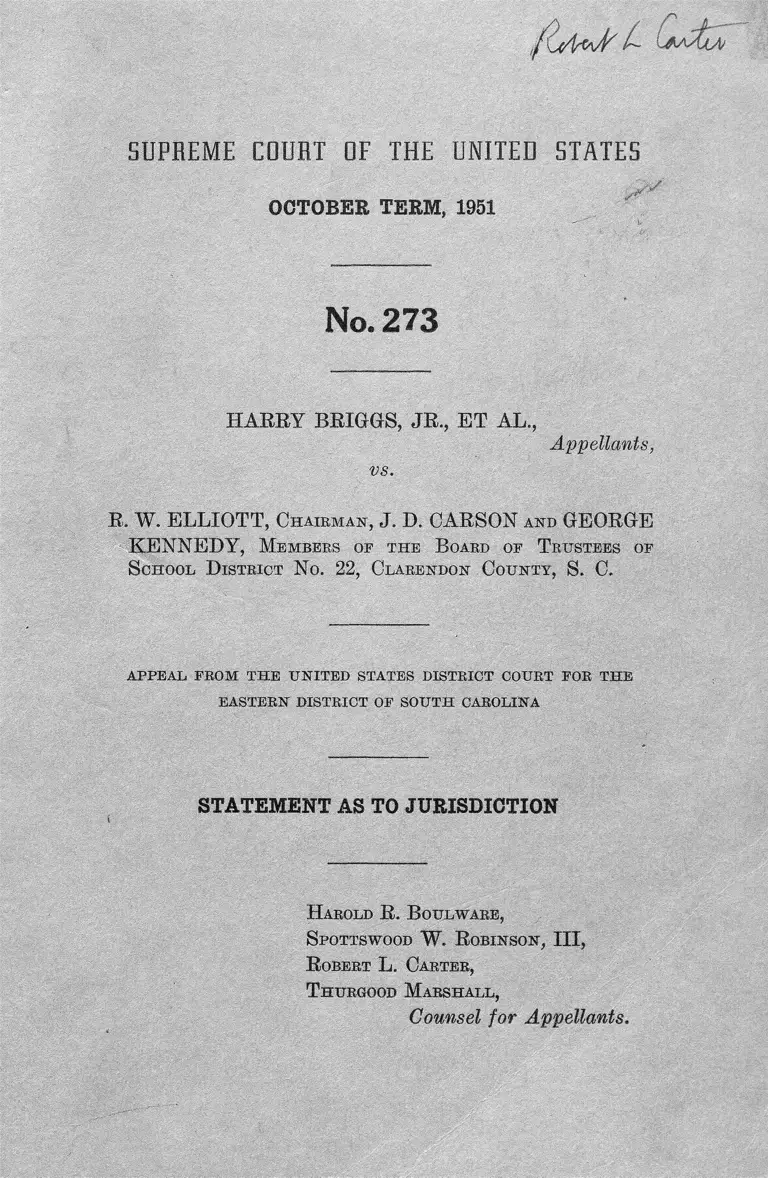

Briggs v. Elliot Statement as to Jurisdiction No. 273

Public Court Documents

July 20, 1951

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Briggs v. Elliot Statement as to Jurisdiction No. 273, 1951. 28f2517b-b69a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/732a36fe-59e1-4c52-9a43-3176c9f33c09/briggs-v-elliot-statement-as-to-jurisdiction-no-273. Accessed February 25, 2026.

Copied!

/ c W - C v f '/ - 'LMytuy

S U P R E M E CO U R T OF TH E U N ITE D S T A T E S

>y

OCTOBER TERM, 1951

No. 273

HARRY BRIGGS, J R , ET A L ,

Appellants,

vs.

R. W. ELLIOTT, C h a ir m a n , J. D. CARSON and GEORGE

KENNEDY, M embers of t h e B oard of T rustees of

S chool D istrict No. 22, C larendon C o u n t y , S . C.

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE

EASTERN DISTRICT OF SOUTH CAROLINA

STATEMENT AS TO JURISDICTION

H arold R . B oulw aee ,

S pottswood W. R obinson , III,

R obert L. Carter ,

T hurgood M arsh all ,

Counsel for Appellants.

INDEX

S u bject I ndex

Page

Statement as to jurisdiction....................................... 1

Opinion below ....................................................... 1

Jurisdiction ........................................................... 1

Statement .............................................................. 4

Constitution and statute involved...................... 7

Questions presented............................................. 8

Statement of the grounds upon which it is con

tended the questions involved are substantial. 8

Summary ....................................................... 8

I. The question whether a state which

undertakes to provide a public

education for its citizens can sat

isfy the requirements of the equal

protection clause of the Four

teenth Amendment by providing

a system of separate public ele

mentary and high school for

negroes and excluding all negroes

from the public schools it pro

vides for all persons is of great

public importance and should be

decided by the supreme Court in

this case .................................... 9

II. Statutory classifications base solely

on race or color violate the Fed

eral Constitution....................... 20

A. Race or color cannot be

made the basis of a statu

tory classification ........... 20

B. There is no reasonable basis

for allocating educational

facilities on the basis of

race .............................. 23

6927

11 INDEX

Page

C. Segregation statutes cannot

be upheld on the basis

that they are necessary

to preserve public peace

and order ...................... 25

III. The majority of the lower court

erred in refusing to follow the

applicable decisions of the Su

preme C ou rt................................ 26

Conclusion ............................................................. 35

Appendix “ A ” —Decree and opinion of the United

States District Court for the Eastern District of

South Carolina.......................................................... 37

Appendix “ B ’ ’—Collection of applicable cases......... 74

T able of C ases C ited

Adamson v. California, 332 U. S. 46............................ 21

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60................................ 25

Carr v. Corning, 182 F. (2d) 14.................................... 11

Cummings v. Board of Education, 175 U. S. 528. ... 27

Eichols v. Public Service Commission, 306 U. S. 268.. 3

Endo, Ex parte, 323 U. S. 282.............................. 21

Fisher v. Hurst, 33 U. S. 147....................................... 28

Gong Lum v. Rice, 275 U. S. 78.................................... 27

Hirabayashi v. U. S., 320 U. S. 81.............................. 20

Korematsu v. U. S., 323 U. S. 214................................ 20, 21

McKissick v. Carmichael, 187 F. (2d) 949................ 29

McLaurin v. Board of Regents, 339 U. S. 637... 3, 4, 9,11, 24

Mayflower Farms v. Ten Eyck, 297 U. S. 266............. 23

Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 U. S. 377....... 11, 28

Nixon v. Herndon, 273 U. S. 536.................................. 20

Oliver, In re, 333 IT. S. 257........................................... 21

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U. S. 537................................ 11

Quaker City Cab Co. v. Penn., 277 U. S. 389............... 23

Rice v. Elmore, 165 F. (2d) 387.................................... 22

Roberts v. City of Boston, 5 Cush. 158........................ 26

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1 .................................. 26

Sipuel v. Board of Regents, 332 U. S. 631................... 11

Skinner v. Oklahoma, 316 IJ. S. 735............................ 23

Southern Railroad Co. v. Green, 216 U. S. 400......... 23

Page

Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U. S. 629.................................. 9,11, 29

Tahahashi v. Fish <& Game Commission, 334 U. S.

410 .............................................................................. 20

Truax v. Raich, 229 U. S. 33........................................ 23

United States v. Carotene Products, 304 U. S. 144. ... 22

Wilson v. Board of Supervisors, 340 U. S. 909............ 4,11

S tatutes C ited

Code of Laws of South. Carolina, Section 5377......... 7

Constitution of South Carolina, Article XI, Sec

tion 7 .......................................................................... 2, 7

Constitution of the United States, 14th Amendment,

21, 22, 26

United States Code, Title 28:

Section 1253 .......................................................... 2, 3

Section 2101b ........................................................ 2, 3

Section 2281 .......................................................... 3, 4

Section 2284 .......................................................... 3, 4

INDEX 111

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE

EASTERN DISTRICT OF SOUTH CAROLINA,

CHARLESTON DIVISION

CIVIL ACTION NO. 2657

HARRY BRIGGS, JR., ET AL.,

Plaintiffs,

R. W. ELLIOTT, C h a ie m a n , ET AL.,

Defendants.

