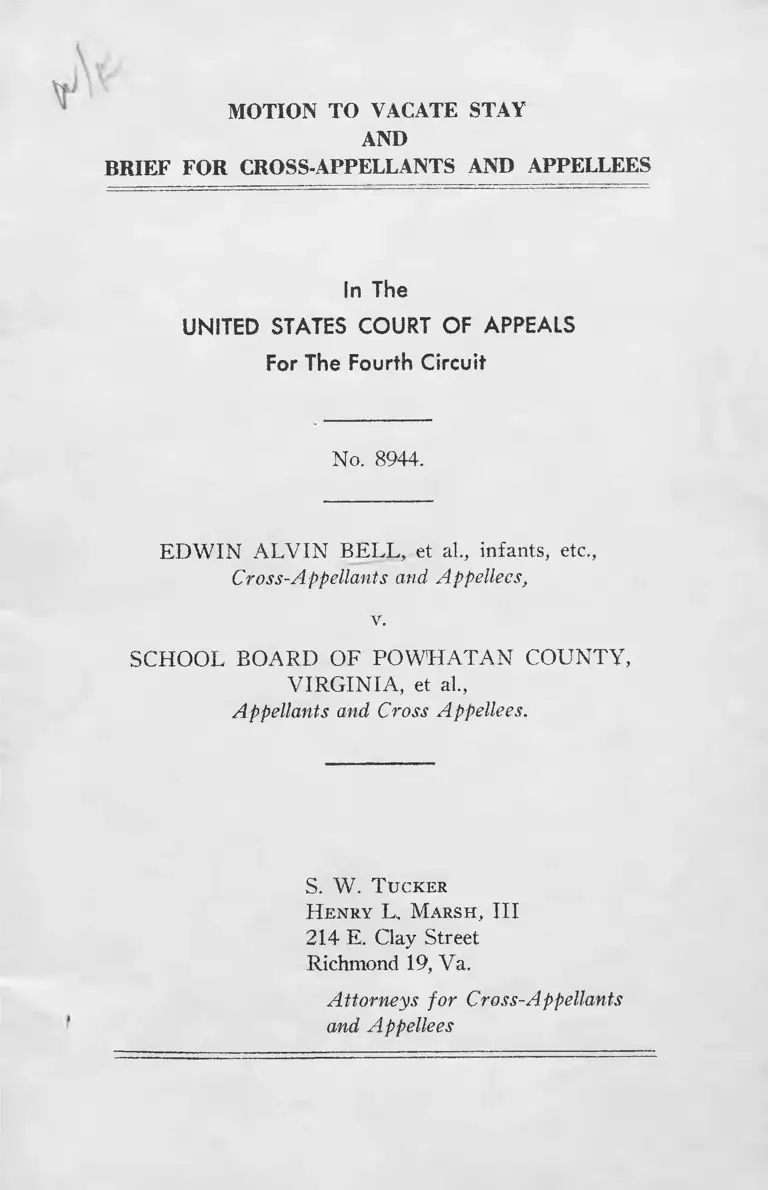

Bell v. School Board of Powhatan County, Virginia Motion to Vacate Stay and Brief for Cross-Appellants and Appellees

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1962

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Bell v. School Board of Powhatan County, Virginia Motion to Vacate Stay and Brief for Cross-Appellants and Appellees, 1962. d16d179d-c69a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/70e7336c-6c72-4e60-b7ac-f9e283daf078/bell-v-school-board-of-powhatan-county-virginia-motion-to-vacate-stay-and-brief-for-cross-appellants-and-appellees. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Copied!

MOTION TO VACATE STAY

AND

BRIEF FOR CROSS-APPELLANTS AND APPELLEES

In The

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

For The Fourth Circuit

No. 8944.

EDWIN ALVIN BELL, et al., infants, etc.,

Cross-Appellants and Appellees,

v.

SCHOOL BOARD OF POWHATAN COUNTY,

VIRGINIA, et al,

Appellants and Cross Appellees.

S. W. T ucker

H en ry L, M a rsh , III

214 E. Clay Street

Richmond 19, Va.

