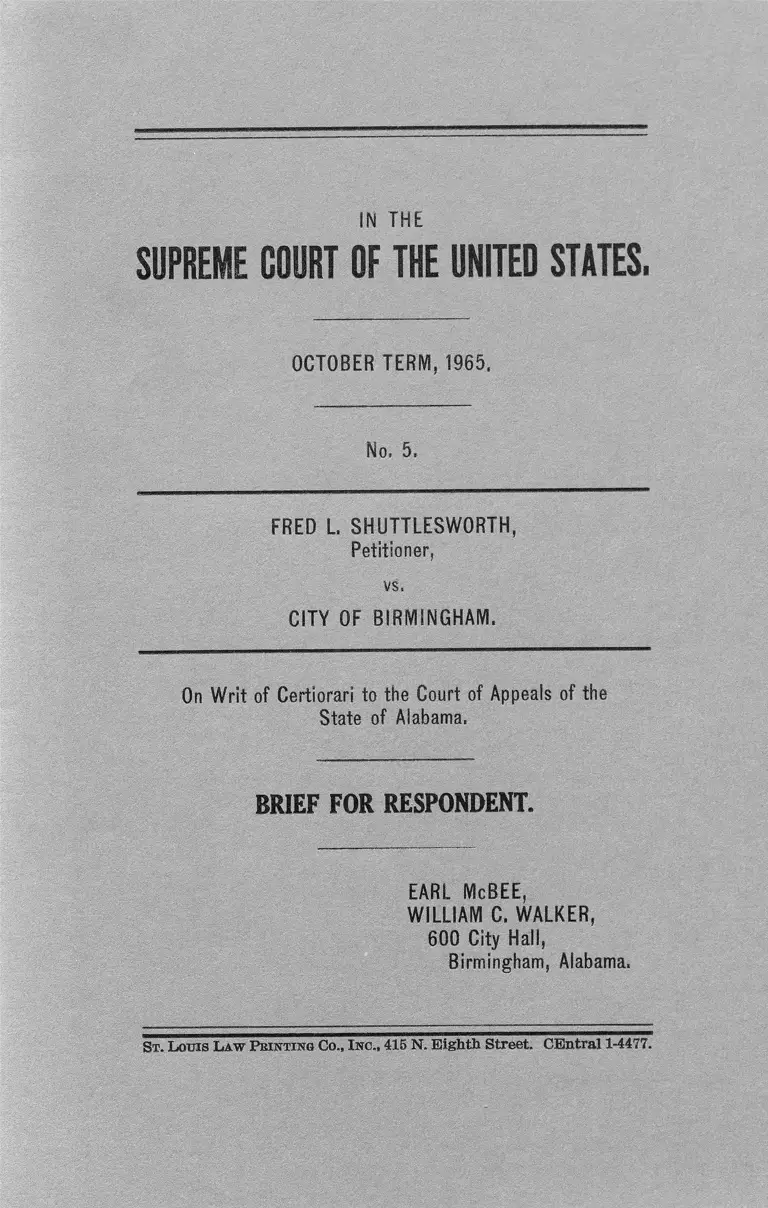

Shuttlesworth v Birmingham AL Brief for Respondent

Public Court Documents

October 1, 1965

44 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Shuttlesworth v Birmingham AL Brief for Respondent, 1965. 1d766f4e-c49a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/732b1b1f-cea9-4e09-90ff-1071e4354275/shuttlesworth-v-birmingham-al-brief-for-respondent. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES.

OCTOBER TERM, 1965.

No. 5.

FRED L. SHUTTLESWORTH,

Petitioner,

vs.

CITY OF BIRMINGHAM.

On Writ of Certiorari to the Court of Appeals of the

State of Alabama.

BRIEF FOR RESPONDENT.

EARL McBEE,

WILLIAM C. WALKER,

600 City Hall,

Birmingham, Alabama.

St. Loots Law Printing Co., Inc.. 415 N. Eighth Street. CEntral 1-4477.

INDEX.

Page

Questions presented ............................ 1

Statement of case ........................................ 2

Summary of argument .................................................... 8

Argument ............................................................................... 10

Conclusion .......................................................... 88

Cases Cited.

Allison-Russell Withington Co. v. Sommers, 121 So.

42, 219 Ala. 33 ................................................................ 11

Andalusia Motor Company v. Mullins, 183 So. 456, 28

Ala. App. 201, cert, denied 183 So. 460, 236 Ala.

474 ................................................................................. 37,38

Barbour v. State of Georgia, 248 U. S. 454, 39 S. Ct.

316 ................................................................................... 15

Barton v. U. S., 25 Fed. 2d 967, cert, denied 49 S. Ct.

24, 278 U. S. 621, 73 L . ed. 542 ................................. 37

Benson v. City of Norfolk, 163 Va. 1037, 177 S. E. 222 14

Blair v. Greene, 246 Ala. 28, 18 S. 2d 688 ............... 25

Bouie v. City of Columbia, 84 8 . Ct. 1697, 378 U. S. 347 25

Cahaba Coal Co. v. Elliott, 62 So. 808, 810, 183 Ala.

298 ................................................................................... 14

Challis v. Pennsylvania, 8 Pa. Sup. 130, 132............ 14

City of Chariton v. Fitzsimmons, 54 N. W. 146, 87

Iowa 226 ..................................................................... 14

City of Tacoma v. Roe, 190 Wash. 444, 68 P. 2d 1028 14

.City v. Sliuttlesworth, 42 Ala. App. 296, 161 So. 2d

796 ............................................................................................. .. • • • • 24

Claassen v. United States, 142 U. S. 140, 146, 12 S. Ct.

169, 35 L. ed. 966 ......................................................... 87

11

Clift v. U. S., 22 Fed. 2d 549 .........................................

Cox v. Louisiana, 379 U. S. 536, 85 S. Ct.

453 ................................................................. 18,19,20,29,

Davis v. Wechsler, 263 U. S. 22, 24, 44 S. Ct. 13, 14, 68

L. Ed. 143 ....................................................................

Douglas v. State of Alabama, 380 U. S. 415, 422, 85

S. Ct. 1074 ....................................................................

Drummond v. State, 67 So. 2d 280, 37 Ala. App. 308

Ex Parte Bell, 19 Cal. 2d 488, 122 P. 2d 2 2 ................

Ex Parte Bodkin, 86 Cal. App. 2d 208, 194 P. 2d 588

Ex Parte Bodkin, 194 Pan. 2d 588, 591, 86 Cal. App.

2d 208 .............................................................................

Fort v. Civil Service Comm, of Alameda County, 38

Cal. Rptr. 625, 392 P. 2d 385 .....................................

Garner v. State of Louisiana, 82 S. Ct. 298, 368 U. S.

157 ...................................................................................

Henry v. State of Mississippi, 379 U. S. 443, 85 S. Ct.

564 ...................................................................................

Herndon v. State of Georgia, 295 U. S. 441, 55 S. Ct.

794, 79 L. Ed. 1530, rehearing denied 56 S. Ct. 82,

296 U. S. 661, 80 L. Ed. 471.....................................

Hiawassee River Power Co. v. Carolina Tennessee

Power Co., 252 U. S. 341, 40 S. Ct. 330.................

Howison v. Oakley, 23 So. 810, 118 Ala. 215..............

Jones v. Belue, 200 So. 886, 241 Ala. 22 ...................

Long v. Leith, 16 Ala. App. 295, 77 So. 445 ...............

Martin v. State, 81 So. 851, 17 Ala. App. 73.................

Middlebrooks v. City of Birmingham, . .. Ala. App.

. . . , 170 So. 2d 424 .................................................. 12,

Milk Wagon Drivers Union v. Meadowmoor Dairies,

312 U. S. 287, 61 S. Ct. 552, 85 L. ed. 836.............

Morgan v. Embry, 85 So. 580, 17 Ala. App. 276 .......

Peabody v. State, 246 Ala. 32, 18 So. 2d 693.............

37

30

15

15

35

28

14

29

28

12

15

15

15

14

38

38

35

14

35

38

26

I l l

Phifer v. City of Birmingham, 42 Ala. App. 282, 160

So. 2d 898, 901 ............................... 3,13,14,17,24,31,

Pierce v. tJ. S., 40 S. Ct. 205, 252 IT. S. 239, 64 L. ed.

542, affirmed 245 F. 878 ................................................

Portland R. L. & P. Co. v. Railroad Commission, 229

U. S. 397, 33 S. Ct. 829, 57 L. ed. 1248.....................

Shuttlesworth v. City of Birmingham, 42 Ala. App.

296, 161 So. 2d 796, 797 ..............................................

