Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education v. Swann Brief of Cross Petitioners

Public Court Documents

October 12, 1970

111 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education v. Swann Brief of Cross Petitioners, 1970. 9e29694f-ad9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/6e960a1f-c8e8-41b2-b50f-ff33332502a1/charlotte-mecklenburg-board-of-education-v-swann-brief-of-cross-petitioners. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

(i)

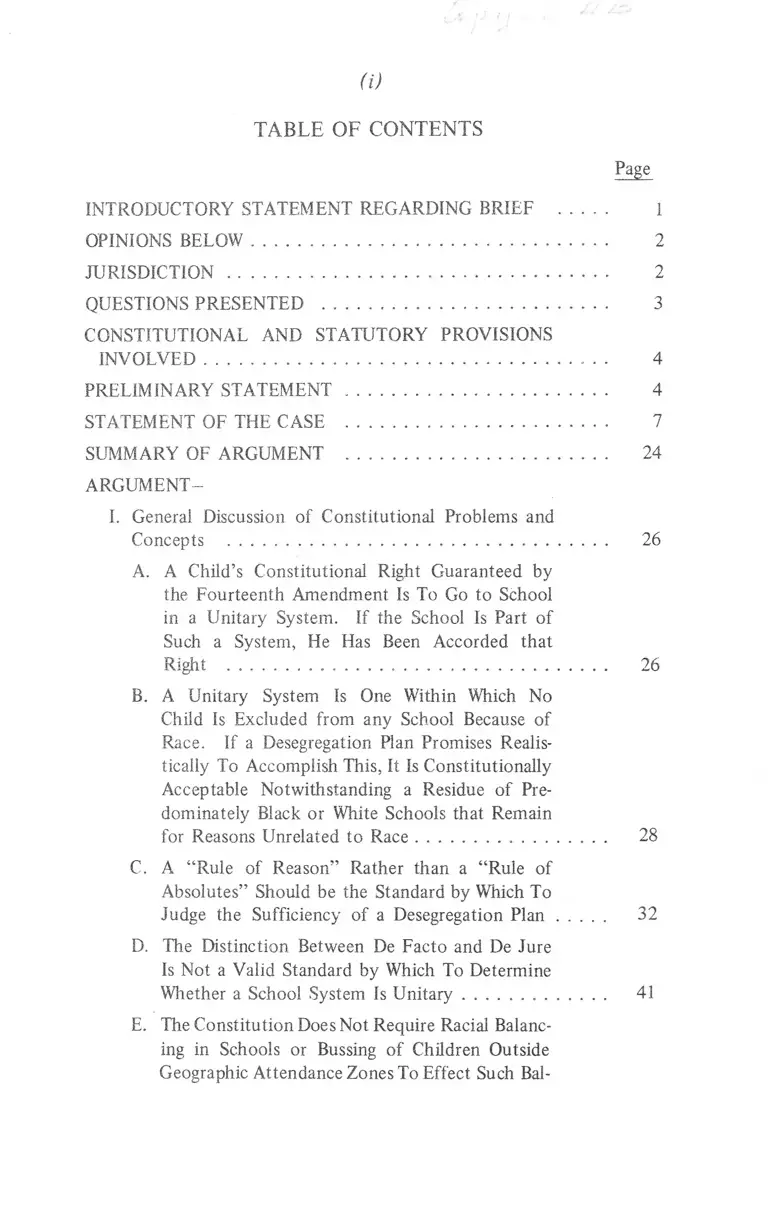

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

INTRODUCTORY STATEMENT REGARDING BRIEF .......... 1

OPINIONS BELOW............................................................................ 2

JURISDICTION................................................................................. 2

QUESTIONS PRESENTED ............................................................. 3

CONSTITUTIONAL AND STATUTORY PROVISIONS

INVOLVED...................................................................................... 4

PRELIMINARY STATEMENT........................................................ 4

STATEMENT OF THE CASE ........................................................ 7

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT ........................................................ 24

ARGUMENT—

I. General Discussion of Constitutional Problems and

Concepts ................................................................................. 26

A. A Child’s Constitutional Right Guaranteed by

the Fourteenth Amendment Is To Go to School

in a Unitary System. If the School Is Part of

Such a System, He Has Been Accorded that

Right . ................. 26

B. A Unitary System Is One Within Which No

Child Is Excluded from any School Because of

Race. If a Desegregation Plan Promises Realis

tically To Accomplish This, It Is Constitutionally

Acceptable Notwithstanding a Residue of Pre

dominately Black or White Schools that Remain

for Reasons Unrelated to Race......................................... 28

C. A “Rule of Reason” Rather than a “Rule of

Absolutes” Should be the Standard by Which To

Judge the Sufficiency of a Desegregation P la n .......... 32

D. The Distinction Between De Facto and De Jure

Is Not a Valid Standard by Which To Determine

Whether a School System Is U nitary .............................. 41

E. The Constitution Does Not Require Racial Balanc

ing in Schools or Bussing of Children Outside

Geographic Attendance Zones To Effect Such Bal-

1

ancing. Balancing and Compulsory Bussing In

fringe on the Personal Rights and Liberties of the

Children Involved ....................................................... 48

1. Racial Balancing and the Bussing To Achieve

It Were the Bases for the Decisions of the

Trial Court and Court of Appeals .......................... 48

2. Racial Balancing and Compulsory Bussing

Required by the District and Circuit Courts

Violate the Constitutional Rights of the

Children Involved .................................................. 52

3. A Neighborhood Plan Fairly Administered

Without Racial Bias Satisfies the Constitu

tional Requirements of a Unitary System......... 56

4. The Compulsory Bussing Approved by the

Court of Appeals Is Violative of the Provi

sions of Section 401(b) and 407(a)(2) of the

Civil Rights Act of 1964 [42 U.S.C. 2000c g7

(b) and 2000c-6(a)(2)] Which Expressly

Prohibits a United States Court To Order

Transportation To Achieve Racial Balance

in S chools................................................................. 60

F. Racial Balance—the Harbinger of Massive Court

Involvement in Social Theories ...................................... 63

II. Discussion of Constitutional Principles Applied to

Desegregation P lan s................................................................. 69

A. General Statement Regarding Desegregation Plans

Involved in this Case ....................................................... 69

B. The Board Plan Converts the Charlotte-Mecklen-

burg Schools to a Unitary System. The Fourth

Circuit Joined in the Error of the Trial Court by

( ii)

Disapproving that Plan............... ....................................... 70

1. The Board Plan Squares With the Conversion

Checklist Prescribed by Green .............................. 70

2. The Board Plan Based on Geographic Attend

ance Zones Gerrymandered To Achieve

Maximum Racial Mix Fully Complies with

Constitutional Requirements for Desegrega

tion of the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools

and Their Student Bodies............................

( Hi)

C. The Court Approved Finger Plan Exceeds Consti

tutional Requirements by Requiring Racial Bal

ancing and the Bussing To Implement It. The

Fourth Circuit Joined in the Trial Court’s Errors

by Disapproving the Board Plan and Misapplying

Its Own Rule of Reason ................................................... 76

1. An Analysis of the Court Approved Finger

Plan Shows the Racial Balancing Imposed

Upon the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools . . . . 77

(a) Elementary Schools ........................................ 77

(b) Junior High Schools ........................................... 78

(c) Senior High Schools ........................................... 79

2. The Court-Approved Finger Plan Is Unrea

sonable and Proper Consideration Was Not

Given to the Burdens Which that Plan

Imposes on the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Sys

tem ........................................................................... 80

D. The HEW Elementary Plan is Educationally Un

sound, Requires Racial Balancing, Fosters Reseg

regation and Is Unreasonable ........................................

