Supervisor of Elec

tions for Escambia County, on 3/25/77

10 Filed: Motion & Stipulation for Exten

sion of Time for defts to file responsive

pleadings

11 Filed: Order of Judge Arnow giving

defts to 4/27/77 to file responsive

pleadings-copies to all counsel

12 Filed: 285 service form w/summons at

tached showing service on Charles

Dease, Bd. of Co. Comm, by serving

sec. Linda Scheuerman on 4/4/77

4

4/11/77 13 Filed: 285 service form w/summons at

tached showing service executed on

Charles Dease individually by his

secretary Linda Scheuermann on 4/4/77

4/11/77 14 Filed: 285 service form showing service

on Zearl Lancaster, Bd. of Co. Comm,

by executing on his secretary Carol Starr

on 4/4/77

4/11/77 15 Filed: 285 service form showing service

on Zearl Lancaster, individually by serv

ing his secretary Carol Starr on 4/4/77

4/11/77 16 Filed: 285 service form showing service

on Jack Kenney personally on 4/1/77 in

capacity as Co. Comm.

4/11/77 17 Filed: 285 service form showing personal

service on Jack Kenney, individually on

4/1

4/11/77 18 Filed: 285 service form showing personal

service on Lois Suarez as member of

School board on 3/31/77

4/11/77 19 Filed: 285 service form showing personal

service on Lois Suarez, individually on

3/31/77

4/11/77 20 Filed: 285 service form showing personal

service on Peter Gindl, individually on

3/3

4/11/77 21 Filed: 285 service form showing personal

service on Peter Gindl, member of

school board on 3/31/77

4/11/77 22 Filed: 285 service form showing personal

service on Carol Marshall on 3/31/77

4/11/77 23 Filed: 285 service form showing personal

service on Carol Marshall, member of

school board on 3/31/77

5

4/11/77 24 Filed: 285 service form showing personal

service on Charles Stokes, Supt. of

Schools for School Board of Escambia

County on 3/31/77

4/11/77 25 Filed: 285 service form showing service

on Dr. Floyd Dumas, Asst. Chairman of

Board, for School District of Escambia

County on 3/31/77

4/11/77 26 285 service form showing personal serv

ice on A.P. Bell, member of School Bd.

on 3/31/77

4/11/77 27 Filed: 285 service form showing personal

service on A.P. Bell, individually on

3/31/77

4/11/77 28 Filed: 285 service form showing personal

service on James Bailey, member of

School Board on 3/31/77

4/11/77 29 Filed: 285 service form showing personal

service on James Bailey, individually on

3/31/77

4/11/77 30 Filed: 285 service form showing service

on Richard Leeper, member of School

Bd. on 3/31/77

4/11/77 31 Filed: 285 service form showing service

on Richard Leeper individually on

3/31/77

4/11/77 32 Filed: 285 service form showing service

on Frank Biasco individually on 3/31/77

4/11/77 33 Filed: 285 service form showing service

on Frank Biasco, member of School

Board on 3/31/77

4/27/77 34 Filed: Answer & Affirmative Defenses of

Defendant School Board, et a! — Refer

red to Judge Arnow

6

4/28/77

5/18/77

5/18/77

5/18/77

5/18/77

5/18/77

5/18/77

4/ 27/77

5/18/77

35 Filed Answer & Affirmative Defenses of

Escambia County, et al — Referred to

Judge Arnow — PPT Requested

36 Filed: Notice of PPT set for 5/18/77 at

10:30 AM-copies to all counsel

37 Filed: Plaintiffs’ 1st interrogs. to deft

School Bd. chk

38 Filed Plaintiffs’ 1st request for prod, of

documents by deft Oldmixon. chk

39 Filed: Plaintiffs’ 1st interrogs. to deft

Oldmixon. chk

L.C. Notes of Hearings held from 10/30

- 11/30 — Order to be entered —

Discovery set for 8/18/77. Cases 77-0432

and 77-0433 are consolidated for

discovery purposes. Conditionally cer

tified as class action. Briefs due in 10

days on disputed areas.

40 Filed First Interrogatories propounded

by Deft School Board, et al

41 Filed: Order that cases consolidated for

disc, only w/disc to end 8/18/77; that

original of all depos filed on this case

w/copy filed in 77-0433; conditionally

certified class action w/members of class

being all black citizens of Escambia

County & City of Pensacola; memos due

5/30 on issue if State, Governor & Dept,

of State are indispensable parties;

whether case should proceed against

members of County Comm. School

Board & City Council in individual

capacities — copies to all counsel of

record

Supplemental class action allegation

prepared

7

5/20/77 42 Filed: Defts’ Escambia Co., County

Comm. & individual members of same.

Elect, supervisor & as individuals 1st in-

terrogs to plfs.

5/20/77 43 Filed: Plfs’ 1st request for production of

documents by School Bd. & individual

members thereof

5/27/77 44 Filed: Plfs’ memo brief concerning ques

tions raised at 1st pt conference —

REFERRED

5/27/77 45 Filed: Defts’ Memo of law in support of

county commissioners & supervisor of

election affirmative defenses — REFER

RED

5/31/77 46 Filed: Deft. School Board’s memo in

support of affirmative defenses —

REFERRED

6/3/77 47 Filed: Plfs’ 1st request for production by

County Commissioners

6/3/77 48 Filed: Plfs’ 1st interrogs to County Com

missioners

6/17/77 49 Filed Deft Oldmixon’s reply to Plfs’ 1st

request for Production of Docs.

6/20/77 50 Filed: Deft. School Board’s ans & obj. to

plfs’ 1st interrogs & memo in support of

same

6/21/77 51 Filed: Deft Oldmixon’s Answers, Ob

jections & Memo to Plfs’ 1st Interrogs to

Deft.

6/21/77 52 Filed: Response of Deft School Board, et

al to Plfs’ 1st Request for Production &

Brief in support of objections to produc

tion

8

6/24/77

6/28/77

7/1/77

7/8/77

7/15/77

7/20/77

7/22/77

7/26/77

7/28/77

6/ 24/77 53 Filed: Plfs’ 1st Interrogs to Deft City of

Pensacola

54 Filed: Plfs’ 1st Request for Production

of Documents by Deft. City of Pen

sacola

Received: Proposed Consent Discovery

Order - REFERRED TO JUDGE AR-

NOW

55 Filed: Answers & Objections of Plfs to

Defts’ first interrogatories

56 Filed: Defendant County Commis

sioners’ response to plfs’ 1st request for

prod.

57 Filed: Deft’s notice of taking depositions

of Henry McMillan, Robert Crane,

Charles Scott, Wm. Maxwell, Charles

Stokes, Elmer Jenkins, Woodrow

Cushon, Samuel Horton, Henry Burrell

& Bradley Seabrook on 7/20/77 &

7/21/77

58 Filed: Consent Discovery Order (Arnow,

CDJ) that deft Oldmixon may answer

plfs’ 1st Interogs. to deft. Oldmixon

when necessary by referring to

documents & said documents need not

be filed in Clerk’s office-copies to all

counsel

59 Filed: Second interrogatories propound

ed by Deft School Board, et al

60 Filed: Plfs; notice of taking Joseph

Mooney’s depo on 8/3/77 @ 9/30 AM

61 Filed: 2nd Interrogatories propounded

by Defts County & Supvsr of Elections

9

8/4/77 63

8/4/77 64

8/5/77 65

8/9/77 66

8/ 2/77 62

8/24/77 67

8/24/77 68

8/29/77 69

8/29/77 70

8/27/77 71

9/7/77 72

Filed: Joint motion to extend discovery

w/proposed order — REFERRED to

Judge Arnow

Filed: Copy of letter from Atty.

