Buck v Davis Brief for Petitioner

Public Court Documents

July 28, 2016

112 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Buck v Davis Brief for Petitioner, 2016. 04441407-b79a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/6e8f02d3-09f0-4247-a464-eaf193a02924/buck-v-davis-brief-for-petitioner. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

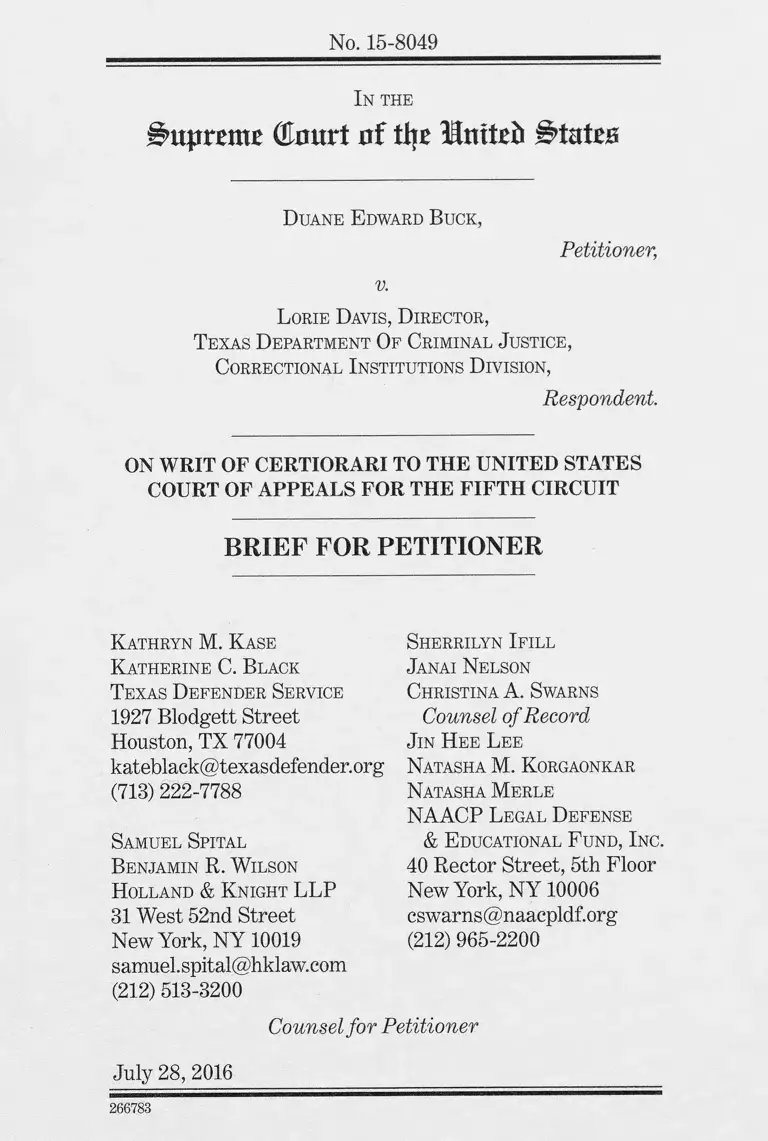

No. 15-8049

In the

Supreme (Enurt of the United Status

Duane E dward Buck,

Petitioner,

v.

L orie Davis, Director,

Texas D epartment Of Criminal Justice,

Correctional Institutions D ivision,

Respondent.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES

COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF FOR PETITIONER

Kathryn M. K ase

Katherine C. Black

Texas Defender Service

1927 Blodgett Street

Houston, TX 77004

kateblack@texasdefender.org

(713) 222-7788

Samuel Spital

Benjamin R. W ilson

Holland & K night LLP

31 West 52nd Street

New York, N Y 10019

samuel.spital@hklaw.com

(212) 513-3200

Sherrilyn Ifill

Janai Nelson

Christina A. Swarns

Counsel of Record

Jin Hee L ee

Natasha M. Korgaonkar

Natasha M erle

NAACP Legal Defense

& E ducational F und, Inc.

40 Rector Street, 5th Floor

New York, N Y 10006

cswarns@naacpldf.org

(212) 965-2200

Counsel for Petitioner

July 28, 2016

266783

mailto:kateblack@texasdefender.org

mailto:samuel.spital@hklaw.com

mailto:cswarns@naacpldf.org

QUESTION PRESENTED

Duane Buck’s death penalty case raises a pressing

issue of national importance: whether and to what extent

the criminal justice system tolerates racial bias and

discrimination. Specifically, did the United States Court

of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit impose an improper and

unduly burdensome Certificate of Appealability (COA)

standard that contravenes this Court’s precedent and

deepens two circuit splits when it denied Mr. Buck a

COA on his motion to reopen the judgment and obtain

merits review of his claim that his trial counsel was

constitutionally ineffective for knowingly presenting an

“expert” who testified that Mr. Buck was more likely to

be dangerous in the future because he is Black, where

future dangerousness was both a prerequisite for a death

sentence and the central issue at sentencing?

TABLE OF CONTENTS

QUESTION P R E S E N T E D ..................................................i

TABLE OF A U T H O R IT IE S............................................. vi

OPINIONS BELOW .................................................................1

JURISDICTION....................................................................... 1

R E L E V A N T C O N S T IT U T IO N A L A N D

STATUTORY PROVISIONS...........................................1

STATEMENT OF THE C A S E .......................................... 3

I. Introduction...................................................................3

II. The Capital Trial Proceedings................................4

III. Post-Conviction Proceedings....................................9

A. Mr. Buck’s Initial State Habeas Petition . . .9

B. Texas Concedes Error..................................... 10

C. Subsequent State Habeas Proceedings. . .13

D. Federal Habeas Proceedings.......................13

E. M r. B uck ’s 2013 State H abeas

Application and the Trevino Decision . . . . 16

Page

I l l

Table of Contents

F. Mr. Buck’s Post-Trevino Federal

Habeas Proceedings.................................... 18

SUMMARY OF THE ARGUMENT............................ 22

ARGUMENT............... 23

I. Trial Counsel Rendered Ineffective

Assistance by Presenting an “ Expert”

Opinion that Mr. Buck Is More Likely

to be Dangerous in the Future Because

He Is Black.............................................. .24

A. The District Court Correctly Recognized

that Counsel Performed Deficiently

by Knowingly Exposing Mr. Buck to

the Risks of Racial Prejudice..................... 26

B. The District Court Erred by Concluding

that Mr. Buck Was Not Prejudiced by

His Trial Counsel’s Constitutionally

Deficient Performance..................................33

1. Dr. Quijano’s Race-as-Dangerous

Opinion Was Highly Prejudicial...........34

2. The Facts of the Crime Do Not

Eclipse the Prejudice Caused by

Counsel’s Recklessly Exposing Mr.

Buck to Racial Bias............................... 39

Page

IV

Table of Contents

II. Mr. Buck is Entitled to a COA Because

Jurists of Reason Would Find the District

Court’s Ruling on Mr. Buck’s 60(b)(6)

Motion Debatable or Wrong.................................... 44

A. Requirem ents for R elief Under

Rule 60(b)(6)........................................................45

B. Mr. Buck’s Case Is Extraordinary

Within the Meaning of Rule 60(b)(6)............47

1. The Risk of Injustice to Mr. Buck . . . .47

2. The R isk of U n d erm in in g

Public Confidence in the Justice

System and the Risk of Injustice

in Other C ases...........................................49

3. The Probable Merit of Mr. Buck’s

Ineffectiveness C laim ..............................51

4. Texas’s Interest in Finality.................. 52

5. Mr. Buck’s Diligence................................53

6. Conclusion................................................... 54

C. Reasonable Jurists Could Conclude

that the Lower Courts’ Denial of Mr.

Buck’s Application for Rule 60(b)(6)

Relief Was Debatable or Wrong.................... 54

Page

V

Table of Contents

Page

CONCLUSION........................................... .................. 59

APPENDIX A ............................................................... la

VI

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

CASES:

Ackermann v. United States,

340 U.S. 193 (1950)........................................................... 46

Agostini v. Felton,

521 U.S. 203 (1997)...........................................................56

Alba v. Johnson,

No. 00-40194, 2000 W L 1272983

(5th Cir. Aug. 21, 2 0 0 0 )............................................ .... .12

Albermarle Paper Co. v. Moody,

422 U.S. 405 (1975)............................................................ 54

Allison v. State,

248 S.W.2d 147 (Tex. Crim. App. 1952)...................... 34

Bobby v. Van Hook,

558 U.S. 4 (2009)................................................................ 27

Bruton v. United States,

391 U.S. 123 (1968)............................................................34

Bryant v. State,

25 S.W.3d 924 (Tex. Ct, App. 2000).............................38

Buck v. Thaler,

132 S. Ct. 1085(2012)........................................... 15

Page(s)

