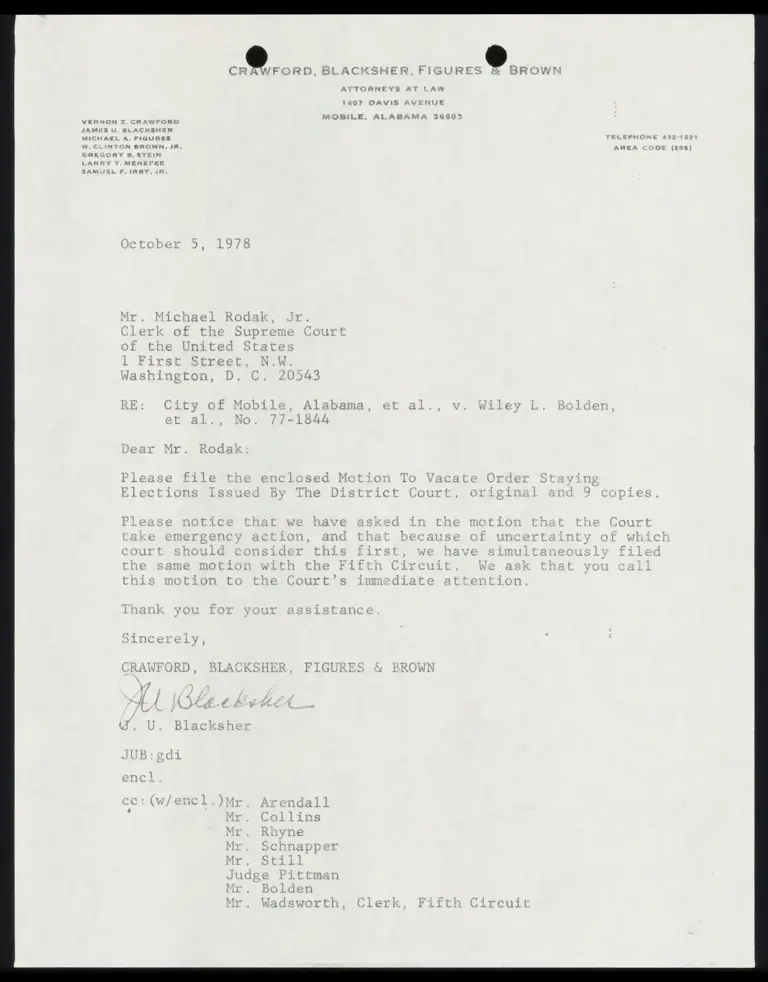

Motion to Vacate Order Staying Elections Issued by the District Court

Public Court Documents

October 5, 1978

16 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Bolden v. Mobile Hardbacks and Appendices. Motion to Vacate Order Staying Elections Issued by the District Court, 1978. 8f09dc73-cdcd-ef11-b8e8-7c1e520b5bae. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/703467e9-fec3-4336-a94e-4d96a7a4422e/motion-to-vacate-order-staying-elections-issued-by-the-district-court. Accessed February 20, 2026.

Copied!

CH AEL i

re i

1691

(20%)

LEPHONE 432 TEL

A

%

nj N

OW

" R

§

i B

{

LAW

YIN

0] Zz >

S

J

4

>

»

¢

‘

pd

—

d

3

3

v

-~

2

H

dwenl

d,

h

e

pt

-

r

7

&

-

i

E

gro

4

di

.

.

;

t

r

.s

5

¥

a

p

A

4

\o’

A

i

i

\

i

!

hy

J

:

pid

P

-

i

oa

i

:

3

{

§

}

—~y

y

f

§

$

i

J

4

;

3

a

r

N

1

|

§

“

E

:

v

mi

N

™

§

{

;

,

.

po

pad

$

r

t

dof

i

i

~

ud

:

)

U

-pe

;

fi

f

Wy

E

d

:

4

_

poss

po

$d

WJ

1

H

1

&

3

:

:

§

§

8}

}

}

{

i

kJ

]

|

FH

H

—

]

a

4

-

-

”

:

4

i

i

5

{

}

i

prod

»

-

ed

~

pd

d

4

I

3

i

!

i

:

13

0

®

ed

$d

bd

te

{

{

p

;

i

H

;

;

\

:

J

|

| |

L

J

-

q

¥

r

1

¥

~t

3

]

¥

TW

i

:

{5

i

}

$

H

{

!