E. The Elementary Plan of the Board Minority Is

Incomplete and Unlawfully Exceeds Constitu

tional Requirements by Requiring Complete Ra

cial Balancing of Every Elementary School and

the Bussing To Implement It. The District Court

Erred in Approving that Plan as a Reasonable

Alternative ...................................................................... 88

F. The Earlier Draft of the Finger Elementary Plan Is

Incomplete and Unlawfully Exceeds Constitu

tional Requirements by Requiring Racial Balanc

ing. The District Court Erred in Approving that

Plan as a Reasonable Alternative ................................... 90

G. In Assessing the Effectiveness of a Desegregation

Plan, a Rule of Reason Requires that Due Con

sideration Should be Accorded School Boards and

Administrators in Controlling the Destiny of

Public Education ............................................................ 91

CONCLUSION .................................................................... 93

Brief Appendix

Statistical Data Relating to the Charlotte-Mecklenburg

Schools and the Board Plan ....................................................... a -1

Maps Showing Desegregation Plans (Filed as Separate

Appendix):

Board Elementary Plan.............................................................. No. 1

Board Rezoned Elementary Plan (Superimposed Upon

1969-70 Attendance A reas).................................................... No. 2

Court-Approved Finger Elementary P lan ................................ No. 3

HEW Elementary P la n .............................................................. No. 4

Board Minority Elementary Plan .......................................... No. 5

Board Junior High Plan ......................................................... No. 6

Court-Approved Finger Junior High Plan................................No. 7

Board Senior High Plan ......................................................... No. 8

Court-Approved Finger Senior High Plan................................No. 9

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases:

Alexander v. Holmes, 396 U.S. 19 (1969) .......... .. 12, 28, 29, 30, 61

Baldwin v. State of New York,__ U.S.___ , 90 S.Ct. 1886

(1970)............................................................................................... 38

Bivins v. Bibb County Board of Education, 419 F.2d 1211

(5th Cir. 1 9 7 0 ) ................................................................................ 91

Brinson v. State of Florida, County of Dade, 273 F. Supp.

840, (S.D. Fla. 1967)...................................................................... 38

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954) .passim

Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U.S. 294 (1955) .passim

Building Service Employees International Union v. Gazzam,

339 U.S. 991 (1950) ...................................................................... 61

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1 (1958) ........................................... 44; 64

Cox v. Louisiana, 379 U.S. 536 (1965) ........................................ 37

Deal v. Cincinnati Board of Education, 419 F.2d 1387, (6th

Cir. 1969)............................................................................ 31 ,43 ,53 ,58

Deal v. Cincinnati Board of Education, 419 F.2d 209, (6th

Cir. 1966)........................................................................................... 57

Dennis v. United States, 341 U.S. 494 (1 9 5 1 )............................... 37,40

(iv)

(v)

Duncan v. Louisiana, 391 U.S. 145 (1 9 6 8 ) ................................... 37

Ellis v. Board of Public Instruction of Orange County, 423

F.2d 203 (5th Cir. 1970) ......................... .................................. 31

Gideon v. Wainwright, 372 U.S. 335 (1963) .............................. 38

Gilbert v. Minnesota, 254 U.S. 325 (1 9 2 0 ) ................................... 37

Gitlow v. People of the State of New York, 268 U.S. 652

(1925)................................................................................................ 37

Goss v. Board of Education, City of Knoxville, Tennessee,

373 U.S. 683 (1 9 6 3 )............ ......................................................... 7, 64

Goss v. Board of Education, City of Knoxville, Tennessee,

406 F.2d 1183 (6th Cir. 1969) .................................................. 31

Green v. New Kent County, 391 U.S. 430 (1968) ..................passim

Hawthorne v. Lunenburg County, 413 F.2d 53 (4th Cir.

1969) ....................................................................................... 10

Meyer v. Nebraska, 262 U.S. 390 (1923) .......... ........................ 68

Mohammad v. Sommers, 238 F. Supp. 806 (E.D. Mich.

1964) ............................................................................................... 37

Northcross v. Board of Education, 397 U.S. 232 (1970) .......... 28

Norwood v. Tucker, 287 F.2d 798 (8th Cir. 1961) . ............... 64

Pierce v. Society of Sisters, 268 U.S. 510 (1925)......................... 67

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537 (1896) ......................... 35 ,44 ,45 ,75

Reynolds v. Simms, 377 U.S. 533 (1964) 67

Ross v. Eckels, Houston Independent School District, No.

10,444,___F.Supp.___ (S.D. Texas 1970) .............................. 33, 54

Schenck v. United States, 249 U.S. 47 (1919) .............................. 37

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1 (1948) ..................................... 47

Sparrow v. Gill, 304 F. Supp. 86 (M.D.N.C. 1969)......................... 19

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education, 242

F. Supp. 667 (1965) ...................................................................... 8

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education, 369

F.2d 29 (1 9 6 6 ) .................................................................... .. 8, 44

Times Film Corporation v. City of Chicago, 365 U.S. 43

(1961)................................................................................................ 37

h i)

United States v. Greenwood Municipal Separate School

District, 406 F.2d 1085 (5th Cir. 1 9 6 9 ) ...................................... 31

United States v. Jefferson County Board of Education, 372

F.2d, 836 (5th Cir. 1966) Affd on rehearing, en banc,

380 F.2d 385 (5th Cir. 1967) .................... 35 ,54 ,5 5 ,6 0 ,6 2 ,6 3 ,6 4

United States v. Montgomery County Board of Education,

395 U.S. 225 (1 9 6 9 ) ............................................. 9,14,51

Statutes:

Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. 2000c(b) and 2000c-6

( a ) ( 2 ) ......................................................................................4 ,60 ,61 ,62

N.C. Gen. Stat. Secs. 115 et seq....................................................... 53

Other Authorities:

Bickell, The Supreme Court and the Idea of Progress (1970).......... 74

110 Congressional Record, Page 12717, June 4, 1964.......... 63

Nations Schools, June 1970, page 100, “Forced Busing

Vetoed by 90% of Schoolmen” 72

Petitioners’ Brief in Green v. New Kent County, October

Term 1967, No. 695 ....................................................... 57, 59, 64, 65

PROFILE, Metromedia Radio News, February 27, 1970 . . . 58

Racial Isolation in the Public Schools—Summary of a

Report by the Commission on Civil Rights (1 9 6 7 ) ............. 20, 47, 56

SCHOOL DESEGREGATION: A Free and Open Society,

(116Cong. Rec. §4351, Daily Ed., March 24, 1970).................. 58,91

United Press International Release, May 17, 1970 ....................... 45

21 U.S.L.W. 3164 (1952)...........................................

Webster’s Seventh New Collegiate Dictionary (1967)

64, 74

35

IN THE

Supreme Court of the United States

OCTOBER TERM, 1970

No. 349

CHARLOTTE-MECKLENBURG

BOARD OF EDUCATION, et al,

Cross Petitioners,

v.

JAMES E. SWANN, et al,

Cross Respondents.

BRIEF OF CROSS PETITIONERS

INTRODUCTORY STATEMENT REGARDING BRIEF

The briefs submitted in the companion cases Nos. 281

and 349 are identical. This statement is made so that this

Court may be spared the inconvenience of a separate detailed

analysis of both briefs.

Case No. 281 relates to the Petition filed by the plaintiffs

for a review of the decision of the Circuit Court of Appeals

2

for the Fourth Circuit. Case No. 349 relates to the Cross-

Petition of the defendants from the same decision. The plain

tiff’s Petition in case 281 was granted on June 29, 1970. Al

though action on the defendants’ Cross-Petition has been de

ferred until the convening of this Court at its October 12,

Term, 1970, this Court has advised that both cases will be

heard on October 12, 1970, and has instructed the defend

ants to file briefs in both cases. The two cases have not been

consolidated for briefing.

Each of the two cases involves the same school system,

the same orders of the district court and Circuit Court and

the same issues. In order to be of as much assistance as possi

ble to this Court, it is prudent that one comprehensive pre

sentation shall be made. It is for this reason that, although

separate briefs are filed, their text and content are the same.

