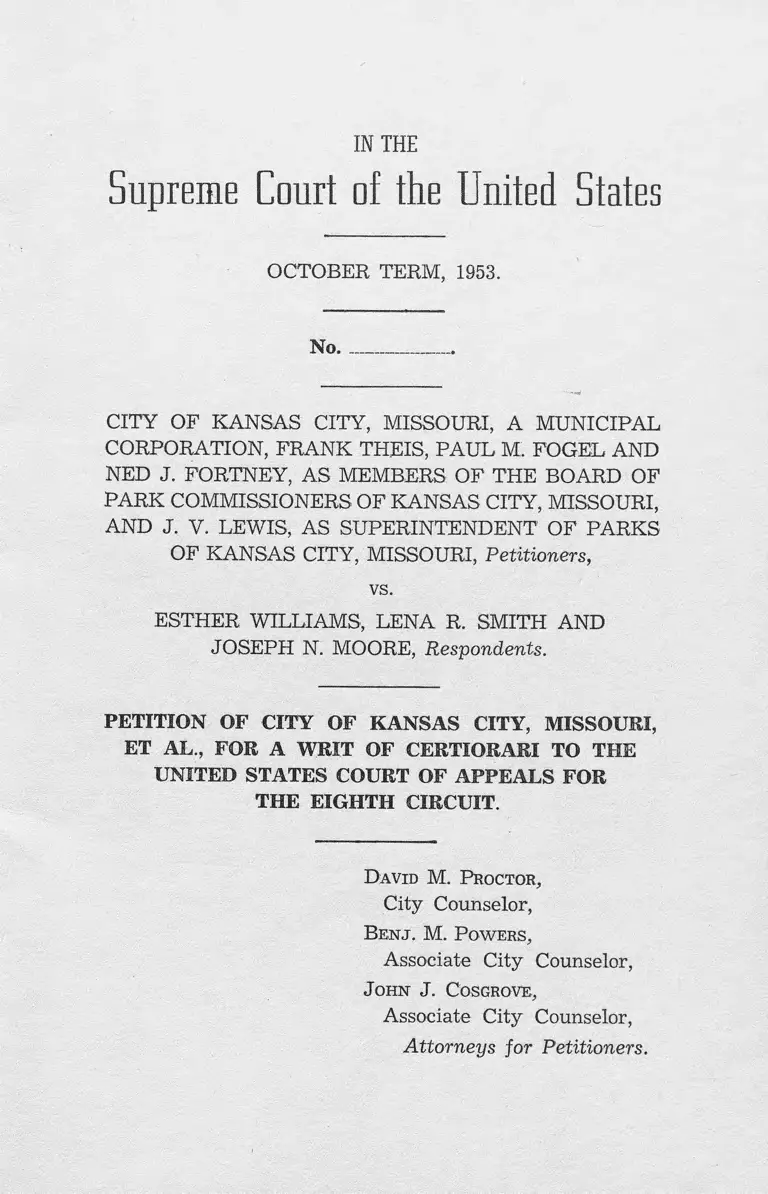

City of Kansas City, Missouri v. WIlliams Petition for Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

October 5, 1953

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. City of Kansas City, Missouri v. WIlliams Petition for Writ of Certiorari, 1953. 4dedf596-b99a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/6e511443-f1c2-4d2d-a87a-0bd01821e6a1/city-of-kansas-city-missouri-v-williams-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

IN THE

Supreme Court of the United States

OCTOBER TERM, 1953.

No.

CITY OF KANSAS CITY, MISSOURI, A MUNICIPAL

CORPORATION, FRANK THEIS, PAUL M. FOGEL AND

NED J. FORTNEY, AS MEMBERS OF THE BOARD OF

PARK COMMISSIONERS OF KANSAS CITY, MISSOURI,

AND J. V. LEWIS, AS SUPERINTENDENT OF PARKS

OF KANSAS CITY, MISSOURI, Petitioners,

vs.

ESTHER WILLIAMS, LENA R. SMITH AND

JO SEPH N. MOORE, Respondents.

PETITION OF CITY OF KANSAS CITY, MISSOURI,

ET AL., FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR

THE EIGHTH CIRCUIT.