Attorneys for Cross-Appellants

and Appellees

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Motion to Vacate Stay ................ -............................... 1

Brief for Cross-Appellants and Appellees ................... 5

Statement of the Case.... ................................................ 5

Statement of Facts .................................................. 8

Questions Involved................................................... 13

Argument:

I. Failure To Grant The Racially Non-discrimina-

tory Assignments Sought By Plaintiffs Is Indefensible .. 14

II. The Local School Authorities Wilfully And De

liberately Interposed Administrative Obstacles With

The Obvious Purpose Of Thwarting School Desegrega

tion ............................................. 17

III. The Circumstances Of This Case Require

That Relief Be Granted All Of The Plaintiffs ........... 20

IV. The Circumstances Of This Case Fully Justify

An Award Of Counsel Fees ........................ ............... 21

Conclusion 22

TABLE OF CASES

Page

... 14Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U. S. 299

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1 ......................... ........ 14,

Green v. School Board of City of Roanoke, 304 F.2d

118 (4th Cir. 1962) .............................................. 14,

Jeffers v. Whitley, 309 F.2d 621 (4th Cir. 1962) ....14,

Local 149 International Union UAW, etc., v. American

Brake Shoe Company, 298 F.2d 212 (1962) ...........

Marsh v. The County School Board of Roanoke County,

305 I‘'.2d 94 (4th Cir. 1962) ............................ .

Rolax v. Atlantic Coast Line R. Co., 186 F.2d 473

(4th Cir. 1951) ............................. ........ ...................

School Board of City of Charlottesville v. Allen, 240

F.2d 59 (4th Cir. 1956) ....................... ....... ..........

Vaughan v. Atkinson, 369 U. S. 527 (1962) ...............

Wheeler v. Durham City Board of Education, 309 F.2d

630 (4th Cir. 1962) ................................. ............ 14,

17

21

16

21

16

21

14

22

16

In The

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

For The Fourth Circuit

No. 8944.

EDWIN ALVIN BELL, et al., infants, etc.,

Cross-Appellants and Appellees,

v.

SCHOOL BOARD OF POWHATAN COUNTY,

VIRGINIA, et al.,

Appellants and Cross Appellees.

MOTION TO VACATE STAY

Pauline Estelle Evans, Alcibia Olene Morris and Maria

Concetta Morris, infant plaintiffs, each by her parent and

next friend, move the United States Court of Appeals for

the Fourth Circuit to vacate an order of the United States

District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia (Rich

mond Division) entered on January 4, 1963, in the Civil

Action No. 3518 styled Edward Alvin Bell, et al, vs. The

County School Board of Powhatan County, Virginia, et al,

and, particularly so much of said order as stayed, pending

2

appeal, the effect of the hereinafter quoted injunctive pro

vision of an order of said district court entered in said

action on January 2, 1963, viz:

“2. The defendants, and each of them, their suc

cessors in office, agents, and employees be, and they

hereby are, enjoined and restrained from denying

Pauline Estella Evans, Alcibia Olene Morris and

Maria Concetta Morris admission to Powhatan Ele

mentary School. The injunction shall be effective im

mediately.”

The facts pertinent to this motion are:

1. The answer to the County School Board of Powhatan

County and J. S. Caldwell, Division Superintendent of

Schools of said county filed in said action on November

8, 1962, alleged that the said infant plaintiffs and their

respective parents failed to avail themselves of or . . . failed

to exhaust the administrative remedies available to them

under the statutes of Virginia relating to placement and

protests of pupils”.

2. In their Application for Declaratory Judgment filed

in the Circuit Court of the City of Richmond against the

Pupil Placement Board, copy of which they introduced as

■evidence in this action, the school board and division super

intendent have alleged as follows:

1. E. J. Oglesby, Edward T. Justice and Alfred L.

Wingo are the duly appointed residents of the State of

Virginia constituting the Pupil Placement Board (here

inafter called Placement Board), and as such and

3

pursuant to the provisions of Title 22, Section 232.1

of the Code of Virginia, as amended, have the power of

enrollment or placement of pupils in the public schools,

operated by the School Board in Powhatan County,

Virginia, the Board of Supervisors of said County

having adopted no ordinance and the School Board

having recommended the adoption of no ordinance-

pursuant to the provisions of Title 22, Section 232.30

of the Code of Virginia, as amended.

3. The Statute referred to in said pleadings provides in

part: “All power or placement of Pupils in and deter

mination of school attendance districts for the public

schools in Virginia is hereby vested in a Pupil Place

ment Board as hereinafter provided for. The local school

boards and division superintendents are hereby divested of

all authority now or at any future time to determine the

school to which any child shall be admitted.”

