Liddell v. State of Missouri Opinion of the Court En Banc

Public Court Documents

February 8, 1984

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Liddell v. State of Missouri Opinion of the Court En Banc, 1984. 44fb0049-bb9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/7210ae0f-587b-4541-84f8-f0a0bd15cbd8/liddell-v-state-of-missouri-opinion-of-the-court-en-banc. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

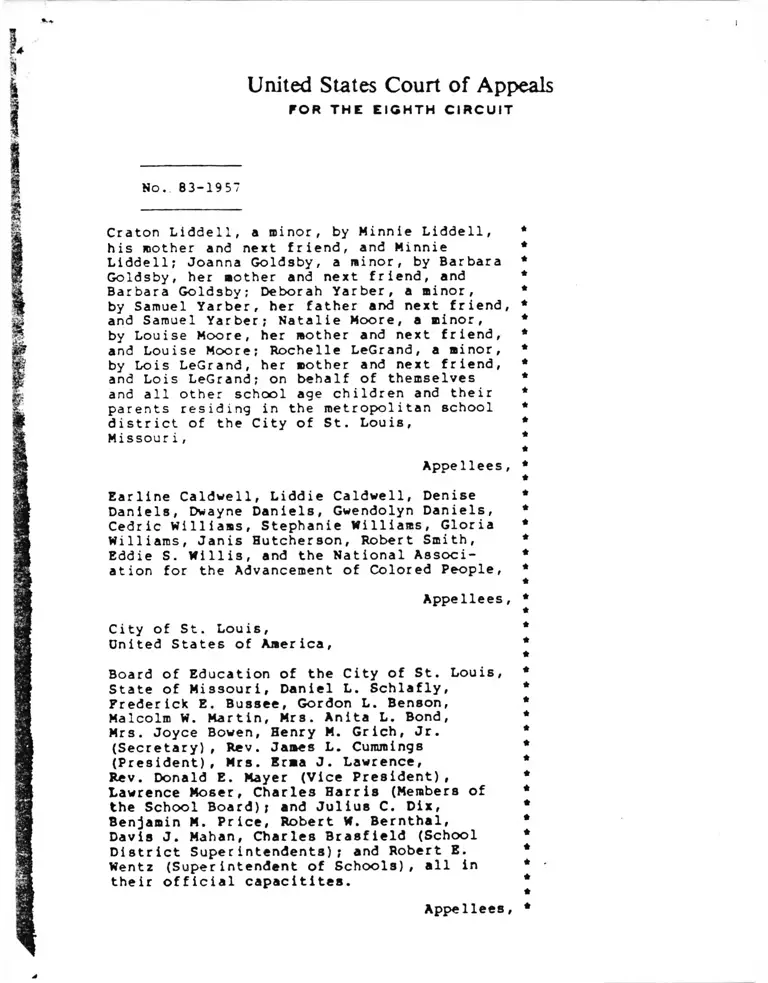

United States Court of Appeals

FOR THE EIGHTH CIRCUIT

No. 83-1957

Craton Liddell, a minor, by Minnie Liddell,

his mother and next friend, and Minnie

Liddell; Joanna Goldsby, a minor, by Barbara

Goldsby, her mother and next friend, and

Barbara Goldsby; Deborah Yarber, a minor,

by Samuel Yarber, her father and next friend,

and Samuel Yarber; Natalie Moore, a minor,

by Louise Moore, her mother and next friend,

and Louise Moore; Rochelle LeGrand, a minor,

by Lois LeGrand, her mother and next friend,

and Lois LeGrand; on behalf of themselves

and all other school age children and their

parents residing in the roetropolitan school

district of the City of St. Louis,

Missour i ,

Appellees,

Earline Caldwell, Liddie Caldwell, Denise

Daniels, Dwayne Daniels, Gwendolyn Daniels,

Cedric Williams, Stephanie Williams, Gloria

Williams, Janis Hutcherson, Robert Smith,

Eddie S. Willi3, and the National Associ

ation for the Advancement of Colored People,

Appellees,

City of St. Louis,

United States of America,

Board of Education of the City of St. Louis,

State of Missouri, Daniel L. Schlafly,

Frederick E. Bussee, Gordon L. Benson,

Malcolm W. Martin, Mrs. Anita L. Bond,

Mrs. Joyce Bowen, Henry M. Grich, Jr.

(Secretary), Rev. James L. Cummings

(President), Mrs. Erma J. Lawrence,

Rev. Donald E. Mayer (Vice President),

Lawrence Moser, Charles Harris (Members of

the School Board); and Julius C. Dix,

Benjamin M. Price, Robert W. Bernthal,

Davis J. Mahan, Charles Brasfield (School

District Superintendents); and Robert B.

Wentz (Superintendent of Schools), all in

their official capacitites.

Appellees,

*

of

of

St Louis County, Gene McNary, County

Executive; Harlow Richardson, CountyGeorge C. Le.chman Collection

St. Louis County Contract Account,

Affton Board of Education, Bayless Board of

Educat ion, Brentwood Board of Education,

ClaytonBoard of Education, Ferguson-

Florissant Reorganized R-2, Hancock Place

Board of Education, Hazelwood Board of

Education, Jennings Board of Education,

Kirkwood Board of Education, Ladue Board

Education, Lindbergh Board of Education,

^ l er r “ iUee^aJd SrSduSStion.

Normtnd? Board of Education, Parkway Board

S M -c tion.

Over v i ew Gardens Board of Education,

Rockwood Board of Education, Valley Park

Board of Education, University City Board

Education, Webster Groves Board of

Education and Wellston Board of Education,

*

*

of

Appellees,

in his official capacity; The State ° Missouri Board of Education; Christopher S.

Bind Governor of the State of StateJohn Ashcroft, Attorney General of the State

of Missouri; Melvin E. Carnahan,

nf the State of Missouri; Stephen u., - j rnmirii ioner of Adniinistration of

the^State oHllssou?!; ?he State of Missouri

Board of Education and its inen'̂ e^s% ^ in Williamson (President), Jinuny Robertso

(Vice President), Grover A,

Cobble, Dale M. Thompson,

and Robert Welling,

Gamm, Delmar A.

Donald W. Shelton

★

★

♦

*

★

★

★

★

★

*

*

*

*

♦

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

♦

*

*

*

*

i t

i t

i t

Appeal from the

States District

for the Eastern

District of Mis

United

Court

sour i.

Appellants.

No. 83-2033

Craton Liddell, a minor, by Minnie Liddell,

his mother and next friend, and Minnie

Liddell; Joanna Goldsby, a minor, by Barbara

Goldsby, her mother and next friend, and

Barbara Goldsby; Deborah Yarber, a minor, by

Samuel Yarber, her father and next friend,

and Samuel Yarber; Natalie Moore, a minor,

by Louise Moore, her mother and next friend,

and Louise Moore; Rochelle LeGrand, a minor,

by Lois LeGrand, her mother and next friend,

and Lois LeGrand; on behalf of themselves

and all other school age children and their

parents residing in the metropolitan school

district of the City of St. Louis, Missouri,

★

*

★

★

★

★

★

♦

★

*

★

★

★

*

*

Appellees, * ★

Earline Caldwell, Liddie Caldwell, Denise *

Daniels, Dwayne Daniels, Gwendolyn Daniels, *

Cedric Williams, Stephanie Williams, Gloria *

Williams, Janis Hutcherson, Robert Smith, *

Eddie S. Willis, and the National Associ- *

ation for the Advancement of Colored People, **

Appellees, * *

City of St. Louis, *

United States of America, *

Board of Education of the City of St. Louis,

State of Missouri, Daniel L. Schlafly,

Frederick E. Bussee, Gordon L. Benson,

Malcolm W. Martin, Mrs. Anita L. Bond,

Mrs. Joyce Bowen, Henry M. Grich, Jr.

(Secretary), Rev. James L. Cummings

(President), Mrs. Erma J. Lawrence,

Rev. Donald E. Mayer (Vice President),

Lawrence Moser, Charles Harris (Members of

the School Board); and Julius C. Dix,

Benjamin M. Price, Robert W. Bernthal,

David J. Mahan, Charles Brasfield (School

District Superintendents); and Robert E.

