Barr v. Columbia Brief Opposing Petition for Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

May 3, 1962

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Barr v. Columbia Brief Opposing Petition for Writ of Certiorari, 1962. 582c378a-be9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/71780b73-8f81-497d-bc20-9caa8a9bd799/barr-v-columbia-brief-opposing-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

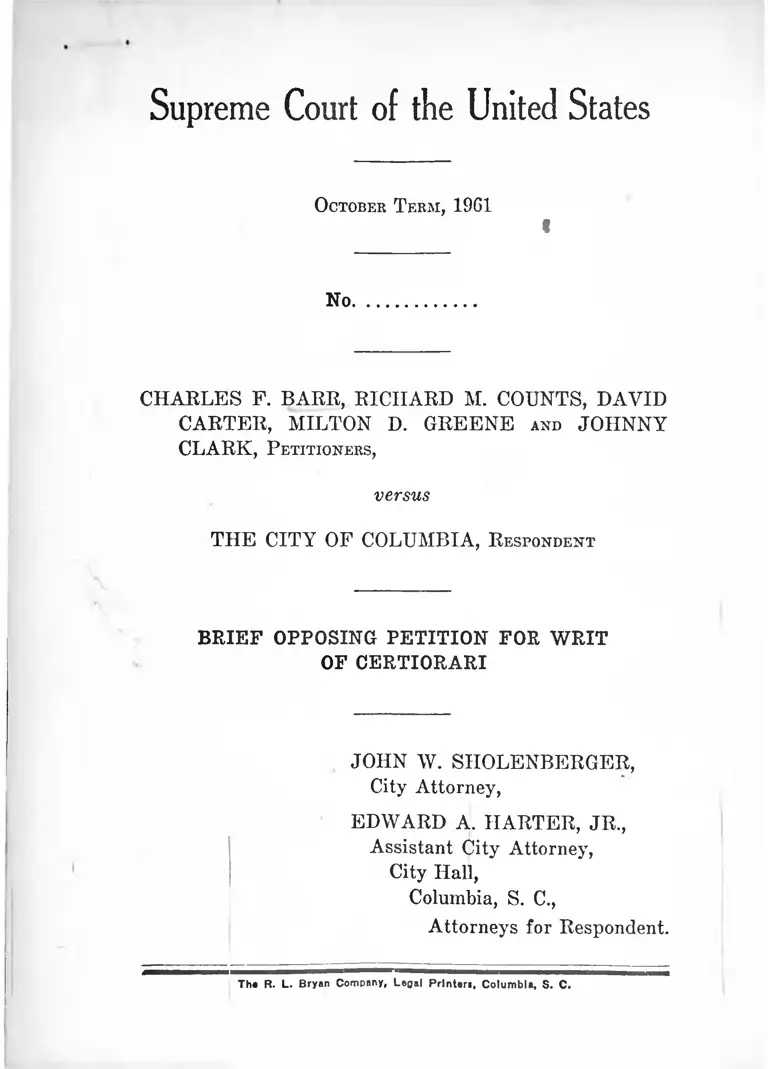

Supreme Court of the United States

October T erm, 1961

I

No

CHARLES F. BARR, RICHARD M. COUNTS, DAVID

CARTER, MILTON D. GREENE and JOHNNY

CLARK, P etitioners,

versus

THE CITY OF COLUMBIA, R espondent

BRIEF OPPOSING PETITION FOR WRIT

OF CERTIORARI

JOHN W. SHOLENBERGER,

City Attorney,

EDWARD A. HARTER, JR.,

Assistant City Attorney,

City Hall,

Columbia, S. C.,

Attorneys for Respondent.

Tha R. L. Bryan Company, Looal P rln ta ri. Columbia. S. C.

INDEX

P age

Statement ......................................................................... 1

Reasons for Denying the Writ:

L The Petitioners Were Trespassers and Were

Subject to Being Ejected or Arrested Without

Violating Their Rights Under the Fourteenth

Amendment ....................................................... 3

II. The Decision of the Supreme Court of South

Carolina Granted Petitioners All Rights to

Freedom of Expression to Which They Were

Entitled Under the Fourteenth Amendment to

the Constitution of the United S ta te s ............ 6

III. The Question of the Conviction of Petitioners

for Breach of the Peace in Violation of Sect.

15-909 of the Code of Laws of South Carolina,

1952, in Addition to the Conviction for Tres

pass Under Section 16-386 of Said Code, Has

Never Been Properly R aised............................ 8

Conclusion ........................................................................ 9

I

*

!

