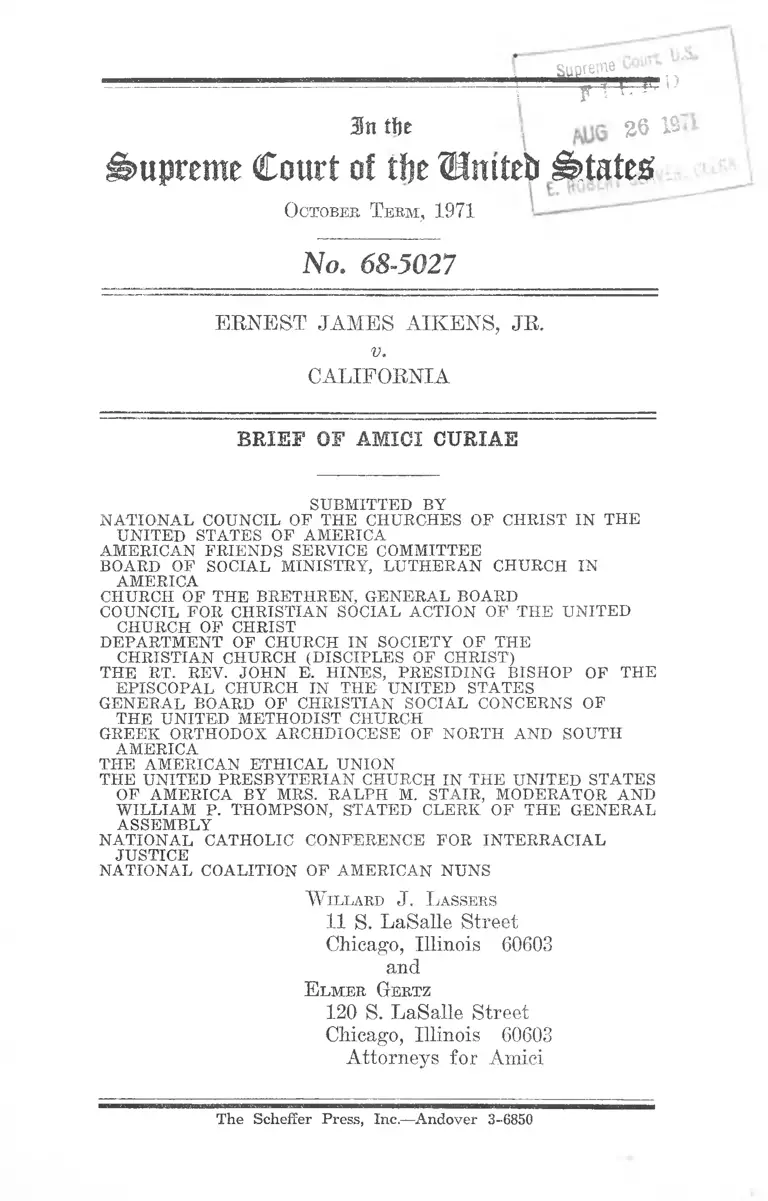

Aikens v. California Brief of Amici Curiae

Public Court Documents

August 26, 1971

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Aikens v. California Brief of Amici Curiae, 1971. dd5d6920-ac9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/70c7126a-9430-4901-8a9f-12a512162bcc/aikens-v-california-brief-of-amici-curiae. Accessed February 24, 2026.

Copied!

1 suprem e

--------------- ----- -------------- ------- --------------------- ------- \ T 1 - + ; 4 v i >

in tfje ; % Q 18

Suprem e C o u rt of tfje Untteii S ta te s

October T erm , 1971

No. 68-5027

ERNEST JAMES AIKENS, JR.

v.

CALIFORNIA

BRIEF OF AMICI CURIAE

SUBMITTED BY

NATIONAL COUNCIL OF THE CHURCHES OF CHRIST IN THE

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

AMERICAN FRIENDS SERVICE COMMITTEE

BOARD OF SOCIAL MINISTRY, LUTHERAN CHURCH IN

AMERICA

CHURCH OF THE BRETHREN, GENERAL BOARD

COUNCIL FOR CHRISTIAN SOCIAL ACTION OF THE UNITED

CHURCH OF CHRIST

DEPARTMENT OF CHURCH IN SOCIETY OF THE

CHRISTIAN CHURCH (DISCIPLES OF CHRIST)

THE RT. REV. JOHN E. HINES, PRESIDING BISHOP OF THE

EPISCOPAL CHURCH IN THE UNITED STATES

GENERAL BOARD OF CHRISTIAN SOCIAL CONCERNS OF

THE UNITED METHODIST CHURCH

GREEK ORTHODOX ARCHDIOCESE OF NORTH AND SOUTH

AMERICA

THE AMERICAN ETHICAL UNION

THE UNITED PRESBYTERIAN CHURCH IN THE UNITED STATES

OF AMERICA BY MRS. RALPH M. STAIR, MODERATOR AND

WILLIAM P. THOMPSON, STATED CLERK OF THE GENERAL

ASSEMBLY

NATIONAL CATHOLIC CONFERENCE FOR INTERRACIAL

JUSTICE

NATIONAL COALITION OF AMERICAN NUNS

W illard J. L assers

11 S. LaSalle Street

Chicago, Illinois 60608

and

E l m e r H e r t z

120 S. LaSalle Street

Chicago, Illinois 60603

Attorneys for Amici

The Scheffer Press, Inc.—Andover 3-6850

TABLE OF CONTENTS

BRIEF OF AMICI CURIAE

PAGE

Introduction ...... ...................................................... 1

Summary of Argument.......................................... ....... 9

Argument ........................................................................ 10

I. The Punishment of Death is Cruel and Unusual .... 10

The moral conflict of the scrupled ju ro r .......... 13

The tria l: the role of chance.............................. 14

The trial: subjective determinations ................ 15

The voluntariness of confessions ..................... 17

Shifting judicial rules, substantive and proce

dural .................. 20

Recent death penalty cases in this court: due

process aspects .............................................. 22

Prosecution suppression of evidence favorable

to accused ....................................................... 25

The four cases at ba r: due process aspects...... 27

The death penalty and suicide............................ 28

The condemned man, the wait and the execu

tion ........................ 29

Summation ........................................................... 31

Appendix

Policy Statements Opposing the Death Penalty Adopted

by Amici and other Religious Organizations.

National Council of the Churches of Christ in the

United States of America .......... la

11

PAGE

TABLE OF CONTENTS

American Baptist Convention .................. ................... 3a

Lutheran Church in America......................................... 4a

Christian Churches (Disciples of Christ) ................. 6a

Church of the Brethern .............................................. 7a

Mennonite Church ......... 8a

The Methodist Chuch ........................ ..... ..................... 8a

The Protestant Episcopal Church in the United States

of America ..... ............................ .............. ...... .......■ • 9a

Union of American Hebrew Congregations................. 9a

Central Conference of American Rabbis ..................... 10a

United Synagogue of America ........................... ........ 10a

Unitarian Universalist Association ............................ 11a

United Church of Christ ......................................... Ha

The United Presbyterian Church in the United States

of America ........................................ .......... ....... 13a

National Catholic Conference for Interracial Justice .. 13a

The National Coalition of American Nuns ................. 14a

Cases

Alcorta v. Texas, 355 U.S. 28 (1957) ......................... 16

Application of Kapatos, 208 F. Supp, 883 (N.Y.,

1962) ........................................................................... 27

Ashley v. Texas, 319 F. 2d 80 (CA 5th 1963), cert,

den., 375 U.S. 931 (1963) ........................................... 26

Barbee v. Warden, 331 F. 2d 842 (CA 4th, 1964) ...... 26

Bernette v. Illinois, ...... U.S.........., 39 L. W. 3566

(June 28, 1971) ..................................... 24,25

Ill

PAGE

Brady v. U. S., 397 U.S. 742 (1970) .......................... 13

Brady v. Maryland, 373 U.S. 83 (1963) ..................... 26

Chessman v. Teets, 354 U.S. 156 (1957) .......... ........... 20

Ciucci v. Illinois, 356 U.S. 571 (1958) ..................... 21

Comm. v. Chester, 337 Mass. 702, 150 N.E. 2d 914

(1958) ......................................................................... 28

Crampton v. Ohio.......... U.S........., 29 L. ed. 711

(1971) ........... 22,23

French v. State, 377 P. 2d 501 (Okla,, 1967), 397 P.