Blacksher to John Fleming that depo of

Mr. Moone has been re-set for 8/10/77

@ 9:30 AM

Filed: Order granting motion for exten.

of disc. — time extended to 11/19/77 &

same not to be further extended unless

motion file suff. in advance of 11/19/77

Filed: Copy of letter to all counsel from

judge re: adding add. parties

Filed: ORDER (ARNOW, CJ) The new

local rule 17, entitled Class Actions,

adopted by this court, is now adopted as

a rule applying to this case during the

period from the date of this order until

11/1/77 when such local rule becomes

effective & thereafter covers the conduct

of this & all other class action suits —

Copies to all counsel

Filed: Deposition of Woodrow Cushon

taken on 7/21/77

Filed: Deposition of Hollice T. Williams

taken on 8/2/77

Filed: Deposition of Samuel A. Horton

taken on 7/27/77

Filed: Deposition of Henry N. Burrell

taken on 7/27/77

Filed Deposition of Charles L. Scott

taken on 7/27/77

Filed: Depo of Robert P. Crane taken

7/25/77

10

9/9/77 73 Filed: Deft County Commissioners’

Answers, objections & memo to plfs’

first interrogatories to deft county com

missioners

9/9/77 74 Filed: Depo of William F. Maxwell

taken 7/25/77

9/12/77 75 Filed: Deft County Commissioners’

Answers, objections & memo to plfs’

first interrogatories w/Commissioner

Lancaster’s signature

9/19/77 76 Filed: Depo of Henry McMillan

9/19/77 77 Filed: Depo of Bradley M. Seabrook

9/22/77 78 Filed: Deposition of Clifford Stokes

9/29/77 79 Filed: Deposition of Joseph K. Mooney

10/5/77 81 Filed: Deposition of Frank A. Faison

10/5/77 81 Filed: Notice of Deposition of Peter R.

Gindl on 10/25/77

10/5/77 82 Filed: Notice of Deposition of Kenneth

Kelson on 10/24/77

10/12/77 83 Filed: Plfs’ answer and obj. to deft.

School Board’s 2nd interrogs

10/12/77 84 Filed: Plfs’ ans. & obj. to deft. County

Commissioner’s and Super, of Elections’

2nd interrogs

10/12/77 85 Filed: Depo of Elmer Jenkins taken

7/21/77

10/19/77 86 Filed: Notice of filing verbatim

transcript of statements made by & to

Deft Board of County Commissioners &

atty during public hearing held 8/31/77

11/10/77 87 Filed: Deposition of Henry T. McMillan

& Robert Paul Crane taken on 7/20/77

11

11/18/77 88 Filed: Deft, Escambia County — Motion

to extend time for discovery — REFER

RED as EMERGENCY

12/1/77 89 Filed: Notice of Continuation of taking

of deposition of Henry T. McMillan.

12/2/77 90 Filed: Clerk’s Notice — Deft Escambia

County Motion to extend discovery —

GRANTED copies to all counsel —

Discovery ext. to 1/6/78

12/12/77 91 Filed: Continuation of deposition of

Henry McMillan on 12/6/77

12/15/77 92 Filed: Transcript of a portion of meeting

of Bd of Co. Commissioners held

12/8/77.

12/19/77 93 Filed: Transcript of School Board

meeting of 10/13/77

1/10/78 94 Filed: Plfs’ Motion & brief for order

authorizing certain communications

with class members — & Hearing set,

handed to L.C.

1/10/78 95 Filed: ORDER extending discovery to

3/10/78 — Copies to all counsel

1/16/78 96 Filed: Ltr from Atty Charles S. Rhyne

re: change of address

1/20/78 97 Filed: Deft. County Comm, response to

motion for order authorizing com

munications w/class members

1/23/78 98 Filed: Defts; School District, School

Board, Gindl, Marshall, Leeper, Suarez,

Bell, Biasco & Bailey’s reply memo in op-

po to motion for order authorizing com

munications with class

12

1/30/78

2/1/78

2/8/78

2/14/78

2/14/78

2/23/78

2/23/78

1/ 25/78 99 Filed: Defts County Commissioners’

supplemental answer to plfs interrogs

100 Filed: Ltr from Louis F. Ray, Jr. to

Judge Arnow re: School Board

Transcript

101 Filed: Deft. County’s notice of taking

depos of Drs. C ottrell, Curry,

McGovern and Shofner on 2/27 & 28

w/copy of letter to Atty Blacksher at

tached

102 Filed: Notice of hearing on motion &

other matters pertaining to communica

tions of class members set 2/22/78 at

3:00 PM — copies to all counsel

103 Filed: Plfs’ motion and memo for order

authorizing Dr. Chas Cotrell to inter

view members of class

104 Filed: County’s respns to plfs’ informal

disc, request for 1977 EEO-4 reports

105 Filed: ORDER (ARNOW, CJ) Deft, Dr.

Frank Biasco w/i 15 days (3/10/78) will

serve memo of law respecting motion &

plfs have 15 days after service to serve

response — copies to all counsel

106 Filed: ORDER (ARNOW, CJ) re com

munications w/class members; counsel

shall maintain a list of all class members

they communicate with & shall

periodically file in this court such lists,

under seal, to be held in camera, w/such

lists to be filed at the end of each month,

commencing w/3/78. Names on such list

will not be divulged except pursuant to

order of competent court — copies to all

counsel

13

2/23/78 107 Filed: Clerk’s Notice — Pits’ Motion for

order authorizing Dr. Cotrell to conduct

interviews w/members of class —

DENIED as moot, in view of order

entered this date — copies to all counsel

2/23/78 108 Filed: Deft County Commissioners’ sup

plemental answers to plfs’ interrogs

2/23/78 109 Filed: Ltr from Atty Ray to Judge Ar-

now dtd 1/31/78 re: Dr. Biasco

3/1/78 110 Filed: Plfs’ Motion for extension of time

for conducting discovery — REFER

RED

3/6/78 111 Filed: Letter to Judge from Atty.

Blacksher w/proposed form letter seek

ing funds from class members attached

for approval by court — REFERRED

3/7/78 112 Filed: Memo of law in support of pet. of

deft Dr. Biaso for approval of proposed

public statement

3/10/78 113 Filed: Clerk’s Notice — Proposed form

letter from plfs approved w/correction

— copies to all counsel w/copy of ap

proved letter attached

3/13/78 114 Filed: Clerk”s Notice — Motion to ext.

disc. GRANTED - Disc, ends 3/20/78

— copies to all counsel

3/13/78 Rule 3C letter to all counsel

3/21/78 115 Filed: Order setting PT Conf — set

4/21/78 @ 9 AM w/papers due 4/14 —

copies to all counsel of record

3/24/78 116 Filed: Order modifying paragraph (B) of

order setting PT Conf so that parties

meet by 4/10 rather than by 4/3 —

copies to counsel of record

14

3/30/78 117 Filed: ORDER approving Dr. Biasco

statement permissable under Local Rule

17(B) copies to all counsel

4/3/78 118 Filed: List of class members contacted

by plfs’ counsel - FILED SEALED AS

PER ORDER OF COURT

4/1/78 119 Filed: Defts’ MSJ & memo in support of

same

4/12/78 120 Filed: Amended PT Order — PT set

5/31/78; PT Papers due 5/15/78; trial

tent, set 7/5-7/78 & 7/17-21/78 -

copies to all counsel

4/13/78 121 Filed: 2nd amend, order for PT — set

5/4/78 @ 10 AM w/papers due 4/26 &

trial set 5/15/78 — copies all counsel

4/25/77 122 Filed: Notice of appearance of add.

counsel for plfs — Rule 5 letter written

4/25/77 123 Filed: County’s motion for ext. to file

PT papers from 4/26 to 5/1 — REFER

RED

4/25/77 124 Filed: County’s memo in support of mo

tion to extend time to file PT papers

4/25/77 125 Filed: Deposition of Kenneth Shofner

taken on 3/2/78

4/25/77 126 Filed: Deposition of James McGovern

taken on 3/2/78

4/26/78 127 Filed: PT Stipulation

4/27/78 128 Filed: Cy ltr from Judge Arnow to

Counsel re: compliance W /PT Order

5/1/78 129 Filed: Plfs motion to allow deposing of

defts’ expert witnesses — REFERRED

15

5/1/78 130 Filed: Plfs’ notice of taking depos of Dr.

