R.A.V., v. City of St. Paul, Minnesota Brief Amicus Curiae in Support of Respondent

Public Court Documents

August 23, 1991

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. R.A.V., v. City of St. Paul, Minnesota Brief Amicus Curiae in Support of Respondent, 1991. 95b074d6-c19a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/6f7af133-0f21-40b5-81eb-1f859d4ea2d7/rav-v-city-of-st-paul-minnesota-brief-amicus-curiae-in-support-of-respondent. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

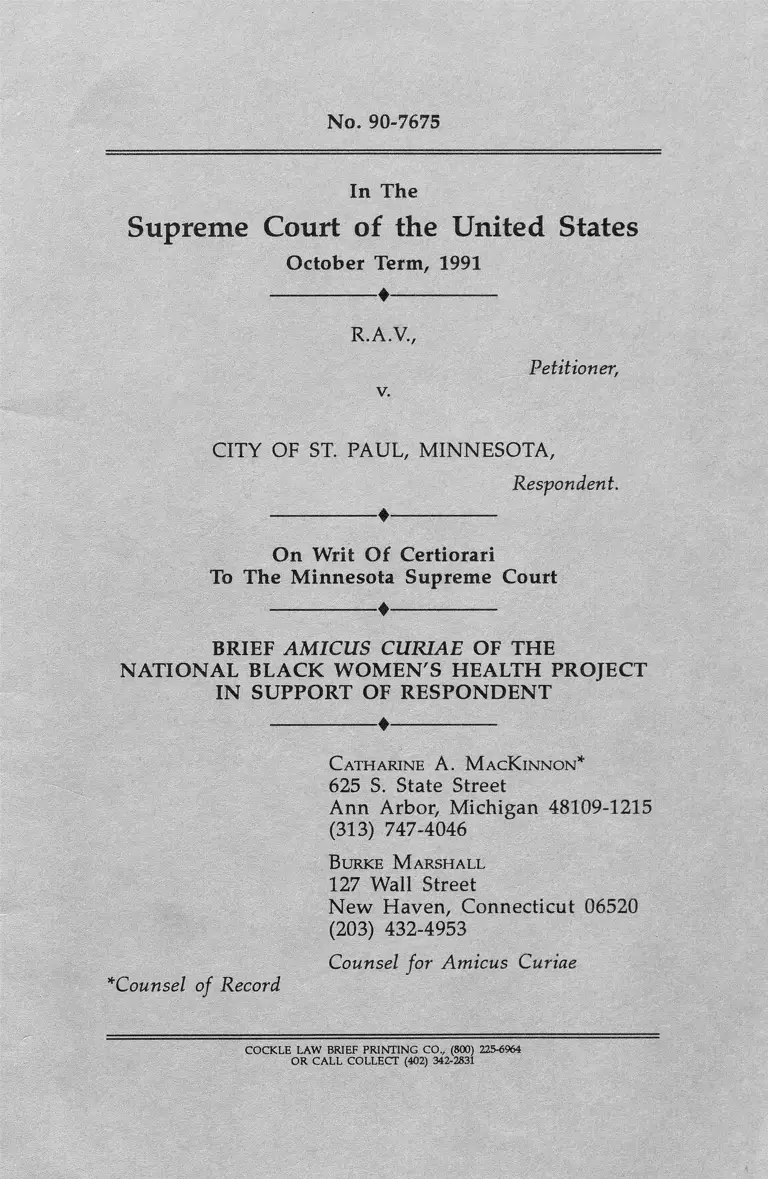

No. 90-7675

In The

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1991

--------------- ♦---------------

R.A.V.,

v.

Petitioner,

CITY OF ST. PAUL, MINNESOTA,

Respondent.

-----------------♦ -----------------

On Writ Of Certiorari

To The Minnesota Supreme Court

----------------- >-----------------

BRIEF AMICUS CURIAE OF THE

NATIONAL BLACK WOMEN S HEALTH PROJECT

IN SUPPORT OF RESPONDENT

----------------- * -----------------

C atharine A. M acK innon*

625 S. State Street

Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109-1215

(313) 747-4046

B urke M arshall

127 Wall Street

New Haven, Connecticut 06520

(203) 432-4953

Counsel for Amicus Curiae

*Counsel of Record

COCKLE LAW BRIEF PRINTING CO., (800) 225-6964

OR CALL COLLECT (402) 342-2831

1

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES......................... ii

CONSENT OF PARTIES................................................... 1

INTEREST OF AM ICUS................................................... 1

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT........................................... 3

ARGUMENT....................................................................... 5

I. THE CHALLENGED ORDINANCE PRO

MOTES THE COMPELLING GOVERN

ME NT AL I N T E R E S T IN EQUAL I T Y,

OUTWEIGHING FIRST AMENDMENT CON

CERNS .................................... 5

A. The ordinance prohibits discriminatory

practices which violate and undermine

the equality rights of target groups........ 5

B. The practices of inequality prohibited by

§ 292.02 are not protected by the First

Amendment....................................................... 13

II. AS APPLIED TO DISCRIMINATORY EXPRES

SIVE CONDUCT, § 292.02 IS NOT SUBSTAN

TIALLY OVERBROAD........................................... 24

CONCLUSION............................................................ 27

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

C ases

Adderley v. State of Florida, 385 U.S. 39 (1966) . . . . . 26

Alexander v. Yale Univ., 459 F. Supp. 1 (D. Conn.

1977) aff'd., 631 F.2d 178 (2d Cir. 1980 )................... 11

Barnes v. Glen Theatre, Inc., I l l S.Ct. 2456 (1991) .17, 18

Beauharnais v. Illinois, 343 U.S. 250 (1952).......... 24

Blow v. North Carolina, 379 U.S. 684 ( 1965) . . . . . . . . . 11

Bob Jones Univ. v. U.S., 461 U.S. 574 (1983)................ 25

Bohen v. East Chicago, 799 F.2d 1180 (7th Cir.

1986)............................................... ...................................... 10

Broadrick v. Oklahoma, 413 U.S. 601 (1973) . . . 4, 25, 26

Brockett v. Spokane Arcades, Inc., 472 U.S. 491

(1985).................. ................................................................. 25

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954) .16, 22

Chaplinsky v. New Hampshire, 315 U.S. 568 (1942) . .3, 26

City Council of Los Angeles v. Taxpayers for Vin

cent, 466 U.S. 789 (1984). .... ............................................... 22

Collin v. Smith, 578 F.2d 1197 (7th Cir. 1978) cert.

denied, 439 U.S. 916 (1978)............................... 14, 19, 24

Cohen v. California, 403 U.S. 15 (1971)............ 14

Community for Creative Non-Violence v. Watt,

468 U.S. 288 (1984)............................................................. 20

Continental Can v. State, 297 N.W,2d 241 (Minn.,

1980)...................................................................................... 10

Davis v. Passman, 422 U.S. 228 (1971).......................... 11

ii

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Page

I l l

Ford v. Hollowell, 385 F. Supp. 1392 (N.D. Miss.