Smith v. McLaughn, 184 P. 2d 177, 81 Cal. App. 2d 815

State v. Sugarman, 126 Minn. 477, 148 N. W. 446. .

Tarver v. State, 85 So. 855, 17 Ala. App. 424..........

Thompson v. City of Louisville, 362 U. S. 199, 80

S. Ct. 624, 4 L. ed. 2d 654 ...........................................

Thornhill v. State of Alabama, 310 U. S. 106, 60 S.

Ct. 737 ............................................................................

Tinsley v. City of Richmond, 202 Virginia 707, 119

S. E. 2d 488, app. dismissed, 368 U. S. 1 8 .. . . 14, 21,

Turnipseed v. Burton, 4 Ala. App. 612, 58 So. 959 . ..

U. S. v. Parillo, 299 F. 714 ............................... .............

United States v. Harris, 347 U. S. 612, 617, 74 S. Ct.

808, 812, 98 L. Ed. 989 .............................................. 25,

United States v. Raines, 362 U. S. 17, 80 S. Ct. 519,

522 ...................................................................................

Wages v. State, 25 Ala. App. 84, 141 So. 709, Cert.

denied 225 Ala. 10, 141 S. 713 ...................................

Webb v. Litz, 39 Ala. App. 443, 102 So. 2d 915..........

Western Railway of Alabama v. Arnett, 34 So. 997,

1000 last paragraph, 137 Ala. 414.............................

White Roofing Co. v. Wheeler, 106 So. 2d 658, 39

Ala. App. 662, cert, denied 106 So. 2d 665, 268 Ala.

695 ....................................................................................

White v. City of Birmingham, 41 Ala. App. 181, 130

So. 2d 231 .....................................................................

White v. Jackson, 62 So. 2d 477, 36 Ala. App. 643 . ..

Whitney v. California, 274 U. S. 397, 47 S. Ct. 641, 71

L. ed. 594 .......................................................................

33

37

35

34

37

14

35

35

28

22

38

37

28

30

26

14

14

38

13

38

35

IV

Williams v. State of Georgia, 349 U. S. 375, 99 L. Ed.

1161 ................................................................................. 15

Wright v. State of Georgia, 373 U. S. 284, 83 S. Ct.

1240 ................................................................................. 15

Yeats v. Mooty, 175 So. 719, 128 F. Ca. 658 ................. 37

Statutes Cited.

Birmingham General City Code of 1944:

Section 1142 .....................................2,3,8,9,11,16,26,27

Section 1231 ............................... .........................3,9,16,27

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES.

OCTOBER TERM, 1965,

No. 5,

FRED L. SHUTTLESWORTH,

Petitioner,

vs.

CITY OF BIRMINGHAM.

On W ri t of Certiorari to the Court of Appeals of the

State of Alabama,

BRIEF FOR RESPONDENT.

QUESTIONS PRESENTED.

Respondent feels the statements of “ questions pre

sented” by petitioner are in some material degree in

accurate or misleading and should be rephrased.

1. Whether as applied to one who is a member or part

of a group of ten or twelve persons standing or loitering

on a sidewalk on a corner in the heart of the business

district of a city so as to block or interfere with free

passage of other pedestrians and force them out into the

___9

street occupied by vehicular traffic, absent any question

or issue of free assembly or free speech, an ordinance

aimed at promoting free flow of traffic and making it an

offense to continue to so stand or loiter after having been

requested by a policeman to move is vague and over

broad in violation of the Fourteenth Amendment.

2. Whether as applied to one described in question one,

the two sentences of a paragraph of an ordinance entitled

“ Streets and sidewalks to be kept open for free passage,”

and construed by a state court to state a single offense,

may nevertheless be separated into two elements and as

thus severed successfully attacked for vagueness or over-

broadness as though two separate offenses were involved,

one for obstructing free passage and the other for refusing

to heed the request of an officer to move.

3. Whether one described in questions one and two

above, who is tried on a complaint containing two counts,

the first of which charges violation of the ordinance

referred to in questions one and two, and the second

count charging violation of an ordinance construed by the

state court as making it an offense to refuse or fail to

comply with an order concerning vehicular traffic, can

sustain a contention that due process is lacking for total

absence of evidence to support count two in violation

of due process, and if so a reversal of the general convic

tion on the complaint as charged where the penalty for

only one offense is assessed is warranted.

STATEMENT OF CASE.

Petitioner was charged and convicted in Alabama Cir

cuit Court on a complaint containing two counts. The

first count charged the blocking or obstructing of free

passage on the sidewalk and failure to cease such block

ing or obstructing free passage after request by a police

officer to do so as proscribed by Section 1142 of the Gen

eral City Code of 1944. The second count charged failure

to obey a reasonable and lawful order of a police officer

in. violation of Section 1231 of such Code. This section

was construed by the Court of Appeals of Alabama to be

limited to lawful orders having relation to vehicular traffic

upon the street. Phifer v. City of Birmingham, 42 Ala.

App. 282, 160 So. 2d 898, 901.

That court construed 1142 as not involving in its ap

plication in this case any question of free speech, and

upheld its constitutionality as thus applied in this case.

The tendencies of the evidence of the City was sum

marized and held sufficient to sustain a conviction but

in which only one sentence was imposed under Counts

one and two.

The findings of the Court of Appeals both that the peti

tioner was in violation of 1142 by blocking or obstructing

free passage upon the sidewalk and failing to clear the

blockage or obstruction after being requested by a police

officer to do so and that no first amendment freedoms were

involved in the incident in the nature of free speech or

free assembly is amply supported by the record. Also we

feel the evidence was sufficient to support a conviction

under Count two relating to 1231.

We here make reference to the evidence in the record

which we feel fully supports the conclusion of the Court

of Appeals of Alabama.

The following facts were established by the evidence

introduced in the trial court. On April 4, 1962, at about

10:30 A. M., Officer Robert E. Byars, Jr., observed the

petitioner, along with James Phifer and three or four

other people walking south on 19th Street toward 2nd

Avenue, North, Birmingham, Alabama (R. 16, 19). Officer

Byars then entered Newberry’s Department Store at its

alley entrance and walked to the front of the store at

19th Street and 2nd Avenue, North (R. 16, 17). When he

got to the front entrance he saw the petitioner standing

in a group of ten or twelve people (R. 17, 27, 38). They

4

were on the northwest corner of 2nd Avenue and 19th

Street (R. 17, 27, 40, 59). The group was standing (R.

17, 38). The traffic light changed a number of times while

they stood there at the intersection (R. 36). The group

blocked pedestrian traffic to such an extent that some

people walking east on the north side of 2nd Avenue had

to walk into the street, thereby interfering with vehicular

traffic1 (R. 17, 20, 28, 39). Petitioner was a member of

this group (R. 17, 18). Officer Byars watched the group

for a minute to a minute and a half before accosting them

(R. 18, 26, 28). Officer Byars then walked up to the group

and informed them they would have to move on and clear

the sidewalk so as to allow free passage of pedestrian

traffic and not obstruct the sidewalk (R. 18, 27, 28). While

Officer Byars was talking to the group he was observed

by Officer James Paul Renshaw, a police patrolman on

motorcycle (traffic) duty (R. 40, 43, 47). Officer C. W.

Hallman, a traffic policeman (R. 59), Officer John D.

Allred, police patrolman also on traffic duty (R. 66, 70),

and Cecil W. Davis, a traffic officer (R. 73, 74).

When Officer Byars first spoke to the group requesting

them to move (R. 28, 31, 41, 47, 49), only a small part

moved. Petitioner did not move (R. 18, 41, 49, 60). After

a short while, the officer informed the group a second

time they would have to move and not obstruct the side

walk in order to permit pedestrian traffic to move un

hampered (R. 18, 28). Petitioner and some others in the

group did not move and petitioner stated: “ You mean

to say we can’t stand here on the sidewalk!” (R. 18, 28.)

Officer Byars did not do or say anything for a short period

and then he told the group that he was telling them the

third and last time to move or they would be arrested

for obstructing the sidewalk (R. 18, 41, 60). Petitioner

1 The onlv logical conclusion to he drawn from the testimony

of the witnesses that pedestrians were forced into the street is that

such pedestrians interfered with vehicular traffic in the street.

was still in the group (R. 18, 28, 41, 49, 59, 60, 74). Every

body began to move but him (R. 28). Petitioner did not

move but made the statement “ You mean to tell me we

can’t stand here in front of this store!” (R. 18.) Officer

Byars then informed petitioner that he was under arrest,

after which time petitioner moved away saying: “ Well,

1 will go into the store” (R. 18, 20, 41, 52). Officer Byars

followed petitioner into Newberry’s store and took him

into custody (R. 18, 19).

