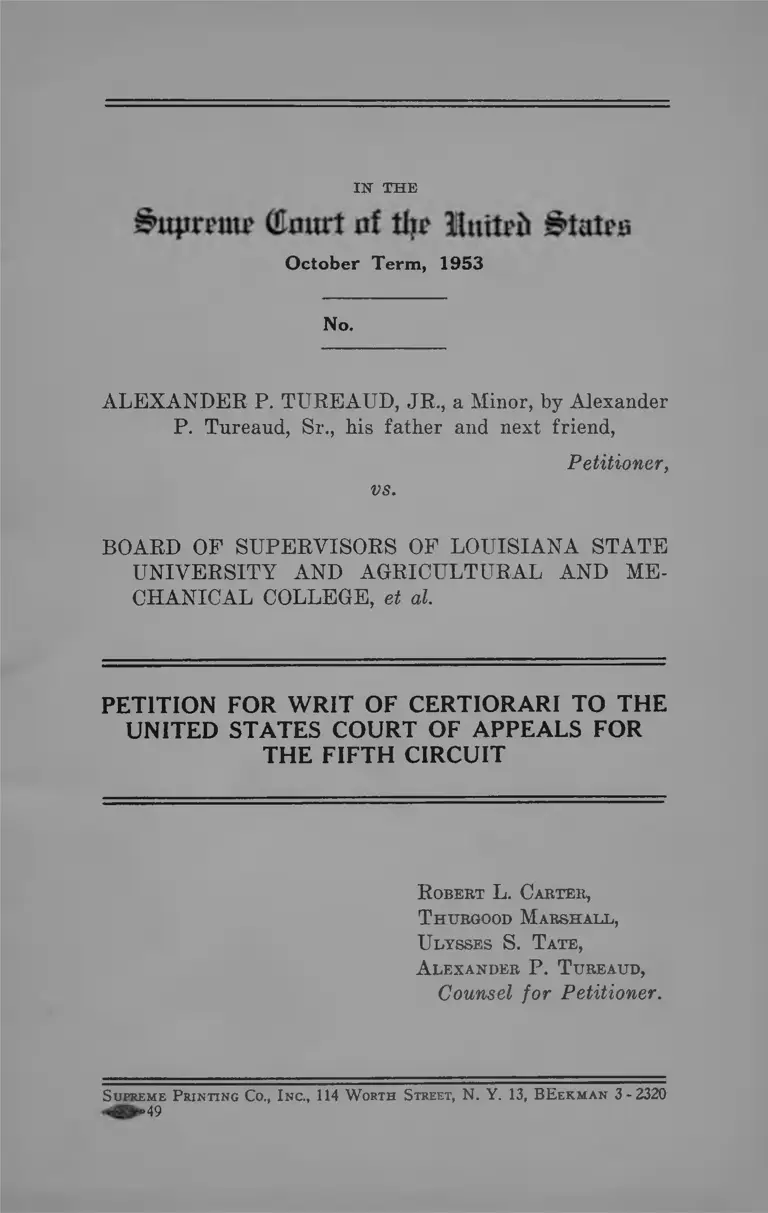

Tureaud v. Board of Supervisors of Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Petition for Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

October 5, 1953

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Tureaud v. Board of Supervisors of Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Petition for Writ of Certiorari, 1953. 07d9e702-c79a-ee11-be37-000d3a574715. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/6d8f1221-43a0-4e2f-86b2-88cc35ab894c/tureaud-v-board-of-supervisors-of-louisiana-state-university-and-agricultural-and-mechanical-college-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

IN T H E

O cto b er T erm , 1953

No.

ALEXANDER P. TUREAUD, JR., a Minor, by Alexander

P. Tureaud, Sr., his father and next friend,

Petitioner,

vs.

BOARD OP SUPERVISORS OP LOUISIANA STATE

UNIVERSITY AND AGRICULTURAL AND ME

CHANICAL COLLEGE, et at.

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR

THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

R obert L. Carter,

T htjrgood Marshall,

Ulysses S. Tate,

Alexander P. T ureaud,

Counsel for Petitioner.

S upreme P rinting Co,, I nc., 114 W orth Street, N. Y. 13, B E ekman 3 - 2320

“ -49

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PAGE

Opinions Below .............................................................. 1

Jurisdiction ..................................................................... 2

Question Presented ........................................................ 2

Constitutional Provision Involved................................ 2

Statement of the Case .................................................. 2

The Complaint and Hearing on the Motion for

Preliminary Injunction ..................................... 2

The Evidence as to Equality of Facilities............. 5

Proceedings at the Appellate Level ..................... 11

Specifications of Errors to Be U rged ............................ 12

Reasons for the Allowance of the W r i t ........................ 13

Conclusion ....................................................................... 21

Table of Cases

American Federation of Labor v. Watson, 327 U. S.

582 ............................................................................. 13

California Water Service Co. v. Redding, 304 U. S.