OPINIONS BELOW

The opinions of the courts below are set forth in Brief for

Petitioners filed in No. 281 on pages 1 through 3 thereof.

JURISDICTION

The judgment of the Court of Appeals for the Fourth

Circuit was entered on May 26, 1970. The jurisdiction of

this court is invoked under 28 U.S.C. 1254(1). The Petition

for Writ of Certiorari was filed in this court on July 2, 1970.

On August 31, 1970, the Chief Justice deferred action on

Cross Respondents’ pending Petition for Writ of Certiorari

and directed filing of briefs and set this case for oral argu

ment on Monday, October 12, 1970.

3

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

1. Did the Court of Appeals join in the error of the trial

court in rejecting the desegregation plan offered by the Board

of Education where 68% of the black students would attend

schools in which their race was in the minority and where

the remaining 32% of the black students would attend

schools having white ratios of 17% to 1% and these black

students would be taught by a predominantly white faculty

and further where such black students were offered more

generous freedom of transfer than that offered by the custo

mary majority to minority transfers?

2. Did the Court of Appeals join in the error of the trial

court in rejecting the plan for desegregation of the 72 ele

mentary schools prepared and offered by the Board of Edu

cation, where the plan left no all-black schools, though nine

of 72 schools had white ratios of 1% to 17% and black

students attending those schools would have an untrammeled

right to transfer to any one of the 63 remaining elementary

schools, and upon departure from elementary schools would

be assured of a desegregated education during the remainder

of their schooling?

3. Did the Court of Appeals join in the error of the trial

court in rejecting (by the trial court’s offering the Board a

“Hobson’s choice”) the Board plan for desegregation of

junior high schools where only one of 21 junior high schools

would have more than a 39% black student ratio and the

remaining predominately black school would house 758

black and 84 white students and have a predominately white

faculty by imposing a requirement on the Board to create

nine black satellite districts containing approximately 2,700

black students and assigning them to predominately white

suburban junior high schools?

4. Did the Court of Appeals join in the error of the trial

court in rejecting the Board plan for desegregation of senior

high schools where the plan provided that no school would

have more than a 36% black ratio and that each school would

4

have a predominately white faculty and in imposing a fur

ther requirement upon the Board that 300 black students re

siding in four designated grids would be bussed a substantial

distance from the northwestern part of the city to a high

school serving the extreme southeastern portion of the

county?

5. Did the Court of Appeals join in the error of the trial

court in imposing racial balances in junior and senior high

schools in contravention of Title 42 U.S.C. 2000(c)(b) and

6(a)(2) (Sections 401(b) and 407(a)(2)) of the Civil Rights

Act of 1964.

CONSTITUTIONAL AND STATUTORY

PROVISIONS INVOLVED

This case involves the equal protection clause of the Four

teenth Amendment of the Constitution of the United States,

Section 401(b) and 407(a)(2) of the Civil Rights Act of

1964 [42 U.S.C. 2000(c)(b) and 6(a)(2)],

PRELIMINARY STATEMENT

The principal question presented by the several appeals

herein relates to whether or not the Charlotte-Mecklenburg

public school system may retain one or more predominately

black schools. If the absolutists are to prevail, then the pre

sentation which follows is wholly irrelevant. The Court of

Appeals held that no such absolute requirement exists as

desegregation of the predominately black schools will be

adjudged by the “test of reasonableness.”

In order to answer the question, one must have an under

standing of this school system. The system involves 103

schools, 4 kindergarten programs and one learning academy,

which last year served approximately 84,500 students of

which 29% were black and 71% were white. The system is

expected to grow by an approximate 3,000 students this

5

school year. In comparison to other school systems in this

nation, the system ranks 43rd largest.

As an urban school district, it shares the same problem of

other urban school systems. Since 1954, the black student

population has increased from 10,000 to 24,000 students and

during this period eleven formerly all-white schools are now

almost entirely black (691a). The transition has been rapid.

In 1965 these eleven schools housed a 35% black student

population. During the 1969-70 school year, these schools

housed an 81% black population and the areas in which this

transition has taken place are located generally in the older

white neighborhoods. Charlotte has experienced phenomenal

growth and, therefore, the older neighborhoods are primarily

located near the center of the city, which serves as the base

for the expanding black areas as whites on the economic

move improve their position; blacks improving their position

take over the white homes. This had led to the transition of

schools from white to black. Today, 95% of the black stu

dents reside in the northwestern inner-city quadrant or the

fringes thereof.

The Board was in the process of combating this problem

by construction of schools in areas which would offer more

stable desegregation, the most notable of which were Olym

pic High School, originally scheduled for construction in a

predominately black neighborhood, and Randolph Junior

High which was also scheduled for construction in a similar

neighborhood (72a-73a).

Further efforts of the Board involved closing and consoli

dating of twenty schools; creation of a single athletic league;

nondiscriminatory employment practices; substantial desegre

gation of school faculties with total desegregation to follow

for the 1970-71 school year; cross racial assignment of prin

cipals; appointment of black professionals to ranking admini

strative positions; board appointment of a black member to

the Board of Education; elimination of the dual bus system;

nondiscrimination with respect to teacher salaries, school

fees, school lunches, library books, instructional materials,

6

quality of school buildings, use of federal funds, course

offerings and evaluation of students; merger of the black and

white PTA Councils; operation of specialized and supple

mentary' programs implemented to increase desegregation;

redesigning of freedom of choice so that its only effect

would increase desegregation and give racial stability to the

schools; gerrymandering of attendance lines to promote

maximum racial desegregation and other techniques designed

to create and promote racial stability (681a-683a, 1265a-

1266a).

The rural areas of the school system do not offer such

difficult problems in desegregation as the races are scattered

and, therefore, as with most rural systems, these schools

present substantial stable desegregation (313a).

Freedom of choice has neither perpetuated nor made sub

stantial inroads on the desegregation problem. The super

intendent estimated that approximately 1,200 (565a) white

students had left predominately black schools where they

would have been mixed in varying degrees with approxi

mately 16,000 blacks.

In 1957 Charlotte led the South in opening its schools

to students of both races. However, it is admitted that there

were few students who took advantage of this option. Con

solidation of the city and county systems, the two largest

in the state, occurred in 1961, creating a school system hav

ing an east-west span of 22 miles and a north-south span of

36 miles and comprised approximately 550 square miles.

The City of Charlotte contains 64 square miles, making it

larger than the District of Columbia. The county is nearly

twice the size of the City of New York.

In 1965 a plan was devised by the Board embracing free

dom of choice, rezoning and non-racial assignment of faculty

which entirely abolished the former dual system under the

law as then understood. That plan was approved by the

district court in 1965 and by the Court of Appeals in 1966.

The plan led to the abolition of all dual auxiliary programs

and services, such as transportation, athletic leagues, PTA’s,

etc.

7

Consistent with racial anonymity, racial identification of

students and faculty was completely removed from all school

records. Because of this, during the course of this litigation,

requests for racial information created a substantial burden

on the school system in producing this data.

The plan proposed by the Board eliminates 8 of the 17

predominately black elementary schools, four of the five

predominately black junior high schools and establishes ten

senior high schools so that no high school will have more

than a 36% black ratio. It reduces the number of blacks

attending predominately black schools to 7,497. (Compare

district court’s finding of 16,000 previously). Faculties will

be racially balanced.

These exemplary steps have been taken by a school board

which petitioners variously label as “recalcitrant,” “contemp

tuous,” “lawless” and similar characterizations.

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

The plan for desegregation offered to the district court

by the Charlotte-Meckienburg Board of Education would

place 68% of the 24,000 black students in predominately

white schools and the remaining 32% would attend schools

having a black ratio of 83% to 99%. No other school sys

tem of similar size and complexity in this nation has the

degree and volume of desegregation offered by this plan.

