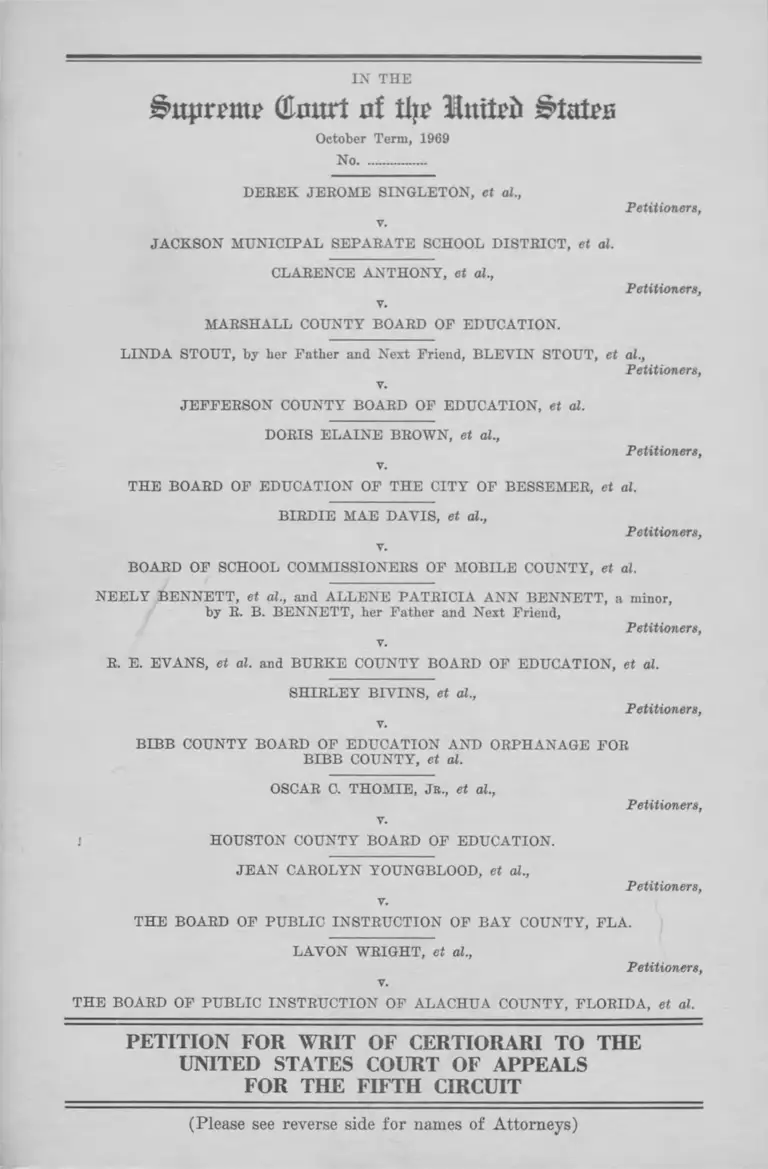

Singleton v Jackson Municipal School District Petition for Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

October 1, 1969

51 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Singleton v Jackson Municipal School District Petition for Writ of Certiorari, 1969. 4f77f984-c49a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/730b30bf-66a1-4d82-93cc-15826cd3b011/singleton-v-jackson-municipal-school-district-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed January 29, 2026.

Copied!

IN THE

Supreme (Emtrt of % llnltib

October Term, 1969

N o ._________

DEREK JEROME SINGLETON, et al.,

V.

JACKSON M UNICIPAL SEPARATE SCHOOL DISTRICT, et al.

Petitioners,

CLARENCE AN TH ON Y, et al.,

V.

MARSHALL COUNTY BOARD OF EDUCATION.

Petitioners,

LIN D A STOUT, by her Father and Next Friend, BLEVIN STOUT, et al.,

V.

JEFFERSON COUNTY BOARD OF EDUCATION, et al.

Petitioners,

DORIS ELA IN E BROWN, et al.,

V.

Petitioners,

TH E BOABD OF EDUCATION OF THE CITY OF BESSEMER, et al.

BIRDIE M AE D AVIS, et al.,

V.

Petitioners,

BOARD OF SCHOOL COMMISSIONERS OF MOBILE COUNTY, et al.

N EE LY BEN NETT, et al., and ALLENE PATRICIA A N N BENNETT, a minor,

b y R. B. BENNETT, her Father and Next Friend,

V.

Petitioners,

R. E. EVANS, et al. and BURKE COUNTY BOARD OF EDUCATION, et al.

SHIRLEY B IVIN S, et al.,

V.

Petitioners,

BIBB COUNTY BOARD OF EDUCATION AND ORPHANAGE FOR

BIBB COUNTY, et al.

OSCAR C. THOMIE, Jr., et al.,

V.

; HOUSTON COUNTY BOARD OF EDUCATION.

Petitioners,

JEAN CAROLYN YOUNGBLOOD, et al.,

V.

Petitioners,

THE BOARD OF PUBLIC INSTRUCTION OF B A Y COUNTY, FT.A.

LAVON WRIGHT, et al.,

V.

Petitioners,

THE BOARD OF PUBLIC INSTRUCTION OF ALACHUA COUNTY, FLORIDA, et al.

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

(Please see reverse side for names of Attorneys)

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

NORMAN C. AM AKER

M ELVYN ZARR

MICHAEL DAVIDSON

W IL LIA M ROBINSON

JONATHAN SHAPIRO

NORMAN J. CHACHKIN

DREW D AYS

10 Columbus Circle

New York, N. Y . 10019

OSCAR W . ADAMS, Jr.

U. W . CLEMON

1630 Fourth Avenue, N.

Birmingham, Ala. 35203

D AVIS H. HOOD, Jr.

2001 Carolina Avenue

Bessemer, Ala. 35020

VERNON Z. CRAWFORD

FR AN K IE FIELDS

570 Davis Avenue

Mobile, Ala. 36603

REUBEN V. ANDERSON

FRED L. BAN KS, Jr.

M ELVYN LEVENTH AL

5 3 8 ^ North Farish Street

Jackson, Miss. 39202

LOUIS-R. LUCAS

Ratner, Sugarmon, Lucas & Willis

525 Commerce Title Building

Memphis, Tenn. 38103

JOHN L. M A X E Y , II

STAN LEY L. TAYLOR, Jr.

North Mississippi Rural

Legal Services Program

Holly Springs, Miss. 38635

JOHN H. RUFFIN, Jr.

930 Gwinnett Street

Augusta, Georgia 30903

THOMAS M. JACKSON

655 New Street

Macon, Georgia 31201

THEODORE R. BOWERS

1018 North Cove Boulevard

Panama City, Fla. 32401

EARL M. JOHNSON

REESE MARSHALL

625 West Union Street

Jacksonville, Fla. 32202

Attorneys for Petitioners

I N D E X

PAGE

Opinions B elow ................................................................. 2

Jurisdiction..................... ..............................— .............. 2

Question Presented ...................... 2

Constitutional Provision Involved ................................ 3

Statement .................. 3

Reasons for Granting the W rit:

The Court Below Erred in Deciding an Im

portant Constitutional Issue in a Way in Con

flict with This Court’s Decision in Alexander v.

Holmes County Board of Education and in Con

flict with Decisions of Other Courts of Appeals 7

Conclusion .............................................— ...................... 15

Supplemental Statements of the Cases:

Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate School

District ......................... -.......................................... lb

.

Anthony v. Marshall County Board of Educa

tion ............................................................................. 4b

Stout v. Jefferson County Board of Education

and Brown v. The Board of Education of the

City of Bessemer..................— .............................. 7b

Davis v. Board of School Commissioners of

Mobile County............................................................ 12b

Bennett v. Evans and Bennett v. Burke County

Board of Education.................................................. 16b

11

Bivins v. Bibb County Board of Education and

Orphanage for Bibb County and Thomie v.

Houston County Board of Education................. 21b

Youngblood v. The Board of Public Instruction

of Bay County, Florida — ................................... 26b

Wright v. The Board of Public Instruction of

Alachua County, Florida ...................................... 28b

Table of Cases:

Alexander v. Holmes County Board of Education, 24

L.Ed.2d 41 (Opinion of Justice Black in Chambers)

(1969) ......................................... - ..... - ..........................10,11

Alexander v. Holmes County Board of Education,

396 U.S. 19 (1969) ..........2-3,4,5,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14

Bivins v. Board of Public Education & Orph. for Bibb

Co., Ga., 342 F.2d 229 (5th Cir. 1965) ....................... 14

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954) .... 11

Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U.S. 294 (1955) .... 9,11

Carter v. West Feliciana Parish School Board No. 944,

Oct. Term, 1969 ........................................................... 4, 7

Charles v. Ascension Parish School Board, 5th Cir.

