Lee v. Brown Appellants Brief and Appendix

Public Court Documents

November 22, 1963

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Lee v. Brown Appellants Brief and Appendix, 1963. a42972ec-ba9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/733e6f29-9b47-44cc-8e7a-0410628d003e/lee-v-brown-appellants-brief-and-appendix. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

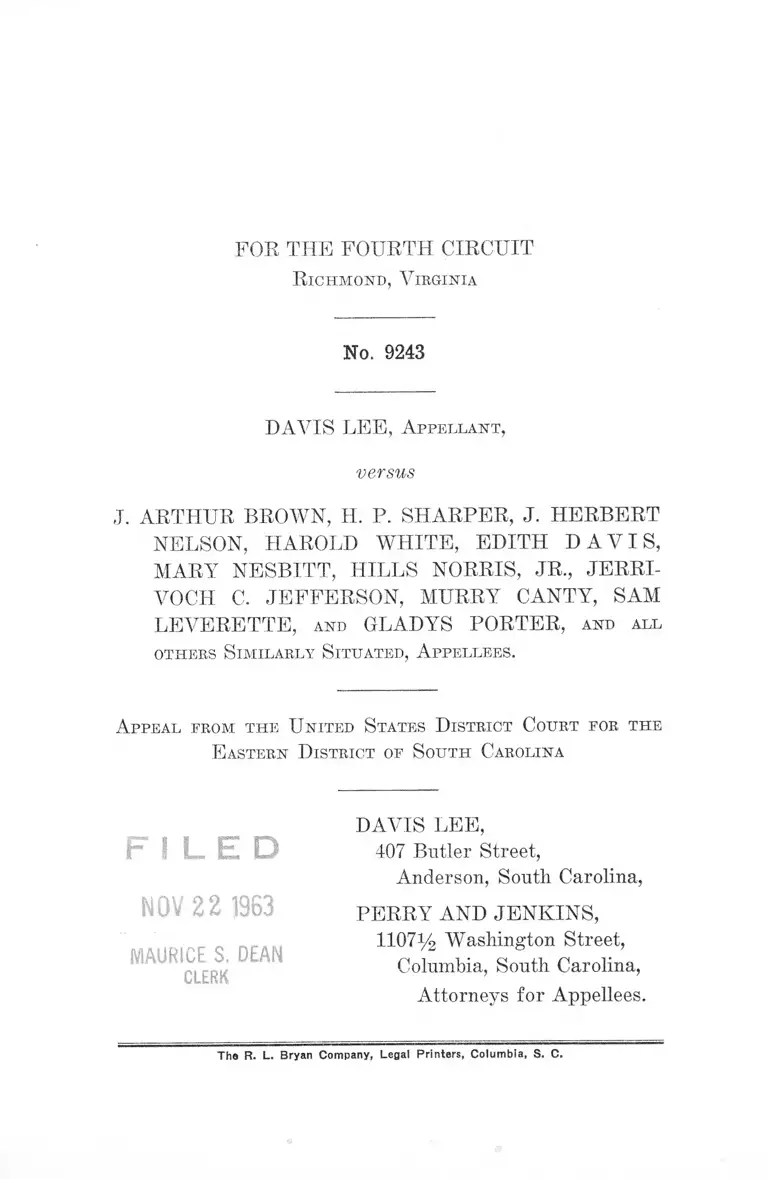

APPELLANT’S BRIEF

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

R ichmond, V irginia

No. 9243

DAVIS LEE, A ppellant,

versus

J. ARTHUR BROWN, H. P. SHARPER, J. HERBERT

NELSON, HAROLD WHITE, EDITH D A V I S ,

MARY NESBITT, HILLS NORRIS, JR., JERRI-

VOCH C. JEFFERSON, MURRY CANTY, SAM

LEVERETTE, and GLADYS PORTER, and all

others Similarly Situated, A ppellees.