The exemplary proposal of the Board was summarily re

jected by the district court for the reason that this system

would not be permitted to have a predominately black

school. The district court therefore ordered racial balancing

of the schools served by the system.

The present action was instituted in 1965 which resulted

in the district court’s approval of the plan then offered by

the Board. The salient features of the plan related to school

closings, school consolidation, freedom of choice (as sug

gested by Goss v. Knoxville, 373 U.S. 683 (1963)), rezon

ing, nonracial assignment of teachers, and nonracial records

of students. Circuit Judge Craven, then district judge, noted:

8

As a general proposition, it is undoubtedly true that

one could deliberately sit down with the purpose in

mind to change lines in order to increase mixing of

the races and accomplish the same with some degree

of success. I know of no such duty upon either the

school board or the district court. The question is

not whether zones can be gerrymandered for the as

sumed good purpose of racial mixing, but whether

gerrymandering occurred for the unconstitutional

purpose of preventing the mixing of races. I am

unable to find from the evidence a sufficient show

ing of the unconstitutional purpose with respect to

any school zone . . . Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg

Board o f Education, 242 F. Supp. 667 (1965).

The holding of the district court was affirmed by the Court

of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit in Swann v. Charlotte-

Mecklenburg Board o f Education, 369 F.2d 29 (1966).

Following the Supreme Court decision in Green v. New

Kent County, 391 U.S. 430 (1968), and companion cases,

the petitioners filed a motion for further relief alleging dis

crimination in teacher salaries, school plants, facilities and

numerous other areas, and in addition sought further desegre

gation. During the course of the hearings conducted in

March 1969, the district court noted that it was familiar

with the fact that in this system black teachers as a group

were paid higher salaries than white teachers for the reason

that they had longer tenure and had more graduate educa

tion (93a).

In its order of April 23, 1969, the district court found

there was no racial discrimination or inequality with ref

erence to the use of federal funds for special aid to the

disadvantaged, use of mobile classrooms, the quality of

school buildings and equipment, coaching of athletics, parent-

teacher association contributions and activities, school fees,

school lunches, library books, elective courses, individual

evaluation of students and gerrymandering (293a-302a).

9

The district court further noted that school location in

Charlotte had followed residential development including its

de facto patterns of segregation (305a).

With respect to the motives and judgment of the School

Board, the district court found that the schools had been

operating pursuant to . . the general understanding of

1965 about the law regarding desegregation.” The Board

had “achieved a degree and volume of desegregation of

schools apparently unsurpassed in these parts, and have ex

ceeded the performance of any school board whose actions

have been reviewed in the appellate court decisions.” The

schools served by this system were “in many respects models

for others”, and “the rules of the game have changed and

the methods and philosophies which in good faith the Board

have followed are no longer adequate to complete the job

which the courts now say must be done ‘now’.” (31 la-312a).

The court then concluded:

The school board has an affirmative duty to promote

faculty desegregation and desegregation of pupils and

to deal with the program of the all-black schools

(313a). (Emphasis added)

Thereupon, the district court directed the Board to sub

mit a plan for complete desegregation of teachers to be effec

tive for the 1969-70 school year and to submit a plan and

time table for the desegregation of pupils to be predomi

nantly effective in the fall of 1969 and completed by the

fall of 1970 (314a-315a). The plan submitted pursuant to

the order of April 23 was found inadequate by the district

court and submission of a new plan by August 4 was di

rected.

During the interim, this Court decided the case of United

States v. Montgomery, 395 U.S. 225 (1969), which for the

first time indicated limited racial ratios in faculty could be

required by the courts.1 In accordance with Montgomery,

1 In Montgomery, supra, page 236, the court noted: “ . . . Petitioners

on the other hand, do not argue for precisely equal ratios in every

school under all circumstances . . . . As the United States, Petitioner in

10

supra, the Board of Education proposed a plan for desegre

gation which would produce substantial faculty2 and stu

dent desegregation for the school year 1969-70 and proposed

a comprehensive computer-assisted study for the purpose of

restructuring attendance lines for the year 1970-71. It was

estimated that the study would require approximately six

months to complete (487a). On August 15, 1969, the district

court entered an order (579a) in which it noted the repudia

tion by the Fourth Circuit of the Briggs v. Elliott dictum on

July 11 in Hawthorne v. Lunenburg, 413 F.2d 53 (4th Cir.

1969) (581a). The trial judge found that the Board had

acknowledged its affirmative duty to desegregate pupils,

teachers, principals, and staff members at the earliest possible

date (583a) and had dramatically exceeded its goal in desegre

gating former all black faculties (584a). It approved the

reassignment of consenting inner-city black students to out

lying white schools for the school year 1969-70.3 Further,

No. 798, recognizes in its brief, the district court’s order is designed as

a remedy for past racial assignment . . . . We do not, in other words,

argue here that racially balanced faculties are constitutionally or legally

required.”

2The Board reported: “With reference to faculty desegregation,

substantial changes have been made as indicated on Exhibit “A” (498a-

502a). With few exceptions, schools having black or nearly all black

students have white faculties ranging from 40 to 50 percent of the

faculty of such schools. By the school term 1970-71, further faculty

desegregation will be experienced.” (495a).

3 The Board proposed offering transportation to the reassigned black

students and made extensive efforts to secure their acceptance of

reassignment. The court stated:

However, this part of the plan is not compulsory. Students

who want to remain in the comfort of their area may elect to

attend the Zebulon Vance School (Irwin Avenue) instead;

alternatives also are provided for the junior high students.

(587a).

In response to objections to reassignment of blacks, the district court

stated:

No legal authority is cited that the Constitution prohibits

transportation of consenting black children from an inferior

educational environment into a better environment for the

13

the court approved in principle the proposed restructuring

of attendance lines and other factors for the 1970-71 school

year, but rejected them for lack of specific detail and time

table.4 Results of the desegregation of faculties commended

by the district court appears in the record (642a-649a).

In view of the fact that it was impossible to complete

the computer restructuring of attendance lines within the

time limited, motion was made for additional time in which

to present the plan. The district court responded by pre

senting interrogatories to the Board and issuing Its last be

nign statement on behalf of the Board as follows:

Nearly six months after the original order, faculty

desegregation is well along and there have been a

number of substantial improvements in the stated

policies of the Board, including the stated assump

tion of the duty by the Board to desegregate the

schools “at the earliest possible date.” Limited steps

purpose of complying with the constitutional requirement of

equal protection of laws. (589a). (Emphasis added.)

The Board pointed out that it could not specify the number of students

who might object to such assignments (493a).

Nevertheless, later the district court unjustly condemned the Board

for not carrying out the plan as “advertised.” (658a). “The perform

ance gap is wide.” (659a).

At the request of black community leaders, the Board proposed and

secured a modification to permit substitution of Irwin Avenue Junior

High School for the Zeb Vance school for black students exercising

freedom of choice to attend a black elementary school in the inner

city. The district court denied the Board the opportunity of upgrading

the education for these black students by imposing restrictions on

innovative programs for such students unless provided for all blacks

who transfer to white schools (593a). The Board was forced to

abandon innovative programs for these blacks as such programs require

full student participation or segregation of black students in the white

schools.

4The Board proposed completing the computer restructuring of

attendance lines within six months or February 1, 1970 (487a). Fur

thermore, implementation was directed for the school year beginning

1970-71. (457a and 315a).

12

have been taken toward compliance with pupil de

segregation provisions of the original order , . .

(601a).

