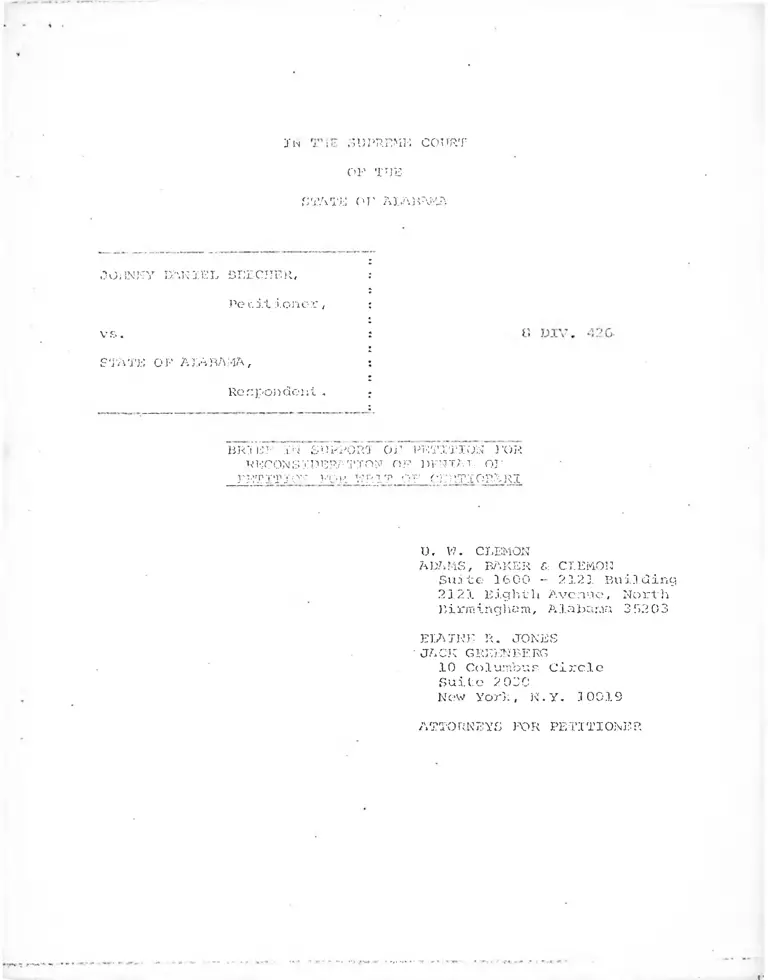

Beecher v. Alabama Brief in Support of Petition for Reconsideration of Denial of Petition for Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

January 31, 1975

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Beecher v. Alabama Brief in Support of Petition for Reconsideration of Denial of Petition for Writ of Certiorari, 1975. d9ccc31e-c39a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/6ed60289-0cd1-4992-ba8f-d2d0e026cd0b/beecher-v-alabama-brief-in-support-of-petition-for-reconsideration-of-denial-of-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed February 24, 2026.

Copied!

IN 3 l)PEEHK COURT

OF TEE

STATE OF ATyARYYA

CO;INFY DANIEL BEECHER,

Pe tit loner ,

v s.

S I A TK O F AIA BA M A ,

Respondent.

BRIEF ~i:n " SITBPORT OF PF/JTITl'ON FOR

RECONSIDERATION OF UFNTAT. op

PETITION FOR V’RIT OF CERTIORARI

U. V?. CLEMON

A DA MS, BAKER &. CLEMON

Suite 1600 - 2123. Building

2121 Eighth Avenue, North

Birminghern, .Alabama 3 !">203

ElATKE R . JONES

• JACK GREENBERG

10 Columbus Circle

Suite 2030

New York, NAY. 10019

ATTORNEYS TOR PETITIONER

r

TABLE OF CONTENTS

I. St a temc nt of the Case . • • • * •

II. Staterucnt of the Facts • • « * * • • ■ •

m . Proposit ions of 3 j a w • • • « • • •

IV. Argument • « 9 • # *

1. The Deni a1 Of Certiorari Should Be

Rocon sidored In Light of An

Int erv ening Diecisi.cn of The Supreme

Cou rt of the United Stat OS * * • • * * •

2 . The Deninl Of Certiorari Should Be

Recone icier ed Because The Alabama Court

of Criminal Appe a 3. s C1 e arly Erred In

No t F.i.tiding T‘hat The Dis trict Attorney

Common.ted Implermissibly Upon The

Fci ;i.1 ure Of T)ie Defendant to Testify . .

