Speed v Tallahassee FL Petitioners Reply Brief

Public Court Documents

March 12, 1958

8 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Speed v Tallahassee FL Petitioners Reply Brief, 1958. 624857e6-c49a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/6e7a6367-3790-4e29-b9a7-820798c161c1/speed-v-tallahassee-fl-petitioners-reply-brief. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

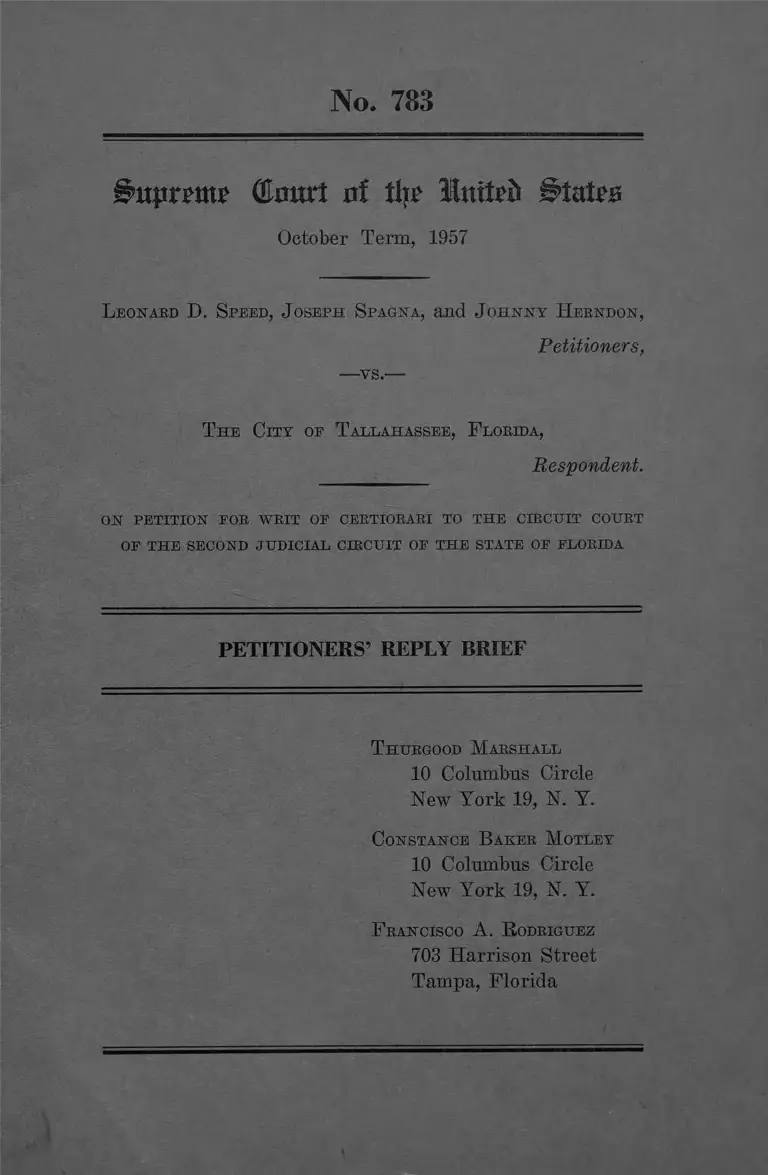

No. 783

Supreme Qloitrt ai % Inttpfr States

October Term, 1957

L eonard D. Speed, J oseph Spagna, and J ohnny IJeendon,

Petitioners,

—vs.—

T he City op T allahassee, F lorida,

Respondent.

on petition poe writ op ceetiobaei to the circuit court

op the second judicial circuit op the state op ploeida

PETITIONERS’ REPLY BRIEF

T hurgood M arshall

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, N. Y.

Constance Baker M otley

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, N. Y.

F rancisco A. R odriguez

703 Harrison Street

Tampa, Florida

•c>iqjri'nu' CEourt at % HtutP& States

October Term, 1957

No. 783

L eonard D. Speed, J oseph Spagna, and J ohnny H erndon,

—vs.—

Petitioners.

