Buchanan v. Warley Decision

Public Court Documents

November 5, 1917

19 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Buchanan v. Warley Decision, 1917. d9431407-b79a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/6fc23869-21f7-44d9-af4c-f127477f04a4/buchanan-v-warley-decision. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

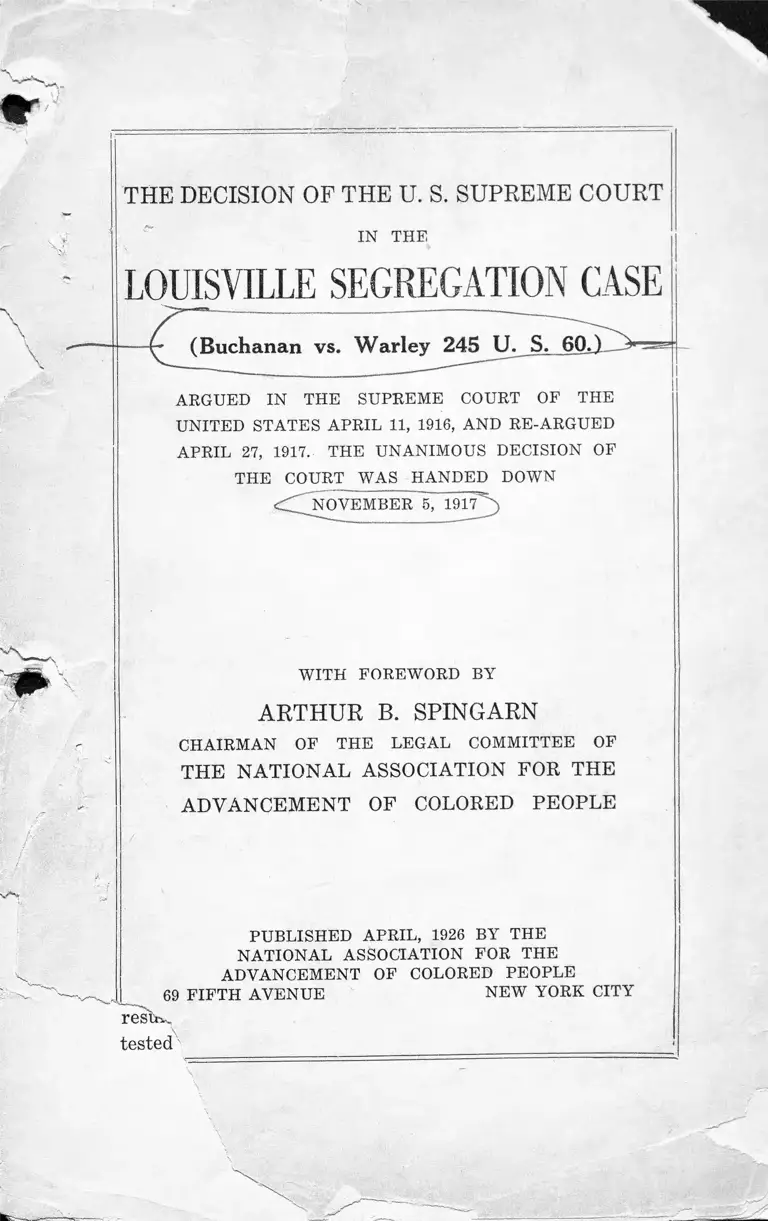

THE DECISION OF THE U. S. SUPREME COURT

IN THE

LOUISVILLE SEGREGATION CASE

(Buchanan vs. Warley 245 U. S. 60.)

