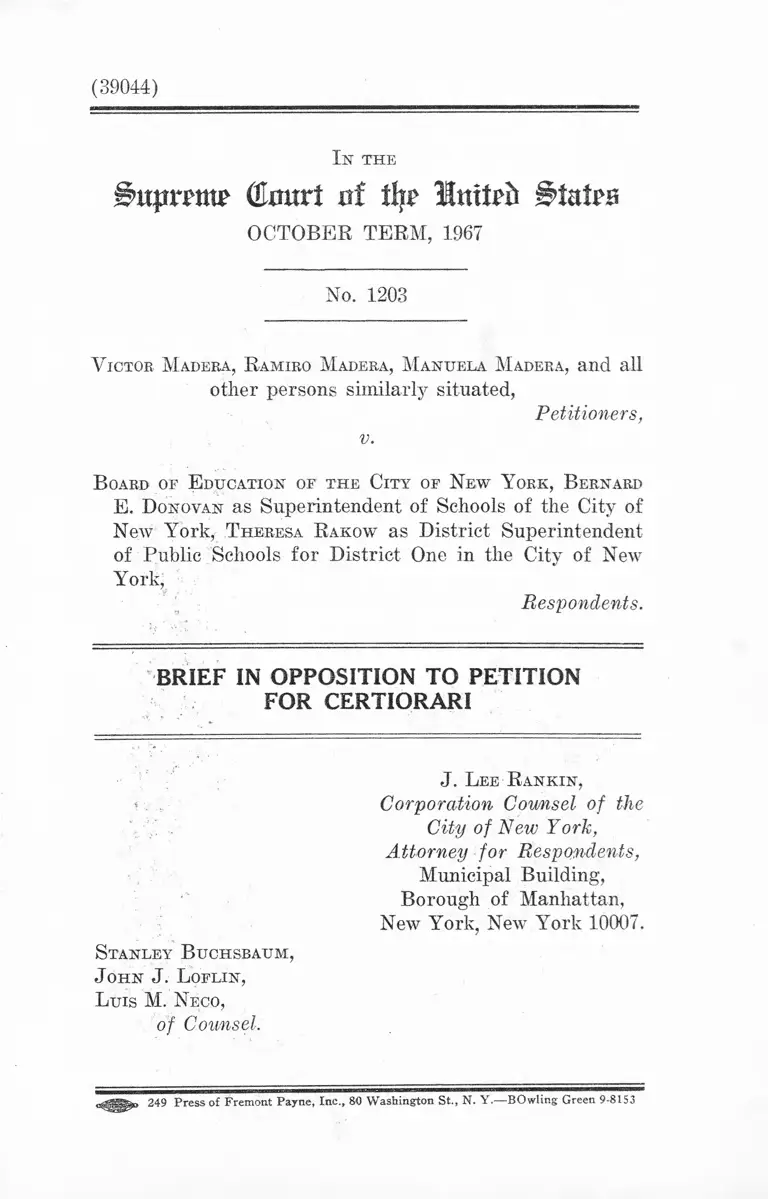

Madera v. Board of Education of City of New York Brief in Opposition to Petition for Certiorari

Public Court Documents

April 5, 1968

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Madera v. Board of Education of City of New York Brief in Opposition to Petition for Certiorari, 1968. 379283d2-bc9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/71997fcb-360c-424a-ab38-b7f0292dc48a/madera-v-board-of-education-of-city-of-new-york-brief-in-opposition-to-petition-for-certiorari. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

(39044)

I n t h e

(£mvt of % Inttsb Stairs

OCTOBER TERM, 1967

No. 1203

V ictor Madera, R amiro Madera, Manuela Madera, and all

other persons similarly situated,

Petitioners,

v.

B oard of E ducation of the City of New Y ork, B ernard

E. Donovan as Superintendent of Schools of the City of

New York, T heresa R akow as District Superintendent

of Public Schools for District One in the City of New

York,

Respondents.

BRIEF IN OPPOSITION TO PETITION

FOR CERTIORARI

J. L ee R ankin,

Corporation Coimsel of the

City of New York,

Attorney for Respondents,

Municipal Building,

Borough of Manhattan,

New York, New York 10007.

