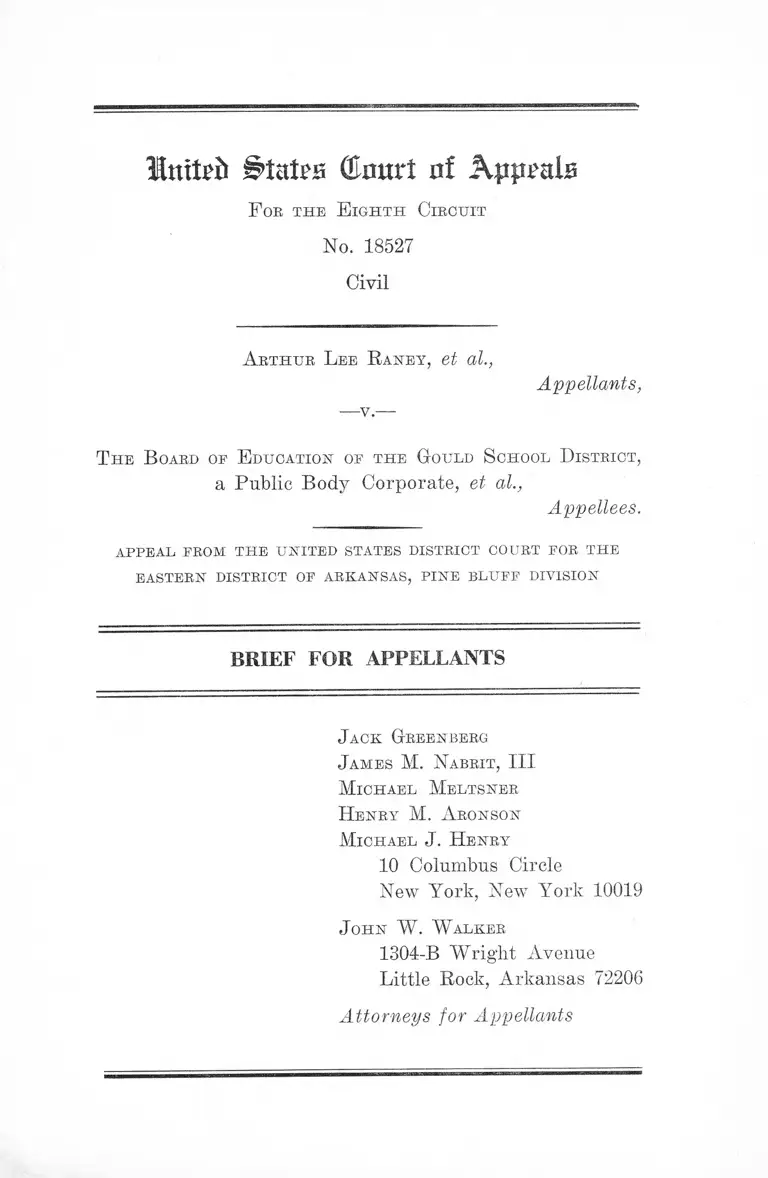

Raney v. Board of Education of The Gould School District Brief for Appellants

Public Court Documents

October 2, 1967

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Raney v. Board of Education of The Gould School District Brief for Appellants, 1967. 059d58d0-c19a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/724a3d1f-abee-4395-b03a-a8698ed0b178/raney-v-board-of-education-of-the-gould-school-district-brief-for-appellants. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

Intteft States (Unurt of Appeals

F oe, t h e E ig h t h C ircu it

No. 18527

Civil

Aethttr, L ee R a n e y , et al.,

Appellants,

T h e B oard of E ducation of th e G ould S chool D istrict ,

a Public Body Corporate, et al.,

Appellees.

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE

EASTERN DISTRICT OF ARKANSAS, PINE BLUFF DIVISION

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

J ack G reenberg

J am es M. N abrit , III

M ic h ael M eltsner

H en ry M. A ronson

M ic h ael J . H en ry

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

J o h n W . W alker

1304-B Wright Avenue

Little Rock, Arkansas 72206

Attorneys for Appellants

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PAGE

Statement of the Case .................................................... 1

Unequal Facilities .................................................... 3

Unequal Programs .................................................... 5

Teacher Segregation .......... 6

Intimidation ................................................................ 7

New Construction to Perpetuate Segregation....... 8

Denial of Relief by the Court B elow ...................... 10

Statement of Points to Be Argued ............................. 11

A bg u m en t—

I. This Court Should Consolidate the Dual School

System in Gould so that All Elementary Stu

dents Attend the Field Site and All High School

Students Attend the Gould Site, Under the Prin

ciples of Kelley v. Altheimer ............................. 13

The Remedy..........................................-............. 18

II. Appellants Are Entitled at the Very Least to a

Comprehensive Decree Governing the Desegre

gation Process Under Kelley v. Altheimer ....... 23

C onclusion 28

IX

A ppen d ix—

PAGE

Affidavit on the Status of the New School Con

struction in the Gould School District (April

28, 1967) .................................................................. la

A Summary of the Testimony of Plaintiff’s Ed

ucational Expert in Kelley v. The Altheimer,

Arkansas Public School District No. 22 et al.

on the Inefficiency of a Dual School System of

Small Schools ........................................................ 3a

The Decree of the Court of Appeals for the Eighth

Circuit in Kelley v. The Altheimer, Arkansas

Public School District No. 22 et al., No. 18,528,

April 12, 1967 ........................................................ 7a

T able op Cases

Board of Education of the Oklahoma City Public

Schools v. Dowell, 10th Cir., No. 8523, January

23, 1967 ................................................................... 22, 24, 25

Board of Public Instruction of Duval County, Pla. v.

Braxton, 326 F.2d 616 (5th Cir. 1964) ...................... 15

Bradley v. School Board of the City of Richmond, 382

U.S. 103 (1965) ............................................................ 25

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954) .... 21

Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U.S. 294 (1955) .... 25

Chambers v. Hendersonville City Board of Education,

364 F.2d 189 (4th Cir. 1966) ..................................... 25

Clark v. Board of Education of Little Rock School Dist.,

369 F.2d 661 (8th Cir. 1966) ..................................... 26

Dowell v. School Board of Oklahoma City, 244 F. Supp.

971 (W.D. Okla. 1965) 22

I l l

PAGE

Kelley v. The Altheimer Arkansas Public School Dis

trict No. 22, 8th Cir., No. 18,528, April 21, 1967 ....13-17,

22, 23-28, 7a-lla

Kemp v. Beasley, 352 F.2d 14 (8th Cir. 1965) .......16,25

McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents, 339 U.S. 637

(1950) ................................................................-..........21>27

Missouri ex rel. dailies v. Canada, 30o U.S. 337

(1938) ....................... -...................................................21>27

Rogers v. Paul, 382 U.S. 198 (1965) ............................. 25

Smith v. Board of Education of Morrilton School

Dist. No. 32, 365 F.2d 770 (8th Cir. 1966) .................. 26

Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U.S. 629 (1950) ....~..............-21, 27

United States v. Jefferson County Board of Education,

5th Cir., Civil No. 23345, December 29, 1966; reaf

firmed en banc, March 29, 1967 .................. -...... 22, 24, 25

Wheeler v. Durham City Board of Education, 346 F.2d

768 (4th Cir. 1965) ..................-........................ -...........

Wheeler v. Durham City Board of Education, 363 F.2d

738 (4th Cir. 1966) ..................................................... -

Wright v. County School Board of Greensville County,

Va., 252 F. Supp. 378 (E.D. Va. 1966) ........... -.......- 15

Imtpfc BtnUa (totrt nt Kppttda

F oe t h e E ig h t h C ircuit

No. 18527

Civil

A et h e r L ee R an ey , et al.,

Appellants,

T h e B oaed of E ducation of th e G ould S chool D isteict ,

a Public Body Corporate, et al.,

Appellees.

