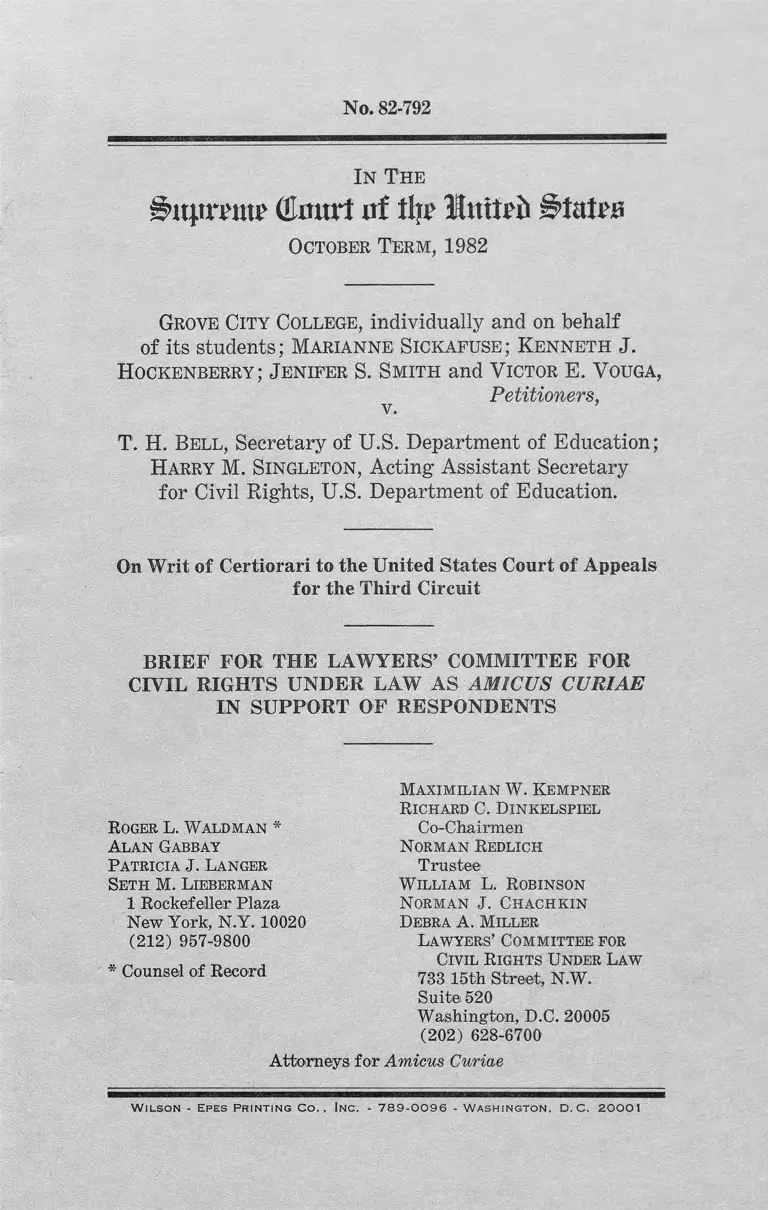

Grove City College v. Bell Brief Amicus Curiae in Support of Respondents

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1982

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Grove City College v. Bell Brief Amicus Curiae in Support of Respondents, 1982. 9340d7e3-b49a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/742a53cb-1d84-455b-9a38-d05f03b567a1/grove-city-college-v-bell-brief-amicus-curiae-in-support-of-respondents. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

No. 82-792

I n T h e

&it|imn£ ( to r t uf tfp? Ituteii l^tatea

October Term, 1982

Grove City College, individually and on behalf

of its students; Marianne Sickafuse; Kenneth J.

H ockenberry; J enifer S. Smith and V ictor E. Vouga,

Petitioners,v. ’

T. H. Bell, Secretary of U.S. Department of Education;

Harry M. Singleton, Acting Assistant Secretary

for Civil Rights, U.S. Department of Education.

On Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals

for the Third Circuit

BRIEF FOR THE LAWYERS’ COMMITTEE FOR

CIVIL RIGHTS UNDER LAW AS AMICUS CURIAE

IN SUPPORT OF RESPONDENTS

Maximilian W. Kempner

Richard C. Dinkelspiel

Co-Chairmen

Norman Redlich

Trustee

William L. Robinson

Norman J. Chachkin

Debra A. Miller

Lawyers’ Committee for

Civil Rights Under Law

733 15th Street, N.W.

Suite 520

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 628-6700

Attorneys for Amicus Curiae

Roger L. Waldman *

Alan Gabbay

Patricia J. Langer

Seth M. Lieberman

1 Rockefeller Plaza

New York, N.Y. 10020

(212) 957-9800

* Counsel of Record

W i l s o n - Ep e s P r i n t i n g C o . , In c . - 7 8 9 - 0 0 9 6 - W a s h i n g t o n , D . C . 2 0 0 0 1

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

INTEREST OF AMICUS CURIAE ............................ 1

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT ....................................... 3

ARGUMENT:

I. Grove City College Is A Recipient Of Federal

Financial Assistance For Purposes Of Title IX

Because Its Students Receive Federal Educa

tional Grants Based Upon Their Matriculation

At The School ....................................................... 4

A. The language of Title IX does not limit its

coverage to agencies or institutions receiving

direct cash payments from the federal gov

ernment; and the language and structure of

the BEOG program compel the conclusion

that grants to Grove City College students

are a form of “Federal financial assistance”

to the institution ............................................. 4

B. This construction of the statutory language

accords with its consistent interpretation by

the Department of Health, Education & Wel

fare and the Department of Education....... 11

C. The legislative history of Title IX and that

of Title VI supports the conclusion that Title

IX applies to Grove City College because its

students were awarded BEOGs..................... 13

1. The Legislative History of Title IX......... 13

2. The Legislative History of Title VI......... 16

D. The post-enactment history of Title IX dem

onstrates the Congressional intent to apply

Title IX to institutions assisted through di

rect student g ran ts ......................................... 19

II. As A Recipient Of Federal Financial Assistance

Through The BEOG Program, Grove City Col

lege May Properly Be Required To Execute An

Assurance Of Compliance With Title IX ........... 22

ii

TABLE OF CONTENTS—Continued

Page

A. The Title IX assurance and applicable regu

lations are “program-specific” as required

by North Haven............................... -........ —- 22

B. Because BEOG grants provide assistance to

the entire program of Grove City College,

that entire program of the institution is

covered by Title IX — .....................- ..... -..... 24

CONCLUSION ...... .......................................................... 30

Ill

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases: Page

Board of Public Instruction v. Finch, 414 F.2d

1068 (5th Cir. 1969) ................... ......... 6n, 23, 25n, 26n

Bob Jones Univ. v. Johnson, 396 F. Supp. 597

(D.S.C. 1974), aff’d mem., 529 F.2d 514 (4th

Cir. 1975) _______ ________ ______ __ ____ 9, 13n, 28n

Bob Jones Univ. v. United States, 51 U.S.L.W.

4593 (U.S. May 24, 1983) .............. 19

Bossier Parish School Bd. v. Lemon, 370 F.2d 847

(5th Cir.), cert, denied, 388 U.S. 911 (1967).... 28n

Cannon v. University of Chicago, 441 U.S. 677

(1979) _____ ____ _______ __________ ____ _ 2n, 15

Committee for Public Educ. v. Nyquist, 413 U.S.

756 (1973) ..... 10-11

Grove City College v. Bell, 687 F.2d 684 (3d Cir.

1982) .................................. ............ ...... ............. lln , 24n

Grove City College v. Harris, 500 F. Supp. 253

(W.D. Pa. 1980) .................. ............... ................. 5n, 8n

Guardians Ass’n v. Civil Service Comm’n, 51

U.S.L.W. 5105 (U.S. July 1, 1983) ........... _.lln, 12,19

Haffer v. Temple Univ., 524 F. Supp. 531 (E.D.

