Bolling v. Sharpe Brief for Amici Curiae

Public Court Documents

December 1, 1952

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Bolling v. Sharpe Brief for Amici Curiae, 1952. 6a868310-ca9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/6e4eef5b-aca6-4500-abd7-22ce3a24770d/bolling-v-sharpe-brief-for-amici-curiae. Accessed February 20, 2026.

Copied!

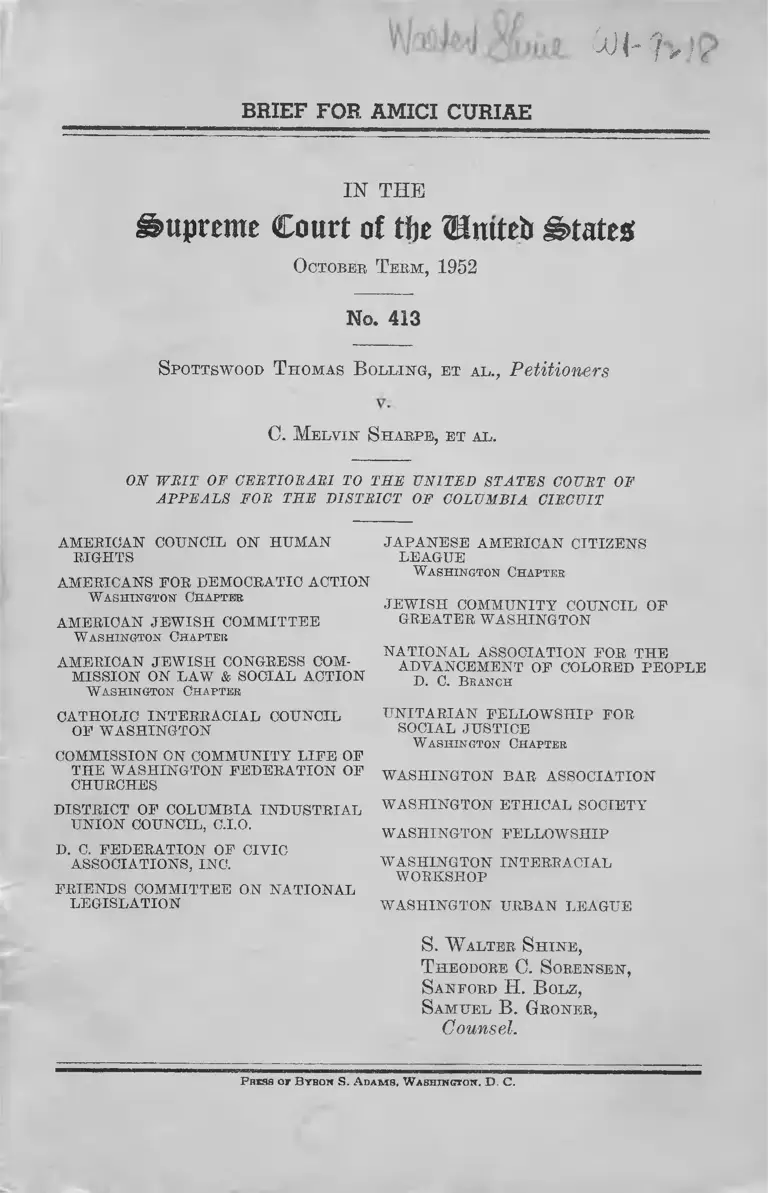

BRIEF FOR AMICI CURIAE

Oj h * / r

IN THE

Supreme Court of tf>t Hmteb States

O c to b er T e r m , 1952

No. 413

S p o ttsw o o d T h o m a s B o l l in g , e t a l ., Petitioners

C . M e l v in S h a r p e , e t a l .

ON W R IT OF CERTIORARI TO T H E U NITED S T A T E S COVET OF

A PP E A L S FOE T H E D ISTRICT OF COLUMBIA CIRCUIT

AMERICAN COUNCIL ON HUMAN

RIGHTS

AMERICANS FOR DEMOCRATIC ACTION

Washington Chapter

AMERICAN JEW ISH COMMITTEE

W ashington Chapter

AMERICAN JEW ISH CONGRESS COM

MISSION ON LAW & SOCIAL ACTION

W ashington Chapter

CATHOLIC INTERRACIAL COUNCIL

OF WASHINGTON

COMMISSION ON COMMUNITY LIFE OF

THE WASHINGTON FEDERATION OF

CHURCHES

DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA INDUSTRIAL

UNION COUNCIL, O.L0.

D. C. FEDERATION OF CIVIC

ASSOCIATIONS, INC.

FRIENDS COMMITTEE ON NATIONAL

LEGISLATION

JAPANESE AMERICAN CITIZENS

LEAGUE

Washington Chapter

JEW ISH COMMUNITY COUNCIL OF

GREATER WASHINGTON

NATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR THE

ADVANCEMENT OF COLORED PEOPLE

D. C. B ranch

UNITARIAN FELLOWSHIP FOR

SOCIAL JUSTICE

W ashington Chapter

WASHINGTON BAR ASSOCIATION

WASHINGTON ETHICAL SOCIETY

WASHINGTON FELLOWSHIP

WASHINGTON INTERRACIAL

WORKSHOP

WASHINGTON URBAN LEAGUE

S . W a l t e r S h i n e ,

T h eo d o r e C . S o r e n s e n ,

S a n f o r d H. B o lz ,

S a m u e l B . G r o n e r ,

Counsel.

P hkss of B yhqn S . A dam s, W ashington. D . C.

INDEX.

Page

Interest of Amici Curiae ............................................. 1

Statement of the C ase.................................................. 2

The Questions to Which This Brief Is Addressed . . . . 3

Summary of Argument................... 4

Argument....................................................................... 5

I. Separation of School Children by Skin Color or

Ancestry Has No Warrant in Twentieth Century

Community Experience, Proper Legislative Pur

pose, or Scientific Understanding and Is Therefore

a Meaningless Classification Violative of the Fifth

Amendment ........................................................... 5

A. Community experience demonstrates the in

validity of racial segregation in the District of

Columbia or anywhere in the United States . . . 7

1. Deterioration of patterns of segregation . . . . 7

2. The prophesied community resistance to

change ........................................................ 10

B. Declared legislative prohibitions against segre

gation in other areas of activity in the District

of Columbia demonstrate the further irration

ality of school segregation................................ 16

C. Present scientific understanding discredits tra

ditional concepts of ‘‘race ” ............................... 17

II. The Fact That Congress Made Provision for the

Establishment of Schools for Negro Children in the

District of Columbia Before the Adoption of the

Fourteenth Amendment Does Not Justify the

Conclusion That the Fourteenth Amendment Was

Intended to Permit Eacial Segregation.............. 18

Conclusion...................................................................... 24

11 Index Continued.

A p p e n d ix P a 8'e

Table I

List of Cities in Southern and Border States in

Which Some Schools, Colleges and Universities

Have Been Recently Integrated........................... 27

Table II

Schools, Colleges and Universities in the District

of Columbia and Environs Which Will Accept

Both White and Negro Students ......................... 28

A. Nursery, Elementary and High Schools......... 28

B. Colleges and Universities................................ 28

Table III “ The School Doors Open Wide”

Examples of Recent Admission of Negroes to Edu

cational Institutions in the South and Border

A reas....................................................................... 29

A. In the South .................................................... 29

B. In Southwestern, Border and Other Areas . . . . 33

Sources for information in Table I I I .................... 37

Table IV “ The Old Order Changeth”

(Representative Departures From Segregation

Throughout the Nation) ........................................ 38

A. In Public Accommodations ............................. 38

B. In the Field of Education............................... 42

C. In Voluntary Associations ............................... 45

D. In Religious Bodies......................................... 49

E. In Employment...... .......................................... 50

F. In Entertainment and Athletics...................... 51

Sources for Table I V ............................................. 54

Index Continued. in

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES.

Cases : Page

Adams v. Terry, 193 F. (2d) 600 ............................... I I

Baskin v. Brown, 174 F. (2d) 391............................. 14

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60, 81 (1917)............. 13

Butts v. Merchants and Miners Trans. Co., 230 U. S.

126 (1913)............................................................... 16

Carr v. Corning, 182 F. (2d) 14, 33 .........4,15,19, 20, 23

Chance v. Lambeth, 186 F. (2d) 879, 881, 882-883 . . . . 13

Chapman v. King, 154 F. (2d) 460, cert, denied, 327

U. S. 800 ............................................ 14

Civil Rights Cases, 109 U. S. 3 (1883)....................... 16

Davis v. Schnell, 81 F. Supp. 872, affirmed, 336 U. S.