No. 28573 (Dec. 11, 1969) .......................................... 7

Christian v. Board of Education of Strong School

District No. 83 of Union County, 8th Cir. No. 20038

(Dec. 8, 1969) ................................................................. 13

Davis v. Board of School Commissioners of Mobile

County, 414 F.2d 609 (5th Cir. 1969) ....................... 11

Dowell v. Board of Education of the Oklahoma City

Public Schools,------ U .S .------- (December 15, 1969)

(No. 603, Oct. Term, 1969) .......................................... 3, 8, 9

PAGE

Ellis v. Board of Public Instruction of Orange County,

Fla., 5th Cir., No. 28262, Dec. 12, 1969 ....................... 8

Harvest v. Board of Public Instruction of Manatee

County, Florida, 5th Cir. No. 28380, Dec. 12, 1969 .... 8

Lemon v. Bossier Parish School Board, 5th Cir. No.

28745, Dec. 12, 1969 ....................................................... 8

Nesbit v. Statesville City Board of Education, ------

F .2d ------ (4th Cir. No. 13299) .................................. 12

Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate School Dis

trict, 348 F.2d 729 (5th Cir. 1965); 355 F.2d 865

(5th Cir. 1966) ................................ ............................ 14

Steele v. Board of Public Instruction of Leon County,

5th Cir. No. 28143, Dec. 12, 1969 .............................. 8

Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U.S. 637 (1950).......................... 10

Watson v. Memphis, 373 U.S. 526 (1963) ....................... 10

Williams v. Iberville Parish School Board, 5th Cir.

No. 28571, Dec. 12, 1969 .............._............................... 8

Williams v. Kimbrough, 5th Cir. No. 28766, Dec. 10,

1969 .........................................* ..................................... 7

Statutes:

28 U.S.C. §1254(1) .......................................................... 2

28 U.S.C. § 1343 ....... ........................................................ 3

42 U.S.C. §§ 1981, 1983 ...................................... ........... 3

I ll

PAGE

IN THE

Supreme (Eintrt of tlje United Stall's

October Term, 1969

No.....................

DEREK JEROME SINGLETON, et al.,

V.

JACKSON M UNICIPAL SEPARATE SCHOOL DISTRICT, et al.

Petitioners,

CLARENCE ANTH ONY, et al.,

V.

MARSHALL COUNTY BOARD OF EDUCATION.

Petitioners,

LIN D A STOUT, by her Father and Next Friend, B LEVIN STOUT, et al.,

V.

JEFFERSON COUNTY BOARD OF EDUCATION, et al.

Petitioners,

DORIS ELAIN E BROWN, et al.,

V.

Petitioners,

THE BOARD OF EDUCATION OF THE CITY OF BESSEMER, et al.

BIRDIE MAE D AVIS, et al.,

V.

Petitioners,

BOARD OF SCHOOL COMMISSIONERS OF MOBILE COUNTY, et al.

N EELY BENNETT, et al., and ALLENE PATRICIA A N N BEN NETT, a minor,

by R. B. BENNETT, her Father and Next Friend,

V.

Petitioners,

B. E. EVANS, et al. and BURKE COUNTY BOARD OF EDUCATION, et al.

SHIRLEY B IVIN S, et al.,

V.

Petitioners,

BIBB COUNTY BOARD OF EDUCATION AND ORPHANAGE FOR

BIBB COUNTY, et al.

OSCAR C. THOMIE, Jb ., et al.,

V.

HOUSTON COUNTY BOARD OF EDUCATION.

Petitioners,

JEAN CAROLYN YOUNGBLOOD, et al.,

V.

Petitioners,

THE BOARD OF PUBLIC INSTRUCTION OF B A Y COUNTY, FLA.

LAVON WRIGHT, et al.,

V.

Petitioners,

THE BOARD OF PUBLIC INSTRUCTION OF ALACHUA COUNTY, FLORIDA, et al.

2

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

Petitioners pray that a writ of certiorari issue to review

the judgments of the United States Court of Appeals for

the Fifth Circuit entered in the above-entitled cases on

December 1,1969.

Opinions Below

The per curiam opinion of the United States Court of

Appeals for the Fifth Circuit is unreported and is set forth

in Appendix 12, pp. llTa-MOa.1 Opinions of the various

United States District Courts involved are unreported

and are set forth in Appendices 1 to 11, pp. la-116a.

Jurisdiction

The judgments of the United States Court of Appeals

for the Fifth Circuit were entered December 1, 1969 (Ap

pendix 13, pp. 141a-146a).

Jurisdiction of this Court is invoked pursuant to 28

U.S.C. § 1254(1).

Question Presented

Is the Court of Appeals’ ruling that implementation of

school desegregation plans may be postponed until the fall

of 1970 in a number of districts which still maintain dual

segregated systems, in conflict with this Court’s recent de

cisions in Alexander v. Holmes County Board of Education,

1 Because the material is voluminous, the opinions and judg

ments below are submitted in a separately bound appendix volume.

3

396 U.S. 19 (1969), and Dowell v. Board of Education of the

Oklahoma City Public Schools,------U.S. ------- (December

15, 1969), that unconstitutional dual school systems must

be desegregated “ at once” ?

Constitutional Provision Involved

This case involves the Equal Protection Clause of Section

1 of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the

United States.

Statement

Petitioners are Negro pupils and parents who brought

these civil actions in federal district courts2 in Mississippi,

Alabama, Georgia and Florida seeking desegregation of

their local public school systems as required by the Equal

Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. The

school systems involved in the ten cases serve the following

communities: (1) Jackson, Mississippi, (2) Marshall

County, Mississippi and Holly Springs, Mississippi (in the

same case), (3) Jefferson County, Alabama, (4) Bessemer,

Alabama, (5) Mobile County, Alabama, (6) Burke County,

Georgia, (7) Bibb County, Georgia, (8) Houston County,

Georgia, (9) Bay County, Florida and (10) Alachua County,

Florida. The United States has intervened in the district

courts as a plaintiff in the cases involving Jefferson County,

Bessemer, Mobile County, Bay County, and Jackson and

participated as amicus curiae in the other cases at the

request of the court of appeals.

2 Jurisdiction in the district courts was predicated upon 28

U.S.C. § 1343 and 42 U.S.C. §§ 1981, 1983 and the Due Process

and Equal Protection Clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment to the

Constitution of the United States.

4

The ten suits were filed at different times during the past

six years and the litigation has been varied.3 However, they

were all decided in a single opinion by the court below. In

order that the Court may have access to a reasonably de

tailed description of the varied facts and proceedings in the

ten cases, we attach at the end of this volume a supple

mentary statement of the cases for each suit. (See pp. lb

to 29b, infra.) This initial presentation is limited to the com

mon proceeding and decision, on appeal, which involved the

common question presented here. Each of the cases was

pending on appeal by the private plaintiffs (petitioners

here) in the Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit when

this Court rendered its decision on October 29, 1969, in

Alexander v. Holmes County Board of Education, 396 U.S.

19 (1969). On November 17-18, 1969, the Fifth Circuit sat

en banc to hear arguments in these and five other school

desegregation cases. Three Louisiana cases heard at the

same time are pending here on petition for certiorari sub

nom. Carter v. West Feliciana Parish School Board, No.

944, Oct. Term, 1969.

Although the facts and issues before the Fifth Circuit in

these cases varied considerably, that court concluded in

each of the cases that the district courts should require

further steps consistent with Alexander to complete the

disestablishment of the dual segregated school systems.

