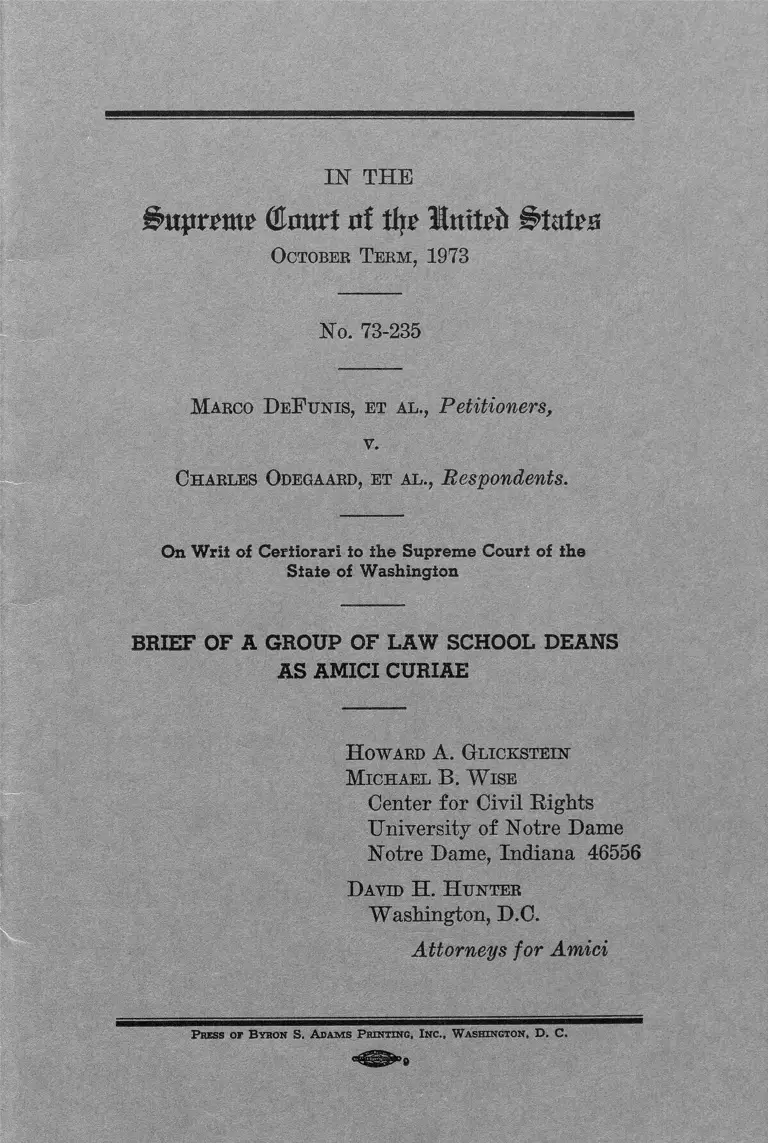

DeFunis v. Odegaard Brief of a Group of Law School Deans as Amici Curiae

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1973

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. DeFunis v. Odegaard Brief of a Group of Law School Deans as Amici Curiae, 1973. a44a6683-af9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/70eab15a-d9d9-4e71-a6a6-9b8d702c985f/defunis-v-odegaard-brief-of-a-group-of-law-school-deans-as-amici-curiae. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

IN' THE

§>upxm? QJmtrt rtf i\\t Inttrft

October Term, 1973

No. 73-235

M arco D eF unis, et al., Petitioners,

V.

Charles Odegaard, et al., Respondents.

On Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of the

State of Washington

BRIEF OF A GROUP OF LAW SCHOOL DEANS

AS AMICI CURIAE

H oward A. Glickstein

M ichael B. W ise

Center for Civil Rights

University of Notre Dame

Notre Dame, Indiana 46556

D avid H . H unter

Washington, D.C.

Attorneys for Amici

Press or B yron S. Adams P hinung, Inc., W ashington. D. C.