Pending application for an extension of time, this Court

announced its decision in Alexander v. Holmes County, 369

U.S. 19 (1969), and the district court held that as a result

of Alexander, discretion to grant an extension was prohibited

(667a). The district court in its November 7, 1969, order

then proceeded to severely criticize the Board for not imple

menting its 1969-70 desegregation plan. The district court

stated “the plan has not been carried out as advertised”

(658a) and “the ‘performance gap’ is wide” (659a). It is

difficult to reconcile this criticism in the face of the district

court’s previous defense of the right of the Board to trans

port consenting black students to outlying schools and in

view of faculty desegregation that resulted in precisely the

figures estimated by the Board (589a and 584a). The dis

trict court reversed its earlier finding . . Location of

schools in Charlotte has followed the local pattern of resi

dential development, including its de facto patterns of segre

gation” (305a) and substituted “ . . . There is so much state

action imbeded in the shaping of these events that the re

sulting segregation is not innocent or ‘de facto’, and the

resulting schools are not ‘unitary’ or desegregated.” The

district court further found that freedom of choice had

tended to perpetuate segregation by allowing children to

leave schools where their race would be a minority (662a).5

The district court noted that the school system ranked high

with reference to desegregation in comparison with the 100

largest school systems, but held this to be immaterial (664a).

5 The evidence clearly shows that only 1,200 white students had left

predominately black schools (665a) (housing a total of 16,000 blacks).

This would therefore appear to fall under the de minimus rule. Com

pare the limited number of students who sought freedom of choice and

the infinitesimal effect it had on desegregation for the school year

1969-70 (635a-638a).

13

For reasons not understood, the attitude of the district

court changed with increasing frequency to condemnation

or misconstruction of whatever the Board proposed. It

assumed that the Board’s computer program, designed to

promote stability by a 40% limitation on black student assign

ments, precluded white students from attending predomi

nately black schools. Obviously, if the computer designed a

school on a 50/50 ratio, the whites would soon leave the

attendance district. The Board has no intention of devising

attendance districts which would offer such instability.

However, after the best efforts of the computer had been

exhausted, those white students residing in the ultimate at

tendance zones populated predominately by blacks, would

nevertheless be assigned to those schools. The district court

simply misconstrued one step of the Board plan as constitut

ing the final plan.

In fairness to the district court and the petitioners, the

Board on October 19, 1969, gave advance notice that its plan

would be unable to eliminate each all-black school (665a).6

The district court, continuing its castigation of the Board,

said the Board had “demonstrated a yawning gap between

predictions and performance.” (666a). The court thereupon

directed the filing of a plan for desegregation ten days later

on November 17, notwithstanding the fact that the Board

had reaffirmed February 1, 1970, as the earliest date for

presentation of a comprehensive plan.

Therefore, faced with this unrealistic time table, the Board

was compelled to present an admittedly incomplete plan for

desegregation (670a) and report (680a) in which the Board

took a strong position for the purpose of attempting to de

termine the meaning of a “unitary system” and related terms.

Attention is directed to the fact that the Board predictions

with reference to desegregation of elementary schools was

substantially accurate as disclosed by the following:

6At this point, the Board had been admonished to “deal with the

problem of the all black schools” (313a).

14

Percentage Projected No. Board Final Plan,

Black of Schools No. of Schools

Students Nov. 17, 1969 Feb. 2, 1970

0-10% 21 20

11-40% 44 43

41-100% 7 9

It would therefore appear that the Board performed as

“advertised”. There was no wide “performance gap” and

there was no “yawning gap between predictions and per

formances.” The court was further advised in August that

the Board plan would be complete approximately the first

of February 1970, and the Board performed (726a).

On December 1, 1969, the district court again miscon

strued the computer instructions as being the results of a

finalized plan. Although the Board proposed that each

faculty would be predominately white at each school, the

court seemed to take offense at the fact that there was no

promise of total balance (700a). Compare Montgomery,

supra, which countenances schools having 83% black facul

ties.

In response to the inquiries of the Board, the district

court outlined some of the parameters of its notions of a

desegregated system, which included pro rata distribution

of teachers by race and that “all the black and predominately

black schools in the system are illegally segregated” (711a

and 714a). The district court further held that any plan

should seek to reach a 71-29 ratio so that one school would

not be racially different from the others though variations

may be unavoidable (710a). It is believed that the absolutes

of the district court’s legal position began to crystalize with

ttiê order of November 7, 1969.7 This has resulted in the

7In the order of November 7, 1969, and all subsequent orders,

namely, December 1, 1969, February 5, 1970, March 21, 1970 and

August 3, 1970, resulted in reversal of facts previously found in favor

of the Board and many inferences resolved against the Board together

with misconstruction of many of the facts presented to the court. The

Board attempted to correct many of the findings by Objections and

Exceptions thereto (1239a) and Objections and Exceptions to Findings

of Fact dated August 14, 1970.

15

failure of the court to make any subsequent findings fav

orable to the Board.

The district court then disapproved the Board’s plan for

further desegregation and directed desegregation of faculties

on a three-to-one ratio effective not later than September 1,

1970, and indicated that a court consultant would be ap

pointed. This was accomplished by order of the court dated

December 2, 1969, wherein the court appointed Dr. John

Finger as the court’s consultant, a witness who had prev

iously testified on two occasions for the plaintiffs and had

offered earlier desegregation plans. The order of December

1 did not suggest implementation of pupil desegregation

would be advanced to a date earlier than September 1, 1970.

The Board was invited to continue working on its plan (714a-

716a).

The Board submitted its completed plan on February 2,

1970 (726a). The plan utilized computers to achieve a maxi

mum racial mix of 71% white and 29% black in each school

where possible by restructuring attendance lines. One hun

dred (100) of the 103 schools would have a racial mix, leav

ing only three all-white schools. Sixty-eight per cent (68%)

of the black students would attend schools having less than

40% black population. Thirty-two per cent (32%) of the

black students would attend nine elementary and one junior

high schools which would have black ratios of 83% to 99%

under the Board plan (R. Br. A-4-6, A-10). This plan re

duced the number of blacks in predominately black schools

from 16,197 to 7,497 and the number of predominately

black schools from 22 to 10.

The plan for desegregation submitted by the Board in

cluded imposition of faculty ratios of approximately three-

to-one, white predominating, in each school and proposed

implementation of its plan for the school year 1970-71 in

accordance with the various court orders. The Board plan

would require the in-district transportation of approximately

5,000 additional students, who would qualify for such trans

portation under state law.

16

The court consultant’s plan was submitted contempora

neously with that of the Board on February 2, 1970, which

effectively adopted in many respects the Board’s geographic

zoning plan and engrafted upon it the features of pairing

of distant elementary schools and creation of satellite dis

tricts in predominately black inner-city areas whose stu

dents were assigned to distant predominately white outlying

secondary schools.

On February 2, 1970, the court conducted a hearing lim

ited solely to the question of time required for implemen

tation. It refused to hear any evidence with reference to the

merits of the two plans before the court. On February 4,

1970, the Board made a motion for hearing on its plan and

for the opportunity to examine the court consultant, who

resides in Rhode Island and beyond the process available

to the Board. In response thereto, the court permitted a

short hearing severely limited as to time on the following

day and declined to direct the consultant to be present for

examination. The Board was compelled to submit substan

tial evidence nunc pro tunc (848a-900a).

On the same day, February 5, 1970, the court entered

its order, in which the court found in part as follows:

The Board plan, prepared by the school staff, relies

almost entirely on geographic attendance zones, and

is tailored to the Board’s limiting specifications. It

leaves many schools segregated. The Finger plan

incorporates most of those parts of the Board plan

which achieve desegregation in particular districts by

rezoning; however, the Finger plan goes further and

produces desegregation in all the schools in the sys

tem.

Taken together, the plans provide adequate supple

ments to a final desegregation order (819a).

Although the court stated “the order which follows is not

based on any requirement of ‘racial balance’ . . .” (821a),

the court then adopted the entire plan of the court consul

tant and thereby directed racial balancing with reference to

the various schools:

17

A. The Board’s pupil assignment plan for senior high

schools was approved8 upon condition that 300 black stu

dents residing in four grids suggested by the court consultant

would attend Independence High School. Therefore, the

court consultant’s sole recommendation with reference to

high schools was approved, although no school under the

Board plan would house more than a 36% black ratio.

