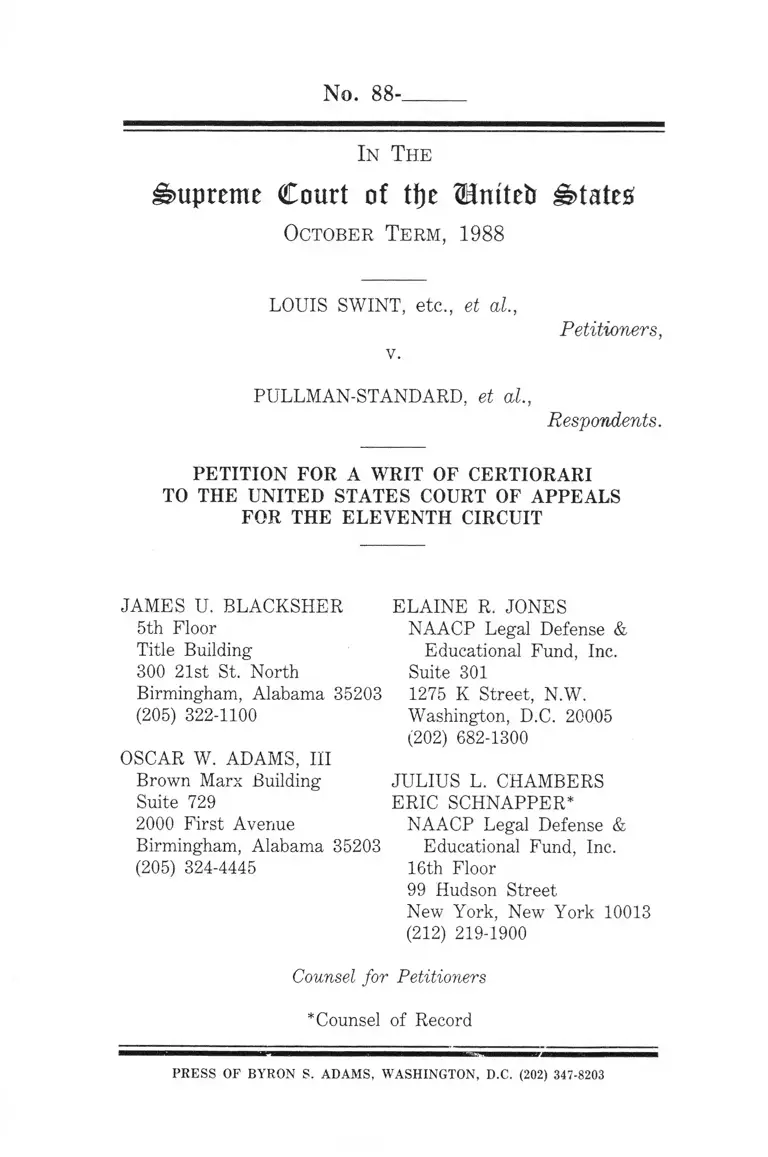

Swint v. Pullman-Standard Petition for Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

October 3, 1988

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Swint v. Pullman-Standard Petition for Writ of Certiorari, 1988. 405cbbaf-c59a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/6f150585-d1e2-4c3c-acfa-06cecb407251/swint-v-pullman-standard-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed February 20, 2026.

Copied!

No. 88-

In The

S u p re m e C o u r t o f t\)t U n itc t i s ta te s

October Te r m, 1988

LO U IS SW IN T, e tc ., e t a l.,

P e t i t i o n e r s ,

V.

P U L L M A N -ST A N D A R D , e t a l.,

R e s p o n d e n ts .

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI

TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE ELEVENTH CIRCUIT

JA M E S U. B L A C K S H E R E L A IN E R. JONES

5th F loor N A A C P Legal Defense &

Title Building Educational Fund, Inc.

300 21st St. N orth Suite 301

Birmingham, A labam a 35203 1275 K Street, N .W .

(205) 322-1100 W ashington, D.C. 20005

(202) 682-1300

O SC A R W . A D A M S, III

B row n M arx Building JU LIU S L. CH A M BE R S

Suite 729 E R IC SC H N A PPE R *

2000 First Avenue N A A C P Legal Defense &

Birmingham, Alabam a 35203 Educational Fund, Inc.

(205) 324-4445 16th F loor

99 Hudson Street

N ew Y ork, N ew Y ork 10013

(212) 219-1900

C ou nsel f o r P e tit io n er s

* Counsel o f Record

press OF BYRON S. ADAMS, WASHINGTON, D.C. (202) 347-8203

1 .

QUESTIONS PRESENTED*

Does the plaintiff or the

defendant bear the burden of proof as to

whether a seniority system is "bona fide"

under section 703(h) of Title VII and

Teamsters v. United States, 431 U.S. 324

(1977)?

2. Where an employer or union

engages in intentionally discriminatory

seniority practices whose purpose and

effect is to nullify or violate the

nominal seniority rights of blacks, is

their seniority system nonetheless "bona

fide" so long as those discriminatory

* Most of the discriminatory

seniority practices at issue in this case

were originally adopted before 1965, the

effective date of Title VII. One of the

issues raised in Lorance v. A.T.& T. Technologies. No. 87-1428, is whether

intentionally discriminatory seniority practices are immune from attack if those

practices were adopted prior to the

effective date of Title VII. (See pp.

32-34, infra.

i

seniority practices are not explicitly set

forth in the nominal written seniority

rules?

3. Where a written seniority

system was framed for the express purpose

of discriminating on the basis of race,

may an employer nonetheless invoke the

"bona fide seniority system" exception of

section 7 03 (h) on the ground that it was

the union which sought and framed the

racially motivated provisions, and that

the company agreed to that racially

motivated system simply to accommodate the

wishes of the union?

4. Did the lower courts err in

failing to determine whether discrimina

tory intra-departmental seniority

practices continued after 1965?

PARTIES

The petitioners are Louis Swint,

Willie James Johnson, William B. Larkin,

Spurgeon Seals, Jesse B. Terry, Edward

Lofton, and the class of all black workers

employed at the Bessemer plant of Pullman-

Standard between 1965 and 1974.

The respondents are Pullman-Standard,

a division of the Pullman, Inc., the

United Steelworkers of America, AFL-CIO,

Local 1466 of the United Steelworkers of

America, the International Association of

Machinists, and Local 372 of the

International Association of Machinists.

iii

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Questions Presented........ i

Parties ...................... iii

Table of Contents ............. iv

Table of Authorities ......... . vii

Opinions Below ................ 2

Jurisdiction .............. . . . . 4

Statutory Provisions Involved *. 4

Statement of the Case..... 5

Statement of the Facts ........ 10

(1) Seniority Rules Govern

ing Intra-Department

Promotions ......... 11

(a) Prior to 1965 ..... 11

(b) Subsequent to 1965 . 12

(2) The Division of Existing

Integrated Departments

Into All-White and All-

Black Seniority Units ... 15

(3) The Creation of New

Single Race Departments . 20

(4) The Racially Motivated

1965 Training Require

ment ................... 2 4

Page

iv

Page

Reasons for Granting the Writ .. 28

I. Certiorari Should Be

Granted To Resolve A Conflict Among the Circuits As To Whether

The Bona Fides of A

Seniority System Is

Controlled By Actual Seniority Practices, Or

Turns Solely on the

Substance of the Nominal Written Seniority Rules .. 35

II. Certiorari Should Be Granted To Resolve A Conflict Among the Circuits As To Whether Section 703(h) Provides a "Bona Fide Seniority

System" Defense to An

Employer Which Agrees to and Enforces Seniority

Rules Framed And Proposed By A Union for the

Purpose of Discriminating on the Basis of Race .... 44

III. Certiorari Should Be

Granted To Resolve A Con

flict Among the Circuits

As to Which Party Bears the Burden of Proof

Regarding Whether a

Disputed Seniority SystemIs a Bona Fide .......... 53

Conclusion .................... 63

v

Page

Appendix

Opinion of the Court of Appeals,

April 4, 1983 ............ . la

Opinion of the District Court,

September, 198 6 .......... . 5a

Memorandum Opinion, District

Court, November 25, 1986 ... 41a

Order, District Court,

November 25, 1988 ....... 54a

Opinion of the Court of Appeals,

September 21, 1988 ........ 58a

Opinion of the Court of Appeals,

January 3, 1989 ........... 212a

vi

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases: Page

Acha v. Beame, 570 F.2d 57(2d Cir. 1978) 35

American Tobacco Co. v.

