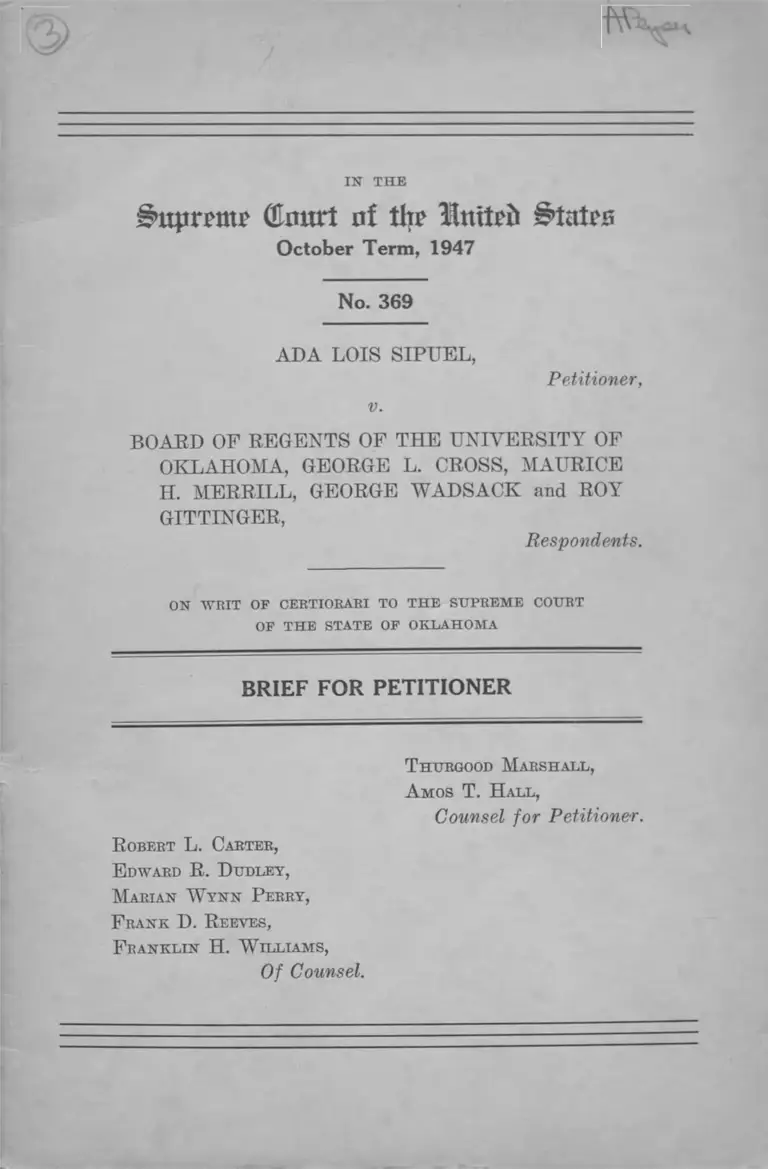

Sipuel v Board of Regents of UOK Brief for Petitioner

Public Court Documents

October 1, 1947

58 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Sipuel v Board of Regents of UOK Brief for Petitioner, 1947. 0a1f1997-c49a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/70b7eb91-08b4-4a6e-becd-54e2da64852f/sipuel-v-board-of-regents-of-uok-brief-for-petitioner. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

IN THE

Supreme dmtrt of thr TUmUb Btntts

October Term, 1947

No. 369

ADA LOIS SIPUEL,

v.

Petitioner,

BOARD OF REGENTS OF THE UNIVERSITY OF

OKLAHOMA, GEORGE L. CROSS, MAURICE

H. MERRILL, GEORGE WADSACK and ROY

GITTINGER,

Respondents.

ON WHIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE SUPREME COURT

OF THE STATE OF OKLAHOMA

BRIEF FOR PETITIONER

T hurgood Marshall,

A mos T. H all,

Counsel for Petitioner.

R obert L. Carter,

E dward R. D udley,

M arian W yn n Perry,

F rank D. R eeves,

F ranklin H. W illiams,

Of Counsel.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PAGE

Opinion of Court Below_____________________________ 1

Jurisdiction_________________________________________ 1

Summary Statement of the Matter Involved_________ 2

1. Statement of the C ase________________________ 2

2. Statement of F acts___________________________ 4

Assignment of Errors ______________________________ 7

Question Presented__________________________________ 7

Outline of Argument _______________ 8

Summary of Argument _____________________________ 9

Ai-gument _______________________________________ 10

I— The Supreme Court of Oklahoma Erred in Not

Ordering the Lower Court to Issue a Writ Requir

ing the Respondents to Admit Petitioner to the

Only Existing Law School Maintained by the

State __________________________________________ 10

II— This Court Should Re-Examine the Constitution

ality of the Doctrine of “ Separate But Equal”

Facilities ___________ 18

A. Reference to This Doctrine in the Gaines Case

Has Been Relied on by State Courts to Render

the Decision Meaningless____________________ 18

B. The Doctrine of “ Separate But Equal” Is

Without Legal Foundation __________________ 27

C. Equality Under a Segregated System Is a

Legal Fiction and a Judicial Myth.-_________ 36

1. The General Inequities in Public Educa

tional Systems Where Segregation is Re

quired ________________________ 37

11

PAGE

2. On the Professional School Level the In

equities Are Even More Glaring_________ 40

D. There is No Rational Justification For Segre

gation in Professional Education and Dis

crimination Is a Necessary Consequence of

Any Separation of Professional Students On

the Basis of Color___________________________ 45

III— The Doctrine of “ Separate But Equal” Facilities

Should Not Be Applied to This Case___________ 51

Conclusion__________________________________________ 52

Table of Cases

'-^Bluford v. Canada, 32 F. Supp. 707 (1940) (appeal dis

missed 8 Cir. 119 F. (2d) 779)_____________________ 23

Cantwell v. Connecticut, 310 U. S. 296________________ 51

^Cummings v. Board of Education, 175 U. S. 528_______ 35

G-Gong Lum v. Rice, 275 U. S. 78_______________________ 35

Hirabayashi v. U. S., 320 U. S. 81____________________33, 52

'-Marsh v. Alabama, 326 U. S. 501______________________ 51

(✓ Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 U. S. 337 reh.

den. 305 U. S. 676_________________________ 11,18, 20, 21

(✓ Morgan v. Virginia, 328 U. S. 373____________________28, 51

Vpearson v. Murray, 169 Md. 478, 182 Atl. 590 (1936)___ 19

VPlessy v. Ferguson, 163 U. S. 537_______________ _____ 31

'-'Railway Mail Association v. Corsi, 326 U. S. 88________ 51

Roberts v. City of Boston, 5 Cush. 198 (1849)_________ 32

vState ex rel. Bluford v. Canada, 348 Mo. 298, 153 S. W.

(2d) 12 (1941)____________________________________ 24

CState ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 344 Mo. 1238, 131 S. W.

(2d) 217 (1939)___________________________________ 22

v State ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 342 Mo. 121, 113 S. W.

. (2d) 783 (1937) _________________________________14,16

State ex rel. Michael v. Whitliam, 179 Tenn. 250, 165 S.