1 9 7 4 )............................................. ................................. .6, 7

Friend v. Leidinger, 446 F. Supp. 361 (E.D. Va.

1977) aff'd, 588 F.2d 61 (4th Cir. 1978)...................... 10

Gooding v. Wilson, 405 U.S. 518, 530 (1972)..........13, 26

Heart of Atlanta Motel, Inc. v. U.S., 379 U.S. 241

(1964) .......................... .9

Henson v. City of Dundee, 682 F.2d 897 (11th Cir.

1 9 8 2 )........... 10

Hicks v. Gates Rubber, 928 F.2d 966 (10th Cir.

1991).................................................................... 10

Hishon v. King & Spalding, 467 U.S. 69 (1983).......... 16

Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer Co., 392 U.S. 409 (1968) . . . . 11

Korematsu v. U.S., 323 U.S. 214 (1944).......................... 3

Lac du Flambeau Indians v. Stop Treaty Abuse-

Wis., 759 F. Supp. 1339 (W.D. Wis. 1991). .............. 17

Lloyd Corp. v. Tanner, 407 U.S. 551 (1972).................. 26

Loving v. Virginia, 388 U.S. 1 (1967)............................. 23

Marshall v. Bramer, 110 F.R.D. 232 (W.D. Ky. 1985) . .6, 12

Matter of Welfare of R.A.V., 464 N.W. 2d 507

(Minn. 1991)...............................................................3, 5, 25

McMullen v. Carson, 754 F.2d 936 (11th Cir. 1985)........6

Meritor Savings Bank v. Vinson, 477 U.S. 57 (1986) . . . . 10

Morgan v. Hertz Corp., 542 F. Supp. 123 (W.D.

Tenn., 1981) .................................................................

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES - Continued

Page

11

I V

New York v. Ferber, 458 U.S. 747 (1982)

............................................................. ........... 4, 14, 16, 25, 26

Norwood v. Harrison, 413 U.S. 455 (1973).................... 20

Palmer v. Thompson, 403 U.S. 217 (1971)..................... 11

Pierson v. Ray, 386 U.S. 547 (1967)................................. 11

Pittsburgh Press Co. v. Pittsburgh Comm'n. on

Human Relations, 413 U.S. 376 (1973)............ 4, 14, 16

Price Waterhouse v. Hopkins, 490 U.S. 228 (1989) . . . . 11

R. v. Keegstra, [1991] 2 W.W.R. 1 ................................... 24

Rabidue v. Osceola Refining Co., 805 F.2d 611 (6th

Cir. 1986) .................................. ................................... 10

Richmond v. J.A. Croson, 488 U.S. 469 (1989)..............3

Roberts v. U.S. Jaycees, 468 U.S. 609 (1983)

......................................................................... 3, 16, 20, 23, 24

Robinson v. Jacksonville Shipyards, 760 F. Supp.

1486 (M.D. Fla. 1991).................................................10, 11

Rogers v. EEOC, 454 F.2d 234 (5th Cir. 1971), cert.

denied, 406 U.S. 957 (1972).............................................. 10

State v. Miller, 398 S.E.2d 547 (1990) .............................. 18

Stevens v. Tillman, 855 F.2d 394 (7th Cir. 1988)........6, 8

Street v. New York, 394 U.S. 576 (1969)........................ 14

Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U.S. (10 Otto) 303

(1880)..................................... ........................ .................... H

Taylor v. Jones, 653 F.2d 1196 (8th Cir. 1981)........... 9

Texas v. Johnson, 491 U.S. 397 (1989)................ 18, 19, 20

U.S. v. Beaty, 288 F.2d 653 (6th Cir. 1961)..................... 9

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES - Continued

Page

V

U.S. v. Bruce, 353 F.2d 474 (5th Cir. 1965)..................... 9

U.S. v. Eichman, 110 S.Ct. 2404 ( 1 9 9 0 ) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 19

U.S. v. Gresser, 935 F.2d 96 (6th Cir. 1991)....................8

U.S. v. Lee, 935 F.2d 952 (8th Cir. 1991). 7, 8, 11, 14, 24

U.S. v. Long, 935 F.2d 1207 (1991)............................ 8

U.S. v. O'Brien, 391 U.S. 367 (1968) .................... 4, 14, 18

U.S. v. Original Knights of the Ku Klux Klan, 250

F. Supp. 330 (E.D. La. 1965).......................................... 6

U.S. v. Orozco-Santilian, 903 F.2d 1262 (9th Cir.

1990)....................................................................................... 14

U.S. v. Salyer, 893 F.2d 113 (6th Cir. 1989 ).......... 6, 7, 8

U.S. v. Worthy, 915 F.2d 1514 (11th Cir. 1990).........6, 8

Vance v. Southern Bell, 863 F.2d 1503 (11th Cir.

1 9 8 9 )................................................................ 9

Vaughn v. Pool Offshore Co., 683 F.2d 922 (5th Cir.

1982)...........................................................................................9

Vietnamese Fishermen's Ass'n. v. Knights of the

Ku Klux Klan, 543 F. Supp. 198 (1982)................. ... 17

Ward v. Rock Against Racism, 491 U.S. 781 (1989) . . . . 22

Watts v. United States, 394 U.S. 705 (1969) . ................ 13

Watson v. Memphis, 373 U.S. 526 (1963).......................... 11

Weiss v. U.S., 595 F. Supp. 1052 (E.D. Va. 1984).............. 10

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES - Continued

Page

VI

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES - Continued

Page

Statutory and O fficial A uthorities

Increasing Violence Against Minorities: Hearing

Before the Subcomm. on Crime of the House

Comm, on the Judiciary, 96th Cong., 2d Sess.

(1980)....................................................... ................... . 12

St. Paul Minn.Leg.Code section 292.02 (1990). . . . passim

Title 18 U.S.C. § 844(h)(1)........................................................ 8

Title 42 U.S.C. § 241.................................................................. 8

Title 42 U.S.C. § 1971(b)........... 8

Title 42 U.S.C. § 1985(3).....................8, 12

Title 42 U.S.C. § 2000b................... ......................................9

Title 42 U.S.C. § 3631(a).........................................................9

Title 42 U.S.C. § 3617 (1991) ................................................9

S cholarly A uthorities

Alexander, The Ku Klux Klan in the Southwest

(1965) ............................. 5

Baker, Scope of the First Amendment Freedom of

Speech, 25 U.C.L.A. L. Rev. 964 (1978)..................... 21

Bell, And We Are Not Saved: The Elusive Quest

for Racial Justice (1987).............................. ............... .. 23

Bollinger, The Tolerant Society (1986)............................ 21

Emerson, The System of Freedom of Expression

(1970).................................................................................... 21

Goldberg, Hooded Empire (1981)............... 5

Katz, The Invisible Empire (1986)....................................... 6

vii

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES - Continued

Page

Lawrence, If He Hollers Let Him Go: Regulating

Racist Speech on Campus, 1990 Duke Law Jour

nal 9 0 1 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 16

Major, Including Black Women, Midwest Acad

emy Citizen Action 1991 Conference, Rebuild

ing America (July 26-28, 1991) ........................... 2

Matsuda, Public Response to Racist Speech: Con

sidering the Victim's Story, 87 Mich. L. Rev.