GROUP OF LAW SCHOOL DEANS AS AMICUS CURIAE

T hom as W eldon C h b isto ph er , Dean, University of Ala

bama School of Law

G ordon A. C h risten so n , Dean, American University Law

School

E dgar S. Cailn , Co-Dean, Antioch School of Law

J ean C am per C a h n , Co-Dean, Antioch School of Law

W illard H . P edrick , Dean, Arizona State University

College of Law

R ichard G. H uber , Dean, Boston College of Law

P au l M. S isk in d , Dean, Boston University School o f Law

E dward C. H albac ii, Jr., Dean, University of California

School of Law, Berkeley

D an ie l J. D y k stra , Dean, University of California School

of Law, Davis

M arvin J. A nderson , Dean, University of California,

Hastings College of Law, San Francisco

M urray L. S ch w a r tz , Dean, University of California, Los

Angeles, School of Law

L indsey C o w en , Dean, Case Western Reserve University,

Franklin T. Bacus Law School

E . Clin to n B amberger, J r ., Dean, Catholic University of

America School of Law

A r t h u r H. T ravers, Jr., Acting Dean, University of Colo

rado School of Law

F rancis C. C ady, Acting Dean, University of Connecticut

School of Law

R oger C. Cram ton , Dean, Cornell Law School

R obert B. Y egge, Dean, University of Denver College of

Law

L y m a n R ay P atterson , Dean, Emory University School of

Law

J oshua M. M orse, III, Dean, Florida State University Col

lege of Law

A drian S anford F ish e r , Dean, Georgetown University Law

Center

R obert K ram er , Dean, George Washington University

National Law Center

J. L a n i B ader, Dean, Golden Gate College School of Law

T h e R everend F rancis J. C o n k l in , S.J., Dean, Gonzaga

University School of Law

M onroe H. F reedm an , Dean, Hofstra University School

of Law

A lbert R. M enard , J r ., Dean, University of Idaho College

of Law

W ayne R. L aF ave, Acting Dean, University of Illinois Col

lege of Law

D ouglass G. B osh kofe , Dean, Indiana University School

of Law

J am es R . M erritt , Dean, University of Louisville School

of Law

F rederick J. L ow er, Jr., Dean, Loyola University School

of Law, Los Angeles

M arcel Garsaud, J r ., Dean, Loyola University School of

Law, New Orleans

G ordon D. S chaber , Dean, McGeorge School of Law, Uni

versity of the Pacific

T heodore J. St. A n to in e , Dean, University of Michigan

Law School

Carl A. A uerbach , Dean, University of Minnesota Law

School

F rederick M. H art , Dean, University of New Mexico

School of Law

R ichard D. S ch w artz , Dean, State University of New York

at Buffalo School of Law

L eM arquis D eJ arm o n , Dean, North Carolina Central Uni

versity School of Law

D ickson P h il l ip s , Dean, University of North Carolina

School of Law

J am es A . R a h l , Dean, Northwestern University School of

Law

T hom as L. S h affer , Dean, University of Notre Dame Law

School

J am es C. K irby , J r ., Dean, Ohio State University College

of Law

E ugene F. S coles, Dean, University of Oregon School of

Law

B ernard W o lfm an , Dean, University of Pennsylvania Law

School

W illard H eckel , Acting Dean, Rutgers, The State Uni

versity of New Jersey School of Law, Newark

R ichard J efferson C hildress, Dean, St. Louis University

School of Law

D onald T. W eck stein , Dean, University of San Diego

School of Law

C. D elos P u t z , J r ., Dean, University o f San Francisco

School of Law

George J. A lexander , Dean, University of Santa Clara

School of Law

R obert W. F oster, Dean, University of South Carolina

School of Law

D orothy W. N elson , Dean, University of Southern Cali

fornia Law Center

P eter J ames L iacouras, Dean, Temple University School

of Law

O tis H. K in g , Dean, Texas Southern University School of

Law

R obert B. McK ay, Dean, New York University School of

Law

S am u el D. T h u r m a n , Dean, University of Utah College of

Law

A lfred W. M eter , Dean, Valparaiso University School of

Law

R obert L. K nauss , Dean, Vanderbilt University School of

Law

W illard D. L orensen , Dean, West Virginia University

College of Law

L arry K. H arvey, Dean, Willamette University College of

Law

George B u n n , Dean, University of Wisconsin Law School

E. George R u d olph , Dean, University of Wyoming College

of Law

(The institutional association of the signers of this brief

is provided for identification purposes. The signers do not

necessarily represent the view of their institutions.)

R ichard B. A mandes, Dean, Texas Tech University School

of Law

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

. 1Interest of the Amici . ,

Consent of the Parties

Question Presented . .

Summary of Argument

Argument ............. .

The admissions policy of the University of Washington

School of Law represented the exercise of sound

administrative judgment..................................... .

I. Determining whom to admit to a law school class

involves weighing a myriad of factors, both sub

jective and objective ..........................................

II. The racial and ethnic background of applicants

is an appropriate factor to consider in determin

ing admissions to law school . ............................

A. Purely mechanical criteria are an inadequate

basis for determining the composition of a

law school class ...............................................

B. The desirability of a heterogeneous student

body is an appropriate element of a law

school’s admission policy ..............................

C. The nature of legal services required by the

public is an appropriate consideration for a

law school in constituting its student body . .

D. It is appropriate for a law school’s admis

sions policy to be sensitive to the pivotal role

played by the legal profession in our national

life ..................................................................

2

2

2

3

3

3

8

10

11

13

15

11 Table of Contents Continued

Page

E. It is appropriate for the admissions policy of

a public law school to be sensitive to the need

to overcome the effects of past and present

illegal discrimination suffered by minority

group members ..................................... 16

1. The paucity of minority lawyers is the re

sult of discrimination................................ 16

2. Voluntary remedial action is not depend

ent upon a finding of discrimination......... 19

3. Remedial action may impinge on the ex

pectations of others.................................... 21

Conclusion ............................. 24

INDEX OF CITATIONS

Ca se s :

Addabbo v. Donovan, 16 N.Y.2d 619, 209 N.E.2d 112,

261 N.Y.S.2d 68 (1965), cert, denied, 382 U.S. 905

(1965) ....................................................................... 19

Associated General Contractors of Massachusetts, Inc.

v. Altshuler, 6 EPD U 8993 (C.A. 1, 1973) ........... 9, 22

Balaban v. Rubin, 14 N.Y.2d 193, 199 N.E.2d 375, 250

N.Y.S.2d 281, cert, denied, 379 U.S. 881 (1964) .. 19

Balsbaugh v. Rowland, 447 Pa. 423, 290 A.2d 85 (1972) 19

Booker v. Board of Education, 45 N.J. 161, 212 A.2d 1

(1965) ....................................................................... 19

Brooks v. Beto, 366 F.2d 1 (C.A. 5, 1966) ................... 10

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954) . . 17

Carter v. Gallagher, 452 F.2d 315, modified en banc,

452 F.2d 327 (C.A. 8, 1972), cert, denied, 406 U.S.

950 (1972) ................................. 22

Chance v. Board of Examiners, 458 F.2d 1167 (C.A. 2,

1972) ............. 20

Contractors Association of Eastern Pennsylvania v.

Secretary of Labor, 442 F.2cl 159 (C.A. 3, 1971),

cert, denied, 404 U.S. 854 (1971) ......................... 20,22

Deal v. Cincinnati Board of Education, 369 F.2d 55

(C.A. 6, 1966), cert, denied, 389 U.S. 847 (1967). .7,19

Index of Citations Continued m

Page

DeFunis v. Odegaard, 82 Wn.2d 11, 507 P.2d 1169

(1973) ..................................... 4,13

Fuller v. Volk, 230 F. Supp. 25 (D.N.J. 1964), vacated

on other grounds, 351 F.2d 323 (C.A. 3, 1965),

adhered to on the merits, 250 F. Supp. 81 (D.N.J.

1966) ............................ .'......................................... 19

Gaston County v. United States, 395 U.S. 285 (1969). . 21

Guida v. Board of Education, 26 Conn. Supp. 121, 213

A.2d 843 (Super. Ct. 1965) ............................ . 19

Guinn v. United States, 238 U.S. 347 (1915) ............... 6

Johnson v. Pike Corporation of America, 332 F. Supp.

490 (C.D. Cal. 1971) .................................... 21

Keyes v. School District No. 1, Denver, Colorado, 413

' U.S. 189 (1973) ....... ............................................... 17

Local 189, United Papermakers and Paperworkers,

AFL-CIO v. United States, 416 F.2d 980 (C.A. 5,

1969), cert, denied, 397 U.S. 919 (1970) ............... 20

McDaniel v. Barresi, 402 U.S. 39 (1971) ................... 18

Meredith v. Fair, 298 F.2d 696 (C.A. 5, 1962) ........... 6

Morean v. Board of Education, 42 N.J. 237, 200 A.2d 97

(1964) ....................................................................... 19

North Carolina State Board of Education v. Swann,

402 U.S. 43 (1971) .................................................. 19

Norwalk CORE v. Norwalk Redevelopment Agency,

395 F.2d 920 (C.A. 2, 1968) ........................ . .18, 20, 21

(Merman v. Nitowski, 378 F.2d 22 (C.A. 2, 1967) . . . . 19

Oregon v. Mitchell, 400 U.S. 112 (1970) ..................... 21

Porcelli v. Titus, 431 F.2d 1254 (C.A. 3, 1970), cert.

denied, 402 U.S. 944 (1971) ............................. ..20,22

School Committee of Boston v. Board of Education,

352 Mass. 693, 227 N.E.2d 729 (1967), appeal dis

missed, 389 U.S. 572 (1968) .................................. 19

Sobol v. Perez, 289 F.Supp. 392 (E.D. La. 1968)......... 14

Springfield School Committee v. Barksdale, 348 F.2d

261 (C.A. 1, 1965) .............................................. . . 8 , 2 0

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education,

402 U.S. 1 (1971) ..........................................8,12,19, 23

Sweat! v. Painter, 339 U.S. 629 (1950) . . . ._............. 12,17

Tometz v. Board of Education, Waukegan City, 39 111.