Wentz (Superintendent of Schools), all in

their official capacities,

Appellees,

*

*

★

*

★

*

*

★

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

St. Louis County, Gene McNary, County

Executive, Harlow Richardson, County

3

Treasurer, George C. Leachman, Collection of

St. Louis Contract Account,

Appellees,

Affton Board of Education, Bayless Board of

Education, Brentwood Board of Education,

Clayton Board of Education, Ferguson-

Flor issant Reorganized R-2, Hancock Place

Board of Education, Hazelwood Board of

Education, Jennings Board of Education,

Kirkwood Board of Education, Ladue Board of

Education, Lindbergh Board of Education,

MaDlewood-Richmond Heights Board of

Education, Mehlville Board of Education,

Normandy Board of Education, Parkway Board

of Education, Pattonville Board of Education,

Ritenour Board of Education, Riverview

Gardens Board of Education, Rockwood Board of

Education, Valley Park Board of Education,

University City Board of Education, Webster

Groves Board of Education and Wellston Board

of Education,

Appellees,

State of Missouri; Arthur Mallory, Commis

sioner of Education of the State of

Missouri, in his official capacity; The

State of Missouri Board of Education;

Christopher S. Bond, Governor of the State of

Missouri; John Ashcroft, Attorney General of

the State of Missouri; Melvin E. Carnahan,

Treasurer of the State of Missouri; Stephen

C. Bradford, Commissioner of Administration

of the State of Missouri; The State of

Missouri Board of Education and its members.

Erwin A. Williamson (President) , Jimmy

Robertson (Vice President), Grover A. Gamm,

Delmar A. Cobble, Dale M. Thompson, Donald

W. Shelton and Robert Welling,

Appellees,

St. Louis Teachers Union, Local 420,

American Federation of Teachers, Appellant.

★

★

★

★

*

*

★

★

*

*

★

★

★

*

*

★

*

★

★

★

★

★

★

★

★

★

★

*

i t

i t

i t

i t

i t

i t

i t

i t

i t

i t

i t

i t

i t

i t

i t

i t

i t

i t

i t

★

*

Appeal from the Uni

States District Cou

for the Eastern

District of Missour

4

No. 83-2118

Craton Liddell, a minor, by Minnie Liddell,

his mother and next friend, and Minnie

Liddell; Joanna Goldsby, a minor, by Barbara

Goldsby, her mother and next friend, and

Barbara Goldsby; Deborah Yarber, a minor, by

Samuel Yarber, her father and next friend,

and Samuel Yarber; Natalie Moore, a minor, by

Louise Moore, her mother and next friend,

and Louise Moore; Rochelle LeGrand, a minor,

by Lois LeGrand, her mother and next friend,

and Lois LeGrand; on behalf of themselves

and all other school age children and their

parents residing in the metropolitan school

district of the City of St. Louis, Missouri,

Appellees,

Earline Caldwell, Liddie Caldwell, Denise

Daniels, Dwayne Daniels, Gwendolyn Daniels,

Cedric Williams, Stephanie Williams, Gloria

Williams, Janis Hutcherson, Robert Smith,

Eddie S. Willis, and the National Associ-

iation for the Advancement of Colored People,

Appellees,

City of St. Louis, Appellant.

United States of America,

Appellee,

Board of Education of the City of St. Louis,

State of Missouri, Daniel L. Schlafly,

Frederick E. Bussee, Gordon L. Benson,

Malcolm W. Martin, Mrs. Anita L. Bond,

Mrs. Joyce Bowen, Henry M. Grich, Jr.

(Secretary), Rev. James L. Cummings

(President), Mrs. Erma J. Lawrence,

Rev. Donald E. Mayer (Vice President),

Lawrence Moser, Charles Harris (Members of

the School Board) and Julius C. Dix,

Benjamin M. Price, Robert W. Bernthal,

David J. Mahan, Charles Brasfield (School

District Superintendents); and Robert E.

Wentz (Superintendent of Schools), all in

their official capacities,

Appellees ,

St. Louis County, Gene McNary, County

Executive, Harlow Richardson, County

Treasurer, George C. Leachnan, Collection of

St. Louis County Contract Account,

Appellees,

Affton Board of Education, Bayless Board of

Education, Brentwood Board of Education,

Clayton Board of Education, Ferguson-

Florissant Reorganized R-2, Hancock Place

Board of Education, Hazelwood Board of

Education, Jennings Board of Education,

Kirkwood Board of Education, Ladue Board

of Education, Lindbergh Board of Education,

Maplewood-Ri chmond Heights Board of

Education, Mehlville Board of Education,

Normandy Board of Education, Parkway Board

of Education, Pattonville Board of

Education, Ritenour Board of Education,

Riverview Gardens Board of Education,

Rockwood Board of Education, Valley Park

Board of Education, University City Board

of Education, Webster Groves Board of

Education and Weliston Board of Education,

Appellees

State of Missouri; Arthur Mallory,

Commissioner of Education of the State of

Missouri, in his official capacity; The

State of Missouri Board of Education;

Christopher S. Bond, Governor of the State

of Missouri; John Ashcroft, Attorney

General of the State of Missouri; Melvin E.

Carnahan, Treasurer of the State of

Missouri; Stephen C. Bradford, Commissioner

of Administration of the State of Missouri;

The State of Missouri Board of Education

and its members: Erwin A. Williamson

(President), Jimmy Robertson (Vice

President), Grover A. Gamm, Delmar A.

Cobble, Dale M. Thompson, Donald W. Shelton

and Robert Welling,

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

it

i t

it

it

*

*

♦

★

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

* Appeal from the United

States District Court

for the Eastern

District of Missouri.

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

Appellees,

St. Louis Teachers Union, Local 420,

American Federation of Teachers,

Appellant

No. 83-2140

In Re : City of St. Louis, Paul

and Ronald A. Leggett,

Berra

Peti tioners

Nc . 83-2220

Petition for Writ o

Prohibition.

Cr a ton Liddell, a minor, by Minnie Liddell, *

his mother and next friend, and Minnie

Liddell; Joanna Goldsby, a minor, by Barbara *

Goldsby, her mother and next friend, and

Barbara Goldsby; Deborah Yarber, a minor,

by Samuel Yarber, her father and next friend,

and Samuel Yarber; Natalie Moore, a minor,

by Louise Moore, her mother and next friend,

and Louise Moore; Rochelle LeGrand, a minor,

by Lois LeGrand, her mother and next friend,

and Lois LeGrand; on behalf of themselves *

and all other school age children and their

parents residing in the metropolitan school

district of the City of St. Louis, Missouri, ^

Appellees, * *

Earline Caldwell, Liddie Caldwell, Denise *

Daniels, Dwayne Daniels, Gwendolyn Daniels,

Cedric Williams, Stephanie Williams, Gloria

Williams, Janie Hutcherson, Robert Smith,

Eddie S. Willis, and the National Association

for the Advancement of Colored People,Appellees, * *

*City of St. Louis, #

United States of America, *

Board of Education of the City of St. Louis, *

State of Missouri, Daniel L. Schlafly,

7

*

*

*

*

*

*

i t

i t

i t

it

i t

i t

. • «, v Bussee, Gordon L. Benson,Frederick E. Bussee, ~ Anita L . Bond,

MrsC°Jovce Bowen?'Henry M. Grich, Jr.

(Secretary), Rev.

(PteS;denU 'E ^ M ; ye r V i c e Presided) ,

LawUnc^Moser , Charles Harris (Members of

C Knni BnarJ|- and Julius C. Dix,

Benjamin M ?ri c e , Rober t ̂«• f® * ^ tlJ|chool

their official capacities,

Appellees,

St. Loui, county Sene ?=Nary,, ̂ ounty

George C. Leachman. Collection of

I t Louie County Contract Account,

Appe1lees,

Bod-a of Education, Baylees Board of

Edu~a"iont Brentwood Board of Education,

Ili'JtoJ:°Si.rd Of Education,

Educat'ionl^Mehlv^ll^Board^of ̂ Education

o?1 Educat^on)^Fattonv<ille B ^ r d of Education,

Ritenour Board of Education, * ^ « " % osra

Gardens Board of Education, B Education,o£ E d u c a t i o n , Valley Park Board Mebster

o? Education and Wellston Board

of Education ,

*

i t

i t

i t

*

*

*

*

*

*

it

★

*

★

it

' ★

♦

*

*

★

*

*

it

r

i t

★

*

t

i t

i t

i t

V .

sioner°ofMEducat ion^of htheMState^ofC° ^ iS~

S t ^ e ^ f V i S s S i r i ^ o a l d ^ f ^ d u c a t l o n ; ^ ^ ^

o?tmI?ouri!SiohnnAshc?of^Attorney General

Appeal from, the Unite"

States District Court

for the Eastern

District of Missouri.