Officer Byars had heard that a boycott or selective buy

ing campaign was in progress at the time he arrested peti

tioner, but he had not been informed by his superiors

that such boycott or selective buying campaign was going

on and received no assignment relating to it (R. 24, 25).

Officer Byars did not know either petitioner or James S.

Phifer, co-defendant in Circuit Court, at the time he ar

rested them (R. 16, 22, 23). In fact, this is corroborated

by Robert J. Norris, a defense witness when he testified

that Officer Byars never called petitioner by name (R. 99).

In fact, even petitioner adimts that Officer Byars did not

call him by name.

Officer James P. Rcnshaw, who was going south on 19th.

Street between 3rd Avenue and 2nd Avenue (R. 40),

testified he saw the group talking to Officer Byars. Officer

Renshaw was on a motorcycle and he got off and went to

Officer Byars (R. 41). Officer Renshaw reached Officer

Byars in time to hear him tell the group the third time

to move (R. 41, 49). Officer Renshaw was present when

petitioner was arrested (R. 52), but he did not assist in

the arrest (R. 48). No one assisted Officer Byars in mak

ing the arrest.1 Officer Renshaw testified that there were

1 While Officer Renshaw testified that he assisted Officer Byars

in the arrest, elaboration of his testimony revealed his assistance

consisted of nothing more than being present (R. 48). Tn fact,

the petitioner admitted that Officer Byars was the arresting officer

(R. 112, 113) and this was corroborated by James S. Phifer (R.

128).

— 6 —

about eight or ten or twelve people in the crowd when

told the third time to move (R. 49) and that some may

have moved off at the time. Officer Byars told petitioner

he was under arrest (R. 52). Officer Renshaw had heard

that the Negroes of the City of Birmingham were engaged

in a selective buying campaign but he knew of no orders

issued by his superiors concerning such campaign (R. 43,

44). At the time Officer Byars arrested petitioner, Officer

Renshaw knew petitioner but didn’t know James Phifer

(R. 40). Although he didn’t know James S. Phifer by

sight he knew he was a notorious person in the field of

civil rights in the City of Birmingham (R. 46).

Officer Hallman testified that he was a traffic policeman

working traffic at the intersection of 2nd Avenue, North,

and 19th Street (R. 59). He first saw the group talking

to Officer Byars (R. 59). When he first saw the group he

was talking to Officer Davis about a message to call his

(Officer Hallman’s) home (R. 59, 61). Officer Hallman

and Davis arrived in time to hear him say to the group,

‘ ‘ I am telling you for the third time you will have to move

on, you are blocking the sidewalk” (R. 59). There was

still five or six in the group and they all moved away ex

cept petitioner (R. 60) and Officer Byars then arrested

petitioner (R. 60). At the time of petitioner’s arrest

Officer Hallman had heard about a selective buying cam

paign but had heard nothing from his superiors concern

ing such campaign (R. 63).

Officer John D. Allred, patrol division on traffic duty,

testified he had left roll call (R. 69) and was on his way

to 3rd Avenue and 20th Street (R. 66, 68, 69) where he

was to work traffic (R. 66, 68). He was about twenty-five

or thirty feet south of the alley by Newberry’s and was

giving directions to some people when he first heard

Officer Byars tell the group they would have to move on

(R. 66, 69). Officer Allred did not go to Officer Byars

until after the arrest of petitioner but continued to give

directions to the people he was talking to (R. 67, 70).

Officer Allred estimated the size of the group at maybe

ten or fifteen or twenty people (R. 71).

At the time of petitioner’s arrest Officer Allred did

not know petitioner (R. 68).

Officer Cecil W. Davis testified he was patroling park

ing meters on a motorcycle (R. 76) but at the time he

first observed the group talking to Officer Byars he was

delivering a message to Officer Hallman (R. 77). Officer

Davis was with Officer Hallman when he first observed

the group with Officer Byars (R. 73). He testified there

was about ten or twelve in group (R. 74). Officer Davis

crossed the street to where Officer Byars was in time

to hear him tell petitioner he was under arrest (R. 74),

and there was still a crowd around petitioner at that

time (R. 74). He heard Officer Byars tell petitioner he

was under arrest (R. 74). At the time of petitioner’s

arrest Officer Davis had heard about the selective buying

campaign but no one at police headquarters had dis

cussed it with him (R. 78). Officer Davis knew both

petitioner and James S. Phifer.

The evidence is without dispute that Byars did not

know Shuttlesworth prior to the arrest (R. 29) nor did

Shuttlesworth know Byars (R. 113). Byars did not ad

dress Shuttlesworth by name (R. 112).

Byars did not know Phifer prior to the arrest (R. 16,

22-23). Byars also rvas not known to Phifer (R. 128).

Officer Byars was on traffic duty and had no assignment

relating to the boycott he had heard was supposed to

be in progress (R. 24).

No claim is made by petitioner or his witnesses of any

activity involving freedom of speech or assembly. As

Shuttlesworth expressed his version of the incident they

were walking as pedestrians walk and simultaneously as

they approached the light at the corner the officer came

out of the door and said “ move on” (R. I l l , 112).

8

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT,

I.

Count one of respondent’s complaint charged petitioner

with violation of Section 1142 of the General Code of

Birmingham. Count two of respondent’s complaint

charged petitioner with violation of Section 1231 of the

General Code of Birmingham. Each section and each

count based thereon embrace a single offense. Petitioner

argues that if either count is based on a constitutionally

vulnerable section his conviction should be reversed.

Both sections are however, constitutionally valid. In

addition to this, however, petitioner has not followed

the proper state court procedures to raise the question

insofar as Section 1231 is concerned and this Honorable

Court should not even consider the validity of this sec

tion.

II.

Section 1142 of the General Code of Birmingham in

sofar as it makes it unlawful to stand or loiter on any

sidewalk of the city after having been requested by a

police officer to move on is neither vague, overbroad,

nor constitutionally objectionable. As written the ordi

nance does not give policemen absolute or arbitrary

power to order any citizen off the streets. As written

it is a valid police regulation. Neither the provisions

of Section 1142 nor its construction and application in

this case involve free speech or any other freedoms pro

tected by the First-Fourteenth Amendments. Section 1142

gives fair notice of its proscriptions. The Alabama Court

did not construe this section as shifting the burden of

proof to the defendant to disprove that he was loitering

so as to obstruct free passage.

III.

Section 1142 of the General Code of Birmingham, in

sofar as it makes it unlawful to so stand, loiter, or walk

on any sidewalk in the city as to obstruct free passage

thereon is not vague and overbroad. This provision does

not involve any first amendment freedom and it has not

been construed to apply to any such situation.

IV.

The conviction of petitioner for violation of Section

1231 of the General Code of Birmingham, making it un

lawful to refuse to comply with a lawful police order

is based on ample evidentiary support, but even if it

were held otherwise, reversal of the conviction of peti

tioner would not be warranted because his conviction is

sustained under Count one.

10

ARGUMENT.

I.

Point I of Petitioner’s Argument Is Without Merit.

Petitioner in this section of his argument argues that

the complaint charged two separate offenses in Count One

and a third offense in Count Two with the conclusion that

reversal should follow if either is constitutionally vul

nerable.

In reply to the contention of petitioner in Section 1 of

his Argument, pages 13 and 14 of his brief, citing Strom-

berg v. Carlson; Williams v. North Carolina, and Thomas

v. Collins, we take the position that the principle of these

cases cannot be given application in the manner employed

to make two charges out of Count One, which is based

upon Ordinance 1142, nor to present for review the Con

stitutionality vel non of Ordinance 1231.

First, the holding of these cases is simply that where

a conviction is upheld in a state appellate court on plead

ings charging more than one violation, the verdict or

judgment being general, and it being impossible to know

whether the conviction was upon the one charged or the

other, the conviction will be reversed if any of the charges

are unconstitutional, because the conviction may have

been based thereupon.

The record in this case clearly shows in respect to

count one that only one charge was lodged against peti

tioner under this count. Neither the trial court nor the

Alabama Court of Appeals, nor the City, nor anyone,

prior to certiorari to this Honorable Court, ever men

tioned, or so far as we know, ever imagined or speculated

that the petitioner was charged with loitering or stand

ing upon the sidewalk so as to obstruct free passage

thereupon and also with merely standing or loitering on

the sidewalk after being requested to move on.

No mention of such contention was ever made in any

demurrer or other pleading filed by petitioner nor at any

other time so far as the record shows.