2d 909 (1963), 416 P. 2d 171 at 178 (1966) ............ 29

Giles v. Maryland, 386 U.S. 66 (1967) ........................ 19

Hunter v. Tennessee,..... . U.S......... (June 28, 1971) .. 24

Labat v. Bennett, 365 F. 2d 698 (CA 5th, 1966) ....... 19,31

Levin v. Katzenbach, 363 F. 2d 287 (D.C. Cir. 1966) .. 27

Maxwell v. Bishop, 398 U.S. 262 (1970) ............... . 22

Maxwell v. Bishop, 393 U.S. 997 (1968) ..................... 23

Maxwell v. Bishop, 385 U.S. 650 (1967) ..................... 23

McGautha v. California, ...... U.S......... , 29 L. ed. 2d

711 (1971) ................................................ 22,23,27

McMullin v. Maxwell, 3 Ohio St. 2d 160, 209 N.E. 2d

449 (1965) .............. 27

Miller v. Pate, 386 U.S. 1 (1967) ................................ 26

Moore v. 111. cert. gr. June 28, 1971 ........................ 25

North Carolina v. Alford, 400 U.S. 25 (1970) .......... 13

People v. Bernette, 30 111. 2d 359, 197 N.E. 2d 436

(1964) ........... 25

People v. Bernette et al., 45 111. 2d 227, 258 N.E. 2d

793 (1970) ..... ............ .................... ........................... 25

IV

PAGE

People v. Chessman, 38 Cal. Kept. 2d 166 at 192, 338

P. 2d 1001 (1959) ...................................................... 21

People v. Daniels, 71 Cal. 2d 1119, 80 Cal. Kept. 897,

459 P. 2d 225 (1969) .................................................. 21

People v. Golson, 32 111. 2d 398, 207 N.E. 2d 68 at 75

(1965) ......................................................................... 21

People v. Mutch, 93 Cal. Kept, 721, 482 P. 2d 63

(March 24, 1971) .................. 21

People v. Tajra, 58 111. App. App. 2d 479, 208 N.E.

2d 9 (1965) ............................... 25

People v. Wilson, 29 111. 2d 82, 193 N.E. 2d 499

(1963) ......................................................................... 13

Pixley v. State, 406 P. 2d 662 (Wvo., 1965) .............. 29

Beeves v. Peyton, 384 U.S. 312 (1966) ..................... 28

State v. Giles, 245 Md. 342, 227 Atl. 2d 745 (1967) .... 19

Tajra v. Illinois, ...... U.S........., 39 L. W. 3566 (June

28, 1971) .................................................................... 24

Townsend v. Sain, 372 U.S. 293 (1963) ........................ 17

Turner v. Ward, 321 F. 2d 18 (CA 10th, 1963) ...... 26

U. S. ex rel Almeida v. Baldi, 195 F. 2d 815 (CA 3rd,

1952), cert. den. 345 U.S. 904 (1953) ..................... 26

U. S. ex rel Butler v. Maronev, 319 F. 2d 622 (CA

3rd, 1963) ..............................'..................................... 26

U. S. ex rel Meers v. Wilkins, 326 F. 2d 135 (CA 2d,

1964) ................... 96

U. S. ex rel Montgomery v. Ragen, 86 F. Supp. 382

(1949) ......... 27

U. S. ex rel Smith v. New Jersey, 322 Fed. 2d 810

(CA 3rd, 1968) ........................................................... 18

U. S. ex rel Smith v. Yeager, 395 Fed. 2d 245 (CA

3rd, 1968) ............................ 19

PAGE

U. S. ex rel Thompson v. Dve, 221 F. 2d 763 (CA 3rd,

1955), cert, den., 350 U.S. 875 (1955) ..................... 26

U. S. ex rel Townsend v. Twomev, 322 F. Snpp. 158

(1971) ............................................................ ............ 18

Williams v. Illinois, 342 U.S. 934 (1952) ..................... 28

Witherspoon v. Illinois, 391 U.S. 510 (1968) ..........13, 22

S tatutes

111. Rev. Stats. (1971) C. 38, §§ 3-3(b) and 4 ........ 22

111. Rev. Stats. (1953) C. 38, §769.1 ............................ 28

111. Rev. Stats. (1951) C. 38, §§769 and 769.1............. 27

Other A uthorities

Bedau, The Death Penalty in America C. 6, p. 258 .... 10

Chicago Sun Times, June 9, 1971, p. 18 ..................... 19

Chicago Tribune, April 13, 1967, Sec. 1, p. 8 .............. 30

Gallagher, Thomas, Invitation to a Killing (N.T.

Herald Tribune, February 7, 1965) ........................ 30

Gottlieb, Capital Punishment, 15 Crime and De

linquency (1969) ....................................................... 30

Jesse ed. Trials of Timothy John Evans et al .......... 11

MacNamara, Convicting the Innocent, 15 Crime and

Delinquency 57 (1969) ............... 12

Mochulsky, Dostoevsky, His Life and Work, 140

(Princeton U. Press, 1967) ..................................... 31

New York Times, Dec. 30, 1969 ............................... 19

New York Times, July 23, 1971, p. 31 ......................... 30

New York Times, May 5, 1971, p. 41 ......................... 30

New York Times, July 6, 1967, p. 27 ......................... 19

VI

PAGE

New York Times, April 13, 1967, p. 13 ..................... 30

New York Times, October 19, 1966, p. 19 .............. 11

Statistical Abstract of the United States, 1951, Table

74> P- 69 ......................... ................................ ...... ..... 20

Statistical Abstract of the United States, 1970, Table

220 ............................................................................................. . 20

Sellin, The Death Penalty (1959) .......... ..................... 29

Wiseman, Psychiatry and Law, “Use and Abuse of

Psychiatry in a Murder Case.” American Journal of

Psychiatry, October 1961, p. 289 ................... .......... 28

I n T h e

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

O c t o b e r T e r m , 1971

No. 68-5027

ERNEST JAMES AIKENS, JR.

V.

CALIFORNIA

BRIEF OF AMICI CURIAE

SUBMITTED BY

NATIONAL COUNCIL OF THE CHURCHES OF CHRIST IN THE

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

AMERICAN FRIENDS SERVICE: COMMITTEE

BOARD OF SOCIAL MINISTRY, LUTHERAN CHURCH IN

AMERICA

CHURCH OF THE BRETHREN, GENERAL BOARD

COUNCIL FOR CHRISTIAN SOCIAL ACTION OF THE UNITED

CHURCH OF CHRIST

DEPARTMENT OF CHURCH IN SOCIETY OF THE

CHRISTIAN CHURCH (DISCIPLES OF CHRIST)

THE RT. REV. JOHN E. HINES, PRESIDING BISHOP OF THE

EPISCOPAL CHURCH IN THE UNITED STATES

GENERAL BOARD OF CHRISTIAN SOCIAL CONCERNS OF

THE UNITED METHODIST CHURCH

GREEK ORTHODOX ARCHDIOCESE OF NORTH AND SOUTH

AMERICA

THE AMERICAN ETHICAL UNION

THE UNITED PRESBYTERIAN CHURCH IN THE UNITED STATES

OF AMERICA BY MRS. RALPH M. STAIR, MODERATOR AND

WILLIAM P. THOMPSON, STATED CLERK OF THE GENERAL

ASSEMBLY

NATIONAL CATHOLIC CONFERENCE FOR INTERRACIAL

JUSTICE

NATIONAL COALITION OF AMERICAN NUNS

INTRODUCTION

The above religious organizations, by their attorneys,

Willard J. Lassers and Elmer Gertz, file this brief amici

curiae in support of petitioner. Petitioner and respondent

have consented to the filing of this brief.

The religious organizations represent as follows:

The legal arguments on behalf of petitioner will be pre

sented by his counsel. There are, however, a number of

ethical considerations of deep concern to the religious or

ganizations. Most of these organizations formally have

taken stands in opposition to capital punishment. In the

appendix to this brief we include the formal statements

of amicus National Council of the Churches of Christ in

the United States of America, other amici religious organi

zations and other denominations. We note additionally

that the World Council of Churches at its International

Conference at Addis Ababa on January 10-21, 1971, de

clared,

“Recent events in many countries have compelled us to

think especially about capital punishment.

“We are convinced that one significant expression, at

this time of history, of the belief of the Christian Church

in the sanctity and dignity of human life would be the

promotion of common and concerted efforts towards the

abolition of capital punishment.”

Amici desire to present views somewhat different from

that of petitioner and other amici. These views they think

will contribute to a more complete understanding of the

case.

This brief while formally submitted in Aikens v. Cali

fornia, No. 68-5027, is relevant also to the three companion

cases, Furman v. Georgia, No. 69-5003, Jackson v. Georgia,

No. 69-5030, and Branch v. Texas, No. 69-5031. We shall

refer to these eases in this brief.

The National Council of the Churches of Christ in the

United States of America is a federation of 33 national

— 3 —

denominations with an aggregate membership of about

42,000,000. Among them are several Eastern Orthodox

bodies and several predominantly black denominations.