10

12

12

13

V. Conclusion 21

STATEMENT OF THE C7\SE

On June 26, 1972 the Supreme Court of the United

Meter reversed petitioner Johnny Daniel Beecher's second

conviction of first degree murder. Beecher v._Alabama, A 08

U.H. 2 34, 92 S.Ct. 2282. The cause was originally set for

r<-~trial in Cherokee County, Alabama during the first week

o; October, 1972. However, the trial court granted petitioner'

)<,.< it ,<m por A Sanity Inquisition; and by order dated October

•1, 197 2 petitioner was committed to Bryce Hospital in

Vusealoosu, Alabama for study and observation. On December

li:, 1 <• v[> tlie Superintendent of the aforesaid hospital sub

mitted iris report to the court; and petitioner was thereafter

tvans*erred back to Centre (Cherokee County) Alabama to stand

tr ) u1 bv order of the court below dated January 12, 1973.

Petitioner was arraigned in Cherokee County on

March 2, 1973; and trial was set for March 12, 1973.

Prior to the .scheduled trial in Centre, petitioner s

remise 1 filed several pretrial motions, one of which request

ed a change of venue on the ground that petitioner coulci not

obtain a fair trial in Cherokee County because of adverse

publicity. This motion was denied.

On March 12-13, 1973 the trial court attempted to

qualify u jury of this cause. At least onc-f.ourth of the

1 i or.poct i vc- jurors candidly testified on voir dire that be-

1

MilOf of 1

: o? 1 an

u‘(•old to

'■r!b , t he

l ‘ h.J * Jf' 1 * 0 i

u ia.1 court granted petitioner’s Motion For A

,\ 1 .; 5 i.i: m f or t r i a 1 •

On April 6 , 1973 petitioner was arraigned in

, , !U)„ (i.avorencc County), Alabama; and ho entered a plea

t(f (.uil(y» to the indictment returned by the I960

county grand jury charging him with first degree

; . (lb 17).

Prior to trial, petitioner's counsel filed an Appli-

ion lor A Change of Venue, asserting that because of the

is>f1 . l o r y and prejudicial media coverage of the alleged

of his cause, he could not receive a fair trial m

P 7̂ hearing on this motionl„r,;i once County, Alabama. (R. i !>) •

,,„,i „n April 24, 1973 <R. 18). After the hearing, the

wan denied, -0 5 a petitioner duly Accepted. (R. 18, 726) .

Another pretrial motion related to the racial —

;.notion of the jury roll in Lawrence County. In thin Motion

..... c.nnh the Venire, petitioner asserted that the method by

Whirl, juror:-, worn selected in Lawrence county precluded

. ..... live representation Of blacks on juries in the sard

, (-11:1*. y; and that blacks were in fact grossly underrepresen-

t,;l on the venire selected for the trial of Ins cause, ('<• 12,13)-

Petitioner's’counsel petitioned the court for an

(,;d.T permitting them to inspect the jury roll so as to

(,,.t (.Il;5im. jt ;; racial composition prior to trial but this

itio!J Wli;- effectively denied until the commencement of

, j y o, 11). Evidence on this motion was taken on

•) t 1973; and the motion was denied. (R. 18).

ionor timely excepted to this ruling of the court.

(k. -if.fi) •

Petitioner's counsel additionally filed a pietrial

••.■a. ion - To Suppress Evidence, which prayed the court to

MM>pi-e:;s any and all statements allegedly made by- petitioner

in..:;;do the presence of his counsel. (R. 14-16). This motion

v:.c. heard on June 20, 3 973 and it was denied. (R. 1136).

