Amended Answer to Request for Admissions of Defendants

Public Court Documents

February 21, 1986

9 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Dillard v. Crenshaw County Hardbacks. Amended Answer to Request for Admissions of Defendants, 1986. 8c4dc9de-b9d8-ef11-a730-7c1e5247dfc0. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/72daf831-b978-4457-bde2-05b5502b08ec/amended-answer-to-request-for-admissions-of-defendants. Accessed February 16, 2026.

Copied!

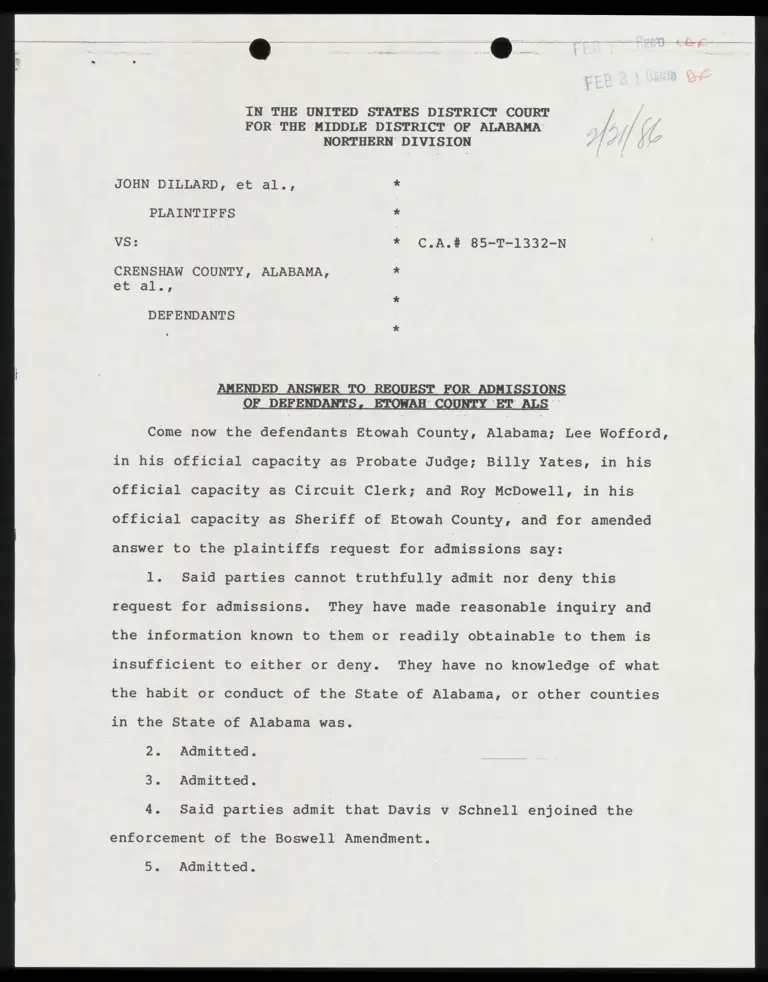

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE MIDDLE DISTRICT OF ALABAMA

NORTHERN DIVISION

JOHN DILLARD, et al.,

PLAINTIFFS

VS: C.A.# 85-T-1332-N

CRENSHAW COUNTY, ALABAMA,

et al.,

DEFENDANTS

AMENDED ANSWER TO REQUEST FOR ADMISSIONS

DEFEND AH ET S

Come now the defendants Etowah County, Alabama; Lee Wofford,

in his official capacity as Probate Judge; Billy Yates, in his

official capacity as Circuit Clerk; and Roy McDowell, in his

official capacity as Sheriff of Etowah County, and for amended

answer to the plaintiffs request for admissions say:

l. Said parties cannot truthfully admit nor deny this

request for admissions. They have made reasonable inquiry and

the information known to them or readily obtainable to them is

insufficient to either or deny. They have no knowledge of what

the habit or conduct of the State of Alabama, or other counties

in the State of Alabama was.

2. Admitted.

3. Admitted.

4. Said parties admit that Davis v Schnell enjoined the

enforcement of the Boswell Amendment.

5. Admitted.

6. Admitted.

7. Admitted.

8. Said parties admit that Act 417 of of the 1963 Regular

Session of the Alabama Legislature proposed a constitutional

amendment as set out in Request for Admission 8, but can neither

admit nor deny that it was defeated by a vote of 30,819 to

81,693 for that the information known to them or obtainable to

them is insufficient to either admit or deny that portion of

Request No. 8.

9. Admitted except as to the vote for adoption which is

unknown to these parties.

10. Admitted.

11. Admitted.

12. Admitted.

13. Admitted.

14. Admitted.

15. Admitted.

16. Admitted.

17. Admitted.

18. The answering parties can neither admit nor deny this

Request for Admission. Said parties have made reasonable

inquiry and information known to them or obtainable to them is

insufficient to either admit or deny.

19. Admitted.

20. Admitted.

21. Admitted.

22. Admitted.

23. Admitted.

24. Admitted.

25. Admitted.

26. Admitted.

27. Admitted.

28. Admitted.

29. Admitted.

30. Admitted.

31. The parties admit Number 31, except the statement it

was enacted apparently to prevent compliance with Federal Court

Orders, which is denied.

32. Admitted.

33. The parties admit Number 33, except the statement that

no black graduated from the law school from until 1977, which

statement the parties cannot truthfully admit nor deny. Said

parties have made reasonable inquiry and information known to

them or readily obtainable to them is insufficient to either

admit or deny said statement.

34. Admitted.

35. Admitted.

36. Admitted.

37. Admitted.

38. Admitted.

39. Admitted.

40. Admitted.

41. Admitted.

42, Admitted.

