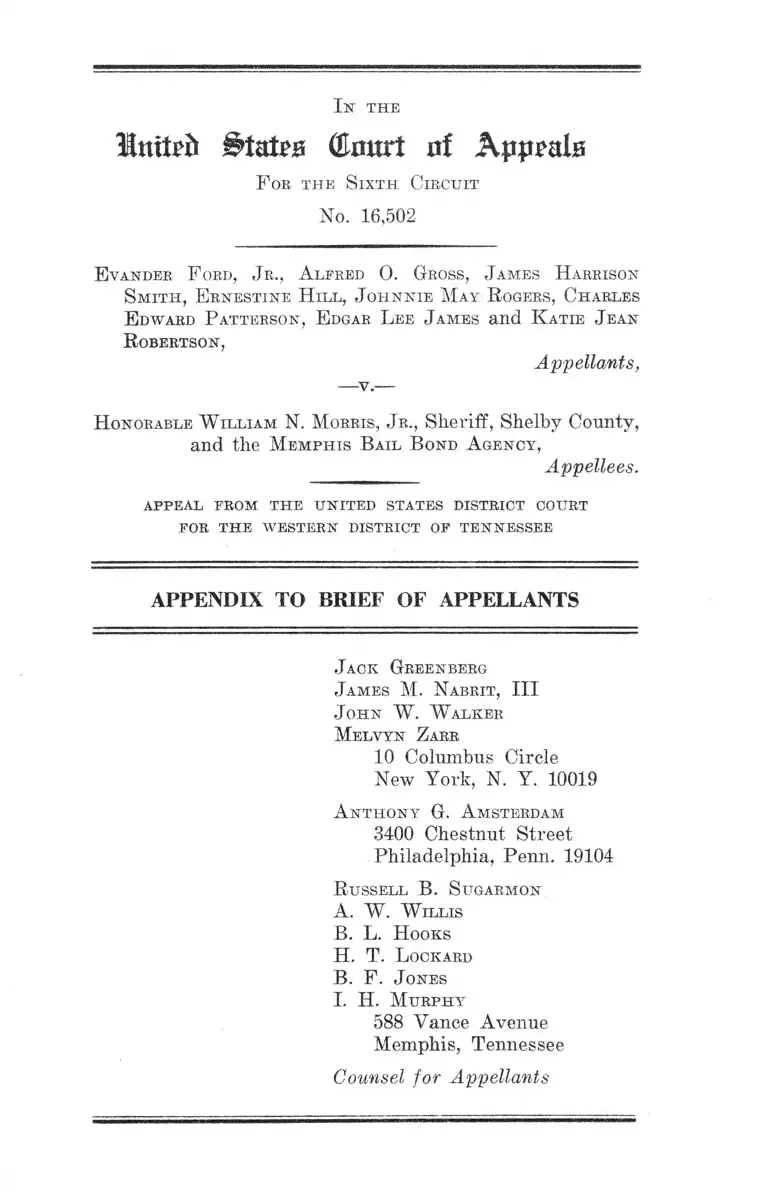

Ford v. Morris Appendix to Brief of Appellants

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1965

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Ford v. Morris Appendix to Brief of Appellants, 1965. d381a521-b29a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/6e046886-ea17-4fdd-920a-82e17c7d475a/ford-v-morris-appendix-to-brief-of-appellants. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

In* t h e

Hutted States (Enurt uf Appeals

F ob t h e S ix t h C ir c u it

No. 16,502

E vander F ord, J r., A lfred 0 . G ross, J am es H arrison

S m it h , E r n e s t in e H il l , J o h n n ie M ay R ogers, C h a rles

E dward P a tterso n , E dgar L ee J am es a n d K atie J ean

R obertson ,

Appellants,

H onorable W illia m N. M orris, J r., S h e r if f , S h e lb y County,

a n d th e M e m p h is B a il B ond A g en cy ,

Appellees.

a p p e a l f r o m t h e u n i t e d s t a t e s d i s t r i c t c o u r t

FOR T H E W ESTERN DISTRICT OF TEN N ESSEE

APPENDIX TO BRIEF OF APPELLANTS

J ack Greenberg

J am es M. N abrit , III

J o h n W . W alker

M elv y n Z arr

10 Columbus Circle

New York, N. Y. 10019

A n t h o n y G. A m sterdam

3400 Chestnut Street

Philadelphia, Penn. 19104

B u sse l l B. S ugarm on

A. W . W il l is

B. L. H ooks

H. T. L ockard

B. F. J ones

I . H. M u r p h y

588 Vance Avenue

Memphis, Tennessee

Counsel for Appellants

INDEX TO APPENDIX

PAGE

Indictment .................... .................-......................... ...... la

Excerpts from Testimony:

Rev. T. E. Scruggs—

Direct ............. ................................ -.......—...... 2a

Cross ....... .............—- .................... ........ 6a

Redirect __.................. - .... ........... -................. 9a

Doyle E. Burgess, Jr.—

Direct ............ 10a

Ed Bryeans—

Direct .................. 13a

Cross ...... ........... .... .............. ..................... -.... 14a

William P. Sharp—

Direct ........ .... .......... ........................-........ — 15a

Cross ----- 17a

J. E. Crawley—

Cross ..... 18a

Ed Bryeans—

Direct ...... 22a

Cross ..... ..... .... .....— ......................... — ....— 23a

William P. Sharp—

Cross ____ _________ - .... .....-......... —- ........ 24a

J. C. McCarver—

Direct ......................... — ............... .............. 25a

Cross .............. ...............—............ ........... ..... 25a

Motion to Dismiss ..... ................... .....-......................... 26a

M o tio n to D ism is s O v e r ru le d 28a

PAGE

Opinion of Tennessee Supreme Court ............... ......... 32a

Order .............................. ................... .............. ............ 39a

Order ...... — ........ .................................................... . 41a

Denial of Petition to Rehear .............. ..... ................... 42a

Petition for Writ of Habeas Corpus............................ 43a

Motion to Dismiss Petition ................. ........... .......... . 51a,

Opinion of District Court ............ .............. .............. . 55a

Order ................................ .................. ......................... 65a

Relevant Docket Entries ................... .......................... 67a

ii

—6

Ind ic tm en t

STATE OF TENNESSEE

S h e l b y C ounty '

Cb im in a l C oubt of S h e l b y C o u n ty

May Term, A.D. 1960

T h e Geand J ueo es of the State of Tennessee, duly

elected, empaneled, sworn and charged to inquire in and

for the body of the County of Shelby, in the State afore

said, upon their oath, present that Evander Ford, Jr.,

Alfred 0. Gross, Katie Jean Kobertson, James Harrison

Smith, Anita Laverne Stiggers, Harry James, Jr., Ernes

tine Hill, Johnnie May Rogers, Charles Edward Patterson

and Edgar Lee James, late of the County aforesaid, here

tofore, to-wit on the 30th day of August, A.D. 1960 before

the finding of this indictment, in the County aforesaid, did

unlawfully and willfully disturb and disquiet an assemblage

of persons met for religious worship at the Overton Park

Shell, in Memphis, Shelby County, Tennessee, after being

refused admittance to the services therein, did force their

way into the said assemblage, seated themselves among

the worshippers, and by this act did cause the disruption

of said religious assemblage against the peace and dignity

of the State of Tennessee.

/s / P h il M. C a n a le , J b.

Attorney-General Criminal Court of

Shelby County, Tennessee

2a

Excerpts From Testimony

* * * * #

—63—

T estim o n y of R ev . T. E. S cbuggs

Direct Examination by Mr. Beasley:

Q. Will you state your name to the Court and Jury,

please. A. T. E. Scruggs.

* * * * #

— 69—

Q. Do you have a profession, or calling, Mr. Scruggs?

A. Yes, sir. I am a minister.

Q, Will you tell us what faith you are a minister of!

A. The Assembly of God.

* * * * *

Q. Do you have a church here in the City of Memphis?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. Are you a pastor; would that be correct? A. Yes,

sir.

Q. Would you tell the Court and Jury the name of this

church? A. The Hollywood Assembly of God; 1383 Box

wood.

* * * * *

— 70—

Q. Reverend Scruggs, looking hack and directing your

attention back to 1960, were you the Pastor of the Church

on Boxwood then? A. Yes, sir.