Appeal from the United States D istrict Court for the

E astern District of South Carolina

F I L E D

N O V Z l 1963

M AURICE S. D EAN

CLERK

DAVIS LEE,

407 Butler Street,

Anderson, South Carolina,

PERRY AND JENKINS,

1107% Washington Street,

Columbia, South Carolina,

Attorneys for Appellees.

The R. L. Bryan Company, Legal Printers, Columbia, S. C.

INDEX

P age

Statement of the C a se ......................................................... 1

Motion for Declaratory Judgment and G rounds............ 3

Letter of John C. R o g e rs ................................................... 5

Specifications of Errors ..................................................... 6

Argument and Authorities................................................. 7

Conclusion ............................................................................ 14

Appendix .............................................................................. 15

( i )

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

P age

Aetna Life Insurance Co. v. Haworth, 300 U. S. 227, 241,

57 S. Ct. 4 6 1 ................................................................. H

Clark v. Memolo, C. A. D. C. 1949, 174 F. (2d) 978 . . . . 11

Delaney v. Carter Oil Co., C. A. Okla., 1949, 174

F. (2d) 3 1 4 ................................................................... 10

Doehler Metal Furniture Co. v. United States, 2 Cir., 149

F. (2d) 130, 135 ................................................................. 7

Fash v. Clayton, D. C. N. M., 1948, 78 F. Supp. 359 . . . . 11

Fountain v. Filson (1949), 336, 681, 69 S. Ct. 754, 93

L. Ed. 971, 12 Fed. Rules Service, 56, Case 2 .............. 7

Lloyd v. United Liquors Corp., 203 F. (2d) 789 ............ 8

Morgan, J. A. and Morgan Myra S., Aug. 9th, 1963, 5th

Circuit, Cited as 321 F. (2d) 7 8 1 ................................. 8

Maryland Casualty Company v. Pacific Coal and Oil Co.,

312 U. S. 270, 273, 61 S. Ct. 5 1 0 ..................................... 11

Sartor v. Arkansas Natural Gas Corp., 321 U. S. 620,

624, 64 S. Ct, 724, 88 L. Ed. 967 ..................................... 8

Shultz v. Manufacturers Trust Co. (W. D. N. Y.), 1939,

30 F. Supp. 443 ................................................................. 7

Timmons v. United States, C. A. S. C. 1952, 194 F. (2d)

357 ....................................................................................... 10

United States v. Bazell, U. S. Court of Appeals, 7th

Circuit, March 5, 1962, Cited as 194 F. (2d) 745 ........ 8

Steingut v. National City Bank of New York, D. C. N. Y.

1941, 36 F. Supp. 486 ....................................................... 12

( i i )

APPELLANT’S BRIEF

United States Court of Appeals

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

R ichmond, V irginia

No. 9243

DAVIS LEE, A ppellant,

versus

J. ARTHUR BROWN, H. P. SHARPER, J. HERBERT

NELSON, HAROLD WHITE, EDITH D A V I S ,

MARY NESBITT, HILLS NORRIS, JR., JERRI-

VOCH C. JEFFERSON, MURRY CANTY, SAM

LEVERETTE, and GLADYS PORTER, and all

others Similarly Situated, A ppellees.

A ppeal from the United States District Court for the

E astern D istrict Of South Carolina

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

This is an appeal by Davis Lee, defendant by interven

tion in the District Court. The Plaintiffs filed a complaint

in the lower court against the South Carolina State For

estry Commission, the Commission members and the State

Park officials, as a class action, July 8, 1961, seeking to

have the 26 State Parks integrated.

On July 11,1961, three days later, this appellant filed a

motion in the District Court to intervene as a defendant

upon the grounds that he was similarly situated like the

2 Lee, A ppellant, v. Brown et al., Appellees

approximately 900,000 other Negro eitizens, and that he had

a defense presenting both questions of law and of fact

which were Common to the main action.