Pa.), aff’d, 688 F,2d 14 (3d Cir. 1982) ............. 27n

INS v. Chadha, 51 U.S.L.W. 4907 (U.S. June 23,

1983) ____ ______ ________ _________ ____ _ 19n

Iron Arrow Honor Soc. v. Heckler, 702 F.2d 549

(5th Cir. 1983) ______ ____ ____ ______ ____ 25n

Lau v. Nichols, 414 U.S. 563 (1974) ..................... 6n

Mueller v. Allen, 51 U.S.L.W. 5050 (U.S. June 29,

1983) ........... ............... ....... ................................... l ln

North Haven Bd. of Educ. v. Bell, 456 U.S. 512

(1982) ________ __ ________ ______________ passim

Norwood v. Harrison, 413 U.S. 455 (1973)__ __ 10

Statutes:

20 U.S.C. §■§ 401 et seq. .......... .... ............. ....... ..... . 17

20 U.S.C. § 427 ........... ...... ............. .......................... 26n

20 U.S.C. §§ 461-65 ....................... ........... .... ........ . 17n

20 U.S.C. § 1070(a)........... .................. ..... ......... ..... 7

20 U.S.C. § 1070a .... ....... .... ...... .............. .......... .... 5n

20 U.S.C. § 1070a(a) (1) (A) ................................... 7

IV

20 U.S.C. § 1070a(a) (1) (B) ............. ........... ....... 7n

20 U.S,C. § 1070a(a) (2) ............................. ............ 7-8

20 U.S.C. § 1070e ......... .............................................5n, 28n

20 U.S.C. § 1091 (a) (5) ______ _______________ 5n, 8

20 U.S.C. § 1092 __ _____ __ ______ _____ ___ _ 9n

20 U.S.C. § 1094(a) ....................................... ........ . 9n

20 U.S.C. §§ 3801 et seq. ____ ______ ______ ____ 6n

General Education Provisions Act, § 431(d)(1),

20 U.S.C. § 1231(d) (1) ............ ............... .......... 19

National Defense Education Act, §§ 201, 204-06,

reprinted in 1958 U.S. Code Cong. & Ad. News

1898-1902 ___________ _______ ___ _______ lln-12n

Title VI, 1964 Civil Rights A c t..... ................. ....... passim

Title IX, Education Amendments of 1972, 20

U.S.C. § 1681 et seq............... .......... ............ ....... passim

20 U.S.C.A. §§ 241a-m (Supp. 1969) .................. 6n

42 U.S.C. § 242g (1970) (repealed by Pub. L. No.

94-484, § 503(b) (1976) ___ ____ _______ ___ 17n

Pub. L. No. 92-318, § 139C, reprinted in 1972 U.S.

Code Cong. & Ad. News 335........ ....... .............. 8n

Pub. L. No. 93-568, 88 Stat. 2138 (1974) ............. 19n

Pub. L. No. 94-482, § 412, 90 Stat. 2234 (1976).... 19n

Regulations:

84 C.F.R. § 100.13(h) (1982) ___________ _____ 13n

34 C.F.R. at 312-13 (1982) ....................................... 12n

34 C.F.R. § 106.1 (1982) ......................... ................. 23, 24

34 C.F.R. § 106.2(g) (1) (ii) (1982) ..................... 12n

34 C.F.R. § 106.2(h) (1982) ................. 13n

34 C.F.R. § 106.4 (1982) __________ 22n

34 C.F.R. § 106.4(a) (1982) .......... 23

34 C.F.R. § 668.11 (1982) ................ 9n

34 C.F.R. § 690.94 (1982) _______ 9n

34 C.F.R. § 690.94(a) (3) (1982) ......... 7

34 C.F.R. § 690.95 (1982) ........ 9n

34 C.F.R. § 690.96 (1982) ..................... 9n

45 C.F.R. at 93-94 (1967) ....... ..................... ........... l ln

29 Fed. Reg. 16298 (Dec. 4, 1964) ...... ................ ..lln , 13n

29 Fed. Reg. 16304 (Dec. 4, 1964) ........................... l ln

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES—Continued

Page

V

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES—Continued

Page

29 Fed. Reg. 16988 (Dec. 11, 1964) ___ __ ______ _ 13n

40 Fed. Reg. 24128, 24137 (June 4,1975) ........... _12n, 13n

43 Fed. Reg. 20922, 20927-28 (May 15, 1978) ____ 9n

44 Fed. Reg. 5258 (Jan. 25, 1979) ____ ____ _____ 9n

Legislative Materials:

H.R. Rep. No. 2157, 85th Cong., 2d Sess. (1958),

reprinted in 1958 U.S. Code Cong. & Ad. News

4731 .......................... 12n

H.R. Rep. No. 914, 88th Cong., 1st Sess. (1963),

reprinted in 1964 U.S. Code Cong. & Ad. News

2391 .................. 17

H.R. Rep. No. 92-554, 92d Cong., 1st Sess. (1971),

reprinted in 1972 U.S. Code Cong. & Ad. News

2462 ...................... 14-15

Civil Rights Hearings Before Subcommittee No. 5

of the House Committee on the Judiciary, 88th

Cong., 1st Sess. (1963) ___ ___ __ _____ _____ 17

Sex Discrimination Regulations : Hearings Before

the Subcomm. on Postsecondary Education of

the House Comm, on Education & Labor, 94th

Cong., 1st Sess. (1975) ....... ...... ......... .13n, 20, 28n-29n

110 Cong. Ree. (1964) ........................... .............. 6n, 16-17

117 Cong. Rec. (1971) ............. ......... ....... 13,15n, 27n-28n

118 Cong. Rec. (1972) ---------------------- ----- 13n, 14, 16n

120 Cong. Rec. (1974) ........... .......... ......... ............ 28n

121 Cong. Rec. (1975) __ ______ ______ ______ 28n

122 Cong. Rec. (1976) .... ....... ....... ..... ........... ....... 21, 28n

S. 659, 92d Cong., 1st Sess. (1971) ....... ......... ..... 13, 14

S. 2146, 94th Cong., 1st Sess., 12:1 Cong. Rec.

23847 (1975) .... ................ ........ ........................... 20

S. Con. Res. 46, 94th Cong., 1st Sess., 121 Cong.

Rec. 17300 (1975) ........ ....... .................. ....... . 20

1963 U.S. Code Cong. & Ad. News 1527 _______ 6n

In The

(tort uf % Imtefr

October Term, 1982

No. 82-792

Grove City College, individually and on behalf

of its students; Marianne Sickafuse; Kenneth J.

Hockenberry; J enifer S. Smith and Victor E. Vouga,

Petitioners, v. ’

T. H. Bell, Secretary of U.S. Department of Education;

Harry M. Singleton, Acting Assistant Secretary

for Civil Rights, U.S. Department of Education.

On Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals

for the Third Circuit

BRIEF FOR THE LAWYERS’ COMMITTEE FOR

CIVIL RIGHTS UNDER LAW AS AMICUS CURIAE

IN SUPPORT OF RESPONDENTS

INTEREST OF AMICUS CURIAE 1

The Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law

was organized in 1963 at the request of the President of

the United States to involve private attorneys in the

national effort to assure civil rights for all Americans.

The Committee has, over the past 20 years, enlisted the

services of over a thousand members of the private bar

in addressing the legal problems of minorities and the

poor. The Committee’s membership today includes past

Presidents of the American Bar Association, a number of

law school deans, and many of the nation’s leading

lawyers.

1 Letters from counsel for the parties consenting to the submis

sion of this brief have been filed with the Clerk.

2

The Lawyers’ Committee has had a longstanding inter

est in eliminating sex discrimination in education and

has consistently sought vigorous enforcement of Title IX

of the Education Amendments of 1972.2 In 1975, the

Committee established a Federal Education Project,

which has worked to eliminate sex bias and stereotyping

in the vocational education programs which are offered

by most of the nation’s school districts. Research and ob

servation by the Project indicate that there has been

progress, over the last decade, in opening up opportu

nities for female students to learn the skills which can

lead to highly paid jobs traditionally viewed as “male

only” and from which women were often barred. The

antidiscrimination requirements of Title IX-—which have

been interpreted to apply to all of a recipient school

system’s vocational curricula, even though federal Voca

tional Education Act funds constitute less than 20% of

total program expenditures at the secondary school

level—have contributed significantly to this progress.

Thus, the narrow approach to Title IX coverage pro

posed by the petitioners could jeopardize the achievement

of fully equal opportunity for women in education and

employment. The ruling sought by petitioners also would

have grave implications for the scope of the antidiscrimi

nation requirement in Title VI of the 1964 Civil Rights

Act.3 This possibility equally prompts the Committee’s

interest in the present case, for Title VI has been a criti

2 For example, the Committee filed an amicus curiae brie-f in

Cannon v. University of Chicago, 441 U.S. 677 (1979) supporting

the right of the petitioner in that case to bring a private suit to

enforce Title IX.

3 This Court has recognized in several recent rulings that Title IX

was patterned after Title VI, a broad prohibition of racial discrimi

nation in federally assisted programs; similar language in the two

statutes is construed in a similar fashion absent contrary indica

tions in the law or legislative history. North Haven Bd. of Educ.

v. Bell, 456 U.S. 512, 529 (1982); Cannon v. University of Chicago,

441 U.S. at 694-98.

3

cal element of the civil rights gains made during the past

two decades.

