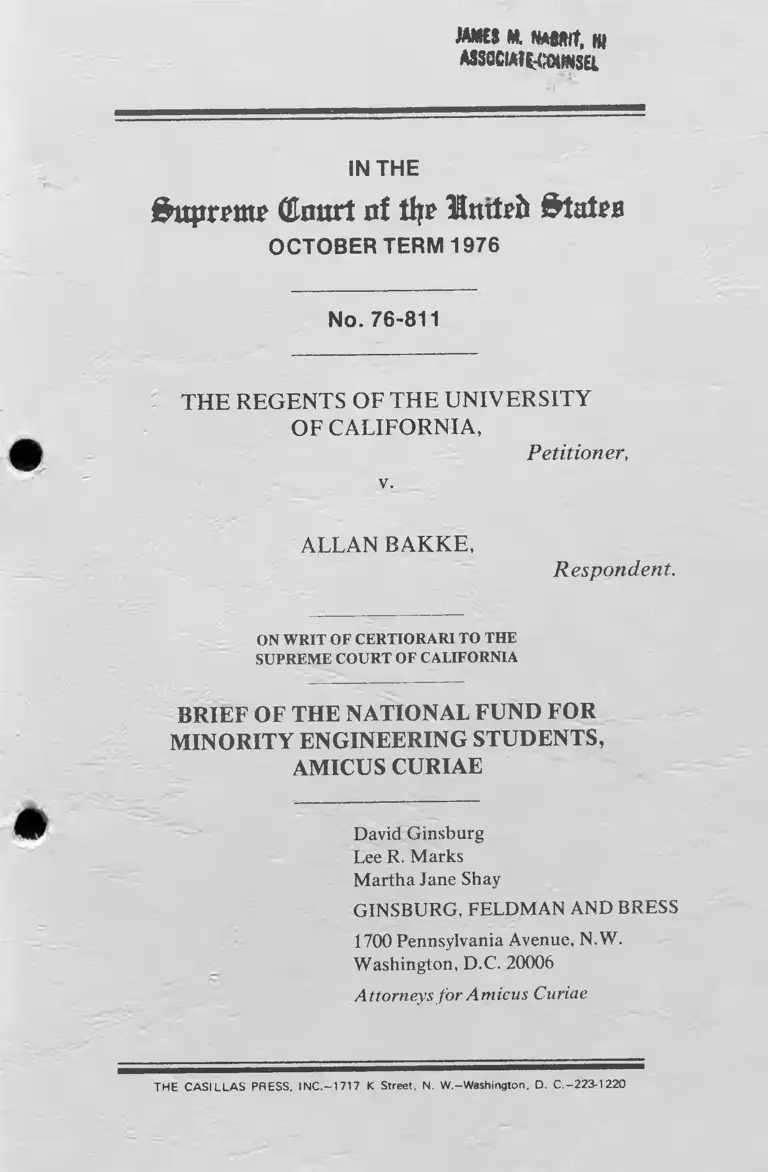

Bakke v. Regents Brief of the National Fund for Minority Engineering Students Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1976

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Bakke v. Regents Brief of the National Fund for Minority Engineering Students Amicus Curiae, 1976. f079bb35-be9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/6db1bb3b-29d6-4a7a-81fc-e952d9754b5a/bakke-v-regents-brief-of-the-national-fund-for-minority-engineering-students-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

M*£$ M. NAMlf, HI

wsocwtMwwsa

IN THE

feprrmr Court of tfyr Hmtrfo Stairs

OCTOBER TERM 1976

No. 76-811

THE REGENTS OF THE UNIVERSITY

OF CALIFORNIA,

v.

Petitioner,

ALLAN BAKKE,

Respondent.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

SUPREME COURT OF CALIFORNIA

BRIEF OF THE NATIONAL FUND FOR

MINORITY ENGINEERING STUDENTS,

AMICUS CURIAE

David Ginsburg

Lee R. Marks

Martha Jane Shay

GINSBURG, FELDMAN AND BRESS

1700 Pennsylvania Avenue, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20006

Attorneys fo r Amicus Curiae

THE CASILLAS PRESS, INC.-1717 K Street, N. W.-Washington, D. C.-223-1220

(i)

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

INTEREST OF THE AMICUS ........................................................ 1

1. Description of NFM ES................ ...................................... 1

a. The NFMES Effort ............................ ................... 1

b. The Background of NFMES. . . .......................... 3

2. NFMES' Concern............................................................ 5

QUESTION PRESENTED ...................... .. ..................................... 8

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT ............. ........................................... 9

ARGUMENT . ................................... ..................... ......................... n

I. There Are No “Racially Neutral Means” of

Reducing the Underrepresentation of

Minorities in Engineering Schools and

in the Engineering Profession.................................... .. . II

II. The Underrepresentation of Minorities in the

Professions Today is the Result of

Unconstitutional Segregative Practices

and L aw s...................................................................... . 1 2

A. Prior to Brown v. Board o f Education,

Southern States Did Not Provide “Separate

But Equal” Education for Blacks .......................... 14

1. Higher education available to Blacks

in the 17 Southern and border states

was qualitatively and quantitatively

inferior to that available to whites ............... 15

a. Quantity of education 15

(ii)

b. Quality of education.............

2. The states employed a variety of

devices and tactics to continue to

deny equal higher education to

blacks.........................................

B. Brown v. Board o f Education Did Not End

Segregative Practices in Higher

Education..................................................

1. Some states refused to recognize that

Brown applied to institutions of higher

education ...........................................

2. A variety of devices were employed

by the states to frustrate the

application of Brown to higher

education ...........................................

a. Certificates.....................................

b. Appropriations..............................

c. Accreditation.................................

d. “Private” character of schools . . .

C. The Segregative Practices in Higher

Education Caused the Underrepresentation

of Minorities in the Professions .................

HI. Affirmative Action Programs Can Be Required

When A State Supported School Has Discrimi

nated Against Minorities ................................

IV. Professional Schools Are Permitted to

Undertake Affirmative Action Programs for a

Limited Time Where Underrepresentation of

Minorities in Such Schools, and in the

Professions, Results from Widespread

Segregative Practices in the P a s t ......................

(iii)

A. Voluntary Efforts to Eliminate the Effects

of Past Discrimination Have Been Supported

by this Court and Are Consistent with

National Policy ...................................................... 29

B. The Professions and Professional Schools

Are National in Character and Are Entitled to

Remedy the Effects of Past de jure

Segregative Practices................................................31

C. The Focus of the Court Below Was Too

Narrow ....................... 32

D. Voluntary Affirmative Action Programs Are

Permitted Even When Past Discrimination

Has Been de facto Rather Than de j u r e ............... 33

E. Once Minorities Have Achieved Equal

Access to Professional Schools and to

the Professions, Affirmative Action

Programs Would no Longer be Permissible

Under the Equal Protection Clause ........................35

CONCLUSION................. 36

(iv)

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases: Page

Addabho v. Donovan, 16 N.Y.2d 619, 261 N.Y.S.2d 68,

209 N. E. 2d 112, cert, denied.

382 U.S. 905(1965).......................................................................... 34

Bakke v. Regents o f the University o f California. 132 Cal. Rptr. 680,

553 P.2d 1152(1976) ........................................... 6,9,10,31,32,34

Battle v. Wichita Falls Junior College District.

101 F. Supp 82 (N.D. Tex. 1951), affd, 204 F.2d

632 (5th Cir. 1953), cert, denied. 347 U.S. 974 (1954)................... 19

Booker v. Board o f Education, 45N.J. 161,212 A.2d 1

(1965)............. .................................................................................. 30

Booker v. Tennessee Board of Education. 240 F. 2d

689 (6th Cir.), cert, denied. 353 U.S. 965 (1957)............................ 21

Bridgeport Guardians Inc. v. Members of Bridgeport

Civil Service Commission. 482 F.2d 1333 (2d Cir. 1973)

cert, denied. 421 U.S. 991 (1975).................................................... 27

Brown v. Board o f Education. 347 U.S. 483

(1954).................................................... 14, 19, 20, 21, 22, 25, 28, 29

Bruce v. Stilwell. 206 F.2d 554 (5th Cir. 1953) 19

Carter v. Gallagher. 452 F.2d 315 (8th Cir. 1971),

cert, denied. 406 U.S. 950(1972).................................................... 9

Cisneros v. Corpus Christi Independent School District.