David M. Proctor,

City Counselor,

Be n j. M. P owers,

Associate City Counselor,

J ohn J. Cosgrove,

Associate City Counselor,

Attorneys for Petitioners.

INDEX

Opinions Below ___________________________________ 2

Opinion of the D istrict Court of the W estern Divi

sion of the W estern D istrict of M issouri Is Re

ported in 104 Fed. Supp. 848 (R. 24) __________ 2

Jurisdiction _________________________________ 3

Questions Presented _______________________________ 3

Statutes Involved _________________________________ 4

Pleadings and C ourt’s O p in ion______________________ 4

Statem ent of Facts ________________________________ 6

Specifications of E rro r ____________________________ 11

Reasons Relied Upon for the G ranting of the W rit—

I. The Application of the Fourteenth A m endm ent

to Segregation in the Use of Swimming Pools

Has Never Been D eterm ined by This C o u r t___ 12

II. The Court of Appeals Erred in Relying on Mc-

Laurin vs. Oklahoma As A uthority for A ffirm

ing the Judgm ent and Decree of the D istrict

Court ______________________________________ 12

III. The Court of Appeals E rred in Failing to Make

a Full and Detailed Comparison Between the

Swope Park Swimming Pool Facilities Reserved

for W hites Exclusively and the Parade Park

Swimming Pool Facilities Reserved for Negroes

Exclusively _________________________________ 13

IV. The Court of Appeals E rred in Classifying P ub

lic Recreational Facilities Such As Golf, Picnic

Ovens, Boating on a Lagoon and S tarlight

Theatre, in the Same Category w ith a Public

Swimming Pool F ac ility ______________________ 14

II Index

V.. The Court of Appeals E rred in Failing to Reverse

the Judgm ent and Decree of the D istrict Court

and in Not Holding That the Facts, As a M atter

of Law, Showed T hat the Swimming Pool Facil

ities Furnished Negroes W ere Substantially

Equal to Those Furnished W hite Persons ____ 15

C onclusion__________________________________ _____ 16

IN THE

Supreme Court of the United States

1.4 OCTOBER TERM, 1953.

No. ...

CITY OF KANSAS CITY, MISSOURI, A MUNICIPAL

CORPORATION, FRANK THEIS, PAUL M. FOGEL AND

NED J. FORTNEY, AS MEMBERS OF THE BOARD OF

PARK COMMISSIONERS OF KANSAS CITY, MISSOURI,

AND J. V. LEWIS, AS SUPERINTENDENT OF PARKS

OF KANSAS CITY, MISSOURI, Petitioners,

vs.

ESTHER WILLIAMS, LENA R. SMITH AND

JO SEPH N. MOORE, Respondents.

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR

THE EIGHTH CIRCUIT.

K ansas City, Missouri, a municipal corporation, and

Frank Theis, Paul M. Fogel and Ned J. Fortney, as m em

bers of the Board of P ark Commissioners of K ansas City,

and J. V. Lewis, as Superintendent of Parks of Kansas

City, pray tha t a w rit of certiorari be issued to review the

2

judgm ent of the Court of Appeals, of the Eighth Circuit,

entered on June 10, 1953, in the consolidated eases of—

No. 14,664.

City of K ansas City, Missouri, a M unicipal Corporation,

F rank Theis, Paul M. Fogel and Ned J. Fortney, As

M embers of the Board of P ark Commissioners of K ansas

City, Missouri, and J. V. Lewis, As Superintendent of Parks

of K ansas City, Missouri, Appellants,

vs.

E sther Williams, Lena R. Sm ith and Joseph N. Moore,

Appellees,

and

No. 14,666.

Esther Williams, Lena R. Sm ith and Joseph N„ Moore,

Appellants,

vs.

City of Kansas City, Missouri, a M unicipal Corporation,

F rank Theis, Paul M. Fogel and Ned J. Fortney, As

M embers of the Board of P ark Commissioners of Kansas

City, Missouri, and J. V. Lewis, As Superintendent of Parks;

of Kansas City, Missouri, Appellees.

OPINIONS BELOW.