2320 (1989). .................................... 12

Meiklejohn, Free Speech and its Relation to Self-

Government (1948) .................................. 21

National Black Women's Health Project, Annual

Report (1989)...........................................................................1

Padgett, Racially-Motivated Violence and Intim

idation: Inadequate State Enforcement and Fed

eral Civil Rights Remedies, 75 J. Crim. L. 103

(1984)..................... 6

Wade, The Fiery Cross (1987) ................................. .5, 6

CONSENT OF PARTIES

Letters of petitioner and respondent consenting to

the filing of this brief are being filed separately with it.

-----------------♦ -----------------

INTEREST OF AMICUS

The National Black W omen's Health Project

(NBWHP) is a national grassroots self-help and health

advocacy organization that is committed to improving

the overall health status of Black women. The core pro

gram is based on the concept and practice of self-help

and inclusion of all African American women, with a

special focus on women living on low incomes. Health is

not merely the absence of illness, but the active promo

tion of emotional, mental and physical wellness of pre

sent and future generations. Fundamental to this goal is

the eradication of racism, sexism, and poverty in society,

and with it the dramatically disproportionate health risks

and lower life expectancy to which Black families and

communities are subjected. National Black Women's

Health Project, Annual Report 1, 2, 16 (1989).

The NBWHP began in 1981 as a pilot program of the

National Women's Health Network, was incorporated as

a non-profit organization in 1984, and has become inter

nationally recognized as an advocacy organization by and

for Black women. Since its inception, it has grown to

more than 150 chapters in 26 states, with over 2,000

members participating, including members in St. Paul. In

1990, its National Public Policy and Education Office in

Washington, D.C. was established to provide a national

1

2

forum to ensure that the information, data, and perspec

tives of the NBWHP will have an impact on policy devel

opment affecting the health and well-being of African

American women.

NBWHP has observed that thousands of African

American women experience some form of continuing

social and psychological stress due to the combined

effects of inequality based on race, sex, and class. This

stress is directly related, both as cause and effect, to the

staggering and disproportionate degree of illness experi

enced by African American women. For the estimated 14

million African American women living in the United

States, life expectancy is shorter and maternal and infant

mortality rates are higher than those of white women.

This disparity is manifested not only in those areas con

sidered traditional health concerns of women, such as

obstetrics and gynecology, but in a wide array of chronic

conditions such as lupus, diabetes, hypertension, cardio

vascular disease, and certain cancers, from which African

American women are more likely to die than are their

white counterparts. Major, Including Black Women,

speech at Midwest Academy Citizen Action 1991 Confer

ence, Rebuilding America (July 26-28, 1991) 3-5 (present

ing data). The life expectancy in the African American

community lags three decades behind that of whites. Id.

at 3. As workers and heads of households, childbearers

and nurturers, African American women and other

women of color have borne the brunt of these inequal

ities. Illness and disease are thus sensitive indicators of

social inequality as well as social harms to be rectified.

3

Racist practices such as crossburnings and other

exemplary acts of terrorist bigotry dramatically affect

both the material and psychological context within which

African American women and their communities exist.

Such acts cause tremendous mental and emotional dam

age, create long-lasting dread and well-founded appre

hension for security of the person, and demand a

response as a means of attempting to reestablish self-

respect and security and ensuring survival. Living in a

state of seige is not conducive to health because it limits

access to that equality of rights without discrimination

which is essential to human flourishing.

-----------------♦ -----------------

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

The Minnesota Supreme Court upheld St. Paul Minn.

Leg. Code section 292.02 (1990) ("§ 292.02") by authori

tatively construing it as limited to "fighting words"

under Chaplinsky v. New Hampshire, 315 U.S. 568 (1942),

thus applying only to expressive conduct which falls

outside First Amendment protection. Matter of Welfare of

R.A.V., 464 N.W. 2d 507 (Minn. 1991). While accepting

this analysis, the National Black Women's Health Project

respectfully submits that the ordinance promotes the gov

ernment's "compelling interest in eradicating discrimina

tion," Roberts v. U.S. Jaycees, 468 U.S. 609, 623 (1983) (sex

discrimination), Korematsu v. United States, 323 U.S. 214,

216 (1944) (racial discrimination constitutionally suspect),

Richmond v. J.A. Croson, 488 U.S. 469, 494 (1989) (same) in

a way which outweighs First Amendment interests.

4

Crossburning, of which defendant R.A.V. is accused,

should be recognized as a terrorist hate practice of intim

idation and harassment which, contrary to the purposes

of the Fourteenth Amendment, works to institutionalize

the civil inequality of protected groups. As applied to

petitioner and others who engage in related practices, the

statute in question does not violate the First Amendment

because social inequality, including through expressive

conduct, is a harm for which states are entitled leeway in

regulation. New York v. Ferber, 458 U.S. 747 (1982) (harm to

mental and physical health of children used in child

pornography justifies its regulation); Pittsburgh Press Co.

v. Pittsburgh Comm'n. on Human Relations, 413 U.S. 376

(1973) (interest in eradicating sex discrimination out

weighs First Amendment interest in sex-segregated

advertising); U.S. v. O'Brien, 391 U.S. 367, 376-377 (1968)

(communicative conduct may be regulated under specific

conditions). The goal of eradicating inequality is

advanced narrowly, leaving ample room for less coercive

and harassing means of expressing the same message.

Applied, as here, to discriminatory expressive action,

§ 292.02 significantly advances equality and damages

freedom of expression virtually not at all. The compelling

interest in eradicating discrimination justifies any impact

that application of the statute, as narrowed by the Minne

sota Supreme Court and justified herein, may have on the

expressive freedoms of perpetrators of symbolic acts of

bigotry. Because the legitimate reach of § 292.02 dwarfs

any arguably impermissible applications, Broadrick v.

Oklahoma, 413 U.S. 601 (1973), the ordinance is not uncon

stitutionally overbroad.

5

ARGUMENT

I. THE CHALLENGED ORDINANCE PROMOTES

THE COMPELLING GOVERNMENTAL INTEREST

IN EQUALITY, OUTWEIGHING FIRST AMEND

MENT CONCERNS.

A. The Ordinance Prohibits Discriminatory Prac

tices Which Violate And Undermine The Equal

ity Rights Of Target Groups.

On its face, § 292.02 prohibits, with qualifications, the

placing of "a symbol, object, appellation, characterization

or graffiti, including but not limited to, a burning cross or

Nazi swastika" on public or private property. The quali

fications include a scienter requirement ("knows or has

reasonable grounds to know"), injurious or dangerous

consequences ("arouses anger, alarm, or resentment in

others"), and a traditional prohibited basis on "race,

color, creed, religion, or gender." This case applies the

statute to an incident in which white youths allegedly

burned a cross on the lawn of the one African American

family in a St. Paul neighborhood. Matter of Welfare of

R.A.V., 464 N.W. 2d 507 (Minn. 1991).

