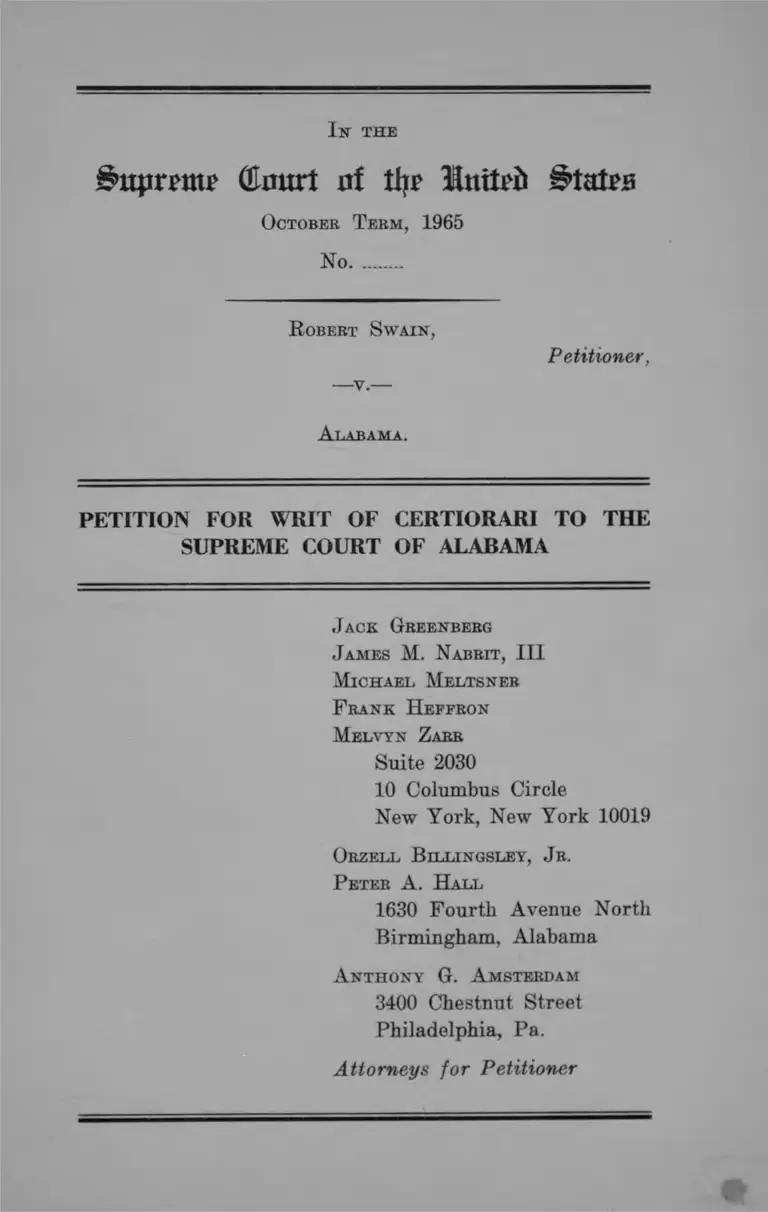

Swain v. Alabama Petition for Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

October 4, 1965

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Swain v. Alabama Petition for Writ of Certiorari, 1965. d19acb8a-c59a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/7436ee1e-4efe-4e66-90d4-439ab96c356b/swain-v-alabama-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed February 08, 2026.

Copied!

I n' the

£>ttprmp Court of tlje luitrfi ^tatra

October T erm, 1965

No..........

R obert Swain,

—v.—

A labama.

Petitioner,

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

SUPREME COURT OF ALABAMA

Jack Greenberg

J ames M. Nabrit, III

Michael Meltsner

F rank Heferon

Melvyn Zarr

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Orzell B illingsley, Jr.

P eter A. H all

1630 Fourth Avenue North

Birmingham, Alabama

A nthony G. A msterdam

3400 Chestnut Street

Philadelphia, Pa.

