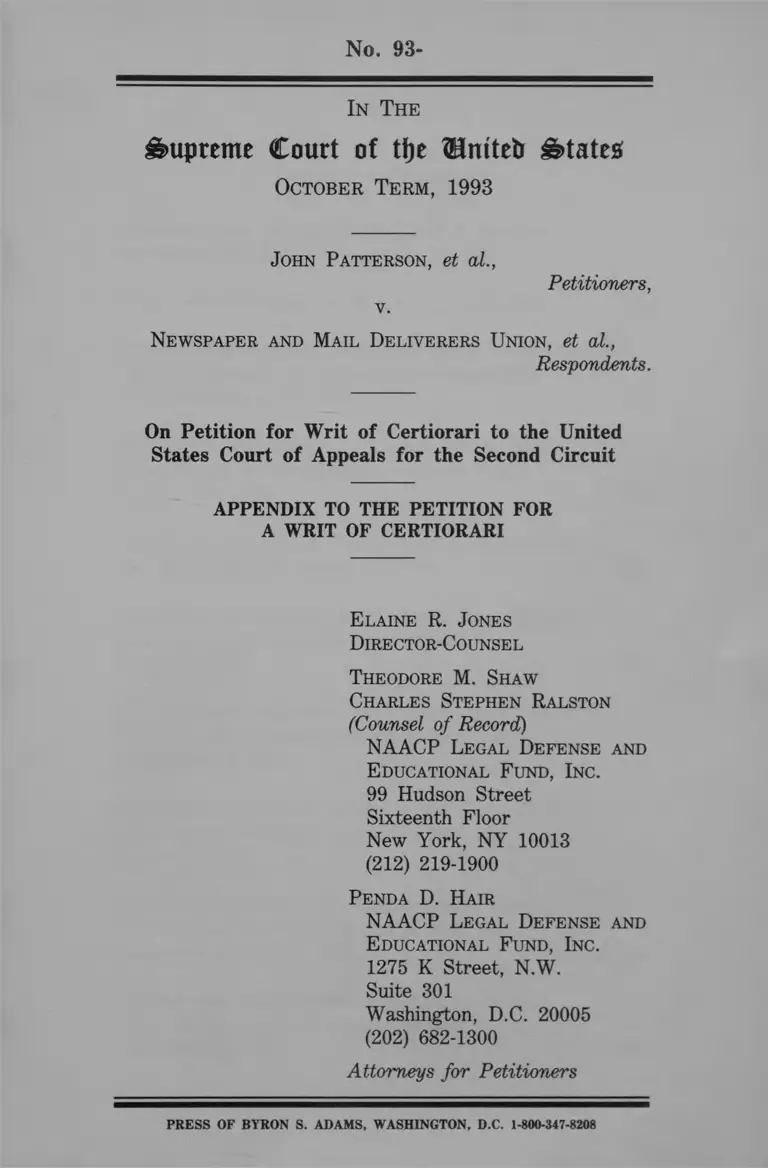

Patterson v. Newspaper and Mail Deliverers Union Appendix to the Petition for a Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

September 19, 1974 - December 20, 1993

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Patterson v. Newspaper and Mail Deliverers Union Appendix to the Petition for a Writ of Certiorari, 1974. 4dcb4fe9-c09a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/6eed2c7a-81fa-402e-adcb-e7845422dcd3/patterson-v-newspaper-and-mail-deliverers-union-appendix-to-the-petition-for-a-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

No. 93-

In T h e

Supreme Court of ttje Unttetr states

O c t o b e r T e r m , 1993

John Patterson, et al.,

v.

Petitioners,

Newspaper and Mail Deliverers Union, et al.,

Respondents.

On Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the United

States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit

APPENDIX TO THE PETITION FOR

A WRIT OF CERTIORARI

Elaine R. Jones

Director-Counsel

Theodore M. Shaw

Charles Stephen Ralston

(Counsel of Record)

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street

Sixteenth Floor

New York, NY 10013

(212) 219-1900

Penda D. Hair

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

1275 K Street, N.W.

Suite 301

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 682-1300

Attorneys for Petitioners

PRESS OF BYRON S. ADAMS, WASHINGTON, D.C. 1-800-347-8208

1

T a b l e o f C o n t e n t s

Decision of the United States Court of Appeals

for the Second Circuit, December 20, 1993 ................ .. la

Order of the Second Circuit Denying Rehearing . . . . 13a

Memorandum Opinion and Order of the United States

District Court for the Southern District of New

York, September 19, 1974 .............................................. 15a

Final Order and Judgment, United States District

Court for the Southern District of New York,

October 25, 1974 ....................................................... 33a

Decision of the United States Court of Appeals for

the Second Circuit, March 20, 1975 .............................. 36a

Memorandum Opinion of the United States District

Court for the Southern District of New York,

June 10, 1980 ................................................................... 55a

Memorandum Opinion of the United States District

Court for the Southern District of New York,

December 15, 1986 .......................................................... 63a

Memorandum Opinion of the United States District

Court for the Southern District of New York,

March 15, 1988 .............................................................. 68a

Opinion and Order of the United States District

Court for the Southern District of New York,

September 25, 1991 ....................................................... 75a

Opinion and Order of the United States District

Court for the Southern District of New York,

September 30, 1991 .................................. 93a

11

Opinion and Order of the United States District

Court for the Southern District of New York,

July 8, 1992 ....................... ........................ ............ . . 100a

Opinion and Order of the United States District

Court for the Southern District of New York,

September 30, 1992 ..................................................... 122a

la

Nos. 1476, 1480 - August Term, 1992

Docket Nos. 92-7964, 6242

United States Court of Appeals

Second Circuit

JOHN R. PATTERSON, ROLAND J. BROUSSARD,

ELMER STEVENSON, on their own behalf and on

behalf of all other persons similarly situated, and EQUAL

EMPLOYMENT OPPORTUNITY COMMISSION,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

v.

NEWSPAPER & MAIL DELIVERERS’ UNION OF

NEW YORK & VICINITY, et. al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

Argued June 21, 1993

Decided December 20, 1993.

Before: NEWMAN, Chief Judge,

VAN GRAAFEILAND and ALTIMARI, Chief Judges.

Appeal from the July 30, 1992, order of the United

States District Court for the Southern District of New York

(William C. Conner, Judge) vacating a consent decree

originally approved in 1974, 797 F. Supp. 1174 (S.D.N.Y.

1992).

AFFIRMED

JON O. NEWMAN, Chief Judge:

2a

This appeal primarily concerns the appropriate

standard for modification of a consent decree in litigation

not involving a governmental entity as a party. The Equal

Employment Opportunity Commission ("EEOC") and a class

of minority employees appeal from the July 30, 1992, order

of the District Court for the Southern District of New York

(William C. Conner, Judge), vacating in its entirety a consent

decree originally approved in 1974. Patterson v. Newspaper

& Mail Deliverers’ Union, 797 F. Supp. 1174 (S.D.N.Y. 1992).

The decree created a comprehensive affirmative action

program for New York City area Newspaper Deliverers. In

addition, the decree contains broad prohibitions against

discrimination and provides for an Administrator to enforce

the anti-discrimination and affirmative action provisions. On

appeal, EEOC and the minority employee class represented

by the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc.

("LDF"), contend that the District Court applied the wrong

standard in deciding whether to modify any aspect of the

decree. LDF argues that none of the decree should have

been vacated; the EEOC argues that the District Court erred

in vacating the anti-discrimination provisions, but takes no

position with respect to the affirmative action program and

the Administrator.

We conclude that the District Court applied the

correct standard and was entitled to vacate the entire

consent decree since its essential purpose had been achieved.

We therefore affirm.

