A Sham and a Shame Draft Memorandum

Reports

January 1, 1981

63 pages

Cite this item

-

Division of Legal Information and Community Service, DLICS Reports. A Sham and a Shame Draft Memorandum, 1981. d71f1037-799b-ef11-8a69-6045bdfe0091. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/6d869ae4-6b9d-4677-95b1-e6050f8a7e08/a-sham-and-a-shame-draft-memorandum. Accessed February 20, 2026.

Copied!

D R A F T

M E M 0 R A N D U M

TO: Jack Greenberg

Julius Chambers

FROM: Jean Fairfax

RE: "A SHAM AND A SHAME"

December 3, 1981

Anticipated Impact on Black Children of th.e Reagan

Administration's Actions, Policies and Proposals in

the Area of Education

The full impact of Reagan's agenda will not be known until he

submits his budget to Congress in January, until Departments of

Education, Justice and Agriculture file the results of the regu-

latory .revisions that are currently in process and, really, until

school opens next fall, when the cumulative impact of budget

cuts, phased-out programs, new regulations, and the shift to

local control will become apparent. The purpose of this memo

is to report my assessment of developments as of early December

1981. It reflects consultations with representatives of nation-

al organizations that are close to the issues and with Federal

officials, and my review of the Omnibus Reconcilation Act and

other materials.

I. GENERAL FINDINGS

A. The number of black school children "at risk" will

increase substantially. One cannot review their

plight in school in isolation from the totality of

Reagan's approach to the problems of the poor. (I am

indebted to Bob Greenstein, Project on Food Assistance

and Poverty for most of the following.)

- 2 -

1,. Reagan's "safety net" for the "truly needy"

is no safety net at all for the majority o~

poor families in America. Social Security,

Medicare and veterans programs, most of whose

beneficiaries are not America's neediest,

altogether receive 95 % of the dollars appro-·

priated to Reagan's safety net programs.

87 % of Social Security and 86 % of Medicare

recipients are above the poverty line.

More than half the dollars in the seven

programs benefit persons with incomes that

are at least double the poverty level. Only

5% of the Federal outlays for these seven

·are for programs ·that primarily benefit the

poor. Nearly two-thirds· of the Americans below

the poverty line either receive no benefits

from any of the safety-net programs or at

most only free school meals. The real

safety net programs which are vital to

survival of the truly needy, such as food

stamps, Aid to Families with Dependent Children,

Medicaid, and rent subsidies, are victims of

Reagan's sharpest cuts, the cumulative im-

pact ~f which will be disastrous.

As "substantial parts" of the Great Society

programs are "heaved overboard," to quote

David Stockman, millions of American will be

cast adrift.

,

- 3 .....

2. In 1980, 31.8 million Americans had incomes below

the poverty line ($8,414 for a nonfarm family of

four) and the number is expected to rise. The

increase between 1979 and 1980 was "one of the

largest increases in poverty sin ce we started com

piling statistics in the early 1960's," commented

a Census Bureau official. The Administration has

admitted that unemployment will rise. However,

unemployment compensation will decrease. 1 million

unemployed workers in FY 1982 and an additional

70,000 in FY 1983 will lose 13 weeks of extended

unemployment benefits as a result of restrictions

in coverage mandated by the Omnibus Budget Recon

ciliation Act (OBRA) • The termination of a ll .

public service jobs will increase the ·ranks of

the unemployed. 94 % of these jobs wer.t to the

economically disadvantaged; one- f ourth to youths

under 22 and nearly one-half to low-income women.

The alarmingly high unemployment rate of black

women who are heads of families is a major factor

in the increased numbers of the black poor and

especially black poor children. More than half

of all black children live in female-headed

households; three fifths of such families are

poor:.

3. Poor · and marginal income families will encounter

more difficulties in qualifying for welfare,

f

- 4 -

will not be able to rely upon receiving it

promptly and regularly, and benefits will be

lower. OBRA mandated about twenty changes in

AFDC eligibility requirements and benefits

that will result in a reduction of about

·$1.7 billion in combined Federal and state

benefits to recipients. Some of the changes,

that were effective October 1981, are: a

limit of $1,000 on allowable resources;

limit of AFDC to families with gross incomes

at or below 150 % of the states' standard

of needs. ( 41 states have a standard of

need well below the poverty line. 21.9 %

of nonwhite female-headed households liv-

ing at 100-149% would lose 15% of their

benefits); states may now treat as income

the value of benefits received from food

stamps or housing subsidies; the dis

allowance of benefits to families where

a caretaker relative is on strike at the

end of the month; the restriction of

"dependent" children to those under 17;

the limitation of AFDC-Unemployment

eligibility to those families where the

"principal" earner is unemployed with

the entire family ineligible if the

principal earner is not registered for

- 5 -

work or training. The treatment of working

welfare mothers is particularly harsh. Wel

fare mothers who work will bear nearly half

of all AFDC cuts, although they are only

about one-seventh of mothers on welfare.

After four months of work, AFDC mothers

with three children will lose all AFDC

benefits as follows - in 36 states, if they

earn $5,000; in three states if they earn

as little as $1,750.

According to a recent New York Times article

reporting the findings of a study entitled

"Impact of the Reagan Administration's Pro

posed Budget Cuts on Adolescent Pregnancy

Program":

*Teen-agers account for 17 percent

of all pregnancies and 14 percent

of all births in the city. They

face increased risks of complica

tions and mortality. 90 percent

of teen-age mothers drop out of

school.

*Teen-agers are now facing cuts in

vital educational, vocational coun

seling, medical and recreational

services - the very serv ices that

could give them a more affirmative

sense of the future and reasons to

- 6 -

defer parenthood.

*2,027 pregnant teen-agers and adolescent

parents and 11,793 children will be

denied services unless the city or state

replaces decreased funds in the Maternal

and Child Health Block Grant.

*15,545 teen-agers will be denied family

planning services as funds are reduced

in Title X of the Public Health Act.

*New York City faces a reduction in

the $165,000 it received last year

through the Vocational Education Act

for the education of pregnant students

and parents and $35,000 for day care.

More than half of the mothers and

children in that program would be

eliminated.

4. Poor and marginal families will hav e less dis

posable income, inasmuch as a larger proportion

of their income will necessarily h ave to be

allocated to survival:

a. For housing . The lack of affordable

housing is a major problem f or t he

poor. 47 % of female-headed house-

holds cannot secure housing at 25 % of

their income. Most low-income f amilies

do not receive housing assistance now,

and OBRA cut housing assis t ance programs

- 7 -

by one-third. OBRA also raised rents

over the next five years for tenants

in subsidized housing to 30% of their

income. The median annual income for

tenants in public housing is below

$4,300; more than half of these tenants

are single parents with children.

b. For energy. Although the average

American household spends 10% of- its

income on energy, low-income house

holds spend one-fourth to one-third

on energy costs. OBRA froze funds

available through Low Income Energy

Assistance . Program-for FY 82-85.

The Congressional Budget Office has

estimated that as energy costs rise,

the real value of this assistance by

FY 84 will have been cut to 35%.

c. For medical services. OBRA reduced

Federal support for Medicaid. States

are not only unlikely to replace these

lost Federal dollars; reductions in

state funds for medical services covered

by Medicaid, already instituted in

recent years, are expected to accel

erate and to impact disproportionately

on female-headed families with chil-

- 8 -

dren. The non-institutionali~ed ~po~tion

of the Medicaid cases, more than half

of whom are women and children in fe

male-headed households, will bear a

large proportion of the forthcoming

cutbacks in medical benefits and ser

vices, because the costs of institu

tionalized care for the aged, blind

and disabled are more difficult for

states to control. Cuts in services,

limits on visits to medical care pro

viders and the elimination of coverage

for such items as eyeglasses and

dental care for children are antici

pated and will force. marginal families

to forego services, to delay them at

risk or to pay for them out of already

reduced incomes.

