Brown v Board of Education of Topeka Arguments and Rebuttals

Public Court Documents

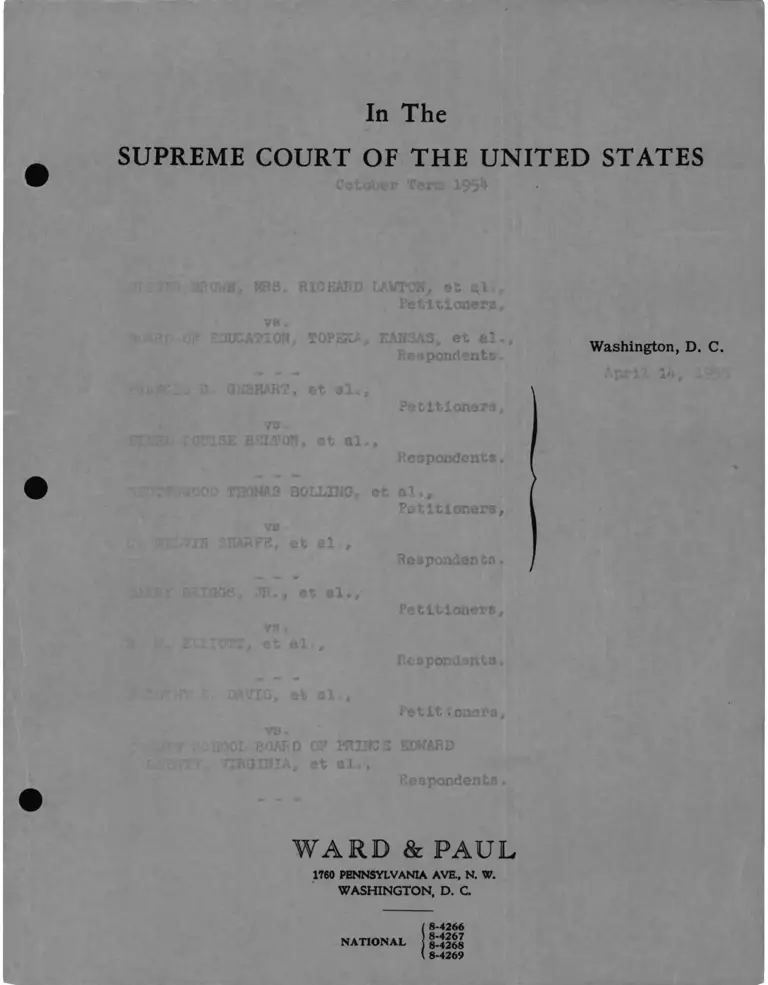

April 14, 1955

49 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Brown v Board of Education of Topeka Arguments and Rebuttals, 1955. 3e2307e8-b69a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/6e9d30e0-e943-427c-b792-25ab939251f4/brown-v-board-of-education-of-topeka-arguments-and-rebuttals. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Copied!

In The

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

October Term

OWN, MBS, RICHARD LAWTON; et 1̂.*Petitioners,

VB i

DUG AT I OR, TOPEKA, KANSAS, et ai.

Respondents.

GE8HART, et al.,

Petitioners,

V9 ,

SE BELTON, et al.,

Respondents.

THOMAS BOLLING, et al

Patitloners,

vs

SHARPE, et al ■ ,

Respondents.

G3, JR,, et al.,

Petitioners,

vs •

Respondents.

DAVIS, et al.,

Petit toners,

iOOL BOARD ON PRINCE EDWARD

VIRGINIA., at alt,

Respondents.

Washington, D. C

April Ik,

W A R D & PAUL

1760 PENNSYLVANIA AVE., N. W.

WASHINGTON, D. C.

NATIONAL

8-4266

8-4267

8-4268

8-4269

bdkQ CONTENTS Page

ARGUMENT ON BEHALF OF THE UNITED STATES

GOVERNMENT

By Mr*. Simon E. Sob el off

REBUTTAL ARGUMENT ON BEHALF OF HARRY BRIGGS

ET AL

By Mr. Thurgood Marshall

REBUTTAL ARGUMENT ON BEHALF OF PRINCE EDWARD

COUNTY, VA.

By Mr. Almond 4 3 9

Goldstein

bdl

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE, UNITED STATES

OCTOBER TERM, 1954

394

OLIVER BROWN, MRS. RICHARD LAWTON, ET AL

vs

BOARD OF EDUCATION, TOPEKA, KANSAS, ET AL

Cane No * 1

FRANCIS B, GEBHART, E'T AL

V3 .

ETHEL LOUISE BELTON, ET AL

SPOTTSWOOD THOMAS BOLLING, ET AL

C. MELVIN SHARPE, ET AL.

HARRY BRIGGS, JR., ET AL,

vs.

R„ W. ELLIOTT, ET AL

DOROTHY E. DA'/ICS, ET AL

vs.

COUNTY SCHOOL BOARD OF PRINCE EDWARD

COUNTY, VIRGINIA, ET AL.

Case No. 5

Case No. 4

Case No. 2

Case No. 3

Washington, D, C.

April 14, 1955

P R O C E E D I N G S 12:02 p.m.

395

The Chief Justice: Mr. Solicitor General, will you

proceed, please?

ARGUMENT on behalf of the united states

G OVBRNMBNT {Re s urned)

BY: SIMON E. SOBELOFF

Mr. Sobeloff: If it please the Court, my attention

has been called to the answer I gave to a question by Mr.

Justice Minton.

Mr. justice Minton asked me, "Would you put a deadline

In at all," and I replied, "I don3t think I would put a deadline

in the more complicated situations."

That answer is not clear. What I wanted to say

is that I would not have the Supreme Court put In any deadline.

I thought that the whole tenor of my argument yesterday was

that; there should be no opened orders by the District Courts,

that they should have deadlines but with freedom in proper

cases on a proper showing of facts requiring further time tc

grant further time.

Justice Reed: You mean you would start with a dead

line?

Mr. Sobeloff: I would start with a deadline first as

to the requirement — we suggest 90 days for a plan to be sub

mitted.

Are you now speaking of tileJu,voice I"rankfurter:

396

bd3 decree to be entered by this Court —

Mr. Sobeloff: No, sir.

Justice Frankfurter: -- or by the District Court?

Mr. Sobeloff: What I said in answer to Mr. Justice

Minton applies to the decree of this Court. 1 would not attempt

the deadline in the decree of this Court.