The court ordered the preparation of plans by the

Department of Health, Education, and Welfare in all

of the cases. However, such HEW plans had already previ

ously been prepared and submitted in the cases involving

Burke County, Houston County, Mobile County, Bessemer

3 The Jackson, Mississippi, Mobile, Alabama and Bay County,

Florida cases were filed in 1963; the Bibb County and Alachua

eases in 1964; the Jefferson County, Bessemer and Houston County

eases in 1965; the Marshall County case in 1968; and the Burke

County case in February 1969.

o

and Jefferson County. Those eases had been appealed be

cause the trial courts had in the summer of 1969 refused

petitioners’ requests for complete desegregation in the

1969-70 year and had either rejected the HEW plan (as

in Houston County) or approved plans which contemplated

delays. In the Alachua County, Bay County, Bibb County

and Marshall County cases the courts had permitted delays

by continuing modified free choice plans in effect for vary

ing periods of time (in some cases indefinitely). In the

Jackson case (from the Southern District of Mississippi

where the Alexander group of cases originated), the district

court had never acted on motions seeking modification of

the free choice plan; the appeal involved a question of the

effect of school construction on desegregation.

On December 1, 1969, the Fifth Circuit issued an opinion

deciding that in all of the cases desegregation should be

completed in two steps, with certain steps primarily involv

ing faculty desegregation to be accomplished by February

1, 1970, but with the requirement of complete student de

segregation postponed until the fall 1970 term of school.

The court said that although there were plans for desegre

gation in some of the cases, none of the districts had a plan

“ submitted in the light of the precedent of Alexander v.

Holmes County” which the court below correctly observed

requires that the “ school districts here may no longer oper

ate dual systems and must begin immediately to operate as

unitary systems.” However, the court below translated the

immediacy requirement of Alexander to permit delay until

next fall in the following paragraph:

Despite the absence of plans, it will be possible to

merge faculties and staff, transportation, services, ath

letics and other extracurricular activities during the

present school term. It will be difficult to arrange the

merger of student bodies into unitary systems prior to

6

the fall 1970 term in the absence of merger plans. The

court has concluded that two-step plans are to be im

plemented. One step must be accomplished not later

than February 1, 1970 and it will include all steps neces

sary to conversion to a unitary system save the merger

of student bodies into unitary systems. The student

body merger will constitute the second step and must

be accomplished not later than the beginning of the fall

term 1970. The district courts, in the respective cases

here, are directed to so order and to give first priority

to effectuating this requirement. (Slip Opinion p. 10;

emphasis added.)

The court ordered that the U.S. Office of Education

H.E.W. be requested to file plans in all the cases by January

6, 1970, and that the mergers of faculties and certain other

activities be accomplished not later than February 1, 1970,

with the pupil attendance plans to take effect in the fall

1970 school term.

Petitioners in each of the cases applied to Mr. Justice

Black, as Circuit Justice for the Fifth Circuit, for an in

junction pending certiorari to require immediate desegrega

tion of the school systems. On December 13 and 15, 1969,

Justice Black entered orders granting interim relief which

provided in substance that:

1. The school boards “ shall take such preliminary steps

as may be necessary to prepare for complete student de

segregation by February 1, 1970” ; and

2. the judgment below was stayed insofar as it defers

desegregation until the 1970-71 school year; and

3. the school boards are “directed to take no steps which

are inconsistent with or will tend to prejudice or delay full

7

implementation of complete desegregation on or before

February 1, 1970” ; and

4. directed the filing of certiorari petitions by December

19, 1969, and any responses to such petitions by January 2,

1970.

The Court entered substantially the same order on De

cember 13, 1969, in the three companion cases from Louisi

ana, sub nom. Carter v. West Feliciana Parish School

Board,------ U .S .------- (December 13, 1969).

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE WRIT

The Court Below Erred in Deciding an Important

Constitutional Issue in a Way in Conflict With This

Court’s Decision in Alexander v. Holmes County Board

of Education and in Conflict With Decisions of Other

Courts of Appeals.

The eleven school systems involved have in common the

fact that in each case the court of appeals concluded that

although it was necessary to order further steps to com

plete the disestablishment of unconstitutional racially seg

regated school systems, nevertheless, complete desegrega

tion might be postponed for nine months until the fall 1970

school term. The court of appeals decision decreeing two-

step desegregation plans with faculty reorganizations in

February 1970 and pupil reorganizations in September 1970

was intended to state a rule for the circuit. The same time

schedule has already been applied by the Fifth Circuit in

numerous other cases decided since the decision in these

cases.4

4 Subsequent cases decided by the Fifth Circuit applying the

same delay are as follows: Williams v. Kimbrough, 5th Cir. No.

28766, December 10, 1969; Charles v. Ascension Parish School

8

On two occasions this term this Court has unanimously

stated the constitutional rule governing the timing of public

school desegregation. On October 29, 1969, the Court ruled

that “ the obligation of every school district is to terminate

dual school systems at once and to operate now and here

after only unitary schools.” Alexander v. Holmes County

Board of Education, 396 U.S. 19 (1961). The Court held

that the court of appeals “ should have denied all motions

for additional time because continued operation of segre

gated schools under a standard of allowing ‘all deliberate

speed’ for desegregation is no longer constitutionally per

missible” (id.). The cases were remanded with directions

that orders be issued directing that the school districts

“begin immediately to operate as unitary school systems

. . . ” (id.). Then, on December 15, 1969, this Court adhered

to the rule of Alexander, supra, and wrote that “ The burden

on a school board is to desegregate an unconstitutional dual

system at once.” Dowell v. Board of Education of the Okla

homa City Public Schools, ------ U.S. ------ (No. 603, Oct.

Term, 1969). In Dowell, the court of appeals had vacated

a desegregation order and thus postponed implementation

until 1970 or later to afford an opportunity for litigation

about a full and comprehensive desegregation proposal due

to be submitted during the current school year. Mr. Justice

Brennan, as acting Circuit Justice, granted relief pending

certiorari to reinstate the trial court order. The full Court

held that the desegregation plan should have been imple

mented pending appeal.

Board, 5th Cir. No. 28573, December 11, 1969; Williams v. Iber

ville Parish School Board, 5th Cir. No. 28571, December 12, 1969;

Harvest v. Board of Public Instruction of Manatee County, Florida,

5th Cir. No. 28380, December 12, 1969; Steele v. Board of Public

Instruction of Leon County, 5th Cir. No. 28143, December 12, 1969;

Lemon v. Bossier Parish School Board, 5th Cir. No. 28745, Decem

ber 12,1969; Ellis v. Board of Public Instruction of Orange County,

Fla., 5th Cir. No. 28262, December 12, 1969.

9

With deference to the court below, we do not believe

that the delay until the fall of 1970 can be squared with the

plain holding of Alexander and Dowell, supra. We believe

that delay for nine months does not conform to the Alex

ander rule that dual systems be terminated “ at once . . .

now” and “ immediately.” Although we find no ambiguity

in the Alexander requirement of immediacy, the court of

appeals has construed it to require prompt action—that is,

desegregation in less than a year but not desegregation “at

once.” It seems evident that after fifteen years the “ all

deliberate speed” doctrine has become so much a part of

the law of school desegregation in the lower courts that it

lingers on in the opinion below even though it is said to

have been sent “ to its final resting place.”

In commenting on the action of a panel of the court de

laying desegregation for periods from two to ten months

in the Mississippi cases, the court of appeals stated approv

ingly that the court ordered desegregation at “the earliest

feasible date in the view of the court” (opinion below, slip

opinion p. 9). This search for the “ earliest feasible date”

for desegregation was apparently the standard applied in

the decision setting the fall 1970 deadine. But this search

does not seem different from the inquiry authorized in 1955

in Brown II to determine whether “additional time is nec

essary to carry out the ruling in an effective manner” and

such “ time is necessary in the public interest and is con

sistent with good faith compliance at the earliest practicable

date.” Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U.S. 294, 300

(1955). The similarity is striking between the Brown II

standard of “ the earliest practicable date” and the language

of the court below invoking desegregation at “the earliest

feasible date.”

This Court’s decision in Alexander is too recent and was

too emphatic for the court to indulge any reargument of

10

its holding that the deliberate speed doctrine has no more

place in the law of the land. Constitutional rights, denied

to the thousands of school children in these districts are

to be vindicated now. These rights are “personal and

present.” Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U.S. 637, 642 (1950). “ The

basic guarantees of our Constitution are warrants for the

here and now.” Watson v. Memphis, 373 U.S. 526, 533

(1963).