2d 593, 237 N.E.2d 498 (1968) .............................. 19

United States v. Bethlehem Steel Corporation, 446 F.2d

652 (C.A. 2, 1971) .................. ............................... 22

IV Index of Citations Continued

Page

United States v. Jefferson County Board of Education,

372 F.2d 836 (C.A. 5, 1966), cert, denied sub nom.

Board of Education of Bessemer v. United States,

389 U.S. 840 (1967) ............................................... 9

United States v. Louisiana, 252 F.Supp. 353 (E.D. La.

1963), aff’d, 380 U.S. 145 (1965) ............................ 9

United States v. Wood, Wire and Metal Lathers In

ternational Union, Local Union 46, 341 F.Supp,

694, (S.D.N.Y. 1972), aff’d, 471 F.2d. 408 (C.A. 2,

1973), cert, denied, 412 U.S. 939 (1973) ............... 22

Wanner v. County School Board of Arlington County,

Virginia, 357 F.2d 452 (C.A. 4, 1966) ................. 8,19

S t a t u t e s :

5 U.S.C. §§ 3309, 3312 ................................................... 5

38 U.S.C. §§ 1681, 1801-27 ......................................... . 5

42 U.S.C. § 1477 .............................................................. 5

42 U.S.C. §§ 2000e et seq.................................................. 22

43 U.S.C. § 186 ................................................................ 5

50 U.S.C. App. §§ 459, 1884 ........................................... 5

C o n stitu tion al P kovision :

Fourteenth Amendment ......................................... 2

M iscellaneous :

Bell, Black Students in White Schools: The Ordeal

and the Opportunity, 1970 Toledo L. Rev. 539. . . . 15

Consalus, The Law School Admission Test and the

Minority Student, 1970 Toledo L. Rev. 5 0 1 ......... 6, 7

Gellhorn, The Law School and the Negro, 1968 Duke

L.J. 1068............... ...13,17

Graglia, Special Admission of the ‘ ‘ Culturally De

prived” to Law School, 119 U. Pa. L. Rev. 354

(1970)........................................................................... 14

Lasswell & McDougal, Legal Education and Public

Policy: Professional Training in the Public In

terest, 52 Yale L.J. 203 (1943)...................... 15

Index of Citations Continued y

Page

Morris, Equal Protection, Affirmative Action and

Racial Preferences in Law School Admissions, 49

Wash. L. Rev. 1 (1973)........................................... 14

O’Neil, Preferential Admissions: Equalizing the Ac

cess of Minority Groups to Higher Education, 80

Yale L.J. 699 (1971)...................... ; ......................6, 3.4

O’Neil, Preferential Admissions: Equalizing Access to

Legal Education, 1970 Toledo L. Rev. 281............ 12

Oppenheim, The Abdication of the Southern Bar in L.

Friedman, ed., Southern Justice 127 (1965). . . . . . 14

Pinderhughes, Increasing Minority Group Students in

Law Schools: The Rationale and the Critical Is

sues, 20 Buf. L. Rev. 447 (1971)........................... 10,16

Reynoso et al., La Raza, the Law, and the Law

Schools, 1970 Toledo L. Rev 809..........................14,17

Strickland, Redeeming Centuries of Dishonor: Legal

Education and the American Indian, 1970 Toledo

L. Rev. 847....................................... ................... .14,17

Twentieth Century Fund, Administration of Justice

in the South 3 (1967) ......................................... .. 14

TT.S. Bureau of the Census BLS Report No. 394, Series

P-23, No. 38, Table 67 . . . . . . . ........................ 17

IT.S. Bureau of the Census, Current Population Re

ports, Series P-23, No. 46, Table 7 (1972) ........... 18

U.S. Bureau of the Census, 1970 Census of Popula

tion, PC(2)lc, PC (2)lf, PC (2)lg ......... ............ . 17

1972 Proceedings of the Association of American Law

Schools ............. ........................................ .............. 12

IN' THE

Aupran? (tort ni tl?r lnttr&

October Term, 1973

No. 73-235

Marco DeE itnis, et al., Petitioners,

v.

Charles Odegaard, et al., Respondents.

On Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of the

State of Washington.

BRIEF OF A GROUP OF LAW SCHOOL DEANS

AS AMICI CURIAE

INTEREST OF THE AMICI

The amici are deans of law schools located through

out the United States who are concerned with the effect

a decision reversing the Supreme Court of Washington

would have on the admission policies and student com

position of law schools throughout the nation. The

deans believe that law schools must retain the adminis

trative flexibility and discretion to employ a wide

range of criteria, both subjective and objective, in

selecting those students who can best contribute to their

law school and to the legal profession. The deans

believe that it is equally imperative that law schools

continue to be permitted to consider the minority status

of an applicant as one criterion in the admissions

process so that they can effectively fulfill their obli

gation to take affirmative steps to overcome the con

tinuing effects of past discrimination in law schools

and in the legal profession.

2

CONSENT OF THE PARTIES

Marco DeFunis, et al., and Charles Odegaard, el al.,

by their attorneys, have consented to the filing of this

brief. Their letters of consent are on file with the

Clerk of this Court.

QUESTION PRESENTED

Does a state supported school of law violate the

Equal Protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment

when, in endeavoring to overcome the effects of past

discrimination, it considers an applicant’s racial or

ethnic background among the many factors it weighs

in determining whom to admit?

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

The University of Washington Law School, like

most law schools, employs a wide range of criteria in

selecting students for admission who can best con

tribute to the law school and to the legal profession.

These law schools have found that many of the goals

they hope to accomplish through their admission poli

cies would go unrealized were they mechanically and

uncritically to accept candidates solely on the basis

of college grade averages and LSAT scores. Several

of the most important of these admission policies re

quire the law schools to consider the race and ethnic

background of the applicant as one of the many factors

that are examined in reaching a decision. These poli

cies include the desire to insure a representative

student body, the desire to help overcome the critical

shortage of minority group lawyers so that all groups

are represented in the profession so influential in both

public and private policy decisions in the United States,

and, most important of all, the desire to remedy the

continuing effects of racial and ethnic discrimination

3

which has for so long denied minority groups their

rightful place of equality in American society. Such

voluntary efforts to overcome our nation’s legacy of

slavery and discrimination are constitutionally permis

sible and should be encouraged.