252 ............................................................................... 13,16

Carter v. School Board of Arlington County, 182 F.

2d 531 (C. A. 4th 1950) ........................................... 19

Cleveland v. United States, 323 U. S. 329 ................. 19, 21

Corbin v. School Board of Pulaski County, 177 F. 2d

924 (C. A. 4th 1949) ................................................. 19

Edelman v. Boeing Air Transport, 289 U. S. 249 . . . . 18

Ex Parte Bransford, 310 U. S. 354 ........................ 18,19

Ex Parte Hobbs, 280 U. S. 1 6 8 ................................. 18,19

Ex Parte Williams, 277 U. S. 267 .............................. 13

11

PAGE

Foister v. Board of Supervisors, Civil Action No.

937 (E. D. La. 1952) ........................................... 17,20,21

Gray v. Board of Trustees, 97 F. Supp. 463 (Tenn.

1951)........................................................................... 20

Gully V. Interstate National Gas Co., 292 U. S. 16 .. 16

Jameson & Co. v. Moregnthau, 307 U. S. 17 1 ........ 16

18

17

McCart v. Indianapolis Water Co., 302 U. E. 419 . . .

Missouri ex rel Gaines v. Canada, 305 U. S. 337 . . .

Oklahoma Gas & Electric Co. v. Oklahoma Packing

Co., 292 U. S. 386 ...................................................... 13

Oklahoma Natural Gas Co. v. Russell, 261 U. S. 290 13

Payne v. Board of Supervisors, Civil Action No. 894

(E. D. La. 1952) ...................................................17,20,21

Phillips V. United States, 312 U. S. 246 ............. 13,16,18,19

Plessy V. Ferguson, 163 U. S. 573 ............................ 17

Rorick v. The Everglades Drainage Dist., 307 U. S.

208 ....................................... 18

17

20

Sipuel V. Board of Regents, 332 U. S. 631 .................

Spielman Motor Sales Co. v. Dodge, 295 U. S. 8 9 ___

Watch Tower Bible & Tract Soiety v. Bristol, 24 F.

Supp. 57 (Conn. 1938), aff’d 305 U. S. 572 .............

Wichita Falls Junior College v. Battle, 204 F. 2d

632 ............................................................................

Wilson V. Board of Supervisors, 92 F. Supp. 986

(E. D. La. 1950) ...........................................14,16,17,20

20

20

IN THE

QInurt at t̂al̂ s

O cto b er T erm , 1953

No.

Alexandbe P. Tubeaud, J r ., a Minor, by Alexander P.

Tureaud, Sr., his father and next friend.

Petitioner,

vs.

B oard of Supervisors of Louisiana State University and

A gricultural and Mechanical College, et al.

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR

THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

To the Honorable, the Chief Justice of the United

States and the Associates Justices of the

Supreme Court of the United States:

Petitioner prays that a writ of certiorari issue to review

the judgment of the United States Court of Appeals for the

Fifth Circuit entered in the above-entitled cause on Octo

ber 28, 1953.

Opinions Below

The opinion, findings of fact and conclusions of law of

the District Court (R. 21-30) is reported in 116 F. Supp.

248. The opinion of the Court of Appeals (R. 35-45) is

reported in 207 F. 2d 807.

Jurisdiction

The judgment of the Court of Appeals was entered on

October 28, 1953 (R. 45). Jurisdiction of this Court is

invoked pursuant to Title 28, United States Code, Section

1251(1). On November 16, 1953 this Court stayed the

judgment of the Court of Appeals, pending the filing and

final disposition of this petition for writ of certiorari. An

order extending the time for filing this petition from

January 26, 1954 to February 16, 1954 was granted on

January 26, 1954 (R. 47).

Question Presented

Whether this is a cause which must be heard and deter

mined by a district court of three judges pursuant to

Title 28, United States Code, Section 2281 et seq.

Constitutional Provision Involved

Article XII, Section I of the Constitution of Louisiana

provides as follows:

The educational system of the state shall consist of all

free public schools, and all institutions of learning sup

ported in whole or in part by appropriations of public

funds. Separate free public schools shall be maintained

for the education of white and colored children between the

ages of six and eighteen years.

Statement of the Case

T he C om plain t a n d H earin g on th e M otion fo r

P re lim in ary In junc tion

Petitioner is a minor of 17 years of age. He is a citizen

of the United States and a citizen and resident of the State

of Louisiana (R. 2). On or about June 5, 1953, petitioner,

being duly qualified, made application for admission at the

next regular school term beginning September, 1953, to the

first-year class (Junior Division) of Louisiana State Uni

versity and Agricultural and Mechanical College (E. 5),

an institution of higher learning maintained and supported

by the State of Louisiana. Petitioner desired to pursue a

combined course in arts and science and law offered under

the curriculum of the College of Arts and Sciences and the

School of Law. Those successfully' ̂ completing this course

receive both an A.B. or B.S. degree and an LL.B. degree

in six rather than seven years (E. 4-5). On or about August

8, 1953, petitioner was advised by respondent, John A.