Q. At that time, as pastor, were you promoting these

youth rallies you just talked about? A. Yes, sir.

Q, 1 will ask you if there was any place in particular

you were holding these rallies? A. On this particular

date, we were scheduled at the Overton Park Shell for a

3a

city-wide youth rally; consequently, all of our churches

participated.

Q. Is that the Assembly of God Church in this city?

A. Yes, sir.

—71—

Q. Without going into details, who did you lease the

Shell from? A. The City of Memphis.

= & # # # *

Q. On August 30, 1960, do you recall that day—directing

your attention back to that day? A. Yes, sir. I think it

was on Tuesday.

Q. At that time, Reverend Scruggs, as Pastor of the

—72—

Assembly of God Church, were you having any rallies?

A. Yes, sir. We had scheduled a rally at the Overton Park

Shell.

Q. Can you digress and tell us what type services you

were going to have at the Shell on October 30th? A. It

was strictly an inspirational youth service which consisted

of singing of choruses and hymns, a time of devotion,

and a special film that was scheduled to be the main feature

of the rally. And at the rallies, we try to climax it with

Decisions for Christ.

The congregation is primarily for the youth in our

churches.

# # * # #

—73—

Q. Reverend Scruggs, did you have ushers assigned out

there to seat the people? A. Yes, sir. We did.

Q. Reverend Scruggs, at the time your services opened

up there at 7 :30, was everything orderly and peaceful at

that time? A. Yes, sir.

Testimony of Rev. T. E. Scruggs—Direct

Q. Were the services opened to the public, or confined

to the Assembly of God Church? A. Open to the public.

Q. I will ask you if at any time after the services began,

were they interrupted? A. Yes, sir. They were inter

rupted.

Q. Could you tell us, Reverend Scruggs, as near as you

can recall, .just what took place to interrupt your services

out there? A. The services had been going on for about

15 or 20 minutes—somewhere in that neighborhood—and

it was called to my attention by one of the ushers that

there were a couple of negro youths entering the Shell.

And, of course,' they reported the brief conference they

had had with them at the entrance, or near the entrance,

of the Shell.

They stated to me they had informed them that it was

segregated, and asked them to leave, and if they would

—74—

not go, then rather than to disturb the services, they

were told they could sit at the rear, as the services were

already going on. And, after being told that, they would

not obey the ushers in charge; then, I felt it my duty,

as I was the one overseeing the rally, to do something

about it, and it was at that time that I went and called

the police.

Q. Reverend Scruggs, could I interrupt you there.

After this discussion took place between the ushers and

the colored people, what did they do, if anything? A.

When I turned and I noticed there was quite a stir—I was

sitting down toward the side on the front somewhere; I

was not on the platform, but I was seated down at the

front. The Program Committee in charge was on the plat

form—and there was quite a stir among the youth, and I

turned to see what was happening. And when I looked, I

Testimony of Rev. T. E. Scruggs—Direct

5a

saw this group of colored young people were dispersing

themselves among the white young people that were there.

This caused some of the white young people to slide away,

not being accustomed to such practices; and some got up

and left their seats in the Shell; and others were moving;

and for some few minutes, because of the unrest, it dis

quieted the services.

Q. I believe you stated that after experiencing this, you

called the police? A. That’s right.

—75—

Q. And made a complaint to the Memphis Police De

partment? A. Yes, sir.

Q. At the time these colored people entered your ser

vices out there, what part of your service was taking place

at that time, if you recall? A. If I recall correctly, we

were singing hymns. We were at what I wTould term the

preliminary part; and, of course, the film was scheduled

to be shown immediately following.

And when I left to go and call the police, and came back

from the phone, I saw that the place had been blacked

out, and the film had started. It was then that I instructed

—seeing that many of our people were leaving—I in

structed the Program Director to hold the film until the

audience was quieted and some arrangement could be

made.

Q. Your congregation started going out? A. Yes, sir.

Q. And you stopped showing the film? A. Yes, sir.

Q. I will ask you if you see any colored youths in the

courtroom that came out and disquieted your services?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. Will you point out the ones you can recall? A. I re

member that young man behind you.

Testimony of Rev. T. E. Scruggs—Direct

6a

Q. Evander Ford? A. Yes; and Earnestine Hill, and

Johnnie May Rogers; and also Patterson.

# # * # #

— 76—

Q. Reverend Scruggs, do you recall how many there

were that came in out there and disquieted your services?

A. I believe there were fourteen; thirteen or fourteen, I

believe.

Q. Reverend Scruggs, did the police come out ; did they

answer your complaint? A. Yes, sir. It was about three

to five minutes. There was one squad car on the scene, and

then there were others that came. We let the colored youth

stay in until the Lieutenant came.

# # * # #

— 77—

Q. Reverend Scruggs, I will ask you if you had these

people removed because of their color? A. Not at all.

Q. Reverend Scruggs, I will ask you if they had fol

lowed your ushers’ advice, if you would have made a com

plaint to the Police Department? A. No, sir.

# # * # #

— 78—

Cross Examination by Mr. Hooks:

Q. And I believe you stated on your direct examination

that this meeting was open to the public? A. Yes.

Q. If Methodists, or Baptists, or Catholics, or Presby

terians had come, they would have been welcome? A.

Yes.

Q. It would not have been necessary for the people com

ing to have been members of the Assembly of God Church?

A. No.

Testimony of Rev. T. E. Scruggs—Cross

# # # # #

7a

Q. It was an evangelistic meeting! A. Yes.

Q. Was this meeting given some advertisement! A. As

to my own promotion, I did not do any. The only knowl-

—7 9 -

edge I have is the article you showed me at a former hear

ing.

Q. And the service was open to the youth in this com

munity? A. I believe that is what the article said.

Q. I believe you said that if they had followed the in

structions of the ushers, they would not have been asked

to leave! A. Yes.

Q. What were the instructions of the ushers? A. I be

lieve—First of all, they were asked if they would leave,

and they would not; and then they were asked to sit be

hind in these rear seats so as not to disturb the services.

Q. As a matter of fact, they were invited to have seats

in the rear? A. They were invited to have seats in the

rear, so as not to disturb the services that were going on.

Q. Is it generally true that people who come in late to a

meeting, disturb the meeting? A. Yes; but anyone that

would disturb my services, I would have them removed.

Q. Anybody that came in late, you would have them

removed? A. Anybody that would cause a disturbance.

Q. People are not accustomed to negroes coming in, in

this area? A. That’s right. They were not accustomed to

—SO-

attending services with negroes.

Q. And this disturbed the gathering, in this sense of the

word, because they were negroes? A. I suppose that is

true; yes.

Q. Were they loud? A. According to the reports I re

ceived that—

Q. (Interrupting.) I mean, to your knowledge.

Testimony of Rev. T. E. Scruggs—Cross

8a

The Court: Reverend Scruggs, in answer to his

questions, just tell him what you know of your own

knowledge.

A. Not to my knowledge.

By Mr. Books:

Q. Did you see any rudeness or indecent behavior, or

hear any cursing or profanity! A. No.

Q. Were they dressed more or less like the other young

people that were there! A. Yes.

Q. They were! A. Yes.

Q. But they would not take seats at the rear of the

Shell! A. Not necessarily—they would not take seats as

signed them by the ushers.

Q. Were there not a number of vacant seats between

where they came in and where the audience was sitting!

A. Yes.

=& # * =*=

— 81—

Q. You testified that these people were told that the meet

ing was segregated. A. I testified that that was what was

told to me.

Q. That the meeting was segregated! A. Yes.

— 82—

By Mr. Books:

Q. The question is: You have stated here that the pub

lic, generally speaking, was invited! A. That is correct.

Q. But not Negroes? A. We had never faced a situa

tion of this nature, and in invitations we never have found

it necessary to have to use any terms of that nature in

Testimony of Rev. T. E. Scruggs—Cross

9a

advertising; having no Negro members of our church, of

course we do not expect any such thing as this to happen.

* * * * *

-84-—

Redirect Examination by Mr. Dwyer:

Q. I would like to ask you one other question.

Reverend Scruggs, if a Methodist or Baptist or Catholic

had come out there, white or black, and disturbed your

service, would you have had them arrested! A. Yes, sir.