Background

Through closed and union shop agreements,

defendant Newspaper & Mail Deliverers’ Union ("the

Union") controls access to newspaper and publication

delivery jobs in the New York City region. From 1901 to

1952, the Union limited membership to the legitimate first

born sons of other Union members. In 1952, the Union

abandoned its primogeniture system, and, with the

cooperation of the New York City area newspapers and

3a

publishers, adopted a new series of membership and work

rules. This system divided workers into those holding

permanent jobs, which are said to have "regular situations,"

and those employed irregularly, who are called "shapers."

The shapers were further divided into groups with

descending daily hiring priority. Each employer maintained

a "Group I" list, which was restricted to persons who had

once held regular situations in the industry. After offering

daily work to each person on the Group I list, the employer

next looked to an industry-wide Group II list, which

consisted of all persons in the industry on Group I lists or

holding regular situations. Thus, Group II provided an

opportunity for deliverers to supplement their income at an

employer other than their usual employer. If additional daily

work was available, the major employers would look to a

Group III list, which consisted of persons who appeared for

daily work a minimum number of times per week, even if no

work was available. Union membership was limited to

persons holding regular situations, and minorities were

discouraged from joining the Group III lists. Moreover,

although by contract the group lists provided the basis for

filing vacant regular situations, various abuses made it nearly

impossible for anyone to move from Group III to a regular

situation. The Union allowed employees at one employer to

shift to the Group I list of another employer and

occasionally provided Group I status to relatives and

associates of Union members.

In 1973, EEOC and a group of minority deliverers,

who sued for themselves and others similarly situated,

brought separate actions against the Union and the

employers under Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act.

They contended that the 1952 system, although facially

neutral, perpetuated discrimination against minorities. The

cases were consolidated and brought to trial before then-

District Judge Pierce. After all the evidence was presented,

but before the District Court ruled, the parties entered into

a settlement agreement, which Judge Pierce approved and

4a

incorporated into a final judgment. Patterson v. Newspaper

& Mail Delivers’ Union, 384 F. Supp. 585 (S.D.N.Y. 1974).

The judgment directs the Union and employers to implement

and perform the agreement, and retains jurisdiction in the

District Court for enforcement and any subsequent

applications. In a written opinion, Judge Pierce made

detailed factual findings of a long-established pattern of

discrimination against minorities. Statistically, minorities

accounted for 30 percent of the eligible workforce, and only

two percent of deliverers (with an even smaller percentage

among regular situation holders and Group I members). We

affirmed Judge Pierce’s decision over the objection of White

Group III deliverers who complained that the agreement

unfairly favored minorities. Patterson v. Newspaper & Mail

Deliverers’ Union, 514 F.2d 767 (2d Cir. 1975), cert, denied,

427 U.S. 911 (1976).

The settlement agreement contains five sections. The

introductory section consists of a series of "whereas" clauses,

stating that there has been no admission of a violation of law

but acknowledging the existence of a "statistical imbalance"

in minority representation. The final clause of this section

states that the agreement "is designed to correct the

aforesaid statistical imbalance, to remedy and eradicate its

effects, and to put minority individuals in the position they

would have occupied had the aforesaid statistical imbalance

not existed." Section A of the agreement consists of broad

prohibition against any action with a discriminatory effect by

either the Union (H 1) or employers (11 2). Section B of the

agreement creates the office of the Administrator. The

Administrator is authorized to resolve all complaints

involving disparate treatment, subject to review by the

District Court (H 4). His term is fixed as "an initial period of

five (5) years"; subsequently he or his successor "shall remain

in office if and for such time as the Court may direct" (H

6).

Section C of the agreement is a detailed affirmative

action program. The purpose of the program is to achieve

5a

"a minimum goal of 25% minority employment in the

industry . . . by June 1, 1979" (11 7), although the following

paragraph states that this level "is not an inflexible quota but

an objective" (H 8). To achieve this goal, the agreement

provides that all minorities currently in Group III are to be

moved up immediately to Group I (H 9); that regular

situation positions are to be filled exclusively from Group I

by seniority (It 10); that for each regular situation filled, one

Group III deliverer will move up to Group I, alternating

between the most senior minority and most senior

nonminority (H 11); and that Group III vacancies are to be

filled with three minorities for every two nonminorities

(11 15). Various other provisions establish slight variations

for certain employers (1111 12-13), impose some special one

time rules (If 14), limit transfers (HIT 18-19), and require the

Union to offer membership to anyone in Group I (11 20).

Finally, section D of the agreement, entitled "general

provisions," require employers to help qualified individuals

apply for employment (11 28), regulates employment

applications (It 29), requires compliance reports (1111 30-31),

provides for backpay to certain members of the class (1111 37,

39), and provides for continued jurisdiction in the District

Court (H 4). The only provision in section D that arguably

contemplates the termination of the agreement is paragraph

33, which states that inconsistent provisions in collective

bargaining agreements are suspended, but "may be put into

effect when the order terminates, unless the Court orders

otherwise."

By 1979, minority employment was only 13.3 percent,

and Judge Pierce ordered the office of the Administrator

extended for another five years. Patterson v. Newspaper &

Mail Deliverers’ Union, 23 Empl. Prac. Dec. (CCH) U 31,001

(S.D.N.Y. 1980). In 1984, the office was extended on an

indefinite basis. In 1985, the defendants moved to terminate

the order embodying the settlement agreement on the

ground that the 25 percent goal had been reached. In 1987,

Judge Conner, to whom the case has been reassigned, found

6a

that while some employers had reached 25 percent minority

employment, the goal of the settlement agreement was

industry-wide minority representation of 25 percent. Judge

Conner deferred further consideration of the motion until

there was sufficient evidence that this goal had been

attained. In November 1988. Judge Conner concluded that

there was sufficient evidence to suspend operation of the two

ratios in the affirmative action program (i.e., the 50 percent

quota for filling Group I vacancies and the 60 percent quota

for filling Group III vacancies) pending resolution of the

motion.

In May 1991, the Interim Administrator submitted a

report finding an industry-wide figure of 28.53 percent and

substantial compliance by most employers. After the

plaintiffs declined to challenge this figure, the District Court

scheduled a hearing on vacating the entire order. The

private plaintiffs opposed vacation of any part of the decree.

EEOC did not oppose termination of the affirmative action

program, but argued that paragraphs 1, 2, 20, 28, 29, 33, and

41 of the settlement agreement should be retained.

In a comprehensive opinion dated July 8,1992, Judge

Conner concluded that the order should be vacated in its

entirety. He ruled that modem cases have established a

flexible standard for vacating consent decrees, and that this

standard allowed termination of a decree once its primary

purpose had been attained. He rejected the private

plaintiffs’ argument that the decree had to remain in force

until every facet of discrimination was eliminated, and

rejected the EEOC’s argument as a "cut and paste

approach." Plaintiffs filed a motion to amend the judgment

under Fed. R. Civ. P. 59(e), which was denied. However, the

District Court modified its earlier order so as to allow

discrimination claims filed with the Administrator prior to

July 8, 1992, to be processed.

Discussion

I. Legal standard for modification of a consent decree

7a

EEOC primarily contends that the District Court

erred in applying a flexible standard for modification of the

consent decree instead of applying a more rigorous standard.

The rigorous standard urged by EEOC dates from United

States v. Swift & Co., 286 U.S. 106 (9132), in which the

Supreme Court held that an antitrust consent decree could

not be modified unless the defendant showed that the

dangers leading to implementation of the decree had become

"attenuated to a shadow," id. at 119. The Court also held

that "[njothing less than a clear showing of grievous wrong

evoked by new and unforeseen conditions should lead us to

change what was decreed after years of litigation with the

consent of all concerned." Id.