Hunter, registrar of the University, of the rejection of his

application (E. 6) pursuant to the University’s policy of

“ not admitting Negro students to that area.’’ (Pre-trial

depositions, p. 52.) Whereupon, petitioner, by his father

and next friend, instituted the present litigation.

In his complaint, petitioner made application for a tem

porary and permanent injunction to restrain respondents

from refusing solely on the basis of race and color to admit

him and other Negroes similarly situated to Louisiana

State University to pursue the combination course in arts

and science and law (E. 2, 8, 11). Jurisdiction was invoked

under Title 28, United States Code, Section 2281 (E. 2).

Petitioner sought a hearing and determination by a district

court of three judges of his application to enjoin respond

ents from refusing to admit him to Louisiana State Uni

versity in the enforcement and execution of a state statute

and order of the respondent Board of Supervisors barring

the admission of Negroes to the University. It was alleged

that the statute and order were in conflict with the federal

Constitution.

The District Judge, however, taking the view that a

three-judge court was not required, ordered the case set

down for hearing before him sitting alone. Petitioner

abandoned his claim to a hearing before a specially con

stituted federal court as required under Title 28, United

States Code, Section 2281 and proceeded without protest

to a hearing on the motion for preliminary injunction.

No proof tending to establish a claim of the unconstitution

ality of segregation per se was submitted. Rather the

evidence dealt solely with whether the educational oppor

tunities, offerings and facilities at Southern University,

the state-supported institution of higher learning for

Negroes, were equal or substantially equal to those avail

able at Louisiana State University with respect to the

combination course desired (see depositions, findings of

fact and appendix thereto of the District Court). Respond

ents filed a motion to dismiss and a return and answer

(R. 13). After hearing on the motion for preliminary

injunction and consideration of the evidence presented,

including pre-trial depositions and catalogTies of Louisiana

State University (introduced as Plaintiff’s Exhibit #1 )

and of Southern University (introduced as Plaintiff’s

Exhibit # 3 ), the court, on September 11, 1953, denied

respondent’s motion to dismiss, and found that petitioner

was denied his constitutional right to receive equal educa

tional opportunities by being refused admission to Louisiana

State University. The court, thereupon, issued the tempo

rary injunction applied for, restraining respondents from

refusing to admit petitioner to the Junior Division of

Louisiana State University to pursue the combination

course in arts and science and law for which he had applied

(R. 32).

The evidence adduced at the pre-trial depositions, and

from the catalogues of Louisiana State University and

Southern University which is set out in substance in the

appendix to the District Court’s findings of fact (R. 27

et seq.), amply supports the court’s findings of fact that

petitioner could not receive at Southern LTniversity educa

tional opportunities equal to those available at Louisiana

State University.

T h e E vidence as to E q u a lity o f F ac ilities

1.

L ouisiana State Univebsity

Eespoiidents offer a combination arts and science and

law course at Louisiana State University whereby a student

may complete the requirements for and receive an A.B. or

B.S. and an LL.B. degree in six years rather than in seven

years (Catalogue of Louisiana State University 1953-1955

[hereafter referred to as PL Ex. #1 ], pp. 77 and 151); a

combination course in commerce and law (PL Ex. #1, pp.

113 and 151), and in geology and law (PL Ex. :̂ 1̂, pp. 100

and 151).

SouTHEEN University

Southern University offers a combination course in

political science and law, English and law and mathematics

and law (Catalogue of Southern University [hereafter

referred to as PL Ex. # 3 ], pp. 208-210). Very few students

have undertaken this course and no degree under this

program has been awarded at Southern (depositions, p.

88). At present only one applicant has applied for the

combination curriculum (depositions, p. 89).

2.

L ouisiana State U niversity

Louisiana State University operates on an annual budget

of $12,000,000 (depositions, p. 12). It has 6400 students

(depositions, p. 54) with a per capita operating cost of

$1875.00 per student. I t is composed of 17 major adminis

trative divisions, including a Junior Division, a Junior

College, a Junior Term, a General Extension Division, a

University College (for those unable to attend regular day

sessions, PL Ex. #1 , pp. 160-161) and 12 other colleges with

various divisions, departments and schools within these

colleges (PL Ex. #1 , p. 37), and offers bachelors degrees at

the college level, masters and doctoral degrees at the gradu

ate school level, and various degrees at the profes'sional

school level (P. Ex. #1 , p. 37). It is a member of the

Southern Association of Colleges and Secondary Schools

(depositions, p. 9).

