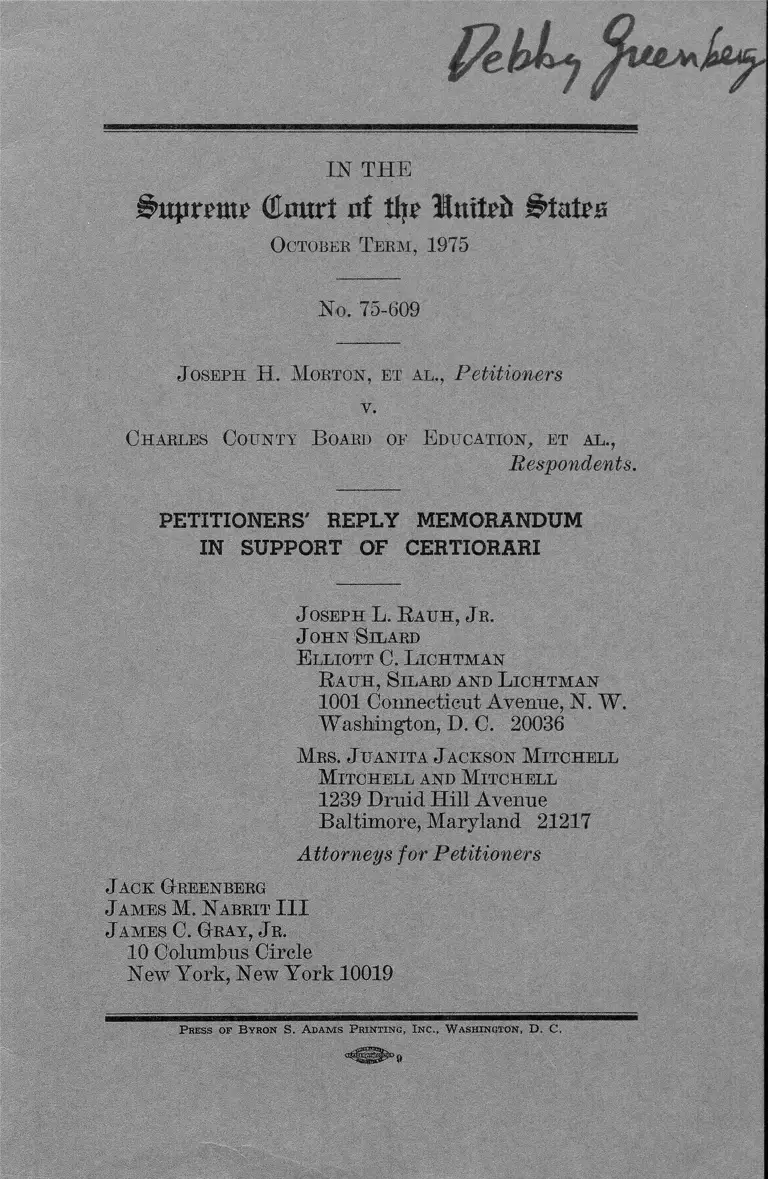

Morton v. Charles County Board of Education Petitioners' Reply Memorandum in Support of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1975

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Morton v. Charles County Board of Education Petitioners' Reply Memorandum in Support of Certiorari, 1975. 84dee3d2-be9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/6f3a1faf-3b75-47d9-bc28-5bb4b49f153a/morton-v-charles-county-board-of-education-petitioners-reply-memorandum-in-support-of-certiorari. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

IN THE

Supreme OXuttrt nf % ImtTfr States

O ctober T e r m , 1975

No. 75-609

J oseph H. M orton , et a l ., Petitioners

v,

C h arles C ou n ty B oard of E du cation , et a l .,

Respondents.

PETITIONERS' REPLY MEMORANDUM

IN SUPPORT OF CERTIORARI

J oseph L . R a u h , J r .

J o h n S h a r d

E llio tt C. L ic h t m a n

R a u h , S ilard an d L ic h t m a n

1001 Connecticut Avenue, N. W.

Washington, D. C. 20036

Mrs. J u a n it a J ackson M it c h e l l

M it c h e l l and M it c h e l l

1239 Druid Hill Avenue

Baltimore, Maryland 21217

Attorneys for Petitioners

J a c k G reenberg

J a m e s M. N abrit I I I

J a m e s C. G r a y , J r .

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

P ress of B yron S. A dam s P rinting, Inc., W ashington, D . C.

9

IN THE

OXmtrt of % Inttri* States

O otobeb T e r m , 1975

No. 75-609

J oseph H. M orton , et a l ., Petitioners

V.

C h arles C o u n ty B oard oe E du cation , et a l .,

Respondents.

PETITIONERS' REPLY MEMORANDUM

IN SUPPORT OF CERTIORARI

Respondents;’ patent effort to factualize the clear

legal issues presented by the Petition evidences their

own recognition of the unusual significance of those

legal issues. And it could not be otherwise, for it is in

contestable that the District Judge applied the wrong

legal standards to the facts before him.

All three legal issues raised by the Petition are clear

ly before the Court. Thus, the majority and dissenting

opinions both expose the issue whether the District

Court properly placed the burden on the plaintiffs

rather than requiring defendants to justify their prac

tices which indisputably sharply reduced the black

2

faculty component when student desegregation was

undertaken in 1967. The equally clear question of

law presented is whether a “ discriminatory effect” or

a “ racial animus” standard applies to those School

Board hiring and promotion practices which have

had a strongly adverse impact on the employment of

minority teachers and principals. And equally pre

sented is the question whether the District Court, could

totally shrug aside the State of Maryland’s own de

terminations and remedial orders addressed to the

Charles County school officials’ discriminatory hiring

and promotion practices. Thus, respondents’ attempt

to defuse and diffuse the Petition through a factual

justification o f their conduct cannot vitiate the three

central legal errors which tainted the District Court’s

resolution of this case.