Moreover, Alexander requires a reversal here because

the judgments below permit the very same practical re

sults that the Alexander decree specifically found erroneous

and forbade, i.e., the postponement of desegregation until

the fall of 1970 because alleged administrative and educa

tional obstacles to desegregation were thought to justify

delay. While the exact delay granted by the court of ap

peals in the Mississippi cases last August was somewhat

indefinite, it was perceived by both sides as likely author

izing at least a year’s delay.5 6 The practical contradiction

between the judgment below and the Alexander holding

is all the more emphasized by the fact that in several of

these cases as in the Alexander group the Fifth Circuit

once ordered complete desegregation by September 1969

but delays were thereafter nevertheless permitted by the

district courts. As we have detailed in the supplemental

statements of the cases, infra, in both the Mobile and Bes

semer cases specific September 1969 deadlines were set by

the Fifth Circuit earlier in 1969 but were not enforced by

the district courts on remand.6 (See infra, pp. 13b to 15b,

5 In denying temporary injunctive relief, Mr. Justice Black as

Circuit Justice, observed that a year’s delay was at stake, saying:

“ Therefore, deplorable as it is to me, I must uphold the court’s

order which both sides indicate could have the effect of delaying

total desegregation of these schools for as long as a year.” Alexander

v. Holmes County Board of Education, 24 L.Ed.2d 41, 44 (Opinion

of Justice Black in Chambers, September 5, 1969).

6 District courts approved delays also in the Burke County,

Marshall County, Alachua County and Jefferson County cases.

11

and 7b to 9b; see also, Davis v. Board of School Commis

sioners of Mobile County, 414 F.2d 609, 611 (5th Cir. 1969),

and with respect Bessemer see Appendix 5, p. 67a.) The

difference was that the delay in the Mississippi cases was

approved by the Fifth Circuit in August, and this Court

was able to review the matter in October by expediting the

argument, while in the cases now before the Court the ap

peals were taken in August 1969 but were not decided by

the Fifth Circuit until December.

As mentioned previously, we do not believe these cases

are an occasion for rearguing the holding of Alexander.

That decision was reached after deliberation and full argu

ments, and also after fifteen years experience in seeking

implementation of Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S.

483 (1954). The day after Brown I was decided, it was clear

that these districts must be desegregated. Many districts

where there was a will to obey Brown did voluntarily

desegregate in September 1954 even before this Court’s

decree on implementation in Brown II. As Mr. Justice

Black has written, “ ‘All deliberate speed’ has turned out

to be only a soft euphemism for delay.” (Alexander v.

Holmes County Board of Education, 24 L.Ed.2d 41, 43,

Opinion of Justice Black in Chambers, September 5, 1969.)

The court of appeals opinion suggests that the delay

until the fall of 1970 is justified by the “absence of merger

plans.” But, of course, as the opinion below also acknowl

edges, in some of the districts unitary plans have been

prepared either by the Office of Education or by the school

boards. And in those cases where there are no H.E.W.

plans presently available, such plans will be available, un

der the court of appeals order, no later than January 6,

1970. We think it inconsistent with Alexander to delay

implementation of the plans which will be filed January 6

until next fall.

12

The Solicitor General has filed a memorandum in this

Court on the Motions for Injunctions which suggest that

the delay until the fall of 1970 was an appropriate formula

tion of a circuit-wide rule designed to cover cases in dif

fering situations, such as those not yet in court, cases not

yet decided on the merits, and cases without any desegre

gation plans drawn in light of Alexander. We submit that

the Alexander rule that such school officials have a duty to

act at once is the appropriate rule in these varying circum

stances. Continuing segregation in such school systems

should not be given even colorable legality fifteen years

after Brown. The Solicitor General’s memorandum also

suggests that the September 1970 timetable will enable the

court of appeals to once again review any decisions in

these cases concerning the adequacy of the plans before

they are implemented. The teaching of Alexander, and

even more pointedly, the teaching of Dowell, supra, is that

the status quo pendente lite should be implementation of

the best desegregation plan currently available. We urge

that the Fifth Circuit should have implemented the best

desegregation plans available in these cases when it ren

dered its December 1, 1969, decision. There were Office of

Education plans in the records in the cases involving Burke

County, Mobile and Houston County. In Marshall County

and Holly Springs there were school board plans for pair

ing and zoning available for implementation. Having

ordered new plans for all cases prepared by the Office

of Education by next January 6, there was no justifica

tion for deferring their implementation until the fall of

1970.

In the Fourth Circuit the Alexander ruling has been

applied more literally. On December 2, 1969, in five cases

decided sub nom. Nesbit v. Statesville City Board of Edu-

13

cation, ------ F.2d ------ (4th Cir. No. 13,299), the Fourth

Circuit ordered that the districts submit plans to the trial

courts not later than December 8, that hearings be con

ducted by district judges by December 15, and orders en

tered by December 19, with the plans to be made effective

in the North Carolina districts at the end of Christmas

vacation and in Virginia districts at the end of the semester

break in January 1970. The Fourth Circuit understood

Alexander to mean that “ the clear mandate of the Court

is immediacy.” On December 8, 1969, the Eighth Circuit

followed Alexander by ordering a district to file a plan by

January 7, 1970, for complete desegregation at the begin

ning of the second semester of the present school year.

Christian v. Board of Education of Strong School District

No. 83 of Urnon County (8th Cir. No. 20,038, Dec. 8, 1969).

The Department of Health, Education, and Welfare,

which plays a crucial role in the desegregation process,

also needs guidance in whether the law really requires

immediate desegregation or not. The Department deals

with hundreds of districts. I f it enforces Alexander faith

fully as written, H.E.W. can effect great changes in many

districts not involved in litigation as well as many that

are under court decrees. The decision below discourages

H.E.W. from requiring immediate steps by suggesting that

all the law requires in student desegregation is plans

effective in the fall of 1970.

Even though the Court has spoken so recently on this

subject, the case has continuing public importance. It is

true here, as it was in the Alexander case, that the case

inescapably involves whether the courts of the United

States will make good on the constitutional promise of

equal protection of the laws for Negro school children in

racially segregated school systems. Many of these young-

14

ters will have read or been told that this Court ruled on

October 29, 1969, that the law requires desegregation “ at

once . . . now,” “ immediately.” These cases furnish re

peated instances of the law’s promises being broken.7 Un

less these judgments are reversed, the promise of Alex

ander will be another broken promise.

7 In March 1965, the district court set a September 1969 desegre

gation deadline for the Jackson, Mississippi case; subsequent deci

sions on appeal advanced the deadline to state the objective of

“ total school desegregation by September 1967” for the Jackson

schools. See Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate School Dis

trict, 348 F.2d 729 (5th Cir. 1965); 355 F.2d 865, 869 (5th Cir.

1966). A 1968 deadline for desegregation was set in the Bibb

County case in a decision rendered on February 24, 1965. Bivins

v. Board of Public Education & Orph. for Bibb Co., Ga., 342 F.2d

229, 231 (5th Cir. 1965).

15

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, it is respectfully prayed that

the petition for a writ of certiorari should be granted and

the judgments below should be reversed. It is requested

that the matter be advanced for consideration and deter

mination expeditiously

Respectfully submitted,

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. N ABRIT, III

NORMAN C. AM AKER

M ELVYN ZARR

MICHAEL DAVIDSON

W IL LIA M ROBINSON

JONATH AN SHAPIRO

NORMAN J. CHACHKIN

DREW D AYS

10 Columbus Circle

New York, N. Y . 10019

OSCAR W . ADAMS, Jr.

U. W . CLEMON

1630 Fourth Avenue, N.

Birmingham, Ala. 35203

D AVIS H. HOOD, Jr.

2001 Carolina Avenue

Bessemer, Ala. 35020

VERNON Z. CRAWFORD

FR AN K IE FIELDS

570 Davis Avenue

Mobile, Ala. 36603

REUBEN V. ANDERSON

FRED L. BAN KS, Jr.

M E LVYN LEVENTH AL

538% North Farish Street

Jackson, Miss. 39202

LOUIS R. LUCAS

Ratner, Sugarmon, Lucas & Willis

525 Commerce Title Building

Memphis, Tenn. 38103

JOHN L. M A XE Y, II

STANLEY L. TAYLOR, Jr.

North Mississippi Rural

Legal Services Program

Holly Springs, Miss. 38635

JOHN H. RUFFIN, Jr.

930 Gwinnett Street

Augusta, Georgia 30903

THOMAS M. JACKSON

655 New Street

Macon, Georgia 31201

THEODORE R. BOWERS

1018 North Cove Boulevard

Panama City, Fla. 32401

EARL M. JOHNSON

REESE MARSHALL

625 West Union Street

Jacksonville, Fla. 32202

Attorneys for Petitioners

SUPPLEMENTAL STATEMENTS OF THE CASES

SUPPLEMENTAL STATEMENTS OF THE CASES

Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate School District

(S.D. Miss.)