The amici other religious organizations have a total mem

bership exceeding 26,400,000 (a portion of which is in

cluded among the 42,000,000 just mentioned).

The amici a re :

1. NATIONAL COUNCIL OF THE CHURCHES OF

CHRIST IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

The National Council of the Churches of Christ in the

United States of America is a federation of thirty-three

national denominations with an aggregate membership of

approximately 42,000,000. Among them are several East

ern Orthodox bodies and several predominantly black de

nominations. The National Council of Churches is govern

ed by a General Board of 250 members made up exclusive

ly of representatives of the member denominations propor

tionate to their size and support and chosen according to

their own respective procedures. In September, 1968, the

General Board adopted a policy statement urging the

abolition of the death penaltj^, by a vote of 103 for,

0 against, and 0 abstaining.

2. AMERICAN FRIENDS SERVICE COMMITTEE

The American Friends Service Committee has, since

1917, engaged in religious, charitable, social, philanthropic

and relief work on behalf of the several branches and divi

sions of the Religious Society of Friends in America.

There are approximately 123,000 Friends in the United

States. The American Friends Service Committee, al

though it cannot speak for all Friends, has a vital interest

in this litigation because of Friends’ historic and continued

opposition to the taking of human life by the State. Such

— 4 —

opposition to capital punishment goes back more than 300

years, to the beginning of the Quaker movement and stems

from Quaker belief that there is an element of the divine

in every man.

3. BOARD Or SOCIAL MINISTRY, LUTHERAN

CHURCH IN AMERICA

The Board of Social Ministry is an instrumentality of

the Lutheran Church in America. Its object is “to inquire

into the nature and proper obedience of the church’s minis

try within the structures of social life . . . devoting itself in

particular to those aspects of the church’s ministry in

which individual and social needs are met as an expression

of Christian responsibility for love and justice.”

The 1966 biennial convention of the Lutheran Church

in America adopted a social statement on capital punish

ment urging abolition of capital punishment. The Lutheran

Church in America has 3,300,000 members in 6,225 congre

gations in the United States and Canada.

4. CHURCH OF THE BRETHREN GENERAL

BOARD

The Church of the Brethren General Board is the ad

ministrative arm of the Church of the Brethren. It carries

out policies adopted by the church’s legislative arm—

Annual Conference—in the areas of world ministries, par

ish ministries and general services. Among its world min

istries are efforts to correct social injustices at home and

abroad. The Church of the Brethren lias adopted policy

statements opposing capital punishment on several occa

sions, the last one being in 1959 at the Annual Conference.

The Church of the Brethren has 200,000 members in ap

proximately 1,000 churches.

— 5 —

5. COUNCIL FOR CHRISTIAN SOCIAL ACTION

OF THE UNITED CHURCH OF CHRIST

The Council for Christian Social Action is an instru

mentality of the United Church of Christ devoted to pro

moting education and action in international, political and

economic affairs. The Council stated its position in oppo

sition to capital punishment in a policy statement of Janu

ary 30, 1962. The United Church of Christ has over 2,000,-

000 adherents.

6. DEPARTMENT OF CHURCH IN SOCIETY OF

THE CHRISTIAN CHURCH (DISCIPLES OF

CHRIST)

The Department of Church in Society of the Division

of Homeland Ministries is a part of The United Christian

Missionary Society, a national unit of the Christian Church

(Disciples of Christ). The Christian Church has approved

two resolutions on capital punishment in its International

Convention. The first resolution, approved in October

1957 at Cleveland, Ohio, stressed the need for rehabilita

tion of criminals and indicated that “the practice of capital

punishment stands in the way of more creative, redemptive

and responsible treatment of crime and criminals. The

second, “Concerning Abolition of Capital Punishment,”

was approved in the October 1962 Assembly of the Inter

national Convention at Los Angeles, California. This reso

lution specifically placed the Christian Church (Disciples

of Christ) on record as “favoring a program of rehabilita

tion for criminal offenders rather than capital punish

ment.”

The Christian Church (Disciples of Christ) in the Unit

ed States and Canada has a membership of 1,600,648.

7. THE RT. REV. JOHN E, HINES,

PRESIDING BISHOP OF THE EPISCOPAL

CHURCH IN THE UNITED STATES

The Presiding Bishop is the president of The Domestic

and Foreign Missionary Society of The Protestant Epis

copal Church in the United States of America which has

7,464 parishes and missions, 11,772 ordained clergy and

3,475,164 baptized members. The Episcopal Church at its

1958 General Convention adopted a resolution in opposi

tion to the death penalty.

8. GENERAL BOARD OF CHRISTIAN SOCIAL

CONCERNS OF THE UNITED METHODIST

CHURCH

The General Board of Christian Social Concerns is an

instrumentality of the United Methodist Church. Its pur

pose is to further the works of the church in the sphere

of social affairs. The United Methodist Church at its 1960

General Conference adopted a statement opposing the

death penalty. The statement was revised in 1964 and is

now part of United Methodist Social Policy. The United

Methodists number 11,000,000 members among their 38,000

churches which are situated in every state.

9. GREEK ORTHODOX ARCHDIOCESE OF

NORTH AND SOUTH AMERICA

The Greek Orthodox Church expresses the belief that

every person should be afforded every opportunity to

establish his innocence. If he is found guilty, he should

be afforded every opportunity to present what evidence

he can to mitigate his guilt. The Greek Orthodox Church

consists of 500 parishes, largely in the United States and

Canada, and some in Central and South America. The

membership of the Church is 1,500,000.

•— 7 —

10, THE AMERICAN ETHICAL UNION

The American Ethical Union is a federation of the Ethi

cal Culture Societies and Fellowships in the United States,

which, collectively constitute a liberal religious humanist

fellowship known as the “Ethical Movement” or the “Ethi

cal Culture Movement,”

The first Ethical Culture Society was founded in New

York City in 1876 by Dr. Felix Adler. There are today 24

Societies and Fellowships of the American Ethical Union

in ten states and the District of Columbia. The American

Ethical Union is a member of the International Humanist

and Ethical Union, a world-wide organization, with head

quarters in Utrecht, The Netherlands. Religious humanists

oppose the death penalty. The American Ethical Union

has adopted policy statements calling for its abolition, and

Members and Leaders (Ministers) of Ethical Culture So

cieties have been active and, in many instances, in the fore

front of organized efforts to have the death penalty

abolished throughout the United States.

11. THE UNITED PRESBYTERIAN CHURCH IN

THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA BY MRS.

RALPH M. STAIR, MODERATOR AND

WILLIAM P. THOMPSON, STATED CLERK

OF THE GENERAL ASSEMBLY

The United Presbyterian Church adopted a statement

condemning the death penalty at its 171st general assembly

in 1959 and adopted a revised statement at the 177t,h Gen

eral Assembly in 1965.

The United Presbyterian Church in the United States of

America has a membership of 3,100,000. It has 8,662

churches throughout the nation.

12. NATIONAL CATHOLIC CONFERENCE FOR

INTERRACIAL JUSTICE

The National Catholic Conference For Interracial Jus

tice is a service agency formed in 1960-61 out of the

Catholic Interracial Council movement. It is an indepen

dent “lay” agency, not an official Church agency, though it

is recognized by the Church and maintains close relation

ships with official national Roman Catholic agencies, with

the leaders and structures of many local dioceses, and with

a large number of religious orders of men and women.

Much of the energy of the Conference is devoted to mov

ing the Catholic community more deeply into the struggle

for interracial justice, and for the disadvantaged, and into

cooperative work with other denominations and secular

agencies. The Conference initiated, organized and served

as secretariat for the historic 1963 National Conference

on Religion and Race, involving some 70 denominational

groups.

The Conference offers specialized services in the fields

of employment (Project Equality), education, urban ser

vices and is initiating a new project in the field of religious

ministries to the police. It serves over 150 human relations

and urban service organizations sponsored by the Roman

Catholic community.

— 9 —

13, THE NATIONAL COALITION OF

AMERICAN NUNS

The National Coalition of American Nuns is an organi

zation of Roman Catholic Sisters whose purpose is to

study and speak out on issues related to human rights and

social conscience. The coalition was established in July,

1969. It numbers 1,937 sisters.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

The death penalty is a cruel and unusual punishment

because of the inherent fallibility of every judicial pro

ceedings. There is the possibility of the execution of an

innocent man. Every stage and every aspect of the judi

cial proceedings reveal the wrong we do when we take

human life by judicial process: we permit the defendant

to plead and bargain with his own life as a counter; we

force a scrupled juror to consider a penalty he disavows.