5. Drastic cuts in programs for infants· and pre-school

children will undoubtedly increase the number of

children who enter school at risk . The Administration

has proposed a 30 % cut in the Special Supplemental

Food Program for Women, Infants and Children (WIC).

6. Budgetary cut s, the elimination of programs, changes

in regulations, and the shift to local control will

have a cumulative impact. At their best, Federal

programs recognized, and sought to address, the

mutually reinforci ng nature of deprivati on in income,

- 9 -

housing, health and education. Eligibility in one

program, e.g. AFDC, was a presumption of need that

would automatically declare eligibility for another,

e.g. free lunches. The number of AFDC children or

recipients of free school meals established a statis

t i cal justification for the designation of schools

as concentrations of poverty, and thus eligible for

targeted Title I programs. Changes in the AFDC

particularly will, therefore, trigger changes in

levels of eligibility and thus of participation in

a range of programs for the disadvantaged.

B. The increased number of poor families will enlarge the

pool of children who would have qualified for assistance

under the old categorical programs. However~ many will

not receive assistance because of drastically reduced

appropriations, higher eligibility standards and the

total phasing out of programs. Programs that have been

critical for economically and educationally disadvantaged

children will suffer severe budget cuts that will result

in a reduction in the number of eligible children served.

Eligibility standards are being tightened, but thousands

of children that meet even the more stringent standards,

e.g . for free or reduced price meals at school, will not

receive benefits to which they are entitled because schools

will eliminate nutrition programs altogether.

C. Block grants, that leave total discretion for program

decisions to local authorities and that provide less money

- 10 -

in the aggregate than was previously available for

categorical programs, will pit groups of children

against each other, as potential beneficiaries scramble

for a slice of a smaller pie. Poor and minority chil-

dren will be at a disadvantage in the competition with

well- organized advocates of programs that largely serve

nonminority and affluent students.

D. The elimination of the Department of Education expresses

the Administration ' s determination to eliminate vital

programs and to vitiate the power base around them that

children's advocates have been able to create. The

Department has become a symbol of the Federal role in

education. This was not true for the old Office of

Education prior to the enactment of significant Federal

.

education programs . The scattering of programs through-

out the Federal Government would make it extremely diffi-

cult for advocacy groups to lobby and monitor effectively

and to impact on shaping the design and implementation

of Federal education programs.

Writing in SCHOOL BOARD NEWS on October 28, 1981, Thomas

A. Shannon, executive director of the National School

Boards Association, pleaded that the Department be given

a chance to prove itself. He commented critically on

options that Secretary Bell has presented to President

Reagan:

*Separate sub-cabinet educational agency

"deprives education of being represented

in the highest councils of our nation •.•

and it would undercut lay citizens con

trol over education by .•. transforming

- 11 -

it into a conclave of professionals who

answer only to themselves - because a

separate agency would be less responsive

than a visible and politically account

able secretary ... "

*Folding education back in Health and

Human Services " ••• would bring back

the bad old days of HEW when education

was tagging Charlie ••• Civil rights

enforcement in the schools was also

amuck - being done by people who knew

nothing about how schools are governed

and administered and were unaccountable

to anybody who did •.• "

*Dispersal of education functions through

out the federal bureaucracy " •.. is the

most onerous of all ••. segments of educa

tion (would be) buried under layers of

different bureaucratic mire •.• Contrary

to what advocate5 of the dispersal .option

claim the flow of bureaucratic confusion

endemic to it cannot be cured by de

signating a White House 'education policy

coordinator' ••. More often than not, it

is the administration of a federal pro

gram that generates problems - not the

policy that undergirds it .•. "

*Education as independent sub-cabinet

foundation " .• . would be impotent to

respond to judicial mandates (with the

results that) the regulation-making

authority will be exercised by the

courts •.. (that) perceive their role ••.

as much broader than the specific is-

sues being litigated .•. Because founda

tions are research-oriented ivory towers, .••

(folding education into an existing

foundation and disgorging impractical

ideas) .•• has the potential for being

a back-door way to introduce nation-

al curricula and tests and ..• cause

endless headaches for local school

boards.

E. Washington-based organizations are gearing up for

the long haul and are increasing their lobbying,

monitoring and advocacy efforts. The Field Founda-

tion has announced its decision to target grants

- 12 -

to such efforts. Some new groups are getting into the

act . The Council on Foundations, and other representa-

tives of organized philanthropy, concerned about the

pressures on their constituencies that have been created

by Reagan's cavalier announcements about volunteerism

and the private sector, have been voices of realism

about the gap that will not be closed as the Federal

Government withdraws. Mayors and governors, undoubtedly

fearful about the lines that will be forming at their

doors, are beginning to challenge the new Federalsim.

There is a possibility that all of these will coalesce

into a political force that will prevent Reagan from

implementing fully his Grand Design. However, it would

be foolish to count on that possibility. It is imperative

for LDF to define what our role should be between now and

Fall 1982.

F. Specific areas of LDF concerns and issues

1. The following are the programs that I believeLDF

should consider monitoring. What our priorities

are, how we should be involved, and whether we

should define a leadership or supportive role

for ourselves should be the subject of a long

staff meeting early in 1982.

Education Consolidation and Improvement Act (ECIA) ,

Chapter I, formerly ESEA Title I

ECIA, Chapter II, Block Grants

Student Financial Aid

School-based Child Nutrition Programs

School-based Vocational Education and Youth

Training Programs

Aid to the Handicapped

Civil Rights Enforcement

- 13 -

2. Issues

a. Budgetary. Reagan is using the budgetary

decision-making process as a vehicle to

make substantial revisions in programs,

bypassing congressional oversight commit

ties. The absence of legislative history

as programs are abandoned or totally re

vamped will haunt us for years. The role

of the Off ice for Management and Budget

(OMB) must be scrutinized and challenged.

Whether OMB is vulnerable to a legal chal

lenge might be an important area of re

search for LDF.

b. The implications of regulatory reform.

Pursuant to Reagan's Executive Order

#12291, a review of regulations is under

way. Reagan defines his approach as

back to the Constitution, back to the

specific language of statutes. If

something is not specifically mandated

or authorized, administrative agencies

should be prohibited from expanding on

language. Reaganites are now involved

in trimming back definitions, tightening

eligibility standards, reducing require

ments for state plans to broad state

ments of assurance, and significantly

reducing data collection and reporting

requirements.

- 14 -

c. The implications of Reagan's concept

of Federalism.

Secretary Bell views the Federal role

as being a pass-through of statutory

language, "non-binding guidance," techni

cal assistance, research and a clearing

house for exemplary programs.

d. The appointment of key policymaking

positions of persons who are antagonistic

to, and unfamilar with programs for the

d isadvantaged and who have no links with

advocates of minority children.

e. The impact of all of the above on black

survival. LDF may want to take a slice

through several key programs that deliver

educational services and identify some

civil rights or equity . issues that might

suggest new litigation, e.g . the shift

under a block grant to programs that

disproportionately benefit affluent kids .

As you will note later, if changes now

being contemplated in the Aid to the

Handicapped are .implemented, the Adminis

tration might be vulnerable to legal

challenge.