Over the course of its work in the field of education,

the Lawyers’ Committee has come to realize that dis

crimination on the basis of race or sex is a serious

impediment to equal opportunity for students, faculty

and other staff members, whether or not that discrimina

tion manifests itself within a particular constituent part

of an educational institution that is formally designated

as the “recipient” of an “earmarked” federal grant or

contract. Titles VI and IX were enacted, in part, to

insure that federal financial assistance made available by

the Congress for educational programs does not subsidize

discriminatory activities. Petitioners’ interpretation of

the scope of Title IX, which would permit an educational

institution to receive funds made available by the federal

government and to use those funds for its basic operating

expenses, without undertaking any concomitant obligation

to eliminate discriminatory practices, would thus be con

trary to the purposes of Title IX.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

I

The Third Circuit correctly held that Grove City Col

lege is a recipient of “Federal financial assistance”

within the meaning of Title IX. The language of the

statute, its administrative construction, and both its leg

islative and post-enactment history support the ruling

below. An educational institution is subject to Title IX

because it is a recipient of “Federal financial assistance”

when it participates in a program under which the stu

dents whom it certifies are enrolled at its facilities re

ceive federal funds, in amounts based in part upon the

institution’s tuition and related charges, and the students

are required to use those funds “solely for expenses

related to attendance or continued attendance at such

institution.”

4

II

The court below also correctly upheld the Department

of Education's regulation requiring that Grove City Col

lege, like other recipients of Federal financial assistance,

execute a written Assurance of Compliance with appli

cable substantive Title IX regulations of the Department,

as a precondition to the award of BEOG grants to Grove

City students. Both the Assurance and the Title IX regu

lations explicitly refer to and incorporate the statutory

requirement of “program specificity,” and both must

therefore be sustained on the basis of this Court’s rea

soning in North Haven Board of Education v. Bell, 456

U.S. 512 (1982). Furthermore, because BEOG student

grants are intended to, and do support the entire educa

tional program offered by Grove City College, on the

facts of this case the entire institution is subject to Title

IX’s prohibition against discriminatory treatment be

cause of sex.

ARGUMENT

I

GROVE CITY COLLEGE IS A RECIPIENT OF FED

ERAL FINANCIAL ASSISTANCE FOR PURPOSES

OF TITLE IX BECAUSE ITS' STUDENTS RECEIVE

FEDERAL EDUCATIONAL GRANTS BASED UPON

THEIR MATRICULATION AT THE SCHOOL

A. The Language of Title IX Does Not Limit its Cover

age to Agencies or Institutions Receiving Direct Cash

Payments from the Federal Government; and the

Language and Structure of the BEOG Program Com

pel the Conclusion that Grants to Grove City College

Students are a Form of “Federal Financial Assist

ance” to the Institution

Petitioners contend that Title IX is wholly inapplicable

to Grove City College because the school does not “re-

ceiv[e] Federal financial assistance” within the meaning

of § 901(a) of Title IX of the Education Amendments of

5

1972, 20 U.S.C. § 1681 et seq. (“Title IX” ).4 According

to petitioners, this conclusion follows from the fact that

the College does not request direct cash payment from

the federal government5 of the student assistance funds

that make it possible for the individual petitioners to at

tend the institution.'6 However, this construction is incon

sistent with the plain language of the statute.7

The term “Federal financial assistance,” which first

appeared in Title VI of the 1964 Civil Rights Act,8 is

4 Grove City College has not itself sought federal grant or con

tract funds. Many students at Grove City, however, do. receive

funds from the federal government under the Basic Educational

Opportunity Grant (“BEOG”) program, 20 U.S.C. § 1070a, which

they must use to> pay for tuition, room and board, and other

expenses related to' their attendance at the College. See 20 U.S.C.

§ 1091(a)(5).

*See Pet. Br. a t 14-17. Apparently the College foregoes the

additional funds to which it would he entitled under federal law

based upon the receipt of BEOG grants by its students, see 20

U.S.C. § 1070e. (Pet. Br. at 26 n.24.)

6 See Grove City College v. Harris, 500 F. Sup-p. 253, 257 (W.D.

Pa, 1980) (Amended Findings of Fact made by district court in

this ease).

7 “Our starting point in determining the scope of Title IX is,

of course, the statutory language.” North Haven Bd. of Educ. v.

Bell, 456 U.S. 512, 520 (1982).

8 Petitioners suggest that the language' enacted as Title VI repre

sents a narrowing of a broader, earlier legislative proposal; and

that Congress, intended thereby to exclude from Title VI coverage

all recipients of what petitioners term “indirect” assistance. (Pet.

Br. a t 29-30.) This overlooks the fact that in § 602 of Title VI,

Congress specifically excluded two forms of financial assistance:

contracts of insurance or guaranty. The addition of specific exclu

sions from the generic term “Federal financial assistance” in the

final version of the statute eliminates the basis for any inference

that other kinds of “Federal financial assistance,” whether “direct”

or “indirect,” would not trigger coverage. See North Haven, 456

U.S. at 521-22 (“the absence of a specific exclusion . . . among the

list of exceptions, tends to support the: Court of Appeals’ conclusion

that Title IX’s. broad protection . . . does extend . . .”).

6

deliberately broad and covers the multitude of different

arrangements by which the federal government may pro

vide aid or support to an institution or agency.® Nothing

in the language of the statute supports petitioners’ view

that the particular institutional entity, through which

the “education program or activity receiving Federal

financial assistance” is administered, must itself be the

applicant for assistance or must receive a Treasury De

partment draft of funds in order to trigger Title IX cov

erage.9 10 It is sufficient that the “education program or

9 This is hardly surprising, in light of the Congressional purpose

to insure “that public funds, to which all taxpayers of all races

contribute, not be spent in any fashion ivhich encourages, subsidizes,

or results in racial discrimination.” 110 Cong. Rec. 6543 (1964)

(Sen. Humphrey, quoting from President Kennedy’s message to

Congress of June 19, 1963, reprinted in 1963 U.S. Code Cong. & Ad.

News 1527, 1534) (emphasis added).

110 Petitioners’ interpretation of the statute would by its logic

exclude from Title IX coverage a local school district which partici

pated only in federal programs administered through the States.

Petitioners disavow this result (see Pet. Br. a t 17 n.17) but they

do not explain how their position is consistent with their argument

that Grove; City College is not subject to Title IX because the

Treasury Department sends its BEOG checks to individual students

rather than to the institution.

Petitioners’ concession is clearly correct. It has never been

doubted, for example, that Title VI and Title IX apply to local

school districts which obtain federal funds from their state educa

tional agencies under the government’s largest program of aid to

elementary and secondary education, Chapter 1 of the Education

Consolidation and Improvement Act of 1981, 20 U.S.C. §§ 3801

et seq., formerly Title I of the Elementary and Secondary Education

Act of 1965. See, e.g., Lau v. Nichols, 414 U.S. 563 (1974) ; Board

of Public Instruction v. Finch, 414 F.2d 1968, 1071 (5th Cir. 1969)

(receipt of Title I [then known as Title II] funds under 20 U.S.C.A.

§§ 241a-m (Supp. 1969)).

Petitioners’ attempted distinction of stater-administered pro

grams rests upon their contention that BEOGs do< not amount to

“Federal financial assistance” to an institution of higher education

if the grants are paid to' its students under the Alternate Disburse

ment System (see Pet. Br. a t 17 n.17). This argument in turn

incorporates a basic misreading of the grant statute1. See text at

pp. 7-8 infra.

activity” administered by the institution receive the as

sistance in some fashion.11

The language and structure of the BEOG statute con

firm our view that the Department of Education’s award

of grants to Grove City students, upon certification by

the College of their enrollment, makes the school subject

to the coverage of Title IX.

The purpose of the federal higher education assistance

programs, including BEOGs, is “to assist in making avail

able the benefits, of postsecondary education to eligible stu

dents . . . in institutions of higher education . . . 20

U.S.C. § 1070(a).12 * * * * * * * 20 Since there must be both a student

and an educational institution in order for postsecondary

education to be “ma.[de] available,” and since grants are

awarded to students based upon i(a) certification of a

student’s matriculation at such an institution, 20 U.S.C.

§ 1070a(a) (1) (A) ; 34 C.F.R. § 690.94(a) (3) (1982)

and (b) determination of financial need based upon the

actual costs of attendance at the certifying institution,

7

11 This Court recently declared in North Haven, 456 U.S. at 521,

that “if we are to. give [Title IX] the scope that its origins dictate,

we must accord it a sweep as broad as its language.”