The adoption of a more flexible standard was

intimated in United States v. United Shoe Machinery Corp.,

391 U.S. 241 (1968), in which the Supreme Court cautioned

that the "grievous wrong" standard should not be read out of

context, and allowed the United States to obtain

modification of an antitrust injunction in order to strengthen

restrictions on the defendant. The seminal case actually

applying a more flexible standard is New York State

Association for Retarded Children, Inc. v. Carey., 706 F.2d 956

(2d Cir.), cert, denied, 464 U.S. 915 (1983). Judge Friendly’s

opinion read Swint’s "grievous wrong" language as limited to

the special facts of that case, and found that the appropriate

standard, at least in an institutional reform case, was one of

flexibility, leaving to the District Court a "rather free hand,"

id. at 970. Two recent Supreme Court cases have held that

district courts erred in applying Swift, rather than a more

flexible standard, to the modification of consent decrees or

injunctions in institutional reform cases. In Board of

Education of Oklahoma City Public Schools v. Dowell, 498

U.S. 237 (1991), the Court held that a finding that a school

district was operating constitutionally and unlikely to return

to its past ways mandated the termination of a desegregation

order. In Rufo v. Inmates of Suffolk County Jail, 112 S.Ct.

748 (1992), the Court held that any showing of a significant

8a

change in factual conditions or law would justify a

modification of a decree enjoining double bunking and

requiring officials to build a new prison; the Court remanded

for consideration of whether an upsurge in prison population

had been unforeseen.

In the pending case, the District Court rejected

EEOC’s contention "that this case is governed solely by . . .

Swift", 797 F.Supp. at 1179, and looked to the flexible

standard of Dowell and Rufo. In an important footnote,

Judge Conner noted that though the flexible standard had

previously "only been invoked in cases where the conduct of

a governmental facility or operation was being regulated,"

the present case sufficiently implicated "the public’s right in

seeing that persons are not deprived of fundamental rights"

to come within the "institutional reform exception." Id. at

1180 n.8.

EEOC is probably correct that the District Court’s

decision is the first to explicitly adopt the flexible standard

of Dowell and Rufo, rather than the rigorous standard of

Swift, in a case not involving a governmental entity. It is also

true that the recent Supreme Court cases have each, to an

extent, invoked federalism and democratic rule concerns as

a justification for their use of a flexible standard in the

context of institutional reform litigation, see Rufo, 112 S.Ct.

at 758-59; Dowell, 111 S.Ct. at 637. But New York State

Association makes a more general argument for the flexible

standard, based on the difficulties in implementing any

complex decree in the institutional setting, see, 706 F.2d at

969-70, and the discussion of Swift in each of the leading

cases, as well as in United Shoe, suggest that Swift is a special

case that should not be read as setting down a general

standard for all future cases. See Rufo, 112 S.Ct. at 758

("Our decisions since Swift reinforce the conclusion that the

‘grievous wrong’ language of Swift was not intended to take

on a talismanic quality, warding off virtually all efforts to

modify consent decrees."); Dowell, 111 S.Ct. at 636; United

Shoe, 391 U.S. at 248; New York State Association, 706 F.2d

9a

at 968-69. Moreover, we have suggested in a post-Rufo

decision, Still’s Pharmacy, Inc. v. Cuomo, 981 F.2d 632 (2d

Cir. 1992), that Rufo constitutes a wholesale change, not

limited to institutional reform cases. See id. at 636-37 (citing

District Court decision in this case for approval).

Among other circuits, there appears to be some

dispute as to the appropriate standard for modifying consent

judgments. The Seventh Circuit has flatly declared that Rufo

gave the "coup de grace" to Swift, noting that although Rufo

involved institutional reform litigation, the ‘flexible standard’

. . . is no less suitable to other types of equitable case." In

re Hendrix, 986 F.2d 195, 198 (7th Cir. 1993). Three circuits

have said that Swift’s strict standard has been relaxed in

institutional reform litigation, Lorain NAACP v. Lorain Bd.

of Education, 979 F.2d 1141, 1149 (6th Cir. 1992), cert,

denied, 113 S.Ct. 2998 (1993); W.L. Gore & Associates, Inc.

v. C.R Bard, Inc., 799 F.2d 558, 562 (Fed. Cir. 1992); Epp v.

Kerrey, 964 F.2d 754, 756 (8th Cir. 1992), but two of these

courts have not considered the appropriate standard in

public issues litigation not involving a governmental entity,

see Lorain NAACP, 979 F.2d at 1149; Epp, 964 F.2d at 756,

and one merely declined to apply the flexible standard to

traditional commercial litigation, W.L. Gore, 977 F.2d at 562.

We agree with Judge Conner that the flexible

standard outlined in Dowell and Rufo is not limited to cases

in which institutional reform is achieved in litigation brought

directly against a governmental entity. The "institution"

sought to be reformed need not be an instrumentality of

government. If a decree seeks pervasive change in long-

established practices affecting a large number of people, and

the changes are sought to vindicate significant rights of a

public nature, it is appropriate to apply a flexible standard in

determining when modification or termination should be

ordered in light of either changed circumstances or

substantial attainment of the decree’s objective. Decrees in

this context typically have effects beyond the parties to the

lawsuit, as is true of the provisions for affirmative action

10a

remedies in this case. Though it is important to make sure

that agreements in such litigation are not lightly modified, it

is also important to enter into constructive settlements so

that protracted litigation can be avoided and useful remedies

developed by agreement, rather than by judicial command.

There is an inevitable tension between the objectives of

promoting adherence to agreements and of fostering a

climate in which constructive settlements may be readily

reached. For plaintiffs, the certainty that an agreement will

be enforced without modification is an incentive to negotiate

a settlement that achieves some, though not all, of what

might have been obtained in litigation. For defendants,

however, it is the prospect of modification as circumstances

change or objectives are substantially reached that provides

the incentive to settle on reasonable terms, rather than

adamantly resist in a protracted litigation. The tension

between these competing objectives cannot be eliminated,

but it can and should be sensitively adjusted by courts of

equity, exercising their historic powers both to provide

remedial relief and, when appropriate, to terminate their

authority. We therefore agree with Judge Conner that it was

appropriate to apply a flexible standard in determining

whether to dissolve the decree.

2, Application of the standard

In considering the District court’s decision to vacate

the entire decree, it will be convenient to focus initially on

the affirmative action provisions of the decree. Only the

LDF contends that these provisions should be retained.

LDF does not dispute that minority representation has

reached 25 percent, nor even the District Court’s finding that

minority representation is likely to increase since many white

employees with regular situations are near retirement age

and the Group I and Group III lists contain greater than 25

percent minority representation. LDF also does not dispute

that it would have been proper to suspend the fixed quotas

had the defendants achieved the 25 percent goal by 1979.

But LDF contends that the defendants’ failure to meet that

U a

goal by 1979 requires (a) setting a new goal now,

commensurate with the percentage of minorities in the

qualified workforce, and (b) retaining the hiring quotas until

the new goal is met. LDF states that the 1980 census

showed that minorities constituted 42 percent of the

workforce, and that the 1990 census shows a figure of more

than 50 percent.

LDF relies on Youngblood v. Dalzell, 925 F.2d 954

(6th Cir. 1991), in which the Sixth Circuit reversed the

termination of a consent decree and remanded to the

District Court for further consideration of whether a higher

affirmative action goal should be set after the defendant

failed to meet the goal within the deadline set in the decree.

The decree in that case stated that it was intended to achieve

a "workforce composition which will not support any

inference of racial discrimination in hiring." Id. at 961. The

consent decree in this case could perhaps be read to support

a similar goal. The decree states that it is intended to

remedy a "statistical imbalance," and it is clear that the 25

percent figure was chosen with reference to the 1970 census

figure of a 30 percent minority workforce. Nevertheless, the

decree does not suggest that its purpose is to achieve total

parity, and the 25 percent figure, as a numerical goal, is

stated in absolute terms, without any suggestion that it is

subject to modification. Indeed, the decree suggests that if

any factor is flexible, it is the time limit. Paragraph 6 allows

extension of the office of Administrator beyond five years,

and paragraph 8 states that the 25 percent goal "is not an

inflexible quota but an objective to be achieved by the

mobilization of available personnel and resources of the

defendants hereto in a good faith effort to maximize

employment opportunities for minorities." Both the difficulty

of achieving 25 percent goal and the likelihood that the

percentage of minorities in the blue collar workforce would

increase were foreseeable in 1974. Whether or not the

District Court might have had discretion to raise the 25

percent figure as a remedy for not meeting it is originally

12a

contemplated, the Court was surely entitled to conclude that

such an increase was not required. Finally, with no increase

in the percentage goal, it was proper to dissolve the 50

percent quota for promotions from Group III to Group I

and the 60 percent quota for listings in Group III.