Justice Frankfurter: So I understand. But I am wonder

ing considering the reasons that make that undesirable for this

Court to fix a deadline, the reasons that compel remission to the

District Court to formulate a more detailed decree, whether we

should be here considering what deadline the District Court

should have, Are we not anticipating the very consideration

that would urge a deadline?

Mr. Sobeloff: I don»t think you ought to tie the hands

of the District Judge but I think it would be useful to the

District Judge if you were able to say to ohe parties, I am

required to ask you,to require you,to produce a plan within 90

days.

See what you can do in the 90 days. If anybody comes

before me and shows that there has been a good faith attempt to

produce the plan but cannot be done within the time limit, I

will entertain an application for further time.

There is the merit of requiring motion. That is also

the saving grace of not tying people to a time limit that may

prove in actuality unworkable.

397

bd4 Justice Frankfurter*: There are various ways of suggest

ing motion without being explicit about it.

Mr. Sobeloff: If the Court can devise any way that would

suggest motion and require motion and encourage motion and

without, however, restricting unduly that discretion which

is necessary in the administration of this business, that is the

thing that the Government would lilce to see.

Justice Frankfurter: The point of my remark is that

the wisdom which directs you to suggest this Court should

not go into certain definitiveness or peculiarities is the

wisdom that ,for me at least, carries beyond guessing what

actualities and definitiveness the District Court should go

into.

Mr. Sobeloff: On the other hand the District Judges

might appreciate some indication of a tentative limit with the

knowledge that on a showing to them of the necessity for more

time they can grant more time.

I think it is arguable and may work differently in dif

ferent situations but in general I think two things are to be

avoided.

One, a fixed and inflexible limitation. On the other,

no limitation at all.

I think that while this Court does not fix the time, the

District Courts ought to be required to fix some time in the

knowledge that they can,on a proper showing grant more time.

398

bd5 but the thins ought not to be left hanging in the air

indefinitely.

The Chief Justice: Mr. Solicitor General, this may be

an appropriate time for me to a sic if you would be willing to

prepare a proposal for a decree as the other parties have,. It

would be helpful to the Court if you would do that.

Mr. Sobeloff: We will be very glad to do whatever the

Court thinks would be helpful, I want to call attention to

the fact that on pages 27 and forward from that point in that

brief, we have with particularity set forth provisions which

we think appropriate for the decree.

All that would be required would be the formulation of

the words, It is hereby decreed and the provisions themselves are

set forth.

The Chief Justice: Thank you.

Justice Frankfurter: Plus such further thoughts

as you may have had since November 24, 1954.

Mr. Sobeloff: Yes, sir.

Justice Harlan: For example, your item 1, Mr.

Sobeloff, on page 27 is a fixed deadline of 90 days. I take it

you are now suggesting flexibility there?

Mr. Sobeloff: Yea. Elswhere we do speak of giving the

court discretion to give further time but if that leaves in

doubt the right of the Judge to do that, that doubt ought to

be resolved now, and there are two other matters that will not

399

bd.6 detain me very long that I should lilce to mention before

I come to the question that the Chief Justice asked as we were —

and others — as we were about to adjourn.

First, with regard to the time limit for the

execution of a plan not for the formulation of the plan —

my attention has been called to the fact that in the Govern

ment's brief in last year, that is in 1953j it was

suggested that one year should be allowed, whereas in the

present brief we do not make that recommendation.

The inconsistency is more apparent than real because

even in the 1953 brief, where one year was suggested, It

was stated that it should be one year plus such other iime as cn

a proper showing may be found necessary.

The important thing, whatever the Court does is to make

it clear to the lower courts and to the parties that there

must be a bona fide advance toward the goal of desegregation.

That doesn't mean that people ought to be ridden over roughshod;

it doesn't mean that conditions ought to be ignored.

Adjustments have to be made and albwanee should be

made for the time. Time ought to be allowed for those

adjustments, But it does not mean that the matter ought co

be left hanging in the air. And it is bett'jeen these two

extremes that we think that the Court should go and because of

the familiarity of the lower courts with their particular

conditions we think that the time limits can best be sec share,

400

bd7 If, however, this Court thinks it would be wiser to

suggest one year, with the opportunity on proper application

for an extension, we have no objection to that,

Nov;, another detail that has not been mentioned in any

of the discussions but is proposed in our brief that in a

very hypothetical way we say that the Court may wish to •

appoint a special master to reviev; such reports, that is the

reports which will periodically be required of the lower courts

to this court and to make appropriate recommendations through

to this court and to the lower courts.

Now, we are not recommending that a master be appointed

to take testimony.

We are net recommending that he function as a direc

tor over the local school authorities„

We have in mind that the volume of these reports may

be such that this Court could not effectively deal with them and

this ourt m ght find it desirable to have someone who w!13

receive these reports, digest them, present the essence of them to

this (purt for consideration and from time to time perhaps

consult with the lower courts and impart to the judges the

reactions of this Court and the suggestions and recommendations,

because these things can perhaps be handled better by

that informal method than by a series of decrees.

Justice Reed: Do I correctly understand then that

this Court is to retain these present cases here?

401

bd8 Mr. Sobeloff: Yes, sir.

Justice Reed: And what is then to be sent to the

District Court?

Mr. Sobeloff: It sends the cases back, to the

District Court for the further proceedings for the framing of

decree.

Justice Reecl: Then the cases can be in two courts at

the same time?

Mr. Sobeloff: The court can send that back and yet

retain jurisdiction for future purposes if conditions

arise that make it, in the discretion of this Court,

necessary to intervene, to give direction, you could still do

it.

I see no Inconsistency between that and these further

proceedings in the formulation of decrees.

Justice Clark: Did we do that in the Terry Adams

case? That is the election case down in Texas a few terms ago.

Mr. Sobeloff: I donJt know. I am not familiar with the

situation there. I think it would be a very wholesome thing for

this Court to do, so anybody who has the occasion to see a

more specific direction from this court could do it and it would

not involve the delay of starting all over again.

Now, with regard to the question — I may add in

respect to this master that our view is that he should not be

■ cpected or perhaps not even be permitted to volunteer

402

bd9 suggestions and certainly give orders to the parties though

he perhaps should be permitted if called on to advise.

There may be certain plans that are under consider

ation which an educational unit, school board, might be In

doubt about.

They may want to know what is being done in other

Jurisdictions. This inaster would be in a position to give

them valuable information.

In that spirit rather than the imposition of a command

from him;, he might be able to render valuable service.