The flaming cross is a well-recognized symbol of

racial and religious hatred and instrument of persecution

and intimidation, historically directed principally against

Blacks and Jews. By the 1920's, the Ku Klux Klan - a

white supremacist racial hate organization which is

secret, violent, authoritarian, xenophobic, and rabidly

prejudiced - made it the emblem of its presence and the

precursor of arson, firebombing, torture, and lynching.

See generally Wade, THE FIERY CROSS (1987); Goldberg,

HOODED EMPIRE (1981); Alexander, THE KU KLUX

6

KLAN IN THE SOUTHWEST (1965); Katz, THE INVISI

BLE EMPIRE (1986). One federal district court found that

. . . . to attain its end, the klan exploits the forces

of hate, prejudice, and ignorance. We find that

the klan relies on systematic economic coercion,

varieties of intimidation, and physical violence

in attempting to frustrate the national policy

e x pr es s ed in c ivi l r i ght s l eg i s l a t i on.

. . . [Kjlansmen pledge their first allegiance to

their Konstitution and give their first loyalty to

a cross in flames. U.S. v. Original Knights of the

Ku Klux Klan, 250 F. Supp. 330, 334, 335 (E.D. La.

1965).

Crossburning was also directed against Jews by the Nazis

in Germany in the 1930s. Wade, 185. Crossburning, cou

pled with violence, motivated by invidious animus, has

continued to the present day, escalating in recent years.

McMullen v. Carson, 754 F.2d 936, 938 (11th Cir. 1985);

Marshall v. Bramer, 110 F.R.D. 232, 235-237 (W.D. Ky. 1985)

(collecting cases); Padgett, Racially-Motivated Violence

and Intimidation: Inadequate State Enforcement and Fed

eral Civil Rights Remedies, 75 J. Crim. L. 103 (1984).

Courts have recognized that crossburning threatens vio

lence, Stevens v. Tillman, 855 F.2d 394 (7th Cir. 1988), and is a

"particularly invidious act when directed against a black

American," U.S. v. Salyer, 893 F.2d 113, 117 (6th Cir. 1989),

one which produces "fear, anxiety, and apprehension for

safety" among Black men, Ford v. Hollowell, 385 F. Supp. 1392,

1397 (N.D. Miss. 1974). The Eleventh Circuit, in a case

involving a conviction for crossburning, recognized that

crossburning sought to intimidate a Black family. U.S. v.

Worthy, 915 F.2d 1514, 1515 (11th Cir. 1990). The Eighth

Circuit recently concluded that a "cross burning was an

7

especially intrusive act which invaded the substantial

privacy interests of its victims in an essentially intoler

able manner." U.S. v. Lee, 935 F.2d 952, 956 (8th Cir. 1991).

The Sixth Circuit observed similarly that "a black Ameri

can would be particularly susceptible to the threat of

cross burning because of the historical connotations of

violence associated with the act." Salyer, 893 F.2d 116.

That crossburning is a threatening act on the basis of race

is uncontested.

Indeed, there is no doubt in anyone's mind what

crossburning connotes, conveys, portends, or does. In

U.S. v. Lee, Lonetta Miller, a seventy-one year old Black

woman testified on cross-examination as follows:

Q: Could you tell the ladies and gentlemen of

the jury what a cross burning means, whether it

is in the south or anywhere else?

A: Well it is a form of intimidation; the ku klux

klan uses it for threats; promises of violence,

and that sort of thing. From what I understand a

lot of the cross burnings in the south during the

civil rights movement preceded hangings and

that sort of thing. 935 F.2d, 956 n.5.

The Eighth Circuit observed there that defendants' cross

burning "was tantamount to intimidation by threat of

physical violence. It was not mere advocacy, but rather an

overt act of intimidation which, because of its historical

context, is often considered a precursor to or a promise of

violence against black people." 935 F.2d, 956.

All of the cases discussed above involved complaints

of crossburning in a context of inequality claims. Crosses

have been found burned to intimidate Blacks out of voter

registration in a jury selection case, Ford v. Hollowell,

8

385 F. Supp. 1392 (N.D. Miss. 1974); to induce targets to

refrain from exercising federally assured rights such as

travel, association, and speech under 42 U.S.C. § 1985(3),

Stevens v. Tillman, 855 F.2d 394 (7th Cir. 1988); and to

threaten and intimidate citizens from the free exercise or

enjoyment of a civil right under 42 U.S.C. § 241, U.S. v.

Salyer, 893 F.2d 113 (6th Cir. 1989), U.S. v. Worthy, 915 F.2d

1514 (11th Cir. 1990).

Two recent Court of Appeals decisions are partic

ularly apposite to the instant case. In one, the defendant

was charged with conspiracy to interfere with housing

rights by force or threat of force for burning a cross

within sight of an African American family's home. U.S.

v. Lee, 935 F.2d 952 (8th Cir. 1991) (upholding civil rights

claim under 42 U.S.C. § 3631(a) over First Amendment

defense). In another, the defendant pled guilty, inter alia,

to interference with housing rights, stating in the plea

agreement that defendants "decided to burn the cross in

the victims' yard 'because of the family's race and their

presence in the neighborhood . . . ' " U.S. v. Long, 935 F.2d

1207, 1209 (11th Cir. 1991) (allowing race to be taken into

account as a fact in sentencing enhancement).1

Existing equality law has long recognized similar

practices as violations of civil rights. Title 42 U.S.C.

§ 1971(b) provides that "no person . . . shall intimidate,

threaten, coerce, or attempt to intimidate, threaten, or

coerce any other person for the purpose of interfering

1 Some of these cases, such as Worthy, also invoke 18

U.S.C. § 844(h)(1), use of fire in the commission of a federal

felony. See e.g., U.S. v. Gresser, 935 F.2d 96 (6th Cir. 1991).

9

with the right of such other person to vote or to vote as

he may choose . . . " Where sharecropper-tenants in

possession of real estate under contract are threatened,

intimidated or coerced by landlords for the purpose of

interfering with their rights of franchise, U.S. v. Bruce, 353

F.2d 474 (5th Cir. 1965); U.S. v. Beaty, 288 F.2d 653 (6th Cir.

1961), burning a cross to attempt to intimidate a person

out of their voting rights should clearly be covered as

well. Similarly, 42 U.S.C. § 2000b provides for an action

for threatened loss of equal access to public facilities,

under which burning a cross would obviously be

included. Crossburning to exclude from housing rights,

as in the case at bar, is covered under 42 U.S.C. Section

3631(a), which prevents intimidation of "any person

because of his race, color, religion, sex . . . " from exercis

ing rights to fair housing. See also 42 U.S.C. § 3617 (1991).

In upholding Title II of the Civil Rights Act of 1964's

equal accommodations provision, this Court emphasized

that its "fundamental object . . . was to vindicate the

deprivation of personal dignity that surely accompanies

denials of equal access . . . " Heart of Atlanta Motel, Inc. v.