Vll

Buck v. Thaler,

132 S. Ct. 32 (2011)............................................passim

Buck v. Thaler,

132 S. Ct. 69(2011).................................................... 15

Buck v. Thaler,

345 F. App’x 923 (5th Cir. 2009)....................15,16, 30

Buckv. Thaler,

452 F. App’x 423 (5th Cir. 2011).............................. 15

Buck v. Thaler,

559 U.S. 1072(2010)..........................................15

Cofield v. State,

82 S.E. 355 (Ga. Ct. App. 1914)................................. 37

Coleman v. Thompson,

501 U.S. 722 (1991).................................... ................ 15

Cooler & Cell v. Hartmax Corp.,

496 U.S. 384 (1990)..................................................... 54

Cox v. Horn,

757 F.3d 113 (3d Cir. 2014)......................................... 58

Davis v. Ayala,

135 S. Ct. 2187(2015)........................................... 50, 57

Page(s)

m n

Derrick v. State,

272 S.W. 458 (1925)..................................................... 25, 37

Detrich v. Ryan,

740 F.3d 1237 (9th Cir. 2013).......................................... 46

Dewberry v. State,

4 S.W.3d 735 (Tex. Crim. App. 1999)...........................41

Dinklage v. State,

185 S.W.2d 573 (Tex. Crim. App. 1945)...................... 37

Ex parte Buck,

418 S.W.3d 98 (Tex. Crim. App. 2013),

cert, denied, 134 S. Ct. 2663 (2014)............. .... 9,17, 48

Ex parte Medina,

361 S.W.3d 633 (Tex. Crim. App. 2011)........................ 9

Ex parte Williams,

No. AP-76455, 2012 W L 2130951

(Tex. Crim. App. June 3, 2012)......................................42

Flores v. Johnson,

210 F.3d 456 (5th Cir. 2000)............................................ 35

Gardner v. Johnson,

247 F.3d 551 (5th Cir. 2001)

Page(s)

40-41

IX

Gideon v. Wainwright,

372U.S.335 (1963)........................ ................ . . . . .5 6

Godfrey v. Georgia,

496 U.S. 420 (1980)......................................................28

Gonzalez v. Crosby,

545 U.S. 524 (2005)...........................................passim

Harrington v. Richter,

562 U.S. 86 (2011)........................................................33

Hazel-Atlas Glass Co. v. Hartford-Empire Co.,

322 U.S. 238 (1944)................................. 45

Hinton v. Alabama,,

134 S. Ct. 1081 (2014).......... .....................................28

In re Murchison,

349 U.S. 133 (1955).....................................................51

Irwin v. Dowd,

366 U.S. 717 (1961)...................................................... 36

JEB v. Alabama ex rel, T.B.,

511 U.S. 127 (1994)............................................... 49, 50

Johnson v. Rose,

546 F.2d 678 (6th Cir. 1976)...................................... 38

Page(s)

X

Page(s)

Jordan v. Fisher,

135 S. Ct. 2647 (2015).....................................................21

Kelly v. State,

824 S.W.2d 568 (Tex. Crim. App. 1992)...................... 18

Klapprott v. United States,

335 U.S. 601 (1949)......... ................................... 45, 55, 56

Kyles v. Whitley,

514 U.S. 419 (1995).......................................................... 44

Liljeberg v. Health Sews. Acquisition Corp.,

486 U.S. 847 (1988)........................................46-47, 51, 54

Louisiana v. Bessa,

38 So. 985 (La. 1905)......................................................37

Mackey v. United States,

401 U.S. 667 (1971)............................................................ 53

Martinez v. Ryan,

132 S. Ct. 1309 (2012).........................................passim

McCleskey v. Kemp,

481 U.S. 279 (1987)............................................................50

Miller-El v. Cockrell,

537 U.S. 322 (2003).............................................passim

XI

Miller-El v Dretke,

545 U.S. 231 (2005)....................................... 28, 39, 50

Murray v. Carrier,

477 U.S. 478 (1986)..................................................... 52

North Carolina v. Parker,

315 N.C. 249 (1985)......................................................42

Parker v. Gladden,

385 U.S. 363 (1966)......................................................44

Plant v. Spendthrift, Farm, Inc.,

514 U.S. 211 (1995)......................................................45

Porter v. Att’y Gen.,

552 F.3d 1260 (11th Cir. 2008)................................... 39

Porter v. McCollum,

558 U.S. 30 (2009)................................................. 39, 40

Powell v. Alabama,

287 U.S. 45(1932)............................ ................ . .27

Powers v. Ohio,

499 U.S. 400 (1991)................... 34,49

Ramirez v. United States,

799 F.3d 845 (7th Cir. 2015).......................... .55, 58

Page(s)

xii

Reed v. Ross,

468 U.S. 1 (1984)................................................................. 52

Reed v. State,

99 So. 2d 455 (Miss. 1958)...............................................37

Romano v. Oklahoma,

512 U.S. 1 ( 1 9 9 4 ) . . . . . ......................................................28

Roper v. Weaver,

550 U.S. 598 (2 0 0 7 )................................................... 49, 56

Saldaho v. State,

70 S.W.3d 873 (Tex. Crim. App. 2002).........................10

Saldaho v. Texas,

530 U.S. 1212(2000)...........................................................10

Satterwhite v. Texas,

486 U.S. 249 (1988)..................................................... 35, 40

Sears v. Upton,

561 U.S. 945 (2010).............................................................40

Slack v. McDaniel,

529 U.S. 529 (2000).............................................. .23-24

Strauder v. West Virginia,

100 U.S. 303 (1880)............................................................ 28

Page(s)

Xlll

Strickland v. Washington,

466 U.S. 668 (1984)............................................. passim

Taylor v. Kentucky,

436 U.S. 478 (1978)............................................. .34

Texas Emp’rs Ins. Ass’n v. Guerrero,

800 S.W.2d 859 (Tex. App. 1990)........ ..................... 38

Trevino v. Thaler,

133 S. Ct. 1911 (2013)........ ............................... passim

Turner v. Murray,

476 U.S. 28 (1986)............................................... passim

United States v. Cruz,

981 F.2d 659 (2d Cir. 1992)................... 34, 38

United States v. Garza,

608 F.2d 659 (5th Cir. 1979)................... .................. 36

United States v. Haynes,

466 F.2d 1260 (5th Cir. 1972)....................................38

United States v. Webster,

162 F.3d 308 (5th Cir. 1998)....................................... 48

Walbey v. Quaterman,

309 F. App’x 765 (5th Cir. 2009)............................ .40

Page(s)

XIV

Welch v. United States,

136 S. Ct. 1257(2016)......................................................53

Wiggins v. Smith,

539 U.S. 510(2003)............................................................ 33

Williams v. Taylor,

529 U.S. 362 (2000)............................................................ 40

Zant v. Stephens,

462 U.S. 862 (1983)............................................................ 28

CONSTITUTIONAL PROVISIONS:

U.S. Const, amend. V I .................................................26, 53

STATUTES:

28 U.S.C.

§ 2253(c)(2)................... .24

§ 2254(d)(1)..........................................................................40

RULES:

Fed. R. Civ. R 60(b)(6)................................................ passim

Tex. Code Crim. Proc. Ann. art. 37.071 § 2

(West 2013)............................................................................5

Tex. R. Evid. 705(c)................................................................. 18

Page(s)

XV

OTH ER AUTHORITIES:

ABA: Guidelines fo r the Appointment and.

Performance of Counsel in Death Penalty

Cases, Am erican Bar Association (1989),

available at http://www.americanbar.org/

content/dam/aba/migrated/2011_build/death_

penalty_representation /1989guidelines.

authcheckdam.pdf............................ ......................... 46

Eberhardt, Jennifer L., et al., Looking Deathworthy:

Perceived Stereotypicality of Black Defendants

Predicts Capital Sentencing Outcomes 384

(Cornell L. Fac. Publ’ns 2006), available at http://

scholarship.law.cornell.edu/cgi/viewcontent.

cgi?article=1040&context=lsrp_papers................. .50

Kimberly, James, Death Penalties of 6 in Jeopardy:

Attorney General Gives Result of Probe into

Race Testimony, Hou. Chron., June 10, 2000,

at A l, available at https://advance.lexis.

com/api/permalink/0147fb80-a512-4a2b-88ff-

9a6f07fl84d9/?context=1000516;..................... .11

Liptak, Adam, A Law yer Known Best fo r

Losing Capital Cases, N.Y. Times, May 17,

2010, available at www.nytimes.com/2010/

05/18/us/18bar.html.......................................................5

Page(s)

http://www.americanbar.org/

https://advance.lexis

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/

XVI

Page(s)

Monahan, J., et al., Rethinking R isk A ssessment:

T he MacA rthur Study of M ental D isorder

and Violence, Oxford Univ. Press (2001)..................5

Swanson, J. W., et al., Violence and Psychiatric

Disorder in the Community: Evidence from

the Epidemiologic Catchment Area Surveys,

41 Hosp. & Comm. Psych., 761-770 (1990)..................5

11 W rig h t, C ., A . M iller , & M. K ane,

Federal P ractice and Procedure § 2857

(2d ed. 1995 and Supp. 2004)......................................47

Yardley, Jim, Racial Bias Found in Six More Capital

Cases, N.Y. T imes, June 10, 2000, available at

http://www.nytimes.eom/2000/06/ll/us/racial-

bias-found-in-six-more-capital-cases.html. . . . 11

http://www.nytimes.eom/2000/06/ll/us/racial-bias-found-in-six-more-capital-cases.html

http://www.nytimes.eom/2000/06/ll/us/racial-bias-found-in-six-more-capital-cases.html

1

OPINIONS BELOW

The November 6,2015 opinion of the Court of Appeals

denying rehearing en banc (Joint Appendix (“JA”) 288a) is

available at 2015 W L 6874749 (5th Cir. Nov. 6, 2015). The

August 20, 2015 panel opinion of the Court of Appeals

denying Mr. Buck a COA (JA 274a) is reported at 623

F. App’x 668. The March 11, 2015 Order of the United

States District Court for the Southern District of Texas

denying Mr. Buck’s motion to alter or amend that Court’s

prior judgment (JA 269a) is unreported. The August

29, 2014 Memorandum and Order of the United States

District Court for the Southern District of Texas denying

Mr. Buck’s motion for relief from judgment pursuant

to Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 60(b) (JA 249a) is

unreported. The July 24,2006 Memorandum and Order of

the United States District Court for the Southern District

of Texas denying Mr. Buck’s Petition for Writ of Habeas

Corpus (JA 219a) is unreported.