The complaint filed by the attorney and upon which

Shuttlesworth was tried connects and ties the two sen

tences of the last paragraph of 1142 together in one

charge.

Count one1 charges defendant loitered upon the side

walk, a member of or within a group which obstructed

free passage or did loiter or stand while in said group (we

interpolate, the group loitering or standing to block free

passage on the sidewalk) after having been requested by

a police officer to move on.

There can be no doubt whatsoever that the Alabama

Court of Appeals construed the ordinance and the com

plaint to charge both a blocking or obstruction of free

passage and also a failure to move after having been re

quested to do so by a police officer. The evidence sum

marized by the court spelled out both elements of ob

structing and request to move.2

— 11 —

1 Count One. “ Comes the City of Birmingham, Alabama, a mu

nicipal corporation, and complains that F. L. Shuttlesworth, within

twelve months before the beginning of this prosecution and within

the City of Birmingham, or the police jurisdiction thereof, did

stand, loiter or walk upon a street or sidewalk within and among

a group of other persons so as to obstruct free passage over, on or

along said street or sidewalk at, to-wit: 2nd Avenue North, at 19th

Street or did while in said group stand or loiter upon said street

or sidewalk after having been requested by a police officer to move

on, contrary to and in violation of Section 1142 of the General City

Code of Birmingham of 1944, as amended by Ordinance Number

1436-F" (R. 2-3).

- We have quoted this summary on page 34 of this brief.

— 12

In the case of Middlebrooks v. City of Birmingham,

. . . Ala. App. . . 170 So. 2d 424, the Alabama Court

of Appeals followed the construction in the Phifer and

Shuttlesworth cases, of the second paragraph of Section

1142, in the following language:

“ This is the fourth case in the last year wherein

this court has considered the second paragraph of

Section 1142 as amended. That provision is directed

at obstructing the free passage over, on or along a

street or sidewalk by the manner in which a person

accused stands, loiters or walks thereupon. Our de

cisions make it clear that the mere refusal to move

on after a police officer’s requesting that a person

standing or loitering should do so is not enough to

support the offense.”

“ That there must also be a showing of the accused’s

blocking free passage is the ratio decidendi of Phifer

v. City of Birmingham, 42 Ala. App. 282, 160 So. 2d

898, and Shuttlesworth v. City of Birmingham, 42

Ala. App. 296, 161 So. 2d 796. In this respect, we

distinguish our reasoning from that employed by the

Virginia Supreme Court of Appeals in Tinsley v. City

of Richmond, 202 Va. 707, 119 S. E. 2d 488.”

Under this construction it is clear that only one offense

is contained in the second paragraph of Section 1142 as

amended. As construed, this Section is a reasonable exer

cise of the state’s police power and is constitutionally

valid. This construction placed on this ordinance in the

Phifer, Shuttlesworth and Middlebrooks cases is also

binding upon this Honorable Court. The rule in this re

gard has been stated in Garner v. State of Louisiana, 82

S. Ct. 298, 368 U. S. 157, as follows:

“ Whether the state statutes are to be construed one

way or another is a question of state law, final decision

of which rests of course with the Courts of the State.’ ’

As to Ordinance 1231, and as to which we feel only a

very general and possibly no serious effort was made in

petitioner’s brief to attack its constitutionality we respect

fully urge the record does not present its constitutionality

for review. The method sought to be employed to raise

the constitutional question in the trial court was by motion

to quash and demurrer. The Court of Appeals of Alabama

did not reach for consideration its constitutionality be

cause of the failure of petitioner to comply with state court-

procedural requirements. Petitioner on page 11 of his

brief concedes this.1

In the Shuttlesworth case, the Alabama Court of Appeals

adopted its ruling in the companion, Phifer, case, with

respect to the assignments relating to the motion to quash

and the ruling on demurrer, and did not further deal with

these assignments of error.

The Court of Appeals of Alabama held in the Phifer

case, 160 So. 2d 898, 42 Ala. App. 282, ruling on motion to

quash was not reviewable on appeal. White v. City of

Birmingham, 41 Ala. App. 181, 130 So. 2d 231.

1 ‘ ‘In Phifer, the Alabama Court of Appeals sustained the over

ruling of a motion to quash and demurrers by petitioner Shut-

tlesworth’s co-defendant below, these documents being identical to

those filed on behalf of Shuttlesworth. Phifer’s constitutional at

tack on Section 1142, the loitering ordinance, was rejected on the

merits; Phifer’s challenge to Section 1231 was not reached, because

While the demurrer in its caption is directed to the complaint “ and

to each and every count thereof, separately and severally,” it is

really interposed to the two counts of the complaint jointly.’ 42

Ala. App. at . . . ., 160 So. 2d at 900. Whatever the force under

state law of this esoteric ruling that a paper expressly captioned

‘several’ is to be deemed ‘ joint’ , it is clear that the ground is in

sufficient to bar this court’s review on the merits of the attack

on Section 1231. Any ‘objection which is ample and timely to

bring the alleged federal error to the attention of the trial court

and enable it to take appropriate corrective action is sufficient to

serve legitimate state interests, and therefore, sufficient to preserve

the claim for review here.’ Douglas v. Alabama, 380 U. S. 415, 422,

see Henry v. Mississippi, 379 U. S. 443 (1965 ). In any event, the

matter is” immaterial because petitioner's attack on Section 1142 is

dispositive of the case. See pp. 17-18 infra.’

— 14 —

The assignment of error relating to the ruling on de

murrer was overruled for the reason both that the several

grounds of demurrer assigned were so broad in scope as

to embrace the whole complaint,2 and the assignment of

error was so broad as to embrace the whole complaint.

Consequently the demurrer and the assignment of error

based on the ruling on it could be sustained only if the

complaint was bad in its entirety and as to each count.

These principles of procedural law have been well es

tablished and uniformly applied by the Appellate Courts

of Alabama over a half century. Cahaba Coal Co. v. El

liott, 62 So. 808, 810, 183 Ala. 298; Allison-Russell With-

ington Co. v. Sommers, 121 So. 42, 219 Ala. 33; Western

Railway of Alabama v. Arnett, 34 So. 997, 1000 last para

graph, 137 Ala. 414; Howison v. Oakley, 23 So. 810, 118

Ala. 215; Webb v. Litz, 39 Ala. App. 443, 102 So. 2d 915.

The Alabama Appellate Court did discuss the constitu

tional attack upon the last paragraph of 1142 and found

that it was not aimed at free speech, but was a legitimate

exercise of police power by the municipality to enact and

enforce reasonable regulations for the control of traffic and

the use of its streets and sidewalks.

In support of this conclusion the Alabama Court cites;

decisions from other states including Washington, Vir

ginia and California.3 In Section II of this brief we shall

2 The Court of Appeals set out the grounds of demurrer chal

lenging the ordinances in the Phifer case. It is clear that each of

the grounds attacked both ordinances 1142 and 1231 in the conjunc

tive and therefore were directed to both counts. Phifer v. City of

Birmingham, 160 So. 2d 898, 899.

a City of Tacoma v. Roe, 190 Wash. 444, 68 P. 2d 1028; Benson

v. City of Norfolk, 163 Va. 1037, 177 S. E. 222; Ex Parte Bodkin,

86 Cal. App. 2d 208, 194 P. 2d 588. Other cases which might also

have been appropriately cited include: Minnesota, State v. Sugar-

man. 126 Minn. 477, 148 N. W. 446; Pennsylvania, Challis v.

Pennsylvania, 8 Pa. Sup. 130, 132; Iowa, City of Chariton v. Fitz

simmons, 54 N. W. 146, 87 Iowa 226; and also the later Virginia

case, Tinsley v. City of Richmond, 202 Virginia 707, 119 S. E. 2d

488, app. dismissed, 368 U. S. 18.

attempt to elaborate upon the correctness of the ruling of

the Court of Appeals sustaining the constitutionality of

1142.

To return to Count two involving 1231, the United States

Supreme Court has recognized the right of the State Court

to apply reasonable procedural rules of the state even to

the point that it may properly decline to rule on a con

stitutional question and when it does in good faith apply

consistently and uniformly a well established procedural

rule the constitutional question is not before the United

States Supreme Court. Barbour v. State of Georgia, 248

IT. S. 454, 39 S. Ct. 316; Herndon v. State of Georgia, 295

IT. S. 441, 55 S. Ct. 794, 79 L. Ed. 1530, rehearing denied

56 S. Ct. 82, 296 U. S. 661, 80 L. Ed. 471; Hiawassee River

Power Co. v. Carolina Tennessee Power Co., 252 U. S.

341, 40 S. Ct. 330; Williams v. State of Georgia, 349 U. S.

