Mulkey v. Reitman Amicus Curiae Brief

Public Court Documents

June 11, 1965

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Mulkey v. Reitman Amicus Curiae Brief, 1965. c1d713eb-be9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/71f75c75-4045-4d92-b8d7-3dc10842ac96/mulkey-v-reitman-amicus-curiae-brief. Accessed February 20, 2026.

Copied!

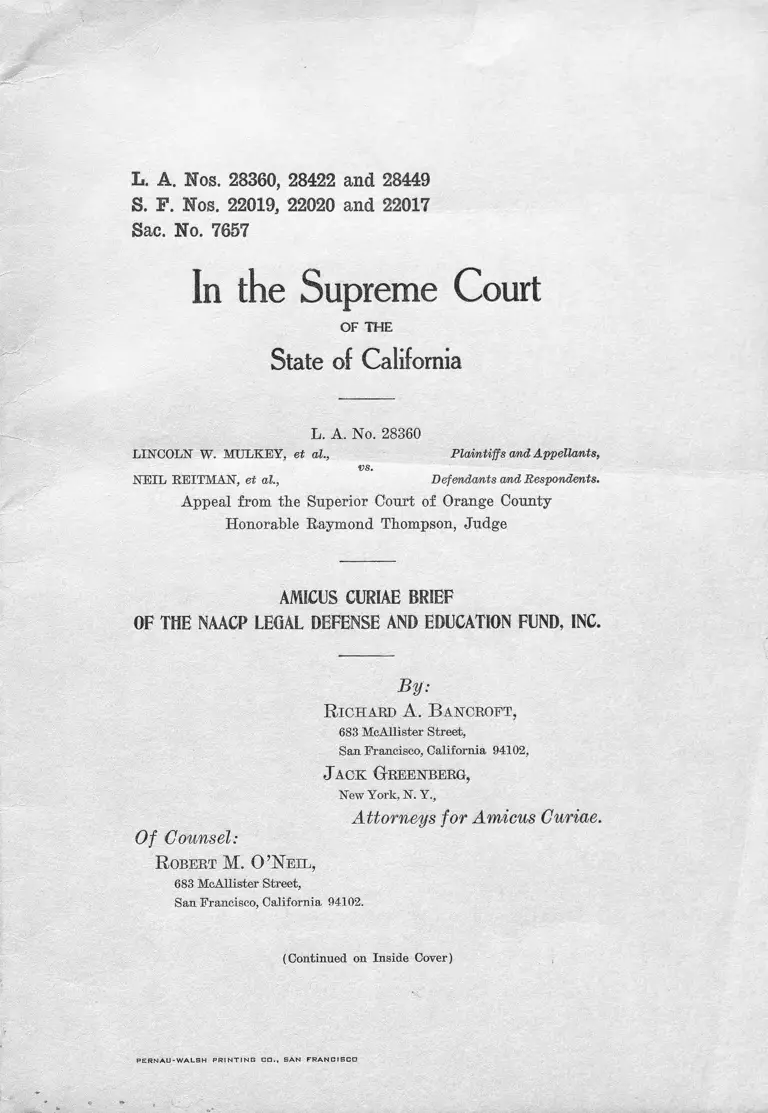

L. A . Nos. 28360, 28422 and 28449

S. F. Nos. 22019, 22020 and 22017

Sac. No. 7657

In the Supreme Court

OF THE

State of California

L. A. No. 28360

LINCOLN" W. MULKEY, et al., Plaintiffs and Appellants,

vs.

NEIL B.EITMAN, et al., Defendants and Respondents.

Appeal from the Superior Court of Orange County

Honorable Raymond Thompson, Judge

AMICUS CURIAE BRIEF

OF THE NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATION FUND, INC.

Of Counsel:

B y:

R ic h a r d A. B a n c r o f t ,

683 McAllister Street,

San Francisco, California 94102,

J a c k Gr e e n b e r g ,

New York, N. Y.,

Attorneys for Amicus Curiae.

R o bert M. O ’N e i l ,

683 McAllister Street,

San Francisco, California 94102.

(Continued on Inside Cover)

P E R N A U - W A L S H P R I N T I N G C D . , BA N F R A N C I S C O

L. A. No. 28422

WILFRED J. PRENDERGAST and CAROLA EVA PRENDERGAST, on

behalf of themselves and all persons similarly situated,

Cross-Defendants and Respondents,

vs.

CLARENCE SNYDER, Cross-ComplaAmmt and Appellant.