Patterson, 456 U.S. 63(1982) 29,30

Bernard v. Gulf Oil Corp.,841 F.2d 547 (5th Cir.

1988) 54

California Brewers Ass'n v.Bryant, 444 U.S. 598(1980) 29,30

County of Washington v. Gunther,452 U.S. 161 (1981) 59

Crosland v. Charlotte Eye, Ear

and Throat Hosp., 686 F.2d

208 (4th Cir. 1982) 55

EEOC V. Ball Corp., 661 F.2d 531(6th Cir. 1981) 53-54

EEOC v. Westinghouse Elec. Corp.,725 F.2d 211 (3d Cir. 1983). 55

Gantlin v. West Virginia Pulpand Paper Co., 734 F.2d 980

(4th Cir. 1984) 57,58

Jackson v. Seaboard Coastline R.Co., 678 F.2d 992

(11th Cir. 1982) 56

vii

Cases: Page

Keyes v. School District No. 1,

413 U.S. 189 (1973) ___.... 63

Larkin v. Pullman-Standard,

854 F.2d 1549 (11th Cir.(1988) 2

Lorance v. A.T. & T.

Technologies, No. 87-1428 .. Passim

Mitchell v. Mid-Continent

Spring Co., 583 F.2d 275

(6th Cir. 1978) 36

Mozee v. Jeff Boat, Inc.,

746 F.2d 365 (7th Cir.1984) 36

Nashville Gas Co. v. Satty,

434 U.S. 136 (1977) ........ 42,59

Pullman-Standard v. Swint,

456 U.S. 273 (1982) ........ 3,9,51

Robinson v. Lorillard,

444 F.2d 791 (4th Cir.(1971) 48

Sears v. Atchison, T. & S.F.Ry.Co., 645 F.2d 1365

(9th Cir. 1981) 47,48

Smart v. Porter Paint Co.

630 F.2d 490 (7th Cir.

1980) 55

Swint v. Pullman-Standard,11 FEP Cas. 943

(N.D.Ala. 1974) 3,7,14,24

viii

Cases; Page

Swint v. Pullman-Standard,

539 F.2d 77 (5th Cir.1976) 3,7,12,14

Swint v. Pullman-Standard,15 FEP Cas. 144

(N.D.Ala. 1977) 3,8

Swint v. Pullman-Standard

17 FEP Cas. 730(N.D.Ala. 1978) 3,8,22

Swint v. Pullman-Standard,

624 F.2d 525 (5th Cir.1980) ............... 3,9,17,19,22

Swint v. Pullman-Standard,692 F.2d 1031

(5th Cir. 1983) ........... 3

Teamsters v. United States,

431 U.S. 324 (1977) ....... Passim

Trans World Airlines v. Hardison

431 U.S. 63 (1977) 43,60

Trans World Airlines v. Thurston,469 U.S. Ill (1985) 59

United Airlines v. Evans,

431 U.S. 553 (1977) 29

United States v. First City

Nat. Bank, 386 U.S. 361 (1967) 58

ix

Cases; Page

Wattleton v. International

Brotherhood of Boilermakers,686 F.2d 586 (7th Cir.

1982) 37

Other Authorities:

Title VII, Civil Rights Act

Of 1964 ................ 4,43,50,52

Section 703(a), Civil Rights Actof 1964 ............... 4

Section 703(h), Civil Rights Act

of 1964 ................... Passim

28 U.S.C. § 1254 (1) 4

Age Discrimination in

Employment Act ............ 5 4 , 5 9

Equal Pay Act .................. 59

Rule 52, Federal Rules of

Civil Procedure ........... 9

2A Moore's Federal Practice .... 60

x

NO. 88-

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

October Term, 1988

LOUIS SWINT, etc., et al..

Petitioners.

v.

PULLMAN-STANDARD, et al..

Respondents.

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE ELEVENTH CIRCUIT

Petitioners Louis Swint, etc., et

al., respectfully pray that a writ of

certiorari issue to review the judgment

and opinion of the Court of Appeals for

the Eleventh Circuit entered in this

proceeding on September 21, 1988.

2

OPINIONS BELOW

The decision of the Eleventh Circuit

is reported at 854 F.2d 1549 (11th Cir.

1988), sub. nom. Larkin v. Pullman-

Standard. and is set out at pp. 58a-211a

of the Appendix; the portions of that

opinion of particular relevance to this

petition are set out at parts IA and V of

the opinion pp. 64a-68a and 166a-184a.

The Court of Appeals decision denying

rehearing, which is not yet reported, is

set out at pp. 212a-215a of the Appendix.

The Eleventh Circuit opinion reviewed

three earlier district court orders, dated

Sept. 8, 1986, Nov. 25, 1986 and Nov. 25,

1986; these orders, none of which are

officially reported, are set forth at pp.

5a-40a, 41a-53a and 54a-57a, respectively,

of the Appendix. Part III of the

September, 1986, opinion (App. 23a-31a),

3

deals with the issues raised by this

instant petition.

This case, which has been pending for

18 years, was the subject of two previous

appeals, one of which was heard in this

Court. The previous reported opinions, in

chronological order, are as follows:

Swint v. Pullman-Standard. 11 FEP

Cas. 943 (N.D.Ala. 1974)

Swint v. Pullman-Standard. 539 F. 2d

77 (5th Cir. 1976)

Swint v. Pullman-Standard. 15 FEPCas. 144 (N.D.Ala. 1977)

Swint v. Pullman-Standard, 15 FEPCas. 1638 (N.D.Ala. 1977)

Swint v. Pullman-Standard, 17 FEPCas. 730 (N.D.Ala. 1978)

Swint v. Pullman-Standard, 624 F. 2d525 (5th Cir. 1980)

Pullman-Standard v. Swint, 456 U.S.273 (1982)

Swint v. Pullman-Standard. 692 F. 2d1031 (5th Cir. 1983) (App. la-

4a)

4

JURISDICTION

The original decision of the Eleventh

Circuit was entered on September 21, 1988.

A timely petition for rehearing was denied

on January 3, 1989. (App. 212a-215a).

Jurisdiction of this Court is invoked

under 28 U.S.C. § 1254(1).

STATUTORY PROVISIONS INVOLVED

Section 703 (a) of Title VII of the

1964 Civil Rights Act, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-

2(a), provides in pertinent part:

It shall be an unlawful practice for an employer —

(1) to ... discriminate against any

individual with respect to his

compensation, terms, conditions,

or privileges of employment,

because of such individual's race....

Section 703(h) of Title VII, 42 U.S.C.

§ 2000e-2(h), provides in pertinent part:

Notwithstanding any other

provision of this title, it

shall not be an unlawful

employment practice for anemployer to apply different __terms, conditions, or privileges

of employment pursuant to a bona

5

fide seniority ... system provided that such differences

are not the result of an intention to discriminate....

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

The procedural history of this

litigation is summarized in part II of the

Fifth Circuit's 1986 opinion (70a-98a).

This Title VII action was originally filed

in 1971 by several black employees at the

Bessemer, Alabama, plant of Pullman-

Standard. The plaintiffs alleged that the

company and the United Steelworkers (USW)

had engaged in a variety of racially

discriminatory practices, and that the

effects of those discriminatory practices

were perpetuated by the seniority system

in effect at the plant.

The nominal terms of the seniority

system were embodied in two collective

bargaining agreements, one between

Pullman-Standard and the Steelworkers, and

a second between Pullman-Standard and the

6

International Association of Machinists

(IAM). The two unions represented

different, albeit closely related

departments in the same plant. There

were, for example, two separate

Maintenance Departments, one represented

by the USW and the other represented by

the I AM. The seniority rules in the

Pullman-Standard-IAM agreement directly

affected the promotion and transfer rights

of Pullman-Standard employees in USW

represented departments, since that

agreement required any worker in a USW

unit to forfeit all seniority if he or she

moved into an IAM represented department.

The case was originally tried in

1974. The district court held that the

seniority system at the Bessemer plant did

not have any discriminatory effect. The

court acknowledged that most blacks had

been assigned to particular departments on

7

the basis of race, and that the seniority

system — which forfeited all seniority

rights of any person transferring to a new

department — locked blacks into those

departments. The district court reasoned,

however, that the departments to which

blacks had been assigned on the basis of

race were in fact as desirable as the

departments to which most whites had been

assigned. Swint v. Pullman-Standard. 11

FEP Cas. 943 (N.D.Ala. 1974). In 1976 the

Court of Appeals, noting that virtually

none of the higher paying jobs at the

plant were in the units to which blacks

were restricted by the seniority system,

reversed and remanded for further

proceedings. Swint v. Pullman-Standard.