Now on the question of the class action, of coarse, the

concern of the United States in this case is net primarily

with a few individuals.

The importance that attaches to these cases is because

we all realise that we are dealing here,nobtwwtbhnn&mdd

plaintiffs alone and not even with individuals who, by any

interpretation of the rule, might be regarded as members of

the class in the particular case.

Vie are dealing here with great populations, both white and

regro. It is an important principle.

Sc it is not the fate of a handful that is involved

here.

The question is what is the procedure to be followed in

resolving a much larger problem.

New it seems to us that this massive litigation

403

bdlO which has taken a number of years already would be ineffectual if

the effect were limited to a few.

We think that the Court could at least embrace within its

decree more than the named plantiffs but members of the classes in

those communities who are in the same situation as the named

plaintiffs and of course the effect under the doctrine

those cases would have upon other future cases is obvious*

Prom the standpoint of the plaintiff, it would seem

to me that the admission of a few might disappoint what they are

really after. From the standpoint of the defendants too I don!t

think that they would consider that this case was as vital as

they do consider it if they thought it would only affect a few.

But if this Court should not take the view which I am abo\

to elaborate as to the class nature of these actions,

if you should decide that these are not class suits and that

your relief has to be limited to the few, then neither side can

have that both ways. On the one hand the plaintiffs can1t

expect that the decree will run in favor of people who are not

before the court *

On the other hand, the defendants, if they insist that

the decree can only affect a few, can1t say that the rights

of those few shall not be fully adjudicated because there may be

others that will be affected.

On the other hand, if you take the view that this

case for instance the case in South Carolina, involves only

belli 11 high school students and not a greater number and

it seems to rr© to be consistent, you can't say these people

ought to have their rights postponed, because there may be

others.

Either you take into account the others and ask the

District Court to consider the whole group or if you take the oppo

site view and say we are only going to consider the 11 who are

named plaintiffs then you have to give them, it seems to me, "che

rights which the decision of May 17 entitles them to have.

Justice Black*. If that should foe done, would there be

any possible necessity of the machinery which you suggested,

which would fee pretty large, of having masters and reports from

all over the country?

Mr. Sofoeloffs If you should take that view and

terminate the suits in that way, I don’t think you would have to do

any more. But there might foe the danger of a volume of

litigation that could perhaps,if you take the other view, be aver

404

ted.

Justice Black: What view is that?

Mr. Sofoeloff: If you take the class action you don’t

have to have new suits. These other people can have their

rights determined in these very proceedings.

Justice Black: Beyond the Clarendon District?

Mr. Sobeloff; Obviously no, Under no view of the

class action rule can people in other districts be affected,

405

bdl2 either entitled to relief or bound by the proceedings in these

cases.

Justice Black: Then, even then litigation would

continue, would it not, in other parts of the country?

Mr, Sobeloff: It might. Although as I say, that the

prestige of this Court is such that people will be disposed to

abide by the law and not invent spurious reasons for delay.

Justice Blacks Do you think they would be any less in

clined to abide by that if there was a direct immediate order

that these Individuals should be admitted in these schools and

nothing more?

Mr*. Sobeloff: I donJt think I know that they would

be less disposed to obey, but you would be settling a much

narrower question.

Perhaps from one point of view, that is desirable.

But I think both sides want to have the situation settled in the

light of these administrative problems, which they say

and which we all recognize will happen if a great number will

apply.

So far as these few are concerned, the problem may be

resolved without great administrative difficulty. But what

happens tomorrow?

The problem may come up In a milder form. I don3t

know. My guess is not any better than any other man93 about

that,

406

bdl3 All I am suggesting to the court is that if you

should take the view contrary to what I suggested yesterday that

these are class actions, and that other people in Clarendon

County besides the named plaintiffs are to be entitled to the

relief under the decree„

If you take the view that only the 11 are before the Court

then it wculi not be consistent to say that these 11 should not have

their constitutional rights because administrative problems may

arise in the future with respect to plaintiffs who have not

yet declared themselves and have not yet been intervened.

Justice Harlan: On the other hand., there would be no

reason for delay as far as these plaintiffs are concerned,

in that view?

Mr. Sobeloff: Net in that view. If you take that

view in the nature of these actions.

Justice Douglas: The question of the XI might not raise

administrative problems„

Mr, Sobeloff: That is right. At what point it is

simple and raises no administrative difficulty, nobody can say

abstractly. You would have to examine the record and

satisfy yourself whether or not you can pass a fair judgment on

this record.

Justice Clark: VJliat happens to the other 2500?

Mr. Sobeloff; That is just it. If it is a class

action, then the 2500 are all considered as part of the class

407

%

bdl4 Justice Clark: I mean., assuming it is not. You

say there are only 11. Originally it was 31 but now there are

il to consider,

Mr, Sobeloff: If you consider the rights of the 11 in

this individual action, the rights of the 11 are adjudicated.

They get their relief. The1 others may or may not

intervene in this case according to the rule I will discuss

presently or they will have to start new actions.

Generally that has been held. This Court has never

passed on this question but the lower court decisions generally

hold that there can be intervention at any time before judgment.

There is one case that goes even further and says that a person

who is covered, who is included in the class although not named

as a plaintiff ean come in and claim his relief, even after judg

ment .

s.,n~..s Theirs would be cases in which such a person came

in and demanded a citation for contempt against the plaintiff

for not complying with the Courtjs injunction although he had not

theretofore declared himself and intervened as a plaintiff.

Justice Clark: Do you have a brief on this problem?

Mr. Sobeloff: We will be very glad to submit a brief

to the Court.

Justice Harlan: The Fourth Circuit has even gone

further. They have held you can have a class action without

intervening at all.

4QS

bd!5 Mr, Sobeloff: In what- case is that?

Justice Harlans I forget the name of It. It was in a

suit to enjoin the enforcement of an alleged unconstitutional

tax and the court in its opinion held that the decree could

run for the benefit of all the class irrespective of joining.

Justice Frankfurter: Mr. Solicitor General, there are

other problems involved in this other than the mere question

of who are the technical parties to the litigation.

Whoever writes the decree must write it in the context

of what will actually happen and what could happen.

It is hard for me to believe that if this court

ordered 11 children to go to a school in a county in which

there are 2800 children -- that is the figure in the same

situation, that somehow or other, the others will not manifest the

desire for the decree, and therefore merely writing a decree

for the 11 may amount to nothing except the ink that is written on

a piece of paper —

Mr. Sobeloff: In answer to the question yesterday

I think I indicated in answer to Mr. Justice Harlan that I

think you have to remember that hovering over these few are a great

many others who will be affected, but I don't know what

conclusion the Court will come to.