933 ........................................................................... 14

Dean v. Thomas, 93 F. Supp. 129............................... 14

District of Columbia v. John R. Thompson Co., 81

A. (2d) 249 .............................................................. 16

Draper v. St. Louis, 92 F. Supp. 546, 549 ................ 12

Ex parte Endo, 323 U. S. 283 (1944) ....................... 5

Grovy v. Townsend, 295 U. S. 45 (1935) ............ 14

Henderson v. United States, 339 U. S. 816 (1950)

12,13,14

Hirabayashi v. United States, 320 U. S. 81, 92, 100

(1943) ..................................................................... 5,18

Hurd v. Hodge, 334 U. S. 24 (1948) ....................... 24

Korematsu v. United States, 323 U. S. 214, 220

(1944) .....................................................................5,10

McLaurin v. Oklahoma Board of Regents, 339 U. S.

637 (1950)............................................................ 8,9,13

Mitchell v. Wright, 154 F. (2d) 924, cert, denied, 329

U. S. 733 .................................................................. 14

Morgan v. Virginia, 328 U. S. 373 (1946)................ 12

Nixon v. Condon, 286 U. S. 73 (1932)....................... 14

Nixon v. Herndon, 273 U. S. 536 (1927).................... 14

Passenger Cases, 7 How. 283, 470 (1849) ................ 6

Perry v. Cyphers, 186 F. !(2d) 608............................. 14

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U. S. 537 (1896) .................6, 24

Rice v. Elmore, 165 F. (2d) 387, cert, denied, 333

U. S. 975 ................................................................. 14

Schnell v. Davis, 336 U. S. 933 (1949) .................... 14

Smith v. Allwright, 321 U. S. 649 (1944) ................ 14

Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U. S. 629 (1950)................ 8, 9,11,

13,14, 20

IV Index Continued.

Page

Terry v. Adams, 193 F. (2d) 600, cert, granted, No

vember 12, 1952 .................................................... 14

Weems v. United States, 217 U. S. 349, 373-374, 378

(1910).......................................................................6,19

White v. Clements, 39 Ga. 232, 269 .......................... 13

Wolf v. Colorado, 338 U. S. 25, 27 (1949)................ 6

S t a t u t e s :

Act of April 16, 1862 (12 Stat. 376) ......................... 22

Act of May 20, 1862 (12 Stat. 394) .......................... 22

Act of May 21, 1862 (12 Stat. 407) .......................... 22

Act of June 25, 1864 (13 Stat. 187, 191) ................ 20, 22

Act of March 3, 1865 (13 Stat, 536) ........................ 16

Act of April 9, 1866 (14 Stat. 27) ............................. 24

Act of July 23, 1866 (14 Stat. 216).......................... 23

Act of July 28, 1866 (14 Stat. 343) .......................... 23

Act of May 31, 1870 (16 Stat. 140) .......................... 24

Act of June 22, 1874 (18 Stat. part 2) .................... 20

Act of March 1, 1875, “ Civil Rights Act of 1875”

(18 Stat. 335) ...................................................... 16,21

Art. 1661.1, Sec. 2, Vernon’s Statutes of Texas, An

notated (1947) ...................................................... 5

M is c e l l a n e o u s :

Benedict & Weltfish, Races of Mankind.................... 18

Boyd, Genetics and the Races of M an ..................... 17

Bryan, History of the National Capital, Vol. II

(1916), pp. 137-138, 389, 524-528 ........................... 22

Civil Rights in the United States in 1951, pp. 18, 90

12,15

Comas, Racial Myths (UNESCO, 1951) ............... 18

Comment, 18 Univ. Chi. L. Rev. 769, 771-775, 781

(1951) ................................................................... 11,13

Cong. Globe, 37th Cong., 3d Sess. 1326-1327 (1863). . 22

Cong. Globe, 43rd Cong., 1st Sess., 4153 (1874),

pp. 1326-1327 .........................................................

2 Cong. Record 4153 (1874) ...................................... 14

3 Cong. Record 981-982, 997, 1002 (1875) .................. 14

Flack, The Adoption of the Fourteenth Amendment

(1908) ............................................................ .20,23,24

Frank and Munro, The Original Understanding of

“Equal Protection of the Laws,” 50 Col. L. Rev.

131, 153-162 (1950) ..............................................20,24

Index Continued. v

Page

Glass and Li, “ Report on the Dynamics of Racial

Intermixture,” Annual Meeting of the American

Institute of Biological Sciences at Cornell Univer

sity, New York Times (September 8, 1952) 33:8. .

Jackson, Luther P., “ Race and Suffrage in the

South Since 1940,” New So-uth, Vol. 3, pp. 1-26

(1948) ................ . . . .......................... ................... 15

Klineherg, Characteristics of the American Negro. . 18

Krogman, An Anthropologist Looks at Race, 7 In-

tercultural Education News 1 (Nov. 1945)........... 17

LaFarge, The Race Question and the Negro ......... 17

Lewis, The Crisis That Never Came Off, The Re

porter, 1:12 (Dec. 6, 1949) .................................. 13

Note, 61 Yale L. J. 730, 738-743 (1952) .................... 13

“ Opportunities in Interracial Colleges” , National

Scholarship Service and Fund for Negro Students

(1951) ..............................................................• 35

Redfield, What We Do Know ah out Race, 57 Scien

tific Monthly 193 (Sept. 1943) .............................. 17

Roche, Catholic Colleaes and the Negro Student

(1948) .................... .................. ........................... 35

Sorensen, “The School Doors Swing Open”, New

Republic, 127:13 (Dec. 15, 1952) ........................... 36

Special Report of the Commissioner of Education on

the Condition and Improvement of Public Schools

in the District of Columbia, p. 253, H, Rep., Ex.

Doc. No. 315, 41st Cong., 2d Sess. (1871) ............ 22

“ Staff Monograph on Higher Education for Negroes

in Texas” , Texas Legislature Council (1951)... . 35

“ Stakes Are Costly in Play for Texas,” New York

Times (Sept. 23, 1952) ......................................... 15

Statement by Experts on Race Problems, UNESCO

(July 18, 1950) . . . ._.............................. ............., 17

“ The American Negro in College”, 1949-1950, Crisis,

Vol. 57, No. 8, p. 488 ................. ..................; . 36

“ The American Negro in College, 1950-1951, Crisis,

Vol. 58, No. 7, p. 445 ............................................. 36

“ Toward Equality in Education”, N.A.I.R.O. (1952) 35

Washington Post, Nov. 29, 1952 .............................. 15

Wilkins, Roy, “ A Decade in Race Relations,” Amer

ica (June 16, 1951), pp. 287-289 ........................... 15

IN THE

S u p re m e C o u r t of tlje WnitzU S ta te s

O c to b er T e r m , 1952

No. 413

S po ttsw o o d T h o m a s B o l l in g , e t a l ., Petitioners

v.

C. M e l v in S h a r p e , e t a l .

ON W B IT OF CERTIORARI TO T H E UNITED ST A T E S COURT OF

A P P E A L S FOR TH E DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA CIRCUIT

BRIEF FOR AMICI CURIAE

INTEREST OF AMICI CURIAE

This case deals with the question whether children

in the public school system of the Nation’s Capital may,

consistently with the Constitution and laws of the United

States, be separated by groups solely on the basis of skin

color or the origin of their ancestors.

The undersigned submit this brief because our organiza

tions represent groups of Americans in the Washington

2

community and throughout the nation of many creeds and

many races who are deeply committed to the preservation

and extension of the democratic way of life and who reject

as inimical to the welfare and progress of our country

artificial barriers to the free and natural association of

peoples, based on racial or creedal differences. We believe

this to be of especial importance in the Nation’s Capital.

We are united in the belief that every step taken to make

such differences irrelevant in law, as they are in fact, will

tend to cure one of our democracy’s conspicuous failures to

practice the ideals we proclaim to the world, and to bring

us closer to that peace and harmony with other peoples

throughout the world for which we all strive.

We submit this brief out of a sense of urgency which

compels us to speak out for great segments of the com

munity on behalf of a good and just cause. We are con

vinced that the great democratic principles of our Consti

tution are denied when racism permeates and shapes the

institutions in which the children of the Capital of the

Nation receive their schooling.

We submit this brief, finally, in the knowledge that the

progress and welfare of a democratic community and the

best contributions of all its people toward enriching the

life, the intellect, and the spirit of the community can be

achieved only from the untrammeled association of fellow-

citizens without the interposition, especially by government,

of barriers based on race.

