Holland v. People of Illinois Brief Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

April 12, 1989

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Holland v. People of Illinois Brief Amicus Curiae, 1989. 272e354f-b89a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/6e72da49-2022-4069-aca1-446da72b1114/holland-v-people-of-illinois-brief-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

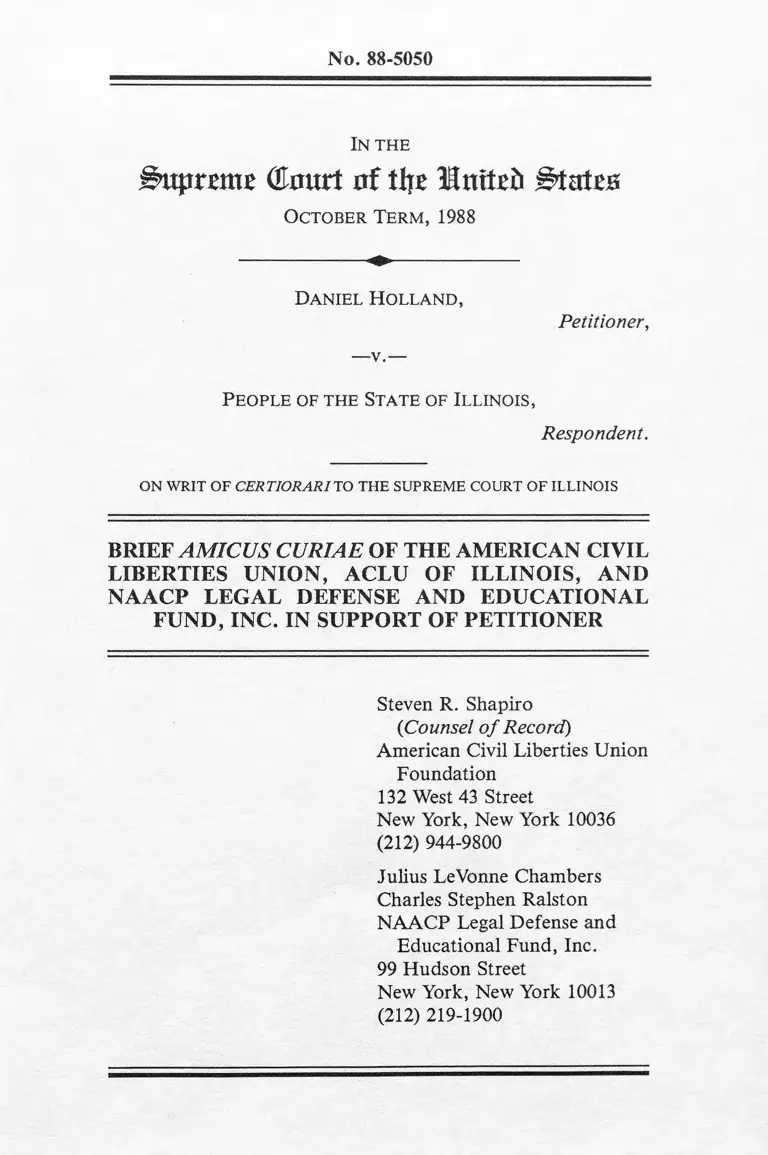

No. 88-5050

In t h e

Batpreme (Emtrt of tljE llttitefc ^tatts

October Term, 1988

Daniel Holland,

Petitioner,

People of the State of Illinois,

Respondent.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARITO THE SUPREME COURT OF ILLINOIS

BRIEF A M IC U S C U R IA E OF THE AMERICAN CIVIL

LIBERTIES UNION, ACLU OF ILLINOIS, AND

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL

FUND, INC. IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONER

Steven R. Shapiro

{Counsel o f Record)

American Civil Liberties Union

Foundation

132 West 43 Street

New York, New York 10036

(212) 944-9800

Julius LeVonne Chambers

Charles Stephen Ralston

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10013

(212) 219-1900

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

1. Is the fair cross-section require

ment of the Sixth Amendment violated by a

prosecutor's use of peremptory challenges

to exclude Black jurors solely on account

of their race?

2. Does a prosecutor's use of peremp

tory challenges to exclude Black jurors

solely on account of their race violate the

Sixth Amendment only if the defendant is

also Black?