4. The Pupil Placement Board did not appeal from said

order of January 2, 1963, and the time within which it

might have appealed has expired.

5. By their said pleading and reliance upon the above

mentioned statute, the county school board and division

superintendent are estopped from asserting that they have

any power of enrollment or placement of any pupil in any

public school or any authority to determine the school to.

which any child shall be admitted.

6. Accordingly, the said county school board and division

superintendent are estopped from asserting that they are

4

prejudiced by the above quoted provision of the court’s

order,

WHEREFORE, these plaintiffs move that said stay be

vacated.

PAULINE ESTELLA EVANS, an

infant by William Douglas Evans

and Lucille Evans her parents and

next friends,

ALCIBIA OLENE MORRIS, an

infant, by Ivory Morris and Clara

Morris, her parents and next friends,

MARIA CONCETTA MORRIS, an

infant by James A. Morris and Alice

B. Morris, her parents and next

friends,

By S. W. T u ck er

Of Counsel

S. W. T u cker

H en r y L. M a rsh , III

214 East Clay Street

Richmond 19, Virginia

Counsel for Movants

In The

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

For The Fourth Circuit

No. 8944.

EDWIN ALVIN BELL, et al., infants, etc.,

Cross-Appellants and Appellees,

v.

SCHOOL BOARD OF POWHATAN COUNTY,

VIRGINIA, et al.,

Appellants and Cross Appellees.

BRIEF FOR CROSS-APPELLANTS AND APPELLEES

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

The complaint filed on August 17, 1962, charged that the

defendants County School Board of Powhatan County and

the Division Superintendent of Schools maintain and op

erate a racially segregated school system. It alleges that

applications were made to the defendants for the assign

ment of 39 of the 65 Negro infant plaintiffs to the ele

mentary school which white children attend1 and 23 of them

1 Through inadvertence the names of Jewnita P. Morris, Burnett

D. Morris and Earl Edward Morris were omitted from the list of

elementary school children named in paragraph 12 of the complaint.

6

to the high school which white children attend, and that no

action had been taken on these applications.

On September 17, 1962, the parties presented evidence in

support of and against the plaintiffs’ motion for an in

terlocutory injunction to enroll three Negro children in the

first grade at the (white) Powhatan School. On the same

day the school board and the superintendent of schools filed

a motion to dismiss and a motion to abstain and the Pupil

Placement Board filed a motion to abate.

At the October 19 hearing on these motions the Court

severed the claims of the three first grade children from

the claims of the other 62 infants. Upon request of counsel

for the Pupil Placement Board, the Court deferred acting

upon the claims of the three first grade children to afford

the Pupil Placement Board an opportunity to consider their

applications.

By its order of October 22, 1962, the Court granted the

motion of the school board to abstain and defer further

proceedings in the case as to the 62 infant plaintiffs on the

ground that a declaratory judgment suit was then pending

between the school board and the Pupil Placement Board,

"“for a reasonable time pending prompt determination of

the aforesaid suit in the Circuit Court of the City of

Richmond.”

On November 1, the plaintiffs moved the Court to alter or

amend its order of October 22, 1962. In a memorandum

filed with this motion, the plaintiffs asked the Court to

“proceed to hear the entire case and afford plaintiffs full

opportunity to prove (1) that the defendant school board

operates a bi-racial school system and (2) that the ad

ministrative remedy is wholly inadequate.”

/

At the trial on November 16, 1962, the plaintiffs offered

evidence from which the Court found (1) that the defend

ants operate a racially segregated school system, (2) that

the Pupil Placement Board denied the applications of the

three first grade plaintiffs because they had not been filed

prior to June 1, in conformity with the regulation of the

Pupil Placement Board set forth in Memo # 34, (3) that

if these applicants had been white children they would have

been temporarily admitted to Powhatan School (white)

pending formal placement in that school upon consideration

of their late application, (4) that application forms for the

use of students and their parents were not available to the

parents on May 29, 1962, and (S) that the school board

did not transmit the applications to the Pupil Placement

Board until after the [September 6, 1962] motion for

Temporary Restraining Order was made.