Once the District Court decided that achievement of

the 25 percent goal justified elimination of the affirmative

action provisions, without any increase in the percentage, it

then had to decide whether to vacate the entire decree.

Though other portions of the decree provide the plaintiff

class with enforcement mechanisms for redressing any

ongoing discrimination that may be more expeditious than

the initiation of new litigation, we agree with Judge Conner

that the decree has served its purpose, and that all of its

provisions may be ended. Again, we do not decide that the

District Court was required to vacate these additional

provisions, only that it was entitled to do so. Application of

the flexible standard for modifying decrees in the context of

this lawsuit seeking broad remedies to change hiring

practices entitles a court of equity to focus on the dominant

objective of the decree and to terminate the entire decree

once that objective has been reached.

Affirmed.

13a

Docket Nos. 92-7964, 6242

United States Court of Appeals

Second Circuit

JOHN R. PATTERSON, ROLAND J. BROUSSARD;

ELMER STEVENSON, on their own behalf and on

behalf of all other persons similarly situated, and EQUAL

EMPLOYMENT OPPORTUNITY COMMISSION,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

v.

NEWSPAPER & MAIL DELIVERERS’ UNION OF

NEW YORK & VICINITY, et. al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

Filed February 7, 1994

At a stated term of the United States Court of

Appeals for the Second Circuit, held at the United States

courthouse in the City of New York on the 7th day of

February one thousand and ninety-four.

A petition for rehearing containing a suggestion that

the action be reheard in banc having been filed herein by

Appellant JOHN PATTERSON, ET AL.

Upon consideration by the panel that decided the

appeal, it is

Ordered that said petition for rehearing is DENIED.

14a

It is further noted that the suggestion for rehearing

in banc has been transmitted to the judges of the court in

regular active service and to any other judge that heard the

appeal and that no such judge has requested that a vote be

taken thereon.

FOR THE COURT

GEORGE LANGE, III, Clerk

By:

Carolyn Clark Campbell

Chief Deputy Clerk

15a

Nos. 73 Civ. 3058 and 73 Civ. 4278

Sept. 19, 1974

United States District Court

S. D. New York

JOHN R. PATTERSON, et. al.

Plaintiffs,

v.

NEWSPAPER & MAIL DELIVERERS’ UNION OF

NEW YORK & VICINITY, et. al,

Defendants.

Supplemental Opinion Oct. 11, 1974

MEMORANDUM OPINION AND ORDER

PIERCE, District Judge

This memorandum approves a settlement reached by

all of the parties after a four-week trial on the merits of two

consolidated actions charging employment discrimination in

the newspaper and publication delivery industiy in the New

York City area. The provisions of the agreement are

intended to achieve a 25% minority1 employment goal in the

’"Minority" as it is used in this Settlement Agreement refers to the

definition of that word by the Equal Employment Opportunities

(continued...)

16a

industry within five years. At the present time, minority

employment in the industry is less than 2%; the comparable

percentage of minorities in the relevant labor force in the

New York City area is approximately 30%. The agreement

also provide for supervision of hiring practices and

employment opportunities in the industry to the benefit of

both minority and non-minority workers.

One of the actions has been brought by the Equal

Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) and names

as defendants the Newspaper and Mail Delivery Union of

New York and Vicinity (the Union), the New York Times

(Times), the New York Daily News (News), the New York

Post (Post) and some fifty other publishers and news

distributors within the Union’s jurisdiction. The other action

is a private class action on behalf of minority persons. Both

actions charge that the Union, with the acquiescence of the

publishers and distributors, has historically discriminated

against minorities and that the present structure of the

collective bargaining agreement combined with nepotism and

cronyism and other abuses in employment and referral

practices, have perpetuated the effects of the past

discrimination, in violation of 42 U.S.C. § 2000 et. seq. (Title

VII). Each lawsuit sought an affirmative action program

designed to achieve for minorities the status they would have

had in this industry but for the alleged discriminatory

practices.

Both actions were filed in 1973. After months of

negotiation, the parties reached a settlement agreement in

early 1974 but it was rejected by vote of the Union’s

membership. Following another abortive attempt to obtain

ratification from the membership, the two actions were

consolidated with each other for a hearing on motions for

'(...continued)

Commission and means people who are Black, Spanish-surnamed,

Oriental and American Indian.

17a

preliminary relief before this Court. The hearing

commenced May 14, 1974. At its conclusion on June 12,

1974, the Court ordered the hearing consolidated with trial

on the merits, pursuant to Fed.R.Civ.P. 65(a)(2), giving the

parties the opportunity to present further evidentiary

submissions or testimony. No further evidence was

presented. Instead, the parties having once again entered

into settlement discussions, brought before this Court for

approval a Settlement Agreement dated June 27, 1974,

entered into by all the plaintiffs and all the defendants, and

ratified by the Union membership.

A hearing on the fairness, adequacy and

reasonableness of the Settlement with respect to the

plaintiffs’ class was held on August 27,1974, after due notice

to that class. On the same date the Court also held a

separate hearing on the legality of the relief provided in the

Settlement and its impact on a group of non-minority

workers who had, prior to trial, been permitted to intervene

in the consolidated actions for the purpose of challenging

any affirmative relief which might have affected their

interests.

The Standards

As a general proposition, when a settlement

agreement is presented to the Court for approval, the

Court’s role is limited to the exercise of its equitable powers.

The Court is not to substitute its judgment for that of the

parties. See, e.g.. Glicken v. Bradford, 35 F.R.D. 144, 151

(S.D.N.Y. 1964); United States v. Carter Products, Inc., 211 F.

Supp. 144,148 (S.D.N.Y. 1962). Instead, its role is to assure

that the settlement is fair to the class and the parties, and

represents a reasonable resolution of the dispute. See e.g.,

State o f West Virginia v. Chas. ffitzer& Co., 314 F. Supp. 710

(S.D.N.Y. 1970), aff’d, 440 F.2d 1079 (2d Cir.), cert, denied,

404 U.S. 871, 92 S.Ct. 81, 30 L.Ed.2d 115 (1971). Ordinarily,

the Court is not expected to examine conclusively into the

underlying facts or legal merits of the action. See, e.g.,

18a

Newman v. Stein, 464 F.2d 689, 691 (2d Cir.), cert, denied,

409 U.S. 1030, 93 S.Ct. 521, 34 L.Ed.2d 488 (1972); United

States v. Carter Products, Inc., Supra, 211 F. Supp. at 148.

But, this is not an ordinary case, it must be

recognized that efforts to correct discrimination affect the

strongest public sensitivities. The interests involved are far

broader than those of the particular parties in a particular

lawsuit. Therefore, the parties cannot be permitted to settle

for less than, or for more than, the facts of the case and

public policy expressed in Title VII mandate. Thus, although

the Court is of the opinion that even at this late stage public

policy is served by an agreement rather than an adjudication,

a more searching discussion of the merit is warranted. In

fact, the state of the law in this Circuit may require certain

findings of fact to support affirmative action in a Title VII

case even when it is resolved by settlement. See, Ross v.

Enterprise Association Steamfitters Local 636, 501 F.2d 622,

628 n.4 (2d Cir. 1974), explaining United States v. Wood, Wire

and Metal Lathers International Union, 471 F.2d 408 (2d Cir.