ARGUMENT

The Admissions Policy of the University of Washington

School of Law Represented the Exercise of Sound

Administrative Judgment.

I. DETERMINING WHOM TO ADMIT TO A LAW SCHOOL

CLASS INVOLVES WEIGHING A MYRIAD OF FAC

TORS, BOTH SUBJECTIVE AND OBJECTIVE.

Choices among different people are generally dif

ficult. Choosing among applicants for a law school

class is no exception. Indeed, in the case of the Uni

versity of Washington Law School in its selection of

the class entering in the fall of 1971 the difficulties

were staggering. There were 1601 applications for

no more than 150 positions in the class. (Finding X ,

A. 48) 1 Since most of the applicants were considered

capable of doing the work which is required in law

school, the school faced two difficult questions: What

criteria were to be used to choose among capable ap

plicants? How can those criteria be applied within

the limits of the manpower available to review the

applications and the time available for this process?

The school found appropriate and workable answers

to both questions. In selecting applicants for ad

mission the admissions committee followed this

standard:

“ In assessing applications, we began by trying to

identify applicants who had the potential for out

1 References to material in the Single Appendix are denoted

herein as “ A .”

4

standing performance in law school. We at

tempted to select applicants for admission from

that group on the basis of their ability to make

significant contributions to law school classes and

to the community at large.” (A. 34-5)

The committee’s interpretation of this standard was

guided in part by the University policy to eliminate

“ the continued effects of past segregation and dis

crimination” against minority group members.

DeFunis v. Odegaard, 82 Wn. 2d 11,19, 507 P. 2d 1169,

1175 (1973).

Members of the admissions committee spent about

1300 hours in the process of deciding whom to admit.

Much more time would have been necessary if certain

steps had not been taken to facilitate the decision

making process. For each applicant a predicted

first year average (P F Y A ) was calculated based on

college grades, the LSAT aptitude score, and the

LSAT writing score, and this figure was used to

separate the applications into three groups, which re

ceived different levels of attention. Secondly, appli

cations from minority group members wTere considered

separately. These steps were taken in order to es

tablish general criteria applicable to all candidates

and to insure that special factors relevant to minority

candidates were taken into consideration. No appli

cant was either accepted or rejected solely on the basis

of his or her PFYA. No applicant was either ac

cepted or rejected solely on the basis of his or her race

or ethnic background. DeFunis v. Odegaard, 82

Wn. 2d at 17, 19, 20, 39-40, 507 P. 2d at 1173, 1174,

1175, 1185-86.

The PFYA , based upon the LSAT score and college

grades, was only one part of the decision-making

process. It stands out because it is the only factor

which is quantifiable, but this should not lead to an

overrated estimate of its importance. Its weight

might vary from applicant to applicant. For ex

ample, experience with particular colleges might in

dicate that their grades predicted very well the law

school grades of students coming from it. Such

grades would be relied on more than grades from, a

school which had sent few students to the law school

before or from a school whose grades did not predict

law school performance. Two students were admitted,

moreover, who had no grades at all from the last two

years of college. (A. 40-41)

Grades and test scores are not all that schools con

sider in determining whom to admit. Law schools

(and other institutions of higher education) use a

variety of criteria in reviewing applications. For ex

ample, the University of Washington Law School gave

preference to a certain class of veterans, men who had

been admitted in the past but had been unable to at

tend the law school because of the draft. These ap

plicants were admitted automatically. (A. 31) In

some cases these veterans could not meet current

standards. Though one could argue that admitting

such a veteran deprives a better qualified applicant of

a place in the lawT school, considerations of fairness

and of national policy make this preference unobjec

tionable. 2

Some state universities and law schools give pref

erence to residents of the state, though no claim is

made that residents of the particular state are better

students. In fact, petitioner argued unsuccessfully

below that the University of Washington was required

S3

2 Preference for veterans is a common feature of many of our

laws. See, e.g., 5 TJ.S.C. §§ 3309, 3312; 38 U.S.C. §§ 1681, 1801-27;

42 U.S.C. § 1477; 43 U.S.C. § 186; 50 U.S.C. App. §§459, 1884.

6

to give such a preference under state law. Other

schools give preference to nonresidents.

Preference is sometimes given to children of alumni,

even though at most schools this would work to the

disadvantage of minorities, as does a preference for

those applicants who have famous or wealthy parents.

Cf. Guinn v. United States, 238 U.S. 347 (1915) ;

Meredith v. Fair, 298 P. 2d 696 (C.A. 5, 1962). See

O’Neil, Preferential Admissions: Equalizing the Ac

cess of Minority Groups to Higher Education, 80 Y ale

L. J. 699, 703-05 (1971).

The LSAT score is more closely related to academic

competence, hut it is both an attractive and a dangerous

criterion. It is attractive because it is the sole com

mon denominator among all the applicants and its

three-digit character gives it the appearance of objec

tivity and precision. It is dangerous because at its

best the information which it gives us is limited, and

its appearance may be misleading.

The LSAT is designed to predict success in first year

law school courses; its usefulness in doing this is ac

cepted by almost all law schools. But it has the limita

tions that any test of this type has in that it is subject

to errors of measurement3 and it predicts first year

grades imperfectly. It predicts grades well enough

to be very useful in considering large numbers of stu

dents, but it leaves much uncertainty when individual

8 A score, for example, of 550 indicates that there are two

chances out of three that the score reflecting the true ability of

the individual is between 520 and 580. Thus to prefer the appli

cant with a score of 550 to one with a score of 520 or 530 has

questionable justification. If, therefore, there are one or two

hundred applicants all of whom have scores within 60 points of

each other, the LSAT score is a very dubious basis for comparison.

See Consalus, The Law School Admission Test and the Minority

Student, 1970 U. Toledo L. Rev. 501, 512-13.

7

students are considered. For example, if one is com

paring a student with a 600 to one with a 500 one must

realize that there are many factors which might lead

the 500 student to perform as well as the 600 student.

Motivation, financial problems, family problems, self-

confidence, ability to get along with other students

and with members of the faculty, interest in the

courses, the possibility of illness—these are not meas

ured on the LSAT. See Consalus, supra at 513.

In short, the selection of students for admission to

law school involves the exercise of informed judgment.