The outcome of a trial sometimes depends on chance fac

tors such as the availability and admissibility of evidence;

life or death may depend on determination of complex

subjective questions such as motive or the voluntariness

of a confession. The judicial rules, substantive and pro

cedural, are shifting: men have been executed on the

basis of rules shortly changed. The death penalty some

times is employed as a form of suicide; thus, instead of

decreasing murder, it may increase it. The treatment of

the condemned man, the wait, the setting of death dates

and granting of stays all inflict unbearable torture. The

execution itself is ghastly.

The evils of the death penalty are not remediable. They

are inherent and can end only with the end of capital

punishment.

— 10 —

ARGUMENT

I.

THE PUNISHMENT OF DEATH IS CRUEL

AND UNUSUAL

The religious organizations support petitioners in the

case at bar and three companion cases. In view of the cer

tiorari grant, the religious organizations will consider pri

marily the impact of the death penalty upon the individual.

Its impact upon society we shall mention only inciden

tally. Yet we should note that some of the most telling ar

guments against capital punishment stress its negative so

cial effects. Study after study has shown that it fails as a

deterrent.1 The death penalty is a costly waste of money,

because it protracts trials, increases the number of appeals

and increases custodial expense. It corrodes and brutalizes

society. Some aspects of this process we shall touch on.

We assert that the death penalty for any crime is cruel

and unusual punishment within the meaning of the Eighth

Amendment. We focus on the death penalty for murder,

but our arguments apply generally with equal force to the

death penalty for rape and other crimes.

In brief compass our contention is that life ought not to

stand forfeit upon human judgments. Such judgments are

necessarily fallible. This proposition we think is true at

every level of the judicial process: the defining of capi

tal crimes, the making of factual determinations, the weigh

ing of subjective factors such as motive, capacity and men

tal status. No judge and no jury is without bias; no judi

cial proceedings exempt from flaw.

1 For representative studies, see Bedau, The Death Pen

alty in America, Chap. 6, p. 258, et seq. (hereafter “Be

dau”).

— 11 —

We shall review pending and recent cases, not primarily

for the legal principles they enunciate, but for the lessons

they teach regarding the limitations of the judicial process

and of man himself.

Our thesis does not rest simply on the argument often

cited for abolition of the death penalty—the possibility of

judicial error. I t is, of course, beyond cavil that a man

wrongly condemned has suffered cruel and unusual punish

ment. We need not speculate, moreover, on the possibility

of such a fearful miscarriage of justice: it has occurred.

On March 9, 1950, Timothy John Evans was hanged in

London for the murder of his wife and baby, his appeal to

the Court of Criminal Appeal having been dismissed (Feb

ruary 20, 1950). A witness against him was his landlord,

John Reginald Christie. In 1953, the bodies of Mrs. Chris

tie and several others were found on the premises. Christie

was convicted of the murder of Mrs. Christie and hanged.

Doubts immediately arose as to the guilt of Evans.1 On

October 18, 1966, Queen Elizabeth II granted Evans a post

humous pardon.2

Ordinarily, following an execution, there is no longer sus

tained interest in a case. If an injustice has been done, it is

beyond recall. The legal remedies for post death exonera

tion are ill-defined. Hence, there are but few cases of official

1 For the transcript of both trials, see Trials of Timothy

John Evans and John Reginald Hcdliday Christie, Jesse

ed., Notable British Trials (Hodge and Co., Ltd., 1957).

The judgment of the Court of Criminal Appeal in Rex v.

Evans appears at p. 297. Christie did not appeal.

2 New York Times, October 19, 1966, p. 19, Col. 3.

12

recognition of judicial error. Nonetheless, there is exten

sive literature regarding wrongful convictions in both capi

tal and noncapital cases.1 If we continue executions, doubt

less we shall again put to death innocent men.

But our argument is more comprehensive. We think it

cuts deeper, that it reveals the inherent limitations of the

judicial process, particularly in capital cases. Let us look

to the various stages and aspects of the criminal trial to

explore more fully its pernicious effect.

The very existence of the death penalty gives the prose

cution an enormous advantage. Often, in exchange for a

plea of guilty, the prosecution will drop a demand for a

death sentence. The defendant faces a fearful choice: shall

he hazard his life to seek acquittal? Yet the defendant

usually does not know precisely the strengths or the weak

nesses of the prosecution’s ease, and, consequently, lacks

full knowledge necessary for an informed decision. Even

if we had full pre-trial discovery in criminal proceedings,

as we do in civil proceedings, the defendant would not be

in a position to predict with precision the outcome of the

trial. The outcome of every trial is uncertain.

For the defendant to make a “rational” decision when he

bargains with the prosecution, the issue is not whether he is

in fact “innocent” or “guilty” but rather what is the proba

bility that he will be found guilty or not guilty. Thus, the

innocent defendant cannot afford to dismiss the negotiating

process without taking a cold and calculating look at the

strength and weakness of his case as it wdll be viewed by

the court and jury. The defendant who is “guilty”’ must do

the same. And so must the defendant who does not know

1 See MaeNamara, Convicting the Innocent, 15 Crime and

Delinquency 57 (1969).

13

whether he is “innocent” or “guilty”. (Thus, suppose a

possible defense of mental incompetency or self defense.)

The defendant may be called upon to make a crucial deci

sion even though woefully ill-equipped to do so.

The death penalty is for some, not a punishment for

murder, but a punishment for refusing to plead guilty to

murder.1

Indeed, there is the grim possibility that a prosecutor

who threatens to ask for the death penalty as a device to

obtain a plea of guilty may feel forced to make such a de

mand if the defendant insists upon trial. In such case the

death penalty may be sought not because the prosecutor

feels that it is appropriate, or that he wishes it, but as an

unfortunate concomitant of an unsuccessful negotiating

session.

"We are aware of the decisions in North Carolina v. Al

ford, 400 U.S. 25 (1970) and Brady v. U.S., 397 U.S. 742

(1970) upholding pleas of guilty against claims that they

were induced by fear of the death penalty. The Eighth

Amendment question here at bar, however, was not there

before this Court. The defendants there did not receive

death sentences. Here, the broader issue, in light of the

certiorari grant, is the death penalty as such. Its use as a

coercive tactic to obtain guilty pleas, and its imposition

where the defendant declines to plead guilty and hazards

trial, present issues different from Alford and Brady,

The moral conflict of the scrupled juror. We move to the

jury selection stage of the trial. The decision of this Court

in Witherspoon v. Illinois, 391 U. S. 510 (1968) bars exclu-

1 In Illinois we are aware of but one case in recent years

where a capital sentence was imposed upon a plea of guilty,

People v. Wilson, 29 111. 2d 82, 193 N E 2d. 499 (1963).

Wilson was not, however, executed.

— 14

sion of veniremen simply because they have conscientious

scruples against the death penalty. Assuming that such

prospective jurors are not removed by peremptory chal

lenge by the prosecution, such jurors are faced with a moral

dilemma of substantial proportions. In what circum

stances should they lay aside their scruples in order to en

tertain or impose a punishment which they think morally

wrong?

We point up this dilemma not to criticize Witherspoon.

Many of the religious organizations participating in this

amicus brief participated as amici in Witherspoon. We

think that a jury selected by the Witherspoon standard is a

fairer jury than one selected by the former rule. It does

not, however, contain a full cross section of the public,

since it excludes those with fixed and unchangeable scruples.

Moreover, when a Witherspoon jury is composed wholly or

partly of those holding scruples less fixed, a death verdict

will be returned only where scruples are overcome.

The trial: the role of chance. We turn to the evidentiary

phase of the criminal trial. A criminal trial is a search for

the truth, but a stylized search conducted pursuant to rules.

In the generality these rules operate insofar as possible to

secure reliable, trustworthy evidence. But the very rule that

operates to the advantage of one defendant can work to the

disadvantage of another who may be on trial for his life.

Assume a defense of alibi. If the alibi witness dies before

trial, the defense collapses. If the witness lives, but hap

pens himself to have a criminal record, his credibility may

be destroyed and no doubt the alibi defense will fail.

Much may depend upon whether crucial evidence has

been preserved and whether it is still available to counsel

for the defense. This in turn may depend upon how soon

after the crime counsel was obtained or it may depend upon

15 —

sheer matters of chance. In the fairest of trials fortune

plays a large role, favoring now the prosecution and noAV

the defense. Given the most skilled and diligent attorney,

the most learned and fairest of judges, the most able of

juries, the outcome of a criminal trial may nonetheless be

determined by the fall of chance.

In civil litigation the parties have full opportunity to ex

plore, in advance of trial, the opposite party’s case. In

criminal trials, while the scope of discovery has expanded

recently, it is generally less extensive. The defendant may

be informed of the witnesses who may be called, but often

has no way to compel them to reveal in advance what their

testimony may be. True, the law directs the prosecution to

reveal evidence favorable to the accused. But unless the

defendant learns of the suppressed evidence by fortuitous

events, these rules are difficult to enforce.