JURISDICTION

The Court of Appeals entered its judgment on

November 6, 2015. This Court has jurisdiction under 28

U.S.C. § 1254(1).

RELEVANT CONSTITUTIONAL

AND STATUTORY PROVISIONS

This case involves a state criminal defendant’s

constitutional rights under the Sixth, Eighth, and

Fourteenth Amendments. The Sixth Amendment provides

in relevant part:

2

In all criminal prosecutions, the accused shall

enjoy the right to . . . have the assistance of

counsel for his defense.

The Eighth Amendment provides:

Excessive bail shall not be required, nor

excessive fines imposed, nor cruel and unusual

punishments inflicted.

The Fourteenth Amendment provides in relevant part:

[N]or shall any State . . . deny to any person

within its jurisdiction the equal protection of

the laws.

This case also involves the application of 28 U.S.C.

§ 2253(c), which states:

(1) Unless a circuit justice or judge issues a

certificate of appealability, an appeal may not

be taken to the court of appeals from

(A) the final order in a habeas corpus

proceeding in which the detention complained

of arises out of process issued by a State court;

(2) A certificate of appealability may issue

under paragraph (1) only if the applicant has

made a substantial showing of the denial of a

constitutional right.

3

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

I. Introduction

This is an extraordinary case. Duane Buck is a

Black man whose own attorneys presented an “expert”

opinion that he is more likely to commit future acts of

violence— and was therefore more deserving of a death

sentence under Texas law— because of his race. The

State of Texas conceded that this race-as-dangerousness

testimony is constitutionally prohibited and undermines

public confidence in the criminal justice system. Texas

subsequently promised that it would not oppose new

sentencing hearings in seven capital cases— including Mr.

Buck’s— that were corrupted by race-as-dangerousness

testimony from the same expert. Texas kept its promise

in six of those cases, but reneged on its promise to Mr.

Buck alone. When Mr. Buck filed his federal habeas

petition raising, inter alia, an ineffective assistance of

counsel (“IAC”) claim that challenged his trial counsel’s

presentation of the race-as-dangerousness “expert”

opinion, Texas successfully argued that the claim was

procedurally defaulted because Mr. Buck’s state habeas

counsel failed to raise the claim in a timely manner.

Intervening precedent from this Court establishes

that the procedural default urged by Texas, and accepted

by the District Court when it denied Mr. Buck’s habeas

petition, no longer prevents merits review of Mr. Buck’s

IAC claim. Yet, when Mr. Buck sought to reopen the

judgment based on the confluence of circumstances that

render his case extraordinary, the lower courts improperly

denied relief and concluded that Mr. Buck was not even

able to satisfy the threshold showing necessary for a

4

Certificate of Appealability (“COA”). As a result, a death

sentence tainted by egregious racial bias remains intact,

and the legitimacy of our criminal justice system has been

seriously undermined.

II. The Capital Trial Proceedings

In 1996, Mr. Buck was charged with capital murder

in connection with the shooting deaths of Debra Gardner

and Kenneth Butler. The evidence at trial showed that

in the early morning hours of July 30, 1995, Mr. Butler,

his brother Harold Ebnezer, Mr. Buck’s step-sister

Phyllis Taylor, and Debra Gardner were gathered at

Ms. Gardner’s home. Mr. Buck had been in a romantic

relationship with Ms. Gardner that ended two or three

weeks earlier. Mr. Buck forced his way into the home,

argued with and struck Ms. Gardner, stated that he was

there to pick up his clothes, retrieved a few items, and

then left. JA 250a-251a. Believing Ms. Gardner was

sleeping with Mr. Butler, JA 251a, Mr. Buck returned to

the home a few hours later with a rifle and a shotgun. He

attempted to shoot Mr. Ebnezer but missed. Mr. Buck then

shot Ms. Taylor and Mr. Butler. Ms. Gardner fled into the

street. Mr. Buck followed, and shot her while her children

were watching. Ms. Taylor survived but Mr. Butler and

Ms. Gardner died from their wounds. JA 251a-252a. A

police officer testified that after Mr. Buck was arrested

at the scene, he laughed and stated, “The bitch deserved

what she got.” JA 252a, 262a.

A t trial, Mr. Buck was represented by court-

appointed counsel, Danny E asterling and Jerry

Guerinot. Mr. Guerinot’s history of providing inadequate

representation to capitally charged clients is well

5

documented: “ Twenty of Mr. Guerinot’s clients [were]

sentenced to death.” Adam Liptak, A Lawyer Known

Best for Losing Capital Cases, N.Y. Times, May 17, 2010,

available at www.nytimes.com/2010/05/18/us/18bar.

html.

Prior to trial, Mr. Buck’s counsel received a report

from Dr. Walter Quijano, one of two psychologists retained

by the defense, to assess, inter alia, whether Mr. Buck was

likely to commit criminal acts of violence in the future.

“Future dangerousness” is one of the “special issues” that

a Texas jury must find to exist— unanimously and beyond

a reasonable doubt— before a defendant may be sentenced

to death. See Tex. Code Crim. Proc. art. 37.071 § 2 (West

2013). In his report, Dr. Quijano opined that being “Black”

was a “statistical factor” that “Increased [the] probability”

Mr. Buck would commit future acts of criminal violence.

JA 18a-19a, 35a-36a; see Buck v. Thaler, 132 S. Ct. 32,33

(2011) (Statement of Alito, J.). This purported link between

race and future dangerousness had been discredited well

before Mr. Buck’s trial.1

Future dangerousness was the central disputed

issue at the sentencing phase of Mr. Buck’s trial. In

an effort to make its case, the prosecution emphasized

the facts of the capital crime and called Mr. Buck’s

ex-girlfriend, Vivian Jackson, to testify that Mr. Buck

1 See J. W. Swanson et al., Violence and Psychiatric Disorder

in the Community: Evidence from the Epidemiologic Catchment

Area Surveys, 41 Hosp. & Comm. Psych., 761-70 (1990) (when

controlling for socioeconomic status, correlations between race

and violence disappear); see also J. Monahan et. ah, Rethinking

R isk A ssessment: T he MacA rthur Study of Mental D isorder

and Violence, Oxford Univ. Press (2001) (same).

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/05/18/us/18bar

6

abused her, especially at the end of their relationship. JA

125a-127a. The prosecution presented no evidence that

Mr. Buck had been violent outside the context of romantic

relationships. Indeed, although the prosecution submitted

records demonstrating that Mr. Buck had previously been

convicted of delivery of cocaine and unlawfully carrying

a weapon, JA 185a; Tr. 5-28, Buck v. Stephens, No. 4:04-

cv-03965 (S.D. Tex. June 24, 2005), ECF No. 5-111, pp.

17-40, none of Mr. Buck’s prior convictions were for crimes

of violence.

The defense presented testimony from Mr. Buck’s

father James Buck, his stepmother Sharon Buck, his

sister Monique Winn, and Reverend J. C. Neal. Tr. 76-79,

Buck, No. 4:04-cv-03965 (S.D. Tex. June 24, 2005), ECF

No. 5-113, pp. 9-12. These witnesses, who had known

Mr. Buck most, if not all, of his life, testified that they

had never known Mr. Buck to be violent. In addition, the

defense presented the testimony of psychologist Patrick

Lawrence. Dr. Lawrence had previously appeared on

behalf of both the prosecution and defense in Texas

courts, and, over the prior 25 years, evaluated roughly

900 prisoners convicted of homicide. See Tr. 177,182-186,

188-204, 205-06, id. at ECF Nos. 5-115, pp. 34, 39-41;

5-116, pp. 5-21.

Dr. Lawrence testified that Mr. Buck was not likely

to be dangerous in the future. JA 193a, 223a. He based

his opinion on, inter alia, the undisputed facts that:

Mr. Buck was unlikely to develop a romantic relationship

with a woman in prison, and Mr. Buck’s records showed

he “did not present any problems in the prison setting”

and, indeed, had been held in minimum security custody.