- 15 -

II. EDUCATION CONSOLIDATION AND IMPROVEMENT ACTION OF 1981

(ECIA) - Chapter I

(This section reflects consultation with:

Ann Rosewa~er, Administrative Aide to Congressman Miller 202-225-2095

Paul Smith. -Children's Defense Fund 202-483-1470

BettyeHamiiton, Children's Defense Fund 202-483-1470

Hayes Mizell, Chairman, National Advisory Council on the Education

Disadvantaged Children 803-256-6711)

A. OBRA's Title V is the Omnibus Education Reconcilation

Act of 1981. Its Sec. 502 establishes appropriation

limits for FY 82,83 and 84, and supersedes all laws that

are inconsistent with its provisions.

B. The Education Consolidation and Improvement Act of 1981

(ECIA) is Sub-title D of Title V. Its Chapter I, Financial

Assistance to Meet Special Educational Needs of Disadvantaged

Children, is OBRA's revision of ESEA's Title I, and will

take effect on July 1, 1982. The Federal Government inter-

vened iri 1965 in response to the documented failure·of

state and local governments to meet the educational needs

of poor children. Since then Federal funds have provided

leverage over and influenced the priorities of much larger

amounts of state and local funds, for it is only in rural

and large urban school districts {in which 35% of the educa-

tion budget is Federal) where Federal funds are a sub-

stantial percentage of the budget. Still a categorical

program and not a block grant, Chapter I continues con-

gressional policy "to provide financial assistance •.. to

meet the special needs of educationally deprived chil-

dren .•. but to do so in a manner which will eliminate

burdensome, unnecessary and unproductive paperwork and

free the schools of unnecessary Federal superv ision,

- 16 -

direction, and control." The same Administration that

has released school systems from strict standards of

accountability is committing substantially fewer dollars

to them during a period when the number of poor children

is increasing. Reagan has "cut the heartout of federal

assistance, " Hayes Mizell , chairman of the National Ad

visory Council on the Education of Disadvantaged Children,

(NACEDC) has charged, just as studies are documenting

Title I's success in improving the achievement scores of

poor children.

1. Between 1979-80 the number of children in poverty

increased .by over a million - from 10.2 to 11.4

million. One in five American children is poor.

Half of the children now eligible to participate in

Title I programs are not served because of the in

adequacy of current funding levels. Title I has a

"forward funded" budget, so the full impact of

Reagan's budgetary actions will not be felt until

the beginning of the 1982-83 school year. Reagan

has used a combination of ;i;ecisions over budgets

already approved by Congress and threats of fund

deferrals, and has submitted a budget for next year

that is substantially lower than that of President

Carter and those approved by OBRA, the House and

the Senate. (An Administration request to rescind

requires approval by Congress with 45 days or it dies;

a deferral notice submitted to Congress is sustained

if it has not been disapproved within 30 days.) The

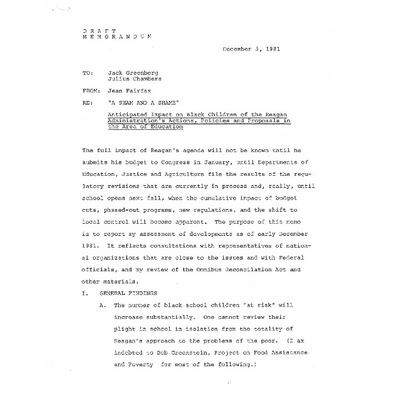

attached chart from NACEDC demonstrates the havoc

- 17 -

Reagan has created. After securing recisions last

spring for funds for this current school year, Reagan

sought additional cuts which would reduce the appro-

priation for next year by 37%. Reporting the Con-

gressional Budget Office's projection that $3.961

billion would be needed to maintain the level of

services, Mizell testified that:

An effective cut of 37% in real service

would mean that 2 ,268,000 children

participating in Title I programs would

be denied services. Of this number,

1,493,000 would lose supplementary in

struction in reading; 693,000 would lose

such instruction in mathematics; and

473,000 would be denied additional in

struction in other subject areas. Health

and nutrition services would also be lost

to 452,000 children, and 1,104,000 chil

dren would lose other support services

such as transportation, guidance, teat

ing, psychological services, etc. (foot-

note omitted) ·

Subcommittee on Elementary, Secondary and

Vocational Education, Committee on Educa

tion and Labor

United States House of Representatives

October 6, 1981

2. In the Department's Questions and Answers Concerning

the Education Consolidation and I mprovement Act of

1981, October 9, 1981, OBRA's departure from key pro-

visions of Title I is made clear:

a. Concentration on the neediest of the needy is

no longer required.

b. Although school systems must consult with

teachers and parents of disadvantaged children,

parent advisory councils (PAC) in each Title

I school and district-level are no longer

E

~I FU~IHNG l.E\'l~l.

{) (111 bll.llon~

e ( <lnl .. l:lr"') l ~J.9

~

~

J.R

J. 7

0

'M

0

.1.6

·fl ).5

~ ) .11

~

~,

J.J

6 J.2

u . ).1

8 .J.O

-~ 7..9

"Q

7..0

~ 7..7

-~ 7..G

:;>';

~

'- .5

·JJ

-~·

7..;,

l

7..]

FY 19RO

Find

Appr:opri-

"tion

FY 1901 FY l?lll

E!?fore fiht1

Kc~cis-

nfon~

~.!'JlONOLO~_or I ~l'L~_!_l~U_t~!'._!_~S~T,E\" r&~

~ .

~

. . ·• "-, . , .......

...

FY 1937. FY 1982 FY J.9!12 F"i 198? r~ 1987.

Cr.rtcr R~~&::tn u;~d:_;r.. t HO!J!i C $~n:.1::c

nud;;.;!t liiu:ch R~co~cil- Appt.~p=i- t.ppf.. Cc1n-

U~t~l~'?t i"tion ~• l:iC'n1'1 IJitt(!'?.

Jan. Ac t tiil !Jill

1901 Hardt

1991 July Septen&t: Seotenfu

1901 1991 1901

\$7. ./175

FY 19132

P.:?q_::m

Scptr::1~hcr

.:..:·t.h1~c t

::;epted.Jei:"

1901

$).9

-~H?ssWial. tlidtl:

o.Hlce ProjecHon · 1E!vei

hild 'tH:lt! t in F'I. 1901.

I

111 r--

r-l

- 18 -

mandated. This will eliminate an important

vehicle for the sus·tained involvement of poor

people that has forced many systems to become

more accountable.

c. The determination of the amounts of f'u_nds

to state educational agencies {_SEA} and

through them to local educational agencies

(LEA} will be under the same payment pro

visions as the existing Title r. However,

the requirements for maintenance of effort

are l ess striIJgent and may be waived by the

SEA for one year. Comparability is still

required but not comparability reports~

LEA's will only be required to file certain

assurances. LEAts must supplement and not

supplant but they may exclude certain funds

in their calculations both. for comparabili t y

and supplementing.

d. SEA 's will be responsible for the monitoring

of and technical assistance to LEA's but can

determine how they will fulfill these functions.

SEA's will be required to file with the Depart

ment only assurances concerning fund disburse

ments.

e. LEA's will file applications, valid for three

years, in which they will make the necessary

assurances and describe their programs. They

are required to conduct an annual assessment of

- 19 -

educational needs, on the basis of which

they will select children for special as

sistance, but LEA's will devel op their own

needs assessment and evaluation processes.