Dauer, Dr. Morris, Dr. Horton 5/8/78

5/1/78 131 Filed Plfs’ PT proposed findings of fact

& conclusion of law — REFERRED

5/1/78 132 Filed: Plfs’ PT brief & oppo to defts’

MSJs - REFERRED

5/1/78 133 Filed: Deft’ Trial Brief — REFERRED

5/1/78 134 Filed: Deft School Board 2nd amend

ment to deft’s potential witness list

5/1/78 135 Filed: Deft School Board 1st amendment

to potential witness list

5/1/78 136 Filed: Deft County Commissioners &

Supervisor of Elections exhibit list

5/1/78 137 Filed: Defts’ Proposed findings of facts

& conclusions of law — REFERRED

5/4/78 138 Filed: Cert, of Good Standing from

ND/Ala for W.E. Still, Jr.

5/8/78 139 Filed: Notes of PT Conf; plfs prior to

trial to file stip re: para. F5 of the PT

stip; memo re: obj. to exhibits due by

5/12 & PT order due 5/12

5/8/78 140 Filed: Copy of letter from Judge to all

counsel re: conduct of trial.

5/8/78 141 Filed: Third Amendment to Deft School

Bd’s potentional witness list.

5/11/78 142 Filed: First Amendment to Deft County

Commissioners and Supervisor of Elec

tions’ potential witness list.

5/12/78 143 Filed: Deft memo in oppo to admissibili

ty of newspaper articles — REFERRED

5/12/78 144 Filed: Amendment to Plfs’ Witness List

- REFERRED by handing to L.C.

5/12/78 145 Filed: File Memo of authorities concern

ing admission of newspaper articles —

REFERRED by handing to L.C.

5/12/78 146 Filed: PRE-TRIAL ORDER — copies to

all counsel

5/12/78 147 Filed: Deft Cty Cmms & Svsr Elect.

Memo in opp. to admissibility of ex

hibits of Plfs - REFERRED to handing

to L.C.

5/12/78 148 Filed: Stipulation pursuant to PT Order

filed 5/12/78 - REFERRED by hand

ing to L.C

5/15/78 149 Filed: Deposition of Doctor Manning

Dauer taken 5/8/78

5/15/78 150 Filed: Deposition of Doctor Michael

Horton taken 5/8/78

5/15/78 151 Filed: Deposition of Honorable M.C.

Blanchard taken 5/8/78

5/17/78 152 Filed: Deposition of Peter R. Gindl, Sr.

taken 8/2/77

5/18/78 153 Filed: Deposition of Dr. Charles Cottrell

5/23/78 154 Filed: Memo of law of deft. School

Board

5/15/78 Proceeding before Judge Arnow for

non-jury trial — to continue 5/16

5/16/78 Cont. of N-J trial - to cont.

5/17/78 Cont. of N-J trial — to cont.

5/18/78 Cont. of N-J trial — to cont.

5/21/78 Cont. of N-J trial - to cont.

5/22/78 Cont. of N-J trial — to cont.

5/23/78 Cont. of N-J trial — to cont.

5/24/78 Cont. of N-J trial — to cont.

5/25/78 Cont. of N-J trial - to cont - both

sides rest @ 11:40 AM - parties to file

briefs in 10 days — 5/5/78

5/30/78 155 Filed: Transcript of trial testimony of

Dr. Charles L. Cotrell

6/1/78 156 Filed: Transcript of trial testimony of

Dr. Manning J. Dauer

6/5/78 157 Filed: Trial Testimony of William H.

Marshall

6/5/78 158 Filed: Defts County & School Board’s

post trial memo w/copy of same —

REFERRED

6/6/78 159 Filed: Plfs’ post-trial proposed findings

of fact & conclusions of law — REFER

RED

6/6/78 160 Filed: Copy ltr from Atty Blacksher to

defts counsel re: Plfs’ Post trial brief

6/12/78 161 Filed: Defts’ motion to file post-trial

memo response to plfs’ post-trial brief

w/memo in support attached —

REFERRED

7/3/78 162 Filed: Sealed envelope containing those

class members with whom attorneys for

the plaintiffs in this cause and in 77-0433

discussed these cases during the period

through 6/30/78.

18

7/7/78

7/7/78

7/10/78

7/10/78

7/10/78

7/ 7/78

7/10/78

7/11/78

7/11/78

163 Filed: Plfs’ sealed list of class members

as per order

164 Filed: Defts’ application for stay and in

junction pending appeal

165 Filed: Defts’ memo in support of ap

plication for stay & injunction & propos

ed order — REFERRED

166 Filed: School Board’s consent to entry of

order granting application for stay and

injunction pend, appeal

167 Filed: Memorandum decision — copies

del. & mailed to all counsel of record

168 Filed: Judgment in favor of plfs and

against defts & taxing costs against defts;

that parties to submit proposals for dilu

tion remedy in 45 days; that remedial

systems approved and adopted not to be

effective for primary & general elections

in 1978 but will be effective in 1980; re

taining jurisdiction of matter & that an

immediate appeal may materially ad

vance ultimate decision of litigation —

copies either del. or mailed to all

counsel; recorded in COB #21, Pgs 14

& 15

JS-6 prepared

169 Filed: Order that defts’ application for

stay of elections pend, final determina

tion DENIED — copies to all counsel &

recorded in COB #21, Pgs. 17-19

170 Filed: Order that County Commissioners

motion to substitute #34 exhibit with

copy of same — GRANTED — copies to

all counsel

19

7/14/78 171 Filed: Cy ltr to John Suda re: transcript

of case

7/18/78 172 Filed: Plfs’ motion to alter or amend

judgment

7/18/78 173 Filed: Brief in support of plfs’ motion to

alter or amend judgment

7/31/78 174 Filed: Opposition to plaintiffs motion to

alter or amend judgment. Referred.

8/8/78 175 Filed: ORDER — Plfs motion to amend

or alter judgment is denied w/o pre

judice — copies to all counsel

8/9/78 176 Filed: Notice of Appeal by Deft Carol

Ann Marshall

8/9/78 177 Filed: Notice of Appeal by Defts Escam

bia County, et al.

8/24/78 178 Filed: County’s proposed election plan

8/24/78 178 Filed: School Board’s proposed election

plan

8/24/78 179 Filed: County’s amendment to election

plan

8/24/78 180 Filed: School Board’s proposed election

plan

8/25/78 181 Filed: Plaintiffs’ submission of distric

ting plan for the County Commission

and School Board. Referred.

8/28/78 182 Filed: Cy ltr from Atty Fleming to

Counsel re: transcript

8/29/78 183 Filed: Cy ltr from Judge Arnow to All

Counsel re: Hearing (status) 9/25/78 at

9:00 AM w /ltr from Grady H. Albritton

dtd 8/29/78

20

9/13/78

9/14/78

9/15/78

9/19/78

9/22/78

10/5/78

9/ 7/78

10/10/78

10/17/78

10/18/78

10/18/78

10/19/78

184 Filed: Plfs’ amendment of districting

plan for the county commission & school

board - REFERRED

185 Filed: Request for extension of time for

transmission of record on appeal —

REFERRED

Request for ext. of time for trans. of

record-on-appeal stamped GRANTED

— copies to all counsel, court reporter

& cert copy to USCA-5th Cir.

186 Filed: Defts’ memo in support of submit

ted electoral plans — REFERRED

187 Filed: Plfs’ memo concerning proposed

remedies — REFERRED

188 Filed: Notice of adoption of ordinance

amending election plan. Referred.