8

Stephen C. Bradford, Commissioner of Admini

stration of the State of Missouri; The State

of Missouri Board of Education and its

Members Erwin A. Williamson (President),

Jimmy Robertson (Vice President), Grover A.

Gamm, Delmar A. Cobble, Dale M. Thompson,

Donald W. Shelton and Robert Welling,

St. Louis Teachers Union, Local 420,

American Federation of Teachers,

North St. Louis Parents and Citizens for

Quality Education, an unincorporated

association, including William Upchurch,

Vivian Ali, and Dorothy Robins, parents of

children attending the St. Louis city public

schools and members of the regional plaintiff

classes who objected to the settlement

ag reement,

Appe Hants.

No. 83-2554

Craton Liddell, a minor, by Minnie Liddell,

his mother and next friend, and Minnie

Liddell; Joanna Goldsby, a minor, by Barbara

Goldsby, her mother and next friend, and

Barbara Goldsby; Deborah Yarber, a minor, by

Samuel Yarber, her father and next friend,

and Samuel Yarber; Natalie Moore, a minor,

by Lou i se Moore, her mother and next friend/

and Louise Moore; Rochelle LeGrand, a minor,

by Lois LeGrand, her mother and next friend,

and Lois LeGrand; on behalf of themselves

and all other school age children and their

parents residing in the metropolitan school

district of the City of St. Louis, Missouri,

Appellees

Earline Caldwell, Liddie Caldwell, Denise

Daniels, Dwayne Daniels, Gwendolyn Daniels,

Cedric Williams, Stephanie Williams, Gloria

Williams, Janis Hutcherson, Robert Smith,

Eddie S. Willis, and the National Associ

ation for the Advancement of Colored People,

Appellees

City of St. Louis,

United States of America,

Board of Education of the City of St. Louis,

State of Missouri, Daniel L. Schlafly,

Frederick E. Bussee, Gordon L. Benson,

Malcolm W. Martin, Mrs. Anita L. Bond,

Mrs. Joyce Bowen, Henry M. Grich, Jr.

(Secretary), Rev. James L. Cummings

(President), Mrs. Erma J. Lawrence,

Rev. Donald E. Mayer (Vice President),

Lawrence Moser, Charles Harris (Members of

the School Board); and Julius C. Dix,

Beniamin M. Price, Robert W.Bernthai,

David J. Mahan, Charles Brasfield (School

District Superintendents); and Robert E.

Wentz (Superintendent of Schools), all in

their official capacities,

Appellees

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

★

*

*

★

*

*

St. Lo'jis County, Gene McNary, County ^

Executive, Harlow Richardson, County ̂

Treasurer, George C. Leachman, Collection of ̂

St. Louis County Contract Account,

Appellees,

Affton Board of Education, Bayless Board of

Education, Brentwood Board of Education,

Clayton Board of Education, Ferguson-

Florissant Reorganized R-2, Hancock Place

Board of Education, Hazelwood Board of

Education, Jennings Board of Education,

Kirkwood Board of Education, Ladue Board of

Education, Lindbergh Board of Education,

Maolewood-Richmond Heights Board of

Education, Mehlville Board of Education,

Normandy Board of Education, Parkway Board

of Education, Pattonville Board of Education,

Ritenour Board of Education, Riverview

Gardens Board of Education, Rockwood Board

of Education, Valley Park Board of Education,

University City Board of Education, Webster

Groves Board of Education and Wellston Board

of Education,

Appellees,

*

*

★

*

*

★

*

♦

*

*

*

♦

*

*

*

♦

*

*

*

*

*

*

10

State of Missouri; Arthur Mallory, Commis

sioner of Education of the State of Missouri, *

in his official capacity; The State of

Missouri Board of Education; Christopher S.

Bond, Governor of the State of Missouri;

John Ashcroft, Attorney General of the State *

of Missouri; Melvin E. Carnahan, Treasurer

of the State of Missouri; Stephen C.

Bradford, Commissioner of Administration of

the State of Missouri; The State of Missouri *

Board of Education and its members: Erwin A. *

Williamson (President), Jimmy Robertson

(Vice President), Grover A. Gamm, Delmar A.

Cobble, Dale M. Thompson, Donald W. Shelton

and Robert Welling, Appellants. *

Appeal from the United

States District Court

for the Eastern

District of Missouri.

Submi tted:

Filed:

November 28, 1983

February 8, 1984

Opinion of the Court En banc, LAY, Chief Judge, HEANEY, BRIGHT'

ROSS, McMILLIAN, ARNOLD, and FAGG, Circuit Judges, with JOHN R.

GIBSON, Circuit Judge, concurring in part and dissenting in part,

and BOWMAN, Circuit Judge, dissenting.

The Caldwell and Liddell plaintiffs, representing black stu

dents and parents of the St. Louis City School District, the City

School District, and several suburban school districts have

entered into a unique and comprehensive settlement agreement

designed to further desegregation in the city schools. The

United States District Court has approved the agreement and has

entered orders to fund the plan.

With the exceptions and limitations noted in the opinion, we

approve the agreement and the order entered by the district court

with respect to:

The voluntary transfers of students between the city and

suburban schools and the establishment of additional magnet

11

. „ t-hp Citv School Districtschools and integrative programs in the y

as necessary to the successful desegregation of *

schools;

The quality education programs for the nonintegrated schools

in the City School District;

The quality education programs for all schools in the City

School District, but only insofar as these programs ave ^

shown to be necessary for the city to retain its Class

rating or to be essential to the successful desegregation o

the city schools as hereinafter set forth;

T,e provisions of the district court's order requiring the

State of Missouri, as the primary constitutional violator,

pay the full cost of city to suburb and suburb to.clty

fers. maanet schools and integrative programs in the y

schools, and one-half of the cost of the quality educate

programs in the city schools. We decline to approve t

district court order insofar as it requires the State to fund

student transfers between suburban school dlSt“ CtS

fund magnet schools or integrative programs in those

districts;

improved facilities for the city schools. We require further

planning, however, before construction begins. *' J

with particularity the projects that will be un er a ,

to take account of a probable decline in the city school

population in the next few years.

. . Hi strict court roust take beforeWe outline the steps that the district co

it can require an increase in real estate taxes to fund the City

Board's share of the quality education component of the pBoard S a n a i c ^ >. os that the court must

without a vote of the people, and t P .. ., . . 0 _ Ww, issued to fund the citytake before it can require that bonds b

Board's share of capital improvements without a similar vote.

12

make it clear, however, that no party found to have violated the

Constitution will be permitted to escape its obligation to

provide equal educational opportunity to the black children of

S t . Lou i s.

We make it clear that the suburban schools meeting the goals

set forth in the plan will receive a final judgment declaring

that they have satisfied their desegregation obligations.

Finally, we recognize that the settlement agreement and the

district court's order will have to be modified to conform to

this opinion, and we are aware that the cost of the plan, partic

ularly to the State, will be significantly reduced. In our view,

however, the changes do not alter the essential character of the

plan, and they preserve its constitutionality. The parties to

the settlement agreement are required to decide promptly whether

they will accept the changes set forth in this opinion. If they

refuse to dc so, the interdistrict trial will proceed. I.

I. PROCEDURAL HISTORY.

In February, 1972, a group of black parents (the Liddell

plaintiffs) filed a class action against the City Board, the

board members, and school administrators, alleging racial segre

gation in the city's schools in violation of the fourteenth

amendment. The defendants' motion to join the State of Missouri

and St. Louis County (containing the suburban school districts)

as codefendants was denied on December 1, 1973. A year la^er,

the parties entered into a consent agreement which provided for

an increase in the number of minority teachers and included a

pledge by the City Board to attempt to "relieve the residence-

based racial imbalance in the City schools." Liddell— v_.— Bd_j— of

Educ., 469 F. Supp. 1304, 1310 (E.D. Mo. 1979).

13

The case first came before this Court in 1976,1 when the

Caldwell plaintiffs appealed the district court's denial of their

right to intervene. We granted intervention, but declined to

pass on the constitutionality of the consent decree. Liddell

Caldwell, 546 F.2d 766 (8th Cir.) (Liddell I), cert, denied, 433

U.S. 914 (1976,. We encouraged the United States and State of

Missouri to intervene, recommended the creation of a biracial

citizens committee to assist in formulating a desegregation plan,

and suggested voluntary interdistrict student transfers as one

remedial too1. Id. at 7 7 4.