LEA's "will be held accountable for any

breach of assurances" and must keep such

records as may be required for fiscal

audits and program evaluation.

f. The Department's role will be largely that

of providing "non-binding guidance" and

"monitoring will be conducted only as

necessary to ensure compliance with the

simplified requirements of Chapter I and to

investigate specific compliance problems

that SEA's have been unable to resolve.

Although the Department will provide leader

ship and technical assistance, it will be

focused primarily on the development of

effective programs rather than on adherence

to Federal administrative requirements."

(Questions and Answers, p.6) The size of

the Title I staff has already been decimated.

By January 1982, 40 of the 80 staff members

will have been terminated.

3. The provisions coverning aid to private schools are

the most detailed in ECIA and contain the strongest

requirements for a Federal role in the provision of

educational services to needy children and in the

- 20 -

resolution of disputes over such arran~ements,

The Secretary may bypass an LEA that failes to

include eligible private school children and arrange

to have services provided for them directly out of

the state's allocation.

c, The Washington· P'ost on December 8, 1981, leaked an

OMB proposal to cut Chapter I funds to $1.5 billion.

- 21 -

III. EDUCATION CONSOLIDATION AND IMPROVEMENT ACT OF 1981

CHAPTER II

(This section reflects consultation with:

Ann Rosewater, Administrative Aide to Cong. Miller

Linda Brown, Lawyers' Committee for Civil Rights

Children's Defense Fund Staff 202-483-1470)

A. President Reagan has a dream.

I have a dream of my own. I think block

grants are only the intermediate steps.

I dream of the days when the Federal

Government can substitute for those the

turning back to local and state govern

ments of the tax resources we ourselves

have preempted here at the Federal level .••

202-225-2095

202-628-6700

(To the National Association of Counties, March 1981)

For poor and minority Americans, Reagan's dream is a

nightmare. Blocks of Federal programs are being turned

over with less grant money, practically no Federal

monitoring, and no mandates to target services to those

with the greatest need for assistance. The block grant

as the first step in the total withdrawal of the Federal

Government from program areas to which national priori-

ties have been assigned is indeed a "turning back."

B. Chapter II ~epea~s 33 categorical programs and folds

them into an education block grant, effective July 1,

1982, for basic skills development, educational improve-

ment and support services and special projects.

1. Although the former categorical programs had

received about $700 million, substantially

less will be available for allocation to states

next July. The Administration requested about

$500 million earlier this year. According to

the Washington Post on December 8, OMB is now

proposing to slash that amount 40 %.

- 22 -

2. 80% of the appropriation to each state will pass

through the state educational agency (SEA) to

local educational agencies (LEA) without specific

Federal mandates concerning the in-state alloca

tion or the use of the funds at the local level.

Each SEA can determine how it will comply with

the broad provision that funds be distributed

to LEA's on the basis of the relative enrollment

of public and private school pupils, with an

adjustment for high-cost children (i.e. the rela

tive number of children whose education imposes

a higher than average cost per child) • Each

state must have a Governor's Advisory Committee

to advise only on the criteria for the alloca

tion of the 80% and the state's use of the 20%.

According to "Questions and Answers," released·

by the Department of Education in October, if

a state ignores the advice of the Committee,

this will be considered by the Department to

be an internal affair. In another title, OBRA

requires the publication and dissemination of

a report on the intended use of block grants,

in which the state would have to justify the

discontinuation of funding of the former

categorical programs on the basis "that the

program has not proven effectiv e." A con

troversy has arisen over whether this section

applies to Chapter II and whether the state's

- 23 -

report must cover all of the block grant or

only the 20% under the direct control of the

SEA.

3. Some requirements for categorical programs

survive - funds must supplement and not supplant

and there must be maintenance of effort - but

in much weaker language. Maintenance of effort,

for example, will be "calculated on the basis of

aggregate state and local expenditures or per

pupil expenditures for free public elementary

and secondary education. Thus, even though

some LEAs did not maintain effort, expenditure

by other LEAs and the State may make up for the

failure of those LEAs to maintain effort."

(Q & A)

4. The SEA and LEA will be auditing themselves.

"If there appears to be a need fo r a Federal

audit , the responsibile Federal agency will

be expected to make one. In practice, however,

the audit requirements set out by OMB require

the Federal agencies to rely first and foremost

on grant recipients' independent audits and to

build on such audits when a Federal audit is

deemed necessary." (Q & A) The SEA will f ile

audit reports to the Inspector General . LEA

audits must only be "available on request."

5. None of the existing categorical program require

ments will be carried over.

- 24 -

6. OBRA requires equitable participation of private

schools. Q & A indicates that children in pri-

vate academies that are ineligible to receive

Federal funds should be included in the SEA's dis

tribution formula. The state would then determine

in accordance with its own statutes whether such

children should receive Chapter II benefits. Q & A

further states: "However, it should be recognized

that children enrolled in private non-profit schools

are eligible for Chapters 1 and 2 -- not the school."

If the LEA does not accept Chapter II funds, bypass

arrangements to reach children in private schools

will be made by the Secretary and the state. Public

school authorities have already expressed concern

about the involvement of private schools. Gonunent

ing on Q & A's statement that private school chil

dren would be eligible for services in the schools

they atten even if they reside in another district

or state , Steve Sauls of the Florida State Board

of Education anticipated "confusion as to how

private school children are to be counted for the

purpose of allocating funds betwee n dis tricts if

t he children reside in a district different from

the one in which they are enrolled." He also won

dered why Chapter II funds should be allowed for

private school c onstruction but not for public

schools.

7. There will be no standard state application - a

- 25 -

letter will suffice to the Secretary who will

approve only the criteria for the distribution

of 80 %. To receive funds, the LEA must only

have to file with the SEA a 3-year application

for which no formal approval by the state is

required. Subject only to some broad provisions,

each LEA will have complete discretionary

authority over the use of funds and program

decisions.

C. OBRA states, "Regulations issued pursuant to this sub-

title shall not have the standing of a federal statute

or the purposes of judicial review." Inasmuch as the

Administration is talking about "non-binding guidelines"

as wel l as regulations, it is not at all clear what power

and effect promulgations under this title will have.

D. Local and state education officials, as well as legal

experts, have already expressed concern about Chapter II.

1. Large schools systems are worried about the

treatment they will get by the SEA as formula

are developed.

Another concern of . .. many people involved

with Title I in the major urban centers

of the country is that we are not re

placing a federal bureaucracy with a

state bureaucracy and federal regulations

with state regulations •...

Philadelphia and other major school sys

tems throughout the country are deeply

concerned over the flexibility given

to states in the distribution of Title

II Block Grant monies. Historically,

this nation's major urban communities

have had to fight over their fair share

of funding from the states •.•• However,

- 26 - .

one of our fears is that the State legisla

ture, which has the authority to designate

how these funds will be used, may try to

supplant current state funding with funds

available under Title II Block Grant . Our

basic fear here is that we don't in any

way wish to have our current subsidy from

the State reduced because of the Block

Grant funds •. •

Additionally, the consolidation of pro

grams under Title II will result in a

significant cutback of funding currently

available to the school district.

Thomas c. Rosica, School District of Philadelphia

HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES SUBCOMMITTEE ON

ELEMENTARY, SECONDARY AND VOCATIONAL EDUCATION

October 6, 1981

2. SEA representatives are worried about the legal im-

plications for them of the absence of clear guidance

from Washington .

•.• (w)e welcome regulatory relief. We

are concerned, however, that without

reasonable guidance written into ~egula

tions, many of us • . • may end up in court

justifying our actions after the fact •..