* * * * *

By Mr. Hooks:

Q. What caused the disturbance! A. Any time that

people have to move by others and slide into a seat late,

they disturb the other people. They did not obey the ushers;

they did not take the places that were assigned to them.

The thing that caused the disturbance was that they in

termingled—and if you know anything about the Overton

- 8 6 -

Park Shell, the seats are very close together—and instead

of them taking seats in the vacant rows, they decided to

slide in and take seats and intermingle with the crowd.

* * * * *

—87—

Q. Do you have any knowledge as to whether the ushers

asked anybody other than the Negroes to take seats in the

rear? A. You have said that I only can say what I know,

not what I heard, and that is all I could repeat—what I

heard. I don’t know what the ushers did?

Q. You don’t know what they did? A. No, sir.

* * * * *

Testimony of Rev. T. E. Scruggs—Redirect

10a

Testimony of Doyle E. Burgess, Jr.—Direct

—8 9 -

T estim o n y of D oyle E. B urgess , J r.

Direct Examination by Mr. Beasley:

Q. Did you have occasion to attend that rally on August

30, 1960? A. Yes, sir.

Q. Did you perform any particular function? A. Yes,

sir, as an usher and co-ordinator in the meeting?

Q. What time did you arrive at the Shell? A. About

7 :20.

Q. What time was the rally scheduled to start? A.

Seven-thirty.

Q. I will ask you whether or not there were many or few

people in attendance by 7:30 that evening? A. Yes, sir;

there was a fairly good crowd by 7 :30.

Q. Did you make a count of the people there ? A. There

was no exact per capita count, but I would estimate four

to six hundred people; something like that.

—90—

Q. Did the services start at 7 :30, as scheduled? A. Yes,

sir.

Q. Mr. Burgess, I will ask you if during the course of the

services—did anything out of the ordinary happen? A. I

think the proceeding got under way about 7 :30, and then

around about 7:40 or 7.45 I was standing at the rear of the

auditorium, when I was met by a group of colored young

people. And as they entered, I walked toward the back and

greeted the young man that was leading the group, and

shook hands and talked just a minute.

Q, Mr. Burgess, at this time do you see the young boy

whom you met and shook hands with that night; do you see

him in the courtroom? A. Yes, sir, the young man sitting,

in the second row to my left.

11a

Q. Could you tell the Court and Jury which one in the

row? A. This one at the extreme left—in the second row

there.

Testimony of Doyle E. Burgess, Jr.—Direct

Mr. Beasley: Let the record show that he has in

dicated Evander Ford.

By Mr. Beasley:

Q. You stated that you walked to the group. Could you

tell how many were in the group? A. It is hard to tell;

they came two-by-two, and there were several groups, but

I would say 14 or 15.

Q. And you walked up to that person whom you have

—91—

identified as Evander Ford, and shook hands with him?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. Did you converse with him at that time? A. Yes, sir.

When I met them, I tried to anticipate that there might be

difficulty at the meeting, since at that particular time it

was not uncommon that this type situation occur. And I

asked them out of courtesy if he would not remain, since

this was a segregated meeting, featuring the young people

of the Assembly of God.

Q. Did you greet him and talk with him in a courteous

manner? A. Yes, sir.

Q. Did he talk with you in a courteous manner? A. I

don’t remember what was said, but in a moment he turned

and instructed the group to scatter out. Those were his

exact words, “Scatter out”.

Q. He instructed the other young people to scatter out?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. Mr. Burgess, had you at any time invited the people

to be seated; had you made a statement along those lines?-

12a

A. Yes, sir. At the moment we first met there, 1 told them

that I thought it would be better if they not come in ; and

then I got a plan. There were about 20 rows that were

vacant, and since the group was quite large, I suggested

that they sit in the 20 rows, since the meeting was going on.

—-92—

And that is when he said, “Scatter out”.

Q. Did you make that offer at that time, for them to

please be seated? A. Yes, sir.

Q. Mr. Burgess, at that time I believe you stated there

were about 20 empty rows in the back, 15 or 20! A. Yes,

sir.

Q. Were there also empty seats close to the aisles? A.

Yes, sir.

Q. After that statement was made, was anything further

said, or what happened? A. Well, I was standing approx

imately in the center of the aisle, and it was fairly wide,

and some of the group just pushed past me and made their

way mostly, I would say to the center of the rows, where

the people were sitting.

Q. Did they sit as a group? A. No, sir. There might

have been as many as two or three sitting together, but

mainly they went in couples. There might have been four

together, but it was mainly different couples that split up.

Q. Mr. Burgess, if you will, please explain to the Court

and Jury what, if anything, occurred upon these people

moving in and seating themselves among the people al

ready present? A. The young people began to make their

way into the congregation and disperse themselves through

—93—

the congregation. Many of our young people began to

move to the other parts of the auditorium, and quite a

number began to leave. I couldn’t estimate how many

Testimony of Doyle E. Burgess, Jr.—Direct

13a

exactly, but quite a number left the auditorium as a result

of that.

# * # * *

—96—

T e stim o n y of E d B byeans

Direct Examination by Mr. Dwyer:

Q. Do you recall if on that date you were in the City of

Memphis? A. Yes, sir.

Q. Around 7:30 p.m., do you remember where you were

in the City, Mr. Bryeans? A. Yes, sir. I was at the

Overton Park Shell.

Q. Could you tell the Court and Jury the reason for your

being out there that evening? A. I was supposed to be

the head usher with six ushers under me.

# # # # #

—98—

Q. Around 7 :45 p.m., your services were under way and

had started? A. Yes, sir.

Q. Around 7 :45 were you still acting as usher? A. Yes,

sir.

Q. Did any disturbance take place out there at that time?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. Will you tell us as near as you can recall what took

place and what you observed on that evening, at that time?

A. Several colored people came in the entrance, and Gene

went over—

Q. (Interrupting.) Who is Gene? A. Gene Burgess.

Q. That is the gentleman who just testified? A. Yes,

sir. —(Continuing.) And they came in the entrance and,

Gene asked them to leave, and they said they wouldn’t.

—99—

And we asked them to take seats over at the side, and they

wouldn’t do that.

Testimony of Ed Bryeans—Direct

14a

And at that time, the leader told the rest of them to

scatter out, and that is when they pushed by us and took

seats all over the auditorium.

Q. Were there any vacant seats? A. Yes, sir; in the

back.

# * # * *

— 100—

Q. —(Continuing.) After they pushed past you and Mr.

Burgess, would you tell us what they did, and what took

place, as near as you recall? A. After they pushed past

us, they took different seats in different rows, and as they

went in they made people move over and disrupted the

services completely, as the people were disturbed as they

made their way into the rows.

Q. Did you notice whether or not anybody left? A. Yes,

sir. There wrere several people leaving.

Q. Would you say they caused the services to be dis

rupted by their pushing past you out there? A. Yes, sir.

Q. Do you know whether or not part of your services

was a showing of a film? A. Yes, sir; that was supposed

to be the inspirational part of the service, and that was in

terrupted because of the colored people entering.

# * * # #

—101-

Cross Examination by Mr. Hooks:

Q. Mr. Bryeans, about how many were in the group, if

you recall? A. In my estimation, from the group I saw,

I would say close to thirteen.

— 102—

Q. As far as you know, all were arrested? A. They

were all arrested.

Q. Did any of them use any profanity? A. They didn’t

use any profanity.

Testimony of Ed Bryeans—Cross

15a

Testimony of William. P. Sharp—Direct

Q. Did they talk loud! A. No, sir.

Q. Did you hear anyone say anything other than Evander

Ford? A. No, sir.

* * * * *

—104—

Q. Did anybody come in at all after 7 :30, other than

these defendants? A. Certainly.

Q. About how many people? A. I don’t know.

Q. And I believe you testified that this was a segregated

meeting? A. It was.

Q. The people who came in after the services started—

I believe there were people who came in after it started?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. Did you ask them to sit in the back? A. Not in the

hack, but I asked them to sit where I wanted them to sit.

Q. Were the vacant rows in the back? A. Yes, sir.

Q. Approximately how many vacant rows were there?

A. Fifteen, at least.

Q. And you hadn’t asked anybody to sit in these fifteen

rows? A. It was not needed. They were lined up behind

each other.