12 More specifically, BEOGs are designed to:

(i) . . . meet in academic year 1985-1986, 70 per centum of a

student’s cost of attendance not in excess of $3,700; and (ii) in

combination with reasonable parental or independent student

contribution and supplemented by the programs authorized

under subparts 2 and 3 of this part, will meet 75 per centum

of a student’s cost of attendance, unless the institution deter

mines that a greater amount of assistance 'would better serve

the purposes of section [1070].

20 U.S.C. :§ 1070a(a) (1) (B) (emphasis added). This specific

elaboration of purpose for BEOGs was added to. the Higher Educa

tion Act in 1980. Prior to that time, the statute contained only the

general “purpose” language of § 1070(a) quoted in text, but the

amount of BEOG awards was still determined with reference to. an

institution’s tuition and other charges. Petitioners’ claims concern

ing the scope of Title IX coverage are the same, as we understand

them, under either the pre- or post-1980 versions of the law.

8

20 U.S.C. § 1070a(a) (2), it is obvious that Congress in

tended the BEOGs program to make “Federal financial

assistance” available to institutions of higher education

selected by eligible students.

Petitioners’ assertions that the College does not receive

“Federal financial assistance” because Grove City stu

dents need not use their BEOG funds for the school’s

costs but “may” use the funds “for virtually any pur

pose” (Pet. Br. at 5 n.9) simply blinks legality, as well

as reality. The statute not only ties the amount of a

grant to the actual costs at the particular institution

which a student chooses to attend, but it also requires a

statement (which must be filed “with the institution of

higher education which the student intends to attend, or

is attending” 10 * * *) stating that the grant “will be used

solely for expenses related to attendance or continued at

tendance at such institution.” 20 U.S.C. § 1091(a) (5).14

Thus, BEOG awards flow through the student to the

higher educational institution.1'5

18 The' statement filed with the school provides assurance to' the

institution that a student or1 admittee will be able to' meet the costs

of his or her attendance during the school year to which the BEOG

is applicable.

14 The current statutory language was added in 1980, but the

requirement of filing a statement or affidavit to this effect was con

tained in the original BEOG legislation. See Pub. L. No. 92-318,

§ 139C, re-printed in 1972 U.S. Code Cong. & Ad. News 335.

In any event, on this record there is no issue. Individual petition

ers admitted, and the district court found, that without their BEOG

awards each would be unable to attend Grove City College. See 500

F. Supip. a t 257.

1(5 It is also' patently wrong to assert, as do petitioners, that there

is only an “attenuated nexus between [Education] Department-

administered funds and the College” (Pet. Br. a t 47) because under

the BEOG program Alternate Disbursement System, the “only role

which the College plays . . . is supplying requested information to

the scholarship or loan-granting organization . . . .” (Pet. Br. at

3-4.) Institutions whose students receive BEOG awards must not

only certify their attendance in good standing but must notify fed-

9

The interpretation here advanced was adopted in Bob

Jones University v. Johnson, 396 F. Supp. 597 (D.S.C.

1974), aff’d mem,, 529 F.2d 514 (4th Cir. 1975),* 16 17 hold

ing that school was a recipient of “Federal financial as

sistance” within the meaning of Title VI under a Vet

erans Administration program strikingly similar to the

BEOG program.1'7 While this Court has never decided the

era! officials of a student’s change in enrollment status, as well as

maintain certain records and make them available to f ederal officials

upon requetst for audit purposes. See 43 Fed. Reg. 20922, 20927-28

(May 15, 1978); 44 Fed. Reg. 5258 (Jan. 25, 1979); 34 C.F.R.

§§ 690.94, 690.95, 690.96 (1982). In addition, since 1980 these in

stitutions have had mandatory obligations to provide information

to all prospective and admitted students about all financial assist

ance programs available, 20 U.S.C. § 1092, and to enter into a. specific

“program participation agreement” with the Secretary of Educa

tion, 20 U.S.C. § 1094(a) ; 34 C.F.R. § 668.11 (1982).

16 Petitioners’ argument that Bob Jones is inapposite; because

that case involved race; discrimination in the admissions, process and

because Title. IX lacks, the constitutional scope of Title VI (Pet. Br.

a t 35-36) is without merit. The Bob Jones decision is based on a

common-sense interpretation, of the language of Title VI and analy

sis of how the government aid to students in that case assisted the

university. The; court cited the constitutional scope of Title; VI

merely as an additional, but by no means the central, argument for

its conclusion. The fact that the case involved discrimination in the

admissions process was not the determinative factor in the court’s

conclusion that the school received Federal financial assistance.

17 As the; court, there recognized,

The method of payment does not determine the; result; the

literal language; of Section 601 requires only federal assistance

—not payment—to a program or activity for Title VI to

a ttach . . . .

[A]ll that is necessary for Title; VI purposes is. a showing that

the infusion of federal money through payments to veterans

assists the educational program of the school.

396 F. Supp. a t 602, 603 n.22. Petitioners criticize the ruling below

and, implicitly, the Bob Jones court (upon whose decision the

Third Circuit relied in, part) on the ground that it equated “receiv

ing” federal financial assistance with “benefiting” from such assist

ance. (Pet. Br. at 15-17.) However, a, careful reading of both

10

precise issue, its rulings in other areas demonstrate that

the formal mechanism by which assistance is made avail

able is not legally controlling. For example, in Norwood

v. Harrison, 413 U.S. 455 (1973), the Court concluded

that a state program for the loan of textbooks to school-

children cannot constitutionally provide textbooks to stu

dents attending racially discriminatory private schools

since

[f]ree textbooks, like tuition grants directed to pri

vate school students, are a form of financial assist

ance inuring to the benefit of the private schools

themselves. An inescapable educational cost for stu

dents in both public and private schools is the ex

pense of providing all necessary learning materials.

When, as here, that necessary expense is borne by

the state, the economic consequence is to give aid to

the enterprise; if the school engages in discrimina

tory practices the State by tangible aid in the form

of textbooks thereby gives support to such discrimi

nation.

Id, at 463-65 (citation and footnote omitted). Similarly,

in Committee for Public Education v. Nyquist, 413 U.S.

756 (1973), a: New York law providing tuition reimburse

ments to parents of children attending nonpublic schools

was overturned on the ground that the statute had the

effect of subsidizing and advancing the religious mission

of sectarian schools and thus violated the Establishment

Clause. The Court dismissed the argument made by pro

ponents of the statute that since the aid was granted to

parents and not to the schools, the Constitution was not

violated: “ [T]he effect of the aid is unmistakably to pro

opinions indicates that; both courts considered whether the schools

“benefited” from the award of educational grants to their students

as a means of determining whether the schools were “assisted,” not

whether they were “recipients.” Here, the BEOG awards made it

possible for the individual petitioners to attend Grove City College

(see note 14 supra) and assisted the school in receiving payment of

tuition and related charges for these students.

vide desired financial support for nonpublic, sectarian in

stitutions.” Id. at 783.!ls

B. This Construction of the Statutory Language Accords

with its Consistent Interpretation by the Department

of Health, Education & Welfare and the Department

of Education

Since passage of Title VI and Title IX, respectively,

the federal agencies responsible for their implementation

have consistently interpreted these provisions to apply to

institutions of higher education whose students receive

scholarship or loan assistance to enable them to attend the

schools. Appendix A to the initial Title VI regulations,10

which identified programs to which the regulations were

applicable, included several making assistance available

through payments to students,2,0 and the current listing

11

is While Nyquist was distinguished in Mueller v. Allen, 51

U.S.L.W. 5050 (U.S, June 29, 1983) (upholding, under the Estab

lishment Clause, a state law provision making tax deductions for

certain educational expenditures available to parents of both public

and private: school students), the Court recognized that the tax

deductions constituted governmental assistance to the schools, since

they were available only for specified educational expenses such as

tuition. See id. a t 5053. The Minnesota scheme survived an Estab

lishment Clause challenge because its “primary eifeet” was not to

aid parochial schools—not because there was no aid a t all to

parochial schools. See id. a t 5053-54.

i» “The Justice Department, which had helped draft the language

of Title VI, participated heavily in preparing the regulations.”