Desegregation plans were developed and submitted to the

district court by the City Board, the Liddell plaintiffs, the

Caldwell plaintiffs, and the United States as amicus curiae.

Before approving any plan, the district court ordered a trial to

determine whether there had been a constitutional violation and

to frame a remedy if a violation was found. The United States,

the City of St. Louis, and two white citizens' groups were

allowed to intervene as plaintiffs. The State of Missouri, the

State Board of Education, and the Commissioner of Education were

added as defendants. The district court found no constitutional

violation, and held that the City Board had achieved a unitary

school system, in 1954-56 through its "neighborhood school

policy." Liddell v. Bd. of Educ., supra, 469 F. Supp. at 1360-

1361.

We reversed the district court in Adams v_.— United State_s,

620 F .2d 1277 (8th Cir.) (en banc),cert, denied, 449 U.S. 826

H?e recounted the procedural history of !̂?is ^ fixation in

?7loV !d ctV m

InitedS'tifes, 620 P.2d Till. 1281-1283 {6th Cir.), cert, denied.

449 U.S. 826 (1980).

14

✓

(1980),2 holding that the City Board and the State were jointly

responsible for maintaining a segregated school system. In

reaching this decision, we noted that the Missouri State Consti

tution had mandated separate schools for "white and colored

children" through 1976, that the State had not taken prompt and

effective steps to desegregate the city schools after Brown _v^

Bd. of Educ. , 347 U.S. 483 (1954) (Brown J.) , and that the City

Board’s policies and practices since 1956 had contributed to the

existing segregation. We remanded to the district court and

directed that the schools be promptly desegregated. We suggested

the following techniques:

(1) Developing and implementing compensatory

and remedial educational programs. * *

(2) Developing and implementing programs ̂

providing less than full-time integrated learning

exper iences.

(3) Developing and implementing a comprehen

sive program of exchanging and transferring

students with the suburban school districts of St.

Louis County. * * *

(4) Maintaining existing magnet and specialty

schools, and establishing such additional_schools

as needed to expand opportunities for an inte

grated education.

(5) Establishing an Educational Park.

(6) Continuing and expanding a policy of

permissive transfers in the district.

Adams v. United States, supra, 620 F .2d at 1296-1297 (citations

om i tted) .

2We also ruled

between L i d d e 11 I

557 (8th~C lT. 1977

on several procedural questions in the

and Adams, see Liddell v.— CaldweU.,

(Ltaaell II) .

inter im

553 F.2d

- 15 -

\

After holding extensive evidentiary hearings. the ^strict

court approved a system-wide desegregation P1" “ th* city

schools beginning with the 1980-81 school year. liais e • --a.

i : T d u c . 4,1 F. supp. 351 («.»• "O. m o , . This Plan included^

comprehensive program of exchanging and transfers

between the city and suburban schools, the establishme

magnet schools and integrative programs, and , guality educ, ion

component. In approving the plan, the district court conclu .

- %‘s!aa tothU s s- - instrumentalities must bean£ to other state

rejected!.]

Id. at 3^9.

we affrrmed the drsttict court's plan on appeal Liddell v ^

of Educ. 687 F . 2d 643 (8th Cir. 1981, ( L r d d e l l ^ , . ^

denied, ~454 O.S. 1081, 1091 (1982,. In so dorng, we deeded tha.

T T T T s constitutionally permissible to allow a number of all-

. t /-it-v We noted that no all-white black schools to remain in the city. _ .a , Dian of voluntary mterd istr ictcrhool s would remain, that a P-*-

transfers would be initiated, that magnet schools and int^ rat1^

Programs would be established, and that a substantial P - t of the

desegregation budget would be spent to improve the

education in the all-black schools. «e affirmed the S ate s

liability for desegregation costs and remanded for continued

implementation of the plan.

Questions about this plan's implementation came beforeus in

early 1982, when the State again protested its liability

certain desegregation costs. Liadgi--- --- ---------- — -

626 (8th Cir.) (Liddell V) . cerc_denied, 103 S. Ct.

16

(1982).3 We aff i rmed the district court's allocation of costs,

placing one-half of the actual desegregation costs on the

State. We also required the State to pay the costs of voluntary

interdistrict transfers and the costs of merging city and county

vocational educational programs. Meanwhile, the City Board an

the Liddell and Caldwell plaintiffs continued to seek the

consolidation of the city and county schools into a single

integrated school district on the theory that the suburban

schools had also violated the Constitution. They successfu y

moved to add the county school districts and St. Louis County

officials as defendants to this litigation. We noted that the

suburban schools could not be held as constitutional violators

Without further evidentiary hearings and findings by the district

cou-t. we again noted that the State and City Board-already

adjudged violators of the Constitution-could be required to fund

measures designed to eradicate the remaining vestiges of segre

gation in the city schools, including measures which evolved the

voluntary participation of the suburban schools. Liddell---,

supra, 677 P.2d at 641.

of

•̂ We issue

E d uc., 6 9 3

2 a procedural order in the interim. Liddell

F .2d 721 (8th Cir. 1981) (Liddell IV).

v . Bd.

*We suggested that

the district court could (1) require the state and

Jhe city to take additional steps to improve the

quality of the remaining a l l - b l a c k schools in the

o-.. If ct- Tonis* (2) require that additional

^gtynet0f.choolsOUi S'estibli.?ed at

within the citv or in suburban school districts

with the consent of the suburban districts where

iincentives for voluntary interdistrict transfe .

c-n v ">A at 641-642 (footnote omitted) Liddell V , supra, 677 F.2d at

17

dl5.rict court entered an order on August 6. 1982, which The drs.rrct co lt »ould impose in the

d isclosed the mandatory ,nterdrstrret plan it

.v- s,vjrbar school districts were found liaoie ro event the s . ^ _ ^ ^ would create one uni£led

tutional violation . f tax rate. The court

metropolitan school district with a uniform tax

then scheduled interdistrict liability hearings.

w forP these hearings were held, however, the City Board,

* .. S i tiffs, the Caldwell plaintiffs, and all twen y

the L l d d 6 .„ school districts developed a settlement agreement

three co-nkJ sc. COUrt-aPpointed expert and filed awith the assistance of a cour ppo ^

proposed Utr ict claims against the county

M ^ 3 d'c!icts, and also enabled the State and City Board toschoc. du.s-.icts, . c^hocls through the■ stepc to desegregate the city schools yta<e iir.ro. ts... step- , , as we outlined in

voluntary partreipatien of the county schools,

L i d d e i- V •

The settlement plan has several c o g e n t ̂

voluntary interd i.tr iot transfers between City aHr t o r ^ y ^ r ^ ^ t ^ r ^ I o e i v e s ^ n o o g h

transfers within five years to MtlSCy judgraent.

gat ions under the plan will rece* teacher transfers

Affirmative hiring requirements an vo a substantial

• » in **“ Pl;;oi;° " .ttr.et Whit, student transfers

impact rn the c o u n t y ' sc remedial programs for city

to the city, - a * ° J duional Ba9net schools in the city

students, the plan or COBpensatory and remedial

and the C°Un'yn'ents These latter components are designed to education components. schools, and to make

improve the quality of educat.on in the city

special improvements in the all-black schoo

fiiAri the settlement agreement, the after the parties filed tne , oa« a.nAfter ^ . ADril and May of 1983 todistrict court conducted hearings i P

4

1

18

determine whether the settlement plan is fair, reasonable, and

adequate. In its July 5, 1983, order, the court concluded the

plan met these standards and allocated the costs of the plan

between the State and City Board. Liddell v. Bd. of Educ.,

567 F. Supp. 1037 (E.D. Mo. 1983). The State is totally

responsible for the costs of the voluntary interdistrict

transfers, the magnet schools, and various part-time and

alternative integrative programs. Further, the State will pay

one-half of the cost of the quality improvements in the city

schools and one-half of the capital improvements required by the

plan. The City Board is required to pay the remaining costs.