Petitioner- took exception to the denial of the motion

(U. 1 136) . ’•

Trial was initially set for April 23, 1973; but on

the motion of the'State for a continuance because of the

ill ness of an essential witness, the case was continued for

trial to dune 18, 1973. (R. 18, 19).

Trial was commenced on June 18, 1973 in Moulton,

Alabama, (lb 22).

Following the State's presentation of its case,

pet it i oner moved for a directed verdict of acquittal,

which said motion was denied. (R. 1225). The jury returned

a verdict of guilt and a sentence of life imprisonment on

3

June 21, 1973. (R. 22).

Petitioner's motion to set aside the verdict as

beinq contrary to the weight of the evidence and his motion

for a now trial were denied, and he duly excepted.

(R. 1257, 1258, 1264).

Petitioner's oral notice of appeal to Alabama

Court of Criminal Appeals was noted (R. 1264); and he was

granted leave to proceed in forma pauperis (R. 25, 1260) .

On October 11, 1974 the Court of Criminal Appeals

affirmed petitioner's conviction and sentence. A timely

petition for rehearing was filed by petitioner; ana oil

October 29, 1974 the said petition was denied by the Court

of Criminal Appeals.

Thereafter petitioner sought a writ of certiorari

in the Supreme Court of the State of Alabama. Petition for

Certiorari to the Alabama Supreme Court was denied on January

16, 3875. Petitioner now respectfully moves the Court to re

consider its decision denying the Petition for Writ of

Certiorari.

4

« wti’f r— ymfmjmr- («■<

STATEMENT OF THE FACTS

,,r, _Ad dnjm:d_qn Motion To Quash The Venire

Tllo census information introduced at the hearing

on the notion to Strike the Venire showed that the total

J..!j-.Mil.it.ion of Lawrence County in 3970 was 2/,281. Of that

nu:,ju-r 5,114 were black, or 18.7%. The total number of

j„ ! nor,.'-, over 21 and therefore eligible for jury duty was

j Of this, 2,355 wore black, or 15.4% (R. 181).

In Lawrence County, the master list of potential

jurorr. is compiled by a three-man Jury Commission appointed

Ly the C.overnor. This Commission is all-white (K. 18 7)- 1

it moots annually to refill the jury box (R. 183). At

nuon meeting the Commission compiles a master jury list

iror-i v.’hich individual venires are drawn. f>

■J’lie process most relied upon in compiling the

mart.or list is the key-man system. Under that system, the

Commissioners first assign themselves to specific beats or

pi cr i nets, which would also include the beat in which they

1 i v,.(] (k , 189, 234). Because the Commissioners do not

know all residents in each of their beats, they contact a

loading citir.cn in the beat who recommends names for the

}/ At. the time of the hearing on defendant's motion to

(mash the venire, one of the three Commissioners was

deceased. He had been a member for eight years prior

to his death (R. 182).

'-TV—

... • . Ur.L. This key man identifies those persons on the

,,on list who qualify for jury duty (R. 186).

The Clerk of Commission, Mrs. Jean Wann, also

names for the master list. She, too, utilizes the

... . in ...l(.m . she testified that she visits one beat a

oonfnoting friends and relatives who supply her with

. of "<|ood people in their community" for potential

i-i! V duty (K. 2 67-69) . She also testified that she gathers

, during political rallies in the different boats which

.,t 1 ended predominately whites (R. 273). Her only eon-

.iU., v.; p, mixed groups was through organizational meetings

td tin* Community Action Agency held in throe communities m

5 county (R . 273). She, like the Commissioners, is not

J ami liar with many of the beats. - She was hired m .1971

(i\ 266) .

'J'ho Commissioners and the^ Clerk are equally as un-

1 . uni liar with the blocks in. Lawrence County as they are with

boats. Commissioner Gentry testified that although he s

livid in his present beat for 65 years, he would not know

.,11 black families there (R. 226, 229). Commissioner Wiley

2/ t !,(. }-.oy men are also used to identify persons on the

pel 1 list who may have died (R. 185)

l// Mrs. Wann testified that she is not familiar with beats

5, 6, 7, 8, 10, 11 (R. 284).