Attorneys for Petitioner

I N D E X

PAGE

Opinions Below ................................................................... 1

Jurisdiction ........................................................................... 1

Questions Presented ........................................................... 2

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved ..... 3

Statement ............................................................................... 4

Exclusion of Negroes from Jury Panels ............... 5

The Solicitor’s Remarks to the J u r y ....................... 6

The Application of the Death Sentence for Rape

in Alabama ............................................................... 8

Cruel and Unusual Punishment ............................... 10

Exclusion of Women from Jury Service ............... 10

How the Federal Questions Were Raised and Decided

B elow .................................................................................. 11

Reasons for Granting the Writ

I. Petitioner Adequately Alleged in His Petition

for Writ of Error Coram Nobis Below That His

Conviction Deprived Him of Due Process of Law

and Equal Protection of the Laws as Guaranteed

by the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitu

tion of the United States Because the Prose

cutor Systematically Struck Negroes from Petit

Jury Venires ............................................................ 14

11

II. Petitioner Was Denied Rights Under the Consti

tution When (A ) Denied the Opportunity to

Offer Proof of Racial Application of the Death

Penalty in Alabama and (B ) the Jury Which

Convicted and Sentenced Him Had Unfettered

Discretion to Impose Capital Punishment for

All Offenses of Rape—in the Absence of Ag

gravating Circumstances, Permitting Cruel and

Unusual Punishment ...... 19

A. Petitioner’s Equal Protection Contention

Which the Court Below Wrongly Refused

to Permit Him to Establish Presents an Im

portant Question for Consideration by this

Court on Certiorari ........................................... 19

B. The Court Should Grant Certiorari to Con

sider Petitioner’s Contention That His Sen

tence Is Unconstitutional Under the Eighth

and Fourteenth Amendments.................. 29

TII. Petitioner Was Denied Rights Under the Fifth

and Fourteenth Amendments When the Circuit

Solicitor Was Permitted to Comment on His

Failure to Take the Stand ................................... 32

IV. Petitioner Was Deprived of Due Process of Law

and Equal Protection of the Laws in Violation

of the Fourteenth Amendment Because Women

Were Systematically Excluded from the Juries

Which Indicted and Tried Him ........................... 34

Conclusion ............................................................................. 38

A ppendix

Judgment of Supreme Court of Alabama ............ la

Coram Nobis Petition ............................................... 2a

PAGE

T a b l e o f C a se s

page

Aaron v. Holman (M. D. Ala., C. A. No. 2170-N) ....... 22

Aaron v. State of Alabama, 273 Ala. 337, 139 So. 2d

309 ...................................................................................... 26

Akins v. Texas, 347 U. S. 475 ........................................... 17

Alabama v. Billingsley (Cir. Ct. Etowah County,

No. 743) ............................................................................ 26

Alabama v. Butler (Cir. Ct. Etowah County, No. 744) .. 26

Alabama v. Liddell (Cir. Ct. Etowah County, No. 745) .. 26

Allen v. State, 137 S. E. 2d 711, 110 Ga. App. 56 ....... 36

Anderson v. Martin, 375 U. S. 399 ...............................17, 23

Arnold v. North Carolina, 376 U. S. 773 ..................... 17

Ballard v. United States, 329 U. S. 187 ..................... 36

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483 .............. 23

Brown v. State, 277 Ala. 353, 170 So. 2d 504 .............. 15

Burstyn v. Wilson, 343 U. S. 495 ................................... 28

Bush v. Kentucky, 107 U. S. 110 ..................................... 24

Carr v. Montgomery County Bd. of Education, 232

F. Supp. 715 (M. D. Ala. 1964) ................................. 27

Carter v. Texas, 177 U. S. 442 .......................................16,17

Cline v. Frink Dairy Co., 274 U. S. 445 ........................... 28

Coleman v. Alabama, 377 U. S. 129................................... 24

Connally v. General Construction Co., 269 U. S. 385 .... 28

Cox v. Louisiana, 379 U. S. 536 ....................................... 28

Craig v. Florida (Sup. Ct. Fla., No. 34,101) ................... 19

Dombrowski v. Pfister, 380 U. S. 479 ............................... 28

Ex parte Hamilton, 271 Ala. 88, 122 So. 2d 602, rev’d,

368 U. S. 52 coram nobis petition granted, 273 Ala.

504, 142 So. 2d 868 ...................................................... 15

Ex parte Virginia, 100 U. S. 339 ................................... 16

IV

Ex parte Williams, 268 Ala. 535, 108 So. 2d 454, cert.

PAGE

den. 359 U. S. 1004 ..................... .......................... .......... 15

Eubanks v. Louisiana, 356 U. S. 584 ............................... 17

Fowler v. Rhode Island, 345 U. S. 6 7 ............................... 23

Freedman v. Maryland, 380 U. S. 51 ............................... 28

Gibson v. Mississippi, 162 U. S. 565 ............................... 16

Griffin v. California, 380 U. S. 609 .............................3, 32, 33

Hale v. Kentucky, 303 U. S. 613 ....................................... 17

Hamilton v. Alabama, 376 U. S. 650 ......... ................ .17, 23

Hamilton v. State, 273 Ala. 504, 142 So. 2d 868 ........... 15

Hernandez v. Texas, 347 U. S. 475 .......................17, 24, 35

Herndon v. Lowry, 301 U. S. 242 ................................... 28

Hill v. Texas, 316 U. S. 400 ............................................... 17

Hoyt v. Florida, 368 U. S. 57 ...................................34, 35, 36

Lee v. Macon County Bd. of Education, 231 F. Supp.