The district court ordered the City Board to submit a bond

issue to its voters before February 1, 1984, to fund its share of

the capital improvements required under the plan. In the event

this bond issue failed to obtain the necessary two-thirds vote

the court reserved authority to consider an appropriate order to

fund these capital improvements. ̂ The district court also

deferred a scheduled reduction in the City Board's operating levy

otherwise required by Mo. Rev. Stat. § 164.013 (Proposition C)

insofar as this revenue is necessary to fund the City Board's

share of desegregation costs. It further reserved authority to

order an increase in the City Board's property tax rate, follow

ing notice and a hearing on the amount, if the revenue necessary

to fund the City Board's constitutional obligation to desegregate

the city schools is not otherwise available.

Several weeks after the district court entered its order

approving the settlement, the State filed a motion to stay the

implementation of the plan. The City of St. Louis filed a peti

tion for a writ of prohibition seeking the same result. The

district court denied both of these motions, and the State and * S

^The two-thirds majority is required by Mo. Const, art

S 26(b). This bond issue election was held on November 8,

and it failed, receiving fifty-five percent voter approval.

. VI

1983 r

t

19

Citv cf St. Lou i e appealed to our Court. In an en banc order,

Liddell v. Missouri, 717 F.2d 1180 (8th Cir. 1983) (Liddell V l ± ,

we denied the stay with certain exceptions. We froze the number

interdistrict transfers and deferred any further district

We

o: mtercistricr.

court action concerning the City Board's property tax rate

a 1 sc defer re: action on the writ of prohibition unti. we

considered t h - case on its merits

St

c -

Anneals were filed from the district court's July 5, 1983,

I: ?tate of Missouri, the City of St. Louis, the North

■_ ., 5 Parents and Citizens for Quality Education, and the

■ - - r- !!*■ ' ̂ - .

► oPjdc

ac

c

a p rrov

r c u i r i n

r the i r

the c- a

State t

order in:

city sc

increase

cost of

on appeal that the district court

additional interdistrict transfers of

e State to pay the full cost of the

,3rcfp,e; 1 2 in approving additional magnet schools

e integrative programs, and requiring the State to

il cost; (3' in approving certain programs to improve

1 1 y of education in the city schools, and requiring the

: pay one-half the cost of these programs; and (4) in

a deferral of scheduled property tax reduction for the

hoc 1s , and in stating that it would order a further

n property taxes to fund the City Board's share of the

e quality education programs in the city schools.

The City of St. Louis ;joins in questioning the authority o^

the district court to enter the taxing order referred to in (4)

above.

The St. Louis Teachers Union contends that the district

court erred in denying its motion to intervene.

The Northside Parents Organization contends that the

district court erred in failing to provide more extensive relief

20

to the black students who wou

schools.

Id remain in the nonintegrated

The United States did not file a notice of appeal or cross

appeal. It did file a brief and it was permitted to argue its

position before the Court en banc. It appears to argue that many

of the programs authorized by the district court may be necessary

to desegregate the city schools, but questions whether the

district court's factual findings are sufficient to support all

aspects of the district court's remedial order. It asks this

Court to remand to the district court to correct the alleged

deficiencies .

II. INTERDISTRICT TRANSFERS.

On July 2, 1981, the district court entered an order autho

rizing voluntary interdistrict transfers and requiring the State

to pay the cost of the transfers. The program was initiated at

the beginning of the 1981-82 school year, and by the end of the

1982-83 school year, it had grown so that 873 city students were

attending county schools and 318 county students were attending

city schools. All but seven of the 318 were enrolled in city

6We question whether the United States should be heard as a

D a r t v Parties who do not appeal from a trial court judgment

cannot be heard to attack that judgment, either to enlarge their

own rights, or to lessen the rights of their adversary. See

Morley Construction Co. v. Maryland Casualty— rrsTon--! oi pf 9 37) : United States v. American Railway Express—

265 D-S-I425 ' HfTWWegtMi*

5n?“ d' gfff o AW ins. _Co/. 586 r.*a n 7 (8th Cir

1978): Tiedeman v. Chicaqo, Milwaukee, St. Paul t Pac. R. *

513 P .2d 1267, 1271-1273 (8th Cir. 1975).

Here, the United States is requesting that the district

court’s order be vacated and that the case be remanded forfurther findings. This r e s u l t wuld "lessen the rights of toe

parties to the settlement agreement. In practical ter ,

however, we have considered the United States s position

amicus curiae.

21

magnet schools. The State of Missouri paid the cost of these

transfers, including transportation costs and fiscal incentives,

to the sending and receiving schools.

The settlement agreement calls for an expanded program of

interdistrict transfers. City-to-county transfers of black

students will be permitted to grow incrementally until they reach

15,000. No limit is placed on the county-to-city transfers, but

the number is not expected to exceed 3,000. These transfers are

expected to be primarily to city magnet schools and programs.

Transfers between county districts are also permitted. _ All

student transfers are voluntary.

The State's funding obligations remain as they were under

the July 2, 1981, order: It must pay transportation costs and

must pay to the receiving district for each transferring student

an amount equal to the receiving district's cost per pupil, less

State aid and trust fund allocation. It is further required to

provide fiscal incentives to sending districts which may elect

payment under one of two formulas: either one-half of the State

aid the district would have received had the student not trans

ferred; or, beginning in 1984-85, if a district sends more

students than it receives, State aid based on the district's

enrollment for the second prior year. To be eligible for

transfer, students of good standing must be in the racial

majority in their home districts and must transfer to districts

where they would be in the racial minority.

After approval of the settlement agreement, transfers rose

dramatically. During the current school year, 2,294 city

students have transferred to suburban districts and three hundred

and eighty-nine suburban students have transferred to city

schools. Thirty-four suburban students have transferred to other

suburban districts. One thousand nine-hundred and sixty-five

additional city-to-county transfer applications are on file.

22

The settlement agreement provides that participating

districts will receive a final judgment releasing them from

further liability if they achieve the plan ratio7 within five

years. Litigation is stayed during this period. If the school

district does not reach the plan ratio, litigation can be renewed

after first pursuing various negotiating procedures. If the

liability of any individual school district is litigated, the

plaintiffs must prove liability and may not seek reorganization

or consolidation of school districts, nor may they seek a

minority enrollment exceeding twenty-five percent of the school

distr ict.

The State argues that the district court order approving the

settlement agreement and requiring the State to pay the full cost

of interdistrict transfers cannot be sustained because it imposes

ar. interdistrict remedy based on an intradistrict violation. We

disagree for two reasons: First, the issue has previously been

decided adversely to the State; second, the interdistrict

transfers are intrinsic to an effective remedy for the intra

district violation and are justified by precedent.

^ THF. PROPRIETY OF THE DISTRICT COURT1S ORDER WITH

RESPECT TO INTERDISTRICT TRANSFERS HAS BEEN

PREVIOUSLY DECIDED.

This Court has repeatedly authorized the interdistrict

transfer of students as a fundamental element of an effective

7Under the Plan Ratio, * * * a suburban school

district would accept up to as many black transte

students as would constitute 15 percent of the

total student population in that district, bu no

suburban school district would be required to

accept more black transfer students than would

raise the overall percentage of blacks in the

total student population higher than 25 percent.

Settlement Agreement, 1-2.

23

remedy for the unconstitutional segregation of the city

schools. In Adams v. United States, supra, 620 F.2d at 1296, we

specifically approved the development and implementation of a

comprehensive program of exchanging and transferring students

with the suburban school districts of St. Louis County."

In Liddell III, supra, 667 F . 2d at 650 , we rejected the

State's argument that the district court was without authority to

formulate an interdistrict plan without finding an interdistrict

violation. We also noted that voluntary interdistrict pupil

exchanges "must be viewed as a valid part of the attempt to

fashion a workable remedy within the City." _Id_. at 651. In an

order appended to that opinion, we noted that the State had been

"judicially determined to be a primary constitutional violator,"

and we held that an interdistrict transfer plan would be salutary

and would be entirely enforceable against the State. .Id. at 659.

Finally, in Liddell V , supra, 677 F.2d at 630, we reiterated

our conclusion that, because the State had been found a primary

constitutional wrongdoer, it can "be required to take those

actions which will further the desegregation of the city schools

even if the actions required will occur outside the boundaries of

the city school district." After discussing broad-based inter

district proposals and dismissing them as unsuitable, we

addressed the proper limits of the district court's equitable

remedial authority:

[T]he district court can require the existing

defendants — the state and city school board— to

take the actions which will help eradicate the

remaining vestiges of the government-imposed

school segregation in the city schools, including

actions which may involve the voluntary partici

pation of the suburban schools. For example, the

district court could * * * (4) require the state

to provide additional incentives for voluntary

interdistrict transfer.