C

lhat ho knew lose then >00 of the 2,325 black

in the county (R. 2G0) .

The -Clerk testified that the overall jury list

̂(>*/•> from which the venire for this trial was -drawn

approximately 3,000 names (R. 377). The names

, according to the beat in which the juror resides,

g.-t ermi ne the total number of blacks on the master list,

i(1()Iu.r fjrr,t. examined the Commissioners, the Clerk and

, ro,n J.awrenee County who identified the beats wherein

were- any blacks. After studying the master list,

witnesses then recited the names they recognized as

(>1 blacks.4-/ffhis testimony revealed that on the jury

... , hore were 155 blacks or 5.15 of the total. (K. 319

:g:(>, 3 3 i -- 3 4 , 335-38, 377). -V

'";iy 3332 txtilttz

" t ]».- roll may bo examined m open court.

'thus blacks wore underrepresented on the overall jury

; ;V 5 s s ~ & ;»

1 .i 1 ion, rather than to simply subtract the two i —

tnues. f.eo Alexander v. Louisiana, 4 0a U.S. 6. >, G2 J

(1 072) w 1 iere the Suprcmo Court approved this method.

7

It in from this master jury list that names of

Vt.m remen of grand and petit juries are taken (R. 387).

Oudgo Billy’ C. Burney, Circuit Judge for Lawrence

(a t y , testified that 15 or 16 venires were drawn in 1972

Thirteen venires introduced at trial, represent-

. -lt. least 807 of the total number of venires drawn in

revealed that those drawn for the criminal docket

ilV,.)-,iqed about 77 names and about 81 for the civil OX.

6/U7) . -y

T)»e percentage of blacks on each of thirteen of

r.i>:t ccn general venires drawn in 1972 ranged from .a low of

to a high Of 8.37. V Of that total of 1,015 names

iipjx ng on: those thirteen venires, only 49 V were black

V

6/ These averages were obtained by adding the total number

of names on the venires drawn for they criminal and ~..v

dockers, separately. Then each total was divided b> t .

number of venires drawn for each docker. _ Of the 13

venires introduced at trial, three contaxnrng 24 a name ,

were drawn for the. civil and 10 containing 1 70 namu.> - xc

drawn ior the criminal docket for an average of 81 and

77 names, respectively.

Those percents,jes represent, those blocks previously idon-

tifiod as such on the master list and_appearing on

3 3 individual venire introduced at trial.

8/ The figure of

and among the

49 represent blacks found on the

155 on the master list.

13 venire

8

or 4.8%. That those figures arc fair representations of the

actual number of blacks called for jury duty is supported by

the figures for the venire for this trial. It was stipulated

by the parties that of 70 regular and 5 special jurors orig

inally drawn for this trial in April, 1973, there wore only 5

blacks, or 6.6% (R. 438). 7\ second venire was drawn in June,

1973. Of 80 jurors summoned, there wore 4 blacks, or 5.0%

(R. 695). Of 58 jurors actually present on day of organization,

only 3 were blade, or 5.17% (R. 696). The jury which convicted

petitkrrr was all-white (R. 705) .

Comment on Petitioner's Failure to Testify (R. 1?3,6-123_8l

In the course of his summation to the jury, the Dis

trict Attorney referred to the confession allegedly made by

petitioner - to Deputy Sheriff Ken Phillips. (R. 1302). After

reciting the details of the alleged confession, the District

Attorney stated, "No one took the stand to deny it." (R. 1237,

1238). The petitioner's objection and motions for a mistrial

and a new trial were denied. (R. 1236, 1237, 1238).

PROPOSITIONS OF LAW

THE DENT

INTERVEN

REGARD T

Panic]. -■

y.'nQor '

Dunciiu-J

HoyI v ■

Smith v

I.