467 F.2d 142 (5th Cir. 1972), cert, denied.

413 U.S. 920(1973)............................................................................ 13

Constantine v. Southwestern Louisiana Institute. 120

F. Supp. 417 (W.D. La. 1954)......................................................19

Crawford v. Board o f Education. 130 Cal. Rptr. 724,

551 P.2d 28 (1976) ................................................................... 29,32

(v)

Cvpress r. Newport News General and Nonsectarian

Hospital Ass'n, 375 F.2d 648 (4th Cir. 1967) ...................... .. 14

Deal v. Cincinnati Board of Education, 369 F.2d 55

(6th Cir. 1966), cert, denied. 389 U.S. 847(1967) ........................ 33

Florida ex rel. Hawkins v. Board of Control 350

U.S. 413 (1956) .............................................................................. 21

Franklin v. Parker, 223 F. Supp. 724 (M.D. Ala. 1963),

modified. 331 F.2d 841 (5th Cir. 1964)..................... ................... 24

Frasier v. Board of Trustees, 134 F. Supp. 589

(M.D.N.C. 1955), affd, 350 U.S. 979(1956)................................ 20

Gantt i’. Clemson Agricultural College, 320 F.2d 611

(4th Cir.), cert, denied, 375 U.S. 814 (1963)............................ 18, 23

Geier v. Dunn. 337 F. Supp. 573 (M.D. Term. 1972)................. 14, 27

Gomperts v. Chase, 404 U.S. 1237 (1971)'................. • • ■ .................32

Green v. County School Board, 391 U.S. 430 (1968)........... . 14, 27, 28

Guida v. Board o f Education. 26 Conn. Sup. 121, 213

A.2d 843 (1965)............................................... .............................. 34

Guillory v. Administrator o f Tulane University, 203

F. Supp. 855 (E.D. La 1962).......................................................... 24

Hammond v. University of Tampa, 344 F.2d 951 (5th

Cir. 1965)............................................ .......... ......................... .. 25

Holmes v. Danner, 191 F. Supp. 394 (M.D. Ga.). stay

denied. 364 U.S. 939 (1961).... ............. , .......... ......................... 23

Hunt v. Arnold, 172 F. Supp. 847 (N.D. Ga. 1959).......................... 22

Jackson v. Pasadena City School District, 31 Cal. Rptr.

606, 382 P.2d 878 (1963)........................... .................................... 32

Johnson v. San Francisco Unified School District, 339

F. Supp. 1315 (N.D. Cal. 1971), vacated, 500 F.2d 349

(9th Cir. 1974)............................................................ 32

(vi>

Keyes v. School District No. 1. Denver. Colorado.

413 U.S. 189(1973).................................................. 13, 27, 29, 33, 36

Lee v. Macon County Board o f Education. 267 F. Supp.

458 (M.D. Ala.), affd. 389 U.S. 215 (1967)..................................... 21

Lucy r. Adams. 134 F. Supp. 235 (N.D. Ala.), affd.

228 F.2d 619 (5th Cir.), cert denied. 351 U.S. 931

(1955)................................................................................................ 20

Ludley v. Board o f Supervisors. 150 F. Supp. 900

(E.D. La. 1957), af fd. 252 F.2d 372 (5th Cir.),

cert, denied. 358 U.S. 819 (1958).................................................... 22

Lyons v. Oklahoma. 322 U.S. 596 (1944)...................

McCready v. Byrd. 73 A.2d 8 (Md.), cert, denied. 340

U.S. 827 (1950)........................................................

McKissick v. Carmichael. 187 F.2d 949 (4th Cir.),

cert, denied. 341 U.S. 951 (1951)........................................... , . . . 19

McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents for Higher

Education. 87 F. Supp. 526 (W.D. Okla. 1948)............................. 18

McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents for Higher

Education. 339 U.S. 637(1950) ........................ ......................... 18. 25

Meredith v. Fair. 305 F.2d 343 (5th Cir.), cert,

denied. 371 U.S. 828 (1962)......................................................... 23, 24

Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada. 305 U.S. 337

(1938). ..................................................................

Morton v. Mancari. 417 U.S. 535(1974)...............

Mt. Healthy City School District v. Doyle. 97 S. Ct.

568(1977) ....................................................................................... 35

Nardone v. United States. 308 U.S. 338 (1939) .......................... 10. 35

Norris v. State Council o f Higher Education. 327 F.

Supp. 1368 (E.D. Va.), af fd mem.. 404 U.S. 907

(1971) ........................! ................................................................... 27

18,19.31

.........14

(vis)

North Carolina State Board o f Education v. Swann.

402 U.S. 43(1971) ......................................................................... 27

Offermann v. Nitkowski. 378 F.2d 22 (2d Cir. 1967)........................ 33

Parker v. University o f Delaware, 75 A.2d 225

(Ch. Del. 1950)................................................................................ 19

Pennsylvania Human Relations Commission v. Chester

School District. 427 Pa. 157, 233 A.2d 290 (1967)........................ 34

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537 (1896)............................................. 14

Porcelli v. Titus, 431 F.2d 1254 (3d Cir. 1970), cert.

denied. 402 U.S. 944 (1971)............................................................ 9

Quality Education for All Children. Inc. v. School

Board, 362 F. Supp. 985 (N.D. 111. 1973)....................................... 34

Reeves v. Eaves. 411 F. Supp. 531 (N.D. Ga. 1976)................... 10, 35

Rios v. Enterprise Assn. Steam Fitters Local 638

501 F.2d 622 (2d Cir. 1974)............................................................ 28

Robinson v. Lorillard Corporation, 444 F.2d 791

(4th Cir.), cert, dismissed. 404 U.S. 1006 (1971)............................ 36

Serna v. Portales Municipal Schools, 499 F.2d 1147

(10th Cir. 1974) .'.......................................................... 13

Sipuel v. Board o f Regents. 332 U.S. 631 (1948) ........................ 18, 19

Soria v. Oxnard School District Board o f Trustees.

328 F. Supp. 155 (C.D. Cal. 1971), vacated. 448

F.2d 579 (9th Cir. 1973), cert, denied, 416 U.S.

951 (1974) .............................................................. 32

Spangler v. Pasadena City Board o f Education. 311

F. Supp. 501 (C.D. Cal. 1970)........................................................ 32

Springfield School Committee v. Barksdale, 348 F.2d

261 (1st Cir. 1965)............................................................................ 34

(viii)

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenberg Board o f Education

402 U.S. 1 (1971)........................................... 9. 14, 27. 28. 29, 31.35

Sweatt v. Painter. 339 U.S. 629 (1950)................................................19

United Jewish Organization v. Carey. 45 U.S.L.W.

4221 (March 1. 1977)............................................................... 27,34

United States v. Texas Education Agency. 467

F.2d 848 (5th Cir. 1972) ................................................................. !3

Vetere v. Allen. 15 N.Y. 2d 259, 258 N.Y.S. 2d 677, 206

N.E. 2d 174, cert, denied. 382 U.S. 825(1965).............................. 34

Vulcan Society v. Civil Sendee Commission. 490

F.2d 387 (2d Cir. 1973)................................................................. 28

Wanner v. County School Board o f Arlington County.