TABLE OF CASES

P age

Alpaugh v. Wolverton, 36 S. E. (2d) 906, 184 Va. 943 .. 4

City v. Mitchell, . . . . S. C........ , 123 S. E. (2d) 512 . . . . 6

Garner v. Louisiana, 368 U. S. 157, 7 L. Ed. (2d) 207,

82 S. Ct. 248 .................................................................. 3

Marsh v. Alabama, 326 U. S. 501, 66 S. Ct. 276, 90 L.

Ed. 265 .......................................................................... 8

Shramek v. Walker, 152 S. C. 88, 149 S. E. 331......... 4, 6

Slack v. Atlantic White Tower System, Tnc., 284 F.

(2d) 747 ........................................................................ 4

State v. Lazarus, 1 Mills, Constitution (8 S. C. L.) 34

4, 6

Williams v. Howard Johnson’s Restaurant, 268 F. (2d)

845 ................................................................................. 4

STATUTES

South Carolina Code, Sec. 15-909 ................................... 8

South Carolina Code, 1952, as Amended, Sec. 16-386

5,7, 8

General Statutes of South Carolina (1882) ................... 5

1883 Acts of South Carolina (18) Page 4 3 .................... 5

1S98 Acts of South Carolina (22) Page 811 .................. 5

1954 Acts of South Carolina (48) Page 1705 ................. 5

OTHER AUTHORITIES

Webster’s New International Dictionary (Second Edi

tion) “Land” ................................................................ 6

( i i )

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1961

No

CHARLES F. BARR, RICHARD M. COUNTS, DAVID

CARTER, MILTON D. GREENE and JOHNNY

CLARK, P etitioners,

versus

THE CITY OF COLUMBIA, R espondent

BRIEF OPPOSING PETITION FOR WRIT

OF CERTIORARI

STATEMENT

We adopt as our Statement the summary of the pro

ceedings in the Recorder’s Court as given by Mr. Justice

Oxner for the Supreme Court of South Carolina:

“The five appellants, all Negroes, were convicted in

the Municipal Court of The City of Columbia of trespass

in violation of Section 16-386 of tbe 1952 Code, as amended,

and of breach of the peace in violation of Section 15-909.

Each Defendant Avas sentenced to pay a fine of $1.00.00 or

serve a period of thirty days in jail on each charge but

2 Bark et a l , Petitioners, v. City of Columbia, Respondent

r

$24.50 of the fine was suspended. From an order of the

Richland County Court affirming their conviction, they

have appealed.

“The exceptions can better be understood after a re

view of the testimony. The charges grew out of a ‘sit-down’

demonstration staged by appellants at the lunch counter of

the Taylor Street Pharmacy in The City of Columbia, a

privately owned business. In addition to selling articles

usually sold in drugstores, this establishment maintains a

lunch counter in the rear, separated from the front of the

store by a partition. The customers sit on stools. The policy

of this store is not to serve Negroes at the lunch counter

although they are permitted to purchase food and eat it

elsewhere. In a sign posted the privilege of refusing serv

ice to any customer was reserved.

“Shortly after noon on March 15, 1960, appellants, then

college students, according to a prearranged plan, entered

this drugstore, proceeded to the rear and sat down at the

lunch counter. The management had heard of the proposed

demonstration and had notified the officers. To prevent any

violence, three were present when appellants entered. As

soon as they took their seats several of the customers at

the counter, including a White woman next to whom one

of appellants sat, stood up. The manager of the store then

came back to the lunch counter. He testified that the situa

tion was quite tense, that you ‘could have heard a pin drop

in there’, and that ‘everyone was on pins and needles, more

or less, for fear that it could possibly lead to violence.’ He

immediately told appellants that they would not be served

and requested them to leave. They said nothing and con

tinued to sit. At the suggestion of one of the officers, the

manager then spoke to each of them and again requested

that they leave. One of them stood up and inquired if he

could ask a question. As this was done, the other four ap

pellants arose. The manager replied that he did not care to

Bark et al., Petitioners, v. City of Columbia, Respondent 3

enter into a discussion and a third time told appellants to

leave. Instead of doing so, they resumed their seats. After

waiting several minutes, the officers arrested all of them

and took them to jail.

“The foregoing summary is taken from the testimony

offered by the State. Only two of the appellants testified.

They denied that the manager of the store requested them to

leave. They testified that an employee at the lunch counter

stated to them, ‘You might as well leave because I ain’t

going to serve you’, which they did not construe as a spe

cific request. They said after it became apparent that they

were not going to be served, they voluntarily left the lunch

counter and as they proceeded to do so, were arrested. They

denied that any of the White customers got up when they

sat down, stating that these customers did so only after the

employee at the lunch counter said: ‘Get up, we will get

them out of here.’ ”

REASONS FOR DENYING THE WRIT

I

The Petitioners Were Trespassers and Were Subject

to Being Ejected or Arrested Without Violating Their

Rights Under the Fourteenth Amendment.