Before the court heard the motion October 12, 1961,

the appellant filed an amended answer on October 12, 1961.

The court granted the motion to intervene as a matter of

right, and the order made this appellant subject to any

judgment just as the other defendants.

On February 5, 1962, the appellant filed a motion to

bring in additional parties, and at the same time the appel

lant filed a motion for leave to file a supplemental answer

and counterclaim. The proposed counterclaim was filed as

an attachment to the latter motion.

While hearings had been scheduled on all pending mo

tions at several different terms of court, none were heard

until April 18, 1963. A hearing was held on that date on a

motion by the plaintiffs for summary judgment.

At the April 18, 1963, hearing, the court proceeded to

dispose of all pending motions by plaintiffs and original

defendants. The record of the proceedings will show that

this appellant was deliberately, intentionally, and purposely

excluded from all participation in the matter.

The hearing was conducted in such a manner as to give

the impression that this appellant was a complete outsider

and had no connection or interest in the matter.

The plaintiffs and original defendants concluded their

part of the hearing during the morning session. This appel

lant was heard during the afternoon session.

The court did not hear argument on all of the pending

motions, and the court did not ask for argument on each

individual pending motion. The appellant explained that he

could offer no defense or say anything about the pleadings

on file by either the plaintiffs or original defendants because

Lee, Appellant’, v. Brown et al., Appellees 3

neither had followed Rule 5 of the Federal Rules of Civil

Procedure and sent him copies of the pleadings.

The court gave each side time to file additional briefs

in support of their positions.

Because the court’s handling of the matter departed so

far from well known rules of Federal Civil Procedure, the

appellant not only filed a supporting brief on May 10th,

1963, in which he referred to the violation of these rules,

but on May 23rd, 1963, the appellant filed a motion for De

claratory Judgment under Title 28, sections 2201-2202,

United States Code, and under Rule 57, Federal Rules of

Civil Procedure.

MOTION FOR DECLARATORY JUDGMENT

AND GROUNDS

Filed May 23rd, 1963

Comes now, Davis Lee, defendant by intervention, set

ting forth herein grounds in support of this motion for De

claratory Judgment:

1. That while this court granted his motion to intervene

which gave him all of the rights enjoyed by the original

defendants, counsel for plaintiffs and defendants, have vio

lated Rule 5 of The Federal Rules of Procedure, and have

failed to send this intervener copies of all pleadings filed

in this case.

2. That counsel for plaintiffs filed a motion for Sum

mary Judgment and set forth the purpose for the motion.

During the hearing on April 18, 1963, counsel called two

witnesses to testify, yet they did not indicate any such in

tention in the moving papers. Thus they violated Rule 7 of

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure which specifically states,

section (a) that all motions “ shall state with particularity

the grounds therefore.”

4 Lee, Appellant, v. Brown et al., Appellees

3. That this defendant by intervention has several affi

davits by Negro citizens who feel as he does; some have

expressed desire to appear and testify that these plaintiffs

do not represent them in this class action, but because coun

sel for plaintiffs did not indicate their intention to call wit

nesses, these citizens were not notified to appear.

4. That during the hearing April 18, 1963, on plaintiffs’

motion for Summary Judgment, this defendant by interven

tion was completely, intentionally and purposely excluded

from any participation in the proceedings to the extent that

a special afternoon session of the court was held to hear this

intervenor. Since Rule 24 of The Federal Rules of Civil

Procedure endow intervention by right with the same rights

and privileges as an original party, the proceedings on the

above date deprived this intervenor of the due process guar

anteed by the 5th Amendment.

5. That because this intervenor did not object to the

proceedings on April 18th does not constitute a waiver of

his rights; he was denied an opportunity to assert them.

The morning session was exclusively confined and limited

to arguments by counsel for plaintiffs and original defend

ants and this intervenor was completely ignored by all

counsel, and the court and given a separate hearing in the

afternoon that dealt with his motions, and not with the

motion for Summary Judgment.