Appeal from the Superior Court of Los Angeles County

Honorable Martin Katz, Judge

L. A. No. 28449

THOMAS ROY PEYTON, M.D., Plaintiff and Appellant,

vs.

BARRINGTON PLAZA CORPORATION, Defendant and Respondent.

Appeal from the Superior Court of Los Angeles County

Honorable Martin Katz, Judge

Sac. No. 7657

CLIFTON HILL, Plaintiff and Appellant,

vs.

CRAWFORD MILLER, Defendant and Respondent.

Appeal from the Superior Court of Sacramento County

Honorable William Gallagher, Judge

S. F. No. 22019

DORIS R. THOMAS, Plaintiff and Appellant,

vs.

G. E. GOULIAS, et ad., Defendants and Respondents.

Appeal from the Municipal Court of the

City and. County of San Francisco

Honorable Robert J. Drewes, Judge ; Honorable Leland J.

Lazarus, Judge, and Honorable Lawrence S. Mana, Judge

S. F. No. 22020

JOYCE GROGAN, Plaintiff and Appellant,

vs.

ERICH MEYER, Defendant and Respondent.

Appeal from the Municipal Court of the

City and County of San Francisco

Honorable Robert J. Drewes, Judge; Honorable Leland J.

Lazarus, Judge, and Honorable Lawrence S. Mana, Judge

S. F. No. 22017

REDEVELOPMENT AGENCY OF THE CITY OF FRESNO, a public body,

corporate and politic, Petitioner,

vs.

KARL BUCKMAN, Chairman of the Redevelopment Agency of the City of

Fresno, Respondent.

Petition for Writ of Mandate

Subject Index

Page

Interest of amicus ......................................................................... 2

I. Article I, § 26 of the California Constitution violates

the Supremacy Clause of the United States Constitu

tion, because it obstructs vital federal programs for

California, and because it closes the doors of California

courts to the enforcement of various federal rights. . . . 3

A. Article I, § 26 cripples the federal program of

assisting construction of nondiscriminatory housing

and urban renewal projects in California communi

ties .................................................................................... 3

1. The federal policy of nondiscrimination in housing 3

2. Implementation of the federal p o licy ..................... 6

3. Conflict between state and federal la w ................ 7

B. Article I, § 26 conflicts with other federal policies

and interests ................................................................... 13

C. Article I, § 26 closes the doors of the California

courts to causes of action based upon the U. S. Con

stitution and acts of Congress ...................................... 15

Table of Authorities Cited

Oases Pages

Berman v. Parker, 348 U.S. 26 (1954) ................................. 4

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U.S. 60 (1917) .............................. 4

Claflin v. Houseman, 93 U.S. 130 (1876) ............................ 15

Parmer v. Philadelphia Elec. Co., 329 F.2d 3 (3d Cir.

1964) 18

First Iowa Hydro-Electric Coop. v. FPC, 328 U.S. 152

(1946) ......................................................................................... 12

FPC v. Oregon, 349 U.S. 435 (1955) ..................................... 12

Hurd v. Hodge, 334 U.S. 24 (1948) ............................ 4

In re Redevelopment Plan for Bunker Hill, 61 Cal. 2d 21

(1964) ...................................................................................... 17

Ivanhoe Irrigation District v. McCracken, 357 U.S. 275

(1958), on remand, 53 Cal. 2d 692 (1960).......................... 10

Kleiber v. City and County of San Francisco, 18 Cal. 2d

718 (1941) ............................................................ - ............... 17

McCarroll v. Los Angeles County District Council of Car

penters, 49 Cal. 2d 45 (1957) ................................................ 16

Miller v. Arkansas, 352 U.S. 187 (1956) .................................. 12

Ming v. Horgan, No. 97130, 3 Race Rel. L. Rep. 693 (Super.

Ct. June 23, 1958) ................................................................. 5,17

Napier v. Church, 132 Tenn. I l l , 177 S.W. 56 (1915)........ 17

Neiswonger v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co., 35 F.2d 761

(N.D. Ohio 1929) ................................................................... IS

Roosevelt Field v. Town of North Hempstead, 84 F. Supp.