AL OF CERTIORARI SHOUI.D BE

DKG DECISION OF THE UNITED

'O JURY DISCRIMINATION

RECONSIDERED'IN LIGHT OF AN

STATES SUPREME COURT WITH

u 1'Q’ii.s .iimo-r 43 U.S.L.W. 3415 (U.S., Jan. to 1975).

. t,ou i niJ.nLL.- 43 U.S.L.W. 4167 (U.S., Jan . 21, 1975).

L._Xauj-DJlURLf 391 U.S. 145 (1968) .

Florida, 360 U.S. 57 (1961).

. Texris, 313. U.S. 128 (1940).

10

* i' *>• -1

II.

THE DENIAL OF CERTIORARI SHOULD BE RECONSIDERED BECAUSE THE

ALABAMA COURT OF CRIMINAL APPEALS ERRED IN NOT FINDING THAT

THE DISTRICT ATTORNEY COMMENTED IMPERMISSIBLY UPON TIIE FAIL

URE . OF. THE DEFENDANT TO TESTIFY . •

]jOrjo v. Twomey, 404 U . S. 4/7 (1.972) .

Fontaine v. Cal 3.fornia, 3 90 U.S. 593 (1.9GB) •

C h a pman v . Ca11 fornia, 3 B6 U.S. 38 (1967).

Griffin v. California, 380 U.S. 609 (1965).

Sellers v. State, 48 Ala. App. 178, 263 So.2d 156 (Ct. Grim.

~ y\pp7 19 /2 ) .

Padgett, v. State, 4 5 Ala. App. 56, 22 3 So. 2d 597 (Ala. Ct.

o’I’ 7 fp p . TlTfuTt) .

Davis v. U.S., 357 F.2d 438 (5th Cir., 1966).

! 15 F .2d 133 (5th Cir., 1963).Onrcia v . U.S . , i

U.S. v . V’right,

Fow 1 o r v . ii.s., :

St ref' l: v . State,

Jones. v. State,

Jj± itlxn;... V . .Sl.a,l(D

3.1

/

A RGUMENT

. I.

THE DENIAL OF CERTIORARI SHOULD BE RECONSIDERED IN

LIGHT OF AN INTERVENING DECISION OF THE SUPREME COURT OF THE

UNITED STATES.

On January 21, 1975, the Supreme Court of the

United States handed down its decision in Taylor v._Louisiana,

43 U.S.L.W. 4167. In that decision, the Court made clear

the relationship between the Sixth Amendment right to trial

by jurv and the Fourteenth Amendment guarantee against the

V

exclusion of blacks from juries. The Court pointed out that

as long ago as the decision in Smith v . Texas, 311 U.S. 128

(1940) , it had lie Id that a jury must be "a body truly

representative of the community." 43 U.S.L.W. at 4169. Thus,

9/ On January 27, 1975, in Da n iol v . Lo u i. s i a n a , 43 U.S.L.W.

3415, the Supreme Court held that the specific holding

of Taylor— that the exclusion of women -from juries vio

lated the Sixth and Fourteenth Amendment guarantee of

ti'ial by a jury representing a cross-section of the

community— would be applied prospectively only, primarily

because of the state's reliance on an earlier decision

of the Court, Hoyt v. Florida, 368 U.S. 57 (1961), that

upheld the exclusion of women. As is discussed in the

text, infra,petit ioner here relies not on that holding

of the Supreme Court, but on the cross-section principle,

which is derived from Supreme Court decisions dating

back to 1940.

12

when, in 1900, the Court.held that the Sixth Amendment

guarantee of trial by jury applied to the states (Duncan

v, Louisiana, 391 U.S. 145), the cross-section requirement

also became binding on the states. The result is that a

state not only must not deliberately exclude cognisable

groups from the jury pool, but also has the affirmative

duty to utilize methods that will in fact result in the

full inclusion of such groups. In its discussion of these

principles, the Court implicitly condemned reliance of a

"hey man" system that resulted in the under-inclusion of

blacks. Dee, 43 U.S.L.W. 4169-70, n. 8, and text.