6. That because counsel for plaintiffs and for original

defendants have failed to send this intervenor copies of all

pleadings which is mandatory under Rule 5, he has been

deprived of his right to offer an intelligent, adequate de

fense to protect his interest in this cause.

7. Because of the evident confusion or lack of com

plete understanding of the role of an intervenor; and be

cause this intervenor has been deprived of his rights under

Rule 24, 5 and 7, he now seeks a hearing on this motion for

Lee, A ppellant, v. Brown et al., Appellees 5

Declaratory Judgment, for the purpose of clarifying the

legal relations in issue. He seeks relief from the uncertainty,

confusion and misunderstanding of the issues involved, and

he seeks an opportunity to include in the record the affida

vits of Negro citizens who are not represented by this main

action, and to have others to appear and testify in person.

May 23, 1963.

DAVIS LEE,

Defendant by Intervention,

And Counsel,

407 Butler Street,

Anderson, S. C.,

On May 24, 1963, Mr. John C. Rogers, Chief Deputy

Clerk sent out the following letter to counsel for plaintiffs

and original defendants.

Office of the Clerk

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

Eastern District of South Carolina

Columbia

May 24, 1963

Mr. Davis Lee

Attorney at Law

Anderson, South Carolina

Re: Brown et al. v. 8. C. State Forestry Commission et al.

Civil Action No. AC-774.

Dear Mr. Lee:

The original and copies of Notice of Motion for De

claratory Judgment and Motion for Declaratory Judgment

and Grounds on behalf of Intervener, Davis Lee, in the

above case were received and filed here today.

6 Lee, A ppellant, v. Brown et al., Appellees

Pursuant to your request, I am forwarding copies to

other counsel in the case.

Yours truly,

JOHN C. ROGERS,

Chief Deputy Clerk.

JCR/c

CC. HON. DANIEL R. McLEOD,

MR. D. W. ROBINSON,

MESSRS. JENKINS & PERRY.

On July 10th, 1963, 47 days after the appellant filed his

motion for declaratory judgment, the court issued its order

against the defendants, but the court said not one word

about the appellant’s motion for declaratory judgment. The

motion has never been ruled on.

SPECIFICATIONS OF ERRORS

1. The court erred by hearing motion for Summary

Judgment before hearing motions by this appellant so that

record was complete.

2. The court erred by treating this appellant as an

outsider instead of as a defendant with equal standing with

other defendants, enjoying the same rights as they.

3. The court erred, when informed that copies of plead

ings had not been served this appellant, when it failed to

issue an order directing all counsel to give this appellant

copies of all pleadings on file so he would be in a position

to prepare a defense.

4. The court erred when it refused to grant this appel

lant a hearing on his motion for Declaratory Judgment.

5. The court erred when it permitted appellees to place

witnesses on the stand to testify at the hearing on motion

for Summary Judgment, April 18, 1963, when counsel had

not indicated such intention in its grounds for motion.

Lee, A ppellant, v. Brown et al., Appellees 7

6. The court erred when it denied this appellant his

right to file a counterclaim against these appellees and

others within the jurisdiction of the court.

7. The court erred when it denied the appellant the

right to participate in the main action, and held a special

afternoon session for the specific purpose of hearing him

after counsel for the main defendants had left; that this

action constituted denial of due process and equal protec

tion guaranteed by the Constitution.

ARGUMENT AND AUTHORITIES

Appellant’s Point No. 1

The trial court erred by hearing motion for Summary

Judgment before completion of the record. This appellant,

in a sense, was placed in the same position as in Fountain

v. Filson (1949), 336, 681, 69 S. C. 754, 93 L. Ed. 971, 12

Fed. Rules, Service, 56, Case 2, where the court reversed a

decision of the Court of Appeals ordering a summary judg

ment where the order was made on appeal on a new issue

as to which the opposite party had no opportunity to pre

sent a defense before the trial court.