539 F.2d 77 (5th Cir. 1976).

While the case was pending on remand,

this Court decided Teamsters v. United

States, 431 U.S. 324 (1977), which held

8

that Title VII permitted the use of a

seniority system which perpetuated the

effects of prior discrimination, so long

as the system was bona fide. In light of

Teamsters. the district court in 1977 held

an additional hearing on the bona fides of

the seniority system at the Bessemer

plant. Swint v. Pullman-Standard. 15 FEP

Cas. 1638. The district court concluded

that the system was indeed bona fide.

Swint v. Pullman-Standard. 17 FEP Cas. 730

(N.D.Ala. 1978).

The Court of Appeals in 1980 again

reversed, holding that the district

court's finding of bona fides rested on

subsidiary findings which were either

tainted by errors of law, or were clearly

erroneous. The appellate court concluded

that the evidence demonstrated that the

seniority system was not bona fide. Swint

v. Pullman-Standard. 624 F.2d 525 (5th

9

Cir. 1980). This Court granted certiorari

to consider whether the Court of Appeals

had erred in deciding itself whether the

system was bona fide, rather than

remanding the case for reconsideration by

the district court. The Court held that

Rule 52, Federal Rules of Civil Procedure,

required that the district court be

afforded an opportunity to reassess the

bona fides of the system in light of the

subsidiary errors identified in the

circuit court's 1980 opinion. Pullman-

Standard v. Swint. 456 U.S. 273 (1982).

On remand in 1986 the district court

again upheld the seniority system as bona

fide. (App. 23a-31a). On appeal the

Eleventh Circuit affirmed. (App. 166a-

184a). Petitioners had prevailed on

several other claims, and the company

filed a timely petition for rehearing with

regard to those aspects of the case. The

10

petition for rehearing was denied (App.

212a-215a).1

STATEMENT OF FACTS

The dispute in the instant case

regarding the bona fides of the seniority

system turns on four seniority related

practices, described below. In most

instances the lower courts agreed that the

seniority related practices were racially

motivated, but held that the seniority

system was nonetheless bona fide.

(1) Seniority Rules Governing Intra-

Department Promotions 1

1 The instant petition, like the

relevant portions of the Eleventh Circuit

decision, is concerned with whether the

seniority system at issue is bona fide

within the meaning of section 703(h). In

the context of this litigation, however,

resolution of the section 703(h) issues

has somewhat broader ramifications for the

parties. The Eleventh Circuit properly

recognized that a subsidiary finding of

post-Act discrimination, even if based on evidence originally adduced primarily to

show non-bona fides, might also entitle petitioners as well to a remedy for that

post-Act discrimination as such. (App. 153a-157a).

11

(a) Prior to 1965

In 1954 the ostensible seniority

system required that promotions within a

given department be awarded to the most

senior department employee in a lower

level position.2 It is undisputed,

however, that prior to 19 65 the actual

seniority practice was entirely different.

The district court3 and the Eleventh

Circuit4 agreed that at least until 1965

z App. 66a; 456 U.S. at 278-79.

3 11 FEP Cas. 943, 947 and n. 12(N.D.Ala. 1974); 15 FEP Cas. 144, 147 n.

7, 148 (N.D.Ala. (1977); 17 FEP Cas. 730,733 (N.D.Ala. 1978).

4 App. 64a-65a:

"[P]rior to 1965 ... [t]here

were ..., within each mixed-race

department, 'white7 jobs and

'black' jobs, meaning that when

a particular job was vacated, it was necessarily filled with an employee of the same race. The

'white' jobs tended to be the higher paying; and the 'black' jobs the lower paying."

12

the seniority system was avowedly racial

in nature, since only whites could promote

into "white" jobs, while black in the same

department were limited to lower paying

"black" jobs. Thus if a vacancy arose in

a "white" job, it was awarded to the most

senior white worker, regardless of whether

one or more blacks in the unit actually

had more departmental and plant seniority,

(b) Subsequent to 1965

There is an unresolved dispute

as to whether this race based seniority

practice in fact ended in 1965, or

continued for years thereafter. At the

1974 trial petitioners introduced

extensive testimony that the old "white"

jobs were still being filled by less

senior whites in place of more senior

See also 539 F.2d 77, 83 (5th Cir. 1976).

13

blacks.5 Black witnesses testified that

the company frequently did this by

providing training only to the white

employees in lower level positions, and

then deeming the more senior blacks

ineligible because they lacked that

training.6 Petitioners asked that this

systematic disregard of the seniority

rights of blacks be ended, in part, by an

order requiring the company to post a

notice of all vacancies.

In its 1974 opinion the district

court, although refusing to order any

posting of vacancy announcements, did not

decide whether the pre-Act race based

5 See e.q.. R.v. 3, pp. 56-62, 81,103-04, 126-32, 160-61, 191, 210-12; R.v.4, pp. 311-13, 341-42, 375-76, 471, 481,

528; R.v. 5, pp. 534, 580; R.v. 6, pp.840, 847, 895.

6 See. e.q., R.v. 3, pp. 103, 105,126-28, 139-45,, 207-09, 238-42; R.v. 4,pp. 262, 342, 347-48; R.v. 5, pp. 615-16,

630; R.v. 6, p. 753, 923-24, 948, 951-52.

14

promotion system had continued after 1965.

11 FEP Cas. at 959. The court of appeals

in 1976 directed the district court, inter

alia, to reconsider its denial of the

requested posting order. 539 F.2d at 102.

In its 1977-78 opinions, however, the

district court inexplicably failed to do

so. When the case was again remanded in

1984, petitioners reiterated their

contention that the seniority system for

promotions had even after 1965 been

administered in a discriminatory manner,

and sought to introduce additional

evidence to supplement the extensive

testimony adduced on this subject at the

1974 trial. (App. 30a n. 25).

In its 1986 opinion, the district

court acknowledged that that record

contained evidence of such discrimiantory

application of the seniority system, but

insisted that consideration of that issue

15

was outide the scope of the remand. (App.

3 0a n. 25) . On appeal the Eleventh

Circuit apparently agreed that its 1983

remand order did not permit the district

court to decide whether discriminatory

intra-departmental seniority practices

continued after 1965. (App. 181a). Thus,

none of the numerous lower court opinions

in this case has ever decided, on the

basis of the record at the 1974 trial or

otherwise, whether the discriminatory

operation of the seniority promotion

system ended in 1965 or at a later date.

(See App. 67a n. 10).

(2 ) The Divis ion of Existina

Intearated Deoartments Into All-

White and All-Black Senioritv

Units

Prior to 1940 there was a single,

racially integrated Maintenance Department

and a single, racially integrated Die and

Tool Department. In 1941 each of these

departments was subdivided into separate

16

single-race seniority units, an all-white

Maintenance Department and an all-white

Die and Tool Department, both represented

by the International Association of

Machinists, (App. 64a) and an all-black

Maintenance Department and Die and Tool

Department, and Die and Tool Department,

both represented by the United

Steelworkers. The salary levels were

generally higher in the jobs placed in the

IAM represented departments. Also in 1941

Pullman-Standard agreed with the IAM to a

seniority rule which forbad any person in

the all-black Maintenance or Die and Tool

Departments to use his company or

departmental seniority when bidding on

jobs in the IAM represented Maintenance

and Die and Tool Departments. This

unusual dual system of two Maintenance

Departments and two Die and Tool

Departments continued in existence until

17

the plant closed in 1980, as did the

seniority rule creating separate seniority

rights and rosters for the duplicate

departments.

Both courts below agreed that this

dual system was established at the behest

of the IAM, and that the IAM's purpose in

framing this dual was to create a

seniority system that would prevent blacks

in Maintenance or Die and Tool jobs from

promoting into the better paid all-white

positions represented by the I AM. App.

25a and n. 20, 173a; 624 F2 at 532-33.

Although the IAM was the prime mover

behind this deliberately discriminatory

seniority system, it was Pullman-Standard

which actually enforced that system,

maintaining the separate seniority rosters

for the dual system, and refusing to

credit time worked in the all-black units

in making promotions into or within the

18

duplicate IAM units. The company

expressly agreed to and signed with the

IAM the collective bargaining agreement

which provided for these seniority rules.