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

This case is here on writ of certiorari to the United

States Court, of Appeals for the District of Columbia Cir

cuit, granted while the case was pending in that court on

appeal from a judgment of the United States District Court

for the District of Columbia granting a motion to dismiss

the complaint. The petitioners are minors and their par

ents, citizens of the United States and residents of the Dis

trict of Columbia, are suing on behalf of themselves and

3

others similarly situated. The respondents here are mem

bers of the school hoard and officials of the public school

system of the District of Columbia.

The complaint alleged that the minor petitioners applied

for enrollment in the Sousa Junior High School of the Dis

trict of Columbia and were denied enrollment solely be

cause of their race or color and that they appropriately

exhausted all administrative remedies for correction of that

denial. It alleged inter alia that their exclusion from the

school denied them due process of law, in violation of the

Fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution and

Title 8, Sections 41 and 43 of the United States Code; and

constituted a bill of attainder prohibited by Article 1, Sec

tion 9, clause 3 of the Constitution. The complaint sought

a declaratory judgment that the respondents had no right

to exclude the minor petitioners from the Sousa School

because of their race or color and an injunction restraining

the respondents from such exclusion.

Bespondents, without denying any of the allegations of

the complaint, filed a motion to dismiss which was granted

by the District Court without an opinion.

THE QUESTIONS TO WHICH THIS BRIEF IS ADDRESSED

The undersigned amici curiae believe that racial segrega

tion in the District of Columbia public schools is unconsti

tutional. We refrain here from presenting such of our

reasons as would parallel those presented in the brief of

the petitioners already filed herein. We confine ourselves

to the following two questions which we feel merit fuller

discussion and on which we possess some special com

petence :

1. Does separation of school children by skin color

or ancestry have any warrant in twentieth century

community experience, proper legislative purpose, or

scientific understanding?

2. Does the fact that Congress made provision for

the establishment of schools for Negro children in the

4

District of Columbia before the adoption of the Four

teenth Amendment justify the conclusion that the

Fourteenth Amendment was intended to permit racial

segregation?

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

1. Facial classifications are not permissible in our de

mocracy except only under the most dire of emergencies

such as the “ crisis of war” . The conventional standards

of “ reasonableness” to test legislative action do not come

into play when racial criteria are involved. Nor, even if it

were relevant, is there any reasonable basis for separating

school children by skin color. Examination of community

experience in the District of Columbia and throughout the

country discloses vast areas of activity in which the mem

bers of the public both voluntarily and by government ac

tion have departed from patterns of segregation and asso

ciate free of color restrictions. No rational basis exists to

single out school children for racial separation.

The predictions of defiance of a decision invalidating

racial segregation in schools or of difficulties resulting

therefrom are neither novel nor warranted. They are not

justified by community experience, history, morality, or

law. To assert such factors implies that Constitutional

rights, must await the consent of those who withhold them.

Present day scientific knowledge discredits traditional

concepts of “ race.” Continued enforcement of legislative

action based on assumed distinctions formerly attributed

to such concepts is not rational.

2. In Carr v. Corning, 182 F. 2d 14, it was held that Con

gress ’ establishment of public schools for Negroes before

the ratification of the Fourteenth Amendment “ conclu

sively supports” the determination that the Amendment

permitted segregation in schools. This misconceives the

chronology of the events of that day and gives a completely

distorted significance to the school statutes.

5

ARGUMENT

I.

SEPARATION OF SCHOOL CHILDREN BY SKIN COLOR OR

ANCESTRY HAS NO WARRANT IN TWENTIETH CENTURY

COMMUNITY EXPERIENCE, PROPER LEGISLATIVE PU R

POSE, OR SCIENTIFIC UNDERSTANDING AND IS THERE

FORE A MEANINGLESS CLASSIFICATION VIOLATIVE OF

THE FIFTH AMENDMENT

This brief documents what twentieth-century America

knows: racial segregation is not—and never was—in

tended to achieve any legitimate legislative goal hut is a

continuing attempt to maintain some vestiges of the slave

system of the nineteenth century.

Classification by “ race”1 has been permitted by this

Court to sustain governmental action only during the major

crisis of the twentieth century and then only after “ the

most rigid scrutiny” had disclosed “ circumstances of dire

emergency and peril” stemming from “ the crisis of war

and threatened invasion.” 2

Though we do not suggest the propriety of even this lim

ited impairment of the constitutional safeguards for the

individual, we point out that these instances were occa

sioned only by extreme cases of national peril. It is only

at such times that racial designations may become the basis

for governmental action. No conventional problems and

no ordinary standard of “ reasonableness” may justify a

transgression of the overriding principle that racial dis

tinctions are odious.

1 We use the term “ race” only for simplicity of expression. We

submit it has no meaning relevant to legal problems. See Section

C, infra, p. Tf. For purposes of brevity we have also referred

generally to "skin color” as the basis adopted for segregation.

Analyzed carefully, the real basis for segregation of Negroes stem

ming from the institution of slavery, lies in the birthland of the in

dividual’s forebears (i.e., Africa) rather than in skin color alone.

For these reasons many statutes refer generally to “ persons of

African descent.” Cf. Art. 1661.1, Sec. 2, Vernon’s Statutes of

Texas, Annotated (1947).

2 Hirabayashi v. United States, 320 U. S. 81, 92 (1943), and

Korematsu v. United States, 323 U. S. 214, 220 (1944). Cf. Ex

parte Endo, 323 U. S. 283 (1944).

6

Moreover, governmental classification at any time must

comport with what is fundamentally just. This is the es

sence of due process, a term of no fixed content. The “ es

sentials of fundamental rights” are not “ confined within

a permanent catalogue,” for it “ is of the very nature of

a free society to advance in its standards of what is deemed

reasonable and right.” Wolf v. Colorado, 338 U. S. 25, 27

(1949). And the question whether a classification separat

ing school children solely by race is constitutionally per

missible today cannot be answered by looking backward to

yesterday. Constitutional principles “ may acquire mean

ing as public opinion becomes enlightened by a humane

justice.” 3 For this reason, the “ boot-strap” arguments

of the School Board in this case, as in all others which rely

upon the authority of Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U. S. 537,

without reexamining its premises, cannot justify this

Court’s failing to do so. Passenger Cases, 7 How. 283, 470

(1849). We submit that the validity of continuing today

to separate school children solely according to a skin-color

8 Weems v. United States, 217 U. S. 349 (1910):

pp. 373-374: “ Time works changes, brings into existence new

conditions and purposes. Therefore a principle to be vital must

be capable of wider application than the mischief which gave it

birth. This is peculiarly true of constitutions. They are not

ephemeral enactments, designed to meet passing occasions. * # *

The future is their care and provision for events of good and bad

tendencies of which no prophecy can be made. In the application

of a constitution, therefore, our contemplation cannot be only of

what has been but of what may be. Under any other rule a con

stitution would indeed be as easy of application as it would be

deficient in efficacy and power. Its general principles would have

little value and be converted by precedent into impotent and life

less formulas. Rights declared in words might be lost in reality.

And this has been recognized. The meaning and vitality of the

Constitution have developed against narrow and restrictive con

struction. * * * The construction of the Fourteenth Amendment is

# # an example for it is one of the limitations of the Constitu

tion. ’ ’

p. 378: “ The clause of the Constitution in the opinion of the

learned commentators may be therefore progressive, and is not

fastened to the obsolete but may acquire meaning as public opinion

becomes enlightened by a humane justice.”

7

classification must be tested in the light of today’s known

community and social experience, declared legislative pur

poses and present scientific understanding. Tested ac

cordingly, separation of children in public schools on the

basis of skin-color alone is completely without rational

basis in the United States in the twentieth century.

A. Community experience demonstrates the invalidity of racial

segregation in the District of Columbia or anywhere in

the United States.

1. DETERIORATION OP PATTERN'S OF SEGREGATION.

As this community’s experience is examined, the lack of

consistency and indeed of plain common sense involved in

the erection of racial barriers between groups of school

children is dramatically exposed. A brief glance at Table

IV (Appendix, infra) shows the vast range of public ac

tivity in which this city engages free of color restrictions.

Washingtonians mingle today without regard to skin color

in many restaurants, movies, hotels, libraries, swimming

pools, golf courses, tennis courts, and playgrounds, in all

legitimate theatres, streetcars and busses, art galleries, and

music halls, and in every public building, and every audi

torium in the city. They attend inter-racial nursery

schools, parochial schools, colleges, law schools and medical

schools. (Table II, Appendix, infra.)