In the case at bar the court should have postponed con

sideration of the motion to afford this appellant ample time

to offer an adequate defense. See Shultz v. Mcmufacturers

Trust Co. (W. D. N. Y., 1939), 40 F. Supp. 443.

The Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit, in

Doehler Metal Furniture Co. v. United States, 2 Cir., 149

F. (2d) 130, 135, cautioned trial courts concerning the sus

taining of motions for summary judgments in the following

language:

“ We take this occasion to suggest that trial judges

should exercise great care in granting motions for sum

mary judgment. A litigant has a right to a trial where

there is the slightest doubt as to the facts, and a denial

of that right is reviewable. Such a judgment, wisely

8 Lee, A ppellant, v. Brown et til., Appellees

used, is a praiseworthy, time saving device. But,

although prompt dispatch of judicial business is a vir

tue, it is neither the sole nor the primary purpose for

which courts have been established. Denial of a trial on

disputed facts is worse than delay.”

Lloyd v. United Liquors Corp., cited as 203 F. (2d) 789. See

also Sartor v. Arkansas Natural Gas Corp., 321 U. S. 620,

624, 64 S. C. 724, 88 L. Ed. 967.

We wish to direct the court’s attention to United States

v. Bazell, United States Court of Appeals, 7th Circuit,

March 5, 1952, cited as 194 F. (2d) 745. Here a summary

judgment was granted by the District Court to the plain

tiffs while the defendant’s motion for Declaratory Judg

ment was pending. The Court reversed and remanded to

give defendant an opportunity to be heard.

The appellant takes the position that the Summary

Judgment was prematurely granted, and that the court com

pletely disregarded his rights in its efforts to comply with

the wishes of The NAACP, which has both money and poli

tical influence, where as the appellant is a little publisher

with neither money or influence, and because of this he was

not heard according to the rules of Federal Civil Procedure.

The plaintiffs moving for Summary Judgment had

burden of demonstrating clearly that there was no genuine

issue of fact—J. A. Morgan and Myra S. Morgan, Aug. 9,

1963, 5th Circuit, cited as 321 F. (2d) 781.

How could the plaintiffs demonstrate that there was no

genuine issue of fact when the record had not been com

pleted, motions pending by this appellant had not been

argued and ruled upon, so that examination of the completed

record would determine whether there was no genuine issue

of fact?

Lee, A ppellant, v. Beown et at, Appellees 9

Appellant’s Point No. 2

The appellant in this cause filed a timely motion to in

tervene as a defendant under Rule 24 (A ) (1) (A) (2) and the

order granting his motion is an absolute one; that an inter-

venor under this order is put in the same position as the

original defendants, and with the same rights and privi

leges.

Moore’s Federal Practice, Vol. 2, page 2381 has this to

say about rights of an absolute intervenor:

Finally the intervenor may desire to question the

merits of a claim or defense. Thus he may desire (1) to

question whether the allegations of The Complaint are suffi

cient, or (2) to contest a claimant’s rights to a certain

amount of damages, or (3) to press a claim of his own which

will have the effect of reducing the value of other claims.

“ There seems to be no doubt that an intervenor having

an absolute right to intervene is able to raise any one of

these questions. It would be meaningless to give him an

absolute right to intervene in order to protect his interest,

if once in the proceeding he were barred from raising ques

tions necessary for his own protection.”

Barron and Holtzoff in Federal Practice and Proced

ure, Vol. 2, section 593, page 359, says:

“ An intervenor takes the case as he finds it and to

all intents and purposes is regarded as an original

party, except that he may not question the venue or

jurisdiction of his person. However, intervention pre

supposes the pendency of an action in a court of com

petent jurisdiction and intervention will not be allowed

to create jurisdiction where none existed before.”