B. With respect to junior high schools, the Board plan

was approved9 10 upon condition that the only junior high

school out of 21 which would remain predominately black

would be desegregated by giving the Board a “Hobson’s

choice” of furnishing transportation and increasing blacks

in attendance at several outlying schools and in default of

rezoning (which had been fully explored), two-way trans

portation of students (which is cross bussing to which the

Board is opposed) or closing the junior high school (whose

classrooms are desperately needed to minimize the already

serious overcrowding which exists at the junior high level).

None of the alternatives were accepted. Therefore, the

Board was directed to implement the court consultant’s plan,

which provided for establishing nine satellite attendance dis

tricts (containing 2,760 students) in inner-city black areas

for attendance at nine distant predominately white suburban

schools.

C. With respect to elementary schools, the court adopted

the court consultant’s plan which utilized the Board’s rezon

ing'0 and engrafted upon it the features of pairing and group

ing nine inner-city black schools with 24 suburban white

8The Board plan for senior high schools eliminated the one all black

senior high school, West Charlotte, and established black ratios of 17%

to 36% for nine of the ten schools. The remaining school, Independ

ence, would house a 2% black ratio. (748a).

9The Board plan for junior high schools eliminated four of the five

predominately black schools and the remaining school, Piedmont,

would have a 90% black ratio or 758 black students (747a).

10The Board plan reduced the number of predominately black

elementary schools from 17 to 9 (744a-746a).

18

schools, thereby necessitating extensive cross-bussing.11 Ap

proximately 10,300 students would be involved in the ele

mentary cross assignments.

The Board plan contemplated transporting only those stu

dents eligible for transportation under state law which would

result in furnishing additional transportation to approxi

mately 5,000 students (871a-875a). The order of desegre

gation imposed substantial additional transportation require

ments upon the school system (880a-884a) which were

compiled by the transportation office of the school sys

tem as follows:

Finger Plan

Additional Students No. of Buses

23,000 526

First Year Cost

$4,199,439.00

Board Plan

Additional Students No. of Buses First Year Cost

4,935 104 $ 864,767.00

Supplementary findings of the court dated March 21,

1970, (1217a-l 219a) reflect a finding that transportation as

ordered by the court would show the following totals:

Court Estimates

Additional Students No. of Buses First Year Cost

13,300 138 $1,011,200.0012

11 The Board transportation office estimated these students would

travel fifteen miles each way per day (860a). The district court esti

mated the school to school distance at seven miles (1261a).

12The district court found that the cost of 138 buses would be

$743,200.00. The annual operating cost of $532,000.00 was reduced

by one-half in its order of April 3, 1970 (1259a), resulting in a total of

$1,011,200. The district court amended its February 5 order by order

dated March 3, 1970 (921a) to provide that transportation should be

offered only to those city students who lived in an area which had

been rezoned as a result of the court order. The Board accordingly

submitted revised estimates which reduced the requirements for addi

19

Extensive objections and exceptions (1239a) were filed by

the Board with reference to the findings of the district court

dated March 21, 1970, and the Court of Appeals noted that

it was difficult to furnish reliable predictions with respect

to transportation estimates (1271a).

On appeal, the Court of Appeals approved the provisions

of the order of the district court with reference to assign

ment of faculty and assignment of students to secondary

schools and reversed and remanded for further considera

tion the assignment of pupils attending elementary schools

(1262a). In doing so the Court of Appeals noted that the

voluntary faculty desegregation of the Board was in com

pliance with other orders of that court (1 263a). The find

ing of the district court with reference to residential pat

terns leading to segregation resulting from federal, state and

local government action was affirmed on “familiar principles

of appellate review.”13

tional transportation to 19,285 students and 422 buses at a first year

cost of $3,406,687.00. Thereafter, State Board of Education, pursuant

to Sparrow v. Gill, 304 F. Supp. 86 (MDNC 1969) authorized trans

portation of all city students residing a mile and a half from their

school. Accordingly, this reinstated the original estimates of the local

transportation staff.

13In view of the importance of other issues in this case, the Board

does not deem it appropriate to fully controvert the very shallow and

incompetent evidence upon which the district court’s findings were

made on November 7 reversing its prior findings without benefit of

further evidence or hearing. We would point out several areas. With

respect to racial restrictive covenants, the only evidence was a 1946

North Carolina Supreme Court case enforcing such restrictions. Other

evidence of racial restrictions or the extent thereof is absent from the

record. Blacks have for many years purchased homes in predominately

white neighborhoods. Plaintiffs’ evidence (31 a-34a) discloses that rela

tively small black areas have taken over large white communities. As

a result, blacks predominated in 11 former all white schools (591a).

Although older black and white neighborhoods were zoned industrial

in 1947, no substantial inroads were made in these neighborhoods by

industry (254a), industrial zoning in residential areas was substantially

curtailed (254a) and existing zoning generally follows existing land use

(261a). Urban redevelopment assisted the displaced persons in finding

20

The reforms the Board undertook to create a unitary

school system were applauded by the Court of Appeals

(1265a). Noting the district court’s holding “that the Board

must integrate the student body of every school” (1266a)

the Court of Appeals gave a partial answer to the unitary

school question in holding:

. . . first, that not every school in a unitary system

need be integrated; second, nevertheless, school

boards must use all reasonable means to integrate

the schools in their jurisdiction; and third, if black

residential areas are so large that not all schools can

be integrated by using reasonable means, the school

boards must take further steps to assure that pupils

are not excluded from integrated schools on the basis

of race . . . (1267a).

The Court of Appeals thereupon adopted . . the test of

reasonableness—instead of one that calls for absolutes—be

cause it has proved to be a reliable guide in other areas of

the law . . (1267a).

Although Piedmont Junior High School was a formerly all

white facility, and nearly all white in 1965 (25 blacks)

(691a), the Court of Appeals noted that this school was now

in the heart of the black residential area (1268a), a school

which could not be desegregated by rezoning. This school

precipitated the creation of nine satellite junior high school

districts for the purpose of eliminating this one predomi

nately black junior high school.

new homes but had no power to direct the location to which they

moved (265a). Furthermore, there is no evidence that any citizen was

so directed. Many other examples could be cited.

It is noted the findings of the district court, although largely unsup

ported, closely parallel those of the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights

with respect to separation of races in 75 representative cities scattered

throughout this nation. Racial Isolation in the Public Schools-

Summary> Report by the Commission on Civil Rights (1967).

21

The Court of Appeals, utilizing the district court’s un

realistic transportation estimates, found its approval of the

secondary portion of the desegregation plan precluded ap

proval of the elementary plan. The combined plans would

represent a 56% increase in pupils transported and the num

ber of buses would be increased by 49%. The Circuit Court

acknowledged that the Board . . should not be required

to undertake such extensive additional busing to discharge

its obligation to create a unitary school system.” (1276a).

The Court of Appeals thereupon vacated the judgment of

the district court and remanded “. . . the case for reconsidera

tion of the assignment of pupils in the elementary schools,

and for adjustments, if any, that this may require in plans

for the junior and senior high schools.” (1277a).

On remand, the district court had before it five elemen

tary, two junior and two senior high school plans. An under

standing of these plans will be facilitated by reviewing the

separate map appendix to this brief.

Pursuant to the suggestion of the Court of Appeals, the

Board met with representatives of HEW and sought to par

ticipate in the development of a new desegregation plan.

Although the Department of Health, Education and Wel

fare obtained from the Board all the information it desired,

it refused to accept the Board offers to assist it in develop

ing a plan (Tr. 197, July 15, 1970). Nevertheless, the Board

reconsidered all the techniques of desegregation in an effort

to develop a new plan (Tr. 10-20, July 15, 1970). After

presentation ot the HEW plan on June 26, it was reviewed

by the Board and rejected by a unanimous vote. Neverthe

less, the Board presented the HEW plan to the district court

for its consideration.