See Tr. 196, Buck, No. 4:04-cv-03965 (S.D. Tex. June

7

24, 2005), ECF No. 5-116, p. 13. Dr. Lawrence also

testified that intellectual testing revealed Mr. Buck has

an IQ of 75, “which suggests that he functions within the

borderline intellectual range of the population at about

the 4 percentile.” Tr. 189, id. at p. 6.

Despite the absence of evidence suggesting that

Mr. Buck was likely to be dangerous outside of the

context of a domestic relationship with a woman, defense

counsel also presented Dr. Quijano’s “expert” opinion

that Mr. Buck was more likely to commit future crimes of

violence because he is Black. Even though Dr. Quijano’s

report identified Mr. Buck’s “race” as a “statistical

factor” that increased his probability of being a future

danger, defense counsel specifically asked Dr. Quijano to

recount the “statistical factors or environmental factors”

relevant to assessing the future dangerousness of a

person “such as Mr. Buck.” JA 145a-146a. Dr. Quijano’s

response tracked his report. He testified that “race” was

among the “statistical factors he considered in deciding

whether a person will or will not constitute a continued

danger” because “ [ijt’s a sad commentary that minorities,

Hispanics and black people, are over represented in the

Criminal Justice System.” JA 146a.

On cross-examination, the trial prosecutor exploited

defense counsel’s introduction of Dr. Quijano’s race-as-

dangerousness testimony:

Q: You have determined that the sex factor, that

a male is more violent than a female because

that’s just the way it is, and that the race factor,

black, increases the future dangerousness for

various complicated reasons; is that correct?

A: Yes.

JA 170a.

At defense counsel’s request, and over the prosecution’s

objection, Dr. Quijano’s report detailing his opinion (“Race.

Black. Increased probability” of future dangerousness)

was admitted into evidence and made available to the jury

during deliberations. JA 151a-152a.

Future dangerousness was the focus of both the

prosecution’s and the defense’s closing arguments. JA

187a-196a (defense closing); JA 196a-206a (prosecution

closing). Indeed, the lead prosecutor urged the jury to

rely on Mr. Buck’s own expert to find that he was likely to

be dangerous in the future: “You heard from Dr. Quijano,

who had a lot of experience in the Texas Department of

Corrections, who told you that there was a probability that

[Mr. Buck] would commit future acts of violence.” JA 198a.

The jury deliberated over the course of two days,

during which time they sent out four notes seeking further

instruction, as well as the opportunity to review, inter alia,

Dr. Quijano’s report. JA 209a. The jury ultimately found

that Mr. Buck was likely to be a future danger, and he

was sentenced to death. Mr. Buck’s conviction and death

sentence were affirmed on direct appeal. Buck v. State,

No. 72,810 (Tex. Crim. App. 1999) (unpublished).

9

III. Post-Conviction Proceedings

A. Mr. Buck’s Initial State Habeas Petition

In March of 1999, Mi'. Buck’s newly appointed counsel,

Robin Norris, filed his initial state habeas application.

Like Mr. Buck’s trial counsel, Mr. Norris has a troubling

pattern of deficient representation of death-sentenced

prisoners. In another capital case, the Texas Court of

Criminal Appeals (“CCA”) found that Mr. Norris threw

his client “under the bus” by filing an initial state habeas

application that was “only four pages long and merely

statefd] factual and legal conclusions.” Ex parte Medina,

361 S.W.3d 633, 635-36 (Tex. Grim. App. 2011). His

representation of Mr. Buck was characterized by similar

deficiencies.

As explained by three Judges of the CCA, Mr.

Norris “filed only non-cognizable or frivolous claims in

[Mr. Buck’s] initial application.” Ex parte Buck, 418 S.W.3d

98,107 (Tex. Grim. App. 2013) (Alcala, J., joined by Price

and Johnson, JJ.), cert, denied, 134 S. Ct. 2663 (2014).

“ [Tjhree of the four claims . . . were raised and rejected

on direct appeal and, therefore, under the longstanding

precedent of [the CCA], those claims were not cognizable

on a post-conviction writ of habeas corpus.” Id. at 102. The

fourth claim was “wholly frivolous” because it asserted

that “ [Mr. Buck’s] trial counsel [were] ineffective for

failing to request a jury instruction based on a non

existent provision of the penal code.” Id. Mr. Norris failed

to challenge trial counsel’s introduction of Dr. Quijano’s

“expert” opinion that Mr. Buck’s race increased his

likelihood of committing future acts of criminal violence.

10

B. Texas Concedes Error.

One year after the filing of Mr. Buck’s state habeas

application, another capital case involving Dr. Quijano’s

race-as-dangerousness opinion reached this Court.

In Saldano v. Texas, No. 99-8119, Dr. Quijano served

as a prosecution witness and offered his “expert”

opinion that a defendant’s race or ethnicity is one of

the “identifying markers” that increases the likelihood

of future dangerousness. Saldano v. State, 70 S.W.Sd

873, 884-85 (Tex. Crim. App. 2002). After the CCA

affirmed Mr. Saldano’s conviction and sentence, he filed a

certiorari petition asking this Court to decide “[wjhether

a defendant’s race or ethnic background may ever be used

as an aggravating circumstance in the punishment phase

of a capital murder trial in which the State seeks the death

penalty.” Saldano, 70 S.W.Sd at 875.

Speaking through then-Attorney General John

Cornyn, Texas conceded error. In its response to the

petition, Texas acknowledged that the “infusion of race as

a factor for the jury to weigh in making its determination

violated [Mr. Saldano’s] constitutional right to be sentenced

without regard to the color of his skin.” JA 306a. Texas

further recognized that “‘[d]iscrimination on the basis of

race, odious in all aspects, is especially pernicious in the

administration of justice,”’ and that “the use of race in

Saldano’s sentencing seriously undermined the fairness,

integrity, or public reputation of the judicial process.” JA

304a-305a. On June 5,2000, this Court granted certiorari,

vacated the CCA’s judgment, and remanded for further

consideration in light of Texas’s concession. Saldano v.

Texas, 530 U.S. 1212 (2000).

11

Four days later, then-Attorney General Cornyn issued

a press release stating that his office had conducted “a

thorough audit of cases” and identified six other capital

cases involving Dr. Quijano’s testimony that “are similar

to that of Victor Hugo Saldano.” JA 213a. The prisoners

in those cases were: Gustavo Garcia, Eugene Broxton,

John Alba, Michael Gonzales, Carl Blue, and Duane Buck.

JA 215a-217a. The Attorney General did not distinguish

between the cases in which Dr. Quijano was called by

the prosecution or the defense. Indeed, in three of the

cases identified by the Attorney General (Mr. Broxton’s,

Mr. Gonzales’s, and Mr. Garcia’s), the prosecution called

Dr. Quijano; in the three other cases (Mr. Alba's, Mr.

Blue’s, and Mr. Buck’s), Dr. Quijano was a defense

witness. JA 215a. The Attorney General stressed that “ it

is inappropriate to allow race to be considered as a factor

in our criminal justice system,” and that the “people of

Texas want and deserve a system that affords the same

fairness to everyone.” JA 213a-214a.

In a separate statement to the media, the Attorney

General’s spokesperson announced that Texas would

not oppose federal habeas claims for relief based on

Dr. Quijano’s unconstitutional, race-based testimony in

any of the similar-to-SaMcmo cases;2 acknowledged that

2 James Kimberly, Death Penalties of 6 in Jeopardy:

Attorney General Gives Result of Probe into Race Testimony,

Hou. Chron., June 10, 2000, at Al, available at https://advance.

Iexis.com/api/permalink/0147fb80-a512-4a2b-88ff-9a6f07fl84d9/

?context=1000516; Jim Yardley, Racial Bias Found in Six More

Capital Cases, N.Y. T imes, June 10,2000, available at http://www.

nytimes.com/2000/06/ll/us/racial-bias-found-in-six-more-capital-

cases.html. Thus, contrary to the Fifth Circuit’s suggestion, see

JA 277a, the record makes clear that Texas promised to treat Mr.

https://advance

http://www

12

some of the six cases might still be in state court (where

the Attorney General is not responsible for litigating on

the State’s behalf); and promised that, if and when those

cases reached the Attorney General’s Office, they “will

be handled in a similar manner as the Saldano case.” JA

281. At the time, only one of the six similar-to-Saldano

cases was still pending in state court: Mr. Buck’s case.3

Prior to the Attorney General’s admission of error,

none of the six identified defendants had challenged the

constitutionality of Dr. Quijano’s testimony. Nonetheless,

Texas kept its promise, waived all procedural defenses,

conceded constitutional error, and agreed that a new

sentencing hearing was required in each case except Mr.

Buck’s.4

Buck’s case similarly to Saldano, i.e., a case in which it conceded

error based on Dr. Quijano’s testimony in federal habeas. Mr.

Buck’s Rule 60(b) motion pled these facts, thus any material

factual disputes about the details of Texas’s promise are properly

addressed at an evidentiary hearing.

3 See Opinion and Order at 3, Blue v. Johnson, No. 4:99-cv-

00350 (S.D. Tex. Sept. 29, 2000), ECF No. 29; Order at 1, Alba

v. Johnson, No. 4:98-cv-221 (E.D. Tex. Sept. 25, 2000), ECF No.