On what basis, then, may they rationally be precluded

from doing so in public schools? If people, young and old,

can live next door to each other in apartment houses, can

walk or ride together as far as school doors, and can enter

together in private schools, what proper reason may be

adduced to prevent them from entering those doors to

studv together in public schools established in the interests

of all the people, by a government dedicated to democracy?4

4 The President-elect has pledged himself to remove “ every

vestige of segregation” in the Nation’s Capital to the extent of the

means at his command. But this is a goal which, as this case

proves, cannot he achieved by executive action alone.

8

Moreover, segregation in schools has been abandoned in

practice in so great a portion of this country, including the

South, as to make its continuation anywhere impossible to

justify in principle. Compiled in the Appendix, infra, is a

list of those communities, in the South and border areas,

where Negro students have been recently admitted to

formerly all-white schools. (Table I). This list, which is

representative but by no means exhaustive, marks the

unanimously successful integration, in varying degrees, of

colored and white students in educational institutions in

over 85 communities in such areas. (There is of course no

need to detail the vast areas of the North where legal seg

regation has never been practiced.)

These are developments of only the past several years,

chiefly following this Court’s action in Sweatt v. Painter,

339 U. S. 629 and McLaurin v. Oklahoma, 339 U. 8. 637, in

1950. In that short time, one or more educational institu

tions in practically every Southern, Southwestern and Bor

der state have opened their doors to Negroes, who had pre

viously been excluded altogether. For example, tax-sup

ported colleges and universities have opened their doors

to Negro students in Texas, Oklahoma, Arkansas, Kansas,

Missouri, Louisiana, Kentucky, Tennessee, Virginia, North

Carolina, West Virginia, Maryland and Delaware. (Table

III(A) (1) :(b), Appendix, infra).

Despite the continued insistence of those who urge

the continuance of segregation on the ground that the

country is “ not ready,” these changes have not been lim

ited to public colleges which alone would be compelled by

the enforcement of the Fourteenth Amendment to open

their doors. Non-public institutions have been far in the

lead in the process of integration. Schools and colleges,

both private and parochial, have removed racial barriers

to admission in Alabama, Texas, Georgia, Missouri, Louisi

ana, Kentucky, Maryland, North Carolina, Virginia, West

Virginia, and as mentioned, the District of Columbia.

(Table III (A) (2), Appendix, infra). This merits special

9

attention, for if segregation were as embedded in the

“ usages, customs and traditions” of the South as it is

alleged to be, none of these institutions would have de

parted therefrom without compulsion. But freed of gov

ernmental compulsion to segregate (or exclude) by the

aftermath of this Court’s decisions in the Sweatt and Mc-

Lcmrin cases which substantially destroyed segregation in

public colleges, these non-public schools have dropped the

color bars in numbers and with a speed and fervor5 which

make it plain that it was only the barrier of the South’s

government-required segregation which had earlier stood in

their way—and not the South’s “ usages, customs and

traditions. ’ ’

In addition to the colleges and universities in which seg

regation has been abandoned, public elementary and high

schools have successfully ended segregation in recent years

in one or more communities in California, Arizona, New

Mexico, Kansas, Illinois, Ohio, Indiana, Maryland, Dela

ware, Pennsylvania and New Jersey. Public schools sup

ported entirely by Federal funds have been integrated at

Fort Bragg and Camp Lejeune, North Carolina, Quantico,

Virginia, Fort Knox, Kentucky and other southern military

reservations.

The District of Columbia has been no laggard in this

pattern of change. Only where law is interpreted to forbid

departure from segregation (as the D. C. Board of Educa

tion maintains is true here) has there been no correspond

ing progress. Private schools, at all levels of study, have

dropped the color bar. This is true of pre-nursery, nursery,

elementary and high schools, as well as colleges and grad

uate schools. (Table II, Appendix, infra).

5 The reactions of white students have been extremely favorable.

They have welcomed the newly arrived Negroes with group demon

strations of approval, have called for change at colleges refusing

admission to Negroes, have written articles for the press, and have

called on the President of the United States for assistance to end

racial restrictions. Table IV (B) Appendix, infra.

10

Moreover, neither in the District nor in other places

which have known segregation are these changes occurring

only in schools. We have compiled in Table IV a wide

variety of instances (which is only a sampling of thousands

of similar cases) in which places of public accommodation,

voluntary associations, religious bodies, employers, and the

athletic and entertainment world have followed where en

lightened public thinking has beckoned.

These developments have significance for our problem

because everywhere one looks—in colleges and universities,

in factories, in state legislatures and city councils, in

theaters, in stadia, in restaurants, in swimming pools, and

throughout our Armed Forces—there has developed an in

creasing and cumulative mingling of people of different

racial origins on a scale which makes ludicrous the con

tinued separation of children in their formative years at

school. Those who ride, play, and work, who fight and die

together without strife may—nay, do—study together with

out strife.

This, wide-ranging experience with integration, it should

be added, is a judicial, not a legislative, consideration for

it provides conclusive practical confirmation of the propo

sitions that (1) separation based on race has no rational

basis in our society and (2) integration presents nothing

remotely like war-time “ dire emergency and peril” which

alone might justify separation (Korematsu v. United

States, supra, p. 220), but in fact proceeds peacefully.

2. T h e p r o p h e s ie d c o m m u n it y r e s is t a n c e : to c h a n g e .

Departures from segregation have been successful to a

degree that surpasses even the most optimistic expectations

of the proponents of such change. They continually refute

the forecasts of those who on each and every such occasion

predict violence, resistance, difficulties and, at very least,

common dissatisfaction with the change.

If these predictions were made by those who previously

had urged the removal of barriers toward equality they

11

might be listened to with good grace. But though the words

are different the voice is the same. These are the last-

ditch arguments of those who would still preserve some

thing of their ancestors’ 19th Century class superiority,

with its intolerable burdens on other human beings, while

they also enjoy all the benefits of 20th Century society.

Furthermore, the mere assertion of such factors as

worthy of consideration by this Court necessarily implies

a belief that even if the Constitutional rights of an indi

vidual—or thousands of individuals—are being violated

justice shall be rendered them only if those who withhold

those rights will consent. Such a belief our democracy

rejects.

And this aside, these assertions are unsound judged even

by empirical standards rather than moral principle.

In Sweatt v. Painter, supra (October Term, 1949, No.

44), the appellees ‘warned that “ forced mixed schools”

would “ cause large withdrawals from the public schools”

(Appellees’ Brief, p. 175). The brief amicus filed by the

Attorneys General of eleven states was even more direful

(at p. 9), citing reports of impending disturbance at East

St. Louis and Alton, Illinois, two southern Illinois cities

where the schools were being desegregated under force by

law, and of apparent trouble at desegregated swimming

pools in Washington, D. C., and St. Louis, Missouri6:

6 The swimming pool incidents referred to by the Attorneys

General refute rather than support their argument. In Washing

ton, the disturbance was an isolated incident which has been fol

lowed since 1950 by operation of pools under jurisdiction of the

Interior Department without segregation and without the slightest

difficulty. Comment, 18 Univ. Chi. L. Rev. 769, 773-775 (1951).

And the attendance has shown a continuing increase. (Table IV,

item (8) Appendix, infra.) The St. Louis experience was even more

revealing. There the city officials reacted to an outbreak of violence

by reversing their previously adopted decision to end segregation. A

law suit was commenced to prevent segregation. Id. at 771-772.

United States District Judge Hulen firmly rejected the argument

that segregation should be retained to prevent disorder. Calling

this “ a new and novel theory” , he ruled that “ The law permits of

no such delay in the protection of plaintiffs ’ constitutional rights ’ ’.

12

The Southern States trust that this Court will not

strike clown their power to keep peace, order, and sup

port of the public schools by maintaining equal sepa

rate facilities. If the States are shorn of this police

power and physical conflict takes place, as in the St.

Louis and Washington swimming pools, the States are

left with no alternative but to close their schools for

that reason.

Of course, no “ physical conflict” took place because of the

decision which the Attorneys General feared. Instead, in

less than two years the number of Negroes who have been

peacefully integrated into Southern graduate and profes

sional schools exceeds well over a thousand, and the tabu

lation is no longer a matter of much interest since the point

is proved beyond debate.

In the Henderson case, infra (October Term, 1949, No.