In the battle, the state has a full range of technical and

scientific resources. The defendant usually is granted no

such assistance.

Today, skilled representation is rarely enough. Success

ful defense often requires not only skilled counsel, but also

a corps of pathologists, chemists, physicians and other ex

perts, if a crime is to be thoroughly explored and a full de

fense presented. Yet the state usually provides none of this

for the accused. The facts generally must be dug out by

counsel.

The trial: subjective determinations. The determination

of “objective facts” in a trial is a baffling undertaking. Ad

ditionally, nearly every trial requires a determination of

the subjective mental state of the accused, sometimes as

to several issues. We know so little of the science (or art)

of making such a determination that life should not stand

forfeit through them.

— 16

Let us consider a case in this Court, Alcorta v. Texas.

355 U. S. 28 (1957). Alcorta came upon his wife one eve

ning in a parked car kissing Castilleja. Alcorta killed his

wife. The ease came up under the law of Texas, under

which, if Alcorta was guilty of murder without malice (a

murder arising from “a sudden passion from an adequate

cause”), the maximum penalty was five years. The jury,

however, found Alcorta guilty of murder with malice. The

sentence was death. The jury sat in judgment essentially

on a subjective issue: What was Aleorta’s reaction to the

scene in the car? Or, perhaps more precisely, what should

have been the limits of his reaction had he been a reason

able man? The issue was decided unfavorably to Alcorta.

The difference was not only the difference between life and

death, but the difference between a relatively mild sentence

and death. Was the jury aware fully of the social group in

which the Alcortas lived? Was Mrs. Alcorta’s conduct re

garded as heinous in that group? We do not know; we do

not know whether the jury knew.

There is another element in the case: At the trial Alcor

ta testified that he had reason to believe that his wife had

been intimate with Castilleja. Such testimony of course

raises a new area of inquiry. How “reasonable” were Al-

corta’s suspicions? In the actual ease it turned out that

Castilleja had informed the prosecution that he had in fact

been intimate with Mrs. Alcorta and accordingly Alcorta’s

suspicions were well founded. This fact was not presented

to the court and jury and, indeed, Castilleja denied having

any more than a casual relationship with Mrs. Alcorta. Be

cause of this act of deception, Alcorta’s conviction was up

set by this Court.

The Alcorta jury was asked to make not an objective but

a subjective determination. Subjective determinations take

17

a myriad of forms: Suppose, for example, a defense of

justification. What is a “reasonable belief” that force was

necessary in self defense? The defense of insanity and the

defense of incapacity to form a specific intent are other il

lustrations.

The question of subjective determinations may be viewed

from another perspective. The Commandment is “Thou

shalt not kill.” But not all who kill are equally culpable.

The law establishes gradations of homicide. These grada

tions are variously phrased from state to state (“degrees”

of murder, etc.). Similarly, there are various defenses, like

wise variously described. The law necessarily compresses

these gradations and defenses into a few categories. But

the circumstances of life are manifold, the causes of each

homicide as complex as human personality itself.

The voluntariness of confessions. Determining the volun

tary character of a confession, of course, requires a subjec

tive determination. A jury is asked to judge in the quiet of

the court room the effect of a given interrogation upon a

man whom they do not know. They learn of him as a

person only through the testimony of partisan witnesses,

given under the stress of trial relating to events which

almost invariably are hotly disputed. Consider the case

of Charles Townsend. He was first arrested on a murder

charge on January 1, 1954 and has been incarcerated con

tinuously since then. He has been on death row for 16

years, 4 months (since April 7, 1955). His case is now

the oldest case in the nation. Counting from his first

arrest, it is probably the longest capital case in American

history (17 years, 7 months). His ease was last in this

Court in 1963 (Townsend v. Sain, 372 U.S. 293).

Townsend was convicted of murder and sentenced to

death by the Criminal Court of Cook County. Characteriz-

— 18

ed by the prosecution as a near mental defective, he was

arrested one evening and soon began to sutler withdrawal

symptoms. A prison physician administered scopolamine,

a drug commonly known as “truth serum.” Within an hour

and a half after the administration of this drug Townsend

confessed to four murders and two robberies. He was tried

for one murder and acquitted. He was then tried for the

second murder and sentenced to death. The evidence of his

guilt, apart from the confession, was simply that one Camp

bell testified that about the middle of December (the

murder took place on December 18, 1953), he saw Town

send walking down the street in the vicinity of the murder

with a brick in his hand. A pathologist testified that death

was caused by a severe blow to the head of the deceased.

The Supreme Court of Illinois affirmed the conviction de

spite the meagerness of the evidence. Two dissenting jus

tices declared the testimony inherently incredible. Town

send, through counsel serving without fee, then sought re

lief in the federal court charging that the state suppressed

the fact that the drug scopolamine, which its witnesses re

ferred to as hyoseine, was known as truth serum. After

numerous appellate proceedings, this Court directed that

the District Court give Townsend a hearing.

Further litigation ensued. Only this year, the District

Court, for a second time, set aside Townsend’s conviction

and ordered his release on bond. U. 8. ex rel Townsend v.

Twomey, 322 F. Supp. 158 (1971). (The Seventh Circuit

has stayed the bond release order.)

The second oldest case on death row is the case of Edgar

Smith. Smith ^vas sentenced to death on June 4, 19'57, for

the murder of a 14 year old girl. For years he fought

vigorously in the courts to set aside his conviction. (For

unsuccessful attempts, see U. S. ex rel Smith v. New Jer-

— 19 —

sey, 322 Fed. 2d 810 (CA 3rd, 1963) and V. S. ex rel Smith

v. Yeager, 395 Fed. 2d 245 (CA 3rd, 1968). (Judge Biggs

dissented from the denial of a plenary hearing and Judge

Freedman from the denial of a rehearing en banc. The

course of the litigation is traced in 395 Fed. 2d at 247).

On June 8, 1971, the United States District Court for

New Jersey, after a plenary hearing, overturned the convic

tion. Smith was ordered released on bond (Chicago Sun

Times, June 9, 1971, p. 18). The Third Circuit, on an

expedited appeal, affirmed the order setting aside the

conviction, but declined to release Smith on bond.

Perhaps the State will seek certiorari. The merits of the

case need not concern us. What must give us pause is that

after 14 years a court has ruled that Smith was unjustly

convicted. Had he been executed, the error could not have

been righted.

The District Courts in both Townsend and Smith entered

bond release orders. These orders illustrate another aspect

of the death penalty: Once a defendant wins the right to

a retrial, his case often is seen in a new perspective. The

crime itself is no longer viewed as one warranting the death

penalty, or the quantum of evidence of guilt seems di

minished. Other illustrations: James V. Giles and John G,

Giles, not long after the decisions of this Court (Giles v.

Maryland, 386 U.S. 66 (1967)) and the Maryland Court of

Appeals, State v. Giles, 245 Md. 342, 227 Atl. 2d 745 (1967)

were ordered released on $10,000 bail pending retrial. (N.

Y. Times, July 6, 1967, p. 27). Edgar Labat and Clifton A.

Poret, sentenced to death for rape in 1953, won a retrial.

Labat v. Bennett, 365 Fed. 2d 698 (CA 5th 1966). In 1969,

they pleaded guilty to aggravated rape and were sentenced

to the 16 years, 9 months already spent on death row. (N.

Y. Times, December 30, 1969).

We have emphasized the subjective elements of every

trial. We do not wish to rule out subjective determinations

in criminal trials. There is a difference recognized by the

law and recognized by mankind generally between a homi

cide committed as the law used to say, “with malice afore

thought” and a homicide committed innocently or negligent

ly or even recklessly. Surely different punishments are in

order for these various crimes. But we say, questions of

human motivation, responsibility, ability to withstand in

terrogation, effects of narcotics and alcohol upon the human

system, etc., are matters of extraordinary complexity.

Medicine generally, and psychiatry in particular, have been

able to supply only a feeble light in some areas of these

problems. We can, it seems to us, in good conscience recon

cile ourselves to the necessity for the resolution of these

questions as best they can be resolved by a court or by a

jury. Such resolution is necessary as part of the price of

human society. But we are tragically in error when we rest

decisions of life and death upon these fallible judgments.

We exact a price from the individual which society does

not. need for its protection.

In past years, with unconscious irony, but in light of

what we have said, not without justification, the Govern

ment used to classify executions among the accidental

deaths. (See Statistical Abstract of the United States,

1951, Table 74, p. 69, Footnote 12 for 1900, 1910 and 1920.).

Today they are classified among “homicides” by the United

States Public Health Service. (Statistical Abstract of the

United States, 1970, table 220, p. 145).