—105—

# # # # #

—107-

T estim o n y of W il l ia m P. S harp

Direct Examination by Mr. Beasley:

Q. I will ask you, Mr. Sharp, if sometimes after 7:30

p.m. that evening, you received a call to go to Overton

Park? A. I did.

Q. Where did you go to at Overton Park? A. The call

was to the Shell in Overton Park, and we drove to the

16a

front entrance of the Shell where we were met by Reverend

Scruggs and several other people.

Q. Was the Shell being used for anything at that time?

A. Yes, sir. Reverend Scruggs stated that his church was

having a youth rally at that time.

Q. Were there a lot of people in the Shell at that time?

A. Yes, sir, there was a very large number.

Q. Mr. Sharp, did you go into the Shell area and into

—108—

where the congregation was at that time? A. No. We

did not.

Q. And did other members of the Police Department

come out to the Shell? A. Yes, sir.

Q. Mr. Sharp, did you at any time enter the area of the

Shell, the seating area of the congregation? A. Yes, sir.

We did after the Lieutenant arrived on the scene. We did

enter, on his instructions.

Q. I will ask you if you will please tell the Court and

Jury just what you observed as you passed in the con

gregation! A. Everyone seemed to be in a disquieted

frame of mind. Several people were milling around, and

several people were leaving, as we went in.

Q. Was the majority of people white or colored? A.

The majority was white—and several colored scattered

among the people.

Q. There were colored scattered among the white people?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. Mr. Sharp, how were these colored people sitting;

were they in a particular group, or how were they sitting?

A. They were sitting—just mingled out in different spots

among the group of people there—in groups of two’s,

mostly with one or two single ones.

Testimony of William P. Sharp—Direct

Testimony of William P. Sharp—Cross

— 109—

Q. Did you place anyone under arrest that night? A.

Yes, sir.

Q. Will you tell us how you went about that? A. Our

instructions were—as we went in the Shell—to locate these

colored people that were in the Shell and inform them that

they were under arrest, and bring them to the outside

entrance of the Shell.

Q. Did you do that? A. Yes, sir.

Q. Did any of them resist you? A. No, sir.

Q. Did you get them together in one place ? A. Yes, sir.

Q. Do you know how many colored people were there,

or how many you rounded up? A. Fourteen.

• * # # #

Cross Examination by Mr. Hooks:

Q. Officer Sharp, did I understand you to say that the

Negroes were not milling around? A. Not that I saw.

Q. What were they doing? A. When we arrived on

the scene, we didn’t see them.

Q. You didn’t see them? A. When we first arrived, we

didn’t.

Q. What were they doing when you saw them? A. They

were seated in the Shell?

Q. They were sitting; they were not milling around; is

that correct? A. Yes.

—Ill—

Q. Did they commit any offense that you know of, in

your presence? A. The offense was, that I could see there

was a large disturbance among everyone there, and it was

stated by the people directing the thing that it was caused

by these people.

18a

Q. Did you see them do anything other than being seated

in the Shell? A. No, sir.

Q. This is a public park? A. Overton Park Shell; yes.

Q. Owned by the City of Memphis? A. Yes.

Q. And what you observed was that they were sitting

in this place? A. Yes, sir.

Q. Were they appropriately dressed? A. Yes, sir.

Q. Did you notice any of them using loud or profane

language? A. No, sir.

Q. Engaged in any boisterous or indecent conduct? A.

No, sir.

Q. Did they put up any resistance when you arrested

them? A. No, sir.

—112—

# # * # #

T e st im o n y of J. E. C raw ley

Cross Examination by Mr. Hooks:

Q. When you saw the Negroes, were they sitting or

standing ? A. Sitting.

Q. Were the white people in the Shell scattered around?

A. They were sitting in the front, sides and center.

Q. When you used the term “scattered around”, what

did you mean? A. They were mixed among the white.

—119—

Q. They just had seats in the Shell? A. Seats among

the white.

Q. And they were not sitting together ? A. That’s right.

Q. And that is what you mean by the term “scattered

around”? A. Yes, sir.

Q. Did you hear any cursing or profanity among the

Negro Defendants, when they were arrested? A. No, sir.

Testimony of J. E. Crawley—Cross

19a

T estimony of J. E. Crawley—Cross

—120—

Q. When you got ready to arrest the Defendants, did

they stop the service so you could arrest them? A. The

best I remember, the show had been stopped and we walked

in and told them to come with us, and they followed us in

an orderly manner.

Q. The movie was going on? A. Yes, sir.

Q. And when you got ready to arrest them, the movie

was stopped? A. I believe it had been stopped.

Q. But it was going on when you got there? A. Yes,

sir.

Q. Did these Defendants commit any acts of boisterous

or rude conduct, in your presence? A. No, sir.

Q. Did they make any resistance when you arrested

them? A. No, sir.

Q. Do you know why you arrested them, Mr. Crawley?

A. We had orders—we just carried out orders.

Q. You had orders to arrest the negroes? A. Yes, sir.

Q. The Overton Park Shell is public property; is it not?

A. It is public; yes.

Mr. Hooks: That is all.

(Witness excused.)

(Short recess.)

—294—

Q. You asked them to take seats in the same place?

A. Yes, I did.

Q. These parties who came late after services began

before these Defendants did? A. Right.

Q. You asked them to sit in the rear ? A. Some of them.

Of course, these that came past while I was talking with

others, I was unable to. Others went ahead while I was

20a

Testimony of J. E. Crawley—Gross

talking to others, like I told you, that went down and

dispersed themselves in the middle.

Q. Some walked down and did exactly as these Defen

dants! A. Some of them did go in the middle.

Q. But some of them did go down and sit in the middle;

is that correct? A. Yes, sir.

Q. I want to get a clear picture as to this disturbance

you testified to. Now, just what was the disturbance?

A. The only disturbance to my knowledge was that as the

young people, of course, are met at the door, when I would

ask them to be seated in a certain section, they would obey,

and the colored young man seemed to be somewhat rude.

I was trying to be friendly with him. He instructed his

group to scatter out. The only disturbance I could see was

that when they began to move in different parts of the

audience, numbers of the young people did leave the

—295-

meeting.

Q. Was that the noise you heard when they were leaving?

A. There was actually no noise.

Q. There was no noise? A. No, sir.

Q. What was the disturbance? A. Well, the disturbance

was caused by these people, such a large group coming in

at one time in the various parts of the audience that were

already assembled.

Q. And what did this large group do to create a dis

turbance ; you say there was no noise; they didn’t say

anything? A. Well, simply by—it was just the magnitude

of the restless people moving. And also I think our young

people could sense more or less what was going on. If we

were sitting here today and a large group dispersed itself

among us, we would sense something wras going on. Thus,

many of them moved.

•21a

Q. But the disturbance was the moving; is that right!

A. Yes, both—(interrupted).

Q. The only audible disturbance was the moving of the

young people! A. The moving in of the colored young

people and the moving out of the white young people.

—296—

Q. I thought you testified they were quiet and orderly!

A. Both groups were orderly, but moving in and out

disturbs. The moving in disturbed and the moving out,

disturbed. Just people moving in and out causes a dis

traction where they are quiet even.

Q. The people, the Defendants, moved in and the other

people moved out! A. Yes, sir.

Q. And that was the disturbance? A. Yes, sir.

Q. But only the ones who moved in were arrested; is

that correct? A. That’s right.

Q. But they were not the only ones who created a dis

turbance, were they? A. Well, if they had progressed like

we had asked, there would have been no disturbance either

way.

Q. But we are getting to the disturbance and who

created the disturbance. The actual noise was the people

leaving; is that correct? A. There was no noise, let’s

understand that. There was no noise by either group.

Q. You testified that the program was stopped? A.

Yes, sir.

Testimony of J. E. Crawley—Cross

# # # # *

22a

Testimony of Ed Bryearn—Direct

—306—

* * # # #

T e st im o n y op E d B ryeans

Direct Examination- by Mr. Beasley:

Q. Tell us what happened, if anything, out of the ordi

nary? A. After services started, a group of colored people

—I don’t know exactly how many it was—possibly twelve

or thirteen—came in the back entrance into the Overton

Park Shell. Gene Burgess and myself—Gene was in front

of me and he greeted them first and we told them it was a

segregated meeting and asked them to leave.