Stanley B uchsbaum,

J ohn J. Loflin,

L uis M. Neco,

of Counsel.

249 Press o f Fremont Payne, Inc., 80 Washington St., N. Y .— BOwling Green 9-8153

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PAGE

Statement ......................... 1

Question Presented ......................... 2

Facts ................................................................................. 3

The Decisions B elow .................................. 6

Point I—The nature of the guidance conference is

informal and not adversary. Legal counsel under

these circumstances is not required.......................... 8

P oint II—The exclusion of attorneys f rom participa

tion in a guidance conferences does not violate

the requirements of due process of la w .............. 10

A. Guidance conference procedure...................... 10

B. The requirements of due p rocess .................. U

C. There is no due process requirement for

counsel at an informal proceeding such as a

suspension guidance conference .................... 13

D. Review proceeding available to set aside the

results of a guidance conference .................. 14

Conclusion ......................................................................... 17

T able oe A u t h o r it ie s

Cases:

Application of Olson, 40 Mise 2d 246, 242 N.Y.S. 2d

1002 (1963 ).................................................................... 15

Cafeteria and Restaurant Workers Union v. McElroy,

367 IT. S. 886, 81 S. Ct. 1743, 6 L. ed. 2d 1230

11 TABLE OF CONTENTS

PAGE

(1961) ............... 12

Cosme v. Board of Education, 50 Mise 2d 344, 270

N.Y.S. 2d 231 (1966) ................................................ 16

Escobedo v. Illinois, 378 U. S. 478, 84 S. Ct. 1758, 12

L. ed. 2d 977 (1964) .................................................. 14

Escoe v. Zerbst, 259 U. S. 490, 55 S. Ct. 818, 79 L. ed.

1560 (1935) ............................................................... 12

Garrity v. New Jersey, 385 II. S. 493, 87 S. Ct. 616,

16 L. ed. 2d 205 (1967) .......................................... 14

Hannah v. Larche, 363 U. S. 420, SO S. Ct. 1502, 4 L.

ed. 2d 1307 (1960) ................................................... 12

In re Gault, 387 TJ. S. 1, 87 S. Ct. 1428, 18 L. ed. 2d

527 (1967) ................................................................. 11

In re Groban, 352 11. S. 330, 77 S. Ct. 510, 1 L. ed. 2d

376 (1957) .......................................................... . ...1 3 ,1 6

Kent v. United States, 383 IT. S. 541, 80 S. Ct. 1045,

16 L. ed. 2d 84 (1966) ............................................. 11

Matter of Sheffel, 73 N. Y. St. Dept. Rep. 1 0 4 .......... 15

Matter of Yonkes, 78 N. Y. St. Dept. Rep. 6 6 ........... . 15

Miranda v. Arizona, 384 U. S. 436, 86 S. Ct. 1602, 16

L. ed. 2d 694 (1966) ..................................... 14

O’Brien v. Commissioner of Education, 4 N Y 2d 140,

173 N.Y.S. 2d 265,149 N. E. 2d 705 (1958 ).......... 15

Palko v. Connecticut, 302 U. S. 319, 58 S. Ct. 149, S2

L. ed. 288 (1937) ..................................................... 13

Powell v. Alabama, 287 U. S. 45, 53 S. Ct. 55, 77 L. ed.

158 (1932) ................................................................. 13

Prentiss v. Atlantic Coast Line, 211 U. S. 210, 29 S.

Ct. 67, 53 L. ed. 150 (1908) ..................................... 12

PAGE

Reaves v. Ainsworth, 219 IT. S. 296, 31 S. Ct. 230, 55

L. ed. 225 (1911) ..................................................... 12

Spevack v. Klein, 385 U. S. 511, 87 S. Ct. 625, 17 L.

ed. 2d 574 (1967) ..................................................... 14

Statutes:

New York Education Law sec. 3 1 0 ...............................14,15

New York Education Law sec. 311 .............................. 14,15

New York Education Law sec. 3214.............................. 14

New York Family Court Act sec. 7 4 1 .......................... 14

New York Family Court Act sec. 744 .......................... 14

New York Family Court Act sec. 758 .......................... 14

New York Civil Practice Law and Buies, Article 78

(§§ 7801-7806) ........................................................... 16

Rules and Procedure:

New York City Board of Education, General Circular

No. 16 ......................................................................... 4

TABUS OF CONTENTS 111

Ik the

B>upnw (tart at % lutteb Blalra

OCTOBER TERM, 1967

No. 1203

V ictor Madera, R amiro Madera, Manuela M adera, and all

other persons similarly situated,

Petitioners,

v.