Appellant’s Point No. 3

The Court was properly informed at the hearing on

April 18, 1963, and subsequently in a requested brief, that

this appellant had not been sent copies of the pleadings on

10 Lee, Appellant, v. Brown et al., Appellees

file. Then, how could he be expected to present any kind of

defense when he did not know what was in the record?

Title 28, Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, Rule 5 (A)

Service states: “ Every order required by its terms to be

served, every pleading subsequent to the original complaint

unless the court otherwise orders because of numerous de

fendants, every written motion other than one which may be

heard ex parte, and every written notice, appearance, de

mand, offer of judgment, designation of record on appeal,

and similar paper shall be served upon each of the parties

affected thereby, but no service need be made on parties

in default for failure to appear except that pleadings new

or additional claims for relief against them shall be served

upon them in the manner provided for service of summons

in Rule 4.”

The strictest and most exacting compliance with this

rule as to methods of service of pleadings is required when

service is made by mail. Timmons v. United States, C. A.,

S. C., 1952,194 F. (2d) 357.

Appellant’s Point No. 4

The appellant was entitled to a hearing on his motion

for Declaratory Judgment.

The purpose of declaratory procedure is to remove un

certainty from legal relations and clarify, quiet and sta

bilize them before irretrievable acts have been undertaken,

and also to enable an issue of questioned status or fact, on

which a whole complex of rights may depend, to be expedi

tiously determined. Delaney v. Carter Oil Co., C. A. Okla.,

1949, 174 F. (2d) 314.

The Declaratory Judgment Act was designed to pro

vide a remedy in a case or controversy while there is still

opportunity for peaceful judicial settlement, and its pri

mary purpose was to have a declaration of rights not there

Lee, A ppellant, v . Brown et at, Appellees 11

tofore determined, and not to determine whether rights

theretofore adjudicated have been properly adjudicated—

Clark v. Memolo, C. A. D. C., 1949, 174 F. (2d) 978. Also

see Fash v. Clayton, D. C., N. M., 1948, 78 F. Supp. 359.

On what legal or procedural basis could the court com

pletely ignore the motion, and issue a lengthy order, and

not even mention the appellant’s motion for Declaratory

Judgment?

The Declaratory Judgment Act requires a case of

actual controversy. As Chief Justice Hughes stated in

Aetna Life Insurance Co. v. Haworth, 300 IT. S. 227, 241,

57 S. C. 461:

“ It must be a real and substantial controversy ad

mitting of specific relief through a decree of a conclu

sive character, as distinguished from an opinion ad

vising what the law would he upon a hypothetical state

of facts.”

And Mr. Justice Murphy wrote in Maryland Casualty

Co. v. Pacific Coal £ Oil Co., 312 TJ. S. 270, 273, 61 S. C. 510:

“ Basically, the question in each case is whether the

facts alleged, under all the circumstances, show that

there is a substantial controversy between parties ad

verse legal interest, of sufficient immediacy and reality

to warrant the issuance of a declaratory judgment.”

When the court refused to acknowledge existence of

appellant’s motion, and refused to hold a hearing on it, the

appellant was denied the opportunity and the right to show

that there was a substantial controversy. Because of the

evident State of Confusion the appellant was entitled to

specific relief through a decree of a conclusive character,

and a judicial clarification of his status.

12 Lee, A ppellant, v. Brown et al., Appellees

Appellant’s Point No. 5

The appellees filed a motion for a summary judgment

and set forth the grounds upon which the motion was filed.

There was nothing in the motion to indicate that they in

tended to place witnesses on the stand.

Rule 7 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure states:

(B) 1 “ An application to the court for an order shall he by

motion which, unless made during a hearing or trial, shall

be made in writing, shall state with particularity the

grounds therefor, and shall set forth the relief or order

sought. The requirement of writing is fulfilled if the motion

is stated in a written notice of the hearing of the motion.”

All motions are subject to requirement of rules that

they state with particularity the grounds therefor— U. S. v.