357 F.2d 452 (4th Cir. 1966) ........................................................ .. 33

Wilson v. Board o f Supervisors. 92 F. Supp. 986

(E.D. La. 1950). affd. 340 U.S. 909(1951).....................................19

Wong Sun v. United States. 371 U.S. 471 (1963).............................. 33

Statutes and Regulations:

42U.S.C. §2000e . . ......................................... 6

42 U.S.C. §2000e-2 ............................................................................ 6

41 C.F.R. 60-2 .......................................................................................34

Other Authorities:

S. Rep. No. 872. 88th Cong., 2d Sess. (1964).....................................30

H.R. Rep. No. 914, 88th Cong., 2d Sess. (1964)................................ 30

U.S. Bureau of the Census, Census o f

Population: 1940 .......................................................... Appendix A

fix)

U.S. Bureau ot'the Census. Census o f

Population: 1950 .......................................................... Appendix A

U.S. Bureau ot'the Census, Census o f

Population: 1960 ........................................................... Appendix A

U.S. Bureau of the Census, Statistical Abstract:

1960 (81st Ed. 1960) ..................................................................... 15

U.S. Bureau of the Census. U.S. Census o f

Population: 1970 ................................................ . 13. 25. Appendix A

U.S. Bureau of the Census. Statistical Abstract o f the

United States: 1970 (91st ed. 1970).......................... - ................... 25

U.S. Office of Education, National Sunny of the

Higher Education o f Negroes. General Studies of

Colleges for Negroes (1942)......................................... 15, 16, 17, 18

J. Auerbach, Unequal Justice (1976) ................... ........................... 14

K. Davis, Administrative Law Text (3d ed. 1972) ............................. 12

R. Kiehl, Opportunities for Blacks in the Profession

(>l Engineering (1970)............................................................... 11, 12

H. Morais. The History o f the Negro in Medicine.

(1967) .......................................................... ............................ !4- 17

J. Stanford Smith. Address to the Engineering

Education Conference, July 25. 1972 .......................... ................. 4

J Weinstein & M Berger, Weinstein's Evidence (1975)................... 12

J. Wigmore. Evidence (3d ed. 1940)..................................... 12

Minorities in Engineering: A Blueprint for Action

(1974)............................................................................ ■ • 4, 5, 12. 13

New York Times. April 3. 1977 .................................................... • • 12

IN THE

&uprm? (Emtrt of tlf? lotted &tat?B

O C T O B E R TERM 1976

No. 76-811

THE REGENTS OF THE UNIVERSITY

OF CALIFORNIA,

Petitioner,

v.

ALLAN BAKKE,

Respondent.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

SUPREME COURT OF CALIFORNIA

BRIEF OF THE NATIONAL FUND FOR

MINORITY ENGINEERING STUDENTS,

AMICUS CURIAE

INTEREST OF THE AMICUS

1. Description of NFMES

a. The NFMES Effort

The National Fund for Minority Engineering Students

(“NFMES”) is a non-profit corporation organized in Oc

tober 1974

to increase the participation of underrepresented,

disadvantaged minorities (including Blacks, Puer-

2

to Ricans, Mexican-Americans, and American In

dians) in the engineering profession by enabling

members of such minorities to acquire an

engineering education. . . . Articles of In

corporation, A rticle Third.

NFMES raises and provides scholarship funds to

engineering schools for the support of minority engineering

students. Some 70 engineering schools across the country

receive funds from NFMES. Participating schools must

agree to increase recruiting activities among minority

groups, to meet agreed upon minority enrollment goals, to

use NFMES funds to supplement rather than to replace

funds normally used to help minority engineering students,

to provide services for minority students, and to report

periodically to NFMES.

The participating engineering schools select the students

who are to receive scholarship awards; these students must

be academically qualified, and they must be selected from

the four target minorities. All scholarships are based on

need.

In 1976-1977, the first full year of operation, NFMES is

providing scholarship assistance for 718 students, which

represents about five percent of all minority engineering

students in this country and about 10 percent of minority

engineering freshman. In 1977-1978, NFMES will continue

to support these 718 students and, in addition, will provide

assistance for approximately 400 more students. NFMES

has raised $2.3 million in the past two and a half years, has

pledges for an additional $2.2 million, and expects to raise

$2.75 million in contributions and pledges annually. About

80% of the contributions and pledges come from large in

dustrial corporations; the balance comes from foundations

and individuals.

3

b. The Background of NFMES

NFMES represents a nationwide effort by United States

industry1 to increase the number of minority engineers. It

was formed because of deep concern about the lack of

minority engineers.

Addressing the Engineering Education Conference in

1972, J. Stanford Smith, Chairman of International Paper

Company, said

Of the 43,000 engineers graduated in 1971, only

407 were Black and a handful were other

minorities or women. One percent. It takes about

fifteen to twenty-five years for people to rise to top

leadership positions in industry. So if industry is

getting one percent minority engineers in 1972,

that means that in 1990, that’s about the propor

tion that will emerge from the competition to top

leadership positions in industry. . . .

Gentlemen, this is a formula for tragedy. Long

before the year 1990, a lot of minority people are

going to feel that they have been had. Already

there are angry charges of discrimination with

regard to upward mobility in industry, whereas

the real problem, clearly visible today, is that

1 In addition to trustees from the academic world and from minority

groups, the Board of Trustees includes the Chairmen of the Boards of

American Can Company, The Bechtel Group, General Electric Com

pany. General Motors Corporation, The Goodyear Tire & Rubber

Company, Hewlett-Packard Company, International Business Ma

chines Corporation, International Paper Company, Rockwell In

ternational Corporation, Standard Oil Company of California, Union

Carbide Corporation, and United States Steel Corporation; it also in

cludes the Presidents of E. I. du Pont & Nemours & Company and In

ternational Harvester Company and the Executive Vice President of

American Telephone and Telegraph Company. Trustees personally at

tend Board meetings, solicit funds, and are otherwise involved in NF

MES affairs.

4

there just aren’t enough minority men and women

who have taken the college training to qualify for

professional and engineering work. . . .

To put the challenge bluntly, unless we can start

producing not 400 but 4,000 to 6,000 minority

engineers within the decade, industry will not be

able to achieve its goals of equality, and the

nation is going to face social problems of un

manageable dimensions.2

In response to this problem, numerous groups focused on

the need to increase minority representation in engineering.

In December 1972 the Engineers’ Council for Professional

Development co-sponsored with other organizations a task

force known as the Minority Engineering Education Effort ;

the task force called for a 10 to 15-fold increase in minority

engineering graduates by the mid-1980s. In May 1973 the

National Academy of Engineering sponsored a symposium

which called for a similar increase. The Academy sub

sequently established its Committee on Minorities in

Engineering, and helped establish the National Advisory

Council for Minorities in Engineering.

In late 1973, as the next step, the Alfred P. Sloan Foun

dation encouraged and funded the formation of an ad hoc

task force to recommend ways to increase the number of

minority engineers. The 17 members of the task force — of

ficially named The Planning Commission for Expanding

Minority Opportunities in Engineering — were drawn from

universities, industry, professional associations, and

scholarship programs. Their efforts extended over seven

months and resulted in a report entitled Minorities in

Engineering: A Blueprint for Action, (1974) [hereinafter

cited as Sloan Report].

2Address by J. Stanford Smith to the Engineering Education Con

ference, Crotonville, N.Y., July 25. 1972. Mr. Smith has been Chairman

of the Board of Trustees of NFMES since NFMES was organized.

5

The Sloan Report concluded that the

single most important barrier today to increasing

minority participation in engineering is the lack

of adequate financial aid for minority college

students. At 12.

The Sloan Report recommended

the establishment of a single national organi

zation to raise and distribute essential new funds

for financial aid to minority engineering college

students. Id.

NFMES was organized by the National Academy of

Engineering (through its Committee on Minorities in

Engineering), on the recommendation of the National Ad

visory Council for Minorities in Engineering and the Sloan

Foundation, as the “single national organization” called

for by the Sloan Report.

The findings of the Sloan Report, and its recom

mendations, were thus the result of a sustained

examination of the lack of minority representation in

engineering — and of ways to remedy it — by industry, the

profession, educators, and minorities.

2. NFMES’ Concern

The specific question before this Court is whether a state

medical school violates the Equal Protection Clause by set

ting aside places in its entering class to be filled by minority

applicants under a special admissions program. In light of

the extensive efforts to reduce the underrepresentation of

minorities in higher education, the case has obvious im

portance for colleges and universities throughout the

United States. We assume that Petitioners and other amici

will address the implications for admissions programs, and

for higher education generally, of affirming the opinion

below.

NFMES is concerned that affirmance will substantially

hamper and delay efforts to increase the number of

6

minority engineers. These efforts are important not only to

achieve parity in the professions but because engineering is

one route to top management positions in industry. If

minorities are to be adequately represented in the top

positions of major corporations, there must be an adequate

number of minority engineers. Moreover, a growing pool of

qualified minority engineers is important for the continued

vitality of industry. Large corporations are hiring minority

engineers in rapidly increasing numbers; they believe that it

is right to do so, and in addition they are frequently

obligated to do so.3 Qualified minority engineers must be

trained quickly enough to meet the demand. As indicated

above, it is the consensus of industry leaders, engineers,

educators, and others that only through NFMES and like

programs can the demand be met.