375, 99 L. Ed. 1161.

More recent decisions of this court in Douglas v. State

of Alabama, 380 U. S. 415, 422, 85 S. Ct. 1074, and Henry

v. State of Mississippi, 379 U. S. 443, 85 S. Ct. 564, are

cited in the last sentence of footnote 9 on page 11 in peti

tioner’s brief quoted by us in footnote 3 on page 13, ante.

These cases and older cases such as Wright v. State of

Georgia, 373 U. S. 284, 83 S. Ct. 1240, and Davis v. Wech-

sler, 263 U. S. 22, 24, 44 S. Ct. 13, 14, 68 L. Ed. 143, recog

nize the right of this Honorable Court to examine the pro

cedural rule in question and determine if any reasonable

State interest is conserved by the application of the pro

cedural rule and whether it may in fairness be invoked.

We think the ancient rules applied in this case were

fairly and properly applied. If is of interest that after

citing the first two of the above cases, petitioner indicates

he is not pressing for the application of these eases here,

but chooses to rely instead on his claim of unconstitution

— 16—-

ality of 1142.4 This minimizing of reliance upon these

cases seems to be implicit in the strategy employed in Sec

tion IV of petitioner’s brief in which he addresses his argi-

ment primarily to a claimed lack of evidence to support

a conviction on this count and the statement5 made on

page 29 of his brief that but for the restrictive construc

tion placed on 1231 by the Court of Appeals of Alabama, it

would be subject to the vices he claims inheres in 1142.

Point II (A & B) of Petitioner’s Argument

Are Each Without Merit.

II-A.

THE LAST SENTENCE OF 1142 IS NOT VAGUE

OR OVERBROAD.

Petitioner in this section of his argument seeks reversal

of the conviction of petitioner by attempting to split the

last paragraph of Ordinance 1142 in half and to separate

the last sentence from the first sentence and in so doing

contends that such sentence is over broad and in violation

o f the First and Fourteenth Amendments.

We have already in Section I of this brief presented

our contention that this artificial attempt to split this

paragraph into separate charges is not permissible in this

ease. The charge made against petitioner in Count one

and proven by the City’s evidence was that he, together

with or in a group of ten or twelve blocked or obstructed

4 “ In any event, the matter is immaterial because petitioner’s at

tack on Section 1142 is dispositive of the case. See pp. 13-14

infra.” Pet. brief, p. 11.

3 “ If construed as broadly as it is written, Birmingham Code

1231, making it ‘unlawful for any person to refuse or fail to com

ply with any lawful order, signal or direction of a police officer,’

would be objectionable for the reasons stated in pp. 14-15, supra.

The Alabama Court of Appeals, however, has put a quite narrow

construction on the section.” Pet. brief, p. 29.

— 17 —

free passage on the sidewalk and failed to move and

clear the sidewalk for free passage after having been re

quested to do so by the officer on three separate occasions.

The ordinance in question, either considering the last

paragraph as containing one or two proscriptions, was

not in this case construed to prohibit or interfere with

freedom of speech or any other amendment one freedoms

or rights. The Court of Appeals of Alabama expressly

stated they were not applying it to any situation involv

ing such constitutionally guaranteed freedom. City of

Birmingham v. Phifer, 42 Ala. App. 282, 160 So. 2d

898, 900:

“ Section 1142, as amended, of the General City

Code of Birmingham, is not aimed at free speech. It

directs the manner in which sidewalks and streets

may not be used. A municipality has the right under

its police power to enact and enforce reasonable regu

lations for the control of traffic and the use of its

streets and sidewalks.”

On its face and under the construction placed upon 1142

it proscribes conduct, not a facet of freedom of speech and

assembly, which results in obstructing the free and un

impeded use of the sidewalks and streets for pedestrians

and vehicular traffic respectively.

No contention was made at any time that Shuttlesworth

and his associates were involved in any facet of free

speech or free assembly on the occasion of his arrest. The

record clearly negates any such claim. Petitioner and each

of his witnesses claimed that they were merely walking

along the sidewalk as any other citizen to get from one

point in the City to another. There was no demonstration.

There was no picketing. There was no parading. There

was not even any hint of any activity involving freedom

of speech or assembly or- any other first, amendment

freedom.

18 —

All that is here involved is the simple right of the mu

nicipality under its police power to control and regulate

the use of its sidewalks and streets as passageways to

permit pedestrians and vehicular traffic a safe, proper

and unimpeded use thereof.

The constitutionality of 1142 must be tested in this case

by the principle given application by this Honorable Court

in Cox v. New Hampshire, and Cox v. Louisiana, 379

U. S. 536, 85 S. Ct. 453.

These cases illustrate the principle long adhered to by

this Honorable Court that unless by its express language

or by construction placed upon it by the state courts, an

ordinance or statute impinges upon the first amendment

freedoms, such ordinance or statute is not unconstitu

tional when its application is limited to simply conserving

public convenience and safety in the use of sidewalks and

streets for the purpose they were designed.1

In Cox v. Louisiana, a statute2 on its face aimed at free

and unobstructed passage upon public sidewalks and

streets was construed by the Supreme Court of Louisiana

1 Mr. Justice Goldberg in the majority opinion in Cox v. Louisi

ana recognizes that even freedom of speech and assembly may have

to give way to overpowering public convenience and safety in use

of the streets (Headnotes 11-13).

- “ Obstructing Public Passages. No person shall wilfully ob

struct the free, convenient and normal use of any public sidewalk,

street, highway, bridge, alley, road, or other passageway, or the en

trance, corridor or passage of any public building, structure, water

craft or ferry, by impeding, hindering, stifling, retarding or restrain

ing traffic or passage thereon or therein.

“ Providing however nothing herein contained shall apply to a

bona fide legitimate labor organization or to any of its legal activi

ties such as picketing, lawful assembly or concerted activity in the

interest of its members for the purpose of accomplishing or secur

ing more favorable wage standards, hours of employment and

working conditions.”

to be applicable in a first amendment situation involving

a civil rights demonstration.8 Because of this construc

tion by the Louisiana Court, this Honorable Court held

the statute as thus applied to Cox to be unconstitutional

and reversed his conviction.

“ (19) It is, of course, undisputed that appropriate,

limited discretion, under properly drawn statutes or

ordinances, concerning the time, place, duration, or

manner of use of the streets for public assemblies may

be vested in administrative officials, provided that

such limited discretion is ‘ exercised with “ uniformity

of method of treatment upon the facts of each appli

cation, free from improper or inappropriate consid

erations and from unfair discrimination” * * * (and

with) a “ systematic, consistent and just order of

treatment, with reference to the convenience of public

use of the highways * * ’ Cox v. State of New

3 In Cox there appeared to be no statute providing for peaceful

parades or demonstrations. The 1944 General City Code of Bir

mingham made provision for peaceful parades or demonstrations

in Section 1159:

“ Sec. 1159. Parading. It shall be unlawful to organize or hold,

or to assist in organizing or holding, or to take part or participate

in, any parade or procession or other public demonstration on the

streets or other public ways of the city, unless a permit therefor

has been secured from the commission.

T o secure such permit, written application shall be made to the

commission, setting forth the probable number of persons, vehicles

and animals which will be engaged in such parade, procession or

other public demonstration, the purpose for which it is to be

held or had, and the streets or other public ways over, along or in

which it is desired to have or hold such parade, procession or other

public demonstration. The commission shall grant a written permit

for such parade, procession or other public demonstration, prescrib

ing the streets or other public ways which may be used therefor,

unless in its judgment the public welfare, peace, safety, health, de

cency, good order, morals or convenience require that it be refused.

It shalf be unlawful to use for such purposes any other streets or

public ways than those set out in said permit.

The two preceding paragraphs, however, shall not apply to

funeral processions.”

Hampshire, supra, 812 U. S. at 576, 61 S. Ct. at 766.

See Poulos v. State of New Hampshire, supra.

“ (20) But here it is clear that the practice in

Baton Rouge allowing unfettered discretion in local

officials in the regulation of the use of the streets for

peaceful parades and meetings is an unwarranted

abridgment of appellant’s freedom of speech and as

sembly secured to him by the First Amendment, as

applied to the States by the Fourteenth Amendment.

It follows, therefore, that appellant’s conviction for

violating the statute as so applied and enforced must

be reversed. (Emphasis supplied.)

“ For the reasons discussed above the judgment of

the Supreme Court of Louisiana is reversed.” Cox v.

Louisiana, 85 S. Ct. at page 466.