43. Admitted.

44. Admitted.

45. Admitted.

46. Admitted.

47. Admitted.

48. Admitted.

49, Admitted.

50. Admitted.

51. Admitted.

52. Admitted.

53. Admitted.

54. Admitted.

55. Admitted.

56. The answering parties in Etowah County cannot

truthfully admit nor deny this Request for Admission. The

parties have made reasonable inquiry and the information known

to them or readily obtainable to them is insufficient to either

admit or deny.

57. Admitted.

58. The parties in Etowah County cannot truthfully admit

nor deny this Request for Admission. The parties have made

reasonable inquiry and the information known to them or readily

obtainable to them is insufficient to either admit or deny.

60. Admitted.

61. The parties in Etowah County cannot truthfully admit

nor deny this Request for Admission. They have made reasonable

inquiry and the information known to them or readily obtainable

to them is insufficient to either admit nor deny. The paperback

book "An American Dilemma" is not available to them. The

request for admission calls for an interpretation of the

writings of Myrdal.

62. Admitted.

63. Admitted.

64. Admitted.

65. Admitted.

66. Admitted.

67. Admitted.

68. Admitted.

70. The parties in Etowah County cannot truthfully admit

nor deny this request for admission. Said parties have made

inquiry and the information known to them or readily obtainable

to them is insufficient to either admit nor deny. They do not

have access to the book "An American Dilemma" and have no

knowledge of Myrdal, his writings, books, or observations.

71. Admitted.

72. The answering parties in Etowah County cannot

truthfully admit nor deny this request for admission. The

parties have made reasonable inquiry and the information known

to them or obtainable to them is insufficient to either admit or

deny.

73. Admitted.

74. Admitted.

75. The parties in Etowah County cannot truthfully admit

nor deny this request for admission. Said parties have made

inquiry and the information known to them or readily obtainable

to them is insufficient to either admit nor deny.

76. The parties in Etowah County cannot truthfully admit

nor deny this request for admission. Said parties have made

inquiry and the information known to them or readily obtainable

to them is insufficient to either admit nor deny.

77. Admitted.

78. Admitted.

79. Admitted.

80. Admitted.

8l. Denied.

82. The answering parties in Etowah County cannot

truthfully admit nor deny this request for admissions. Said

parties have made reasonable inquiry and the information known

to them or readily obtainable to them is insufficient to either

admit or deny.

83. The answering parties in Etowah County cannot

truthfully admit nor deny this request for admissions. Said

parties have made reasonable inquiry and the information known

to them or readily obtainable to them is insufficient to either

admit or deny.

84. The answering parties in Etowah County cannot

truthfully admit nor deny this request for admissions. Said

parties have made reasonable inquiry and the information known

to them or readily obtainable to them is insufficient to either

admit or deny.

85. The answering parties in Etowah County cannot

truthfully admit nor deny this request for admissions. Said

parties have made reasonable inquiry and the information known

to them or readily obtainable to them is insufficient to either

admit or deny.

86. The answering parties in Etowah County cannot

truthfully admit nor deny this request for admissions. Said

parties have made reasonable inquiry and the information known

to them or readily obtainable to them is insufficient to either

admit or deny.

87. The answering parties in Etowah County cannot

truthfully admit nor deny this request for admissions. Said

parties have made reasonable inquiry and the information known

to them or readily obtainable to them is insufficient to either

admit or deny.

88. The answering parties in Etowah County cannot

truthfully admit nor deny this request for admissions. Said

parties have made reasonable inquiry and the information known

to them or readily obtainable to them is insufficient to either

admit or deny.

89. The answering parties in Etowah County cannot

truthfully admit nor deny this request for admissions. Said

parties have made reasonable inquiry and the information known

to them or readily obtainable to them is insufficient to either

admit or deny.

90. The answering parties in Etowah County cannot

truthfully admit nor deny this request for admissions. Said

parties have made reasonable inquiry and the information known

to them or readily obtainable to them is insufficient to either

admit or deny.

91. The answering parties in Etowah County cannot

truthfully admit nor deny this request for admissions. Said

parties have made reasonable inquiry and the information known

to them or readily obtainable to them is insufficient to either

admit or deny.

92. The answering parties in Etowah County cannot

truthfully admit nor deny this request for admissions. Said

parties have made reasonable inquiry and the information known

to them or readily obtainable to them is insufficient to either

admit or deny.

93. Admitted.

94. Denied.

95. Admitted.

96. Admitted.

97. Admitted.

98. The answering parties in Etowah County cannot

truthfully admit nor deny this request for admission. Said

parties have made reasonable inquiry and the information known

to them or readily obtainable to them is insufficient to either

admit or deny. They have no knowledge of what empirical studies

published by "reputable political scientists" say.

99. Denied.

100. The answering parties object to request for admission

100 as the information requested calls for opinion only.

101. The answering parties object to request for admission

101 as the information requested calls for opinion only.

FLOYD, KEENER & CUSIMANO

ATTORNEYS FOR DEFENDANTS

Etowah County, Alabama; Lee

Wofford; Billy Yates; and

Roy Se

LL

RA

816 Chestnut ay

Gadsden, AL 35999-2701

(205) 547-6328

I hereby certify that a copy of the foregoing has been

mailed Larry. T. Menefee, Attorney, P. O. Box 1051, Mobile,

Alabama 36633; Terry G. Davis, P. O. Box 6215, Montgomery,

Alabama 36104; Deborah Fins, Julius L. Chambers, 99 Hudson

Street, l6th Floor, New York, New York 10013; Edward Still, 714;

South 29th Street, Birmingham, AL 35233; and Reo Kirkland, Jr.,

P. O. Box 646, Brewton, AL 36427, this the _\2-day of February,

1986.

OF COUNSEL