Even though we can distinguish the NFMES effort from

the University of California’s special admissions program,4

affirmance of the opinion below would almost surely

prevent NFMES from achieving its objectives. Even if the

Court decided the case on the narrowest possible grounds,

there would be a period of uncertainty during which univer

sity administrators and corporate donors might un

derstandably be cautious about contributing to or working

with any programs that used race as a selection criterion.

3See 42 U.S.C. §2000e; 42 U.S.C. §2000e-2; 41 C.F.R. 60-2.

4Because the NFMES scholarship funds are generated solely to assist

minority engineering students, and must be used to supplement rather

than to replace existing scholarship funds, the NFMES program does

not “have the effect of depriving persons who were not members of a

minority group of benefits which they would otherwise have enjoyed.”

Bakke v. Regents o f the University o f California, 132 Cal. Rptr. 680,

688, 553 P.2d 1152, 1160 (1976). Similarly, the lack of access to a

specific source of financial assistance “cannot be equated with the ab

solute denial of a professional education." Bakke. 132 Cal. Rptr. at

689, 553 P.2d at 1161. Nonetheless, NFMES scholarships are available

only to members of four minority groups.

7

During this period, NFMES and similar programs would

be in grave danger of atrophying.

NFMES could avoid the constitutional problems raised

by this case in either of two ways: first, it could award

scholarships to students directly, without involving

engineering schools; and second, it could award scholar

ships to culturally or economically deprived engineering

students of any race — and hope that enough of them were

members of the four target minorities to justify the

program. Neither way is satisfactory.

By working through engineering schools, NFMES

stimulates institutional changes in minority recruitment,

enrollment, educational support programs, and financial

aid, to help ensure a permanent increase in the pool of

minority engineering students. Otherwise, NFMES’

scholarship dollars might be nothing more than a sub

stitute for existing resources. NFMES also relies on the

expertise of engineering schools in selecting qualified stu

dents and in disbursing funds. An essential part of the

NFMES program would thus be sacrificed if NFMES had

to abandon its current relationships with engineering

schools.

Given the objectives and origins of NFMES, it would be

difficult to open the program to disadvantaged persons

generally. The engineering profession has traditionally at

tracted people from low socio-economic backgrounds, with

the exception of minorities. Thus, the fundamental con

cerns that NFMES addresses are racial concerns, not

cultural or economic concerns. And it would dissipate

limited resources to cast a broad net when the real ob

jectives are limited. What may give rise to a “formula for

tragedy,” to “social problems of unmanageable dimen

sions,” is the absence of Blacks and other minority

engineers, not the absence of engineers from backgrounds

of poverty.

8

NFMES looks to 1990 and beyond and to fair op

portunities for all to join the top ranks of industry, govern

ment, and the professions. The program attempts to

forestall those who would say “we have been had” and to

offer meaningful opportunity — now. It is part of a nation

al effort, joined in by schools and universities, professional

groups, industry, government, and others to redress the im

balances caused by 200 years of unlawful discrimination.

Those who argue that the Constitution bars this effort

argue that the Constitution must be color-blind or racially

neutral; so it must be, in time. For the better part of 200

years, however, the Constitution was not color-blind or

racially neutral. It was relied upon to sanction the

discriminatory practices that caused the under

representation of minorities in higher education and the

professions. It would be the ultimate irony to perpetuate

the unequal condition of Blacks and other minorities now in

the name of a color-blind Constitution. Discrimination on

account of race is a shadow that we must remove. Once it is

removed, the Constitution should indeed be color-blind.

But if we determine to be color-blind now, while the effects

of past discrimination are still pervasive, and to rely solely

on “racially neutral means” to remove these effects, we are

likely to need more time — measured in decades — than we

can safely assume we have.

The parties have consented to the filing of this brief, as

evidenced by letters on file with the Court.

QUESTION PRESENTED

Whether the Equal Protection Clause prohibits state

supported professional schools from voluntarily using

preferential admissions programs to reduce the un

derrepresentation of minorities in such schools and in the

professions, when such underrepresentation was caused by

past de jure segregative practices engaged in by others, at

least until the taint of the past segregative practices is

dissipated.

9

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

If there were evidence of past discrimination at the

medical school of the University of California at Davis, this

would be a routine discrimination case. The courts have not

hesitated to order that school boards, universities, or em

ployers implement affirmative action programs where there

has been a showing of past discrimination. Carter v,

Gallagher, 452 F.2d 315 (8th Cir. 1971), cert, denied, 406

U.S. 950 (1972); Porcelli v. Titus, 431 F.2d 1254 (3d Cir.

1970), cert, denied, 402 U.S. 944 (1971).

In this case there is no showing of past discrimination by

Petitioner, and no effort to compel Petitioner to take

remedial action. Instead there is a voluntary effort by

Petitioner to participate in a nationwide effort to reduce the

underrepresentation of minorities in professional schools

and in the professions caused by past unlawful conduct

engaged in generally, although not by Petitioner. As the

dissenting opinion below noted

It is anomalous that the Fourteenth Amendment

that served as the basis for the requirement that

elementary and secondary schools could be

compelled to integrate should now be turned

around to forbid graduate schools from volun

tarily seeking that very objective. Bakke, 132 Cal.

Rptr. at 719, 553 P.2d at 1191. (Emphasis in

original).

We argue below that the Equal Protection Clause does not

prohibit such voluntary efforts. The argument is, we

believe, squarely before this Court for the first time,

although it finds strong support in Swann v. Charlotte-

Mecklenburg Board of Education, 402 U.S. 1, 16(1971).

We also believe that this Court can decide the case before

it on grounds that fall squarely within prior decisions. The

court below acknowledged that a racial classification does

not violate the Equal Protection Clause if the classification

serves a “compelling state interest” and there are no

10

reasonable alternative ways to meet that interest. Bakke,

132 Cal. Rptr. at 690. 553 P.2d at 1162.5 The California

Supreme Court assumed that the University’s objectives

“met the exacting standards required to uphold the validity

of a racial classification insofar as they establish a com

pelling governmental interest.” Bakke, 132 Cal. Rptr. at

693, 553 P.2d at 1165. The court rejected the special ad

missions program on the ground that the University had

failed to establish that it could not serve those objectives in

alternative ways. We argue below, as others will un

doubtedly argue, that no alternatives are available. If this

Court accepts the factual proposition that only through

preferential programs like the one before it can the un

derrepresentation of minorities in higher education and the

professions be reduced within an acceptable period of time,

it can and should reverse the court below on the basis of

established case law.

Finally, when there has been an unlawful invasion of a

constitutionally protected right, remedial steps must be

taken until the connection between the invasion and the

result “becomes so attenuated as to dissipate the taint” .

Nardone v. United States, 308 U.S. 338, 341 (1939). Af

firmative action programs should thus be permitted only

until the conditions caused by past discrimination have

been ameliorated. When minorities have a meaningful op

portunity to train for and enter the practice of medicine,

law, engineering, architecture, pharmacy, etc., special ad

missions programs and similar affirmative action programs

will no longer be necessary or constitutionally permissible.

Reeves v. Eaves, 411 F. Supp. 531,534 (N.D. Ga. 1976).

5There is of course serious question whether the court below was

correct in applying the “compelling state interest" test rather than the

“rational basis” test. We accept arguendo the application of the “com

pelling state interest” test.

11

ARGUMENT

1. THERE ARE NO "RACIALLY NEUTRAL MEANS” OF

REDUCING THE UNDERREPRESENTATION OF

MINORITIES IN ENGINEERING SCHOOLS AND IN

THE ENGINEERING PROFESSION.

The court below held that increasing the number of

minority students in professional schools6 serves a “com

pelling state interest.’’ At least with respect to engineering,

it is the considered judgment of industry, educators, and

the profession that special programs, employing race as a

selection criterion, are necessary to reduce under

representation.

As noted, the organization of NFMES in 1974 was the

result of a long and concerted effort by industry, educators,

and the engineering profession to deal with the un

derrepresentation of minorities in engineering. A 1970

report prepared for the Manpower Administration of the

United States Department of Labor found that

time alone is not increasing the under

representation of the U.S. black in the engin

eering profession. During the last eight years

there has been virtually no increase in the per

centages of blacks in engineering education ex

cept for special programs that some colleges

have instituted to encourage and retain these

students. R. Kiehl, Opportunities for Blacks in

The Profession of Engineering, 13-14(1970). (Em

phasis added).