456 (E.D. N.Y. 1949) ........................................................ 18

Second Employers’ Liability Cases, 223 U.S. 1 (1 9 1 1 ).... 15

Smith v. Holiday Inns of America, Inc., 336 F.2d 630 (6th

Cir. 1964) ................................................................................ 6,17

Sperry v. Florida Bar, 373 U.S. 379 (1963) ........................ 12

Testa v. Katt, 330 U.S. 386 (1947) ....................................... 16

West Virginia ex rel. Dyer v. Sims, 341 U.S. 22 (1 9 5 1 ).... 7

Woods v. Cloyd W. Miller Co., 333 U.S. 138 (1948).......... 14

Attorney General’s Opinions Pages

43 Ops. Cal. Atty. Gen 98A (1964) ....................................... 7

Constitutions

California Constitution:

Article I, Section 3 ............................................. 3

Article I, Section 2 6 ................................................... 3, 8, 10, 17

United States Constittuion:

Article VI ............................................................................. 3

Statutes

Civil Rights Act of 1964:

Title IV ................................................................................. 14

Section 405(a) ................................................................. 14

Section 605 ......................................................................... 8

Title VI ............................................................................... 8,9,10

23 U.S.C. § 120 (1958) .......................................................... 12

42 U.S.C. § 1441 (1958) ............................................................. 4

42 U.S.C. § 1982 (1958) ............................................................. 4,17

Texts

“ Civil Rights Under Federal Programs,” Civil Rights Com

mission, Jan. 1965, p. 13 ....................................... ............... 9

Clancy & Nemerovski, Some Legal Aspects of Proposition

Fourteen, 16 Hastings L. J. 3, 13 n. 47 (1964)................. 18

Executive Order on Equal Opportunity in Housing, No.

11063, 27 Fed. Reg. 11527 (1962) ....................................... 6

60 Ilarv. L. Rev. 966, 969 (1947) ........................................... 15

77 Harv. L. Rev. 285 (1963) ................................................... 18

Los Angeles Times, December 3, 1964, part II, p. 8 .......... 8

Sloane, One Year’s Experience: Current and Potential Im

pact of the Housing Order, 32 Geo. Wash. L. Rev. 457,

474 (1964) ........................... ....................................... ........... 6

Taylor, Destruction of Federal Reclamation Policy? The

Ivanhoe Case, 10 Stan. L. Rev. 76, 83-84, 111 (1957)........ 11

Table of A uthorities Cited iii

L. A. Nos. 28360, 28422 and 28449

S. F. Nos. 22019, 22020 and 22017

Sac. No. 7657

In the Supreme Court

OF THE

State of California

L. A. No, 28360

LINCOLN W. MULKEY, et al., Plaintiffs and Appellants,

vs.

NEIL REITMAN, et al., Defendants and Respondents.

Appeal from the Superior Court of Orange County

Honorable Raymond Thompson, Judge

L. A. No. 28422

WILFRED J. PRENDERGAST and CAROLA EVA PRENDERGAST, on

behalf of themselves and all persons similarly situated,

Cross-Defendants and Respondents,

vs.

CLARENCE SNYDER, Cross-Complainant and Appellant.

Appeal from the Superior Court of Los Angeles County

Honorable Martin Katz, Judge

L. A. No. 28449

THOMAS ROY PEYTON, M.D., Plaintiff and Appellant,

vs.

BARRINGTON PLAZA CORPORATION, Defendant and Respondent.

Appeal front the Superior Court of Los Angeles County

Honorable Martin Katz, Judge

Sac. No. 7657

CLIFTON HILL, Plaintiff and Appellant,

vs.

CRAWFORD MILLER, Defendant and Respondent.

Appeal front the Superior Court of Sacramento County

Honorable William Gallagher, Judge

2

S. F. No. 22019

DORIS R. THOMAS, Plaintiff and Appellant,

vs.

G. E. GOULIAS, et al., Defendants and Respondents.

Appeal from the Municipal Court of the

City and County of Sail Francisco

Honorable Robert J. Drewes, Judge; Honorable Leland J.

Lazarus, Judge, and Honorable Laivrence S. Mana, Judge

JOYCE GROGAN,

ERICH MEYER,

S. F. No. 22020

vs.

Plaintiff and Appellant,

Defendant wnd Respondent.

Appeal from the Municipal Court of the

City and County of San Francisco

Honorable Robert J. Drewes, Judge; Honorable Leland J.

Lazarus, Judge, and Honorable. Lawrence S. Mana, Judge

S. F. No. 22017

REDEVELOPMENT AGENCY OF THE CITY OF FRESNO, a public body,

corporate and politic, Petitioner,

vs.

KARL BUCKMAN, Chairman of the Redevelopment Agency of the City of

Fresno, Respondent.

Petition for Writ of Mandate

AMICUS CURIAE BRIEF

OF THE NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATION FUND, INC.