B oard of E ducation of the City of New Y ork, B ernard

E. Donovan as Superintendent of Schools of the City of

New York, T heresa R akow as District Superintendent

of Public Schools for District One in the City of New

York,

Respondents.

------------------- ♦----------------------

BRIEF IN OPPOSITION TO PETITION

FOR CERTIORARI

Statement

Petitioners seek a writ of certiorari to review a judg

ment of the United States Court of Appeals for the Second

Circuit entered on December 6,1967. That judgment unan

imously reversed a judgment of the United States District

Court for the Southern District of New York (M otley, J.),

vacated an injunction granted in that court and dismissed

the complaint.

2

Question Presented

Every school system must face the problem presented

by children who fail to make an adequate emotional ad

justment to the requirements of group education. Dis

ruptive behaviour by one child can halt the education of

an entire class. Victor Madera became a behaviour prob

lem to the point where his principal suspended him and

referred the question of Victor’s educational difficulty to

the District Superintendent. Victor and his parents were

requested to attend a guidance conference where, with the

aid of an advisor of their choice, they could discuss Vic

tor ’s problems with school officials and plan the next phase

of his education. The Board of Education does not con

sider the conference to be adversary in nature and, hence,

does not include attorneys among those invited to attend.

Social workers, psychologists or religious counsellors would

be welcomed to assist the student and his parents in the

conference. The object of the conference is to find an

answer to the student’s behavioral problem and provide

an educational environment where he can progress, more

effectively.

As a result of the conference the following decisions

may be reached: (1) the student may be reinstated in the

same school, (2) he may be transferred to another school

of the same type, (3) with his parents’ consent, he may

be transferred to a special school for socially maladjusted

children, (4) the student may be referred to the Bureau of

Child Guidance for psychiatric or psychological assistance

or to some other social agency for study and recommenda

tion, or (5) where truancy is in question, the matter may

be referred to the Bureau of Attendance for court action.

The parents of Victor Madera asked to be represented

by an attorney when they were requested to attend a con

ference with school officials concerning their son. In ac

cord with the policy of the Board of Education that the

3

conference should not be adversary in form or substance,

the request was denied.

Thus the question is posed: Do students and parents

have a constitutional right to be represented by counsel

at a guidance conference?

Facts

When this proceeding was commenced in the United

States District Court for the Southern District of New

York, petitioner Victor Madera was a 14-year-old student

in the seventh grade in Junior High School No. 22, Dis

trict No. 1 of the New York City public school system.

Victor had experienced serious behavioral difficulties in

school over a period of more than a year (R94-98).*

Ultimately, Victor’s principal decided that suspension

was warranted. The principal of a school is authorized

to suspend a pupil for a period of not more than five days

during which time he reports the child’s status to the Dis

trict Superintendent, his superior. If the child is not re

stored to regular classes within the five-day period, it is

the obligation of the District Superintendent to schedule

a Guidance Conference for the purpose of considering the

status of the child and making a determination as to the

appropriate educational assignment deemed best in the

light of the personal needs and abilities of the student

(R70-81).

In this case, pursuant to the regular practice, the par

ents were notified to attend a conference in the District

Superintendent’s office. They sought legal counsel, and

petitioners’ present counsel, the legal division of Mobiliza

tion For Youth, asked to appear on behalf of Mr. and Mrs.

Madera and their son. This request was denied in accord-

* Unless otherwise stated all numbers in parentheses refer to

pages in the Record filed with the United States Court of Appeals

for the Second Circuit.

