Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals Orders End of Discrimination in Shaw, Miss.

Press Release

January 29, 1971

Cite this item

-

Press Releases, Volume 6. Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals Orders End of Discrimination in Shaw, Miss., 1971. 01a1935e-ba92-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/72300069-9137-4d13-bc1a-721975023951/fifth-circuit-court-of-appeals-orders-end-of-discrimination-in-shaw-miss. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

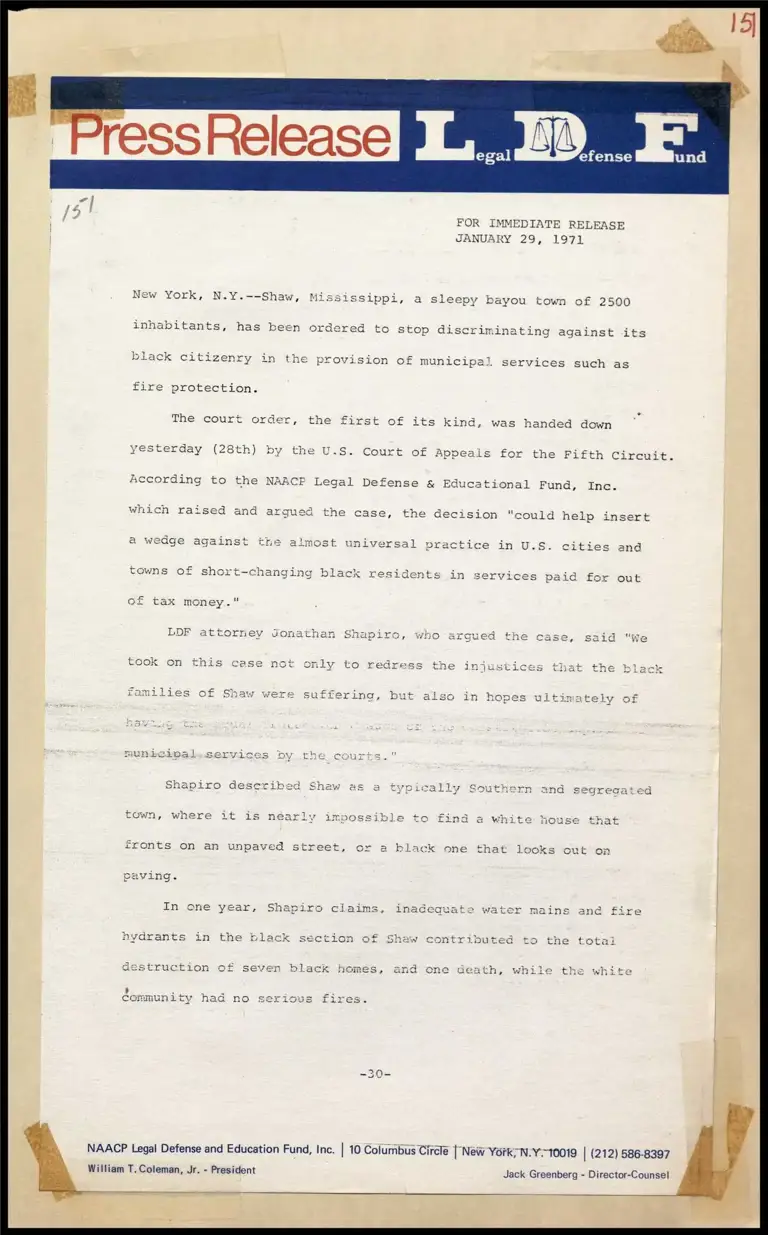

ressRelease ft ime (am

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

JANUARY 29, 1971

New York, N.Y.--Shaw, Mississippi, a sleepy bayou town of 2500

inhabitants, has been ordered to stop discriminating against its

black citizenry ovision of municipal services such as

fire protection.

The court order, the first of its kind, was handed down

yesterday (28th) by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit.

According to the NAACP Legal Defense & Educational Fund, Inc.

which raised and argued the case, the decision “could help insert

a wedge against almost universal practice in U.S. cities and

towns of short-changing black residents in services paid for out

of tax money."

LDF attorney Jor

took on this case not

nilies of Shaw were

servic

Sha and segreaated

town, where it is néa: civ 2Ossible house that

fronts on an unpaved street, or a black one that looks out on

Shapiro claims, inadeq

ruction of seven black homes, and one death,

’ : =

community had

NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund, Inc. | 10 Columbus Circle [ NeW York; N.Y>10019 | (212) 586-8397

William T. Coleman, Jr. - President Jack Greenberg - Director-Counsel

und