In contrast to the extraordinary shortage of admissions

places available generally in law and medicine7 “ftjhere is

sufficient room in engineering schools that minority

enrollment could be multiplied several times without taxing

6Only medical schools were at issue but similar reasoning applies to

law, engineering, and other professional schools.

7Some 3,000 applicants competed for 100 admissions places in the

medical school of the University of California at Davis.

12

the schools’ capacity,” Sloan Report 2, and “[t]here seems

to be no question but that there are widespread education

and employment opportunities for blacks in engineering

and in technicians’ work,” Kiehl, supra, at 14.

Thus, despite the suggestion of the court below that un

derrepresentation might be ameliorated by increasing the

number of places available in the medical school, at least

in engineering the underrepresentation of minorities is

not the result of the absence of admission places8 or job op

portunities. With an abundance of both, there was “vir

tually no increase in the percentages of blacks in

engineering education except for the special programs that

some colleges have instituted to encourage and retain these

students.” Id.

The Sloan Report found that “the single most important

barrier today to increasing minority participation is the

lack of adequate financial aid for minority college stu

dents”. Sloan Report 12. The task force responsible for

the Sloan Report was drawn from industry, universities,

minority groups, and the profession; its considered

judgment should not lightly be disregarded. Cfi J. Wein

stein & M. Berger, Weinstein's Evidence §702[02] (1975) J.

Wigmore, Evidence §1923 (3d ed. 1940); K. Davis, Ad

ministrative Law Text §502 at 127, §14.11 at 287 (3d ed.

1972).

II. THE UNDERREPRESENTATION OF MINORITIES IN

THE PROFESSIONS TODAY IS THE RESULT OF UN

CONSTITUTIONAL, SEGREGATIVE PRACTICES

AND LAWS.

That minority groups are numerically underrepresented

in the professions is beyond question. In 1970 Blacks,

Chicanos, Puerto Ricans, and American Indians con

stituted 2.8% of the engineers in the United States and

8We note that Mr. Bakke has a degree in engineering. N.Y. Times.

April 3, 1977, §6 (Magazine), at 43, col. 1.

13

14.4% of the total population. Sloan Report 1. Blacks alone

accounted for about 11% of the total population in 1970.9

but only 2.06% of all architects, 1.25% of all lawyers and

judges, 2.04% of physicians, 2.46% of dentists, 2.14% of

pharmacists, and 1.12% of engineers. See page 26. infra.

If this were the result of accident, or the free choice of

Blacks and other minorities to eschew the professions, no

constitutional questions would arise. Of course, it is not. In

this section, we show that underrepresentation of minorities

in the professions is the result of de jure segregative prac

tices that effectively barred minority groups from higher

education, including professional schools, until recently.

We deal primarily with Blacks because the case law and

the data deal primarily with Blacks. Other minorities have

suffered the same unconstitutional privations. This Court

has held that “Hispanos constitute an identifiable class for

purposes of the Fourteenth Amendment” and noted that

“Hispanos suffer from the same educational inequities as

Negroes and American Indians.” Keyes School District

No. 1, Denver, Colorado. 413 U.S. 189, 197 (1973). See Ser

na v. Portales Municipal Schools, 499 F.2d 1147 (10th Cir.

1974); United States v. Texas Education Agency, 467 F.2d

848 (5th Cir. 1972); Cisneros v. Corpus Christi Independent

School District, 467 F.2d 142 (5th Cir. 1972), cert, denied,

413 U.S. 920 (1973). Upholding an employment preference

in favor of Indians, this Court recently said:

The Indians have not only been thus deprived of

civic rights and powers, but they have been largely

deprived of the opportunity to enter the more im

portant positions in the service of the very bureau

which manages their affairs. Theoretically, the In

dians have the right to qualify for the Federal civil

"U.S. Bureau of the Census. Census o f Population: 1970. GeneraI

Population Characteristics. Final Report PCtll-Bl United States Sum-

man’. 1-293, Table 60.

14

service. In actual practice there has been no

adequate program of training to qualify Indians

to compete. . . . 78 Cong. Rec. 11729 (1934) as

cited in Morton v. Mancari, 417 U.S. 535, 544

(1974).

We deal primarily with higher education because college

and professional training are prerequisites for a pro

fessional career. Segregation in higher education, how

ever, is only part of the story. Segregative practices in the

professions themselves contributed to the under

representation of minorities.10 And there is no need to re

mind this Court of the measures by which the Southern

States — in which the vast majority of Blacks lived until

recently — unlawfully prevented Blacks from obtainining

elementary and high school educations.

It is not an answer to say that segregative practices

among schools of higher education have ceased. This Court

has recognized that inequalities produced by unlawful

segregation are not remedied solely by cessation of the

unlawful practices. Green v. County School Board, 391

U.S. 430 (1968); Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of

Education, 402 U.S. 1 (1971); Geier v. Dunn, 337 F. Supp.

573 (M.D. Tenn. 1972).

A .Prior to Brown v. Board o f Education, Southern

States Did Not Provide “Separate But Equal”

Education for Blacks.

Prior to Brown v. Board o f Education, 347 U.S. 483

(1954), the law required “separate but equal” educational

facilities. Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537 (1896). The

evidence is conclusive that the education available to

Blacks, at least in the District of Columbia and the

'"See Cypress v. Newport News General and Nonsectarian Hospital

Ass'n, 375 F.2d 648 (4th Cir. 1967); H. Morais, The History’ of the

Negro in Medicine. 135, 147, 153 0 967); J. Auerbach, Unequal Justice.

65-66,210-17 0976).

15

Southern and border states, was separate but not equal. In

1940 some 80% of all Blacks lived in these states; 70% of all

Blacks lived in these states in the 1950’s.11 Segregative

practices in the South thus affected a substantial majority

of all Blacks.

1. Higher education available to Blacks in the 17 Southern

and border states was qualitatively and quantitatively in

ferior to that available to Whites.

In 1942 the United States Office of Education issued a

study documenting the quantity and quality of higher

education available to Blacks. II National Survey o f the

Higher Education o f Negroes. General Studies o f Colleges

for Negroes (U.S. Office of Education 1942) [hereinafter

cited as Survey]. The Survey focused on education op

portunities available in 1940 in the District of Columbia

and in the 17 Southern and border states in which the vast

majority of Blacks lived.12

In some of these states, segregation of the races in

separate schools was mandated by the state constitution; in

others, it was statutory; in at least four states it was a crime

to allow Blacks and Whites to share the same classrooms.

a. Quantity of education

The Survey noted that

No state makes adequate provision, when

measured in terms of its provision for white per-

"U.S. Bureau of the Census, Statistical Abstract of the United

States: I960, 30, Table 27 (81st ed. 1960) for figures from which per

centages were computed. In addition to the District of Columbia, the

states included are: Alabama, Arkansas, Delaware. Florida, Georgia,

Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maryland, Mississippi, Missouri, North

Carolina, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Virginia, and

West Virginia.

1JThe Survey noted that few Negroes attended northern colleges and

universities, that large numbers of northern Negroes went south to at

tend college, and that few southern Negroes attended northern schools.

Survey 79. Table 56; 82.

16

sons, for the graduate education of Negroes, . . .

Professional offerings are virtually nonexistent in

public institutions for Negroes and are available

in only a few private institutions. No state which

provides racially separate facilities at the level of

higher education provides adequate facilities for

the professional education of its Negro citizens.

At 21-22.

In 1940 only five private and seven public institutions

provided graduate or professional training for black

students in the 17 Southern and border states and in the

District of Columbia. The 12 institutions accommodated

1,864 students. In 11 states no graudate work wras available

in black institutions. In 16 states a law curriculum was of

fered for Whites, but it was available at black institutions

in only two states. Similarly, in 13 of the 17 states the study

of medicine was available at white institutions, but was of

fered at black institutions in only two states.

With respect to engineering, the Survey13 found that for

the 1939-40 academic year

—190 fields of specialization in engineering were

available in all-white institutions, public and

private, but only 10 fields of specialization were

available in black-only institutions.

—Each state and the District of Columbia offered at

least three and as many as 21 different fields of

engineering specialty in white-only institutions.