The opinion of the D istrict Court of the W estern Divi

sion of the W estern D istrict of Missouri (R. 24) is re

ported in 104 F. Supp. 848. The opinion in th e Court of

Appeals (R. 93) is not yet officially reported.

3

JURISDICTION.

The judgm ent of the Court of Appeals was entered on

June 10, 1953. On June 26, 1953, the Court of Appeals

stayed the issuance of its m andate for a period of th irty

(30) days (R. 103). The jurisdiction of this Court is in

voked under 28 U. S. C. A., Section 1254(1).

QUESTIONS PRESENTED.

(1) W hether the Court of Appeals, in its decision,

should have fully considered the swimming pool facilities

afforded by K ansas City, Missouri, th rough its Board of

P ark Commissioners, to negroes and w hite persons re

spectively, and have found, as a m atter of law, th a t the

facilities afforded negroes w ere substantially equal to

those furnished w hite persons.

(2) W hether swimming pool facilities furnished

negroes, by the City of Kansas City, Missouri, through its

Board of P ark Commissioners, are substantially equal

to the swimming pool facilities furnished w hite persons,

so tha t negroes are not deprived of th e rights granted by

the Fourteenth A m endm ent to the Constitution of the

United States, and by Section 41, Title 8, U. S. C. A.

(3) W hether the failure to furnish swimming pool

facilities for negroes in Swope Park, such facilities having

been furnished w hite persons, deprived plaintiffs (appel

lees) of the equal protection of th e law as guaranteed by

the Fourteenth A m endm ent to the Constitution of the

United States, and as provided by Sections 41 and 43, of

T itle 8, of the U. S. C. A., even though substantially equal

swimming pool facilities have been provided for negroes

free of charge in a public park im m ediately adjacent to

th a t section of Kansas City inhabited by the larger portion

of the negro population.

4

STATUTES INVOLVED.

Sections 41 and 43, of T itle 8, of the U. S. C. A.

PLEADINGS AND COUNT’S OPINION.

The controversy had its origin in a suit institu ted by

th ree negroes against Kansas City and certain of its of

ficials, alleging tha t they had been denied admission into

the Swope P ark Swimming Pool used exclusively by

whites, and prayed for, among other things, a perm anent

injunction. In the ir petition, as amended, th e plaintiffs

pled (R. 6):

“ * * * and th a t defendants and each of them ,

the ir privies and successors in office be enjoined

perm anently from denying to plaintiffs and all o ther

Negro citizens of K ansas City, Missouri, equal access

to and enjoym ent of the aforesaid recreational facili

ties subject only to rules and regulations applicable

to all without regard to race” (Italics o u rs ).

Thus, the plaintiffs prayed for a ruling th a t segrega

tion in the use of the swimming pool was unconstitutional

per se.

Your petitioners, in the ir amended joint answ er (R.

13, Par. 12) pled:

“Defendants fu rth e r allege tha t since they have

provided substantially equal outdoor swimming pool

facilities for the mem bers of the Caucasian and Negro

Races, respectively, th a t segregation of the races in

the use of said facilities is not in violation of the

Fourteenth A m endm ent to the Constitution of the

United States and tha t neither plaintiffs nor any m em

ber of the negro race has, as a consequence, been de

prived of any righ t guaranteed by said am endm ent to

the Constitution.”

5

In the ir answ er your petitioners relied on the uniform

decisions of the Suprem e Court of the U nited S tates ru l

ing th a t separate public facilities if they are substantially

equal are not violative of the Fourteenth Amendment.

The United States D istrict Court for the W estern Divi

sion of the W estern D istrict of Missouri, in its opinion,

made findings of fact tha t the Parade P ark Swimming

Pool, as constructed and m aintained by defendant, Kansas

City, for use and enjoym ent of negro citizens and resident

taxpayers, is not substantially equal in character, location,

appointm ent and facilities generally w ith m ajor swimming

pools constructed and m aintained by said defendant, for

use and enjoym ent for w hite citizens and resident ta x

payers of said City (R. 36).