W. (2d) 378 (1942)________________________________ 25

Steele v. L. N. R. R. Co., 323 U. S. 192 _____ ___________ 34

yStrauder v. West Virginia, 100 U. S. 303-------------------- 28, 30

I l l

Authorities Cited

PAGE

American Teachers Association, The Black and White

of Rejections for Military Service (Aug. 1944)__ 39,48

Biennial Surveys of Education in the United States,

Statistics of State School Systems, 1939-40 and

1941-42 (1944) ___________________________________ 38

Blose, David T. and Ambrose Caliver, Statistics of the

Education of Negroes (A Decade of Progress),

Federal Security Agency, IT. S. Office of Education,

1942_____________________________________________ 38

Cantril, H., Psychology of Social Movements (1941).... 47

Clark, W. W., “ Los Angeles Negro Children,” Educa

tional Research Bulletin (Los Angeles, 1923)_____ 48

Dodson, Dan W., “ Religious Prejudices in Colleges” ,

The American Mercury (July 1946)______________ 43

Klineberg, Otto, Race Differences (1935)__________ 48

Klineberg, Otto, Negro Intelligence and Selectice Mi

gration (New York, 1935)____________________ 48

McGovney, D. 0., “ Racial Residential Segregation by

State Court Enforcement of Restrictive Agree

ments, Covenants or Conditions in Deeds is Uncon

stitutional,” 33 Cal. L. Rev. 5 (1945)____________ 49

McWilliams, Carey, “ Race Discrimination and the

Law” , Science and Society, Volume IX, No. 1, 1945 46

Myrdal, Gunnar, An American Dilemma (New York,

1944)--------------------------------- -------------------------------- 29, 46

National Survey of Higher Education for Negroes, Vol.

II, U. S. Office of Education, Washington, 1942._ . 42

Peterson, J. & Lanier, L. H., “ Studies in the Compara

tive Ability of Whites and Negroes,” Mental Mea

surement Monograph, 1929__________________ ____ 48

IV

PAGE

Report of the President’s Committee on Civil Rights,

“ To Secure These Rights,” Government Printing

Office, Washington, 1947----------------- ---- ----------------46,51

Report of the President’s Commission on Higher Edu

cation, “ Higher Education for American Democ

racy” , Vol. I, Government Printing Office, Washing

ton, 1947 ______________________________________ 39, 50

Sixteenth Census of the United States: Population,

Vol. m , Part 4 (1940)___________________________ 40

Thompson, Charles H., “ Some Critical Aspects of the

Problem of the Higher and Professional Education

for Negroes,” Journal of Negro Education (Fall,

1945).____________________________________________ 40

Warner, Lloyd W., New Haven Negroes (New Haven,

1940)____________________________________________ 49

Weltfish, Gene, “ Causes of Group Antagonism” , Vol. I,

Journal of Social Issues_________________________ 47

Statutes Cited

M issouri

Revised Statutes 1929, Section 9618____ 15,16, 21, 23, 24

Oklahoma

Constitution, Article XIII-A, Section 2....— .... ... .15,16

Statutes, Sec. 1451B---------------------------------------------15,16

T ennessee

Chapter 43, Public Acts of 1941------------------------------ 25

IN TH E

Ihtpreme (knurl of llir Stutrli i>tatrn

October T erm, 1947

No. 369

A da L ois S ipuel,

Petitioner,

v.

Board of R egents of the U niversity of

Oklahoma, George L. Cross, M aurice

H. M errill, George W adsack and R oy

Gittinger,

Respondents.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE SUPREME COURT OF THE

STATE OF OKLAHOMA

BRIEF FOR PETITIONER

Opinion of Court Below

The opinion of the Supreme Court of Oklahoma appears

in the record filed in this cause (R. 35-51) and is reported

a t ____Okla______ , 180 P. (2d) 135.

Jurisdiction

Jurisdiction of this Court is invoked under Section 237b

of the Judicial Code (28 U. S. C. 344b) as amended February

13, 1925.

2

The Supreme Court of Oklahoma issued its judgment in

this case on April 29, 1947 (R. 51). Petition for rehearing

was appropriately filed and was denied on June 24, 1947

(R. 61). Petition for Certiorari was filed on September 20,

1947, and was granted by this Court on November 10, 1947.

SUMMARY STATEMENT OF THE MATTER INVOLVED

1. Statement of the Case

Petitioner is a citizen and resident of the State of Okla

homa. She desires to study law and to prepare herself for

the legal profession. Pursuant to this aim, she applied for

admission to the first-year class of the School of Law of the

University of Oklahoma, a public institution maintained

and supported out of public funds and the only public insti

tution in the state offering facilities for a legal education.

She was denied admission. Her qualifications for admission

to this institution are undenied, and it is admitted that peti

tioner, except for the fact that she is a Negro, would have

been accepted as a first-year student in the School of Law

of the University of Oklahoma, which is the only state insti

tution offering instruction in law.

Upon being refused admission solely on account of her

race and color, petitioner applied to the District Court of

Cleveland County, Oklahoma, for a writ of mandamus

against the Board of Regents of the University of Okla

homa; George L. Cross, President; Maurice H. Merrill,

Dean of the Law School; Roy Gittinger, Dean of Admis

sions; and George Wadsack, Registrar, to compel her ad

mission to the first-year class of the School of Law on the

same terms and conditions afforded white applicants seek

ing to matriculate therein (R. 2). The writ was denied

3

(R. 21) and on appeal this judgment was affirmed by the

Supreme Court of the State of Oklahoma on April 29, 1947

(R. 51). Petitioner duly entered a motion for a rehearing

(R. 54) which was denied on June 24, 1947 (R. 61), where

upon petitioner now seeks in this Court a review and re

versal of the judgment below.

The action of respondents in refusing to admit peti

tioner to the School of Law was predicated upon the

grounds that: (1) such admission was contrary to the con

stitution, law and public policy of the state; (2) that

scholarship aid was offered by the state to Negroes to study

law outside of the state; and, (3) that no demand had been

made upon the Board of Regents of Higher Education to

provide such legal training at Langston University, the

state institution affording college and agricultural training

to Negroes in the state.

The Supreme Court of Oklahoma held that:

“ We conclude that petitioner is fully entitled to

education in law with facilities equal to those for

white students, but that the separate education policy

of Oklahoma is lawful and is not intended to be dis

criminatory in fact, and is not discriminatory against

plaintiff in law for the reasons above shown.

“ We conclude further that as the laws in Okla

homa now stand this petitioner had rights in addi

tion to those available to white students in that she

had the right to go out of the state to the school of

her choice with tuition aid from the state, or if she

preferred she might attend a separate law school for

Negroes in Oklahoma.

“ We conclude further that while petitioner may

exercise here preference between those two educa-

4

tional plans, she must indicate that preference by

demand or in some manner that may be depended

upon, and we conclude that such requirement for no

tice or demand on her part is no undue burden upon

her.

“ We conclude that up to this time petitioner has

shown no right whatever to enter the Oklahoma Uni

versity Law School, and that such right does not exist

for the reasons heretofore stated” (R. 51).

In this Court petitioner reasserts her claim that the re

fusal to admit her to the University of Oklahoma solely be

cause of race and color amounts to a denial of the equal

pretection of the laws guaranteed under the Fourteenth

Amendment to the Federal Constitution in that the state is

affording legal facilities for whites while denying such fa

cilities to Negroes.

2. Statement of Facts

The facts in issue are uncontroverted and have been

agreed to by both petitioner and respondents (R. 22-25).

The following are the stipulated facts:

The petitioner is a resident and citizen of the United

States and of the State of Oklahoma, County of Grady and

City of Chicakasha, and desires to study law in the School

of Law in the University of Oklahoma for the purpose of

preparing herself to practice law in the State of Oklahoma

(R. 22).

The School of Law in the University of Oklahoma is the

only law school in the state maintained by the state and

5

under its control (R. 22). The Board of Regents of the

University of Oklahoma is an administrative agency of the

state and exercises over-all authority with reference to the

regulation of instruction and admission of students in the

University of Oklahoma. The University is a part of the

educational system of the state and is maintained by appro

priations from public funds raised by taxation from the citi

zens and taxpayers of the State of Oklahoma (R. 22-23).

The School of Law of the University of Oklahoma spe

cializes in law and procedure which regulate the govern

ment and courts of justice in Oklahoma, and there is no

other law school maintained by public funds of the state

where the petitioner can study Oklahoma law and pro

cedure. The petitioner will be placed at a distinct disad

vantage at the Bar of Oklahoma and in the public service

of the aforesaid state with respect to persons who have

had the benefit of unique preparation in Oklahoma law and

procedure offered at the School of Law of the University

of Oklahoma unless she is permitted to attend the aforesaid

institution (R. 23).