ARGUED IN THE SUPREME COURT OB' THE

UNITED STATES APRIL 11, 1916, AND RE-ARGUED

APRIL 27, 1917. THE UNANIMOUS DECISION OF

THE COURT WAS HANDED DOWN

No v e m b e r ' s, 1917

WITH FOREWORD BY

ARTHUR B. SPINGARN

CHAIRMAN OF THE LEGAL COMMITTEE OF

THE NATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR THE

ADVANCEMENT OF COLORED PEOPLE

PUBLISHED APRIL, 1926 BY THE

NATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR THE

ADVANCEMENT OF COLORED PEOPLE

FIFTH AVENUE NEW YORK CITY

tested

FOREWORD

Sporadic attempts to legalize enforced residential

segregation have never been uncommon, but it was not

until the second decade of this century that there appeared

an apparently organized attempt to prohibit by legislation

the free scope of colored people in the purchase and occu

pancy of homes. Until then, the matter had been generally

left to the process of natural group cohesion, aided more

or less by economic pressure and public opinion, with an

occasional more sinister influence.

Commencing about 1910, a wave of residential segrega

tion laws swept the country, city after city in the southern

and border states passed ordinances, the purpose and effect

of which were to keep colored people from invading the

areas which had hitherto been restricted to white residents.

All of these ordinances prohibited whites from living in

colored districts and on their face purported to protect

colored people as well as white, but, of course, no one for

a moment believed that they were anything but the initial

step in an attempt to create Negro Ghettos throughout the

United States, with the inevitable crowding, poor lighting

and worse sanitation, and the resultant higher delinquency

and crime rates, greater infant mortality and higher death

rates, from tuberculosis and the other infectious and con

tagious diseases, together with all the other attendant evils

which inevitably result from adverse environment.

More than a dozen cities, among them Baltimore, Md.,

Dallas, Texas, Asheville, N. C., Richmond, Va., St. Louis,

Mo., and Louisville, Ky., within a year passed such ordi

nances ; these differed in detail but all aimed at the same

result. The constitutionality of a number of these were

tested and generally were upheld by the State Courts.

The National Association for the Advancement of

Colored People, convinced of their unconstitutionality and

illegality, made a careful test of the ordinance passed in

Louisville, Ky., and carried the case to the Supreme Court

of the United States. The case was argued on behalf of

the Association by its President, Mr. Moorfield Storey, and

resulted in a unaminous decision in its favor, which is the

decision printed in this pamphlet. This case established

the principle for all time, that in the United States, no state,

city or village can by law prohibit colored men or women,

because of their color, from purchasing any real property

they may be able to buy and from occupying any property

they can buy or rent.

It does not make any difference what form a statute

or law or ordinance may take. If its purpose is to restrict

the occupancy or purchase and sale of property, of which

occupancy is an incident, solely because of the color of the

proposed occupant or purchaser of the premises, that stat

ute, law or ordinance is illegal, unconstitutional and void.

This is the law of the land, proclaimed by the highest

tribunal of the United States and any decision by any other

court, state or federal, which does not follow the law there

laid down is illegal and wrong. If a segregation ordinance

or statute is passed in your city or state, it is illegal. Its

legality should be tested in the courts, and though the de

cision may at first be adverse, if the case is carried to the

Supreme Court of the United States and is properly pre

pared and argued, that court will ultimately declare the

statute or ordinance illegal and unconstitutional under the

doctrines enunciated in Buchanan vs. Warley here

reprinted.

ARTHUR B. SPINGARN,

Chairman of Legal Committee,

National Association for the

Advancement of Colored People

Supreme Court of the United States

Mr. Justice Day delivered the opinion of the Court.

Buchanan, plaintiff in error, brought an action in the

Chancery Branch of Jefferson Circuit Court of Kentucky

for the specific performance of a contract for the sale of cer

tain real estate situated in the City of Louisville at the

' corner of 37th Street and Pflanz Avenue. The offer in

writing to purchase the property contained a proviso:

“ It is understood that I am purchasing the above

property for the purpose of having erected thereon a

house which I propose to make my residence, and it is

a distinct part of this agreement that I shall not be

required to accept a deed to the above property or to

pay for said property unless I have the right under the

laws of the State of Kentucky and the City of Louisville

to occupy said property as a residence.”