The statement from Cox v. Louisiana above quoted

serves to distinguish that case from the present one. It

also sei’ves to distinguish a host of other cases relied

upon by petitioner in his brief. Most of these are referred

to by Mr. Justice Goldberg in his statement (85 S. Ct. 453,

at page 464):

“ (10) Appellant, however, contends that as so con

strued and applied in this case, the statute is an un

constitutional infringement on freedom of speech and

assembly. This contention on the facts here pre

sented raises an issue with which this Court has

dealt in many decisions. That is, the right of a State

or municipality to regulate the use of city streets and

other facilities to assure the safety and convenience

of the people in their use and the concomitant right

of the people of free speech and assembly. See Lovell

v. City of Griffin, 308 IT. S. 444, 58 S. Ct. 666, 82 L. Ed.

949; Hague v. CIO, 307 IT. S. 496, 59 S. Ct. 954, 83 L.

Ed. 1423; Schneider v. State of New Jersey, 308 IT. S.

147, 60 S. Ct. 146, 84 L. Ed. 155; Thornhill v. State of

Alabama, 310 U. S. 88, 60 S. Ct. 736, 84 L. Ed. 1093;

Cantwell v. State of Connecticut, 310 U. S. 296, 60

S. Ct. 900, 84 L. Ed. 1213; Cox v. State of New Hamp

shire, 312 U. S. 569, 61 S. Ct. 762, 85 L. Ed. 1049; Lar-

gent v. State of Texas, 318 U. S, 418, 63 S. Ct. 667, 87

L. Ed. 873; Saia v. People of State of New York, 334

U. S. 558, 68 S. Ct. 1148, 92 L. Ed. 1574; Kovacs v.

Cooper, 336 U. S. 77, 69 S. Ct. 448, 93 L. Ed. 513;

Niemotko v. State of Maryland, 340 U. S. 268, 71

S. Ct. 325, 328, 95 L. Ed. 267, 280; Kunz v. People of

State of New York, 340 U. S. 290, 71 S. Ct. 312, 95

L. Ed. 280; Poulos v. State of New Hampshire, 345

IT. S. 395, 73 S. Ct. 760, 97 L. Ed. 1105.”

Petitioner also contends that this ordinance failed to

give him fair notice as to its proscriptions. The enact

ment here treated by petitioner as the “ ordinance” is the

last sentence of Section 1142:

“ It shall also be unlawful for any person to stand

or loiter upon any street or sidewalk of the city after

having been requested by any police officer to move.”

Even if this sentence is taken out of context and sepa

rated from the first sentence it is still a valid enactment.

An enactment almost identical to the above was consid

ered in the case of Tinsley v. City of Richmond, 202 Va.

707, 119 S. E. 2d 488. In that case as in this one, the at

tack was directed at the vagueness, ambiguity and lack

of standards in the ordinance.

It is admitted by the opinion in Tinsley that the ordi

nance does confer discretionary power on police officials

but the court pointed out the following exception:

“ We have, however, also recognized a well estab

lished exception to this rule. This exception applies

in instances where it is difficult or impractical to lay

down a definite or comprehensive rule, or where the

discretion relates to the administration of a police

regulation and is essential to the public morals,

health, safety and welfare.”

Another statement of this rule is found in Tinsley where

it quotes 12 A. L. R. 1435:

“ It is also well settled that it is not always neces

sary that statutes and ordinances prescribe a specific

rule of action, but, on the other hand, some situations

require the vesting of some discretion in public of

ficials, as for instance, where it is difficult or imprac

ticable to lay down a definite, comprehensive rule, or

the discretion relates to the administration of a po

lice regulation and is necessary to protect the public

morals, health, safety and general welfare.”

The general scope and authority of a police officer in

giving orders in the performance of his duties is dis

cussed in State v. Taylor, 119 A. 2d 36, 38 N. J. Sup. 6,

in the following language:

“ . . . The duty of police officers, it is true, is ‘ not

merely to arrest offenders, but to protect persons from

threatened wrong and to prevent disorder. In per

formance of their duties they may give reasonable di

rections.’ People v. Nixon, 248 N. Y. 182, 188, 161

N. E. 463, 466. Then they are called upon to deter

mine both the occasion for and the nature of such di

rections. Reasonable discretion must, in such mat

ters, be left to them, and only when they exceed that

discretion do they transcend their authority and de

part from their duty. The assertion of the rights of

the individual upon trivial occasions and in doubtful-

cases may be ill-advised and inopportune. Failure,

even though conscientious, to obey directions of a po

lice officer, not exceeding his authority, may interfere

with the public order and lead to a breach of the

peace.” People v. Galpern, 259 N. Y. 279, 181 N. E.

572, 83 A. L. R. 785 (Ct. App. 1932).

“ Failure to obey a police order to ‘ move on’ can be

justified only where the circumstances show conclu

sively that the order was purely arbitrary and was

not calculated in any way to promote the public order.

As was said in the Galpern case, the courts cannot

weigh opposing considerations as to the wisdom of a

police officer’s directions when he is called upon to de

cide whether the time has come in which some direc

tions are called for.”

Certainly in the handling of unforeseeable events officers

should be given reasonably broad discretionary powers.

This is especially true in the realm of traffic. Such ordi

nances afford sufficiently definite standards under the cir

cumstances and are neither vague nor overbroad.

Another question raised by petitioner is whether he was

in violation of Section 1142 at the time of his arrest, be

cause at that time the crowd was either moving or had

moved. Thus, contends petitioner the reason for his ar

rest was either gone or leaving. This however is no jus

tification. If petitioner, the leader of the group, had this

right then every other person in this crowd had the same

right and if every other person had this absolute right

then no right could rest in the City to regulate traffic on

its sidewalks. It is only logical to assume that if peti

tioner had been permitted to defy the officer1 and remain,

his companions would have construed this as an open in

vitation to rejoin him. Certainly if he had the right to

defy the order then each of the others in the crowd had an

5 The testimony shows that petitioner was not seeking informa

tion but was making statements in defiance of the officer (R. 18,

20. 41. 52).

— 24

equal right. Obviously such a situation would be intoler

able and gives justification to the rule that:

“ . . . police officers of a municipality should have rea

sonable authority and discretion. Indeed, in exigen

cies, it is vital to the welfare of the community.” 2

Benson v. City of Norfolk, 163 Va. 1037, 177 S. E. 222.

II-B.

THE LAST PARAGRAPH OF 1142 IS NOT VAGUE

OR OVERBROAD.

Petitioner in this section of his argument seeks reversal

of the conviction by attempting to attack the constitution

ality of 1142 as construed by the Alabama Court of Ap

peals to constitute but one offense to require proof of both

obstructing free passage and also failure to move upon re

quest of a police officer.

As heretofore noted in this brief, the last paragraph of

Section 1142 has been construed to contain a single of

fense, proof of which requires evidence that the accused,

blocked free passage of a public sidewalk and evidence of

his refusal to move on after a police officer’s request. City

v. Shuttlesworth, 42 Ala. App. 296, 161 So. 2d 796; Middle-

brooks v. City of Birmingham, . . . Ala. App. . . . , 170 So.

2d 424; Phifer v. City of Birmingham, 42 Ala. App. 282,

160 So. 2d 898. Respondent now directs its argument to

sustaining the validity of Section 1142 as construed by the

Appellate Courts of Alabama.

Petitioner’s first attack on Section 1142 is that the con

struction of this ordinance post-dates petitioner’s convic

2 The inevitable consequences of the implications of petitioner’s

argument in Shuttlesworth is that he has a constitutional right to

defy a police officer in performance of his duty, a doctrine, we

submit, which tends to encourage and may well lead to rioting, de

struction of property, in the hundreds of millions, violence, and

death of scores of innocent people.

tion in Circuit Court. In this regard he relies upon Bouie

v. City of Columbia, 84 S. Ct. 1697, 378 IT. S. 347. The

Bouie case, however, is not applicable in this ease. The

rule espoused in Bouie is simply that a statute written in

such narrow language as to give no fair notice to defend

ant that his conduct is proscribed cannot be subsequently

enlarged by judicial construction to cover his conduct.

Actually the specific rule of Bouie is just a different ap

plication of the following rule taken from United States v,

Harris, 347 U. S. 612, 617, 74 S. Ct. 808, 812, 98 L. Ed.

989, and adopted by Bouie:

“ The constitutional requirement of definiteness is

violated by a criminal statute that fails to give a per

son of ordinary intelligence fair notice that his con

templated conduct is forbidden by the statute. The

underlying principle is that no man shall be held

criminally responsible for conduct which he could not

reasonably understand to be proscribed.”

