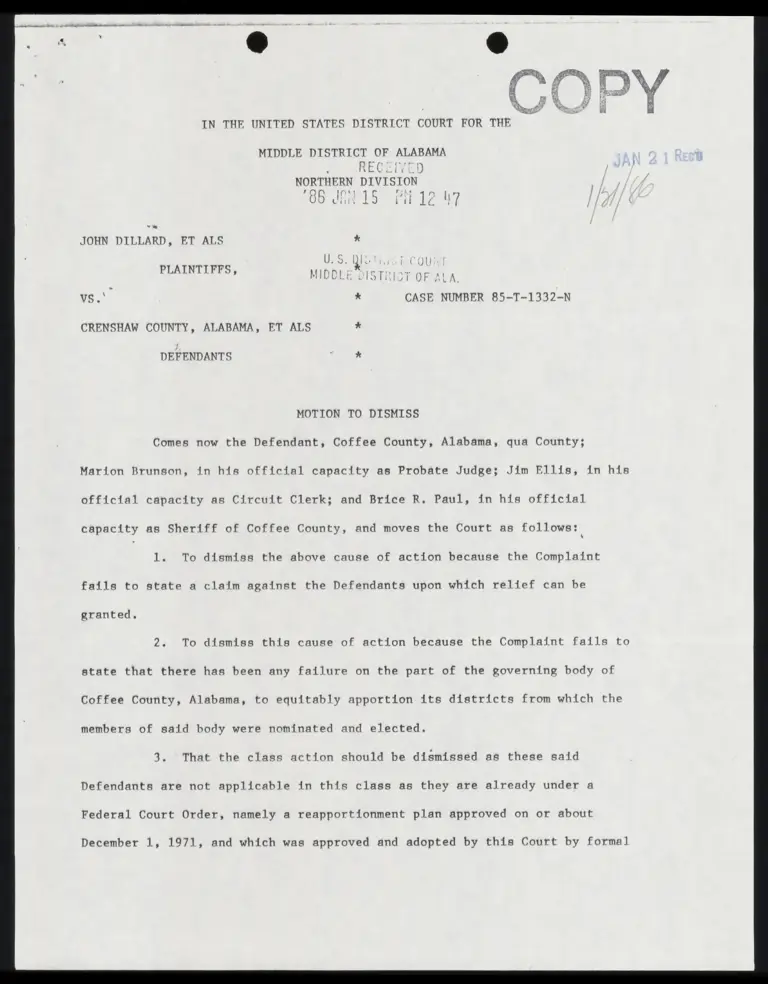

Motion to Dismiss

Public Court Documents

January 21, 1986

6 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Dillard v. Crenshaw County Hardbacks. Motion to Dismiss, 1986. a5b00d2a-b9d8-ef11-a730-7c1e5218a39c. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/732e45b6-a1cd-462d-a0de-814af60fc203/motion-to-dismiss. Accessed February 28, 2026.

Copied!

vv y Fs Es

iN 5% & po ‘ Wl hr 3 |

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE

MIDDLE DISTRICT OF ALABAMA

RECZIVED

NORTHERN DIVISTON

86 Ji 15 Fi 12 U7

“mn

JOHN DILLARD, ET ALS +

U.S. Qictiici col

PLALRTIFE®) MIDDLE CISTRICT OF ALA.

vs." * CASE NUMBER 85-T-1332-N

CRENSHAW COUNTY, ALABAMA, ET ALS *

DEFENDANTS LE

MOTION TO DISMISS

Comes now the Defendant, Coffee County, Alabama, qua County;

Marion Brunson, in his official capacity as Probate Judge; Jim Ellis, in his

official capacity as Circuit Clerk; and Brice R. Paul, in his official

capacity as Sheriff of Coffee County, and moves the Court as follows:

1. To dismiss the above cause of action because the Complaint

fails to state a claim against the Defendants upon which relief can be

granted,

2. To dismiss this cause of action because the Complaint fails to

state that there has been any failure on the part of the governing body of

Coffee County, Alabama, to equitably apportion its districts from which the

members of said body were nominated and elected.

3. That the class action should be dismissed as these said

Defendants are not applicable in this class as they are already under a

Federal Court Order, namely a reapportionment plan approved on or about

December 1, 1971, and which was approved and adopted by this Court by formal

Order entered on December 22, 1971. (See attached Exhibit A). This said, res

judicata and collateral estoppel are appropriate as to these Defendants.

4. That the Defendants do not waive any other grounds that they

might have in different Motions to Dismiss.