Guardians Ass’n v. Civil Service Comm’n, 51 U.S.L.W. 5105, 5115

(U.S. July 1, 1983) (Marshall, J., dissenting) (footnotes omitted).

s» See 29 Fed. Eeg. 16298, 16304 (December 4, 1964) ; 45 C.F.R.

at 93-94 (1967) ; see also Grove City College v. Bell, 687 F.2d 684,

691-92 n.14 (3d Cir. 1982). For example-, under Title II of the

NDEA the federal government made capital contributions to- sepa

rate student loan funds to- be established and administered by insti

tutions of higher education—not to- the schools themselves. The

loan funds were to be used o-nly for specified purposes and their

assets co-uld not be transferred to the institutions except under

circumstances explicitly detailed in the statute. See §§ 201, 204-06,

12

of programs covered by Title VI includes both BEOGs

and NDEA loans,* 21 22 Similarly, the Title IX regulations

initially issued by the Department of Health, Education

& Welfare (and all succeeding versions of those regula

tions promulgated by HEW or the Department of Edu

cation) explicitly define “Federal financial assistance” to

include:

Scholarships, loans, grants, wages or other funds

extended to any entity for payment to or on behalf

of students admitted to that entity, or extended

directly to such students for payment to that entity.122

This contemporaneous and consistent interpretation of

the statutory provisions'23 is entitled to great deference,

especially on the issue of the administrative agency’s

scope of authority. See Guardians Association v. Civil

Service Commission, 51 U.S.L.W. 5105, 5108 text at

nn.13, 14 (U.S. July 1, 1983) (opinion of White, J.), and

case cited; id. at 5115-16 (Marshall, J., dissenting), and

cases cited; id. at 5122 (Stevens, J., joined by Brennan

and Blackmun, JJ., dissenting), and cases cited.24

NDEA, reprinted in 1958 U.S. Cod© Cong. & Ad. News 1898-1902.

Nevertheless, the Congress recognized that the loan funds would

“materially assist institutions of higher education to retain their

more competent students who need financial assistance in order to

continue their studies.” H.R. Rep. No, 2157, 85th Cong., 2d Sees.

(1958), reprinted in 1958 U.S. Code Cong. & Ad. News 4731, 4738.

21 34 C.F.R. a t 312-13 (1982).

22 40 Fed. Reg. 24128, 24137 (,§ 86.2(g) (1) ( ii) ) (June 4, 1975);

34 C.F.R. § 106.2(g) (1) (ii) (1982).

23 Unlike in North Haven, see 456 U.S. a t 522 n.12, 538 n.29, the

administrative agencies have not changed their position with re

spect to the portions of the regulations relevant to this discussion.

24 Petitioners focus on the “or benefits from” language contained

in the Title IX regulations’ definition of “recipient.” (Pet, Br. at

16-17.) The critical portion of the regulation, however, is its char

acterization as a “recipient” of an entity to which assistance is

extended “through another recipient.” That portion of the regu

lation is identical to the original Title VI regulation. Compare

13

C. The Legislative History of Title IX and that of Title

VI Supports the Conclusion that Title IX Applies to

Grove City College Because Its Students Were

Awarded BEOGs

The legislative history of Title IX and of the statute

on which it was modeled, Title VI, provides further sup

port for the conclusion that the BEOG grants awarded to

Grove City students are sufficient to bring that institu

tion within the purview of Title IX.

1. The Legislative History of Title IX

Senator Bayh introduced the original version of Title

IX as an amendment to S. 659, 92d Cong., 1st Sess.

(1971), the Education Amendments of 1971. Senator Mc

Govern urged passage of the Bayh amendment “. .. . to

assure that no funds from S. 659 . . . be extended to any

institution that practices biased admission or educational

policies.” 117 Cong. Rec. 30158-59 (1971).35 Senator Mc- 40

40 Fed. Reg. 24128, 24137 (§ 86.2(h)) (June 4, 1975) with 29 Fed.

Reg. 16298 (December 4, 1964), as corrected by 29 Fed. Reg. 16988

(December 11, 1964) (§ 80.13(h)); compare 34 C.F.R. § 106.2(h)

(1982) with 34 C.F.R. § 100.13(h) (1982). Moreover, when the

Title IX regulations were promulgated in final form the Boh Jones

University v. Johnson decision, which articulated a “benefit from”

test to determine, whether a school was a recipient of “assistance”

under Title VI (see p. 9 & nn.16, 17 supra) had been issued. The

Department of Health, Education & Welfare relied upon this inter

pretation by the court when it added the “benefit from” language to

the definition of “recipient.” See Sex Discrimination Regulations:

Hearings Before the Suhcomm. on Postsecondary Education of the

House Comm, on Education and Labor, 94th Cong., 1st Sess. 481

(1975).

125 Contrary to what petitioners argue (see Pet. Br. a t 22-23),

many of the remarks of legislators regarding the 1971 amendment,

including those of Senator McGovern quoted above; are equally

applicable to the 1972 Bayh amendment, which became Title IX.

Senator Bayh said, in presenting his 1972 amendment: “Now I am

coming back with this comprehensive approach which incorporates

. . . the key provisions of my earlier amendment.” 118 Cong. Rec.

5808 (.1972). Although the wording of the 1972 amendment differs

in many respects from the wording of the 1971 proposed amend-

Govern’s remarks directly applied to the BEOG program,

which was part of S. 659.

Although the antidiscrimination provisions did not come

to a vote that year, in 1972 Senator Bayh reintroduced

them in a modified form and secured their passage. Prior

to their enactment, however, Senator Bentsen offered an

amendment seeking to exempt traditionally single-sex

public undergraduate institutions from Title IX coverage.

In describing the purpose of his amendment, Senator

Bentsen demonstrated his understanding that Title IX

applied when grants were made to students to support

their attendance at college. Referring to a particular

single-sex institution, he observed:

If Federal funds are cut off, it is the students who

will suffer. This university now receives over $250,-

000 in educational opportunity grants; it receives

$83,000 for college work-study programs.

118 Cong. Rec. 5814 (1972). See also H.R. Rep. No. 92-

554, 92d Cong., 1st Sess. (1971), reprinted in 1972 U.S.

Code Cong. & Ad. News 2462, 2584 (“Federal dollars

now constitute over 20 % of the total budget of our higher

ment, the concept a t issue, “recipient, of Federal financial assist

ance,” was part of both amendments. The differences between the

two versions which petitioners point out are not relevant to inter

preting the term “recipient.” For example, petitioners emphasize

that the 1971 amendment did not reach private undergraduate

schools, and based upon this fact, assert that comments during the

1971 floor debates concerned “public institutions which were un

questionably receiving substantial direct federal assistance and

were not intended to apply to private undergraduate institutions

like Grove City.” (Pet. Br. at 23.) But petitioners cite no floor

statements, or other authority to support either their characteriza

tion of Congressional intent or their surmise of Congressional

knowledge about funding patterns. In fact, when in 1972 Title IX

was enacted in a form applicable to private as well as public

institutions, it was accompanied by a Committee report and supple

mental views which recognized the major support provided to, all

higher education institutions by the federal government. See text

infra.

15

education system. Most of these dollars flow to institu

tions through research contracts, student assistance pro

grams, and categorical programs . . . .” ) (emphasis

added) (Supplemental Views).

Thus, during the Committee and floor consideration of

Title IX, Senators and Congressmen recognized that the

statute would apply to educational institutions receiving

federal assistance through BEOG grants to their students.

Petitioners have been unable to discover any clear indica

tions to the contrary in the legislative history, and obvi

ously if Congress had wished to limit the coverage of Ti

tle IX to educational institutions receiving cash payments

from the' federal government, it could have done so ex

plicitly. Moreover, the legislative history reflects the in

tent of Congress to enact a statute which would pre

vent . . the use of federal resources to support dis

criminatory practices,” Camion v. University of Chicago,

441 U.S. 677, 704 (1979).36

Petitioners cite an exchange between Senator Dominick

and Senator Bayh during the debates over the 1971

amendment which, they argue, “strongly suggests” that

the amendment was not intended to cover assistance re

ceived directly by students. (See Pet. Br. at 24-25.) Sen

ator Bayh’s statements during this exchange, which con

cerned the type of a recipient’s aid that could be cut off

under Title IX, are, at best ambiguous. Petitioners as

sume that Senator Bayh meant that his amendment would

not allow cutting off of student aid, but the more plausi

ble reading of his comments is that as a matter of law,

a® See 117 Cong. Ree. 39252 (“Millions of women pay taxes into

the Federal treasury and we collectively resent that these funds

should be used for the support of institutions to which we1 are

denied equal access’’) (remarks of Rep. Mink) ; id. a t 39253

(“Neither the President nor the Congress nor the conscience of

the nation can permit money which comes from all the people to

be used in a way which discriminates against some of the people”)

(remarks of Rep. Sullivan, quoting President Nixon).

16

the Secretary would have the power to cut off student aid

but as a matter of good judgment would most probably

not do so.®7 In order to support their interpretation of

the exchange, petitioners are forced to hypothesize that

“Senator Bayh later changed his mind” on this issue.

(Pet. Br. at 25 n.23.)