STATEMENT AS TO JURISDICTION

In compliance with Rule 12 of the Rules of the Supreme

Court of the United States, as amended, plaintiffs-appellants

submit herewith their statement particularly disclosing the

basis upon which the Supreme Court has jurisdiction on

appeal to review the judgment of the District Court entered

in this case.

Opinion Below

The opinions of the District Court for the Eastern Dis

trict of South Carolina, Charleston Division, have not yet

been reported. A copy of each of the two opinions and of

the judgment are attached hereto as Appendix A.

Jurisdiction

The judgment of the District Court was entered on June

21, 1951. A petition for appeal is presented to the District

Court herewith, to-wit, on July 20, 1951. The jurisdiction

2

of the Supreme Court to review this decision is conferred

by Title 28, United States Code, sections 1253 and 2101(b).

The complaint in this case was filed by Negro children of

public school age residing in School District No. 22, Claren

don County, South Carolina, and their respective parents

and guardians, against the public school officials of said'

county and school district who, as officers of the State, main

tain, operate and control the public schools for children

residing in said district. It was alleged that defendants

maintained certain public schools for the exclusive use of

white children and certain other public schools for Negro

children; that the schools for Negro children were in all

respects inferior to the schools for white children; that the

defendants excluded the infant plaintiffs from the white

schools pursuant to Article XI, section 7, of the Constitution

of South Carolina, and section 5377 of the Code of Laws of

South Carolina of 1942, which require the segregation of

the races in public schools; and that it was impossible for

the infant plaintiffs to obtain a public school education equal

to that afforded and available to white children as long as

the defendants enforced these laws.

The complaint sought a judgment declaring the invalidity

of these laws as a denial of the equal protection of the laws

secured by the Fourteenth Amendment of the Constitution

of the United States, and an injunction restraining the de

fendants from enforcing them and from making any dis

tinction based upon race or color in the educational oppor

tunities, facilities and advantages afforded public school

children residing in said district.

Defendants in their answer joined issue on this question

and admitted that in obedience to the constitutional and

statutory mandates separate schools were provided for the

children of the white and colored races; and that no child

of either race was permitted to attend a school provided for

3

children of the other race. In the Third Defense of defend

ants ’ answer they alleged that the above constitutional and

statutory provisions were a valid exercise of State’s legis

lative power.

The jurisdiction of a three-judge District Court was

invoked pursuant to Title 28, United States Code, sections

2281, 2284, for the purpose of determining the validity of

the provisions of the Constitution and laws of South Caro

lina requiring segregation of the races in public schools.

This issue was clearly raised, and was decided by uphold

ing the validity of these provisions and by refusing to en

join their enforcement.

The judgment in this case, one judge dissenting, stated

that neither the constitutional nor statutory provisions

requiring segregation in public schools were in violation of

the Fourteenth Amendment and that plaintiffs were not

entitled to an injunction against the enforcement of these

provisions by these defendants. The judgment also stated

that the educational facilities offered infant plaintiffs were

unequal to those offered to white pupils 1 and ordered the

defendants “ to furnish to plaintiffs and other Negro

pupils of said district educational facilities, equipment, cur

ricula and opportunities equal to those furnished white

pupils.”

The decree herein is the type of order which entitles the

plaintiffs-appellants to a direct appeal to the Supreme

Court within the meaning of Title 28, United States Code,

sections 1253 and 2101(b). Eichhols v. Public Service Com

mission, 306 U. S. 268.

The following decisions sustain the jurisdiction of the

Supreme Court to review the judgment in this case: Mc-

1 This was all admitted in open court by the defendants at the outset

of the trial.

4

Laurin v. Board of Regents, 339 U. 8. 637; Wilson v.

Board of Supervisors, 340 U. S. 909.

Statement

At the opening of the trial, before a three-judge District

Court as required by Title 28, United States Code, sections

2281 and 2284, defendants admitted upon the record that

‘ ‘ the educational facilities, equipment, curricula and oppor

tunities afforded in School District No. 22 for colored

pupils # # * are not substantially equal to those afforded

for white pupils.” The defendants also stated that they

did “ not oppose an order finding that inequalities in respect

to buildings, equipment, facilities, curricula, and other

aspects of the schools provided for the white and colored

children of School District No. 22 in Clarendon County

now exist, and enjoining any discrimination in respect

thereto.”

These admissions were made part of the record being

filed as an amendment to the answer. The only issue

remaining to be tried was the question of the constitution

ality of the laws requiring segregation of the races in

public education as applied to the plaintiffs.

During the trial the plaintiffs produced testimony show

ing the extent of the physical inequality in the segregated

schools of Clarendon County and especially School District

No. 22. Over the objection of the plaintiffs2 the defend

ants introduced testimony that a three per cent sales tax

and authorization of a $75,000,000 bond issue for improve

ment of schools had recently been adopted by the State of

South Carolina, and that the State Educational Finance

2 On the grounds that equality within the meaning of the Fourteenth

Amendment did not include contemplated future action.

5

Commission3 to supervise the distribution of these funds

had just been organized and had not even set up rules or

procedures. About a week before the trial Clarendon

County had “ inquired” about making an application for

funds.

The testimony of nine expert witnesses was introduced

by plaintiffs: two experts in the field of education who

offered a comparison of the public schools; one expert in

educational psychology, three experts in the respective

fields of child and social psychology, one expert in political

science, one expert in school administration, and one expert

in the field of anthropology.

The uncontroverted testimony of these witnesses dem

onstrated that the Negro schools in question were inferior

in every material aspect to the white schools, and that sim

ilarly the caliber of education offered to Negro pupils was

inferior to that offered to white pupils. The testimony of

these witnesses also established the fact that the segrega

tion of Negro pupils in these schools would in and of itself

preclude an equality of education offered to white pupils

or pupils in a non-segregated school. These witnesses not

only established their qualifications in their respective fields

but also supported their conclusions by objective and scien

tific authorities.

One of the experts in the field of child and social psychol

ogy testified that he had made special studies of the recog

nized methods of testing the effects of race and segregation

on children. He used a test of this type on Negro school

children including the infant plaintiffs in School District

3 It was admitted that although the school population of South Caro

lina was approximately forty to forty-five per cent Negro there were no

Negroes on the Commission and no Negro employees of the Commission.

6

No. 22 a few days before the trial. From his general expe

rience in this field and the results of his tests he testified:

“ A. The conclusion which I was forced to reach was

that these children in Clarendon County, like other

human beings who are subjected to an obviously infe

rior status in the society in which they live, have been

definitely harmed in the development of their per

sonalities ; that the signs of instability in their personal

ities are clear, and I think that every psychologist

would accept and interpret these signs as such.

‘ ‘ Q. Is that the type of injury which in your opinion

would be enduring or lasting?

“ A. I think it is the kind of injury which would be

as enduring or lasting as the situation endured, chang

ing only in its form and in the way it manifests itself.”

These witnesses testified as to the unreasonableness of

segregation in public education and the lack of scientific

support for such segregation and exclusion. They testified

that all scientists agreed that there are no fundamental

biological differences between white and Negro school

pupils which would justify segregation. An expert in

anthropology testified:

‘ ‘ The conclusion, then to which I come, is differences

in intellectual capacity or inability to learn have not

been shown to exit as between Negroes and whites,

and further, that the results make it very probable

that if such differences are later shown to exist, they

will not prove to be significant for any educational

policy or practice.”