31; Order at 1, Garcia v. Johnson, No. l:99-cv-00134 (E.D. Tex.

Sept. 7, 2000), ECF No. 36; Order at 3, Broxton v. Johnson, No.

H-00-CV-1034, ECF No. 25; Order at 11, Gonzales v. Cockrell, No.

7:99-ev-00072 (W.D. Tex. Dec. 19, 2002), ECF No. 84.

4 See Opinion and Order at 15-17, Blue v. Johnson, No. 4:99-

cv-00350 (S.D. Tex. Sept. 29,2000), ECF No. 29; Alba v. Johnson,

No. 00-40194, 2000 WL 1272983, at *1 (5th Cir. Aug. 21, 2000);

Order at 1, Alba v. Johnson, No. 4:98-cv-221 (E.D. Tex. Sept. 25,

2000), ECF No. 31; Order at 1, Garcia v. Johnson, No. l:99-cv-

00134 (E.D. Tex. Sept. 7, 2000), ECF No. 36; Resp. to Suppl. Pet.

and Confession of Error by TDCJ-ID, Garcia, No. l:99-cv-00134

13

C. Subsequent State Habeas Proceedings

In 2002— two years after the Texas Attorney

General’s public statements regarding the similar-to-

Saldano cases— Mr. Norris filed a subsequent application

for state habeas relief where he challenged, for the

first time, trial counsel’s introduction of Dr. Quijano’s

opinion that Mr. Buck was more likely to be a future

danger because he is Black. Subsequent Appl. for Writ of

Habeas Corpus, Ex -parte Buck, No. WR-57,004-02 (Tex.

Crim. App. Oct. 15, 2003), ECF No. 5-152, pp. 6, 9. In a

consolidated order, the CCA dismissed the subsequent

application as an abuse of the writ without considering

the merits of Mr. Buck’s ineffectiveness claim, and denied

the non-eognizable and frivolous claims that Mr. Norris

presented in the initial (1999) application on their merits.

Order, Ex parte Buck, No. WR-57,004-02 (Tex. Crim. App.

Oct. 15, 2003) (unpublished).

D. Federal Habeas Proceedings

Represented by new counsel, Mr. Buck filed a federal

habeas corpus petition in October 2004, asserting, inter

alia, that Mr. Buck’s federal constitutional rights to equal

protection, due process, and the effective assistance of

counsel were violated by the introduction of “expert”

testimony and an “expert” report linking Mr. Buck’s race

to an increased likelihood of future dangerousness. Pet.

for Writ of Habeas Corpus at 55-62, Buck v. Cockrell, No.

(E.D. Tex. Aug. 18, 2000), ECF No. 35; Broxton v. Johnson, No.

H-0Q-CV-1034, 2001 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 25715, at *15 (S.D. Tex.

Mar. 28, 2001); Final J. at 1, Gonzales v. Cockrell, No. 7:99-cv-

00072 (W.D. Tex. Dec. 19, 2002), ECF No. 84.

14

04-03965 (S.D. Tex. Oet. 14, 2004), ECF No. 1. However,

despite Texas’s promise to concede constitutional error

in Mr. Buck’s case— a promise that Texas kept in all five

of the other similar-to-Saldano cases— Texas reversed

course and argued that federal review of Mr. Buck’s

ineffectiveness claim was foreclosed by state habeas

counsel’s default of that claim. In its answer to Mr. Buck’s

habeas petition, Texas stated:

This Court is no doubt aware that the Director

waived similar procedural bars and confessed

error in other cases involving testimony by

Dr. Quijano, most notably the case of Victor

Hugo Saldano (collectively referred to as

“the Salda?io cases”). This case, however,

presents a strikingly different scenario than

that presented in Saldano— Buck himself, not

the State offered Dr. Quijano’s testimony into

evidence. Based on this critical distinction, the

Director deems himself compelled to assert the

valid procedural bar precluding merits review

of Buck’s constitutional claims. And on this

basis, federal habeas relief should be denied.

Respondent Dretke’s Answer and Motion for Summ. J.

with Brief in Support at 17, Buck, No. 4:04-cv-03965 (S.D.

Tex. Sept. 6, 2005), ECF No. 7, p. 17 (citation omitted).

Texas further maintained that “the former actions of the

Director [in the other five cases] are not applicable and

should not be considered in deciding this case.” Id. at 20.

This account was highly misleading. Texas failed to

disclose that, as described: (1) after a “thorough audit,”

then-Texas Attorney General Cornyn identified Mr. Buck’s

15

case as “similar to that of Victor Hugo Saldano,” just like

the other five cases in which Texas waived procedural bars

and conceded error; and (2) in two of the other similar-

to-Saldano cases, Dr. Quijano was called as a defense

witness. JA 213a.

Because Texas reversed course in Mr. Buck’s case and

raised a procedural defense, the District Court denied

relief. Relying on Coleman v. Thompson, 501 U.S. 722

(1991), the court held that Mr. Buck’s Quijano-related

claims were procedurally defaulted because the state

court had dismissed them on an independent and adequate

state ground: state habeas counsel’s failure to timely raise

the claims. JA 237a-239a.

Between 2006 and 2012, Mr. Buck repeatedly sought

review of the District Court’s denial of his habeas petition.

See Buck v. Thaler, 345 F. App’x 923 (5th Cir. 2009)

(affirming denial of habeas relief and denying request

for COA); Buck v. Thaler, 559 U.S. 1072 (2010) (denying

certiorari); Buck v. Thaler, 452 F. App’x 423 (5th Cir.

2011) (denying stay of execution and motion for relief from

judgment); Buck v. Thaler, 132 S. Ct. 69 (2011) (denying

petition for writ of certiorari and motion for stay of

execution); Buck, 132 S. Ct. 32 (2011) (denying certiorari);

Buck v. Thaler, 132 S. Ct. 1085 (2012) (denying rehearing).

Mr. Buck did not seek further review of his IAC

claim because Coleman foreclosed it. Mr. Buck instead

challenged the prosecutor’s reiteration of Dr. Quijano’s

race-as-dangerousness opinion on cross-examination and

her reliance on Dr. Quijano’s testimony in closing argument

to urge the jury to find Mr. Buck a future danger. In

response, Texas consistently asserted that Mr. Buck’s trial

16

counsel— rather than the prosecution—was responsible

for placing Dr. Quijano’s false and inflammatory opinion

about race before the jury.5 The Court of Appeals agreed

with Texas. Buck, 345 F. App’x at 930.

In 2011, three Justices of this Court reached the

same conclusion. In a statement regarding the denial of

Mr. Buck’s petition for certiorari challenging the trial

prosecutor’s conduct, Justice Alito—joined by Justices

Scalia and Breyer— explained that responsibility for

the introduction of “bizarre and objectionable” expert

testimony linking Mr. Buck’s race to an increased

likelihood of future dangerousness “lay squarely with the

defense.” Buck, 132 S. Ct. at 33, 35.

E. Mr. Buck’s 2013 State Habeas Application and

the Trevino Decision

Mr. Buck filed a new state habeas application in

March 2013. Application for Post-Conviction Writ of

Habeas Corpus, Ex parte Buck, No. WR-57,004-03 (Tex.

Crim. App. Mar. 28, 2013). In that petition, Mr. Buck

challenged, inter alia, his trial counsel’s ineffective failure

to investigate, develop, and present available, mitigating

evidence, including Phyllis Taylor’s statement that on the

night of the shooting, Mr. Buck was “different from the

5 Respondent’s Answer at 17-18, 20, Buck v. Dretke, No.

04-03965 (S.D. Tex. Sept. 6, 2005), ECF No. 6; Thaler’s Reply to

Buck’s Mot. for Relief from J. and Mot. for Stay of Execution at 10,

16-17, 19-20, Buck v. Thaler, 04-03965 (S.D. Tex. Sept. 9, 2011),

ECF No. 30; Resp. in Opp’n to Appl. for Cert, of Appealability

at 22-25, 28-30, Buck v. Thaler, No. 11-70025 (5th Cir. Sept. 14,

2011), ECF No. 511602284; Br. in Opp’n at 12-13, 18-20, Buck v.

Thaler, Nos. 11-6391 & 11A297 (U.S. Sept. 15, 2011).

17

person [she] grew up with” due to his drug and alcohol

intoxication. Id. at 89. A sharply divided CCA dismissed

the application for “failing] to satisfy the requirements of

Article 11.071, § 5(a).” Ex parte Buck, 418 S.W.Sd 98. In her

dissenting opinion, Judge Alcala—-joined by Judges Price

and Johnson— explained that “ [Mr. Buck’s case] reveals a

chronicle of inadequate representation at every stage of

the proceedings, the integrity of which is further called

into question by the admission of racist and inflammatory

testimony from an expert witness at the punishment

phase.” Id. at 107.