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

TABLE OF A U T H O R I T I E S ................... ii

INTEREST OF AMICI ..................... 1

STATEMENT OF THE C A S E ................ 4

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT ................... 5

ARGUMENT ................................. 9

I. A PROSECUTOR'S USE OF PEREMPTORY

CHALLENGES TO EXCLUDE POTENTIAL

JURORS SOLELY ON ACCOUNT OF RACE

VIOLATES THE FAIR CROSS-SECTION

REQUIREMENT OF THE SIXTH

AMENDMENT .......................... 9

II. A DEFENDANT'S RACE SHOULD NOT

DETERMINE HIS STANDING TO CHAL

LENGE A VIOLATION OF THE FAIR

CROSS-SECTION REQUIREMENT . . . . 22

C O N C L U S I O N .............................. 3 2

1

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Page

CASES

Alexander v. Louisiana.

405 U.S. 625 (1972) ..................... 3

Allen v. Hardy.

478 U.S. 255 (1986) ..................... 19

Ballard v. United States.

329 U.S. 187 (1946) .............. . 11, 27

Ballew v. Georgia.

435 U.S. 223 (1978) ................ 15, 26

Batson v. Kentucky.

476 U.S. 79 ( 1 9 8 6 ) ...................passim

Booker v. Jabe.

801 F .2d 871 (6th Cir. 1986),

cert. denied,

479 U.S. 1046 (1987) ...................... 19

Brown v. Allen.

344 U.S. 443 (1953) ..................... 11

Carter v. Jury Commission.

396 U.S. 320 (1970) ......................3

Duncan v. Louisiana.

391 U.S. 145 (1968) .............. 10

Duren v. Missouri.

439 U.S. 357 (1979) ..................... 20

ii

Page

Harris v. Texas,

467 U.S. 1261 (1984) ...................... 18

Hobby v. United States.

468 U.S. 339 (1984) ..................... 28

Lockhart v. McCree.

476 U.S. 162 (1986) ................ 18, 19

McCray v. Abrams.

750 F.2d 1113 (2d Cir. 1984),

vacated and remanded.

478 U.S. 1001 ( 1 9 8 6 ) ............ 1, 16, 19

McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green.

411 U.S. 792 (1973) ..................... 21

Michigan v, Booker.

478 U.S. 1001 ( 1 9 8 6 ) ..................... 19

Mitchell v. Johnson,

250 F.Supp. 117 (M.D.Ala. 1966) . . . . 3

Peters v. Kiff.

407 U.S. 493 (1972) . . . . 8, 23, 26, 30

Roman v. Abrams.

822 F .2d 214 (2d Cir. 1987),

cert, denied, ___ U.S. ___ ,

57 U.S.L.W. 3570 (Feb. 27, 1989) . . . . 20

Rose v. Mitchell.

443 U.S. 545 (1979) ................ 26, 29

Smith v. Texas.

311 U.S. 128 (1940) ..................... 11

Page

Strauder v. West Virginia.

100 U.S. 303 (1880) .............. 28

Swain v. Alabama.

380 U.S. 202 (1965) ..................... 3

Taylor v. Louisiana.

419 U.S. 522 (1975) .............. . passim

Teague v. Lane.

109 S.Ct. 1060 (1989) . . . . . . . passim

Thiel v. Southern Pacific Co.,

328 U.S. 217 (1946) .............. 13

Turner v. Fouche.

396 U.S. 346 (1970) ..................... 3

Williams v. Florida.

399 U.S. 78 ( 1 9 7 0 ) ................... 12, 16

Witherspoon v. Illinois.

391 U.S. 510 (1968) ..................... 15

STATUTES

Federal Jury Selection and

Service Act of 1968,

28 U.S.C. §§1861, et seg..................13

LEGISLATIVE HISTORY

H.R.Rep. No. 1076,

90th Cong., 2d Sess. (1968) ............ 14

iv

Page

OTHER AUTHORITIES

Goldwasser, "Limiting A

Criminal Defendant's Use Of

Peremptory Challenges: On

Symmetry And The Jury In A

Criminal Trial,"

102 Harv. L. Rev. 808 ( 1 9 8 9 ) .............. 28

Uniform Jury Selection and

Service Act, (National

Conference of Commissioners

on Uniform State Laws, 1970) ............ 13

v

INTEREST OF AMICI-V

The American Civil Liberties Union

(ACLU) is a nationwide, nonpartisan organ

ization with over 250,000 members dedicated

to the principles of liberty and equality

embodied in the Constitution and civil

rights laws of this country. The ACLU of

Illinois is one of its state affiliates.