-—

$d

prod

3

{

s

Pied

$

-

}

.

i

v

:

-

l

\

;

¢

:

{

mn

H

rs

i

y

~

>

-

;

ie.

N

-

z

fod

~

p

a

~

PE

r

r

r

{

@®

—

—

’

!

:

[

3

;

H

:

‘

~~

;

;

i

y

ry

4

LJ

i

,

5

rg

ed

{

i)

ed

f

1

pr

i

[

3g

4

a

{

y

poo

A

{

9.

<

proses

i

{

&

oper?

-

{

{

{iL

}

4

-

i

etd

J

2

'

LJ

J

pe?

’

JJ

»

J

2

—

{

4

-

;

.

r

i

wd

}

{=

7)

;

rr

ON

J

"ent

5

u

3

}

e

d

N

J

Ts

"

y

Li

f

y

4

¢

-

a

£

H

3

{

4

:

id

=

-

!

-.

oe)

i

Y

Y

>

§

I

C

¢

;

=

}

or

{

\

’

j

Ra

‘

§

-

{

4

Fond .

~~

pot

if}

RJ

Sf '

y,

v

iy

{13

:

{

2 gon

§

ne |

J} -

5

a

1

—

ed

~~

A

vd

J

{

}

-

Sal

fe

[|

}

i

LS

J 4

u

—

-

8

go

-

-

[3

.

J

4

wd

\t

-

A

pd

“

.

4

-

rend

¢

Soi

4

.

pt

a

rr,

’

>

ged

w

i

ri

I

.

»

po

.

i

.

”

\

—

b

M

Y

|

wt

A

T

-_

A

WF

>

'

-

£

q

i

-

y

~

‘

i

.

wt

pdt

”~

j

-

_

iron

A

.

~

ii

ES

J

qf

id

_

Cted

{

=

-

“ot

v

r

{

{

jt

ai

fo

id

ui

att

~

~~

3

~

J

4

Su

.

>

d

se

y

}

.

,

-

:

"

=

4

-

:

iJ

—

Li.

{.

J

4]

L

d

Sr

rot

by

:

\

i

r

t

§

prod

g

o

e

d

o

t

\

?

-

~t

¥

*y

J

*

]

§

;

\

.

}

J)

“rt

r%

4

¥y)

4

L

d

.

ed

.

7)

per

1

£Y

(J

wd

{

£Y)

v

&

pod

4

N

N

2

C

i”

t

od

J

h

e

d

'.

mermsed

H

e

d

J

{

>

|

J

;

"

oo’

oped

i

‘

-

.

{

(

a

.

’

>

|

:

4.

J

~~

>

3

(

:

i

{

e

d

Pp.

=

"

4

>

H

j

{

44

“

J

-

.

‘ro

pe

i

¢

.

:

ha

H

-

-

4

a

.

;

4

™

)

;

{

g

i

/

_—

<A

.

0

|

J

-

a?

y

X

ab

"

~

-

’

’

a

d

n

¥

F

%

{

i

o-

\

-

rt

TP

|

’

i

»

pe

p

e

P

;

F

.

”

"

pd

e

e

}

[

{

-

3

tr

pred

-

LA

»

Ie

uns

0H

»

5

(a

r=

ipa

;

\

<s

v

foc

/

-

p

1

J

J

f

i

2

fd

=

wed

\

“

od

.

be

\

si gn

AER

o

#3

i

ad

-

w

”

SE]

5

"y

hg

us

{

grmd

»

-

Ly

a

fa

™

J

/

p-—

pond

;

—

-

.

>

-

-

-

_

Y

§

1

3

°

:

he

-

4

i

¥

.

a

4

-

~

‘

i

~

-

fe

hy

i

™

-

N

,

-

i

“

v

4

}

-

-

:

~

A

an

4

"

:

p

wd

3

v

3

*

.

‘

b

d

*

bt

3

J

9

-

ba

od

"

H

A

-

-

{

N

+

~

§

3

o

d

~

.

~

4

¥

'

.

’

.

-

—y

=

»

nes

4

.

A

wi

®

peted

8

et

!

J

ji

’

.

w

)

1]

od

-

.

.

a

'

I.