1973), cert, denied, 412 U.S. 939, 93 S.Ct. 2773, 37 L.Ed.2d

398 (1973). Further, a more conclusive examination of the

merits is necessary in this case because the affirmative action

program and the minority goal in principle, and the 25%

minority goal are all vigorously disputed by the intervenors.

Inasmuch as this Court has heard a four-week

completed trial in these actions, it is in a unique position to

find facts and to set forth conclusions of law. Therefore,

what follows shall constitute this Court’s findings and

conclusions to the extent that they form the necessary legal

support for the affirmative action proposed.

The Background

Most of the facts are not contested. The Union is the

exclusive bargaining agent for a collective bargaining unit

encompassing the work performed in the deliverers’

departments of newspaper and publication distributors in the

19a

New York area. Its geographic jurisdiction has been

variously stated, but it is fair to define it by where the

employers in the industry are located: in the metropolitan

area of New York City (within a fifty mile radius of

Columbus Circle), the New York counties of Nassau and

Suffolk, the New Jersey counties of Bergen, Essex, Hudson,

Middlesex, Monmouth, Passaic and Union, and the

Connecticut county of Fairfield.

The nature of the delivery industry is such that the

employers’ needs for delivery department employees vary

from day to day, and indeed, shift to shift, depending upon

the size and quality of the publication(s) being distributed.

Thus, each employer by the terms of the Union contract,

maintains a regular work force (Regular Situation holders)

for its minimum needs, and depends upon daily shapers to

supplement the force. By the terms of the contract, at the

major employers the shapers are categorized into groups

with descending daily hiring priorities. The Group I list of

shapers is restricted, by contract, to persons who have at one

time held a Regular Situation in the industry. They have

first shaping priority at every shift, in order of their shop

seniority. After the Group I is exhausted at any given shift,

the contract provides that the next hiring priority shall go to

Group II members. Group II consists of all persons in

Group I and all persons holding Regular Situations in the

industry. Once all of the Group II members who have

appeared for the shape are put to work, the contract

provides that the remaining open jobs, if any, will go to

Group III members who have appeared for the shape, in

order of their shop tenure.

The shaping system is considerably less structured for

the smaller publications and distributors, and, in fact at the

this time, only the News and the Times maintain Group III

lists of any significant size.

All of the jobs in the industry are within the Union’s

jurisdiction, whether performed by Regular Situation holders

20a

or by any of the members of the various groups, or any one

who shapes at all. The jobs are essentially the same,

regardless of the status of the worker who fills them, and are

all relatively unskilled. Most workers drive trucks or do floor

work. However, because the contract provides that a

Regular Situation is a prerequisite to Union membership,

only Regular Situation holders and members of Group I and

II are Union members.

In theory at least, in addition to structuring the daily

hiring priorities, the Group system also represents the

priority list for filling Regular Situations as they may become

vacant in the newspapers shops.

The Union was founded in 1901, long before the

present Group structured contract was in existence. There

is no evidence to indicate that at that time it had any

minority members (as that term is defined today).

Historically it virtually limited membership to the first bom

legitimate son of a member. The industry had a closed shop

and Union members were consistently hired before non

union men at all industry shapes. In 1952, the industry

adopted the contract which included the rudiments of the

Group structure described above.

It is abundantly clear that the nepotistic policy of the

Union prior to 1952 resulted in discrimination against

minorities. See, e.g., Rios v. Enterprise Association Steamfitters

Local 638, supra, 501 F.2d 622. United States v. Wood Wire

and Metal Lathers International Union, 328 F. Supp. 429, 432

(S.D.N.Y. 1971). The fact that the Union’s intent was not to

discriminate against minorities, but to prefer Union members

and their sons, does not change the basic conclusion. The

effect of such policies, deliberate or not, was to foreclose

minorities from employment in the industry. It is the

discriminatory effect of practices and policies, not the

underlying intent, which is relevant in a Title VII action.

The Group structure, instituted in 1952, appears on

21a

its face to discard these discriminatory policies and to open

up regular employment opportunities and Union membership

to the entire labor force. But, there is uncontroverted

evidence that certain relevant provisions of the contract have

been administered haphazardly, and that the Group structure

has been circumvented by friends and family of Union

members. In practice, the fact is that no non-Union Group

III shaper in the industry has achieved a Regular Situation,

and thus Union membership, by moving up the Group

system since 1963.

Testifying at trial, the Union president credibly

asserted that the Union was not motivated by any intent to

discriminate against minorities, but went on to say that, "I

would be the first to admit that we favor and we are partial

to our members and I’m not ashamed of that." This attitude

is, of course, admirable under most circumstances. There

would be nothing unlawful about its effect under Title VII

providing that minorities, historically, had been provided free

and equal access to Union membership. But the facts

indicate that such is not the case here. And even without

evidence of abuse of the Group system, the statistics alone

reveal the present situation.

There are presently some 4,200 members of the

Union, including some 900 pensioners. More than 99% of

these Union members are White (non-minority).

There are, at present, a total of 2,855 persons actively

working in the industry - this includes Regular Situation

holders (2,460), Group I members (123), and Group III

members (212)} Of the total in these categories, 70 persons

— 2% are Black, Spanish-sumamed, Oriental or American

Indian. Of the 70 minority persons, 28 are scattered among 2

2Group II is not counted here because Group II is constituted of

persons who also hold Regular Situations or Group I positions in

the industry. They are permitted by contract to shape in any shop

other than their own, in addition to their regular job.

22a

the smaller publishers and distributors; 24 work at the News

where the force is approximately 900; work at the Times

where the force is approximately 400; and 1 works at the

Post where the force is approximately 318.

These figures demonstrate that 20 years after the

industry instituted a neutral Group structure of employment

and hiring priorities, the participation of minorities in this

industry is still grossly disproportionate to the percentage of

minority workers in the relevant labor force, which the

EEOC suggests is approximately 30%.3 Even allowing for

the fact that the industry has seen many newspapers

disappear in these last two decades, with a concomitant loss

of jobs, the clear inference from these statistics is that abuses

of the Group structure and indeed the Group structure itself,

is serving -- however unintentionally -- to "lock in" minorities

at the non-Union entry level of the industry, and to thereby

perpetuate the impact of past discrimination on the

minorities with whom these Title VII actions ar concerned.

It is this present impact of past practices which justifies the

affirmative corrective relief embodied in the Settlement

Agreement. See, Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S 424, 91

S.Ct. 849, 28 L.Ed.2d 158 (1971); Rios v. Enterprise

Association Steamfitters Local 636, supra, United States v.

Wood, Wire and Metal Lathers International Union, supra-,

United States v. Bethlehem Steel Corp., 446 F.2d 652 (2d Cir.

1971).

The Terms of the Agreement

As with many resolutions of employment

discrimination cases, the Settlement Agreement in these

actions contains general provisions permanently enjoining the

defendants from discriminatory practices in violation of Title

VII. And, like the judgment in Rios, 360 F. Supp. 979

(S.D.N.Y. 1973) and the agreement in Wood, Wire (68 Civ.

3See p. 593 [pp. 28a-29a of this Appendix].

23a

2116, S.D.N.Y. Feb. 25, 1970), this Settlement Agreement

sets forth a minority employment goal. In this case, it is for

25% minority employment in the industry within five years.4

But, unlike Rios and Wood, Wire, this Settlement Agreement

does not merely commit the parties to the future

development of a plan to achieve that goal. Instead, it sets

forth a plan with great specificity, including variations on the

general theme to account for varying circumstances between

different employers. Such detail indicates that the plan is

the result of hard, serious and good faith negotiations, and

that the different pressures, perspectives and interests of the

parties have been confronted and already resolved. This

serves to increase the Court’s confidence that the plan is

workable, and can be implemented immediately.