A mechanistic ranking of candidates is not necessarily

in the interest of the law school, the legal profession

or society. Here the University of Washington

weighed a multiplicity of factors, and no one factor

was the sole basis for granting or denying admission

to the law school. Accordingly, courts should be very

reluctant to interfere with the difficult exercise of dis

cretion which is required by the law school admissions

process. A law school can be compared to a school

board trying to devise an educationally sound remedy

for racial imbalance and the problems resulting from

unequal education:

“ The School Board, in the operation of the public

schools, acts in much the same manner as an ad

ministrative agency exercising its accumulated

technical expertise in formulating policy after

balancing all legitimate conflicting interests. I f

that policy is one conceived without bias and ad

ministered uniformly to all who fall within its

jurisdiction, the courts should be extremely wary

of imposing their own judgment on those who

have the technical knowledge and operating re

sponsibility for the educational system.” Deal v.

Cincinnati Board of Education, 369 F.2d 55, 61

(C. A. 6, 1966), cert, denied, 389 U.S. 847 (1967).

8

Accord, Swann v. Charlobte-Mecklenburg Board of

Education, 402 U.S. 1 (1971); Wanner v. County

School Board of Arlington County, Virginia, 357 F.2d

452 (C.A. 4, 1966).

II. THE RACIAL AND ETHNIC BACKGROUND OF APPLI

CANTS IS AN APPROPRIATE FACTOR TO CONSIDER

IN DETERMINING ADMISSIONS TO LAW SCHOOL.

W e contend that race and ethnic background is an

appropriate factor to consider in determining who is

or is not admitted to a law school. The consideration

given to race and ethnic background is included as jiart

of the admission formula not because it per se is a

test of the qualifications of an applicant to law school,

but because race and ethnic background represents a

congery of factors—discussed below—that a law

school is justified in taking into account.4 Since these

interrelated factors, unlike race and ethnicity, are not

immutable, wre can expect them to disappear eventu

ally. At such time, the consideration of race and

ethnicity qua race and ethnicity no longer will be ap

propriate.5 But “ [t]he promise of even handed jus-

4 Cf. Springfield School Committee v. Barksdale, 348 F.2d 261,

266 (C.A. 1, 1965) : “ The defendants’ proposed action [eliminat

ing racial concentrations in schools] does not concern race except

insofar as race correlates with proven deprivation of educational

opportunity . . . . It would seem no more unconstitutional to

take into account plaintiffs’ special characteristics and circum

stances that have been found to he occasioned by their color than

it would be to give special attention to physiological, psychological

or sociological variances from the norm occasioned by other fac

tors. That these differences happened to be associated with a

particular race is no reason for ignoring them.”

5 For example, although Asian-Americans, Jewish-Americans,

and Italian-Americans all have been subject to discrimination,

this discrimination and its effects appear not to present a barrier

to their admission to the University of Washington Law School.

9

tice in the future does not bind our hands in undoing

past injustices.” United States v. Louisiana, 252 F.

Supp. 353, 396 (E. D. La. 1963), aff’d, 380 U.S. 145

(1965).

It is unrealistic to suggest that at this time color

blindness is possible in the evaluation of applications

for law school admission. The history of discrimi

nation in the United States based on color, culture,

and language is too long, and the continuing effect of

that discrimination is too clear in the low educational

and economic status of victimized minority groups to

allow color blindness. “ After centuries of viewing

through colored lenses, eyes do not adjust when the

lenses are removed.” Associated General Contractors

of Massachusetts, Inc. v. Altshuler, 6 EPI) U8993

(C.A. 1, 1973). See also, United States v. Jefferson

County Board of Education, 372 F. 2d 836, 876 (C. A.

5, 1966), cert, denied sub nom. Board of Education of

Bessemer v. United States, 389 U.S. 840 (1967).

An admissions committee would face an intractable

task in evaluating the potential of a minority appli

cant if it could not consider the obstacles which the

applicant has had to overcome in his or her academic

and personal development. How can an admissions

committee evaluate in a color blind way the handicap

of a segregated elementary or secondary education,

how can it evaluate the effect on an applicant of being

placed in a class for the mentally retarded in elemen

tary school merely because the student’s primary

language was not English, or how can it evaluate the

effect of attending boarding school hundreds of miles

from home where the student’s language and culture

were systematically denied1? These judgments can

not be made without considering the status of the ap

10

plicant as a member of a victimized minority. As the

Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit noted:

“ How then is this constitutional imperative to be

achieved in a society that still bears the ugly

scars of decades of racial segregation with all of

its discriminations ? For it is in this social struc

ture that the problem arises. And it is in this

social structure—not that of the hoped for idyllic

state when the last vestige of this invidious dis

tinction has gone away—that the constitutional

ideal must be made to work.” Brooks v. Beto,

366 F.2d 1, 22-23 (C.A. 5, 1966).6

A. Purely mechanical criteria are an inadequate basis for

determining the composition of a law school class.

While there are problems present in the interpreta

tion of the grades and the LSAT scores of any appli

cant, with minority applicants these problems are mul

tiplied. With white applicants law schools have had

years of experience in evaluating the significance of

LSAT scores. With minority applicants there is little

experience either at the University of Washington or

at other law schools. The problems peculiarly related

to race with which minorities must cope at all levels

of education can affect college grade averages and re

sults on standardized tests.

The law school had reason to believe that a low score

by a minority applicant on the LSAT might not be

a bar to acceptable performance in law school. Stu

dents who must cope with racially related disadvan

tages throughout their educational careers cannot be

expected to perform as well on the LSAT as other

students but still might have the underlying ability

8 See Pinderhughes, Increasing Minority Group Students in Law

Schools: The Rationale and the Critical Issues, 20 Bur. L. Rev.

447, 454 (1971).

11

to succeed in law school. Even with lower scores or

grades, the minority students accepted at the Wash

ington Law School were found to be qualified. Es

pecially if the student attends a summer session prior

to law school to improve his basic skills and to famil

iarize himself with the study of law and if the faculty

is willing to give extra attention to the needs of minor

ity students, there is a good likelihood that such stu

dents will succeed in law school despite relatively low

PFYAs. Thus to require the school to consider white

and minority applicants together on the basis of their

PFYAs is to require it to do something which would

prevent its taking account of other highly legitimate

considerations discussed herein.

The LSAT is designed to predict first year averages.

More important ultimately, however, is the capability

of the law student at the end of his law school career.

For whites, first year grades generally are a good in

dicator of how well the student will do in the second

and third years. For minorities they may be a less

accurate predictor. Adjusting socially and academic

ally to the demands of law school can be the primary

activity of the first year. Overcoming educational de

ficiencies and gaining needed self-confidence takes

time.

B. The desirabilily of a heterogeneous student body is an

appropriate element of a law school's admission policy.