No. 33 — October Term, 1917

245 U. S. 60

Charles H. Buchanan,

Plaintiff in Error

William Warley

vs.

In Error to the

Court of Appeals

of the State of

Kentucky.

November 5, 1917

This offer was accepted by the plaintiff.

6

To the action for specific performance the defendant

by way of answer set up the condition above set forth,

that he is a colored person, and that on the block of which

the lot in controversy is a part, there are ten residences,

eight of which at the time of the making of the contract

were occupied by white people, and only two (those

nearest the lot in question) were occupied by colored

people, and that under and by virtue of the ordinance of

the City of Louisville, approved May 11, 1914, he would

not be allowed to occupy the lot as a place of residence.

In reply to this answer the plaintiff set up, among other

things, that the ordinance was in conflict with the Four

teenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United

States, and hence no defense to the action for specific per

formance of the contract.

In the court of original jurisdiction in Kentucky, and

in the Court of Appeals o f that State, the case was made

to turn upon the constitutional validity of the ordinance.

The Court of Appeals of Kentucky, 165 Ky. 559, held the

ordinance valid and of itself a complete defense to the

action.

The title of the ordinance is : “ An ordinance to prevent:

conflict and ill-feeling between the white and colored

races in the City of Louisville, and to preserve the public’

peace and promote the general welfare by making

reasonable provisions requiring as far as practicable, the

use of separate blocks for residences, places of abode, and

places of assembly by white and colored people respect

ively.”

By the first section of the ordinance it is made unlaw

ful for any colored person to move into and occupy as a

residence, place of abode, or to establish and maintain as

7

a place of public assembly any house upon any block

’upon which a greater number of houses are occupied as

residences, places of abode, or places of public assembly

%y white people than are occupied as residences, places

of abode, or places of public assembly by colored people.

Section 2 provides that it shall be unlawful for any

white person to move into and occupy as a residence,

place of abode, or to establish and maintain as a place of

public assembly any house upon any block upon which a

greater number of houses are occupied as residences,

places of abode or places of public assembly by colored

people than are occupied as residences, places of abode

or places of public assembly by white people.

Section 4 provides that nothing in the ordinance shall

affect the location of residences, places of abode or places

of assembly made previous to its approval; that nothing

contained therein shall be construed so as to prevent the

occupancy of residences, places of abode or places of

.^assembly by white or colored servants or employees of

occupants of such residences, places of abode or places

of public assembly on the block on which they are so

Employed, and that nothing therein contained shall be

construed to prevent any person who, at the date of the

passage of the ordinance, shall have acquired or possessed

th| right to occupy any building as a residence, place of

abode or place of assembly from exercising such a right;

th’at nothing contained in the ordinance shall prevent the

owner of any building, who when the ordinance became

effective, leased, rented, or occupied it as a residence,

place o f abode or place of public assembly for colored

persons, from continuing to rent, lease or occupy such

residence, place of abode or place of assembly for such

persons, if the owner shall so desire; but if such house

8

should, after the passage of the ordinance, be at any time

leased, rented or occupied as a residence, place of abode

or place of assembly for white persons, it shall not there-,

after be used for colored persons, if such occupation'

would then be a violation of Section One of the ordinance ;*

that nothing contained in the ordinance shall prevent the

owner of any building, who when the ordinance became

effective, leased, rented or occupied it as a residence,

place of abode, or place of assembly for white persons

from continuing to rent, lease or occupy such residence,

place of abode or place of assembly for such purpose, if

the owner shall so desire, but if such household, after the

passage of the ordinance, be at any time leased, rented or

occupied as a residence, place of abode or place of assem

bly for colored persons, then it shall not thereafter be

used for white persons, if such occupation would then be

a violation of Section Two thereof.

The ordinance contains other sections and a violation

of its provisions is made an offense.