Petitioners have sought in this case to desegregate the

public schools of Jackson, Mississippi since this suit was

filed in March 1963. In 1968-69 there were about 20,000 white

and about 18,000 Negro students in the system and only

about 5% of the Negroes (around 900) were enrolled in

traditionally white schools. Since 1967 the city has oper

ated under a freedom of choice plan decreed more or less

in accordance with the Fifth Circuit’s model Jefferson

County decree.

This is one of a long series of appeals of this case to the

Fifth Circuit. When the action was filed the trial judge dis

missed for failure of the plaintiffs to exhaust administrative

remedies; the Fifth Circuit reversed in 1964. Evers v.

Jackson Municipal Separate School District, 328 F.2d 408

(5th Cir. 1964). On remand the trial judge held a long hear

ing at which intervenors and the board attempted to over

turn the Brown decision by a factual showing of claimed

innate dfferences of the races. The trial judge felt com

pelled by precedents to deny relief and the Fifth Circuit

affirmed, stating its impatience with the board. Jackson

Municipal Separate School Dist. v. Evers, 357 F.2d 653 (5th

Cir. 1966), cert. den. 384 U.S. 961 (1966). The trial Court

ordered desegregation to begin in September 1964 in one

grade only after tentatively approving the hoard’s grade-a-

year plan. Finally in March 1965, the trial court approved

a plan for desegregating a few grades each year until all

grades were desegregated in September 1969 (see account

of this 355 F.2d at 867). Plaintiffs appealed and sought an

lb

2b

injunction pending appeal. The United States intervened

in the action. On June 22, 1965, the Fifth Circuit granted

an injunction pending appeal requiring desegregation to

be accelerated and setting a target date for desegregation

to be completed in Jackson in 1967. Singleton v. Jackson

Municipal Separate School District, 348 F.2d 729 (5th Cir.

1965). The objective of “total school desegregation by Sep

tember 1967” for the Jackson schools was reaffirmed by the

Court of Appeals opinion on the merits. Singleton v. Jack-

son Municipal Separate School District, 355 F.2d 865, 869

(5th Cir. 1966). The case was remanded for further con

sideration in light of the court’s opinion. On July 6, 1967

the trial court entered an order generally in conformity

with the model Jefferson County decree, but modified the

Fifth Circuit’s uniform decree in a number of respects.

Plaintiffs appealed protesting the changes of the uniform

decree, and prevailed when the Fifth Circuit again reversed.

Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate School Dist., 5th

Cir. No. 25,780, Oct. 11, 1968 (per curiam order).

The present appeal results from a motion filed by peti

tioners on March 18, 1968 to enjoin certain construction of

new facilities planned by the district, specifically 22 added

classrooms at four all-Negro schools on the claim that this

plan violated a provision of the model Jefferson decree and

was calculated to perpetuate segregation. After a hearing,

the trial judge filed an opinion denying injunctive relief

against the construction project. See opinion of May 10,

1968, Appendix 1.

Plaintiffs then sought and obtained an injunction pending

appeal from a panel of the Court of Appeals which entered

its order on June 24, 1968. During the pendency of the ap

peal in 1968 petitioners moved in the District Court for

further relief challenging the district’s freedom-of-choice

Supplemental Statements of the Cases

3b

plan under the doctrine of Green v. County School Board

of New Kent County, 391 U.S. 430 (1968), but were unable

to obtain a ruling on their motion. Because of a court re

porter’s illness the appeal was delayed and the case was

finally argued on November 17, 1968 along with more than

a dozen other cases considered by the court en banc.

On December 1, 1969 the Fifth Circuit issued its per

curiam decision covering this and the other cases. The Court

stated that even though the appeal involved only the con

struction issue it was bound to consider the intervening

decision of this Court in Alexander v. Holmes County Board

of Education, supra, and accordingly remanded the case to

the district court for the entry of an order consistent there

with. With respect to the construction dispute the court

stated that its temporary order enjoining the proposed

additions to all-Negro schools was “continued in effect until

such time as the district court has approved a plan for con

version to a unitary system.” (slip opinion p. 16).

The United States filed a brief in the Court of Appeals

arguing that the District Court had erred in refusing to

enjoin the construction project, and urging that the in

junction be continued in effect until the district court has

ruled on plaintiffs’ motion challenging the freedom of choice

system. (Brief of the United States, pp. 7-8).

Supplemental Statements of the Cases

4b

Anthony v. Marshall County Board of Education

(N.D. Miss.)

This action was filed by petitioners in May 1968 to

desegregate the two public school systems in Marshall

County, Mississippi, e.g., the Marshall County system and

the separate system in Holly Springs, the county seat.

On July 6, 1968, the district court approved a freedom of

choice plan (see the Order, Findings and Conclusions,

Appendix 2, p. 8a).

At the time of the 1968 hearing in the district court

each school board presented two plans—a pairing plan

and a geographic zoning plan. Either plan would fully

desegregate the school systems. But the boards’ purpose

and argument in presenting the plans was to show that

since these were majority black districts the desegregation

plans would put white students in the minority in every

school in the systems and that this would cause whites

to flee the school systems. The district judge accepted

this reasoning and approved freedom of choice plans not

withstanding this Court’s decision in Green v. County

School Board of New Kent County, 391 U.S. 430 (1968).

The Holly Springs Municipal Separate School District

has four schools, two predominantly white schools at one

location serving grades 1-6 and 7-12 and two Negro

schools serving the same grades at another campus about

a mile away. The district court found that there is no

substantial residential segregation in the district. Under

a free choice plan the black schools remained all black,

and a handful of Negroes attend the white school. In

1967-68 there were 1,868 Negroes and 875 white pupils;

60 Negroes or 3.2% attended the white schools.

The Marshall County school system which serves all

of the county not covered by the Holly Springs Municipal

Supplemental Statements of the Cases

5b

district has 3 white schools and 4 Negro schools serving

(in 1967-68) 3,606 Negro students and 1,193 white students.

In 1967-68 only 22 Negroes or 0.6% attended white schools,

and the black schools remained all-Negro. As described

in the amicus curiae brief of the United States in the

court below, the schools are arranged as follows:

In Potts Camp, about 15 miles southeast of Holly

Springs, there is a traditionally white school serving-

grades 1-12 and a Negro school for grades 1-8. The

Negro high school students in this area are bussed to

Holly Springs. In Slayden, which is about 15 miles

north of Holly Springs, and in Byhalia, which is

about 18 miles northwest of Holly Springs, there are

two 12 grades schools in each community, one tradi

tionally for each race. The other Negro school serves

grades 1-8 and is located in Galena, about 12 miles

southwest of Holly Springs. The white students and

the Negro high school students who live in this area

are bussed to Holly Springs. (Brief of the United

States, in Court of Appeals, pp. 10-11.)

The Fifth Circuit reversed in April 1969, finding that

the free choice plan had failed to desegregate the system.

Anthony v. Marshall County Board of Education, 409

F.2d 1287 (1969). The district court on remand approved

a plan which was designed to replace freedom of choice

over a three year period (on a basis of four grades a

year) with a plan for assigning pupils according to

achievement test scores (see Appendix 2). Under this

plan, which would not reach all grades until the school

year 1971-72, a specified quota of the pupils scoring high

est on the tests would be assigned to the previously white

school and those with lower scores would be assigned to

the present all-Negro schools.

Supplemental Statements of the Cases

6b

On plaintiffs’ appeal the court of appeals again re

versed on December 1, 1969. As to the testing plan the

court said: “ We pretermit a discussion of the validity

per se of a plan based on testing except to hold that test

ing cannot be employed in any event until unitary school

systems have been established.”

In the Fifth Circuit the United States filed a brief

amicus curiae urging reversal and the immediate imple

mentation of the pairing or zoning plans devised by the

school boards. The brief of the United States said:

It is recommended that this Court remand the case

to the district court with instructions to implement

forthwith plans based on pairing or zoning or both.

Such plans should stay in effect until the school

boards propose an alternative and can establish con

clusively that such alternatives will result in unitary

school systems in which racial segregation is neither

compelled nor encouraged. (Brief for the United

States, p. 15.)