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

Statement of the Case

This case originally involved a class action suit by

Negro students filed September 7, 1965, against the

Gould Special School District of the State of Arkansas

to enjoin said district, inter alia, from (1) requiring

them and all others similarly situated to attend the all-

Negro Field School, (2) providing public school facilities

for Negro pupils which are inferior to those provided

for white pupils, and (3) otherwise operating a racially

segregated school system (R. 3-8). Plaintiffs first learned

of a proposed construction program during the hearing-

on the complaint in November 1965 and an amendment

at that time was accepted by the trial court seeking to

require that any future replacement high school facilities

in the Gould school system be located on the premises

2

of the white Gould High School, rather than on the

premises of the Negro Field School (R. 12, 138).

The Gould school system is a school district of very

small population, having a total enrollment of 879 in

the 1965-66 school year (R. 79-80). Until September,

1965 the district had not taken any steps to comply with

Brown v. Board of Education—the district operated com

pletely separate schools for Negro and for white pupils

(R. 31). Negro students were instructed in a complex

of buildings known as the Field School, and white students

were taught in a complex of buildings known as the Gould

School (R. 31). The sites of the two building complexes

are within 8 to 10 blocks of each other (R. 73). Each

site contains an elementary school and a secondary school

(R. 31). Also up until September, 1965, the faculty was

completely segregated, with white students taught only

by white teachers and Negro students taught only by

Negro teachers (R. 31).

The school district did not consider undertaking any

program of desegregation until compelled to do so under

the Guidelines of the United States Department of Health,

Education, and Welfare implementing Title VI of the

Civil Rights Act of 1964 (R. 121-122). In September of

1965, the district adopted a “freedom of choice” plan of

desegregation for all 12 grades. This plan was later

amended to withdraw three grades from the plan for

the 1965-66 school year (R. 53-60, 62-63). During the

fall of 1965, the enrollment figures for the school district

were as follows: 509 Negro students in the all-Negro

Field School, and 71 Negro students and 299 white stu

dents in the previously all-white Gould School (R. 79-80).

There were no white students attending the all-Negro

Field School (R. 79-80).

3

Unequal Facilities

The present condition and the past condition since 1954

of the all-Negro Field High School was admitted by

W. C. Sheppard, Jr., President of the Board of Edu

cation, to have been “grossly inferior” to the white high

school (R. 130). It is an old wooden frame structure

erected in 1924 (R. 10, 16). He said that the reason that

no money had been spent on the Negro high school facility

since 1954 was that every dollar available had been ex

hausted on other uses (R. 130). Nevertheless, a com

pletely new high school had been constructed at the white

Gould site in 1964 following a fire which destroyed the

old high school building there (R. 83).

As of September, 1965, the Negro Field High School

was completely unaccredited, and the Field Elementary

School had class “C” rating from the Arkansas State

Department of Education (R. 31). By contrast, the

predominantly white Gould Schools had ratings of “A”

from the State of Arkansas (R. 10).

The bathroom facilities at the Negro Field High School

are located in a separate building, which requires stu

dents to walk outside to reach them in all kinds of weather

(R. 50-52). Similarly the gymnasium facilities for the

use of Negro high school students are located about four

blocks away on the premises of the Negro elementary

school (R. 32). Conversely, the predominantly white

Gould High School and Elementary School each have rest

room facilities within each building, which facilities are

kept in good repair and are adequate (R. 50-52).

There is an agriculture building at the predominantly

white Gould High School, but there is none at the Negro

Field High School (R. 40-41). There is a hot lunch pro

4

gram for both elementary and secondary students at the

predominantly white site, hut there is none at the Negro

site and there never has been one (R. 40). The section

of the Negro high school which is used as an auditorium

is inadequate for that purpose in capacity and facilities,

whereas there is a room designed as an auditorium at

the white high school (R. 41).

There is a library in the white high school which con

tains approximately 1,000 books, and there is an actual

librarian who has several periods of the day set aside

for library duties (R. 42-43). Conversely, there is no

library at the Negro school. The school does have three

sets of encyclopedias, one of which was purchased just

one month before the hearing in this case (R. 113-114).

These books are kept in the office of the principal of the

school rather than in a separate library, and the prin

cipal of the school, in effect, functions as librarian, to

the extent that any such functions are required with such

a minimal number of books (R. 114). Even these books

were purchased with private contributions rather than

funds supplied by the school board (R. 114). The record

shows that the superintendent had a complete lack of

knowledge of the extent, or lack of same, of the library

facilities at the Negro School (R. 42-43).

The science facilities at the Negro high school were

admitted by the superintendent to be inferior to those

of the predominantly white high school, even though the

former is the larger school (R. 43-44). Pupils who attend

the predominantly white Gould High School generally

have an individual desk and chair, whereas the standard

pattern at the Negro Field High School is that there is

a folding table with folding chairs and three on each

side, sitting at the table (R. 47-48).

5

Unequal Programs

The various specific inequalities are reflected in the

fact that the “per pupil” expenditure by the school system

is less for the all-Negro Field High School than it is for

the formerly all-white and now predominantly white Gould

High School (R. 44). Even this disparity does not fully

reflect the actual disparity in the situation because of

the school system’s past practice of charging enrollment

fees to pupils at Field High School, but not at the Gould

High School (R. 44-45). It was also the practice of the

school system in the past to require Negro students to

pick cotton in the fields during class time and after hours

for school fund raising projects, and to pay the enroll

ment fees (R. 44-46). For instance, even a portion of

the rather small number of books at the Field School

were purchased through fund-raising efforts by the stu

dents rather than with funds supplied by the Board of

Education (R. 105-106).

The unequal per pupil expenditures of the school sys

tem are also reflected in the fact that the student-teacher

ratio is higher at the Negro school than at the predom

inantly white school, i.e., the average class size is larger

at the former than at the latter (R. 59-62). There are

14 teachers for 365 students at the predominantly white

Gould School, but only 16 teachers for 478 students at

the all-Negro Field School (R. 60-61). This disparity is

similarly reflected in inequality of salaries for Negro and

white teachers. The range of Negro teacher salaries is

from $3,870 to $4,500, whereas for white teachers, the range

is from $4,050 to $5,580 (R. 33-39).

There are also disparities in course offerings at the

two high schools. For instance, neither vocational agri

culture nor journalism, which are offered at the predom

6

inantly white school, are offered at the all-Negro school,

although the latter is the larger of the two (E. 52-53).

There is a similar disparity in the offering of extra

curricular activities. Again, although the Negro school

is the larger of the two, there are no football, basketball,

or track programs offered at the Negro high school,

whereas there are football, basketball, and track teams

at the formerly all-white school (E. 106-107). While there

is a Future Farmers of America vocational club at the

white school, there is none at the Negro school (E. 106).

Teacher Segregation

The Gould school system has undertaken only token

faculty desegregation, with only one or two white teachers

being assigned to some duties at the Negro school and

no Negro teachers assigned to regular teaching at the

white school (E. 67-70). The school system has no plans

for substantial faculty desegregation. The superintendent

stated that “we have kept that in the background, we want

to get the pupil integration question settled and running

as smoothly as possible before we go into something else”

(E. 68). The system had not even begun integrated faculty

meetings or “ in-service” work shops, so as to produce

some integrated faculty and staff contact, as preparation

for future actual staff integration (E. 68).