24

Id. at 641-642 (footnote omitted).

We did not act hastily or arbitrarily in approving voluntary

interdistrict transfers. We outlined the reasons for our deci

sion in Adams v. Dnlted States, supra. 620 F.2d at 1 2 9 1 - 1 2 9 7 . We

reviewed the parties' proposed remedial alternatives, aeveral of

which involved extensive cross-busing between city schools. The

Caldwell plaintiffs proposed a seventy-five percent black/twenty-

five percent white racial mix within the district. The Liddell

plaintiffs, through their expert witness, Dr. David Colton,

proposed a four-tier division of the schools by age groups, which

would integrate schools above fourth grade to achieve a sixty

percent/forty percent or fifty-five percent/forty-five percent

ratio of black to white students. All whites above third grade

would attend integrated schools and all blacks would receive at

least one-third of their education above third grade in

integrated schools. The Department of Justice, through its

expert witness, Dr. Gary Orfield, proposed maintenance and

expansion of integration in all grades, voluntary interdistrict

and intradistrict transfers, magnet schools, integration of

personnel, and community involvement. The Board of Education

proposed the creation of integrated junior high schools which

would funnel students to high schools in a balanced fashion.

Magnet schools would supplement these junior high schools,

white parents proposed that the schools be left as they were or,

alternatively, that the city and county schools be merged and a

comprehensive plan for interdistrict student transfers be

developed.

Of the four plans submitted by the parties, we found that

only the Colton and Orfield plans were constitutionally permis

sible. We rejected the City Board's plan as too little too later

elementary schools would remain entirely segregated and

desegregation of the upper tiers would be delayed four to seven

years. We rejected the Caldwell plan because the record

supported the district court's finding that implementation of the

- 25 -

i

plar. would probably result in an all-black school system within a

few years. We found that the Colton plan was permissible with

some substantial changes, but that plan was discarded by the

district court after it found that the plan was "educationally

unsound" and that it would "fail to achieve effective desegre

gation." ■ Liddell v. Bd. of Educ., supra, 491 F. Supp. at 356.

The approach suggested by the United State's expert, Dr.

Orfield, was ultimately adopted by the district court as the plan

that held "the promise of providing 'the greatest possible degree

of actual desegregation, taking into account the practicalities

of the situation.'" _I_d. at 359 , citing Davis v. Bd. of School

Comm1 r s , 402 U.S. 33 , 37 (1971). We reaffirmed our support of

the Orfield plan in Liddell III, supra, 667 F.2d at 649-653. We

noted that it was the only constitutionally permissible plan

submitted that could achieve stable, effective integration while

minimizing transportation of students and maintaining integrated

schools in integrated neighborhoods. _Id. at 650 .

The State defendants have raised the question of remedial

scope twice before the Supreme Court. On June 17, 1981, the

State filed a petition for certiorari from our panel opinion in

Liddell III. In that petition, the State argued that there was

no basis for State liability:

The evidence in this case indicates that the State

of Missouri took the necessary and appropriate

steps to remove the legal underpinnings of segre

gated schooling as well as affirmatively

prohibiting such discrimination.

State’s Petition for Certiorari, Ho. 80-2152, June 17, 1981, at

17.

It further argued:

26

The District Court exceeded its authority in

ordering the preparation of a plan of voluntary

pupil exchanges between the St. Louis School

District and nonparty school districts because (1)

an interdistrict violation has neither been

pleaded nor proven, and (2) the District Court

cannot, consistent with Milliken v. B radley, order

the State of Missouri to fund such a voluntary

plan simply on the basis of an intradistrict

violation.

Id. at 20.

The Supreme Court denied certiorari. Missouri— v_.— Lidde_U ,

4 54 U.S. 1091 (1981) .

Not satisfied with this answer, the State raised the same

arguments again before our Court in Liddell IV. and Liddell _V.

Unsuccessful in our Court, the State filed a second petition for

certiorari with the Supreme Court on April 30, 1982. The State

again argued that

ordering an inter-district remedy [the .12(a)

voluntary transfers, funded by the State] without

first finding an inter-district violation and

inter-district effect is in conflict with this

court's decision in Milliken v. Bradley— I. [an

Hills v. Gautreaux].

State's Petition for Certiorari, No. 81-2022, April 30, 1982, a.

7; see also id. at 10.

Again, the Supreme Court denied certiorari. Missouri._v. Liddell

103 S. Ct. 172 (1982). Both of the State's petitions for certio

rari came after the Supreme Court's decision in Hills_ v

Gautreaux, 425 U.S. 284 (1976).®

®A1though denial of certiorari does not necessarily imply

tB§rtIaled°)f the decisi°n b6lOW °n the KieritS'' h U

27

As a result of our previous holdings and of the Supreme

Court's inaction, the use of interdistrict transfers is settled

as law of the case. While this doctrine does not foreclose is

Court from correcting its errors, it prevents repeated litigation

of the same issue and promotes uniformity of decision IiL_JL

Sidino and Alum inum. Coil Antitrust Litigation.

613 616 (8th Cir. 1982), vacated en banc, 705 F.2d 980 (8th Cir.

1963), cert, denied, 104 S. Ct. 204 (1983). We will reconsider a

previously decided" issue only on a showing of clear error an

manifest injustice. United States v (In ^ , 700 F.2d 445, 45

n 10 (8th Cir.), cert, denied, 104 S. Ct. 339 (1983)! W r t p -

v. S*nnders Archery Co,. 578 F .2d 727. 730-731 (8th

Cir. 1976).

K. are loath to retract our previous declarations on settled

issuer when a case returns on appeal) to do so ignores important

considerations of judicial economy and ignores our interest in

protecting the settled expectations of parties who have conformed

the ir" conduct to our guidelines. In this case, our conclusion

that State-funded interdistrict transfers are an appropriate

remedy is strengthened by our previous invocation of the law o

the case doctrine. Liddell V. s u e t s , 677 F.2d at 629-630.

The State argues that we should not be bound by our earlier-

decisions because the magnitude of the proposed plan with

respect both to cost and numbers of students, distinguishes it

from existing plans. Neither this Court nor the district court

placed any limitation on the number of students that could

transfer under the plan in existence during the last two sch

years, nor were we requested to do so. Moreover, it w.. clear

that the number of transfers would have to be large if

recognized that denial of certiorari- ^Ls,^ yndewen s y,

circumstances, a _,£"c£ “h ‘f?68 Ca3£74-1275 (8th Cir. 1977). See Meyer's Bahery., 561 F.2d 1268 , 1274^12 ̂ 443 (1973). united

also United States v K.as, 4 9 U.S. cir.,, cert, denied,

States v. Thompson, 685 F.za v

T o 3 S. Ct. 494 (1982).

28

opportunity for an integrated education was to be provided to a

significant number of the 30,000 black students that remained in

the all-black schools in the city.

Notwithstanding our view that the issues regarding inter

district -transfers have been heretofore decided, we again reach

the merits of the matter and, alternatively, hold that the plan

and the funding order, as they relate to interdistrict transfers,

meet constitutional standards.

B. THE DISTRICT COURT’S ORDER WITH RESPECT TO

INTERDISTRICT TRANSFERS MEETS CONSTITUTIONAL

STANDARDS.

Since Brown v. Bd. of Educ., 349 U.S. 294, 300 (1955) (Brown

II', principles of equity have guided courts in devising remedies

to eradicate segregation and its effects. Yet for equitable

remedies to pass constitutional muster, they must conform to

three overlapping criteria.

[First] , the nature of the desegregation remedy is

to be determined by the nature and scope of the

constitutional violation. * * * The remedy must

therefore be related to "the condition alleged to

offend the Constitution." * * * Second, the decree

must indeed be remed i al in nature, that is, it

must be designed as nearly as possible "to restore

the victims of discriminatory conduct to the posi

tion they would have occupied in the absence of

such conduct." * * * Third, the federal courts

* * * must take into account the interests of

state and local authorities in managing their own

affairs, consistent with the Constitution.

Milliken v. Bradley, 433 U.S. 267, 280-281 (1977) (Milliken II)

(citations and footnotes omitted).

Examination of voluntary interdistrict transfers confirms that,

as a remedy for an intradistrict violation, such transfers comply

29

wit.n constitutions! stsndsrds*

1. The remedy was c l o s e l y tailo red to the nature

and scope of the violation.