If you come to that conclusion of course it is obvious

that this is a class action, then you have to consider the

effect on the whole area.

409

bdi6 Justice Frankfurter’s My suggestion is 1 don't

have to get into the fog o? class action and spurious class

action to consider the consequence of rights for 11 what might

be called fungible subjects In relation to the 2800,

Mr, Sobelcff: On the other hand* there Is this to be

said. You have here not a case where the orator in favor of these

necessarily displaces other people* What the plaintiffs here are

asking :1s not to be admitted to white schools. Technically

what they are asking for is to go* to be permitted to attend

schools that are non-segregated.

That does not mean that all 2500 will be in

white schools. They are to go to schools in which they are

admitted regardless of color*

The problem may not involve a complete redistribu

tion of all* This court might consider it wiser to defer deal

ing with the rest.

Justice Frankfurter: But it may involve -- and I do not

see easily how it can avoid involving — considering the educa

tional system of that county and the administrative problems*

Mr. Sobeloff: I am inclined to sympathize with that

view. I point out if you take the other view it does not

necessarily follow that you have to consider the whole picture.

You may say sufficient unto this case is the litigation that

is actually before us.

respect to the namedWe are going to decide it with

410

bdXT plaintiffs and we are going to see what happens.

You may talcs that view. I am not urging chat it is

the better view* But I say that there is something to be said

for the consistency if you limit i'c to the li of giving them

their rights as they would appear if there were only

1 1.

If. on the other hand., you want to consider it in

determining the relief for the 11 whether there are others*

the whole scene, then you have to include the whole group*

Justice Frankfurter: It is not a question of

wanting, exercising, a preference for this or that* I may

speak for myself, the first requisite of a decree of equity is

that it be effective and not be merely a piece of paper.

Mr. Sobeloff5 I had intended to discuss this

Rule 23 (a)* I see my time is up and I will be very glad

to submit a memorandum.

The Chief Justice; Would you do that, please?

Mr. Sobeloff: Yes, sir.

23(a) which deals with representation is not toe

long and I think it would be well to have it before the Court

by reading it.

"If persons constituting a class are so numerous

a3 to make it impracticable to bring them all before

the Court, such of them, one or more, as will fairly

ensure the adequate representation of all, may on

411

bdl8 behalf of all, sue or be sued when the character of

the righte sought to be enforced for or against the

class is.." -- and then there are three sub-paragraphs

1, 2, and 3»

"Ore; If the right to be enforced is one joint or

common or secondary in the sense that the owner of the

primary right refuses to enforce that right and a member

of the class thereby becomes entitled tc enforce it."

I think the classic example of that is a stockholder5©

suit where the officers and directors of the corporation refuse to

vindicate the right of the stockholder which he holds

derivatively as a stockholder, under certain conditions he may

come in and stand in the place of the corporation of which he is

a stockholder. I think that is the typical case under one.

"Two; Where the rights sought to be enforced are

several and the object of the action is the adjudication

of claims which do or may affect specific property

involved in the action."

For Instance where there is a suit over a common

fund or a creditor’s action.

And the third, which I think would cover this cases

"Where the rights sought to be enforced are several and

there is a common question of law or fact affecting

the several rights and a common relief is sought."

Tnis Court could very well say that in the case that we

412

bd!9 have been talking about, the South Carolina case, these

IX are representatives of the larger group.

They prof ess to come in on behalf ox others ano. th*. t

these others have with them a common question oi law and fact,

affecting the several rights and a common relief is being

sought.

Here there is no attempt to recover separate damages*

Xt isn’t even a case where there is a common disaster and a

number of people in an accident have soughi- rel-.ei .

There the Court could adjudicate at one time the question

of liability and then have the measure of damages which would make

the difference in different cases, determined separately.

Here what they are asking for is a declaration of the law.

And an injunction. Now there is no practical impediment

imposed here to adjustment that will apply to the whole

class. The class at large has been adequately represented, fairly

represented.

The unnamed plaintiffs as well as those who are

separately, specifically named.

There have been a number of cases. The Court called

my attention yesterday to two. 1 don't think thac they are

cases that fall within this group 3. The Hansbury case is a

ease involving a racial covenant on land. It is a case that

arose of course before Shelley, and Kramer. The plaintiffs were

not litigants in the first case, but they come in a later case

bd20 and they say we are entitled tc the benefice of the

adjudication of this case in which we were not named parties.

It was a class action and we are in the same boat.

The answer of this court through Mr. Justice Stone

was that the people who sold the land to the plaintiiio .j.n

the second case# they had rights which would be affected

by the decree and they were not parties in the first suit,

so therefore it was not really a class action.

That the sellers of the land whose rights would be

determined here were not parties to the so-called class

action in the first case and therefore their rights ought;

not to be determined.

So it was not only the plaintiffs having their rights

adjudicated but their grantor. For that reason> the case was

not considered a proper class action.

That is readily distinguishable from this situation.

The other case that was mentioned* the Ben Hur case.

Justice Reeds There would be a good many defendants that

are not present here.

Mr. Sobeloff: I don’t know whether that cculd be

said here or not. It may be because of the division of

authority in the school districts.

Justice Reed: Yes. Also because this class suit

for the benefit of all the children in South Carolina.

413

Mr. Sobeloff In it for the whole of South Carolina?

414

bd21 Justice Reed: That Is my understanding*

Mr. Sobeloff: It is Just for those in the school

districts. I will check on this.

Justice Reed: The defendants are In only the

school districts.

Mr. Sobeloff: They could not pcsslbly hope for

the children in another district to be admitted in the schools

cf this district it must be limited to this district.

Justice Clark: They allege South Carolina.

Mr. Sobeloff: I think in the classical Joke, they cover

too much territory. I think obviously they can£ t maintain an

action against the school authorities in one district to admit all

the children of South Carolina,

Justice Reed: I was just thinking of some possible

defendants that were not before the court.

Mr. Sobeloff: Of course a more serious problem

would be where the authority ox* jurisdiction is fractionated,

whether you have in a particular case all defendants before the

court that ought to be there.

Justice Frankfurter: You certainly haven£ t gotten

the defendants in the other counties before the C;urfc —

Mr. Sobeloff: Absolutely, That is not even debatable.