2. The Legislative History of Title VI

Since Title IX is closely and deliberately patterned

after Title VI,*8 the legislative history of Title VI pro

vides insight into how to interpret Title IX. This legisla

tive history is consistent with Title IX coverage of edu

cational institutions whose students receive BEOGs.

As previously noted, Senator Hubert Humphrey, a pri

mary sponsor of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, argued in

floor debate on the Act that “ [sjimple justice requires

that public funds, to which all taxpayers of all races con

tribute, not be spent in any fashion which encourages,

subsidizes, or results in racial discrimination,” 110 Cong. * 28

127 Petitioners advance an even lees supportable reading of Senator

Bayh’s 1975 colloquy with Representative Quie during hearings

on the Title IX regulations. (Pet. Br. a t 25.) Senator Bayh first

said he simply did not know the answer to Rep. Quie’s coverage

question, but “would have to look it up.” He then echoed his 1971

answer to Senator Dominick by stating that “generally” student

aid was not terminated as a penalty for uncorreeted discrimination.

Finally, Senator Bayh told Mr. Quie that he had not heard the

argument for coverage based on. student assistance to which Quie

referred. What these statements teach about Congressional intent

in 1972 is highly questionable.

28 Senator Bayh, the prime; sponsor of Title IX, described the

relation between, the two statutes as. follows :

Discrimination against the beneficiaries of federally assisted

programs and activities is already prohibited by Title VI of the

1964 Civil Rights Act, but unfortunately the prohibition, does

not apply to discrimination on the basis of sex. In order to

close this loophole, my amendment sets forth prohibition and

enforcement provisions which generally parallel the provisions

of Title VI.

118 Cong. Rec. 5807 (1972).

17

Rec. 6543 (1964) (emphasis added). The then Secretary

of HEW, Anthony Celebrezze, testified before the House

Judiciary Committee that Title VI would allow cut-off of

federal contributions to student loan funds under the Na

tional Defense Education Act, 20 U.S.C. § 401 et seq.

Civil Rights Hearings Before Subcommittee No. 5 of

the House Committee on the Judiciary, 88th Cong., 1st

Sess. 1541 (1963). Congressmen Poff and Cramer, ex

pressing their opposition to passage of the Act, drew up

a list of programs that would he covered by Title VI

which included programs involving grants or awards to

students. See H.R. Rep. No. 914, 88th Cong., 1st Sess.

(1963) (Separate Minority Views of Hon. Richard H,

Poff and Hon. William Cramer) reprinted in 1964 U.S.

Code Cong. & Ad. News 2391, 2471-73.-“’ Petitioners cite

no expressions of disagreement by legislators with these

descriptions of the scope of Title VI.

Instead, petitioners merely make generalized claims

that such indications of student assistance coverage in

the Title VI legislative history are inapplicable to Title

IX. As we describe in the margin, these claims are with

out merit.30 Thus, the legislative history of Title IX and

The list included 42 U.S.C. § 242g (1970) (repealed by Pub.

L. No. 94-484, § 503(b) (1976)) (grants to individuals or institu

tions for graduate training for physicians, engineers, nurses and

other professional personnel) and 20 U.S.C. §§ 461-65 (graduate

fellowships).

so First, petitioners argue that because Title IX is more limited

in scope than Title VI, “ [s]ome broad pronouncements in the Title

VI legislative history simply do. not apply to Title IX.” (Pet. Br. at

28.) Aside from failing to point out what these broad pronounce

ments are, petitioners ignore the fact that the broad goals under

lying Title IX—goals similar to tho'se of Title VI—also' sparked

similarly broad pronouncements. (See the remarks of Senator

McGovern, and Representatives Mink and Sullivan, supra p, 13 and

note 26.)

Second, petitioners claim that there is some significance to. the

fact that the BEOG program was not in existence at the time when

18

Title VI, interpreted in light of the clear remedial pur

pose of both statutes, supports a broad reading of Title

Title VI was enacted and that federal funds under the student

assistance programs then extant went first: to educational insti

tutions . . which had the discretion to choose the ultimate student

beneficiary.” (Pet. Br. a t 29.) We have previously observed both

that NDEA loan monies were placed in special funds and not in

institutional accounts, and also that when NDEA was enacted,

Congress recognized that the loans would assist institutions as well

as students (see note 20 supra). While the BEOG program does

have a different administrative structure from programs in effect

in 1964, it is nevertheless similar in the sense that institutions

have a role in selecting grant recipients because they make admit

tance decisions and are in possession of student financial informa

tion revealing whether or not an applicant will need financial aid

in order to meet the institution’s costs. There is no basis for peti

tioners’ assumption that Congress would have excluded BEOGs

from Title VI had the program existed in 1964—especially in

light of the defeat of post-1975 attempts to sot limit Title IX, see

pp. 20-21 infra.

Third, petitioners make much of differences between the original

and final versions of Title' VI. (See Pet. Br. a t 29-30.) We addressed

this point in note 8 supra.

Fourth, petitioners cite a number of instances when legislators

stated that Title VI would not cover direct payments to individuals.

(See Pet. Br. a t 31-33.) In context1, these remarks are best under

stood to relate to entirely different sorts of programs than BEOGs.

The instant case differs from a situation in which a college enrolls

students receiving food stamps, child welfare payments, or other

non-education benefits. See Brief of Amici Curiae, Mountain States

Legal Foundation and American Association of Presidents of Inde

pendent Colleges and Universities, a t 9-10. Participation in a

student aid program is contingent upon the student’s being in

attendance a t an educational institution. The other benefit programs

provide individual assistance regardless of whether the person goes

to school and thus are not intended to assist educational institutions.

Finally, petitioners argue that student assistance under the

BEOG program is virtually unrestricted and the nexus between

student receipt of the funds and assistance to the institution there

fore is attenuated. (See Pet. Br. a t 33.) We have noted previously

that the use of BEOG awards by students is far more narrowly

circumscribed than petitioners admit. See p. 8 supra. The nexus

between BEOG awards to> students and aid to institutions is strong,

direct, and clear.

19

IX. Applying Title IX to Grove City College is consist

ent with the Congressional purposes underlying Title IX.

D. The Post-enactment History of Title IX Demonstrates

the Congressional Intent to Apply Title IX to Institu

tions Assisted Through Direct Student Grants

In North Haven, this Court, in interpreting Title IX,

stressed the importance of post-enactment developments.

See 456 U.S. at 535. Accord, Bob Jones University v.

United States, 51 U.S.L.W. 4593, 4600-01 (U.S. May 24,

1983) ; Guardians Association v. Civil Service Commis

sion, 51 U.S.L.W. 5108 text at n.14 (opinion of White,

J.) ; id. at 5116 (Marshall, J., dissenting). An examina

tion of the post-enactment history of Title IX shows that

Congress knew that HEW interpreted Title IX to encom

pass educational institutions whose students received fed

eral BEOG grants, approved that interpretation, and al

lowed it to stand although it amended Title IX in other

respects on several occasions.®1

In 1975, HEW submitted its recently promulgated

Title IX regulations to Congress for review pursuant to

§ 431(d) (1) of the General Education Provisions Act, 20

U.S.C. § 1232(d)(l). (This statute provided Congress

with an opportunity to disapprove a regulation by con

current resolution 3:2 if it found that the regulation was

. . inconsistent with the Act from which it derives its

authority.” ) Included among the regulations were

HEW’s definitions of “Federal financial assistance” and

“recipient.” See p. 12 & n.24 supra. During hearings on

the regulations, HEW Secretary Weinberger brought the

si See Pub. L. No. 93-568, § 3, 88 Stat. 2138 (1974) ; Pub. L. No.

94-482, §412, 90 Stat. 2234 (1976).

® But see INS v. Chadha, 51 U.S.L.W. 4907 (U.S, June 23, 1983).

The constitutional infirmity of the legislative veto' provision, of

course does not affect the relevance of the 1975 review of the Title

IX regulations as an. indication, of Congressional intent or post

enactment ratification of the agency’s interpretation.

matter of coverage of student assistance directly to the

legislators’ attention:

Our view was that student assistance, assistance

that the Government furnishes, that goes directly or

indirectly to an institution is Government aid within

the meaning of Title IX. If it is not, there is an

easy remedy. Simply tell us it is not. We believe it

is and base our assumption on that.

As Mr. Rhinelander [HEW General Counsel] says

the court case [Bob Jones University v. Johnson]

confirms this belief.

Sex Discrimination Regulations: Hearings Before the

Subcomm. on Postsecondary Education of the House

Comm, on Education and Labor, 94th Cong., 1st Sess.