Southern U niversity

Southern University operates on an annual budget of

$2,000,000 (depositions, p. 59). There are approximately

2900 students enrolled in the college proper (depositions,

p. 73) with a per capita cost of $689.65 per student. With

the exception of the law school, the entire instruction offered

is at the college level (depositions, p. 59). I t is in fact a

general college (depositions, p. 59). The institution is

approved by the Southern Association of Colleges and

Secondary Schools, but unlike Louisiana State University

is not a member of that accrediting agency (depositions,

p. 59). There are 150 regular faculty members outside the

law school in the entire University (depositions, p. 60),

including 91 instructors, 30 assistant professors, 16 asso

ciate professors and 16 full professors (depositions, p. 71).

3.

Louisiana State U niversity

At the college level is the Junior Division (where all

first year college work is concentrated), the College of

Agriculture, the College of Chemistry and Physics, the

College of Commerce, the College of Education, the College

of Engineering, the College of Arts and Sciences and a

School of Music (PI. Ex. # 1 ).

Southern U niversity

The college offers a program of freshman studies (PI.

Ex. #3, pxi. 69-73 inch). It contains a Division of Agricul

ture (PI. Ex. #3, p. 74) as compared with a College of!

Agriculture at Louisiana State University; a Division of

Business (PI. Ex. #3 , p. 86) as compared with a College

of Commerce at Louisiana State IJniversity; a Division of

Education (PI. Ex. #3 , p. 100) as compared with a College

of Education at Louisiana State University; a Division of

Health and Physical Education (PI. Ex. #3 , p. 131); a

Division of Home Economics (PI. Ex. #3, p. 138); a Divi

sion of Industrial and Technical Education (PI. Ex. #3,

p. 146); a Division of Military Science and Tactics (PI. Ex.

#3, p. 196); a Division of Music (PI. Ex. #3, p. 201) as

compared with the School of Music at Louisiana State

University and a Division of Liberal Arts and Sciences

(PI. Ex. #3 , p. 162) as compared with a College of Arts

and Sciences at Louisiana State University.

4.

L ouisiana State U niversity

The College of Arts and Sciences is headed by Dean

Cecil G. Taylor, who holds a Ph. D. degree (depositions,

p. 15, and PL Ex. #1, p. 93). It contains 18 departments

in the following fields: Air Science; Books and Libraries;

Botany; Bacteriology and Plant Pathology; English; Fine

Arts; Foreign Languages (Classical, Germanic and Slavic

and Romance); Geography and Anthropology; Geology;

Government; History; Journalism; Mathematics; Military

Science; Philosophy; Psychology; Sociology; Speech; and

Zoology, Physiology and Entomology (PI. Ex. #1, p. 93).

The college is staffed by 160 regular faculty members plus

an additional instructional force below the faculty rank

(depositions, p. 34). Of the regular faculty staff of 160,

approximately 25% are assistant professors, 25% are asso

ciate professors, and 25% are of full professional rank

(depositions, p. 35). Between 600 and 700 students are

enrolled (depositions, p. 16). The goal of the college is to

secure as instructors those who hold Ph. D. degrees in their

respective fields (deiiositions, i). 35). Tlie Dean’s salary

is $9700 (depositions, p. 40).

SO U TH EB IT U n IVEBSITY

The Division of Liberal Arts and Sciences is composed

of nine departments including the departments of Fine and

Applied Arts; Biology; Chemistry; Physics (as compared

to the College of Chemistry and Physics at Louisiana State

University), English; Mathematics; Modern Poreigai Lan

guages; Psychology; and Social Sciences. There are some

66 regular faculty members including a part-time instructor

(PI. Ex. #3 , pp. 164, 167, 170, 177, 172, 176, 179, 181, 182).

It should be noted that there is no department of Air

Science; Books and Libraries; Botany; Bacteriology and

Plant Pathology; Geography and Anthropology; Geology;

Government; History; Journalism; Philosophy; Sociology;

Speech; or Zoology. I t should also be noted that Greek,

Germanic and Slavic Languages, Italian and Portuguese

are not taught.

Dean J. D. Cade who holds an M.A. degree (PI. Ex. #3,

p. 8) is dean of the College and Director of the Division of

Liberal Arts and Sciences (PI. Ex. #3 , p. 163). He receives

a salary of $7200 (depositions, p. 97). The requirement at

Southern for an instructorship is a Master’s degree (PI. Ex.

#3, p. 72).

5.