The petitioner has completed the full college course at

Langston University, a college maintained and operated by

the State of Oklahoma for the higher education of its Negro

citizens (R. 23).

The petitioner made due and timely application for ad

mission to the first-year class of the School of Law of the

University of Oklahoma on January 14,1946, for the semes

ter beginning January 15, 1946, and then possessed and

still possesses all the scholastic and moral qualifications re

quired for such admission (R. 23).

On January 14, 1946, when petitioner applied for admis

sion to the said School of Law, she complied with all of the

6

rules and regulations entitling her to admission by filing

with the proper officials of the University an official tran

script of her scholastic record. The transcript was duly

examined and inspected by the President, Dean of Admis

sions, and Registrar of the University (all respondents

herein) and was found to be an official transcript entitling

her to admission to the School of Law of the said University

(R. 23).

Under the public policy of the State of Oklahoma, as

evidenced by constitutional and statutory provisions re

ferred to in the answer of respondents herein, petitioner

was denied admission to the School of Law of the Uni

versity of Oklahoma solely because of her race and color

(R, 23-24).

The petitioner, at the time she applied for admission to

the said School of Law of the University of Oklahoma, was

and is now ready and willing to pay all of the lawful

charges, fees and tuitions required by the rules and regula

tions of the said university (R. 24).

Petitioner had not applied to the Board of Regents of

Higher Education to prescribe a school of law similar to

the School of Law of the University of Oklahoma as a part

of the standards of higher education of Langston Uni

versity and as one of the courses of study thereof (R. 24).

It was further stipulated between the parties that after

the filing of this case, the Board of Regents of Higher Edu

cation: (1) had notice that this case was pending; and, (2)

met and considered the questions involved herein; and, (3)

had no unallocated funds on hand or under its control at the

time with which to open up and operate a law school and

has since made no allocations for such a purpose (R. 24-25).

7

Assignment of Errors

The Supreme Court of Oklahoma erred:

(1) In holding that the separate education policy of Okla

homa is lawful and is not intended to be discriminatory

in fact, and is not discriminatory against plaintiff in

law for the reasons above shown.

(2) In holding that as the laws in Oklahoma now stand this

petitioner had rights in addition to those available to

white students in that she had the right to go out of

the state to the school of her choice with tuition aid

from the state, or if she preferred she might attend a

separate law school for Negroes in Oklahoma.

(3) In holding that while petitioner may exercise her

preference between those tw7o educational plans, she

must indicate that preference by demand or in some

manner that may be depended upon, and that such re

quirement for notice or demand on her part is no undue

burden upon her.

(4) In holding that petitioner has shown no right whatever

to enter the Oklahoma University Law School, and that

such right does not exist for the reasons heretofore

stated.

(5) In affirming the judgment of the trial court.

Question Presented

The Petition for Certiorari in the instant case presented

the following question:

Does the Constitution of the United States Prohibit

the Exclusion of a Qualified Negro Applicant Solely

Because of Race from Attending the Only Law School

Maintained By a State?

8

OUTLINE OF ARGUMENT

I

The Supreme Court of Oklahoma erred in not ordering

the lower court to issue a writ requiring the respon

dents to admit petitioner to the only existing law

school maintained by the state.

II

This Court should re-examine the constitutionality of

the doctrine of “ separate but equal” facilities.

A. Reference to this doctrine in the Gaines case has

been relied on by state courts to render the decision

meaningless.

B. The doctrine of “separate but equal” facilities is

without legal foundation.

C. Equality under a segregated system is a legal fiction

and a judicial myth.

1. The general inequities in public educational sys

tems where segregation is required.

2. On the professional school level the inequities are

even more glaring.

D. There is no rational justification for segregation in

professional education and discrimination is a neces

sary consequence of any separation of professional

students on the basis of color.

III

The doctrine of “ separate but equal” facilities should

not be applied to this case.

9

Summary of Argument

Petitioner here is asserting a constitutional right to a

legal education on par with other persons in Oklahoma.

This right can be protected only by petitioner’s admission

to tlie law school of the University of Oklahoma, the only

existing facility maintained by the state. Petitioner, there

fore, sought a mandatory writ requiring her admission to

the University of Oklahoma. The state courts have refused

to grant the relief sought principally because of statutes

requiring the separation of the races in the state’s school

system. Petitioner contends that the questions presented

in this appeal were settled by this Court in Missouri ex rel.

Gaines v. Canada and that her case both as to facts and law

comes within the framework of the Gaines case.

Petitioner, however, is forced to raise anew the issue

considered settled by that decision chiefly because the opin

ion in the Gaines case was amenable to an interpretation

that this Court admitted the right of a state to maintain

a segregated school system under the equal but separate

theory even where, as here, no provision other than the

existing facility which is closed to Negroes is available to

petitioner. Reference to this doctrine has not only be

clouded the real issues in cases of this sort but in fact bas

served to nullify petitioner’s admitted rights.

Petitioner is entitled to admission now to the University

of Oklahoma and her right to redress cannot be conditioned

upon any prior demand that the state set up a separate

facility. The opinion in Gaines case is without meaning

unless this Court intended that decision to enforce the right

of a qualified Negro applicant in a case such as here to

admission instanter to the only existing state facility. The

10

equal but separate doctrine has no application in cases of

this type. The Gaines decision must have meant at least

this and should be so clarified. Beyond that petitioner con

tends that the separate but equal doctrine is basicly unsound

and unrealistic and in the light of the history of its applica

tion should now be repudiated.

ARGUM ENT

I

The Supreme Court of Oklahoma Erred in Not Order

ing the Lower Court to Issue a W rit Requiring the

Respondents to Admit Petitioner to the Only Exist

ing Law School Maintained by the State.

Petitioner’s constitutional right to a legal education

arose at the time she made application, as a qualified citizen,

for admission into the state law school. This privilege ex

tends to all qualified citizens of Oklahoma and the denial

thereof to this petitioner constitutes a violation of the Four

teenth Amendment to the United States Constitution. That /

the action of respondents, constituting the Board of Regents

of the University of Oklahoma, must be regarded as state

action has conclusively been established in a long line of

decisions by this Court, and is not in issue in this case.

It is admitted that: (1) petitioner was qualified to enter

the law school at the time application was made; that she

was qualified at the time this case was tried and is now

qualified; (2) the law school at the University of Oklahoma

is the only existing facility maintained by the state for the

instruction of law; (3) petitioner has been denied admission

to the University law school solely because of race and color;

(4) respondents herein are state officials. There is no ques

tion but that if petitioner were not a Negro she would have

been admitted to the University of Oklahoma Law School.

11

That petitioner had a clear right under these facts to

have the writ issued requiring these respondents to admit

her into the State law school was expressly established by

this Court in Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada}

The Supreme Court of Oklahoma in affirming the lower

court’s denial of the writ relied upon (1) the segregation

laws of the state requiring separate educational facilities

for white and Negro citizens; and, (2) that as a result of

these segregation statutes a duty was placed upon the peti

tioner to make a “ demand” for the establishment of a sepa

rate law school at some time in the future before applying

to the University Law School. This new duty as a con

dition precedent to the exercise of her right to a legal edu

cation is placed upon petitioner solely because of the segre

gation statutes of Oklahoma.

The writ was not issued and petitioner has not been ad

mitted to the only existing law school because the Supreme

Court of Oklahoma committed error in not following the

Gaines case, but adopting just the opposite point of view

which has deprived petitioner of her constitutional right not

to be discriminated against because of race and color. Under

the facts in this case the writ should have been issued.