25), the brief amicus filed by Rep. Sam Hobbs warned flatly

that “ that to adopt the contention of Appellant would be

the kiss of death to render operation of the railroad impos

sible” (p. 5). In Morgans. Virginia, 328 IT. S. 373 (1946)

(October Term, 1945, No. 704), the Commonwealth of Vir

ginia, Appellee, warned that the statute which the Court

subsequently invalidated was necessary to prevent violent

altercations which would cause drivers to lose control of

their busses (Appellee’s brief, p. 14). The effects of a re

versal of the decision below were painted in lurid terms

(Id. at pp. 18-20).

Again, no such evils resulted. In fact, the Court of Ap

peals for the Fourth Circuit has had occasion to point out

that no disorders occurred on the cars of a Virginia rail

road which recently abandoned segregation to the extent it

Draper v. St. Louis, 92 F. Supp. 546, 549 (B.D. Mo., 1950). The

following year, 1951, the pools were opened on a fully integrated

basis. “ Civil Rights in the United States in 1951” , page 90. As

indicated in the Appendix, both East St. Louis and Alton are

examples of successful integration, rather than disturbance of any

sort.

13

found convenient. Chance v. Lambeth, 186 F. 2d 879, 881,

882-883 (C.A. 4th, 1951).

We are not so naive as to discount the possibility of some

forms of resistance to a decision that racial segregation in

public grade schools is unconstitutional. But the prophecy

of violence has so often been shown to be without sub

stance 7 that it is now made with little conviction. Of

course, this Court conclusively answered what has been

called the “ rhetoric of violence”8 when it squarely held

that the preservation of the public peace cannot be ac

complished by laws which violate the Constitution. Bu

chanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60, 81 (1917).

It goes without saying* that to deny a constitutional right

because the lawless element of a community dislikes its

enforcement is to suggest that the Federal compact is no

match for the lynch-law mob.

Recognition of these facts by those who still seek to up

hold segregation leads to their more sophisticated sugges

tion that the abolition of segregation at this time will (a)

destroy public education in the South or (b) destroy the

liberal or progressive movement in the South. The fact is

that public education will no more be threatened by the

Court’s action against segregation in these cases than it

was by its action in the cases of Sweatt v. Painter, supra;

McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents, supra, and Hender

son v. United States, 339 U. S. 816. At best such argu

ments in effect only urge delay in the disposition of the

constitutional question. But delay is more likely to aggra

vate than to solve these alleged problems.9 Moreover,

7 Note, 61 Yale L. J. 730, 738-743 (1952); Lewis, The Crisis

That Never Came Off, The Reporter, 1:12 (Dec. 6, 1949).

8 Comment, 18 Univ. Chi. L. Rev. 769, 781 (1951).

9 In the meantime the denial of constitutional rights is itself

productive of disorder. As a Georgia court noted long ago, “ in

the end, if those laws are unfair, unjust, unequal, they will

breed discontent and disorder, and it is better for the peace and

good order of society that all shall have equal rights,” White

v. Clements, 39 Ga. 232, 269 (1869).

14

these arguments were not first urged upon this Court when

the Sweatt and Henderson cases were argued; they were

put forth over 75 years ago (Of. 2 Cong. Eecord 4153

(1874); 3 Cong. Record 981-982, 997, 1002 (1875)).

Nor are these alleged problems peculiar to the South.

The quality of individual prejudice is not governed solely

by the residence of the individual. Integration proposals

have brought prophecies of violent resistance in northern

waterfront towns like Camden, N. J., no less than in Clar

endon County, S. C., and of destruction of public education

in Alton, Illinois no less than in Atlanta, Georgia. But

Camden saw no violence and is fully integrated, and Alton,

rather than give up the State’s monetary contribution to

its public schools, gave up segregation. This was done

grudgingly, but it was done—peacefully and completely.

We submit that if there is to be resistance, it

will take the form not of destruction but of evasion. And

the patterns of evasion are by this time familiar. Although

the practice of excluding Negroes from the Democratic

Party primary in the South was first condemned in 1927

(Nixon v. Herndon, 273 U. S. 536) this Court was called on

several times thereafter to consider the validity of at

tempted evasions of that decision.10 Even after the last de

cision there were further attempts—continuing to the pres

ent day11—which were dealt with by the lower courts.12

10 Nixon v. Condon, 286 U. S. 73 (1932); Grovy v. Townsend,

295 U. S. 45 (1935) ; Smith v. Allwright, 321 U. S. 649 (1944)'-

Schnell v. Davis, 336 U. S. 933 (1949).

11 Terry v. Adams, 193 F. 2d 600 (C.A. 5th, 1952), cert, granted

Nov. 12, 1952.

12 Chapman v. King, 154 F. 2d 460 (C.A. 5th, 1946), cert, de

nied, 327 IT. S. 800; Mitchell v. Wright, 154 F. 2d 924 (C.A. 5th,

1946), cert, denied, 329 IT. S. 733; Bice v. Elmore, 165 F. 2d 387

(C.A. 4th, 1947), cert, denied, 333 U. S. 975; Baskin v. Brown,

174 F. 2d 391 (C.A. 4th, 1949); Perry v. Cyphers, 186 F. 2d 608

(C.A. 5th, 1951) ; Adams v. Terry, 193 F. 2d 600 (C.A. 5th, 1952) ;

Davis v. Schnell, 81 F. Supp. 872 (D.C. S.D. Ala., 1949), aff’d

without opinion, 336 U.S. 933 (1949) ; Dean v. Thomas, 93 F.

Supp. 129 (D.C. B.D., L., 1950).

15

Ultimately the fight will be completely abandoned. Negroes

are now voting in constantly increasing numbers in the

Democratic primary and general elections in the South, and

candidates make special efforts to win their support;.13

And so, while we may expect gerrymandering and possi

bly so-called “ private” corporations operating the schools

for one or a few of the States, we freely predict that in this

day and age there will be neither real abandonment nor ed

ucational deterioration of the public school system in the

areas involved. Furthermore, in the District of Columbia

community acceptance and respect for legal authority is

obviously such that there can be no fear whatever that this

Court’s order will be resisted here. As Judge Edgerton

said in his dissent in Carr v. Corning, 182 F. 2d 14, 33:

“ When United States courts order integration of District

of Columbia schools they will he integrated” . (Emphasis

supplied.).*

We know, too, that despite the urging of the prophets of

doom this Court will not permit basic Constitutional rights

to be reduced by the lowest pessimistic denominator.

13 Race and Suffrage in the South since 1940, Jackson, Luther P.,

New South, Vol. 3, pp. 1-26 (1948); Civil Rights in the United

States in 1951, op. cit. supra, p. 18; A Decade in Race Relations,

Wilkins, Roy, America, June 16, 1951, pp. 287-289; Stakes Are

Costly in Play for Texas, N. Y. Times, Sept. 23, 1952.

* Only last week the Superintendent of Schools said the school

system would not be unprepared for a decision ending segrega

tion, Washington Post, Nov. 29, 1952. By contrast, we regard as

particularly unfortunate the Court’s statement in the Carr case,

supra, p. 16, that the problems with which it was dealing were

1 ‘ insoluble by force of any sort. ’ ’ The same amount of ‘ ‘ force ’ ’ is

exercised by segregated as by unsegregated schools. The present

practices in the District of Columbia school system are just as

“ forceful” to those who desire to associate with their fellows with

out artificial racial barriers as an unsegregated system would be

to those who wish to keep aloof.

16

B. Declared legislative prohibitions against segregation in

other areas of activ ity in the District of Columbia demon

strate the further irrationality of school segregation.

The classification of groups of children in the public

schools by skin color alone must also be tested in the light

of legislative action affecting other group relationships in

the community.

As early as 1865,14 the Congress expressly forbade any

street railway company in the District of Columbia to ex

clude any person from any car, and since then there

has been no “ Jim-Crow” transportation in the District. In

1872 and 1873, the Legislative Assembly for the District

enacted laws (referred to as the “ Equal Service Laws” )

forbidding the refusal to serve any well-behaved person in

any eating place, barber shop or hotel.15 Thereafter, in

1875, the Congress enacted the famed Civil Eights Act,18

forbidding racial discrimination or exclusion in places of

public accommodation throughout the country, including

the District of Columbia.

This series of legislative measures, then, carved out vast

areas for the free association of peoples in the District.

As opposed to the direct prohibitions against segregation

in these instances where Congress has clearly expressed its

intention on the subject, no instance has been found where

the Congress requires segregation. (It should be noted

that the statutes relied upon here as establishing a segre

gated school system are not mandatory in form—unlike

school and other statutes in the South which explicitly re-

14 Section 5 of the Act of March 3, 1865, 13 Stat. 536.

15 The law of 1873 was recently held valid, and in force, in Dis

trict of Columbia v. John B. Thompson Co., 81 A. (2d) 249 (D.C.