189 Filed: Memorandum (WEA) w/trans.

ltr to all counsel — memos due re:

charter commission & School Board

Governing Authority w/plfs responding

w/i one wk after (10/10/78) - hearing

set 11/21/78 at 2:00 PM (evidentiary)

190 Filed: Deft School Board’s Amendment

to deft’s memo in support of submitted

electoral plans — REFERRED

191 Filed: Plfs’ reply to deft School Board’s

Amended memorandum — REFERRED

192 Filed: Cy ltr from Atty Blacksher to

Judge Arnow re: Charter Commission

process

193 Filed: Cy ltr from Atty Fleming to

Judge Arnow re: Charter Commission

Filed: Transcript of Non-Jury Trial (9

volumes)

21

11/7/78 Record-on-Appeal mailed to USCA-5th

Circuit — copies of dockets w/trans. Itr

to all counsel — cc: Judge Arnow &

John Suda — Exhibits to be mailed by

Appellants

11/7/78 194 Filed: Cy Itr from Atty Lott to Clerk,

USCA-5th Circ. re: motion to expedite

appeal

11/7/78 195 Filed: Cy Itr from Atty Fleming re:

docketing fee

11/29/78 196 Filed: Copy Itr from Judge Arnow to

Mr. Oldmixon

12/5/78 197 Filed: Notice of substitution of parties

— substituting John E. Frankel, Jr. for

Jack Kenney as County Commissioner

2/5/79 Judge’s Memo to refer back in ten days

(2/15/79)

2/13/79 198 Filed: Deft County’s Offer of Judgment

for legal services

2/15/79 199 Filed: Defts’ memorandum regarding

preclearance remedy

2/20/79 200 Filed: CONSENT ORDER w/respect of

plfs’ attys’ fees to be paid by deft School

Bd Judgment entered in favor of plfs &

against deft School Board in the amount

of $48,000.00 in full satis, of plfs’ claims

for attys’ fees to 12/31/78 — Pending

resolution of appeal the above amount

shall be placed in a certificate of deposit

or some other interest-bearing account

w/periodic int. realized to be made

payable to plfs’ attys’, etc. — This judg

ment shall have no effect upon & shall be

entered w/o prejudice to plfs’ claims for

22

2/20/79

2/27/79

2/27/79

2/27/79

3/5/79

3/12/79

attys’ fees against Deft School Board &

members w/respect to work performed

after 12/31/78 & against all other defts

in this & the companion 77-0433 —

copies to all counsel

201 Filed: Memorandum decision concern-

regarding preclearance remedy

202 Filed: School Board’s suggestion of par

ties - REFERRED

203 Filed: Memorandum decision concern

ing remedial plan — copies to counsel

204 Filed: Order in accordance w/memo

decision — re-apportioned to 5 single

member districts as prescribed in plan

filed 8/24/78 as attached w/map; at next

primary & general election in 1980,

board to be reduced from 7 to 5

members; those members elected in 1980

from districts 1, 2 & 3 to serve 2 year

terms and those elected from 4 & 5 shall

serve 4 years and thereafter, all members

to be elected for 4 year terms; after each

federal decennial census, districts to be

re-apportioned; enjoining County

School district, school board, individual

members, supervisor of elections, from

failing to redistrict as set out, holding

elections as redistricted; retaining

jurisdiction for 5 years — copies to

counsel of record — recorded in COB

#21, Pg 16-19

205 Filed: Consent ORDER W/respect to

plfs’ attys’ fees to be paid by Deft Escam

bia County — copies to all counsel

206 Filed: AMENDED CONSENT ORDER

23

3/29/79

4/20/79

4/27/79

5/15/79

7/5/79

3/17/79

w/respect of Plfs’ attys’ fees to be paid

by Deft Escambia County — Judgment

entered for Plfs & against Deft Escambia

County in amount of $49,729.00 in full

satisfaction of attys fees & costs up to &

including 12/31/78, plus simple int. at

8% per annum beginning 4/1/79,

entered on consent of parties & entered

w/o prejudice to plfs’ claims for fees

after 12/31/78 in this & 77-0433, provid

ed no claim for attys fees or costs shall

be allowed against Deft Joe Oldmixon —

copies to all counsel

207 Filed: Deft School Board Member Sam

Forester’s Notice of Appeal — cert, copy

to USCA 5th Circuit w/cert. copy

docket sheets cc: all counsel & Deft SB

Member

208 Filed: Cy ltr from Court Reporter to

Mr. Forester re: Transcript

209 Filed: Motion to withdraw appeal —

REFERRED

Court Reporter Notes: Box 43 Col. 2, 3,

4, 5, 6

Deft Sam Forester’s Motion to withdraw

appeal stamped “GRANTED - The

court being advised this appeal has not

yet been docketed.” — copies of motion

w/endorsement to all counsel & School

Board Member Sam Forester & USCA-5

Cir.

210 Filed: Notice of proposed county charter

211 Filed: Plfs motion and memo for ten

tative approval of proposed charter

reapportion plan

24

9/21/79

9/24/79

3/ 17/79

11/9/79

11/29/79

1/29/79

11/29/79

12/ 3/79

212 Filed: Clerk’s notice of hearing on mo

tion for tentative approval of proposed

charter reapportionment plan — set

9/8/79 @ 9 AM — copies to counsel of

record

Hearing held from 2 — 3:15 PM order to

be entered on county plan and charter

plan

213 Filed: Memo decision — giving tentative

approval as suggested by the parties, to

the reapportionment plan contained in

the proposed County Charter to be sub

mitted to the referendum election

11/6/79; such approval is subject to the

condition that the single member district

boundaries subsequently drawn by reap

portionment commission, if charter is

approved, to be submitted to the court

for review and approval as adequate

remedy for the present racially

discriminatory election system — copies

to counsel of record

Letter from Judge to all counsel setting

hearing on 11/26/79 re: voting plan

214 Filed: Escambia County’s memo in sup

port of preserving incumbency pending

remedial redistricting — handed to L.C.

215 Filed: Notice of substitution of parties

— Woolard for Deese-County Commis

sion

216 Filed: Plfs’ memo re: preserving in

cumbency — handed to L.C.

217 Filed: Memo decision on County Com

missioners reapportionment — copies to

counsel

25

12/ 3/79

1/3/80

1/3/80

1/ 18/80

218 Filed: Order (WEA) on memo decision

that County Commissioners to be reap

portioned to 5 single-member districts

w/boundaries to conform to those

adopted in 2/27/79 order w/description

appended to order; at next primary &

general elections in 1980 single-member

districts will be elected but jurisdiction is

retained to alter date of elections on mo

tion; to preserve staggered terms, com

missioners from Dist. 1, 2 & 3 shall serve

4-year terms & those elected from Dist. 4

& 5 to serve 2 yrs initially, but 4 yrs

thereafter; after publication of decennial

census, districts shall be reapportioned

to comply w/one-person, one-vote re

quirements; that County Commis

sioners, individually & in official

capacities & Supervisor of Elections,

their successors, agents, etc. are enjoined

from failing to redistrict & reapportion

& to hold elections as redistricted; retain

ing jurisdiction for 5 yrs. unless changed

for further orders as necessary copies to

counsel, recorded in COB #21, Pgs 239

to 243

219 Filed: Escambia County’s Notice of Ap

peal (Rec’d w/o filing & docket fees

1/2/80)

Trans 1th to USCA w/cert. copy notice

of appeal & docket sheets — cc: all

counsel of record

Court Reporter Notes: Box 49 Col. V-H.