T he City of T allahassee, F lorida,

Respondent.

ON P E TIT IO N FOR W R IT OF CERTIORARI TO T H E CIRCUIT COURT

OF T H E SECOND JU D IC IA L CIRCUIT OF T H E STATE OF FLORIDA

PETITIONERS’ REPLY BRIEF

I.

The judgment of the Circuit Court was not reviewable

by certiorari in the Florida courts.

Respondent claims that this Court is without jurisdic

tion under Title 28, United States Code, §1257(3) to review

the judgment of the Circuit Court of the Second Judicial

Circuit of Florida since, says respondent, its judgment

could have been reviewed by the District Court of Appeal

and by the Supreme Court of Florida and is, therefore,

not a final judgment.

Respondent concedes that no further appeal was possible

under Florida law in this case since by both the Constitution

2

of Florida, Article V, §6 (1956)1 and the laws of Florida,

Florida Statutes Annotated, §26.53, the Circuit Court has

final appellate jurisdiction. Cf. Curry U-Drive It v. Boss,

89 So. 2d 796 (1956); Cf. American National Bank of Jack

sonville v. Marks, 45 So. 2d 336 (1950); Malone v. City of

Quincy, 66 Fla. 52 (1913). However, respondent contends

that petitioners could have secured a review of their

claimed denial of rights secured by the Federal Constitu

tion via common law writ of certiorari2 issuing from the

District Court of Appeal and the Supreme Court of

Florida.

In Florida, it has always been the rule that review upon

common law writ of certiorari to a lower court of record

is limited to two questions only: (1) whether the inferior

court exceeded its jurisdiction and (2) whether the inferior

court followed the proper procedure.

Certiorari is not available in Florida to review an errone

ous decision.

The Supreme Court of Florida, in 1950, in American

National Bank of Jacksonville v. Marks, supra, reiterated,

for the express benefit of the Florida bar, this limited scope

of review which is available by common law certiorari. The

Supreme Court of Florida has adhered to these limitations.

Wilson v. McCoy Mfg. Co., 69 So. 2d 659 (1954); Neivert v.

Evans, 82 So. 2d 599, 600 (1955); Tropical Park v. Batcliff,

97 So. 2d 169, 174 (1957).

Petitioners challenge neither the jurisdiction of the trial

or appellate court in this case nor the procedure adopted

by either.

1 Circuit courts had final appellate jurisdiction in such cases

under the old constitution. Florida Constitution (1885) Article

V, §11.

2 There is no statutory certiorari applicable to appeals from

municipal courts to circuit courts as in the case of appeals from

civil courts of record to the circuit courts as provided by Florida

Statutes Annotated §33.12.

3

In the cases cited by respondent, in which review of the

validity of city ordinances was obtained in the Supreme

Court of Florida upon common law certiorari, the Court

specifically referred to the limited scope of review on com

mon law certiorari in Florida which was reiterated by that

Court in the American National Bank case, supra, and it is

also clear that in each of these cases the court considered

the petitioners’ challenge to the jurisdiction of the munic

ipal court involved. Malone v. City of Quincy, 66 Fla. 52,

62 So. 922 (1913); Hunt v. City of Jacksonville, 34 Fla. 504,

16 So. 398 (1894); Mernauglv v. City of Orlando, 41 Fla. 433,

27 So. 34 (1899).

In the Hunt case, which was the first one decided, the

court in its opinion specifically referred to the limited scope

of the review available upon certiorari (at 508) and spe

cifically pointed out that petitioner, who had been convicted

of violating a city ordinance, sought certiorari upon a chal

lenge to the jurisdiction of the municipal court to try him

for the offense (at 505). His claim was that the offense

charged had been made an indictable offense by state law

entitling him to a jury trial which the municipal court could

not give because limited to trials without juries. In this

case, however, the Court found no lack of jurisdiction or

irregularity of procedure.