Justice Frankfurter: — If you enter a decree In this

litigation unless they want to come in.-

Mr. Sobeloff: on«t see that it would avail anyb

bd22

415

get a decree. I dcn:t think the plaintiffs would seriously insist

on it.

But it does seem to me that this question never

having been decided by the Court, that there is room for holding

under this subsection (c) of 23 of Rule 23(c), that this 13 a

class action and you could treat it that way and declare the

rights of all these children

Justice Reed: Sven though they have not personally

come in.

Mr. Sobeloff: Even though they have not personally

come in.

Justice Clark: Could they come in?

Mr. Sobeloff: Even though they have not personally

come int you could say ”We will not include those who will come

in and wish to come in but we will make provision in

the district court to give them an opportunity to come in.”

Justice Reed: Would you set a time on that?

Mr. Sobeloff: I think there ought to be a reasonable

time like any order of the court that allows people to

intervene. It is customary co have a reasonable time,, 30 days,

60 days.

Justice Reed: Before judgment or after judgment?

Mr. Sobeloff: Generally the rule as stated applies

before judgment. But as I indicated before, there is one ease

where even after judgment a party was allowed to intervene only

bd23 for the purpose of seeking enforcement by vray of contempt

against a violator against the injunction.

So the matter is entirely open in this Court. There are

decisions both ways in lower courts and we will prepare a

memorandum so the court will have the cases before it.

The Chief Justices Mr. Solicitor General, we thank you

for your cooperation and for your helpfulness in these very

important cases.

Mr. Marshall, you may close the argument.

REBUTTAL ARGUMENT ON BEHALF OF HARRY BRIGGS

ET AL

BY MR. THURGOOD MARSHALL

Mr. Marshall: May it please the court, at this stage

of the case I would like permission of the Court to break what 1

have to say into two points.

One, there are some things that 1 think should be

commented upon as to the several state attorneys general and

as in our brief we found there are certain general points

that run through all of them.

I would like to reserve this time and take the

specific ones first and then get to the general ones.

The Attorney General of the State of Florida, for

example, had a pretty long argument on the point of leaving

tiiis to the local community and what would be done, pointing out

416

the several areas where it had been done and I think at that

41?

bd24 Stag© it should be significant that in the State of Florida,

right now, some five years after the decision in the Sweatt and

McLaurin cases we still have a case tied up in the Florida

courts that has been up here twice, back in the Florida Court and

is still there seeking only to break down the exclusion c? negroes

from the law school of the University of Florida.

That has taken them five years and they have not

gotten around to that yet. I think it Is quite pertinent to

consider how long it would take, wiihout a forthright decree of

this court to get around to the elementary and high schools.

This same is true for North Carolina. Even after the

Sweatt case it was necessary not only to go to the District

Court in Durham for a Judgment seeking admission of negroes

to the law school of North Carolina. It was not only defended

by the attorney general£s office. We had to appeal to the

Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit, which reversed the

District Court and ordered the negro admitted.

The State then petitioned this Court for certiori.

So in North Carolina it took quite a bit of time to get around

to the Sweatt and McLaurin decision.

It is significant that Arkansas, while waiting to

see what happened in this Court, I think their good faith can

be shown in two points, where, one, they adjourned the present

session of the legislature and they won't be back until 1957

I assume to get around to then begin a discussion of the May 17th

418

bd25 decision.

Oklahoma* it is significant that whereas most of* these

states complain about the terrific legislative problem involved

in changing statutes to finance their schools as a result

of whatever decree might come down from this court* that

Oklahoma in a few months not only passed necessary legislation

but amended their constitution to do it and I think that

pretty well takes care of the argument about the state being

unable through its legislative machinery to make its

necessary adjustments.

Justice Frankfurter: Doesn't that indicate variations in

state conditions?

Mr. Marshall: It involves variations* Mr. Justice

Frankfurter* but I think they are immaterial.

Justice Frankfurter: Maybe they are immaterial*

but if they are necessary then since I cannot, with every

respect to Oklahoma attribute very special biological virtues

to the inhabitants of that state* can only draw a conclusion that

there must be some other factor.

Mr. Marshall: I think you are right* Mr. Justice

Frankfurter, and 1 think at that state I should remind the court

that the State of South Carolina folks in Smith against Allbright,

the primary case was in sight, had no trouble in calling a

special session of the legislature to repeal all of theS.r

primary laws to circumvent the decision of this court., and I.

419

bd26 would assume that all of the states could equally get a meeting

of the legislature to comply with this court,

And as for the argument of the State of Maryland,

my native state, I think I should say in the beginning that

the comment made by Attorney General Sybert that all of the

thoughtful negro and white people in the State of Maryland are. for

this long prolonged, gradual business, I am afraid that as a

Marylander I am in the thoughtless group, bec~use there is no

question in my mind about that.

And it is significant that the Attorney General of

Maryland in asking for time, for unlimited time, based It on

the fact that they were making such terrific progress on race

relations to the point that this year, last year in 1954 they

abolished the scholarship provision to send negroes out of the

state which was declared unconstitutional by this court In

1938, and by the Court of Appeals of Maryland in 1936.

So that it took them 16 years to catch up with the law of

their own court of appeals and the law of this Court and

use that as the basis for saying that because of their good

faith w© should work the problem out.

As to the state of Texas, we pointed out in our reply

brief something that I think is very significant.

That Texas poll, the exact same agency that took a

poll in the Sweatt case, and they found in the Sweatt case an

even larger number of people that were bitterly opposed vo

420

bd27 negroes being admitted to the University of Texas.

And yet when we know that negroes were admitted to

the University of Texas, they are going there now, and our brief

also points out that negroes are attending parochial schools

throughout Texas on a non-segregated basis, and that many,

more than half of the junior colleges in Texas, the municipal

junior colleges, have been desegregated since this case has been

pending,

The points I am only trying to make there is this leav

ing out what I consider to be important points. And

throughout all of this, it is very significant that the State

of Texas had great difficulty through its representative here

admitting that in these counties within this area with this

very small number of negroes, that they could not take some

courage from what happened in Arkansas in those two counties.

I can see no reason that makes Texas so different from

Arkansas. And finally as to the specifics, as I understand

the position of the United States Government on this one point

of time, the original position was one year, then you could come in

and ask for more time, and in the brief they filed just

last November they take the position that they would not like

to see a time limit fixed because what would be a minimum time

limit might actually become a maximum time limit, that the

school board might tend not to start work until the end of

the year.