The assignments of error in this court attack the ordi

nance upon the ground that it violates the Fourteenth

Amendment of the Constitution of the United States, iî

that it abridges the privileges and immunities of citizens

of the United States to acquire and enjoy property, takeiS

property without due process of law, and denies equal

protection of the laws.

The objection is made that this writ of error should be dis

missed because the alleged denial of constitutional rights

involves only the rights of colored persons, and the plaintiff

in error is a white person. This court has frequently held

that while an unconstitutional act is no law, attacks upon the

validity of laws can only be entertained when made by those

whose rights are directly affected by the law or ordinance

9

in question. Only such persons, it has been settled, can be

heard to attack the constitutionality of the law or ordinance.

But this case does not run counter to that principle.

The property here involved was sold by the plaintiff in

error, a white man, on the terms stated, to a colored man;

the action for specific performance was entertained in the

court below, and in both courts the plaintiff’s right to have

the contract enforced was denied solely because of the effect

of the ordinance making it illegal for a colored person to oc

cupy the lot sold. But for the ordinance the state courts

would have enforced the contract, and the defendant would

have been compelled to pay the purchase price and take a

conveyance of the premises. The right of the plaintiff in er

ror to sell his property was directly involved and necessari

ly impaired because it was held in effect that he could not sell

the lot to a person of color who was willing and ready to

acquire the property, and had obligated himself to take it.

This case does not come within the class wherein this court

has held that where one seeks to avoid the enforcement of

a law or ordinance he must present a grievance of his own,

and not rest the attack upon the alleged violation of an

other’s rights. In this case the property rights of the plain

tiff in error are directly and necessarily involved. See

Truax v. Raich, 239 U. S. 33, 38.

We pass then to a consideration of the case upon its

merits. This ordinance prevents the occupancy of a lot in

the City of Louisville by a person of color in a block where

the greater number of residences are occupied by white

persons; where such a majority exists colored persons are

excluded. This interdiction is based wholly upon color;

simply that and nothing more. In effect, premises situated

as are those in question in the so-called white block are

10

effectively debarred from sale to persons of color, because

if sold they cannot be occupied by the purchaser nor by him

sold to another of the same color.

This drastic measure is sought to be justified under the

authority of the State in the exercise of the police power.

It is said such legislation tends to promote the public peace

by preventing racial conflicts,; that it tends to . maintain

racial purity; that it prevents the deterioration of property

owned and occupied by white people, which deterioration,

it is contended, is sure to follow the occupancy of adjacent

premises by persons of color.

The authority of the State to pass laws in the exercise

of the police power, having for their object the promotion

of the public health, safety and welfare is very broad as has

been affirmed in numerous and recent decisions of this court.

Furthermore the exercise of this power, embracing nearly

all legislation of a local character is not to be interfered

with by the courts where it is within the scope of legislative

authority and the means adopted reasonably tend to accom

plish a lawful purpose.' But it is equally well established

that the police power, broad as it is, cannot justify the

passage of a law or ordinance which runs counter to the

limitations of the Federal Constitution; that principle has

been so frequently affirmed in this court that we need not

stop to cite the cases. "

The Federal Constitution and laws passed within its

authority are by the express terms of that instrument made

the supreme law of the land. The Fourteenth Amendment

protects life, liberty, and property from invasion by the

states without due process of law. Property is more than

the mere thing which a person owns. It is elementary that

it includes the right to acquire, use and dispose of it. The

11

Constitution protects these essential attributes of property.

Holden v. Hardy, 169 U. S. 366, 391. Property consists of

the free use, enjoyment, and disposal of a person’s acquisi-

'% tions without control or diminution save by the law of the

land. 1 Blackstone’s Commentaries, (Cooley’s Ed.) 127.