Supplemental Statements of the Cases

7b

Stout v. Jefferson County Board of Education, et al.

(N.D. Ala.) and

Brown v. The Board of Education of the City of Bessemer,

et al. (N.D. Ala.)

These suits involve the speed of public school desegre

gation in Jefferson County, Alabama and the City of

Bessemer, Alabama where these two cases were com

menced by the petitioners, Negro pupils and parents in

1965. In both cases the United States intervened as a

plaintiff in the same year. The litigation has been ex

tensive, including repeated appeals, and the progress has

been slow. The Court of Appeals opinion in these two

cases issued on June 26, 1969 collects the citations to the

prior reported opinions and describes the course of the

litigation briefly (see Appendix 3). On April 17, 1967 both

systems were ordered to begin operating under the model

freedom of choice decree promulgated by the Fifth Cir

cuit in United States v. Jefferson County Board of Edu

cation, 372 F.2d 836, (5th Cir. 1966) affirmed on rehearing,

380 F.2d 385, (5th Cir. 1967), cert, denied, 389 U.S. 840

(1967). When the case came before the Fifth Circuit in

June 1969 that Court described the facts:

. . . The model decree has resulted in 3.45 per cent

of the Negro students in the Bessemer system attend

ing school with white students for the year 1968-69.

There are eleven schools in Bessemer; one all-white,

four all-Negro, and six desegregated. The school pop

ulation of the Bessemer system for the year 1968-69

was 8,615; 6,360 Negroes and 3,255 whites.

In the Jefferson County system, 3.43 per cent of

the Negro students attended previously all-white

schools in the year 1968-69. The school population

Supplemental Statements of the Cases

8b

Supplemental Statements of the Cases

was 65,659; 47,830 whites and 17,829 Negroes. There

were 105 schools; 48 remained all-white, 28 all-Negro

and 29 were desegregated.

In no school in either system has a white student

chosen to attend a Negro school. There has been some

assignment both of white and Negro teachers in each

system to teach in schools where their race is in the

minority but not a marked degree. (Emphasis Added).

A separate appeal involving faculty desegregation in

these systems was also decided on July 1, 1969, and the

case remanded with instructions on that issue. Sub nom.

United States v. Board of Education of the City of Bes

semer, 5th Circuit No. 26,582, July 1, 1969 (consolidated

with Jefferson County and Birmingham cases).

Faced with two systems where over 96% of Negro pupils

still attended all-Negro schools despite numerous appeals

and four years of litigation the Court of Appeals in June

1969 remanded the cases to the district court with specific

directions including among others, that:

(a) the cases be given the “highest priority” ;

(b) the district court request HEW to prepare plans

to be “ effective for the beginning of the 1969-70

school term” and to be “approved by the district

court no later than August 5, 1969” ;

(c) Any appeals to be expedited according to a pre

scribed schedule.

The proceedings following remand require separate treat

ment.

Bessemer A fter Remand,

After the remand the Bessemer Board filed an interim

plan for the 1969-70 school year and the Department of

9b

HEW advised the Court that it needed more time to pre

pare a final plan. The district court entered an order and

opinion on August 5, 1969 (Appendix 5, pp. 67a-72a) which

approved the Bessemer interim plan and delayed final

desegregation. The court justified this because HEW pol

icies did not require total integration in 1969-70 in districts

that were more than 50% Negro or in districts where there

was construction of schools in progress which would af

fect the desegregation plan. The court justified the delay

saying: “ The Bessemer School System meets both of these

tests.” (Appendix 5, p. 69a).

The petitioners filed objections to the temporary plan.

Petitioners also filed two alternative plans for desegre

gation prepared by one of petitioners’ attorneys, Mr. Hood

a long-time resident of the city. However, as stated the

court approved the board’s interim plan and allowed the

board and HEW until November 15, 1969 to file a final

desegregation plan. The interim plan ordered for 1969-70

required that some Negroes would be transferred to the

white schools to fill them to capacity.

Jefferson County Upon Remand

The Jefferson County Board and the Department of

HEW both filed plans on August 1, 1969. The plans were

identical in terms of school zone lines, grade alignments

and the usage of schools. The HEW plan continued a num

ber of features absent from the county board’s plan includ

ing a racial majority to minority transfer plan, a detailed

plan for faculty desegregation, and suggestions for ex

plaining the plan in the community and enlisting support.

Some features of the plan were contingent upon future

school construction, and the school board did not project

full implementation until 1971-72, while H.E.W. provided

Supplemental Statements of the Cases

10b

for completion in the 1970-71 school year. The private

plaintiffs filed objections to the plans and the United

States also filed objection, pointing out shortcomings of

the Board’s plan. Most of the objections were rejected and

the board’s plan was approved on August 5, 1967 (Ap

pendix 4).

The Court predicted that under the board’s plans 74.29%

of the Negroes would be in integrated schools in 1969-70,

that 85.16% would be integrated in 1970-71, and that

100% would be in integrated schools in 1971-72. The court

found that the plan abolished all the vestiges of the dual

school system and established a unitary system.

Plaintiffs appealed under the expedited schedule pre

viously fixed.

Jefferson County and Bessemer on Appeal

The cases were heard on appeal en banc along with a

dozen other districts. After mentioning its opinion of

June 26, 1969 (see Appendix p. 133a), the Court stated:

The record does not reflect any substantial change

in the two systems since this earlier opinion, and it

is therefore unnecessary to restate the facts. The

plans approved by the district court and now under

review in this court do not comply with the standards

required in Alexander v. Holmes County.

We reverse and remand for compliance with the

requirements of Alexander v. Holmes County and the

other provisions and conditions of this order, (slip

opinion p. 17).

In both cases the United States filed briefs in the court

of appeals. In Bessemer the United States argued that

the case should be remanded for adoption of a new system

Supplemental Statements of the Cases

l ib

of desegregation in view of the Alexander decision and

in view of the fact that both the school board and HEW

filed new plans in the district court on November 15, 1969

while the case was pending on appeal. In Jefferson the

United States argued that it was necessary to devise a

plan for a unitary system in the case “during the period

prior to the completion of the construction projects upon

which the present terminal plan depends.” The United

States also said the zone lines previously recommended

should be reevaluated in light of experience.

The brief of the United States in the Jefferson County

case pointed out that during the pendency of the appeal,

on October 3, 1969 the United States moved the district

court for an order requiring the school board to show

cause why they should not be adjudged in contempt for

their failure to follow the desegregation plan approved

for 1969-70. The district court had not ruled on the mo

tion to show cause.

Supplemental Statements of tlw Cases

12b

Birdie Mae Davis v. Board of School Commissioners of

Mobile County (S.D. Ala.)

On August 1, 1969, the District Court for the Southern

District of Alabama approved in part a desegregation plan

recommended for Mobile County by the Department of

Health, Education, and Welfare. The H .EW . plan provided

arrangements for virtually complete desegregation,* but

deferred desegregation in the eastern portion of metropoli

tan Mobile, where 86% of the Negroes in the county live,

until the 1970-71 school year and leaves in effect in the in

terim pupil assignment arrangements which have been pre

viously ruled impermissible by the Fifth Circuit. Peti

tioners, Negro pupils and parents who have sought the de

segregation of the system in this case since 1963, objected

to the delay and appealed when the plan was approved by

the trial judge without a hearing.

This case involves when school desegregation will be com

pleted in Mobile County, Alabama, a large district involving

both rural and urban areas. In the six years since the case

began it has been reviewed by the Fifth Circuit on at least

seven occasions.** The reported decisions in this case dem

onstrate the school board’s unremitting resistance to com

pliance with Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483

(1954).

Supplemental Statements of the Cases

* The plaintiffs (petitioners here) do object that the H.E.W.

plan fails to provide for desegregation of five large all-black

schools, but the H.E.W. arrangements for most of the county

provide for satisfactory desegregation in plaintiffs’ view.

** The Fifth Circuit opinions, prior to the one now sought to

be reviewed, are reported sub nom. Davis v. Board of School Com

missioners of Mobile County, 318 F.2d 63 (1963); 322 F.2d 356

(1963), stay denied by Mr. Justice Black, 11 L.Ed.2d 26, 84 S.Ct.

10 (1963), cert, denied, 375 U.S. 894 (1963), rehearing denied,

376 U.S. 898 (1964); 333 F.2d 53 (1964), cert, denied, 379 U.S.

844 (1964) ; 364 F.2d 896 (1966); 393 F.2d 690 (1968) ; 414 F.2d

609 (1969).