In the present case, petitioner has relied on the

Sixth Amendment argument and has cited and discussed pre

cisely those cases relied upon by the Supreme Court in Taylor

Thus, this case presents to this Court an ideal opportunity

to give guidance to trial and appellate courts in this State

as to the standards that should, in light of Tay]or and the

Sixth Amendment requirements discussed therein, govern jury

selection procedures, and thereby set standards as to an

important aspect of the administration of justice.

II.

THE DENIAL OF CERTIORARI SHOULD BE RECONSIDERED BECAUSE

THE ALABAMA .COURT OF CRIMINAL APPEALS CLEARLY ERRED IN NOT

FINDING THAT THE DISTRICT ATTORNEY COMMENTED IMPERMISSIBLY

UPON THE FAILURE OF THE DEFENDANT TO TESTIFY.

The record in this case establishes that in the

13

closing argument before the jury which was to adjudicate the

guilt or innocence of the defendant Johnny Daniel Beecher of

the crime charged, the State, by the District Attorney, co

mmented that "No one took the stand to deny it." Defense

counsel objected to the statement and the objection was over

ruled by the trial court. An exception was taken. Subse

quently, defense counsel, outside the presence of the jury,

made a motion for declaration of a mistrial on the grounu

that the statement constituted an impermissible comment on

the failure of the defendant to take the stand.

The closing argument of the prosecution was not

transcribed. However, in a subsequent colloquy of counsel

which was transcribed, defense counsel asserted, and the

District Attorney did not deny, that the Comment had reference

to the testimony of a key' witness for the State, Deputy

Sheriff Kenneth Phillips. (R. 1201, 1202) Mr. Phillips had

testified that while he and the defendant were alone,

awaiting the verdict of the.jury after a previous trial, the

defendant made an inculpatory statement. (R. 1102-1110)

Hr. Phillips' testimony in this respect was the only direct

evidence of the defendant's guilt put before the jury.

The trial court denied the motion for.mistrial.

The Court found that the statement was not violative of

Title 15 § 305 of the Alabama Code nor of the Fifth and

Fourteenth Amendments to the United States Constitution.

14

rr»**-*r**: >r-«~ ** -

The trial court stated:

I don't construe the statement as a

comment on the failure to take the

stand. As I understood it, it was

the — the statement was undenied,

and that has been held to be not a

comment on the statement. (K. 1199)

The Alabama Court of Criminal Appeals affinned the

trial court's ruling by a decision dated October 1, 1974.

Petition for Certiorari, to

denied on January 16, 1975.

the Alabama Supreme Court was

(Three Justices dissented from

the denial of the Writ Mr. Justice. Maddox explicitly

dissented on the ground that he would, review the cpic-.st.ion

concerning the comment of the District Attorney.) Tt is

respectfully submitted that the Court of Criminal Appeals

erred in not finding the prosecutor's staterrw-nL. to )>«.- imper

missible, as will be shown fully below.

Section 305 of the Alabama Code explicitly prohibits

any comment to a -jury by a prosecutor concerning a criminal

defendant's failure to testify, as the Court of Criminal

Appeals properly noted. That section provides:

On the trial of all indictments, com

plaints, or other criminal proceedings, the

person on trial shall, at his own request,

but not otherwise, be a competent witness;

and his failure to make such a request shall

not create any presumption against him, nor

be the subject of comment by counsel. li

the solicitor or other prosecuting attorney

makes any comment concerning, the defendant's

failure to testify, a new trial must bo

granted . . .

This section of the Code pre-dates and is consistent

15

/

with federal, decisional law

right against self-incrimina

Amendments to the United Sto

Fontaine v. Ca 1 i. forni a , 390

Ca1i tornin, 386 U.S. 18 (196

upholding a defendant's cherished

ti.on under the Fifth and Fourteenth

les Constitution. See, c . g .,

U.S. 593 (1960); Chapman v.

7); G r i f f i n v . Ca 3 1 f o r n i.a , 380 U.S.