This case does not come within the rule of Garner v.

Louisiana, 368 U. S. 157, 7 L. Ed. (2d) 207, 82 S. Ct. 248.

Petitioners were “sit-ins” but they were not arrested for

merely sitting or demonstrating. They were arrested only

after the owner of the private lunch counter asked them to

leave the premises and they failed or refused to do so. They

were trespassers then, if not before, both under common

and statutory law and were arrested and convicted as such.

The lunch counter was privately owned, was within a

privately owned drugstore in a privately owned building on

privately owned ground and was engaged purely in local

4 Barr et al., Petitioners, v. City of Columbia, Respondent

commerce. The rights and duties of the proprietor were like

those of a restaurant not an inn. As stated in Alpaugh v.

Wolverton, 36 S. E. (2d) 906, 184 Va. 943, “He [the pro

prietor] is under no common law duty to serve everyone

who applies to him. In the absence of statute, lie may ac

cept some customers and reject others on purely personal

grounds.”

. Such proprietor violates no constitutional provisions

if he makes a choice on the basis of color. Williams v. How

ard Johnson’s Restaurant, 268 F. (2d) 845; Slack v. Atlan

tic White Toiver System, Inc., 284 F. Ed. 747(1960).

If petitioners had no right to be served, the proprietor

could as he did here, ask them to leave and upon their re

fusal to comply with his request, they became trespassers.

This has always been the law in South Carolina.

In State v. Lazarus, 1 Mill, Const. (8 S. C. Law) 31,

(1817), the South Carolina Constitutional Court said: * * *

“the prosecutor having business to transact with him [the

defendant], had a right to enter his house and if he re

mained after having been ordered to depart, might have

been put out of the house, the defendant using no more vio

lence than was necessary to accomplish this object, and

showing to the satisfaction of the court and judge, that this

was his object.”

In Sliramek v. Walker, 152 S. C. 88, 149 S. E. 331

(1929), the Supreme Court of South Carolina quoted the

rule as stated above in the Lazarus case, then quoted fur

ther with approval from 2 R. C. L., 559, as follows:

“Therefore, while the entry by one person on the

premises of another may be lawful, by reason of ex

press or implied invitation to enter, his failure to de

part, on the request of the owner, will make him a tres

passer and justify the owner in using reasonable force

to eject him.”

Bark et at., Petitioners, v. City of Columbia, Respondent 5

Neither of the above cases involved questions of race.

In addition to becoming trespassers at common law,

petitioners also violated Section 16-386 of the Code of Laws

of South Carolina, 1952, as amended. The section was ap

parently first enacted in 1866. In the General Statutes of

South Carolina (1882), it read as follows:

“Sec. 2507. Every entry on the enclosed or unen

closed land of another, after notice from the owner or

tenant prohibiting the same shall be a misdemeanor.”

An Amendment of 1883 left out the words' “ the en

closed or unenclosed” and added punishment by fine of not

more than $100.00 or imprisonment of not more than 30

days, 1883 Acts, etc. of South Carolina (18), page 43.

An Amendment of 1898 made the jjosting and publish

ing of notice conclusive as to those making entry for hunt

ing and fishing. 1898 Acts, etc. of South Carolina (22),

page 811.

The Amendment of 1954 was tied in with an Amend

ment to Section 16-355 increasing the penalty for larceny

of livestock and as such added the words “ where any horse,

mule, cow, hog or any livestock is pastured, or any other

lands of another” , eliminated the requirement for publish

ing the notice and changed the conclusiveness of notice

from the purpose of hunting and fishing to that of tres

passing. 1954 Acts, etc. of South Carolina (48), page 1705.

The section thus read at the time petitioners were ar

rested in 1960, as follows:

“Sec. 16-386. Entry on lands of another after no

tice prohibiting same. Every entry upon the lands of

another where any horse, mule, cow, hog, or any other

livestock is pastured, or any other lands of another,

after notice from the owner or tenant prohibiting such

entry, shall be a misdemeanor and be punished by a

fine not to exceed one hundred dollars, or by imprison

ment with hard labor on the public works of the county

6 Barr et al., Petitioners, v. City op Columbia, Respondent

for not exceeding thirty days. When any owner or ten

ant of any lands shall post a notice in four conspicuous

places on the borders of such land prohibiting entry

thereon, a proof of the posting shall be deemed and

taken as notice conclusive against the person making

entry as aforesaid for the purpose of trespassing.”