The company has never claimed that it was

unaware of the IAM's motives, nor could it

plausibly do so. The IAM's constitution

in 1941, and for years thereafter,

expressly limited membership to whites.

(App. 25 n. 20) When the NLRB certified

the IAM, against its wishes, as the

representative of some 24 blacks from the

original Maintenance and Die and Tool

Departments, the IAM "ceded" those

positions to the USW, effectively

transferring them from the IAM represented

unit to the USW represented unit, and thus

stripping them of the rights they enjoyed

under the original NLRB certification to

bid on the better paid jobs represented by

19

the IAM.7 Until 197 0 the company only

hired whites into the two IAM departments.

From the effective date of Title VII,

until the plant closed in 1980, this

racially motivated seniority arrangement

was enforced by the company against any

person in a USW Maintenance or Die and

Tool job who sought to move into the

better paid Maintenance and Die and Tool

jobs represented by the IAM. There is no

question that these seniority rules, had

they been administered by the IAM, would

not have been "a bona fide" seniority

system. The Eleventh Circuit reasoned,

however, that both the dual departmental

system and the seniority rules effectively

prohibiting transfers from the black to

the parallel white units were bona fide

seniority systems because they were

administered instead by Pullman-Standard,

7 624 F .2d at 531.

20

which had not divided the original

integrated departments on its own

initiative, but merely did so to

accommodate the wishes of the racially

motivated IAM. (App. 173a-175a).

(3) The Creation of New Single Race Departments

Prior to 1950 virtually all the

departments represented by the USW were

racially mixed although, of course, blacks

could not be promoted into "white" jobs in

their departments. In 1954 the defendants

created out of the mixed departments 8 new

single race departments, 5 all-white and 3

all-black. (See App. 64a). The creation

of these new single race units had a

severe effect on the nominal seniority

rights of blacks. Those black workers

moved into all-black departments lost the

right to be promoted without seniority

forfeiture into jobs in their former

departments. Black workers in departments

21

from which "white" jobs were removed could

no longer use their nominal seniority

right to promote into those jobs. These

new departments and attendant transfer

barriers became of decisive importance

when, at an undetermined point after the

adoption of Title VII, black employees

were finally permitted to promote into

white jobs in their own departments.

During the 1978 hearing regarding the

bona fides of the seniority system,

petitioners urged that the redrawing of

these departmental lines to create 8

single-race departments was racially

motivated. The district court in 1978

made no finding as to whether this 1954

gerrymandering of departmental lines was

racially motivated; the trial court merely

commented that the new departmental lines

22

were "rational." 17 FEP Cas. at 734-37.8

On appeal the circuit court held that this

finding of rationality was clear error,

and went on to hold that "[t]he

establishment and maintenance of the

segregated departments appear to be based

on no other considerations than the

objective to separate the races." 624

F.2d at 531; see also id. at 532. When

the case was in this Court, the defendants

urged the Court to overturn the circuit

court's holding on this issue, and to find

that the creation of the 8 single-race

departments was the result of legitimate

See, e.g., 17 FEP Cas. at 735

("while the company's apparently

unilateral creation of a separate Inspector's department ... can be seen as

having a racial impact (all the inspectors were white), this change was certainly rational.")

23

considerations.9 This Court declined to

do so.

On remand in 1984-86 we again urged

that the creation of the 8 single race

departments was racially motivated. The

district court's 1986 opinion contained no

discussion whatever of this issue. On

appeal the Eleventh Circuit read this

Court's opinion to criticize appellate

reconsideration of the district court's

1978 finding that the new departmental

lines of rational. (App. 177a N. 44) .

The latest circuit court decision appears

to reinstate the 1978 district court

holding that those lines are rational.

The district court, however, never decided

whether those lines, even if rational,

y Brief for Petitioners, Nos. 80-

1190 and 80-1193, pp. 18, 40, 10a-16a.

24

were in fact racially motivated? that

question remains, at best, unresolved.10

(4) The Racially Motivated 1965

Training Requirement

Under the seniority system, as it

existed before and after 1965, a vacancy

in a higher paying job was to be filled,

in theory, by the most senior department

employee in a lower level position. Prior

to 1965 the normal practice was to give

the senior worker whatever on-the-job

training was needed to perform the work

involved. In some instances the senior

employee would be given such informal

training prior to the actual reassignment;

in other instances he would be trained

after being promoted. 11 FEP Cas. at 947

n. 16. The most important application of

this on-the-job training practice was with

10 Petitioners maintain that the 1980 finding of racial motivation, not

having been overturned by this Court, remains the law of the case.

25

regard to welders, since two-thirds of the

best paid positions at the Bessemer plant

were welder jobs. Prior to 1965, of

course, welder was a "white" job, and

welder vacancies were awarded to the most

senior white in the lower levels of the

welding department, even though there were

blacks in the department with far greater

seniority.

In 1965, following the enactment of

Title VII and a related arbitration

proceeding, blacks in the welding

department had a clear right to be

considered for the white welder jobs.

Virtually all the more senior department

workers below the welder level were black,

and blacks would have won the vast

majority of welder jobs had promotions

been made — as the ostensible seniority

system had always required — on the basis

of seniority. At this juncture, Pullman-

26

Standard radically changed the system for

selecting new welders; it declared that no

worker could utilize his seniority to

promote into a welder job unless he first

acquired welding experience, or completed

a welding training program, outside the

Bessemer plant. The company eliminated

the long-standing on-the-job training

program, and announced that it would

refuse even to test the welding skills of

workers who had claimed to have learned

those skills at the Bessemer plant itself.

This change in rules effectively

nullified the seniority rights of the

blacks in the Welding Department. In the

following 6 years, only 26 of the 198

black welder helpers, all with substantial

seniority, were promoted to welder

positions. During the same period 417

newly hired whites, all with less

seniority than the black welder helpers,

27

became welders.11 The company admitted

that it had abolished on-the-job training,

and substituted an outside training

requirement, because its white welders

refused to obey orders to train black

workers.11 12 Both the district court13 and

11 PX 12, 18; Exhibit Appendix,No. 74-3726 (N.D.Ala), pp. 65X, 275X.

12 The key Pu11man-Standard

supervisor explained:

"Q. [W]hy didn't Pullman just go out and

tell the White employees to start training the Black employees.... [W]hy didn't Pullman go tell the White employees that were on the

higher jobs to start training the Black employees that .had the seniority?

A. "Well, mister, ... there is no man

can force me to train somebody I

don't want to train. Those fellows

in their estimation, they had a valid

reason for not training me with 40 years service and they didn't have

but 15 because it was taking bread and money out of his mouth and

pocket. In other words, people were caught in that they were victims of a situation they had no control over."

(R.v. 14, transcript of hearing of May 1,

1984, pp. 127-28). Counsel for the

28

the Eleventh Circuit14 agreed that this

change in the seniority rights of blacks

in the welding department was the result

of intentional racial discrimination.

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE WRIT

Twelve years ago, in Teamsters v.

United States. 431 U.S. 324 (1977), this

Court held that under section 703 (h) of

Title VII an employer may engage in

practices which perpetuate the effects of

past discrimination so long as those

company offered the same explanation.

(R.v. 13, transcript of hearing of April30, 1984 pp. 162-63.)

3 lE><3i^nS

14 App. 167a and 167a n. 39:

" [I]n 1965, after it appeared that all jobs at the plant would have to

be opened to persons of all races,

Pullman abandoned its earlier

practice of offering on-the-job training in welding...."

"A Pullman official admitted that the practice changed because white

welders at the Bessemer plant were

unwilling to train black employees."

29

practices are part of a "bona fide"

seniority system. Decisions of this Court

in the intervening years have repeatedly

increased the importance of the section

703(h) exception to Title VII.15 But

although this Court has repeatedly granted

certiorari to resolve procedural issues

arising under section 703(h), neither

Teamsters nor its progeny attempted to

delineate when and under what

circumstances past discrimination in

Xi3 United Airlines v. Evans. 431 U.S. 553 (1977), extended the exemption to

seniority systems which perpetuate the

effect of discrimination occurring after the adoption of Title VII. American

Tobacco Co. v. Patterson. 456 U.S. 63 ( 1982 ) , extended the exemption to seniority systems adopted after 1965. California Brewers Ass'n v. Bryant. 444 U.S. 598 (1980), adopted an expansive view of what practices are to be deemed part of a seniority system for purposes of section 703(h).