U.S., 379 U.S. 241, 250 (1964). Cowering in terror at night

with your family on the floor of your own home in the

light of a terrorist cross burning on your lawn is surely a

deprivation of personal dignity equal to not being per

mitted to stay overnight in a motel on the road.

Other civil rights rubrics have long permitted civil

actions for conduct covered under § 292.02. Behavior

such as hanging a noose over a desk, Vance v. Southern

Bell, 863 F.2d 1503 (11th Cir. 1989) or in a supply room,

Taylor v. Jones, 653 F.2d 1196 (8th Cir. 1981), or writing

"KKK" on a tool shed in a workplace, Vaughn v. Pool

10

Offshore Co., 683 F.2d 922 (5th Cir. 1982) are legally action

able as discriminatory harassment on the basis of race.

Placing pornography in the workplace, arguably a type of

conduct based on gender under § 292.02, has been recog

nized as discriminatory sexual harassment under Title

VII. Robinson v. Jacksonville Shipyards, 760 F. Supp. 1486

(M.D. Fla. 1991) (posting sex pictures is sexual harass

ment over First Amendment defense); but cf. Rabidue v.

Osceola Refining Co., 805 F.2d 611 (6th Cir. 1986) (posting

sex pictures is not sexual harassment because pornogra

phy is pervasive; no First Amendment defense raised).

Purely verbal harassment is unproblematically

actionable as racial or sexual discrimination or both

under state and federal human rights laws. Rogers v.

EEOC, 454 F.2d 234 (5th Cir. 1971), cert, denied, 406 U.S.

957 (1972) (racial epithets); Friend v. Leidinger, 446 F. Supp.

361 (E.D. Va. 1977), aff'd., 588 F.2d 61 (4th Cir. 1978)

(racial harassment); Weiss v. U.S., 595 F. Supp. 1052 (E.D.

Va. 1984) (anti-Semitic epithets). Examples of sexual

harassment include Meritor Savings Bank v. Vinson, 477

U.S. 57, 65 (1986); Elenson v. City of Dundee, 682 F.2d 897

(11th Cir. 1982); Bohen v. East Chicago, 799 F.2d 1180, 1189

(7th Cir. 1986) (Posner, J., concurring) (sexual abuse and

vilification); Hicks v. Gates Rubber, 928 F,2d 966 (10th Cir.

1991) (racial and sexual harassment); Continental Can v.

State, 297 N.W.2d 241, 245-246 (Minn. 1980) (defendant

"wished slavery days would return so that he could

sexually train [plaintiff] and she would be his bitch," in

action for sexual harassment under state human rights

law).

11

Discrimination, it should be noted, is typically effec

tuated through words like "you're fired;" "it was essen

tial that the understudy to my administrative assistant be

a man," Davis v. Passman, 422 U.S. 228, 230 (1971); and

posted signs stating "whites only," See, e.g., Palmer v.

Thompson, 403 U.S. 217 (1971); Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer Co.,

392 U.S. 409 (1968); Blow v. North Carolina, 379 U.S. 684

(1965); Watson v. Memphis, 373 U.S. 526 (1963); see also

Pierson v. Ray, 386 U.S. 547 (1967). Other common exam

ples include "did you get any over the weekend?" Morgan

v. Hertz Corp., 542 F. Supp. 123, 128 (W.D. Tenn. 1981),

"sleep with me and I'll give you an A," Alexander v. Yale

Univ., 459 F. Supp. 1, 3-4 (D. Conn. 1977), aff'd., 631 F.2d

178 (2d Cir. 1980), and "walk more femininely, talk more

femininely, dress more femininely, wear makeup, have

[your] hair styled, and wear jewelry," Price Waterhouse v.

Hopkins, 490 U.S. 228, 235 (1989). Nearly every time a

refusal to hire or promote or accommodate is based on a

prohibited group ground, some verbal act either consti

tutes the discrimination or proves it.

To the knowledge of amicus, the First Amendment

has been raised as a defense in none of these cases, other

than to be rejected in Robinson (pornography) and Lee

(crossburning). Section 292.02 merely covers by express

language a small subset of facts that civil rights statutes

and rubrics have, without First Amendment controversy,

been permitted to cover under far broader prohibitions

for decades.

The civil rights approach favors the prohibition of all

invidious treatment that has as its consequence "implying

inferiority in civil society" for individuals on the basis of

their membership in identifiable social groups. Strauder v.

12

West Virginia, 100 U.S. (10 Otto) 303, 308 (1880). In a

context of social inequality, the practices prohibited by

§ 292.02 form integral links in systematic social discrimi

nation. They work to keep target groups in socially iso

lated, stigmatized, and disadvantaged positions through

the promotion of fear, intolerance, segregation, exclusion,

disparagement, vilification, degradation, violence, and

genocide. The harms range from immediate psychic

wounding and attack, Matsuda, Public Response to Racist

Speech: Considering the Victim's Story, 87 Mich. L. Rev.

2320, 2365-66 (1989), to well-documented consequent

physical aggression. Increasing Violence Against Minorities:

Hearing Before the Subcomm. on Crime of the House Comm,

on the Judiciary, 96th Cong., 2d Sess. 124-25 (1980). As

terrorist acts of social subordination, they effectuate

inequality through coercion, intimidation and harass

ment.

In this approach, the placing of Nazi swastikas pro

motes the inequality of Jews on the basis of religion (and

creates a false racial identification that has had genocide

as its consequence). Crossburnings promote white

supremacy - in this case, the inequality of African-Ameri

cans to whites - on the basis of race and color. Such

symbolic acts of social inequality are thus discriminatory

practices, an expressive form inequality takes. In the

instant case, the threat, although group-based, was

directed against a specific family. Their injuries were not

merely subjective, nor can their fears be said to be

unfounded. See e.g. Marshall v. Bramer, 110 RR.D. 232

(W.D. Ky. 1985) (Black couple whose home was destroyed

by arson after cross burning brings § 1985(3) action

against Klan as an organization). The statute's "alarm"

13

translates into moving out to avoid getting killed; its

"anger" and "resentment" could well, in a healthy per

son, become striking back in self-defense or in defense of

one's human dignity. "There is no persuasive reason to

wipe the statute from the books, unless we want to

encourage victims of such verbal assaults to seek their

own private redress." Gooding v. Wilson, 405 U.S. 518, 530

(1972) (Burger, ]., dissenting).

At minimum, acts such as crossburnings further the

social construction of a group as inferior, unequal, and

rightly disadvantaged. On a material level, many African

Americans were driven out of the South and forced to

relocate in places like Minnesota as a result of such acts.

Systematic liquidation due to membership in a group, as

occurred to Jews and others during the Holocaust, is the

ultimate inequality of which acts such as crossburning are

an integral part. In the case at bar, the crossburning is an

act of exclusion of Black residents from a neighborhood

where they have an equality right to live. It is a euphe

mism to say that this is what such acts communicate

when the fact is that this is what they do.

B. The Practices Of Inequality Prohibited By

§ 292.02 Are Not Protected By The First Amend

ment.