While Mr. Buck’s application was pending before the

CCA, this Court created a new exception to the procedural

bar on which Texas successfully relied to prevent federal

habeas review of Mr. Buck’s IAC claim. Specifically, in

Trevino v. Thaler, 133 S. Ct. 1911 (2013), this Court held

that Martinez v. Ryan, 132 S. Ct. 1309 (2012), applied to

Texas. Martinez “ ‘modified] the unqualified statement

in Coleman that an attorney’s ignorance or inadvertence

in a postconviction proceeding does not qualify as cause

to excuse a procedural default.’” Trevino, 133 S. Ct. at

1917 (quoting Martinez, 132 S. Ct. at 1315). Martinez and

Trevino allow, for the first time, an opportunity for federal

review of defaulted IAC claims where (1) the IAC claim

is “substantial”; (2) there was no counsel or there was

ineffective counsel during the initial state post-conviction

review of the claim; and (3) state law effectively requires

ineffective assistance of trial counsel claims to be litigated

on initial collateral review. Trevino, 133 S. Ct. at 1918

(quoting Martinez, 132 S. Ct. at 1318-20). A “substantial”

claim is one that “has some merit.” Martinez, 132 S. Ct.

at 1318 (citing Miller-El v. Cockrell, 537 U.S. 322 (2003)

(describing standards for COA to issue)).

18

F. Mr. B u ck ’s P ost -Trevino Federal Habeas

Proceedings

On January 7,2014, immediately after the denial of the

pending state habeas application, Mr. Buck filed a motion

for relief from the District Court’s denial of the IAC

claim in his initial federal habeas petition. Rule 60(b)(6)

Motion, Buck, No. 04-03965 (S.D. Tex. Jan. 7,2014), ECF

No. 49. In this motion, Mr. Buck detailed the following

“extraordinary circumstances” justifying the reopening of

a final judgment under Rule 60(b)(6) of the Federal Rules

of Civil Procedure (“Rule 60(b)(6)” or “Rule 60(b)” ) and

Gonzalez v. Crosby, 545 U.S. 524, 535 (2005):

1. Mr. Buck’s trial attorney knowingly presented

expert testimony to the sentencing jury that

Mr. Buck’s race made him more likely to be a

future danger;

2. Although required to act as a gate-keeper

to prevent unreliable expert opinions from

reaching and influencing a jury, see Tex. R.

Evid. 705(c); Kelly v. State, 824 S.W.2d 568 (Tex.

Crim. App. 1992), the trial court qualified Dr.

Quijano as an expert on predictions of future

dangerousness, allowed him to present race-

based opinion testimony to Mr. Buck’s capital

sentencing jury, and admitted Dr. Quijano’s

excludable hearsay report linking race to

dangerousness;

3. The trial prosecutor intentionally elicited

Dr. Quijano’s testimony that Mr. Buck’s race

made him more likely to be a future danger

19

on cross-examination, vouched for him as an

“expert” in closing, and asked the jury to rely

on Dr. Quijano’s testimony to answer the future

dangerousness special issue in the State’s favor;

4. Mr. Buck’s state habeas counsel did not

challenge trial counsel’s introduction of this

false and offensive testimony— or Texas’s

reliance on it—in Mr. Buck’s initial state habeas

application;

5. The Texas Attorney General conceded

constitutional error in Mr. Buck’s case and

promised to ensure that he received a new

sentencing, but reneged on that promise after

deciding that the introduction of the offensive

testimony was trial counsel’s fault;

6. Th[e District] Court ruled that federal review

of Mr. Buck’s trial counsel ineffectiveness

claim was foreclosed by state habeas counsel’s

failure to raise and litigate the issue in Mr.

Buck’s initial state habeas petition, relying

on Cole-man, which has subsequently been

modified by Martinez and Trevino;

7. The Fifth Circuit held Mr. Buck’s trial

counsel responsible for the introduction of Dr.

Quijano’s testimony linking Mr. Buck’s race to

his likelihood of future dangerousness;

8. Three Supreme Court Justices concluded that

trial counsel was at fault for the introduction of

Dr. Quijano’s testimony;

20

9. Three judges of the CCA found that “because

[Mr. Buck’s] initial habeas counsel failed to

include any claims related to Dr. Quijano’s

testim ony in his original [state habeas]

application, no court, state or federal, has ever

considered the merits of those claims,” Buck,

2013 W L 6081001, at *5;

10. Mr. Buck’s case is the only one in which Texas

has broken its promise to waive procedural

defenses and concede error, leaving Mr. Buck

as the only individual in Texas facing execution

without having been afforded a fair and

unbiased sentencing hearing; and,

11. Martinez and Trevino now allow for federal

court review of “substantial” defaulted claims

of trial counsel ineffectiveness.

JA 283a-285a.

In adjudicating Mr. Buck’s Rule 60(b) motion, the

District Court recognized that trial counsel “recklessly

exposed [Mr. Buck] to the risks of racial prejudice and

introduced testimony that was contrary to [Mr. Buck’s]

interests.” JA 264a. Remarkably, however, the court

concluded that trial counsel’s introduction of an expert

opinion that Mr. Buck’s race made him more likely to

commit future acts of criminal violence— and thus more

deserving of a death sentence under Texas law— had only

a “de minimis” effect on Mr. Buck’s sentencing. JA 259a.

The court held that Mr. Buck was not entitled to reopen

the judgment because: (1) his case did not involve the

extraordinary circumstances required by Rule 60(b)(6);

and (2) in the alternative, Mr. Buck was not prejudiced by

21

his trial counsel’s constitutionally deficient performance.

JA 259a-260a, 271a-272a. The District Court further

determined that its rulings on these points were not

debatable among jurists of reason, and thus Mr. Buck was

not entitled to a COA. JA 264a-265a.

Without addressing the merits of Mr. Buck’s IAC

claim, the Fifth Circuit likewise denied a COA, declaring

that “ [Mr.] Buck has not made out even a minimal showing

that his case is exceptional,” within the meaning of

Rule 60(b). JA 283a. The Fifth Circuit insisted that Mr.

Buck’s IAC claim “is at least unremarkable as far as IAC

claims” and that Texas’s “broken-promise . . . makes [the

case] odd and factually unusual,” but not even debatably

extraordinary. JA 285a-286a.

Dissenting from the denial of en banc review, Judge

Dennis, joined by Judge Graves, concluded that Mr. Buck

was clearly entitled to a COA, and that the panel’s

contrary decision was consistent with the Fifth Circuit’s

“ ‘troubling’ habit” of applying an improper COA analysis.

JA 290a (quoting Jordan v. Fisher, 135 S. Ct. 2647, 2652

n.2 (2015) (Sotomayor, J., joined by Ginsburg and Kagan,

JJ., dissenting from the denial of certiorari). Judge

Dennis explained that the panel “ ‘dismisse[d], miscastf],

and minimize[d] [Mr. Buck’s] evidence, diluting its full

weight by disaggregating it and focusing the inquiry on

determining whether each isolated piece of evidence,

taken alone,’ proves extraordinary circumstances.” JA

292a. By contrast, a “proper, threshold inquiry into [Mr.]

Buck’s claim would have revealed that reasonable jurists

could disagree with the district court’s conclusions,”

because the factors presented by Mr. Buck “describe a

situation that is at least debatably ‘extraordinary.’” JA

293a-294a.

22

SUMMARY OF THE ARGUMENT

Mr. B uck’s tria l counsel rendered ineffective

assistance by knowingly presenting an expert opinion

that Mr. Buck was more likely to commit future acts

of violence because he is Black. That testimony was so

directly contrary to Mr. Buck’s interests, no competent

defense attorney would have introduced it.

Counsel’s constitutionally deficient performance

powerfully undermines confidence in Mr. Buck’s sentence

of death. For over a century, courts have recognized that

racially inflammatory statements presented during a

criminal trial create a constitutionally intolerable risk that

the jury will make its decision based on a quintessentially

arbitrary factor (race), instead of the relevant evidence.

These precedents apply a fortiori to Mr. Buck’s case

because Dr. Quijano’s race-as-dangerousness opinion:

(1) validated a uniquely pernicious stereotype; (2) was

presented by a purported “expert” for the defense; and (3)

was introduced at a capital sentencing hearing where the

principal issue for the jury to decide was whether Mr. Buck

was likely to be dangerous in the future. The prejudice to

Mr. Buck from the introduction of this “expert” opinion—

that Black men are predisposed to criminal violence— is

especially clear because the prosecution’s case in support

of future dangerousness was not overwhelming, and the

jury struggled to reach a decision.

Further, Texas’s ordinary interest in finality is

not compelling here because it promised not to rely on

procedural defenses in a number of cases, including Mr.

Buck’s, in order to preserve the integrity of the rule of

law, and then kept its promise in all of those cases except

23

Mr. Buck’s. The sui generis facts of this case (at, and

after, trial)— combined with Mr. Buck’s diligence and the

change in law worked by Trevino and Martinez— establish

the “extraordinary circumstances” required by Rule

60(b). The failure to reopen the District Court’s judgment

denying Mr. Buck’s Sixth Amendment claim creates

both a profound risk of injustice to Mr. Buck-—who faces

execution pursuant to a death sentence marred by racial

bias— and a profound risk of harm to society’s confidence

in the integrity of the criminal justice system.

Under any standard of review, the lower courts’

denial of Mr. Buck’s Rule 60(b) motion was erroneous.