We are committed to making these programs

work and do not want to be cited after

the fact for non-compliance. We don't

object to being held accountable, but we

believe we should have the benefit of

appropriate guidance and clear authority

from the outset. We are afraid that

too little regulation may be almost as

bad as too much. Our understanding is

that the Department will issue only a

couple of pages of regulations and rely

on a series of nonbinding questions and

answers to implement congressional in

tent •••• We are responsible for e valuat

ing local Chapter 2 programs starting in

FY 84 .•. but we do not have prior approval

and are concerned about our responsibility

in the event that we find weak local pro

grams •.•• Our planning is complicated

by the uncertainty ..• by expectations

that deeper cuts in the form of recis-

s ions will be proposed early next year ....

We are concerned that too little regula

tion will tilt federaleducation policy-

- 27 -

making further away from the Congress

and toward the courts and that devastating

budget cuts will foreclose the opportuni

ties for improvement that consolidation

signaled.

Testimoney of Steve Sauls

Florida State Board of Education

U.S. HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES SUBCOMMITTEE ON

ELEMENTARY, SECONDARY AND VOCATIONAL EDUCATION

October 6, 1981

3. Concerns of the Office of General Counsel of the

National Education Association about the private

school involvement in Chapter II were expressed in

a memorandum, dated October 21, 1981, from Mike

Simpson to Bob Chanin . Commenting about the loans

and gifts of materials or equipment, Simpson stated

that materials that were not secular would certainly

be declared unconstitutional but "the kinds of 'equip-

ment' which could be purchased by public educational

agencies for use by parochlal schools, are, I f ear,

limited only by the fecund imaginations of private

school officials." · (page 4) Aware that OBRA ex-

pressly permits repairs, minor remodeling or con-

struction at facilities at private schools, he stated:

••• I believe the Court would likely declare

unconstitutional the provisions of ECIA e.x

tending to private and parochial schools

for construction, repair, maintenance and

other capital improvements of buildings and

facilities because of the pervasively relig

ious nature of most private elementary and

secondary schools and the very intrusive

and entangling requirement of government

surveillance to insure the secure use of

such facilities .••

And re diagnostic, theraputic and other services, he

stated:

•

- 28 -

..• there are at least two tenabl~ argu

ments why some of the services authorized

by the Act are unconstitutional. First

there is no statutory restriction on the

provision of services on school grounds •••

and there is no requirement for govern

ment surveillance or auditing.

E. ESAA's consolidation into Chapter II will effectively

eliminate this program that was more than just an im-

portant source of funds for school districts undergoing

desegregation. It forced attention on the recurring

problems in ''second-stage" desegregation, e.g. inschool

segregation, discrimination in discipline, and personnel

practices and required the clearance of the Off ice for

Civil Rights before Federal funds could be disbursed.

The ESAA regulations will be withdrawn. Programs to make

desegregation work will have to compete with others that

have more powerful advocates·.

F. Chapter II will certainly result in conflicts over funds,

jurisdiction, program decisions, and the involvement of

private schools; in struggles among advocates who will

claim residual rights from the old categorical programs

for their children and will be fighting over scarce

resources; and in controversy among school authorities

at the local and state levels over formulas, ·audits and

the meaning of the "non-binding" guidance from Washington.

- 29 -

IV. STUDENT FINANCIAL AID

(This section reflects conversations with and materials received

from:

Patricia Smith, American Council on Education 202-833-5984

Herbert Flamer, Educational Testing Service 609-921-9000

Connie White, Natl. Assn. of Stud. Financial Aid Officers

202-785-0453

Maureen McLaughlin, Congressional Budget Office 202-226-2672)

A. For minorities, meaningful access to postsecondary educa-

tion requires student financial aid programs that are

dependable, adequately funded, equitably administered,

well managed and targeted to the neediest students. The

mismanagement of Federal student aid funds is periodically

exposed by the media. Less attention, however, is devoted

to patterns of inequity in state financial aid programs

which, with a few exceptions, are not reliable sources of

aid for minorities. The Chronicle of Higher Education in

an article and its FACT-FILE on November 18, 1981, reported

a 10.3% increase in state governments' aid to college stu-

dents this year over 1980-81. However, the Chronicle

documented wide variations in (1) the average amount of

awards; (2) the percapita amount of awards (ranging from

$16.88 in New York to 11 cents in Alabama); (3) the pro-

portion of grants to applicants (the 71.8 % cut in state

scholarship funds in Alabama meant that only 2.5% of appli-

cants received aid); and the increase in the share of state

aid to students enrolled in private institutions. Although

only 20 % of t he nation's college students, and a smaller

percent of black students, are enrolled in private institu-

tions, 58 % of all state aid nationally is going to t he private

- 30 -

sector this year. Many state programs are not need~

based and some favor more prestig.ious institutions where

minorities are largely underrepresented~

B. Since the mid 60's, Federal programs of grants and subsi

dized loans to help students finance their education have

been critical factors in the enrollment of blacks in post

secondary education and for the survival of predominan.tly

black institutions most of which are heavily dependent

upon the Federal funds they receive indirectly through

student tuitions and fees. A series of actions and pro

posals by the Reagan Administration - including budgetary

cutbacks, caps on grants, decreased ·Federal subsidies for

loans, revised eligibility standards, phasing out of pro

grams - represent, "a -revolutionary reversal of the nafional

commitment to educational opportunity," according to the

American Council on Education. "Proposals for further

cutbacks in Federal student aid programs suggest that a

fundmental shift may be under way in the Government's

commitment to provide wider access to higher education,"

stated Edward B. Fiske (The New York Times, October 20,

1981) who reported in the same article the conclusion of

the President of the University of Vermont that these

"cuts are not only economic but philosophical." To the

extent that David A. Stockman speaks for the Administration,

his philosophy on financial aid, as presented in testimony

to the House Budget Committee, should be noted:

- 31 -

" .•. I do not accept the notion that the

Federal Government has an obligation to

fund generous grants to anybody that wants

to go to college. It seems to me that if

people want to go to college bad enough,

then there is opportunity and responsibility

on their part to finance their way through

the best they can."

He does not suggest "best they can" measures for students

from families with in~omes under $6,000.

c. Administration's actions with respect to specific programs

1. Pell (formerly Basic Educational Opportunity) Grant

Program is an entitlement program providing non-

discretionary awards to all financially needy stu-

dents who are enrolled at least ·half-time. Without

Pell, 41% of all low-income student recipients would

not have been enrolled in postsecondary education,

according to a Harvard study in 1979~

a. The Education Amendments of 1972 authorized

·awards of $200 to a maximum of $1,900 by FY 82

and $2,600 for FY 86. $2.85 billion would have

been needed to maintain current eligibles and

provide for a $1,800 maximum award in FY 31.