Another expert witness testified:

“ It is my opinion that except in rare cases, a child

who has for 10 or 12 years lived in a community where

legal segregation is practiced, furthermore, in a com

munity where other beliefs and attitudes support racial

discrimination, it is my belief that such a child will

7

probably never recover from whatever harmful effect

racial prejudice and discrimination can wreck. ’ ’

The defendants did not produce a single expert to con

tradict these witnesses. There were only two witnesses

for the defendants. The Superintendent of Schools for

District No. 22 testified as to the reasons for the physical

inequalities between the white and Negro schools. The

Director of the Educational Finance Commission testified as

to the proposed operation of the Commission and the pos

sibility of the defendants obtaining funds to improve public

schools. The latter witness testified that from his experi

ence as a school administrator in Sumter and Columbia,

South Carolina, it would be “ unwise” to remove segrega

tion in public schools in South Carolina. On cross-examin

ation, he admitted he had not made any formal study of

racial tensions but based his conclusion on the fact that

he had “ observed conditions and people in South Carolina”

all of his life. He also admitted that his conclusion was

based in part on the fact that all of his life he had believed

in segregation of the races.

Constitution and Statute Involved

Article XI, section 7 of the Constitution of South Caro

lina provides:

“ Separate schools shall be provided for children of

the white and colored races, and no child of either race

shall ever be permitted to attend a school provided for

children of the other race.”

Section 5377 of the Code of Laws of South Carolina is as

follows:

“ it shall be unlawful for pupils of one race to attend

the schools provided by boards of trustees for persons

of another race.”

8

Questions Presented

1. Whether a State which undertakes to provide a public

education for its citizens can satisfy the requirements of the

equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment of

the Constitution of the United States by providing a system

of separate public elementary and high schools for Negroes

and excluding all Negroes from the schools it provides for

all other persons?

2. Whether the District Court erred in predicating its

decision upon Plessy v. Ferguson, and in disregarding Mc-

Laurin v. Board of Regents and principles serving as the

basis for this and other decisions of the Supreme Court in

conflict with the rationale of the Plessy case?

Statement of the Grounds Upon Which It Is Contended the

Questions Involved Are Substantial

S u m m a r y

The defendants having conceded the physical inequalities

of the segregated schools, the only question remaining in

the case was the validity of the laws requiring the segre

gation and exclusion of the infant plaintiffs from the only

schools where they could obtain an education equal to that

offered all other children. This was the only question which

required the convening of the three-judge court.

The Supreme Court has always recognized the import

ance of racial segregation in public education. Although

the Supreme Court has clarified the issue as to graduate

and professional schools, the Court has never had the

opportunity to consider the question as to elementary and

high schools on the basis of a full and complete record with

the issue clearly drawn and with competent expert testi

mony as appears in the record in this case. A clear cut

decision on this issue will remove all doubts in the field of

public education.

9

The majority opinion of the lower court subordinated

the individual rights of the plaintiffs to the state’s segre

gation policy. It was held that the Federal courts were

powerless to interfere with the statutes of a state segregat

ing Negroes in public education as long as equality of

physical equipment was ordered.

The majority opinion held that the rationale of the

decisions in Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U. S. 629 and McLaurin

v. Board of Regents, 339 U. S. 637 could not be applied

to elementary and high school pupils. Thus, without a

review of this decision there will be considerable doubt in

the minds of judges, school officials, taxpayers and pupils

of the extent of the principles set forth in those decisions.

ARGUMENT

I

The Question Whether a, State Which Undertakes to Provide

a Public Education for Its Citizens Can Satisfy the Re

quirements of the Equal Protection Clause of the Four

teenth Amendment by Providing a System of Separate

Public Elementary and High Schools for Negroes and

Excluding All Negroes from the Schools It Provides for

All Other Persons Is of Great Public Importance and

Should Be Decided by the Supreme Court in This Case.

One of the firmly recognized and established functions

of government is the education of its citizens. In the

United States this function has been undertaken and is

discharged by the individual states which have established

and maintain public educational facilities from the ele

mentary through the graduate and professional school

levels, and require all citizens during the greater period

of their minority to either attend the public schools or

obtain an education privately.

10

Although this responsibility has been assumed by the

states individually, the educational development of the

youth of the Nation is nevertheless a matter of great

national concern which becomes increasingly important.

So also is the practice, current in a broad section of the

country, of affording a dual system of schools and a double

standard of public education based wholly upon the race

or color of the pupils attending.

Racially segregated public schools are legally required

in seventeen southern states4 and the District of Columbia.5

In all but a few of the remaining thirty-one states, segre

gated schools are either unauthorized or are prohibited.6

A

The Supreme Court has recognized the importance of the

issue of racial segregation in the area of public educa

tion in cases involving educational opportunities at the

4 ALA. CONST., Art. XIV, sec. 256; ALA. CODE (1940), Title 52,

sec. 93; ARK. STAT. ANN. (1947), sec. 80-509; DEL. CONST., Art.

X, sec. 2; DEL. REV. CODE (1935), Ch. 71, Art. 1, sec. 2631, Art. V,

sec. 2684; FLA. CONST., Art. 12, sec. 12; FLA. STAT. ANN., sec.

228.09, 230.23; GA. CONST., Art. VIII, sec. 1; GA. CODE ANN. (1947

Cum. Supp.) sec. 32-909, 32-937; KY. CONST., sec. 187; KY. REV.

STAT. (1948), sec. 158.020; LA. CONST. ANN. (Dart 1947 Supp.),

Art. 12, sec. 1; MD. CODE ANN. (1939), Art. 77, sec. I l l , 192 to 193;

MISS. CONST., Art. 8, sec. 207; MISS. CODE ANN. (1942) sec. 6276;

MO. CONST., Art. IX, sec. 1; MO. REV. STAT. (1939) sec. 10349, 10488;

N. C. CONST., Art. IX, sec. 2; N. C. GEN. STAT. (1943), sec. 115-2,

115-3, 115-30, 115-66, 115-97; OKL. CONST., Art. XIII, sec. 3; OKL.

STAT. (Supp. 1949), Title 70, sec. 5-1 to 5-15; S. C. CONST., Art. 11,

sec. 7; S. C. CODE (1942), sec. 5377; TENN. CONST., Art. 11, sec. 12;

TENN. CODE ANN. (Williams 1934) sec. 2377, 2393.9, 11395 to 11397;

TEX. CONST., Art. VII, sec. 7; TEX. ANN. CIV. STAT. (Vernon 1947),

Art. 2755, 2900, 2719, 2819; VA. CONST. Art. IX, sec. 140; VA. CODE

(1950), sec. 22-221; W. VA. CONST., Art. XII, sec. 8; W. VA. CODE

ANN. (1943), sec. 1775, 1777.

5D €. CODE (1940), Title 31, Sec. 1110 to 1113.

6 Reddick, L. D., The Education of Negroes in States Where Separate

Schools Are Not Legal, The Journal of Negro Education, Summer 1947,

Vol. XVI, No. 3, p. 296.

11

graduate and professional school levels.7 The same basic

questions arising at the elementary and secondary levels

are no less important. In fact, the elementary and secon

dary schools and racial segregation obtaining in them,

exert a far greater effect on a far larger number of per

sons at a far more important stage of the person’s life.

This case and Carr v. Corning, 182 F. (2d) 14 (D. C.), are

the only two cases decided in several decades in which a

direct attack was made upon the constitutional validity of

racial segregation in public education at the elementary

and secondary school levels. The importance of the issues

here presented is emphasized by the fact that each of these

two cases was decided by a Federal Court and in each the

validity of such segregation was sustained by the bare

majority of a single vote.

The course of decision taken by the Supreme Court in

recent cases involving segregated public education at the

professional and graduate school levels,8 the strong dis

sents registered in this case9 and in Carr v. Corning,10 the

Supreme Court’s refusal in Sweatt v. Painter11 to reaffirm

the doctrine of Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U. S. 537, and the

weakening and disappearance of that doctrine in other

areas, combine to create serious and widespread question as

to the legality and the duration of segregated public elemen

7 Wilson v. Board of Supervisors, 340 U. S. 909, and McLaurin V.

Board of Regents, 339 U. S. 637, were reviewed on direct appeal. Sweatt

v. Painter, 339 U. S. 629, was reviewed on certiorari. Cf. Sipuel v.