Section 1142 gives fair notice to any person of ordinary

intelligence that obstructing free passage on a sidewalk

and refusing to obey an officer’s request to move on is

illegal. The construction placed on this ordinance by the

Alabama Court is the only logical construction that could

be placed upon it.

The Court of Appeals in construing this ordinance

utilized rules of statutory construction designed solely to

reach the most logical reasonable construction. These

rules were formulated to give a certain amount of guid

ance to courts in their efforts to place logical and proper

construction on statutory enactments. They were designed

to insure that parties affected by statutes would have the

benefit of consistently logical construction. As stated in

Blair v. Greene, 246 Ala. 28, 18 S. 2d 688:

“ . . . (I)n the construction of a statute, the legis

lative intent is to be determined from a consideration

of the whole act with reference to the subject matter

to which it applies, and the particular topic under

which the language in question is found. The intent

so deduced from the whole will prevail over that of

a particular part considered separately. This is in

effect the statement as found in 59 C. J., p. 993, and

recognized as the correct principle by numerous deci

sions of this court.” The Alabama Supreme Court

in Peabody v. State, 246 Ala. 32, 18 So. 2d 693, also

applies this rule.

Certainly the rule above does no more than require those

persons coming within the purview of statutory enact

ments to use common sense in reading them. Unless one

completely blinds himself to the total effect of this enact

ment, no other conclusion can be reached other than the

one reached by the Appellate Courts of Alabama.

The title of this ordinance is an aid in its construction.

Wages v. State, 25 Ala. App. 84, 141 So. 709, Cert, denied

225 Ala. 10, 141 S, 713. The title of Section 1142 as

amended reads:

‘ ‘Streets and sidewalks to be kept open for free

passage.”

Certainly anyone reading the title of this ordinance

would know that its subject was obstructing sidewalks.

Anyone reading the entire ordinance would know that

both sentences, the first and second relate specifically to

some form of blocking traffic on the sidewalks and streets

and any order to move would be authorized only when

the first condition existed. It is only when the last sen

tence in this section is lifted and taken completely out

of context that the possibility of a different construction

appears.1 Appellant in this case, if he read the ordinance,

could not come to any conclusion other than the one

reached in the Middlebrooks, Phifer and Shuttlesworth

cases. He was given fair notice of its proscription.

In reply to the several references by petitioner in his

brief to the application of the prima facie rule and the

conclusion reached that viewing Ordinance 1142 as pro

scribing but one unlawful act of obstructing and failing

to move after obstructing passage on the sidewalk, the

Court would during trial presume obstructing from the

mere giving of the request to move, we feel such conclu

sion is erroneous. This erroneous conclusion is stated on

pages 22 and 23 of petitioner’s brief.

The Shelton case there mentioned dealt not with 1142,

but the vehicular traffic section 1231. The Middlebrooks

case dealt with an obstruction of the free passage on a

sidewalk, not in connection with a demonstration, but

after it was concluded. It is true, mention was made of

the Shelton case, but the Court of Appeals was unanimous

in its opinion that the evidence proved all of the elements

of the offense under 1142 without resorting to any question

of burden of proof.

It is also important to remember that in this, the

Shuttlesworth case, the Court of Appeals found from the

evidence the City had proved both of the elements re

quired to constitute the offense. Shuttlesworth could not

complain of such a rule, if such a rule exists, because

it obviously was not applied to his case in the decision

of that court in opinion written by Judge Cates.

1 The fact that the last sentence in Section 1142 as amended was

not a separate paragraph also is evidence that the request to move

mentioned therein necessarily relates to a failure of one who is

blocking or obstructing free passage to move after request to do so

by a police officer.

Petitioner also contends that Section 1142 is like the

ordinance declared invalid in Ex Parte Bell, 19 Cal. 2d

488, 122 P. 2d 22. It is true that the two ordinances have

some similarities, but the holding in Shuttlesworth and

Bell are easily distinguished. Ex Parte Bell dealt with

an ordinance that regulated picketing, which is a form of

free speech protected by the Constitution. Thornhill v.

State of Alabama, 310 U. S. 106, 60 S. Ct. 737. The Ala

bama Court of Appeals holds:

“ Section 1142, as amended, of the General City

Code of Birmingham is not aimed at free speech. It

directs the manner in which sidewalks and streets

may not be used.”

Absent the question of infringement of First Amend

ment freedom of speech, assembly or press,1 the only

requirement of specificity is that required to meet the

due process requirements of the Fourteenth Amendment

which is stated in Bouie, which quotes from the earlier

case of United States v. Harris, 347 U. S. 612, 617, 74

S. Ct. 808, 812, 98 L. Ed. 989, which we have quoted ante

page 25. This rule may be summarized as simply requir

ing that a defendant shall have reasonable notice of any

act proscribed and for which a penalty might be inflicted

upon him.

The ordinance here in question proscribing obstruction

of free passage on a sidewalk and requiring the violator

to move upon request of a police officer is as definite as

the nature of such ordinance allows. Any person of rea

sonable intelligence could understand its prohibitions.

Petitioner speculates that specific situations could arise

in which a person could be arrested for window shopping

or some other similar conduct and, if so, the police officer

1 See Fort v. Civil Service Comm, of Alameda County, 38 Cal.

Rptr. 625, 392 P. 2d 385.

29 —

would be applying the ordinance in an unconstitutional

manner. No one could deny that this or any ordinance

might be used improperly. But this fact could not con

demn an ordinance designed to accomplish a legitimate

control of the use of the streets and sidewalks to the

end that they might perform the main function for which

they were created.

The language of another California Appellate Court,

Ex Parte Bodkin, 194 Pac. 2d 588, 591, 86 Cal. App. 2d

208, is particularly appropriate:

“ (6) (7) To say that the test of any legislation is

what may be done thereunder without any limitation

whatever is an absurdity, for every conceivable class

of legislation has inherent in it the possibility of

unconstitutional acts of enforcement. The two cases

above cited referred to what would be the reasonable

permanent effect of the legislation. The rule, as

expressed by the Supreme Court, is that the state

may incidentally, by reasonable regulations for the

benefit of the general public, regulate but not pro

hibit the individual’s exercise of his civil rights.

(8) Since the ordinance here in question is solely

a regulation of the use of the public streets, preserv

ing them for the benefit of the public against ob

structions and not a restriction on what may be

uttered or published, the cases cited for the propo

sition that the state may not suppress civil liberties

except in conformity with the ‘ clear and present,

danger’ rule are not in point.”

In this regard, we also desire to call attention to an

other well established principle that only one against

whom an ordinance or statute has been unconstitutionally

applied, unless its language is such that it cannot other

wise be applied, may take advantage of its unconstitu-

tionality because of such improper application. Cox v.

30

Louisiana, 85 S. Ct. 453, 463; United States v. Raines,

362 U. S. 17, 80 S. Ct. 519, 522.

“ . . . one to whom application of a statute is con

stitutional will not be heard to attack the statute

on the ground that impliedly it might also be taken

as applying to other persons or other situations in

which its application might be unconstitutional.”

United States v. Raines, 362 U. S. 17, 80 S. Ct. 519.

522.

III.

Point III of Petitioner’s Argument Is Without Merit.

In his argument number III petitioner argues that the

first sentence of the last paragraph of Section 1142 is too

vague and overbroad to meet First-Fourteenth Amend

ment demands. He has no argument directed to this theory

except the statement adopting the argument from the pre

ceding “ paragraph” of his brief.

We feel respondent has fully answered these contentions

in Sections I and II of this brief. We therefore, adopt

these two sections in reply to this point or section of peti

tioner’s brief.

We have heretofore cited and quoted from the recent

decision of this Honorable Court in Cox v. State of Lou

isiana, 379 U. S. 536, 85 S. Ct. 453 (1965). We again direct

attention to this case because we feel it has particular

application here for the reason that there is great simi

larity in the statute there involved and the part of the

ordinance here under attack. Both by their terms pro

scribe loitering or standing so as to block or obstruct free

passage on the sidewalk. Neither the statute in Cox, nor

the first sentence of the last paragraph of 1142 which we

feel petitioner erroneously seeks to lift from its context and

attacks here, provides for warning by a police officer prior

to arrest.

31 —

While the statute in Cox was declared unconstitutional

it appeared to be so declared only because it had been con

strued by the Supreme Court of Louisiana as to apply to

public assemblies, conflicting with first amendment free

doms. Mr. Justice Goldberg discussed at length the dis

tinction between ordinances or statutes confined in lan

guage and application to merely regulating the flow of

traffic and those by force of language used or construction

by the state courts impinge upon first amendment free

dom.1

IV.

Point IV of Petitioner’s Argument Is Without Merit.