Q. Were these people white or colored? A. They were

colored.

# # * * #

—307—

Q. Mow, I believe you have testified that Mr. Burgess

stated something to the effect that this was a segregated

meeting; is that correct? A. Yes, sir.

Q. Exactly what, if anything, was said ? A. When Gene

told them it was a segregated meeting and asked them to

leave, they said they were not going to do that, and then

Gene asked them would they take a place over there behind

the group instead of going down through them. They said,

“No, we are certainly not going to do that,” like it insulted

them. Their leader, Ford, as I brought out a while ago,

he said, “Scatter out”. Before they all scattered out and

brushed by us, he asked them would they sit right behind

the others, but they would not do that either.

Q. What did they do out there, Mr. Bryeans; where did

they sit, if anywhere? A. After he said, “Scatter out,”

they just took the areas and went down the middle aisles

23a

and side aisles and infiltrated the audience. They went in

the rows, pushing, not exactly pushing, but made their way

through the aisles and sat down, and when they sat down

people naturally moved down to keep from sitting by them.

Of course, a lot of our people got up and left.

—308—

# # * # *

—312—

Cross Examination by Mr. Sugarmon:

Q. Now, about what time did you say the Defendants

came in? A. I don’t recall exactly what time it was.

Q. Approximately what time did they come in? A. I

couldn’t say for sure. I think it was about twenty ’til

eight.

Q. And who addressed any of the Defendants; who

talked with them? A. Gene addressed them first.

Q. How close were you to where he carried on this con

versation? A. Directly behind him.

—313—

Q. Now, who did he talk with? A. Ford.

Q. Did he talk to all of them? A. He talked to all of

them, but his conversation was directed to Ford.

Q. Did Ford say anything to the other Defendants?

A. He directed them to scatter out.

Q. Before that did he say anything? A. No, sir.

Q. He turned to them? A. He turned to them and said,

“Scatter out”.

Q. When they took seats were they orderly? A. It is

according to what you mean by “orderly”.

Q. Were they noisy when they took seats? A. They

were not noisy, no.

Q. Did you hear any of them cursing, having conversa

tions? A. No, sir.

Testimony of Ed Bryeans—Cross

24a

Q. They did not say anything as far as you know? A.

Not that I know.

Q. Did you see the Defendant take a seat? A. I could

not say that I saw her take a seat. I saw her in the hack.

Q. You saw her in the back. You did not see her take

—314—

a seat. Do you know where she sat? A. I don’t know

where she sat.

Q. You don’t know whether she sat in the front or back,

or where? A. No, sir.

Q. You stated they were orderly as far as making noise?

A. They did not make any noise.

Q. You can not testify this particular Defendant took a

seat to the front or to the center or to the back or any

place? A. I couldn’t tell you where she sat.

Q. And not seeing her sit down, you could not tell

whether any of the people around her were disturbed,

could you? A. Not her by herself, no, I couldn’t tell

you that.

—326—

# # * # #

Testimony of William P. Sharp—Cross

T estim o n y of W il l ia m P. S h a r p

Cross Examination by Mr. Jones:

Q. I asked you was there anything going on in there and

you said there was a disturbance going on inside. But my

question was, were these Defendants doing anything when

you went in there that would create a disturbance? A. No.

Q. Did they, at any time while you were there, do any

thing that would be a violation of any ordinance, law, stat

ute, regulation? A. No.

* * # # *

25a

Testimony of J. C. McCarver—Direct—Cross

T estim o n y of J . C. M cCarveb

Direct Examination by Mr. Beasley:

Q. Now, Officer McCarver, did you go inside the Shell

area, in the seating areal A. Yes, sir. When we got

— 329—

there, there were other cars on the scene by the time I got

there, and when we arrived on the scene we found out that

—we met the Reverend Scruggs and he told us they had

some colored people that had come in and created quite a

disturbance inside and quite a few of his people had got

up and left and he wanted us to go in and get them out.

And we went in and got the colored people out.

# * * * *

— 331-

Cross Examination by Mr. Jones:

Q. Officer McCarver, you testified that you received a

call to go the Shell and that you were told by Reverend

Scruggs that the Negro people were in there and that they

created a disturbance? A. I don’t remember if those are

his exact words. He was standing there and he told us

that there was colored people inside and quite a few of his

congregation had got up and left and he wanted us to

remove them from the premises.

Q. But he did not state to you that they were creating

a disturbance? A. I don’t really remember whether it

was in those exact words or not.

— 332—

Q. Was there any disturbance created by these Defen

dants in your presence? A. No, there was no disturbance

created.

26a

Q. Were all these people properly dressed? A. Yes,

properly.

Q. Were they all seated when you went in? A. Yes,

they were all seated.

Q. Were they quiet? A. Well, yes, sir, they were quiet.

—132-—

D e fe n d a n t s’ M otion to D ism iss

“Come now your Defendants, Evander Ford, Jr., Alfred

O. Gross, James Harrison Smith, Ernestine Hill, Johnnie

May Rogers, Charles Edward Patterson, and Edgar Lee

James, and respectfully Move the Court to dismiss the

charge of Disturbing Public Worship now pending against

them for the following reasons:

I

“That the evidence against the Defendants, Negroes,

establishes that they, at the time of the arrest and at all

times covered by the warrant, were members of the public

peacefully attempting to use a publicly owned facility,

to-wit: Overton Park Shell, being leased at the time of

—133—

their arrest by the Assembly of God Church, in which the

Defendants were segregated because of their race or color;

such segregation was in accordance of the policies, cus

toms, and usage of the Assembly of God Church carried

out under the color of State Law of the State of Tennessee

operating such facilities and services on a racially segre

gated basis, which policies, customs and usage violate

the due process and equal protection clauses of the 14th

Amendment to the Constitution of the United States.”

We have cases cited holding this which we can give to

the Court.

Defendants’ Motion to Dismiss

27a

II

“That the evidence offered against the Defendants,

Negroes, in support of the indictment charging them with

Disturbing Religious Worship establishes that they were,

at the time of their arrest and at all times covered by the

- 1 3 4 -

charge, peacefully worshipping with others and in the same

maimer as white persons similarly situated and at no time

did they disturb or disquiet the congregation by making

any noise or by rude and indecent behavior or by boisterous

or profane discourse nor any other act within or near said

Overton Park Shell and, therefore, the arrest of said

charge is thereby depriving them of rights without due

process of law and of equal protection of law secured by

the 14th Amendment to the Constitution of the United

States.”

III

“That the evidence establishes that prosecution of De

fendants was procured for the purpose of preventing them

from engaging in peaceful assembly with others for the

purpose of enjoying public facilities and accommodations

in tax operated facilities in the City of Memphis and

—135—

opened to the public and expressly opened to the public

on the date of August 30, 1960; and that by this prosecu

tion, prosecuting witnesses and arresting officers are at

tempting to employ the aid of the Court to enforce a

racially discriminatory policy contrary to the due process

and equal protection clauses of the 14th Amendment to

the Constitution of the United States.”

If the Court please, on this matter we also have a case,

Timms versus The State, which citation we can furnish.

Defendants’ Motion to Dismiss

28a

later, dealing with the fact that The State has the duty

of proving all of the essential elements of the indictment,

and the indictment which reads in pertinent part that they,

“Did unlawfully and willfully disturb and disquiet an as

semblage of persons met for religious worship at the Over-

ton Park Shell of Memphis-Shelby County, Tennessee, after

—136-

being refused admittance to the services therein, did force

themselves into the assembly, seated themselves among

the worshippers, and by this act did cause disruption of said

religious assembly.”

If Your Honor please, we submit that the testimony of

all the State’s witnesses failed to show they were refused

admittance to the assembly, and failed to show that they

forced their way into the Overton Park Shell. The best

the State has made out, is that one person in this group

was asked to sit in the rear. He was informed this was a

segregated assembly, that they could take seats in the

rear. This does not rise to the dignity of the criminal

statute having to do with Disturbance of Religious As

sembly.

For that reason and for reasons delegated in our written

Motion, we ask the Court to dismiss these charges.