The University of Washington had sound educa

tional reasons for wanting a multi-racial student

body.7 Many of the most serious legal and public pol

7 Until the last few years the number of minority law students

in the entire country as well as at the University of Washington

was extremely low. In the 1964-65 school year there were ap

proximately 700 black law students, including 267 in predom-

12

icy issues that the lawyer will face in his career are

related to the issues of race and poverty. All students

will gain from having students of different racial and

ethnic backgrounds participate in in-class and out-of

class discussions of these issues and from learning to

live in a multi-racial community.8

Success in law school cannot be viewed as an end

in itself. A law school is a professional school, train

ing men and women to go out into the world and act

as lawyers. The wisdom of Sweatt v. Painter, 339

U jS. 629, 634 (1950), is as relevant today as it was

a generation ago:

“ [A]lthough the law is a highly learned pro

fession, we are well aware that it is an intensely

practical one. The law school, the proving ground

for legal learning and practice, cannot be effective

inantly black schools in the South. This represents only 1.3

percent of the total law school enrollment, barely enough for

blacks to maintain their proportion of the legal profession. O’Neil,

Preferential Admissions: Equalizing Access to Legal Education,

1970 T oledo L. Rev. 281, 300. In the 1967-68 school year, after

many law schools had begun to recruit minority students, there

were only 180 Mexican Americans and 32 American Indians en

rolled in law school. Id. at 301 n. 58. Enrollment figures for

subsequent years are as follows: 1969-70: black, 2128; Mexican

American, 412; American Indian, 72. 1971-72: black, 3732;

Mexican American, 881; American Indian, 140. 1971 Survey of

Minority Group Students in Legal Education, quoted in 1 1972

P roceedings of the A ssociation of A merican Law Schools 74.

8 See Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education, 402

U.S. at 16: “ School authorities are traditionally charged with

broad powder to formulate and implement educational policy and

might well conclude, for example, that in order to prepare

students to live in a pluralistic society each school should have a

prescribed ratio of Negro to white students reflecting the propor

tion for the district as a whole. To do this as an educational

policy is within the broad discretionary powers of school authori

ties . . . . ”

13

in isolation from the individuals and institutions

with which the law interacts. Pew students and

no one who has practiced law would choose to

study in an academic vacuum, removed from the

interplay of ideas and the exchange of view7s with

which the law is concerned. ’ ’

The great increase in the number of qualified -appli

cants to law school,9 coupled with a mechanical use

of the PFYA , threatened to make the University of

Washington Law School into just such an “ academic

vacuum. ’ ’

C. The nature of legal services required by the public is an

appropriate consideration for a law school in constituting

its student body.

The greatest shortage of legal services is in minor

ity communities—ghettos, barrios, reservations. Mem

bers of these communities have been denied an ade

quate number of qualified lawyers and judges who

understand from firsthand experience the seriousness

of the many problems facing these communities and

the urgent need to find both short-range and long-

range solutions. While some white lawyers will prac

tice in these communities and be as effective as a mi

nority lawyer, minority lawyers are more likely to

serve minority communities and in some instances will

be able to provide better service:10 They have greater

9 In the past three years the number of applications had gone

from 704 to 1601. DeFunis v. Odegaard, 82 Wn. 2d at 15 507

P.2d at 1172-73.

10 Few of the nation’s lawyers are minority group members.

In 1966 only about one percent was black. Gellhorn, The Law

School and the Negro, 1968 Duke L.J. 1068, 1073. Even if the

size of the legal profession could be kept constant, an additional

30,000 black attorneys would need to be trained before blacks

would achieve parity in the legal profession. Gellhorn, id. at

14

familiarity with the community and its problems, they

are able to communicate more effectively with the

residents and gain their trust, and—in the case of the

Spanish-speaking community—their ability to speak

the same language is indispensable.11 In some in

stances, the interests of a minority group and those of

whites will be adverse. In such a case the minority

group might be better served by a lawyer who shared

the same interests.

This is not meant to imply that minority law stu

dents should be only trained to and should be ex-

1073. Nationwide figures for Mexican Americans do not appear

to be available. Data from specific areas are suggestive of the

problem, however. In Denver, for example, about nine percent

of the population is Mexican American, yet only 10 of the city ’s

2,000 attorneys (one half of one percent) have Spanish surnames.

O ’Neil, 80 Y ale L.J. at 727. In 1968, less than one percent of

the attorneys in California had a Spanish surname, although 12

percent of the state’s population is of Spanish surname. Reynoso

et al, La Baza, the Law, and the Law Schools, 1970 Toledo L. Rev.

809, 816. In 1968 there were almost no Indian lawyers in the

country. See discussion in Strickland, Redeeming Centuries of

Dishonor: Legal Education and the American Indian, 1970 Toledo

L. Rev. 847, 861-66. With specific reference to the state of Wash

ington, in 1970, of the 4,550 active lawyers, only 20 were blacks

(three of whom were judges), five were part or full-blooded Amer

ican Indians and none was Mexican American. Thus, there was

one Anglo lawyer for approximately every 720 whites, one black

lawyer for approximately every 4,195 blacks, one American Indian

lawyer for approximately every 6,677 Indians and not one Mex

ican American lawyer for the 70,734 Mexican Americans in the

state. Morris, Equal Protection, Affirmative Action and Racial

Preferences in Law Admissions, 49 W ash . L. Rev. 1, 38 (1973).

11 Cf. Graglia, Special Admission of the “ Culturally Deprived”

to Law School, 119 U. P a . L. Rev. 351, 354 (1970), with Twen

tieth Century F und, A dministration of Justice in the South

3 (1967) and Oppenheim, The Abdication of the Southern Bar in

L. F riedman, ed., Southern Justice 127 (1965). See Sobol v.

Perez, 289 F. Supp. 392 (E.D. La. 1968).

15

peeted to serve minority communities. On the con

trary, they should receive the same training as every

other law student and should be free to practice what

ever kind of law in whichever community they choose.12

In fact, there has been an increasing realization by

law firms, government agencies and corporations that

minority lawyers have a vital role to play in fulfilling

the responsibilities of the legal profession, and career

opportunities for minority lawyers outside the mi

nority community are bright.

D, It is appropriate for a law school's admissions policy to be

sensitive to the pivotal role played by the legal profession

in our national life.

Law firms have a leading role in our society, and

lawyers are well represented in public office at all levels

in the local, state, and federal governments, and in

private corporations. W e are ‘ ‘ a nation that professes

deep regard for the dignity of man and that in prac

tice relies to an extraordinary degree upon the advice

of professional lawyers in the formation and execu

tion of policy.” Lasswell & McDougal, Legal Educa

tion and Public Policy: Professional Training in the

Public Interest, 52 Y ale L.J. 203, 291 (1943). The

insight and particular sensitivity which minority

group lawyers and judges can bring to the law as an

institution has been lacking. Thus, if a racial or eth

nic group is to share in the power, responsibility, and

benefits of society it must be well represented among

the legal profession.

