Index to Hardback 1

Public Court Documents

May 6, 1996 - September 20, 1996

1 page

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Campaign to Save our Public Hospitals v. Giuliani Hardbacks. Index to Hardback 1, 1996. 2e5c128f-6835-f011-8c4e-0022482c18b0. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/71125d28-a563-4c62-89aa-a99ebdc12b6e/index-to-hardback-1. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

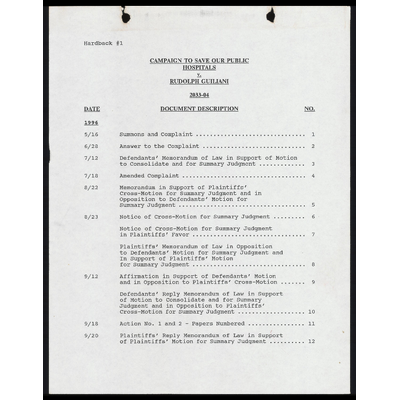

Hardback #1

CAMPAIGN TO SAVE OUR PUBLIC

HOSPITALS

V.

RUDOLPH GUILIANI

2033-04

DATE DOCUMENT DESCRIPTION NO.

1996

5/16 Summons and Complaint «occ ivives ss ess tnvnrnnsvras ne sas 1

6/28 Answer To the2Complaint sues vent vnsssssvmsivniosnvens 2

7/12 Defendants’ Memorandum of Law in Support of Motion

to Consolidate and for Summary Judgment ............. 3

7/18 Amended COMPLAINT 0 vais sviss vesnmsinimnsssain’s suidonen sinnsie 4

8/22 Memorandum in Support of Plaintiffs’

Cross-Motion for Summary Judgment and in

Opposition to Defendants’ Motion for

SUNMNATY JUAGMEIIE vis sinner 00 vv sss esis esnesnivnsonsensnss 5

8/23 Notice of Cross-Motion for Summary Judgment ......... 6:

Notice of Cross-Motion for Summary Judgment

IN PlalnNtiffS, FAVOL saves svonenssnbsnsnnsnmennvens 7

Plaintiffs’ Memorandum of Law in Opposition

to Defendants’ Motion for Summary Judgment and

In Support of Plaintiffs’ Motion

FOr SUMMATY JUOGMONL os evs tse rssnriosvessesntosonsonse 8

9/12 Affirmation in Support of Defendants’ Motion

and in Opposition to Plaintiffs’ Cross-Motion ....... 9

Defendants’ Reply Memorandum of Law in Support

of Motion to Consolidate and for Summary

Judgment and in Opposition to Plaintiffs’

Cross-Motion for Summary Judgment ....ccssessssuvsees 10

9/18 Action No. 1 and 2 - Papers Numbered .. v.esesvsesasins 31

9/20 Plaintiffs’ Reply Memorandum of Law in Support

of Plaintiffs’ Motion for Summary Judgment .......... 12