Administrative recisions cut the FY 81 budget

below the Continuing Resolution of December

1980 to $2.346 billion, thus reducing the maximum

award to $1,670. OBRA mandated appropriation

limits ($2.65 billion for FY 82; $2.8 billion

for FY 83 ; and $3 billion for FY 84) • Reagan's

request in September for additional reductions

of 12 % lowered the Administration's proposed FY 82

- 32 -

budget below ~BRA to$2.187 billion. Accord

ing to ACE, this would mean that students

from families with incomes under $10,000

would be protected but that little money

would be available for students above the

pov erty level .

b. Pell eligibility is determined by a national,

uniform and complicated needs-analysis

formula that takes expected family contri

bution and the cost of attendance into con~

sideration. A major controversy has erupted

over the family contribution schedule. OBRA

ordered the Department ~f Eduqation to sub

mit a new schedule to Congress by Septem-

ber 1, 1981. Instead, DE filed a Notice of

Proposed Rulemaking (NPRM) in the Federal

Register on October 16, requesting comments

by December 15. College spokesmen have

charged that this delay in announcing the

new schedule is causing disruption and anxiety;

that the Administration has used the NPRM

without authorization to request continuation

of the $1,670 ceiling on maximum awards when

both houses of Congress have developed their

appropriations based on a $1,800 maximum;

that the Administration is manipulating the

eligibility rules and the family contribution

schedule to conform to Reagan's lower budget;

- 33 -

and that DE's plan to reduce students' eligi

bility if they receive educational benefits

through the G.I. Bill or Social Security is

"unduly harsh." Developments in the needs

analysis must be carefully monitored to

assure that the new system, due to be im

plemented in 1982-83, is not a retreat for

minority and low-income students. In 1980

Congress voted to establish a single needs

analysis formula that would be used in the

Pell as wel l as the three campus based pro

grams (SEOG , CWS and NDSL). Student financial

aid experts, convinced that this was not a

wise amendment, believe they have Congression

al support to separate these need analysis

including how the family size off-set is

calculated. The degree to which child care

expenses can off set income to determine dis

cretionary income is crucial to black women

who are heads of families and who are attempt

ing to improve their status through education .

2. Supplemental Education Opportunity Grants (SEOG),

authorized at $370 million for FY 81 and also by

OBRA fo r FY 82 , but cut by the Reagan budget to

$326 million for FY 82 , would lose 75,000 recipients.

Although the 1980 amendments eliminated language

requiring the targeting of SEOG to the neediest

students , it has been an essential supplement for

needy students attending higher priced public and

- 34 -

and private institutions.

3. College Work-Study (CWS) , authorized for FY 82

at a level of $550 billion by OB.RA, the House and

Senate, would be cut by Reagan to $484 million .

Recipients would be- reduced 110,000

4. National Direct Student Loan (NDSL) supports campus

revolving loan programs, generally at large public

and private institutions. Reagan's budget of $252

million is less than the OBRA ceiling of $286 bil

lion. 50,000 fewer students would receive awards.

5. State Student Incentive Grants (SSIG), set up in

1974 to encourage states to begin or to expand

student aid programs, is still largely concentrated

in a few large states. 89% of SSIG funds are

available only if matched equally by the states.

States with small programs are heavily dependent

upon Federal f unds . In the Chronicle's FACT

FILE , 16-17 states report only incentive grants

in 19 80-81 . The Senate voted to abolish this pro

gram. Reagan 's proposed budget of $68 mil lion,

9 million lower than OBRA, would eliminate 30,000

state awards.

6. Social Security Educational Benefits, paid from

the Social Security Trust area, have been available to

children of a deceased or disabled wage earner

cov ered by Social Security. The surviving spouse

gets the children 's benefits through high school .

- 35 -

Students, who are beneficiaries in their own

right from ages 18-22, receive benefits averaging

$2,000 if they are enrolled fulltime in post-

secondary institutions . OBRA phased this program

out entirely by 1985; no new recipients will be

funded as of June 1982 and current benefits were

cut 25 %. The American Council on Education

criticized this decision:

This step alone will eliminate one

of the largest current sources qf stu

dent support: some 750,000 students

now receive social security benefits

totalling $2 billion annually - one

fifth of total federal student aid.

Since most beneficiaries are from

extremely low-income families, the

loss of these benefits will place

severe strains on other student aid

programs ~hich cannot be increased

even to compensate for inflation.

FACT SHEET ON STUDENT AID, Nov. 6, 1981

7. The Guaranteed Student Loan Program (GSL) is gener

ally believed to be out of control and is in jeopardy,

largely because of the soaring interest rates that

the Government is subsidizing. Students negotiate

bank loans up to $2,500 a year at 9% with GSL subsi-

dizing the interest while the student is enrolled.

After graduation, the student pays the 9 % while GSL

pays the difference between 9% and the market rate.

GSL was without income restrictions from 1978 until

this fall. Recent changes, effective October 1981

impose a 5% origination fee; restrict loans to the

unmet needs of students from families with incomes

- 36 -

under $30,000; and impose a needs test for those

above that level Other revisions are being dis

cussed: exclusion of graduate and professional

students (now 25 % of the . program); limitation to

students with demonstrated need; the elimi nation

of the in-school interest subsidy (a move that

would undoubtedly impact negatively on minority

and poor students since banks would make loans

only to their preferred customers); adding interest

to the principle of the loan so that students

would be borrowing the interest as well (.a student

borrowing $9,000 would end up owing $20,000); and

a total lending ceiling. Under this last plan,

a fixed appropriation would be divided up among

the states and loans would be available on a first

come, first-served basis.

8. Auxili a ry Loans to Assist Stude nts, former l y Parent

Loans, offers subsidized loans up to $3,000, now

includes sel f -supporting studetns. OBRA raise d

the interest from 9 % to 14 %.

D. The Administration is considering a block grant that

might include CWS, SEOG, NDSL, with a total budget of

about $1 billion, although CWS alone gets $550 million

now. Institutions are opposed.

E. The New York Times article on No vember 3, 1981, "Federa l

Budget Cuts Imperil Chances of Many Poor for College

Education," reported on how cuts are a ffecting students

a t Manhattan Community College:

- 37 -

Uncertainty abounds these days ·at com

munity colleges and hundreds of other

institutions where the vast majority of

students come from families that earn

less than $12,000 a year and rely al

most entirely on Federal assistance for

tuition and living expenses.

Recent Federal cuts at one such school,

Manhattan Community College, have already

amounted to a loss this year of more than

$300,000 in Federal Pell grants and

$100,000 in student loans. If further

proposed cuts are approved, the college

could lose at least $250,000 more in

work-study programs, loans and grants,

including 150 jobs that help students

earn money necessary to meet their ex

penses.

The 9,000 students at Manhattan Community,

whose classrooms are scattered about

midtown Manhattan, are like many others

at community colleges. More than half

are over the age of 22, two-thirds are

women and more than half are married or

have at least one dependent. More than

a third receive welfare payments. Most

of them are the . first in their families.

to attend college.

Because many of these students rely on

a. number of social programs that are

expected to be curtailed under the pro

posed cuts, educators say they are among

the most vulnerable. Even though individ

ual reduqtions may appear small - students

receiving Pell grants lost only $30 this

year - educators say the cumulative effect

of such cuts, at a time of rising costs

and reductions in other programs, can tip

the balance between a student's looking

to education to better his employment pos

sibilities or giving up.

''rhese students get a double whammy, 11 said

Howard J. Entin, director of financial aid

at Manhattan Community, adding that he was

particularly concerned that reductions in

day care would prevent students with young

children from continuing their studies.

Reductions in food stamps, too, he said,

would mean that some students who do

not now request educational grant money

for living expenses may have to do so

putting increased pressure on a dwindling

supply of funds.

- 38 -

V. SCHOOL-BASED CHILD NUTRITION PROGRAMS

(Information in thi.s section came from:

Bob Greenstein, Progra.'11 o.n Food Assistance and Poverty

202-

Ed Cooney and other staff, Food Research and Action (FRAC)

202-393-5060)

A. In 1967 when LDF began to challenge patte:rnsof dis-

crimination against poor and minority children in the

National School Lunch Program, only 2 million pupils

received free or reduced price meals at school. Today

10.3 million children receive lunch free and an addi-

tional 1.9 million at a reduced price. Bob Greenstein,

the former administrator of USDA's Food and Nutrition

Service, estimates that minority children are 40-50%

of the recipients of free and reduced price lunches.