4

anee with the provisions of Circular No. 16, dated April

18, 1966, which sets forth the procedure to be followed by

District School Superintendents in conducting guidance

conferences for suspended students (R70-80). Plaintiffs

then sought and obtained an injunction from the District

Court staying the guidance conference until the question

of their right to counsel could be determined.*

Counsel are precluded from attending guidance confer

ences for policy reasons set forth in Circular No. 16 as

follows:

“ Inasmuch as this is a guidance conference for the

purpose of providing an opportunity for parents,

teachers, counselors, supervisors, et al. to plan edu

cationally for the benefit of the child, attorneys seek

ing to represent the parent or the child may not par

ticipate.” (App. c of Petition, 74a)

The participation of the parents, however, is most de

sirable. The Circular states, “ Every effort should be

made to secure the parent’s attendance” {Id. at 75a). In

addition, the parents may be accompanied and assisted by

persons of their choosing including social workers, friends,

translators, etc., so long as those persons are not attorneys.

As a result of the conference the district superintendent

may reinstate the student in his same school, transfer him

to another school, refer him for placement in a school for

socially maladjusted children, refer him to the Bureau of

Child Guidance or other suitable agency for study and

recommendations, including medical suspension, home in

struction, exemption or, where truancy is a problem, re

fer him to the Bureau of Attendance for court action

(R79).

* Because of the injunction and the subsequent appeal, in order

to make sure that Victor Madera’s education was continued, he was

first put on home instruction and later transferred to another school

o f the same type as the one in which he was originally enrolled.

5

The Bureau of Child Guidance is the clinical arm of the

school board and is brought into use when professional

psychological or psychiatric assistance in diagnosis ap

pears helpful (R230-251).

The Bureau of Attendance acts in cases of truancy to

see that children and parents comply with the compulsory

attendance provisions of the Education Law (R251-257,

281-285).

It should be noted that district superintendents do not

have power to exempt a child from attending school; this

is reserved to the Superintendent of Schools and is rarely

used (R79, 81, 224).

The purpose of the guidance conference was set forth in

the affidavit of Bernard E. Donovan, Superintendent of

Schools, as follows:

“ The sole purpose of the conference is to study the

facts and circumstances surrounding the temporary

suspension of this student by his school principal, and

to place the child in a more productive educational

situation. At these conferences the assistant super

intendent interviews the child, his parents and school

personnel to learn the cause of the child’s behavior.

The conference is conducted in an atmosphere of un

derstanding and cooperation, in a joint effort involv

ing the parent, the school, guidance personnel and

community and religious agencies. There is never any

element of the punitive, but rather an emphasis on

finding a solution to the problem.

After a full and careful study and discussion a plan

is formulated to deal more adequately with the prob

lems presented by the child. Every effort is bent

towards the maintenance of a guidance approach. The

emphasis is on returning the child as rapidly as pos

sible to an educational setting calculated to be most

useful to him.” (R89-90)

6

No one within the entire structure of the Board of

Education has the power to deprive a child of his freedom

by confinement or commitment to an institution (R90, 242,

245, 247, 249, 250, 300, 322). Such matters are left to the

courts where the right of counsel is not questioned.

The Decisions Below

The essence of the District Court’s decision was ex

pressed as follows (41a-42a):

“ As a result of a review of the testimony, exhibits

and records produced by the District Superintendent,

this court finds that a ‘ Guidance Conference’ can

ultimately result in loss of personal liberty to a child

or in a suspension which is the functional equivalent

of his expulsion from the public schools or in a with

drawal of his right to attend the public schools.

This court also finds that as a result of a ‘ Guidance

Conference’, adult plaintiffs may be in jeopardy of

being proceeded against in a child neglect proceeding-

in the Family Court.

For the foregoing reasons, this court concludes that

the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment

to the Federal Constitution is applicable to a District

Superintendent’s Guidance Conference. More specifi

cally, this court concludes that enforcement by defend

ants of the ‘ no attorneys provision’ of Circular No.

16 deprives plaintiffs of their right to a hearing in

a state initiated proceeding which puts in jeopardy the

minor plaintiff’s liberty and right to attend the public

schools.”