When asked whether re-assignments of faculty members

were eventually contemplated, the superintendent stated

that “We do not have any plans to re-assign anybody”

(E. 69). He also indicated that this same standard of

continued assignment on the basis of the predominant

race of the student body would be applied to new teachers

hired in the future (E. 69). As compliance with HEW

requirements, the school system submitted a plan in which

7

it stated that it “will attempt to employ Negro teachers

in a predominantly white school on a limited basis, and

particularly in positions that do not involve direct in

structions to pupils” (R. 69). This is in spite of the fact

that the qualifications of the Negro teachers in the school

system were described by the superintendent as generally

superior to those of the white teachers, with every Negro

teacher having a bachelor’s degree and two having master’s

degrees, while there is only one white teacher with a

master’s degree and two are without any degrees (R. 32-

33, 94-95).

Intimidation

In response to the admittedly deplorable conditions in

the Negro high school, the PTA at the Negro school had

begun to protest these conditions to the superintendent

and the school board. The superintendent responded to

these petitions for redress of grievances by issuing an

order which forbade the Negro PTA from meeting in the

Negro high school (R. 63-64). He stated that “the reason

for that is, as I understand, the PTA had evolved into

largely a protest group against the school board and the

policies of the board. The members of that organization

were the same who planned to demonstrate against the

G-ould High School and had sent chartered bus loads of

people to Little Rock to demonstrate around the Federal

Building, who were getting a chartered bus of sympathizers

to come to this hearing today and it does not seem right

to us to furnish a meeting place for a group of people

that is fighting everything we are trying to do for them”

(R. 64).

When questioned as to whether this in effect meant

that the Negro high school patrons could not have a PTA,

the superintendent responded, “they can have a PTA but

8

they can meet somewhere else” (E. 64). He later admitted

that he had no knowledge that any plans for marches or

demonstrations had been made at a PTA meeting, and

that all that he had heard to this effect was pure hearsay

(E. 108-109). The superintendent and some members of

the Board of Education also obtained an injunction against

several civil rights groups in Gould, enjoining them from

making protests about conditions in the school system,

by picketing in the vicinity of the predominantly white

Gould High School (E. 63).

New Construction to Perpetuate Segregation

The plan for the program of construction which appel

lants sought to change dates back to 1954, a decade before

the school district gave any consideration to undertaking

desegregation, and apparently resulted from an equaliza

tion lawsuit brought at that time (E. 65-67, 72-77, 129, 131).

The plan provided for the construction of a complete

new high school on the site of the present all-Negro Field

Schools to replace the Negro high school facility entirely

(E. 65-67). The Field High School site is located just 8 to

10 blocks from the predominantly white Gould High School

site (E. 73), and each of the dual high schools has an

enrollment of only about 200 students (E. 29-30).

Plaintiffs sought to alter this new construction, which

was not scheduled to begin until January, 1967, by a timely

amendment during the hearing in November, 1965 (E.

137-138). However, the district court refused to grant re

lief in an opinion in April, 1966, and the court reporter

did not complete the transcript in the case until one year

later—April 1, 1967—thereby delaying the appeal (E. 140).

However, only the outer shell of the new building des

ignated for use as the new Field High School has been

9

completed at the time of the filing of this brief. A number

of walls are not in; plumbing facilities and fixtures have

not been added; much work remains to be done on the

interior walls and upon the roof; flooring has not been

laid; and all of the doors and windows have apparently

not been installed (see Affidavit of Attorney John W.

Walker, Appendix, infra, p. la).

The superintendent admitted that the Field High School

is now clearly a “Negro” school, and that it probably

would continue to be an all-Negro school, if it were re

placed with a new facility at the Field site (R. 67). He

admitted that it was economically inefficient for such a

small school district to undertake to construct a whole

new separate high school when it already had one, since

this will require having two libraries, two auditoriums,

two agriculture buildings, two science laboratories, two

cafeterias, two business departments, etc., and it is more

expensive per pupil for a small district such as Gould

to build a whole new facility from the beginning, rather

than expanding an already existing facility (R. 74-76).

The Gould High School is the most modern physical

facility in the district, having been the most recently con

structed in 1964 (R. 89). ' The adjacent predominantly

white Gould Elementary School was originally constructed

for use as a high school and was subsequently converted

to an elementary school (R. 81-82). There is a sizable

area of presently vacant land adjacent to the campus of

the predominantly white Gould High School which could

be condemned for public use for expansion of that high

school (R. 73-74).

The Negro Field Elementary School is also a modern

facility, which was constructed in 1954, with a gym

nasium and auditorium added in 1960, and two addi

tional class rooms in 1965 (R. 89-91). The gymnasium at

the Negro Field Elementary School is modern and presently

10

used by both elementary and high school students there,

so that it would be adequate for use by all of the elemen

tary school students in the district if the white elementary

students at Gould were shifted to Field and the Negro

high school students at Field were shifted to Gould

(E. 20). If the dual school systems were consolidated into

a single system, the elementary school would contain ap

proximately 450 students and the secondary school would

contain approximately 400 students (E. 29-30).

Denial of Relief by the Court Below

The district court denied all requested relief and dis

missed the case in a memorandum opinion filed April 26,

1966 (E. 12-25). In its opinion, the court indicated that

the facts that the school district had begun a desegrega

tion plan without being ordered to do so by a court, that

the plan was approved by the Federal Department of

Health, Education, and Welfare, and that some Negro

students were in fact attending the “white” school, were

persuasive as to the good faith of the board of education

in undertaking desegregation. Because of this, and the

reasons of administrative convenience offered by the board

of education for constructing the new high school replace

ment facilities on the site of the present Negro elementary

school rather than enlarging the previously all-white school,

the court determined that the replacement plan was not

“ solely motivated by a desire to perpetuate or maintain

or support segregation in the school system” (E. 24-25).

Plaintiffs filed notice of appeal from this decision in

proper time, and the case was scheduled to be heard at

the same time as the companion case of Kelley v. AU-

heimer, No. 18,528. However, the court reporter was sick

for an extended period of time, and was unable to com

plete the transcript until April 1st this year (1967) (E. 140).

11

STATEMENT OF POINTS TO BE ARGUED

I.

This Court Should Consolidate the Dual School Sys

tem in Gould so that All Elementary Students Attend

the Field Site and All High School Students Attend

the Gould Site, Under the Principles of Kelley v. Alt-

heimer.

Board of Education of the Oklahoma City Pub

lic Schools v. Dowell, 10th Cir., No. 8523,

January 23, 1967;

Board of Public Instruction of Duval County,

Fla. v. Braxton, 326 F.2d 616 (5th Cir. 1964);

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483

(1954);

Dowell v. School Board of Oklahoma City, 244

F. Supp. 971 (W.D. Okla. 1965);

Kelley v. The Altheimer, Arkansas Public

School District No. 22, 8th Cir., No. 18,528,

April 12, 1967;

Kemp v. Beasley, 352 F,2d 14 (8th. Cir. 1965);

McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents, 339 U.S.

637 (1950);

Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 U.S. 337

(1938);

Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U.S. 629 (1950);

United States v. Jefferson County Board of

Education, 5th Cir., Civil No. 23345, December

29, 1966; reaffirmed en banc, March 29, 1967;

Wheeler v. Durham City Board of Education,

346 F.2d 768 (4th Cir. 1965);

Wright v. County School Board of Greensville

County, Va., 252 F. Supp. 378 (E.D. Va. 1966).

12

II.

Appellants Are Entitled at the Very Least to a Com

prehensive Decree Governing the Desegregation Proc

ess Under Kelley v. Altheimer.