True it is that dominion over property springing from

ownership, is not absolute and unqualified. The disposition

and use of property may be controlled in the exercise of the

police power in the interest of the public health, conveni

ence, or welfare. Harmful occupations may be controlled

and regulated. Legitimate business may also be regulated

in the interest of the public. Certain uses of property may

be confined to portions of the municipality other than the

resident district, such as livery stables, brickyards and the

like, because of the impairment of the health and comfort

of the occupants of neighboring property. Many illustra

tions might be given from the decisions of this court, and

other courts, of this principle, but these cases do not touch

the one at bar.

The concrete question here is: May the occupancy, and

necessarily, the purchase and sale of property of which oc

cupancy is an incident, be inhibited by the states, or by one

of its municipalities, solely because of the color of the pro-

" s posed occupant of the premises? That one may dispose

of his property, subject only to the control of lawful enact

ments curtailing that right in the public interest, must be

v conceded. The question now presented makes it pertinent

to enquire into the constitutional right of the white man to

sell his property to a colored man, having in view the legal

status of the purchaser and occupant.

Following the Civil War certain amendments to the Fed

eral Constitution were adopted, which have become an inte

gral part of that instrument, equally binding upon all the

12

states and fixing certain fundamental rights which all are

bound to respect. The Thirteenth Amendment abolished

slavery in the United States and in all places subject to their

jurisdiction, and gave Congress power to enforce the

Amendment by appropriate legislation. The Fourteenth

Amendment made all persons born or naturalized in the

United States, citizens of the United States and of the states

in which they reside, and provided that no state shall make

or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or

immunities of citizens of the United States, and that no

state shall deprive any person of life, liberty, or property

without due process of law, nor deny to any person the

equal protection of the laws.

The effect of these amendments was first dealt with by

this court in The Slaughter House Cases, 16 Wallace 36.

The reasons for the adoption of the amendments were elabo

rately considered by a court familiar with the times in

which the necessity for the amendments arose and with the

circumstances which impelled their adoption. In that case

Mr. Justice Miller, who spoke for the majority, pointed out

that the colored race, having been freed from slavery by

the Thirteenth Amendment, was raised to the dignity of .

citizenship and equality of civil rights by the Fourteenth

Amendment, and the states were prohibited from abridging

the privileges and immunities of such citizens, or depriving t

any person of life, liberty, or property without due process

of law. While a principle purpose of the latter Amendment |

was to protect persons of color, the broad language used

was deemed sufficient to protect all persons, white or black,

against discriminatory legislation by the states. This is

now the settled law. In many of the cases since arising

the question of color has not been involved and the cases

have been decided upon alleged violations of civil or prop-

13

erty rights irrespective of the race or color of the complain

ant. In The Slaughter House Cases it was recognized that

the chief inducement to the passage of the amendment was

the desire to extend Federal protection to the recently

emancipated race from unfriendly and discriminating leg

islation by the states.

In Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U. S. 303, this court

held that a colored person charged with an offense was de

nied due process of law by a statute which prevented colored

men from sitting on the jury which tried him. Mr. Justice

Strong, speaking for the court, again reviewed the history

of the Amendments, and among other things, in speaking

of the Fourteenth Amendment, said:

“It (the Fourteenth Amendment) was designed to

assure to the colored race the enjoyment of all the

civil rights that under the law are enjoyed by white

persons, and to give to that race the protection of the

general government, in that enjoyment, whenever it

should be denied by the States. It not only gave citi

zenship and privileges of citizenship to persons of color

but it denied to any State the power to withhold from

them the equal protection of the laws, and authorized

Congress to enforce its provisions by appropriate leg

islation * * * It ordains that no State shall make or

enforce any laws which may abridge the privileges or

immunities of citizens of the United States * * * It

ordains that no State shall deprive any person of life,

liberty, or property without due process of law, or deny

to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protec

tion of the laws.

