The Legislature of Louisiana v. Earl Benjamin Bush Jurisdictional Statement

Public Court Documents

February 8, 1961

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. The Legislature of Louisiana v. Earl Benjamin Bush Jurisdictional Statement, 1961. 14ac44bc-bb9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/71a0ae87-c69e-4435-b3ce-07ce20515b2e/the-legislature-of-louisiana-v-earl-benjamin-bush-jurisdictional-statement. Accessed January 23, 2026.

Copied!

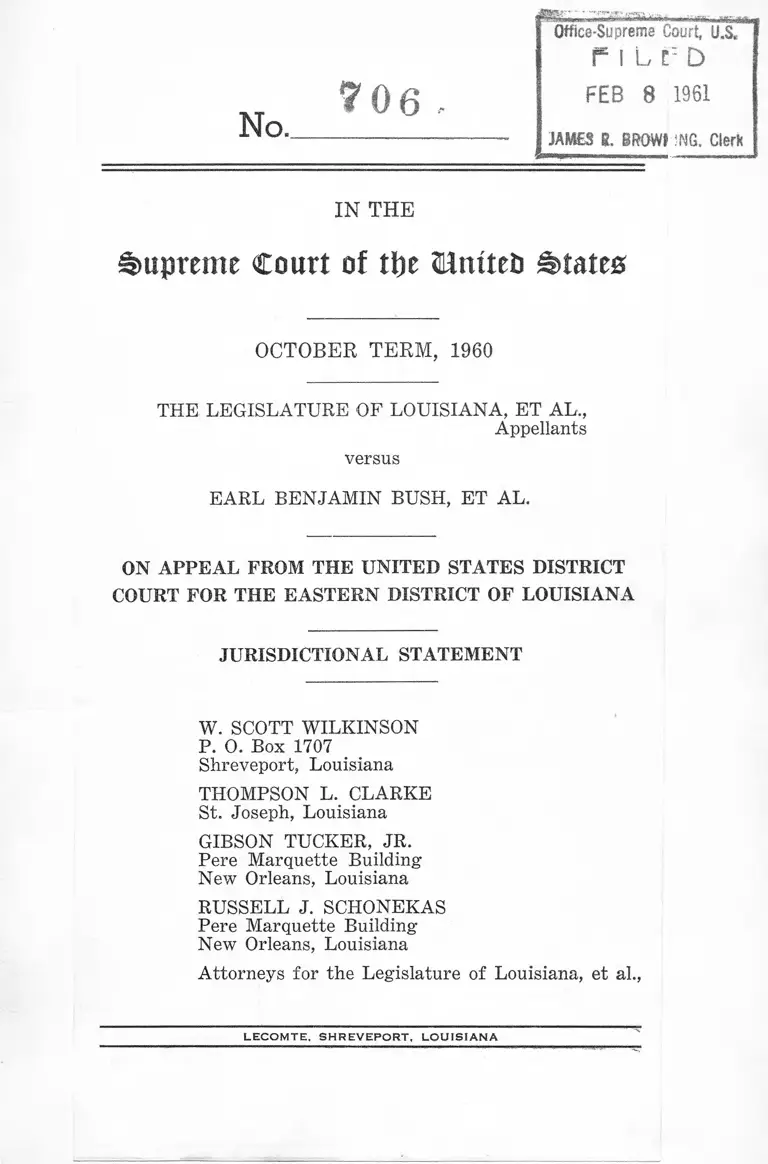

7 0 6No

Office-Supreme Court, U.S.

r i L c : D

FEB 8 1961

JAMS B. BROWf ING, Clerk

IN THE

Supreme Court of tbe MntteP States

OCTOBER TERM, 1960

THE LEGISLATURE OF LOUISIANA, ET AL.,

Appellants

versus

EARL BENJAMIN BUSH, ET AL.

ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT

COURT FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA

JURISDICTIONAL STATEMENT

W. SCOTT WILKINSON

P. 0 . Box 1707

Shreveport, Louisiana

THOMPSON L. CLARKE

St. Joseph, Louisiana

GIBSON TUCKER, JR.

Pere Marquette Building

New Orleans, Louisiana

RUSSELL J. SCHONEKAS

Pere Marquette Building

New Orleans, Louisiana

Attorneys for the Legislature of Louisiana, et al.,

L E C O M T E , S H R E V E P O R T , L O U I S I A N A

SUBJECT INDEX

Opinions B elow ....................

Jurisdiction

Questions Presented ........................

Statutes Involved

Statement ........................

The Questions Are Substantial .........................

Appendix A ................

Temporary Injunction Issued Nov. 30, I960,

Opinion of District Court issued

Nov. 30, 1960 ..............................

Temporary Injunction issued Dec. 21, I960

Appendix B ................................

Act 2, Second E. S. of 1960 ............... .

HCR # 2 Second E. S. of 1960......................

HCR #23 Second E. S. of 1960 ..............

HCR # 28 Second E. S. of 1960..................... .

Appendix C ..................................

Ex Parte Order Designating the

United States as Amicus Curiae

AUTHORITIES CITED

Cases

Arizona v. Californa,

283 US 423, 425, 75 L. Ed. 1154............................. 13

Barenblath v. U. S.,

360 US 109, 132, 3 L. Ed. 2d 1115........................ 13

Brush v. C.I.R., 300 US 352, 81 L. Ed. 691................ 12

C B & Q Ry. v. Otoe County,

16 Wall 667, 21 L. Ed. 375 ..................................... 18

City of Denver v. Denver Tramway Corp.,

23 F. 2d 287, Cert. Den. 278 US 616, 73 L ed 539.. 18

Colorado v. Symes, 286 US 510, 76 L. Ed. 1253............ 12

England v. La. State Board, 263 F. 2d 261 ................ 16

Fischler v. McCarthy,

117 F. Supp. 643, a ff’d 218 F. 2d 164................. . 16

Gas & Electric Sec. Co. v. Manhattan & Queens

Corp., 266 F. 625 ................................... .................. 16

Hans v. Louisiana, 134 US 1, 33 L. Ed. 842.............. 17

Higginbotham v. Baton Rouge,

306 US 535, 83 L. Ed. 968 ..................................... 15

Hodges v. U.S., 203 US 1, 51 L. Ed. 6 5 ........................ 19

Keim v. U.S., 306 US 535, 83 L. Ed. 968 .................... 15

Larson v. Domestic & Foreign Corp.,

337 US 682, 93 L. Ed. 1628

ii

17

m

McCabe v. AT & SF Ry.,

235 US 151, 59 L. Ed. 1 6 9 ..................................... 19

Mississippi v. Johnson,

71 US (4 Wall) 475, 18 L. Ed. 437 ............... 16

Missouri v. Adriano, 138 US 496, 34 L. Ed. 1012. 16

Missouri ex rel Gaines v. Canada,

305 US 337, 83 L. Ed. 208 .................................... 19

Mitchell v. U.S., 313 US 80, 85 L. Ed. 1201................. 19

Moffatt Tunnel Imp. Dist. v. D & S.L. Ry. Co.,

45 F. 2d 715 - Cert. den. 283 US 837, 75 L.

Ed. 1448 ................................. .... ................................. 18

New Orleans Waterworks v. New Orleans,

164 US 471, 41 L. Ed. 5 1 8 ..................................... 16

Palmetto Fire Ins. Co. v. Conn.,

272 US 295, 71 L. Ed. 243 ..................................... 3

Sanchez v. U.S., 216 US 167, 54 L. Ed. 432................ 15

St. John v. Wisconsin Employment Bd.,

340 US 411, 95 L. Ed. 386 ..................................... 3

Screws v. U.S., 375 US 109, 88 L. Ed. 1506................ 12

Snowden v. Hughes, 321 US 1, 88 L. Ed. 497.............. 19

Taylor v. Beckham,

178 US 570, 573, 44 L. Ed. 1198, 1199 ................ 16

Tway Coal Co. v. Glenn, 12 F. Supp. 570, 587............ 18

Wall v. Close, 203 La. 345, 14 So. 2d 19........................ 18

White v. Hart, 13 Wall, 646, 20 L. Ed. 685................ 12

United States Code

28 USC 1253 ....................................................................... 3

State Laws

Louisiana Constitution, Art. 9, Sec. 3 ......................... 14

Louisiana Constitution, Art. 12, Sec. 1 ........................ 14

Louisiana Constitution, Art. 12, Sec. 10 ...................... 14

Text Books

American Jurisprudence, Vol. 2, p. 679, 682 ............ 18

Corpus Juris Sec., Vol. 67, page 120, 121. 15

Corpus Juris Sec., Vol. 67, page 725 ............................ 16

Corpus Juris Sec., Vol. 81, page 1145.......................... 18

iv

IN THE

No,

Supreme Court of ttje MnttctJ states

OCTOBER TERM, 1960

THE LEGISLATURE OF LOUISIANA, ET AL,,

Appellants

versus

EARL BENJAMIN BUSH, ET AL,

ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT

COURT FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA

. JURISDICTIONAL STATEMENT

Appellants, the Legislature of Louisiana, its Mem

bers and Committees, appeal from two judgments of the

United States District Court for the Eastern District of

Louisiana, entered on November 30 and December 21,

1960, declaring unconstitutional certain statutes enacted

by the Legislature of Louisiana, and enjoining the Legis

lature, its members and committees and the chief executive

and other executives of the State of Louisiana from carry-

/

2

ing out any of the provisions of said statutes. Appellants

submit this statement to show that the Supreme Court

of the United States has jurisdiction of this appeal and

that a substantial question is presented.