13b

On June 3, 1969, the Fifth Circuit held, for the second

time—the first time being in March 1968*—that the de

segregation plan approved by the trial judge for Mobile was

not adequate for several reasons, including that:

(1) attendance zones for the elementary and junior high

schools in metropolitan Mobile were “ constitutionally un

acceptable” ; and

(2) the continued use of a free choice plan for high school

assignments in this area also violated the court’s 1968 man

date (see 414 F.2d 609).

Yet the proceedings which followed, and which we now

seek to have reviewed here resulted in these very same

attendance zones and free choice system being continued in

effect during the 1969-70 school year. This is true notwith

standing the fact that an H.E.W. plan which would almost

complete the job of desegregation was submitted to the

district court on July 10, 1969.

The Fifth Circuit order of June 3, 1969, directed that the

district court order the school board to request H.E.W. to

collaborate in preparing a plan “ to fully and affirmatively

desegregate all public schools in Mobile County, urban and

rural . . . ” (414 F.2d at 611). The court of appeals said

that the new plan must be “ effective for the beginning of

the 1969-70 school term” (id.). The court set a timetable

for submission and consideration of either an agreed plan

or H.E.W.’s independent recommendations, stipulated that

no plan should be approved without a hearing, and that the

district court should order some plan no later than August

1, 1969 (414 F.2d at 611).** On July 10, 1969, H.E.W. sub

* See 393 F.2d 690 (1968).

**M r. Justice Black, in July 1969, denied the board’s applica

tion for a stay of the Fifth Circuit order.

Supplemental Statements of the Cases

14b

mitted its plan, a large volume containing 116 pages fol

lowed by a series of maps. The H.E.W. plan eliminated

freedom of choice and, through zoning, grade restructuring,

pairing and transportation of students would substantially

integrate the system.

However, in the plan, H.E.W. proposed that the court

defer implementation in the eastern part of metropolitan

Mobile until 1970-71. Plaintiffs immediately filed objec

tions to this feature (and also to the plan’s failure to inte

grate five large all-black schools) noting that the deferral

of the plan would limit its immediate application to only

4,500 or 14% of Mobile’s black students. Over 26,000 or

86% of Mobile’s Negro students live in the eastern metro

politan area, and of this number only 3,000 attended white

schools in 1968-69 under the present arrangement.

The school board also objected to the entire H.E.W. plan.

The United States moved for an order accepting the plan

without modification thereby assenting to the proposed de

lay until 1970-71.

Despite the fact that the court of appeals had explicitly

ordered a hearing on objections, the district court, without

an evidentiary hearing,* entered an order on August 1,

(Appendix 6). Petitioners have no objection to the order

as it relates to the relatively small number of Negroes in

rural Mobile and the western part of metropolitan Mobile.

The difficulty concerns the eastern part where the bulk of

the black community resides. The district court said it was

“not satisfied” with the H.E.W. plan. Although there had

* The school board’s attorney filed an affidavit in this Court,

when seeking a stay from Mr. Justice Black in July 1969, stating

■under oath that Judge Thomas, the district judge, had a conference

in chambers with the school board’s attorney, members of the

school board and two representatives of the Department of Health,

Education, and Welfare, on July 3, 1969. The plaintiffs’ attorneys

had no notice of this meeting and were not present.

Supplemental Statements of the Cases

15b

been no hearing, the court found the H.E.W. plan “ contains

some provisions which I think are both impractical and

educationally unsound.” No examples, no elaboration was

offered. As for timing, the court approved the delay until

1970-71, leaving the existing arrangement intact in eastern

Mobile, and ordered the school board to file another plan

by December 1, 1969.

Plaintiffs promptly appealed. The school board did not

file a formal cross-appeal but argued that certain parts of

the order should be reversed. The United States urged ap

proval of the delay.

On December 1, 1969, the Fifth Circuit affirmed the order

of the district court, “with directions to desegregate the

eastern part of the metropolitan area of the Mobile County

School System and to otherwise create a unitary system in

compliance with the requirements of Holmes County and in

accordance with the other provisions and conditions of this

order” (slip opinion pp. 18-19).

According to school board reports submitted in the trial

court November 26,1969, there are now 73,504 pupils in the

Mobile system; 42,620 white pupils and 30,884 Negro pupils.

At the present time 21,557 Negro pupils (69.7%) attend

either 15 schools that are all-Negro (15,125 students or

48.9%) or 7 schools that are about 99% Negro (6,432 Ne

groes and 17 whites).

In early December 1969, the school board and H.E.W. sub

mitted separate desegregation plans to the district court

in accordance with the direction in the August 1, 1969,

order. Petitioners’ counsel have not yet been served with

copies of these proposals. Our view is that implementation

of the H.E.W. plan of July 10,1969, which will substantially

desegregate the system, should not be delayed pending liti

gation about objections to the new H.E.W. and school board

proposals.

Supplemental Statements of the Cases

16b

Bennett v. Evans and Bennett v. Burke County Board

of Education (S.D. Ga.)

The case involves when school desegregation will be

completed in Burke County, Georgia, a district with eleven

schools and (during 1968-69) 5,433 students of whom 1,586

were white and 3,847 were black. The District Court for

the Southern District of Georgia found on June 20, 1969,

that the system “is organized, and always has been, as

a dual one based upon race” in violation of the constitu

tional rights of the petitioners who are Negro students

and their parents. The District Court ordered that a

desegregation plan for Burke County be submitted July

30, 1969, by the Department of Health, Education, and

Welfare (HEW ). As ordered, HEW filed a plan which in

a single document included both an interim plan and a

complete desegregation plan. Over plaintiffs’ objections,

the district court on August 22, ordered the implementa

tion of only the interim plan and ordered that the school

board and HEW submit a further plan for the 1970-71

year without setting any deadline for such submission.

The Negro students promptly appealed to the Fifth

Circuit and moved for injujnctive relief pending appeal

or, alternatively, for summary reversal which was denied

September 22, 1969. On October 2, 1969, the Court of

Appeals expedited the case for hearing en banc with

other pending cases.

This case was filed in the Southern District of

Georgia in February, 1969, was consolidated with another

case challenging the Georgia laws for selecting school

boards, and was brought on for trial on June 17, 1969.

Thereafter, on June 20, 1969, the district judge en

tered an order including findings of fact and conclusions

of law (Appendix 7). The court concluded that the

Supplemental Statements of the Cases

17b

Burke County system was a dual system based on race;

that under a freedom of choice system only 30 or 0.7%

of the 3,847 black students attended school with whites;

that the school faculties were completely segregated with

no white teachers in black schools or vice versa; that the

bus system was maintained on a “ segregated, duplicative

and overlapping basis” ; that in 1966 HEW cut off fed

eral financial assistance because of the failure to de

segregate; that mainly because of overcrowding six of

the seven all-Negro schools had lost accreditation; and

that the “ existing freedom of choice approach offers

no hope of achieving at any time in the near future the

degree of integration necessary to satsfy the demands

of the Fourteenth Amendment . . (See Appendix 7).

The court found that during 1968-69 the school enroll

ments were as follows:

Supplemental Statements of the Cases

School Grades

Pupils

White

Pupils

Black

Cousins (Sardis) ............ .... 1-8 0 366

Girard (Girard) ................ .... 1-8 0 336

S.E. Dinkins (Midville) ........ 1-8 0 359

Palmer (Keysville) .......... .... 1-8 0 214

Gough (Gough) ................ .... 1-7 0 349

Blakeney Elementary ........... 1-7 0 1126

(Waynesboro)

Blakeney High .................. .... 8-12 0 915

(Waynesboro)

Waynesboro Elementary ... .... 1-8 755 27

Waynesboro H igh .............. .... 9-12 377 3

Sardis-Girard-Alexander ..... 1-12 357 0

(Sardis)

Midville Elementary ............. 1-7 49 0

18b

The court ordered that the board submit its data to

the U.S. Office of Education, HEW and seek to develop

a plan in collaboration with HEW. The court said that

if a plan could be agreed on between the board and HEW

by July 30, 1969, it would be approved unless plaintiffs

showed that it did not meet constitutional standards, and

that if no plan were agreed on HEW should submit a plan.