In the Mernaugh case, which followed, the Court again

pointed out the limited scope of review (at 442) and again

specifically pointed out that petitioner sought certiorari

upon a challenge to the jurisdiction of the municipal court

on the ground that since the City was without power under

state law to enact an ordinance prohibiting the sale of

liquor which he had been convicted of violating, its court

was without jurisdiction to enforce same (at 436). The

Court agreed with petitioner and held that the City was

without authority to pass the ordinance and, therefore, its

court was without jurisdiction to enforce it.

4

In the Malone case, a similar challenge was made to the

power of the City of Quincy to enact the ordinance which

petitioner had been convicted of violating1 and the Court

similarly held that the City being without power to pass the

ordinance, its court was without jurisdiction to enforce

same. Although there is no specific reference by the Court

in its opinion in the Malone case to a challenge to the

jurisdiction of the municipal court by petitioner, it should

be noted that in its opinion the Court cites and relies on

the Hwit case when it again specifically refers to the

limited scope of review upon common law certiorari (at

56). It is thus clear that in the Malone case the Florida

Supreme Court was also proceeding upon the theory that

petitioner was challenging the jurisdiction of the municipal

court to try him for the offense.

Here petitioners neither challenge the power of the City

of Tallahassee to enact an ordinance which purports to

regulate the seating of passengers on local buses nor the

power of its court to enforce a regulatory ordinance on this

subject. The cases cited by respondent are, therefore, not

apposite here.

II.

The judgments o f the Municipal Court and Circuit

Court rest on a denial o f petitioners’ claim of violation

of rights secured by the due process and equal protec

tion clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment.

As the transcript of the proceedings in the trial court

discloses, at the close of the respondent’s case, petitioners

moved for a directed verdict on the ground that the ordi

nance violates rights secured by the State Constitution and

by the due process and equal protection clauses of the

Fourteenth Amendment to the Federal Constitution (T. 62).

5

The argument of petitioners’ counsel and the cases cited

by him show conclusively, however, that his reliance was

upon rights secured by the Federal Constitution and not

by the State Constitution (T. 62-69). Consequently, when

the Municipal Court, in denying the motion, ruled that the

ordinance was clothed with a presumption of constitution

ality and that nothing had been presented by way of testi

mony to overcome this presumption, it is clear that the

court was invoking this familiar rule with respect to the

particular constitutional attack made upon the ordinance,

which, as the record shows, was limited solely to an attack

on federal constitutional grounds. And where, as here,

the record clearly spells out that the sole attack upon the

ordinance was on federal grounds, all doubt- is precluded.

Konigsberg v. State Bar of California, 353 U.8. 252 (1957).

When petitioners appealed to the Circuit Court, they

assigned as grounds for appeal, among others, the trial

court’s refusal to grant their motion for directed verdict.

The Circuit Court had before it the transcript of the pro

ceedings in the trial court which showed that petitioners’

only attack upon the ordinance was on federal constitu

tional grounds. An examination of the briefs submitted

by both petitioners and respondent in the Circuit Court

shows that neither argument was based on state consti

tutional grounds, but wholly on federal constitutional

grounds. Consequently, there can be no doubt that when

the Circuit Court ruled, in its judgment affirming the trial

court, that no denial of constitutional rights had been made

to appear, it was referring to the Federal and not the

State Constitution. The same is true of that court’s order

denying petitioners’ motion for review of judgment on

appeal when it denied same on the ground that it had duly

6

considered each ground for appeal when the case was before

it on appeal.

Respectfully submitted,

T hubgood M arshall

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, N. Y.

Constance B akes M otley

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, N. Y.

F rancisco A. R odriguez

703 Harrison Street

Tampa, Florida

Certificate of Service

This is to certify that on the 12 day of March 1958 I

served a copy of Petitioners’ Supplemental Brief in the

above-entitled case upon Leo Foster, counsel for respon

dent, by mailing a copy of same to him at P. 0. Box 669,

Tallahassee, Florida, via United States Air Mail.

Constance B aker M otley

Attorney for Petitioners