Moreover, the School Board’s factual recitation to

this Court wholly fails in its attempt to undermine the

points on which we base our petition for review:

(i) In attempting to explain the adoption of an an

nual hiring ratio of four whites to one black in a school

system which had approximately equal racial repre

sentation before black teachers were first generally as

signed to teach white students, respondents repeatedly

cite inapposite and inconsequential facts. Thus, they

rely (Opp. pp. 7-8, 11) on a decrease in the proportion

o f black Charles County residents and a decrease in the

proportion of black students in the Charles County

School System during the 1960s which are totally ir

relevant to the hiring of teachers. Further they point

(id.) to the low percentages of Charles County black

residents who hold college degrees, which equally fail

to justify the School Board’s failure to hire blacks

when, as the record shows, the teacher hires come from

3

more than half the states in the nation (A. 1225-26,

1231, 1235-38. See Petition p. 15 n.8),

(ii) Concerning the School Board's discriminatory

recruitment policies, respondents’ reliance (Opp. p. 11)

on the eonclusory satisfaction of the majority below

with the Board of Education’s recruitment efforts can

not gainsay the undisputed fact that the School

Board’s recruiting was at mostly white colleges with

mostly white recruiters (see Petition, pp. 6-7, 10).

(iii) Concerning the undisputed evidence that the

Charles County School System hired numerous whites

with the lowest State qualifications while hiring vir

tually no blacks with such limited qualifications, it is

no answer for respondents to rely (Opp. p. 11) on the

District Court’s statement that such persons were hired

from the local area just before the school year opened.

The uncontested record shows that 60% of all new hires

were usually hired that late in the school year (A. 873-

908), and there is no evidence that these hires were

drawn only from the local area. The only relevant

evidence is the the School Board in general hires ap

plicants from the majority of states in the nation.1

All apart from respondents’ attempt to cloud the

salient facts in this case, it is clear that petitioners were

entitled to have the District Court review those facts

under the proper legal standards. There is no possible

dispute that the District Court refused to shift the bur

den of justification to the School Board for its hiring

and promotion practices which sharply reduced the

1 Respondents ’ reliance on their teacher assignments after this

action was commenced in the one year just prior to the 1973 trial

(Opp. pp. 11-12) hardly undercuts the undisputed record that dur

ing the preceding six years the school system assigned teachers on a

racially identifiable basis in the majority of its schools.

4

black faculty component immediately after the desegre

gation of the student bodies.2 There is thus squarely

presented the issue of whether Keyes-Chambers re

quires transfer of the burden where the School Board

has utilized the more “ sophisticated” means of refus

ing to hire blacks instead of engaging in outright dis

charges.

Similarly, it is clear that the lower courts disre

garded Maryland’s own findings that respondents en

gaged in discriminatory employment practices and the

State’s orders to correct those practices.3 The im

portant issue whether the lower courts should have

honored and given effect to the State’s own action is

thus clearly presented.

Also squarely raised iS the lower courts’ use

of the motivation standard instead of the Wright

“ effect” test. Here the Charles County Board repeats

(Opp. p. 14) its specious argument to the Court of

Appeals that because the District Court found no

“ pattern of discrimination” the District Court applied

an “ effect” standard. But the majority of the Court

of Appeals failed to accept respondents’ assertion and

2 Respondents quibble (Opp. p. 14) that there is no “ history of

segregation” here because the School Board had adopted a free

dom of choice plan for some years prior to 1967. But that pro

gram was totally ineffective, and the token transfers of a few

blacks to white schools and a few whites to black schools in no

way refute the undisputed fact that the student bodies and

faculties remained essentially segregated until 1966 and 1967.

3 While Respondents attempt (Opp. p. 8) to disparage the

findings of the State Board’s Committee because of the Commit

tee’s informal procedures —which Charles County itself had

suggested—-those findings were in fact the premise of the State

Board’s remedial orders.

5

do not at all suggest that the District Judge applied

the effect standard. Moreover, a careful reading of the

District Court’s opinion exposes its application of the

erroneous racial animus test (see Petition, pp. 23a,

24a, 27a, 29a, 34a, 36a, 40a-42a, 45a-47a, 49a). As dis

senting Judge Butzner states, the District Court’s

Opinion contains “ a basic error of law that flaws this

case: the fallacious premise that the evidence must

reveal purposeful discrimination in order for the com

plainants to prevail” (Petition, p. 12a).

In short, this case raises three vital legal issues

which require grant of the writ.

Respectfully submitted,

J oseph L. R a u h , Jr.

J o m S ilard

E llio tt C. L ic h t m a n

R a ih i , S ilard and L ic h t m a n

1001 Connecticut Avenue, 1ST. W.

Washington, D. C. 20036

M rs. J u a n it a J ack so n M it c h e l l

M it c h e l l and M it c h e l l

1239 Druid Hill Avenue

Baltimore, Maryland 21217

Attorneys for Petitioners

J a c k G reenberg

J AMES M. N A BRIT I I I

J a m e s C. G r a y , J r .

10 Columbus Circle

Hew York, New York 10019

13073-1 1-75