In the Gaines case, petitioner (1) was qualified to seek

admission into the state law school in Missouri; (2) the

law school at Missouri was the only law school maintained

by the State for the instruction of law; (3) Gaines was de

nied admission to the law school solely on account of race

and color; and, (4) respondents in the Gaines case were

state officers. There, this Court held that, despite the find

ing of the Supreme Court of Missouri that a policy of segre

gation in education existed in the State, a provision for

out-of-state aid for Negro students did not satisfy the Four- 1

1 305 U. S. 337 (rehearing denied 305 U. S. 676).

12

teenth Amendment and Gaines was declared entitled to be

admitted into the state law school “ in the absence of other

and proper provisions for his legal training within the

state.” This Court recognized the fact that no prior de

mand had been made upon the Curators of Lincoln Uni

versity to set up a separate law school for Negroes.2

The Oklahoma Supreme Court erroneously relies upon

the Gaines case for the proposition that “ the authority of a

State to maintain separate schools seems to be universally

recognized by legal authorities” (E. 39). Mr. Chief Justice

H ughes adequately answered this argument as follows:

‘ ‘ The admissibility of laws separating races in the

enjoyment of privileges afforded by the state rests

wholly upon the quality of privileges which the laws

give to separated groups within the state.” 3

The Oklahoma Supreme Court held that the segregation

laws of the State prevent petitioner from entering the only

state law school:

“ It seems clear to us that since our State policy

of separate education is lawful, the petitioner may

not enter the University Law School maintained for

white pupils” (B. 44).

The court concluded that this separation policy is not dis

criminatory against petitioner (E. 51). The reasons ad

vanced for this conclusion have been adequately met in the

Gaines case and disposed of favorably to petitioner herein.

In seeking to justify the policy of segregation, which

provides no law training for Negroes within the State, the

Oklahoma Supreme Court also relies upon out-of-state

2 305 U. S. 337, 352.

3 Ibid., at p. 349.

13

scholarship aid—a point completely dcliors the record in

this case. The court stated:

“ If a white student desires education in law at an

older law school outside the State, he must fully pay

his own way while a Negro student from Oklahoma

might be attending the same or another law school

outside the State, but at the expense of this State.

“ It is a matter of common knowledge that many

white students in Oklahoma prefer to and do receive

their law training outside the State at their own ex

pense in preference to attending the University law

school. Perhaps some among those now attending the

University Law School would have a like preference

for an older though out-of-state school but for the

extra cost to them.

“ Upon consideration of all facts and circum

stances it might well be, at least in some cases, that

the Negro pupil who receives education outside the

state at state expense is favored over his neighbor

white pupil rather than discriminated against in that

particular” (R. 43).

On this point the Gaines case is clear:

“ We think that these matters are beside the point.

The basic consideration is not as to what sort of

opportunities other states provide, or whether they

are as good as those in Missouri, but as to what

opportunities Missouri itself furnishes to white stud

ents and denies to Negroes solely upon the ground of

color.” 4

Under the facts in this case such a policy applied to peti

tioner is unconstitutional and the suggested substitutes of

requiring her to elect either out-of-state aid, or demand that

a new institution be erected for her, are inadequate to meet

the requirements of equal protection of the law. This addi

tional duty of requiring petitioner to make a demand upon

4 305 U. S. 337, 349.

14

the Board of Higher Education of Oklahoma to establish a

separate law school before being able to successfully assert

a denial by the state of her right to a legal education comes

by virtue of the segregation statutes of Oklahoma. Clearly

this duty devolves only upon Negroes and not upon white

persons and is in itself discriminatory.

There is a striking similarity between the decisions of

the state courts in the Gaines case and this case on the

question of the petitioner’s alleged duty to make a “ de

mand” for a separate law school as a condition precedent

to application to the existing law school.

In the Gaines case, the Supreme Court of Missouri

stated: “ Appellant made no attempt to avail himself of

the opportunities afforded the Negro people of the State

for higher education. He at no time applied to the manage

ment of the Lincoln University for legal training.” 5

In the decision of the Oklahoma Supreme Court in this

case, the court stated:

“ Here petitioner Sipuel apparently made no ef

fort to seek in law in a separate school” (R. 47).

A further similarity exists in the statutes of the two

states, neither of which could reasonably be interpreted to

place a mandatory duty upon the governing body to supply

facilities for a legal education to Negro students within the

state although the Supreme Court of Oklahoma declared

that had petitioner applied for such legal education, “ it

would have been their duty to provide for her an oppor

5 113 S. W . 2d 783, 789 (1937). In the face of this clear statement

of the facts by the Missouri Court in the Gaines case, the Oklahoma

court stated that the facts were completely contrary: “ Thus, in Mis

souri, there was application for and denial of that which could have

been lawfully furnished, that is, law education in a separate school

. . . ” (R . 45).

15

tunity for education in law at Langston or elsewhere in

Oklahoma” (R. 45). In the Gaines case, the statute (Sec

tion 9618, Missouri Revised Statute 1929) provides that the

Board of Curators of Lincoln University were required so

to reorganize that institution as to afford for Negroes

“ training up to the standard furnished by the state uni

versity of Missouri whenever necessary and practicable in

their opinion.” This Court interpreted that statute as

not placing a mandatory duty upon the Missouri officials.

In Oklahoma, the 1945 amendments provided, in Section

1451 B, that the Board of Regents of Oklahoma Agricul

tural and Mechanical College should control Langston Uni

versity and should “ do any and all things necessary to make

the university effective as an educational institution for

Negroes of the State.”

In addition, the Oklahoma Constitution, Article XIII-A,

section 2, provides in part:

“ The Regents shall constitute a co-ordinating

board of control for all State institutions described

in section 1 hereof, with the following specific

powers: (1) it shall prescribe standards of higher

education applicable to each institution; (2) it shall

determine the function and courses of study in each

of the institutions to conform to the standards pre

scribed; . . . ”

These vague provisions, lacking even the comparison

with the standards of the “ white” university which were

present in the Missouri statute, were construed by the state

court as placing a mandatory duty upon the Board of

Regents to provide education in law for petitioner within

the State of Oklahoma. Such a duty was not found by the

16

court to come directly from the statute but to flow from

the requirement of the segregation policy of the state itself.

The Supreme Court of Oklahoma in construing its stat

utes concerning higher education held that these statutes

placed a mandatory duty upon the State Regents for Higher

Education to establish a Negro law school upon demand:

“ When we realize that and consider the pro

visions of our State Constitution and Statutes as to

education, we are convinced that it is the mandatory

duty of the State Regents for Higher Education to

provide equal educational facilities for the races to

the full extent that the same is necessary for the

patronage thereof. That board has full power, and

as we construe the law, the mandatory duty to pro

vide a separate law school for Negroes upon demand

or substantial notice as to patronage therefor.”

(Italics ours—R. 50.)

The Supreme Court of Missouri in construing its stat

utes as to higher education for Negroes concluded that:

“ In Missouri the situation is exactly opposite (to

Maryland). Section 9618 R. S. 1929 authorizes and

requires the board of curators of Lincoln University

‘ to reorganize said institution so that it shall afford

to the Negro people of the state opportunity for

training up to the standard furnished at the state

university of Missouri whenever necessary and prac

ticable in their opinion.’ This statute makes it the

mandatory duty of the board of curators to estab

lish a law school in Lincoln University ivhenever nec

essary or practical.” (Italics ours— 113 S. W. 2d

783, 791.)

This Court in passing upon the construction of the Supreme

Court of Missouri of its statutes stated:

“ The state court quoted the language of Section

9618, Mo. Rev. Stat. 1929, set forth in the margin,

17

making it the mandatory duty of the board of cura

tors to establish a law school in Lincoln University

‘ whenever necessary and practicable in their opin

ion.’ This qualification of their duty, explicitly

stated in the statute, manifestly leaves it to the judg

ment of the curators to decide when it will be neces

sary and practicable to establish a law school, and

the state court so construed the statute” (305 U. S.