30

connection with a seniority system would

render that system non bona fide.16

In the absence of guidance from this

Court, the lower courts have been faced

with, and have disagreed about, a number

of recurring legal issues concerning the

bona fides of a seniority system. The

instant petition presents several of the

most important of those questions — (1 )

Where the bona fides of a seniority system

is in dispute, which party bears the

burden of proof? (2) When is an

intentionally discriminatory seniority

practice sufficiently connected to the

xt> In both Teamsters and Evans the plaintiffs conceded that the seniority

system at issue was bona fide. Teamsters

v. United States. 431 U.S. at 355-56;

United Airlines v. Evans. 431 U.S. at 560.

in American Tobacco and California Brewers

the bona fides of the systems had not yet

been tried, and this Court simply directed

that that issue be addressed on remand. American Tobacco Co. v. Patterson. 456

U.S. at 77 and n. 18; California Brewers Ass'n v. Bryant. 444 U.S. at 610-611.

31

seniority system to render that system

non-bona fide?17 (3) If a discriminatory

seniority practice is adopted at the

behest of a union in order to discriminate

against blacks, is the seniority system

nonetheless bona fide when enforced by the

employer?

The questions posed by the instant

case are essentially legal; the courts

below either agreed that the particular

seniority related practices at issue were

racially motivated, or concluded that the

disputed seniority system could be upheld

without deciding whether the remaining

disputed seniority practices were indeed

racially motivated. The recurring nature

' Because in part of its view on the first two issues, the Eleventh Circuit

never resolved whether racially

d i sc riminatory intra-departmental seniority practices continued after 1965.

Question 4 of the Questions Presented is

inextricably intertwined with, and turns on, Questions 1 and 2.

32

of these issues is illustrated by the fact

that arguments touching on all three

questions have been raised by the briefs

in Lorance v. A.T.& T. Technologies. No.

87-1428.

We set out below the particular

circumstances which warrant review of the

section 703(h) issues raised by this case.

We acknowledge, however, that it may be

appropriate to defer action on this

petition until the Court has decided

Lorance v. A . T. & T. Technologies. The

respondents in Lorance maintain that a

finding that a seniority system is not

bona fide can never be based on the

adoption prior to 1965, the effective date

of Title VII, of intentionally discrimina

tory seniority rules or practices.18 in

18 See, e.g., B r i e f for Respondents, No. 87-1428, p. 41 n. 46:

" [N] o Title VII claim can be brought

unless the facts showing the lack of

33

the instant case the bona tides of the

seniority system turns on the legal

significance of four seniority related

intentionally discriminatory practices;

three of these were adopted prior to the

effective date of Title VII.19 A decision

bona fides occurred during the

limitations period.... Whatever reasons may have entered into the

initial adoption of a seniority system, a neutral system that is

maintained and applied free of unlawful discrimination during the limitations period is, under Section

703(h), not a violation of Title VII."

(Emphasis in original). Pre-1965 actionsadopting a racially motivated seniority

practice necessarily occur outside any Title VII limitations period. Respondents

in Lorance insist that this Court's own prior decision in Swint. although

apparently concerned with pre-Act

discriminatory actions in the adoption of the instant seniority system, " [p] resumably" was concerned in fact only with post-1965 discriminatory practices. Id. at 43.

19 The division of the Maintenance

Department and the Die and Tool Department

into separate single race seniority units occurred in the 1940's. 624 F.2d at 531.

The undisputed practice of allowing only

34

sustaining the position of respondent in

Lo ranee would not necessarily be

controlling in this case, because the

underlying claims are significantly

different. See pp. 60-62 infra.

Nevertheless, it is possible that the

decision ultimately rendered in Lorance

will bear significantly on the

certworthiness of the instant case, or on

the propriety of remanding this case to

the Eleventh Circuit for reconsideration

in the light of Lorance.

white department members to bid on white

jobs in their department was adopted long before 1965. (See p. 11-12, supra). The

creation of new single-race departments

out of previously integrated USW

departments occurred between 1954 and 1965. (See pp. 21-23, supra).

35

CERTIORARI SHOULD BE GRANTED TO

RESOLVE A CONFLICT AMONG THE

CIRCUITS AS TO WHETHER THE BONA FIDES OF A SENIORITY SYSTEM IS

CONTROLLED BY ACTUAL SENIORITY

PRACTICES, OR TURNS SOLELY ON THE SUBSTANCE OF THE NOMINAL

WRITTEN SENIORITY RULES

Until the Eleventh Circuit decision

in the instant case, the circuit courts

were in agreement that the "seniority

system" whose bona tides must be assessed

under section 703(h) is the set of actual

seniority practices adhered to and

utilized by the defendant employer. The

Second Circuit in Acha v. Beame. 570 F.2d

57 (2d Cir. 1978) , held that although

written seniority rules might be facially

neutral and have originally been created

for non-discriminatory reasons, if in

practice those rules were administered in

a discriminatory manner the system would

I.

36

not be bona fide within the meaning of

section 703(h):

Bona f ides. in the context of

the statute requires, at least

in part, that the seniority-

system be applied fairly and

impartially to all employees.

. . . A system designed or

operated to discriminate on an illegal basis is not a "bona fide" system.

570 F. 2d at 64. In Mitchell v Mid-

Continent Spring Co.. 583 F.2d 275 (6th

Cir. 1978), the ostensible rules governing

inter-shift transfers made no overt

distinctions on the basis of sex. The

Sixth Circuit, however, found the

seniority system was not bona fide under

section 703(h) because other evidence

established that, despite the nominally

sex-neutral rules, the company in fact

maintained separate seniority rosters for

men and women, and would only consider

transfer requests from male employees.

563 F. 2d at 280-81. In Mozee v. Jeff

37

Boat. Inc.. 746 F.2d 365 (7th Cir. 1984),

the official seniority policy required

promotion of "the most senior 'qualified'

employee" seeking each position. The

Seventh Circuit held that, in order to

ascertain whether the company in fact had

a bona fide seniority system, it was

necessary to determine "whether there

might have been discrimination in the

identification of qualified applicants."

746 F. 2d at 374. In Wattleton v.

International Brotherhood of Boilermakers.

686 F. 2d 586 (7th Cir. 1982), the Seventh

Circuit held invalid a seniority system on

the ground that it had been "operated to

discriminate on an illegal basis," citing

evidence that blacks had not in practice

been permitted to transfer into certain

"white" jobs. 686 F.2d at 591-93.

Had this case arisen in the Second,

Sixth or Seventh circuits, each of those

38

circuits would for two distinct reasons

have declared Pullman-Standard'’s seniority

system non-bona fide as a matter of law.

First, all the lower courts in the instant

case have agreed that at least until 1965

the actual seniority system for intra-

departmental promotions at Pullman-

Standard was to promote the senior white

employee if the vacancy were in a white

job, and the senior black employee if the

vacancy were in a black job. (See pp. 11-

12, supra). Had the written seniority

rules drawn such racial distinctions, they

would of course have been non-bona fide;

the Second, Sixth and Seventh Circuits

insist that the result is the same

regardless of whether, as here, the actual

race based seniority rules were not

reflected in the nominally race-neutral

written seniority rules. Second, in 1965

Pullman-Standard made a fundamental change

39

in its seniority practices, thereafter

refusing to permit an employee to utilize

his or her seniority to obtain a promotion

unless the worker first obtained training

outside the plant, at his or her own

initiative, to do the job in question.

(See pp. 24-28, supra). Pullman-

Standard' s officials expressly conceded,

and the Eleventh Circuit acknowledged,

that this change was the result of white

opposition to permitting senior blacks to

use their seniority to promote into better

paying jobs. (See pp. 27-28, supra).

Neither this new limitation on seniority

rights, nor the reason for it, were

reflected in the written seniority rules;

nonetheless, in the Second, Sixth and

Seventh Circuits such a racially motivated

change in actual seniority rights would

also have rendered the system non-bona

fide as a matter of law.

40

The Eleventh Circuit, however, held

that as a matter of law these same facts

required a conclusion that Pullman-

Standard seniority system was bona fide

under section 703(h). The Eleventh

Circuit reasoned that the "seniority

system" at issue was the nominal written

seniority system, which was facially

neutral and which reflected no 1965 change

in seniority rights. To the Eleventh

Circuit, the undisputed racial discrim

ination in the seniority practices was

only tangential evidence, and legally

insufficient evidence at that, regarding

the bona fides of the facially benign

system. The two discriminatory seniority

practices, the court of appeals insisted,

were not themselves part of the seniority

system, but constituted merely

"manipulation" of the nominal "system."