1-26-79, 9-25-78

Record-on-appeal mailed to USCA cc:

all counsel of record

26

1/23/80 220 Filed: Motion of Deft Escambia County

for stay of 12/3/79 Order of Elections

w/memo

2/6/80 221 Filed: Notice of hearing on motion for

stay set 2/15/80 at 10: AM — copies to

all counsel

2/7/80 222 Filed: Plfs’ memo opposing defts’ ap

plication for stay of elections

2/15/80 223 Filed: ORDER (WEA) denying deft

County’s Motion for stay of elections —

copies to all counsel

2/26/80 224 Filed: Notice of Appeal by Deft County

2/26/80 Record on appeal consisting of Docu

ments #220 - 224 mailed to USCA — cc:

all counsel of record

3/23/81 225 County’s stip. that Patricia D. Wheeler

be substituted as counsel for the county

in place of Richard I. Lott

3/23/81 226 County’s entry of appearance of Patricia

D. Wheeler as counsel for Escambia

County

4/13/81 227 ORDER (USCA) Denying plfs’ motion

for restoration of USDC injunctions

8/17/81 228 MOTION for the payment of attorney’s

fees and costs with respect to issues con

cerning school board

8/31/81 229 Consent Order (WEA) re: plfs’ attys’ fees

to be paid by shool board — copies to

counsel of record

11/16/81 230 JUDGMENT issued as a mandate

affirming District Court Judgment —

REFERRED

27

12/22/81 231 Plfs’ motion and brief for award of attys’

fees and costs w/affidavits

12/28/81 232 Amended motion for award of attys’ fees

and costs w/exhibit attached

1/5/82 233 Deft Marshall’s response to plfs’ motion

and brief for award of attys’ fees and

costs

2/5/82 234 Notice of hearing set for 2/25/82 at

11:00 am-copy to all counsel

2/25/82 235 ORDER (WEA) Setting case for eviden

tiary hearing 3/29/82 at 9: AM — 1 day

— copies to all counsel

3/3/82 236 STIPULATION of w/drawal of counsel

3/3/82 237 APPEARANCE of Paula G. Drum

mond as atty for Escambia County

3/8/82 238 MOTION for production of documents

under Rule 34 by Marshall

3/8/82 239 MOTION to shorten time to respond to

motion for production of documents —

REFERRED

3/9/82 240 AMENDMENT to Deft Marshall’s

response to plfs’ motion & brief for

award of attys’ fees & costs & MOTION

to deny same & hearing thereon

3/9/82 241 NOTICE of deposition of Carol Ann

Marshall on 3/19/82

3/10/81 242 ORDER (WEA) GRANTING deft Carol

Ann Marshall’s motion to shorten time

from 30 to 14 days for plfs to respond to

deft’s motion for production of docu

ments. — copy to all counsel

28

3/23/82

3/25/82

3/25/82

3/25/82

3/26/82

5/14/82

5/24/82

3/22/82

6/ 7/82

243 PLFS’ RESPONSE to deft Marshall’s

motion for production of documents —

REFERRED

244 Deft. Marshall’s motion for hearing &

decisions prior to evid. hearing set

3/29/82 & for reasonable delay of evid.

hearing on attys’ work & expense —

REFERRED

245 Plfs’ letter-memo In support of motion

for atty’s fees & costs awarded jointly &

severally - REFERRED

246 Plfs’ letter-memo in oppo to deft. Mar

shall’s motion of 3/23/82 — REFER

RED

247 Plfs’ motion to have County held jointly

& severally liable for attys fees & cost

248 DEPOSITION of Carol Ann Marshall

taken 3/19/82

249 JOINT MOTION to approve consent

judgment w/proposed judgment —

REFERRED

250 Consent Judgment — plfs motion for at

tys fees & costs against Carol Ann Mar

shall is settled & dismissed; plfs claim for

attys fees & costs against Escambia

County dismissed w/out prejudice;

Carol Ann Marshall to pay plf $8,000

for a claims for fees & costs; all other

motions pend, with regard to fees &

costs withdrawn — copies to counsel of

record

251 D eft. School Bd’s m otion for

preclearance of school board member

residence areas & memo in support

29

6/17/82 252 Plfs obj. to preclearance — REFERRED

6/17/82 253 Plfs letter-memo in support of objec

tions to preclearance

7/1/82 254 ORDER (WEA) conditionally approving

pre-clearance of School Board Election

District copies to counsel

7/6/82 255 Deft. School Bd’s cert copy of RESOLU

TION revising districts - REFERRED

Wea

7/6/82 256 Civil subpoenas showing svc on Jim C.

Bailey on 7/1/82

30

Court of Appeals

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 78-3507

HENRY T. McMILLAN, e t a l .,

Plain tiffs-Appellees,

versus

ESCAMBIA COUNTY, FLORIDA, ET AL.,

Defendants-Appellants.

* * * * *

ELMER JENKINS, ET AL.,

versus

CITY OF PENSACOLA, ET AL.,

(Consolidated with 79-1633 & 80-5011. Defendants-

Appellants.

FILED 8/9/78

Judge Winston E. Arnow

Docket Number CA 77-0432 & CA 77-0433

(Consolidated in D.C.)

APPEARANCE

DATE NR ATTORNEYS FOR APPELLANT

FOR ESCAMBIA COUNTY:

12/6/78 Richard Y. Lott, County Att., 23 West

Government Street, Pensacola, Florida

32501

12/6/78 John W. Flemming -do- (904) 432-8374

4/10/81 Patricia D. Wheeler -do- (904) 436-5450

(out of case)

31

12/6/78

12/6/78

12/6/78

12/6/78

3/26/79

3/26/79

12/7/78

1-10-29

12-7-78

12/8/28

3/1/82 Paula G. Drummond -do-

FOR SCHOOL BOARD

RAY, PATTERSON & K1EVIT, 226

Palafox Street, Pensacola, Florida 32501

FOR ALL DEFENDANTS:

Charles S. Rhyne, 1000 Connecticut

Ave., N.W., Suite 800, Washington,

D.C. 20036.

William S. Rhyne -do-

Donald A. Carr (out of the case)

For CITY OF PENSACOLA:

Don J. Canton, City Att., Pensacola, FL

(904) 436-4320

ATTORNEYS FOR APPELLEES

J. U. Blacksher, Mobile, AL 36601 (205)

433-2000

Larry Menefee -do-

CRAWFORD, BLACKSHER, FIG

URES & BROWN, 1407 Davis Ave.,

Mobile, Al. 36603

J. U. Blacksher -do- (205) 432-1681

Kent Springs, 324 West College Ave.,

T allahasee, F lorida 32301 (904)

224-87-01

Jack Greenberg, 10 Columbus Circle,

Suite 2030, New York, New York 10010

(212-586-8397)

Eric Schnapper, -do-

Edward Still, Suite 400, Commerce

Center, 2027 1st Ave., N., B’hm, AL

35203 (205-322-6631)

Refer Panel to City of Mobile v. Bolden

in U.S. Supreme Court #77-1844 - 5th

Circuit #12

32

7/31/79 Cons, w/79-1633 after this was screened

xxxxxxxxxxx 79-1633 was classed IV

automatically, xxxx

7/6/83 Call Betty Killan xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

rehearing ruled (904) 433-0004.

8/23/82 Craig Pittman — 800-342-2263 Pen

sacola Journal, also call Pittman when

rehearing is ruled on.

1. Record, Exhibits and Brief Information

11/14/78 Record on Appeal

11/14/78 Exhibits

12/26/78 Brief for Appellants (City of Pensacola, et al.)

12/26/78 Brief for Appellants (County of Escambia, et

al.)

3/2/79 Brief for Appellees

3/19/79 Reply Brief for Appellants (City of Pensacola,

et al.)

6/16/80 Supp. Brief for Appellants (J)

5/12/80 Supp. Brief for Appellees (J)

7/23/82 Supp. Brief for Appellees (Ed to Pit. former

5th Cir. Judges

7/23/82 Supp. Brief for Appellees (E’d to Pit. former

5th Cir. Judges

12/26/78 Record Excerpts

3-19-79 Reply Br. for Appellants (County of Escam

bia, et al) 5-9

4. Extension Fig. Motion for:

1-26-79 Appelle’s Brief Ext. to 2-25-79

33

5. Calendar Information

2-14-80 Case assigned for 3-26-80 in EB

Hearing Panel: JPC-Peck-PAK

3-26-80 Case Argued □ by Appellant □ by Appellee

6. Opinioni Information

2-19-81 *Opinion Rendered

PAK Aff. in Pt. Rev. in Pt.

*Issd in xxxxx signed

Printed opinion distributed 3-9-81 p. 4317

7. Rehearing Information

3-2-81 Sub. 3/8/81 PAK

4-3-81 Petition for Rehearing (P) (J) □ Appellee □

Reg. □ Suggestion En Banc

10-8-82 xxxxxx for Rehearing (P) on the Rehearing

Opinion □ Appellant □ En Banc

11-04-82 Order Denying Rehearing of 10-08-82

9-24-82 □ Opinion also filed in 80-5011

8. Motions

4-9-79 Consolidate Appeals W/79-1633, clerk BNS

dated 4-17-79.