Board of Regents, 332 U. S. 631, and Missouri ex rel. Gaines V. Canada,

305 U. S. 337.

8 Wilson v. Board of Supervisors, 307 U. S. 909; McLaurin v. Board

of Regents, 339 U. S. 637; Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U. S. 629. Cf. Sipuel

v. Board of Regents, 332 U. S. 631; Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada,

305 U. S. 337.

9 Appendix A.

10 182 F. (2d) at 22-35.

u 339 U. S. at 335-336.

12

tary and high schools. This doubt the Supreme Court

should settle by a definitive decision as to whether racial

separation in public elementary and secondary schools is

a constitutionally permissible pattern which may serve to

guide the future endeavors of scholars and school officials.12

B .

Approximately 10,000,000 Negroes, or 77% of all Negroes

in the United States, live in the southern region where a

pattern of educational segregation is sanctioned and en

forced by law. Admittedly, this is the poorest section of

the country. This condition is overwhelmingly due to the

maintenance of segregation and a caste system which rele

gates all Negroes to a position lower than the lowest white.

This is the area of the country least able to afford either

the financial or the educational hazards created by a dual

system of education. As a result, Negroes have been vic

timized throughout the years by grossly discriminatory

practices designed to conserve for whites the maximum

possible benefit of educational resources. The courts in

this area have been faced with a variety of litigation as to

the constitutional validity of such segregation, the defini

tion and determination of the segregated group, the appor

tionment of public funds between the separated school

systems, the provision of facilities, curricula and teachers,

and the numerous other complex problems which such seg

regation has created.13 After more than three-quarters of

12 8 Wash, and Lee L. Rev. 54 (1951) ; 13 Ga. Bar. J. 357 (1951) ; 4

Van. L. Rev. 555 (1951) ; 24 Temple L. Q. 222 (1950) ; 3 U. Fla. L. Rev.

358 (1950); 13 Ga. Bar J. 88 (1950); 36 Va. L. Rev. 797 (1950); 3

So. Car. L. Q. 71 (1950) ; 30 B. U. L. Rev. 565 (1950) ; 1950 Washington

U. L. Q. 594 (1950) ; 24 So. Cal. L. Rev. 74 (1950) ; 17 Brooklyn L. Rev.

134 (1950) ; 30 Neb. L. Rev. 69 (1950) ; 5 Miami L. Rev. 150 (1950) ; 39

Ga. L. J. 145 (1950) ; 26 Notre Dame Law. 81 (1950) ; 26 Notre Dame

Law. 134 (1950); 3 Ala. L. Rev. 181 (1950).

13 See the cases collected in Appendix B.

13

a century of judicial effort to attain an equality of educa

tional opportunity within the framework of racial segrega

tion, the widespread inequalities and discriminations yet

existent demonstrate the futility of such a course.

During the 1944-45 school session, the value of elementary

school property in eight southern states14 was $867,960,280.

Of this sum, $786,662,302 was invested in schools for

3,510,540 white children and $81,297,978 in schools for

1,551,279 Negro children. The per capita value of school

property was $224.08 for white pupils and $52.40 for Negro

pupils. The investment for white pupils was 427.6% more

than the investment for Negro pupils.15 For the same

school session, the average current expenditure in seven

southern states16 was $73.67 per white pupil enrolled and

$32.46 per Negro pupil enrolled. The average expenditure

per white pupil was 227 % greater than the average expendi

ture per Negro pupil.17

For the 1943-44 school session, ten southern states18 spent

$43,448,777 for public school transportation, of which only

$1,349,834, or 3.1% was spent for Negro pupils. The expen

diture was $6.11 per white pupil and only $0.59 per Negro

pupil.19 For the 1944-45 school session, the average salary

paid white teachers in the seventeen southern states and

the District of Columbia was $1,513, and the average paid

14 The eight states: Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Maryland, Mississippi,

North Carolina, South Carolina and Texas.

15 Washington, Availability of Education for Negroes in the Elemen

tary School, The Journal of Negro Education, Howard University Press,

Summer Issue, Vol. XVI, 1947, p. 446.

16 The seven states: Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana,

North Carolina, and South Carolina.

17 Washington, op. cit. supra note 15, at 447.

18 The ten states: Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Maryland,

Mississippi, North Carolina, Oklahoma, South Carolina and Texas.

19 Statistics of State School Systems, 19Jf3-hU, Department of Educa

tion, Government Printing Office, passim.

14

Negro teachers was $1,187.28, a differential of $326.29. The

average salary paid white teachers was 127.5% greater than

the average salary paid Negro teachers.20

Other consequences of public school segregation are sim

ilarly manifested :21 * *

“ In the 17 states and the District of Columbia where

separate schools are maintained by law, some 494,207

(2.8%) of the native whites, and 569,378 (11.7%) of

the Negroes in this age group had not attended school

for even one year; and 2,078,998 (11.6%) of the native

whites and 1,802,770 (37.0%) of the Negroes were func

tional illiterates. In other words, there were four

times as many Negroes as native whites in proportion

to population who had not had at least a year of

schooling; and three times as many Negroes who were

functional illiterates.

# # # # #

“ In the 17 states and the District of Columbia the

median years of schooling for the white population

was 8.4; for Negroes the median was 5.1; with a range

for the whites running from 7.9 in Kentucky to 12.1

in the District of Columbia; and for Negroes from

3.9 in Louisiana to 7.6 in the District of Columbia.

Some 13.2 per cent of the white population had com

pleted four years of high school as compared with

only 2.9 per cent of the Negroes; 12.1 per cent of the

whites had had some college education, as compared

with only 2.5 per cent of the Negroes; and 4.7 per cent

of the white population had had four or more years of

college as contrasted with only 1.1 per cent of the

Negroes. There were, therefore, four times as many

whites as Negroes with a high school or college edu

20 Statistics of State School Systems, 19U3-19UU, Department of Educa

tion, Government Printing' Office, passim; “ The Journal of Negro Educa

tion, Howard University Press, Vol. XVI, Summer 1947, passim.

21 Thompson, The Availability of Education in the Negro Separate

School, The Journal of Negro Education, Howard University Press, Vol.

XIV, Summer 1947, p. 264.

15

cation in these states which require racial segregation

by law. ’ ’

Though in much smaller degree, whites as well as Ne

groes suffer from lowered educational standards. As it has

been authoritatively reported.22

“ Segregation lessens the quality of education for

the whites as well. To maintain two school systems

side by side—duplicating even inadequately the build

ings, equipment, and teaching personnel—means that

neither can be of the quality that would be possible

if all the available resources were devoted to one sys

tem, especially when the States least able financially

to support an adequate educational program for their

youth are the very ones that are trying to carry a

double load.”

The adverse effects of racial segregation in public edu

cation are not confined to the minority group or to the

local community. The whole nation suffers from the under

development of a vast segment of its human resources. In

the most critical period of June-July, 1943, when the nation

was crying for manpower, 34.5% of the rejections of Negroes

from the armed forces were for educational deficiency.

Only 8% of the white selectees rejected for military service

failed to meet the educational standards.23 The official

War Department report on the utilization of Negro man

power in the postwar Army says that “ in the placement of

men who were accepted, the Army encountered considerable

difficulty. Leadership qualities had not been developed

among the Negroes, due principally to environment and * 28

22 Higher Education for American Democracy, Report of the Presi

dent’s Commission on Higher Education, Government Printing Office,

Washington, D. C., 1947, Vol. I, p. 34.

28 The Black and White of Rejections for Military Service, Montgom

ery, Ala., American Teachers Association, 1944, p. 5.

16

lack of opportunity. These factors had also affected devel

opment in the various skills and crafts.” 24

C

The record in this case incontrovertibly demonstrates

that the segregated school irreparably harms the pupil.

Unlike many forms of racial segregation, where the citizen

may by exercise of his own will either encounter or avoid

the situations of which segregation is a part, he has little

freedom of choice in this area. The legal alternatives to a

public school education usually being economically unavail

able, he is forced by compulsory school attendance laws to

go to the segregated schools and there be subjected to the

evils which segregation invariably produces.