As part of its commitment to legal

equality, the ACLU has long opposed any and

all forms of racial discrimination in the

administration of justice. Of particular

relevance here, the ACLU represented peti

tioner in McCray v. Abrams. 750 F.2d 1113

(2d Cir. 1984), vacated and remanded. 478

U.S. 1001 (1986), the first federal case

holding that a prosecutor's use of

^ Pursuant to Rule 36.2, letters of consent to

the filing of this brief have been lodged with the

Clerk of the Court.

1

peremptory challenges to screen prospective

jurors on the basis of race violates the

Sixth Amendment.

The NAACP Legal Defense and Education

al Fund, Inc., is a nonprofit corporation,

incorporated under the laws of the State of

New York in 1939. It was formed to assist

Blacks to secure their constitutional

rights by the prosecution of lawsuits. Its

charter declares that its purposes include

rendering legal aid without cost to Blacks

suffering injustice by reason of race who

are unable, on account of poverty, to

employ legal counsel on their own behalf.

For many years, its attorneys have repre

sented parties and have participated as

amicus curiae in this Court and in the

lower federal courts in cases involving

many facets of the law.

2

The Fund has a long-standing concern

with the issue of exclusion of Blacks from

service on juries. Thus, it has raised

jury discrimination claims in appeals from

criminal convictions,A/ pioneered in the

affirmative use of civil actions to end

discriminatory practices^/ and, indeed,

represented the petitioner in Swain v.

Alabama, 380 U.S. 202 (1965), the case

which first raised the issue of the use of

peremptory challenges to exclude Blacks

from jury venires.

More recently, both the ACLU and the

Fund participated as amicus curiae in

Batson v. Kentucky. 476 U.S. 79 (1986), and

A/ E.q. , Alexander v. Louisiana. 405 U.S. 625

(1972) .

A/ Carter v. Jury Commission, 396 U.S. 320

(1970); Turner v. Fouche. 396 U.S. 346 (1970);

Mitchell v. Johnson. 250 F.Supp. 117 (M.D.Ala.

1966).

3

Teaaue v. Lane, 109 S.Ct. 1060 (1989), two

cases that raised issues similar to the

issues presented here.

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

The petitioner in this case was

convicted by an all-white jury after the

prosecutor used his peremptory challenges

to exclude the only two potential Black

jurors. Petitioner objected to those

exclusions both at trial and on appeal.

His objections were rejected by the

Illinois state courts at every stage.

Most significantly, the Illinois

Supreme Court ruled that petitioner did not

have standing to raise a Batson claim

because he is white and the excluded jurors

were Black. People v. Holland. 121 111.2d

136, 157 (1988). The Illinois Supreme

Court also rejected petitioner's Sixth

4

Amendment claim on the ground that the fair

cross-section requirement of the Sixth

Amendment does not apply to the petit jury.

Id. at 158.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

Under the Sixth Amendment, every

criminal defendant has the constitutional

right to be tried before an impartial jury

drawn from a fair cross-section of the

community. Contrary to the view of the

court below, this fair cross-section

requirement does not apply only to the jury

venire. Indeed, any such limitation would

be illogical and self-defeating.

The only function of the jury venire

is to serve as a pool from which petit

juries are chosen. The only reason for

insisting that the jury venire reflect a

fair cross-section of the community is to

5

maximize the possibility that petit juries

chosen from that pool will be similarly

representative.

That possibility may not always ripen

into reality. In individual cases, the

process of random selection and non-racial

exclusion may produce all-white or all-

Black juries. For both practical and

principled reasons, therefore, the Consti

tution does not guarantee proportional

representation on the petit jury, nor does

petitioner seek that result. It is quite

another thing, however, when the government

uses its peremptory challenges as part of

an intentional strategy to exclude poten

tial jurors solely because of their race.