Crossburning is expressive action which promotes

racial inequality through its racist message and impact,

engendering terror and effectuating segregation. It

inflicts its harm through its meaning, as all threats do.

Intimidation by threats of physical violence is not pro

tected by the First Amendment. See, e.g., Watts v. United

14

States, 394 U.S. 705, 707 (1969); U.S. v. Orozco-Santilian,

903 F.2d 1262, 1265 (9th Cir. 1990). But physical violence

does not mark the constitutional line beyond which legis

lation is impermissible. U.S. v. Lee, 935 F,2d 952, 956 (8th

Cir. 1991). Where the harm the expression does to the

emotional, physical, and mental health of vulnerable

groups - groups the state has an interest in protecting -

outweighs its expressive value, even pure speech, on

balance, can be restricted. New York v. Ferber, 458 U.S. 747

(1982). Where the state interest is in eradicating discrimi

nation, and the speech interest is not of the highest order,

even written words can be regulated. Pittsburgh Press v.

Pittsburgh Comm'n. on Human Relations, 413 U.S. 376

(1973). With expressive conduct, a compelling govern

mental interest, narrowly pursued, can outweigh a First

Amendment interest. U.S. v. O'Brien, 391 U.S. 367 (1968).

Assuming arguendo that croSsburning, a public show of

force, falls within the scope of the First Amendment,

under these combined tests, crossburning may readily be

prohibited as under § 292.02.

The traditional approach to a statute such as § 292.02

is to construe it as kind of a prohibition on group defama

tion, as petitioner and his amici ACLU et al. have done.

This fails to recognize the overriding importance of

equality interests where the treatment of suspect classes

based on race or gender are involved. When abused

through speech, the victim's harm - hence the state's

interest in regulation - has traditionally been conceived

as protection of sensibilities from offense or guarding of

emotional tranquility. Cohen v. California, 403 U.S. 15

(1971); Street v. New York, 394 U.S. 576, 592 (1969). The

harm of the type of conduct covered by § 292.02 has

15

traditionally sounded more in defamation - injury to

group reputation - than discrimination - injury to group

status and treatment. While defamation recognizes dam

age, its damage is more ideational and less material than

the damage of discrimination, which recognizes the harm

of second-class citizenship and inferior social standing

with attendant m aterial deprivation of access to

resources, voice, and power. Certainly, being treated as a

second-class citizen furthers the second-class reputation

of the group of which one is a member, even as a

demeaned reputation permits and encourages social deni

gration and exclusion. But equality is an interest of Con

stitutional dimension; repute, however weighty, is not.

The failure to recognize the equality interest at stake in

"group libel" statutes, see e.g. Collin v. Smith, 578 F.2d

1197, 1199 (7th Cir. 1978) (ordinance prohibiting parade

permit for assemblies which, inter alia, incite violence,

hatred, abuse or hostility "by reason of reference to reli

gious, racial, ethnic, national or regional affiliation") cert,

denied, 439 U.S. 916 (1978), has trivialized the harm and

obscured the state interest, disabling the constitutional

defense of such laws against First Amendment attack.

In the civil rights context, it should be noted that

segregated lunch counters or toilets or water fountains

were not defended because of what they said - that is, as

symbolic speech or as expressions of political opinion -

although they were arguably both expressive and politi

cal. Racial segregation in education was not regarded as

protected speech to the extent it required verbal forms,

such as laws and directives, to create and sustain it, nor

was it legally regarded as actionable defamation against

16

African Americans, although a substantial part of its

harm was the message of inferiority it conveyed, as well

as its impact on the self-concept of Black children. Brown

v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483, 494 (1954); see also

Lawrence, If He Hollers Let Him Go: Regulating Racist

Speech on Campus, 1990 Duke Law Journal 901 (Brown

may be read as regulating the content of racist speech).

Yet the harm of segregation and other racist practices is at

least as much what it says as what it does, just as with

crossburning, what it says is indistinguishable from what

it does.

Where equality interests in regulating speech have

been explicitly articulated, overwhelmingly they have

prevailed. In Pittsburgh Press, because sex-segregated job

advertisements "in d ica te d ]" sex discrimination in

employment, this Court concluded that such speech "sig

naled that the advertisers were likely to show an illegal

sex preference in their hiring decisions." Pittsburgh Press

v. Pittsburgh Comm'n. on Human Relations, 413 U.S. 376,

389 (1973). A burning cross "signals" just as powerfully

that African Americans are not welcome in the neighbor

hood. See also Roberts v. U.S. Jaycees, 468 U.S. 609 (1984);

Hishon v. King & Spalding, 467 U,S. 69 (1983).

Where the harm of symbolic conduct is real rather

than symbolic, the value of the expression should be

weighed against the harm done. New York v. Berber, 458

U.S. 757, 763-64 (1982) (harm of child pornography out

weighs its expressive value). The value of crossburnings

17

"is exceedingly modest, if not de minimus." 459 U.S. 762.

Indeed, its only value lies in the harm it does.2

In the civil rights context, courts have increasingly

rejected First Amendment protections for racist harass

ment and intimidation, including through symbolic

means. In the Vietnamese Fishermen's case, the court

enjoined defendants from engaging in acts of violence,

intimidation, or harassment under 42 U.S.C. §§ 1981, 1983

and 1985 for symbolic acts including hanging an effigy of

a Vietnamese fisherman, walking around with guns, and

"burning crosses on property within the geographic area

where members of plaintiffs' class live and/or work with

out the consent of the owner of said property." Vietnamese

Fishermen's Ass'n. v. Knights of the Ku Klux Klan, 543 F.

Supp. 198, 220 (S. D. Tex. 1982). Similarly, in the Lac du

Flambeau Indians case, the court, finding a claim under 42

U.S.C. § 1985(3) based on a "campaign driven by racial

hostility toward Indians" as evidenced by verbal racial

insults, found an injunction against such activities out

side First Amendment scope. Lac du Flambeau Indians v.

Sto-p Treaty Abuse-Wis., 759 F. Supp. 1339, 1349, 1353 (W.D.

Wis. 1991).

In a related recognition, the Supreme Court of Geor

gia recently upheld an anti-mask law against a free

2 Outside the recognized civil rights context, but invoking

similar concerns, Justice Souter, concurring in Barnes v. Glen

Theatres, Inc., expressed a similar rationale for upholding a

restriction on nude dancing based on its "secondary effects,"

there, increased prostitution and sexual assault. I l l S.Ct. 2456,

2470. In the instant case, racial exclusion and intimidation is

the primary, indeed only, effect of the expression, making its

avoidance even weightier.

18

speech challenge, recognizing that the Klan's practice of

wearing masks worked to "intimidate, threaten, or create

an environment for impending violence," hence was not

protected speech, in a factual context in which the mask-

wearing "helped to create a climate of fear that prevented

Georgia citizens from exercising their civil rights." State v.

Miller, 398 S.E.2d 547, 550 (1990). Crossburnings are at

least as harassing, intimidating, and obstructive of pro

tected rights.