A hearing was convened on July 15, 1970, at which time

the district court again reviewed the February 2, 1970 Board

plan and the February 5, 1970 court approved Finger plan.

The district judge also considered the HEW plan, a plan pre

pared by minority of Board members, and an earlier draft

of a plan considered by the court consultant.

22

The Board and court approved plans have been described

earlier herein.

The HEW plan’s salient features involved utilization of

the Board restructured lines and then clustering a group of

school districts contiguous to each other for specialized grade

assignment to a particular school, for instance, one school

might house grades 1 and 2, a second school grade 3, etc.

Many of the districts involved in these clusters were desegre

gated by the Board’s rezoning.14

A four-member minority of the Board presented an ele

mentary plan which utilized the 1969-70 school zones,

grouped 72 elementary schools within eighteen separate clus

ters, many of which were far removed from each other. The

court’s attention is invited to the map (R. Map Appendix),

which gives a clear picture of what this plan does to the

elementary schools of the Charlotte-Mecklenburg system.

It was an obvious successful attempt at racial balancing, as

all 72 elementary schools would house black ratios ranging

from 27% to 34%. Students chosen for attendance outside

their district would be selected on a lottery basis. (R. Ex.

45, July 15, 1970). Dislocations and transportation require

ments were essentially equivalent to those of the court or

dered Finger plan (Order, August 3, 1970).

Petitioners, calling Dr. Finger as their witness, had him un

veil a draft of a preliminary plan previously prepared by

him. Basically, the plan was Dr. Finger’s attempt to restruc

ture attendance zones. Finding his rezoning attempts left

14Cluster or zone number IV of the HEW plan grouped all white

Pinewood, nearly all black Marie Davis with Sedgefield (38% black)

and Collinswood (33% black). This plan was roundly condemned for

the reason that an elementary student in such a zone would attend

four elementary schools in six years and it interfered with the educa

tional programs and organizations of the school system. It also

involved substantial transportation and utilized many schools that

already had the approximate racial ratio of the entire system. Most of

the groupings were near-black or predominately black (R. Ex. 1 and 2,

July 15, 1970).

23

approximately 6,800 black elementary school children in

inner-city black schools (Tr. 264, July 15, 1970), he then

developed walk-in attendance zones for black students at

those schools who would comprise approximately 30% of

the capacity of the school. The blacks would attend these

schools for six years. Whites residing generally in the inner

perimeter of the city limits would be transported to such

schools. Blacks who were not assigned to the inner city

schools would be transported for six years to suburban white

schools. The grade structure of the suburban schools was

rearranged on a 3-3 basis with grades 1 - 3 in one school and

a school in a contiguous area would have grades 4 - 6. Stu

dents in the contiguous zones would attend these two schools

along with blacks from the inner city schools. Dr. Finger

admitted the plan was incomplete (Tr. 263, July 15, 1970)

and contains a complex grade structure (Tr. 258, July 15,

1970). The enormous amount of dislocation and transpor

tation is apparent. As the district court found:

26. All plans which desegregate all the schools will re

quire transporting approximately the same number

of children. In overall cost, if a zone pupil assign

ment method is adopted, the minority Board plan

may be a little cheaper than the Finger plan. (Order,

August 3, 1970).

The district court characterized three of the plans as “rea

sonable” : the court ordered (Finger) plan, the minority

board plan and the earlier draft of a Finger plan. The Board

was given the “option” of adopting any one of these plans

for the elementary schools. The Board met and found the

three alternate plans to be unreasonable and the court or

dered (Finger) plan was thereupon imposed by order of

August 7, 1970.

The Board filed notice of appeal to the Court of Appeals

for the Fourth Circuit on August 14, 1970, and has made

application to this Court for permission to supplement the

record or, in the alternative, that the motion be considered

as a writ of certiorari to the Court of Appeals for the Fourth

Circuit pursuant to Rule 20 of the Rules of the Supreme

Court. No action has been taken thereon at this writing.

24

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

Both the district court and the Fourth Circuit have mis

applied the Constitutional imperatives of Brown I, Brown II

and Green as they apply to the Charlotte-Mecklenburg

schools. In doing so, both of these Courts erred in disapprov

ing the Board plan and imposing upon this System require

ments that are unlawful and unwarranted by the facts in this

case.

The basic error stems from the misconception of the rights

guaranteed black and white children by the Fourteenth

Amendment and the goal to be achieved by a dismantling

of a dual system and the establishment of a unitary one.

Although disclaiming any intent to require racial balancing,

the orders imposed upon the Charlotte-Mecklenburg System

are based upon the proposition that student assignments at

each school must be fashioned in a manner which will achieve

or approximate the 70% white - 30% black racial ratio of

the system at large. This false premise in turn is founded

on the erroneous notion that each black or white child has

an individual guaranteed right to attend a school having the

prescribed racial mix. Any fair interpretation of the orders

of the trial judge point unerringly to the conclusion that he

deemed that presumed right to be an absolute one that can

not be diluted or denied by reason of circumstances, costs,

disruptions or educational or administrative considerations.

Tacitly, the Circuit Court also espoused racial balancing as

its goal—but sought unsuccessfully to temper the absolutism

of the district court with a test of reasonableness, to which

on remand the trial judge gave only thinly veiled lip service.

The Board is in general agreement with the employment of

a Rule of Reason in appraising desegregation plans. But in

this case, the Fourth Circuit misapplied its own Rule of

Reason and in effect the district court ignored it. Racial

balancing is not required by the Constitution and when im

posed by a court violates the prohibitions of the Civil Rights

Act of 1964.

25

Contrary to these erroneous views, the pronouncements of

this Court make it clear that the guaranteed right of a child

is to attend a school system within which discrimination

originating from the old state-imposed dualty has been eli

minated. If such discrimination has been eradicated and if

schools are fairly operated and administered on a nonracial

basis, a dual system has been dismantled and a unitary one

has been established within which no child is excluded be

cause of his race or color. Nondiscriminatory geographic

attendance zones, including those promoting the neighbor

hood school concept, establish a unitary system-notwith-

standing a residue of predominately black schools that remain

for reasons totally unrelated to race.

A corollary to the requirement of racial balancing is the

burden of massive bussing and dislocation of children to

achieve the goal of 70% white-30% black ratio in the

schools of the Charlotte-Mecklenburg System. This balancing

and the bussing to implement it impinges upon the Constitu

tional rights of children, both black and white, who may

not wish to be assigned and moved out of their neighbor

hood attendance zones for the sole purpose of promoting

the presumed rights of other children.

The February 2, 1970, Board plan is based on geographic

attendance zones that were drastically gerrymandered to

promote desegregation. This plan severely strains, but main

tains the basic benefits of the neighborhood school concept.

By this technique, the Board satisfactorily desegregated all

but 10 of its 103 schools. All but a small handfull of the

black children who remain in these 10 schools will have a

desegregated school experience for at least one-half of their

12 years of schooling. The Board itself sought to achieve in

as many schools as possible a maximum racial mix. By doing

so, the Board proposal exceeds Constitutional imperatives.

The compulsion of court orders cannot be employed to

coerce a school system to do what the Constitution does

not require.

26

The Board plan is reinforced by majority to minority trans

fers to promote stable desegregation, prevent resegregation

and afford blacks that remain in the 10 predominately black

schools an opportunity to attend a predominately white

school with free transportation to accomplish the move.

The teachers at each school are assigned on a ratio of 3 to 1

which is the ratio of white to black teachers in the system.

The staff, extra-curricular activities, transportation, facilities,

programs and other facets of the system are nondiscrimina-

tory and thoroughly desegregated, and are employed to pro

mote integration throughout the system.

The Board plan effectively establishes a unitary system.