There is no state interest that supports

such behavior, as this Court properly

recognized in Batson v. Kentucky. 476 U.S.

162 (1986) .

6

While Batson obviously rested on equal

protection grounds, the government's delib

erate misuse of its peremptory challenges

is also inconsistent with the underlying

purposes of the fair cross-section require

ment. Indeed, this Court has invoked the

fair cross-section requirement on several

occasions to strike down other efforts by

the government to distort the jury selec

tion process based on impermissible

criteria. The analysis in this case should

be precisely the same.

The fact that the petitioner in this

case is white and the excluded jurors were

Black should have no bearing on the out

come. The values served by the fair cross-

section requirement do not turn on the

racial or sexual identity of the defendant.

Thus, in Taylor v. Louisiana. 419 U.S. 522,

526 (1975), this Court specifically upheld

7

a male defendant's standing to challenge

the exclusion of female jurors on fair

cross-section grounds.

The decision in Taylor effectively

resolves the standing issue in this case.

More generally, however, amici believe that

the rationale of Tavlor should apply in any

case involving discriminatory jury selec

tion, regardless of the constitutional

theory on which the case proceeds. As this

Court observed in Peters v. Kiff. 407 U.S.

493, 498 (1972), "[t]he exclusion of

Negroes from jury service, like the arbi

trary exclusion of any other well-defined

class of citizens, offends a number of

related constitutional values." Not the

least of these is the interest of the

excluded juror, who has no other practical

way to voice her complaint except through

the medium of the defendant.

8

Amici acknowledge, of course, this

Court's reference in Batson to a criminal

defendant's right to challenge potential

jurors "of the defendant's race." 476 U.S.

at 96. In light of contrary precedent,

however, amici respectfully suggest that

this reference can best be understood as an

allusion to the facts of Batson and not a

statement of the controlling law, even in

equal protection cases.

ARGUMENT

I. A PROSECUTOR'S USE OF PEREMPTORY

CHALLENGES TO EXCLUDE POTENTIAL

JURORS SOLELY ON ACCOUNT OF RACE

VIOLATES THE FAIR CROSS-SECTION

REQUIREMENT OF THE SIXTH AMENDMENT

The principal issue in this case is

whether a prosecutor's use of peremptory

challenges to exclude potential jurors on

the basis of race violates the fair cross-

section requirement of the Sixth Amend

9

ment.3/ Four members of this Court ex

pressed their views on that subject only a

few weeks ago in Teague v. Lane.4/ All

four agreed with Justice Stevens, who

wrote:

It is clear to me that a procedure

that allows a prosecutor to exclude

all black venirepersons, without any

reason for the exclusions other than

their race appearing in the record,

does not comport with the Sixth Amend

ment's impartiality requirement.

109 S.Ct. at 1079 n.l. See also, id. at

1079 (Blackmun, J.); id. at 1091-92 (Bren

nan and Marshall, JJ.).

This Court's decisions fully support

that conclusion. Indeed, this Court has

3/ The jury trial provisions of the Sixth Amend

ment were applied to the states through the Four

teenth Amendment in EXmcan v. Louisiana. 391 U.S.

145 (1968).

y Because of its holding on the scope of habeas

relief, the majority opinion expressly declined to

address the Sixth Amendment question presented in

Teague. 109 S.Ct. at 1069.

10

repeatedly stressed that "the selection of

a petit jury from a representative cross

section of the community is an essential

component of the Sixth Amendment right to a

jury trial." Taylor v. Louisiana. 419 U.S.

at 528.

Thus, in Smith v. Texas. 311 U.S. 128,

130 (1940), the Court declared that the

exclusion of racial groups from jury serv

ice was "at war with our basic concepts of

a democratic society and a representative

government." In Ballard v. United States.

329 U.S. 187, 191 (1946), the Court relied

on a federal statutory "design to make the

jury 'a cross-section of the community,'"

in reversing a conviction by a jury from

which all women had been excluded. In Brown

V. Allen, 344 U.S. 443, 474 (1953), the

Court asserted that jury lists must "rea

sonably reflect[s] . . . a cross-section of

11

the population suitable in character and

intelligence for that civic duty." And in

Williams v. Florida. 399 U.S. 78, 100

(1970), the constitutional validity of a

six-person jury was upheld on the ground

that it was both "large enough to promote

group deliberation . . . and to provide a

fair possibility for obtaining a repre

sentative cross-section of the community."