- 1 3 7 -

D ism issa l of D e fe n d a n t s’ M otion to D ism iss

The Court: Well, of course, your Motion is not well

taken for the reason that this Court doesn’t have the au

thority to direct verdicts. It does in Civil Courts, but it

doesn’t in Criminal Courts. I can’t direct a verdict for the

State and by the same reason I can’t direct a verdict for

the Defendant.

Dismissal of Defendants’ Motion to Dismiss

29a

As far as the violation on the taking some of these

parties who went to this assembly that night, no right

was deprived them, none whatsoever.

Attorney Hooks: If the Court please—did you—(inter

rupted ).

The Court: No, I am not through.

Attorney Hooks: Oh, I am sorry.

The Court: The right to peacefully assemble and wor

ship God is a right that is paramount to all other rights.

That is written in the 1st Amendment to the Constitution

of the United States. It is not in the State Constitution.

—138—

The 1st Amendment, of course, is the beginning of the

first ten Amendments to the Constitution which is the Bill

of Bights and cannot be changed. The Congress shall pass

no act creating any religion or the free exercise thereof,

the free exercise thereof.

Now, the racial question involved here doesn’t enter

into this thing at all, as I see it. There is the attempt to

inject it here, but this Court is not going to let it he in

jected into it. If the situation were reversed, where we

would say a colored church was having a peaceful as

semblage of for the purpose of worshipping God and it

was disturbed or entered by the White, and the will of the

colored people were holding, then they would be in viola

tion of law.

Now the right to worship God as you please extends to

single and individual, to individuals or a group. They can

worship segregated, integrated, or any other manner, and

—139—

they must not be disturbed. Now that is paramount to all

other rights, Civil and otherwise. If you take that away

from the people of this country, why then we have just

Dismissal of Defendants’ Motion to Dismiss

30a

about the same situation we have in Russia today where

they have no religion and where a good many people are

not permitted to practice a religion, also with their free

assemblage where they won’t let them assemble. They are

interfered with.

So, then the Legislature in its wisdom and one of the

framers of the Constitution of this country thought enough

of it to write it into the Bill of Rights of our nation, that

Congress itself cannot interfere with the exercise of reli

gion; therefore, an individual certainly does not have that

right, and in this act here which was enacted at first in

1870 and then again in 1879 and amended 1833—no

—140—

—1801 was the first enactment, I believe, and 1858 it was

amended, and on down to 1932 it was carried over into

that Code and it now in the Tennessee Code Annotated,

Section 39-1204, which it says, “The disturbing of religious,

educational, literary or temperance assemblage, if any per

son willfully disturb, or disquiet any assemblage of per

sons met for religious worship,” and it goes on here, “or

for educational or literary purposes or as a lodge.” Of

course, we have the right under the Constitution to peace

fully assemble. That is a right that is given to us.

Now these rights that are given to us or when they are

—I would say this right to worship God peacefully was a

right that existed long before the Constitution itself, a

right that was given to man by God and it therefore be

comes the duty of all other people to respect that right.

Now that is the way I, as a Court, feel about this. I really

- 1 4 1 -

do. If these people are deprived of the right to worship

as they please, integrated, segregated, or say to the world,

Dismissal of Defendants’ Motion to Dismiss

31a

“We intend to worship tonight with people who are one-

eyed and are Chinese,” they have the sanctity of the law

thrown around them to worship, and nobody has the right

to go in there and disturb them.

There is a difference between a church and a business,

and I am just saying this for the record, not prejudicing

anyone at all, this is a matter entirely in the hands of the

Jury, and the Court will so charge the Jury at the time,

but you brought in there the 14th Amendment which doesn’t

apply in this case at all. The 1st Amendment is the one

that applies and the 14th is not a part of the Bill of Rights.

The first ten is. And the due process of law and the use

of civic sales tax supported civic facilities, that is not a

question before this Court. The question here and the only

- 1 4 2 -

question was whether that religious assembly was dis

turbed. That is all that the Jury has to decide. That is

the one issue. The National Government doesn’t enter into

it at all. You have no right to interfere with the people’s

worship. If such was done it will be found by the Jury.

Therefore, your Motion is overruled.

Dismissal of Defendants’ Motion to Dismiss

32a

The Defendants, Evander Ford, Jr., Alfred O’Neil Gross,

James Harrington Smith, Ernestine Hill, Johnnie May

Rogers, Charles Edward Patterson, and Edgar Lee James,

were convicted upon the same trial for willfully disturbing

an assemblage of persons meeting for religious purposes

(Section 39-1204, Tennessee Code Annotated), and each was

sentenced to serve sixty days in the Shelby County Penal

Farm, plus a fine of $200.00.

The Defendant, Katie Jean Robertson, was tried sepa

rately, she not being available at the time of the first trial,

and was convicted of the same offense and sentenced to

serve sixty days and fined $175.00. Since these two cases

grew out of the same set of facts and the Defendants were

acting in concert with each other, the cases were joined

for purposes of appeal.

In the case of the Defendant, Katie Jean Robertson, the

conviction must be affirmed for failure to timely file the

bill of exceptions. The Trial Court overruled the Defend

ant’s motion for a new trial on November 3, 1961. On

Friday, December 1, 1961, the Defendant moved the Court

for additional time in which to file and prepare her bill of

exceptions. This motion was granted by the Trial Judge

and the time for filing was extended thirty days from the

3rd day of December, 1961. As a result of this extension

the Defendant had until January 2,1962 in which to prepare

and file the bill of exceptions. However, the bill of excep

tions was not filed until January 4, 1962, which is two days

late. A bill of exceptions which is filed too late does not

become a part of the record in a case and cannot be looked

to for any purpose. O’Brien v. State, 193 Tenn. 361. This

Opinion o f Supreme Court

o f Tennessee

33a

leaves only the technical record before the Court and we

are unable to detect any reversible error therein.

Having disposed of Katie Jean Robertson’s case the

Court will now proceed to discuss the appeal as to the re

maining Defendants. At the outset it must be noted that

all of the proof in the record is uncontroverted. These De

fendants are negro youths and their criminal prosecution

resulted from an incident which took place in the City of

Memphis on the evening of August 30,1960. It appears that

the Assembly of God Church on this evening had leased

the “Shell”, a municipally owned amphitheater situated in

Overton Park of that city, for the purpose of conducting

a youth rally as a part of their church activities. This

meeting had received a considerable amount of advertise

ment as to time and place it was to be conducted.

The meeting commenced at 7 :30 o’clock, P.M. on this

evening. At approximately 7 :45 o’clock, P.M. the Defend

ants herein, and some other negro youths who are not on

trial here, entered the amphitheater. An usher on duty at

this entrance met these Defendants as they entered. The

usher then informed the group that it would be better if

they did not come in, that this was a meeting for the youth

of the Assembly of God Church. When the Defendants

would not leave the usher asked them to take the rear seats.

At this time the Defendant, Evander Ford, Jr., who was

the apparent leader of this group, turned and told his

group to “scatter out”. The Defendants then broke into

groups of two and simultaneously disbursed themselves

throughout the audience. Even though there were seats

available at the ends of the rows, the Defendants for the

most part proceeded to step over the people already seated

and moved to the center of the rows. The people who were

already seated began to move away and in some instances

Opinion of Supreme Court of Tennessee

34a

left the meeting. As a result of this mass entrance a gen

eral milling around was caused and an undercurrent went

up throughout the audience which caused a delay in the

service that was in progress. The police were then sum

moned and the Defendants were placed under arrest for

the offense indicated above.

The Defendants stand convicted of Section 39-1204, Ten

nessee Code Annotated, which reads as follows:

“If any person willfully disturb or disquiet any assem

blage of persons met for religious worship, or for

educational or literary purposes, or as a lodge or for

the purpose of engaging in or promoting the cause of

temperance, by noise, profane discourse, rude or in

decent behavior, or any other act, at or near the place

of meeting, he shall be fined not less than twenty dol

lars ($20.00) nor more than two hundred dollars

($200), and may also be imprisoned not exceeding six

(6) months in the county jail.”

The Defendants first argue that the statute only con

demns acts which are noisy, rude, profane, indecent, or

other similar acts and that their action was none of these,

therefore, the State has failed to make out a case against

them. The State on the other hand insists that the statute

reaches any willful disturbance of a religious assembly

regardless of how it is accomplished. This squarely presents

us with the problem of the construction of this statute.