OPINIONS BELOW

The opinion of the District Court for the Eastern

District of Louisiana, issued on November 30, 1960, and

the temporary injunction issued pursuant thereto are un

reported. No written opinion was issued in connection

with the judgment and the temporary injunction issued

on December 21, 1960. Copies of the opinion and the

temporary injunctions complained of, are attached hereto

as Appendix A.

Other opinions rendered before appellants were

made parties hereto are reported in: 138 ,F Supp 336,

A ff ’d 242 F 2d 156, Cert den 354 U. S. 121; 163 F. Supp.

701, a ff’d 268 F. 2d 78; 187 F. Supp. 42.

J U R I S D I C T I O N

The Bush case was originally brought in the year

1952 by certain negro plaintiffs on behalf of their minor

children seeking admittance for them to public schools

in the Parish of Orleans set aside for white children, and

was brought under provisions of the 14th Amendment of

the Constitution of the United States. In 1956 judgment

was rendered ordering the integration of the Orleans

Parish public schools. Thereafter, by supplemental com

plaint, plaintiffs sought to enjoin certain statutes enacted

3

by the Legislature of Louisiana in 1960 and to have them

declared unconstitutional in violation of the 14th Amend

ment. The Williams case was filed in August, 1960,

for the purpose of annulling or suspending the order

issued by the court on May 16, 1960 for the integration

of the public schools of Orleans Parish, Louisiana, and

in the alternative for a preliminary injunction restrain

ing the enforcement of the same acts of the State Legis

lature, and declaring the same unconstitutional. Notice

of appeal from the judgment of the District Court which

was entered on November 30, 1960 was filed in that court

on December 28, 1960. Notice of appeal of the judgment

of said Court entered on December 21, 1960, was filed

in that court on January 18, 1961.

The jurisdiction of the Supreme Court to review

these decisions by direct appeal is conferred by Title 28,

U.S. Code, Section 1253. The jurisdiction of the Supreme

Court to review these judgments on direct appeal is sus

tained by the following cases:

Palmetto Fire Insurance Company v. Conn,

47 S. Ct. 88, 272 US 295, 71 L. Ed. 243;

St. John v. Wisconsin Employment Relations

Bd., 71 S. Ct. 375, 340 US 411, 95 L. Ed. 386.

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

The following questions are presented by this ap

peal:

1. Whether or not Acts No. 10 to 14 and 17 to 27,

inclusive and House Concurrent Resolutions 10, 17,

18, 19 and 23 of the Thirtieth Extraordinary Ses-

4

sion, or 1st Extra Session, of the Louisiana Legis

lature of 1960, are constitutional.

2. Whether or not Act No. 2, and House Con

current Resolutions No. 2, 23 and 28 of the Thirty-

first Extraordinary Session, or 2nd Extra Session,

of the Louisiana Legislature, are constitutional.

3. Whether or not a federal district court has any

right, power or jurisdiction to enjoin the Legis

lature of Louisiana its members and committees,

the Governor, Lt. Governor, Treasurer and other

high officials and executives, and the courts of the

state from carrying out the provisions of state

statutes enacted for the maintenance of the safety,

public order, morals, education and general wel

fare of the people, which statutes by their terms

and provisions violate no provision or limitation of

the Constitution of the United States.

4. Whether or not a federal district court has any

right, power or jurisdiction to enjoin a state legis

lature from repealing, modifying or superseding

statutes enacted by it pursuant to its powers under

the State Constitution and powers reserved to the

state under the 10th Amendment to the United

States Constitution.

5. Whether or not the United States has any right,

as amicus curiae, to seek and obtain restraining

orders and injunctions in a proceeding by citizens

of a state against the legislative, executive and

judicial officers thereof for the alleged vindication

of their personal or civil rights, in the absence of

any intereference or threat of violence to any public

authority or agency or any official, agent or repre

sentative of the United States or to any property

or function of the federal government.

5

6. Whether or not these consolidated actions are

suits against the state without its consent, by citi

zens thereof, in violation of the 11th Amendment to

the United States Constitution in view of the fact

that plaintiffs seek herein to permanently enjoin

the legislative, executive, and judicial branches of

the state government from giving any effect to or

carrying out the provisions of state statutes re

pealing or modifying existing laws, or enacting

new statutes relating to subjects admittedly within

the police powers of the state, and by their terms

violative of no provision of the federal constitution.

7. Whether or not a federal court can issue compul

sory orders and mandatory or prohibitory injunc

tions to maintain in office former officials of a

school board whose offices have been abolished, va

cated, or superseded, and whose powers and func

tions have been divested and withdrawn by state

statutes enacted within the scope of the police power

of the state, and for such purpose can the federal

court order the state to supply state funds for such

usurpers and intruders in office?

8. Whether or not a federal court can deny to a

state legislature its authority, power and duty

under the State Constitution to make full provision

for the education of the youth of the state.

STATUTES INVOLVED

Louisiana Acts 10 to 14 inclusive and Acts 17 to 27

inclusive, and House Concurrent Resolutions No.

10, 17,18, 19 and 23 of the Thirtieth Extraordinary

Session, or 1st Extraordinary Session of the Lou

isiana Legislature of 1960. These acts are set

forth in full in Appendix D to the Brief of the

6

Orleans Parish School Board, Appellant herein, and

are made part hereof by reference thereto.

Act No. 2 and House Concurrent Resolutions No.

2, 23, and 28 of the Thirty-first Extraordinary

Session, or 2nd Extraordinary Session of the Lou

isiana Legislature of 1960. (Appendix B)

The 10th, 11th and 14th Amendments of the Con

stitution of the United States.

S T A T E M E N T

Plaintiff in the Bush Case brought suit against

the Orleans Parish School Board in the year 1952 under

the “ separate but equal” interpretation of the 14th Amend

ment and sought admittance for their children into public

schools reserved for white children in the City of New

Orleans. The case lay dormant until 1956.

On February 15, 1956, the United States District

Court for the Eastern Disctrict of Louisiana, ordered the

Orleans Parish School Board to begin desegregation of the

public schools in New Orleans with all deliberate speed.(,)

When no action was taken by the Board under that order,

the Court ordered the Board to file a desegregation plan

by May 16, 1960. On May 16, 1960, the Board filed a

pleading in the record stating that because of various

Louisiana state laws requiring segregation of the races

in the public schools, it was unable to file a plan. Where

upon, on the same day, the Court filed its own plan re-

( 1 ) 138 F. Supp. 366, aff’d 242 F. 2d 156 Cert. Den. 354 US

921.

7

quiring desegregation of the Orleans Parish schools be

ginning with the first grade in September 1960.

On July 25,1960, the Attorney General, in the name

of the State of Louisiana, filed a suit in the Civil District

Court for the Parish of Orleans against the Orleans Parish

School Board praying for an injunction restraining the

Board from desegregating the public schools of New

Orleans. The basis for this injunction was the allegation

that under Section IV of Action 496 of 1960, LSA-R.S.

17:347-4, only the Louisiana Legislature has the right to

integrate the public schools. In due course the injunction

was issued as prayed for on July 29, 1960.