Shifting judicial rides, substantive and procedural. We

turn to another area: shifting judicial concepts of the capi

tal crime. The Caryl Chessman case is an illustration. (For

a procedural aspect of the case, see Chessman v. Teets,

21

354 U. S. 156 (1957)). Chessman was sentenced to death

not for murder—he killed no one—but for “kidnapping”

during an armed robbery in which the victim suffered bodi

ly harm.

The Supreme Court of California declared that, “It is the

fact, not the distance, of forcible removal which constitutes

kidnapping . . .” (People v. Chessman, 38 Cal. 2d 166 at

192, 338 P. 2d 1001 (1959)). Nine years after Chessman was

executed in 1960, the Supreme Court of California dis

affirmed this construction of the statute (■People v. Daniels,

71 Cal. 2d 1119, 80 Cal. Kept. 897, 459 P. 2d 225 (1969).

For the latest development see People v. Mutch, 93 Calif.

Kept. 721, 482 P. 2nd 63 (March 24, 1971).

For an analogous shift in the law, but procedural, rather

than substantive, consider the ease of Vincent Ciueei. The

state alleged that Ciucci shot his wife and three children in

order to marry another woman. The state elected not to

try Ciucci for all four murders simultaneously. Instead he

was first tried for the murder of his wife for which he re

ceived a sentence of twenty years. He was then tried for

the murder of one child for which he received a sentence

of 45 years. Not until he was tried for the murder of the

second child did he receive the death penalty, the goal

sought at the beginning by the state. This Court in a five

to four decision declared that under Illinois law each mur

der was a separate crime for which Ciucci constitutionally

could be indicted and tried separately. (Ciucci v. Illinois,

356 U.S. 571 (1958)). Ciucci was executed in 1962.

Not long afterward the Supreme Court of Illinois dis

approved the practice challenged in Ciucci. People v. Gol-

son, 32 111. 2d 398, 207 NE 2d 68 at 75 (1965).

Indeed, even before the execution of Ciucci, Illinois, in

1961, adopted a criminal code requiring that all offenses

— 22

known to the prosecuting officer must he prosecuted in a

single prosecution. Illinois Rev. Stats. (1971) C.38, <§§

3-3 (b), and 3-4). (See the comment of the Joint Commit

tee to Revise the Illinois Criminal Code which appears after

Section 3-3 in Smith-Hurd Illinois Statutes Annotated).

Recent death penalty cases in this court: due process

aspects. In recent years this Court has had before it four

cases challenging procedural aspects of capital cases. With

erspoon v. Illinois, 391 U. S. 510 (1968); Maxwell v. Bishop,

398 U.S. 262 (1970); McOautha v. California, 29 L. ed. 2d

711 (1971) and Crampton v. Ohio, 29 L. ed. 2d 711 (1971).

Every one of these cases raises grave due process ques

tions apart from the issues presented in this Court.

Consider Witherspoon. In 1963, when the Illinois Su

preme Court upheld Witherspoon’s death sentence, it

granted the request of his court appointed attorney to be

relieved of further responsibility. Witherspoon thus was

facing the chair with substantial legal channels still open

and a right to seek clemency, but without a lawyer. This

Court declined a request to appoint counsel. Witherspoon

applied to the Illinois Supreme Court to appoint counsel.

It promptly did so but the 90 days allowed by law for cer

tiorari had expired. Witherspoon obtained other counsel

who conducted a protracted battle in his behalf. After these

attorneys had exhausted their efforts, Witherspoon, still

under sentence, from his prison cell wrote his own petition

which he mailed to the Federal District Court. The District

Court appointed counsel to represent him. They success

fully carried the case here. This Court declared Wither

spoon’s death sentence indeed unlawful and ultimately the

Supreme Court of Illinois reduced the sentence to a prison

term.

For Maxwell, it was a substantial struggle to obtain the

right to appeal from the denial of Federal habeas relief

23

and to stave off execution long enough for the case to be

heard.

The District Court denied a certificate of importance and

a stay of the execution then set for September 2, 1966. The

Court of Appeals declined to grant a certificate or a stay.

Mr. Justice White granted a stay late in the evening on

September 1. During the October Term, 1966, this Court

ordered the Court of Appeals to consider the ease. It did

so but denied relief. (See 385 U. S. 650 (1967), 398 Fed.

2d 138 at 140 (1968)). Ultimately the case reached this

Court (393 U. S. 997 (1968)) raising the two questions later

to be decided in McGautha and Crampton. This Court,

however, did not pass upon those issues, but rather remand

ed the case to the lower courts for resolution of Wither

spoon questions.

In McGautha there is a question whether McGautha or

his co-defendant, Wilkinson, fired the fatal shot. (Me-

Gautha, 29 L ed. 2d at 715). The Courts below appear to

have resolved this issue against McGautha and evidently

on this basis Wilkinson received a prison term, whereas

McGautha received the death penalty. Suppose, however,

as McGautha claims, the Courts are wrong? Suppose that

Wilkinson fired the fatal shot but falsely accused McGautha

in order to save himself?

The Crampton case is an incredible story. Crampton

spent years in prison. In September 1967 Crampton’s wife,

because of bis amphetamine addiction, bizarre behavior,

and knife threats to her, persuaded him to commit himself

to a state mental hospital. In November, 1967, a state hos

pital physician noted on the chart: “Prognosis: Guarded.

Dangers and Warnings: Under stress, patient could be

dangerous to his wife.” (R. p. 20 in Crampton, 0. T. 1970,

No. 204). Nonetheless, wdthin a month he was sent home on

24 —

Christmas furlough. He overstayed the furlough. Ap

parently the authorities did not bother to pick him up. He

threatened his wife; the police picked him up but released

him. By January 17, 1968, he had murdered his wife. Yet

a. defense of insanity was rejected. What measure of re

sponsibility does the state bear for the death of Mrs.

Crampton?

Near the end of the last term this Court set aside the

death sentences and remanded for reconsideration several

cases in light of Witherspoon. Some of these cases too are

profoundly disturbing apart from Witherspoon questions.

Witherspoon itself declared that it was retroactive.

Several capital defendants had eases on appeal to the Su

preme Court of Tennessee. They sought to raise Wither

spoon, but the 90 days then allowed by statute for filing

bills of exceptions had expired. The Supreme Court of

Tennessee affirmed the convictions without considering

Witherspoon, even though it promulgated a constitutional

rule. Apparently there was no way to raise the issue in the

Tennessee Courts. Upon amendment of the statute, this

Court, on certiorari, remanded for reconsideration, Hunter

v. Temessee, ...... U.S......... (June 28, 1971).

In Tajra v. Illinois and Bernette v. Illinois, ...... U.S.

...... 39 L. W. 3566 (June 28, 1971) Martin Tajra and

Herman Bernette were indicted for murder. It was the

state’s theory that Tajra had provided Bernette with a

gun and sent him to carry out a robbery. Bernette entered

the premises and in the course of the robbery committed a

murder. Tajra and Bernette were tried separately. Tajra,

sentenced to a prison term, appealed to the Illinois Ap

pellate Court. Bernette was sentenced to death. On appeal

to the Supreme Court of Illinois that Court reversed and

remanded Bernette’s conviction for various trial errors.

25

People v, Bernette, 30 Til. 2d 359, 197 N E 2d 436 (1964).

On Tajra’s appeal to the Illinois Appellate Court, that

Court held that since the same errors had occurred in

Tajra’s trial as in Bernette’s, he too was entitled to a new

trial. People v. Tajra, 58 111. App. 2d 479, 208 N E 2d 9

(1965).

On the second trial, Tajra was sentenced to death. This

conviction was appealed to the Supreme Court of Illinois

which did not exercise its power to reduce the sentence to

a term of years. People v. Bernette et ah, 45 111. 2d. 227,

258 N E 2d 793 (1970).

Bernette, ..... U.S....... , 39 L. W. 3566 (June 28, 1971),

a black, is a mental defective. Sometime after his convic

tion he became mentally ill and since January, 1968, has

been confined in an institution for the mentally ill. None

theless, the Supreme Court of Illinois about 18 months

after he had been removed to a mental hospital affirmed

his conviction for murder. No note was taken, apparently,

of the fact that he had been in a mental, institution, nor

did the Supreme Court exercise its prerogative to reduce

the sentence. People v. Bernette, 45 111. 2d 227, 258 N E 2d

793 (1970).

Prosecution suppression of evidence favorable to accused.

The Lyman Moore case now before this Court on certiorari

Moore v. Illinois (cert. gr. June 28, 1971 No, 69-5001) is

an instance where the prosecution was aware of but failed

to reveal to defendant evidence favorable to him. Moore,

now under sentence of death for murder, was arrested for

the crime some months after it took place. In the interim

the police sought one “Slick” who had boasted of the murder

to a bartender shortly after the crime. The bartender in

formed the police that prior to the boast, he had seen

“Slick” at a time when the defendant was in a Federal

prison. Yet this information was never revealed to defense

counsel. Had this information been revealed, the bartend

er’s identification of the defendant as “Slick” would have

been shaken. This fact, coupled with substantial evi

dence that at the time of the murder Moore was at work

in a distant portion of the Chicago area might have meant

acquittal. (See further the amicus brief filed by present

counsel in the Moore case).