Conduct that communicates may invoke the First

Amendment but is not necessarily protected speech. This

Court permits expressive conduct to be regulated more

readily than other expression. It looks to see if such

regulation "furthers an important or substantial govern

mental interest; if the governmental interest is unrelated

to the suppression of free expression; and if the incidental

restriction on alleged First Amendment freedom is no

greater than is essential to the furtherance of that inter

est." U.S. v. O'Brien, 391 U.S. 367, 376-377 (1968). See also

Barnes v. Glen Theatre, Inc., I l l S.Ct. 2456 (1991) (nude

dancing case, reaffirming and adumbrating O'Brien).

Fiarm to a state interest does not become protected as

speech because it makes a statement in inflicting an

injury. As clarified in Texas v. Johnson, "a law directed at

the communicative nature of the conduct must . . . be

justified by the substantial showing of need that the First

Amendment requires . . . It is, in short, not simply the

verbal or nonverbal nature of the expression, but the

governmental interest at stake, that helps to determine

whether a restriction on that expression is valid." Texas v.

Johnson, 491 U.S. 397, 406-407 (1989) (flag-burning case).

19

The recent cases on flag-burning found the statutes

regulating it impermissible because they lacked a suffi

cient governmental interest other than that of sup

pressing a particular form of criticism of the government.

The expression of an idea through conduct may not be

regulated "simply because society finds the idea itself

offensive or disagreeable." Johnson, 491 U.S., 414. The

Court in dicta emphasized the. inadequacy of offensive

ness as a harm: "'[w]e are aware that desecration of the

flag is deeply offensive to many. But the same might be

said, for example, of virulent ethnic and religious

epithets . . . " U.S. v. Eichman, 110 S. Ct. 2402, 2410 (1990).

Protected groups are not in a position of power compara

ble to that of the government, and, in reality, nothing is

done to the country when its symbol is burned. By con

trast, crossburning, if unpunished, is tantamount to racial

supremacy and exclusion, like a "white only" sign only

nonverbal. Like most acts, crossburning expresses an

idea, but unlike other expressions of ideas, it is threaten

ing and coercive conduct on the basis of race. As noted by

the Seventh Circuit in Collin v. Smith, "It bears noting that

we are not viewing here a law which prohibits action

designed to impede the equal exercise of guaranteed

rights . . . or even a conspiracy to harass or intimidate

others and subject them thus to racial or religious

hatred . . . If we were, we would have a very different

case." 578 F.2d, at 1204, n.13. Creating a First Amendment

exception for an injured flag is not the same as recogniz

ing the state interest in protecting from discrimination

terrorized and constructively evicted Black citizens

awaiting what may well be a firebombing or a lynch mob.

20

This Court has made dear that, "concepts virtually

sacred to our Nation as a whole - such as the principle

that discrimination on the basis of race is odious and

destructive" must, as a matter of principle, remain dis

puted in the marketplace of ideas. Johnson, 491 U.S., 417.

The marketplace of ideas cannot be assumed to be an

equal place in a society in which some groups are system

atically unequal to others. But this reality need not be

confronted here, since the idea of racial equality can

remain disputed in St. Paul. The city, through § 292.02,

does not enforce its views in a dialogue on racial equality,

nor has St. Paul here adopted the instant regulation of

crossburning "because of disagreement with the message

it conveys." Community for Creative Non-Violence v. Watt,

468 U.S. 288, 295 (1984). Rather, this expressive conduct is

prohibited because it inflicts inequality through the deliv

ery of its message. As this Court observed in Jaycees,

upholding an equality claim over a First Amendment

association challenge, "acts of invidious discrimination in

the distribution of publicly available goods, services, and

other advantages cause unique evils that government has

a compelling interest to prevent - wholly apart from the

point of view such conduct may transmit . . . Ac

cordingly . . . such practices are entitled to no constitu

tional protection." Roberts v. U.S. Jaycees, 468 U.S. 609, 628

(1984). That the content of the message is politically racist

does not, ipso facto, make it protected speech. "[IJnvidious

private discrimination may be characterized as a form of

exercising freedom . . . protected by the First Amend

ment, but it has never been accorded affirmative constitu

tional protection." Norwood v. Harrison, 413 U.S. 455, 470

(1973). This case is not the time to start.

21

For St. Paul to side with equality as a basis for public

policy is not the same as officially imposing a conclusion

on a dialogue. A crossburning is not a dialogue, it is a

discriminatory act. The state need not remain neutral

when racial inequality is practiced, including through

expressive conduct. A law against crossburning means

only that second-class citizenship may not be imposed in

this way. When equality is a constitutional mandate, the

idea that some people are inferior to others on the basis

of group membership has been authoritatively rejected as

the basis for public policy. Practices based on this idea are

not insulated from regulation on the ground that the

ideas they express cannot be rejected by law, nor are

legislative attempts to address such practices invalid

because they take a position in favor of human equality.

Burning crosses, placing Nazi swastikas, and posting

pornography in workplaces serve none of the purposes

for which speech is protected, any more than verbal racial

and sexual harassment or "white only" signs do. Free

speech is valued because it encourages political dissent,

debate, and participation in self-government, Emerson,

THE SYSTEM OF FREEDOM OF EXPRESSION 6-7 (1970),

Meiklejohn, FREE SPEECH AND ITS RELATION TO

SELF-GOVERNMENT 27 (1948); promotes diversity, tol

erance, and self-restraint, Bollinger, THE TOLERANT

SOCIETY 9-11 (1986); manages social change and social

conflict, Emerson, at 7; advances knowledge and pro

motes the discovery of truth, Mill, ON LIBERTY 16-52 (A.

Castell ed. 1947); and promotes individual self-fulfill

ment, Baker, Scope of the First Amendment Freedom of

Speech, 25 U.C.L.A. L. Rev. 964, 995-996 (1978). The acts

prohibited by § 292.02, by contrast, quash dissent by

22

silencing the voices of disadvantaged groups through

terrorism, often insuring that the victims are so intimi

dated that the most aggressive and coercive verbal

attacks upon them never become "fighting words"

because they cannot or do not fight back.3 Such acts also

inhibit truth-seeking because they intimidate disadvan

taged groups from asserting their truth and their point of

view. They undermine social diversity through exclusion

and discourage community participation by demeaning

the human worth and self-esteem of their targets. If big

ots are fulfilled through such acts, it is at the expense of a

welcoming and tolerant environment for others.

The hatemongering prohibited by § 292.02 silences

the speech of the less powerful as it marginalizes and

segregates them. The official imprimatur of approval that

would be secured for such conduct by protecting it as

expression would do incalculable harm to the "hearts and

minds," Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483, 494

(1954), of its victims, inhibiting progress toward civil

equality, and delegitimating the First Amendment.

In prohibiting such practices, the St. Paul ordinance

"responds precisely to the substantive problem which

legitimately concerns" government and abridges no more

freedom of speech than necessary to accomplish that

purpose. See City Council of Los Angeles v. Taxpayers for

Vincent, 466 U.S. 789, 810 (1984); Ward v. Rock Against

Racism, 491 U.S. 781 (1989). Moreover, the provision aims

3 This is to suggest that the "fighting words" doctrine

implicitly assumes an equality of social vulnerability, safety,

and state solicitude that cannot be assumed for groups that

have historically been the targets of discrimination.