"

ROWE, ROWE & SAWYER

C

BY: 0) A pen

Warren Rowe

Rowe, Rowe & Sawyer

P.. 0. Box 150

Enterprise, Alabama 3633]

(205) 347-3401

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

1, Warren Rowe, hereby certify that I have mailed a copy of the

foregoing Motion to Dismiss to all counsel of record by placing a copy of the

game in the United States mail, postage prepaid and properly addressed to

them this the [4 day of January, 1986.

Of” Counsel

pT i Sa 4 id _ TRY EARP

i oh

hj

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FCR THE {IDLE

DISTRICT OF ALABAMA, SOUTHERN DIVISIO!

FILED

DEC 22 1971

I aii P. GGRDON, CLERK

J. COMER SIMS, WILBUR WARREN,

G. E. ALLEN, CHARLES

McGLOTHREN, LUTHER MARTIN

MOATES, ROYCE HERRINGTON and

JAMES M, SPEIGNER, for themselves,

jointly and severally, and for

all others similarly situated,

ny

Plaintiffs,

vs. . CIVIL ACTION NO. 1170-S

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

WILLIAM J. BAXLEY, Attorney )

General of the State of Alabama; )

ROBERT S. VANCE, Chairman of the )

Alabama State Democratic Executive )

Comr!ttee; J. R. BENNETT, JR., ) 4

Che. rman of the Alabama State )

Republican Executive Committee; )

JAMES L., SAWYER, Judge of Probate )

of Coffee County, Alabama; )

RALPH SPARKS, Sheriff of Coffee )

County, Alabama; JACKSON W, STOKES, )

Chairman of the Coffee County Demo-=- )

cratic Executive Committee; T, R, )

BOWDOIN (BOWDEN), Chairman of the )

Coffee County Republican Executive )

Committee; and ALBERT G. DYESS, )

BYRON B. GALLOWAY, FLOURNOY )

WHITMAN, BUSTER BOWDEN, as )

members of the Coffee County )

Commissioners Court, )

)

) Defendants,

Se o— w—— ww

This action has been initiated by J, Comer Sims and pther

citizens of the United States and of the State of Alabama, who reside in

Coffee County, Alabama and who are duly qualified and registered electors in

said State and County, Plaintiffs bring this action on their own behalf and on

behalf of all other qualified electors in Coffee County who plaintiffs claim are

denied the right of free and equal suffrage and of equal protection of the laws.

Defendants include William J. Baxley as Attorney General of Alabama; Robert S.

Vance and J. R, Bennett, Jr.,, as the Chairmen of the Alabama State Democratic

and Republican Executive Committees, respectively: James L. Sawyer as Judge of

Probate of Coffee County and as ex officio Chairman of the County Commission of

Coffee County; Ralph Sparks as Sheriff of Coffee County; Jackson W, Stokes and

T. R. Bowdoin as the Chairmen of the Coffee County Democratic and Republican

Lieentive Committees, respectively; and Alber: G., Dyess, Pvron 2. C~1lowav,

Flournoy Whitman and Buster Bowden as the duly elected, qualified and acting

members of the County Commission of Coffee County.

In bringing this action, plaintiffs have attacked the apportion-

ment of the County Commission of Coffee County as established by Act No. 630

of the 1927 Regular Session of the Alabama Legislature and by Act No. 571 of the

1953 Regular Session of the Alabama Legislature. Under the provisions of these

acts, the County wads divided into four districts of widely varying populations,

each entitled to one seat on the Commission, Although the commissioners were to

be elected from the County at large, each member of the Commission was required

to be a resident and a qualified elector of the district from which he was elected

By order entered October 18, 1971, this Court declared the sppot tlonnent created

by these =cts void and violative of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution

of the United States, In reaching its decision, this Court found from the matters

presented to it at the pretrial hearing that each district's resident on the

Commission represented, in fact, only his district and not the County as a whole,

See Dusch v, /‘Davis, 387 U.S, 112 (1966), Consequently, the Court ordered the

County Commission of Coffee County to promulgate a plan remedying the consti-

tutional infirmities extent under the past selene The Commission filed its

proposed plan (hereinafter referred to as defendants’ plan) on December 1, 1971,

and on December 20, 1971, this cause proceeded to a hearing at which the parties

presented evidence, both oral and documentary, The case now is submitted upon

the pleadings, the evidence, the defendants’ plan and the briefs of the parties.