In reversing the District Court the Circuit Court stated

(23a-24a):

“ The conference is not a judicial or even a quasi

judicial hearing. Neither the child nor his parents

7

are being accused. In saying that the provision

against the presence of an attorney for the pupil in a

District Superintendent’s Guidance Conference ‘ re

sults in depriving plaintiffs of their constitutionally

protected right to a hearing’ (267 F. Supp. at 373), the

trial court misconceives the function of the conference

and the role which the participants therein play with

respect to the education and the welfare of the child.

Law and order in the classroom should be the respon

sibility of our respective educational systems. The

courts should not usurp this function and t e n dis

ciplinary problems, involving suspensions, into crim

inal adversary proceedings—which they definitely are

not. The rules, regulations, procedures and practices

disclosed on this record evince a high regard for the

best interest and welfare of the child. The courts

would do well to recognize this.”

[N ote : In their appeal to the Circuit Court the respond

ents raised issues relating to the conduct of the trial and

rulings of the District Court as follows:

1. The District Court refused to permit counsel for de

fendant to inspect Court ’s Exhibit 21, a student’s suspense

file, for purposes of cross-examining a witness who had

described the exhibit at length in response to questions by

the Court (E274-275).

2. After the trial was over, the District Court, on its

own motion, added 23 new exhibits (also suspense files)

to the record without affording defendants an opportunity

to object to their introduction or to examine witnesses

concerning them (K47).

3. On the last day of trial, at the close of plaintiffs’

case, the District Court granted plaintiffs’ motion to

convert the suit into a class action. The class was never

8

adequately defined nor was there any notice given to any

member of the class however defined (E317, 319).

In light of the decision by the Circuit Court it was un

necessary for these matters to be ruled upon. However,

should this Court grant certiorari in this case, respondents

wish to preserve their rights to present all issues raised

on their appeal to the Circuit Court.]

POINT I

The nature of the guidance conference is informal

and not adversary. Legal counsel under these circum

stances is not required.

Petitioners stress the problems facing the urban poor

community and the effective assistance provided by or

ganizations such as Mobilization for Youth. They conclude

however that the unique skills of an attorney become nec

essary in a non-adversary meeting—a guidance confer

ence-even though the same organization could and in fact

does have social workers who are welcome to attend. Their

argument assumes that the interests of the school system

and the children in it are adverse. They disregard one of

the basic postulates of public school education— that teach

ers, counsellors, students and parents are mutually inter

dependent and should work cooperatively toward the goals

of education for all children. There is nothing in the

training of attorneys that makes them uniquely qualified

to assist in this process.

There are about 28,000 children in Victor Madera’s

school district. Of these, about 150 were suspended pending

appropriate action pursuant to the district superinten

dent’s guidance conference in the past two years. Some

of these students moved away, were unable for medical

reasons to resume their education or passed the age for

compulsory education and did not wish to resume. For

9

the great majority, however, the suspension was a tempo

rary interruption but not a termination of their education.

The loss of education, of course, for even one student

is regrettable. Unfortunately, however, there are a few

students that do not adjust to sehool environment, even

with extensive professional help. The percentage of

students for whom a guidance conference becomes neces

sary is small. The percentage of those who do not return

to a class as a result of action taken at a guidance con

ference is extremely small compared to the student body

as a whole.

Respondents do not suggest, however, that the answers

to the questions raised here can be found in the statistics

of pupil suspensions. Rather it is the nature of the educa

tional process and the proper relation between the schools

and the pupils that must be considered in the search for

a solution. These factors are in areas of policy where

precedent is not conclusive. If incarceration were truly

the question, as suggested by the district court below (41a),

the answer would be simpler. The district superintendent,

however, has no power to confine the child—this power is

reserved to the courts. Nor does the district superinten

dent have power to adjudicate any charges against the

parents. This too is reserved for the courts.