Board of Education of the Oklahoma City Pub

lic Schools v. Dowell, 10th Cir., No. 8523,

January 23, 1967;

Bradley v. School Board of tine City of 'Rich

mond, 382 U.S. 103 (1965);

Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U.S. 294

(1955);

Chambers v. Hendersonville City Board of Edu

cation, 364 F.2d 189 (4th Cir. 1966);

Clark v. Board of Education of Little Rock

School Dist., 369 F.2d 661 (8th Cir. 1966);

Kelley v. The Altheimer, Arkansas Public

School District No. 22, 8th Cir., No. 18,528,

April 12, 1967;

Kemp v. Beasley, 352 F.2d 14 (8th Cir. 1965);

McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents, 339 U.S.

637 (1950);

Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 U.S. 337

(1938);

Rogers v. Paul, 382 U.S. 198 (1965);

Smith v. Board of Education of Morrilton Sch.

Dist. No. 32, 365 F.2d 770 (8th Cir. 1966);

Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U.S. 629 (1950);

United States v. Jefferson County Board of

Education, 5th Cir., Civil No. 23345, December

29, 1966, reaffirmed en banc, March 29, 1967;

Wheeler v. Durham City Board of Education,

363 F.2d 738 (4th Cir. 1966).

13

ARGUMENT

I.

This Court Should Consolidate the Dual School Sys

tem in Gould so that All Elementary Students Attend

the Field Site and All High School Students Attend

the Gould Site, Under the Principles of Kelley v. Alt-

heimer.

This case is controlled by the principles of this Court’s

decision in Kelley v. The Altheimer, Arkansas Public

School District No. 22 et al., No. 18,528, April 12, 1967.

This Court held in Kelley that the location of schools

to perpetuate segregation must be enjoined.1

In Kelley, this Court was confronted with a school sys

tem which contained only 1,400 total students and

which had nevertheless rebuilt two elementary schools

on the traditional sites of the Negro and white schools

within a few blocks of each other just after adopting a

so-called “freedom of choice” desegregation plan. The

Court noted that (1) the original planning for the re

placement construction had been made during segregated

operation of the system long before any thought had been

given to desegregation, and the plans had not been either

changed or even reconsidered after ostensible desegrega

tion had begun; (2) there was almost negligible consulta

1 It should be noted that the trial judge’s opinion in Kelley v. Altheimer

denying relief against the new construction in that case relied on District

Judge Young’s opinion in this case, which preceded Kelley, also denying

such relief. See Kelley Record, No. 18,528, p. 248. The Court’s attention

is also respectfully invited to the Brief for Appellants in Kelley v.

Altheimer, No. 18,528, prepared by the same counsel as counsel for ap

pellants here, which contains an extended analysis of basic principles

of equity jurisprudence concerning implementation of the remedy in the

school desegregation eases— which discussion is not repeated here.

14

tion with the community on the plans for the replacement

construction; (3) the school system was so small that

there was no educational or financial justification under

generally accepted school administration practice for the

maintenance of separate buildings to serve two separate

student bodies within the same general area; (4) the

replacement plans were clearly premised on the continued

attendance at the Negro site of a number of students ap

proximately equal to the number of Negro students in

the system, and the continued attendance at the white site

of a number of students approximately equal to the num

ber of white students in the system; (5) the Superin

tendent indicated in his testimony that it was the system’s

assumption that the present all-Negro school might re

main an all-Negro school after the replacement construc

tion program; (6) the school system had undertaken no

steps since Brown to attempt to change the identity of

the Negro school from a racial to a non-racial school,

having undertaken no teacher desegregation and providing

the school with insufficient funds, resulting in heavier class

loads for its teachers, inferior library facilities, and a

lower scholastic rating.

Based on these facts, this Court concluded that “the

trial court’s finding that the new buildings were not de

signed to perpetuate segregation” was erroneous. It said:

The construction program, which served as the basis

of the appellants’ Complaint, emphasized the intention

of the Board of Education to maintain a racially segre

gated school system. Under such circumstances, it is

understandable that no white students can be expected

to transfer to [the Negro school].

# # *

15

This action sharply brought home to the Negro com

munity the Board’s expectation that their present and

future children were to continue attending the tradi

tionally all-Negro Martin School, and that there would

not be room for them at [the predominantly white]

Altheimer.

This Court held in Kelley:

We would add that the lower court should have

recognized the problems inherent in the Board’s con

struction plans and required them to be modified to

meet constitutional standards. Undue reliance on the

“deliberate speed” language in the Brown case, plus

adherence to the dictum in Briggs, has resulted in a

decision which makes it more difficult to achieve a

non-racially operated school system.

It is clear that school construction is a proper matter

for judicial consideration. Wheeler v. Durham City

Board of Education, 346 F.2d 768 (4th Cir, 1965);

Board of Public Instruction of Duval County, Fla.,

et al. v. Braxton, et al. [326 F.2d 616 (5th Cir. 1964)].

It is also clear that new school construction cannot

be used to perpetuate segregation. In Wheeler v.

Durham City Board of Education, supra at 774, the

Court stated:

“From remarks of the trial judge appearing in the

record, we think he was fully aware of the pos

sibility that a school construction program might

be so directed as to perpetuate segregation. . . .”

Relying upon Wheeler, the District Court in Wright

v. County School Board of Greensville County, Va.,

252 F. Supp. 378, 384 (E.D. Ya. 1966) said:

16

“This court is loathe to enjoin the construction of

any schools. Virginia, in common with many other

states, needs school facilities. New construction,

however, cannot be used to perpetuate segrega

tion. . . .”

We conclude that the construction of the new class

rooms by the Board of Education had the effect of

helping to perpetuate a segregated school system and

should not have been permitted by the lower court.

Nevertheless, this Court concluded in Kelley that since

the new building sought to be enjoined had already been

completed, and since it had given qualified approval in

Kemp v. Beasley, 352 F.2d 14 (8th Cir. 1965), to “freedom

of choice” plans of desegregation where there was some

reasonable probability that such plans would actually

desegregate the system, that the “freedom of choice” plan

adopted by that school system would be permitted to con

tinue for a period of time.

But this Court also emphasized in Kelley that the “free

dom of choice” plan must actually have some reasonable

probability of desegregating the system. In this connec

tion it pointed out that the situation in the school system

must be such that the mechanics of a “ freedom of choice”

plan can prevent or counteract the interference by the

school administration or board of education with students’

“ freedom of choice.” It also explicitly stated that the

constitutional obligation to desegregate applied to the

whole school system, and a system could not be considered

desegregated as long as it continued to have clearly identi

fiable Negro schools:

The appellee School District will not be fully desegre

gated nor the appellants assured of their rights under

the Constitution so long as the Martin School clearly

17

remains identifiable as a Negro school. The require

ments of the Fourteenth Amendment are not satisfied

by having one segregated and one desegregated school

in a District.

# #

[W]e have made it clear that a Board of Education

does not satisfy its constitutional obligation to deseg

regate by simply opening the doors of a formerly

all-white school to Negroes.

The Gould School District undertook no desegregation

at all from 1954 until compelled to do so at the time that

the Civil Rights Act of 1964 became applicable in 1965,

when it adopted a “ freedom of choice” plan in order to

receive federal funds. Now that Negro students can at

tempt to transfer to the white high school under that

plan, the school district has actually undertaken the long

promised but long delayed upgrading of the Negro high

school. A program of replacement construction has begun

on the site of the present all-Negro elementary school

which is designed to replace the Negro high school com

pletely.

The Superintendent stated that he expected that this

would continue to be an all-Negro school as only Negroes

would elect to go there (R. 67). The Negro site is located

just 8 to 10 blocks from the traditionally white site (R.