Summarizing this case law in Taylor,

the Court declared:

We accept the fair-cross-section as

fundamental to the jury trial guaran

teed by the Sixth Amendment and are

convinced that the requirement has

solid foundation. The purpose of a

jury is to guard against the exercise

of arbitrary power — to make availa

ble the commonsense judgment of the

community as a hedge against the over-

zealous or mistaken prosecutor . . .

This prophylactic vehicle is not

provided if the jury pool is made up

of only special segments of the

populace or if large, distinctive

groups are excluded from the pool.

Community participation in the admin

istration of the criminal law, more-

12

over, is not only consistent with our

democratic heritage but is also

critical to public confidence in the

fairness of the criminal justice

system . . . " [T]he broad representa

tive character of the jury should be

maintained, partly as assurance of a

diffused impartiality and partly

because sharing in the administration

of justice is a phase of civic respon

sibility." Thiel v. Southern Pacific

Co.. 328 U.S. 217, 227 (1946)(Frank

furter, J . , dissenting).

419 U.S. at 530-31.

The requirement of a fair cross-

section in jury selection has also been

adopted by statute as "the policy of the

United States."5/ The basis for this

-§/ See Federal Jury Selection and Service Act of

1968, 28 U.S.C. §§1861, et seq. Section 1862 pro

vides:

No citizen shall be excluded from jury

service as a grand or petit juror . . . on

account of race, color, religion, sex,

national origin, or economic status.

See also. Uniform Jury Selection and Service Act,

§2 (National Conference of Commissioners on Uniform

State Laws, 1970).

13

"policy" was set forth in the accompanying

House Report:

It must be remembered that the jury is

designed not only to understand the

case, but also to reflect the communi

ty's sense of justice in deciding it.

As long as there are significant

departures from the cross sectional

goal, biased juries are the result —

biased in the sense that they reflect

a slanted view of the community they

are supposed to represent.

H.R.Rep. No. 1076, 90th Cong., 2d Sess. 8

(1968), quoted in Taylor v. Louisiana, 419

U.S. at 529 n .7.

Respondent does not quarrel with this

general proposition. Instead, the state

argues that the fair cross-section require

ment applies only to the jury venire and

not to the jury panel. This Court has

never adopted that proposition, at least in

the very broad sense that respondent now

urges it. To the contrary, this Court has

often referred with approval to the fair

14

cross-section requirement in cases dealing

solely with the composition of the petit

jury.

For example, in Ballew v. Georgia. 435

U.S. 223 (1978), this Court held that a

five-person jury was too small to represent

the community's judgment in a meaningful

way — in part because a five-person jury

threatened "the representation of minority

groups in the community," id. at 236

although there was no indication that the

jury venire was in any way defective or

unrepresentative.

Similarly, in Witherspoon v. Illinois.

391 U.S. 510 (1968), the Court struck down

a legislative scheme that permitted the

prosecution to challenge for cause any

potential juror opposed to the death

penalty. In Witherspoon, as in Ballew. the

concern focused clearly on the jury panel

15

rather than the jury venire. See also

Apodaca v. Oregon. 406 U.S. 404, 410-11

(1972); Williams v. Florida. 399 U.S. 78,

100 (1970).£/

That focus is plainly correct. The

point of demanding a representative jury

pool is to maximize the chance of obtaining

a representative jury. McCray v. Abrams,

750 F.2d at 1124-25. The intentional

exclusion of potential jurors on the basis

of race, whether in the process of com

piling a jury pool or selecting a jury

panel, is equally destructive of this

constitutional goal.-2/ " [T]he State may

For a careful analysis of this Court's Sixth

Amendment decisions, see McCray v. Abrams. 750 F.2d

1113 (2d Cir. 1984), vacated and remanded. 106

S.Ct. 3289 (1986).

2/ Another goal of the fair cross-section

requirement recognized in Taylor is to promote

"public confidence in the fairness of the criminal

justice system." 419 U.S. at 530. Such confidence

(continued__)

16

not draw up its jury lists pursuant to

neutral procedures but then resort to dis

crimination at 'other stages in the selec

tion process.'" Batson. 476 U.S. at 88.