The professional competence needed to deal wisely and

fairly with suspended students is found in various dis

ciplines including education, guidance counselling, social

work, psychology and psychiatry. The implications of

this suit are that the members of the Board of Education’s

staff, professionally trained in these areas, are in reality

opposed in interest to the students they are attempting

to instruct or assist. On this assumption petitioners claim

a lawyer is essential at the guidance conference to defend

the suspended child. This approach will not help either

the child or the school.

10

The exclusion of lawyers is based on both practical and

policy considerations growing out of the need for deci

sions to be made by people properly trained and authorized

to make them and the belief that educational values will

suffer in an adversary proceeding.

While this case tends to focus solely on the individual

child on suspension, the needs of the student body as a

whole should not be ignored. A disturbed, disruptive child

needs help, but those in classes with him, including his

teachers, also have rights, and these include the right to

go about their work without excessive disturbances ox-

threats to their safety. This does not mean that respond

ents claim the right to ignore the needs of difficult chil

dren. The record here shows the varied and extensive

facilities and professional services set up solely to assist

them.

Under the present system if the educators fail and reach

an arbitrary or unwarranted decision, the student is not

without relief. There can be appeals to the Commissioner

of Education or a review by an Article 78 proceeding in

the Supreme Court of New York—both with the right of

counsel. In this way errors can be corrected, when a right

to relief is shown, without taking over the internal opera

tions of the schools.

Due pi-oeess requires no more than the right of counsel

where appropriate. There is no showing that counsel at

a guidance conference is required.

POINT II

The exclusion of attorneys from participation in a

guidance conference does not violate the requirements

of due process of law.

A. Guidance conference procedure.

The day a student is suspended by the principal a letter

is sent to his parents notifying them of the suspension and

11

advising them that a guidance conference will be held soon

thereafter (R168). A copy of the principal’s letter is also

sent to the Assistant Superintendent, who then sends a

letter to the parents notifying them of the date of the con

ference and asking them to be present. (See Appendix C,

68a-77a.) At the conference, as District Superintendent

Rakow testified:

“ No decision is made until the parent and child have

participated.” (R228)

Not only are great efforts made to have the parents ap

pear, but they may bring with them social workers famil

iar with the situation and a translator if necessary. The

Board also will supply a translator if advised that the

parents do not speak English. The conference, in short, is

an attempt by qualified educators and guidance counsellors,

working together with a child, his parents and interested

outside social workers, to find the best educational answer

for a student with a behavioral problem.

The Court of Appeals correctly distinguished between

judicial due process required at formal proceedings and

the non-judicial due process required in an informal pro

ceeding such as a guidance conference.

B. The requirements of due process.

The essentials of due process required in a criminal or

civil judicial proceeding are well established and include

at least the following: (1) proper notice, (2) an impartial

hearing, (3) the right to confront and cross-examine ad

verse witnesses, (4) the right to summon witnesses and

offer evidence, (5) the privilege against self incrimination,

and (6) the right to be represented by counsel. This is

especially so where the proceedings may terminate in in

carceration. In Re Gault, 387 U. S. 1 (1967); Kent v.

United States, 383 U. S. 541 (1966). The question is

1 2

whether such requirements must he included in an in

formal guidance conference where the purpose of the con

ference is to determine how best to meet the educational

needs of the pupil.

It is axiomatic that “ the requirements of due process

frequently vary with the proceeding involved . . . ”

Hannah v. Larche, 363 U. S. 420, 440 (1960), and “ what

is due process of law must be determined by circum

stances.” (Reaves v. Ainsworth, 219 U. S. 296, 304

[1911].)

There is a clear distinction between a judicial hearing

and an informal proceeding. “ A judicial inquiry investi

gates, declares and enforces liabilities as they stand on

present or past facts and under laws supposed already to

exist. That is its purpose and end.” (Prentiss v. Atlantic

Coast Line, 211 U. S. 210, 226 [1908].) Where, however,

the occasion calls for a proceeding less formal than a judi

cial inquiry, it should “ be so fitted in its range to the

needs of the occasion.” (Escoe v. Zerbst, 295 U. S. 490,

493 [1935].)