At the outset it must be noted that this statute is not a

breach of the peace statute as such, but rather it is a statute

which is designed to protect to the citizens of this State the

right to worship their God according to the dictates of their

conscience without interruption. As a general rule these

statutes have been very liberally construed by the Court.

Opinion of Supreme Court of Tennessee

35a

Hollingsworth v. State, 37 Tenn. 518. However, in order to

determine the exact boundaries of this statute we feel that

it is necessary to review its historical development.

The first statute upon this subject made any person who

would disturb a religious assembly punishable as a rioter

at common law. Chapter 35 of the Acts of 1801 . Then by

Chapter 60 of the Acts of 1815 , the legislature enacted an

additional statute to supplement Chapter 35 of the Acts of

1801. The part of Chapter 60 of the Acts of 1815 which is

pertinent to our discussion here reads as follows:

“It shall be the duty of all justices of the peace, . . . that

whenever any wicked or disorderly person or persons

shall either by word or gesture or in any other manner

whatosever disturb any congregation which may have

assembled themselves for the purpose of worshipping

Almighty God, . . . shall immediately cause offender or

offenders to be apprehended and brought before them

or some other justice of the peace for the county in

which such offense may be committed . . . ” (Section 1,

Chapter 60, Acts of 1815) (Emphasis supplied).

Then in 1858 the first Code of this State was adopted

which contained a section that is the same as Section 39-

1204, Tennessee Code Annotated, except that it only cov

ered religious assemblies. By Chapter 85 of the Acts of

1870 this section was extended to cover educational and

literary meetings and by Chapter 209 of the Acts of 1879

the section was placed in its present form.

However, when the Code of 1858 was adopted, Chapter

35 of the Acts of 1801 and Chapter 60 of the Acts of 1815

were brought forward into that Code. Thus, the Code of

1858 contained both Chapter 35 of the Acts of 1801 and

Chapter 60 of the Acts of 1815, along with a section which

Opinion of Supreme Court of Tennessee

36a

was the same as our present Section 39-1204 after the

abovementioned amendments. This remained in this state

of affair until 1921 when the Court was called upon to

compare these various sections in Dagley v. State, 144

Tenn. 501. The Court in this case reached the conclusion

that the section which is now Section 39-1204, of our

present Code, embraced the same offense which was set

out in the section containing Chapter 35 of the Acts of

1801 and Chapter 60 of the Acts of 1815.

It will be noted from the quoted part of Chapter 60

of the Acts of 1815 that it constituted an offense to disturb

a religious assembly in any manner whatsoever. There

fore, in the light of the conclusion reached by the Court

in the Dagley case, supra, i.e., the offense set out in Chap

ter 60 of the Acts of 1815 was included in the offense

prescribed in what is now Section 39-1204, Tennessee Code

Annotated, the only logical result to be reached here is

that the phrase “or any other act” which appears in Sec

tion 39-1204, Tennessee Code Annotated, is all encompass

ing and it is unlawful for anyone to willfully disturb a

religious assembly in any manner whatsoever.

In view of the construction which must be placed upon

Section 39-1204, Tennessee Code Annotated, we are of the

opinion that these Defendants violated the statute. Un

questionably the act was willful. These Defendants had

been tendered seats at this meeting even though they were

at first asked not to come in. However, the Defendants

would not take these seats and upon command of their

leader to “scatter out” they disbursed themselves through

out the audience simultaneously. The proof shows that

there were seats available at the ends of the rows where

they could be seated, but they, nevertheless, proceeded

to step over the people already seated in an effort to get

Opinion of Supreme Court of Tennessee

37a

to the center of the rows. These acts are wholly incon

sistent with any theory that these Defendants came with

the intent of joining in the meeting. The very precise

manner in which this maneuver was executed indicates

very clearly that these Defendants had planned their

course of action before arriving at the meeting. This

leaves us no choice but to conclude that this was a well

organized scheme designed to create an incident.

This brings us to the question of whether or not their

act disturbed the meeting. The record shows that when

the Defendants descended upon this meeting in mass and

began to step over the persons already seated it caused

these people to move to let them in and some to move

away, and others to leave the meeting. Reverend Scruggs,

the official in charge of the meeting, stated that there was

quite a commotion caused by this act with all these people

moving around and further that they had to delay the

service. The Court in the case of Bolt v. State, 60 Tenn.

192, ruled that it was only necessary that the act attract

the attention of any part or parts of the assembly to

constitute a violation of the statute. This act undoubtedly

attracted the attention of a great portion of this assembly

if not all of it, but the Defendants’ act even went further

than that which is required under the rule in the Bolt case,

supra, because their act completely interrupted the ser

vice. We are, therefore, of the opinion that there is more

than ample proof contained in this record to support the

verdict of the jury.

The Defendants next argue that their constitutional

rights are being violated by this conviction because this

is a publicly owned facility and they could not be excluded.

First, it must be noted that the Defendants were tendered

seats at this meeting even though they had been denied

Opinion of Supreme Court of Tennessee

38a

Opinion of Supreme Court of Tennessee

admission at the outset. Second, this is not a suit to

enjoin a discriminatory practice, nor is it a damage suit

based upon the violation of civil rights, but rather a crim

inal action charging the Defendants with willfully disturb

ing a religious assembly. Whether these Defendants had

a right to be at the place where this religious meeting was

being conducted is not an issue in this lawsuit. The sole

issue here is whether or not these Defendants willfully

disturbed the meeting that was being held there and we

have hereinbefore determined this question adversely to

the Defendants’ contention.

Lastly, the Defendants contend that the verdict of the

jury is so severe that it evinces passion, prejudice and

caprice and, therefore, is void. The evidence as presented

by the record clearly shows them to be guilty of violating

this particular statute. We have diligently searched this

record and are unable to find any mitigating circumstances

which would warrant us in disturbing the verdict of the

jury.

Judgment affirmed.

P b e w i t t , C.J.

39a

No. 37462

Order o f Supreme Court

o f Tennessee

E vander F ord, J r., e t a l.,

—v.—

S tate oe T e n n e s s e e .

Shelby Criminal.

Affirmed.

Came the plaintiffs in error b y counsel, and also came

the Attorney General on behalf of the State, and this

cause was heard on the transcript of the record from the

Criminal Court of Shelby County; and upon consideration

thereof, this Court is of opinion that there is no reversible

error on the record, and that the judgment of the Court

below should be affirmed, and it is accordingly so ordered

and adjudged by the Court.

It is therefore ordered and adjudged by the Court that

the State of Tennessee recover of Evander Ford, J r . ;

Alfred O’Neil Gross; James Harrington Smith; Ernestine

Hill; Johnnie May Rogers; Charles Edward Patterson;

and Edgar Lee James; the plaintiffs in error, for the use

of the County of Shelby, the sum of $200.00 each, the fine

assessed against Evander Ford, Jr. et al. in the Court

below, together with the costs of the cause accrued in this

Court and in the Court below, and execution may issue

from this Court for the cost of the appeal.

40a

Order of Supreme Court of Tennessee

It is further ordered by the Court that the plaintiffs

in error be confined in the county jail or workhouse of

Shelby County, subject to the lawful rules and regulations

thereof, for a term of sixty days each, and that after

expiration of the aforesaid term of imprisonment, they

remain in the custody of the Sheriff of Shelby County until

said fine and costs are paid, secured or worked out as re

quired by law, and this cause is remanded to the Criminal

Court of Shelby County for the execution of this judgment.

The Clerk of this Court will issue duly certified copies

of this judgment to the Sheriff and the Workhouse Com

missioner of Shelby County to the end that this judgment

may be executed.

3/7/62

41a

Order o f Supreme Court

o f Tennessee

K a tie J ea n R obertson ,

-v.-

S tate op T e n n e s s e e .

Shelby Criminal.

Affirmed.

Came the plaintiff in error by counsel, and also came

the Attorney General on behalf of the State, and this

cause was heard on the transcript of the record from the

Criminal Court of Shelby County; and upon consideration

thereof, this Court is of opinion that there is no reversible

error on the record, and that the judgment of the Court

below should be affirmed, and it is accordingly so ordered

and adjudged by the Court.