INTEREST OF AMICUS

The National Association for the Advancement of

Colored People Legal Defense and Education Eund

Inc., is an organization which is dedicated to the pro

tection of the legal rights of Negroes. This brief is

limited to the issue of the conflict between Proposition

3

14 and the Supremacy Clause of the United States

Constitution and is being filed because this issue has

not been fully developed in the briefs in this matter

presently before this Court.

I. ARTICLE I, § 26 OF THE CALIFORNIA CONSTITUTION VIO

LATES THE SUPREMACY CLAUSE OF THE UNITED STATES

CONSTITUTION, BECAUSE IT OBSTRUCTS VITAL FEDERAL

PROGRAMS FOR CALIFORNIA, AND BECAUSE IT CLOSES

THE DOORS OF CALIFORNIA COURTS TO THE ENFORCE

MENT OF VARIOUS FEDERAL RIGHTS.

The cornerstone of the Federal system is the su

premacy of federal law decreed by Article V I of the

Constitution of the United States. The California

Constitution, Art. I, § 3, recognizes the reciprocal ob

ligation which this clause imposes upon the States.

Article I, § 26 would challenge the supremacy of fed

eral law in three important respects: (1) by prevent

ing the implementation of comprehensive federal pro

grams in the areas of housing and urban renewal;

(2) by disabling the State and all state and local offi

cials from cooperating with the Federal Grovernment

in other important areas; and (3) by closing the doors

of the state courts to lawsuits based upon the Federal

Constitution and acts of Congress.

A. Article I, § 26 Cripples the Federal Program of Assisting

Construction of Nondiscriminatory Housing and Urban Re

newal Projects in California Communities.

1. The Federal Policy of Nondiscrimination in Housing.

Congress has twice declared a strong federal policy

of nondiscrimination in the sale or rental of housing.

4

Shortly after the Civil War Congress enacted as part

of the original civil rights legislation this provision:

“ All citizens of the United States shall have the same

right, in every State and Territory, as is enjoyed by

white citizens thereof to inherit, purchase, lease, sell,

hold, and convey real and personal property.” 42

U.S.C. § 1982 (1958). This provision has been seldom

before the courts. But in one of the restrictive cove

nant cases, the U.S. Supreme Court, found in this brief

statute a federal policy against any direct or indirect

governmental support of racial discrimination in pri

vate housing. Hurd v. Hodge, 334 U.S. 24, 34 (1948) ;

see also Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U.S. 60, 79 (1917).

The second and more recent source of nondiscrimi

nation is the extensive federal legislation designed to

assist the construction of housing. The present federal

housing aid program, o f which urban renewal is a

central part, derives from the Housing Act of 1949.

In that statute Congress declared it to be the national

purpose to realize as soon as possible the goal of “ a

decent home and a suitable living environment for every

American family . . . ” 42 U.S.C. § 1441 (1958). This

purpose, and the programs designed to implement it,

are in the judgment of Congress required by “ the

general welfare and security of the Nation and the

health and living standards of its people.” The United

States Supreme Court recognized over a decade ago

the critical importance of comprehensive shim clear

ance and urban renewal to the national health and

well-being. Berman v. Parker, 348 U.S. 26 (1954).

And since the adoption of the National Housing Act

5

great strides have been made toward the national goal

of decent housing for all Americans. California has

enjoyed at least a fair share of that progress; by No

vember, 1964 the Federal Government had supplied

about $250 million for urban renewal in California

communities.

Clearly these federal funds may not be used to fi

nance, directly or indirectly, racial discrimination on

the part of private beneficiaries. While there is no

express prohibition of discrimination in the terms of

the Housing Act such a prohibition is necessarily im

plied—else there would be serious doubt about the

constitutionality of the statute. Recognition o f this

principle was the basis of the landmark decision of the

Superior Court of Sacramento County in Ming v.

Morgan, No. 97130, 3 Race Rel. L. Rep. 693, 698-99

(Super. Ct. June 23, 1958). Judge Oakley concluded

that “ Congress must have intended the supplying of

housing for all citizens, not just Caucasians—and on an

equal, not a segregated basis.” Otherwise, the court

continued, “ the constitutional guaranties of equal pro

tection and non-discrimination would be accorded only

secondary importance and they would have to recede

from a good deal that has been laid down in recent

years as fundamental doctrine.” On this basis the

court held that a federally assisted subdeveloper

might not constitutionally practice racial discrimina

tion in the sale of private housing. This same prin

ciple has recently been recognized and applied by a

federal court of appeals, in holding that a private

motel built as part of a federally financed urban re

6

newal project could not discriminate against a Negro

who sought lodging there. Smith v. Holiday Inns of

America., Inc., 336 F.2d 630 (6th Cir. 1964) (the same

result would clearly be required today by the Civil

Rights Act of 1964, but the case arose before passage

of that Act).