As this Court declared in Cafeteria and Restaurant

Workers Union v. McElroy, 367 U. S. 886, 894-895 (1961):

“ The Fifth Amendment does not require a trial-type

hearing in every conceivable ease of government im

pairment of private interest. * * * The very nature of

due process negates any concept of inflexible proce

dures applicable to every imaginable situation, [cita

tions omitted] ‘ “ [D]ue process” , unlike some legal

rules is not a technical conception with fixed content

unrelated to time, place and circumstances.’ It is

‘ compounded of history, reason, the past course of

decisions * # Joint Anti-Fascist Refugee Com

mittee v. McGrath, 341 U. S. 123, 162-163 (concurring

opinion). ”

13

C. There is no due process requirement for counsel at an

informal proceeding such as a suspension guidance con

ference.

Informal proceedings on matters of importance under

many conditions comply with the requirements of “ due

process” without representation by counsel.

The need for counsel varies with the nature of the pro

ceeding. In re Groban, 352 U. S. 330 (1957).

Where due process does require counsel it is because

“ the benefit of counsel . . . [is] essential to the substance

of the hearing.” Palho v. Connecticut, 302 U. S. 319, 327

(1937). The nature of the proceeding must determine

whether “ under the circumstances the necessity of coun

sel . . . [is] vital and imperative . . . ” Powell v. Ala

bama, 287 U. S. 45, 71 (1932). The Court here must look

to the substance of the proceeding to determine if the

student “ requires the guiding hand of counsel at every

step in the proceeding . . . ” Powell v. Alabama, supra,

287 U. S. at p. 69.

Is there a need for the attorney’s skills at the guidance

conference! There is no adversary. No attorney is pres

ent for the Board of Education. There is no prosecutor,

no judge, no jury and there are no complex rules of

procedure. Cf. Powell v. Alabama, supra. There are

no witnesses to be examined under oath. Formal rules

of evidence are not applied. None of these, however,

are essential to a concept of fundamental fairness under

the circumstances. To hold that the right of represen

tation by counsel is essential must eventually involve the

federal courts in a continuing and expanding supervision

of the guidance conference to determine, at each juncture,

whether, and which specifics of the Fifth and Sixth

Amendments are also essential.

If the professional conclusion is that the student should

be transferred to a parental school or to an institution

14

either for reason of physical or mental health or other rea

sons, the transfer may only be accomplished with the con

sent of the parents or by court order.*

No school official has this authority (Education Law

§ 3214). At this stage the parent may refuse such consent

in which event the child may not be transferred without

a judicial proceeding in the Family Court (Family Court

Act § 758). The right to representation by counsel is guar

anteed at that proceeding {id., §741), and the Court may

consider no evidence that is not “ competent, material and

relevant . . . ” (id., §744). In addition, as pointed out in

the Circuit Court decision (8a), it is clear that statements

made by the student or his parents at the guidance con

ference could not be introduced into evidence in any sub

sequent court proceedings. Cf. Garrity v. New Jersey, 385

IT. S. 493 (1967); Spevack v. Klein, 385 U. S. 511 (1967);

Miranda v. Arizona, 384 IT. S. 436 (1966); Escobedo v.

Illinois, 378 U. S. 478 (1964).

Thus, it appears that neither actual need nor due process

requires representation by counsel at the guidance con

ference. Lawyers are usually not trained as social workers,

educators, guidance counselors or psychologists. I f the

guidance conference should be turned into an adversary

proceeding, a lawyer should attend, perhaps for both

‘ ‘ sides, ’ ’ and hearing officers should be appointed to preside

and make the necessary rulings. Respondents believe this

approach is both unnecessary and unwise when viewed

from the point of view of the student, his parents or the.

school system.

D. Review proceedings are available to set aside the results

of a guidance conference.

Sections 310 and 311 of the New York Education Law

provide for a review on appeal to the Commissioner of

* O f course, prior to determining whether to consent or not

the parent may seek the advice of counsel.

15

Education in the case of any child or parent aggrieved by

the actions of any school authority including cases where a

child is suspended.

Pursuant to Section 310 the Commissioner of Education

has heard a number of cases involving the suspension of

students from school. Matter of SJieffel, 73 N. Y. St. Dept.