337, 346-347).

Further evidence that the Supreme Court of Oklahoma

completely ignored the opinion of this Court in the Gaines

case appears from the misstatement of fact that Gaines

actually applied for admission to a separate Negro school

in Missouri where there was no law school in existence. On

this point the Oklahoma Supreme Court stated:

“ The opinion does not disclose the exact nature

of his (Gaines) communication or application to

Lincoln University, but since Gaines was following

through on his application for and his efforts to ob

tain law school instruction in Missouri, we assume

he applied to Lincoln University for instruction

there in the law.” (Italics ours—R. 44.)

“ This he did when he made application to Lin

coln University as above observed, but this petitioner

Sipuel wholly failed to do” (R, 46).

“ Apparently petitioner Gaines in Missouri was

seeking first that to which he was entitled under the

laws of Missouri, that is education in law in a sepa

rate school” (R. 47).

The actual facts, as this Court indicated in its opinion in

the Gaines case, are that Gaines only applied to the Uni

versity Law School maintained by the State. The record

in the Gaines case clarifies this point:

“ Q. Now you never at any time made an applica

tion to Lincoln University or its curators or its offi

18

cers or any representative for any of the rights,

whatever, given you by the 1921 statute, namely,

either to receive a legal education at a school to be

established in Lincoln University or, pending that,

to receive a legal education in a school of law in a

state university in an adjacent state to Missouri, and

Missouri paying that tuition,—you never made ap

plication for any of those rights, did you? A. No

sir.” 6

Mr. Chief Justice H ughes in the Gaines opinion quite cor

rectly states the facts:

“ In the instant case, the state court did note that

petitioner had not applied to the management of

Lincoln University for legal training.” 7

The Supreme Court of Oklahoma has shown no valid

distinction between this case and the Gaines case. Their

efforts to distinguish the two cases are shallow and without

merit. In refusing to grant the relief prayed for in this

case the State of Oklahoma has demonstrated the inevitable

result of the enforcement of the doctrine of “ separate but

equal” facilities, viz, to enforce the policy of segregation

without any pretext of giving equality.

II

This Court Should Re-Examine the Constitutionality of

the Doctrine of “Separate But Equal” Facilities.

A. Reference to This Doctrine in the Gaines Case Has

Been Relied on by State Courts to Render the Deci

sion Meaningless.

Petitioner herein is seeking a legal education on the

same basis as other students possessing the same qualifi

6 Transcript of Record Gaines v. Canada, et al. No. 57, October

Term, 1938, p. 85.

7 Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 U. S. 337, 352.

19

cations. The State of Oklahoma in offering a legal educa

tion to qualified applicants is prohibited by the Fourteenth

Amendment from denying these facilities to petitioner

solely because of her race or color. Although the Four

teenth Amendment is a prohibition against the denial to

petitioner of this right, it is at the same time an affirmative

protection of her right to be treated as all other similarly

qualified applicants without regard to her race or color.

Respondents rely upon Oklahoma’s segregation statutes

as grounds for the denial of petitioner’s rights. In order

to bolster their defense, they seek to place upon petitioner

the duty of taking steps to have established a separate law

school at an indefinite time and at an unspecified place

without any guarantee whatsoever as to equality in either

the quantity or quality of these theoretical facilities.

The “ separate but equal” doctrine, based upon the as

sumption that equality is possible within a segregated sys

tem, has been used as the basis for the enforcement of the

policy of segregation in public schools. The full extent of

the evil inherent in this premise is present in this case

where the “ separate but equal” doctrine is urged as a com

plete defense where the state has not even made the pretense

of establishing a separate law school.

In the first reported case on the right of a qualified

Negro applicant to be admitted to the only existing law

school maintained by the state, the Court of Appeals of

Maryland, in the face of a state policy of segregation, de

cided that the Fourteenth Amendment entitled the Negro

applicant to admission to the only facility maintained:

“ Compliance with the Constitution cannot be de

ferred at the will of the state. Whatever system it

adopts for legal education now must furnish equality

of treatment now.” 8

8 Pearson v. Murray, 169 Md. 478, 182 A. 590 (1936).

20

The second case involving this point reached this Court

on a petition for a writ of certiorari to the Supreme Court

of Missouri.9 The facts in the Gaines case were similar to

those in the Pearson case except that there was no statu

tory authorization for the establishment of a separate law

school for Negroes in Maryland, whereas the State of Mis

souri contended that there was statutory authorization for

the establishment of a separate law school with a provision

for out-of-state scholarships during the interim.

This Court, in reversing the decision of the Supreme

Court of Missouri (which affirmed the lower court’s judg

ment refusing to issue the writ of mandamus), held that

the offering of out-of-state scholarships pending possible

establishment of a Negro law school in the future within

the state, did not constitute equal educational opportunities

within the meaning of the Fourteenth Amendment. Mr.

Chief Justice H ughes, in the majority opinion held: “ that

petitioner was entitled to be admitted to the law school of

the State University in the absence of other and proper

provision for his legal training within the State. ” 0a This

issue, as framed by the Court, made unnecessary to its

decision any holding as to what the decision might be if

the state had been offering petitioner opportunity for a

legal education in a Negro law school then in existence in

the state.

At the time of its rendition, the Gaines decision was

considered a complete vindication of the right of Negroes to

admission to the only existing facility afforded by the state,

even in the face of a state policy and practice of segrega

tion. This decision, in fact, was considered as being at

least as broad and as far reaching as Pearson v. Murray,

9 Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 U. S. 337.

9a 305 U. S. 337, 352.

21

supra. This apparently was the intent and understanding

of the Court itself, for Mr. Justice M cR eynolds, in a sepa

rate opinion, construed the opinion as meaning that either

the state could discontinue affording legal training to whites

at the University of Missouri, or it must admit petitioner

to the only existing law school.

The Court’s reference to the validity of segregation 10

laws and its discussion of whether or not there wTas a man

datory duty upon the Board of the Negro College in Mis

souri to establish the facilities demanded in a separate

school, however, has created unfortunate results. Because of

this language, courts in subsequent cases, while purporting

to follow the Gaines decision, have in reality so interpreted

this decision as to withhold the protection which that case

intended.

When the Gaines case was remanded to the state court

after decision here, the Missouri Supreme Court, in quot

ing from this Court’s opinion, placed great reliance upon

that portion of the opinion which said:

“ We are of the opinion that the ruling was error,

and that petitioner was entitled to be admitted to the

law school of the State University in the absence of

other and proper provision for his legal training

within the S ta te”

By then, Section 9618 of the Missouri Statutes Annotated

had been repealed and reenacted and was construed as

placing a mandatory duty upon the Board of Curators of

the Lincoln University (the Negro college) to establish a

law school for Negroes. The court concluded that the issu

10 “ The State has sought to fulfill that obligation by furnishing equal

facilities in separate schools, a method the validity of which has been

sustained by our decisions.” Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada 305

U. S. 337, 344.

22

ance of the writ would be denied if, by the time the case was

again tried, the facilities at Lincoln University were equiva

lent to those of the University of Missouri and gave the

state until the following September to establish such facili

ties. If they were not equivalent, the writ would be granted.

Said the court:

“ We are unwilling to undertake to determine con

stitutional adequacy of the provision now made for

relator’s legal education within the borders of the

state by the expedient of coupling judicial notice with

a presumption of law . . . ” (131 S. W. 2d 217,

219-220.)

Hence, the Missouri Supreme Court in the second Gaines

case construed the opinion of this Court as not requiring

the admission of the petitioner to the existing law school

but as giving to the State of Missouri at that late date the

alternative of setting up a separate law school in the future.

In the event the state exercised that option, petitioner would

have the right to come into court and test the equality of

the provisions provided for him as compared with those

available at the University of Missouri. If no facilities

were available or those available were unequal, he would

then be entitled to admission to the University of Missouri

law school.