6 09 (196 5).

jr) construing the statute, the courts of Alabama have

adopted a standard of "reasonable interpretation" based on the

iem. Street v. State, 266 Ala. 209,fa c t s o f each case be fore

96 So .2d 080 (1957). See

4 41 (5th Ci r ., 1966). If

reina rk s before a jury is

defen dan t's failure to fa]

10/

C] j.'. ci i j l.c-d. Sellers v. St.a b

Grim. App. 1972); Sirect ■

to directly call its attention to a

2d 681 (Ct. of App., 1930).

To be sure, in some instances indirect references may

be made by a prosecutor to the failure of the defense to conh.ro-

IQ/ This is so in part because

The office of the solicitor is of the highest .impor

tance; he is the representative of the state, and as a

result of the important functions devolving upon him as

such officer necessarily holds and wields groat power and

influence, and as a consequence erroneous insistences and

prejudicial conduct: upon his part tend to unduly prejudice

and bias the jury against the defendant . . . The test in

matters of this kind is not necessarily that the conduct

of the solicitor complained of did have such effect upon

the jury, but might it have done so?

*J'ay 1 or v . 81<'> to , 116 So. -'ll5 (1928).

16

vert evidence in a case. But such references will be sanctioned

only where the "defendant is not capable of contradicting the

State’s proof. If the prosecutor's remarks can be interpreted

as referring to the failure of the defense to produce as witness

es existing persons other than the defendant who should be in a

position to testify in his favor and who arc known to him, then

the qeneral rule stated above applies and there is no violation

11/

of the statute." Sellers v. State, supra at IS5 __. This is

not such a case. In this case it is plain that the prosecutor's

comment violated the statute and state and federal decisional

lav/.

First of all, there were only two people present in

the room when defendant Beecher presumably made his inculpatory

12/

statement •— Deputy Sheriff Phillips and Mr. Beecher. Thus, any

13/ See also, Garcia v . United States, 315 F. 2d 133, 137 (5th

Cir. 196 3). In Garcia, the Court "found that a reference by

the prosecutor to "uncontradicted" evidence of the defen

dant's guilt did not abridge his Fifth Amendment: rights

only because the remark of the prosecutor could have been

understood by the jury to have reference to the failure of

the defense to call an eyewitness to the crime charged. In

U.S. v. Wright, 309 F.2d" 735 (7th Cir. 1962), the Court rea

soned similarly, stating in support of its finding that the

prosecutor's remark was not improper:

The lanqucige was a general comment on the fact

that the government evidence was wholly unre-

futed. Defendant was not the only one who

could have contradicted the government's testi

mony. The evidence shows that others were present

during several of the conversations or incidents

relied on by the government in support of its case

against defendant. Id. at 739.

12/ At the hearing held by the trial court outside the presence

of the jury on the question of the voluntariness of the

statement, Mr. Beecher denied having made the inculpatory

statement attributed to him by Deputy Sheriff Phillips.

17

reference by the prosecutor that "no one took the stand to

deny it [Mr. Phillips' testimony in this regard]" could

only have drawn the jury's attention to the fact that the

defendant Beecher had not taken the stand. No one else was

in.a position to contest the Deputv Sheriff's version of the

33/

fa els.

Second, even if the prosecutor's remark had been

addressed to the testimony in Die case in general, the remark

]jy/ in Padgett v. State, 45 Ala. App. 56, 223 So. 2d 597 (Ala.

Ct. of App. 1969), on analogous facts, the Court, in a

learned opinion, reversed a conviction on grounds that'

the prosecutor’s remark to the jury could, only have been

interpreted to be an illegal comment on the failure of

the defendant to take the stand. Quoting from State v.

Sinclair, 49 M.J. 525, 231 A.2d 565, the Court said:

"Every time a prosecutor stresses a failure

to present ' testimony, t he facts and circumstances

must be examined to see whether the defendant's

right to remain silent has been violated . . . We

do not mean to preclude the legitimate inferences

from non-production of evidence to which the

prosecutor may fair3.y refer . . . However, in the

present case we think that the repeated remark that

Friedman's testimony was 'uncontradicted' — in view

of the testimony showing that only Sinclair and his

co-defendant could deny the testimony of Friedman —

did raise a danger that the jury would draw an im-.

proper inference from Sinclair's failure to take the

stand."