Amici do not suggest that the jury

chosen in any particular case must faith

fully duplicate the demographic profile of

the surrounding community. See Teague v.

Lane, 109 S.Ct. at 1090-91 (Brennan, J.,

dissenting). As this Court has held,

" [d]efendants are not entitled to a jury of

any particular composition." Taylor v.

Louisiana. 419 U.S. at 538. But the con

stitutional imperative of an impartial

jury drawn from a fair cross-section of the

community that Taylor endorsed is undenia-

U (...continued)

is unlikely to be felt by a minority community

that observes the systematic exclusion of every

Black juror through the prosecutor's use of per

emptory challenges.

17

bly frustrated by the prosecutor's use of

peremptory challenges to exclude potential

jurors on the basis of race alone.£/

Lockhart v. McCree. 476 U.S. 162

(1986), is not to the contrary. Fairly

read, the statement in Lockhart that

"extension of the fair-cross-section

requirement to petit juries would be

unworkable and unsound," id. at 174, only

rejected the notion of proportional repre

sentation on the petit jury. It did not

reject, or even address, the claim pre

sented by petitioner here.

-§/ "When the prosecution employs its peremptory

challenges to remove from jury participation all

Negro jurors, the right guaranteed in Taylor is

denied just as effectively as it would be had

Negroes not been included on the jury rolls in the

first place." Harris v. Texas. 467 U.S. 1261, 1262

(1984)(Marshall, J., dissenting from the denial of

certiorari).

18

Indeed, shortly after Lockhart was

announced, this Court vacated and remanded

the decisions in Abrams v. McCray. 478 U.S.

1001 (1986), and Michigan v. Booker. 478

U.S. 1001 (1986) — two cases holding that

the discriminatory use of peremptory chal

lenges violates the Sixth Amendment —

without even mentioning Lockhart .■§■/ Fur

thermore, the Sixth Amendment rulings in

McCray and Booker were reaffirmed on remand

and, in each case, this Court subseguently

declined review. See Booker v. Jabe. 801

F.2d 871 (6th Cir. 1986), cert, denied. 479

5/ Both cases were remanded "for further consid

eration in light of" Batson and the retroactivity

ruling in Allen v. Hardy. 478 U.S. 255 (1986).

Chief Justice Burger filed a dissenting opinion

from the remand order in Booker, in which he argued

that its Sixth Amendment holding should be summa

rily reversed. 478 U.S. at 1001-02. Even Chief

Justice Burger, however, did not mention Lockhart

as the basis for his conclusion. Moreover, no

other member of the Court joined in his opinion.

19

U.S. 1046 (1987); Roman v. Abrams, 822

F . 2d 214, 224-27 (2d Cir. 1987), cert.

denied. ___ U.S. ___ , 57 U.S.L.W. 3570

(Feb. 27, 1989).

The flaw in respondent's reliance on

the rule against proportional representa

tion is best illustrated by example.

Assume a county that is 20% Black and that

has a jury roll that is also 20% Black. In

trial #1, 20 potential jurors are randomly

selected, one of whom is Black, a result

well within the range of probability. That

single Black is then excused for a valid,

racially-neutral reason. The resulting,

all-white jury does not violate the Sixth

Amendment, and neither petitioner nor amici

have ever claimed otherwise.-1-0/

10/ it is in this narrow sense that the majority

in Teague distinguished this Court's reliance on

statistical comparisons in Duren v. Missouri. 439

(continued__)

20

In trial #2, twenty potential jurors

are once again chosen through a process of

random selection. This time, four of the

selected jurors are Black, or 20%. Uti

lizing neutral criteria, two of the Blacks

are excused from jury service. Not content

with that outcome, our hypothetical prose

cutor then challenges the remaining two

Black jurors on racial grounds, thus

affirmatively creating an unrepresentative

jury.

■3=2/ (... continued)

U.S. 357 (1979), to establish a violation of the

fair cross-section requirement with regard to the

jury venire. 109 S.Ct. at 1070 n.l. The inappro

priateness of statistical evidence in certain

contexts, however, has never meant that discrimina

tion cannot be proved in other ways. Cf. McDonnell

Douglas Corp. v. Green. 411 U.S. 792 (1973).