73), and each of the dual high schools has an enrollment

of only about 200 students (R. 29-30). The Superintendent

admitted that it is economically and educationally ineffi

cient for such a small school district to undertake to

construct a second separate high school, rather than ex

panding the one good one which it has on the traditionally

white site (R. 74-76). The planning for this replacement

construction goes back to long before the school system

began to consider desegregation, and was not subsequently

18

changed (E. 65-67, 72-77, 129, 131). No attempt has been

made to alter the racial identity of the all-Negro schools.

Unlike the off ending dual schools in Kelley, the replace

ment construction sought to be enjoined has not yet been

completed at the time of the filing of this brief. While the

foundation has been laid and portions of the outer shell

of a building erected, the various furnishings which would

cause this building to actually become a high school rather

than an elementary school have yet to be installed (See

affidavit in Appendix, infra, p. la.)

The Remedy

The present situation of the Gould school system ideally

lends itself to a plan of consolidation, with the Gould

School site becoming the single secondary school, and the

Field School site the single elementary school for the dis

trict. The present traditionally white Gould High School

is the most modern facility in the district, having been

completed in 1964 (E. 89). The immediately adjacent

Gould Elementary School was originally constructed for

use as a high school, and was subsequently converted to an

elementary school (E. 81-82). If the Gould Elementary

School were converted back to use as a high school, the

combined Gould Elementary-High School site would be

clearly suitable for all of the secondary students in the

district—numbering about 400 (E. 29-30). There is also a

sizable area of presently vacant land adjacent to the cam

pus of the Gould Schools which could be condemned for

public use for expansion of the high school if that should

prove necessary (E. 73-74).

The presently all-Negro Field Elementary School is also

a modern facility, constructed in 1954 with subsequent ad

ditions (E. 89-91). The gymnasium is adequate for both

the present number of Negro elementary and Negro high

19

school students, so that it would also be suitable for the

Field School to be used by all of the elementary students

in the system (R. 20). The replacement building presently

under construction and planned by the system for use as

the Negro high school is immediately adjacent to the Field

Elementary School, and can at this point easily be fur

nished as an addition to the elementary school—which

would make the combined Field School adequate for all of

the elementary students in the district, numbering about

450 students (R. 29-30).

Although this case is similar to Kelley, the facts devel

oped in this record indicate that the school administration

in the Gould school system is considerably more hostile to

the Negro community than that in the Altheimer system

and that therefore the approval of a “ freedom of choice”

desegregation plan, rather than a plan of consolidation,

would simply cloak the continued existence of a segregated

dual school system. The Court in Kelley noted that one

defect of the board’s plans for replacement construction

was the failure to seek community involvement in those

plans. Here, instead of simply failure to consult the Negro

community, we have a clear case of active intimidation of

the community, which had been seeking not even desegrega

tion of the schools, but simply equalization. The PTA of

the Negro school wTas prohibited from meeting at the school

once it began to protest conditions there, and an injunction

was obtained by the board of education against public pro

tests concerning school conditions (R. 63-64).

The degree of inequality between the Negro and white

high schools which has been maintained by the Gould

School District since 1954, despite a court judgment

requiring their equalization, suggests that the board is so

totally committed to victimizing the Negro community

that it could not be expected to administer a “freedom

20

of choice” plan fairly even under a court order. In Kelley

it is to be noted that the facilities, while unequal, were still

comparable enough that the replacement construction for

both the Negro and white schools was being undertaken at

the same time. Here the Negro high school is an old

wooden frame structure erected in 1924, while the white

high school is a modern new building constructed in 1964

(E. 10, 16, 83), and the Negro high school was admitted to

have been “grossly inferior” to the white high school at

least since 1954 by the president of the board of education

(E. 130). The white high school has an “A ” rating from

the State of Arkansas while the Negro high school is com

pletely unaccredited (E. 10, 31). The library at the Negro

school is virtually non-existent, while the library at the

white school contains approximately 1,000 volumes (E. 42-

43, 113-114). The unconscionable and direct exploitation

of Negro students and faculty members is unequivocably

demonstrated by the long-standing practice of requiring

Negro students to take time off from class to engage in

“fund-raising” projects such as cotton picking to pay the

“ enrollment fees” at the Negro school, while there were no

such fees at the white school (E. 44-46); and by the sub

stantially lower salary scales for Negro teachers as com

pared to white teachers of the same qualifications (E.

33-39).

Unless the Gould school district is enjoined from using

the addition to the Field site as a separate high school, not

only will a predominantly segregated school system be ir

revocably fastened upon the community for at least another

generation, but all of the students in the system—Negro

and white—will continue to pay the price of the inefficiency

which the attempt to operate a dual school system by such

a small district causes. It is to be noted that the school sys

tem in Kelley had 667 secondary students, while the Gould

21

system has only about 400 (E. 29-30). Appellants have re

printed in the Appendix to this brief, infra, pp. 3a-6a, a sum

mary of the expert testimony given in Kelley v. Altheimer,

outlining the basic educational theory as to why very small

schools are economically and educationally inefficient, which

this Court found persuasive. Since the Gould school sys

tem is in the county (Lincoln) immediately adjacent to

the one in which the Altheimer school system is located

(Jefferson), and since the Gould school system is identical

in pattern but even smaller in number of students to the

Altheimer system, all of these propositions apply a fortiori

to the Gould system. This is graphically illustrated by the

testimony concerning the disparity in course offerings at

the two present high schools. The Superintendent indi

cated that one reason why journalism was not offered at

the Field High School but was at Gould, was that not

enough students requested it at Field to justify assigning

a teacher to it (E. 93-94). If all students were attending

the same high school, everyone would have the opportunity

to take journalism, and more such enrichment courses

would be likely to be offered since there would be more

total students who would probably elect them. Similarly,

the basic sciences, chemistry and biology, are offered only

in alternate years at Gould while they are offered every

year at Field. In a consolidated system, all students would

have the opportunity to take each of these courses every

year.

Not only has the practice of segregation followed by this

school district been unconstitutional since 1954, Brown v.

Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483, but the “gross in

feriority” of the separate public school facilities provided

for Negro students has been unconstitutional at least since

1938, Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 U.S. 337

(1938), Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U.S. 629 (1950), McLaurin

22

v. Oklahoma State Regents, 339 TT.S. 637 (1950). The his

tory of this school district strongly argues that substantial

equitable remedies would be justified to overcome the re

calcitrance to equality for Negro students demonstrated.

However, all plaintiffs-appellants now seek is an injunc

tion requiring a different utilization of existing buildings

by the school district, rather than an actual change in loca

tion of a yet un-constructed new building. This is pre

cisely one component of the desegregation relief ordered

by the district court in Dowell v. School Board of Oklahoma

City, 244 F. Supp. 971 (W.D. Okla. 1965) and approved by

the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit in Board

of Education of the Oklahoma City Public Schools v.

Dowell, No. 8523, January 23, 1967. This is a relatively

minor step to assure a non-racial school system in the fu

ture, for the record in this case shows no practical, admin

istrative or other reason why this re-arrangement of the

use of facilities would be burdensome to the school district.

On the contrary, the record suggests that re-arrangement

would result in a financial saving to this hard pressed dis

trict (R. 74-76).

An order requiring the uncompleted new building on the

site of the Field Elementary School to be used as an ad

dition to that school, and the entire Gould School building

to be used as the consolidated high school, would simply be

to follow the requirement of the Kelley decree that “any

new facilities shall, consistent with the proper operation

of the school system, be designed and built with the objec

tive of eradicating the vestiges of the dual system and of

eliminating the effects of segregation.” See Kelley decree,

infra, Appendix, p. 10a. Cf. the similar decree of the U.S.

Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit in United States et

al. v. Jefferson County Board of Education et al., Civil

No. 23345, December 29, 1966, reaffirmed en banc, March

29, 1967.

23

II.

Appellants Are Entitled at the Very Least to a Com

prehensive Decree Governing the Desegregation Proc

ess Under Kelley v. Altheimer.

Since a dual school system has not yet been irrevocably

re-established in the Gould system as in Kelley v. Altheimer,

and a plan of re-arranging the use of the facilities can be

easily implemented so as to produce with certainty a uni

tary integrated school system, many of the complexities

which arise in attempting to enforce a desegregation plan

in a multiple school system need not arise here. The

present configuration of the facilities in the Gould system

is highly flexible, and there are no substantial administra

tive or practical obstacles of any kind which suggest that

this Court should not order their rearrangement. This

case comes to this Court on a record showing the admis

sion of the superintendent of the school system that the

system’s present plan for the use of its yet uncompleted

new facilities will continue to maintain an all-Negro high

school and an all-Negro elementary school (R. 67). For

the above reasons, we think this case is unique.

Nevertheless, if this Court should approve the continued

attempt by the Gould School District to meet its constitu

tional obligation to desegregate by employing* “freedom of

choice” , a comprehensive decree governing the desegrega

tion process following that in Kelley v. Altheimer (reprinted

infra, Appendix, pp. 7a-lla), should be entered. This school

district has shown by its past performance that not only is

it extremely hostile to the idea of equality for Negroes

and the end of segregation, but also that it is not predis

posed even to implement court orders requiring such goals

to be achieved. Therefore, an effective equity decree must

24

liave the requirements for a plan of desegregation spelled

out in detail in such a way that the board is not left undue

discretion to destroy its effectiveness. Cf. United States v.

Jefferson County Board of Education, supra; Board of

Education of Oklahoma City Public Schools v. Dowell,

supra.

The integration of faculty is absolutely fundamental to

the success of a desegregation plan. Yet the Gould School

District has assigned no Negro teachers to regular teach

ing at the traditionally white schools, and only one or two

white teachers to very limited duties at the traditionally

and still all-Negro schools (R. 67-70). Furthermore, the

system has no plans to substantially desegregate the fac

ulty in the future, in spite of having filed compliances with

the H.E.W. Guidelines, and has not even begun preparatory

programs looking toward eventual faculty integration (R.

68-69). It intends to apply the standard of assignment on

the basis of race even to new faculty members to be hired

in the future (R. 69).

As this Court said in Kelley:

“ . . the presence of all Negro teachers in a school

attended solely by Negro pupils in the past denotes

that school a ‘colored school’ just as certainly as if

the words were printed across its entrance in six-

inch letters. . . .’

“It may be added, that the converse is also true, that an

all-white faculty in a school attended exclusively by whites

in the past denotes that school as a ‘white school.’

“The failure of the Board to take any steps towards de

segregation of the faculty for more than a decade after

Brown 1 and II, and the statement of the superintendent

of schools that he does not intend to reassign faculty mem

25

bers within the school system make it highly probable that

faculties will not be desegregated unless such action is

compelled by this Court or by the Department of Health,

Education and Welfare. Regardless of the steps which

may be taken by H.EW. to secure compliance, we will

not avoid our responsibility in the matter.

“The Supreme Court and four Circuit Courts, including

our own, have made it clear that a school District may not

continue a segregated teaching staff [discussion of Brown

v. Board of Education, 349 U.S. 294 (1955), Bradley v.

School Board of City of Richmond, 382 U.S. 103 (1965),

and Rogers v. Paul, 382 U.S. 198 (1965)].

“ The Fourth, Fifth and Tenth Circuits have also held

that race must be eliminated as a basis for the employment

and assignment of teachers, administrators and other per

sonnel. The Board of Education of Oklahoma City Public

Schools, et al. v. Dowell, et al., supra; United States, et al.

v. Jefferson County Board of Education, et al., supra;

Wheeler v. Durham City Board of Education, 363 F.2d 738,

741 (4th Cir. 1966); Chambers v. Hendersonville City

Board of Education, 364 F,2d 189 (4th Cir. 1966); [other

citations omitted].

“Our own Court’s decisions on the obligation to desegre

gate faculties are unequivocal.

In Kemp v. Beasley, supra at 22, Judge Gibson said:

‘Plaintiffs also complain that the Court did not

order faculty and staff desegregation. The Court

recognizes the validity of the plaintiff’s complaint re

garding the Board’s failure to integrate the teaching-

staff. Such discrimination is proscribed by Brown

and also the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the regula

tions promulgated thereunder. . . .’

26

“In Smith v. Board of Education of Morrilton Sch. Dist.

No. 32 [365 F.2d 770 (8th Cir., 1966)], at 778, Judge Black-

mun said:

‘It is our firm conclusion that the reach of the

Brown decisions, although they specifically concerned

only pupil discrimination, clearly extends to the pro

scription of the employment and assignment of public

school teachers on a racial basis. (Citing cases.) This

is particularly evident from the Supreme Court’s posi

tive indications that nondiseriminatory allocation of

faculty is indispensable to the validity of a desegrega

tion plan. . . .’

“And, in Clark v. Board of Education of Little Bock

School ’Dist. [369 F.2d 661 (8th Cir., 1966)], at 669-70,

Judge Gibson stated:

‘We agree that faculty segregation encourages pupil

segregation and is detrimental to achieving a constitu

tionally required non-racially operated school system.

It is clear that the Board may not continue to operate

a segregated teaching staff. . . . It is also clear that

the time for delay is past. The desegregation of the

teaching staff should have begun many1 years ago. At

this point the Board is going to have to take accele

rated and positive action to end discriminatory prac

tices in staff assignment and recruitment. (Emphasis

added.)

* * # # *■

‘ . . . We are not content at this late date to ap

prove a desegregation plan that contains only a state

ment of general good intention. We deem a positive

commitment to a reasonable program aimed at ending

segregation of the teaching staff to be necessary for

the final approval of a constitutionally adequate de

segregation plan. . . .’

27

“From these decisions, it is clear that affirmative action

must be taken by the Board of Education to eliminate

segregation of the faculty. While this may well be the

most difficult problem in the desegregation process, it has

been made more difficult by the failure of the Board to

desegregate the faculties by filling vacancies on a non-

racial basis.

“We cannot permit the difficulties involved in desegregat

ing the faculties to deter us from achieving what the Con

stitution requires. To facilitate faculty desegregation, we

urge that the full understanding and cooperation of the

Negro and white faculty be sought. Experience has in

dicated that where an effort is made to obtain such co

operation, it is given, that the task is made easier and that

the results are more productive.”

Thus the decree of this Court with regard to faculty in

Kelley, reprinted infra, Appendix, pp. 8a-9a, should also be

entered in this ease.

Similarly, the shocking inequalities in facilities and pro

grams between the all-Negro and predominantly white

schools outlined in the Statement of the Case, supra, pp.

3-6, require that a. detailed decree on school equalization

be entered following the one in Kelley, Appendix, infra,

p. 10a. No argument is required that this situation is com

pletely unconstitutional, and has been so for at least sev

eral decades. Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, supra,

Sweatt v. Painter, supra, and McLaurin v. Oklahoma State

Regents, supra.

The decree should also provide that all H.E.W. require

ments should be complied with, and that the district court

should retain jurisdiction to ensure that the decree is car

ried out. In this regard it should particularly adopt the

annual reporting requirement of the Kelley decree, which

28

makes effective enforcement of a desegregation plan pos

sible. Similar provisions to those relating to students,

transportation, and construction should also be included.

See infra, Appendix, pp. 7a-lla.