Rep. 104; Matter of Yonkes, 78 N. Y. St, Dept. Rep. 66;

Application of Olson, 40 Misc 2d 246, 242 N.Y.S. 2d 1002,

1003 (Sup. Ct., Nassau Co., 1963). At hearings dealing with

suspension of a student from class which may involve dis

puted issues of fact, the Commissioner of Education would

be required to conduct a judicial hearing “ according to

procedure which satisfied the rudiments of due process

of law . . . ” O’Brien v. Commissioner of Education, 4

N Y 2d 140, 146, 149 N. E. 2d 705 (1958) (concurring

opinion of Judge Van Voorhis). Thus, at that hearing

the student and his parents have the right to be repre

sented by counsel. Prior to or during the hearing the

Commissioner could stay the suspension or other action of

the school authorities (Education Law §311 [2]).*

Following the hearing he may “ make all orders . . . which

may, in his judgment be proper or necessary to give effect

to his decision” (Education Law §311 [4]).

The fact that a formal hearing with counsel is afforded

by the Commissioner and not at the guidance conference

does not violate due process.

Where, as here, the guidance conference gives the

student notice and a full opportunity to be heard in an

informal non-judicial setting and where there is a statutory

system for a petition or appeal to the Commissioner of

Education with all the safeguards of a judicial proceeding,

* While rightfully concerned that some students remained sus

pended for lengthy periods o f time, the petitioners and the District

Court fail to recognize that by petition or appeal to the Com

missioner o f Education the student may obtain a stay of the sus

pension pending the Commissioner’s determination.

16

representation by counsel should not be required at the

conference. The presence of an attorney could in fact “ so

far encumber the . . . proceeding as to make it unworkable

or unwieldy” (In re Grobcm, supra, at p. 334), and ob

struct the very aim of the guidance conference which is

to provide for the continuing education of the student.

As an alternative to an appeal to the Commissioner

of Education, a person aggrieved by acts of the Board of

Education may have a prompt review in the New York

State Supreme Court in an Article 78 proceeding (New

York Civil Practice Law and Rules, Section 7801-7806).

An Article 78 proceeding may be, and frequently is, com

menced by service of an order to show cause and a petition.

The court, of course, may include a stay of administrative

action pending determination of the matter by the court.

This procedure was followed in a suspense ease very

similar to this. Cosme v. Board of Education, 50 Misc 2d

344, 270 N.Y.S. 2d 231 (1966), affirmed without opinion, 27

A D 2d 905 (1st Dept. 1967). The lower court in Cosme

held that legal counsel was not required at a guidance

conference and stated (270 N.Y.S. 2d at p. 232):

“ These hearings are simple interviews or confer

ences which include school officials and the child’s

parents. Further, they are purely administrative in

nature, and are never punitive. The parents are

fully apprised of all of the facts and are furnished

with copies of all information in respondent’s pos

session.”

By constitutional standards of due process there is no

right to an attorney at the conference. By simpler stand

ards of policy there is no need for an attorney at the

conference. The school system of New York City has

many problems— some of them severe—but it does not fol

low that the solutions will come by extending the right

17

of counsel into areas of educational planning regarding the

best method of dealing with and providing an education for

a child with a behavioral problem. School officials can be

held to account for any unlawful decisions they may make

or unlawful practices they may adopt, but the day to day

operations of the schools should not be conducted as quasi

judicial proceedings. The work of the schools must con

tinue. Individual rights must be protected. The present

system affords a constitutional and practical balance of

the interests of both. Thus there is no need for a further

review of this ease. The Court of Appeals for the Second

Circuit carefully considered each of petitioners’ conten

tions and held that the present practice does not deprive

students or their parents of due process of law. Peti

tioners have failed to show any error in the analysis of

the Circuit Court which would warrant granting a writ

of certiorari.

CONCLUSION

The petition for a writ of certiorari should be denied.

April 5, 1968.

Respectfully submitted,

J. Lee Rankin,

•Corporation Counsel of

the City of New York,

Attorney for Respondents.

Stanley B uchsbatjm,

J ohn J. L oflin,

L uis M. Neco,

of Counsel.

(42166)