'

opt

wd

3

go

95)

y

~J

)

4

3

r

>

pm

d

{

§

p

Ad

pod

,

)

J

:

;

Ned

y

J

+

u

y

‘

4

i

i

d

et

’

4

-

y

ps

P

”

q

q

i

”

v

w

w

tJ

\

i.)

.

bd

po

v

p

§

1

w

3

n

d

1

du

h

$

\

#

™

139!

pad

a

a

|

od

"

”

:

.

graph

mot

r

e

c

-

j

|

,

|

)

1

i

J

pond

d

.

/

eed

Lt

“

-

.

r

v

p

.

3

.

il

apd

wm

3}

a}

i

i

+

rr

-

.

-

J

)

)

}

ht

=

\

n

d

i

J

p

l

-

ih

fot

-

-

’

poe

.

~

-

po!

-

v

t

prot

:

p

”

-

*s

sped

Y

a

.

:

}

¢]

b

)

¢

7

h

.

J

4

)

od

|

ed

-

>

I

“pr

y

;

mn

X

3

gros

5)

3

p-

-

nnd

e

| E

E

i

»

pio}

#

y

&

+

=

p

y

;

'

ot

nett!

noduenf

St

>

~

@

=

0

Pe

¢

*

$

8

4

red

b

-

y

ol

rod

“

A

bod

‘

gray

~

N

§

-

id

No?

g

e

o

—

H

{

“

3

P

‘

w

l

-

4

J

h

n

-

v

{

rt

oF

oi

- ge

|

i

i

b-

-

4

—.

i

pm

-

i

?

.

{

n

d

J

ot

}

pedo

§

x

-

’

:

:

w

Agnd

U

l

i

J

01

»

-

—-r

=

{

:

wt

-

¢

1

g

}

¢

}

p

d

:

"

4

of

gent

-

=

v

{

v

forded

3

.

~

ro

-

-

4

x

f

;

r

i

§

¢

.

:

.

3

;

y

w

a

+3

p

e

E

R

R

5

a

Js

noe

2

J

*

ha

4

fai

a

¢

a!

d

4

|

“

t

a

l

-

;

3

Sus

td

}

;

u

ad

|

”

i?

pT.

}

+

4

-

g

phe

pe

nd

i

pod

1

’

-t

|

od

.

-

y

:

*

-

J

of

ed

4

1

dnd

hs?

wt

+

rt

4

i

Re

.

a

-

oN

Ts

pos

>

wd

4

TA

roest

J

td

Us

Nd

bed

43

”

* \/

>

o

i

Ip)

ne.

i

%

-

4

”

7

or

>

5

.

‘

=

rh

{

R

-

fnet

|

.

poe

on

r

»”

\

a

2 y

o

—

—

—4

“

owed

pant

e

d

e

t

opm

om

Wi

® god

pond

J

J

o

)

r

d

r

st

-

vi

4

F-

4

y

o

—

Vie

o

d

of

oo

)

>

}

wy

r

‘

»

49

y

-

L

—

‘

5

—

a

|

{

;

*

”

L

bh

v

:

3

-

N

hed

wd

<

4

9

fo

ot

ord

§

§

|

.

1

§

#4

{

i

{

H

14).

|

-

i

:

i

|

|

|

{

i

|

i

[1

§e=

H

i

i

«pod

g

o

§

i

H

§

}

H

-

i

:

|

i

:

H

§

=

i

i

{

i

-

H

:

i

;

wad

:

}

§

i

i

i

ox

H

i

:

H

—

'

5

:

Po

i

:

»

goed

-

H

§

fo

i

{

i

[3

i}

2

§

i

i

r

i

§

-

}

i

:

i

Hod

i

i

{

i

i

i

§

f

{

!

i

i

i

r

!

i

i

i

H

i

ne

:

5

3

sed

i

H

i

: 1

H

H

z

{GC

a

wn

= pr

(-

<t

o

e

0

= pe

0 -

H

8 HE TY]

i hy

¥

4

X

d

4

Sh

.

>

|

9

Ms

4

J

d

5

4

8

L

d

g

o

o

d

$

e

=

z

sr,

Co

or

ii}

«<7

p

e

-

=

r

a

>

<

i.

WA

og

THY

ek

| 5

kA

o

4

43

N

1) ES

Lada

“

RY

ll Bul Nt

oe

y 3

wd oy

4 »

$ LJ dv

3J

bend

~

~

£3