And said D istrict Court fu rther adjudged and declared

tha t the refusal of the defendant, the City of K ansas City,

Missouri, acting through its Board of P ark Commissioners

and the Superintendent of Parks, to perm it plaintiffs to

use the Swope P ark Swimming Pool solely because of

race and color w hile granting this righ t to w hite persons,

deprives the plaintiffs of the legal protection of the laws

of the Fourteenth A m endm ent and Sections 41 and 43, Title

8, U. S. C. A., and rights and privileges secured thereunder

(R. 46-47).

In its opinion, the Circuit Court of Appeals stated (U.

S. C. A., p. 8) (R. 93):

“These and the m any other differences pointed out

by the tr ia l court, which we shall not undertake to re

peat, would make it impossible for us to say as a matter

of law tha t the court’s appraisal of the two pools as

not constituting substantially equal facilities for swim

ming enjoym ent was clearly erroneous” (Italics ours).

6

Thus, the Court of Appeals did not ru le tha t the facili

ties of the two pools, one for W hites and one for Negroes,

w ere not substantially equal.

The Court of Appeals also stated in its opinion (U. S.

C. A., p. 6) (R. 97):

“The adm ittance of negroes to Swope Park, the

same as whites, for enjoym ent of it as a general recrea

tion area or center, in accordance w ith the object for

which it was m aintained, bu t w ith a denial to the

negro of the privilege of engaging in diving, swim

ming, wading and sun-bathing activity, as one of the

incidents of the com prehensive recreational program

afforded by the Park to others on an outing occasion,

would constitute in our opinion unequal treatment and

illegal discrimination against the negro in his right to

enjoy Swope Park for w hat it had been made to be

come” (Italics ours).

According to the court’s opinion the “unequal tre a t

m ent and illegal discrim ination” was not based on a com

parison of two pools—Swope P ark and Parade Park, which

was the issue, but upon the City refusing the plaintiffs,

admission to the Swope P ark Pool in a public park w here

they w ere perm itted to use other recreational facilities.

This ruling was foreign to the issues involved.

STATEMENT OF FACTS.

The evidence adduced at the tr ia l developed the fol

lowing facts, as to which there was no dispute.

P lain tiffs are citizens and taxpayers of K ansas City

and m em bers of the negro race. The individual defendants

are m em bers of the Board of P ark Commissioners and

Superintendent of Parks of Kansas City, Missouri, and

w ere acting in their official capacities in respect to th e

7

alleged violation of constitutional rights charged by p lain

tiffs. The City, through said Board, m aintains and op

erates th ree outdoor swimming pools, one in Swope Park

(for w hites exclusively) built in 1942 (R. 65), one in Parade

Park, in the vicinity of 17th and Paseo Boulevard (for

negroes exclusively), bu ilt in 1939 (R. 69), and for th ree

and one-half years thereafter operated as the only m ajor

swimming pool of the City w ith m odern equipm ent and

standard features; and one in Grove Park , near 15th and

Benton (for w hites exclusively), built about forty years

ago.

The City also m aintains and operates a junior swim

ming pool for negroes, consisting of a w ading pool for

small children and a swimming pool for inexperienced

swimmers, built in 1950, and in Nelson C. Crews Park, in

the vicinity of 27th and W oodland Avenue, about ten blocks

south of Parade Park, and three other jun ior swimming

pools for w hites (R. 70). All four junior pools are of the

same size and equipment, built in recent years according

to identical plans, in attractive park and playground areas.

The Penn Valley pool, in the vicinity of 25th and Sum m it

Streets, built as an outdoor swimming pool and reserved

exclusively for w hite persons, was demolished in 1949 to

clear a right-of-w ay for traffic, and has not been replaced.

Character of Facilities.

The w ater used in the Swope P ark Swimming Pool and

the Parade P ark Pool is taken from the same source and is

the same as th a t used for drinking purposes throughout

the City (R. 69). The w ater is trea ted w ith chlorine,

alum and other chemicals and then purified through filtra

tion and circulated under pressure in the pools (R. 69).