2. Implementation of the Federal Policy.

It remained for the late President Kennedy to make

explicit what had always been implicit in the Housing

Act. The Executive Order on Equal Opportunity in

Housing, No. 11063, 27 Fed. Reg. 11527 (1962), sought

to guarantee that federal funds may not be used to

foster, directly or indirectly, racial discrimination in

the sale or rental of housing. The Order applied to all

funds to be appropriated for projects approved after

its effective date. Thus every participating local

agency was required to sign an agreement to provide

for nondiscrimination in its contracts with rede

velopers. See Sloane, One Year’s Experience: Cur

rent and Potential Impact of the Housing Order, 32

Oeo. Wash. L. Rev. 457, 474 (1964). As for projects

approved before the Order was issued, the Order called

upon federal agencies and officials “ to use their good

offices and to take other appropriate action permitted

by law . . . to promote the abandonment of discrimi

natory practices with respect to residential property

and related facilities heretofore provided with federal

financial assistance. . . .” (§ 102)

7

3, Conflict Between State and Federal Law.

In order to appreciate the severity of the conflict

between the new California Constitutional amendment

and the federal law, it, is necessary to consider, three

types, of renewal projects. With respect to projects

contracted for prior to issuance of the Executive Order,

California officials now seem powerless to cooperate

or assist with the “ good offices” and “ appropriate

action” of federal officials designed to end whatever

racial or other discrimination there may be in fed

erally assisted projects. Thus state law effectively pre

cludes the performance of a duty required by federal

law and based upon the United States Constitution.

With respect to contracts entered between the effec

tive date of the Executive Order and November 3,

1964, the nondiscrimination pledge has been incorpo

rated into many agreements, apparently without diffi

culty. See letter from Robert C. Weaver, Administra

tor of the Housing and Home Finance Agency, to

Rep. Augustus F. Hawkins, March 1964, in 43 Ops.

Cal. Atty. Gen. 98A (1964) (reprinted in advance

sheet only). Funds appropriated for such projects will

continue to be spent until the projects are completed.

Yet state officials will apparently be powerless to en

force the nondiscrimination pledge that federal law

compelled them to sign—for example, by obtaining the

requisite nondiscriminatory guarantee from the rede

veloper. This is clearly contrary to the principle that

a state may not back out of an agreement with the

Federal Government or with another State because of

a supervening change in its public policy. See West

Virginia ex rel. Dyer v. Sims, 341 U.S. 22 (1951).

8

The third set of projects are those now on the

drawing board but not yet contracted for. It is here

that the conflict between state and federal law is the

sharpest. Since November 1964 all federal funds for

future projects have been cancelled because Article I,

§ 26 appears to make state and local officials unable

to sign the nondiscrimination pledge that federal law

requires. See Los Angeles Times, December 3, 1964,

Part II, p. 8. This means, at the very least, a tragic

loss for the people of California—some $250- million

further funds had been planned for renewal projects

in the State over the next four years. Even more criti

cal is the constitutional issue raised by the square

conflict between two bodies of law: The recent amend

ment of the California Constitution interposes state

law between the Federal law and the achievement of

a vital federal objective of urban renewal and decent

housing for slum dwellers. It would be harder to

imagine a clearer violation of the Supremacy Clause.

The strong federal requirement of nondiscrimina

tion in urban renewal has been reinforced by the

passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Title V I of

the act partially supersedes the Executive Order—

although the Act makes clear that the Order remains

in full force and effect for those areas of federally

assisted housing not covered by the new law. (For

example, § 605 of the Civil Rights Act excludes from

the nondiscriminatory obligations of Title V I “ a con

tract o f insurance or guaranty.” This language thus

excludes such activities as the FHA home mortgage

insurance program. The Executive Order continues

9

to require nondiscrimination, however, in all future

FHA-assisted single and multi-family developments.

See “ Civil Rights Under Federal Programs,” Civil

Rights Commission, Jan. 1965, p. 13). Thus, while

there is some question precisely where and to what

extent the Civil Rights Act does supersede the Execu

tive Order, there is no question that all programs

which were covered prior to passage of the new law

continue to be covered.