State ordained segregation is a particularly invidious

policy which needlessly penalizes Negroes, demoralizes

whites and tends to disrupt our democratic institutions.

Segregation prevents both the Negro and white pupil

from obtaining a full knowledge and understanding of the

group from which he is separated. It has been scientific

ally established that no child at birth possesses either an

instinct or even a propensity toward feelings of prejudice

or superiority. These prejudices, when and if they do

appear, are but reflections of the attitudes and institutional

ideas evidenced by the adults about him.25 26 * The very act of

segregation tends to crystallize and perpetuate group isola

tion, and therefore serves as a breeding ground for

unhealthy attitudes.28

24 Report of Board of Officers on Utilization of Negro Manpower in

the Post-War Army (February, 1946), p. 2.

25 Park, The Basis of Prejudice, The American Negro, the Annals,

Vol. 140, pages 11-20 as cited by Frazier, The Negro in the United

States (1949), at 668; Faris, The Nature of Human Nature, 354, chap

ter on The Natural History of Race Prejudice (1937).

26 Laster, Race Attitudes in Children, 48 (1949); Ware, The Role of

the Schools in Education for Racial Understanding, 13, The Journal of

17

A feeling of distrust for the minority group is fostered

in the community at large—a psychological atmosphere

which is most unfavorable to the acquisition of a proper

education. This atmosphere, in turn, tends to accentuate

imagined differences between Negroes and whites.* 27

Qualified educators, social scientists, and other experts

have expressed their realization of the fact that “ separate”

is irreconcilable with “ equality.” 28 There can be no

equality since the very fact of segregation establishes a

feeling of humiliation and deprivation to the group con

sidered inferior.29

Probably the most irrevocable and deleterious effect of

segregation upon the minority group is that it imposes a

badge of inferior status upon the segregated group.30 This

Negro Education (1944) ; Moten, What the Negro Thinks (1929) ; Long,

Psychogenic Hazards of Segregated Education of Negroes, 4 The Jour

nal of Negro Education, 343 (1935). For an exhaustive study relating

to the reaction, of Negroes to discrimination and how their reactions

affect their relations with whites, see Rose, The Negro’s Morale: Group

Identification and Protest (1949) ; Johnson, Patterns of Segregation, II,

Behavior Response of Negroes to Segregation and Discrimination (1943).

27 Murdal, An American Dilemma, 625 (1944) ; “ But they are isolated

from the main body of whites, and mutual ignorance helps reinforce

segregative attitudes and other forms of race prejudice.”

28 Id. at page 580; Johnson, op. cit. supra note 26, at 4, 318; Mangurn,

The Legal Status of the Negro (1947) ; Report of the President’s Com

mittee on Civil Rights, To Secure These Rights (1947) ; Report of the

President’s Commission on Higher Education, Higher Education for

American Democracy, (1947) ; Deucher and Chein, The Psychological

Effects of Enforced Segregation: A Survey of Social Opinion, 26 Journal

of Psychology 259-287 (1948).

29 McWilliams, Race Discrimination and the Law, 9 Science and So

ciety No. 1 (1945) ; 56 Yale L. J. 1051, 1052, 1059 (1947) ; Bond, Educa

tion, Education of the Negro in the American Social Order, 385 (1934) ;

Moton, op. cit. supra note 26, at 99; Bunche, Education in Black and

White, 5 Journal of Negro Education 351 (1936) ; Long, op. cit. supra

note 26, at 336-343; Henrich, The Psychology of Suppressed People, 52

(1937) ; Dollard, Caste and Color in a Southern Town, 269 441 (1937) ;

Young, America’s Minority Peoples, 585 (1932).

30 Smythe, The Concept of “Jim Crow,” 27 Social Forces 48 (1948):

“ ‘Jim Crow’ as used in a sociological context thus indicates for a specific

18

badge of inferior status is recognized not only by the minor

ity group, but by society at large.* 31 A definitive study of

the scientific works of contemporary sociologists, historians

and anthropologists conclusively documents the proposition

that the intent and result of segregation are the establish

ment of an inferiority status. And a necessary corollary

to the establishment of this value judgment is the depriva

tion suffered by both the minority and majority groups.32

social group the Negro’s awareness of his badge of inequality which he

learns through the operation of a ‘Jim Crow’ concept in his every day

living. This pattern of existence has become so much a part of the

nation’s social structure that it has become synonymous with the words

‘segregation’ and ‘discrimination’ and at times when ‘Jim Crow’ is

indexed some authors have indexed it as a cross reference for these

terms.”

31 Myrdal, op. cit. supra note 27, at 643. “ Segregation and discrim

ination have had material and moral effects on whites, too. Booker T.

Washington’s famous remark, that the white man could not hold the

Negro in the gutter without getting in there himself, has been corrob

orated by many white Southern and Northern observers. Throughout

this book we have been forced to notice the low economic, political, legal

and moral standards of Southern whites—kept low because of discrim

ination against Negroes and because of obsession with the Negro prob

lem. Even the ambition of Southern whites is stifled partly because,

without rising far, it is so easy to remain ‘superior’ to the held-down

Negroes * * * ”

32 Baruch, Glass House of Prejudice, 66-76 (1946); Gallagher, Ameri

can Caste and the Negro College 94 (1938); Wherever possible, the

caste line is to keep all Negroes below the level of the lowest whites.

This is the first and deepest meaning of “ separate but equal” . Page 105:

“ Not the least important aspect of the caste system is its results in

seriously malconditioning the individuals whose psychological growth is

strongly affected by a caste divided society. These influences are not

limited to the Negro caste. They stamp themselves upon the dominant

caste as well” ; La Farge, The Race Question and the Negro 159 (1945) :

“ Segregation, as a compulsory measure based on race, imputes essen

tial inferiority to the segregated group. Segregation, since it creates

a ghetto, brings in the majority of instances, for the segregated group,

a diminished degree of participation in those matters which are ordi

nary human rights, such as proper housing, educational facilities, police

protection, legal justice, employment, * * * Hence it works objective

injustice. So normal is the result for the individual that the result is

rightly termed inevitable for the group at large” ; James, The Philos-

19

D

The unanimous conclusion of scholars and students who

have studied the problem is that racial segregation in public

education must be eliminated.

Recognizing that segregation constitutes a menace to

American freedom and is indefensible, the President’s Com

mittee on Civil Rights unequivocally recommended its

elimination from American life : 33

“ The separate but equal doctrine has failed in three

important respects. First, it is inconsistent with the

fundamental equalitarianism of the American way of

life in that it marks groups with the brand of inferior

status, Secondly, where it has been followed, the results

have been separate and unequal facilities for minority

peoples. Finally, it has kept people apart despite in

controvertible evidence that an environment favorable

to civil rights is fostered whenever groups are per

mitted to live and work together.”

ophy of William James 128 (1925) ; “ Properly speaking, a man has as

many social selves as there are individuals who recognize him and carry

an image of Mm in their mind. To wound any one of these images is

to wound him” ; Loeseher, The Protestant Church and the Negro (1948) ;

“ (Segregation) is, in itself, an implication of inferiority, an inferiority

not only of status but of essence, of being” ; Thompson, “ Mis-Edueation

for Americans” ; 36 Survey Graphic 119 (1947) : “ Education for segre

gation, if it is to be effective must perpetuate beliefs which define the

Negro’s status as inferior, which emphasize superficial differences,

or which in any way suggest that the Negro is a lower order of being

and therefore should not be expected to be treated like a white person.”

Page 120: “ Mis-education for segregation has deleterious effects on both

Negroes and whites. It requires mental and emotional gymnastics on

both sides to adjust (or attempt to adjust) to the many logical and

ethical contradictions of segregation. The situation is crippling to the

personalities of both Negro and white Americans.”

83 Report of the President’s Commission on Civil Rights, To Secure

These Rights, U. S. Government Printing Office, 1947, p. 166.

20

Likewise, the President’s Commission on Higher Educa

tion, in its report on education in the United States, said :34

“ The time has come to make public education at all

levels equally accessible to all, without regard to race,

creed, sex or national origin.”

