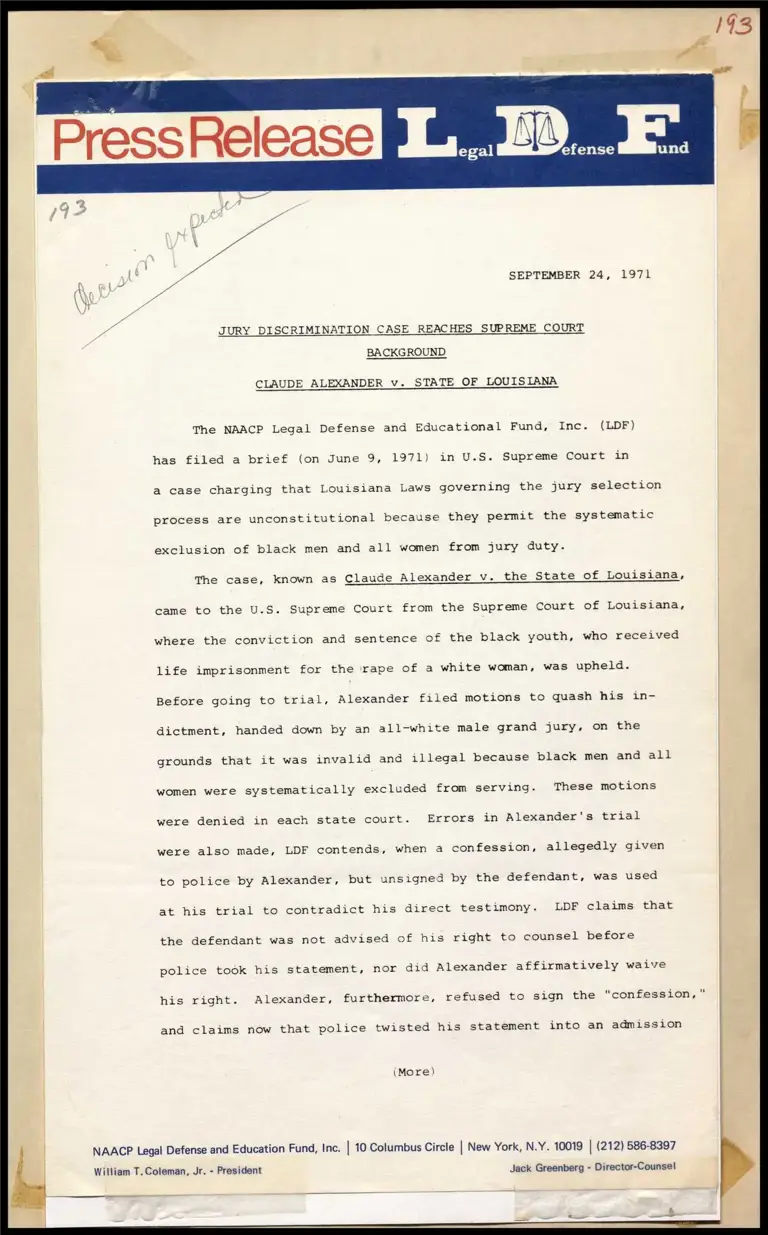

Jury Discrimination Case Reaches Supreme Court Background - Claude Alexander v. State of Louisiana

Press Release

September 24, 1971

Cite this item

-

Press Releases, Volume 6. Jury Discrimination Case Reaches Supreme Court Background - Claude Alexander v. State of Louisiana, 1971. 6d3ac3ac-ba92-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/726c540d-6da3-4c7f-8b52-104be3fbce20/jury-discrimination-case-reaches-supreme-court-background-claude-alexander-v-state-of-louisiana. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

egal AA efense und

SEPTEMBER 24,

JURY DISCRIMINATION CASE REACHES SUPREME COURT

BACKGROUND

CLAUDE ALEXANDER v. STATE OF LOUISIANA

The NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc. (LDF)

has filed a brief (on June 9, 1971) in U.S. Supreme Court in

a case charging that Louisiana Laws governing the jury selection

process are unconstitutional because they permit the systematic

exclusion of black men and all women from jury duty.

The case, known as Claude Alexander v. the State of Louisiana,

came to the U.S. Supreme Court from the Supreme Court of Louisiana,

where the conviction and sentence of the black youth, who received

life imprisonment for the ‘rape of a white woman, was upheld.