The Order of the District Court was entered on January

2, 1963. On January 29, 1963, the local school authorities

filed their notice of appeal, presumably from so much of

the Order of January 2, 1963, as (1) restrained them from

denying the three first grade plaintiffs admission to the

(white) Powhatan School and (2) restrained the further

use of racially discriminatory criteria in the assignment

of children to public schools in and after the fall of 1963.

On February 1, 1963, the plaintiffs filed their notice of

cross appeal challenging (1) the denial of plaintiffs’ motion

for the allowance of counsel fees and (2) the denial of

plaintiffs’ motion to reconsider the Order of October 22,

1962, by which the Court had abstained from further con

sideration of the claims of the remaining 62 infant

plaintiffs.

8

STATEMENT OF FACTS

In Powhatan County, there are but two schools.

Powhatan School is attended only by white children and

is staffed solely by white personnel. Pocahontas School

is attended only by Negro children and is staffed solely by

Negro personnel. Both schools have elementary and high

school departments. The schools are about three miles

apart. The attendance area for each of these schools em

braces the entire county. In the normal routine of school

assignment, white children are assigned to or placed in

Powhatan School without regard to where they live in

the county, and Negro students from throughout the county

are placed in Pocahontas School. Such assignment may be

tentatively made by the principals at any time and, when

so made, they are routinely confirmed by the Pupil Place

ment Board.

During the latter part of May 1962, the supervisor of

the elementary department of the Pocahontas School and a

number of the Negro teachers held a meeting because it was

feared that attempts of Negro parents to enroll their chil

dren in Powhatan School would be followed by a with

holding of appropriations for public schools. These teachers

drafted a warning to the colored parents urging them not

to seek school desegregation and caused mimeographed copies

thereof over the signature ‘James Arthur Willis, patron”

to be delivered by their students to the parents. (A. p. 42)

On May 29, the division superintendent suggested to a

citizen who was obviously interested in effecting school

desegregation that efforts toward that end would result in

school closing. [Nov. 16 Tr. p. 50.]

On May 21, 1962, applications on the official “Appli-

9

cation for Placement of Pupil” form for the transfer or

assignment of ten Negro children to Powhatan School were

left in the office of the division superintendent. (A. p. 27)

These ten infants, plaintiffs below and cross-appellants here,

are: Andrew Jonathan Brown, Herman Spencer Brown,

Jr., Josephine Juanita Hobson, Tracy Osborne Hobson,

Danny McAllister Johnson, Edna S. Morris, Irma M.

Morris, Lloyd A. Morris, Lloyd A. Taylor, Jr., and Willie

D. Taylor.

Within a few days thereafter several Negro parents

attempted to obtain official forms from the office of the

principal of the Pocahontas School. When the principal’s

supply was exhausted, some of the parents on at least two

occasions attempted to obtain forms from the office of the

division superintendent. (A. p. 67) As late as May 29,

the official forms were unavailable at either office. A regu

lation of the Pupil Placement Board required that “ap

plications for original placement in or transfer to a specified

school . . . be filed with the local division superintendents of

schools prior to June 1 immediately preceding the next

ensuing school session for which such placements or trans

fers are desired.” (A. p. 63, R. 59, 60)

On May 31, 1962, nineteen applications, on the official

forms, for transfer or assignment of Negro children to

Powhatan School were left in the office of the division

superintendent. (A. p. 28, R. 59, 60) The father of two of the

children withdrew the applications made on their behalf. The

remaining seventeen infants, plaintiffs below and (except

to the extent that Maria Concetta Morris is excluded),

cross-appellants here, are: Darrick H. Bell, Deborah R.

Bell, Jean W. Bell, Leon F. Bell, Marva Claudette Bell,

Nancy Diane Bell, Valarie A. Bell, Regenia Paulette

10

DePass, Dale Veronica Goodman, Burnette D. Morris,

Glenn L. Morris, Jerome L. Morris, Kenneth A. Morris,

Maria Concetta Morris, Maurice L. Morris, Rayfield O.

Morris, and Sandra R. Morris.

In addition, letter applications addressed to the local

school board and to the (state) Pupil Placement Board,

requesting transfer or assignment of eight Negro children

to Powhatan School, were delivered to the office of the

division superintendent and copies thereof were delivered

to the office of the Pupil Placement Board in Richmond,

both deliveries having been made on May 31. (A. pp. 28, 29)

These eight infants, plaintiffs below and cross-appellants

here, are: Edward Alvin Bell, Leah A. Bell, Gerald Brown,

Victor Brown, Earl Edward Morris, Jewnita P. Morris,

Michael E. Morris, and Victor H. Morris.