Mun. App.). An appeal is now pending in the United States Court

of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit.

18 Act of March 1, 1875, 18 Stat. 835. This Act was declared

invalid as applied to the States (Civil Bights Cases, 109 IT. S. 3

(1883)) and, only because the provisions were considered nonsep-

arable, to steamships in coastwise trade {Butts v. Merchants and

Miners Trams. Co., 230 U. S. 126 (1913).

17

quire segregation. See compilation in the Appendix to the

Petitioners’ brief, herein.)

In this context, particularly in view of the other broad

areas of present free community association mentioned in

Section A, supra, it becomes impossible to accept as having

rational foundation a legislative classification singling pub

lic school children alone out of the entire community for

governmental separation based solely on race.

C. Present scientific understanding discredits traditional

concepts of "race".

Governmental classifications must also be tested in the

light of present-day scientific understanding.

It seems hardly necessary at this late date to offer proof

that conduct governed by assumed distinctions attributed

to race is wholly arbitrary. Moreover, the concept of

“ race”, which has been thought to have a scientific expla

nation based on esoteric classifications used by physical

anthropologists, have been demonstrated by mature stu

dents of anthropology to be largely lacking even such a

foundation, and they have shown that no significance what

ever can be attached to skin color alone. Boyd, Genetics

and the Races of Man (Little, Brown & Co., 1950), pp. 10-

27, 184-207.17

Certainly in the Western World no nation is anything

but a mixture of many kinds of racial groups. The term

17 ‘ ‘ The biological fact of race and the myth of ‘ race ’ should be

distinguished. For all practical social purposes ‘race’ is not so

much a biological phenomenon as a social myth. The myth of

‘race’ has created an enormous amount of human and social dam

age. * * * I t still prevents the normal development of millions of

human beings and deprives civilization of the effective co-opera

tion of productive minds. The biological differences between ethnic

groups should be disregarded from the standpoint of social ac

ceptance and social action.” Statement by Experts on Race

Problems, United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural

Organization, .July 18, 1950. See also LaFarge, The Race Question

and the Negro; Itedfield, What We Do Know About Race, 57

Scientific Monthly 193 (Sept., 1943) ; Krogman, An Anthropologist

Looks at Race, 7 Intercultural Education News 1 (Nov., 1945).

18

“ white” is racially meaningless as applied to almost all

American or European whites. There are fair-haired, tall,

long-headed North Europeans and dark-haired, less tall,

round-headed South Europeans. And there are all those

who run the gamut. They are all race mixtures. Benedict

& Weltfish, Races of Mankind (Public Affairs Committee,

1944). Even more certain is it that the American Negro

is not a “ race” . Not only were the original African slaves

members of different “ racial” groups (from different

parts of Africa) but their cross-fertilization with “ white”

Americans has been extensive. As early as 1920 at least

15.9 per cent of the “ Negro” population was visibly mu

latto. Klineberg, Characteristics of the American Negro

(Harper, 1944), p. 268. And a recent study by John Hop

kins and Pittsburgh University professors discloses that

the Negro population in the United States is 30 per cent

white in its ancestry. Glass and Li, Report on the Dynamics

of Racial Intermixture, Annual Meeting of American In

stitute of Biological Sciences at Cornell University (N. Y.

Times, Sept. 8, 1952, 33:8); Comas, Racial Myths

(UNESCO, 1951) pp. 1-26.

II

THE FACT THAT CONGRESS MADE PROVISION FOR THE

ESTABLISHMENT OF SCHOOLS FOR NEGRO CHILDREN IN

THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA BEFORE THE ADOPTION OF

THE FOURTEENTH AMENDMENT DOES NOT JUSTIFY THE

CONCLUSION THAT THE FOURTEENTH AMENDMENT WAS

INTENDED TO PERM IT RACIAL SEGREGATION.

Petitioners urge in this case that racial segregation in

the schools operated by the District of Columbia govern

ment is discriminatory per se and consequently prohibited

by the Fifth Amendment. The argument rests on the firmly

based principle that “ distinctions between citizens solely

because of their ancestry are by their very nature odious to

a free people whose institutions are founded upon the doc

trine of equality” . Hirdbayashi v. United States, 320 U. S.

81, 100 (1943).

19

It is urged, however, by those seeking to uphold school

separation based on race alone that neither the Fifth nor

the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution, prohibits

segregation.173- In this connection, reliance is placed on cer

tain statutes enacted by the United States Congress for the

education of Negro children in the District of Columbia

at about the same time the Congress submitted the

Fourteenth Amendment to the states for ratification. The

theory suggested is that these statutes expressly provided

for the establishment of segregated schools for Negro and

white children and that, hence, the Congress of that period

could not have viewed the constitutional principles em

bodied in the Fourteenth Amendment as prohibiting racial

■segregation.

This argument was given much weight by the majority

opinion (Edgerton, J., dissenting) of the Court of Appeals

for the District of Columbia Circuit in Carr v. Corning, 182

F. 2d 14 (1950).18 Judge Prettyman’s opinion there re

viewed the statutes in question and concluded that they

“ conclusively support” the view that the Fourteenth

Amendment does not prohibit segregation. Ibid, pp. 17-19.

We have already indicated our contention that the rea

son or unreason of a classification such as separate racial

schools must be judged on the basis of contemporary con

ditions and current knowledge, and not governed by the

dead hand of the past. Weems v. United States, 217 U .8.

349, 373-374, 378 (1910). But because we wish to meet

squarely the argument from history, just outlined, we turn

now to an analysis of the past as it is involved therein.

17a Brief for Respondents herein, pp. 36-37; Brief for Appellees

in Briggs v. Elliott, No. 101 this term, p. 15; Brief for Appellees

in Davis v. County School Board, No. 191 this term, pp. 12-13.

18 The complaint in the Carr case, as in this one, challenged the

constitutionality of segregation in the District of Columbia public

schools. The Court of Appeals upheld segregation and no review

of its decision was sought in this Court. In the instant case, the

District Court in granting the motion to dismiss, stated in an oral

opinion that it was bound by the Carr decision.

20

Such analysis shows that the conclusion on the part of the

Court of Appeals in the Carr case was neither required

nor justified in the light of the genesis of the local laws

and of the Fourteenth Amendment. On the contrary, the

conclusion that the Fourteenth Amendment was intended

to prohibit segregation is fully documented in the pene

trating study by Flack in his The Adoption of the Four

teenth Amendment (1908), by the petitioner’s brief in

Sweatt v. Painter, supra (pp. 54-62), by the amicus brief

of the Committe of Law Teachers in that case (pp.

5-19), and by the latest and perhaps most exhaustive study

of all, Frank and Munro, The Original Understanding of

“Equal Protection of the Laws,” 50 Col. L. Rev. 131,153-62

(1940). We shall not repeat that presentation here.

This conclusion cannot be cavalierly swept aside simply

by finding in isolated statutes, narrow and localized in scope

and enacted years before the ratification of a constitutional

amendment over which the entire nation seethed, a purpose

completely at variance with the whole thrust of that amend

ment as it was generally understood.

In the Carr case, Judge Prettyman cited six statutes.

Only five of these are actually relevant.19 These five

statutes were enacted between 1862 and 1866—and the

dates are crucial, since the Court of Appeals inferred, from

the fact that they were (1) contemporaneous with the pas

sage by Congress of the proposed Fourteenth Amendment

and (2) seemingly inconsistent with an anti-segregation in-

19 The reference in the Carr decision (pp. 17-18) to Sections 281,

282, 294 and 304 of the revision of the D. C. Statutes (Act of June

22, 1874, 18 Stat. part 2) appears erroneously to assume that these

provisions were first enacted in that year. In fact, these are sec

tions taken from the Act of June 25, 1864, 13 Stat. 187, 191, from

which Judge Prettyman had already drawn significance, and no

additional significance can be found in their inclusion in the 1874

Revision, since that was merely part of a Congressional attempt

to provide up-to-date compilations of existing law—one such com

pilation for the District of Columbia, and another (U. S. Revised

Statutes, 1872 and 1878) of the general laws of the United States.

Certainly there is no suggestion that any consideration was given

by Congress in 1874 to the determination of racial policy which is

inherent in the inference drawn by Judge Prettyman.

21

terpretation of that Amendment, that the Amendment itself

could not have been intended to abolish segregation.