“ What is this but declaring that the laws in the

States shall be the same for the black as for the white,

that all persons, whether colored or white, shall stand

14

equal before the laws of the States, and, in regard to

the colored race, (for whose protection the Amend- |

ment was primarily designed) that no discrimination

shall be made against them by law because of their t

color? * * *

“ The Fourteenth Amendment makes no attempt to

enumerate the rights it designs to protect. It speaks in

general terms and those are as comprehensive as pos

sible. . Its language is prohibitory; but every prohibi

tion implies the existence of rights and immunities,

prominent among which is an immunity from inequal-

ty of legal protection either for life, liberty or property.

Any state action which denies this immunity to a col

ored man is in conflict with the Constitution.”

Again this court in Ex parte Virginia, 100 U. S. 339, 347,

speaking of the Fourteenth Amendment, said:

“ Whoever, by virtue of public position under a State

Government, deprives another of property, life or lib

erty, without due process of law, or denies or takes ,

away the equal protection of the laws, violates the con

stitutional inhibition; and as he acts in the name and

for the State and is clothed with the State’s power, }

his act is that of the State.”

In giving legislative aid to these constitutional provisions

Congress enacted in 1866, Chap. 31, Sec. 1, 14th Stat. 27,

that:

“ All citizens of the United States shall have the

same right in every State and Territory, as is enjoyed

by white citizens thereof to inherit, purchase, lease,

sell, hold, and convey real and personal property.”

15

And in 1870, by Chap. 114, Sec. 16, 16th Stat. 144, that:

“ All persons within the jurisdiction of the United

States shall have the same right in every State and

Territory to make and enforce contracts, to sue, be

parties, give evidence, and to the full and equal bene

fit of all laws and proceedings for the security of per

sons and property as is enjoyed by white citizens, and

shall be subject to like punishment, pains, penalties,

taxes, licenses and exactions of every kind, and no

other.”

In the face of these constitutional and statutory provi

sions, can a white man be denied, consistently with due

process of law, the right to dispose of his property to a

purchaser by prohibiting the occupation of it for the sole

reason that the purchaser is a person of color intending to

occupy the premises as a place of residence ?

The statute of 1866, originally passed under sanction of

the Thirteenth Amendment, 14 Stat. 27, and practically re

enacted after the adoption of the Fourteenth Amendment,

16 Stat. 144, expressly provided that all citizens of the

United States in any state shall have the same right to pur

chase property as is enjoyed by white citizens. Colored

persons are citizens of the United States and have the right

to purchase property and enjoy and use the same without

laws discriminating against them solely on account of color.

Hall v. DeCuir, 95 U. S. 485, 508. These enactments did

not deal with the social rights of men, but with those fun

damental rights in property which it was intended to secure

upon the same terms to citizens of every race and color.

Civil Rights Cases, 109 U. S. 3, 22. The Fourteenth

Amendment and these statutes enacted in furtherance of

its purpose operate to qualify and entitle a colored man to

16

acquire property without state legislation discriminating

against him solely because of color.

The defendant in error insists that Plessy v. Ferguson,

163 U. S. 537, is controlling in principle in favor of the

judgment of the court below. In that case this court held

that a provision of a statute of Louisiana requiring rail

way companies carrying passengers to provide in their

coaches equal but separate accommodations for the white

and colored races did not run counter to the provisions of

the Fourteenth Amendment. It is to be observed that in

that case there was no attempt to deprive persons of color

of transportation in the coaches of the public carrier, and

the express requirements were for equal though separate

accommodations for the white and colored races. In

Plessy v. Ferguson, classification of accommodations was

permitted upon the basis of equality for both races.

In the Berea College Case, 211 U. S. 45, a state statute

was sustained in the courts of Kentucky, which, while

permitting the education of white persons and Negroes in

different localities by the same incorporated institution,

prohibited their attendance at the same place, and in this

court the judgment of the Court of Appeals of Kentucky

was affirmed solely upon the reserved authority of the

legislature o f Kentucky to alter, amend, or repeal charters

of its own corporations, and the question here involved

was neither discussed nor decided.