“On June 20, 1962, members of the School Board, Di

vision Superintendent, and their counsel met with the

Pupil Placement Board and their counsel and exhibited

these papers to the Placement Board and were naturally

informed that the papers were not complete but should be

executed by the principal or elementary supervisor of the

local school and on behalf of the local School Board. Sub

sequently the local School Board and the Division Super

intendent were advised by the Pupil Placement Board that

they should investigate to ascertain whether the applications

on the prescribed form were genuine and that the papers

should otherwise be completed and forwarded to the Pupil

Placement Board.”2 The earlier regulation promulgated by

2 Memorandum on behalf of County School Board of Powhatan

County and the Division Superintendent of Schools in support of

their motion that the court abstain. Filed October 22, 1962 (R. pp.

71-72).

11

the Pupil Placement Board in its March 12, 1962, Memo

#34, addressed to Local School Boards and Division

Superintendents of Schools, contained this language: “The

Pupil Placement Board will appreciate it if the Division

Superintendent will notify it immediately upon receipt of

any applications [for original placement in or transfer to a

particular specified school]”. (A. p. 63)

On August 3, 1963, letter applications addressed to the

local school board and to the Pupil Placement Board, re

questing transfer or assignment of twenty-nine Negro

children to Powhatan School, were received by the division

superintendent.3 (R. 61) These twenty-nine infants,

plaintiffs below and (except to the extent that Pauline

Estella Evans and Alcibia O. Morris are excluded) cross-

appellants here, are: Don Connell Batchelor, Roland Ed

ward Batchelor, Ryland L. Batchelor, William L. Batchelor,

Kilja Clementine Bell, Youlanda Cecila Bell, Carolyn

Celestine Bolling, Judy Grey Bolling, Alvin G. Brown,

Barbara Virginia Brown, Bernard E. Brown, Brenda L.

Brown, Earl O. Brown, Herbert Nathan Brown, Priscilla

Ann Brown, Randall William Brown, Jr., Charles William

Evans, Fannie Diane Evans, Pualine Estella Evans, De

Marco Antonello Harris, Charlene Juliette Ingram, Alcibia

O. Morris, Janice Laurette Payne, Shelia Ann Payne,

Deborah Christine Simms, Evelyn Virginia Simms, Marion

Joseph Simms, Marlene Jenette Simms, and Mary Frances

Simms.

Pauline Estella Evans, Alcibia Olene Morris, and Maria

3 Because of the limited aspect of the trial, the record does not

show delivery of copies to the Pupil Placement Board on August

6, 1962.

12

Concetta Morris were to enter school for the first time in

the fall of 1962. The parents of the first two signed official

“Application for Placement of Pupil” forms without

designation of any school and left them with the supervisor

at the Pocahontas School on June 8, 1962. On September

4 they were allowed by the supervisor to mark the forms

as being “under protest” and the mother of Maria Concetta

Morris executed an official application “under protest” and

left it with the supervisor at the Negro school. (These

forms were in addition to the applications mentioned

earlier.) An August 30 these three children had been taken

by their parents to the Powhatan School for enrollment

there and were referred to the superintendent who, in turn,

referred them to the supervisor at Pocahontas School.

(A, p. 35) The District Court’s order of January 2,

1963, directed the admission of these three children to the

Powhatan School.

It does not appear from the record that an application

on any form was made on behalf of the plaintiff and cross

appellant June C. Bell.

The local school authorities had not forwarded any of

the applications to the Pupil Placement Board on August

17, 1962, when this action was commenced. (A. p. 74)

The forms for the three beginners which had been left

with the supervisor and the forms from both schools which

did not challenge the racial pattern of school assignments

were all held by the local superintendent until the week pre

ceding the September 17, 1962 hearing on the plaintiffs’

motion for an interlocutory injunction. The applications

which expressly requested racially non-discriminatory as

signments—those made prior to June 1 and those made on

August 3 as well—were never forwarded by the local school

13

authorities to the Pupil Placement Board, but were made

the subject of litigation by the local school board against

the Pupil Placement Board in the Circuit Court of the City

of Richmond.