Life guards w ith senior Red Cross life guard qualifications,

are constantly m aintained at both pools, the num ber vary

8

ing w ith the num ber of patrons, bu t always sufficient to

provide adequate life guard service (R. 69). There w as

a to tal of tw enty-tw o attendants employed at the P arade

P ark Pool at the tim e suit was institu ted . A t both pools

a system of checking valuables, at a cost of ten cents, is

m aintained, and the same system for checking w earing ap

parel of the patrons is employed. Both pools have separate

toilets for men and women and the said facilities are sub

stantially equal (R. 70). Both pools and the buildings in

connection therew ith are cleaned w ith the same quality

of m aterials and in the same m anner w ith chem ically

trea ted w ater according to the standards set up by the

Am erican Public H ealth Association (R. 70); at both pools

the w ater, buildings, and toilet facilities, are kept at a

high level of cleanliness and sanitary condition (R. 70).

Separate dressing rooms for m en and women, substantially

equal in character, are furnished a t both pools. The P arade

Park Pool for negroes’ dressing room and toilet facilities are

housed in an attractive s tructu re of stone and stucco w ith

the central lobby faced w ith tile (R. 69). Both pools are

substantially equal in their setting in tha t they are su r

rounded by blue grass turf, shade trees and shrubs. The

Parade Park Pool is in the Parade P ark which extends

northw ard to 15th and Paseo, and is bordered on the w est

by The Paseo, a boulevard w ith a double roadway sepa

rated by wide parking of blue grass, trees and shrubs.

The norm al swimming season for both pools is from Ju n e

15th to and including Labor Day (R. 70).

Size of Pools.

The Swope Park Pool has an area of 20,125 square

feet and the P arade P ark Pool an area of 4,725 square feet

(R. 78). The area of the Parade Park Pool is approxi

m ately sixteen per cent of the total area of the th ree m ajor

9

pools and 23.5 per cent of the swimming area of the Swope

P ark Pool alone. The Swope P ark Pool is divided by

concrete partitions, into th ree sections, a shallow one for

children and non-swimmers, a deep one for divers, and the

other, by far the largest of the three, for swimmers gen

erally (R. 73). In the Parade P ark Pool there are no

partitions dividing the pool into com partments, bu t the

portion used by divers is roped off from the portion used

exclusively by swimmers. The Swope Park Pool is pro

vided w ith a sunning beach and autom atic hair dryers, but

these features are not furnished a t the Parade P ark Pool

(R. 73).

Use of Pools.

The population of K ansas City on January 1, 1950, was

456,622, of which 55,682 w ere negroes (R. 76, 78); the

negro population is approxim ately one-eighth, or 12.172,

of the to tal population. The negro population in the last

decade increased th irty -four per cent. Thus, for the colored

population, constituting approxim ately one-eighth of the

whole, one-sixth of the to tal m ajor swimming pool area is

provided. During the swimming season of 1951, there was

a registered attendance of 94,460 at the Swope Park Pool,

or a num ber equal to about tw enty-three per cent of the

total w hite population; there was a registered attendance

of 59,470 at the Parade P ark Pool (R. 76'), or a num ber

equal to about one hundred and six per cent of the to tal

negro population. There w ere 11,795 admissions to the

Nelson C. Crews junior pool (for negroes) registered in

1951, or a num ber equal to tw enty per cent of the to tal

negro population (R. 76). The Parade Park Pool and

the Nelson C. Crews Pool, both for the exclusive use of

negroes, are near the center of a large residential district

occupied alm ost exclusively by negroes, who are served in

10

this d istrict by a YMCA, a YWCA, a high school, grade

schools and churches used exclusively by negroes. Both

pools are located in parks w ith attractive surroundings as

shown by photographs in evidence (Exhibits B to T, in

clusive, R. 62).

Charges at the Pools.