It is therefore ordered and adjudged by the Court that

the State of Tennessee recover of Katie Jean Robertson,

the plaintiff in error, for the use of the County of Shelby,

the sum of $175.00, the fine assessed against Katie Jean

Robertson in the Court below, together with the costs of

the cause accrued in this Court and in the Court below,

and execution may issue from this Court for the cost of

the appeal.

It is further ordered by the Court that the plaintiff

in error be confined in the county jail or workhouse of

Shelby County, subject to the lawful rules and regulations

42a

thereof, for a term of sixty days, and that after expiration

of the aforesaid term of imprisonment, she remain in the

custody of the Sheriff of Shelby County until said fine

and costs are paid, secured or worked out as required by

law, and this cause is remanded to the Criminal Court of

Shelby County for the execution of this judgment.

The Clerk of this Court will issue duly certified copies

of this judgment to the Sheriff and the Workhouse Com

missioner of Shelby County to the end that this judgment

may be executed.

3/7/62

Order of Supreme Court of Tennessee

Order Denying Rehearing

K a tie J ea n R obertson , E vander F ord, J r ., et a l.,

-v.

S tate oe T e n n e s s e e .

Shelby Criminal.

Petition to Rehear Denied.

This cause coming on further to be heard on a petition

to rehear and reply thereto, upon consideration of all which

and the Court finding no merit in the petition, it is denied

at the cost of the petitioner.

5/4/62

43a

I n t h e

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

F or t h e W estern D istr ic t of T e n n e s s e e

M e m p h is D iv isio n

Petition for Writ o f Habeas Corpus

E vander F ord, J r ., e t a l.,

•v.—

Petitioners,

T h e H onorable W il l ia m N. M orris, J r., Sheriff of Shelby

County, Tennessee, and T h e M e m p h is B ail B ond A gen cy ,

Respondent.

To the Honorable United States District Court for the

Western District of Tennessee:

The petition of Evander Ford, Jr., Alfred O. Gross,

James Harrison Smith, Ernestine Hill, Johnnie May Rog

ers, Charles Edward Patterson, Edgar Lee James, and

Katie Jean Robertson respectfully shows:

I .

The jurisdiction of this court is invoked pursuant to

Title 28, United States Code, Section 2241-3 and Section 1,

Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution.

II.

The petitioners are citizens of the United States and

residents of the State of Tennessee. The petitioners are

ail members of the Negro race.

44a

III.

The petitioners seek by this action to obtain review of

their conviction for an alleged violation of wilfully dis

turbing a religious assembly (Section 39-1204, Tenn. Code

Ann.). The judgment was rendered by the Criminal Court

of Shelby County, Tennessee, on June 20, 1961.

IV.

The petitioners, through the making of appropriate bail

bond, have not served the jail sentences nor paid the fines

imposed upon them by the Shelby County Criminal Court.

Petitioners are advised and believe that within ...........they

will be served with [a capias] for their arrest. When

that circumstance occurs, petitioners will be required to

start serving the jail term illegally imposed upon them by

the Shelby County Criminal Court.

V.

The convictions of petitioners are violative of the due

process of law and equal protection of the laws as guaran

teed by the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of

the United States; the said convictions were based upon

arrests made by Memphis police officers to enforce that

City’s illegal policy of racial segregation in its public parks.

VI.

Petitioners’ convictions were secured despite the absence

of evidence of willful disturbance of a religious assembly

as required by both the state law under which the arrests

were prosecuted and the due process clause of the Four

teenth Amendment. The evidence before the court was

simply that (1) the accused were Negroes; (2) the accused

Petition for Writ of Habeas Corpus

45a

sought to use a public facility located in a public park

then being used by white persons for a religious service

to which the public was invited, and (3) a few white people

then present in the auditorium moved out of their seats

when the Negroes seated themselves in the auditorium.

VII.

Petitioners have exhausted every available remedy in

the courts of Tennessee and certiorari before the United

States Supreme Court has been sought as set forth below.

At the conclusion of testimony in their trial on June 20,

1961 petitioners Ford, Gross, Smith, Hill, Rogers, Patter

son and James made a motion to the trial court to dismiss

the charges on the ground that such arrests deprived peti

tioners of their rights under the due process and equal

protection clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment. The

court denied the motion.

Petitioners were convicted on June 20, 1961 [petitioner

Robertson was convicted on September 25, 1961] and filed

a motion for a new trial, again raising the issue of denial

of their Fourteenth Amendment rights to use public facil

ities on a nonsegregated basis. The motion was denied on

August 15, 1961. [Petitioner Robertson made a motion for

a new trial which raised the same federal questions at the

conclusion of her trial. The motion was overruled on No

vember 3, 1961.]

The cases were consolidated for appeal by consent of

the Supreme Court of Tennessee. That court affirmed the

judgment of the Criminal Court and denied an application

for rehearing on May 4, 1962. Robertson, et al. v. State,

-----Tenn.------ .

Petition for Writ of Habeas Corpus

46a

Petition for Writ of Habeas Corpus

VIII.

After the petition for certiorari was filed before the

Supreme Court, in 1962, but on or before certiorari was

denied on June 22, 1964, four eases important to this pro

ceeding were decided by the Supreme Court:

1. In Watson v. City of Memphis, 373 U.S. 526 (1963),

the Supreme Court had before it a record showing that at

the time of petitioners’ arrest, Overton Park, a public

park on which the facility where petitioners were arrested

is located, was racially segregated pursuant to City policy.

The Supreme Court held that racial segregation in Mem

phis’ public parks, necessarily including Overton Park,

must be completely and immediately ended.

2. In Peterson v. City of Greenville, 373 U.S. 244 (1963),

the court reversed trespass convictions of Negroes who,

after having been refused service at a lunch counter be

cause of race, remained seated over the manager’s protest.

There, a city ordinance forbade nonsegregated food ser

vice, but the State contended that the arrests were made

pursuant to the manager’s request and not the segregation

ordinance. The Court ruled, however, that:

“When a State agency passes a law compelling persons

to discriminate against other persons because of race,

and the State’s criminal processes are employed in a

way which enforces the discrimination mandated by

that law, such a palpable violation of the Fourteenth

Amendment cannot be saved by attempting to separate

the mental urges of the discriminators.” 373 U.S. at

248. See also Lombard v. Louisiana, 373 U.S. 267.

3. In Lombard v. Louisiana, 373 TT.S. 267 (1963), the

Court reversed trespass convictions of Negroes who re

fused to leave a refreshment counter in New Orleans after

being advised by the management that the counter was

operated on a segregated basis and served only white

patrons. Segregated facilities were not dictated by any

statute or ordinance in New Orleans, but the Mayor and

Superintendent of Police had issued statements warning

that persons participating in sit-in demonstrations would

be arrested. The Court ruled that the convictions as in

Peterson, supra, had been commanded by the voice of the

State and could not stand.

4. In Robinson v. State of Florida,----U.S.----- (1964),

the Court reversed convictions of Negroes and whites who

were refused service at a Miami restaurant. Again, rely

ing on the rationale of Peterson, supra, and Lombard,

supra, the Court ruled that State health regulations re

quiring separate facilities for each race connoted a State

policy of segregation which placed discouraging burdens

on any restaurant serving the two races together.

IX.

The petitioners are restrained pursuant to sentence and

fines that are illegal and void, in that petitioners were de

nied due process and equal protection of the laws secured

by the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the

United States. The facts and circumstances under which

denial of petitioners’ constitutional rights occurred are as

follows:

(a) On August 30, 1960, petitioners and several other

Negro persons sought to attend a public rally, advertised

Petition for Writ of Habeas Corpus

48a

as such in a daily newspaper of general circulation, spon

sored by an all-white religious organization and held in

an auditorium owned and operated by the City of Mem

phis, located in Overton Public Park. The Negroes were

properly dressed, used no rude or profane language and

engaged in no improper conduct.

(b) Upon their attempt to enter the auditorium the Ne

groes were advised by an usher of the sponsoring organ

ization that they should leave because the meeting was

“segregated” and they were not wanted there.

(c) When the Negroes refused to leave, the usher offered

them seats far behind the audience of white persons. This

offer was refused by the Negroes, who thereupon pro

ceeded to take vacant seats in various parts of the audi

torium in the same manner as several white late entrants