On August 16, 1960, on motion of the plaintiffs

in the Bush case, the District Court made the Governor

of Louisiana and her Attorney General additional parties

defendant and set the motion for temporary injunction

for rehearing August 26, 1960. On August 17, 1960, Wil

liams et al v. Davis, Governor of Louisiana et al. was

filed. Since in the Williams case the plaintiffs also

asked for a temporary injunction against the Governor

of Louisiana and her Attorney General, in addition to

other state officials, a state judge, and the Orleans Parish

School Board, the Court consolidated the cases for hearing.

On the hearing of these issues the Court declared some

seven acts of the Legislature as unconstitutional, includ

ing some that were not put at issue. The Court also issued

an injunction against the Governor enjoining him from

carrying out the provisions of such laws, against the

Attorney General from further prosecution of the action

8

in the state court, and against the Treasurer of the State

of Louisiana prohibiting the latter from withholding school

books, supplies and funds from the public schools of Orleans

Parish. <2)

On August 10th, the District Judge extended the

execution date for the plan of desegregation to Monday,

November 14, 1960. In the meantime, the Legislature

of Louisiana met, in extra session, and passed the acts

and resolutions that are the subject of this appeal. Where

upon the plaintiffs in the Bush case and in the Williams

case filed supplemental complaints naming as additional

parties the following state officials: The Adjutant Gen

eral, Director of Public Safety, State Superintendent of

Education, the State Board of Education, the Judge of

the Civil District Court o f the Parish of Orleans and a

Committee of the Legislature of Louisiana to which the

Legislature had assigned all of the powers and duties

which had been withdrawn from the Orleans Parish School

Board pursuant to Act Number 18 of the First Extra

ordinary Session of 1960. A cross claim and third party

complaint was also filed by the Orleans Parish School

Board whereby the Legislature of the State of Louisiana

and the individual members thereof together with the Lt.

Governor of the State and the Speaker of the House of

Representatives were also made parties defendant.

On November 18, 1960, a three-judge court was

convened for the purpose of considering the issues raised

by the supplemental complaints of the plaintiffs and the

( 2 ) 187 F. Supp. 42.

9

cross-complaint of the Orleans Parish School Board. On

November 30, the court rendered a written opinion which

is set forth in Appendix A of this brief wherein the Court

held that Acts 10 to 14, inclusive, Acts 16 to 27, inclusive

and House Concurrent Resolutions numbers 10, 17, 18,

19 and 23 of the First Extraordinary Session of the Lou

isiana Legislature of 1960 were unconstitutional. (Page 26)

Pursuant to this opinion, the court issued a temporary in

junction enjoining the Governor and other executives of

the State of Louisiana, the Legislature of Louisiana and

its committees, and all other defendants from in any way

carrying out or enforcing the provisions of these acts of

the Legislature. (App. A, p. 23)

On December 2, 1960, the Court entered an ex parte

order requesting the United States to appear in these pro

ceedings as amicus curiae to accord the court the benefit

of its views and recommendations with the right to sub

mit pleadings, evidence, arguments and briefs, and to

initiate such further proceedings as may be appropriate.

(App. C, p.70) The United States accordingly filed a pe

tition as amicus curiae in the Bush case praying for an in

junction against all defendants, including the Legislature

of Louisiana, its individual members and committees, from

enforcing or implementing the Acts of the First Extraordin

ary Session referred to above, and also from enforcing or

implementing in any way Act No. 2 passed at the Second

Extraordinary Session of the Legislature on December 3.

Plaintiffs in the Bush case also filed a petition for a pre

liminary injunction against all defendants from enforc

ing the provisions of the same Acts of the Legislature.

10

Thereafter the Orleans Parish School Board filed

another cross claim and third-party complaint on Decem

ber 16 praying for an injunction against all defendants

from enforcing Act 2 and H.C.R. 2, 23 and 28 of the

Second Extraordinary Session of the Legislature, all of

which related to the supervision of the Legislature, and

a new school board created by it, over the operation of

the schools and the the handling of school funds for such

purpose. This cross claim made all banks having deposits

of state funds in New Orleans, and the City of New

Orleans parties defendant.

The foregoing issues were heard by a three-judge

court on December 16 and on December 21, 1960, the

Court issued a preliminary injunction against the de

fendants as prayed for and held the Acts of the Legis

lature unconstitutional. (App. A, p. 51)

None of the Acts of the Legislature, involved in this

appeal made any provision whatever for segregation in

the public schools, nor did they contain any reference

whatever to race or color. In fact, there was no single

clause or sentence that could be deemed to be in conflict

with the United States Constitution. These propositions

are admitted in the opinion of the district judges appealed

from, wherein they say:

“ As to these measures, then, we are admittedly in

an area peculiarly reserved for state action. But,

just as clearly we know that the sole object of the

legislation is to deprive colored citizens of a right

conferred upon them by the Constitution of the

United States.” (App. A, p. 47)

11

The Court had previously discussed Act 2 of the

first extra session of the Legislature which was an act

of interposition declaring the State to be supreme in

matters relating to the operation of its public schools,

and that it is therefore not bound by any decisions of the

federal courts to the contrary. The judges concluded that

this declaration of interposition set the tone and gave

substance to all the subsequent legislation, and that all

of the statutes complained of constituted a “package” of

segregation measures in conflict with the 14th Amendment.

This opinion was arrived at in the absence of any evi

dence of reason or logic that could explain just how, and

in what manner the so-called package would accomplish

a violation of the Constitution or would in any way affect

the orders of the court previously issued.

The Legislature did not submit its Act of Inter

position to the Court for adjudication and it has not

appealed from that portion of the lower court’s judgment

and decree which declared it unconstitutional. In fact

the act itself declares that the federal courts are not

competent to pass upon the question as to whether or not

they have unlawfully encroached upon the sovereignty of

the state in matters reserved to it exclusively by the Consti

tution. Nevertheless, none of the subsequent acts of the

Legislature refer to the Act of Interposition or are made

dependent on it in any way. Each statute deals with a

different subject and can stand on its own merits. Any

one or all of them can be carried out to the letter without

trespassing upon any rights of the parties to these suits

and without violating any part of the Constitution or any

12

act of Congress, or any decree of any federal court. There

is no allegation and no evidence that any attempt what

ever has been made by any of the defendants to carry out

even one of these statutory provisions in an unlawful or

unconstitutional manner.

THE QUESTIONS ARE SUBSTANTIAL

The questions here presented lie in that delicate

area of comity in state and federal relations so essential

to our national unity. So long as our present dual form

of government endures the states are in their sphere as

independent of the general government as that govern

ment, within its sphere is independent of the states. The

14th Amendment did not alter these basic relations.<3)

It is a matter of great importance to all the states

of the Union to know just how far the federal courts

can go in usurping powers that relate purely to local af

fairs, and to what extent they can void state laws that

relate to the creation of state subdivisions and the election

or appointment of local officials to manage and operate

state offices and agencies. The lower court in this case

has voided every act of the 1960 extra sessions of the

Louisiana legislature relating to the creation, operation,

maintenance or financing of the public schools, and has

done so— not on the ground that the acts themselves are

unlawful— but on the unfounded and unsupported sup-

( 3 ) Screws v. U.S., 325 US 109, 89 L. Ed. 1506; Brush v.

Comm. Int. Rev., 300 US 352, 81 L. Ed.: 691; Colorado

v. Symes, 286 US 510, 76 L. Ed. 1253; White v. Hart, 13

Wall 646, 20 L. Ed. 685.

13

position that these statutes will and can be used for un

constitutional objectives. If a court can do this in matters

of state police and public education, it can by the same

token usurp state powers in every other field of endeavor

on suspicion that an unlawful purpose may lurk behind

the statutes assailed. One of the acts annulled in this

case relates to the general powers and duties of the state

police force (Act 16, 1st E.S.) and in no way involves

public schools. Another Act deletes from existing law

all provisions requiring compulsory attendance at public

or private schools. (Act 27 1st E.S.) It would perhaps

be inappropriate in this jurisdictional statement to dis

cuss in detail the provisions and objectives of all acts

voided by the district judges. It is sufficient for the

present to rest on the lower courts opinion that all o f them

lie in an area reserved for exclusive state action.

This court has on many occasions ruled that the

courts cannot inquire into the motives which prompt the

members of the legislative branch of the government in the

enactment of laws.<4) Yet the lower court did inquire

into the purpose and motives of the legislature in an

nulling the statutes involved in this case.

Another substantial question of national importance

relates to the power and authority of a federal court to

enjoin a state legislature, its members, and committees in

carrying out the functions and duties committed to them

by the State Constitution.