Powhatan County is near Prince Edward County where

the Board of Supervisors has caused public schools to re

main closed since June, 1959, rather than permit them to

be desegregated. The school officials of Powhatan County

are opposed to school desegregation. The record in this case

contains strong suggestions, introduced by the local school

authorities, that in the event of an order directing the

assignment of a Negro child to the white school, the Board

of Supervisors of Powhatan County would follow the lead

of Prince Edward County unless enjoined (as in this case

it was enjoined) from so doing.

THE QUESTIONS INVOLVED

I

Was the failure of the defendants to make racially non-

discriminatory school assignments so indefensible as to

require the court to grant relief to all of the infant plaintiffs

forthwith ?

II

Was the failure of the defendants to make racially non-

discriminatory school assignments so indefensible as to

justify an award of counsel fees to be taxed as a part of

the costs ?

14

ARGUMENT

I

Failure To Grant The Racially Non-discriminatory As

signments Sought By Plaintiffs Is Indefensible

There is no dispute as to the totally racially segregated

character of the two schools in Powhatan County. The

school board has no plan to bring about the desegregation

of the school system. (A. p. 64). The chairman of the Pupil

Placement Board, in response to inquiry whether his board

has any such plans, testified: “Certainly not.” (A. p. 56)

These facts alone would require an injunction against the

continued use of the factor of race as a basis for deter

mining the public school assignment of any child. Brown

v. Board of Education, 349 U.S. 294 (1955); Cooper v.

Aaron, 358 U.S. 1, (1958) ; School Board of City of Char

lottesville v. Allen, 240 F. 2d 59 (4th Cir. 1956) ; Green v.

School Board of City of Roanoke, 304 F. 2d 118 (4th Cir.

1962); Jeffers v. Whitley, 309 F. 2d 621 (4th Cir. 1962) ;

and Wheeler v. Durham City Board of Education, 309 F. 2d

630 ( 4th Cir. 1962).

As best we can understand the position of the county

school board and division superintendent, it is that none of

the plaintiffs made application for admission to the white

school in accordance with the state’s pupil placement pro

cedure and, hence, none of them had standing to bring this

action.

One answer to the contention of the school authori

ties is that, on May 21, 1962, the parents of ten of the

infant plaintiffs and, on May 31,1962, the parents of twenty-

five of the infant plaintiffs made and filed applications in

15

strict compliance with the statute and with every require

ment of the Pupil Placement Board. The argument of the

local school authorities (that the applications must be

filed with the local school and, “to insure genuineness”, must

be signed by the principal or head teacher of the local

school) is entirely specious. It seeks justification in a

distorted analysis of the official application form itself and

certain instructions printed on a detachable slip at the head

thereof, viz:

“TO THE PARENT OR GUARDIAN: Please com

plete the application below, sign and return to your

local school. Be sure not to write on lower portion

reserved for use of Boards only,”

The lower portion (reserved for use of local boards only)

requires the principal or head teacher to enter over his

signature his “Comments concerning pupil” and his “Rec-

commendation as to the school to which pupil should be

assigned”.

This printed application form has no provision for the

parents’ indication of the school they want the child to at

tend. It merely requests the Board to place the chlid where

the Board thinks the child should be. The Pupil Place

ment Board has not prepared a form to be used as an ap

plication for original placement in or transfer to a par

ticular specified school. From all that appears, the Pupil

Placement Board does not contemplate the use of its form

by a parent who wishes to designate the school the child is

to attend. For the governance of such cases (as distin

guished from the routine cases in which the parent will

trust the board’s judgment) the Pupil Placement Board,

16

on March 12, 1962, issued its Memo #34 to the local

school boards and division superintendents stating:

“The Pupil Placement Board will not consider ap

plications for original placement in or transfer to a

particular specified school unless such applications

are filed in writing stating reasons for the preferences.

These applications must be filed W ITH THE LOCAL

DIVISION SUPERINTENDENTS OF SCHOOLS

prior to June 1 immediately preceding the next ensuing

school session for which such placements or transfers

are desired.” [Emphasis supplied.]

Furthermore, the parents were never informed that the

applications should not be filed with the superintendent as

the above quoted regulation requires.