Both the district court and the Fourth Circuit erred in dis

approving that plan and supplanting it with one or more

alternatives designed to racially balance each school, with

the consequent bussing and movement of children that the

Board considered unnecessary, impractical, costly, disruptive,

educationally unsound and not required by the Constitution.

ARGUMENT

I. GENERAL DISCUSSION OF CONSTITUTIONAL PROB

LEMS AND CONCEPTS.

A. A CHILD S CONSTITUTIONAL RIGHT GUARAN

TEED BY THE FOURTEENTH AMENDMENT IS TO

GO TO SCHOOL IN A UNITARY SYSTEM. IF THE

SCHOOL IS PART OF SUCH A SYSTEM, HE HAS

BEEN ACCORDED THAT RIGHT.

It is unarguable that the negro and white children in the

Charlotte-Mecklenburg system must be and will be accorded

their Constitutional rights in full measure. However, the dis

trict court’s misconception of the nature of those rights is

succinctly stated in its August 3, 1970, Order (Pets’ Br. Al):

The issue is not the validity of a “system”, but the

rights of individual people.

Of course, the Constitutional rights of a black or white child

under the Fourteenth Amendment are individual and per-

27

sonal, but the question remains: What is the essence of that

right—the right to do what? The trial judge concludes that

the right is an absolute one of each child to be in a desegre

gated school and presumably in a desegregated classroom

within the school—regardless of the rights of white children,

circumstances, problems peculiar to urban areas, costs, dis

ruptions, educational considerations and other factors which

prevent a color blind school system from achieving the ideal

racial mix in every one of its schools.

This view does not comport with the previous declarations

of this Court. Briefly stated, it is our understanding that

this Court has defined the right guaranteed a negro or white

child by the Fourteenth Amendment as being the right to

attend a school in a system where no state-imposed discrim

ination exists and has prescribed the attendant affirmative

duty of a school board to establish such a system. This right

and duty are summarized in Green v. New Kent County,

391 U.S. 430 (1968):

[I ] t was such dual systems that 14 years ago Brown I

held unconstitutional and a year later Brown II held

must be abolished; school boards operating such

school systems were required by Brown II “to effec

tuate a transition to a racially nondiscriminatory

school system” . . . Id. at 435. (Emphasis added)

. . . Brown II commanded the abolition of such dual

systems . . . Id. at 437. (Emphasis added)

School boards such as the respondent then operat

ing State-compelled dual systems were nevertheless

clearly charged with the affirmative duty . . . to con

vert to a unitary system in which racial discrimina

tion would be eliminated root and branch . . . The

constitutional rights of Negro school children ar

ticulated in Brown I permit no less than this . . . Id.

at 437-38 (Emphasis added)

The thrust of Brown v. Board o f Education, 347 U.S.

483 (1954) and Brown v. Board o f Education, 349 U.S. 294

(1955) and all that this Court has said since those landmark

decisions point unerringly to the validity of this proposition:

28

State-imposed dual systems must be abolished and must be

replaced with unitary systems. The Constitution does not

guarantee to a child the right to attend a school having any

particular racial complexion. The Fourteenth Amendment

secures for him only the privilege to attend a school that is

part of a unitary system which is comprised of “just schools”

{Green, supra, at 442)—schools that are operated and ad

ministered without any vestige of discrimination. Once a

conversion or transformation to a unitary nondiscriminatory

system has been accomplished, every child in that system

has been accorded his rights. Those who contend for a par

ticular racial mix or balance in each school propose a per

version of the commands of Brown I and II and Green.

It is by these standards that the plan of the School Board

in this case must be judged. An analysis of that plan clearly

demonstrates that it realistically will achieve the nondis

criminatory unitary system the Constitution requires. The

oppressive plan of the district court does not conform with

these standards. In spite of disclaimers, its objective is the

racial balancing of each one of the schools of the Charlotte-

Mecklenburg system.

B. A UNITARY SYSTEM IS ONE WITHIN WHICH NO

CHILD IS EXCLUDED FROM ANY SCHOOL BE

CAUSE OF RACE. IF A DESEGREGATION PLAN

PROMISES REALISTICALLY TO ACCOMPLISH THIS,

IT IS CONSTITUTIONALLY ACCEPTABLE NOT

WITHSTANDING A RESIDUE OF PREDOMINATELY

BLACK OR WHITE SCHOOLS THAT REMAIN FOR

REASONS UNRELATED TO RACE.

The now familiar definition of a unitary system is one

“within which no person is to be effectively excluded from

any school because of race or color.” Alexander v. Holmes,

396 U.S. 19 (1969); Northcross v. Board o f Education (Bur

ger, Chief Justice, concurring opinion) 397 U.S. 232 (1970).

Unhappily for school boards charged with the responsibility

of fashioning a unitary system, this definition only begins,

29

not ends, inquiry regarding the necessary ingredients and

characteristics of a unitary system.

This Court is well aware of the diversity and change of

opinion both among and within courts that have been wrest

ling with the scope and meaning of this definition. This

ought not to be. We hope this Court will find an oppor

tunity in this case to put some meat on the bare bones of

this definition which will give instruction and guidance to

school boards and will help dispel the disparity that pres

ently characterizes the findings of fact, conclusions and

opinions of the lower courts.

Brown I and II. the Green triad and Alexander v. Holmes

are of some help—but not much for practical application

“in the field.” From these cases, we understand a unitary

system to have at least these attributes: it is “nonracial.”

It is “racially nondiscriminatory.” It is what is left after

a “well-entrenched dual system” has been “dismantled.” It

is one in which “racial discrimination” is “eliminated root

and branch.” It is one within which no child is “effectively

excluded because of race or color.” Running through all

of these criteria is one common theme: If a system is es

tablished that does not discriminate against the race of a

child and thereafter operates on a color blind basis, a former

dual system has been transformed, converted and, we pre

sume, purged.

It is worth noting that the 2-school rural residentially

mixed New Kent County involved in Green typifies the sys

tems stricken down by Brown I and II, a fact which is spe

cially commented upon at page 435:

The pattern of separate “white” and “Negro” schools

in the New Kent County school system established

under the compulsion of state laws is precisely the

pattern of segregation to which Brown I and Brown II

were particularly addressed, and which Brown 1 de

clared unconstitutionally denied Negro school child

ren equal protection of the laws. Racial identification

of the system’s schools was complete, extending not

just to the composition of student bodies at the two

30

schools but to every facet of school operations—

faculty, staff, transportation, extracurricular activi

ties and facilities. In short, the State, acting through

the local school board and school officials, organized

and operated a dual system, part “white” and part

“negro.”

It was such dual systems that 14 years ago Brown I

held unconstitutional and a year later Brown II held

must be abolished; school boards operating such

school systems were required by Brown II “to ef

fectuate a transition to a racially nondiscriminatory

school system.” 349 U.S. at 301,75 S.Ct. at 756.

The Green triology formed the primary vehicle for the last

detailed pronouncements of this Court concerning some of

the characteristics of a dual and non-dual system. The fac

tual context within which the teachings of Green were made

presents considerable difficulties when these guides are ap

plied to a complex urban system like Charlotte-Mecklenburg—

particularly when that system has long since abandoned

the discriminatory practices that were so flagrantly involved

in New Kent County.

In identifying a unitary system, the Alexander v. Holmes

definition embodies two basic aspects: (1) effective exclu

sion and (2) the reason for exclusion—i.e. because of race.

The word “exclude” means to shut out. It implies keep

ing out hwat is already outside. That a person remains out

side does not necessarily mean that he is excluded. The

idea of shutting out suggests affirmative action on the part

of someone to accomplish the exclusion. If a person out

side is afforded an opportunity to come inside, he is not

barred or excluded. This opportunity must be a reasonable

one. If the opportunity accorded a person is unreasonable,

he may be said to be effectively excluded.