( 4 ) Barenblath v. U.S., 360 US 109, 132, 3 L. Ed. 2d 1115

Arizona v. California, 283 US 423, 455, 75 L. Ed. 1154

and see cases cited in the above opinions.

14

Article 12, Section 1 of the Louisiana Constitution

of 1921, provides in part, as follows:

“ The Legislature shall have full authority to make

provisions for the education of the school children

of this state and/or for an educational system which

shall include all public schools and all institutions

of learning operated by State agencies.”

Article 12, Section 10 of the Constitution vests in

the Legislature the power to create parish school boards.

The Article provides, in part, that:

“ The Legislature shall provide for the creation and

election of parish school boards * * *”

Article 9, Section 3 of the Constitution reads in

part:

“ For any reasonable cause, whether sufficient for

impeachment or not, any officer, except the Gover

nor or acting Governor, on the address of two-thirds

of the members elected to each house of the Legisla

ture, shall thereby be removed.”

By virtue of the adoption of the Constitution of

the State, the people of Louisiana vested in the Legislature

the exclusive power over education and the exclusive power

over the several school boards of the parishes of Louisiana.

Acting pursuant to its Constitutional powers, the

Legislature of the State of Louisiana enacted Act No.

100 of 1922, (La. R. S. 17:121), relating to the nomina

tion, election, qualifications, compensation and vacancies

of the membership of the Orleans Parish School Board.

15

Again acting pursuant to its constitutional powers,

the Legislature passed Act No. 25 of the First Extra

ordinary Session of 1960 repealing Section 63 of Act No.

100 of 1922, (La. R. S. 17:121), whereby the school board

was created.

Further acting pursuant to its constitutional powers,

the Legislature enacted Act No. 17 of the First Extra

ordinary Session of 1960 which vested in the Legislature

the powers, duties and functions previously vested in

parish school boards in parishes having a population in

excess of 300,000 persons (which included the Parish

of Orleans).

After repealing the act which created the Orleans

Parish School Board the Legislature at its second extra

session passed Act No. 2 which created a new school board,

provided for the interim appointments of its members

and prescribed their duties and powers. The validity

and constitutionality of this act was upheld by the Supreme

Court of Louisiana on December 15 in the case of Singel-

man v. Jimmie H. Davis, et al. (Not yet reported).

Undoubtedly the Legislature had the power to create

the Orleans Parish School Board, and it had the right

to abolish it, as it has done by acts passed at these 1960

sessions. The power to abolish an office is as plenary as

the power to create it. <s) And the right to hold office

( 5 ) Higginbotham v. Baton Rouge, 306 US 535, 538, 83 L.

Ed. 968, 971; Sanchez v. U.S., 216 US 167, 54 L. Ed. 432

Keim v. U. S., 306 US 535, 538, 83 L. Ed. 968, 971; 67

CJS 120 - 121 and cases cited.

16

is not a vested right protected by the Constitution of the

United States. (6> The matter of control over the officers

of the state is therefore, exclusively within the province of

the state, free from interference by the United States.* (7)

But the effect of the various judgments of the district court

is to deny to the Legislature any control whatever over the

schools o f Orleans Parish. As a practical matter the

Legislature has been enjoined from passing any acts which

relate to the operation of the schools. The Court is with

out any jurisdiction or authority to enjoin the Legislature,

its individuals, and members, in this realm of power re

served to the state. In fact, the court cannot enjoin the

Legislature for any reason because the state could there

by be rendered impotent. If the members of the Legislature

refused to obey the injunction, could they be imprisoned

for contempt? Such imprisonment would, of course, de-,

stroy the legislative department of the state government.

As this Court stated in Mississippi v. Johnson, 1 US (4

Wall) 475, 18 L. Ed. 437:

“ The impropriety o f such interference will be clearly

seen upon consideration of its possible conse

quences.”

Not only does the judgment of the court below

take away from the Legislature control over the schools,

( 6 ) Taylor v. Beckham, 178 US 570, 573, 44 L. Ed. 1198, 1199

Missouri v. Adriano, 138 US 496, 34 L. Ed. 1012.

( 7 ) New Orleans Waterworks v. New Orleans, 164 US 471

41 L. Ed. 518; Mississippi v. Johnson, 71 US (4 Wall)

475, 18 L. Ed. 437; Gas & Electric Securities v. Man

hattan & Queens Corp., 266 F. 625; England v. La State

Board, 263 F. 2d 261; Fischler v. McCarthy, 117 F. Supp.

643, a ff’d. 218 F. 2d 164; 16 CJS 725 and cases cited.

17

but it also assumes control over the collection and alloca

tion of taxes and the use of state funds. H. C. R. No. 23,

(App. B, p. 62) and H. C. R. No. 28 passed at the Second

Extra Session (App. B, p. 67) and declared unconstitutional

by the court, seek to protect the bank accounts of the Legis

lature and to prevent withdrawal of funds except by the

state. H. C. R. No. 28 specifically recognizes the state’s

duty to pay its obligations, and there is no claim that it has

failed to pay debts of the New Orleans Schools, except for

the salaries of the defunct school board and its superinten

dent of schools who has refused to serve under the Legisla

ture’s direction. The judgment complained of, in effect,

mandatorily orders the City of New Orleans to turn over to

former members of the school board, whose offices have

been vacated, and whose powers have been withdrawn,

all tax monies collected for public schools. It orders the

banks and state depositories to honor check and drafts

signed by men who have been removed from office pur

suant to valid state laws. It orders the Treasurer of the

state to furnish school supplies and state funds to usurpers

and intruders in office, and in general the court has taken

over the financial affairs of the public schools and en

trusted their administration to discharged officials and

employees who have no legal right under state law to

act.

So the court has brought the status of this proceed

ing to a point where the State of Louisiana is the real de

fendant in view of this courts rulings in Hans v. Louisiana,

134 US 1, 33 L. Ed. 842, and Larson v. Domestic and

Foreign Corp,, 337 US 682, 3 L. Ed. 1628. This being

18

so the plaintiffs suits against the state, without its con

sent, should be dismissed as in violation of the 11th Amend

ment to the Constitution. With state judges, the Legis

lature, and all the high executive officers of Louisiana

as defendants, the state in its entirety has been put under

injunction by federal district court judges. What more

does it take to make the state the real party defendant?

The United States is, of course, not a real party plaintiff

in the suit, since it appears only as amicus curiae.

It is hornbook law that the power of the Legislature

over state funds is plenary, in respect of which it is vested

with a large discretion which cannot be controlled by the

courts. (8)

Still another question o f importance arises in con

nection with the action of the lower court in granting

an injunction on the petition of the United States against

the Legislature and its members. (App. A and C) There

is no law which would authorize the federal government

to intervene in a case of this kind, and it does not appear

herein as an intervenor. The government comes in merely

as amicus curiae. In that capacity it cannot assume the

function of a party. It can exercise no control over the

law suit and has no right to affirmative relief. (9)

( 8 ) C B & Q v . Otoe County, 16 Wall 667, 675, 21 L. Ed.

375, 381; Wall v. Close, 203 La. 345, 14 So. 2d 19; 81 CJS

1145 and cases cited.

( 9 ) City of Denver v. Denver Tramway Corp., 23 F. 2d

287, 295, Cert. Den. 278 US 616, 73 L. Ed. 539; Moffatt

Tunnel Imp. Dist. v. D & SI Ry. Co., 45 F. 2d 715, 722,

Cert. Den. 283 US 837, 75 L. Ed. 1448; R. C. Tway Coal

Co. v. Glenn, 12 F. Supp. 570, 587 2 Am. Jur. 679, 682.

19

The rights conferred by the 14th Amendment are

purely personal rights and their enforcement is a matter of

individual choice. (,°>

This Court has appropriately remarked:

“ It was not intended by the Fourteenth Amendment

and the Civil Rights Acts that all matters formerly

within the exclusive cognizance of the states should

become matters of national concern.” (n >

The United States therefore has no interest which

would permit it to secure an injunction against these

defendents. The only pretense offered by it to support

its claim is that it has “ the duty to represent the public

interest in the administration of justice and the preserva-

ion of the integrity of the processes of this (the District)

Court.”