A further answer of the twenty-nine infants on whose

behalf letter applications were made on August 3, 1962,

and the further answer of June C. Bell on whose behalf

no application appears to have been made prior to the

institution of this action is that, the timely applications of

others similarly situated having proved futile, they are not

bound to have pursued an administrative procedure demon

strably inadequate to free them from initial school as

signment based entirely on race. Marsh v. The County

School Board of Roanoke County, 305 F. 2d 94 (4th Cir.

1962) ; Jeffers v. Whitley, supra; Wheeler v. Durham City

Board of Education, supra.

A final answer to- such contention is that we are deal

ing with rights of infants “not to be segregated on racial

grounds in [public] school”—rights which are “indeed

so fundamental and pervasive [as to be]embraced in the

17

concept of due process of law.” By the same token, we are

dealing with the duty of state authorities to effectuate these

rights by devoting “every effort toward initiating de

segregation and bringing about the elimination of racial

discrimination in the public school system.” Cf. Cooper v.

Aaron, supra. Infants are not presumed to know their

rights and they are considered powerless to make demand

upon public officials or to coerce their parents or guardians

into doing so; but they are special wards of chancery. So,

even in the absence of any demand by the infant or by the

person to whom the law entrusts his custody, the District

Courts, in the exercise of their equity jurisdiction may, at

the suit of an aggrieved infant by his next friend, “take

action as [is] necessary to bring about the end of racial

segregation in the public schools with all deliberate

speed.” [Id.]

II

The Local School Authorities Wilfully And Deliberately

Interposed Administrative Obstacles With The Obvious

Purpose Of Thwarting School Desegregation.

If the state’s Pupil Placement Act has any legitimate

purpose or constitutional validity, it stems from the state

board’s availability to execute the constitutional mandate

to desegregate public schools notwithstanding the local

community opposition and pressures from which the state

board would be better insulated than would the local board.

The testimony of the chairman of the Pupil Placement

Board that his board “certainly” did not have plans to

desegregate the public schools of Powhatan County ad

equately pierces the veil of presumption of constitutionality

which otherwise might surround the statutory requirement

18

that “each school child . . . shall attend the same school

which he last attended until graduation therefrom unless

enrolled, for good cause shown, in a different school by

the Pupil Placement Board.” (Code of Virginia, 1950,

§ 22-232.6.) Furthermore, since the only application for

enrollment in a particular specified school in Powhatan

County would be an application for a child’s attendance at

the school maintained for persons not of his race, enforce

ment of the Pupil Placement Board’s Memo #34, which

prescribes special requirements and special procedures in

such cases, necessarily discriminates against those who

seek racially non-discriminatory school assignment. Inas

much as the Pupil Placement Board did not appeal from

the District Court’s reversal of the board’s disposition of

the applications of the three beginners and inasmuch as the

local authorities prevented that board’s action on any other

applications, further attack upon the procedures of the

Pupil Placement Board and the statute under which it acts

would be inappropriate. We proceed to the local school au

thorities and their employees and their deliberate subver

sion of the state board’s procedure into an unnegotiable

obstacle course frustrating the efforts of the adult plain

tiffs to obtain for their children rights secured by the Four

teenth Amendment.

The fear of the elementary supervisor and teachers at

the Negro school that efforts to enroll Negro children in

the white school might result in closed public schools is

understandable. Their letter to the parents over the

signature of a patron reflects little credit upon their literary

standards and less upon their appreciation of the responsi

bilities of American citizenship. The school board put it

self in no better light when it relied upon, rather than

repudiated, this attitude and action of its employees as

19

justification for its refusal to obey the Constitution’s

mandate to eliminate racial discrimination in the public

school system.

Flagrant disregard for this Constitutional requirement

is reflected in every action of any public school official or

employee which is related in the record in this case. In

the face of a May 31 “deadline” for applications for racially

non-discriminatory school assignments, the forms which

the local school authorities contend to be essential were

unavailable. Attempts of citizens to obtain forms from

the superintendent were met with threats that schools would

be closed if desegregation were required. Negro parents

of children entering school for the first time were “re

ferred” by the principal of the white school to the division

superintendent who, in turn, directed them to the supervisor

at the colored school.

The superintendent deliberately failed to forward to

the Pupil Placement Board the thirty-seven applications

for assignment to a particular specified school which were

in his hands on May 31, notwithstanding the plain directive

that the board be notified immediately upon receipt of such

applications. The June 20 conference of school board mem

bers, the superintendent, their attorney, the Pupil Place

ment Board members and its attorney v/as not held with a

view of facilitating favorable action on the subject applica

tions ! It resulted in a decision of the school board to com

mence frivolous litigation in the state court with the hope

of forestalling or delaying action by the applicants in the

United States District Court.