484 (1975). None of the concurrent resolutions to disap

prove the Title IX regulations which were introduced in

the House passed that body.

In the other chamber, Senator Helms attempted to per

suade his colleagues that the Department’s interpretation

was incorrect but he failed to do so. His proposed resolu

tion disapproving regulations that were not limited in

application to programs and activities directly receiving

federal financial assistance never reached the Senate floor

for a vote. S. Con. Res. 46, 94th Cong., 1st Sess., 121

Cong. Rec. 17300 (1975).83 Senators Helms also proposed

a bill that would have limited application of Title IX to

direct recipients of federal funds (S. 2146, 94th Cong.,

1st Sess,, 121 Cong. Rec. 23847 (1975)). It was never

passed.

In 1976, Senator McClure renewed the attempt to limit

Title IX by introducing an amendment defining federal

financial assistance as assistance that an institution re- 33

20

33 This Court; remarked in North Haven: “ [T]he relatively in

substantial interest given the resolutions of disapproval t-hat were

introduced [including the Helms resolution] seems particularly sig

nificant since Congress has proceeded to> amend § 901 when it has

disagreed with HEW’s interpretation of the; statute.” 456 U.S. at

534 (footnote omitted).

21

ceives directly from the federal government. 122 Cong.

Rec. 28144. The stated purpose of the amendment was to

eliminate HEW regulation of institutions where . .

the only Federal involvement is the aid that a student

may get.” Id. Senator Pell, the major Senate sponsor of

the provisions of the Education Amendments of 1972

providing for educational opportunity grants, challenged

the McClure proposal: “ [T]he enactment of this amend

ment would mean that no funds under the basic grant

program would be covered by Title IX. While these dol

lars are paid to students they flow through and ulti

mately go to institutions of higher education and I do not

believe we should take the position that these Federal

funds can be used for further discrimination based on

sex.” Id. at 28145 (1976) (emphasis added).84 The

McClure amendment was rejected. Id. at 28147.

The post-enactment history of Title IX thus shows that

Congress realized that HEW interpreted Title IX to en

compass educational institutions whose students received

BEOGs. Congress’ rejection of legislative challenges to

that interpretation, when viewed in light of its willing

ness to amend Title IX in other respects, strongly sup

ports the conclusion that Title IX coverage of schools

assisted by the BEOG grant program is in accord with

Congressional intent. As this Court remarked in North

Haven:

Where “an agency’s statutory construction has been

‘fully brought to the attention of the public and the

Congress,’ and the latter has not sought to alter that

interpretation although it has amended the statute 34

34 Senator Bayh supported Senator Pell: “The courts have held

that Title VI of the Civil Rights Act does apply if a student

receives Federal aid. If a student is benefited, the school is bene

fited. It is not new law; it is traditional, and I think in this

instance it is a pretty fundamental tradition, that we treat all

institutions alike as far as requiring them to' meet a standard of

educational opportunity equal for all of their students.” 122 Cong.

Rec. 28145-46 (1976).

in other respects, then presumably the legislative in

tent has been correctly discerned.”

456 U.S. at 535 (citations omitted).

II

AS A RECIPIENT OF FEDERAL FINANCIAL AS

SISTANCE THROUGH THE BEOG PROGRAM,

GROVE CITY COLLEGE MAY PROPERLY BE RE

QUIRED TO EXECUTE AN ASSURANCE OF COM

PLIANCE WITH TITLE IX

Petitioners’ second major argument is that Grove City

College may not be required to execute the Department

of Education’s Assurance of Compliance (“Assurance” )36

because the school would thereby be submitting to institu

tion-wide Title IX coverage in violation of the statute’s

“program specificity,” see North Haven, 456 U.S. at 536.

This argument fails for two reasons: first, the Assurance

and the applicable regulations meet North Haven's test

of program specificity; and second, because BEOGs assist

the institution’s entire program, Title IX applies to that

entire program.

A. The Title IX Assurance and Applicable Regulations

Are “Program-Specific” as Required by North Haven

In North Haven, this Court held that not only the fund

ing termination provisions of § 902, but also that section’s

grant of regulatory authority to the Department of Edu

cation and the § 901 prohibition against sex discrimina

tion, are “program-specific.” 456 U.S. at 536-38. It is

thus apparent that the Assurance which the Department

of Education requires that Grove City execute, and the

portions of the Title IX regulations applicable thereto,

must be examined to determine if they are consistent

with Title IX’s program specificity.

22

85 The Assurance of Compliance is a written acknowledgement by

a recipient of Federal financial assistance that it will operate its

education programs or activities in a manner consistent with

applicable Title IX regulations. 34 C.F.R. § 106.4 (1982).

23

North Haven provides guidance in this examination.

There, the Court reviewed Subpart E (Employment) of

the Title IX regulations and found it to be adequately

program-specific. The Court held that although the “em

ployment regulations do speak in general terms of an ed

ucational institution’s employment practices, . . . they

are limited by the provision that states their general pur

pose”—§ 106.1 of the Title IX regulations, which refers

to the “program or activity” language in the statute. Id.

at 538. See 34 C.F.R. § 106.1 (1982). In addition, the

Court noted, the Department’s comments accompanying

publication of its final Title IX regulations, by citing

Board of Public Instruction v. Finch, 414 F.2d 1068 (5th

Cir. 1969), indicated the agency’s intent that the regula

tions be interpreted in a program-specific manner. North

Haven, 456 U.S. at 538-39.

Applying the North Haven analysis to the present case,

it is clear that the regulations and the Assurance itself,

HEW Form 639, conform to the program-specific lan

guage of the Title IX statute. Under the Assurance, an

institution receiving federal assistance pledges to “ [c] om-

ply, to the extent applicable to it, with Title IX . . . and

all requirements imposed by . . . the Department’s regula

tions . . . to the end that, in accordance with Title IX . . .

no person . . . shall, on the basis of sex, be excluded from

participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be otherwise

subjected to discrimination under any education programs

or activity for which the applicant receives or benefits

from federal financial assistance.” HEW Form 639

(emphasis added). The Assurance, by limiting compli

ance to “the extent” Title IX applies to the institution

and to “programs or activity,” explicitly announces its

conformity with the statute’s program-specificity.

In addition, the regulations limit the institution’s obli

gation to comply with Title IX to “each education pro

gram or activity operated by the applicant or recipient

and to which this part [the Title IX regulations] applies.”

34 C.F.R. § 106.4(a) (1982) (emphasis added). Finally,

24

these portions of the regulations are also subject to the

general purpose section, § 106.1, which this Court found

adequately program-specific in North Haven, 456 U.S. at

538.

Just as this Court in North Haven rejected claims that

the employment regulations of Title IX were inconsistent

with the statute’s program-specificity, so too, must the

Court reject petitioners’ claims that the Assurance and

regulations are not program-specific.36 As the Court ex

plained, “regulations may be broadly worded and need

not be directed at specific programs—-as long as they are

applied only to programs that receive federal funds.”

456 U.S. at 536 n.27.37

B. Because BEOG Grants Provide Assistance to the En

tire Program of Grove City College, that Entire Pro

gram of the Institution is Covered by Title IX

We have suggested above that the Court is not required

in this case to attempt a general definition of “program

or activity,” as the term is used in § 901(a), because,

96 All that is a t issue in this case is the Assurance. The Depart

ment has not made any findings concerning the program(s) or

activity (ies) a t Grove City College which are covered by Title IX

or its regulations. Neither the district court nor the ALJ deemed

it necessary to address the meaning of “program or activity” in

relation to Grove City. Thus, we agree with Judge Becker, con

curring below, that it was unnecessary for the panel majority to

explore the subject.

87 Petitioners’ argument that the Department may not terminate

federal funding to a recipient which refuses to execute an Assurance

is baseless. The Assurance requirement is well within the agency’s

authority under § 902 to adopt regulations “of general applica

bility.” As the Third Circuit panel noted, the Assurance not only

identifies the type of institution applying for federal aid, but also

asks the school to provide information respecting grievance com

plaint procedures, requires a statement of self-evaluation, concern

ing the practices of the institution, and places th e . recipient on

notice that it must comply with Title IX and its regulations. 687

F.2d at 703. As such, the Court of Appeals found that the Assur

ance constituted a threshhold device facilitating the1 enforcement

of Title IX’s objectives. Id.

25

just as in North Haven, the Assurance and regulations

are adequately limited by the program-specificity con

cept.38 Even if the Court does not rest upon this ground,

however, it should affirm the judgment below since under

the specific facts of this case, the Third Circuit was cor

rect in holding that all of Grove City College is subject

to Title IX’s prohibition against sex discrimination.39

38 In North Haven, two local boards of education sought declar

atory and injunctive relief in situations where the Department of

Education had begun complaint investigations. Although the in

vestigation stage is much further along the continuum of the

enforcement scheme than the point a t which an. institution is asked

to complete an Assurance', this Court did not find it necessary to

define “program or activity.”