30,000 schools now provide breakfast to a 3.5 million

children, 85% of whom are low-income. The Child Care

Program enables over 700,000 needy preschoolers to get

meals and snacks in child care or family day care

centers. Summer Food Service Programs, sponsored by

churches and other private groups, as well as public

agencies, and designed to sustain needy children during

the vacation period, served 2,3 million children last

summer and also provided employment to thousands of

teen-agers.

B. Reagan has claimed that school lunches are in his safety

net, but child nutrition programs may become a tragic

example of the safety net that has been "ripped to

shreads," to quote Mayor Coleman Young . " Hungry chil

dren cannot learn," a.nd "Feed Ki ds ·- It's the Law" were

- 39 -

our banners in the '70's. The Administration is now

threatening the viability of programs that have con-

tributed significantly to the well-being and achieve-

ment of low-income children by drastically reducing

budgets, lowering nutritional standards, tightening

eligibility for free and reduced meals, increasing

charges to pupils and by actions that result in the

total phasing out of nutrition programs.

1. School Lunches suffered a $1 billion, or 29%,

cut in OBRA. USDA subsidizes school lunch pro-

grams at reimburs.ement rates that vary for paid,

reduced or free meals. There is a smaller re-

duction in the general subsidy for free meals

and the special additional subsidy to schools

with 60 % or more recipients of free or reduced

price lunches.

Charges for reduced price meals will rise from

20¢ to 40¢ and the average charge to full-pay-

ing students is expected to rise to $1.00. The

Raleigh News and Observer reported on September 14,

1981, that:

Both administration and legislative

leaders generally agree that state

dollars should not be used to make

up any of the $294 million in federal

money that is expected to be cut from

North Carolina during the two year

budget period .•• a $3.41 million a

year reduction in the school lunch

program ••• could drive up the cost

of school lunches by 2 0 cents a

meal.

- 40 -

Putting a larger burden on paying students may

appear to preserve the safety net but it really

will_ not. The Administration is using stricter

eligibility and verification procedures as de-

vices for budget-cutting and many pupils affected

will be poor • . Under stricter eligibility standards,

thousands of marginal families will no longer

qualify for free meals. (Eligibility is tied to

food stamp eligibility, currently set at 130 % of

poverty, with no standard deductions, or $10,985

for a family of four.) Eligibility for reduced

price lunches is set at 185% of poverty, or

$15,630 for a family of four. Families above

that level, whose children might have qualified

for reduced price runches at 20¢ last year, will

now be charged the full rate. Many families of

the working poor, with both parents employ ed at

slightly above the minimum wage, cannot afford

to buy $1.00 lunches for their children. Faced

with the withdrawal of large numbers of marginal

and middle income families who cannot, or will

not pay $1.00 for lunch, many schools will phase

out their child nutrition programs, either because

they can no longer benef it f rom economies of

scale or because they don't want to be bothered.

Poor children who would qualify for a free meal

will be left completely destitute. Furthermore,

the verification of need has been made more

difficult. Using more complicated procedures,

- 41 -

New York City has 250,000 children who have not

fulfilled verification requirements for this

school term and who may be declared ineligible

on technical grounds for free or reduced price

meals after Christmas. The United States Con-

ference on Mayors reported in The FY 82 Budget

and the Cities (November 20, 1981) that increased

costs and prices have already resulted in de-

creased participation.

For example in Baltimore 4918 children

have dropped out of the school lunch

program. As a result, some schools

may not be able to continue their pro

grams. Of 54 cities providing informa

tion about the impact of the cuts on

their school lunch program, almost a

third said the effects was disastrous,

another third said substantial, and

the remainder indicated moderate

effects. (p.35)

"Let 'em eat ketchup!" - the effort to achieve

budgetary cuts by lowering the nutritional value

of a school lunch from one-third to one-fourth

of the Recommended Dietary Allowance and by per-

mitting schools to count catsup and pickes as

vegetables died from a deluge of public outrage

and ridicule. The issue has not died . The

Secretary will be issuing revised nutritional

regulations.

2. School Breakfasts, evaluated by the Congressional

Budget Office as the most nutritionally effective

and least costly of all the child nutrition programs,

suffered reimbursements cuts of 39 % for reduced

- 42 -

price and 50 % for fully-paid meals. Further

more , the definition of schools in "severe need"

that qualify for additional subsidies has been

changed to include only those schools 40 % of

whose pupils receive a free or reduced price

lunch.

3. The Summer Food Service Program suffered a cut

of $90 million. OBRA imposes new requirements

on eligible sponsors and areas. Previously,

community action agencies, churches , YM-YWCA's,

and organizations of poor people could sponsor a

program. Now, onl y school food authorities,

residential camps and certain public bodies

can be sponsors. Of the 2.3 million children

served in 1 980 only 920 ,000 were served by the

kinds of bodies that can now qualify as sponsors.

Furthermore, the new requirement that the program

can operate only in areas where over 50 % of the

children meet guidelines for free or reduced price

meals, will eliminate many rural areas.

4. The Special Milk Program was cut $95 million and

will be restricted to schools that have n e ither

a breakfast nor a lunch program. Children of

working poor families, forced to bring lunches

from home because they cannot pay the full price

for a meal, will be unable to buy milk.

c. Knowledgeable informants predict that Reagan may propose

the total phasing out of subsidies to nonpoor pupils,

- 43 -

that would undoubtedly result in dropping out of

thousands of schools from nutrition service. Summer

Food Service may be completely abolished. A block

grant for all child nutrition programs other than the

lunch program is being considered.

- 44 -

VI. SCHOOL-RELATED VOCATIONAL EDUCATION AND SCHOOL-RELATED

TRAINING PROGRAMS

This section will be written later. The situation is in

flux; the future is difficult to anticipate at the present

time. OBRA reauthorized vocational education until FY 84.

CETA youth programs have been drastically cut and are due

to expire next September.

- 45 -

VII. AID TO THE HANDICAPPED

A. The pervasive misclassification of black children and

callous indifference to their needs have resulted both

in the disproportionate representation of blacks in special

education and in the denial of services to those who are

really handicapped.

Traditionally, handicapped children and

nonwhite children have been the most

vulnerable to discrimination in education,

the most likely to be excluded or un

served by the public schools. Obviously,

when a child is both handicapped and a

minority (s)he is in danger on two counts:

in double jeopardy. ·

Double Jeopardy: The Plight of Minority

Students in Special Education, Massachusetts

Advocacy Center, 1978

B. Federal legislation has provided the legal framework

for major breakthroughs in addressing the educational

needs of the handicapped. The Rehabiliation Act of

1973, Section 504, Subpart D (Preschool, Elementary

and Secondary Education) deals with nondiscrimination

on the basis of handicap and requires equal education-

al opportunity to handicapped persons by recipients of

Federal funds. Regulations were promulgated May 4,

1977. The Education of the Handicappaed Act (EHA) of

1975, PL 91-230, Part B, as amended by PL 94-142, is

one of the most prescriptive laws ever enacted. It

defines the Federal role as assuring: that all handi-

capped children have available free and appropriate

public education designed to meet their unique needs;

that the rights of handicapped children and parents are

- 46 -

protected; that efforts to educate the handicapped are

effective. Federal financial assistance is provided to

states and localities. State educational agencies (SEA)

apply for and receive entitlement grants based on the

number of handicapped children, ages 3-21, receiving

special education and related services. Regulations issued

August 23, 1977, for full implementation in September

1980, address: the identification, location and evaluation

of handicapped children; the development of individualized

educational programs (IEP); creation of comprehensive per

sonnel development systems; counting of handicapped chil- .

dren for allocation purposes; services to be provided to

assure free, appropriate public education (FAPE); priorities

in the use of Part B funds; administrative details and

procedural safeguards (complaints, notice, hearings, due

process).