Louisiana St.'Vte U nivebsity

In the College of Arts and Sciences, the catalogue indi

cates that the Department of Books and Libraries has two

instructors and offers two courses (PI. Ex. # 1, p. 181);

the Department of Botany, Bacteriology and Plant Pathol

ogy has eleven faculty members and offers 37 courses (PL

# l j PP- 181-182); the Department of Ancient and

Modern Foreign Languages has two professors in Classical

Languages and offers 17 courses (PL Ex. #1, p. 174),

3 teachers of German, Slavic and Eussian languages and

offers 17 courses (PL Ex. #1, pp. 174-175), and 12 teachers

of Eomance languages, offering 23 courses in French, 2 in

9

Italian, 2 in Portuguese, 20 in Spanish and 2 in Romance

Philology and Bibliography (PL Ex. #1, pp. 175-178); the

Department of English has 33 teachers and offers 64 courses

(PI. Ex. #1 , pp. 201-203); the Department of Fine Arts has

12 teachers and otters 42 courses (PI. Ex. #1 , p. 203); the

Department of Government has 5 professors and offers 32

courses (PI. Ex. #1, p. 212); the Department of History

has 10 teachers and offers 38 courses (PI. Ex. #1, pp. 218-

219); the Department of Journalism has 6 teachers and

offers 19 courses (PI. Ex. #1 , pp. 223-224); the Department

of Mathematics has 25 teachers and offers 38 courses (PI.

Ex. #1, pp. 225-226); the Department of Philosophy has

3 teachers and offers 22 courses (PI. Ex. #1 , pp. 234-235);

the Department of Psychology has 9 teachers and offers 44

courses (PL Ex. #1, pp. 238-239); the Department of

Sociology has 11 professors and offers 41 courses (PL Ex.

#1 , pp. 243-245); and the Department of Zoology, Physi

ology and Etomology has 11 teachers and offers 45 courses

(PL Ex. #1 , pp. 252-255).

S O U T H E E N U n IVEESITY

Within the Division of Liberal Arts and Sciences at

Southern, the catalogue indicates that the Department of

Fine and Applied Arts has 3 faculty members and offers

18 courses (PL Ex. #3, pp. 164-166); the Department of

Biology has 12 faculty members, with one on leave, and

offers 31 courses (PL Ex. #3 , pp. 167-170); the Department

of Chemistry has 4 faculty members and offers 11 courses

(PL Ex. #3, pp. 170-172); the Department of English has

17 faculty members, one of whom is designated as part

time, and offers 27 courses, including 6 courses in English

Composition and Journalism and 11 courses in Speech (PL

Ex. #3, pp. 173-176); the Department of ilathematics has

7 faculty members and offers 11 courses (PL Ex. #3, pp.

176-177); the Department of Physics has 3 faculty members

and offers 5 courses (PL Ex. #3, pp. 177-178); the Depart-

10

ment of Modern Foreig-n Languages has 4 teachers, with

one on leave, and offers 10 courses in Spanish, 4 in German

and 9 in French (PL Ex. #3 , pp. 179-181); the Department

of Psychology has one teacher and offers 10 courses (PL

Ex. #3, pp. 181-182); the Department of Social Sciences

has 15 faculty members, with one on leave, and offers 96

courses—15 courses in Economics, 12 in Geography, 30 in

History, 22 in Political Science, 15 in Sociology and 2 in

Anthropology (PL Ex. #3, pp. 182-193).

6.

Louisiana State U niversity

Louisiana State University offers a combined course in

arts and sciences and law, geology and law, and commerce

and law as indicated. After completion of the Junior

Division, a student must complete prescribed minimum re

quirements for the arts and science degree (PL Ex. #1,

p. 96) and he may receive the remainder of the necessary

credits for his degree by choosing from a variety of elec

tives, within certain limitations as set out in Plaintiff’s Ex

hibit #1 , page 96 and depositions, pages 30-33. After com

pletion of the Junior Division a student who at first matricu

lated for the arts and sciences and law course may switch

to geology and law without loss of time or credits (deposi

tions, p. 33). There is no question but that this combination

curriculum is a working program and going concern.

Southern U niversity

Southern University offers a combination curriculum in

3 fields as previously indicated. The program is fixed as

set forth in the school catalogue (PL Ex. #3 , pp. 208-210).

No deviation from the course of study there prescribed is

permissible under Southern’s program (depositions, pp.

97-98).

11

E vident Conclusions

a. With respect to the combined arts and sciences and

law curriculum at Louisiana State University as contrasted

with the combination curriculum at Southern, the student

pursuing the course at Louisiana State University has far

greater advantages and opportunities than a student at

Southern.

b. The combination curriculum at Louisiana State Uni

versity is a well-organized, well-functioning program. At

Southern, on the other hand, while the course exists on

paper, as yet no degree has been awarded under this pro

gram and only one student has indicated interest at the

present school term.

c. The Louisiana State University student in the Col

lege of Arts and Sciences has 160 regular faculty members

available of which 75% are of professional rank. The

students at Southern have only 66 faculty members avail

able in the Division of Liberal Arts, and if the Division in

rank follows that in the entire college, approximately 40%

of these are of professional status.

d. The variety of courses offered is greater than at

Southern and the student has opportunity to obtain a richer

and more diversified background in Liberal Arts than is

possible under Southern’s program.

P ro ceed in g s a t th e A p p e lla te Level

Respondents appealed to the United States Court of

Appeals. That Court on October 28, 1953, with one .iudge

dissenting, reversed the judgment of the District Court on

the ground that the District Judge was without jurisdiction

since this was a case which should have been heard and

determined by a district court of three judges (R. 45).