Since the record of the Gould School District shows that

“ the policies and practices of the appellee School District

with respect to students, faculty, facilities, transportation

and school expenditures have been designed to discourage

the desegregation of the school system, and have had that

effect,” just as did the record of the Altheimer School Dis

trict, the vindication of the constitutional rights of the

Negro students of Gould to a desegregated education re

quires at the very least the entering of a comprehensive

decree following that in Kelley v. Altheimer.

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, appellants respectfully pray

that this Court reverse the lower court and grant the re

quested relief seeking a genuinely desegregated school sys

tem in accordance with the Constitution of the United

States.

Respectfully submitted,

J ack G reenberg

J ames M . N abrit , III

M ic h ael M eltsner

H en ry M . A ronson

M ic h ael J . H enry

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

J o h n W . W alker

1304-B Wright Avenue

Little Rock, Arkansas 72206

Attorneys for Appellants

A P P E N D I X

APPENDIX

Affidavit on the Status of the New School Construction

in the Gould School District (April 28 , 1967)

I n th e

U n ited S tates C ourt of A ppeals

F or t h e E ig h t h C ircu it

No. 18527

C ivil

A r t h u r L ee R a n e y , b y his m oth er and n ext fr ien d ,

M rs. R oxie R a n e y , et al..

Appellants,

v.

B oard of E ducation of th e G ould S chool D istrict ,

Appellee.

A F F I D A V I T

S tate of A rkan sas ,

C o u n ty of P u l a sk i, ss. :

I, John W. Walker, being duly sworn, state:

(1) I am one of the attorneys for the appellants herein,

and I have had occasion to travel to Gould, Arkansas in

the last week and observe the state of the construction

of the proposed new high school for Negroes (to be known

as the Field High School) in the City of Gould, Arkansas.

2a

(2) The Field High School for Negroes, now under con

struction, is being constructed on the premises of the

Field Elementary School for Negroes, adjacent to the

Field Elementary School and the gymnasium which were

constructed several years ago.

(3) The construction of the new Field High School is

partially complete but, to my observation, much work re

mains to be done. A number of the walls are not in;

plumbing facilities and fixtures have not been added; much

work remains to be done on the interior walls and upon

the ceiling or roof; much work remains to be done on the

floors, unless, of course, said floors are to be concrete;

all of the doors and windows do not appear to be in ; and a

significant drainage problem will have to be corrected be

fore the building will be ready for occupancy.

(4) The site of the new construction is approximately

10 or 12 blocks from the existing predominantly white

Gould Elementary and High School.

Signed:

J oh n W . W alker

Subscribed to and sworn before me,

a Notary Public, this 28 day of April,

1967.

A nobew J effries

N otary P ublic

M y C om m ission E x p ir e s :

D ecem ber , 1968.

3a

A Summary of the Testimony of Plaintiff’s Educational

Expert in Kelley v. The Altheimer, Arkansas Public

School District No. 22 et al. on the Inefficiency of

a Dual School System of Small Schools1

Plaintiffs obtained the services of an educational expert,

Dr. Myron Lieberman, to analyze the educational sound

ness of the then proposed new construction of small

dual schools within a few blocks of each other. Dr.

Lieberman is Director of Education Research and Develop

ment, and Professor of Education, at Rhode Island College

in Providence, Rhode Island.1 2 He made a substantial field

investigation of the Altheimer school system, and surveyed

the planning and impact of the construction proposal.3

T h e I n efficien cy of a D ual S chool S ystem of

S m all S chools

As part of his analysis of the possible bases for the

school board’s program of replacement construction, Dr.

Lieberman considered the overall educational efficiency

and desirability of the present dual structure of the

Altheimer school system with two small school complexes.

1 U. S. Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit, No. 18,528, April 12,

1967. This testimony is referred to on p. 19 of the Court’s slip opinion,

and is described on p. 20 of that opinion as “ virtually uncontradieted.”

It is also to be noted that counsel for the school district in this case

(Baney v. Gould) were co-counsel for the school system in Kelley and

participated in the deposition o f Dr. Lieberman. The record citations in

this summary are to the record in Kelley, No. 18,528.

2 He has a Bachelor’s degree in law and social science from the Uni

versity of Minnesota and Master’s and Ph.D. degrees in education from

the University of Illinois. He has co-authored four books on school per

sonnel administration and other aspects of public school planning (R 37-

40).

3 He examined physical facilities at both school complexes and inter

viewed the superintendent of schools, the principals o f the two school

complexes, and a number of teacher's and other administrators in the

school system. He was able to obtain relevant data from the school

administration to allow him to analyze the operation o f the system

(R. 40-42).

4a

He based his analysis particularly on what he considered

“the most important study of secondary education that

has been made in this country,” Dr. James Bryant Conant’s

Study of the American High School (R. 44-45). He pointed

out that in this work, Dr. Conant gives top priority in

educational planning to the elimination of small high schools

with graduating classes of less than one hundred [which

would mean a six-year secondary enrollment of at least

600] (R. 47).

A crucial reason for the desirability of larger high

schools is to provide adequate teachers for specialized sub

jects. When the total enrollment of the school falls below

a certain number, the small percentage of the student

body who are apt to elect any one of a number of special

ized academic subjects will probably be so small that the

school system will not feel that the expense of providing

a teacher for that subject is justified. Thus, if there were

two schools in which only ten students in each elect a

particular subject, the school board might not provide a

teacher for that subject in either school and therefore all

20 of those students would be deprived of the opportunity

of taking that subject; however, if all 20 of those students

were in the same school and elected that subject, the school

board would then feel justified in undertaking the expense

of a teacher for that subject (R. 47).

This type of analysis was applied by Dr. Lieberman

to other aspects of school operations at both the elemen

tary and high school levels. For instance, the Altheimer

school system is operating two libraries for grades one

through 12 six blocks apart. If each library is to be ade

quate and the facilities are to be equal, the school system

must buy duplicate copies of every book, and every time

duplicate copies of the same book are purchased where

one would be sufficient, this means there will be less money

to buy other different books that would be useful to students

(R. 45-46).

5a

Dr. Lieberman noted that there is also the matter of

specialization of training among personnel. For instance,

it is most desirable for elementary students to have spe

cially trained elementary librarians and secondary students

to have specially trained secondary librarians. However,

if there are two libraries, each of which covers grades 1

through 12, and only one librarian at each one, then they

will either have to have an elementary librarian and the

secondary pupils will suffer because the librarian is in

adequate for them, or vice versa. This would not be the

case if one school were an entirely elementary school and

the other school an entirely secondary school (R. 46).

Even where a school system does undertake to dupli

cate course offerings and services in each of two small

schools, Dr. Lieberman continued, it still cannot avoid

necessary resulting inefficiencies. For instance, schools

today perform a wide-range of functions in addition to

purely academic instruction, such as vocational guidance,

which require specialized personnel. If this special ser

vice or special type of course is offered at a small school,

it is not feasible for a specially trained teacher or other

such special service personnel to spend all his time doing

what he is a specialist in because there are too few pupils

to require his full-time services, and to that extent his

specialized training is wasted. The existence of such a

situation also makes it more difficult to attract such spe

cialized personnel, whose services are often difficult to ob

tain in the first place (R. 50).

Dr. Lieberman pointed out that the capital outlay for

equipment as well as the salary of specialized instructors

adds up to such a large figure in terms of the few enrolled

as to make many educational programs prohibitively ex

pensive in schools where the graduating classes have less

than one hundred (R. 47-48). Educational experts gen

erally assume that a school district which is capable of

6a

eliminating small schools will do so. Dr. Lieberman con

cluded that it did not make sense that a district such as

Altheimer would maintain “twro high schools, which even

combined, were less than the number needed to operate a

high school efficiently from an educational standpoint”

(R. 48). In reaching his conclusions, Dr. Lieberman said

that he had considered situations in which the construc

tion of separate facilities might be justified, such as the

children in the school district being so far apart that it

is not feasible to transport them to a central school, but

that none of these were applicable to the Altheimer case

(R. 50-51).