23

to stop intimidation from protected rights and to advance

equality, not to suppress dissident speech. While the con

tent of the message of a burning cross may represent

dissent from the national consensus reflected in legal

mandates of equality, it offers no dissent from the over

whelming reality of racial inequality that continues to

afflict social life. Bell, AND WE ARE NOT SAVED: THE

ELUSIVE QUEST FOR RACIAL JUSTICE (1987). Cross

burning should not be romanticized as a lonely and

unheeded critique of a powerful status quo. Its racism

entrenches, embodies, and advances society's most

repressive and antiegalitarian norms, indefensible in a

society that has equality as a constitutional guarantee.

If St. Paul burned a cross at an official ceremony, it

would discriminate on the basis of race in violation of the

Fourteenth Amendment. The fact the conduct was expres

sive would be no defense. This would be as virulent and

shocking an act "designed to maintain White Supremacy"

as has ever been seen. Loving v. Virginia, 388 U.S. 1, 11

(1967) (invalidating antimiscegenation laws). What would

be discriminatory for government to do can be recog

nized as discriminatory in society through legislation. By

prohibiting such conduct when it occurs between its citi

zens, the city acts against socially institutionalized

inequality and, indirectly, against the negative group

animus that drives it.

Section 292.02 is as much an equality provision as if it

were part of the human rights code. Like the provision

upheld over First Amendment concerns in Jaycees, the

ordinance reflects Minnesota's historically "strong com

mitment to eliminating discrimination and assuring its

24

citizens equal access to publicly available goods and ser

vices." Roberts v. U.S. Jaycees, 468 U.S. 609, 624 (1984).

Had equality been recognized as the constitutional inter

est at stake in group defamation, it would have sup

ported Justice Frankfurter's opinion upholding Illinois'

statute in Beauharnais, not overruled to this day, that "a

man's job and his educational opportunities and the dig

nity accorded him may depend as much on the reputation

of the racial and religious group to which he willy-nilly

belongs, as on his own merits." Beauharnais v. Illinois, 343

U.S. 250, 263 (1952). It would also support the reserva

tions based on Beauharnais expressed by some members

of this Court in the Skokie case. Smith v. Collin, 439 U.S.

916 (1978) (Blackmun, }., with whom White, }., joins,

dissenting from denial of cert, to resolve possible conflict

with Beauharnais). See also R. v. Keegstra, [1991] 2 W.W.R.

1 (Supreme Court of Canada upholding hate propaganda

statute on equality rationale under Canadian Charter of

Rights and Freedoms). As the Eighth Circuit concluded in

an action for a crossburning, "[t]o protect the inhabitants

of this nation from such an attack on civil rights does not

violate the spirit of the first amendment." U.S. v. Lee, 935

F.2d 952, 956 (8th Cir. 1991).

II. AS APPLIED TO DISCRIMINATORY EXPRESSIVE

CONDUCT, § 292.02 IS NOT SUBSTANTIALLY

OVERBROAD.

First Amendment overbreadth doctrine provides an

exception to the rule that a person to whom a statute may

constitutionally be applied may not challenge it on

grounds that it may conceivably be applied unconstitu

tionally to others in situations not before the court. The

25

concern is that a sweeping statute, or one incapable of

limitation, can chill much protected expression before it

can be stopped. Broadrick v. Oklahoma, 413 U.S. 601 (1973).

As explained in Broadrick, the function of this exception,

a limited one at the outset, attenuates as the

otherwise unprotected behavior that it forbids

the State to sanction moves from "pure speech"

toward conduct and that conduct - even if

expressive - falls within the scope of otherwise

valid criminal laws that reflect legitimate state

interests in maintaining comprehensive controls

over harmful, constitutionally unprotected con

duct. 413 U.S., 615.

While the Court may have been thinking of conduct in

which the harmful communicative impact is separate from

the harm of the conduct as such, the considerations in per

mitting regulation are no less strong when the two are one,

as here. The laws under which crossburning has previously-

been prohibited as a civil rights violation have long been

recognized as valid. Crossburning, while expressive, is less

"pure speech" and more conduct than is child pornography.

See Brockett v. Spokane Arcades, Inc., 472 U.S. 491, 504 n.12

(1985) ("The Court of Appeals erred in holding that the

Broadrick substantial overbreadth requirement is inapplicable

where pure speech rather than conduct is at issue. Berber

specifically held to the contrary."). The equality interests in

eradicating racial discrimination, of which crossburning and

related acts are instances, are "fundamental, overriding." Bob

Jones Univ. v. U.S., 461 U.S. 574, 604 (1983) (equality as public

policy upheld over free exercise claim). And § 292.02 has

already been subjected to a limiting construction by the state

court. Matter of Welfare of R.A.V., 464 N.W.2d 507 (Minn.

1991).

26

Like the statute in Ferber, § 292.02 is "the paradigma

tic case of a statute whose legitimate reach dwarfs its

arguably impermissible applications," hence is not sub

stantially overbroad. New York v. Ferber, 458 U.S. 747, 773.

The overwhelming majority of the speech acts covered

are already unprotected speech even apart from an equal

ity rationale. There is no right to burn crosses on public

property, Adderley v. State of Florida, 385 U.S. 39 (1966), or

on the private property of another without permission,

Lloyd Cory. v. Tanner, 407 U.S. 551 (1972). That leaves

burning crosses with permission on others' property and

on one's own property - a group of instances so small

that the overbreadth doctrine, which is "strong medi

cine," Broadrick, 413 U.S. 613, is inappropriate. "The

premise that a law should not be invalidated for over

breadth unless it reaches a substantial number of imper

missible applications is hardly novel." Ferber, 458 U.S.,

771.

This result is distinguishable from the invalidation

on overbreadth grounds of a statute prohibiting

"opprobrious words or abusive language" in Gooding v.

Wilson, although the facts of both cases involve "bullying

tacticjs]" Gooding v. Wilson, 405 U.S. 518, 535 (Blackmun,

}., dissenting) which raise speech concerns. The statute at

issue in Gooding was directed only to spoken words, not

conduct, and, as applied, sought to safeguard the sensi

bilities of police officers rather than the equality rights of

protected groups. Even so, some justices found Cha-plinsky

undermined by that overbreadth invalidation: "If this is

what the overbreadth doctrine means, and if this is what

it produces, it urgently needs re-examination." 405 U.S.,

27

537 (Blackmun, with whom Burger, C. ]., joins, dissent

ing).

-----------------♦-----------------

CONCLUSION

The judgment of the Minnesota Supreme Court

should be affirmed.

Respectfully submitted,

/s/ Catharine A. MacKinnon

C atharine A. M acK innon*

625 S. State Street

Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109-1215

(313) 747-4046

B urke M arshall

127 Wall Street

New Haven, Connecticut 06520

(203) 432-4953

Attorneys for Amicus Curiae

* Counsel of Record

August 23, 1991