In several respects, in fact, the Civil Rights Act

goes beyond the nondiscrimination requirement of the

Executive Order. Under recent Housing and Home

Finance Agency Regulations implementing Title VI,

all urban renewal projects that had not yet reached

the land disposition stage by January 4, 1965, are sub

ject to the nondiscrimination requirements of the new

law, regardless of the date on which the loan and

grant contract was executed. Thus Title V I has the

effect o f subjecting the great bulk of federally as

sisted urban renewal activity to the requirement of

nondiscrimination, because of the typically long time

lag between execution of the loan and grant contract

and final disposition of the land.

The Civil Rights Act goes further than the Execu

tive Order in at least one other area: in public hous

ing, all low-rent projects still receiving annual con

tributions from the Public Housing Administration

on January 4, 1965 are subject to the requirements of

Title V I, regardless of the date on which the annual

contributions contract was signed. This means that

virtually every public housing project authorized since

10

1937, when the program was initiated, is now subject

to the nondiscrimination requirement.

In these several areas where Title V I has extended

or expanded the effect of the Executive Order, non-

discriminatory undertakings previously required of

local urban renewal authorities by the Order would

now appear to be required by Act of Congress. I f

there was ever any question whether California law

could abridge the force of a presidential decree, there

can be no question that any inconsistent state law

must yield to federal legislation. Thus to the extent

that Article I, § 26 purports to disable state and local

officials from signing or enforcing a nondiseriminatory

undertaking as a condition of participation in federal

housing programs or federal urban renewal projects,

it is clearly invalid by reason of conflict with the Su

premacy Clause.

Several lines of U.S. Supreme Court decisions rein

force these conclusions. Closely in point are the San

Joaquin Valley Reclamation cases, culminating in

Ivanhoe Irrigation District v. McCracken, 357 U.S. 275

(1958), on remand, 53 Cal. 2d 692 (1960). There the

Court held, inter alia, that when Congress has enacted

a comprehensive scheme to govern federally assisted

reclamation projects necessary for the national wel

fare, inconsistent provisions of state law must yield.

Thus state law was struck down to the extent it pur

ported to invalidate the “ excess lands” provisions in

contracts between the United States and state and

local agencies involved in the reclamation project.

There was, the Court affirmed, no doubt about the

11

power of the Federal Government “ to impose reason

able conditions on the use of federal funds, federal

property, and federal privileges.” Consequently, the

Court continued, “ a State cannot compel use of fed

eral property on terms other than those prescribed or

authorized by Congress.” When conflict between state

and federal law threatened to obstruct the federal pur

pose, “ Article VI of the Constitution, of course, for

bids state encroachment on the supremacy of federal

legislative action.” 357 U.S. at 295. A contrary hold

ing might well have frustrated or crippled the carry

ing out of a program which—like urban renewal—was

in the judgment of the Congress vital to the national

interest. See Taylor, Destruction of Federal Reclama

tion Policy ? The Ivanhoe Case, 10 Stan L. Rev. 76,

83-84, 111 (1957). The present case should be a fortiori

from Ivanhoe—since the requirement of nondiscrimi

nation in the urban renewal contracts is more clearly

compelled by the Federal Constitution than the excess

lands provisions of the reclamation contracts.

The relevance of the Ivanhoe doctrine for the pres

ent case may be underscored by a hypothetical ex

ample. Suppose the State of Nevada decided that it

wanted no limited-access Interstate Highways built

within its borders. Suppose further, to implement that

decision, a provision were added to the State Consti

tution forbidding state officials from aiding the con

struction of the highways in any respect—even by

preventing obstruction or interference by private

citizens. Such a provision would mean, at the very

least, that the State could make no contribution to the

12

construction of the highway, which would very likely

cancel the project under present statutes. (See 23

U.S.C. § 120 (1958).) It would also completely close

the doors of the state courts to any condemnation or

other proceedings in connection with the highway.

Even more serious, state police would be barred by the

state constitution from moving squatters or legally

dispossessed owners off lands condemned for the right

of way. Nor could they protect the equipment of fed

eral contractors from looting by local hoodlums. Thus

it would be very doubtful whether any Interstate high

way could be built in Nevada if the State withdrew its

cooperation in this way.

Undoubtedly the United States Supreme Court

would strike down any such outlandish state inter

position as this. Such state action would presumably

fare no better under the Supremacy Clause than state

attempts, for example, to thwart the construction of

federally licensed dams, First Iowa Hydro-Electric

Coop. v. EEC, 328 U.S. 152 (1916) ; FPC v. Oregon,

319 U.S. 435 (1955) ; state attempts to bar federally

licensed patent attorneys from carrying on their prac

tice in the state without joining the state bar, Sperry

v. Florida Bar, 373 U.S. 379 (1963) ; or state regula

tion of federal contractors in ways that interfere with

the implementation of federal policies in the State,

Miller v. Arkansas, 352 U.S. 187 (1956). Nor should

the recent amendment to the California Constitution

fare better than state interpositions of this sort have

fared—for the direct conflict between federal and state

law seems logically indistinguishable from the Nevada

13

highway case. The frustration of a vital federal ob

jective is equally apparent and just as serious.

