Filing Notice for Brief Amicus Curiae PRIDE et al.

Correspondence

November 12, 1998

2 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Campaign to Save our Public Hospitals v. Giuliani Hardbacks. Filing Notice for Brief Amicus Curiae PRIDE et al., 1998. 0b5ede50-6835-f011-8c4e-002248226c06. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/728157c8-0ed0-4adf-83a6-7b07263e4e3b/filing-notice-for-brief-amicus-curiae-pride-et-al. Accessed February 12, 2026.

Copied!

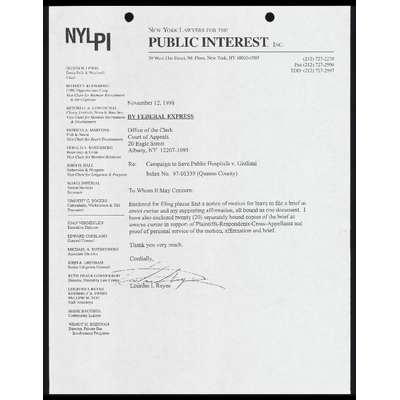

NEW YORK LAWYERS FOR THE

PUBLIC INTEREST nc

30 West 21st Street, 9th Floor, New York, NY 10010-6905 (212) 727-2270

: Fax (212) 727-2996

OGDEN N. LEWIS

Davis Polk & Wardwell TDD: 212) 727-2997

Chair

ROBERT I. KLEINBERG

CIBC Oppenheimer Corp.

Vice Chair for Member Recruitment

& Development

November 12, 1998

MITCHELL A. LOWENTHAL

Cleary, Gottlieb, Steen & Hamilton

Vice Chair for Member Recruitment BY FEDERAL EXPRESS

& Development

PATRICIA A. MARTONE Office of the Clerk

Fish & Neave

Vice Chair for Board Development Court of Appeals

GERALD A. RO 20 Eagle Street

Rosenman & aC Albany, NY 12207-1095

Vice Chair for Member Relations

JOHN H. HALL Re: Campaign to Save Public Hospitals v. Giuliani

Debevoise & Plimpton

Vice Chair for Litigation & Program Index No. 97-01339 (Queens County)

MARIA IMPERIAL

Victim Services

Secretary To Whom It May Concern:

TIMOTHY G. ROGERS ; ; ) ;

Cadwalader, Wickersham & Taft Enclosed for filing please find a notice of motion for leave to file a brief as

Treasiner amici curiae and my supporting affirmation, all bound as one document. I

have also enclosed twenty (20) separately bound copies of the brief as

amicus curiae in support of Plaintiffs-Respondents-Cross-Appellants and

proof of personal service of the motion, affirmation and brief.

JOAN VERMEULEN

Executive Director

EDWARD COPELAND

General Counsel

Thank you very much.

MICHAEL A. ROTHENBERG

Associate Director

JOHN A. GRESHAM

Senior Litigation Counsel

Cordially,

mere

RUTH DEALE LOWENKRON | bh Ly

Director, Disability Law Comer ly rele

LOURDES I. REYES Lotirdes 1 I Reyes

KIMBERLY B. SWEET

PAULINE H. YOO

Staff Attorneys

EDDIE BAUTISTA

Community Liaison

WENDY M. BRENNAN

Director, Private Bar

Involvement Programs

COURT OF APPEALS

STATE OF NEW YORK

CAMPAIGN TO SAVE OUR PUBLIC HOSPITALS - QUEENS

COALITION, an unincorporated association, by its

member WILLIAM MALLOY, CAMPAIGN TO SAVE OUR PUBLIC

HOSPITALS - CONEY ISLAND HOSPITAL COALITION, an

unincorporated association, by its member PHILIP R.

METLING, ANNE YELLIN, and MARILYN MOSSOP,

Plaintiffs-Respondents-Cross-Appellants,

-against-

RUDOLPH W. GIULIANI, THE MAYOR OF THE CITY OF

NEW YORK, NEW YORK CITY HEALTH AND HOSPITALS

CORPORATION, and NEW YORK CITY ECONOMIC

DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION,

Defendants-Appellants-Cross-Respondents.

BRIEF OF AMICUS CURIAE PROGRESSIVE RAINBOW INDEPENDENTS

FOR DEVELOPING EMPOWERMENT (PRIDE), THE SHOREFRONT PEACE

COMMITTEE, RICHARD N. GOTTFRIED, THE COUNCIL OF MUNICIPAL

HOSPITAL COMMUNITY ADVISORY BOARDS, THE COMMISSION ON THE

PUBLIC'S HEALTH SYTEM, IN SUPPORT OF PLAINTIFFS-RESPONDENT CROSS-

APPELLANTS

ARNOLD S. COHEN LOURDES I. REYES

ARTHUR A. BAER NEW YORK LAWYERS FOR THE

ALLISON BUSCH PUBLIC INTEREST

QUEENS LEGAL SERVICES CORPORATION 30 West 21st Street, 9th Floor

42-15 Crescent Street, 9th Floor New York, New York 10010

Long Island City, New York 11101 (212) 727-2270

(718) 392-5646

RAYMOND BRESCIA

URBAN JUSTICE CENTER

666 Broadway, 10th Floor

New York, New York 10012

(212)533-0540

REPRODUCED ON RECYCLED PAPER