The plan is built upon the outline of the present

Group priority structure of the collective bargaining

agreement. It provides for an administrator whose duties

include not only close supervision of the plan, but also of

employment opportunities in the industry on behalf of all

workers. Its major features include elimination of past

abuses of the Group system; elimination of the contract

provision which restricted Group I to former Regular

Situation holders; provision for an orderly flow of Group III

shapers - alternating one minority person with one non

minority person -- into steady and secure employment in the

industry, first as members of Group I and from there, as

Regular Situations become vacant, to Regular Situations.

Union membership will be offered to each Group III worker

as he reaches the bottom of Group I. The plan further

provides that until the 25% minority employment goal is

achieved, employers shall hire, at the entry level, three

“The parties have defined "employment" as encompassing Regular

Situations and Group I positions. Their view is that a place in either

of these two groups represents a steady, secure job in the industry.

The Court agrees, at this time. The definition is subject to revision

by terms of the Settlement Agreement.

24a

minority persons for every two non-minority persons. In

addition, minorities who are presently active on Group III at

the News and the Times will immediately move to the

bottom of the Group I list, with an equal number of non

minorities to immediately follow them into the Group I list.

These minorities will be given pension benefits they would

have earned but for the disadvantages they have

encountered. With the same purpose, funds have been

established by the defendants to provide back pay awards

chiefly to these persons.

The Intervenors’ Objections

The Group III list the News numbers 178. Scattered

throughout the list, in terms of tenure, are 13 minority

persons, the intervenors purport to speak for the other 165

persons on the list, and more broadly for all non-minority,

non-Union workers in the industry.

Most of the provisions of the Settlement Agreement

are applauded by the intervenors, as well they might be. By

regulating employment opportunities in the industry,

unlocking Group III and Group I, Regular Situations and

Union membership, the Agreement will operate beneficially

for the intervenors as well as for the minorities.

The focus of their objection is on the order of the

flow from Group III to Group I. They assert that the flow

ought to be in strict order of tenure on Group III. To

immediately move all of the present Group III minorities to

the Group I list ahead of some non-minorities who have

been listed for a longer period of time on Group III, they

assert, is to engage in "leap-frogging" not intended by Title

VII. Further, they argue, that the system becomes even

more onerous when the provisions for alternating minority

/non-minority elevation to Group I go into effect, because

after the few minorities who have any tenure in the shop are

moved to Group I, the employer will be required to move

minorities with no tenure at all ahead of some present

25a

Group III non-minorities.

The facts selected by the intervenors in support of

their objections are so. And, at first glance their frustration

and anger with this Settlement Agreement is understandable,

and their solution is appealing. These intervenors from

Group III, as individuals, have also suffered the effects of

the Union’s nepotism; they have also attacked the present

practices and abuses in other forums, under different

statutes. Certainly this Court does not accept the argument

that these particular men have benefited from a

discriminatory system.

But, on deeper examination of the Settlement

Agreement and the intervenors’ objections, there are a

number of reasons why this Court does not and indeed can

not, view the intervenors as raising countervailing

considerations of such a substantial nature as to preclude

approval of the plan.

First and dispositive of all the issues raised by the

intervenors, the Settlement Agreement simply does not

trample on their employment opportunities. In the long run,

it must be acknowledged by all concerned that the effect of

this Agreement, if it operates as predicted, will be to achieve

Regular Situation or Group I status for all members of

Group III, minority and non-minority alike, within a

relatively short time-span. Without this Settlement, Group

III workers had little if any hope of ever achieving either

status under the present system. The intervenors do not

contend otherwise. Instead, their objections deal in the main

with interim measures which do, in fact, move some

minorities faster than some non-minorities. But it must be

noted that once a Group III non-minority is elevated to

Group I, his daily shaping opportunities will be no less than

they presently are and indeed they may be greater. The

News projections submitted to this Court indicate that within

a month after implementation of the plan, the non-minority

who is number 47 on the Group III list, and all non-

26a

Minorities above him, will have been elevated to Group I.

The progression thereafter is expected to be approximately

27 non-minority persons to Group I each year. Also the

Settlement Agreement provides other benefits to Group III

non-minorities, not the least of which is the appointment of

an administrator who is empowered to assure that existing

work opportunities in the industry shall be made available to

any Group III person unable to get at least 45 shifts of work

in any calendar quarter.

Further, even if the Settlement Agreement did not

provide non-minorities with these benefits, the intervenors’

position is not factually or legally sound. Their premise is

that the Settlement Agreement will oust them from what

they perceive as vested seniority rights in their Group III

order. If, in fact, this Settlement Agreement affected firm

and realistic seniority rights and expectation of innocent non

minority workers, there could be doubts as to the validity of

the relief afforded. See e.g., United. States v. Bethlehem Steel

Corp., 446 F.2d at 661. But in this case, regardless of the

priority structure of the present contract, and the language

which may be used in it the fact remains that Group III

workers do not have full-time employment, nor do many of

them have any great expectations or intention of working

full-time while they shape from the Group III list. They are

shapers. And, to the extent that the present contract

structure, in theory, gives them certain priorities, by tenure

on Group III, to achieve Regular Situations, the facts have

demonstrated that they could not have any realistic

expectation of such movement actually occurring. As noted

above, no Group III worker has moved up the list to a

Regular Situation since 1963.

Their expectations with respect to daily shape

priorities must be viewed in a somewhat different light.

Then an additional person is placed in front of a shaper,

theoretically his chances of working any particular shift are

decreased by a factor of one job. This, of course, depends

on the stability of the total number of jobs available from

27a

shift to shift and whether or not the new person chooses to

shape the same shift. In other words, assessing a shaper’s

expectation is a highly speculative exercise. The Court does

not mean to minimize a Group III member’s vested

emotional interest in his position at a shape, but it cannot be

equated with the worker who might be "bumped" from a

steady and seemingly secure position by an outside minority

with less seniority than him. Further, it must be pointed out

that even if these shaping priorities were viewed as providing

Firm expectations, "[such] seniority advantages are not

indefeasibly vested rights but mere expectations derived from

a bargaining agreement subject to modification." United

States v. Bethlehem Steel Corp, supra, 446 F.2d at 663.

Indeed, the intervenors themselves recognize this principle

when they approve of many changes made in the collective

bargaining agreement by the proposed Settlement.

Also, it must be said that the relief the intervenors

suggest, which would observe strict tenure of the Group III

list, would most likely not provide the relief mandated by

Title VII for minorities. Given the fact that the active work

force at the News numbers 900 and includes only 24 minority

persons, it would clearly take a far longer period of time to

reach a goal of 25% minority employment. Because the

minority percentage is so low, the same objection holds true

if, as the intervenors have suggested, the Group I and Group

III lists were dovetailed by shop tenure.

Finally, it must not be forgotten that this is a Title

VII case. Such cases, as Judge Frankel has said in Wood,

Wire are launched by statutory commands, rooted in deep

constitutional purposes, to attack the scourge of racial

discrimination in employment. . . . [a]nd we know that, in

addition to the spiritual wounds it inflicts, such

discrimination has caused manifold economic injuries,

including drastically higher rates of unemployment and

privation among racial minority groups." United States v.

Wood, Wire and Metal Lathers International Union, Local

Union 46, 341 F. Supp. 694, 699 (S.D.N.Y. 1972). Title VII

28a

is an expression of a commitment to correct minority

employment discrimination and, hopefully, the vast social

consequences that flow from it and afflict the whole of the

nation. The statute does not undertake to correct all forms

of employment discrimination. Thus, to the extent that what

the intervenors seek here is relief equal to that afforded

minorities, it has no legal foundation, in this case. Under

the law, relief here must be limited to victims of the kind of

discrimination prohibited by Title VII. United States v.

Bethlehem Steel Corp., supra, 446 F.2d at 665. There is no

evidence and no assertion that the intervenors have been

discriminated against on account of race, religion, color, sex,

national origin, or because they have made charges, testified,

assisted or participated in any enforcement proceedings

under Title VII.