C. The Reagan Administration has declared EHA to be a major

rule and a priority target for deregulation. EHA has not

yet been consolidated into a block grant. Some informants

believe the Administration may seek legislation to abolish

or substantially revise EHA. The Office of Special Educa

tion's (OSE) Briefing Paper: Initial Review of Regula

tions Under Part B of the Education of the Handicapped Act,

as Amended September 1, 1981, prov ides clear indication

of the options under regulatory reform that the Administra

tion is considering that would seriously weaken the im

plementation of EHA. As the date for the full implementa

tion of the EHA regulations approached, DE responded to

- 47 -

concerns for guidance andappointed a Task Force on Equal

Educational Opportunity for Handicapped Children that

recommended in October 1980 that formal guidance be pro

vided~ OSE and OCR published on December 24, 1980, a

Notice of Intent to Public Regulations. OSE's Briefing

Paper reports the comments received (also taking note of

judicial decisions and areas under litigation) and in

corporates some in the options that the Administration

is reviewing. The deregulated regulations for EHA and

Sec. 504 are due soon. Some appear to be scheduled for

December 1981; others for January and March 1982.

D. OSE's Briefing Paper identifies 16 "opportunities for

deregulation," determines in each case how regulations

expanded upon the statute, especially notes how the regula

tions have been burdensome or have required excessive

paperwork, and lists options for change. This detailed

74 page document cannot be easily summarized. Here are

the hi~hlights of the 16 issues under debate:

1. Definitions

Whether OSE was justified in breathing life into

EHA by expanding on definitions or whether states

should be allowed to make their own definitions

is critical. It affects such issues as: the scope

of special education; the precise meaning of "at

no cost" and whether it includes noneducational

services; the definition of handicapping conditions

that adversely affect education; how children are

evaluated to determine handicapping; whether ex

clusions, e.g. for excessively disruptive children,

- 48 -

should be allowed; whether the scope of mandated

related services should include noneducational,

health- related or life support services; and

labeling, especially of learning-disabled children.

2. State Plans

EHA requires states to file plans that assure free

appropriate public education (FAPE) to all handi

capped children. Changes under consideration could

limit current requirements for : timelines for

FAPE; submission of data and financial information;

providing statistical profiles on the needs of

children; priorities for and descriptions of ser

vices to handicapped children; submission of

methods and data for the identification, location

and evaluation of the handicapped; procedures for

IEP; meeting the requirement of the least restrictive

environment; and personnel development.

3 . Local Education Agency (LEA) Application to SEA

EHA required assurances that LEA's use Federal funds

for excess costs (and not supplant local funds) ,

establish timetables to meet the full services goal

with FAPE for all handicapped children, and in

volve parents. The current regulations require

description and documentation of the policies and

procedures that the LEA will implement to fulfill

the commitment for an IEP for each child. We know

from our experiences in other areas that stripping

the regulations back to a mere assurance from the

LEA would gut the program.

- 49 -

4. State Advisory Panels

The regulations expand on the statutory language

and require balanced and representative panels,

adequate public notice, and interpreters as ap

propriate. The substitution of "non-binding"

guidance to the states in this area could result

in the absence of advocacy groups from these over

sight bodies.

5. Allocation of Funds; Reports

Clearly addressing the evidence that school dis

tricts have misclassified children to get Federal

funds, EHA limits the allocation of funds to 12 %

of children ages 5-17 and caps the number of chil_

dren counted as having specific learning disabilities

to one-sixth of the 12% until Federal criteria

have been promulgated. EHA requires DE to conduct

studies and assessments and to submit reports to

the Congress and the public concerning the number

of children needing special education, the number

receiving FAPE, the evaluation of state efforts to

assure that children are being educated in the

least restrictive environment and of the effective

ness of the IEP. Inasmuch as EHA is especially

prescriptive in this area, the Briefing Paper

focuses on the regulation's criteria for counting

children and the revision of the section on data

collection to permit states to determine their own

procedures for meeting reporting requirements . Any

- 50 -

deviation from nationally mandated data collection

procedures would certainly be a regression.

6. Free Appropriate Public Education (FAPE)

EHA requires states to provide special education

and related services to all handicapped children

(3-21) at public expense and to establish priorities

for implementing this requirement. The regulations

expand on EHA to ensure inclusiveness of coverage.

What is provided for some handicapped must be

provided for all. Handicapped must have equal

access to services provided to nonhandicapped.

For example, if· state law or a court order requires

that education be provided in any category, then

· the state must make FAPE available to children

of the same age in that category. Handicapped

children must be served in the same proportion as

nonhandicapped in an educational area. Residential

placements where required must be made available

at no cost for room and board and nonmedical care.

Handicapped children must have equal opportunities

for participation in nonacademic and extracurricular

activities, including physical education. This

section goes to the heart of the controversy over

what are the educational and related services that

states must provide.

7. Extended School Year Program

Neither EHA nor the regulations specifically address

this issue, but it has been a matter of parental

- 51 -

concern and litigation. DSE noted that all judi-

cial decisions on record invalidated state practices

that precluded extended services for handicapped

children. DE might decide to leave this issue to

the courts for rulings on a case by case basis, to

define narrowly the target population eligible for

extended services, or to get a legislative solution,

as noted in the following report from a DE staff member:

In Armstrong v. Kline, 476 F.Supp. 583

(E.D. Pa. 1979) a federal district court

held that Pennsylvania's 180-day annual

limit o n public education provided to any

child precludes formulation for individual

ized educational programs for mentally re

tarded children in violation of their right

to a free appropriate public education under

the Education for All Handicapped Children

Act. The Court of Appeals for the Third

Circuit affirmed in July 1980. 49 LW 2105 .

In briefs as amicus curiae the Department

of Justice in the past took the position

that the 180-day limit~tion also violated

Section 504 of the Rehabiliation Act of

1973. Department of Education General Coun

sel Dan Oliver in a memorandum to Secretary

T.H. Bell states that a legislative solu

tion is appropriate to get around these

court rulings. He states he has drafted

proposed legislation providing that noth

ing in Section 504 of the Education f or

All Handicapped Children Act shall be

interpreted to require education of handi

capped students beyond the normal school

year. (On May 4, 19 81 Senator Hatch in

troduced s. 1103 a nd on May 20., 1981

Representative Erlenborn introduced H. R.

3645, legislation proposed by the ad

ministration to repeal the provision of

the Education for All Handicapped Children

Act that imposes upon recipients of f eder

al funds any special obligations for

handicapped students. See, in particular,

Section 313(b) of the Elementary and

Secondary Education Consolidation Act of

1981.)

OCR has a number of 180-day annual limit

- 52

cases, some of which are ready for ad

ministrative enforcement.

Other courts have also addressed the

issue, each concluding that the inflexible

limitation on the amount of annual in

struction available to handicapped child

ren is inconsistent with the requirements

of federal law. Georgia Association of

Retarded Citizens v. McDaniel, No. 78-

1950-A (N.D. Ga. Ap. 2, 1981); Anderson

v. Thompson, 495 F.Supp. 1256 (E.D. Wisc.

1980): In re Richard K., Educ. for the

Handicapped Law Report 551:192 (D. N.H.

Je. 8, 1979).