It seems almost past belief that the prosecution would

suppress evidence favorable to an accused in a criminal

case. Yet there have been repeated instances of such prac

tice even in capital cases. See e.g. Miller v. Pate, 386 U. S.

1 (1967). (False representation of paint stains on shorts

as blood) Brady v. Maryland, 373 TJ. S. 83 (1963). (State

ment of accomplice that he, not defendant, had shot deceas

ed); U. S. ex rel Thompson v. D'ye, 221 F 2d 763 (CA 3rd

1955), cert, den., 350 U. S. 875 (1955). (Officer testified that

defendant was not drunk. Prosecution suppressed contrary

testimony of other officers). U. 8. ex rel. Almeida v. Baldi,

195 F. 2d 815 (CA 3rd 1952) cert. den. 345 U. S. 904 (1953)

(Prosecution permitted false inference that defendant fired

fatal shot); Ashley v. Texas, 319 F. 2d 80 (CA 5th 1963),

cert. den. 375 U.S. 931 (1963) (State failed to reveal medi

cal report that defendant was incompetent); TJ. 8. ex rel

Meers v. Wilkins, 326 F.2d 135 (CA 2d 1964) (Robbery.

Prosecution failed to produce eyewitnesses who stated de

fendant not the robber).

Barbee v. Warden, 331 F2d 842 (CA 4th, 1964) (Prose

cution permitted false inference that defendant’s gun was

the lethal weapon); Turner v. Ward, 321 F2d 18 (CA 10th,

1963) (Suppression of nature of sex attacks); TJ. S. ex rel

Butler v. Maroney, 319 F2d 622 (CA 3rd 1963) (Suppres

sion during guilt phase of trial of evidence that a struggle

— 27 —

preceded shooting); Levin v. Katzenbach, 363 F2d 287

(D. C. Cir. 1966) (Bank officer’s knowledge of key incidence

suppressed); McMullin v. Maxwell, 3 Ohio St. 2d 160, 209

N E 2d 449 (1965) (Suppression of favorable ballistics

report); Application of Kapatos, 208 F. Supp. 883 (N. Y.

1962) (Witness’s statement that defendant not the

murderer); U. 8. ex rel Montgomery v. Hagen, 86 F. Supp.

382 (1949) (Rape case. Suppression of medical report that

no rape occurred.)

The four cases at bar: due process aspects. The four

cases here at bar raise troublesome questions apart from.

Witherspoon and apart from the Eighth Amendment ques

tion. These questions are set out in the petitions for cer

tiorari. Here we will but mention that Aikens waived jury

trial at a time when scrupled jurors would have been ex

cluded. Jackson and Branch were sentenced to death for

rape. Both are black; both victims, white. Furman and

Jackson were sentenced to death after unitary trials. Now

the unitary trial in Georgia has been replaced by a two

stage trial. (Brief for Respondent in Opposition to Peti

tion for Certiorari, p. 10, in Jackson). Thus the trials of

both Furman and Jackson, apart from McGautha, no

longer meet Georgia standards. Should they go to their

deaths? Furman’s trial lasted but a day.

We have mentioned above the development of the crimi

nal law. Only a generation ago, Illinois executed two men

without any appellate review. At that time, Illinois law

granted a right of review in the Supreme Court of Illinois

to everyone convicted of a felony, except -in capital cases.

In such cases, review was only by leave of Court. 111. Rev.

Stats. (1951), C. 38, 769 and 769.1. Review was denied

to Willard Truelove, and on November 17, 1950, comatose,

he was dragged to the electric chair at the Cook County

— 28 —

Jail. Harry Williams similarly was denied review and

denied a hearing on the constitutionality of the discrimi

nation. (342 U.S. 934 (February 4, 1952)). He was exe

cuted on March 14, 1952.

The very next year the law was changed. 111. Rev. Stats.

(1953) C. 38, § 769.1. Today would we for a moment coun

tenance execution without appellate review? What practi

ces today considered just will we regard tomorrow as a

barbarism and wonder that they persisted so long?

The death penalty mid suicide. The death penalty raises

another deeply disturbing problem. There appear to be

some individuals who commit murder in order to receive

the death sentence. They ask the state to do for them what

they hesitate to do for themselves. In these situations, the

death penalty, rather than discouraging murder, appears

actually to encourage it. We do not, have to speculate as to

whether such cases arise. This Court has had first hand

experience with the matter. Rees v. Peyton, 384 TJ. S. 312

(1966) is such an instance. Rees was sentenced to death.

At sentencing Rees said to the judge, “Thank you.” Coun

sel sought review here on certiorari. After the petition had

been filed, Rees wrote to this Court and to counsel asking

that the petition be withdrawn and all legal efforts halted.

The Court ordered inquiry into Rees’s mental status.

Another illustration: In 1957, Jack Chester after a long

upsetting love affair, killed his fiance. His death sentence

was upheld by the Supreme Judicial Court. (Common

wealth v. Chester, 337 Mass. 702, 150 N E 2d 914) on June

10, 1958. The sequel is related by Hr, Frederick Wiseman:

“Chester, aware of commutation efforts on his behalf, wrote

to the Governor asking that clemency be denied. He want

ed death, not as punishment but as mercy.” The responsible

authorities recommended commutation. “When told that

— 29 —

the Governor was about to approve their recommendations,

[Chester] hanged himself.” (Wiseman, Psychiatry mid

Law, Use and Abuse of Psychiatry in a Murder Case,”

American Journal of Psychiatry, Oct., 1961, p. 289.

Other recent cases in which a condemned man sought

execution are set out in the footnote.1

The condemned man, the wait and the execution. In the

foregoing pages, we have said much about the criminal

proceedings but little about the condemned man. How does

he fare? As of December 31, 1968, the median elapsed time

for prisoners then under sentence was 33.1 months (NPS

1 Andrew' Pixley filed a plea of guilty to a murder

charge. Upon being sentenced to death, he stated he did

not wish to appeal. After his attorneys nevertheless filed

an appeal, he wrote to the Wyoming Supreme Court that

he wanted no appeal and wished the attorney dismissed

{Pixley v. State, 406 P. 2d 662, at 665, October 19, 1965).

The Court heard the appeal nonetheless and affirmed.

Pixley was executed on December 10, 1965.

James Donald French, a prisoner, strangled his cell

mate. After he was sentenced to death, counsel filed an

appeal. Judge Bussey in a concurring opinion stated the

defendant “has urged this Court to dismiss his appeal and

allow him to be executed, in accordance with the judg

ment and sentence imposed upon him.” French v. State,

377 P. 2d. 501 (Oklahoma, 1961). The Court nonetheless

reversed. A second conviction likewise was reversed. 397

P. 2d. 909 (Oklahoma, 1963).

At the third trial, French “freely admitted the bizarre

details of the slaying . . . and described in minute detail

the facts and circumstances. . . .” 416 P. 2d. 171 at 178

(Oklahoma, 1966).

After the third conviction, French wrote to the Clerk of

the Supreme Court asking that his court appointed at

torney be relieved. French was executed August 10, 1966.

For earlier accounts where capital punishment has been

employed as a form of suicide, see Sellin, The Death Pen

alty 65 (1959).

30 —

Capital Punishment Bulletin, No. 45, August 1969) (Latest

published). In Maryland the median was 79 months (the

longest) and in Ohio and Kentucky, 16 months (the short

est). Doubtless these medians have since lengthened. But

these statistics do not convey the full horror. Generally

it appears that men on death row are kept segregated,

usually in small cells a few yards from the execution

chamber. They do no work. Their opportunities for ex

ercise and recreation are limited.1 For years a. living hu

man being is treated as if dead. He is no longer func

tionally a member of the community of the living. He

lives thus for months or years. Under this regimen some

men cease to be men.2 But the condemned is not allowed

to end his suffering himself.3 The moments preceding the

execution are horrible.4 The execution itself ghastly.6

1 The routine at San Quentin is described by a con

demned man in N. Y. Times, July 23, 1971, p. 31. For the

routine in New Jersey and New York, see N. Y. Times,

May 5, 1971, p. 41.

2 See Gottlieb, Capital Punishment, 15 Crime and Deling.

8 (1969).

3 Rigid suicide precautions are customary. Gottlieb, Cap

ital Punishment, 15 Crime and Delin. 8 (1969). Amici

Synagogue Council, et ah, in Maxivell v. Bishop, 0. T.