2-21-79 Leave to File Brief in Excess Pgs. 70 pages

Court GBT filed 2-2-79

5-12-80 Leave to File Supp. Brief RCV 5-12-80

3-2-81 Stay of Mandate (CofP). Response filed by

3-10-81 sub 3/10/81, Granted. Court Clerk,

PAK. Dated 3-12-81.

11-16-82 Stayg Mot. (Appellant) Response filed by Ap

pellee’s. Dated 11-18-82. Court Clerk, PAK.

Dated 11-23-82.

34

9. Other Docket Entries

12/6/78 Fig. Notice of appellants, Escambia County

11/30/79

and members of its Board of County Commis

sioners for substitution of parties. (SEND TO

SCREENING JUDGE).

Fig. Appellants Notice of substitution of par

ties. (SEND TO PANEL)

12/7/79 Fig. Appellant’s Application for Expedited

consideration of Merits appeal.

12/10/79 Fig. Appellee’s response in support of motion

to expedite appeal.

12/18/79 Fig. Appellee’s Supp. Authority. (Send to

Panel)

12/26/79 Fig. Order GRANTING appellants’ motion to

expedite the appeal.

2-13-80 Fig. Appellees’ supp. authority. (SEND TO

PANEL) (also fid. 79-1633)

3-10-80 Fig. Order granting motion for stay of

remedial election pendente lite and further

ordering that this appeal be consolidated for

argument and disposition with Nos. 79-1633

and 80-5011 (JPC, JWP & PAK) (also filed in

Nos. 79-1633 and 80-5011)

(Cont.’d)

10. Judgment or Mandate Information

10-23-81 Jdgt. as Mdt. Issd. to Clerk (as to Jenkins)

11-12-81 Jdg. as Mdt. to Clerk (as to McMillan &

Escambia, School Board

12-10-82 Record on Appeal Retd, to Clerk (29 volume)

12-10-82 Exhibits Retd, to Clerk 4 boxes

11-23-82 Mandate Isd. to Clerk

Mandate Stayed to Order (3-12-81)

35

11. Supreme Court Information No. 80-1946

5-28-81 Notice of Fig. of Cert. Pet. on 5-19-81

9-17-81 Notice of dismissal of petition f/certiorari in

SC 9/11/81.

12-6-82 Notice of Mot. for Stay - Denied 12/2/82

2-15-83 Notice of fid. An Appeal on 2/2/83

9. Other Docket Entries (Con’t)

4-29-80 Fig. Appellants, City of Pensacola & Escam-

5/21/80

bia, et al., supp. authority, (CE) (Also filed

Nos. 79-1633 and 80-5011).

Fig. Appellees’ letter dt. 5/20/80 replying to

ct.’s letter of 5/16/80 regarding fig. of an addi

tional brief, (also fid. in Nos. 78-3507 &

79-1633) (C.E.).

10/28/80 Fig. Appellees’ letter dt. 10/21/80 calling Ct.’s

attn. to attached brief filed by U.S. in case No.

78-3241. (CE)

11-12-80 Fig. appellants’ letter of 11-5-80 as supp.

authority. (CE)

11-24-80 Fig. appellants’ Supp. Authority. (C.E.) regard

ing each local government sub. 3/10/81

PAK). Petition for rehearing and en banc,

(sub 3/11/81 PAK)

3-12-81 Fig. Order GRANTING issuance of separate

mandates for each of the governmental defend

ants in 78-3507. (SEE ORDER IN FILE) Fur

ther ORDERING Stay of mandate pending the

filing and disposition of a jurisdictional stmt

on appeal to the S.C. (PAL)

4-2-81 Fig. Appellees’ motion for restoration of in

junctions.

36

4-7-81 Fig. City of Pensacola opposition to Plaintiffs’

motion for restoration of injunction, (sub

4/7/81 PAK)

4-10-81 Fig. motion of Appellees’ for issuance of

mandate in 78-3507 to the school board. Sub

PAK 4/27/81

4- 27-81 Fig. motion of Appellees’ for issuance of

mandate in 78-3507 as to the school board.

Sub PAK 4/27/81

4/28/81 Fig. Order DENYING appellees’ motion for

issuance of the mandate as to the school

board. (PAK)

5- 11-81 Fig. Appellee, City of Pensacola Notice of Ap

peal to the U.S. Supreme Court. LTR xxxxx

9- 10-81 Fig. Joint motion for issuance of the mandate

in 78-3507 Sub PAK

9/29/81 Fig. order DENYING Joint Motion for is

suance of the mandate in 78-5307.

10/1/81 Fig. motion of Phillip M. Waltrip to In

tervene. (Sub. PAK 10/6/81)

10- 5-81 Fig. joint motion for issuance of mandate in

78-3507 and 79-1633

10- 9-81 Fig. Appellees MEMORANDUM In Support

of Motion f/issuance of the mandate & Sup

porting Motion f/Immediate Remand.

11- 3-81 Fig. JOINT MOTION F/Issuance of Mandate

as to the School Board w/MEMORANDUM.

Sub. PAK 11/8/81.

11-12-81 Fig. Order GRANTING joint motion for is

suance of the mandate as to the Escambia

County School Board. (PAK)

37

11-12-81

12-14-81

3-1-82

3-1-82

3/8/82

7/27/82

10- 29-82

11- 8-82

11-04-82

11/12/82

11/12/82

11/12/82

11/16/82

Fig. Order DENYING motion of Phillip M.

Waltrip to intervene (COLEMAN, PAK,

PECK)

Fig. Phillip M. W altrip’s REQUEST

f/Clarification. Sub xxxx 12/18/81

Fig. appellant’s STIPULATION ^Substitu

tion of Counsel.

Fig. appellant’s LETTER re Elections-CE.

Fig. order DENYING Waltrip’s request for

clarification of the Court’s order of 12/14/81.

(PAK)

Fig. appellee’s MOTION To Dissolve Stay of

Elections. Sub JCG

Fig. appellees MOTION To Dissolve Stay Of

Elections.

Fig. appellants’ OPPOSITION To The Ap

pellees’ Motion To Dissolve Stay of Elections.

Fig. order denying motion of State Associa

tion of County Commissioners for leave to file

amicus curiae brief in support for rehearing en

banc. (PAK).

Fig. appellee’s letter in response to appellant’s

opposition to appellees’ motion to dissolve

stay of elections. (Sub. supp. 11/15 Unit A&B)

Fig. motion of Sumter County for leave to

file amicus curiae brief in support for rehear

ing en banc.

Fig. motion of Hendry County Board of Com

missioners for leave to file brief as amicus

curiae in support of for rehearing en banc.

Fig. motion of Seminole County, FI for leave

to file amicus curiae brief in support of for

rehearing en banc of appellants.

38

11/16/82

11/16/82

11/18/82

11/23/82

11/23/82

11/23/82

11/23/82

11/23/82

11/24/82

4/20/83

Fig. motion of appellants for stay of mandate

pending to Supreme Court. (Sec. 3. 8) Sub.

PAK

Fig. motion of Citrus County for leave to file

amicus curiae brief in support of petition for

rehearing en banc of appellants.

Fig. response of appellees to appellants motion

for stay of mandate. (Sub. PAK 11/18/82)

Fig. order DENYING motion of Sumter

County for leave to file amicus curiae in sup

port of the suggestion of en banc. (PAK) (bh)

Fig. order DENYING motion of Hendry

County, Fla., for leave to file amicus curiae in

support of the suggestion en banc. (PAK) (bh)

Fig. order DENYING motion of Seminole

County, FLA for leave to filed amicus curiae

in support of the suggestion en banc. (PAK)

(bh)

Fig. order DENYING of Citrus County for

leave to file amicus curiae in support of sug

gestion en banc. (PAK) (bh)

Fig. order DENYING motion of Escambia

County, et al. for a stay of the mandate pend

ing application for review to the United

States Supreme Court. (COLEMAN, PECK,

PAK)

Fig. order DENIED AS MOOT the appellees’

motion to dissolve stay elections (PAK)

Fig. order of the Supreme Court noting prob

able jurisdiction.