(Petition Par. 9) There is no allegation, and none

could be made, that the defendants are threatening “ the

integrity of the processes of this Court” or that the district

court is unable to administer justice unless the might and

power of the United States is put behind it. This is but

another example of the constantly expanding tendency

of the federal government to interfere with local and per

sonal matters and to usurp the powers and functions of

the states and the courts. In this connection the court’s

(10) Mitchell v. United States, 313 US 80, 85 L. Ed. 1201;

Missouri ex rel Gaines v. Canada, 305 US 337, 83 L. Ed.

208; McCabe v. A T & S F Ry. Co., 235 US 151, 59 L. Ed.

169.

(11) Snowden v. Hughes, 321 US 1, 88 L. Ed. 497; See also

Hodges v. U. S., 203 US 1, 51 L. Ed. 65.

20

attention is called to the abortive effort to insert into the

Civil Rights Act of 1960 a provision that would permit

the United States Department of Justice to appear in

court and champion the claims of indivduals for alleged

violations of their civil rights. Congress refused to go

along with that proposition in the belief that the federal

government had no business in such a suit.

To permit the United States to invoke an injunction

against the Legislature and the highest officials of a

sovereign state is to sanction a practice which can only

strain the friendly relations that ought to exist between

the national sovereign and its constituent, but also

sovereign, states.

It is submitted that the district court was without

jurisdiction or power to enjoin the Legislature of Louisiana

or to interfere with the state’s control over its local affairs

and the exercise of its public power for the promoting and

maintenance of public order, education, health, safety,

morals and general welfare of its people. Furthermore,

it is submitted that the United States has no right to

appear as amicus curiae for the purpose of instituting

action for affirmative relief, and the suits of the Louisi

ana plaintiffs against the state, without its consent, should

be dismissed as in violation of the 11th Amendment.

21

The questions presented by this appeal are sub

stantial, and are of great public importance.

Respectfully submitted,

W. Scott Wilkinson

P. 0. Box 1707

Shreveport, Louisiana

Thompson L. Clarke

St. Joseph, Louisiana

Gibson Tucker, Jr.

Pere Marquette Building

New Orleans, Louisiana

Russell J. Schonekas

Pere Marquette Building

New Orleans, Louisiana

Attorneys for Defendants-Appellants,

The Legislature of Louisiana, et al.

22

C E R T I F I C A T E

I, W. Scott Wilkinson, one of the attorneys for

Defendants-Appellants herein, and a member of the

Supreme Court of the United States, do hereby certify

that on the 21st day of January, 1961, I served copies

of the foregoing Jurisdictional Statement on all parties in

this cause, by mailing a copy in a duly addressed envelope,

with postage paid to counsel of record for said parties.

This 21st day of January, 1961.

Of Counsel for Defendants-Appellants

23

A P P E N D I X “A”

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA

NEW ORLEANS DIVISION

CIVIL ACTION No. 10566

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

v.

STATE OF LOUISIANA, ET AL

CIVIL ACTION No. 3630

EARL BENJAMIN BUSH, ET AL

v.

ORLEANS PARISH SCHOOL BOARD, ET AL

CIVIL ACTION No. 10329

HARRY K. WILLIAMS, ET AL

v.

JIMMIE H. DAVIS, ET AL

TEMPORARY INJUNCTION

These cases came on for hearing on motions for

temporary injunction, restraining the enforcement of

certain acts and resolutions of the First Extraordinary

Session of the Louisiana Legislature for the year 1960.

It being the opinion of this Court that all Louisiana

statutes which would directly or indirectly require segre

gation of the races in the public schools, or deny them

public funds because they are desegregated, or interfere

with the operation of such schools, pursuant to the Orders

of this Court, by the Orleans Parish School Board, are

24

unconstitutional, in particular, Acts 2, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14,

16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26 and 27, and House

Concurrent Resolutions 10, 17, 18, 19, and 23;

IT IS ORDERED that the Honorable Jimmie H.

Davis, Governor of' Louisiana, the Honorable Clarence C.

Aycock, Lieutenant Governor of Louisiana, the Honorable

Jack P. F. Gremillion, Attorney General of the State of

Louisiana, the Legislature of the State of Louisiana, and

the individual members thereof, Shelby M. Jackson, State

Superintendent of Education, the Orleans Parish School

Board, Lloyd J. Rittner, Louis C. Riecke, Matthew R.

Sutherland, Theodore H. Sheppard and Emile A. Wagner,

Jr., the members thereof, James F. Redmond, Superin

tendent of Schools for the Orleans Parish School Board,

A. P. Tugwell, Treasurer of the State of Louisiana, Roy

R. Theriot, State Comptroller, The Louisiana State Board

of Education and the individual members thereof, Paul

B. Habans, Gerald Gallinghouse, David B. Gertler, Edward

F. LeBreton, Charles Diechmann, Ridgley C. Triche, P.

P. Branton, Welborn Jack, Vial Deloney, William Cleve

land, E. W. Gravolet, Maj. Gen. Raymond H. Fleming,

Adjutant General of Louisiana, Murphy J. Roden, Di

rector of Public Safety of the State of Louisiana, the

District Attorneys of all Judicial districts of Louisiana,

as a class, the Criminal Sheriffs of all parishes in Lou

isiana, as a class, the Mayors of all incorporated munici

palities of the State of Louisiana, as a class, the Chiefs

of Police of all incorporated municipalities of the State

of Louisiana, as a class, and all other persons who are

acting or may act in concert with them, be, and they are

25

hereby restrained, enjoined and prohibited from enforcing

or seeking to enforce by any means the provisions of

Acts 2, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23,

24, 25, 26 and 27, and House Concurrent Resolutions 10,

17, 18, 19 and 23 of the First Extraordinary Session of

the Louisiana Legislature for 1960, and from otherwise

interfering in any way with the operation of the public

schools for the Parish of Orleans by the Orleans Parish

School Board, pursuant to the Orders of this Court.

IT IS FURTHER ORDERED that copies of this

temporary injunction shall be served forthwith upon each

of the defendants named herein.

IT IS FURTHER ORDERED that a copy of this

temporary injunction shall be served forthwith on The

Louisiana Sovereignty Commission, through its chairman.

An injunction bond in the sum of $100.00 shall

be filed herein.

S / Richard T. Rives

UNITED STATES CIRCUIT JUDGE

(Signed) HERBERT W. CHRISTENBERRY

UNITED STATES DISTRICT JUDGE

(Signed) J. SKELLY WRIGHT

UNITED STATES DISTRICT JUDGE

Issued November 30, 1960,

at New Orleans, Louisiana

26

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

EASTERN DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA

NEW ORLEANS DIVISION

NO. 3630

CIVIL ACTION

EARL BENJAMIN BUSH, et al,

Plaintiffs,

versus

ORLEANS PARISH SCHOOL BOARD, et al,

Defendants.

NO. 10329

CIVIL ACTION

HARRY K. WILLIAMS, et al,

Plaintiffs,

versus

JIMMIE H. DAVIS, Governor of the State

of Louisiana, et al,

Defendants.

NO. 10566

CIVIL ACTION

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Plaintiffs,

versus

STATE OF LOUISIANA, et al,

Defendants.

RIVES, Circuit Judge, and CHRISTENBERRY and

WRIGHT, District Judges:

Called into extraordinary session for November 4,

1960, just ten days before the day fixed by this court for

27

the partial desegregation of the New Orleans public

schools,(,) the Louisiana Legislature promptly enacted 27

( 1 ) The Orleans Parish school desegregation controversy

has been in the federal courts for eight years. Since

the decision in Brown v. Board o f Education, 347 U.S.

483, in 1954, it has been clear that under the Constitution

of the United States segregation in the public schools

of Louisiana cannot lawfully continue, and that all state

laws in conflict with the Brown holding are null and

void. Repeatedly, however, the state legislature has en

acted legislation designed to circumvent the law of the

land and to perpetuate segregation in the schools of

Louisiana.

In 1954, the state adopted a constitutional amendment

and two segregation statutes. The amendment and Act

555 purported to re-establish the existing state law re

quiring segregated schools. Act 556 provided for as

signment of pupils by the school superintendent. On

February 15, 1956, this court issued a decree enjoining

the School Board, “ its agents, its servants, its employees,

their successors in office, and those in concert with

them who shall receive notice of this order” from re

quiring and permitting segregation in the New Orleans

schools. Bush v. Orleans Parish School Board, 138 F.