B. Article I, § 26 Conflicts With Other Federal Policies and

Interests.

There are other and subtler forms of conflict that

are bound to result as the full impact of the consti

tutional amendment is felt in California. It may no

longer be possible, for example, for state officials to

cooperate with the U.S. State Department in guaran

teeing or offering nondiscriminatory housing for con

suls, diplomats or prominent visitors from Asian and

African nations. ISTor will officials of the University

of California or the State Colleges be able to offer

any guarantee to exchange students from these coun

tries that they will find suitable off-campus housing

when they come to California—since these institutions

are presumably no longer able to exact the nondis

crimination pledge heretofore required of private land

lords listing accommodations with the campus housing-

offices. For a state which boasts a campus with more

foreign students than any other institution in the

country, this is a deplorable situation—and one which

may seriously interfere with a strong federal interest

in promoting the exchange of scholars with other

nations.

For similar reasons California officials will presum

ably be unable to join officials of several other states

who have cooperated with federal military officials in

providing access to nondiscriminatory off-base housing

for Negro service personnel and their families. There

14

can be no doubt that the Federal military power in

cludes the incidental power to provide for housing of

all persons involved in the military effort, in peace

time as well as in war, Woods v. Gloyd W. Miller Go.,

333 U.S. 138 (1948). And the unavailability of non-

discriminatory off-base housing could cripple military

operations in California.

There may also be a serious question whether Cali

fornia education officials will be able to accept federal

funds made available under Title IY of the Civil

Rights Act of 1964 to help local school authorities “ in

dealing with problems incident to desegregation . . .”

(§ 405(a)) This is not because the California consti

tutional amendment affects school desegregation as

such. The problem stems from the view of the State

Board of Education that de facto racial segregation,

where it exists in California, is very largely the prod

uct of “ patterns of residential segregation . . . ” The

State Board has recently argued that “ discrimination

in housing is at the root of racial imbalance in

schools,” and that “ a constitutionally inviolate right

to discriminate in the sale of real estate would render

inadequate the means available to the Board to alle

viate de facto segregation in the schools.” (Brief for

the Attorney General and the California State Board

of Education as Amici Curiae, Lewis v. Jordan, Sac.

7549, p. 5.) Thus the constitutional amendment ap

pears to deprive school officials of the very means of

combatting de facto segregation which, would make

them best able to use the federal funds offered under

Title IV.

15

C. Article I, § 26 Closes the Doors of the California Courts to

Causes of Action Based Upon the U.S. Constitution and Acts

of Congress.

It is basic constitutional law that a State may not

arbitrarily close its courts to actions based upon fed

eral law, Claflin v. Houseman, 93 U.S. 130 (1876).

The United States Supreme Court has repeatedly

denied that any supposed conflict between state policy

and the federal law on which a suit is based would

warrant the dismissal of the suit. Second Employers’

Liability Cases, 223 U.S. 1, 57 (1911) ; see Note, 60

Harv. L. Rev. 966, 969 (1947). The Claflin case sup

plied the rationale for this doctrine:

I f an Act of Congress gives a penalty to a party

aggrieved, without specifying a remedy for its

enforcement, there is no reason why it should not

be enforced, if not provided otherwise by some act

of Congress, by a proper action in a state court.

The fact that a state court derives its existence

and functions from the state laws is no reason

why it should not afford relief; because it is

subject also to the laws of the United States, and

it is just as much bound to recognize these as

operative within the State as it is to recognize the

state laws. The two together form one system of

jurisprudence, which constitutes the law of the

land for the State; and the courts of the two

jurisdictions are not foreign to each other, nor

to be treated by each other as such, but as courts

of the same country, having jurisdiction partly

different and partly concurrent. Claflin v. House

man, 93 U.S. 130, 137 (1876).

Recently the obligation of the state courts to entertain

federal causes of action has been extended to penal as

16

well as remedial statutes, at least where a similar

remedy is available under state law, Testa v. Katt, 330

U.S. 386 (1947). This is so despite state courts’ strong

insistence that the entertainment of such suits is con

trary to state public policy. The strength of this prin

ciple has been recognized at least once by the Cali

fornia Supreme Court, McCarroTl v. Los Angeles

County District Council of Carpenters, 49 Cal. 2d 45,

61 (1957).