39

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 80-5011

HENRY T. McMILLAN, e t a l .,

Plain tiffs-Appellees,

versus

ESCAMBIA COUNTY, FLORIDA, ET AL.,

Defen dan ts-Appel lants.

(Consolidated with 79-1633 & 78-3507)

Cross Appeal No. 80-51 SOX

FILED 1/3/80 (Escambia, et al.) 2-26-80 (Escambia, et al.)

Judge Winston E. Arnow

Docket Number PCA 77-0432

Location of Hearing EB

Date of Hearing 3-26-80

Hearing Panel JPC-Peck-PAK

Hon. John W. Peck

Senior Circuit Judge

613 U.S. Courthouse

APPEARANCE

DATE C-

O -

DE ATTORNEYS FOR APPELLANT

FOR ESCAMBIA COUNTY:

1/11/80 Richard Y. Lott, County Att., 23 West

Government Street, Pensacola, Florida

32501

40

4/10/80 Patricia D. Wheeler, County Atty

-do-(904) 436-5450

3/4/82 Paula G. Drummond -do-

3/26/80 RHYNE & RHYNE, William S. Rhyne,

1000 Connecticut Ave., N.W., Suite 800,

1/14/80 Washington, D.C. 20036 202/466-5420

Charles S. Rhyne -do-

1/14/80

ATTORNEYS FOR APPELLEE

BLACKSHER, MENEFEE & STEIN,

P.A., P. O. Box 1051, Mobile, Alabama

35601 (205) 433-2000

1/14/80 KENT SPRIGGS, 324 W. College Ave.,

Tallahassee, FL 32301 (904) 224-8701

JACK GREENBERG, Suite 2030, 10

Columbus Cir., N.Y., N.Y. 10019

1-16-80 EDWARD STILL, Suite 400, Com

merce Center, 2027 First Ave., North,

B irm in g h am , A lab am a 35203

205/322-6631-7479

xxxxxx See 78-3507, 79-163

1. Record, Exhibits and Brief Information

1-21-80 Record on Appeal

3-4-80 Supp. Record

2-15-80 Brief for Appellants

3-18-80 Brief for Appellees

7-23-82 Supp. Brief for Appellants CE’d to All Former

Fifth Judges

7-23-82 Supp. Brief for Appellee CE’d to All Former

Fifth Judges

2-15-80 Record Excerpts

41

2. Miscellaneous Filings

1/7/80 (E) Dup. Notice of Appeal and Clerk’s State

ment of Docket Entries

* * *

5. Calendar Information

3-10-80 Case Assigned for 3-26-80 in EB

Hearing Panel: JPC-Peck-PAKZ

3-26-80 Case Argued □ by Appellant □ by Appellee

6. Opinion Information

2-19-81 *Opinion Rendered, PAK

*issd. in typewritten form

Printed opinion distributed 3-19-81 p. 4329

7. Rehearing Information

3-3-81 Mot. for Ext. - Ext. to 4-4-81 PAK

4-3-81 Petition for Rehearing (P) (CJ) □ Ap

pellee □ Reg. □ Suggestion En Banc

10-8-82 Suggestion for Rehearing (P) On the Rehear

ing Opinion also fed. 78-3507.

10-22-82 Order denying Reh. of 04/03/81

11-04-82 Order Denying Rehearing of 10-08-82

9-24-82 Opinion S9. Also filed in 78-3507 issued in

typewritten form pp 15704

8. Motions

2-15-80 Consolidate Appeals 78-3507 & 79-1633 Ap

pellees. Dated 2-25-80, 3-10-80

11-16-82 Stay of Mandate (Appellants) Appellees

11-18-82 PAK Court Clerk. Dated 11-23-82

42

9. Other Docket Entries

1- 14-80 Fig. Appellant’s Notice of Issues on Appeal.

(Send to Screening Judge)

2- 26-80 Fig. Appellants’ Application for Stay of

Remedial election order pendente lite, etc. (sub

2-26-80 JRC)

2/29/80 Fig. Appellees’ opposition to appellants’ ap

plication for stay of elections.

3- 10-80 Fig. Order granting Appellant’s Motion for

Stay of Remedial Election Pendente Lite, and

further ordering that this appeal be con

solidated with Nos. 79-3507 and 79-1633 (JPC,

JWP & PAK) (also filed in Nos. 78-3507 and

80-5011)

4- 29-80 Fig. Appellants, City of Pensacola & Escam

bia, et al., supp.authority. (CE) (Also filed

5/21/80 78-3507, 80-5011).

5/21/80 Fig. Appellees’ letter dtd. 5/20/80 replying to

court’s letter of 5/16/80 regarding the filing of

an additional brief, (also filed in #68-3507 &

79-1633) (C.E.).

(Continued)

10. Judgment or Mandate Information

3-2-81 Bill of Costs

10- 23-81 Jdgt. as Mdt. Issd. to Clerk S9 (3-5-81) (as to

Jenkins)

11- 23-82 Jdgt. as Mdt. to Clerk

12- 10-82 Record on Appeal Retd, to Clerk (2 vols)

43

11. Supreme Court Information No. 82-1295

12-6-82 Not. of Mot. for Stay “Denied” 12-2-82

2- 15-83 Not of fig. an appeal on 2-2-83

9. Other Docket Entries (Con’t)

9-12-80 Fig. appellee’s supplemental authority (Also

filed in 79-1633)

11-12-80 Fig. A ppellant’s letter of 11-5-80 as

supp.authority. (CE)

3- 11-81 Fig. Appellees’ amended motion to extend

time for filing petition for rehearing and en

banc. (Sub 3/11/82 FAK)

3-12-81 Fig. O rder G R A N TIN G ap p ellees ,

McMILLAN, et al. ext. time to April 4, 1981

in which to file pet. for rehearing & suggestion

en banc. (See Order in File). (PAK)

3-1-82 Fig. appellant’s LETTER re Election-CE.

9- 24-82 Fig. opinion GRANTING appellees’ petition

for rehearing (regular) and VACATING opi

nion of 2-19-81; AFFIRMED and REMAND

ED (PAK) (SIGNED).

10- 19-82 Fig. State Association of County Commis

sioner’s MOTION F/Leave To File Amicus

Curiae Brief in support of petition f/rehear-

ing.

10- 29-82 Fig. appellees’ MOTION To Dissolve Stay of

Elections. Sub.

11- 8-82 Fig. appellant’s OPPOSITION To The Ap

pellees’ Motion To Dissolve Stay of Elections.

11-04-82 Fig. order denying motion of State Associa

tion of County Commissioners for leave to file

amicus curiae brief in support of suggestion

for rehearing en banc. (PAK).

44

11/12/82

11/12/82

11-12-82

11/16/82

11/16/82

11/16/82

11/18/82

11/23/82

11/23/82

Fig. appellee’s letter in response to appellant’s

opposition to appellees’ motion to dissolve

stay of elections. (Sub. xxxxxxxx)

Fig. motion of Sumter County for leave to file

amicus curiae brief in support of for rehearing

en banc.

Fig. motion of Flendry County Board of Com

missions for leave to file brief in support of for

rehearing en banc.

Fig. motion of Seminole County, Florida, for

leave to file amicus curiae brief in support of

petition for rehearing en banc of appellants.

Fig. motion of appellants for stay of mandate

pending See S. 8 (Sub PAK 11/18/82)

Fig. motion of Citrus County for leave to file

amicus curiae brief in support of for rehearing

en banc of appellants.

Fig. appellees response to appellants motion

for stay of mandate. (SUB. PAK 11/18/82.)