39 We recognize that in North Haven this Court apparently re

jected a reading of § 901 (a) which would extend its reach to- an

entire institution in every instance. 456 U.S. a t 537. There is

no need to> revisit that determination in the present case. But

there is likewise no basis upon which to conclude', as petitioners

argue, that by implication the Court' in North Haven was holding

that § 901(a) could never reach an entire institution.

Petitioners offer no coherent interpretation of §901 (a). On the

one hand, they suggest that the statutory language must refer to

something less than the entire program of an institution (see Pet.

Br. a t 14-15). On the other hand, petitioners concede (id. a t 20

n.18) the validity of the “infection” theory of Board of Public

Instruction v. Finch, which holds that federal funds may be

terminated under Title VI if discrimination in other areas of a

recipient’s operations “infects” a federally supported categorical

program. Necessarily, then, the scope of § 901(a) must be at least

broad enough to reach any part of a recipient’s operations which,

if conducted in a discriminatory manner, might “infect” a “pro

gram or activity receiving Federal financial assistance,” as peti

tioners narrowly define that term. Cf. Iron Arrow Honor Society

v. Heckler, 702 F.2d 549 (5th Cir. 1983).

Thus, to use an example proffered by petitioners (see Pet. Br.

at 20), if a university received federal funds to support a program

of research and instruction in chemistry (to advance an overall

Congressional goal of increasing the nation’s supply of qualified

scientists), it would clearly be a violation of Title IX if the school

permitted women to enroll in that program but required that they

26

In Part I of this brief, we described the purposes of

the Higher Education Act in general and the BEOG pro

gram specifically. See p. 7 supra. BEOGs provide stu

dents with the means to obtain undergraduate degrees,

and assist institutions of higher education to provide the

necessary instruction and related services and activities

to that end.40 The system of channeling aid through the

student, and of allowing the student to select the institu

tion which he or she will attend, provides a means of

preserving the institutional autonomy sought by Grove

City College (see Pet. Br. at 47-50). At the same time,

it necessarily means that BEOG funds, which must be

used for tuition, fees and other expenses associated with

attendance at the school that the student has chosen, sup

port whatever functions or activities the institution de

termines to offer as part of undergraduate education.

take a greater number of credits in other courses to earn an M.S.

or Ph.D. degree than it required of male students in the program.

Similarly, disparate treatment based on sex in such other areas

of a program enrollee’s necessary contact with the institution as

residential accommodations, honors, or extracurricular activities

would obviously be proscribed by Title IX.

Petitioners also suggest, citing Finch, that “the. concept of a

recipient program or activity under Title IX must; be co-extensive

with the scope of the underlying grant statute” (Pet. Br. a t 20).

We have explained in this footnote why this formula cannot mark

the outer limits of § 901 (a) under the Finch “infection” theory.

But even, accepting the formula arguendo for purposes of this case,

it leads to the conclusion (for the reasons stated in the text,

infra) that all of Grove City’s operations are subject to Title IX.

40 The purpose of the BEOG program is not, as petitioners sug

gest, to enable Grove City College or any other school to operate

a student assistance program. There are federal grant-in-aid

statutes which do provide such assistance. For example!, under

20 U.S.C. § 427 (NDEA), the federal government will loan money

directly to> an institution to enable it te meet its required 10%

match and to establish a student loan fund eligible for federal

capital contributions. And under 20 U.S.C. § 1070e, an institution

may receive federal payments to defray its expenses in administer

ing BEOGs.

27

There is no dispute in this case that without their

BEOGs, the individual petitioners would be unable to

attend Grove City. Hence there is no question that BEOG

funds are effectively used to pay tuition and fees charges,

and become part of the general operating funds of the

college. Absent a showing that it conducts administra

tively and programmatically separate, specialized activi

ties which are not related to undergraduate education, the

costs of which are defrayed from separate funds, and

which do not in any way benefit from the BEOG assist

ance to the school, all of Grove City’s operations are sub

ject to Title IX. The entire program of Grove City College

is the “education program or activity receiving Federal

financial assistance” through BEOGs.

This interpretation of § 901(a), where an institution

benefits from its students’ BEOG awards, is supported by

the statutory framework, the legislative history of Title

IX, the similar treatment of general-purpose aid under

Title VI, and events following upon the issuance of the

initial Title IX regulations in 1975. First, § 901(a) also

contains a series of specific exclusions from Title IX

coverage, many of which cover events or functions which

are very unlikely ever to receive earmarked federal sup

port. Unless Congress contemplated that at least in some

circumstances (such as where an institution receives

assistance for its overall educational program through

student aid grants) the scope of § 901(a) would be insti

tutionwide, there would be no reason to enact these provi

sions.41 Second, the principal sponsor of Title IX, Senator

Bayh, explicitly described the broad scope of Title IX,

emphasizing that it would reach any part of an institu

tion’s operations which could affect federal program par

ticipants.42 Third, when Title IX was enacted, at least

41 See Haffer v. Temple University, 524 F. Supp. 531, 541 (E.D.

Pa.), aff’d, 688 F.2d 14 (3d Cir. 1982).

42 When asked whether the language “any program or activity”

would reach “dormitory facilities . . . athletic facilities . . . or . . .

just educational requirements,” Bayh responded that “ [w]hat we

28

one federal court had already construed similar “program

or activity” language broadly with respect to an entity

receiving general support funds.48 Finally, when Con

gress reviewed the Title IX regulations issued by the

Department of HEW in 1975, there was major contro

versy and debate over the prohibition of discrimination in

extra-curricular athletic programs ; however, the regula

tions were not disapproved and in fact the Senate defeated

a series of amendments which would have narrowed the

scope of § 901 (a)’sprohibition on discrimination.* 43 44

are trying to do is provide equal access for women and men students

to the educational process and the extra-curricular activities in a

school . . . .” 117 Cong. Rec. 30407 (1971).

43 In Bossier Parish School Bd. v. Lemon, 370 F.2d 847 (5th

Cir.), cert, denied, 388 U.S. 911 (1967), a school district received

funds for construction and operations because of the location

within the district of an a ir force base. The court held that

acceptance of these “impact aid” funds after enactment of Title

VI “brought its school system within the class of programs subject

to the section 601 prohibition against discrimination.” Id. a t 852.

Senator Bayh indicated in 1975 that the: “program or activity”

language of Title IX had been intended to parallel the Bossier

Parish interpretation of Title VI. 121 Cong. Rec. 20468 (1975).

See also Boh Jones University v. Johnson, discussed supra p. 9.

44 See 120 Cong. Rec. 15322 (1974) (Tower amendment to exclude

“revenue producing” intercollegiate athletics); 121 Cong. Rec.

23845 (1975) (Helms amendment to exclude programs and activities

not receiving direct federal a id ) ; 122 Cong. Rec. 28136 (1976)

(McClure amendment to redefine “program or activity” to include

only curriculum or graduation requirements). Senator Bayh suc

cessfully opposed the amendments on the ground that they would

have exempted “areas of traditional discrimination against women

that are the reason for the . . . enactment of Title IX [including]

. . . scholarship . . . employment . . . and extra-curriculum [sic]

activities such as athletics.” Id. at 28144.

Senator Bayh testified a t the House of Representatives hearings

on the Title IX regulations in a similar fashion:

This objection to the coverage of programs which receive in

direct benefits from federal support—such as athletics—is

directly a t odds with the Congressional intent: to provide cov

erage of exactly such types of clear discrimination. For ex-

29

Petitioners’ argument that an educational institution

can never be a “program or activity” for purposes of Title

IX leads to an absurd result: institutions that receive

general support funds such as BEOGs would never be

covered by Title IX and would be able to use these funds

to support discriminatory programs. There is no evidence

that Congress intended to establish such a loophole in

Title IX enforcement. Given Congress’ intent in enacting

Title IX, “program or activity” should be liberally in

terpreted in a common-sense fashion that best effectuates

the purposes of Title IX: to protect citizens from dis

crimination and to eliminate federal financial support for

such discrimination.

The federal government, by providing students at an un

dergraduate institution with federal educational grants,

is also providing the institution as a whole with addi

tional resources which the institution may allocate as it

sees fit. In order to effectuate the remedial purposes of

Title IX, the Third Circuit’s decision that the entire

program of Grove City College is the “program or activity

receiving Federal financial assistance” should be upheld.

ample, although federal money does not go- directly to the foot