Before going to trial, Alexander filed motions to quash his in-

dictment, handed down by an all-white male grand jury, on the

grounds that it was invalid and illegal because black men and all

women were systematically excluded from serving. These motions

were denied in each state court. Errors in Alexander's trial

were also made, LDF contends, when a confession, allegedly given

to police by Alexander, but unsigned by the defendant, was used

at his trial to contradict his direct testimony. LDF claims that

the defendant was not advised of his right to counsel before

police took his statement, nor did Alexander affirmatively waive

his right. Alexander, furthermore, refused to sign the "confession,"

and claims now that police twisted his statement into an admission

(More)

NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund, Inc. | 10 Columbus Circle | New York, N.Y. 10019 | (212) 586-8397

William T. Coleman, Jr. - President Jack Greenberg - Director-Counsel

BACKGROUND - JURY CASE

PAGE 2

of guilt. State courts also denied the defendant's motion to

quash the introduction of such evidence.

If the case is successful, it could hasten the end to

blanket female exemption from 4 service still practiced in

several states. It could also Strengthen present laws forbidding

the exclusion of blacks from juries if the high court outlaws the

use of racial designations on jury lists.

The process which produced a list of some 13,000 Lafayette

Parish prospective jurors and then reduced it to the 12 white male

grand jurors who indicted Alexander is described in the LDF brief

as follows:

x According to the 1960 u.s. Census, some 44,986 persons,

over the age of 21, reside in Lafayette Parish, Louisiana.

Of these, 23,250 or 51.7% are women. The male population

of the Parish is 21,635, of which 4,405 or 20.27% are

black.

= Questionnaires, designed to determine eligibility for

jury duty, were sent by the Lafayette Parish jury com-

mission to every eighth person on a list the commission

compiled from various sources (e.g. telephone directory,

voter registration list, etc.) If the eighth person was

a man exempt from service by virtue of his profession,

Or any woman, his or her name was Passed over and the

next eligible person was sent the questionnaire.

x Approximately 13,000 male residents received these

questionnaires and a total of 7,374 responses, 1,015

or 13.76% of them from blacks, came back to the commission.

On all but 183 of these, respondents completed the

question as to their race.

_ To eliminate those ineligible to serve, the jury com-

Mission purportedly studied the questionnaires and came

(More)

BACKGROUND - JURY CASE

PAGE 3

up with about 2,0¢ persons who met the uirements

of a juror. available as to the

racial makeup of this list. However, it is known that

the jury commission, in approving each Prospective

juror, attached a card to his questionnaire designating,

among other things, the race of that person. Then, a

slip of paper, designating only name and address, was

attached to the card anda questionnaire.

2 Next, the jury commission claims, 400 persons were

Picked "at random" from the 2,000 Prospective jurors

and only their slips of paper were placed in the venire

box from which the names of Alexander's grand jury were

chosen. At this point, the venire box contained the

names of no women and only 27 black men.

‘s Finally, 20 names were pulled from the venire box,

including the name of one black man. When the final

12 were chosen from the 20, no black man was among them.

The LDF argument notes that if the 400 prospective jurors

were truly representative of the male population of Lafayette

County (the jury commission had an affirmative duty to utilize

methods that would have produced a truly representative jury role)

the venire box would have contained the names of some 81 black men.

Even a 13.76% figure for the venire would have produced 55 blacks

and 345 whites. Yet blacks made up only 27 or 6.75% of the

venire of 400. Even the most conservative odds against such a

poor random showing, LDF contends, are a highly improbable one in

20,000. LDF also places great weight on the fact that commissioners,

who claim that racial information was requested solely for "“iden-

tification" purposes, had ample opportunity to discriminate

against blacks.

(More)

BACKGROUND - JURY CASE PAGE 4

On the question of female exclusion, LDF is hopeful that

the Supreme Court will take a fresh look at the laws which

place the burden on women to step forward if they desire jury

duty. This, LDF claims, assumes that all women of all ages

have family responsibilities and would suffer hardship were they

called to serve. Since the basic premise is false, the law which

stems from it is excessive. And when it workd to exclude all

women, as it did in Lafayette Parish, it is unconstitutional as

well.

Although in a 1961 case, Hoyt v. Florida, the Supreme Court

upheld a Florida statute essentially the same as the Louisiana

law, LDF believes there is a major difference: Florida women

were being openly encouraged to volunteer for jury duty, while

the jury commission in Lafayette Parish took special pains to

exclude all women from the jury roles.

Finally, LDF would like the Supreme Court to forbid the use

of Alexander's alleged confession to contradict his direct testi-

mony.

Although past Supreme Court decisions have upheld the

legality of using evidence, including confessions, obtained

illegally, for the sole purpose of impeaching a defendant's

direct testimony on the witness stand, these cases dealt with

evidence or confessions that were reliable beyond any doubt. In

this case, however, Alexander's alleged confession was made

without the assistance of a stenographer or the use of a tape-

recorder. It was given in the presence of police officers only,

one of whom took notes and typed the confession that Alexander

refused to sign. Thus, LDF claims, where doubts exist as to the

accuracy of such illegally-obtained evidence, it must not be used

to impeach a defendant's testimony.

=I0=

For further information contact: Sandy O'Gorman 212-586-8397