Supp. 336, 337, 342, aff’d, 242 F. 2d 156, cert, denied,

354 U. S. 921.

Not only was there no compliance with that order, but

immediately there after the legislature produced a new

package of laws, in particular Act 319 (1956) which pur

ported to “ freeze” the existing racial status of public

schools in Orleans Parish and to reserve to the legisla

ture the power of racial reclassification of schools. On

July 1, 1956, this court refused to accept the School

Board’s contention that Act 319 had relieved the Board

of its responsibility to obey the desegregation order.

In the words of the court, “Any legal artifice, however

cleverly contrived, which would circumvent this ruling

[of the Supreme Court, in Brown v. Board of Education,

supra] and others predicated on it, is unconstitutional

on its face. Such an artifice is the statute in suit, “Bush

v. Orleans Parish School Board, 163 F. Supp. 701, a ff’d

268 F. 2d 78. See also, Lane v. Wilson, 307 U. S. 268.

Nevertheless, the legislature continued to contrive cir-

cumventive artifices. In 1958 a third group of segre

gation laws was enacted, including Act 256, which em-

28

measures(2) designed to halt, or at least forestall, the

implementation of the Orleans Parish School Board’s an

nounced proposal to admit five Negro girls of first grade

age to formerly all-white schools. The first of these, Act

2 of the First Extraordinary Session of 1960,<3) is the

so-called “ interposition” statute by which Louisiana de

clares that it will not recognize the Supreme Court’s de

powered the Governor to close any school under court

order to desegregate, as well as any other school in the

system. In the first court test of this law it was struck

down as unconstitutional by this court on August 27,

1960. Bush v. Orleans Parish School Board, 187 F.

Supp. 42.

On July 15, 1959, the court ordered the New Orleans

School Board to present a plan for desegregation, Bush

v. Orleans Parish School Board, No. 3630, but there

was no compliance. Therefore, on May 16, 1960, the

court itself formulated a plan and ordered desegrega

tion to begin with the first grade level in the fall of

1960.

For the fourth time, in its 1960 session, the legislature

produced a packet of segregation measures, this time

to prevent compliance with the order of May 16, 1960.

Four of these 1960 measures — Acts 333, 495, 496 and

542 — and the three earlier acts referred to above—Act

555 of 1954, Act 319 of 1956, and Act 256 of 1958—were

promptly declared unconstitutional by a three-judge

court on August 27, 1960, in the combined cases of Bush

v. Orleans Parish School Board and Williams v. Davis,

and their enforcement by “the Honorable Jimmie H.

Davis, Governor of the State of Louisiana, and all those

persons acting in concert with him, or at his direction,

including the defendant, James F. Redmond,” was en

joined. Bush v. Orleans Parish School Board, 187 F.

Supp. 42, 45. At the same time, the efective date of the

desegregation arder was postponed to November 14,

1960.

( 2 ) An analysis of the 27 Acts, minus Act 2, and House Con

current Resolutions 10, 17, 18, 19 and 23 forms Appendix

B to this opinion.

( 3 ) The full text of Act 2 forms Appendix A to this opinion.

29

cision in Brown v. Board of Education, supra, or the

orders of this court issued pursuant to the mandate of

that case. Insofar as it provides criminal penalties against

federal judges and United States marshals who render

or carry out such decisions, the Government, by separate

suit consolidated here for hearing, seeks an injunction

against the Act. The next seven Acts, Nos. 3 through 9,

merely repeal statutes earlier ruled on by this court and

enjoined as unconstitutional.<4)

The remaining seventeen Acts, numbered 10 through

27, are here assailed on constitutional grounds and a

temporary injunction against their enforcement is prayed

for by the Plaintiffs, parents of white school children, in

the Williams case. Among these are measures purporting

to abolish the Orleans Parish School Board and transfer

its function to the Legislature. On November 10, 1960,

restraining orders were directed to the appropriate state

officers enjoining them from enforcing the provisions of

all but one of the statutes pending hearing before this

court. Nevertheless, apparently still considering itself

the administrator of the New Orleans public schools, the

Louisiana Legislature has continued to act in that capacity,

issuing its directives by means of concurrent resolutions.

House Concurrent Resolutions Nos. 17, 18, and 19. On

November 13th, when the enforcement of these resolutions

was also restrained on motion of the School Board, the

Legislature retaliated by addressing all but one member

of the Board out of office. House concurrent Resolution

No. 23. This action by the Legislature also was the sub-

( 4 ) See Note 1.

30

ject of an immediate temporary restraining order. As

cross-claimant in the Bush case, the original school case

filed by parents of Negro children, the School Board now

asks for a temporary injunction against these most recent

measures. Finally, the court has before it a motion by

the School Board to vacate or stay its order fixing Novem

ber 14, 1960, as the date for the partial desegregation of

the local schools.

Jurisdiction

In view of the fact that one of the actions involved

has been pending for more than eight years and that

several judgments have already been rendered in the

proceeding both here and on appeal, (S> it would seem

somewhat late in the day to raise jurisdictional issues.

But, in view of the eleborate arguments pressed upon us

we have re-examined the matter.

Pretermitting the question of jurisdiction under 28

U.S.C. Sec. 1331, it is, of course, plain that jurisdiction

of the claims in the Bush and Williams cases is vested by

the provisions of 28 U.S.C. Sec. 1343 (3) and of the suit

of the United States by 28 U.S.C. Sec. 1345, and that,

since in all three matters an injunction is sought against

the enforcement of state laws by officers of the state, a

court of three judges was properly convened under 28

U.S.C. Sec. 2281.

Insofar as it is denied that the measures under

attack work a “ deprivation . . . of any right . . . secured

( 5 ) See Note 1.

31

by the Constitution of the United States,” that is a question

addressed to the merits. For jurisdictional purposes it

suffices that a substantial claim of deprivation has been

made. Likewise, the “ interpretation” defense cannot affect

the initial jurisdiction of the court, for it must at least

take jurisdiction to determine whether the state act pur

porting to insulate Louisiana from the force of federal law

in the field of public education is constitutionally valid.

If the statute is not valid, obviously it can have no effect

on the court’s jurisdiction. The Eleventh Amendment

argument, made again here, has already been fully an

swered on a prior appeal in the Bush case. See 242 F.2d

156. Of course, the Eleventh Amendment has no appli

cation to the suit of the United States.

Finally, there is no merit in the claim of “ legislative

immunity” put forward on behalf of the committee of

the Legislature and its members who are sought to be

enjoined from enforcing the measures which grant them

control of the New Orleans public schools. The argument

is specious. There is no effort to restrain the Louisiana

Legislature as a whole, or any individual legislator, in

the performance of a legislative function. It is only in

sofar as the lawmakers purport to act as administrators

of the local schools that they, as well as all others con

cerned, are sought to be restrained from implementing

measures which are alleged to violate the Constitution.

Having found a statute unconstitutional, it is elementary

that a court has power to enjoin all those charged with

its execution. Normally, these are officers of the executive

branch, but when the legislature itself seeks to act as

32

executor of its own laws, then, quite obviously, it is no

longer legislating and is no more immune from process

than the administrative officials it supercedes. As Chief

Justice Marshall said in Marbury v. Madison, 5 U.S. (1

Cranch) 137, 170; “ It is not by the office of the person

to whom the writ is directed, but the nature of the thing

to be done, that the propriety or impropriety of issuing

(an injunction) is to be determined.”

Interposition

Except for an appropriation measure to provide

for the cost of the special sesson, the first statute enacted

by the Louisiana Legislature at this Extraordinary Ses

sion was the interposition act. That was appropriate

because it is this declaration which sets the tone and

gives substance to all the subsequent legislation. For the

most part, the measures that followed merely implement

the resolve announced in the interposition act to “ maintain

racially separate public school facilities . . . when such

facilities are in the best interest of their citizens,” not

withstanding “ the decisions of the Federal District Courts

in the State of Louisiana, prohibiting the maintenance

of separate schools for whites and negroes and ordering

said schools to be racially integrated,” which decisions,

being “ based solely and entirely on the pronouncements of

Brown vs. Topeka Board of Education,” are “ null, void

and of no effect as to the State of Louisiana.” Signifi

cantly, the Attorney General, appearing for the State and

most of its officers, rested his sole defense on this act.

Without question, the nub of the controversy is in the

33

declaration of interposition. If it succeeds, there is no

occasion to look further, for the state is then free to do

as it will in the field of public education. On the other

hand, should it fail, nothing can save the “ package” of

segregation measures to which it is tied.