1969, No. 13, make the point that the state insists not on

death but on the opportunity to put to death a man aware

of the event. The sick are cured and insane, if possible,

brought to lucidity to achieve this end. This is not punish

ment but vengeance.

4 Aaron C. Mitchell, the last man executed in California,

we are told, was carried moaning to the gas chamber. His

last audible words were, “I am Jesus Christ.” (N. Y.

Times, April 13, 1967, p. 13; Chicago Tribune, April 13,

1967, Sec. 1, p. 8).

5 See Thomas Gallagher, Invitation to a Killing, N. Y.

Herald Tribune, February 7, 1965.

31

There is another matter we must touch on. Dostoevsky

relates the awful events of December 22, 1849, when he

and two comrades were led to the place of execution, or

dered to don the white execution shirts and tied to posts.

At the last moment, they were untied and informed that

the Czar had spared their lives and sentenced them to

penal servitude.1 Almost as unbelievable as the actual

event is the nearly incredible fact that it was carefully

planned by Czar Nicholas I personally. We would not

impose calculated anguish in this fashion as did an auto

crat, Yet in the course of granting a condemned man a

full measure of due process, we inflict a pain similar to

that inflicted on Dostoevsky. A man is condemned and an

execution date set. A stay is granted pending appeal. The

conviction is affirmed and a new date set. As the proceed

ings continue, there are new dates and new stays. We do

not for a single moment suggest that a condemned man

be denied every access to the Courts. The bitter experi

ence of the past makes clear that justice sometimes pre

vails only after many lost battles. But in the course of

doing justice we inflict agony. Not by intent, but by the

inherent nature of the system created to do justice,2

Summation. Before concluding, we must call attention

to the special problems of the cause eelebre. They subject

the judicial process to a peculiar torment, and, when

they are capital cases, raise doubts never wholly

dispelled. Sacco and Vanzetti, the Rosenbergs and

Chessman are cases known to all. Other cases are

causes eelebre in their region, although not known nation-

1 For an account of the event by Dostoevsky, see Mochul-

sky, Dostoevsky, His Life and Work, 140 (Princeton U.

Press, 1967).

2 For but one example, consider the cases of Labat and

Paret as related in Labat v. Bennett, 365 F. 2d. 698 (CA

5th, 1966).

— 32

ally. So long as we retain the death penalty, men will go

to the grave, not for what they have done, or perhaps

not solely for what they have done, but because of who

they are, or who the world thinks they are, or because

of the domestic or international passions of the times.

Initially we stated as our premise the inherent fallibility

of every judicial proceeding. We have traced a number of

recent cases to explicate that proposition. Yet one might

say that our thesis merely sets out a collection of dis

parate evils, each subject to remedy, some already rem

edied. This view misconceives the thrust of our argument.

If we correct the evils we see today, tomorrow we would

recognize further flaws in the proceedings of today. The

evils of today are manifest; they must give us pause:

the defendant’s plea bargaining with his own life; the

scrupled juror asked to lay aside his scruples to vote for

death; the possibility of exonerating evidence being lost or

simply excluded by the rules of evidence; the numerous

shocking instances of prosecution suppression of evidence

favorable to the accused; the unsureness in judging sub

jective questions; doubts as to the voluntariness of con

fessions; shifting definitions of capital crimes; shifting

concepts of due process; last minute stays of execution

followed by subsequent reversals; the sentencing to death

of mentally ill men. We could readily enlarge our list. To

day we would not countenance the execution of a man

without appellate review of his case. Tomorrow" the prac

tices of today will seem equally unthinkable. Progress

sometimes is slow; there is backsliding. Yet today we do

know7 more about man than we did; we venture to think

we are less ready to take life. Indeed, perhaps the decline

in executions, and more recent halt, is an indication of

our growing, awareness of our limitations.

— 33

Since 1930, we have executed 3859 persons. I t is sober

ing to realize that scarcely any of their trials would sur

vive review today. Witherspoon and Miranda doubtless

would fault the majority. The 3859 men and women we

submit have suffered cruel and unusual punishment.

Should we continue executions when their deaths are wit

ness to the error of the practice!

We mentioned early in our brief that the death penalty

corrodes and brutalizes us. The foregoing* account, we

think, reveals clearly the fashion in which the death pen

alty degrades us. It is not only in the imposition of the

penalty per se that we are degraded, it is also in the

wrong's we tolerate (some just mentioned) in capital cases.

It is not alone the condemned man who suffers a cruel

and unusual punishment; it is we as well, we in society,

who inflict a cruel and unusual punishment on ourselves.

In the sciences, man long ago learned that absolutes

elude him. Every advance of knowledge teaches that the

world is more subtle than we thought. In the macrocosm

we learn that the universe is vaster than we thought, that

complex phenomena occur in what we thought a void, that

space and time once thought wholly separate are subtly

linked. In the microcosm with each more powerful ac

celerator we discover new subatomic particles and learn

of more complex relationships between them.

Even logic and mathematics have not escaped. In the

last century we learned that even one of the “self-evident

postulates of Euclid was open to question. Today we

accept both Euclidean and non-Euclidean geometries. In

our day, Ernest Nagel and James R. Newman tell us,1 a

1 4 The World of Mathematics, 1668 (1956)

— 34 —

1936 paper by Kurt Goedel came as an “astonishing and

melancholy revelation to mathematicians,” because it chal

lenged deeply rooted preconceptions concerning mathmati-

cal method.

If the “exact sciences” are thus inexact, what of the

criminal law? An ordered society needs the criminal law

for its protection; it needs incarceration for some; it does

not need to kill anyone for its own protection.

The death penalty is cruel and unusual punishment, be

cause the judicial procedures which would truly warrant

and justify such a penalty are beyond man. Such judicial

procedures are beyond man, because man is man, imperfect

in experience, imperfect in wisdom, imperfect in under

standing of his fellow man.

Joseph K, just before being put to death at the end of

Kafka’s novel, The Trial, declares

“Were there arguments in his favor that had been

overlooked? Of course, there must be. Logic is doubt

less unshakeable, but it cannot withstand a man who

wants to go on living. Where was the Judge whom

he had never seen? Where the High Court to which

he had never penetrated? He raised Ms hands and

spread out all his fingers.” (Knopf, 19591, p. 286).

We can tolerate an imperfect justice if we do not take life,

because of the need to protect society. But, we cannot

tolerate imperfect justice when we inflict an irreversible

penalty.

Moses, shortly before his death, in his final charge to

his people declared,

“Today I offer you the choice of life and good, or

death and evil. . . . I offer you the choice of life or

death, blessing or curse. Choose life. . . .” (Deut.

30:15-19)

We ask this Court, too, to choose life and good.

Respectfully submitted,

W il l a r d J. L a s s e r s

11 S. LaSalle Street

Chicago, Illinois 60603

and

E l m e r G e r t z

120 S. LaSalle Street

Chicago, Illinois 60603

Attorneys for Amici

August 26, 1971

— la —

APPENDIX

Policy Statements Opposing the Death Penalty

Adopted By Amici and Other Religious Organizations

NATIONAL COUNCIL OF THE CHURCHES OF

CHRIST IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

POLICY STATEMENT

ABOLITION OF THE DEATH PENALTY

Adopted by the General Board

September 13, 1968

In support of current movement to abolish the death

penalty, the National Council of Churches hereby de

clares its opposition to capital punishment. In so doing,

it finds itself in substantial agreement with a number of

member denominations which have already expressed op

position to the death penalty.

Reasons for taking this position include the following:

(1) The belief in the worth of human life and the dig

nity of human personality as gifts of God;

(2) A preference for rehabilitation rather than retribu

tion in the treatment of offenders;

(3) Reluctance to assume the responsibility of arbi

trarily terminating the life of a fellow-being solely be

cause there has been a transgression of law;

(4) Serious question that the death penalty serves as a

deterrent to crime, evidenced by the fact that the homi

cide rate has not increased disproportionally in those

states where capital punishment has been abolished;

(5) The conviction that institutionalized disregard for

the sanctity of human life contributes to the brutaliza

tion of society;

(6) The possibility of errors in judgment and the irre

versibility of the penalty which make impossible any

restitution to one who has been wrongfully executed;

— 2a

(7) Evidence that economically poor defendants, par

ticularly members of racial minorities, are more likely to

be executed than others because they cannot afford ex

haustive legal defenses;

(8) The belief that not only the severity of the penalty

but also its increasing infrequency and the ordinarily long

delay between sentence and execution subject the con

demned person to cruel, unnecessary and unusual punish

ment ;

(9) The belief that the protection of society is served

as well by measures of restraint and rehabilitation, and

that society may actually benefit from the contribution of

the rehabilitated offender;

(10) Our Christian commitment to seek the redemp

tion and reconciliation of the wrong-doer, which are frus

trated by his execution.