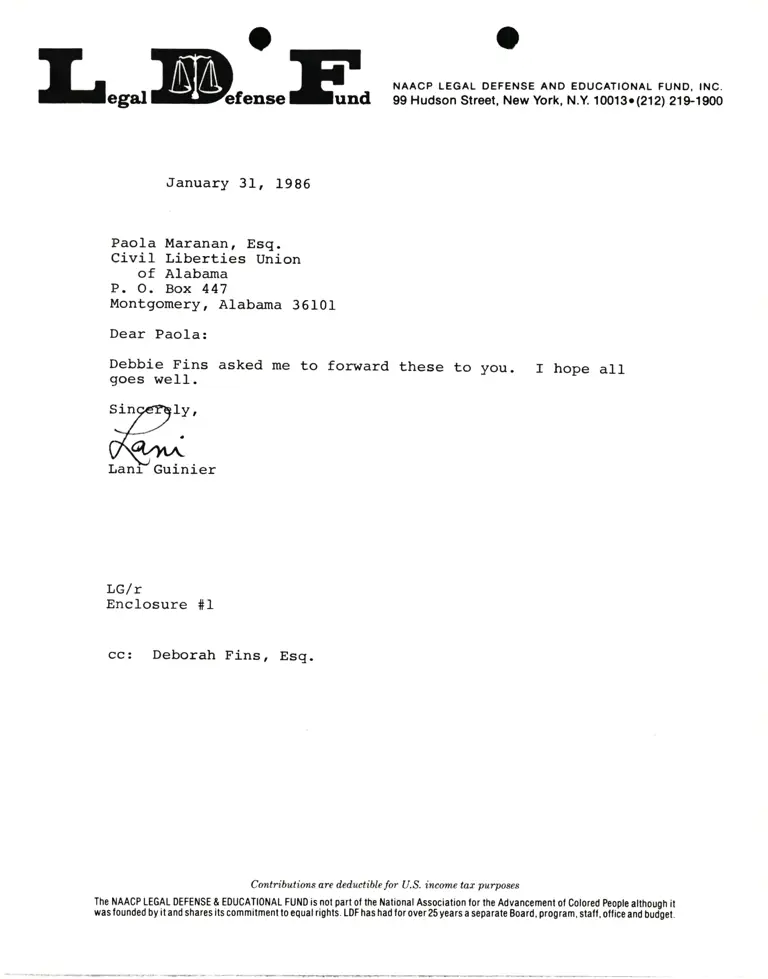

Correspondence from Lani Guinier to Paola Maranan, Esq. (Civil Liberties Union of Alabama)

Correspondence

January 31, 1986

Cite this item

-

Legal Department General, Lani Guinier Correspondence. Correspondence from Lani Guinier to Paola Maranan, Esq. (Civil Liberties Union of Alabama), 1986. 7cb7c467-e992-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/6fb5d89f-1b70-47be-aa87-3202ec5f93c4/correspondence-from-lani-guinier-to-paola-maranan-esq-civil-liberties-union-of-alabama. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

Less,Ue:.H,

January 31, 1986

Pao1a I{aranan, Esq.

Civil Liberties Union

of Alabama

P. O. Box 447

Ivlontgom€ry, Alabama 3610I

Dear Paola:

Debbie Fins asked me to forward these to you.

goes weIl.

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE ANO EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.

99 Hudson Street, New York, N.Y. 10013o(212) 21S'1900

f hope all

ly,

Guinier

LG/ r

Enclosure #1

cc: Deborah Fins, Esg.

Contributions are dcductible lor U.S. incomc taz purposes

The NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE & EDUCAIIONAL FUND is not part ol the National Association for the Advancement of Colored PeoDte atthouoh it

was lounded by it and shares its commitment to equal rights. LDF has had lor over 25 years a separate Board, program, stall, olliie and bud-get.