The 25% Minority employment Goal

There remains the requirement of Rios v. Enterprise

Association Steamfitters Local 638, supra, 502 F.2d 622, for

reliable factual support for the 25% goal. All of the parties

have agreed to the figure. The EEOC has based its

conclusion on relevant labor force statistics contained in the

tables published by the United States Department of

Commerce in a publication entitled General Social and

Economic Characteristics, 1970 Census of Population, for the

relevant geographic areas of the Union’s jurisdiction. Using

what this Court agrees is the most reliable profile possible of

the candidate for deliverers’ work, the EEOC has extracted

figures for Black males over 16 years of age with a high

school diploma or less. With considerable ingenuity, the

agency has also extrapolated comparable figures for

minorities other than Black. Added together they indicate

that the relevant labor force is 30% minority. Although the

private plaintiffs and the intervenors have submitted other

calculations and bases with respect to minority

representation in the relevant labor force, in this Court’s

view the EEOC analysis is the soundest and provides ample

support for the 25% minority goal included in the Settlement

29a

Agreement.

Conclusion

This Court has found that the affirmative relief

provided in the Settlement Agreement is justified by the

facts of this case. It has found that the 25% minority goal

is supported by reliable statistics. It has found that the

affirmative relief provides members of the plaintiffs’ class

and other minorities with an adequate, fair and reasonable

route to their "rightful place" in this industry and that the

Settlement Agreement is enforceable, legal and in the public

interest. The Court has also found that the Settlement

Agreement does not so interfere with the rights of the

intervenors as to require disapproval.

Therefore, the motion of the parties for approval of

the Settlement Agreement is hereby granted. Settle Order,

upon the consent of the parties endorsed thereon by their

attorneys, accordingly.

So ordered.

SUPPLEMENTAL OPINION and ORDER

On September 19, 1974, this Court filed a

Memorandum Opinion and Order approving the proposed

settlement of these actions. As part of that settlement the

parties agreed to the appointment of an Administrator to

supervise its implementation. While they agreed that the

Court would appoint a person of its own choosing, they

indicated a preference for a particular individual whose

reputation as an experienced person in labor-management

relations is undisputed.

This Court is mindful that given the context of a suit

pursuant to Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964

experience in labor-management relations is not without

significant value to an Administrator. But this is not to say

that under all circumstances an Administrator in a Title VII

action must be recruited from the ranks of the labor-

30a

management specialists. There are instances, and the Court

believes this to be one of them, when other qualities may

assume greater importance in meeting the commitment to

the broad social policies which underpin the 1964 Act.

The Administrator appointed in these consolidated

actions will be charged with the responsibility of seeing that

the terms of the Settlement Agreement under Title VII of

the Civil Rights Act of 1964 are diligently and

conscientiously implemented. This Act was designed

primarily to protect, and provide a more effective means to

enforce, the civil rights of persons within the jurisdiction of

the United States. It aims, inter alia, to eliminate

discriminatory practices by business, labor unions, or

employment agencies and thereby to encourage the growth

of economic opportunities for minority individuals, thus

strengthening the economic foundation essential to the full

enjoyment of civil rights. When President Lyndon B.

Johnson signed the 1964 Act he declared that its overriding

social goal was "to promote a more abiding commitment to

freedom, a more constant pursuit of justice and a deeper

respect for human dignity."

In light of these broad national purposes, this Court

considers it of paramount importance that the Administrator

it appoints here possess a finely tuned sensitivity to the social

impact of past discriminatory employment practices, and a

balanced sense of dedication and commitment to the

elimination of these practices.

Further, while in some cases the very nature of the

industry in which the Settlement Agreement is to operate

and the unusual complexity of its labor-management

problems may dictate the appointment of an individual with

a background in labor-management relations, such is not the

case here. Here, the Court is concerned with an important

but relatively small and centralized industry involving the

deliveiy of newspapers, magazines, books, etc. The

bargaining unit of the Newspaper and Mail Deliverers’

31a

Union encompasses only about 3,000 employees most of

whom are employed by the three major newspapers in the

New York City metropolitan area. Given these

characteristics, this Court finds that experience in labor-

management relations need not be the major consideration

which should guide the Court in its appointment of an

Administrator.

This finding is buttressed by the fact that the

Settlement Agreement here is quite detailed and specific.

Were such an Agreement broad in its terms, the

Administrator would be faced with the need to establish

procedures, define specific objectives, and develop the

methods to be employed. In such an instance, an

Administrator with an extensive background in labor-

management work and possibly even familiarity with the

industrial unit involved would seem to be indicated. In

contrast where the Settlement Agreement is highly detailed,

as here, the responsibilities of the Administrator are clearly

defined and consequently, his discretion is accordingly more

circumscribed and the need for a particular expertise

becomes correspondingly less important.

Not to be disregarded, of course, in appointing an

Administrator is the assessment of the proposed

Administrator by the parties. Since their respective interests

clearly will be affected by the Court-appointed Settlement

Agreement, there should be some assurance that there is

confidence in the person to be appointed. In this case, the

proposed Administrator is said to be completely satisfactory

both to the private plaintiffs and to the EEOC. While it is

true that the defendants have not expressed like sentiments,

their reservations are centered on the proposed

Administrator’s lack of experience in labor-management

relations. But, as the Court has already indicated, such

experience while frequently desirable and even essential

should not always be the prevailing consideration. Sensitivity

to the broad social purposes of civil rights legislation and the

disposition to fairly and adequately administer the agreement

32a

are qualities which in this Court’s view, in this case outweigh

whatever lack of expertise may exist. Further, the parties

herein have demonstrated a commendable spirit of

cooperation which the Court confidently expects will

continue during the implementation state of these

proceedings. To that extent the Administrator’s task will be

made immeasurably less difficult.

Having carefully considered the matter in light of the

principles briefly discussed above and after a careful review

of a number of qualified men and women who might be

available for appointment, the court has decided to appoint

the person named in the Court’s letter of September 11,

1974 as the Administrator.

It is so ordered.

33a

No 73 Civ. 3058

No. 73 Civ. 4278

Filed October 25, 1974

United States District Court

Southern District of New York

JOHN R. PATTERSON, et al.,

Plaintiffs,

v.

NEWSPAPER & MAIL DELIVERERS’ UNION OF

NEW YORK AND VICINITY, et. al.,

Defendants.

EQUAL EMPLOYMENT OPPORTUNITY

COMMISSION

Plaintiff,

v.

NEWSPAPER AND MAIL DELIVERERS’ UNION OF

NEW YORK AND VICINITY, et al.,

Defendants.

JAMES LARKIN, DOMINICK VENTRE, FRANK

CHILLEMI, GERALD KATZ, et al.,

INTER VENORS.

34a

FINAL ORDER AND JUDGMENT

Upon the consent of the parties, endorsed hereon by

their attorneys, and upon the Settlement Agreement between

the parties, dated June 27, 1974, and attached hereto as

Exhibit A, and upon this Court’s Memorandum Opinion and

Order approving the Settlement Agreement, dated

September 19, 1974, and upon this Court’s Supplemental

Opinion and Order, dated October 11, 1974, appointing

William S. Ellis, Esq., as the Administrator, it is hereby

ORDERED, ADJUDGED AND DECREED:

1. The Settlement Agreement is hereby approved

as a basis for settlement of these actions and the defendants

in these actions, including those in default, are hereby

directed to implement and perform the Settlement

Agreement in accordance with its terms and with the

provision of this Order and Judgment.

2. Failure to comply with this Order and

Judgment, including breach of the Settlement Agreement,

shall be punishable as a contempt of court.

3. A copy of the Settlement Agreement and of

this Order and Judgment shall be kept available and

displayed by all defendant employers in a permanent place

where notices to their delivery department employees are

usually posted and by defendant union in a prominent place

at the union’s offices.