The legal profession, moreover, has a special re

sponsibility to set an example for the rest of the na

12 See Bell, Black Students in White Law Schools: The Ordeal

and the Opportunity, 1970 Toledo L. Rev. 539, 551-58.

16

tion for providing equal opportunity and overcoming

the effects of past discrimination, for lawyers have

a special duty to uphold the Constitution and the legal

system.

Minority lawyers also have an important role as

citizens in the minority community. Lawyers often

have leadership roles, and they provide an example to

young people, showing them that it is possible to have

a professional career despite their racial or ethnic

background.

“ The most striking factors underlying motivation

to seek entry into law school may he related to

close personal association with a lawyer as a rela

tive, or a friend, and to encouragement from fam

ily, friends, or counsellors. These factors are too

often missing in law-deprived communities where

there is a lack of exposure to opportunities in

law, and inadequate information and counselling

at all school levels.” Pinderhughes, supra at 454,

E. li is appropriate for the admissions policy of a public law

school to be sensitive to the need to overcome the effects

of past and present illegal discrimination suffered by

minority group members.

1. The paucity of minority lawyers is the result of discrimination.

The factors which have led to the small number of

minority lawyers are many. They are all the result—

direct or indirect—of discrimination and would con

tinue unabated even with “ color blind” treatment.

Accordingly, a significant increase in the number of

minority lawyers cannot he expected without color

conscious efforts.

While not the universal pattern, until recently many

law schools refused to admit blacks, and many blacks

who were able to attend law school could only do so at

17

all Negro institutions. Cf. Sweatt v. Painter, supra. See

Gull horn, supra at 1069-70. As late as 1960 the Duke

University School of Law would not admit blacks,

and in 1962 the University of Richmond refused to ad

mit two blacks because of their race. Gfellhorn, id. at

1070 n. 12. I f a black did manage to graduate from law

school he faced discrimination from bar associations,

law firms, and government agencies. See Gellhorn, id.

at 1070,1093. Thus blacks were discouraged from going

to law school by their prospects after graduation, were

denied admission to law school if they nevertheless

applied, and were less likely to be able to practice law

if they graduated.13

Secondly, discrimination in elementary and sec

ondary education throughout the country makes it

less likely that minorities will attend college and obtain

degrees than whites.14 Since to be admitted to almost

all law schools one must have an undergraduate de

gree, the pool of potential minority applicants to law

school is severely restricted compared to that of

whites.15

is For information concerning the participation of Mexican

Americans and American Indians in the legal profession see

Reynoso, ei al., supra, and Strickland, supra.

14 Nearly twenty year ago, in Brown v. Board of Education, 347

U.S. 483 (1954), this Court noted that school segregation “ has

long been a nationwide problem, not merely one of sectional con

cern.” Id. at 491 n. 6. It continues to be a nationwide problem.

See, e.g., Keyes v. School District No. 1, Denver, Colorado, 413

U.S. 189 (1973).

15 For persons in the 25 to 34 year old bracket in 1970, 16.6

percent of whites had graduated from college, while only 6.1 percent

of blacks, 5.3 percent of persons of Spanish heritage, 1.1 percent

of Indians, and 3.6 percent of Philippine Americans. Bureau op

the Census BLS Report No. 394, Series P-23 No. 38, Table 67;

U. S. B ureau op the Census, 1970 Census op Population, PC

(2 )lc , Table 6, PC (2 )If, Table 5, P C (2)lg , Table 35.

18

Thirdly, the combined effect of discrimination in

education and employment has resulted in minorities

having a lower median family income than whites.16

They are thus less able to afford the expense of law

school. Lower incomes also make it more burden

some to postpone full time employment for three

years.

The effects of discrimination in education and em

ployment and other areas of life are continuing and

cumulative. Color blindness will not help a law school

remedy the effects of these barriers. Indeed, when a

remedy for past discrimination is being fashioned the

consideration of race becomes necessity:

‘ ‘What we have said may require classification by

race. That is something which the Constitution

usually forbids, not because it is inevitably an

impermissible classification, but because it is one

which usually, to our national shame, has been

drawn for the purpose of maintaining racial in

equality. Where it is drawn for the purpose of

achieving equality it will be allowed, and to the ex

tent it is necessary to avoid unequal treatment by

race, it will be required.” Norwalk GORE v.

Norwalk Redvelopment Agency, 395 F.2d 920, 931

(C.A. 2, 1968).

See also McDaniel v. Barresi, 402 U.S. 39, 41 (1971).

18 In 1972 the median income of Negro families was $6,864 as

compared to $11,549 for whites. U. S. Bureau of Census, Cur

rent P opulation R eports, Series P-23, No. 46, Table 7 (1972).

19

2. Voluntary remedial action is not dependent upon a finding of

discrimination.

Since the effects of discrimination are pervasive

throughout American society, it is appropriate for all

institutions to take affirmative action to overcome

racial inequalities. Courts have not found the ab

sence of preexisting discrimination a. bar to school

boards’ taking voluntary action to increase racial bal

ance within them. Offerman v. Nitowski, 378 F.2d

22, 24 (C.A. 2, 1987).17 Although Swarm v. Char-

lotte-Mechlenburg, supra, arose in the context of

the dismantling of a state required dual school

system, it suggested that voluntary remedial action is

permissible. 402 U.S. at 16; North Carolina State

Board of Education v. Swann, 402 XJ.S. 43, 45 (1971).

Accord, Wanner v. County School Board of Arlington

County, Virginia, 357 F.2d at 454. Where courts have

declined to order a remedy for de facto segregation

they have indicated that voluntary remedies are

allowed. Beal v. Cincinnati Board of Education, 369

17 Accord, Fuller v. Yolk, 230 F. Supp. 25 (D.N.J. 1964), vacated

on other grounds, 351 F.2d 323 (C.A. 3, 1965), adhered to on the

merits, 250 F. Supp. 81 (D.N.J. 1966) ; Guida v. Board of Educa

tion, 26 Conn. Supp. 121, 213 A.2d 843 (Super. Ct. 1965) ; Morean

v. Board of Education, 42 N.J. 237, 200 A.2d 97 (1964) ; Addabbo

v. Donovan, 16 N.Y.2d 619, 209 N.E.2d 112, 261 N.Y.S.2d 68 (1965)

cert, denied, 382 U.S. 905 (1965) ; Balaban v. Rubin, 14 N.Y.2d

193, 199 N.E.2d 375, 250 N.Y.S.2d 281, cert, denied, 379 U.S. 881

(1964). Similarly, courts have held that state legislative or ad

ministrative action requiring school boards to take racially con

scious actions to eliminate racial imbalance need not be based on

any past or present discrimination. Tometz v. Board of Educa

tion, Waukegan City, 39 I11.2d 593, 237 N.E.2d 498 (1968) ; School

Committee of Boston v. Board of Education, 352 Mass. 693, 227

N.E.2d 729 (1967), appeal dismissed, 389 U.S. 572 (1968) ; Booker

v. Board of Education, 45 N.J. 161, 212 A.2d 1 (1965); Balsbaugh

v. Rowland, 447 Pa. 423, 290 A.2d 85 (1972).