The defendants' plan maintains the four commission districts as

presently constituted, It provides, however, for six, rather than. four, members

on the County Commission, three of whom must reside in district 4, the most

populous district, Plaintiffs argue that this plan is constitutionally unaccept-~

able because it fails to provide for votes of substantially equal weight as

2 required by the United States Supreme Courts Bf See Avery v. Midland County,

1/ Act No, 1259, House Bill 2695, 1971 Regular Session, Legislature of Alabama,

authorizes and empowers the Coffee County Commission to divide or redivide

Coffee County into commission districts "and to otherwise provide for the

election of the members of the Commission."

2/ The voting populations of the four commission districts are as follows:

District 1 has 998 qualified and registered voters; district 2 has 1,280;

district 3 has 4,546 and district 4 has 9,327.

BN at Aa _— a aa A v ie

390 U.S. 474 (1968); see also Kirkpatrick v, Preisler, 394 U.S. 526.

This Court is not persuaded by plaintiffs' argument, Tisch v,

Davis, supra, held that an otherwise nondiscriminatory plim is not invalid

when it uses districts "merely as the basis of residence for candidates, not

for voting or representation", since each commissioner represents the county

as a whole and not just the district in which he resides. See also Goldblatt

v. Dallas, 414 F.2d 774 (5th Cir. 1969); Taylor v. Monroe Co. Bd. of Spvrs.,

394 U.S, 333 (5th Cir, 1968), Although the plaintiffs' evidence in this case

disclosed that under the previous apportionment of Coffee County, the commissioners

functioned primarily as administrators of the County road amd bridge construction

program, that at least with regard to that function each commissioner, in fact,

represented only his own district, and that such apportionment discriminated

against residents of district 4, this Court finds that defemdants' proposed

plan provides a proper mechanism through which past deficiemcies may be rectified,

Pursuant to defendants' new apportionment scheme, district & is afforded three

of the six seats on the County Commission. In addition, the County Judge of

Probate, who serves as ex officio Chairman of the Commissiom and who votes

to break ties, runs for office from the County at large and, consequently, is

most likely to be a resident of district 4, When the Probate Judge is a resident

of that district, as is the present Probate Judge, district %4 will have a

majority of the votes on the Commission. Thus, under defendants' proposed plan,

nothing can prevent the Commission from administering its road construction and

maintenance program, ag well as all other of its functions, on a county-wide

basis. The commissioners have the authority to ensure that each of them, in

fact, roprevents the County as a whole,

In objecting to defendants' plan, plaintiffs suggest that under

Alabama law the Commission may lack the authority to add two seats to its

composition, See Act No, 1259, House Bill 2695, passed in the 1971 Regular

Session of the Alabama Legislature, approved by the Governor on September 22,

1971. This Court concludes that the Commission does have such power. Should

this conclusion prove incorrect, however, the judgment rendered here still will

be valid as the Court, having decided upon the proper disposition of this case,

adopts defendants' proposed plan as the plan of the Court. The plan is adopted,

of course, with the understanding that the vote of each commissioner will be

equal to the vote of each other commissioner.

Ia 47 APPT SS Nl GAN AAR SALA eC a A i Bod ln kal Bik i ia i andl BT EA A

R%

.

Accordingly, it is the ORDER, JUDGMENT and DECREE of this Court:

l. That the defendants, t._ir successors in oificc, :-.1 those

acting in their behalf or in concert with them, be and each is hereby enjoined

from failing to conduct or failing to cause to be conducted, in 1972, an election

for the commissioners of the Coffee County Commission in accordance with the

following apportionment plan:

The Coffee County, Alabama commission districts

shall remain as presently constituted in four

districts, The Coffee County Commission shall be

composed of six commissioners, one of whom must be

a resident and qualified elector of district 1 as

it is now composed and constituted; one of whom

must be a resident and qualified elector of district

2 as it is now composed and constituted; one of

: whom must be a resident and qualified elector of

. district 3 as it 1s now composed and constituted;

and three of whom must be residents and qualified

electors of district 4 as it is now composed and

constituted; all of whom shall be elected by the

qualified electors of the entire County at large

at the time and in the manner prescribed by law,

The vote of each commissioner on the Coffee County

Commission will be equal to the vote of each other

> | commissioner, i

It is the further ORDER, JUDGMENT and DECREE of this Court:

+ 1. That the apportionment of the Coffee County, Alabama Commission,

as herein ordered and directed, shall be effective upon the filing of this

decree, with the terms of office of those elected to the Commission seats as

herein established to commence on the day after the general election to be

held in November, 1972;

2, That jurisdiction of this cause be and the same is hereby

retained for all purposes,

It is further ORDERED that the court costs incurred in this pro-

ceeding be and they are hereby taxed against the defendants.

Done, this the 22nd day of December, 1971,

pr (Gene ude

UNITED STATES DISTRICT JUDGEX