[N]one of this evidence goes

directly to Pullman's intent

41

regarding the system. It tends to prove instead that Pullman

engaged in a number of other, s e p a r a t e discriminatory

practices ...

(App. 175a) (Emphasis in original).

For a plaintiff to prevail . . .

there must be a finding that

the system itself was negotiated or maintained with an actual

intent to discriminate.

(App. 171a) (Emphasis in original).

Evidence that the seniority

system has been manipulated can

certainly be considered in

evaluating an employer's intent

with respect to the creation or

maintenance of a seniority

system . . . but a system cannot be invalidated on such evidence

standing alone.

(App. 171a n. 43) (Emphasis added)

On the Eleventh Circuit's view

section 703(h) prohibited a finding of

non-bona fides based on evidence,

"standing alone," that despite the

existence of a nominal, facially neutral

written system, the actual seniority

practices were deliberately and

42

pervasively based on the race of the

affected employees. Although no other

circuit distinguishes in this way between

a nominal seniority system, and actual

seniority practices, the defendants in

Lorance v. AT&T Technologies. No. 87-

1428, appear to advocate such an

interpretation of Title VII.20

The Eleventh Circuit rule conflicts

as well with the decisions of this Court.

In Nashville Gas Co. v. Sattv. 434 U.S.

136 (1977), the disputed seniority system,

as here, was neutral on its face? the

Court nonetheless held the seniority rule

at issue was unlawful because other

evidence demonstrated that in practice it

penalized only women. Compare 434 U.S. at

20 Respondent's Brief, No. 87-1428,

p. 31 n.3 3 (if "a seniority system was discriminatorily administered ... the relief in such cases is to remedy the

particular discrimination, not to dismantle the entire system.")

43

140 with 434 U.S. at 140 nn.2-3. See also

Trans World Airlines v. Hardison, 432 U.S.

63, n. 14 (1977). The distinction adopted

by the Eleventh Circuit in this case is an

engraved invitation to subterfuge. An

employer can pursue race based seniority

practices, and simultaneously retain the

protections of section 703(h), simply by

adopting facially neutral seniority rules

which are completely different from its

actual racial seniority practices. On the

Eleventh Circuit's view of Title VII, the

nominal written rules, although frequently

or uniformly ignored in practice, would be

the real "seniority system", and the

actual discriminatory practices would be

mere "manipulation", neither inconsistent

with section 703(h) nor sufficient by

themselves to support a finding that the

largely theoretical "seniority system" was

not bona fide.

44

CERTIORARI SHOULD BE GRANTED TO RESOLVE A CONFLICT AMONG THE

CIRCUITS AS TO WHETHER SECTION

703(H) PROVIDES A "BONA FIDE SENIORITY SYSTEM" DEFENSE TO AN

EMPLOYER WHICH AGREES TO AND

ENFORCES SENIORITY RULES FRAMED AND PROPOSED BY A UNION FOR THE

PURPOSE OF DISCRIMINATING ON THE

BASIS OF RACE

The vast majority of the seniority

systems in American industry today are

established by collective bargaining

agreements between employers and unions.

Although Teamsters observed that the bona

fides of a seniority system would turn on

whether the system was created or

maintained for a discriminatory purpose,

Teamsters did not address how section

703(h) should be interpreted in a case in

which an employer and union acted with

different motives. Such differences, of

course, are common under the collective

bargaining process, in which provisions

sought and favored by only one party are

II.

45

agreed to in exchange for provisions

sought and favored by the other. The

Fourth and Ninth Circuits hold that a

racial motive on behalf of either party

renders a joint seniority system non-bona

fide; the Eleventh Circuit, on the other

hand, has expressly rejected that

interpretation of section 703(h).

In the instant case the Eleventh

Circuit held that a seniority system

framed for the purpose of racial

discrimination is nonetheless a "bona

fide" seniority system when implemented by

an employer, if the moving force behind

the racial motivated seniority system was

a union, and the employer merely agreed to

establish and enforce that discriminatory

system at the behest of the union. The

Eleventh Circuit conceded that "no one can

seriously question that I AM" insisted for

racial reasons on dividing both the

46

Maintenance and Die and Tool Departments

into two parallel single race departments,

and on the adoption of seniority rules

that would effectively preclude blacks

from transferring into the better paying

all-white positions represented by the

I AM. (App. 173a) . But the Court below

insisted that those very seniority rules,

when implemented by Pullman-Standard, were

"bona fide" because there was no

"independent evidence of Pullman7s intent

with respect to the seniority system."

App. 174a.21 (emphasis added) The

Eleventh Circuit expressly held that the

company did not lose its ability to invoke

the section 703(h) defense merely because

it had signed the collective bargaining

agreements which contained the provisions

designed by the I AM to discriminate

against blacks.

21 See also App. 172a.

47

The Eleventh Circuit decision in this

case is squarely in conflict with

decisions in the Fourth and Ninth

Circuits. In Sears v. Atchison, T & S. F.

Rv. Co.. 645 F. 2d 1365 (9th Cir. 1981),

the Ninth Circuit held that a union faced

liability under Title VII if it was party

to a collective bargaining agreement that

established a non-bona fide seniority

system, regardless of whether the union

might have accepted that portion of the

agreement for entirely benign reasons.

A union's role as a party to a collective bargaining agreement may be sufficient to impose back pay liability on the union.22

It is unnecessary for us to find

that the union entered the

agreement with the intention of

discriminating. The action of agreeing to the seniority system was n o n a c c i d e n t a 1 and

deliberate.23

22 645 F.2d at 1375.

23 645 F.2d at 1375 n.9.

48

[T]he union's role in freezing

the status quo of a prior

discriminatory seniority system, not immunized under section

703(h), renders it liable to

those upon whom the seniority

system had an adverse impact.24

This is, of course, precisely the argument

rejected by the Eleventh Circuit in the

instant case.

Similarly, the Fourth Circuit in

Robinson v. Lorillard. 444 F.2d 791 (4th

Cir.), cert dismissed. 404 U.S. 1006

(1971), rejected an employer's argument

that an unlawful

seniority system was only

adopted under union pressure,

and that, "A company would probably never establish a

seniority system of its own

accord ..." ... Lorillard's

apparent point is that it was

forced either to accept the

system or endure a strike....

The rights assured by Title VII

are not rights that can be bargained away.... Despite the

fact that a strike over a

contract provision may impose

e c o n o m i c costs, if a

24 645 F.2d at 1375.

49

d i s c r i m i n a t o r y contract

provision is acceded to the

bargainee as well as the bargainor will be held liable.

444 F.2d at 799.

The importance of this issue is

illustrated by the briefs in Lorance v A.

T. & T. Technologies. The company in that

case acknowledged that union discussions

of the disputed seniority provision were

permeated with statements hostile to

respecting the seniority rights of female

workers. The company insisted, however,

that there was no evidence that its own

officials, in agreeing to the provision at

issue, had acted from any such motives:

[I]t [is not] alleged that AT&T

knew what had been said at the

union meetings much less that

anyone from AT&T who negotiated

the Tester Concept then acted

other than for legitimate

business reasons.

Respondent's Brief, No. 87-1428, p. 7.

The decision of the Eleventh Circuit

cannot be reconciled with the language of

50

section 703(h), or with the terms of

Teamsters and its progeny. The Eleventh

Circuit decision analyzes separately the

motives of each party to a collective

bargaining agreement, holding in this case

that Pullman-Standard acted with bona

fides in agreeing to the provisions at

issue, while conceding that the I AM did

not. But section 703(h), like Teamsters

and its progeny, concerns whether a

seniority system is bona fide; it flies in

the face of the statutory language to

hold, as has the Eleventh Circuit in this

case, that the self same seniority system

is bona fide when administered by Pullman-

Standard, but not bona fide if implemented

by the IAM.

The distinction created by the

Eleventh Circuit would at times virtually

nullify enforcement of Title VII. On the

Eleventh Circuit's view, because section

51

703(h) protects employer implementation of

a union sponsored racially motivated

seniority system, an employee injured by

that discriminatory system could not

obtain any remedy whatever against the

employer. It is typically the case that

seniority provisions are largely the

creation of a union but are in practice

implemented by the company officials who

make promotion and layoff decisions. In

such circumstances it would be impossible

on the Eleventh Circuit's view to enjoin

the implementation of a racially motivated

seniority system, because the

administration by an employer of such a

race based system would be lawful under

Title VII.25

25 The Eleventh Circuit thought that this unusual result was required by

footnote 23 in this Court's opinion in

Pullman-Standard v. Swint. 456 U.S. 273,

292 n.23 (1982), which states in part:

" I A M ' s d i s c r i m i n a t o r y

52

motivation, if it existed,

cannot be imputed to USW. It is relevant only to the extent

that it may shed some light on the purpose of USW or the

company in creating and maintaining the separate

seniority system at issue in

this case."