But the inference is by no means either necessary or cor

rect. It is based on a misconception of both the pertinency

of the chronology and the purposes of the school statutes.

When the Fourteenth Amendment was proposed in June

1866, its framers obviously had no means of knowing how-

many years would elapse before its ratification by the

states; in fact, it was not until July 1868, more than two

years later, that it was declared ratified. The mere fact

that the Amendment was proposed in 1866, at approxi

mately the same time as the 1866 statutes, does not, as Judge

Prettyman implies, necessarily impute to the Congress a

purpose in that Amendment to perpetuate segregated

schools.20 It may equally suggest a desire to deal with the

problem on a national basis rather than a local one, just as

the Congress later did, in the Civil Rights Act of 1875, when

it prohibited discrimination of any kind in places of public

accommodation anywhere in the United States, including

the District of Columbia.21 We recognize that Congress,

prior to the Fourteenth Amendment, was making provi

sion for schools which, when they were finally established,

were separate. But to conclude from this that Congress in

tended to perpetuate this situation, come what may, is to

fail to distinguish between mere recognition of the his

torical fact of segregation and a mandate for segregation.

In fact, what the historical development of public educa

tion for colored children does amply demonstrate is that

the Congress was concerned in the 1860’s with obtaining

education for those children, and further that Congress was

never faced with the issue of granting or denying a request

20 Moreover, it should be recognized that there is significance in

the fact that the path travelled through the Houses of Congress

by the Bill dealing with District schools was obviously different

from that taken by the Bill proposing the Fourteenth Amendment.

The origin, committee consideration, and debates were totally dif

ferent from the two matters.

21 Act of March 1, 1875, 18 Stat. 335.

22

that there should be “ integrated” education. At that time

public education of any kind was still regarded in many

quarters as invidious, and education for the Negro (who in

many states was still forbidden to learn to read or write)

had only a short while prior thereto been deemed wholly

objectionable by some legislators.22

In 1862, only a few weeks after slaves were freed in the

District of Columbia23 (and almost a year before the

Emancipation Proclamation of January 1, 1863) the Con

gressional action was an attempt for the first time to pro

vide “ free”24 public education for colored children. The

Congress w'as concerned with that problem alone.

Similarly, in 1864,25 when Congress provided that the

amount used to support schools for colored children should

be appropriated from the general revenues of the cities of

Washington and Georgetown in accordance with the ratio

of colored children to the total number of children, Con

gress was faced only with the problem whether (in view

of the exceedingly small sums allotted by the authorities

to the colored 'schools)28 they should continue to tax colored

persons separately to support schools for colored chil

dren.27

22 Of. 62 Cong. Globe, 37th Cong., 3d Sess. 1326-1327 (1863).

23 Act of April 16, 1862, 12 Stat. 376.

24 Act of May 20, 1862, 12 Stat. 394; Act of May 21, 1862, 12

Stat. 407. In part, the purpose was to remedy the unjust dis

crimination of the existing D. C. school system which, as a result

of slavery days, denied admittance to colored children while col

lecting taxes from their parents, forcing the latter to maintain

their own schools. Bryan, History of the National Capital, Yol.

II, (1916), pp. 137-38/389, 524-528.

25 Act of June 25, 1864, 13 Stat. 187, 191.

26 In 1862 nothing was paid over by Georgetown and only

$8,256.25 by Washington. In 1863, Georgetown paid $69.72 and

Washington $410.89. The need for additional funds was obvious.

Special Report of the Commissioner of Education on the Condi

tion and Improvement of Public Schools in the District of Colum

bia, p. 253, H. Eep. Ex. Doc. No. 315, 41st Cong., 2d Sess. (1871).

27 The earlier Act of May 21, 1862, supra, n. 24, required the use

of 10 percent of the taxes levied upon property of colored persons

for the support of such schools.

23

So, too, when in 186628 Congress expressly ordered that

the Act of 1864 he construed so as to require the cities of

Washington and Georgetown to pay over the appropriated

sums to the trustees of colored schools, Congress had not

been requested to “ integrate” but was acting only to over

come the continued reluctance of the municipal authorities

to make any but the most completely inadequate provision

for the education of colored children. And further, when

the following week29 the Congress authorized the convey

ance of certain lands of the United States to the trustees of

colored schools it was again seeking to provide education

for colored children; it was not determining a question of

racial policy. Since at that very time Congress was debating

the question whether segregation would be outlawed by the

proposed Amendment,30 it may be supposed that Congress

would have been astonished to be told that it was else

where determining that very question—and by means of a

localized statute, not a Constitutional Amendment of na

tion-wide scope and interest.

In sum, the whole point is that the major portion of the

period under analysis was prior to and not contemporane

ous with the Fourteenth Amendment and (as the Cor

poration Counsel has argued in another context)31 “ the

laws setting up schools for colored were enacted at a time

when members of that race were afforded no schooling

whatsoever. The purpose of the laws was to give rather

than to take away, was to afford opportunity rather than

deny opportunity * *

Additional evidence of historical misconstruction in the

Carr opinion is found in the fact that, contemporaneously

with the adoption of the Fourteenth Amendment by the

Congress, there was also enacted the bitterly fought over

28 Act of July 23, 1866, 14 Stat. 216.

29 Act of July 28, 1866, 14 Stat. 343.

30 Flack, Adoption of the Fourteenth Amendment (1908), pp.

77-82.

31 Brief for Appellees in Cogdell v. Sharpe, No. 11,019, in U. S.

Court of Appeals for District of Columbia Circuit, October Term,

1951, p. 58.

24

Civil Eights Bill of 1866.32 So significant was that Bill that

the Amendment was ‘ ‘ sidetracked to give full sway to that

important measure.” 33 This bill was generally understood

to have the effect of opening white schools to Negroes.34

But this very fact was believed to raise substantial doubts

as to its validity on the ground that it was an exercise of the

powers of the States. Accordingly, the first section of the

Fourteenth Amendment was designed to meet this alleged

Constitutional infirmity and to make secure the provisions

of the Civil Rights Bill.36

Following the ratification of the Amendment, the Bill

was re-enacted36 and has been enforced by this Court as

recently as 1948, in Hurd v. Hodge, 334 U. S. 24.37

Thus it is plain that the conclusion reached in the Carr

case not only ignores the time sequence of the statutes and

the ratification of the Amendment, but also gives a com

pletely distorted significance to the school legislation.

CONCLUSION

The advances commenced by the Civil War were

slowed and almost halted by judicial gloss on the Four

teenth Amendment. We trust that it is worth reminding

the Court that segregation is not a Constitutional com

mand. It was nothing more than a de facto social phenom

enon until this Court itself gave it legal and Constitutional

dignity by its majority decision in Plessy v. Ferguson. By

32 Act of April 9, 1866, 14 Stat. 27 (passed over veto). This is

not the Act invalidated in the Civil Rights Cases.

33 Flack, op. cit., supra, p. 20.

34 Ibid, pp. 40-54; Frank and Munro, op. cit., supra, p. 160.

35 Ibid, p. 55.

36 Act of May 31, 1870, 16 Stat. 140.

37 The respondents argue that the failure to include schools

within the coverage of the Civil Rights Act of 1875 indicates Con

gressional intent to permit segregation. (Br. p. 37) The

answer to this is two-fold: (1) It was not that Congress which pro-

prosed the Fourteenth Amendment; and (2) the omission of schools

was a purely political and practical matter, not negating the un

derstanding that the Amendment (though obviously not self-exe-

euting) did prohibit separate schools. Brief of the Committee of

Law Teachers, op. cit., supra, pp. 14-16; Frank and Munro, op.

cit., supra, pp. 156-162.

25

now it has become clear that “ separate” in practice is

never “ equal” , and it now needs only this Court's deter

mination to strip from segregation its spurious dignity, by

holding with Mr. Justice Harlan that “ Our Constitution

is color-blind.”

Respectfully submitted,

A m e r ic a n C o u n c il , o n H u m a n R ig h t s

By: Aubrey E. Robinson, Jr.

A m e r ic a n s fo r D em o c r a t ic A c t io n (Washington Chapter)

By: Theodore C. Sorensen

A m e r ic a n J e w is h C o m m it t e e (Washington Chapter)

By: William C. Koplovits

A m e r ic a n J e w is h C o n g r ess , C o m m is s io n o n L a w & S o c ia l

A c t io n (Washington Chapter)

By: S. Walter Shine

C a t h o l ic I n t e r r a c ia l C o u n c il o f W a s h in g t o n

By: John J. O’Connor

C o m m is s io n o n C o m m u n it y L if e o f t h e W a s h in g t o n F e d

e r a t io n o f C h u r c h e s

By: L. Maynard Catching s

D is t r ic t of C o l u m b ia I n d u s t r ia l U n io n C o u n c il , C .L O .