HEW prepared and recommended a desegregation plan

which would have completely integrated the faculty and

students of the district beginning with the 1969-70 school

year. However, HEW also attached an interim plan for

“ partial desegregation” which provided only for assign

ing Negroes from overcrowded Negro schools to bring

the 4 white schools up to their capacity while permitting

the 7 all-Negro schools to remain all-Negro. As to faculty

assignments, the interim plan provided for 7 white and 14

Negro teachers to be assigned across racial lines, whereas

the terminal plan provided for faculty assignments so that

the racial ratio in each school would equal that in the entire

system. The HEW document made clear that HEW recom

mended the complete plan but that the interim steps were

presented in the event that the court decided to defer

complete desegregation beyond September 1969.*

* The plan stated at page 3a under the heading “ Possible In

terim Steps” :

“ The plan that we have prepared and that we recommend

to the Court provides for complete disestablishment of the dual

school system in this District at the beginning of the 1969-70

school year. Because of the number of children and schools

in this district, and because of the proximity of the scheduled

opening of the school year, implementation of our recom

mended plan may require delay in that scheduled opening.

Should the Court decide to defer complete desegregation of

this school district beyond the opening of the coming school

term, the following steps could in our judgment be taken this

fall to accomplish partial desegregation of the school system

without delay or with very minimal delay, in the scheduled

opening of the school year.”

Supplemental Statements of the Cases

19b

After a hearing on August 15, 1969, the court on August

22, 1969, filed an order approving implementation of the

interim plan only during the 1969-70 school year and over

ruling plaintiffs’ objections to the interim plan. The court

left future desegregation to be accomplished on an in

definite timetable directing that a further plan for 1970-71

be submitted as soon as the board and HEW could agree,

or if there was no agreement that HEW should file a plan

“within a reasonable time.” The August 22 order is at

tached as Appendix 7, p. 85a.

As stated above, the Court of Appeals denied relief pend

ing appeal and summary reversal during September 1969,

and then after expediting the appeal reversed on December

1, 1969.

With respect to Burke County, the Court of Appeals

concluded as follows:

No. 28409—Burke County, Georgia

The interim plan in operation here, developed by

the Office of Education (HEW ), has not produced a

unitary system. The district court ordered prepara

tion of a final plan for use in 1970-71. This delay is

no longer permissible.

We reverse and remand for compliance with the re

quirements of Alexander v. Holmes County and the

other provisions and conditions of this order.

However, as stated previously, the Fifth Circuit order

required faculty desegregation and certain other steps to

be taken by February 1, 1970, but permitted student de

segregation arrangements to remain unchanged until the

fall of 1970.

Supplemental Statements of the Cases

20b

In the Fifth Circuit the United States filed a brief amicus

curiae urging that the Court of Appeals order immediate

integration, and stating:

“ The district court’s approval of the interim plan

should be reversed, and the district court should be

directed to order full implementation of the HEW

plan at once.” (Brief of United States, pp. 57-58).

Supplemental Statements of the Cases

21b

Bivins v. Bibb County Board of Education and Orphanage

for Bibb County, et al. (M.D. Georgia), and

Thomie v. Houston County Board of Education

(M.D. Georgia)

Introduction

These cases involve the speed of school desegregation in

two counties in the Middle District of Georgia. In both

counties the district court, by orders entered August 12,

1969 (Appendices 8 and 9), approved the continuation

of freedom of choice desegregation plans with certain

modifications in each case. In the Houston County case the

court requested the submission of an H.E.W. plan, and the

plan was submitted on July 28, 1969. However, when the

school board objected to the H.E.W. plan the court per

mitted a continuation of a modified free choice plan. In the

Bibb County case the court approved a modified free choice

plan proposed by the school board. In both cases the peti

tioners, Negro pupils and parents, appealed and sought in

junctions pending appeal which were denied. The cases were

then set for a hearing en banc with other pending cases.

Houston County, Georgia

Suit was filed to desegregate the public schools of Hous

ton County, Georgia in April 1965. The district court en

tered an order requiring implementation of a freedom of

choice plan on May 20,1965, and subsequently amended that

order, while retaining the free choice approach, on April

24, 1967, and again on June 22, 1967. The Houston County

system has 23 schools (5 all-Negro schools and 17 predomi

nantly white schools) serving (in 1968-69) 12,217 (78%)

white pupils and 3,295 (22%) Negro students.

No whites attend the five all-Negro schools which were

attended by about 83% of the Negro students in 1968-69

Supplemental Statements of the Cases

22b

under the free choice plan. About 17% of the Negroes at

tend predominantly white schools. During argument in the

court below, counsel for the board said that currently in

1969-70 there are about 2,500 Negroes (73%) in all-Negro

schools and 944 (27%) attending predominantly white

schools. (Transcript of argument, p. 8.)

On July 8, 1969, the district court directed the defendants

to file proposed amendments to their plan and invited the

Department of Health, Education, and Welfare to submit a

plan. On July 28, 1969, H.E.W. submitted a plan providing

for complete desegregation of the school system in the 1969-

70 term which provided for zoning most elementary schools

and feeder systems and pairing of schools in the upper

grades. The school board objected to the H.E.W. plan and

proposed to continue the freedom of choice plan with certain

proposed amendments.

On August 12, the court entered an order approving the

school board’s proposed amendment to the free choice plan

which provided for increasing desegregation somewhat by

closing a Negro school and discontinuing certain grades in

another, for holding inter-school class exchanges on a part-

time basis in such things as driver education and industrial

arts and home economics, and for certain additional faculty

desegregation steps. The plan left the several all-Negro

schools still all-Negro.

Plaintiffs appealed, and the court of appeals reversed

directing complete student desegregation in the fall of 1970.

While the case was pending on appeal the United States

filed a brief amicus curiae urging the court of appeals to

order immediate desegregation in these words:

In light of the recent decisions, we think that the

order of the district court approving the modified free

dom of choice plan should be reversed with directions

to implement, at once, the HEW desegregation plan.

Supplemental Statements of the Cases

23b

The district court’s approval of free choice was in

error. E.g., Adams v. Mathews, 403 F.2d 181 (5th Cir.

1968); United States v. Greenwood Municipal Separate

School District, 406 F.2d 1086 (5th Cir. 1969). The

modifications of the free choice plan produce only a

small increase in the number of Negroes who will attend

white schools and no desegregation of Negro schools.

In these circumstances, it is appropriate for this

Court to direct immediate implementation of the HEW

plan. Alexander v. Holmes County School Board,------

U .S .------ (1969) (per curiam). (Brief for the United

States, p. 67.)*

Bibb County, Georgia

Desegregation began in Bibb County under a court order

entered in this case April 24, 1964, when the trial court

approved a stair-step desegregation plan which began with

the twelfth grade in 1964 and required a projected nine

years to complete the transition period. The plaintiffs ap

pealed to the Fifth Circuit which reversed as to the timing

of desegregation and on February 24, 1965, ordered that

the dual system be completely abolished in all grades by

September 1968. Bivins v. Board of Public Education &

Orph. for Bibb Co., Ga., 342 F.2d 229, 231 (5th Cir. 1965).

The court set the 1968 deadline for desegregation in these

words (342 F.2d at 231):

Four years including September 1965, that is by Sep

tember 1968, is that maximum additional time to be

Supplemental Statements of the Cases

* The above quoted brief was submitted in the Fifth Circuit on

or about November 13, 1969, by Assistant Attorney General Jerris

Leonard and other attorneys of the Department of Justice. The

portion quoted is the entire argument submitted with respect to

the Houston County case in the government’s brief.

24b

allowed for the inclusion of all grades in the plan. The

dual or biracial school attendance system, i.e., separate

attendance areas, districts or zones for the races, shall

be abolished contemporaneous with the application of

the plan to the respective grades when and as reached

by it. Also, students new to the system must be assigned

on a non-racial basis to grades not reached by the plan.

The order was later amended to conform to subsequent de

cisions of the Fifth Circuit, but freedom of choice was con

tinued as the method of assignment. On June 28, 1968, pe

titioners filed a motion seeking a plan other than freedom

of choice, relying on this Court’s decision in Green v. School

Board of New Kent County, 391 U.S. 430 (1968). On Sep

tember 16, 1968, after a hearing, the court issued an “ in

terim order” calling on the board to reassess its plans.

But freedom of choice remained in effect, and in November

1968 the board affirmed its request that the free choice

method be retained. On June 4, 1969, petitioners again