Petitioner filed his application for writ of mandamus

in the Gaines case in 1936. The case reached this Court in

1938. It was then returned to the Supreme Court of Mis

souri, and a decision rendered in August 1939. Thereafter,

the state was given an additional several months to set up

a law school. Then, petitioner would be entitled to come in

again and test the equality of the provisions. Presumably,

therefore, by 1941, four years after he asserted his right

to admission to the Law School of the University of Mis

23

souri, petitioner might get some redress. During this

period of time, white students in the class to which he be

longed would have graduated from law school and would

have been a year or perhaps more in the actual practice of

law.

Shortly after the Gaines case, another suit was started

by a Negro based upon the refusal of the registrar of the

University of Missouri to admit her to the School of

Journalism, it being the only existing facility within the

state offering a course in journalism. Suit was brought

in the U. S. District Court seeking damages and was dis

missed. The District Court adopted the construction of

Section 9618 of Missouri Statutes Annotated, which the

State Supreme Court had followed in the second Gaines

decision, and it found that the statute placed a mandatory

duty on the Board of Curators of Lincoln University to

set up a School of Journalism for Negroes upon proper

demand.

In answering plaintiff’s contention that the rights she

asserted had been upheld by this Court in the Gaines case,

the District Court said:

“ . . . While this court is not bound by the State

court’s construction of the opinion of the Supreme

Court, much respect is due the former court’s opinion

that the Gaines case did not deprive the State of

a reasonable opportunity to provide facilities, de

manded for the first time, before it abrogated its

established policy of segregation.” 11

And in dismissing the case, it stated the following as what

it felt her rights to be under the holding of this Court in the

Gaines case:

“ Since the State has made provision for equal

educational facilities for Negroes and has placed the

11 Bluford v. Canada, 32 F. Supp. 707, 710 (1940).

24

mandatory duty upon designated authorities to pro

vide those facilities, plaintiff may not complain that

defendant has deprived her of her constitutional

rights until she has applied to the proper authorities

for those rights and has been unlawfully refused.

She may not anticipate such refusal.” 12

Thus, the District Court construed the Gaines case as

requiring a petitioner to apply to the board of the Negro

college where a statutory duty was placed upon them to

provide the training desired and await their refusal before

he could assert any denial of equal protection, even in the

face of the patent fact that there was only one facility in

existence at the time of application which was maintained

exclusively for whites.

The next case was State ex rel. Bluford v. Canada, 153

S. W. (2d) 12 (1941). Petitioner in this case sought by

writ of mandamus to compel her admission to the School of

Journalism at the University of Missouri. The court de

nied the writ on the ground that the state could properly

maintain a policy of segregation and that its right to so do

had this Court’s approval. Section 9618 of the Missouri

Statutes Annotated was again construed as placing upon

the Board of Curators of Lincoln University a mandatory

duty to establish facilities at Lincoln University equal to

those at the University of Missouri. The court held that

although no School of Journalism was available there, the

board was under a duty to open new departments on de

mand and was entitled to a reasonable time after demand

to establish the facility. Only after a demand of the board

of the Negro college and a refusal within a reasonable time,

or an assertion by the board that it was unable to establish

the facility demanded, would admission of a Negro to the

existing facility be granted. This decision construed the

12 32 Fed. Supp. 707, 711.

25

Gaines case as meaning that a Negro must not only first

make a demand upon the board of the Negro school, but

that there must either be an outright refusal or failure to

establish the facilities within a reasonable time before a

petitioner could successfully obtain redress to which he was

entitled under the Gaines decision.

In 1942, in the case of State ex rel. Michael v. Whitham

(165 S. W. (2d) 378), six Negroes sought by writ of man

damus admission to the graduate and professional schools

of the University of Tennessee. The cases were consolidated,

and while pending, the state passed a statute on February

13, 1941, Chapter 43 of the Public Acts of 1941, which stated

in part as follows:

“ Be it enacted by the General Assembly of the

State of Tennessee, That the State Board of Edu

cation and the Commissioner of Education are hereby

authorized and directed to provide educational train

ing and instruction for Negro citizens of Tennessee

equivalent to that provided at the University of Ten

nessee for white citizens of Tennessee.”

The court held that the Board of Education was under

a mandatory duty to establish graduate facilities and pro

fessional training for Negroes equivalent to that at the

University of Tennessee upon demand and a reasonable ad

vance notice. The statute, the court held, provided a com

plete and full method by which Negroes may obtain edu

cational training and instruction equivalent to that at the

University of Tennessee.

As the Gaines case was there construed, a Negro seeking

professional or graduate training offered whites at the State

University must: (1) first make a demand for training in a

separate school of the Board charged with the duty of pro

viding equal facilities for Negroes; and, (2) give that Board

26

a reasonable time thereafter to set up the separate facility

before a petitioner could successfully bring himself within

the holding of the Gaines case. Even the mere statutory

declaration of intent adopted while the case was pending,

although unfulfilled, was found by the Tennessee Supreme

Court to be an adequate answer to petitioner’s assertion of

a denial of equal protection. And this even though this

Court had clearly and conclusively disposed of that con

tention in the Gaines case.

Finally, the State of Oklahoma, relying upon these latter

decisions, refused to admit petitioner to the law school of

the University of Oklahoma on the grounds that the segre

gation statutes of Oklahoma are a complete bar to peti

tioner’s claimed right to attend the only law school main

tained by the state and that she must, therefore, make a

demand on certain officials to establish a separate law school

for her.

The Supreme Court of Oklahoma, therefore, construed

the decision in the Gaines case as follows: “ The reasoning

and spirit of that decision of course is applicable here, that

is, that the state must provide either a proper legal training

for petitioner in the state, or admit petitioner to the Uni

versity Law School. But the very existence of the option

to do the one or the other imports the right or an oppor

tunity to choose the one of the two courses which will follow

the fixed policy of the state as to separate schools, and

before the courts should foreclose the option the oppor

tunity to exercise it should be accorded” (R. 47).

At the very least the Gaines case means, we submit, that

a state cannot bar a qualified Negro from the only existing

facility in spite of its policy of segregation. Moreover, the

burden of decision as to whether the segregated system will

be maintained is upon the state and not upon an aggrieved

27

Negro who seeks the protection of the federal constitution.

As a party whose individual constitutional rights have been

infringed, petitioner is entitled to admission to the law

school of the University of Oklahoma now. Any burden

placed upon her which is not required of other law school

applicants is a denial of equal protection. Her rights iannot

be defeated nor her assertion thereof he burdened by re

quiring that she demand a state body to provide her with

a legal education at some future time. The state is charged

with the responsibility of giving her equal protection at

the time she is entitled to it. The shams and legalism which

have been raised to bar her right to redress must not be

allowed to stand in the way.

The basic weakness of the Gaines decision was that while

recognizing that petitioner’s only relief and redress was

admission to the existing facility, the opinion created the

impression that this Court would give its sanction even in

cases of this type, to a state’s reliance upon the “ equal but

separate” doctrine. This Court, therefore, must reexamine

the basis for its statement asserting the validity of racial

separation which statement has been used to deny to peti

tioner the protection of the constitutional right to which

she is entitled.

B. The Doctrine of “ Separate But Equal” Is Without

Legal Foundation.

Classifications and distinctions based on race or color

have no moral or legal validity in our society. They are

contrary to our constitution and laws, and this Court has

struck down statutes, ordinances or official policies seeking

to establish such classifications. In the decisions concerning

intrastate transportation and public education, however,

this Court appears to have adopted a different and anti-

28

tbetical constitutional doctrine under which racial separa

tion is deemed permissible when equality is afforded. An

examination of these decisions will reveal that the “ separate

but equal” doctrine is at best a bare constitutional hypothe

sis postulated in the absence of facts showing the circum

stances and consequences of racial segregation and based

upon a fallacious evaluation of the purpose and meaning

inherent in any policy or theory of enforced racial sepa

ration.