The Missouri Constitution requires the State to provide a

free public education. Mo. Const, art. 9, § 1 ( a ) - The State

supervises instruction, distributes funds for public education to

local school districts, approves school bus routes, provides free

textbooks, and passes on applications by school districts for

federal aid. See Mo. Rev. Stat. SS 1 6 1 . 0 9 2 , 1 6 3 . 0 2 1 , 1 6 3 . 0 3 1 ,

163.161, 170.051, 170.055; and Liddell v. Bd. of Educ^, supra,

469 F. Sapp, at 1313-1314.

Before the Civil War, Missouri prohibited the creation of

school* to teach reading and writing to blacks. Act of

February 16, 1847, S 1, 1847 Mo. Laws 103. State-mandated segre

gation was first imposed in the 1865 Constitution, Article IX

§ 2. It was reincorporated in the Missouri Constitution of

1945: Article IX specifically provided that separate schools

were to be maintained for "white and colored children." In

1952, the Missouri Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of

Article IX under the United States Constitution. See State _ex

re 1. Hobby v. Disman, 250 S.W.2d 137, 141 (Mo. 1952). Article IX

was not repealed until 1976 . Adams v. United States., .supra, 620

F.2d at 128C. Under the segregated system, the State bused

suburban black students from St. Louis County into the city’s

black schools to maintain the dual system. IdL, at 1281. The

city schools remained largely segregated until this Court’s deci

sion in Adams. 5

5In addition, state law provided separate libraries, public

"institutes for colored teachers," Mo. Rev. Stat. 10632 (1939).

30

It is clear from the foregoing that the State's presence in

public education is immense and that the State’s Constitution and

statutes mandated discrimination against black St. Louis students

on the broadest possible basis. It is equally clear that the

discriminatory policies continued after the Supreme Court decided

Brown I, supra, in 1954. Given the breadth of the State's

violation, it was appropriate for the district court to mandate

an equally comprehensive remedy. The potential for integration

within the district, however, was limited by the fact that almost

eighty percent of the students were black, and by the district

court’s finding that if it integrated the city schools by impos

ing an eighty/twenty ratio in each school, an all-black school

system would probably result. With that in mind, the district

court properly considered the alternative of voluntary transfers

to county districts. The opportunity for effective integration

became a reality when the county schools agreed to accept the

voluntary transfer of several thousand black students.

2 . The remedy restores the victims of discrimi

nation as nearly as possible to the position they

would have ocoupied absent that discrimination.

We have heretofore enumerated the alternative remedies

suggested by the parties, and we have explained why the district

court selected a remedy which included voluntary interdistrict

transfers and why this Court approved that remedy. (See supra

pp. 25-26.)

of

10We also note that the remedial limits imposed by Dayton Bd^

Educ. v. B rinkman, 433 D.S. 406 (1977), are inapposite to this

case^ The findings“”of de jure segregation which distinguish this

case were absent in Dayton. In that case, the Supreme Court

considered the proper scope of an equitable remedy for three

isolated instances of discrimination.

31

We are met for the first time on this appeal with a new, or

at least a more precisely framed, argument against interdistrict

transfers. The State asserts that the district court cannot

require the State to fund extensive interdistrict transfers

unless the record supports and the district court finds that the

black children of St. Louis would have attended schools in the

county had it not been for the State's constitutional prohibition

against black and white students attending schools together.

Nothing in the cases cited by the State12 suggests or requires us

to hold that the district court abused its discretion when it

required the State to fund interdistrict transfers of students to

consenting districts. Indeed Milliken II states that the remedy

shojld correct conditions that "flow from such a violation an^

11The United States joins in this argument. In earlier

proceedings before this Court and the United States Supreme

Court, however, it supported the district court's remedial use o^

voluntary interdistrict transfers. It argued that voluntary

interdistrict transfers properly remedied the State s violation,

distinguishing them from the overbroad remedy in Milliken I,

which involved "imposition of relief upon nonparty school

districts." It asserted that the district court can order those

who have been found liable to make efforts to persuade those

nonparty districts to cooperate voluntarily." U. S. Brief in

Opposition to State's Petition for Certiorari, Missouri--Vjl.

Liddell, No. 80-2152, Aug. 17, 1971, at 14 (emphasis in

original) .

In a subsequent brief, the United States again distinguished

the interdistrict transfers from the impermissible interdistrict

remedv in Milliken I. Moreover, in endorsing interdistrict

transfers, it stated “that, under Hills, "the State parties can

and should be required to take appropriate remedial action for

the constitutional violations in which they participated. U. S.

Brief in Opposition to the State's Petition for Certiorari,

Missouri v. Liddell, No. 81-2022, April 30, 1982, at 7,8.

12Dayton Bd. o f Educ. v. Brinkman, 443 U.S. 526 (1979) (Dayton

II); Columbus Bd. of Educ. v. Penick, 443 U.S. 449 U9J9)? Schoq^

PTstrTct of Omaha v. United States, 433 U.S. 667 (1977); Dayton

Bd. of Educ. v. Brinkman, 433 U.S. 406 (1977); H*11* * ^ —

Brad ley r~ro~uTST~?57~TTyn) (Milliken II) ; Pasadena Cit y. Bd^of

Educ; v. Spangler, 427 U.S. 424 (1976); Washington v. Davis,

T26- U.S. 529 (197$) ; Keyes v. School Dist. No. T, 4l3 U.S. 189

(1973); Swann v. Char lot te-Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ^, 402 U.S. 1

(1971).

32

should return victims "to the position they would have enjoyed in

terms of education," but for the violation. Milliken 11, su£ra,

433 U.S. at 282 . This remedy does precisely that: It returns

the largest number of victims to integrated schools and provides

integrative opportunities and compensatory and remedial programs

for those who cannot participate in the transfer plan. As the

primary constitutional violator, the State is in no position to

complain that some of the victims may elect to transfer to

integrated schools in another school district that is willing to

accept them.

In our view, Hills v. Gautreaux provides precedent for the

remedy mandated by the district court. In that case, the Supreme

Court considered a remedy against the United States Department of

Housing and Urban Development (HUD) for discrimination in public

housing in the City of Chicago. The United States Court of

Appeals for the Seventh Circuit had reversed the district court's

dismissal and ordered the district court on remand to enter

summary judgment against HUD for violations of the Fifth Amend

ment and the Civil Rights Act of 1964 by knowingly sanctioning

and assisting the Chicago Housing Authority's (CHA) racially

discriminatory public housing program. Hills v. Gautreaux,

supra, 425 U.S. at 291-292. Thereafter, the plaintiffs requested

that the district court require HUD to provide public housing

outside Chicago's city limits. The district court refused,

holding that the wrongs were committed solely against city

residents and within the city's boundaries.

On appeal, the Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit

reversed and the Supreme Court affirmed. The Supreme Court

stated:

We reject the contention that, since HUD s

constitutional and statutory violations vere

committed in Chicago, Hilllke_n precludes an order

against HUD that will affect its conduct in the

greater metropolitan area. The cr 1*1C®1

tion between HUD and the suburban school distric

33

in Milliken is that HUD has been found to have

violated the Constitution*. That violation

provided the necessary predicate for the entry of

a remedial order against HUD and, indeed, imposed

a duty on the District Court to grant appropriate

relief. * * * Our prior decisions counsel that in

the event of a constitutional violation "all

reasonable methods be available to formulate an

effective remedy," North Carolina State Board of

Education v. Swann, 402 U.S. 43 , 46 , and that

every effort should be made by a federal court to

employ those methods "to achieve the greatest

possible degree of [relief], taking into account

the practicalities of the situation." Davis v.

School Comm* 1rs of Mobile County, 402 U.S. 33,

37. As the Court observed in Swann v. Charlotte-

Mecklenburg Board of Education: "Once a right and

“a violation have been shown, the scope of a

district court's equitable powers to remedy past

wrongs is broad, for breadth and flexibility are

inherent in equitable remedies."

Hills v. Gautreaux, supra, 425 U.S. at 297 (emphasis added;

citations omitted).

The Supreme Court then discussed Milliken v. Bradley,

416 U.S. 717 (1974) (Milliken I) , and the limitation it imposed

or. the scope of the federal courts' equity powers. In Milliken

I, the respondents alleged that the Detroit school system was

racially segregated and they sought the creation of a unified

school district as a remedy. Without finding constitutional

violations by the suburban districts and without finding signif

icant segregative effects in those districts, the district court

ordered the consolidation of the Detroit school system with

fifty—three independent suburban school districts. After the

Court of Appeals for #the Sixth Circuit affirmed this desegre

gation order, the Supreme Court reversed, holding that the order

exceeded the district court's equitable powers: the courts must

tailor "the scope of the remedy" to fit "the nature and extent of

the constitutional violation." Id. at 744.