Indeed, that recognition formed the basis for this

Court's decision in Batson. There is no apparent

reason why the evidentiary rules should be any

different in a Sixth Amendment case.

21

Under any reasonable interpretation of

the Sixth Amendment, this invidious manipu

lation of the jury system must be deemed

unconstitutional. To rule otherwise would

mean that the Sixth Amendment guarantees

little more than the right of Blacks and

other minorities to be summoned for jury

duty and then summarily dismissed because

of their race. The constitutional framers

could not have intended such a hypocritical

result.

II. A DEFENDANT'S RACE SHOULD

NOT DETERMINE HIS STANDING TO

CHALLENGE A VIOLATION OF THE

FAIR CROSS-SECTION REQUIREMENT

In holding that a white defendant

lacks standing to object to the discrim

inatory exclusion of Black jurors, the

Illinois Supreme Court made two fundamental

errors. First, its judgment that a white

22

defendant suffers no injury-in-fact when

Black jurors are excluded necessarily rests

on precisely the sort of racial stereo

typing that this Court rejected as improper

in Batson. Second, its decision implicitly

assumes that the defendant's interest is

the only interest of constitutional magni

tude in assessing the impact of an unrepre

sentative jury. This Court has never taken

such a narrow view of the jury's role in

the administration of justice.

Having begun with false premises, it

is hardly surprising that the Illinois

Supreme Court ultimately reached a conclu

sion that directly conflicts with explicit

rulings of this Court on the standing ques

tion. Specifically, in Peters v. Kiff. 407

U.S. 493, 504 (1972), the Court held that

whatever his race, a criminal defend

ant has standing to challenge the

system used to select his grand or

23

petit jury, on the ground that it

arbitrarily excludes from service the

members of any race . . . .

Likewise, in Taylor v. Louisiana, this

Court upheld the right of a male defendant

to challenge the exclusion of women from

jury service, stating:

Taylor was not a member of the ex

cluded class; but there is no rule

that claims such as Taylor presents

may be made only by those defendants

who are members of the group excluded

from jury service.

419 U.S. at 526.

The distinction that the Illinois

Supreme Court drew for standing purposes

between white and Black defendants only

makes sense if one assumes that jurors are

more likely to vote their race than their

conscience. Operating on that assumption,

the court below appeared to believe that a

white defendant's chance for acquittal

actually increased (or at least did not

24

diminish) by the exclusion of potential

Black jurors. Thus, the court implied, a

white defendant has nothing to complain

about under those circumstances.

It is just as inappropriate, however,

to base standing doctrine on racial stereo

types as it is to base a prosecutor's use

of peremptory challenges on racial stereo

types. As Batson makes clear:

Competence to serve as a juror ulti

mately depends on an assessment of

individual qualifications and ability

impartially to consider evidence pre

sented at a trial. A person's race

simply "is unrelated to his fitness

as a juror."

476 U.S. at 87 (citations omitted).

Once jurors are seen as individuals

rather than members of a racial group, it

is impossible to sustain the facile assump

tion that a white defendant can never be

harmed by the discriminatory selection of

an all-white jury.

25

When any large and identifiable seg

ment of the community is excluded

from jury service, the effect is to

remove from the jury room qualities of

human nature and varieties of human

experience, the range of which is

unknown and perhaps unknowable. It is

not necessary to assume that the

excluded group will consistently vote

as a class in order to conclude, as we

do, that their exclusion deprives the

jury of a perspective on human events

that may have unsuspected importance

in any case that may be presented.

Peters v. Kiff. 407 U.S. at 503-04 (foot

note omitted).Ai/

In addition, this Court has repeatedly

emphasized that jury discrimination harms

not only the accused, but "society as a

whole." Rose v. Mitchell, 443 U.S. 545,

556 (1979). "[Tjhere is injury to the jury

system, to the law as an institution, to

A V See also Ballew v. Georgia, 435 U.S. at 234

("the counterbalancing of various biases is

critical to the accurate application of the common

sense of the community to the facts of any given

case") .