(Emphasis added). This footnote was

addressed to the argument, apparently

accepted by the Fifth Circuit in its 1981

opinion, that the discriminatory I AM

motives underlying the lAM-Pullman-

Standard seniority system supported a

finding that the separate USW-Pullman-

Standard seniority system was also racially motivated. See 624 F.2d at 533.

This case also presents a dispute,

however, about the legality of the IAM-

Pullman-Standard rules which effectively

precluded transfers into IAM represented

jobs; this Court's 1982 decision does not,

of course, suggest that the IAM's motives are irrelevant to the bona fides of the

IAM-Pullman-Standard system.

53

CERTIORARI SHOULD BE GRANTED TO

RESOLVE A CONFLICT AMONG THE

CIRCUITS AS TO WHICH PARTY BEARS THE BURDEN OF PROOF REGARDING

WHETHER A DISPUTED SENIORITY

SYSTEM IS BONA FIDE

In many instances in which the bona

tides of a seniority system is in dispute,

III.

it is of critical importance to the

resolution of the case whether the

plaintiff or the defendant bears the

burden of proof. This Court has not

previously been asked to resolve this

question. There is lancruacre in Teamsters

and its progeny which appears to support

both possible interpretations of section

703(h), and the circuit courts have, as a

consequence, disagreed as to which party

bears the burden of proof.

The Sixth Circuit construes Teamsters

to place the burden of proof under section

7 03 (h) on the defendant. EEOC v. Ball

Corn.■ 661 F.2d 531 (6th Cir. 1981).

54

Ball Corporation asserts that its promotion and transfer policies qualify as a bona fide seniority system under Section

703(h) of Title V I I . . . . In

Teamsters ... the Supreme Court

held that Section 703(h) exempts

from Title V I I liability those

"neutral, legitimate system[s]" that do not have [their] genesis

in racial ... discrimination and

that ... "[were] negotiated and

... maintained free from any illegal purpose." 431 U.S. at 353-56 .... Thus, if anemployer shows that differences

in pay or employment conditions

result from the operation of a

bona fide seniority system, the

plaintiff's prima facie case is effectively rebutted.

Ball Corporation made no such showing below.

661 F.2d at 538-39. (Emphasis added). In

Bernard v. Gulf Oil Corp. . 841 F.2d 547

(5th Cir. 1988), the Fifth Circuit

described the issue raised by a seniority

system that perpetuated past discrimina

tion to be whether "the defendants failed

to prove that the seniority system was

bona fide under section 703(h)." 841 F.2d

at 551, 554. The Third, Fourth and

55

Seventh Circuits hold that the burden of

proof is on the defendant to establish

bona fides under the section 4(f)(2) of

the ADEA which, like section 703(h),

creates an exemption for bona fide

seniority and other systems.26

The Eleventh Circuit adheres to an

unusual hybrid rule contrary to the

standard in the other circuits. On the

one hand, the Eleventh Circuit recognizes

that section 703(h) creates an affirmative

defense. Jackson v. Seaboard Coast Line

R. Co.. 678 F.2d 992 (11th Cir. 1982).27

26 EEOC v. Westinahouse Elec, Coro.,

725 F. 2d 211, 223 (3d Cir. 1983); Smart

v. Porter Paint Co. . 630 F.2d 490, 493

(7th Cir. 1980) ; Crosland v. Charlotte

Eye, Ear and Throat Hoso.. 686 F.2d 208,

213 (4th Cir. 1982) .

27 "The [union] ... claims as error

that the district court did not find and the appellees failed to

prove that the alleged

discrimination did not result from the normal operation of a bona f ide seniority system

protected from attack under

56

On the other hand, the Eleventh Circuit

also holds that once a defendant has

merely pled the existence of a section

703(h) affirmative defense, the burden of

section 703(h).... The district

court held that the [union] waived its right to advance this claim by failing to plead it as an affirmative defense under Ref. R. Civ. P. 8(c). We agree....

[S] everal courts have held that the

section 703(h) exemption is in the

nature of an affirmative defense....[T] he courts have generally treated

statutory exemptions from remedial

statutes as affirmative defenses....

[Rjequiring the section 703(h) exemption to be pled as an

affirmative defense promotes fairness. It places the burden of pleading on the party who will be

benefitted by the departure from the

normal operation of Title VII, and

permits plaintiffs to proceed without

the undue burden of having to

anticipate a section 703(h) defense by stating in their complaint that

the challenged discrimination is not the result of a bona fide seniority

system.... [W]e hold that the

section 703(h) exemption for bona fide seniority systems constitutes an affirmative defense."

688 F.2d at 1012-13.

57

proof is on the plaintiff to disprove that

defense: "the burden of persuading the

district court that a system is the

product of an employer's discriminatory

intent lies with the plaintiff." (App.

172a) .

The Fourth Circuit has expressly

recognized that there is a conflict among

the lower courts as to which party bears

the burden of proof under section 703(h),

but that circuit has refused to decide

which rule is correct. Gant 1 in v. West

Virginia Pulp and Paper Co.. 734 F.2d 980,

992-93 (4th Cir. 1984). Somewhat

paradoxically, the Fourth Circuit panel in

Gantlin criticized the district judge in

that case for having himself failed to

address the burden of proof issue under

section 703(h), which it emphasized was

both a "critical" and "open" question.

734 F.2d at 993 n.20.

58

The decisions of this Court contain

language which provides support for both

sides of this intercircuit conflict. On

the one hand, as the Sixth Circuit

emphasized, Teamsters repeatedly described

section 703(h) as an exemption which

"immunized" seniority practices that would

otherwise have been illegal under Title

VII. 431 U.S. at 345, 349, 350, 353.

Ordinarily "the burden of proof is on ...

one [who] claims the benefits of an

exception to the prohibition of a

statute". United States v. First City

Nat. Bank. 386 U.S. 361, 366 (1967). In

Nashville Gas Co. v. Sattv. 434 U.S. 136

(1977), the Court held that the burden of

proof was on the defendant to demonstrate

the existence of a business justification

for a seniority system which had the

59

effect of discriminating against women.28

This Court has expressly held that the

seniority system exceptions to the Age

Discrimination in Employment Act and the

Equal Pay Act, both extremely similar to

section 703(h), are affirmative defenses.

County of Washington v. Gunther. 452 U.S.

161 (1981); Trans World Airlines. Inc, v.

Thurston. 469 U.S. Ill (1985). The normal

rule is that a defendant bears the burden

of proof with regard to factual issues

x-aised by an affirmative defense. 2A

Moored Federal Practice, p. 8-177, 8-

179. On the other hand, as the Eleventh

Circuit noted in the instant case, some

28 434 U.S. at 143:

"[W]e agree with the District Court in this case that since there was no proof of any business necessity adduced with respect to the policies in question, that court was

entitled to 'assume no

justification exists.'"

60

passages in the Teamsters progeny do

suggest that the plaintiff bears the

burden of proof on this issue. Trans.

World Airlines. Inc., v. Hardison. 432

U.S. 63, 82 n. 13 (1977).

This very dispute is evident in the

briefs in Lorance v. A.T & T.

Technologies . No. 87-1428 . The

respondents there assume that a challenge

to a seniority system requires that the

plaintiff prove that the system was or is

racially motivated. (Respondents' Brief,

No. 87-1428, passim). The Solicitor

General, on the other hand, evidently

construes Title VII in the opposite way,

describing the plaintiffs' allegations in

Lorance that the seniority system was

racially motivated as "simply meeting a

possible defense to their discrimination

claim." (Brief for the United States, No.

87-1428, p. 20 n. 26) (Emphasis added.)

61

The conflict among the lower courts,

and the uncertainty generated by this

Court's opinions, exist in part because

disputes about the racial purpose of a

seniority system in fact arise under Title

VII in three quite distinct circumstances,

(a) In some cases, as in Teamsters. the

plaintiff complains that the seniority

system has the effect of perpetuating past

discrimination, and the defendant asserts

section 703(h) as an affirmative defense.