By: Ben Segal

D. C. F e d e r a t io n o f C iv ic A s so c ia t io n s , I n c .

By: John B. Duncan

F r ie n d s C o m m it t e e o n N a t io n a l L e g is l a t io n

By: E. Raymond Wilson

J a p a n e s e A m e r ic a n C it iz e n s L ea g u e

(Washington Chapter)

By: RiMo Kumagai

J e w is h C o m m u n it y C o u n c il o f G r e a t e r W a s h in g t o n

By: Isaac Franck

N a t io n a l A s so c ia t io n f o r t h e A d v a n c e m e n t of C olored

P e o p l e (D. C . Branch)

By: Constance E. II. Daniel

U n it a r ia n F e l l o w s h ip fo r S o c ia l J u s t ic e

(Washington Chapter)

By: Margery T. Ware

26

W a s h in g t o n B a r A s so c ia t io n

By: Joel D. Blackwell

W a s h in g t o n E t h ic a l S o c ie t y

By: Milton Chase

W a s h in g t o n F e l l o w s h ip

By: Edwin B. Henderson

W a s h in g t o n I n t e r r a c ia l W o r k s h o p

By: Lillian Palenius

W a s h in g t o n TJr b a n L e a g u e

B y : L. K. Shivery

S . W a l t e r S h i n e

T h eo d o r e 0 . S o r e n s o n

S a n eo rd H. B o lz

S a m u e l B . ( I r o n h r

Counsel

December, 1952.

APPENDIX

The information in the following tables is culled from the files

and resources of the organizations sponsoring this brief. I t is

intended to be only representative, not exhaustive, and it is believed

to be accurate.

27

TABLE I

List of Cities in Southern and Border Slates in Which Some

Schools, Colleges and Universities Have Been Recently Inte

grated.

Alabama

Talladega

Arizona

Douglas

Duncan

Globe

Miami

Prescott

Tolleson

Tucson

Arkansas

Fayetteville

Little Rock

Pine Bluff

California

Contra Costa

County

Imperial Valley

Santa Ana County

Mendota

D istrict of

Columbia

Delaware

Claymont

Hockessin

Newark

Georgia

Decatur

I llinois

Alton

Argo

Cairo

East St. Louis

Edwardsville

Harrisburg

Madison

Metropolis

Illinois (continued)

Sparta

Tamms

Ullin

Waukegan

I ndiana

Elkhart

Gary

Indianapolis

New Albany

South Bend

K ansas

Topeka

Lawrence

Kentucky

Berea

Fort Knox

Lexington

Louisville

Nazareth

Paducah

Louisiana

Baton Rouge

New Orleans

Maryland

Annapolis

Baltimore

College Park

W estminster

Missouri

Columbia

Kansas City

St. Louis

New Mexico

Alamogordo

Albuquerque

Carlsbad

Santa Fe

North Carolina

Asheville

Camp Lejeune

Chapel Hill

Fort Bragg

Ohio

Allendale

Cincinnati

Glendale

Wilmington

Oklahoma

Norman

Stillwater

South Carolina

Greenville

Tennessee

Knoxville

Mont Eagle

Texas

Amarillo

Austin

Big Spring

Corpus Christi

Dallas

Fort Worth

Houston

Plainview

Wichita Falls

Virginia

Alexandria

Charlottesville

Fort Quantico

Richmond

Williamsburg

West V irginia

Buckhannon

Morgantown

28

TABLE II

Schools, Colleges and Universities in the District of Colum

bia and Environs Which Will Accept Both White and Negro

Students.

A. Nursery, E lementary and H igh Schools:

All Catholic parochial, schools

Arlington Unitarian Church Summer School

Baker’s Dozen Youth Center

Beauvoir Elementary School (1953)

Bethesda-Chevy Chase Nursery School

Burgundy Farms Country Day School

Community Nursery School

Georgetown Day School

Green Acres Day School

Hisacres New Thought Center Nursery School

Kenilworth School (Mother’s Club, Nursery)

Lincoln Congregational Church Nursery School

Raymond School (Mother’s Club, Nursery)

Rosedale School (Mother’s Club, Nursery)

Silver Spring Nursery School

B. Colleges and Universities :

American University

Catholic University

Dunbarton College of Holy Cross

Georgetown University (all but Foreign Service School)

Howard University

National Law School

Trinity College

29

TABLE III

"The School Doors Open Wide"

Examples of Recent Admission of Negroes to Educational

Institutions in the South and Border Areas

A. In the South

1. PUBLIC EDUCATION

a. E lementary and H igh School Level

Delaware

Claymont—Negroes attend Claymont public school previously

restricted to whites, for first time, under court order.1

Hockessin—Negroes admitted to Hoekessin white public school,

as ordered by state court.2

Kentucky

Fort Knox—Base public school, supported entirely by Federal

funds, admits both Negro and white students on equal

basis.

Maryland

Baltimore—Negro boys admitted to Baltimore’s Polytechnic

Institute (High School) although municipal ordi

nance bars admission.8

North, Carolina

Camp Lejeune—Public school at Camp Lejeune, supported en

tirely by Federal funds, has successfully integrated

its white and Negro students.

Fort Bragg—Integrated public school at Fort Bragg, operated

entirely with Federal funds, operated without fan

fare or incident since September, 1951. Only one pa

rental complaint, about Negro students, and teacher,

soon ended.4

Virginia

Fort Quantico—Public school at Fort Quantieo operates with

out segregation.

b. College and Graduate Level

Arkansas

Fayetteville—Several hundred Negro students have received a

friendly acceptance for nearly 4 years in graduate

and professional schools of University of Arkansas.5

Little Rock—Negroes accepted without incident in law, educa

tion, and medical graduate schools of University of

Arkansas, despite one local objection.6

30

Delaware

Newark—University of Delaware at Newark admits qualified

Negroes to any course which is not provided at Dela

ware State College for Negroes.7

Kentucky

Louisville—Louisville Municipal University and Negro College

completely and successfully integrated at graduate

and undergraduate levels, in classes, dormitories,

cafeteria, and all student activities. “ A magnificent

success,” says Pres. Davidson.8

Lexington—University of Kentucky has successfully opened

up graduate and professional schools to several hun

dred Negro students, who face no segregation in such

places as the cafeteria.9

Paducah—Under court order, a Negro applicant has been ac

cepted at Paducah Junior College.10

Louisiana

Baton Rouge—Negro student accepted without incident at

Louisiana State University.11

New Orleans—Louisiana State University graduate college is.

open to Negro students.

Maryland

Annapolis—Negro graduates from U. S. Naval Academy at

Annapolis.12

College Park—University of Maryland admits qualified

Negroes to graduate and undergraduate schools.

(Negroes have been admitted to the law school since

1935.) Integration (including admission to dormi

tory life) has been wholly successful.13

Missouri

Columbia—Negroes are being admitted to the University of

Missouri after favorable action by students, adminis

trators, and others, and without incident.14

St. Louis—Harris Teachers College, a municipal institution,

admitted its first Negro under court order.15

North Carolina

Chapel Hill—Several Negroes attend University of North Car

olina law school, as 2 graduates pass state bar exam

ination. Other graduate schools also opened without

incident.16

Oklahoma

Norman—Negro students have attended, and graduated from,

various divisions of the University of Oklahoma since

1948, with no trouble of any kind.17

Stillwater—Negroes admitted to Oklahoma A. & M., join white

students in athletic and other similar activities, with

out difficulty.18

31

Tennessee

Knoxville—Negroes have been admitted to some of the grad

uate and professional schools of the University of

Kentucky, without difficulty.19

Texas

Amarillo—Amarillo Junior College now admits Negro

students.

Austin—Negroes enrolled successfully, despite widespread pro

test, in September 1950, at University of Texas.21

Texas University admits first two Negroes to Dental

Scbool.21a

Corpus Christi—Del Mar Municipal Junior College has opened

its doors to qualified Negro residents of Corpus

Christi.22

Big Spring—Howard Junior College, previously all white, has

opened its doors to Negro students.23

Wichita Falls—Midwestern University ordered by Federal

Court to admit colored students.24

Virginia

Charlottesville—Negroes admitted without incident to Univer

sity of Virginia for first time in 1950.25

West Virginia

Morgantown—Negro students have been accepted into the Uni

versity of West Virginia graduate, and more recently