421

bd28 Well, so far as the appellants in these cases are

concerned,. If we could get the time limit on the year we would be

willing to take our chances that it would not be done until the

end of that year, we would be perfectly satisfied.

So there I think the Government's position gets

back to its original position cf one year.

The only thing we don«t agree on is the question of

extension of time.

As to what runs through all of these arguments of

the states, if I remember correctly, practically every Attorney

General who appeared before this Court and those representing the

Attorney General either began or some time in the argument said

there was no race prejudice involved, there was no racial hatred

involved, there was no bitterness involved.

And then I think you can take the balance of each

argument made by the State Attorneys General and find out

whether or not that is true.

Most if not all of them said that it was all right,

there were very few negroes involved like in Arkansas, that

it is possible they could be integrated, that there might not be

friction.

And then they said ’’However, where there are a large

number of negroes involved and only a small number of white people

involved, that is the most horrible situation.”

So on the one hand they say that where the majority.

k22

bd29 the big majority are white., a very small minority is negro, you

can do it, that is the most feasible, the nicest problem*

And the other is the reverse, well, the only way to

understand that is that in one category you have a small number of

negroes and in the other category you have a small number of

white students, and the only difference between the two is

negro and white, and if that is not race 1 don;t know what

race is *

And that is the argument that is made throughout

these cases.

f I think that we should keep coming back to this point*

'That we look at this case as a regular legal proceeding. And then

we look at that in the broader perspective. The decision on May

17th, forthright straightforward position of the law of this

country as pronounced by its highest Court, since that time,

partially because of the leaving open of these two questions,

but throughout areas of this country, stimulated by statements of

state officers, attorneys general, governors, et cetera, the whole

country has been told in the South that this decision means

nothing as of now.

It will mean nothing until the time limit is set.

So when you conceive of it in that framework, this time limit

point becomes a part of the effectiveness, forthrightness if

you please, of the May 17th decision*

That is why yesterday and the day before this Court was

423

bd30 told over and over again that these states were not moving

at all until they found a time limit.

So to my mind whereas in an ordinary case the question

of details of decree are more or less minor matters — or there

are exceptions to it that do not reach the level of high

constitutional principle, but in these cases they do reach an equal

level with the forthrightness of the May 17th decision.

And when we take that position, at least we urge upon the

Court, there is considerable difficult in getting to the ether

problems.

One side, for example, of course, no court I am

certain would agree, as was suggested by one of the Attorneys

General, that in deciding as to the time for enforcement of a

constitutional right the Court would hit a middle ground

between two positions.

We are not in this Court bargaining on a negligence

case or something like that.

It is significant — I might be wrong. I know it has

happened in cases involving statutes, even Federal statutes, even

anti-trust, for example, statutes.

But I donrt believe any argument has ever been made

to this Court to postpone the enforcement of a constitutional righi

The argument is never made until negroes are involved.

And then for seme reason this population of our

for the sake of thecountry is constantly asked 11 Wei.i, group

424

bd31 that has denied you these rights all of this time1', as the

Attorney General of North Carolina said, to protect their greatest

and most cherished heritage, that the negroes should give

up their rights.

If by any stretch of the imagination any other minority

group had been Involved in this case, we would never have been

here.

I just cannot understand at this late date why we

constantly are faced with that. But we are faced w±h it and we

have to meet it as best we can.

The nest point I want to make on the general side

is what I made before, and that is the need for uniform

application of our constitution and all of its provisions through

out the country so that freedom of the press won't mean one

thing in one state and anotherthing in another state, so that all

of these rights in the Constitution — it has never been

said on any other right that I know of that special

exceptions should tee made as to one state or the other.

And as of this stage of these arguments, there is the

real possibility that in Clarendon County, South Carolina, for

example, we could have three different rules in the same

county because there are three school districts there, and

the same of course would be true on and on.

To my mind that is not the way that our Constitution

is to be applied. Local option I still say is what is urged.

M3? And it Is not local option even statewide, because

each Attorney General said It 1b going to be different from

on© area of the state tc the other, and Texas went so far as to

bring In maps to show that it would operate from one area to the

other In a different fashion,

I am sure that the State of Texas does not even

administer their own constitution in varying areas of various

fsections of the country *

But they want the Federal Constitution, And the

most significant comment made over and over again was that the

difference between acceptance and rejection of a constitutional

position depended on whether it was pronounced from within or

without a state.

1 think maybe that is the best answer I know to any

claim that this is not local option.

While I am on that point I would like tc come back

to the class action point which I was asked and which has

come up again. It is true that in both of these cases

the class was made for all of the negroes in the category of

school age within the state.

We expected at any time that that would be limited. The

idea was to make the class as broad as possible and when it got

limited, we would not be down tc nohcdy,

Obviously I agree with the position that has foeevi

made here this morning by several of the Justices.

423

Obviously

bd3.3 we can get relief from nobody who is not in court, and

there is no intention on our part to bring in any defendants from

any other counties when we get to the district court.

We would not think of doing such a thing. It applies

only to the negroes in school district number cne in Clarendon

County who are of school age, resident, et cetera, in

school district number one. In the present posture of this

case It does not, could not even include the entire county,

The largest group it could cover would be those in

school district number one. The largest group it could possibly

cover in Prince Edward County would be the negroes of

high school age in Prince Edward County and It could apply to no

one else.

Justice Frankfurter: In numbers, how many would that be?

Hr. Marshall: In Clarendon County I think it is 28 and

in Prince Edward it is 800,

Justice Frankfurter: With reference to the high school

age, 800 would be involved?

Mr. Marshall: Yes, sir, a total of 800, I under

stand it is 863 white and colored, 400 and some negroes.

Justice Frankfurter: The question is intermixing these

students, allowingthem free access, not allowing any students

to be barred merely because of color-?

Mr. Marshall: Yes, sir, it would only apply to that

number, 400,

U26

427

bd34 Justice Frankfurters And numerically would that

cover 400 or absorb 400?

Mr. Marshalls It would be 450-Bome.

Justice Frankfurters That is 400 are now excluded

merely because of color?

Mr. Marshalls That is right, and the only thing we

want is to say that you can't exclude that many which is all of

the negroes involved.

Justice Clark: How many are named in this case

In Virginia?