4. This Order and Judgment and the Settlement

Agreement shall be binding upon plaintiffs and all members

of the class or classes they represent, and defendants and

their officers, agents, servants, employees, assigns, and upon

those persons in active concert or participation with them

who receive actual notice of the order by personal service or

otherwise.

5. William S. Ellis, Esq., is hereby appointed as

the Administrator under the Settlement Agreement, and he

35a

shall be compensated at an hourly rate of $65.00 plus

expenses.

6. This Court’s temporary restraining order of

March 19, 1974, extended by consent of the parties on April

5, 1974, until the entry of this final order, is dissolved as of

the effective date of this Final Order and Judgment.

7. These actions are hereby marked "settled,"

with prejudice and the Court hereby retains continuing

jurisdiction over these actions for the purpose of the

enforcement of compliance with this Order and Judgment

and the Settlement Agreement and the punishment of

violations thereof, and for the purpose of enabling any of the

parties to apply to the court for such further orders and

directions as may be necessary or appropriate.

8. This Order and Judgment shall take effect on

November 11,1974, and any application to the United States

District Court for a stay thereof shall be made in writing and

not later than October 29, 1974, at 10:00 O’clock a.m.

Dated: New York, New York

October 24, 1974.

United States District Judge

36a

No. 626

Docket No. 74-2548

Argued Jan. 9, 1975

Decided March 20, 1975

United States Court of Appeals

Second Circuit

JOHN R. PATTERSON, et al,

Plaintiffs,

v.

NEWSPAPER AND MAIL DELIVERERS’ UNION OF

NEW YORK & VICINITY, et. al,

Defendants-Appellees,

EQUAL EMPLOYMENT OPPORTUNITY

COMMISSION,

Plaintiffs,

v.

NEWSPAPER AND MAIL DELIVERERS’ UNION OF

NEW YORK AND VICINITY, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees

DOMINICK VENTRE, et al.,

Intervenors.

37a

Before: FEINBERG, MANSFIELD and OAKES,

Circuit Judges

MANSFIELD, Circuit Judge:

At issue on this appeal is the appropriateness of relief

against discrimination in the employment of news deliverers.

In the past we have been called upon to review relief granted

in cases where discrimination has been established under

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. § 2000

et seq., including the use of minority percentage goals and

affirmative hiring and promotion programs. See, e.g., Rios v.

Enterprise Assn. Steamfitters, Local 638, 501 F.2d 622 (2d Cir.

1974); Bridgeport Guardians, Inc. v. Bridgeport Civil Serv.

Comm., 482 F.2d 1333 (2d Cir. 1973); United States v.

Bethlehem Steel Corp., 446 F.2d 652 (2d Cir. 1971). The

present appeal presents several variations on the theme.

Unlike previous cases the affirmative relief under attack here

does not result from an order of the district court entered

after a determination of the merits of the action but from a

settlement agreement between the plaintiffs, who are

minority persons seeking employment as news deliverers, the

defendant Newspaper and Mail Deliverers of New York and

Vicinity ("the Union" herein), and the Government. The

settlement was reached after a four-week trial in the

Southern District of New York before Lawrence W. Pierce,

Judge, who approved the agreement. The person challenging

the relief is not an aggrieved minority employee but a white

non-union worker, James V. Larkin, who, having been

permitted to intervene, seeks to set aside the agreement as

unlawful on the ground that it affords benefits to minority

38a

workers1 not given to similarly situated white workers,

regarding the advancement rate and diluting the work

opportunities of these white workers.

Because he had heard a four-week trial in this case

and because of the public interest involved in a Title VII

action. Judge Pierce considered in a thorough opinion the

merits of the plaintiffs’ action and the conformity of the

settlement to the goals of Title VII and the rights of the

parties. See, 384 F.Supp. 585 (S.D.N.Y. 1974). We find no

abuse of discretion in Judge Pierce’s approval of the

settlement and therefore affirm.

The appeal arises out of the two consolidated actions.

One was brought by the Equal Employment Opportunity

Commission against the Union, the New York Times

("Times" herein), the New York Daily News ("News" herein),

the New York Post ("Post" herein), and about 50 other news

distributors and publishers within the Union’s jurisdiction.

The other is a private class action on behalf of minority

persons. Both complaints allege historic discrimination by

the Union against minorities, and charge that the present

structure of the Union’s collective bargaining agreement and

the manner of its administration by the Union perpetuate

the effects of past discrimination in a manner that violated

Title VII. The defendant publishers are alleged to have

acquiesced in these practices. Appellant Larkin is one of

approximately 100 white non-union "Group III" workers at

the News who are given permission to intervene under F.R.

Civ. P. 24(a)(2) because of their potential interest in the

relief to be fashioned.

The Union is the exclusive bargaining agent for the

collective bargaining unit which embraced all workers in the

delivery departments of newspaper publishers and of

The term minority" as used herein means persons who are Black,

Spanish-surnamed, Oriental and American Indian. "White" or "non-

minority" refers to all other persons.

39a

publications distributors in the general vicinity of New York

City, including, in addition to the city proper, all of Long

Island, northeastern New Jersey counties, and north to

Fairfield County, Connecticut. Of 4,200 current Union

members, 995 are white.

Due to variations in the size and quantity of

publications to be distributed, the needs of distributors for

delivery personnel vary from day to day and from shift to

shift. For that reason the work force in the industry is

separated by the Union agreement into (1) those holding

permanently assigned jobs ("Regular Situations") and (2)

those called "shapers," who show up each day to do whatever

extra work may be required on that day. The work

performed by persons in both categories is unskilled.

Shapers are divided into four classifications, Group I-IV. the

order in which shapers are chosen for extra work on each

shift is determined according to Group number and by shop

seniority of members within each group.

Group I, the highest priority group, consists solely of

persons who once held Regular Situations in the industry.

Each employer maintains his own Group I list, which is

comprised of persons who have been laid off from Regular

Situations at other employers, or who have voluntarily

transferred from Regular Situations or from classifications as

Group I shapers at another employer. When a Regular

Situation becomes available, the highest seniority person on

the employer’s Group I list is offered the position.

Group II is an aggregate list compiled from the entire

industry and consists of all Regular Situation holders and

Group I members. Taking priority after Group I is

exhausted, it enable regular and Group I members to obtain

extra daily work at employers other than their own.

Major employers maintain a Group III list, which

consists of persons who have never held a Regular Situation

in the industry. Members of Group III are given daily work

40a

priority after Group II. To maintain Group III status,

workers are required to report for a certain number of

"shapes" each week. Prior to the settlement agreement

under review Group III members are theoretically entitled

by shop seniority to any Regular Situation that become

available, if the Group I list had been exhausted. Group IV

shapers are last in priority and are required to appear for a

shape far less frequently than Group III shapers.

Although the Union represents all delivery workers,

membership is limited to Regular Situation holders and

Group I members. Historically the Union has excluded

minorities and has limited its membership to the first bom

son of a member. Aside from the chilling effect which

restriction of Union membership to whites might in itself

have upon minority persons seeking delivery work, there is

evidence that minorities were also discouraged from gaining

entrance to Group III lists, even though Group III shapers

are not members of the Union. Of 2,855 persons now

actively seeking work in the industry (which includes 2,460

Regular Situation holders, 123 Group I shapers, and 273

Group III shapers only 70, or 2.45%, are minority persons.

While the current Group Situation which was adopted

in 1952 appears on its face to open Union membership to

anyone in the labor force, Union membership, because of lax

administration of the contract provisions, has largely

remained attainable only by the family and friends of a

Union member. Due to artificial inflation of the Group I

lists, no person has in practice made the theoretically

possible jump from Group III to a Regular Situation since

1963. The evidence suggests that this expansion of the

Group I lists has been accomplished primarily by use of

voluntary transfers of Group I or Regular Situation holders

from the lists of smaller distributors to the Group I lists of