In Carey v. City of Atlanta, 143 Ga. 192, the Supreme

Court of Georgia, holding an ordinance, similar in principle

to the one herein involved, to be invalid, dealt with Plessy

v. Ferguson and The Berea College Case, in language so

apposite that we quote a portion of it.

“ In each instance the complaining person was afford

ed the opportunity to ride, or to: attend the institutions

17

of learning, or afforded the thing of wnatever nature

to which in the particular case he was entitled. The

S’ most that was done was to require him as a member of

̂ a class to conform with reasonable rules in regard to

the separation of the races. In none of them was he

denied the right to use, control, or dispose of his prop

erty, as in this case. Property of a person, whether

as a member of a class or as an individual, cannot be

taken without due process of law. In the recent case of

McCabe v. Atchison, etc., Ry. Co., 235 U. S. 151, where

the court had under consideration a statute which al

lowed railroad companies to furnish dining-cars for

white people and to refuse to furnish dining-cars al

together for colored persons, this language was used in

reference to the contentions of the attorney-general;

‘This argument with respect to volume of traffic seems

to us to be without merit. It makes the constitutional

right depend upon the number of persons who may be

discriminated against, whereas the essence of the con

stitutional right is that it is a personal one.’

“ The effect of the ordinance under consideration was

not merely to regulate business or the like, but was to

I destroy the right of the individual to acquire, enjoy,

i and dispose of his property. Being of this character

* , it was void as being opposed to the due-process clause

' of the constitution.”

ks

That there exists a serious and difficult problem arising

from a feeling of race hostility which the law is powerless

to control, and to which it must give a measure of consider

ation, may be freely admitted. But its solution cannot be

promoted by depriving citizens of their constitutional

rights and privileges.

18

As we have seen, this court has held laws valid which

separated the races on the basis of equal accommodations

in public conveyances, and courts of high authority have

held enactments lawful which provide for separation in the

public schools of white and colored pupils where equal priv

ileges are given. But in view of the rights secured by the

Fourteenth Amendment to the Federal Constitution such

legislation must have its limitations, and cannot be sus

tained where the exercise of authority exceeds the re

straints of the Constitution. We think these limitations are

exceeded in laws and ordinances of the character now be

fore us.

It is the purpose of such enactments, and, it is frankly

avowed it will be their ultimate effect, to require by law,

at least in residential districts, the compulsory separation

of the races on account of color. Such action is said to be

essential to the maintenance of the purity of the races, al

though it is to be noted in the ordinance under consideration

that the employment of colored servants in white families

is permitted, and nearby residences of colored persons not

coming within the blocks, as defined in the ordinance, are

not prohibited.

The case presented does not deal with an attempt to pro-

I hibit the amalgamation of the races. The right which the |

J ordinance annulled was the civil right of a white man to dis

pose of his property if he saw fit to do so to a person of color \

and of a colored person to make such disposition to a white

, person.

It is urged that this proposed segregation will promote

the public peace by preventing race conflicts. Desirable as

this is, and important as is the preservation of the public

19

peace, this aim cannot be accomplished by laws or ordi

nances which deny rights created or protected by the Fed

eral Constitution.

It is said that such acquisitions by colored persons de

preciate property owned in the neighborhood by white per

sons. But property may be acquired by undesirable white

neighbors or put to disagreeable though lawful uses with

like results.

We think this attempt to prevent the alienation of the

property in question to a person of color was not a legiti

mate exercise of the police power of the State, and is in

direct violation of the fundamental law enacted in the Four

teenth Amendment of the Constitution preventing state in

terference with property rights except by due process of

law. That being the case the ordinance cannot stand.

Booth v. Illinois, 184 U. S. 425, 429; Otis v. Parker, 187 U.

S. 606, 609.

Beaching this conclusion it follows that the judgment of

the Kentucky Court of Appeals must be reversed, and the

cause remanded to that court for further proceedings not

inconsistent with this opinion.

Reversed.

w

%

\