12

Petitioner applied to this Court for a stay of the judgment

of the Court of Appeals, which application was granted on

November 16, 1953. On January 26, 1954, an order was

issued extending the time for the filing of this petition until

February 16, 1954 (R. 47).

Specifications of Errors to Be Urged

T h e C ourt o f A p p e a ls E rre d :

1. In holding that the case should have properly pro

ceeded pursuant to the requirements of Title 28, United

States Code, Section 2281 et seq. and that, therefore, the

judgment of the District Court was a nullity.

2. In holding that petitioner, in proceeding to hearing

before the District Court, in failing to press his claim in re

the constitutionality of segregation per se and in merely

resting his case upon the inequality of educational facilities

and opportunities, had not waived and abandoned his right

to a hearing before a district court of three judges.

3. In holding in effect that a district judge may not

view the case in its totality and properly refuse to convene

a three-judge court rather than be bound by the mere

formal averments of the complaint.

4. In holding that this case was required to be heard by

a district court of three judges despite the fact that the

basic issue—the right of Negroes to attend Louisiana State

University where other equal educational opportunities

were not available—was not one of first impression in

the court below.

13

Reasons for the Allowance of the Writ

I. Settlement of the question presented here is clearly

necessary because it involves an important question of

federal procedure and practice. In construing Title 28,

United States Code, Section 2281 et seq., this Court has

evolved rules and regulations designed to protect the ad

ministration of state laws against hasty and improvident

invalidation by federal courts and at the same time protect

the public need for efficient administration of the federal

judicial system. Since the problem here raised is likely to

arise in a large variety of cases where injunctive relief

against denial of civil rights is being sought, it should be

determined by this Court.

II. The decision of the Court of Appeals is in conflict

with the basic principles enunciated by this Court defining

the reach and application of Title 28, United States Code,

Sections 2281 and 2284.

A. Title 28, United States Code, Sections 2281 and 2284,

may be properly invoked only when injunctive relief is

sought against state legislative policy as defined in state

constitutions or statutes or in the orders of state adminis

trative agencies on the ground that the state’s policy as thus

defined is unconstitutional under the Constitution of the

United States. Phillips v. United States, 312 U. S. 246;

Oklahoma Natural Gas Co. v. Russell, 261 U. S. 290; Okla

homa Gas & Electric Co. v. Oklahoma Packing Co., 292 U. S.

386; American Federation of Labor v. Watson, 327 U. S.

582; Ex Parte Williams, T il U. S. 267; California Water

Service Co. v. Redding, 304 U. S. 252.

1. No constitutional or statutory provision of the State

of Louisiana forbids the admission of petitioner or of

Negroes similarly situated to Louisiana State University

and Agricultural and Mechanical College on the grounds of

u

race and color. Petitioner cites Article XII, § 1 of the

Constitution which provides as follows:

The educational .system of the state shall consist

of all free public schools, and all institutions of learn

ing supported in whole or in part by appropriations

of public funds. Separate free public schools shall be

maintained for the education of white and colored

children between the ages of six and eighteen years.

It should be noted here that racial segregation is made

mandatory only with respect to free public schools. Obvi

ously, this provision does not include Louisiana State Uni

versity. No reference is made in the above-mentioned con

stitutional provision, or indeed in any state statute which

petitioner’s counsel has been able to find, concerning the

racial composition of the student body at Louisiana State

University and Agricultural and Mechanical College. The

Court’s attention is also directed to Wilson v. Board of

Supervisors, 92 F. Supp. 986, 988 (E. D. La. 1950), appeal

dismissed 340 U. S. 909, in which counsel for both the Negro

applicant and the University conceded and the Court found

that there were no state statutes or constitutional provi

sions which by their terms specifically forbade the admis

sion of Negroes to Louisiana State University and Agri

cultural and Mechanical College. Therefore, it does not

appear that the claim of an unconstitutional legislative

policy forbidding petitioner’s admission to Louisiana State

University because of race as defined in the statutes or

constitutional provisions of the State of Louisiana appear

ing in petitioner’s amended complaint (R. 2, 5) can be

sustained.

2. There is no state legislative i)olicy in the form of

delegated legislation by an administrative body or agency

which prohibits petitioner or other Negroes similarlv situ

ated from being admitted to Ijouisiana State University

15

because of their race and color. Eeference is made in para

graph 8 of the amended complaint to an order of the Board

of Supervisors of Louisiana State University excluding

Negroes from all colleges and undergraduate departments

(R. 5). No proof of the existence of any such order, how

ever, was established by either petitioner or respondents in

any of the proceedings in this case. Petitioner’s rejection

is based by respondents upon an established University

policy, custom and usage (pre-trial depositions, pp. 8, 52).