The median offering per state was nine.

—13 of the 17 states offered no engineering training

for Blacks. Private institutions in the District of

Columbia and Alabama offered three and two

fields of specialization respectively. Public in

stitutions in North Carolina offered three,

Oklahoma one, and Texas one.

" S i u t c y 10. Table 6.

17

The Survey noted that

in only 1, or possibly 2, of the [black-only] in

stitutions which list fields of specialization in

engineering are these curricula standard

engineering curricula. In the other institutions

these fields are chiefly for teacher training or

trade training.”14 Survey 13 n.3.

Graduate work in engineering was available to Whites in

each of the 17 states in at least three and in as many as 18

fields of specialization. Survey 14, Table 7. No graduate

work in engineering was available to Blacks. Id.

In the fall of 1947, only some 600 of the country’s 25,000

medical students were Black. There were only two black

medical schools in the country, Howard in the District of

Columbia and Meharry in Tennessee. Lack of interest in at

tending medical school was not the cause of the un

derrepresentation of Blacks. Some 1,351 applicants com

peted for 74 places at Howard; Meharry enrolled 55 of its

800 applicants. H. Morais. The History o f the Negro in

Medicine 94 (1967).

b. Quality of education

The Survey also documented the “sharp” differences in

the quality of education offered to Blacks and Whites; it

concluded that “in each of the States the public institutions

for Negroes are inferior, qualitatively, to the public in

stitutions for white persons.” Survey 22.

l4The limited offerings in engineering were not unique. For instance,

in commerce, whose primary function the report described as

“preparing] individuals for participation in business and commercial

pursuits,” the following fields were not available to Blacks: Ac

counting, advertising, banking and finance, business statistics, clothing

and textile merchandising, engineering and business administration,

management, manufacturing, marketing, personnel, administration,

public utilities, real estate, retailing, foreign service. Sun’ey 11-12.

18

Accreditation by the Association of American Univer

sities (“AAU”) was the chief measure of the quality of in

struction. In 1938, 79 White-only institutions of higher learn

ing in the 17 Southern and border states and the District

of Columbia were accredited by the AAU; there was at least

one public and one private white institution accredited in

each state. The AAU had accredited only two private in

stitutions for Blacks, and no public institutions for Blacks,

in any of the 17 states or the District of Columbia. Survey

16, Table 9.

2. The states employed a variety of devices and tactics to con

tinue to deny equal higher education to Blacks.

In 1938 this Court held that if a state offered a specific

field of graduate or professional study to Whites, it had to

provide a substantially equal opportunity to Blacks, either

by providing equivalent graduate or professional schools

for Blacks or by permitting Blacks to attend white schools.

Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 U.S. 337 (1938).

Gaines also held unconstitutional the widespread practice

of giving black residents tuition grants to attend out-of-

state schools when a course of study available to white

residents was not available at black institutions.

Although Gaines was decided in 1938, out-of-state tuition

programs continued into the 1960’s. See Gantt v. Clemson

Agricultural College, 320 F.2d 611 (4th Cir.), cert, denied

375 U.S. 814 (1963). And despite the clear holding of

Gaines, it took two decisions of this Court and one district

court decision to persuade the University of Oklahoma to

admit Blacks on an equal basis to its law and graduate

schools when the state did not offer equivalent courses in its

Black schools. Sipuel v. Board o f Regents, 332 U.S. 631

(1948); McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents for Higher

Education, 87 F. Supp. 526 (W.D. Okla. 1948); McLaurin

v. Oklahoma State Regents for Higher Education, 339 U.S.

637(1950).

19

To avoid Gaines and Sipuel, the governors of 14 states

entered into an interstate compact for regional educa

tion.'5 The compact created jointly owned and oper

ated professional educational institutions in the profes

sional, technological, and scientific fields. The theory was

that if a state could not provide training for Blacks within

its borders, it could satisfy its constitutional obligations

by contracting for that training at an institution within

the 14-state compact. The compact was struck down in

McCready v. Byrd, 73 A.2d 8 (md.), cert, denied, 340 U.S.

827(1950).

In the early 1950’s, the courts found, time and again,

that Blacks were not being provided with equal opportuni

ties for higher education. Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U.S. 629

(1950) ; Bruce v. Stilwell, 206 F.2d 554 (5th Cir. 1953);

McKissick v. Carmichael, 187 F.2d 949 (4th Cir.), cert,

denied, 341 U.S. 951 (1951), Constantine v. Southwestern

Louisiana Institute, 120 F. Supp. 4177 (W.D. La. 1954);

Battle v. Wichita Falls Junior College District, 101 F. Supp.

82 (N.D. Tex. 1951), affd, 204 F.2d 632 (5th Cir. 1953), cert,

denied, 347 U.S. 974 (1954); Wilson v. Board o f Super

visors. 92 F. Supp. 986 (E.D. La. 1950), affd, 340 U.S. 909

(1951) ; Parker v. University o f Delaware, 75 A.2d 225 (Ch.

Del. 1950).

B. Brown v. Board o f Education Did not End

Segregative Practices in Higher Education.

Brown v. Board of Education did not put an end to the

segregative practices that effectively denied professional

,5Aiabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Maryland,

Missisippi, North Carolina, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Tennessee,

Texas, Virginia, and West Virginia were the original signatories to the

compact. Kentucky joined later.

20

training to Blacks.15 If it had, the taint from the practices

before Brown might well have been dissipated by now.

1. Some states refused to recognize that Brown applied to in

stitutions of higher education.

In 1955 three Negroes were denied admission to the

University of North Carolina. By resolution, the University

reaffirmed its policy of denying admission to Blacks. The

students filed suit; the court rejected the University’s con

tention that Brown “did not decide that the separation of

the races in schools on the college and university level is

unlawful”. Frasier v. Board o f Trustees, 134 F. Supp. 589,

592 (M.D. N.C. 1955), affd, 350 U.S. 979 (1956). After

quoting extensively from the Brown decision the court con

cluded:

In view of these sweeping pronouncements, it is

needless to extend the argument. There is nothing

in the quoted statements of the court to suggest

that the reasoning does not apply with equal force

to colleges as to primary schools. Indeed, it is fair

to say that they apply with greater force to stu

dents of mature age in the concluding years of

their formal education as they are about to en

gage in the serious business of adult life. Frasier

v. Board o f Trustees, 134 F. Supp. at 592-93.

See Lucy v. Adams, 134 F. Supp. 235, 238 (N.D. Ala.),

affd, 228 F.2d 619 (5th Cir.), cert, denied, 351 U.S. 931

(1955).

16When Brown was decided, about 70% of all blacks lived in states

with segregated school systems. The Court in Brown noted that “in the

North segregation in public education has persisted in some com

munities until recent years. It is apparent that such segregation has

long been a nationwide problem, not merely one of sectional concern” .

347 U.S. at 491 n.6.

21

In 1956 this Court observed that even before Brown it

had “ordered the admission of Negro applicants to

graduate school without discrimination because of color.”

It said:

As this case involves the admission of a Negro to a

graduate professional school there is no reason

for delay. He is entitled to prompt admission. . . .

Florida ex rel. Hawkins v. Board o f Control, 350

U.S. 413,413-14 (1956). (Emphasis added).

More than a decade later, this principle was still being

reiterated by the courts.17 In Lee v. Macon Countv Board of

Education. 267 F. Supp. 458 (M.D. Ala.), aff'd. 389 U.S.

215, (1967), the District Court found that the state’s

colleges were maintained on a segregated basis. It held:

[Tjhese schools have been and continue to be

operated as if Brown v. Board of Education were

inapplicable in these areas. . . . It is quite clear

that the defendants have abrogated, and openly

continue to abrogate, their affirmative duty to ef

fectuate the principles of Brown v. Board of

Education, supra. Lee v. Macon County Board of

Education. 267 F. Supp. at 474.

17Tennessee’s reluctant compliance with the law is documented in

Booker v. Tennessee Board o f Education. 240 F.2d 689 (6th Cir.), cert,

denied. 353 U.S. 965 (1957). The state devised a gradual integration

plan under which graduate students would be admitted in the 1955-56

academic year, college seniors the following year, juniors the year after

that. etc. Under the plan it would be 1959-60 before any black fresh

men were admitted. The University contended that the stepped ap

proach was necessary to prevent overcrowding. The court found this

defense inadequate noting particularly that 143 non-residents of Ten

nessee were enrolled in the University.