II

Statutory Classifications Based Solely on Race or Color

Violate the Federal Constitution

A

R ace or C olor Can n o t B e M ade th e B asis oe a S tatutory

Classification

In South Carolina, the school in District No. 22 which a

child is permitted to attend depends solely upon his race or

color. The Supreme Court, in recent decisions, has indi

cated that statutes which affect individuals according to

their race or ancestry are, in the absence of an overwhelm

ing public necessity, invalid. Takahashi v. Fish & Game

Commission, 334 U. S. 410; Korematsu v. United States,

323 U. S. 214; and Hirabayashi v. United States, 320 U. S.

81, wherein the Court said:

“ Distinctions between citizens solely because of their

ancestry are by their very nature odious to a free peo

ple whose institutions are founded upon the doctrine

of equality. For that reason, legislative classification

. . . based on race alone has often been held to be a

denial of equal protection.” (p. 100)

In Nixon v. Herndon, 273 U. S. 536, Mr. Justice Holmes

34 Report of the President’s Commission on Higher Education, Higher

Education for American Democracy, U. S. Government Printing Of

fice, 1947, p. 38.

21

stated for the Court that statutory classifications can never

be based on color:

“ States may do a great deal of classifying that it is

difficult to believe rational, but there are limits, and

it is . . . clear . . . that color cannot be made the basis

of a statutory classification.” (p. 541)

The above decisions have been made without regard to

the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment,

thus indicating that the citizen’s right to have his rights,

obligations, and duties to the state determined without

regard to his race or color is a fundamental right essential

to our democratic society.35 State statutes must in addition

35 It might be argued by the proponents of segregated school systems

that since seventeen states have laws which regulate the use of some

or all of the public educational facilities on the basis of race or color,

the problem is essentially one for the legislative judgment and that

federal courts should not interfere. The proponents might attempt to

place reliance on the Supreme Court’s examination on several occasions

of the practices and experiences of the forty-eight states and other

jurisdictions which have adopted Anglo-American jurisprudence, to see

whether a right being claimed as fundamental is generally protected

by the states. See for example, Adamson v. California, 332 U. S. 46;

In Re Oliver, 333 U. S. 257. But such examination in the instant case

is not at all relevant, and, in any event, if made, would have to exclude

those states which have a history of unequal treatment to Negroes in

educational facilities, political franchise, and other opportunities and

rights normally available to citizens of a state.

In the first place, the Court has already indicated that governmental

classifications based upon race and color are arbitrary and a denial of

due process of law. Korematsu v. United States, 323 U. S. 214; Ex

Parte Endo, 323 U. S. 282. These cases were under due process clause

of the Fifth Amendment, but certainly “ it ought not to require argu

ment to reject the notion that due process of law meant one thing in the

Fifth Amendment and another in the Fourteenth.” Adamson v. Califor

nia, supra, at 59.

Secondly, the plaintiff claims protection under the equal protection

clause of the Fourteenth Amendment and, as indicated above, the in

tention of this clause was to afford the same rights to Negroes as were

afforded to whites by a state.

Finally, the experiences in the southern states in determining whether

the right to be free of laws imposing burdens or denying privileges based

22

meet the standards of the equal protection clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment. An examination of the relevant

data, including the legislative history, supports plaintiffs’

contention that the purpose of the framers of the Fourteenth

Amendment in including therein the equal protection clause

was to require state action affecting Negroes to be meas

ured by whether white persons were being afforded the

same right, privilege or advantage which the state was

denying to Negroes. In othqr words, if a particular state

affords to its white citizens a particular right or privilege,.

the equal protection clause requires that the same right be

upon race or ancestry is fundamental to a free society, must be dis

counted in determining- the meaning of the Fourteenth Amendment. In

the first place, those states which have traditions and practices similar

to South Carolina in enforcing racial discrimination refused, in 1866

and 1867, to ratify the Fourteenth Amendment. Therefore, their prac

tice and conduct thereunder is not valid evidence as to the meaning or

scope of the Amendment which they have consistently opposed. See

Fairman & Morrison, Does The Fourteenth Amendment Incorporate The

Bill of Rights? 2 Stanford L. Rev. 5, 90-95 (1949) South Carolina

has had a long history, culminating in the events which led to the deci

sion in Rice v. Elmore, 165 F. (2d) 387 (CCA 4 1947), cert, denied

333 U. S. 875, in denying to its Negro citizens the right to exercise

effectively their voting rights specifically guaranteed by the Fifteenth

Amendment. The basis of the argument that matters are within the

legislative judgment and therefore if a person wishes to change a

particular legislation his arguments embodying economic, psychological

and social data should be addressed to the legislature rather than to

the Court necessarily presupposes that the legislature is subject to

the popular will by use of the ballot. In a state such as South Carolina,

this right has not been, and presently is not, freely available to Negroes,

since state officials for many years have attempted to use various means,

most of them already declared illegal by the Supreme Court, to prevent

the free exercise of the ballot. Moreover, the only way that a group is

able to persuade other groups that laws affect them unjustly or are

injurious to the whole society is through discussion with the other

groups. But racial segregation laws usually create conditions which

tend to prevent the normal processes essential to free and democratic

associations from operating and therefore those processes that ordinarily

might be relied upon to protect individuals against arbitrary and un

reasonable governmental action are absent. See United States V. Caro

tene Products, 304 IJ, S. 144, footnote 4,

23

granted to Negro citizens on the same basis. See Fairman

& Morrison, Does The Fourteenth Amendment Incorporate

The Bill of Rightsf 2 Stanford L. Rev. 5, 138-139 (1949).

Thus, even if there is a rational basis for the racial classi

fication used by South Carolina to determine whether chil

dren should go to one school or another in District No. 22,

the, statute is necessarily unconstitutional.

B

T here Is No R easonable B asis for A llocating E ducational

F acilities on th e B asis of R ace

The South Carolina statute prohibiting Negro children

from attending the schools set aside for white children has

no rational basis, and in fact has injurious effects and pre

vents the accomplishments of the very end of public educa

tion. Even wbyn dealing with legislation involving economic

matters, where the Court has permitted certain classifica

tions resulting in distinctions and burdens on one group

and benefits to another, the Court has demanded that there

be some cognate relationship between the classification and

the end sought to be accomplished, and where the differences

are not reasonably perceptible, or are irrelevant to the

legislative end, the classifications, even in economic mat

ters, have been held to violate the equal protection clause.

Quaker City Cab Co. v. Penn., 277 IT. S. 389; Southern Rail

road Co. v. Green, 216 U. S. 400; Mayflower Farms v. Ten

Eyck, 297 IT. S. 266. Where the legislation attempts to

regulate personal rights, the test applied by the Court has

been more stringent. See Truax v. Raich, 229 U. S. 33;

Skinner v. Oklahoma, 316 U. S. 735.

The South Carolina segregation statute is invalid even

under the more lenient standard, since there is no reason

able connection between race and the educational aims

24

sought to be achieved by a state in providing public educa

tion. The purpose of public education is to bring about a

more intelligent citizenry and to develop individuals for

democratic living. Laws which attempt to divide groups

for public school purposes, according to race, religion or

ancestry are at odds with the democratic ideals to which

this nation is committed.

“ The public school is at once the symbol of our

democracy and the most persuasive means for promot

ing our common destiny. In no activity of the State

is it more vital to keep out diversive forces than in the

schools. . . . ” Mr. Justice Frankfurter concurring in

-McCollum v. Board of Education, 332 U. S. 203, 212, 231.

Moreover, there is testimony in the record, not controverted

by South Carolina, that the effect of a segregated school

system is to make the white children feel superior and the

Negro children feel inferior. The rigid pattern of segrega

tion also prevents the voluntary association fostering intel

lectual commingling of people, which the Court has held

is a constitutional right. In McLaurin v. State Board of

Regents, 339 IT. S. 637, speaking for a unanimous court,

Mr. Chief Justice Vinson stated:

“ There is a vast difference—a Constitutional differ

ence—between restrictions imposed by the state which

prohibit the intellectual commingling of students, and

the refusal of individuals to commingle where the state

presents no such bar.”