An additional element of the inefficiency which arises

from the operation of a dual school structure is the con

tinuing problem of maintaining equality of educational

opportunities between the two school systems. There are

many continuing difficult specific decisions to make, such

as how many books or how many teachers or what facili

ties, etc., should be placed in one school or the other (R.

55-56).

Dr. Lieberman concluded that there was no educational

or financial justification for the perpetuation of a com

pletely dual set of schools in the Altheimer school system

by the replacement construction. The operation of such a

dual system makes a sound educational program of “ such

exorbitant cost that the school system is never going to

pay it and can’t pay it” (R. 49-50). He also said: “I

regard this as a major dis-service to the white students

as well as to the Negro students” (R. 48).

He emphasized that this was not simply a matter of dif

ferences between himself and the Altheimer School Board

over educational practices, but rather a complete absence

of any justification for the dual construction according to

any educational theory or practice based on his profes

sional knowledge (R. 57-58).

7a

The Decree of the Court of Appeals for the Eighth

Circuit in Kelley v. The Altheimer, Arkansas Public

School District No. 22 et al., No. 18 ,528 , April 12,

1967, Slip Opinion pp. 25-30

T h e R em edy

The policies and practices of the appellee School Dis

trict with respect to students, faculty, facilities, transporta

tion and school expenditures have been designed to dis

courage the desegregation of the school system, and have

had that effect.

The decision of the District Court dismissing the ap

pellants’ Complaint is, therefore, reversed and remanded

for action consistent with this decision. The District Court

shall retain jurisdiction to insure that the appellee School

District carries out a detailed plan for the operation of

the school system in a constitutional manner so that the

goal of a desegregated school system is rapidly and finally

achieved. When the goal is achieved, the District Court

may relinquish jurisdiction, and the appellee shall be

relieved of its obligation to file the reports or plans re

quired by this decision with the District Court.

The plan approved by the District Court shall be con

sistent with, and in no event less stringent than, the one

set forth in the H.E.W. Guidelines, heretofore accepted by

the appellee School District. The plan, if the trial court

desires, may be identical to that set forth in the guide

lines. In any event, the plan, including the sections of

the guidelines adopted by the court, shall be embodied in

a decree and shall contain, in addition to the matter pre

viously referred to, provisions incorporating the require

ments set forth below. Annual reports shall be filed with

the Clerk of Court and served on the opposing parties

thereto no later than April 15, of each year, provided that

an initial report shall be filed no later than October 31,

8a

1967. Such, reports shall be in a form prescribed by the

District Court, and shall contain such information as the

court feels necessary to enable it to determine whether the

Board is complying with the decree.

S t u d e n t s

The use of the “freedom of choice” plan, as outlined

in the guidelines and as accepted by the appellee School

District, is approved and may be used unless and until

it becomes clear that the school system cannot be desegre

gated under such guidelines.

Uniform standards shall be developed for use in deter

mining whether a class or school is overcrowded, and for

use in determining the distance from home to school.

F a c u l t y

The faculty shall be completely desegregated no later

than the beginning of the 1969-70 school year.24 To this

end:

(1) Vacancies at Altheimer [the “white” school] shall,

when possible, be filled by the employment of qualified

and competent Negro classroom teachers for such vacan

cies and, at Martin [the “Negro” school], by the employ

ment of qualified and competent white classroom teachers

for such vacancies.

34 In The Board o f Education of Oklahoma City Public Schools, et al.

v. Dowell, et al., Civil No. 8523, 10th Cir., January, 1967, the Court fo l

lowed the recommendation o f education experts hired by the plaintiffs

and set the beginning of the 1969-70 school year as a target date for

having “ the same approximate percentage of non-white teachers in each

school as there now is in the system.” The same formula was followed

in Kiev v. County School Bd., 249 F.Supp. 239, 247 (W.D. Ya. 1966).

While we impose no exact formula in this case, we call the above formula

to the attention of the parties and the District Court as one which

comports with Brown. See also, Bobinson v. Shelby County Board of

Education, Civil No. 4916 (D.C. W.D. Tenn. January 19, 1967).

9a

(2) Immediate steps shall be taken by the appellee

School District to encourage full-time white faculty mem

bers to transfer from Altheimer to Martin, and full-time

Negro faculty members from Martin to Altheimer.26 If suf

ficient volunteers are not forthcoming, the appellee School

District shall assign a significant number of Negro class

room teachers to Altheimer for the school year 1967-68,

and a larger number for the 1968-69 school year. The ap

pellee School District shall also assign additional white

classroom teachers to the Martin School for each of the

above years. An equitable distribution of the teachers with

advanced degrees shall be considered in making said trans

fers.

(3) Should the desegregation process result in the clos

ing of either school, or the shutting down of a particular

grade in either school, displaced personnel shall, at the

minimum, be absorbed in vacancies appearing in the

system.

(4) Inequalities between white and Negro teachers with

respect to salaries and teaching load based on racial con

siderations shall be eliminated.

T ransportation

The existing transportation plan shall be discontinued

at the end of the present school year, and a new plan

inaugurated consistent with this opinion.

26 This requirement is not to be taken as in any way diminishing

the responsibility o f the Board of Education to desegregate the faculty

in the event volunteers are not forthcoming. The Supreme Court in

Brown v. Board of Ed. of Topeka, 349 U.S. 294, 299 (1955), said:

“ Pull implementation of these constitutional principles may re

quire solution of varied local school problems. School authorities

have the primary responsibility for elucidating, assessing, and solv

ing these problems; court will have to consider whether the action

of school authorities constitutes good faith implementation o f the

governing constitutional principles. . . . ”

10a

C onstruction and U se of F acilities

(1) Plans for the construction of additional facilities

shall be submitted to the District Court for approval.

Any new facilities shall, consistent with the proper opera

tion of the school system, be designed and built with the

objective of eradicating the vestiges of the dual system

and of eliminating the effects of segregation.

(2) Students at Martin shall be permitted to make rea

sonable use of library facilities at Altheimer until such

time as equal facilities at Martin School are provided.

S chool E qualization

(1) The appellee School District shall take prompt steps:

(a) to provide library facilities for the Martin School

which are substantially equal to those at Altheimer, (b)

to equalize pupil-teacher ratios and pupil-classroom ratios

between the Martin and Altheimer Schools, and (c) to

secure a prompt accreditation of the Martin School equal

to that currently held by Altheimer School.

(2) By October of each year, the appellee School Dis

trict shall serve on the opposing parties, and file with the

Clerk of Court, a report showing pupil-teacher ratios,

pupil-classroom ratios, and teacher expenditures both as to

operating and capital improvement costs; and, if there

are any substantial differences between Martin and Alt

heimer Schools, the appellee School District shall outline

the steps which it will take to eliminate said inequalities

and state the time it will take to eliminate them.

11a

H.E.W. G uidelines

Nothing in this opinion shall be considered as relieving

the appellee School District of any obligations that it has

under the Civil Eights Act of 1964, including the responsi

bility of complying with the H.E.W. Guidelines, which they

have voluntarily agreed to follow. To the extent that this

opinion may constitute approval of said guidelines, it is

not intended to deny a day in court to any person in as

serting any individual rights or to the Board of Education

in contesting any section of the H.E.W. Guidelines.

MEILEN PRESS INC. — N. Y. 219