22

2. A variety of devices were employed by the states to frustrate

the application of Brown to higher education.

As constitutional provisions and statutes requiring a

dual school system were struck down, other forms of main

taining the status quo were devised.

a. Certificates

In 1956, the Louisiana legislature passed a law requiring

applicants to institutions of higher education to present a

certificate of eligibility and good moral character signed

by their former principals and superintendents. The le

gislature also passed a law which provided, in effect, that

principals and superintendents would lose their jobs if they

signed the certificates for Black applicants. The laws had

the intended result of maintaining dual school systems. The

court struck them down stating:

The fact that a transparent device is used,

calculated to effect this same result, does not

make the legislation less unconstitutional. Ludley

v. Board o f Supervisors, 150 F. Supp. 900, 903

(E.D. La. 1957), affd, 252 F.2d 372 (5th Cir.),

cert, denied, 358 U.S. 819(1958).

In Georgia, admission to the university system required a

certification of good moral character, based on personal

acquaintance and attested to by alumni of the institution

that the student desired to attend. This device was struck

down in Hunt v. Arnold, 172 F. Supp. 847 (N.D. Ga. 1959).

The court declared:

The effect of the alumni certificate requirement

upon Negroes has been, is, and will be, to prevent

Negroes from meeting this admission require

ment. 172 F. Supp. at 856.18

18The court also declared invalid Georgia’s out-of-state tuition

program for Blacks which was still in operation despite this Court’s

declaration, over twenty years earlier, that such programs were un

constitutional.

23

As late as 1962, the requirement of certificates was still

being challenged in the courts. Meredith v. Fair, 305 F.2d

343 (5th Cir.), cert, denied, 371 U.S. 828(1962).

The court found that:

One of the most obvious dodges for evading the

admission of Negroes to ‘white’ colleges is the

requirement that an applicant furnish letters or

alumni certificates. . . . The University’s con

tinued use of the requirement seems completely

unjustifiable in view of decisions denying the use

of such certificates at Louisiana State University

and at the University of Georgia. We regard the

continued insistence on the requirement as

demonstrable evidence of a State and Univer

sity policy of segregation that was applied to

Meredith. Meredith, 305 F.2d at 352.

b. Appropriations

In 1961 the court struck down a 1956 Georgia law

making maintenance of a one-race school a condition

precedent to the receipt of state funds. Holmes v. Danner,

191 F. Supp. 394, 400 (M.D. Ga.), stav denied, 364 U.S. 939

(1961).

A similar legislative scheme in South Carolina was struck

down in 1962. Gantt v. Clemson Agricultural College, 320

F.2d 611 (4th Cir.), cert, denied, 375 U.S. 814 (1963).19

c. Accreditation

In 1963 Harold A. Franklin, a Negro, challenged the ad

mission requirement of the Graduate School at Auburn

University that an applicant possess an undergraduate

degree from an accredited institution. The court held that

in the context of Alabama’s overall higher education

l9The court also struck down South Carolina's out-of-state tuition

grant program which was still in operation

24

program, the rule denied equal protection. Franklin v.

Parker, 223 F, Supp. 724, 726 (M.D. Ala. 1963), modified,

331 F.2d 841 (5th Cir. 1964). The court said

It is the State of Alabama . . . that causes and per

mits the lack of accreditation of Alabama State

College and it is the State of Alabama that causes

or allows Auburn University’s requirement con

cerning admission from an accredited institution.

. . . [T]he State of Alabama is as much to blame

for the plaintiff’s inability to satisfy Auburn’s

requirement for admission to its Graduate School

as if “it had deliberately set out to bar the plain

tiff from Auburn solely because he is a Negro.”

Franklin v. Parker, 223 F. Supp. at 727.

Alabama was not the only state to use the accreditation

requirement to perpetuate segregation. In Meredith v.

Fair, the court commented on a requirement of the Univer

sity of Mississippi that transfer students have prior training

at “approved” institutions. The court said

Translating, the Registrar said that this means

that Meredith could not transfer to the University

because Jackson State College was not a member

of the Southern Association of Colleges and

Secondary Schools. It also means that the Board,

which runs Jackson State too, could set up at

Jackson State and other Negro colleges a program

inherently incapable of ever being approved. . . .

The reason was never valid, and again demon

strates a conscious pattern of unlawful discri

mination. Meredith, 305 F.2d at 353.

d. “Private” Character of Schools

In several states, universities attempted to escape the

reach of the Fourteenth Amendment by denominating

themselves “private institutions. Guillory v. Admin

istrators o f Tulane University, 203 F. Supp. 855 (E.D. La.

25

1962). See Hammond v. University o f Tampa, 344 F.2d 951

(5th Cir. 1965).

C.The Segregative Practices in Higher Education

Caused the Underrepresentation of Minorities in

the Professions.

The denial of equal educational opportunity is the denial

of opportunity to enter a profession. The practice of any

profession today is contingent on graduation from an ac

credited course of study. Entry to a profession is barred ab

sent higher education. Even before Brown, this Court

struck down barriers to higher education for a black

student because such barriers denied the opportunity to

become “a leader and a trainer of others.” McLaurin v.

Oklahoma State Regents for Higher Education, 339 U.S. at

641. In Brown, the need for equal education was based in

part on the place of education as the “principal instrument

. . . in preparing . . . for later professional training”. 347

U.S. at 493.

As discussed above, the opportunity for Blacks to obtain

professional training has not historically been equal to that

provided for Whites; segregative practices persisted long

after this Court demanded that they cease. De jure

segregation in higher education may have been more

prominent in the Southern and border states, but it has af

fected virtually all Blacks because they lived in those states.

In 1940, 80% of all Blacks lived in those states; in 1950,

70%; and in 1960, 60%.20 By 1970, only 56% of the black

population lived there.21

20See note 11 supra for source of figures for 1940 and 1950; the 1960

figure was computed from U.S. Bureau of the Census, Statistical Ab

stract of the United States: 1970, 27, Table 28 (91st ed. 1970).

21 U.S. Bureau of the Census. Census o f Population: 1970, General

Population Characteristics, Final Report PCtIJ-BI United States Sum

mary, 1-293, Table 60.

26

The following data, computed from U. S. Census

figures,22 demonstrates the effect of the unconstitutional

practices on the entry of Blacks into selected professions.

Blacks as Percentage

ot Employed (Male) in Selected Professions

Year

(Blacks as

Percentage of

Total Population)

1940

(9.7)

1950

(9.9)

1960

(10.5)

1970

(11)

Profession

Architects 0.4 0.6 0.41 2.06

Lawyers & Judges 0.6 0.8 1.1 1.25

Physicians &

Surgeons 2.2 2.1 2.1 2.04

Dentists 2.1 2.1 2.65 2.46

Pharmacists 1.0 1.4 1.11 2.14

Engineers 0.1 0.3 0.48 1.12

Civil 0.1 0.4 0.78 1.30

Electrical 0.1 0.3 0.48 1.37

From 1940 to 1960 only negligible gains were recorded. By

1970, some significant advances had been registered,

although not in medicine. With the advent of minority ad

missions programs in the late 1960’s and early 1970’s,

greater progress is being made.

III. AFFIRMATIVE ACTION PROGRAMS CAN BE

REQUIRED WHEN A STATE SUPPORTED SCHOOL

HAS DISCRIMINATED AGAINST MINORITIES.

It has been clear since 1968, with respect to dual school

systems, that school authorities are “clearly charged with

the affirmative duty to take whatever steps might be

necessary to convert to a unitary system in which racial

“ See Appendix A for Census data from which the percentages were

computed.

27

discrimination would be eliminated root and branch”.

Green v. County School Board. 391 U.S. at 437-38 (1968).

The mere cessation of past segregative practices does not

satisfy this duty. “Open-door” policies and “neighborhood

school” programs have fallen when they “fail to counteract

the continuing effects of past school segregation”. Swann,

402 U.S. at 28. See also. Keyes v. School District No. 1,

Denver. Colorado. 413 U.S. 189(1973); Geierv. Dunn. 337

F. Supp. 573 (M.D. Tenn. 1972).

The adoption of racially neutral plans has also been held

to be insufficient. Statutes that forbid the assignment of

students “on account of race or for the purpose of creating

a racial balance or ratio in the schools” have been struck

down; such statutes, “against the background of

segregation, would render illusory the promise of Brown v.