Interposition is an amorphous concept based on the

proposition that the United States is a compact of states,

any one of which may interpose its sovereignty against

the enforcement within its borders of any decision of the

Supreme Court or act of Congress, irrespective of the fact

that the constitutionality of the act has been established

by decision of the Supreme Court, Once interposed, the

law or decision would then have to await approval by

constitutional amendment before enforcement within the

interposing state. In essence, the doctrine denies the con

stitutional obligation of the states to respect those decisions

of the Supreme Court with which they do not agree<6) 6

( 6 ) The short answer to interposition may be found in

Cooper v. Aaron, 353 U. S. 1, 17-18. In view of the ap

parent seriousness with which the State of Louisiana

makes the point, however, we will labor it.

In Cooper v. Aaron, the Supreme Court stated:

«***We should answer the premise of the actions of

the Governor and Legislature that they are not bound

by our holding in the Brown case. It is necessary

only to recall some basic constitutional propositions

which are settled doctrine.

“Article VI of the Constitution makes the Constitu

tion the ‘supreme Law of the Land.’ In 1803 Chief

Justice Marshall, speaking for a unanimous Court,

referring to the Constitution as ‘the fundamental

and paramount law of the nation’, declared in the

notable case of Marbury v. Madison, 1 Cranch 137,

177, that ‘it is emphatically the province and duty

of the judicial department to say what the law is.’

This decision declared the basic principle that the

34

The doctrine may have had some validity under the Articles

of Confederation. On their failure, however, “ in order

to form a more perfect union,” the people not the states,

of this country ordained and established the Constitution.

Martin v. Hunter, 14 U.S. (1 Wheat.) 304, 324. Thus the

keystone of the interposition thesis, that the United States

is a compact of states, was disavowed in the Preamble to

the Constitution.(7)

federal judiciary is supreme in the exposition of the

law of the Constitution, and that principle has ever

since been respected by this Court and the Country

as a permanent and indispensable feature of our con

stitutional system. It follows that the interpreta

tion of the Fourteenth Amendment enunciated by this

Court in the Brown case is the supreme law of the

land, and Art. VI of the Constitution makes it of

binding effect on the States ‘any Thing in the Con-

sitution or Laws of any State to the Contrary not

withstanding.’ Every state legislature and executive

and judicial officer is solemnly committed by oath

taken pursuant to Art. VI, cl. 3, ‘to support this

Constitution.’ ” Cooper v. Aaron, supra.

( 7 ) Of course, even he “compact theory” does not justify

interposition. Thus, Edward Livingston, Louisiana’s

noted lawgiver, through an adherent of that theory,

strongly denied the right of a state to nullify federal

law or the decisions of the federal courts. While re

presenting Louisiana in the United States Senate and

participating in its debates in January, 1830, he stated

his view “That, by the institution of this government, the

states have unequivocally surrendered every constitu

tional right of impeding or resisting the execution of

any decree or judgment of the Supreme Court, in any

case of law or equity between persons or on matters, of

whom or on which that court has jurisdiction, even if

Such a decree or judgment should, in the opinion of the

states, be u n c o n s t itu t io n a l“That the alleged right

of a state to put a veto on the execution of a law of the

United States, which such state may declare to be un

constitutional, attend (as, if it exist, it must be) with

the correlative obligation, on the part of the general

government, to refrain from executing it ; and the futher

35

Nevertheless, throughout the early history of this

country, the standard of interposition was raised when

ever a state strongly disapproved of some action of the

central government. Perhaps the most precise formula

tion of the doctrine can be found in the Virginia and

Kentucky interposition resolutions against the Alien and

Sedition Acts. Jefferson was the reluctant author of

the Kentucky resolution, while Madison wrote Virginia’s.

Jefferson was not proud of his work for he never admitted

authorship. And Madison, after publicly espousing the

cause of interposition for a short time, spent much of his

energy combating the doctrine and finally admitted its

bankruptcy in these words:

“ The jurisdiction claimed for the Federal Judiciary

is truly the only defensive armor of the Federal

Government, or rather for the Constitution and

laws of the United States. Strip i f of that armor,

and the door is wide open for nullification, anarchy

and convulsion, * * *” Letter, April 1, 1833, quoted

in 1 Warren, The Supreme Court in United States.

History (Revised Ed. 1926), 740.

While there have been many cases which treat of

segmented facets of the interposition doctrine, in only

alleged obligation, on the part of that government, to

submit the question to the states, by proposing amend

ments, are not given by the Constitution, nor do they

grow out of the reserved powers;” “That the intro

duction of this feature in our government would totally

change its nature, make it inefficient, invite to dis

sension, and end, at no distant period, in separation; and

that, if it had been proposed in the form of an explicit

provision in the Constitution, It would have been un

animously rejected, both in the Convention which fram

ed that instrument and in those which adopted it.”

Quoted in 4 Elliot’s Debates 519-520. (Emphasis Added).

36

one is the issue squarely presented. In United States v.

Peters, 9 U.S. (5 Cranch) 115, the legislature of Pennsyl

vania interposed the sovereignty of that state against

a decree of the United States District Court sitting in

Pennsylvania. After much litigation/8> Chief Justice

Marshall finally laid the doctrine to rest thusly:

“ If the legislatures of the several states may, at will,

annul the judgments of the courts of the United

States, and destroy the rights acquired under those

judgments, the Constitution itself becomes a solemn

mockery; and the nation is deprived of the means

of enforcing its laws by the instrumentality of its

own tribunals. So fatal a result must be deprecated

by all; and the people of Pennsylvania, not less than

the citizens of every other state, must feel a deep

interest in resisting principles so destructive of the

Union, and in averting consequences so fatal to

themselves.” United States v. Peters, supra, 136.

Interposition theorists concede the validity, under

the supremacy clause, of acts of Congress and decisions

of the Supreme Court except in the area reserved for the

states by the Tenth Amendment. But laws and decisions

in this reserved area, the argument runs, are by defini

tion unconstitutional, hence are not governed by the

supremacy clause and do not rightly command obedience.

This, of course, is Louisiana’s position with reference to

the Brown decision in the recent Act of Interposition.

Quite obviously, as an inferior court, we cannot overrule

( 8 ) For a detailed statement of the case, its background and

aftermath, see the address by Mr. Justice Douglas re

printed at 1 F.R.D. 185 and 9 Stan. L. Rev.3.

37

that decision. The issue before us is whether the Legis

lature (9) of Louisiana may do so.

Assuming always that the claim of interposition

is an appeal to legality, the inquiry is who, under the Con

stitution, has the final say on questions of constitution

ality, who delimits the Tenth Amendment. In theory, the

issue might have been resolved in several ways. But, as

a practical matter, under our federal system the only

solution short of anarchy was to assign the function to

one supreme court. That the final decision should rest

with the judiciary rather than the legislature was inherent

in the concept of constitutional government in which leg

islative acts are subordinate to the paramount organic

law, and, if only to avoid, “ a hydra in government from

which nothing but contradiction and confusion can pro

ceed,” final authority had to be centralized in a single

national court. The Federalist, Nos. 78, 80, 81, 82. As

Madison said before the adoption of the Constitution:

“ Some such tribunal is clearly essential to prevent an

appeal to the sword and a dissolution of the compact; and

that it ought to be established under the general rather

than under the local governments, or, to speak more

properly, that it could be safely established under the

( 9 ) It is interesting to note that even Calhoun, whose writ

ings, in addition to those of Madison, are now invoked

by Louisiana, did not pretend that the legislature of

the state had a right to interpose, but held that a popular

convention within the state was the proper medium for

asserting state sovereignty. See His “Fort Hill Letter”

of August 28, 1832, quoted in pertinent part in Miller

and Howell, “ Interposition, Nullification and the De

licate Division of Power in a Federal System,” 5 T. Pub.

L. 2, 31.

38

first alone, is a position not likely to be combated.” The

Federalist, No. 39.

And so, from the beginning, it was decided that

the Supreme Court of the United States must be the final

arbiter on questions of constitutionality. It is of course

the guardian of the Constitution against encroachments

by the national Congress. Marbury v. Madison, supra.

But more important to our discussion is the constitutional

role of the Court with regard to State acts. The original

Judiciary Act of 1789 confirmed the authority of the

Supreme Court to review the judgments of all state tri

bunals on constitutional questions. Act of Sept. 24, 1789,

Sec. 25; 1 Stat. 73, 85. See Martin v. Hunter, supra;

Worcester v. Georgia, 31 U. S. (6 Peters) 515; Cohens v.