The closest evidence relative to the existence of such an

order occurs in the following exchange between counsel for

petitioner and the President of the University (depositions,

pp. 8, 9):

“ Q. Are you familiar with the application of the plain

tiff in this action, Mr. Tureaud’s application?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. Will you tell me, advise me, why, what reason he

was refused admission?

A. Because it has been a tradition and a policy of the

university of long standing that we do not admit

Negro students.

Q. Has this policy been the policy set by the Board

of Supervisors?

A. I presume it was set many years ago, I wouldn’t

know, but it has been a policy so long as I have

been there. I have been there about 23 years.

Q. How were you advised of the policy. General

Middleton 1

A. Well, at first it was through custom.

Q. At first it was through custom, and now what is

it on?

A. I think it was 1951 the question of entrance of

Negro students was discussed at a Board meeting.

The Board advised me that when a Negro student

applied for admission, to refuse the admission and

report my actions to the Board.

16

Q. I see. So that in refusing the admission of the

plaintitf in this action, you were acting pursuant

to the order of the Board of Supervisors?

A. That’s right.”

There is no evidence that any formal order barring peti

tioner or other Negroes was ever issued by the Board of

Supervisors. Indeed, the President was pursuing a policy

which had been in existence longer than the 23 years he

had been connected with the University. Unlike Wilson v.

Board of Supervisors, supra, where the Board of Super

visors promulgated and published a specific order barring

Wilson’s admission, no such action was taken here. The

advice of the Board to the President of the University would

not appear to be delegated state legislation of an admin

istrative hoard or agency sufficient to satisfy the jurisdic

tional requirements of Title 28, United States Code, Section

2281 as defined by this Court in Phillips v. United States,

312 U. S. 246, 251.

N B. Even where there is in existence state statutes or

orders of administrative agencies whose constitutionality

is under attack, the jurisdictional requisites sufficient to

properly invoke Title 28, United States Code, Section 2281

are not met unless the claim of unconstitutionality is sub

stantial. Ex Parte Bruder, 271 U. S. 461; Jameson & Co. v.

Morgenthau, 307 U. S. 171; Gully Interstate National Gas

Co., 292 U. S. 16; California Water Service Co. v. Redding,

supra.

Although the averments of unconstitutionality are made

in the amended complaint, proof was directed solely to the

establishment of the fact that petitioner’s rejection was

illegal because he was not able to obtain equal educational

opportunities. The invalidity of the enforcement of segre

gation laws under such circumstances is too firmly settled.

17

see Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U. S. 573; Missouri ex rel. Gaines

V. Canada, 305 U. S. 337; Sipuel v. Board of Regents, 332

U. S. 631, to warrant the needless expense and drain upon

the federal judiciary which is necessarily involved in the

convening of a district court of three judges under the man

date of Title 28, United States Code, Section 2281.

It should be added further that the legal claim litigated

and resolved by the District Court—the right of petitioner

to attend Louisiana State University because the educa

tional opportunities and facilities at Louisiana State Uni

versity were superior to those available at Southern Uni

versity, the state-supported institution for Negroes—was

not a question of first impression. Within the past three

years this same question has been before the District Court,

and on each occasion the Negro applicant has been ordered

admitted to Louisiana State University. See Wilson v.

Board of Supervisors, supra; Foister v. Board of Super

visors, Civil Action No. 937 (E. D. La. 1952); Payne v.

Board of Supervisors, Civil Action No. 894 (E. D. La. 1952).

And, moreover, the basic issue was heard and determined in

the first instance by a district court of three judges in Wil

son V. Board of Supervisors, supra. The basic issue having

been decided consistently with the decisions of this Court,

the necessity for relitigation of each successive claim before

a specially constituted court appears to be not only unneces

sary but wasteful.

C. Where an applicant has properly made a claim of

unconstitutionality sufficient to warrant a hearing and de

termination by a three-judge court, such claim may be aban

doned and the matter properly litigated before a single

district judge. Ex Parte Hobbs, 280 U. S. 168; Edelman v.

Boeing Air Transport, 289 U. S. 249; McCart v. Indianapo

lis Water Co., 302 U. S. 419. The decision of the Court of

Appeals (R. 38-39) concedes that such an abandonment may

be made. Yet the fact that petitioner failed to press his

18

claim as to the iinconstitutionality of segregation ])er se,

and rested his case solely on the ground that his exclusion

from Louisiana State University was a denial of his con

stitutional rights in that there were no other equal facilities

available within the state, was not considered a sufficient

abandonment by the Court of Appeals. As such the deci

sion appears to be in direct conflict with the rationale of

this Court in Ex Parte Hobbs, supra.

U. Title 28, United States Code, Sections 2281 and 2284,

were designed to secure the public interest in a limited class

of cases of special importance and to make certain that state

legislation would not be invalidated by a conventional suit

in equity. In view of the fact that the procedural device

entails a serious drain upon the federal judicial system and

upon the appellate docket of the United States Supreme

Court, the statute has been construed as an enactment of

the greatest technicality which must be strictly and closely

construed. Phillips v. United States, 312 U. S. 246; Rorick

V. The Everglades Drainage List., 307 U. S. 208; Ex Parte

Bransford, 310 U. S. 354.