Board of Education”. North Carolina State Board of

Education v. Swann. 402 U.S. 43, 45-46 (1971). The same

standards apply to higher education. Norris v. State Coun

cil o f Higher Education. 327 F. Supp. 1368 (E.D. Va), a ff d

mem.. 404 U.S. 907, (1971). Geier v. Dunn.

This Court has rejected arguments that the Constitution

requires assignments to be made on a color blind basis .

Swann. 402 U.S. at 19. In North Carolina State Board of

Education v. Swann, the Court said:

Just as the race of students must be considered in

determining whether a constitutional violation

has occurred, so also must race be considered in

formulating a remedy. 402 U.S. at 46.

And the Court has specifically supported quotas in

school, districting, and employment cases. Swann; United

Jewish Organizations v. Carey. 45 U.S.L.W. 4221, 4226

(March 1, 1977) “fAj reapportionment cannot violate the

Fourteenth . . . Amendment merely because a State uses

specific numerical quotas in establishing a certain number

of black majority districts” ; Bridgeport Guardians Inc. v.

28

Members o f Bridgeport Civil Service Commission, 482

F.2d, 1333 (2d Cir. 1973) cert, denied, 421 U.S. 991 (1975)

(entry level hiring); Rios v. Enterprise Assn. Steamfitters

Local 638, 501 F.2d 622 (2d Cir. 1974); Vulcan Society v.

Civil Sendee Commission, 490 F.2d 387 (2d Cir. 1973).

Thus, under prevailing law, the special admissions

program at issue in this case would have been permissible

under the Equal Protection Clause, and might have been

required, if there were evidence of past discrimination by

the Regents of the University of California.

IV. PROFESSIONAL SCHOOLS ARE PERMITTED TO UN

DERTAKE AFFIRMATIVE ACTION PROGRAMS FOR

A LIMITED TIME WHERE UNDERREPRESEN

TATION OF MINORITIES IN SUCH SCHOOLS,

AND IN THE PROFESSIONS, RESULTS FROM

WIDESPREAD SEGREGATIVE PRACTICES IN THE

PAST.

Brown v. Board of Education was decided in 1954. A

child born in that year would now be old enough to apply to

medical school. If unlawful discrimination had ceased in

1954 there would, perhaps, be no need for continued

remedial efforts today. But the promise of Brown has not

been fulfilled.

[M]any difficulties were encountered in im

plementation of the basic constitutional

requirement that the State not discriminate bet

ween public school children on the basis of their

race. . . . Deliberate resistance of some to the

Court’s mandates has impeded the good faith ef

forts of others to bring school systems into com

pliance. The detail and nature of these dilatory

tactics have been noted frequently by this court

and other courts. . . . [I]n 1968, very little progress

had been made. . . . Swann, 402 U.S. at 13.

In 1968 this Court ordered school authorities to develop

a plan that “promises realistically to work now". Green r.

29

County School Board, 391 U.S. at 439. (Emphasis in

original). In 1969, “fresh evidence of dilatory tactics” ap

peared; the Court ordered that the remedy “be im

plemented forthwith." Swann. 402 U.S. at 14.

Desegregation orders have been issued against school

systems in the non-Southern states. Keyes v. School District

No. 1, Denver. Colorado, 413 U.S. 189(1973). California is

no exception. Crawford v. Board of Education. 130 Cal.

Rptr. 724, 551 P.2d 28 (1976).

The children of Brown — the graduates of an equal

educational system — have not yet been born. We deal in

Bakke with a generation that was promised equality but not

given it.

We argued in the preceding section that affirmative ac

tion programs, including those that rely on quotas, may be

required when the party before the court has discriminated

in the past. We argue here that professional schools should

be permitted voluntarily to undertake such programs as

part of the effort to reduce the underrepresentation of

minorities in the professions and in professional schools —

underrepresentation caused by segregative practices.

A.Voluntary Efforts to Eliminate the Effects of Past

Discrimination Have Been Supported by This

Court and Are Consistent with National Policy.

In Swann this Court distinguished between the measures

that school authorities could undertake as a matter of

discretion, “absent a finding of a constitutional violation” ,

and measures that a federal court could order them to un

dertake to remedy a constitutional violation. It noted that

“judicial powers may be exercised only on the basis of a

constitutional violation” 402 U.S. at 16. The Court noted,

however, that school authorities had broad discretion to act

30

voluntarily “absent a finding of constitutional violation’’.

Mr. Chief Justice Burger said

School authorities are traditionally charged with

broad power to formulate and implement

educational policy and might well conclude, for

example, that in order to prepare students to live

in a pluralistic society each school should have a

prescribed ratio of Negro to white students reflec

ting the proportion for the district as a whole. To

do this as an educational policy is within the

broad discretionary’ powers o f school authorities;

absent a finding of a constitutional violation,

however, that would not be within the authority of

a federal court. 402 U.S. at 16. (Emphasis added).

Congress as well as this Court has emphasized the im

portance of voluntary efforts to eliminate the effects of

discrimination. Discussing the Civil Rights Act of 1964,

which prohibited racial discrimination in voting, public ac

commodations, education, and employment, the House of

Representatives stated

[The Act] is general in application and national

in scope. No bill can or should lay claim to

eliminating all of the causes and consequences of

racial and other types of discrimination against

minorities. There is reason to believe, however,

that national leadership . . . will create an at

mosphere conducive to voluntary or local

resolution of other forms of discrimination. H.R.

Rep. No. 914, 88th Cong., 2d Sess. Reprinted in

1964 U.S. Cong. & Adm. News 2391, 2393.

The Senate Report noted “the measure speaks on the

problem solving level with primary reliance placed on

voluntary and local solutions. Only when these efforts

break down would the residual right of enforcement come

into play” . S. Rep. No. 872, 88th Cong., 2d Sess. Reprinted

in 1964 U.S. Cong. & Adm. News 2355, 2356.

31

This case represents a voluntary response to the problem

of eliminating the vestiges of segregation from education

and employment. It represents both the exercise of the

“broad discretionary powers of school authorities” referred

to in Swann and the local initiative on which Congress

placed “primary reliance” in 1964. In contrast, the cases

that usually reach this Court represent a “break down,” an

exercise of the “residual right of enforcement.”

B.The Professions and Professional Schools Are

National in Character and Are Entitled to

Remedy the Effects of Past De Jure Segregative

Practices.

When Gaines and its progeny were decided, most Blacks

lived in the South. Professionals were commonly educated

in and practiced in the states in which they grew up. Con

ditions have changed. Blacks and other minorities are

widely dispersed. Professional schools no longer serve the

parochial interests of a single state; they draw their student

populations from a wide geographic area, and their

graduates practice in many different places. The standards

of professional education are national and are frequently

set by the professions themselves. State supported

professional schools both contribute to and benefit from a

nationwide pool of students and graduates. Professional

schools have responsibilities to the professions they serve.23

In light of the national character of higher education and of

the professions, the Court should not prevent professional

schools from voluntarily undertaking, as an exercise of

citizenship, to remedy the nationwide underrepresentation

of minorities caused by widespread discrimination in the

past. State universities should be permitted voluntarily to

"In Bakke, the Petitioner states that its special admission program

was necessary to integrate the profession. Bakke, 132 Cal. Rptr. at 692,

553 F.2d at 1164. The court did not respond to this point.

32

remedy the de jure segregative practices of schools in other

states.

C.The Focus of the Court Below Was Too Narrow.

In holding that “the University has not engaged in past

discriminatory conduct” Bakke, 132 Cal. Rptr. at 697, 553

P.2d at 1169, the court below apparently focused solely on

whether the medical school at the University of California

at Davis had discriminated in the past. It considered

neither discrimination in the system of higher education

administered by Petitioner — the Regents of the University

of California — nor evidence of discrimination in Califor

nia's elementary and secondary schools.

Segregation in the California school system is well

documented. In one decision Mr. Justice Douglas said:

“[T]here is a showing here that the State is maintaining a

segregated school system for the Blacks and Chicanos that

is inferior to the schools it maintained for the Whites.”