Fig. order DENYING motion of Sumter

County for leave to file amicus curiae in sup

port of the suggestion of en banc. (PAK) (bh)

Fig. order DENYING motion of Hendry

County, FLA, for leave to file amicus curiae in

support of the suggestion en banc. (Pak) (bh)

45

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF FLORIDA

PENSACOLA DIVISION

HENRY T. McMILLAN, ROBERT CRANE, :

CHARLES L. SCOTT, WILLIAM F. :

MAXWELL and CLIFFORD STOKES, :

Plaintiffs, :

vs. :

ESCAMBIA COUNTY, FLORIDA; GERALD

WOOLARD, KENNETH KELSON, ZEARL

LANCASTER, JACK KENNEY, MARVIN

BECK, individually and in their official

capacities as members of the BOARD OF

COUNTY COMMISSIONERS OF

ESCAMBIA COUNTY; SCHOOL DISTRICT

OF ESCAMBIA COUNTY: THE SCHOOL

BOARD OF ESCAMBIA COUNTY;

PETER R. GINDL, CAROL MARSHALL,

RICHARD LEEPER, LOIS SUAREZ, A.P.

BELL, FRANK BIASCO and JAMES BAILEY,

individually and in their official capacities

as members of the ESCAMBIA COUNTY

SCHOOL BOARD: JOE OLDMIXON

individually and in his official capacity

as SUPERVISOR OF ELECTIONS FOR

ESCAMBIA COUNTY

Defendants.

FILED

MAR 18

3.45 PM 1977

OFFICE OF CLERK

U.S. DISTRICT CT.

NORTH DIST. FLA.

PENSACOLA, FLA.

COMPLAINT

I.

Jurisdiction

Jurisdiction of this Court is invoked pursuant to 28

U.S.C. §§ 1331 and 1343. The amount in controversy ex

ceeds $10,000.00 exclusive of interest and costs. This is a

suit in equity arising out of the Constitution of the United

46

States; the First, Thirteenth, Fourteenth and Fifteenth

Amendments, and 42 U.S.C. §§ 1973 and 1983. This is

also an action for declaratory judgment under the provi

sions of 28 U.S.C. §§ 2201 and 2202.

II.

Class Action

Plaintiffs bring this action on their own behalf and on

behalf of all other persons similarly situated pursuant to

Rule 23(a) and 23(b)(2), Federal Rules of Civil Procedure.

The class which plaintiffs represent is composed of all

black citizens of Escambia County, Florida. All such per

sons have been, are being, and will adversely be affected by

the defendants’ practices complained of herein. The class

constitutes an identifiable social and political minority in

the community who have suffered and are suffering in

vidious discrimination. There are common questions of

law and fact affecting the rights of the members of this

class who are and continue to be deprived of the equal pro

tection of the laws because of the election system detailed

below. These persons are so numerous that joinder of all

members is impracticable. There are questions of law and

fact common to plaintiffs and the class they represent. The

interests of said class are fairly and adequately represented

by the named plaintiffs. The defendants have acted or

refused to act on grounds generally applicable to the class,

thereby making appropriate final injunctive relief and cor

responding declaratory relief with respect to the class as a

whole.

47

III.

Plaintiffs

A. Plaintiffs Henry T. McMillan and Robert Crane

are black citizens of Escambia County, over the age of

twenty-one years, who live within the City of Pensacola.

B. Plaintiffs Charles L. Scott, William F. Maxwell and

Clifford Stokes are black citizens of Escambia County,

over the age of twenty-one years, who live in unincor

porated areas of Escambia County, Florida.

IV.

Defendants

A. Escambia County is a political subdivision of the

State of Florida. The Board of County Commissioners ex

ercises general legislative, executive and administrative

powers for Escambia County.

B. Charles Dease, Kenneth Kelson, Zearl Lancaster,

Jack Kenney and Marvin Beck are the duly elected Com

missioners of Escambia County.

C. The School Board of Escambia County is the

supervisory and administrative body charged with

conducting the affairs of the School District of Escambia

County

D. Peter R. Gindl, Carol Marshall, Richard Leeper,

Lois Suarez, A.P. Bell, Frank Biasco and James Bailey are

the duly elected members of the School Board of Escam

bia County.

E. Joe Oldmixon is the Supervisor of Elections for

Escambia County.

48

V.

A. Escambia County is governed by a five-member

County Commission. The Commissioners are elected at-

large by the qualified voters of the County for five residen

cy districts. The partisan election uses numbered places

with a majority vote/run-off requirement. The Commis

sioners serve for four-year staggered term s.

B. The School Board of Escambia County is com

posed of seven members. Five of the members must reside

in one of five residency districts and two may reside

anywhere in the County. The candidates run for numbered

places, non partisan elections which have majority

vote/run-off requirements. The members serve for four-

year staggered terms. The members are elected at large by

the qualified voters of Escambia County.

C. Escambia County has a population of 205,334, ac

cording to the 1970 Census, of which 40,362 or 19.7% are

black. The major urbanized area is in and around the City

of Pensacola, which has 59,509 people within the cor

porate limits. There is a substantial degree of residential

racial segregation. 43% of the black citizens of Escambia

County reside in five census tracts having greater than

80% black population.

D. All of the present officeholders for the School

Board and County Commission are white. There has

never been a black citizen elected to either the School

Board or County Commission. Qualified black citizens

have sought elections to both the School Board and Coun

ty Commission, but all have been defeated in elections

characterized by racially polarized voting. The following

black citizens have unsuccessfully sought election to the

School Board: Mr. Elmer Jenkins in 1976 and Mr. O.

Leverette in 1970. The following black citizens have un

successfully sought election to the County Commission:

49

Mr. John Reed, Jr., in 1966 and 1970 and Mr. Nathaniel

Dedmond in 1970. The following black citizens have un

successfully sought election to the County Commission:

Mr. John Reed, Jr., in 1966 and 1970 and Mr. Nathaniel

Dedmond in 1970. The futility of blacks gaining seats on

the County Commission and School Board is a major bar

rier in recruiting qualified black citizens to run for these

public offices.

E. The present at-large election systems for both the

School Board and County Commission, employing

numbered places and a majority vote/run-off require

ment, operate in Escambia County to discriminate against

black residents of the County in that their voting strength

is diluted or minimized by the white majority.

F. Black citizens in Escambia County have been sub

jected to official discrimination directly in the exercise of

the franchise through devices such as the poll tax and

white primary. Additionally, other forms of official

discrimination, such as denial of equal access to educa

tional opportunities, combine to preclude blacks from ef

fectively participating in the election process.

G. The County Commission has historically been less

responsive to the needs of the black citizens than they are

to the needs of the white citizens. Black neighborhoods

have received a proportionatelly smaller share of county

services. The School Board has also been less responsive to

the needs of the black citizens than to the needs of the

white citizens. A segregated school system was maintained

until the School Board was ordered by the federal court to

desegregate. This continued policy of being less responsive

to the needs and rights of black citizens has forced the

black community repeatedly to return to the federal courts

for protection of their rights.

H. As a direct result of these and other factors, the at-

large systems of electing members of the Board of County

50

Commissioners and School Board of Escambia County, as

designed and/or presently operated, deny plaintiffs and

the class of black citizens they represent equal access to the

political process leading to nomination and election to the

County Commission and School Board and, with respect

to said black citizens, are fundamentally unfair, all in

violation of their rights protected by the First, Thirteenth

and Fifteenth Amendments to the Constitution of the

United States; both the Due Process and Equal Protection

Clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment; the Voting Rights

Act of 1965, 42 U.S.C. § 1973; and the Civil Rights Act of

1871, 42 U.S.C. § 1983.

VI.

Plaintiffs and the class they represent have no plain,

adequate or complete remedy at law to redress the wrongs

alleged herein, and this suit for a permanent injunction is

their only means of securing adequate relief. Plaintiffs and

the class they represent are now suffering and will con

tinue to suffer irreparable injury from the unconstitu

tional election system described herein.

WHEREFORE, plaintiffs respectfully pray this Court

to advance this case on the docket, order a speedy hearing