A t the Swope Park Pool a fee of forty cents is charged

adults and tw en ty cents for children under twelve, w ith

free admission for small children before noon on certain

days of the week. A t the P arade P ark Pool th e admission

is free for all patrons, adults and children. N either

negroes nor w hites are taxed for the operation, m ain

tenance and repairs of the Swope P ark Pool. Since its

completion, it has produced revenue supplied by ad

mission fees, totaling $53,515.23 to Septem ber 1, 1951, in

excess of the to tal cost of operation, m aintenance and

repairs (R. 82-83). The cost of operating the Parade P ark

Pool in 1951 was $14,197.48, derived entirely from taxes

(R. 81). Its to tal cost to the taxpayers for five years from

1947 to 1951 was $53,881.75 (R. 77). On hot days the

pool in Parade Park is frequently more overcrowded th an

the pool at Swope Park , as 250 swimmers, w ith 2-hour

shifts, is the largest num ber th a t can be accommodated

at one tim e at the Parade P ark Pool, which is open for the

public from 10:00 a. m., to 10:00 p. m., except on Sundays

w hen it is open to the public from 8:00 a. m., to 10:00 p. m.

(R. 73). The occasional overcrowded condition at

Parade P ark Pool is due in p a rt to the fact tha t no ad

mission fee is charged, resulting, under the regulations

employed, in m any patrons using the pool m ore than once

on a single day (R. 73); said condition is also attributable,

in part, to th e use of the Parade Park Pool facilities by

persons living outside of K ansas City (R. 73). Patrons of

11

the Swope P ark Pool, particu larly on holidays and Sun

days, in extrem ely hot w eather, are at times compelled

to stand in line awaiting the ir tu rn for admission (R. 74).

Junior Swimming Pools.

The junior swimming pool for negroes, m aintained in

the Nelson C. Crews Park, has an area of 1,357 square feet,

or 25 percent of the to tal area of the four junior swim

mining pools; all four of the junior swimming pools are

m aintained in substantially the same condition as to

cleanliness and health, w ith no admission fees charged (R.

76).

SPECIFICATION OF ASSIGNED ERRORS.

I.

The Court of Appeals erred in relying upon M cLaurin

vs. Oklahoma State Regents for H igher Education

as authority for affirm ing the judgm ent and decree

of the D istrict Court.

II.

The Court of Appeals erred in failing to make a full

and detailed comparison between the Swope Park

Swimming Pool Facilities reserved for w hites ex

clusively and the Parade P ark Swimming Pool

Facilities reserved for negroes exclusively.

III.

The Court of Appeals erred in failing to reverse the

judgm ent and decree of the D istrict Court and in not

holding tha t the undisputed facts, as a m atter of

law, showed tha t the swimming pool facilities

furnished negroes w ere substantially equal to those

furnished w hite persons.

12

REASONS RELIED UPON FOR THE GRANTING;

OF THE WRIT.

I.

The Application of the Fourteenth Amendment to

Segregation in the Use of Swimming Pools Has

Never Been Determined by This Court.

We find no record of a decision of the Suprem e Court

of the U nited States in terpreting the scope of the F our

teen th Am endm ent in its application to segregation in the

use of swimming pools. The close association of half-

naked persons in swimming pools w hen complicated by

racial differences sometimes leads to a smoldering resen t

m ent of explosive character. P resently, there are m any

cities in the United States whose combined population in

volves several m illion citizens, confronted w ith the problem

of segregated use of public swimming pools; consequently,

the issues involved in th is case are of great public interest,

national im portance and unique character.

II.

The Court of Appeals Erred in Relying on McLaurin

vs. Oklahoma As Authority for Affirming the

Judgment and Decree of the District Court.

The Court of Appeals relies on the case of McLaurin v.

Oklahoma State Regents for Higher Education et al., 339

U. S. 637, and draw s an analogy betw een tha t case and th e

case at bar. We respectfully subm it th a t the re is no anal

ogy. In the M cLaurin case, there was no other graduate

school for negroes. In Kansas C ity there w as another firs t-

grade swimming pool for negroes substantially equal to

the Swope P ark Pool in all features essential for th e p riv

ilege and pleasure of swimming. If there had been no

13

other m ajor swimming pool for negroes in Kansas City and

if the plaintiffs had been adm itted to the Swope P ark Pool

bu t denied certain privileges therein enjoyed by w hite

persons, then the M cLaurin case m ight apply, bu t p lain

tiffs w ere not adm itted to the Swope P ark Pool at all. The

M cLaurin case is no authority for the decision of the Court

of Appeals in the case at bar.

III.