There are several specific sources of federal claims

to which the California constitutional amendment

would appear to close the doors of the state courts.

The most obvious is the kind of suit recognized in

Ming v. Horgan, supra, in which the right of a Negro

not to be discriminated against in the purchase of

housing financed in part with state and federal funds

was grounded squarely on the federal statutes and the

Fourteenth Amendment. Assuming that the word

“ subdivision” in the constitutional amendment in

cludes state courts, there seems little doubt that a suit

identical to Ming v. Horgan would now have to be

dismissed. The sole reason for dismissal would be a

state policy, reflected in the constitutional amendment,

purportedly in conflict with federal law and policy.

That is a result which seems hardly compatible with

the Supremacy Clause as the United States Supreme

Court has applied it to the state courts.

There are at least three other sources in the federal

law from which a cause of action might be implied in

favor of a minority group member discriminated

against in the sale or rental of housing. First, there

17

is the old statute to which reference has already been

ma(ie—42 U.S.C. § 1982 which provides: “ All citizens

of the United States shall have the same right, in

every State and Territory, as is enjoyed by white citi

zens thereof to inherit, purchase, lease, sell, hold and

convey real and personal property.” Although these

original civil rights statutes are designed chiefly for

federal court enforcement, nothing in the federal law

precludes recognition of such rights in the state courts.

Cf. Napier v. Church, 132 Tenn. I l l , 177 S.W. 56

(1915).

A suit might also be based directly upon the Hous

ing A ct’s implied guarantee of equal treatment in

federally assisted housing. Although persons affected

by a renewal project have no standing to challenge

the proposed expenditure of federal funds by the re

development agency, In re Redevelopment Plan for

Bunker Hill, 61 Cal. 2d 21 (1964), that decision in no

way forecloses the possibility of suit in the state

courts for injury resulting from misuse of federal

funds. Cf. Smith v. Holiday Inns of America, Inc.,

336 F.2d 630 (6th Cir. 1964). Yet the adoption of

Article I, § 26, would appear to bar any such suits

based upon alleged violations of federal law—even

though the state courts would remain open to suits

challenging the use of funds under state laws, such as

the California Housing Authorities Law. Cf. Kleiber

v. City and County of San Francisco, 18 Cal. 2d 718

(1941). This is precisely the sort of discrimination

against federal rights that Claflin v. Houseman, supra,

and the later U.S. Supreme Court cases, do not per

IS

mit. See Clancy & Neinerovsld, Some Legal Aspects of

Proposition Fourteen, 16 Hastings L.J. 3, 13 n.47

(1964).

Finally a private action might be based upon the

November 1962 Executive Order on Equal Opportun

ity in Housing. While there have apparently been no

suits yet based upon the Order, private actions based

upon alleged violations of federal administrative regu

lations that create no express private remedies are by

no means novel. See, e.g., Neiswonger v. Goodyear Tire

& Rubber Co., 35 F.2d 761 (N.D. Ohio 1929); Roose

velt Field v. Town of North Hempstead, 84 F. Supp.

456 (E.D. N.Y. 1949) ; Note, 77 Harv. L. Rev. 285

(1963). Indeed, one federal court of appeals recently

declined to allow a private claim based upon the Execu

tive Orders concerning Equal Employment Opportun

ity—but only because such actions would not be com

patible with the particular purposes of the orders in

question. Farmer v. Philadelphia Elec. Co., 329 F.2d

3 (3d Oir. 1964). Nothing in that decision forecloses

the implication of private remedies for the violation

of other Executive Orders.

Thus there are at least four distinct sources from

which a private cause of action under federal law

might be derived—the Fourteenth Amendment, the

civil rights statute that deals with housing, the Na

tional Housing Act, and President Kennedy’s Execu

tive Order. Yet the enactment of the California con

stitutional amendment appears to close the doors of

the California courts to all such suits. That foreclo

sure seems in square conflict with a long line of II. S.

19

Supreme Court decisions which have put beyond

doubt the principle that state courts may not, con

sistent with the Supremacy Clause, refuse to entertain

causes of action grounded on federal law while keep

ing their doors open to suitors pressing similar state-

law claims.

Dated, San Francisco, California,

June 11, 1965.

R ic h a r d A. B a n c r o f t ,

J a c k G r e e n b e r g ,

A ttorneys for Amicus Curiae.

Of Counsel:

R o bert M . O ’N e il .