Petitioner in this section of his argument contends for

the reversal of the Alabama Court of Appeals decision

because of alleged lack of evidence in the record to sup

port a conviction under Count Two of the complaint. This

argument is without merits for two reasons.

A.

THE EVIDENCE AND INFERENCES PROPERLY TO

BE DRAWN THEREFROM SUPPORT A CONVIC

TION UNDER BOTH COUNTS ONE AND TWO.

Petitioner does not argue the invalidity of Ordinance

1231 of the City of Birmingham but in view of the narrow-

construction placed upon it by the Alabama Court of

Appeals does not question its validity but chooses to take

that court to task for holding the evidence sufficient to

support this Count Two in Shuttlesworth while holding to

to the contrary in Phifer v. City of Birmingham, 42 Ala.

App. 282, 160 So. 2d 898.

1 85 Sup, Ct. 453 and especially at pages 464-466,

As we understand the ruling of the Alabama Court of

Appeals, that court considered that defendant Phifer had

not been arrested on account of any incident related to

a traffic violation or because he obstructed free passage

on the sidewalk so as to force other pedestrians into the

street reserved for vehicular traffic but because he came

back to talk with Shuttlesworth after the latter’s arrest

and refused to leave after being warned three times to do

so. In dealing with absence of evidence to convict Phifer

under either Count One or Count Two, the Alabama Court

of Appeals reached the following conclusions:

“ (6) Although the arresting officer testified that

while he was pursuing Shuttlesworth into the store

the defendant Phifer disappeared and he could not

find him to arrest him at that time, we think it is

clear from all the evidence that the officer himself

did not consider that defendant had failed to comply

with his order to clear the sidewalk, since he did not

arrest him when he first came up to talk to Shuttles

worth, but kept urging him to ‘ move on’. We are of

the opinion the evidence fails to prove the defendant

guilty under count one of the complaint.

(7) The charge in the second count of the complaint

is for a violation of Section 1231, of the General City

Code of Birmingham. This section appears in the

chapter regulating vehicular traffic, and provides for

the enforcement of the orders of the officers of the

police department in directing such traffic. There is

no suggestion in the evidence that the defendant

violated any traffic regulation of the city by his re

fusal to move away from Shuttlesworth when ordered

to do so.

— 33

The evidence is insufficient to sustain the. verdict

under either count of the complaint.” 1

The evidence in Petitioner Shuttlesworth’s case is

exactly the reverse. It is clear he was arrested for ob

structing free passage on the sidewalk resulting in pedes

1 The opinion in Phifer v. City of Birmingham, 42 Ala. App.

282, 160 So. 2d 898, 900, 901, clearly quotes the evidence relied

upon by it to support these conclusions:

“ Shuttlesworth was placed in custody and taken to the west

curb to await transportation to the city jail, and while they

were standing there the defendant came up and started con

versing with Shuttlesworth. The witness told defendant Shut

tlesworth was under arrest and he could not be allowed to talk

with him, but Phifer continued to talk. The officer said: ‘ I

informed him if he did not move away and discontinue his

conversation with the defendant (Shuttlesworth) he too would

be placed under arrest and taken to the city jail.’ The witness

was asked on cross-examination :

‘Q. Now you arrested him at that time?’

‘A. After I had asked him to move some three times.’

‘Q. To move away from the Defendant Shuttlesworth?’

‘A. Yes, sir.’

‘Q. And only after he insisted on talking to Reverend Shut

tlesworth did you arrest him?’

‘A. That’s right.’

The witness stated further that six or seven police officers

were present when Shuttlesworth and Phifer were placed in

the police car.

One of these officers testified the arresting officer told

Phifer to move on, that he would not be allowed to talk to

Shuttlesworth. Phifer said 'I will go with him,’ and Officer

Byars stated: ‘You are under arrest too,’ The witness was

asked: Q. ‘What did he tell him he was under arrest for? ’

His answer was: ‘Refusing to obey the lawful command of an

officer.’

"Another officer testified; ‘He (Phifer) came up and said

he wanted to talk to Shuttlesworth, and Officer Byars told him

he couldn’t, that he was under arrest, and he said, “ Well, if

you do, 1 will have to arrest you too because 1 have told you

to leave.” And he said, “ Well, 1 will have to be arrested.” And

he placed him under arrest for failing to obey an officer.’

Two other officers testified it was after Officer Byars had

told Phifer twice to move on, that he couldn't talk to Shuttles

worth, that the defendant was arrested.”

trians having to get out, into the street reserved for

vehicular traffic, all in a group including Phifer and some

ten others. Phifer and the others obeyed the request of

the officer to cease obstructing free passage on the side

walk, hence none was arrested, except Phifer and his con

viction was reversed by the Alabama Court of Appeals.

The factual finding in Shuttlesworth v. City of Birming

ham, 42 Ala. App. 296, 161 So. 2d 796, 797, which is

amply supported by the evidence and inferences properly

to be drawn therefrom is stated:

“ The evidence, as introduced by the City, tended

to show that the defendant was a member of a

crowd of about ten or twelve people standing on the

corner of 19th Street and 2nd Avenue, North, in the

City of Birmingham, and that this crowd was block

ing the sidewalk to such an extent that some of the

other pedestrians were forced to walk into the street

to get around them. The; crowd was accosted by one

Officer Byars and asked to clear the; sidewalk so

as not to obstruct pedestrian traffic. The evidence

further showed that the crowd remained and when

requested to disperse for the third time by Officer

Byars, defendant Shuttlesworth said, ‘ You mean to

tell me we can’t stand here in front of this store!’

at which time, Officer Byars informed the defendant

that he was under arrest. Officer Byars testified that

at the time of the arrest everyone had moved or was

moving away except Shuttlesworth. After being told

that he was under arrest, Shuttlesworth moved away

saying, ‘ Well, I will go into the store.’ Officer Byars

then followed Shuttlesworth into Newberry’s Depart

ment Store and took him into custody.”

We respectfully urge that the Alabama Court of Appeals

was correct in holding both counts one and two are suffi

ciently supported by the evidence.

Review of the ruling of the Circuit Court denying the

motion of Shuttlesworth to exclude the evidence was

properly sustained because there was evidence before

the Court sufficient to make a prima facie case under

Counts One and Two.2 *

On certiorari, the ordinary practice of this Honorable

Court is not to review the weight or sufficiency of the evi

dence. On Page 19 of his brief petitioner alludes to and

concedes this practice.:i

Cases of the United States Supreme Court supporting

this rule include: Whitney v. California, 274 U. S. 397, 47

S. Ct. 641, 71 L. ed. 594; Milk Wagon Drivers Union v.

Meadowmoor Dairies, 312 IT. S. 287, 61 S. Ct, 552, 85 L. ed.

836; Portland R. L. & P. Co. v. Railroad Commission, 229

U. S. 397, 33 S. Ct. 829, 57 L. ed. 1248.

Of course, we are aware that if there was an entire

absence of any evidence showing the commission of any

offense charged by the City the principle asserted in

Thompson v. City of Louisville, 362 U. S. 199, 80 S. Ct. 624,

4 L. ed. 2d 654, would apply.

We think the evidence recited summarized by the Court

of Appeals of Alabama in the Shuttlesworth case4 which

we have quoted ante page 34 is more than adequate to

support a conviction of petitioner, Shuttlesworth, under

2 Tarver v. State, 85 So. 855, 17 Ala. App. 424; Drummond v.

State, 67 So. 2d 280, 37 Ala. App. 308; Martin v. State, 81 So.

851. 17 Ala. App. 73.

The statement is made by petitioner in connection with the

testimony of Officer Byars, which he says under ordinary practices

of this Court "must escape strict review here" (Brief, p. 19).

r 161 So. 2d 796, at page 797.

both Counts one and two of the complaint and is consistent

with the record in this case.5

But if we were to concede arguendo that the evidence

was not sufficient to convict under Count Two of the com

plaint, it was undoubtedly sufficient to convict under Count

One. In fact, we fail to find any serious contention of

insufficiency of evidence to support the complaint other

than the argument under Section IV of Petitioner’s brief

which is confined to Count Two.

B.

THE CONVICTION OP PETITIONER SHOULD BE

SUSTAINED EVEN IF THERE W AS COMPLETE

ABSENCE OP EVIDENCE TO SUSTAIN A

CONVICTION UNDER COUNT TWO.

The judgment entry appearing on pages 10 and 11 of

the record shows that petitioner was found guilty as

charged in the complaint, but was fined and sentenced for

one offense only. That is, the sentence was the same

whether rested upon Count one or Count two.6

5 The evidence is considered in “ Statement of the Case’’ , this

brief, ante pages 2-8.