Under the decision of the Court of Appeals, where the

formal averments of unconstitutionality are made, even

though petitioner may decide to proceed before a single

district judge and rest his suit on a theory of law firmly

foreclosed by decision of this Court, the district judge

nevertheless is without jurisdiction to hear the cause but

must convene a three-judge court. This, we submit, gives

a far more liberal construction of Section 2281 than is war

ranted by the application of principles enunciated in deci

sions of this Court. See Ex Parte Hobbs, supra; Phillips v.

United States, supra; Ex Parte Bransford, supra.

III. There is confusion and conflict among the Courts of

Appeal as to the appropriate application of Title 28, United

States Code, Section 2281 et seq., particularly in the areas

19

of controversy involved in the instant case and this confu

sion and conflict should be I’esolved by this Court.

Illustrative of this confusion and conflict are thj fol

lowing :

A. Under the instant decision, a court of three judges

is required where the necessary formal jurisdictional aver

ments are made in the complaint in spite of the complain

an t’s acquiescence in having a hearing before a single dis

trict judge: (1) even though the suit as pressed merely seeks

admission of a Negro applicant to the state university on

the grounds of absence of equal educational opportunities

and facilities, and (2) in the absence of a state statute or

order of an administrative board or agency which by its

terms prohibits petitioner’s admission to the state univer

sity because of race.

B. The Fourth Circuit in Carter v. School Board of

Arlington County, 182 F. 2d 531 (CA 4th 1950), and in

Corhin v. School Board of Pulaski County, 177 F. 2d 924

(CA 4th 1949), found nothing procedurally amiss in a

conventional suit in equity seeking injunctive relief against

state officers denying to Negroes equal educational advan

tages and opportunities. In both cases a statute of the

State of Virginia expressly required segregation of Negro

and white students at the educational levels involved. Thus,

in both instances the officials were enforcing a policy of

statewide application and concern. See Cleveland v. United

States, 323 U. S. 329. While the complaint in both cases did

not seek to invoke jurisdiction under Section 2281, if the

present decision is correct, cases of this nature must at all

times be brought and heard before a three-judge district

court.

C. In Gray v. Board of Trustees, 97 F. Supp. 463 (Tenn.

1951), vacated as moot, 342 U. S. 517, a complaint properly

drawn to satisfy the jurisdictional prerequisites of Section

20

2281 et seq. was held not to present a substantial claim of

unconstitutionality sufficient to warrant determination by a

court of three judges. Rather the case was treated as one

merely presenting a claim of denial of equal facilities, deter

mination of which was appropriate in an ordinary suit

in equity.

IV. There is a conflict within the Fifth Circuit itself on

this question which should be resolved by this Court. The

district judge and one member of the Court of Appeals in

this case take the view that this is an appropriate case to be

determined by a single judge. Two other judges on the

Court of Appeals have a contrary position. In the same

district court involved here, after Wilson v. Board of Super

visors, supra, had been decided, Foister v. Board of Super

visors, and Payne v. Board of Supervisors, supra, were

decided without the convening of a specially constituted

district court of three judges. In both cases jurisdiction

was invoked under Title 28, United States Code, Section

2281 and injunctive relief was sought to enjoin the officials

of Louisiana State University, respondents here, from re

fusing to admit Negroes to Louisiana State University.

Further, Wichita Falls Junior College v. Battle, 204 F.

2d 632 (pending here on petition for writ of certiorari),

where the complaint sought injunctive relief against the

refusal of the state officials to admit Negroes to the Wichita

Falls Junior College, was held not to be a case requiring

a hearing before a court of three judges. The Wichita

Falls Junior College case cannot be put to one side on

the theory that only local officers were involved. Segrega

tion of the races in the educational institutions of Texas is

a statewide policy, and it was this policy which was being

enforced. As such, without regard to the geographical

limitations set to their authority, the school officials were

state officers within the meaning of Title 28, United States

Code, Section 2281. Spielman Motor Sales Co. v. Dodge,

295 U. S. 89; Watch 1 ower Bible & Tract Society v. Bristol,

21

24 F. Supp. 57 (Conn. 1938), aff’d 305 U. S. 572; Clevelcmd

V. United States, 323 U. S. 329. Henco that decision as well

as the aforementioned Foister and Payne decisions are

inconsistent with the holding in this case.

Conclusion

W heeefoeb, fo r the reasons hereinabove stated, this

petition fo r w rit of certio rari should be granted.

Respectfully submitted,

Robert L. Cabtee,

T huegood Marshall,

Ulysses S. Tate,

A lexander P. T ubbaud,

Counsel for Petitioner.

*

__