The Court of Appeals Erred in Failing to Make a

Full and Detailed Comparison Between the Swope

Park Swimming Pool Facilities Reserved for Whites

Exclusively and the Parade Park Swimming Pool

Facilities Reserved for Negroes Exclusively.

The Court of Appeals based its opinion on the single

fact tha t the plaintiffs w ere not adm itted to the Swope

Park Pool although adm itted to Swope Park and to the

use of other recreational facilities therein. The Court of

Appeals ignored and disregarded a comparison of the facili

ties of the two pools and failed to consider all of the factors

which m ust be considered in determ ining the question

of substantial equality of facilities. The record contained

a full, detailed and undispuited statem ent of the physical

facilities, including such v ital elem ents as accessibility to

prospective patrons using the facilities and the im portant

elem ent of entrance fees. The resu lt is tha t there has been

no determ ination in this case of the most vital and signifi

cant question involved.

14

IV.

The Court of Appeals Erred in Classifying Public

Recreational Facilities Such As Golf, Picnic Ovens,

Boating on a Lagoon and Starlight Theatre, in the

Same Category with a Public Swimming Pool

Facility.

There is a distinct line of dem arcation in the in te r

racial implications, and reactions involved between a

swimming pool and a S tarlight Theatre. The innate de

sire of women for physical privacy based on difference

of sex, is a rea l and not a m ythical barrier; sex con

sciousness does not arise from th e interm ingling of per

sons, irrespective of race or color, w hen they are fu lly

clothed on a golf course or in a theatre. To illustrate, if

at both the Swope P ark Pool and the Parade P ark Pool,

the. Board of P ark Commissioners, in th e in terest of

economy, or for o ther reasons, should close the rest rooms

for men and perm it them to use th e rest rooms provided

for women, the la tte r would not use the rest rooms, nor

the pools respectively, not on account of color or race,

but because of an inborn desire for physical privacy. O nly

in a lesser degree do most women, w ith scant swimming

attire, have an aversion to interm ingling in a swimming

pool w ith m ale strangers of another race, and we respect

fully subm it tha t no m andate or decree of Court, w ill

obliterate this tra it of hum an nature .

15

V.

The Court of Appeals Erred in Failing to Reverse

the Judgment and Decree of the District Court and

in Not Holding That the Facts, As a Matter of Law,

Showed That the Swimming Pool Facilities Fur

nished Negroes Were Substantially Equal to Those

Furnished White Persons.

There is no issue of fact in this case.. None of the evi

dence as to the character of the swimming facilities is dis

puted. The tria l court’s finding of fact tha t the Parade

P ark Pool for negroes is not substantially equal in char

acter, location, appointm ents, and features, to the m ajor

pool constructed and m aintained for use and enjoym ent of

w hite citizens and resident taxpayers of Kansas City,

therefore, becomes a question of law.

Therefore, the ruling of the Circuit Court of Appeals

th a t the City was guilty of “ unequal trea tm en t and illegal

discrim ination against the negro” to enjoy the Swope P ark

Swimming Pool involves a question of law only, which the

court did not decide. It was the function and duty of the

Court of Appeals to hold, as a m atter of law, tha t the facili

ties furnished negroes either w ere or w ere not substantially

equal to the facilities furnished w hite persons at the Swope

P ark Swimming Pool. If the Parade P ark Pool furnished

for the exclusive use of negroes was substantially (not

identically) equal to the facilities furnished the w hites at

the Swope P ark Swimming Pool, it was the function and

duty of the Court of Appeals to so find and in tha t event

the segregation employed by the City was law ful and in

accordance w ith the rules of the Suprem e Court of the

U nited States in all segregation cases.

16

CONCLUSION.

For the foregoing reasons, this petition for a w rit of

certiorari should be granted.

In the event the court should gran t the w rit of cer

tiorari, petitioners request the court to enter an order s tay

ing the enforcem ent of the judgm ent below.

Respectfully subm itted,

David M. P roctor,

City Counselor,

Be n j. M. P owers,

Associate City Counselor,

J ohn J. Cosgrove,

Associate City Counselor,

Attorneys for Petitioners.