The Alabama Court of Criminal Appeals, accordingly, re

versed defendant Padgett's conviction since in his case

the on]y person who could have contradicted the State’s

evidence was Mr. Padgett himself.

18

v/ns prejudicial and reversible error. This is so because there

vore no other witnesses known to the defendant who ought to

have been in a position to testify in his favor. Indeed, the

d e f c s e call e d no witnesse s at the trial. Therefore, this

case does not fall within the long line of cases.which have

uphe3 d remarks of the type involved in it because such remarks

have have only indirectly called attention to the defendant's

failure to take the stand. The relationship between the prose

cutor's remark and the defendant's failure to take the stand is

clear and not cast into question by possible interpretation

that the remark, was only an allusion to other potential

witnesses who might have testified in the defendant's behalf.

Third, the Court of Criminal Appeals erred in not

finding the remark of the prosecutor impermissible because it

assigned the burden of proof of showing impropriety of the

remark tc> the defense. The Court said in its opinion in

essence that since it found the context in which the prosecutor

made his remark unclear, the defense had not sustained its

burden of showing impropriety of the remark. This was

plainly improper. In dealing with questions of fundamental

rights, the United States Supreme Coux £ has long held that the

burden of challenging an impropriety by the State is on the

defense, but the burden of proving that no constitutional

abridgement has occurred is on the State. The Fifth Amendment

right against self-incrimination under the United States

19

/

Constitution is the underpinning of the adversarial, as opposed

to inqudsatorial, system of criminal justice. In any criminal

prosecution, therefore, the burden is always on the state to

establish guilt beyond, a reasonable doubt. A conviction based

on anything less than proof beyond a reasonable doubt is an

abridgement of that Fifth Amendment right. So too, any convic

tion based on a record where the State has not established,

where challenged, an absence of an infringement upon a Fifth

Amendment right by a fair preponderance of the evidence is un

lawful. See, e .q ., Lego v. Twome.y, 404 U.S. 477 (1972). In

Lego y . Twomcy, supra, the Court held that the burden of

establishing voluntariness of a confession is on the State; the

burden is not on the defendant to establish invo3.untari.ness.

By parity of reasoning, the same burden must be placed on the

State in this case. Thus, if there was any question as to the

context in which the prosecutor's comment was made in this case,

the Court of Criminal Appeals should have res'olved the question

* 14/in favor of the defendant. Having failed to do this, the Court

Indeed, in Fowler v. United_States, 310 F.2d 66 (5th Cir.

1962), the Court ruled that it could not determine_if

prejudicial comments by the prosecutor in the closing

argument had been made because the closing arguments had.

not been transcribed as was the custom of the trial court.

Absent a reliable record of the proceedings, the Court

found that a new trial must be had, indulging thereby,

every favorable presumption for the defendant.

20

erred in resolving the issue in favor of the State

CONCLUSION

• For the reasons herein set forth, it is respectfully

prayed that this Court reconsider its decision denying a Writ

of Certiorari.

Re s pe c t fu 13. y s ubm i 11 e d ,

U. VI. CLEMONA Do MS, BAKER, & CLEMON Suite 1600 - 2121 Building

2121 Eighth Avenue, North

Birmingham, Alabama 3132 03

ELAINE R. JONES

O’ACK GREEN BE’3010 Columbus Circle

Suite 2030

New Yo r k , 'W. Y . 3.0 019

ATTORNEYS TOR PETITIONER

21

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify that on this 31st day of January,

1075, I have served a ‘copy 'of the foregoing brief on

The Honorable John T. Black

District Attorney

DeKalb County Courthouse

Bax Ic-y,

Building

by mailing a copy of same to thorn, postage prepaid.

Fort Payne, Alabama

The Honorable: Wi.T liam

At Lome y Conors!

State of /Alabama

/vd.minis(rat jvo Office

Montgomery, Alabama

U. V7. C DEMON'