The denial of a COA was even more improper. A COA

is required so long as reasonable jurists could find the

denial of relief debatable or the issues presented by the

petitioner adequate to proceed further. Mr. Buck surely

meets this threshold standard, and the Court of Appeals’

failure to grant a COA reflects its failures to properly

apply this Court’s precedent and to acknowledge the

plainly extraordinary circumstances of Mr. Buck’s case.

ARGUMENT

As this Court has stressed, a COA is required so long

as a habeas petitioner makes a “threshold” showing that

the District Court’s decision was “debatable amongst

jurists of reason.” Miller-El, 537 U.S. at 336. Thus, “ [a]

court of appeals should not decline the application for a

COA merely because it believes the applicant will not

demonstrate an entitlement to relief.” Id. at 337. Instead,

“a prisoner seeking a COA need only demonstrate ‘a

substantial showing’” that the district court erred in

denying relief. Id. at 327 (quoting Slack v. McDaniel,

24

529 U.S. 473, 474, 484 (2000) and 28 U.S.C. § 2253(c)(2)).

That standard is satisfied when reasonable jurists could

either disagree with the district court’s denial of relief,

or determine that “ the issues presented . . . deserve

encouragement to proceed further.” Miller-El, 537 U.S.

at 327, 336.

Thus, Mr. Buck is entitled to a COA so long as the

District Court’s decision denying his Rule 60(b) motion

was at least debatable among reasonable jurists. Id. at

342; see also id. at 348 (Scalia, J., concurring) (a COA

must be granted if resolution of the petitioner’s claims

is not “undebatable”). Mr. Buck unquestionably meets

that standard with respect to both the procedural issue

of whether extraordinary circumstances exist and the

underlying constitutional issue of whether his counsel

were ineffective. See Slack, 529 U.S. at 484-85 (when a

petition is dismissed on procedural grounds, determining

whether a COA should issue requires consideration

of whether reasonable jurists could debate both the

underlying constitutional claims and the district court’s

procedural ruling). Because the facts supporting the

underlying constitutional claim inform the extraordinary

circumstances analysis in this case, Mr. Buck begins with

his IAC claim.

I. Trial Counsel Rendered Ineffective Assistance by

Presenting an “ Expert” Opinion that Mr. Buck Is

More Likely to be Dangerous in the Future Because

He Is Black.

The principal issue at the sentencing phase of Duane

Buck’s capital trial was whether he was likely to commit

future acts of criminal violence if sentenced to life

25

imprisonment. Under Texas law, an affirmative finding

by the jury on this special issue was required for a death

sentence. But the prosecution presented no evidence that

Mr. Buck had been violent outside the context of romantic

relationships with two women, and the jurors learned that

he had adjusted well to prison. Consistent with the lack

of future dangerousness evidence, the jury struggled to

determine the appropriate sentence and did not reach a

verdict until the second day of deliberations.

Mr. Buck’s own lawyers, however, tipped the balance

in the prosecution’s favor. They introduced an “expert”

opinion that, because Mr. Buck is Black, he was more

likely to be dangerous in the future. Put another way:

Mr. Buck’s lawyers presented evidence that Mr. Buck

was more deserving of a death sentence under Texas law

because of his race.

Introducing this false and prejudicial evidence was the

epitome of ineffective assistance of counsel. As the CCA

held in 1925, “ [n]o lawyer could believe that” a question

injecting racial bias into a criminal trial “could have been

permissible in any state court, and the very asking of it

was so repulsive to every idea of a fair trial as to cause us

to have no hesitancy in holding it reversible error.” Derrick

v. State, 272 S.W. 458,459 (1925). Yet, over 70 years later,

Mr. Buck’s lawyers not only injected racial bias into his

capital trial, they appealed to the uniquely pernicious

stereotype that “blacks are violence prone.” Turner

v. Murray, 476 U.S. 28, 35 (1986) (plurality opinion).

Even worse, defense counsel did so through a clinical

psychologist who was stamped with the imprimatur of an

“expert,” lending special weight to his opinion.

26

No reasonable defense attorney would have presented

Dr. Quijano’s race-as-dangerousness opinion. Moreover,

there is a reasonable probability that had his opinion not

been presented, at least one juror would have reached

a different conclusion about Mr. Buck’s likelihood

of committing future acts of violence. Mr. Buck has

therefore satisfied both the deficient performance and

prejudice prongs of the Strickland test. See Strickland

v. Washington, 466 U.S. 668 (1984).

A. The District Court Correctly Recognized that

Counsel Performed Deficiently by Knowingly

Exposing Mr. Buck to the Risks o f Racial

Prejudice.

As this Court explained in Strickland, “ the Sixth

Amendment right to counsel exists, and is needed, in order

to protect the fundamental right to a fair trial.” 466 U.S. at

684. “That a person who happens to be a lawyer is present

at trial alongside the accused . . . is not enough to satisfy

the constitutional command.” Id. at 685. Rather, because

the Sixth Amendment “envisions counsel’s playing a role

that is critical to the ability of the adversarial system to

produce just results,” a defendant “is entitled to be assisted

by an attorney, whether retained or appointed, who plays

the role necessary to ensure that the trial is fair.” Id.

The Sixth Amendment right to counsel is therefore the

right to the effective assistance of counsel, measured by

the familiar two-part test of deficient performance and

prejudice. See id. at 686-87.

Counsel’s performance is deficient when it falls “below

an objective standard of reasonableness,” as measured

“under prevailing professional norm s.” Id. at 688.

27

Although that “standard is necessarily a general one,”

Bobby v. Van Hook, 558 U.S. 4, 7 (2009) (per curiam), the

“ [Representation of a criminal defendant entails certain

basic duties,” Strickland, 466 U.S. at 688. These include

the “overarching duty to advocate the defendant’s cause”

and the “duty to bring to bear such skill and knowledge

as will render the trial a reliable adversarial testing

process.” Id.

Mr. Buck’s trial lawyers failed to satisfy these basic

obligations. As the District Court noted, prior to trial,

“Buck’s counsel had received Dr. Quijano’s expert report

. . . clearly stating that Buck’s race made him statistically

more likely to be a future danger.” JA 263a. In that report,

Dr. Quijano discussed seven “ Statistical Factors” that

he deemed relevant to “ Future Dangerousness,” i.e.,

“Whether there is a probability that the defendant would

commit criminal acts of violence that would constitute a

continuing threat to society.” JA 18a, 35a. One of those

factors was: “Race. Black: Increased probability. There

is an over-representation of Blacks among the violent

offenders.” Id. at 19a, 36a. (emphasis in original).

No competent defense counsel would have presented

Dr. Quijano’s race-as-dangerousness opinion to the

jury. This Court stated more than 50 years before

Strickland that one of counsel’s essential functions is to

ensure the defendant is not “convicted upon incompetent-

evidence, or evidence irrelevant to the issue or otherwise

inadmissible.” Powell v. Alabama, 287 U.S. 45, 69

(1932). Dr. Quijano’s race-as-dangerousness opinion was

prototypical “incompetent evidence” that had no place

in a capital sentencing proceeding. The Constitution

requires that “any decision to impose the death sentence

be, and appear to be, based on reason rather than

caprice or emotion,” Godfrey v. Georgia, 496 U.S. 420,

433 (1980) (citation omitted), and such decisions must

reflect an “ individualized inquiry” into the defendant’s

moral culpability, Romano v. Oklahoma, 512 U.S. 1, 7

(1994) (citation omitted). Race is an arbitrary, emotionally

charged factor that has nothing to do with individual

moral culpability. Although it cannot be considered as an

aggravating factor at capital sentencing, Zant v. Stephens,

462 U.S. 862, 885 (1983), Dr. Quijano’s opinion urged the

jurors to do just that.

Injecting race into a capital sentencing proceeding is

not only wholly improper, it poses a special risk of harm to

the defendant. In 2005, this Court repeated an observation

about race that it made in 1880: “It is well known that

prejudices often exist against particular classes in the

community, which sway the judgment of jurors, and which,

therefore, operate in some cases to deny to persons of

those classes the full enjoyment of that protection which

others enjoy.” Miller-Elv. Dretke, 545 U.S. 231,237 (2005)

(quoting Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U.S. 303, 309

(1880)). The risk of racial prejudice swaying the judgment

of jurors is especially pronounced in a capital sentencing

proceeding because “ [f]ear of blacks, which could easily be

stirred up by the violent facts of [the defendant’s] crime,

might incline a juror to favor the death penalty.” Turner,

476 U.S. at 35 (plurality opinion).

Mr. Buck’s court-appointed counsel had a duty to

be aware of these principles. Hinton v. Alabama, 134

S. Ct. 1081, 1089 (2014) (“An attorney’s ignorance of a

point of law that is fundamental to his case combined

with his failure to perform basic research on that point

29

is a quintessential example of unreasonable performance

under Strickland”). As any competent counsel would

have recognized, it was contrary to Mr. Buck’s interests

to present an expert opinion that Mr. Buck possesses

an immutable characteristic that renders him prone to

criminal violence. JA 19a, 36a. Further, anyone with

even a passing knowledge of American history would

understand that the immutable characteristic invoked

by Dr. Quijano— Mr. Buck’s race—was especially likely

to bias the jury against him.