Mr. Marshalls I can tell you In Virginia it was 45,

In the Clarendon County case that number is much smaller,

And I may say, Mr. Justice Clark, that after the

questions yesterday I made every effort to get some of our

people in Clarendon County on the phone to find out how

many were actually in as of today, and I could not get ahold of

anybody,

Justice Clark: How many in Prince Edward are named in

the case?

Mr. Marshall: There are 119 named. 119 named plain

tiffs „

Justice Clark: The Courts named them in that county?

Mr, Marshall! Yes, sir.

On that particular point, if the court please, I

think we oughu to emphasize the fact that chis is an action

428

M35 under the three-judge statute aimed at having declared

unconstitutional a state statute of statewide application, and

the constitutional provision obviously, and that the class

action is merely a procedural device that Instead of naming 5 ©r

6 thousand people or what have you, instead of putting all of

them down, it is just merely procedural•

But that the effect of a statute being declared

unconstitutional by this Court does at least have

statewide significance as witness the fact that the statute

requires you to notify the state attorney general that you are about

to attack his statute.

And so that so far as the basic issue in this case

is concerned, it is to have the statute declared

unconstitutional

Once the constitutional provision in the statutes are

declared unconstitutional, then we come up against the

problem as to whether or not a state officer is going tc

operate under a statute that is unconstitutional.

Insofar as the disrict involved in this case is

concerned, we, the negroes not named, we are certain as our

research will show that they can intervene any time before

Judgment and merely show that they are within the class

Involved.

Once they do that, they can take the same position that

a named plaintiff would have.

429

bd36 The Chief Justices Mi’. Marshall, arejiour authorities

on that subject In your brief?

Mr. Marshalls No, sir.

The Chief Justices Would you furnish them to us?

Mr. Marshall: We will be very glad to, sir, but I say

in all frankness that they are pretty much the same as the

Solicitor — there is really very little dispute on it.

It has not been decided by this Court, but the thing

I want to say is aside from these cases, that it is the most

difficult problem if every negro in the South his to go to court to

get the rights that everybody else has been enjoying all these

years.

I grant that it is not before the court. But

we thought the class action was this procedural device so that when

it comes down to the district court, I mean when the judgement

comes out of the district court, that whoever is administering

that policy will recognize the law and not just admit McLaurin

into the University of Oklahoma or Sweatt into the University

of Texas but let all negroes who are qualified in.

Justice Frankfurter: If it would not interfere with

the course of the argument you ultimately have in mind, would

you care to sketch what you see to be the sequence of

steps of events if there were a decree in terms, say, that not

one of these 400-odd, whatever the number may be in the

school districts, including the ones in Clarendon County,

M37 not one of these children ahold be excluded from any high

school In that district for reason of color.

Suppose that were the decree* what do you see or

contemplate as the consequence of that decree?

Mr. Marshall: If that decree were filed with nothing more

then I would be almost certain that the school board through

its lawyers would, come into the district court eicher before

this is a possibility that I have to put two on.

If they d o n a d m i t them and we file a suggestion of

contempt with the District Court --

Justlce Frankfurter: Before you get to contempt

there must foe some action which would be the basis of contempt.

What do you think it would involve as the consequence?

Mr. Marshall: They refuse.

Justice Frankfurters That is that the hundred* or

four hundred students would knock at the door of the white

schools,

Mr. Marshall: Oh* oh* that, no, sir, not necessarily

because there is not room for them.

Justice Frankfurter: I should like to have you spell

out with particularity just what would happen in that

school district.

Mr. Marshall: Well, I would say, sir, that the

school board would sit down and take this position with

its staff, administrative staff, superintendents, supervisors,

430

431

bd38 et ceterac They would say "The present policy of

admission based on race, that is now gone. Nov; x;e have to find

some other one." The first thing would be to use the maps

that they already have, show the population, the school popula

tion, then I would assume they would draw district lines without

the idea of race but district lines circled around the schools

lilce they did in the District of Columbia.

That would be problem Mo, 1.

Problem No. 2 would then be "What are we going to

do about reassigning teachers?"

Mow that there is no restricting about white and

negro it might be that we will shift teachers here or shift

teachers there.

Third would be the problem of bus transportation, We

have two buses going down the same road, one taking negroes, one

taking whites.

So we might still do it that way or we might do it

another way.

Justice Frankfurter; Throughout all this period, I

wouldn?t know how long that would be, there would be no actual

change in the actual intake of students, is that right?

Mr, Marshalls I would say so, yes, air.

Justice Frankfurters All right.

Mr, Marshall; I would say so. That was the point

1 was going to get to.

432

bd39 And assuming that they are doing that and the time is

going on, they might come into the district court and ask

for further relief, which would be to say "We are working in

good conscience on this. We just canJt de it wSfcin a reason

able time." Or, "We would go into court and say they are not

proceeding in good faith," either way the district court would at

that stage decide as to whether or not they were

proceeding in good faith, at which stage the district court would

have the exact same leeway that has been argued for all along.

Justice Frankfurter: Now as to primary schools, that

is if that is what they are called.

Mr. Marshall: Yes, sir.

Justice Frankfurter: The problem would be a little dif

ferent because the number makes a difference.

Mr. Marshalls Well, it would be different because

of numbers. The figure shift would be the shifting of the

children.

Justice Frankfurter: I am assuming that under the

responsibilities of the law officers in various states, there

would be a conscious desire to meet the order of this Court.

X am assuming that this process which you outlinec. would

proceed, wouldn't that be a process in each one of these school

districts?

Mr. Marshall: That would be and I think that that is

the type of problem.,

4.33

bd4C The only thing is we are now on this do-it-right-away

point.

Justice Frankfurters Your analysis shows that do-lt-

right-away merely means show that you are doing it right

away, begining to do it right away

Mr. Marshall? I take the posia.cn, Mr. Justice

Frankfurter, this lias been in the back of our minds since

Question 4 (a) and the others all along, as to whether or

not we will be required to answer this in the context which

we have been answering this, or whether it was not the question

of contempt, that it would never come up except on contempt.

Justice Frankfurter; That is the way it would come

up.

Mr„ Marshall; The way you put It.

Justice Frankfurter: The school authorities would say we

have not got the room or we have not got the teachers or

the teachers have resigned or a thousand and one reasons

or 20,000 reasons, that develop from a problem of that sort*

«r

you couldn't possibly proceed in contempt, could you?

Mr. Marshall; I doubt that we would even move for

contempt.

Justice Frankfurter: Except there might be different

difficulties of interpretation as to the reasons for delay.