34

In evaluating the remedy in Hills according to Milliken I 's

standards, the Supreme Court noted that nothing in Mi 11 iken_I_

•suggests a per se rule that the federal courts lack authority to

order parties found to have violated the Constitution to

undertake remedial efforts beyond the municipal boundaries of the

city where the violation occurred." Hills v. Gautreaux, 8upra,

425 U.S. at 298 (footnote omitted). In Hills, the Supreme Court

approved the remedy • because it did not coerce uninvolved

governmental units and because CHA and HUD had the authority to

operate outside Chicago's city limits. Id.

Justification for requiring the State to fund transfers

between city and county schools is stronger than the justifi

cation for the remedy in Hills. Its role in education is much

broader than HUD's role in housing. See supra p. 30. In

addition, the breadth, gravity and duration of the State's viola

tion here was much greater. The violation scarred every student

in St. Louis for over five generations and it gained legitimacy

through the State Constitution and through the State's preeminent

role in education. In following the Supreme Court's guidelines

in Hills, we echo its conclusion concerning Milllken I. If we

barred the use of interdistrict transfers solely because the

State's constitutional limitation took place within the city

limits of St. Louis, we would transform

Milliken [I]'s principled limitation on the exer

cise of federal judicial authority into an

arbitrary and mechanical shield for those found to

have engaged in unconstitutional conduct.

Hills v. Gautreaux, supra, 425 U.S. at 300.

3. The d i s t r i c t c o u rt ' s order with respect to

i n t e r d i s t r i c t transfers does not infringe on State

or l o ca l government autonomy.

35

The Supreme Court in Hills v. Gautreaux, supra, 425 U.S. at

296, has interpreted Milliken I to mean that district courts may

not restructure or coerce local governments or their subdivi

sions. This remedy does not threaten the autonomy of local

school districts; no district will be coerced or reorganized and

all districts retain the rights and powers accorded them by state

and federal laws. See Hills v. Gautreaux, supra , 425 U.S. at

305-306.

We also find unpersuasive the State's argument that funding

this remedy will compel other budget cuts, which would interfere

with the autonomy of state and local governments. If we accepted

this argument, violators of the Constitution could avoid their

remedial responsibility through manipulation of their budgets,

leaving victims without redress. Simply put, parsimony is no

barrier to a constitutional remedy; "it is obvious that vindica

tion of conceded constitutional rights cannot be made dependent

upon any theory that it is less expensive to deny than to afford

them..'’ Watson v. Memphis, 373 U.S. 526, 537 (1963)

Interdistrict transfers between the city and the county

schools may proceed pursuant to the settlement agreement, subject

to the following exceptions:

(1) No additional transfers will be permitted for the

̂̂ The district court's funding order poses no eleventh

amendment problems. The State relies on Edelman v. Jordan, 415

U.S. 651 , 663 (1974 ), to avoid its liability for a remedy that

requires the expenditure of state funds where that remedy is

allegedly overbroad. The Supreme Court in Milliken II applied

the prospective compliance exception developed in Ex Parte Young,

209 U.S. 123 (1908), which "permits federal courts to enjoin

state officials to conform their conduct to requirements of

federal law, notwithstanding a direct and substantial impact on

the state treasury." Milliken II, supra, 433 U.S. at 289- After

elucidating the three criteria discussed earlier, the Supreme

Court in Milliken II found that the plan under review there was

constitutional. The interdistrict transfer plan under

consideration in this case conforms to the same three criteria.

36

balance of the current school year. Such transfers would

disrupt the education of students in both sending and

receiving schools. Planning and recruitment may continue so

that enrollment may reach the levels contemplated in the

settlement agreement.

(2) C i t y-to-county transfers will be limited to a total of

6,000 students in the 1984-85 school year and to not more

than 3,000 additional total transfers in each succeeding

school year until the limit of 15,000 is reached., A

shortfall of enrollment in one year may be made up in

succeeding years.

(3) In the event

exceeds the spaces

applicants who would

the number of applicants for transfer

available, priority shall be given to

otherwise attend an all-black school.

(4) In Liddell V , supra, 677 F.2d at 631-632, we warned of

the need for vigilance to control the costs of

desegregation. Budgetary constraints persist, and so does

the need for frugality. We are unwilling, however, to accept

the State's suggestion that "complementary zones" be estab

lished, which would effectively limit schools that

transferees could attend. This would destroy the voluntary

nature of the plan. Nevertheless, constant effort and

careful planning must be made by all concerned to limit the

costs of transportation, insofar as is consistent with the

Constitution and the voluntary nature of the plan.

C. COUNTY TO COUNTY

Although

between the

approval to

d istr icts.

between the

TRANSFERS.

funding of transfers of students

are unable to give similar

of students between county

the objective of transfers

eradication of segregation

we approve State

city and county, we

the funding of transfers

We emphasize again that

city and county is the

37

within the

violation

violat ion,

which were

however, ar

city. -Nor

will materi

city. Such transfers are closely tailored to the

and are clearly remedial with respect to that

according to the standards announced in Milliken_I_I_

discussed above. Transfers between county districts,

e not geared to remedy the violation found within the

does the record establish that intercounty transfers

ally assist in desegregating the city schools.

We recognize that some suburban school districts have

majority black enrollments and others have nearly all-white

enrollments. We acknowledge that the suburban districts would

achieve a further degree of desegregation by such transfers. We

neither prohibit nor discourage such voluntary transfers between

county schools but we cannot compel the State to pay for them

absent a finding of an interdistrict violation.

HI. magnet schools and integrative programs.

A. MAGNET SCHOOLS .

The district court and this Court previously authorized the

creation of magnet schools and integrative programs. About 8,000

students (one-half of whom were blacks) participated in these

schools and programs in the 1982-83 school year. Three hundred

participants resided in the county. No one suggests that the

magnet schools or integrative programs be discontinued.

The settlement agreement approved by the district court

provides for the expansion or replication of existing magnet

schools and programs and the development of new magnet schools

and programs — in both the city and the county with total enroll

ment to reach 20,000 students, twelve to fourteen thousand to be

enrolled in city magnets and the balance in county magnets. The

new schools would be phased in over the 1983-87 period.

To be eligible for transfer to the magnet schools, students

38

in good standing must be in the racial majority in their home

districts and must meet the qualifications for the magnets.

Special eligibility requirements allow white students from the

city to attend city magnets if the students now attend schools

that are less than ten percent or over fifty percent white.

Black students in majority black districts are eligible to attend

magnet schools and programs in other black majority districts if

seats remain open after all of the host district's black students

have been accommodated.

The State argues that insufficient attention has been

devoted to developing a curriculum designed to attract county

students. It also objects to being required to pay the full cost

of building and operating the new magnets.

Before reviewing the State’s specific arguments, we observe

that the utility and propriety of magnets as a desegregation

remedy is beyond dispute. In Adams v.__United— States , ..supra,

620 F . 2d at 1296-1297, we evaluated the remedies we had

previously found to be constitutionally permissible. We

recommended ■[ra]aintaining existing magnet and specialty schools,

and establishing such additional schools as needed to expand

opportunities for an integrated education." JLL. at 1297. We

reiterated our approval of magnet schools in Liddell III., su£ra_,

667 F . 2d at 658 (emphasis omitted), where, in considering an

intradistrict remedy, we directed the city and suburban school

districts to undertake a "study of the feasibility of establish

ing magnet schools located in suburban districts with attendance

open to students of both the suburbs and the city. * The

14Our affirmance in this case does not preclude the district

court from reconsidering these special requirements--to the

extent that they permit a white student attending a "***}

less than ten percent white enrollment to transfer to a ci y

magnet school— in light of decisions by the Supreme Court and

this Court. The district court may reconsider these requirements

upon the request of any party.

39

msuBast R r

location of these magnet schools should be determined by

agreement between the St. Louis Board of Education and the

suburban school districts involved." Finally, in Liddell V,

supra, 677 F.2d at 642, we reaffirmed our conclusion that the

district .court could "require that additional magnet schools be

established at state expense within the city or in suburban