Virginia, 19 U. S. (6 Wheat) 264; Ableman v. Booth, 62

U. S. (21 Row.) 506. Likewise from the first one of its

functions was to pass on the constitutionality of state laws.

Fletcher v. Peck, 10 U. S. (6 Cranch) 87; McCullough v.

Maryland, 17 U. S. (4 Wheat.) 316. And the duty of the

Court with regard to the acts of the state executive is no

different. Sterling v. Constantin, 287 U.S. 378; Cooper v.

Aaron, 358 U.S. 1. The fact is that the Constitution itself

established the Supreme Court of the United States as the

final tribunal for constitutional adjudication. By defini

tion, there can be no appeal from its decisions.

The initial conclusion is obvious enough. Plainly,

the states, whose proceedings are subject to revision by

the Supreme Court, can no more pretend to review that

Court’s decision on constitutional questions than an in

89

ferior can dispute the ruling of an appellate court. From

this alone “ it follows that the interpretation of the Four

teenth Amendment enunciated by (the Supreme) Court

in the Brown case is the supreme law of the land, and

(that) Art. VI of the Constitution makes it of binding

effect on the States ‘any Thing in the Constitution or

Laws of any State to the Contrary notwithstanding’.”

Cooper v. Aaron, supra, 18.

But this is not all. From the fact that the Supreme

Court of the United States rather than any state authority

is the ultimate judge of constitutionality, another conse

quence of equal importance results. It is that the juris

diction of the lower federal courts and the correctness of

their decisions on constitutional questions cannot be re

viewed by the state governments. Indeed, since the appeal

from their rulings lies the Supreme Court of the United

States, as the only authoritative Constitutional tribunal,

neither the executive nor the legislature, nor even the

courts of the state, have any competence in the matter.

It necessarily follows that, pending review by the Supreme

Court, the decisions of the subordinate federal courts on

constitutional questions have the authority of the supreme

law of the land and must be obeyed. Assuredly, this is

a great power, but a necessary one. See United States v.

Peters, supra, 135, 136.

Apprehensive of the validity of the proposition that

the Constitution is a compact of states, interposition as

serts that at least a ruling challenged by a state should

be suspended until the people can ratify it by constitutional

40

amendment. But this invocation of “ constitutional pro

cesses” is a patent subterfuge. Unlike open nullification,

it is defiance hiding under the cloak of apparent legitimacy.

The obvious flaw in the argument lies in the unfounded

insistence that 'pending a vote on the proposed amendment

the questioned decision must be voided. Even assuming

their good faith in proposing an amendment against them

selves, the interpositionists want too much. Without any

semplance of legality, they claim the right at least tem

porarily to annul the judgment of the highest court, and,

should they succeed in defeating the amendment proposed,

they presume to interpret that victory as voiding forever

the challenged decision. It requires no elaborate demon

stration to show that this is a preposterous preversion of

Article V of the Constitution. Certainly the Constitution

can be amended “ to overrule” the Supreme Court. But

there is nothing in Article Y that justifies the presump

tion that what has authoritatively been declared to be the

law ceases to be the law while the amendment is pending,

or that the non-ratification of an amendment alters the

Constitution on any decisions rendered under it .no)

(10) Madison also had occasion to comment on this modified

interposition: “ . . .We have seen the absurdity of such

a claim in its naked and suicidal form. Let us turn to

it as modified by South Carolina, into a right of every

State to resist within itself the execution of a Federal

law by it to be unconstitutional, and to demand a con

vention of the States to decide the question of Con

stitutionality; the annulment of the law to continue in

the meantime, and to be permanent unless three-fourths

of the States concur in overruling the annulment.

“Thus, during the temporary nullification of the law,

the results would be the same from (as?) those proceed

ing from an unqualified nullification, and the result

of the convention might be that seven out of twenty-

41

The conclusion is clear that interposition is not a

constitutional doctrine. If taken seriously, it is illegal

defiance of constitutional authority. Otherwise, “ it

amounts to no more than a protest, an escape valve

through which the legislature blows o ff steam to relieve

their tensions.” Shuttlesworth v. Birmingham Board of

Education, N.D. Ala., 162 F. Supp. 372, 381. However

solemn or spirited, interposition resolutions have no legal

efficacy. Such, in substance, is the official view of Vir

ginia, delivered by its present Governor while Attorney

General. And there is a general tacit agreement

among the other interposing states'*2> which is amply

four States might make the temporary results perm

anent. It follows, that any State which could obtain

the concurrence of six others might abrogate any law

of the United States, constructively, whatever, and give

to the Constitution any shape they please, in opposition

to the construction and will of the other seventeen,

each of the seventeen having an equal right and author

ity with each of the seven. Every feature in the Con

stitution might thus be successively changed; and after

a scene of unexampled confusion and distraction, what

had been unanimously agreed to as a whole, would not,

as a whole, be agreed to by a single party. The amount

of this modified right of nullnfication is, that a single

State may arrest the operation of a law of the United

States, and institute a process which is to terminate in

the ascendancy of a minority over a large majority in

a republican system, the characteristic rule of which

is, that the major will is the ruling will, . . Madison,

on nullification (1835-1836), in IV Letters and Other

Writings of James Madison (Congress ed. 1865), 409.

(11) See the Opinion of Attorney General Almond rendered

February 14, 1956, in 1 Race Rel. L. Rep. 462.

(12) Interposition declarations have beeti adopted in Alabama,

Act 42 of Spec. Sess. 1956; Georgia, H. Res. 185 of 1956;

Mississippi, Sen. Cone. Res. 125 of 1956; South Carolina,

Act of Feb. 14, 1956; Virginia, Sen. Joint Res. 3 of 1956;

Tennessee, H. Res. 1 and 9 of 1957; and Florida Sen.

42

reflected in their failure even to raise the argument in

the recent litigation, the outcome of which they so much

deplore. Indeed, Louisiana herself has had an “ interposi

tion” resolution on the books since 1956,(,3) and has never

brought it forth. The enactment of the resolution in statu

tory form does not change its substance. Act 2 of the

First Extraordinary Session of 1960 is not legislation in

the true sense. It neither requires nor denies. It is

mere statement of principles, a political polemic, which

provides the predicate for the second segregation package

of 1960, the legislation in suit. Its unconstitutional pre

mise strikes with nullity all that it would support.

The Other Legislation

Without the support of the Interposition Act, the

rest of the segregation “ package” falls of its own weight.

However ingeniously worded some of the statutes may

be, admittedly the sole object of every measure adopted at

the recent special session of the Louisiana Legislature is

to preserve a system of segregated public schools in defiance

of the mandate of the Supreme Court in Brown and the

orders of this court in Bush. What is more, these acts

were not independent attempts by individual legislators

to accomplish this end. The whole of the legislation, spon

sored by the same select committee, forms a single scheme,

all parts of which are carefully interrelated. The pro-

Conc. Res. 17-XX of Spec. Sess. 1956, and H. Cone. Res.

174 of 1957. For text of these acts and resolutions, see

1 Race Rel. L. Rep. 437, 438, 440, 443, 445, 948; 2 id. 228,

481, 707.

(13) H. Cone. Res. 10 of 1956. The text of the Resolution

is reproduced in 1 Race Rel. L. Rep. 753.

43

ponents of the “ package” were themselves insistent on

so labelling it, and expressly argued that the passage of

every measure proposed was essential to the success of the

plan. In view of this, the court might properly void the

entire bundle of new laws without detailed examination

of its content. For, as the Supreme Court said in Cooper v.

Aaron, supra, 17, “ the constitutional rights of children not

to be discriminated against in school admission on grounds

of race or color declared by this Court in the Brown case

can neither be nullified openly and directly by state legis

lators or state executive or judicial officers, nor nulli

fied indirectly by them through evasive schemes for segre

gation whether attempted ‘ingeniously or ingenuously/ ”

But we shall nevertheless give brief consideration to each

of the measures enacted.

Re-Enactment of Statutes Previously Declared

Unconstitutional

Five of the new statutes merely re-enact laws al

ready voided by this court on August 27, 1960. Bush v.

Orleans Parish School Board, 187 F.Supp. 42. Act 10 of

the recent session is, except for the most minor stylistic

changes, a verbatim copy of Act 541 of 1960(,4) which

required the Governor to close any school threatened with

“ disorder, riots or violence.” We said of that law that

“ its purpose speaks louder than its words.” The same

is true of the present statute. It can fare no better.

Likewise, Acts 11, 12, 13 and 14, all in effect school