That is the posture of the instant case,29

and is the situation in which the Fifth

and Sixth Circuits, but not the Eleventh,

place the burden of proof on the

defendant? (b) In some cases, as appears

to be the situation in Lorance, the

29 The respondents in Lorance insisted that the disputed seniority rule in that case neither perpetuated any past

discrimination nor had any net adverse impact on women. Brief for Respondents, No. 87-1428, p. 3 n. 2, p. 16 n. 18.

62

gravamen of the plaintiffs complaint is

that a particular seniority practice,

whatever its net effect, was adopted or

maintained for an illegal purpose. In

such a case the plaintiff may well bear

the burden of proof of racial purpose, not

because of section 703(h), but because the

case presents a garden variety claim that

a particular practice (which happens to be

a seniority practice) is racially

motivated; (c) In some instances, whether

effect cases like Teamsters or an intent

case like Lorance. the plaintiff may prove

that the disputed seniority system or

practice was in the past created or

maintained with a discriminatory purpose;

in that situation the burden of proof

would ordinarily be on the defendant to

demonstrate that discriminatory purpose,

and its ongoing effects, had been

eliminated. See Keyes v. School District

63

No. 1 ■ 413 U.S. 189 (1973). That

circumstance is also presented by the

instant case.30 The very complexity of

these overlapping questions is likely,

absent clarification by this Court, to

spawn even greater conflict and confusion.

CONCLUSION

For the above reasons, a writ of

certiorari should be granted to review the

judgment and opinion of the Eleventh

Circuit. In the alternative, it may be

appropriate to defer action on this

petition pending the decision by this

Court in Lorance v. A. T & T.

Technologies.

30 The lower courts agreed that , at least until 1965, there was in practice a

race-based seniority system for intra-

departmental promotions. See pp. 11-12,

supra. When, if at all, that racial

seniority practice ended remains a matter of dispute, and was not definitively

resolved by the courts below. See pp.

12-15, supra.

64

Respectfully submitted,

ELAINE R. JONES

NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc.

Suite 301

1275 K. Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 682-1300

JAMES U. BLACKSHER 5th Floor Title Building 300 21st Street, North

Birmingham, Alabama 35203 (205) 322-1100

OSCAR W. ADAMS, III

Brown Marx Building Suite 729

2000 First Ave., North Birmingham, Alabama (205) 324-4445

65

JULIUS L. CHAMBERS

ERIC SCHNAPPER*NAACP Legal Defense &

Educational Fund, Inc.

16th Floor 99 Hudson Street New York, New York 10013

(212) 219-1900

Counsel for Petitioners

*Counsel of Record

APPENDIX

Louis SWINT and Willie James Johnson, on behalf of themselves and others

similarly situated, Plaintiffs-

Appellants,

v.

PULLMAN-STANDARD, Bessemer, Alabama, United Steelworkers of America, Local

1466, United Steelworkers of America AFL-CIO and International Association

of Machinists and Aerospace Workers, AFL-CIO, Defendants-Appellees,

No. 78-2449.

United States Court of Appeals,Fifth Circuit.*

Dec. 6, 1982.

As Corrected April 4, 1983.

Appeal from the United States

District Court for the Northern District

of Alabama.

ON REMAND FROM THE SUPREME COURT

COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

Before RONEY and HATCHETT, Circuit

Judges, and WISDOM, Senior Circuit Judge.

PER CURIAM:

Former Fifth section 9(1) of Public

October 14, 1980.

Circuit

Law 9 6

Case,

452-

la

This employment discrimination

action's first journey to this court

resulted in a remand to the district

court for further proceedings with respect

to Pullman-Standard's seniority system and

its selection of supervisory personnel.

Swint v. Pullman-Standard. 539 F.2d 77

(5th Cir. 1976) . Subsequently, the

district court held that the seniority

system did not discriminate against blacks

and was therefore bona fide under 42

U.S.C. § 2000e-2(h), that Pullman-

Standard did not follow a discriminatory

practice or policy in job assignments

after the effective date of the Civil

Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C.A. § 2000e-

1(a), and that Pullman-Standard had

rebutted the plaintiff's prima facie case

of discrimination in the selection of

supervisory personnel. We reversed and

held that: (1) although the statistics

2a

disclosed that Pullman-Standard had made

significant advancements in eliminating

previous all-black and all-white

departments subsequent to 1966, the total

employment picture revealed that racially

discriminatory assignments were made after

the effective date of Title VII; (2)

Pullman-Standard's department seniority

system was not "bona fide" within the

meaning of section 703(h) of Title VII, 42

U.S.C.A. 2000e-2(h); and (3) the

plaintiffs' prima facie showing of racial

discrimination in the selection of

supervisory personnel had not been

rebutted. Swint v. Pullman-Standard, 624

F.2d 525 (5th Cir. 1980).

The United States Supreme Court

granted certiorari to review the seniority

system issue, reversed the judgment of

this court, and remanded the case to us

"for further proceedings consistent with

3a

this opinion." U.S. 102

S.Ct. 1781, 1792, 72 L.Ed.2d 66, 82

(1982). Accordingly, we VACATE our

judgment as to this issue and REMAND the

case to the district court for further

proceedings to determine what impact the

"locking-in" of blacks to the least

remunerative departments had on

discouraging transfer between seniority

units, and the significance of the

discriminatory motivation of IAM with

respect to the institution of USW's

seniority system, and any other

proceedings that may be deemed necessary

in view of our prior opinion and that of

the United States Supreme Court.

REMANDED.

4a

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT NORTHERN DISTRICT OF ALABAMA Southern Division

LOUIS SWINT, et al., )

)Plaintiffs, )

)-vs.- ) No. CV71-P-0955-S

PULLMAN-STANDARD, et al., )

)Defendants.

OPINION

(Pullman-Standard IX)

For decision are certain issues still

at "Phase I" after fifteen years of

litigation. The first trial was conducted

in 1974; additional evidentiary hearings

were held in 1977, 1978, and 1984.

Although a detailed recital of the prior

proceedings in the trial and appellate

courts is unnecessary, reference must be

made from time to time to these earlier

5a

opinions.1 Pullman-Standard ceased its

operation in Alabama more than five years

ago? however — absent settlement or

providential intervention -- this

litigation appears destined for yet

further hearings and decisions.

I. SCOPE OF INQUIRY

Before proceeding to questions of

liability, the court must define the scope

of this inquiry — that is, the proper

anterior (beginning) and posterior

(ending) cut-off dates of this liability

period and the appropriate class

definition. *

x Pullman-Standard I. 11 FEP Cases

943 (N.D. Ala. 1974? Pullman-Standard II. 539 F. 2d 77 (5th Cir. 1976)? Pullman-

Standard III. 15 FEP Cases 1638 (N.D. Ala. 1977) ? Pullman-Standard IV. 15 FEP Cases

144 (N.D. Ala. 1977)? Pullman-Standard V .

17 FEP Cases 730 (N.D. Ala. 1978) ?

Pullman-Standard VI. 624 F.2d 525 (5th Cir. 1980)? Pullman-Standard VII. 456 U.S. 273 (1982)? Pullman-Standard VIII. 692 F.2d 1031 (5th Cir. 1983).

6a

A. Anterior Cut-off Date.2

The question of the anterior cut-off

is intertwined with, and complicated by,

motions to intervene by four putative

class members and the existence of a Title

VII charge filed on March 27, 1967, by

Commissioner Shulman of the Equal

Employment Opportunity Commission.

Plaintiffs contend that this intervention

should be allowed, and that the anterior

date should be set by reference to the

EEOC charge filed on October 30, 1966, by

one of the proposed intervenors, Spurgeon

Seals. In the alternative, they argue

that Commissioner Shulman's charge should

be the date designator. Defendants

maintain that the anterior date should be

Typically, the anterior cut-off

for class membership and for the liability

period are the same. Case law referring

to the beginning date of membership in a class usually also refers to the beginning

of the liability period and is relevant to

the instant discussion.

7a

measured by reference to October 15, 1969,

the filing date of the charge of Louis

Swint, the named plaintiff and class

representative during the past 15 years.

The court agrees with the defendants.3

Some factual background is necessary

for an understanding of the attempted

intervention. On December 9, 1975, a

separate suit was filed in this district

by William Larkin, Spurgeon Seals, Edward

Lofton, and Jesse Terry against Pullman-

Standard for redress of alleged Title VII

violations. Pullman-Standard I was

already on appeal to the Fifth Circuit at

the time this new suit (Larkin ̂ was filed.

On January 20, 1976, Larkin was dismissed

J The Fifth Circuit has succinctly stated the law: "The opening date for