20

F.2d at 65; Springfield School Committee v. Barks

dale, 348 F.2d at 265-66.

In the area of employment affirmative action to in

crease the number of minority employees also has

been allowed without a judicial finding that a par

ticular employer or union engaged in discriminatory

behavior. In Porcelli v. Titus, 431 F.2d 1254 (C.A.

3, 1970), cert, denied, 402 U.S. 944 (1971), the Third

Circuit allowed the Newark School Board to dis

continue the use of a promotion list established in

1953 and of oral and written tests used to determine

who was qualified to become a principal or assistant

principal. While the small number of black princi

pals and assistant principals (3 out of 139) might

have supported a finding of discrimination, the court

did not rely on such a finding nor did it consider

whether the tests employed were job related or

whether any other evidence of discrimination was pres

ent. The court instead relied on the relevance of

color to the job. Cf. Chance v. Board of Examiners,

458 F.2d 1167 (C.A. 2,1972); Local 189, United Paper-

makers and, Paper workers, AFL-CIO v. United

States, 416 F.2d 980, 991 (C.A. 5, 1969), cert, denied,

397 U.S. 919 (1970). See also Contractors Associa

tion of Eastern Pennsylvania v. Secretary of Labor,

442 F.2d 159 (C.A. 3, 1971), cert, denied, 404 U.S. 854

(1971).

In Nortvalk CORE v. Norwalk Redevelopment

Agency, supra, the Agency was required to take race

into account in providing relocation housing because

discrimination in the housing market made it more

difficult for blacks than for whites to find legally

adequate housing. There was no suggestion that the

Agency was responsible for the discrimination, and

21

at that time discrimination in the private housing

market was not considered illegal.

The situation of the law school is similar to that of

the school boards, the employers or unions, and the

redevelopment agency.

The law school can be viewed as the last step in

an educational process that was permeated by illegal

discrimination and segregation. It is justified in

taking into account the “ broader patterns of exclusion

and discrimination practiced by third parties and

fostered by the whole environment in which most

minorities must live.” Johnson v. Pike Corporation

of America, 332 F. Supp. 490, 496 (C.D. Cal. 1971).

Accordingly, it is no less permissible for a school to

take into account and seek to remedy discrimination

by other parts of the nation’s educational system than

it is to remedy its own. Cf. Oregon v. Mitchell, 400

U.S. 112, 133, 146-47, 216-17, 282-84 (1970); Gaston

County v. United States, 395 U.S. 285 (1969).

Although there has been no allegation that the Uni

versity of Washington Law School or the state of

Washington discriminated in any way against minori

ties, the small number of minority students at the law

school in prior years might reasonably have led the

school to be concerned that its admissions policies had

in fact had a discriminatory effect.

In short, if courts have required governmental

agencies to remedy discrimination which they did not

cause, Norwalk CORE, supra, surely this Court should

allow the law school to remedy such discrimination.

3. Remedial action may impinge on the expectations of others.

Both governmental and private action in our so

ciety typically disadvantages some people—either di

22

rectly or incidentally—as it benefits others. This is as

true for actions taken to remedy racial inequalities as

it is in other areas.

In employment cases where affirmative action plans

are ordered or upheld there is generally some harm to

potential white employees. As Judge Marvin

Frankel said in discussing the remedies of Title V II

of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. §§ 2000e

et seq.:

“ [I ] t should be recognized . . . that the remedies

Congress ordered are not required to be utterly

painless. The court knows at least some of the

things the whole world knows. We are aware

that there is unemployment. W e are even more

keenly aware that this case is launched by statu

tory commands, rooted in dee]) constitutional

purposes, to attack the scourge of racial discrimi

nation in employment.” United States v. Wood,

W ire and Metal Lathers International Union,

Local Union 46, 341 F. Supp. 694, 699 (S.IXN.Y.

1972), aff’d., 471 F.2d 408 (C.A. 2, 1973), cert,

denied, 412 U.S. 939 (1973).

In Porcelli v. Titus, supra, individual whites did not

receive the promotions which they thought they had

every reason to expect. While in most instances

there will be no identifiable whites who are deprived

of a job or a promotion, there will be a more or less

readily identifiable class of whites potentially eligible

for work or promotion. See Carter v. Gallagher, 452

F. 2d 315, modified en hanc, 452 F.2d 327 (C.A. 8,

1972), cert, denied, 406 U.S. 950 (1972); Contractors

Association of Eastern Pennsylvania v. Secretary of

Labor, supra; United States v. Bethlehem Steel Corpo

ration, 446 F. 2d 652, 663 (C.A. 2, 1971) ; Associated

General Contractors of Massachusetts, Inc. v. Alt

shuler, supra.

23

Likewise the fact that whites (or blacks) might be

inconvenienced by steps taken to dismantle a dual

school system is not considered an argument with any

weight.

“ The remedy for such segregation may be ad

ministratively awkward, inconvenient, and even

bizaare in some situations and may impose bur

dens on some; but all awkwardness and inconven

ience cannot be avoided in the interim period

when remedial adjustments are being made to

eliminate the dual school systems.” Stvann v.

Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education, 402

U.S. at 28.

In this case, as in cases remedying inequality in

employment and education, the remedial action had

an effect on who received the benefits of legal training

by the University of Washington Law School. The

remedy here was designed to eradicate the effects of

past discrimination. To the extent that there were

those whose expectations rested on the continuation of

a system which perpetuated discrimination, they were

likely to suffer some disappointment. But this dis

appointment was mild in comparison to what courts

have allowed.18

18 Petitioner is not necessarily among those damaged by the

school’s action. Even if none of the 36 minority students had been

admitted, his position on the waiting list would not have given

him a position in the class. On the other hand, if the whole ad

missions process were to be done over using new criteria or pro

cedures, there is no guarantee that he would be admitted.

24

CONCLUSION

For all these reasons the University of Washington

Law School exercised proper discretion in admitting

students to the class entering in the fall of 1971, and

the judgment of the Washington Supreme Court

should therefore be affirmed.

Respectfully submitted,

H oward A. Glickstein

M ichael B. W ise

Center for Civil Rights

University of Notre Dame

Notre Dame, Indiana 46556

D avid H. H unter

Washington, D.C.

Attorneys for Amici