The pertinent language, however, has remained the

same for many years: “Every entry upon lands of another

* * * after notice from the owner or tenant prohibiting such

entry, shall loe a misdemeanor. * * *”

The South Carolina Supreme Court made no strained

nor novel interpretation in applying the section to peti

tioners. In Webster’s New International Dictionary (Sec

ond Edition) “land” as used in “law” is defined as follows:

“a. Any ground, soil, or earth whatsoever, re

garded as the subject of ownership, as meadows, pas

tures, woods, etc. and everything annexed to it, whether

by nature, as trees, water, etc., or by man as buildings,

fences, etc., extending indefinitely vertically upwards

and downwards.

“b. An interest or estate in land, loosely, any tene

ment or hereditament.”

And the South Carolina Supreme Court simply fol

lowed the common law rule as stated in the Lazarus and

Walker cases, supra, in applying the rule that a person may

become a trespasser by refusing to leave even though his

entry may have been lawful. City v. Mitchell, filed Dec. 13

1961, . . . . S. C........ ,123 S. E. (2d) 512.

II

The Decision of the Supreme Court of South Carolina

Granted Petitioners All Rights to Freedom of Expression

to Which They Were Entitled Under the Fourteenth

Amendment to the Constitution of the United States.

There is no question but if a White man or a group of

White men had gone into Taylor Street Pharmacy on the

Barr et al., Petitioners, v. City of Columbia, Respondent 7

day in question, had sat down, expecting service, had been

told that they would not be served, and were further asked

to leave but refused to do so, that they would have been

guilty of violating Sec. 16-386 of the Code of Laws of

South Carolina, 1952, as amended.

If Petitioners’ argument is understood, however, Peti

tioners urge that because they were Negroes and the own

ers of the lunch counter White, their right to protest ex

ceeded their right to be served.

Is the right to protest greater than the right to con

cur? The Fourteenth Amendment states simply and clearly

that no State shall “deny to any person within its jurisdic

tion the equal protection of the laws.”

The “ freedoms” guaranteed by the Constitution do

not give a person a license to stand in a prohibited place

to protest where he could not have stood to concur. Rather,

the Constitution guarantees that a person standing where

he has a right to stand, shall not be moved from that place

by the State because of his protest, if his protest is within

the protection of the Constitution.

As a practical matter, however, Petitioners were per

mitted to give full range to their protest. As they state on

pages 19 and 20 of their Petition for Writ of Certiorari:

“Petitioners were engaged in the exercise of free

expression by means of nonverbal requests for nondis-

criminatory lunch counter service which were implicit

in their continued remaining at the lunch counter when

refused service. The fact that sit-in demonstrations are

a form of protest and expression was observed in Mr.

Justice Harlan’s concurrence in Garner v. Louisiana,

supra. Petitioners’ expression (asking for service) was

entirely appropriate to the time and place at which it

occurred. Petitioners did not shout, obstruct the con

duct of business, or engage in any expression which

had that effect. There were no speeches, picket signs,

handbills or other forms of expression in the store

8 Barr et at., Petitioners, v. City of Columbia, Respondent

which were possibly inappropriate to the time and

place. Rather petitioners merely expressed themselves

by offering to make purchases in a place and at a time

set aside for such transactions.”

The owner told them that they would not be served and

asked them to leave. It was only after they refused to com

ply with this request that they were arrested.

What more did petitioners want to do to express their

protest! Continue to sit! For how long! Who decides when

they shall leave!

This was not a street, private or otherwise, as was in

volved in Marsh v. Alabama, 326 U. S. 501, 66 S. Ct. 276,

90 L. Ed. 265, where a person enters and stands as a mat

ter of right but a private lunch counter in local commerce

where a person enters and stands (or sits) upon invitation,

express or implied, of the owner. The law decides how long

a person has the right to remain on a street but the owner

decides who shall remain in his store, and how long.

Ill

The Question of the Conviction of Petitioners for

Breach of the Peace in Violation of Sect. 15-909 of the Code

of Laws of South Carolina, 1952, in Addition to the Convic

tion for Trespass Under Section 16-386 of Said Code, Has

Never Been Properly Raised.

As stated by the Supreme Court of South Carolina in

this case, in the last paragraph of its opinion:

“In oral argument counsel for appellants raised

the question of merger of the two offenses and argued

that there could not be a conviction on both charges.

But this question is not raised by any of the exceptions,

is not referred to in the brief of appellants and, there

fore, is not properly before us.”

9Barr et al., Petitioners, v . City of Columbia, Respondent

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, it is respectfully submitted that the Su

preme Court of South Carolina decided all federal ques

tions of substance in the case in accordance with applicable

decisions of this Court and the Petition for Writ of Cer

tiorari should be denied.

All of which is respectfully submitted.

JOHN W. SHOLENBERGER,

City Attorney,

EDWARD A. HARTER, JR.,

Assistant City Attorney,

City Hall,

Columbia, S. C.,

Attorneys for Respondent.

Columbia, S. C.,

May 3, 1962.