And even when the District Court limited its require-

20

ment of immediate compliance, to the admission of three

Negro children to the first grade at the white school, the

local school authorities elected to continue their resistance

not only against that part of the order but also against so

much of the order as was designed to insure the continued

operation of public schools. [A. pp. 80, 81]

Plainly, here, the school board makes war on the Con

stitution. Cf. Cooper v. Aaron, supra.

Ill

The Circumstances Of This Case Require That Relief

Be Granted All Of The Plaintiffs

From what has been said, it seems to be clear that thirty-

five of the infant plaintiffs and their parents satisfied

everything required of them before the June 1 deadline

date. The evidence does not show how many of the twenty-

nine applications of August 3 would have been made prior

to June 1 if the official forms had been available or if the

applicants had been advised that the official forms were not

necessary. However, it is clear that even had the applica

tions been made earlier they would not have been favorably

considered although applications made later would have

been favorably considered if they did not request racially

non-discriminatory assignments. Denial of relief to any

plaintiff would be endorsement of the dilatory tactics em

ployed by the school board. War on the Constitution cannot

be thus condoned. Each infant plaintiff is entitled to in

dividual relief in addition to the injunction affording class

relief. Wheeler v. Durham City Board of Education, supra.

21

IV

The Circumstances Of This Case Fully Justify An

Award Of Counsel Fees

The School Desegregation Cases were decided by the

Supreme Court on May 17, 1954. Since that time the school

board has knowingly denied Negro children the protection

and liberty which is rightfully theirs. The May 22, 1962,

decision of this Court in Green v. School Board of the City

of Roanoke, supra, and the decisions therein cited had

foreclosed every defense the defendants might have con

ceived.

The plaintiffs’ claim to an award of counsel fees is ad

equately supported in this Court’s opinion in Local 149 In

ternational Union UAW, etc v. American Brake Shoe

Company, 298 F. 2d 212 (1962), viz:

“The power of a court of equity to allow the taxation

of attorneys’ fees as costs has been before this Court.

In Rolax v. Atlantic Coast Line R. Co., 186 F.2d 473

(4 Cir. 1951), this Court dealt with such a situa

tion. There Chief Judge Parker held that, under the

Railway Labor Act, Negro fireman were entitled to

relief against the railroad and the Brotherhood of

Locomotive Firemen and Enginemen from a dis

criminatory contract entered into between the union

and the railroad.

“In sanctioning the award of attorneys’ fees to the

Negro firemen the Court said at page 481:

“ . . under the circumstances here we think that

the allowance of attorneys’ fees as a part of the

costs is a matter resting in the sound discretion of

22

the trial judge. Ordinarily, of course, attorneys’

fees, except as fixed by statute, should not be taxed

as a part of the costs recovered by the prevailing

party, but in a suit in equity where the taxation of

such costs is essential to the doing of justice, they

may be allowed in exceptional cases. The justifica

tion here is that plaintiffs of small means have been

subjected to discriminatory and oppressive conduct

by a powerful labor organization which was re

quired, as bargaining agent, to protect their in

terest. The vindication of their rights necessarily

involves greater expense in the employment of coun

sel to. institute and carry on extended and important

litigation than the amount involved to the individual

plaintiffs would justify their paying. * * *’ ”

See, also, Vaughan v. Atkinson, 369 U. S. 527 (1962).

CONCLUSION

WHEREFORE it is respectfully submitted that the

judgment of the District Court should be affirmed and the

suspension thereof should be vacated except insofar as said

judgment overrules the plaintiffs’ motion to amend the order

of October 22, 1962, and overrules the plaintiffs’ motion

for the allowance of counsel fees. With respect to said mo

tions and the ruling of the District Court thereon, it is

respectfully submitted that the defendants should be en

joined forthwith from denying any of the infant plaintiffs

admission to Powhatan School and that a fee for plaintiffs’

23

counsel in such amount as to the Court may seem just

should be awarded and taxed as costs.

Respectfully submitted,

S. W. T u ck er

H enry L. M a rsh , III

Attorneys for Cross-Appellants

and Appellees

214 E. Clay Street

Richmond 19, Va.