Mr. Marshall: And for example we would not recognize as

reason for delay the waiting for these attitudes to catch up

bd4l

434

with us. We would not recognize that

Justice Frankfurters Well an attitude might depend on

the non-availability of teachers. That might be an attitude.

Mr. Marshalls There would always be availability of

competent capable negro teachers, always<.

There is no shortage. And X think it is very

significant In New York —

Justice Frankfurter: I ara not sure why you say that

with such confidence. In different localities established

as you well know, better than I —

Mr. Marshall: Yes, sir.

Justice Frankfurters Why do you make such a state

ment?

Mr. Marshall: Well, there are so many that are in areas

that don't want to leave because of home ties or what have you,

and because they are so well trained there are school boards

that won’t hire them because they don’t want them, and those

are very available, I mean well-qualified teachers, sir.

North Carolina, they take a most inter

esting position: They say the negro teachers have wore experience,

more college training.

Justice Frankfurter: You have heard that the bar

of this Court with considerable pride stated those standards

of negro teachers.

Mr. Marshall: Yes, sir, and it was followed by the

4-35

bd42 fact that they would deprive the white children of the benefit

of superior teachers and fire the negro ue&chers.

Justice Frankfurter: I merely suggested in the

areas of education that I know something about a plethora

of well-equipped teachers is not there.

Mi*. Marshall: Hell, it is on the broad general

figures, Mr. Justice Frankfurter, but on the negro side

w© are producing them and in all frankness as the Attorney

General of North Carolina, Mr Lake, said in the South that is

about one of the few places they can get work.

And you have maters, M.A.s, that are unemployed.

The other point that I would like to come back to

Is to continue this class point as I see it affects these

cases.

The named plaintiffs, I think there is no question

they are entitled to relief. And on some of the questions

it seems to me that if t e named plaintiffs In such a small

number are admitted, I would not have the real physical difficul

ties if you only admitted, if the school beard only admitted

those named plaintiffs.

However, it seems to me we have to be realistic,

and most certainly by the time the case, before the case gets to

judgment, many if not all of the other negroes will have

intervened when they find that they are not protected and the

only way they can get protected is to intervene.

436

bd43 I would imagine with considerable reliance that they

would intervene.

The only thing it seems to me is this, that it 3s going

to be difficult to consider this in the narrow named plaintiff

category without the understanding that the whole class

will eventually be in it.

That brings me to the next point, which is

that I hope the Court will bear in mind the need for this time

limit, which I come back to, because in normal judicial proceedings

in these and other cases, there will be so much time lost anyhow.

We have to go before the local school board, we have to

exhaust our remedies before we can go into court, there is

no question about that.

Then we get into court and then unless we have this

time limit, we most certainly will have this terrific long

extended argument and testimony as to all of these reasons for

delay, which I or any lawyer would be powerless to stop.

It would depend of course on the district judge.

But as of this time, the only valid reasons that have

been set up have been the reasons set up relating to the physical

adjustments and not a single appellant, appellee and not a single

Attorney General has said one thing to this Court in regard

to physical difficulties which could not be met within a yeare

I come back to our original position as to why we picked

a year

437

bd44 W© picked Si year because we talked with sdminis—

trators, school officials and we Just could not find anything

longer than a year. I submit that the American Tobacco Trust

case., which we have on about the next to the last page of our

brief, which involved a dissolution of this trust, this Court

said that because of the involved situation and everything, a

time limit had to be set, and this Court set a six months3

time limit and told the district court that you can give them

an extension of 60 days if they show valid reasons.

However, if you are convinced they can do it in less

than 6 months, see that they do it in less than 6 months. Now that

is at least one case in which this Court did do it on the basis

of whatever material was before them, and the material you

have before this Court at this time shows that we certainly have

a right, if nothing else was shown, we would have a right to unis

immediate action, the time to take care of these adminis

trative details, and that you have nothing else to go on.

The other side has not produced anything except atti

tudes, opinion polls, et cetera.

On the basis of that, it seems to me we get back

to the normal pro cadure which would be the type of Judgment

from this Court that would require them to be admitted at, let us

the next school term, and the contempt side, as I mentioned

before.

Cr what X consider to be the more realistic approach-

todUi5 which would be to let the other* states involved know and the

other* areas know that it will not do you any good, if there

were no time limit fixed the school officials in the other

states that will follow whatever this Court will say, if they

knew that they had a chance, Just a chance of getting interminable

delay from the District Court after the lawsuit was filed,

then I would imagine that they would not begin action until

after the lawsuit was filed.

However, if they knew that if a lawsuit was filed they

would have to either desegregate Immediately or would get no

more than a year, they would start working .

Sc it seems to me that if I am correct in that, then

this time limit gets so involved with this constitutional right

that so far as not the plaintiffs in these eases are concerned

but insofar as precedent, effect and so forth in the country is

concerned, that now this time limit is involved with the

constitutional right and that the statement on time should

be Just as forthright as the statement was made on the

constitutional position taken in the May 17th decision,

and so we submit to th^ Court that on behalf of the appellants

and petitioners ; we have been -appreciative of all of this time

that has been given.

The last thing that I could possibly say is what I

said in the beginning. That in considering problems as tougn

as these, and they are tough, that what 1 said before is

^38

^39

bd46 apropos now. It is the faith in our democratic processes

that gets us over these, and that is why in these cases we

believe that this Court, In the time provision, it must be

forthright and say that it shall not under any circumstances take

longer than a year.

And once having done that, the whole country knows

that this May 17th decision means that the protection cf

the rights here involved of any person in the category,

any negro, will get prompt action in the court.

Once that is done, then we leave the local commu

nities to work their way out of it, but to work their way out of

it wJhin the framework of a clear and precise statement that

not only are these rights constitutionally protected, but that you

cannot delay enforcement of it.

Thank you very much.

The Chief Justice; Attorney General Almond, do you have

any rebuttal to the argument of the amicae?

REBUTTAL ARGUMENT ON BEHALF OF PRINCE EDWARD

COUNTY, VA.

BY MR, ALMOND, ATTORNEY GENERAL

Mr. Almond; Mr, Chief Justice, I thank you

for that. We feel in Virginia that we have said all we could

say in support of our contention before the Court.,

I do not know that we could add anything further unless

there ware some questions which the Court wished to propound

Otherwise I thank you,

«£he chief Justice; Thank you very much.

Is counsel for South Carolina here?

.The same opportunity would be tendered to them, of

course, if they were here*

(At is 15 p.iru the oral arguments were concluded.)