Yet, trial counsel not only “called Dr. Quijano to the

stand,” counsel specifically “elicited his testimony on

this point.” Buck, 132 S. Ct. at 33 (Statement of Alito,

J.); see also JA 263a-264a (noting “ Buck’s counsel

called Dr. Quijano as a witness and relied on his expert

report, although counsel was fully aware of Dr. Quijano’s

inflammatory opinions about race” ).

Dr. Quijano began his testimony by discussing

his credentials. JA 138a-141a. He then described his

evaluation of Mr. Buck, testifying that Mr. Buck has both

a dependent personality disorder— meaning he becomes

obsessive in relationships and has a very difficult time

letting go— as well as alcohol and cocaine dependence

disorders. JA 141a-145a; see also JA 252a-253a.

Counsel then turned Dr. Quijano’s attention to

the issue of future dangerousness. Counsel first asked

Dr. Quijano to confirm that he was “ familiar with the

capital murder punishment issues that jurors are given

in a capital murder case at the punishment phase,” and

that he understood the first issue “is whether the State

has proven beyond a reasonable doubt that there’s a

30

probability that the defendant would engage in future acts

of violence which would constitute a continuing threat to

society.” JA 145a.

Counsel next asked Dr. Quijano to discuss his

“professional opinion regarding Mr. Buck in relation to

that issue,” and specifically the “statistical factors or

environmental factors” that Dr. Quijano found relevant

to Mr. Buck’s probability of future dangerousness. JA

145a-146a. Counsel did so despite knowing that one of the

“statistical factors” Dr. Quijano considered was Mr. Buck’s

race.

Dr. Quijano’s response mirrored his report. See Buck,

132 S. Ct. at 33 (Statement of Alito, J.). He described

seven “ statistical factors we know to predict future

dangerousness,” one of which was “ Race.” JA 146a.

Dr. Quijano elaborated on the purported support for his

opinion that race predicts future dangerousness: “ It’s a sad

commentary that minorities, Hispanics and black people,

are over represented in the Criminal Justice System.” JA

146a. After identifying race and the other six statistical

factors from his report, Dr. Quijano reiterated: “Those

are the statistical factors in deciding whether a person

will or will not constitute a continuing danger.” JA 147a.

Having elicited Dr. Quijano’s race-as-dangerousness

opinion, defense counsel opened the door for the prosecution

to have Dr. Quijano repeat it on cross-examination. See

Buck, 345 F. App’x at 930. The prosecutor did precisely

that, stressing the supposed causal link between race and

dangerousness: “You have determined that the . . . race

factor, black, increases the future dangerousness for

various complicated reasons; is that correct?” JA 170a.

Dr. Quijano responded unequivocally: “Yes.” Id.

31

Trial counsel then presented Dr. Quijano’s race-as-

dangerousness opinion to the jury for a third time, offering

Dr. Quijano’s report into evidence. See Buck, 132 S. Ct. at

33 (Statement of Alito, J.). In his report, Dr. Quijano stated

in no uncertain terms that Mr. Buck’s race increased the

probability of future violence: “Race. Black: Increased

probability. There is an over-representation of Blacks

among the violent offenders.” JA 19a, 36a. Although other

portions of Dr. Quijano’s report were redacted before it

was submitted to the jury, his race-as-dangerousness

opinion was not. Id.

In sum, “the responsibility for eliciting [Dr. Quijano’s]

offensive testimony lay[s] squarely with the defense.”

Buck, 132 S. Ct. at 35 (Statement of Alito, J.).

Texas, however, has sought to defend trial counsel’s

performance by asserting that Dr. Quijano did not say Mr.

Buck’s “race would make him more likely to be a future

danger.” Opposition to Petition for a Writ of Certiorari

(“Cert. Qpp’n” ) at 21, Buck v. Stephens, 136 S. Ct. 2409

(Mar. 21,2016) (No. 15-8049) (mem,). Instead, according to

Texas, Dr. Quijano’s “brief remarks . . . about ‘minorities,

Hispanics and blacks’ being overrepresented in the

criminal justice system are inherently mitigating.” Id.

at 21-22 (citation omitted). Those assertions are flatly

untrue, and reflect an effort to sanitize the profoundly

troubling record in this capital case.

There was nothing mitigating about Dr. Quijano’s

testimony about the overrepresentation of Blacks and

Hispanics in the criminal justice system. Instead,

Dr. Quijano relied on that overrepresentation as the

justification for his repeated assertions—which Texas now

32

refuses to acknowledge— that Mr. Buck’s race made him

more likely to be a future danger. To reiterate:

• On direct examination, Dr. Quijano testified that

“race” is one of seven “statistical factors we know

to predict future dangerousness.” JA 146a.

• On cross-examination, Dr. Quijano agreed with the

prosecution that the “race factor, black, increases

the future dangerousness for various complicated

reasons.” JA 170a.

• In his report, which was submitted to the jury,

Dr. Quijano stated that Mr. Buck’s “Race. Black”

created an “Increased probability” that he would

commit future acts of violence. JA 19a, 36a.

By presenting the jury with an expert opinion that Mr.

Buck was more likely to commit criminal acts of violence

because he is Black, and was therefore more deserving of

a death sentence under Texas law, trial counsel rendered

deficient performance under Strickland. In the District

Court’s words:

Buck’s counsel recklessly exposed his client

to the risks of racial prejudice and introduced

testimony that was contrary to his client’s

interests. His perform ance fell below an

objective standard of reasonableness, and

the Court therefore finds that trial counsel’s

performance was constitutionally deficient.

JA 264a.

33

B. The D istr ict C ourt E rred by C oncluding

that Mr. B uck Was Not Prejudiced by His

Trial Counsel’s Constitutionally Deficient

Performance.

The touchstone of Strickland’s prejudice prong is

whether counsel’s constitutionally deficient performance

‘“deprive[d] the defendant of a fair trial, a trial whose

result is reliable.” ’ Harrington v. Richter, 562 U.S. 86,104

(2011) (quoting Strickland, 466 U.S. at 687). “The result

of a proceeding can be rendered unreliable, and hence

the proceeding itself unfair, even if the errors of counsel

cannot be shown by a preponderance of the evidence to

have determined the outcome.” Strickland, 466 U.S. at

694. Although the mere possibility of a different outcome

is insufficient, the prejudice prong is satisfied when there

is “a probability sufficient to undermine confidence in

the outcome.” Id.; see also Harrington, 562 U.S. at 112.

Because Texas requires jury unanimity, a reasonable

probability that one juror would have reached a different

conclusion absent Dr. Quijano’s race-as-dangerousness

testimony is sufficient to establish prejudice. See Wiggins

v. Smith, 539 U.S. 510, 537 (2003).

Mr. Buck easily satisfies this standard. Contrary to

the District Court’s assertion that “any harm caused by

[Dr. Quijano’s] objectionable testimony was de minimis','

JA 272a, it is well-settled that appeals to racial prejudice

deprive the accused of his right to a fair trial decided by an

impartial jury. The appeals to racial prejudice in this ease

were particularly harmful because: (1) they invoked the

stereotype that Black people are more likely to be violent

criminals; (2) they were presented as the professional

opinion of a defense expert who was “appointed by Judge

34

Collins of the 208th District Court to do an evaluation on

the defendant Duane Edward Buck” and was “paid by

the County to do this work,” JA 140a; and (3) the central

disputed issue at sentencing was whether Mr. Buck was

likely to be a future danger.

1. Dr. Quijano’s Race-as-Dangerous Opinion

Was Highly Prejudicial.

When jurors are told that the defendant’s race is

associated with criminality, the harm to the defendant

is obvious and substantial. Such statements not only

“ ‘tend[] to create race prejudice,” ’ they ‘“conveyG the

imputation that the accused belonged to a class of persons

peculiarly’” predisposed to criminal behavior. Allison v.

State, 248 S.W.2d 147,148 (Tex. Crim. App. 1952) (citation

omitted). This deprives the defendant of his fundamental

right to a fair trial, i.e., one in which the “jury considers]

only relevant and competent evidence,” Bruton v. United

States, 391 U.S. 123, 131 n.6 (1968), “free from ethnic,

racial, or political prejudice, or predisposition about the

defendant’s culpability,” ’ Powers v. Ohio, 499 U.S. 400,

411 (1991) (citations omitted). Cf. Taylor v. Kentucky, 436

U.S. 478, 487-88 (1978) (failure to provide a presumption

of innocence instruction violated due process when,

inter alia, the prosecutor’s “repeated suggestions that

petitioner’s status as a defendant tended to establish his

guilt created a genuine danger that the jury would convict

petitioner on the basis o f . . . extraneous considerations”).

As Judge Winter has explained, the “ [ijnjection of a

defendant’s ethnicity into a trial as evidence of criminal

behavior is self-evidently improper and prejudicial. . . .”

United States v. Cruz, 981 F.2d 659, 664 (2d Cir. 1992).

35

The prejudice arising from Dr. Quijano’s race-as-

dangerousness opinion was magnified for two reasons.

First, it was presented at a capital sentencing hearing