South Carolina did not and cannot defend its legislation

on the basis that race somehow affected the ability to receive

education, or to achieve any of the ends of education.

Indeed, the plaintiffs introduced evidence to show that

race and color of skin were completely irrelevant. The

evidence is in accordance with all the scientific investiga

tions on the subject, Eose, America Divided: Minority

25

Group Relations in the United States (1948); Montague,

Man’s Most Dangerous Myth—The Fallacy of Race, 188

(1945); American Teachers Association, The Black & White

of Rejections for Military Service 5 (1944) at 29; Klineberg,

Negro Intelligence and Selective Migration (1935); Peter

son & Lanier, Studies in the Comparative Abilities of Whites

and Negroes, Mental Measurement Monograph (1929);

Clark, Negro Children, Educational Research Bulletin

(1923); Klineberg, Race Differences, 343 (1935).

C

S egregation S tatutes Can n o t B e U ph eld on t h e B asis

T h a t T h e y A re N ecessary to P reserve P ublic

P eace and Order

The court below attempted to justify the South Carolina

segregated school system on the basis that otherwise there

might be breaches of public order and that the segregated

pattern had been existing in South Carolina for over one

hundred years. The fact that for one hundred years or

more constitutional rights of a large part of the citizens of

South Carolina have been violated is no basis for defend

ing the continuance of the violation. It has been repeatedly

held by the Supreme Court that the other reason offered

by the lower court—preservation of public order—does not

afford a justification for the application of segregation

statutes. In Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60, the State

of Kentucky attempted to define the ordinance segregating

whites and Negroes into separate racial areas on the ground

that otherwise riots and disorder might result. The

Supreme Court summarily dismissed such an argument with

this statement:

“ It is urged that this proposed segregation will pro

mote the public peace by preventing race conflicts.

26

Desirable as this is, and important as is the preserva

tion of the public peace, this aim cannot be accom

plished by laws or ordinances which deny rights created

or protected by the Federal Constitution.” (p. 81)

The Supreme Court recently reaffirmed the principle that

the preservation of public peace and good order does not

suffice to clothe with constitutionality government action

which results in classification based upon race. Shelley v.

Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1.

Ill

The Majority of the Lower Court Erred in Refusing to

Follow the Applicable Decisions of the Supreme Court

Judicial expositions sustaining the constitutional validity

of the “ separate but equal” theory of public education rest

principally upon the decision of the Supreme Court in

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U. S. 537, and cases which without

critical analysis have applied its doctrine in the area of

public education.

In Plessy v. Ferguson, supra, the majority of the Supreme

Court held that the application to an intrastate passenger

of a Louisiana statute requiring the segregation of white

and Negro passengers did not violate the Fourteenth

Amendment. The case was decided upon pleadings which

assumed the possibility of attainment of a theoretical equal

ity within the framework of racial segregation rather than

on a full hearing and evidence which would have established

the inevitability of discrimination under a system of segre

gation. The majority opinion discussed and relied on Rob

erts v. City of Boston, 5 Cush. (Mass.) 158, which was

decided almost twenty years before the adoption of the

Fourteenth Amendment. This Amendment was designed

and intended to settle the very diversity of opinion,—so

pronounced in 1849 when the Roberts case, supra, was

27

decided—as to the reasonableness of legal distinctions based

on race or color. The famous dissenting opinion of Mr.

Justice Harlan in the Plessy case, supra, stood as a chal

lenge to the majority conclusion even when its position in

the law seemed firmly secure, and time and experience have

demonstrated the falsity of the antebellum justifications

urged in the Roberts case, supra, and of the bases suggested

by the majority of the Court in the Plessy case, supra.

In neither of the two decisions of the Supreme Court

relating to racial segregation in public elementary or high

schools lias the holding in Plessy v. Ferguson, supra, been

reexamined or seriously challenged. In Cummings v. Board

of Education, 175 U. S. 528, suit was brought. principally

to obtain an injunction against continued operation of a

white high school on the ground that no school was being

operated for Negroes similarly situated. The Court’s deci

sion established the impropriety of the remedy invoked

and denied the relief sought. The validity of segregation

was not in issue; plaintiffs not only did not raise such

issue, but acquiesced in the use of taxes levied to support

segregated schools at the elementary and intermediate

grammar school levels. In Gong Lum v. Rice, 275 U. S. 78,

the plaintiff, a child of Chinese descent, asserted a right not

to be classified for school purposes as a colored person

and required to attend the Negro school. The validity of

racial segregation in the public schools there involved was

not raised by the plaintiff who, rather, affirmed its validity

and insisted upon being classified as white and admitted

to a white school.36 86

86 It is true that Mr. Chief Justice Taft, in discussing- the issue, said:

“ Were this a new question it would call for very full argument and

consideration, but we think that it is the same question which has been

many times decided to be within the constitutional power of the State

Legislature to settle without intervention of the Federal Courts under

the Federal Constitution.” (275 U.S. at 85) Therefore, even if this

The decisions of the Supreme Court in the area of grad

uate and professional education have not supported the

doctrine of the Plessy case, supra. In Missouri ex rel

Gaines v. Canada, 305 U. S. 337, the only question involved

was whether a qualified Negro applicant could be excluded

from the only state-supported law school and exiled to

another state to receive a legal education. In holding in

the negative, the Court, while repeating the doctrine of

Plessy v. Ferguson, supra, neither examined nor applied it.

In Sipuel v. Board of Regents, supra, where the Court held

that a Negro applicant was entitled to receive a legal edu

cation within the state as soon as it was afforded to appli

cants of any other group, the doctrine of Plessy v. Ferguson,

supra, was neither raised, examined, repeated nor applied.

In Fisher v. Hurst, 333 U. S. 147, the same case, supra, the

Court denied an original writ of mandamus to compel com

pliance with its mandate by admission to the state’s law

school on the grounds that the original Sipuel case had

specifically not raised the issue of the validity of the segre

gation statutes and that procedurally the question could

not be considered on the petition for writ of mandamus.

The majority opinion of the District Court in this case

upheld the validity of the provisions of the Constitution

and Laws of South Carolina requiring segregation of the

races on the following grounds: (1) segregation of the races

in public schools “ so long as equality of rights is preserved

is a matter of legislative policy for the several states, with

which the federal courts are powerless to interfere.”

(italics ours); (2) subject to the observance of the funda

mental rights and liberties guaranteed by the Federal Con

stitution, each state is free to determine howr it shall exer-

decision is construed as raising the issue of the validity of school segre

gation statutes, it is clear that the doctrine was not examined and that

Plessy v. Ferguson, supra, was relied upon without question.

29

cise its police power, i.e., the power to legislate with respect

to the safety, morale, health and general welfare; (3) the

decisions in Plessy v. Ferguson, supra, Cummings v. Board

of Education, supra, and Gong Lum v. Rice, supra, hold

that as long as equality is furnished, segregation of the

races in public schools is not unconstitutional and these

cases are controlling in the instant case; (4) that neither

Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U. S. 629, McLaurin v. Oklahoma

State Regents, supra, nor McKissick v. Carmichael, 187 F.

2d 949, can be applied to this case because the Siveatt case,

supra, did not overrule Plessy v. Ferguson, supra, and both

the Sweatt case, supra, and the McKissick case, supra, were

decided on the question of equality, and the McLaurin case,

supra, “ involved humiliating and embarrassing treatment

of a Negro graduate student to which no one should have

been required to submit. Nothing of the sort is involved

here” ; (5) there is a difference between education on the

graduate level and on lower levels of education.

The majority opinion held that the Siveatt case, supra,

did not apply to this case because the decision in the Sweatt

case, supra, was based upon the inequality of the “ educa

tional facilities” offered the w'hite and Negro law students.