Many states have required segregation of Negroes from

all other citizens in public schools and on public convey

ances. The constitutionality of these provisions has seldom

been seriously challenged. No presumption of constitu

tionality should be predicated on this non-action. A similar

situation existed for many years in the field of interstate

travel where state statutes requiring segregation in inter

state transportation were considered to be valid and en

forced in several states for generations and until this Court

in 1946 held that such statutes were unconstitutional when

applied to interstate passengers.13

The Thirteenth, Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments

were adopted for the purpose of securing to a recently

emancipated race all the civil rights of other citizens.14

Unfortunately this has not been accomplished. The legisla

tures and officials of the southern states have, through

legislative policy, continued to prevent Negro citizens from

obtaining their civil rights by means of actions which only

gave lip service to the word “ equal.” One of the most

authoritative studies made of the problem of the Negro in

the United States points out that:

“ While the federal Civil Rights Bill of 1875 was

declared unconstitutional, the Reconstruction Amend- * 11

13 Morgan v. Virginia, 328 U. S. 373.

11 Strauder v. West Virginia; 100 U. S. 303.

29

merits to the Constitution—which provided that the

Negroes are to enjoy full citizenship in the United

States, that they are entitled to ‘ equal benefit of all

laws,’ and that ‘ no state shall make or enforce any

law which shall abridge the privileges and immunities

of citizens of the United States’—could not be so

easily disposed of. The Southern whites, therefore,

in passing their various segregation laws to legalize

social discrimination, had to manufacture a legal fic

tion of the same type as we have already met in the

preceding discussion on politics and justice. The

legal term for this trick in the social field, expressed

or implied in most of the Jim Crow statutes, is

‘ separate but equal.’ That is, Negroes were to get

equal accommodations, but separate from the whites.

It is evident, however, and rarely denied, that there

is practically no single instance of segregation in the

South which has not been utilized for a significant

discrimination. The great difference in quality of

service for the two groups in the segregated set-ups

for transportation and education is merely the most

obvious example of how segregation is an excuse for

discrimination. Again the Southern white man is in

the moral dilemma of having to frame his laws in

terms of equality and to defend them before the

Supreme Court—and before his own better con

science, which is tied to the American Creed—while

knowing all the time that in reality his laws do not

give equality to Negroes, and that he does not want

them to do so.” 15

In one of the early cases interpreting these amend

ments it was pointed out that: “ At the time when they were

incorporated into the Constitution, it required little knowl

edge of human nature to anticipate that those who had

long been regarded as an inferior and subject race would,

when suddenly raised to the rank of citizenship, be looked

upon with jealousy and positive dislike, and that state laws

]S Gunnar Myrdal, An American Dilemma (1944), Vol. 1, pages

580, 581.

30

might be enacted or enforced to perpetuate the distinctions

that had before existed. Discrimination against them had

been habitual. It was well known that, in some States, laws

making such discriminations then existed, and others might

well be expected. . . . They especially needed protection

against unfriendly action in the States where they were

resident. It was in view of these considerations the 14th

Amendment was framed and adopted. It was designed to

assure to the colored race the enjoyment of all of the civil

rights that under the law are enjoyed by white persons, and

to give to that race the protection of the General Govern

ment, in that enjoyment, whenever it should be denied by

the States. It not only gave citizenship and the privileges

of citizenship to persons of color, but it denied to any State

the power to withhold from them the equal protection of the

laws, and authorized Congress to enforce its provisions by

appropriate legislation.” 16

Mr. Justice S tkong in this opinion also stated: “ The

words of the Amendment, it is true, are prohibitory, but

they contain a necessary implication of a positive immunity,

or right, most valuable to the colored race— the right to

exemption from unfriendly legislation against them dis

tinctly as colored; exemption from legal discrimination, im

plying inferiority in civil society, lessening the security of

their enjoyment of the rights which others enjoy, and dis

criminations which are steps towards reducing them to the

condition of a subject race.” 17

It is unfortunate that the first case to reach this Court

on the question of whether or not segregation of Negroes

was a violation of the Fourteenth Amendment should come

during the period immediately after the Civil War when

10 Strauder v. W est Virginia, supra, at 306.

17 Ibid.

31

the Fourteenth Amendment was regarded as a very narrow

limitation on state’s rights.

The first expression by this Court of the doctrine of

“ separate but equal” facilities in connection with the re

quirements of equal protection of the law appears in the

case of Plessy v. Ferguson}6 That case involved the validity

of a Louisiana statute requiring segregation on passenger

vehicles. The petitioner there claimed that the statute

was unconstitutional and void. A demurrer by the State

of Louisiana was sustained, and ultimately this Court

affirmed the judgment of the Louisiana courts in holding

that the statute did not violate the Thirteenth Amendment

nor did it violate the Fourteenth Amendment. Mr. Justice

Brown in his opinion for the majority of the Court pointed

out that:

“ A statute which implies merely a legal distinc

tion between the white and colored races—a distinc

tion which is founded in the color of the two races,

and which must always exist so long as white men

are distinguished from the other race by color—has

no tendency to destroy the legal equality of the two

races, or reestablish a state of involuntary servi

tude . . . ” (163 U. S. 537, 543).

Mr. Justice Brown, in continuing, stated that the object

of the Fourteenth Amendment was to enforce absolute

equality before the law but:

“ . . . Laws permitting, and even requiring, their

separation in places where they are liable to be

brought into contact do not necessarily imply the in

feriority of either race to the other, and have been

generally, if not universally, recognized as within the

competency of the state legislatures in the exercise

of their police power. . . . ” 18 19

18163 U. S. 537, 543.

19 Id. at page 543.

32

It should be noted that this case was based solely on

the pleadings, and that there was no evidence either before

the lower courts or this Court on either the reasonableness

of the racial distinctions or of the inequality resulting from

segregation of Negro citizens. The plaintiff’s right to

“ equality” in fact was admitted by demurrer. The deci

sion in the Plessy case appears to have been based upon the

decision of Roberts v. Boston, 5 Cush. 198 (1849), a case

decided before the Civil War and before the Fourteenth

Amendment was adopted. In the Plessy case, the majority

opinion cites and relies upon language in the decision in

the Roberts case and added: “ It was held that the powers

of the Committee extended to the establishment of separate

schools for children of different ages, sexes and colors,

and that they might also establish special schools for poor

and neglected children, who have become too old to attend

the primary school, and yet have not acquired the rudiments

of learning, to enable them to enter the ordinary schools.” 20

Mr. Justice H arlan in his dissenting opinion pointed out

that: 11

11 In respect of civil rights, common to all citizens,

the Constitution of the United States does not, I

think, permit any public authority to know the race

of those entitled to be protected in the enjoyment of

such rights. Every true man has pride of race, and

under appropriate circumstances, when the rights of

others, his equals before the law, are not to be af

fected, it is his privilege to express such pride and

to take such action based upon it as to him seems

proper. But I deny that any legislative body or ju

dicial tribunal may have regard to the race of citizens

when the civil rights of those citizens are involved.

Indeed such legislation as that here in question is

inconsistent, not only with that equality of rights

20 Id . at pages 544-545.

33

which pertains to citizenship, national and state, but

with the personal liberty enjoyed by every one within

the United States” (163 U. S. 537, 554-555).

and

“ There is no caste here. Our Constitution is

color-blind, and neither knows nor tolerates classes

among citizens. In respect of civil rights, all citizens

are equal before the law. The humblest is the peer

of the most powerful. The law regards man as man,

and takes no account of his surroundings or of his

color when his civil rights as guaranteed by the su

preme law of the land are involved. It is therefore

to be regretted that this high tribunal, the final ex

positor of the fundamental law of the land, has

reached the conclusion that it is competent for a state

to regulate the enjoyment by citizens of their civil

rights solely upon the basis of race” (163 U. S. 537,

559).