64-88 Acres of Land., more or less, situated in Allegheny

County, Pa., D. C., Pa. 1960, 25 F. R. D. 88. See also Stein-

gut v. National City Bank of New York, D. C., N. Y., 1941,

36 F. Supp. 486.

Appellant’s Point No. 6

The Court denied this appellant the right to file a coun

terclaim.

Barron and Holtzoff, Vol. 2, page 408, has this to say:

“ Some cases have held that an intervenor may not assert a

counterclaim, though it is not entirely clear whether they

have done so as a matter of law or discretion. The great

weight of authority is to the contrary, and permits coun

terclaims by an intervenor whether the intervention is as

of right or permissive, and whether the counterclaim is com

pulsory or permissive.”

Bender’s Federal Practice Manual, page 111, Rule 13,

counterclaims and crossclaims, has this to say: “ Compulsory

Counterclaims: A pleading shall state as a counterclaim any

claim which at the time of serving the pleading the pleader

has against any opposing party.

Lee, Appellant, v. Brown et al, Appellees 13

(B) Permissive counterclaim: A pleading may state as

a counterclaim against an opposing party any claim not

arising out of the transaction or occurrence that is the sub

ject matter of the opposing party’s claim.”

Moore’s Federal Practice, Vol. 1, Buie 13, states:

“ The practice of free counterclaim sanctioned by sub

division (C) is highly desirable. It expressly declares that

there are to be no restrictions upon the type of counter

claim. Thus in a suit for specific performance the defendant

must set up any claim which he has that arises out of the

transaction or occurrence which is the basis of plaintiff’s

claim, pursuant to subdivision ( a ) ; and may set up any

independent claim that he has, such a claim for personal

injuries, slander, accounting, patent infringement, etc. Such

claims can be as easily pleaded in an answer by way of coun

terclaim as in a complaint by way of original action. The

matter of such counterclaim do not present a pleading prob

lem, but rather a trial problem, and the court is given ample

authority in subdivision (1) to handle it accordingly.”

Appellant’s Point No. 7

The appellees were in court on the grounds that they

were discriminated against and segregated by the Forestry

Commission because of their race. In its order of July 10th,

1963, the court agreed with this contention, yet the same

court denied this appellant the same rights that it exended

to the appellees. They were extended the due process and

equal protection provisions of the 5th and 14th Amendments

to the Constitution; yet, the protection of these provisions

were denied his appellant. The court even provided him

with a segregated afternoon session. He was denied his

right to participate in the main action. See transcript of

hearing, April 18, 1963.

A requirement of the Fourteenth Amendment is for a

fair trial and the due process clause prohibits procedure at

trials which is offensive to common and fundamental ideas

of fairness and right. The court has a responsibility to re

spect and protect persons from violation of federal consti

tutional rights and the violations of rules which guide and

control its conduct and the trial of issues before it.

CONCLUSION

The appellant has been denied his day in court because

counsel for the plaintiffs and the original defendants, failed

to send him copies of all pleadings filed in this cause which

prevented him from being able to offer a defense. The court

erred in not correcting this defect.

Appellant, on the basis of the Federal Rules of Civil

Procedure, which are as binding as an act of Congress, and

supported by the foregoing authorities, submits that the

judgment of the trial court should be reversed with in

structions to grant him a hearing, and with further instruc

tions to permit him to file his counterclaim.

Respectfully submitted,

DAVIS LEE,

Appellant and Counsel.

107 Butler Street,

Anderson, S. C.

14 Lee, A ppellant, v. Brown et al., Appellees

APPENDIX

The order of July 10, 1963, fails to mention the motion

filed by appellant May 23, 1963, for Declaratory Judgment.

_ The transcript of the hearing April 18, 1963, supports

position of appellant on conduct of hearing and how he was

excluded from participating.

It is hereby certified that copies of the brief have been

served upon counsel for the appellees th is ..............day of

November, A. D., 1963.

DAVIS LEE,

Appellant and Counsel.

( 1 5 )