The opinion also held that: “ McLaurin v. Oklahoma State

Regents involved humiliating and embarrassing treatment

of a Negro graduate student to which no one should have

been required to submit. Nothing of the sort is involved

here. ’ ’ To the contrary, the record in this case shows that

the injury to the plaintiffs in this case was not only humili

ating and embarrassing but was even more harmful than in

graduate education. The uncontradicted testimony in this

record brings this case clearly within the rationale of the

McLaurin case, supra.

Dr. Kenneth Clark, an expert in the fields of social and

30

child psychology who tested the infant plaintiffs and other

Negro school children in District No. 22, testified:

“ A. The conclusion which I was forced to reach was

that these children in Clarendon County, like other

human beings who are subjected to an obviously infe

rior status in the society in which they live, have been

definitely harmed in the development of their person

alities ; that the signs of instability in their personalities

are clear, and I think that every psychologist would

accept and interpret these signs as such.

“ Q. Is that the type of injury which in your opinion

would be enduring or lasting!

“ A. I think it is the kind of injury which would be

as enduring or lasting as the situation endured, chang

ing only in its form and in the way it manifests itself.”

Dr. David Krech, another psychologist, testified:

“ • . . Legal segregation, because it is legal, because

it is obvious to everyone, gives what we call in our

lingo environmental support for the belief that Negroes

are in some way different from and inferior to white

people, and that in turn, of course, supports and

strengthens beliefs of racial differences, of racial infe

riority. I would say that legal segregation is both an

effect, a consequence of racial prejudice, and in turn

a cause of continued racial prejudice, and insofar as

racial prejudice has these harmful effects on the per

sonality of the individuals, on his ability to earn a

livelihood, even on his ability to receive adequate medi

cal attention, I look at legal segregation as an extremely

important contributing factor. May I add one more

point. Legal segregation of the educational system

starts this process of differentiating the Negro from

the white at a most crucial age. Children, when they

are beginning to form their views of the world, begin

ning to form their perceptions of people, at the very

crucial age they are immediately put into the situation

which demands of them, legally, practically, that they

see Negroes as somehow of a different group, different

31

being, than whites. For these reasons and many others,

I base my statement.

“ Q. These injuries that you say come from legal

segregation, does the child grow out of them! Do

you think they will be enduring, or is it merely a sort

of temporary thing that he can shake off!

“ A. It is my opinion that except in rare cases, a

child who has for 10 or 12 years lived in a community

where legal segregation is practiced, furthermore, in

a community where other beliefs and attitudes support

racial discrimination, it is my belief that such a child

will probably never recover from whatever harmful

effect racial prejudice and discrimination can wreck.”

Dr. Harold McNalley, an expert in the field of Educa

tional Psychology, testified:

” . . . And, secondly, that there is basically implied

in the separation—the two groups in this case of Negro

and White—that there is some difference in the two

groups which does not make it feasible for them to

be educated together, which I would hold to be untrue.

Furthermore, by separating the two groups, there is

implied a stigma on at least one of them. And, I think

that that would probably be pretty generally conceded.

We thereby relegate one group to the status of more

or less second-class citizens. Now, it seems to me

that if that is true—and I believe it is—that it would

be impossible to provide equal facilities as long as one

legally accepts them.

” Q. I see. Now, all of the items that you talked

about that you based your reason for reaching your

conclusion, you consider them to be important phases

in the educational process!

“ A. Very much so.”

Dr. Louis Kesselman, a political scientist, testified:

“ I think that I do. My particular interest in the

field of Political Science is citizenship and the Politi

cal processes. And, based upon studies which we

32

regard as being scientifically accurate by virtue of

use of the scientific methods, we have come to feel that

a number of things result from segregation which are

not desirable from the standpoint of good citizenship;

that the segregation of white and Negro students in

the schools prevents them from gaining an understand

ing of the needs and interests of both groups. Sec

ondly, segregation breeds suspicion and distrust in

the absence of a knowledge of the other group. And,

thirdly, where segregation is enforced by law, it may

even breed distrust to the point of conflict. Now, carry

ing that over into the field of citizenship, when a com

munity is faced with problems which every community

would be faced with, it will need the combined efforts

of all citizens to solve those problems. Where segre

gation exists as a pattern in education, it makes that

cooperation more difficult. Next, in terms of voting

and participating in the electorial process, our various

studies^indicate that these people who are low in literacy

and low in experience with other groups are not likely

to participate as fully as those who have . . . ”

Mrs. Helen Trager, a child psychologist who had con

ducted tests of the effects of racial segregation and racial

tensions among children, testified: '

“ Q- Mrs. Trager, in your opinion, could these

injuries under any circumstances ever be corrected in

a segregated school?

“ A. I think not, for the same reasons that Dr. Krech

gave. Segregation is a symbol of, a perpetuator of,

prejudice. It also stigmatizes children who are forced

to go there. The forced separation has an effect on

personality and one’s evaluation of one’s self, which

is inter-related to one’s evaluation of one’s group.”

Dr. Robert Bedfield, an expert in the field of anthropol

ogy, testified as to the unreasonableness of racial classifi

cation in education:

“ Q. As a result of your studies that you have made,

the training that you have had in your specialized field

over some 20 years, given a similar learning situation,

what, if any differences, is there between the accom

plishment of a white and a negro student, given a

similar learning situation?

“ A. I understand, if I may say so, a similar learn

ing situation to include a similar degree of preparation!

“ Q. Yes.

“ A. Then I would say that my conclusion is that

the one does as well as the other on the average.”

The opinion and decree of the majority of the lower court

was based upon the assumption that equality of rights

guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment was limited to

physical equality such as facilities, equipment and curricula.

Expert witnesses for plaintiffs testified not only as to the

inevitable harmful effect of segregation on public school

children but also of the tests showing the irreparable harm

to the plaintiffs and other Negro school children in Claren

don County. This testimony was disposed of in the major

ity opinion as follows:

“ There is testimony to the effect that mixed schools

will give better education and a better understanding

of the community in which the child is to live than

segregated schools. There is testimony, on the other

hand, that mixed schools will result in racial friction

and tension and that the only practical way of conduct

ing public education in South Carolina is with segre

gated schools. The questions thus presented are not

questions of constitutional right but of legislative pol

icy, which must be formulated, not in vacuo or with

doctrinaire disregard of existing conditions, but in

realistic approach to the situations to which it is to be

34

applied. In some states, the legislatures may well

decide that segregation in public schools should be

abolished, in others that it should be maintained—•

all depending upon the relationships existing between

the races and the tensions likely to be produced by

an attempt to educate the children of the two races

together in the same schools. The federal courts would

be going far outside their constitutional function were

they To attempt to prescribe educational policies for

the states in such matters, however desirable such poli

cies might be in the opinion of some sociologists or

educators. For the federal courts to do so would

result, not only interference with local affairs by an

agency of the federal government, but also in the sub

stitution of the judicial for the legislative process in

what is essentially a legislative matter.”

The testimony on behalf of the plaintiffs was by expert

witnesses of unimpeachable qualifications. The record in

this case presents for the first time in any case competent

testimony of the permanent injury to Negro elementary

and high school children forced to attend segregated

schools. Testimony was introduced showing the irrepa

rable damage done to the plaintiffs in this case solely by

reason of racial segregation. The record also shows the

unreasonableness of this racial classification. This is not

theory or legislative argument. This is competent expert

testimony from recognized scientists directed toward the

factors recognized by the Supreme Court as determinative

of the validity of similar statutory provisions. This testi

mony stands uncontradicted in the record.

The Supreme Court in the McLaurin case, supra, refused

to apply the separate but equal doctrine to a case where,

despite complete equality of physical facilities for educa

tion, the State of Oklahoma “ sets McLaurin apart from

the other students.” (339 U. S. 641) On the other hand

the Supreme Court stated: “ The result is that appellant

35

is handicapped in his pursuit of effective graduate instruc

tion. Such restrictions impair and inhibit his ability to

study, to engage in discussions and exchange views with

other students, and, in general, to learn his profession.”

(339 U. S. 641) The Supreme Court, therefore, concluded:

“ the conditions under which this appellant is required to

receive his education deprived him of his personal and