More recent decisions of the Supreme Court support Mr.

Justice H arlan ’s conclusion.21 In re-affirming the invalidity

of racial classification by governmental agencies, Mr. Chief

Justice Stone speaking for the Court in the case of Ilira-

bayashi v. United States stated: “ Distinctions between

citizens solely because of their ancestry are by their very

nature odious to a free people whose institutions are founded

upon the doctrine of equality. For that reason legislative

classification or discrimination based on race alone has

often been held to be a denial of equal protection.” 22

In the same case, Mr. Justice M urphy filed a concurring

opinion in which he pointed out that racial distinctions

based on color and ancestry “ are utterly inconsistent with

our traditions and ideals. They are at variance with the

principles for which wTe are now waging war.” 23

21 Hirabayashi v. United States, 320 U. S. 81.

22 id. at page 100.

23 Id. at page 110.

34

Mr. Justice M urphy in a concurring opinion in a case

involving discrimination against Negro workers by a rail

road brotherhood acting under a federal statute (Railway

Labor Act) pointed out:

“ Suffice it to say, however, that this constitutional

issue cannot be lightly dismissed. The cloak of

racism surrounding the actions of the Brotherhood

in refusing membership to Negroes and in entering

into and enforcing agreements discriminating against

them, all under the guise of Congressional authority,

still remains. No statutory interpretation can erase

this ugly example of economic cruelty against colored

citizens of the United States. Nothing can destroy

the fact that the accident of birth has been used as

the basis to abuse individual rights by an organiza

tion purporting to act in conformity with its Con

gressional mandate. Any attempt to interpret the

Act must take that fact into account and must realize

that the constitutionality of the statute in this respect

depends upon the answer given.

“ The Constitution voices its disapproval when

ever economic discrimination is applied under au

thority of law against any race, creed or color. A

sound democracy cannot allow such discrimination to

go unchallenged. Racism is far too virulent today to

permit the slightest refusal, in the light of a Consti-

tion that abhors it, to expose and condemn it where-

ever it appears in the course of a statutory interpre

tation. ’ ’ 24

The doctrine of “ separate but equal” treatment recog

nized in Plessy v. Ferguson was arrived at not by any study

or analysis of facts but rather as a result of an ad hominem

conclusion of “ equality” by state courts. As a matter of

fact, this Court has never passed directly upon the question

of the validity or invalidity of state statutes requiring the

24 Steele v. L. N. R. R. Co., 323 U. S. 192, 209.

35

segregation of the races in public schools. The first case

on this point in this Court is Cummings v. Richmond County

Board of Education25 The Board of Education of Rich

mond County, Georgia, had discontinued the only Negro

high school but continued to maintain a high school for

white pupils. Petitioner sought an injunction to restrain

the board from using county funds for the maintenance of

the white high school. The trial court granted an injunction

which was reversed by the Georgia Supreme Court and af

firmed by this Court. The opinion written by Mr. Justice

H arlan expressly excluded from the issues involved any

question as to the validity of separate schools. The opinion

pointed out:

“ It was said at the argument that the vice in the

common-school system of Georgia was the require

ment that the white and colored children of the state

be educated in separate schools. But we need not

consider that question in this case. No such issue

was made in the pleadings” (175 U. S. 528, 543).

In the case Gong Lum v. Rice,26 the question was raised

as to the right of a state to classify Chinese as colored and to

force them to attend schools set aside for Negroes. In that

case the Court assumed that the question of the right to

segregate the races in its educational system had been de

cided in favor of the states by previous Supreme Court

decisions.

The next school case was the Gaines case which has been

discussed above. In that case this Court without making an

independent examination of the validity of the doctrine of

“ separate but equal” facilities stated: “ The state has

sought to fulfill that obligation by furnishing equal facili

25 175 U. S. 528.

26 275 U. S. 78.

36

ties in separate schools, a method the validity of which has

been sustained by our decisions.” This Court cited as au

thority for this statement the decisions which have been

analyzed above.

Segregation in public education helps to preserve and

enforce a caste system which is based upon race and color.

It is designed and intended to perpetuate the slave tradi

tion sought to be destroyed by the Civil War and to prevent

Negroes from attaining the equality guaranteed by the fed

eral Constitution. Racial separation is the aim and motive

of paramount importance— an end in itself. Equality, even

if the term be limited to a comparison of physical facili

ties, is and can never be achieved.

The only premise on which racial separation can be

based is that the inferiority and the undesirability of the

race set apart make its segregation mandatory in the inter

est of the well-being of society as a whole. Hence the very

act of segregation is a rejection of our constitutional axiom

of racial equality of man.

The Supreme Court in Plessy v. Ferguson, as we have

seen, without any facts before it upon which to make a

valid judgment adopted the “ separate but equal” doctrine.

Subsequent cases have accepted this doctrine as a constitu

tional axiom without examination. Hence what was in re

ality a legal expedient of the Reconstruction Era has until

now been accepted as a valid and proved constitutional

theory.

C. Equality Under a Segregated System Is a Legal Fic

tion and a Judicial Myth.

There is of course a dictionary difference between the

terms segregation and discrimination. In actual practice,

however, this difference disappears. Those states which

37

segregate by statute in the educational system have been

primarily concerned with keeping the two races apart and

have uniformly disregarded even their own interpretation

of their requirements under the Fourteenth Amendment to

maintain the separate facilities on an equal basis.

1. The General Inequities in Public Educational

Systems Where Segregation Is Required.

Racial segregation in education originated as a device to

“ keep the Negro in his place” , i. e., in a constantly inferior

position. The continuance of segregation has been synony

mous with unfair discrimination. The perpetuation of the

principle of segregation, even under the euphemistic theory

of “ separate but equal” , has been tantamount to the perpet

uation of discriminatory practices. The terms “ separate”

and “ equal” can not be used conjunctively in a situation

of this kind; there can he no separate equality.

Nor can segregation of white and Negro in the matter

of education facilities be justified by the glib statement

that it is required by social custom and usage and generally

accepted by the “ society” of certain geographical areas.

Of course there are some types of physical separation which

do not amount to discrimination. No one would question

the separation of certain facilities for men and women, for

old and young, for healthy and sick. Yet in these cases no

one group has any reason to feel aggrieved even if the

other group receives separate and even preferential treat

ment. There is no enforcement of an inferior status.

This is decidedly not the case when Negroes are seg

regated in separate schools. Negroes are aggrieved; they

are discriminated against; they are relegated to an inferior

position because the entire device of educational segregation

has been used historically and is being used at present to

38

deny equality of educational opportunity to Negroes. This

is clearly demonstrated by the statistical evidence which

follows.

The taxpayers’ dollar for public education in the 17

states and the District of Columbia which practice com

pulsory racial segregation was so appropriated as to de

prive the Negro schools of an equitable share of federal,

state, county and municipal funds. The average expense

per white pupil in nine Southern states reporting to the

U. S. Office of Education in 1939-1940 was almost 212%

greater than the average expense per Negro pupil.27 Only

$18.82 was spent per Negro pupil, while the same average

per white pupil was $58.69.28

Proportionate allocation of tax monies is only one cri

terion of equal citizenship rights, although an important

one. By every other index of the quality and quantity of

educational facilities, the record of those states where seg

regation is a part of public educational policy clearly demon

strates the inequities and second class citizenship such a

policy creates. For example, these states in 1939-1940 gave

whites an average of 171 days of schooling per school term.

Negroes received an average of only 156 days.29 The aver

age for a white teacher was $1,046 a year. The average

Negro teacher’s salary was only $601.30

The experience of the Selective Service administration

during the war provides evidence that the educational in

equities created by a policy of segregation not only deprive

27 Statistics of the Education of Negroes (A Decade of Progress)