26

the community at large, and to the demo

cratic ideal reflected in the processes of

our courts." Ballard v. United States. 329

U.S. at 195. Accordingly, the Court in

Ballard refused to permit the perpetuation

of all-male juries in federal court

although acknowledging that the presence of

women on the jury "may not in a given case

make an iota of difference. Yet a flavor,

a distinct guality is lost if either sex is

excluded." Id. at 193-94.

The loss of those qualities referred

to in Ballard — whether the challenged

exclusion is based on race, religion or

sex — inevitably affects the public per

ception of justice.

There is good reason why public

confidence in the integrity of the

judiciary is diminished whenever

invidious prejudice seeps into its

processes. This diminution of confi

dence largely stems from a recognition

that the institutions of criminal

27

justice serve purposes independent of

accurate factfinding. These institu

tions also serve to exemplify, by the

manner in which they operate, our

fundamental notions of fairness and

our central faith in democratic norms.

Hobby v. United States. 468 U.S. 339, 352

(1984)(Marshall, J . , dissenting)(footnote

omitted).12/

These important social values are

jeopardized by jury discrimination regard

less of the defendant's race.12/ Moreover,

12/ For the excluded juror, the prosecutor's dis

criminatory exercise of peremptory challenges con

veys an official message of second-class citizen

ship that is even more direct and personal. Over a

century ago, this Court observed that jury discrim

ination denies excluded jurors "the privilege of

participating equally . . . in the administration

of justice," and thereby places "a brand upon them,

affixed by the law; an assertion of their

inferiority . . . " Strauder v. West Virginia. 100

U.S. 303, 308 (1880).

22/ See generally. Goldwasser, "Limiting A

Criminal Defendant's Use Of Peremptory Challenges:

On Symmetry And The Jury In A Criminal Trial," 102

Harv.L.Rev. 808, 835 (1989)("The harm that race-

based prosecution perernptories inflict on excluded

jurors and the community does not disappear when

(continued...)

28

only the defendant is in a position to

protect these social values by objecting to

the state's discriminatory jury practices.

This Court has recognized as much on

numerous occasions:

It is clear from the earliest cases

applying the Equal Protection Clause

in the context of racial discrimina

tion in the selection of a . . . jury,

that the Court from the first was

concerned with the broad aspects of

racial discrimination that the Equal

Protection Clause was designed to

eradicate, and with the fundamental

social values the Fourteenth Amendment

was adopted to protect, even though it

addressed the issue in the context of

reviewing an individual criminal con

viction .

Rose v. Mitchell. 443 U.S. at 555.

The decision below largely ignores

this Court's extensive body of case law

discussing the problem of jury discrimina-

^2/ (...continued)

the jurors and the defendant are members of

different races").

29

tion. Its one paragraph discussion on

standing relies entirely on a single com

ment from Batson, which refers to a

defendant's right to challenge the exclu

sion of jurors "of the defendant's race."

476 U.S. at 96.

That comment accurately describes the

facts of Batson itself. To elevate it into

a controlling principle of law, it is nec

essary to believe that this Court intended

to overrule its decision in Peters v. Kiff

without even mentioning it. Nothing in

Batson even remotely supports that unlikely

interpretation. It is less likely still

that Batson intended to overrule the law on

Sixth Amendment standing established in

Taylor v. Louisiana when the merits of

Batson's Sixth Amendment claim were never

reached by the Court. 476 U.S. at 85 n.4.

30

The dispute over standing is more than

an academic one. If the defendant does not

have standing to object in cases like this

one, then nobody does. And unlike many

other contexts where the absence of stand

ing means the absence of harm, that is not

the case here.

Put in its starkest terms, the prac

tical consequence of the decision below is

to condone, in a wide category of cases,

the very sort of invidious discrimination

that this Court condemned only three years

when Batson was decided. Amici urge this

Court not to endorse that result.

31

CONCLUSION

For the reasons stated herein, the

decision below should be reversed.

Respectfully submitted,

Steven R. Shapiro

(Counsel of Record)

John A. Powell

American Civil Liberties

Union Foundation

132 West 43 Street

New York, N.Y. 10036

(212) 944-9800

Julius LeVonne Chambers

Charles Stephen Ralston

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street

New York, N.Y. 10013

(212) 219-1900

Dated: April 12, 1989

32

RECORD PRESS, INC., 157 Chambers Street, N.Y. 10007 (212) 619-4949

74002 • 53