743 (M. D. Ala. 1964) ................................................... 27

Louisiana v. United States, 380 U. S. 145 ................... 28

Louisiana ex rel. Scott v. Hanchey (20th Jud. Dist. Ct.,

Parish of West Feliciana) ........................................... 22

MacLaughlin v. Florida, 379 U. S. 184 .......................23, 29

Malloy v. Hogan, 378 U. S. 1 ........................................... 32

Martin v. Texas, 200 U. S. 316 .......................................16-17

Maxwell v. Stephens, ------ F. 2d ------ (8th Cir.), No.

429, October Term 1965 ...............................................22, 29

Mitchell v. Stephens, 232 F. Supp. 497 (E. D. Ark.

1964) .................................................................................. 22

Moorer v. MacDougall (E. D. S. C., No. AC-1583) ....... 22

N.A.A.C.P. v. Alabama, 357 U. S. 449

N.A.A.C.P. v. Button, 371 U. S. 415

23

28

V

Napue v. Illinois, 360 U. S. 204 ....................................... 17

Neal v. Delaware, 103 U. S. 370 .......................................16, 24

Niemotko v. Maryland, 340 U. S. 268 ............................... 23

Norris v. Alabama, 294 U. S. 587 ................................... 17

Patton v. Mississippi, 332 U. S. 463 ............................... 17

Pennsylvania ex rel. Herman v. Clandy, 350 U. S. 116 .. 24

Pierre v. Louisiana, 306 U. S. 354 ................................... 17

Ralph v. Pepersack, 335 F. 2d 128 (4th Cir. 1964) ....29-30

Reece v. Georgia, 350 U. S. 8 5 ........................................... 17

Rogers v. Alabama, 192 U. S. 226 ................................... 16

Ross v. United States, 180 F. 2d 160 (6th Cir. 1950) .... 34

Rudolph v. Alabama, 375 U. S. 889 ...............................29, 31

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1 ....................................... 23

Skinner v. Oklahoma, 316 U. S. 535 ............................... 31

Smith v. Cahoon, 283 U. S. 553 ....................................... 28

Smith v. Texas, 311 U. S. 128 .......................................17, 36

Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U. S. 303 ...................16, 35

Swain v. State, 275 Ala. 508, 156 So. 2d 368 .......4,18, 30, 33

Taylor v. Alabama, 335 U. S. 252 ................................... 24

Viereck v. United States, 318 U. S. 236 ........................... 34

Watson v. City of Memphis, 373 U. S. 526 ................... 23

Wilson v. United States, 149 U. S. 60 ...........................32, 34

Winters v. New York, 333 U. S. 507 ............................... 28

Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U. S. 356 ...............................14, 23

S tatutes

18 U. S. C. §3841 .................................................................. 32

28 U. S. C. §1257(3) (1948) ................................. 1

PAGE

42 U. S. C. §2000(e)(2 )....................................................... 36

Rev. Stat. §1977 (1875), 42 U. S. C. §1981 (1964) ....... 23

Civil Rights Act of 1866, Ch. 31, §1, 14 Stat. 27 .......22, 24

Enforcement Act of May 31, 1870, ch. 114, §§16, 18,

16 Stat. 140, 144 ............................................................... 22

Ala. Const. §102 ............................................................... . 27

Ala. Code Ann. Tit. 14, §395 (Recomp. Vol. 1958) ....3, 8,10,

13,19, 29

Ala. Code Ann. Tit. 14, §360-61 ....................................... 27

Ala. Code Ann. Tit. 14, §§397, 398 ................................... 19

Ala. Code Ann. Tit. 15, §305 ...........................................4, 33

Ala. Code Ann. Tit. 30, §21 .......................................3,10, 34

Ala. Code Ann. Tit. 45, §248 ............................................... 27

Ala. Code Ann. Tit. 46, §189 ........................................... 27

Ala. Code Ann. Tit. 48, §§186, 196, 464 .......... ................ 27

Ala. Code Ann. Tit. 51, §244 ........................................... 27

Ark. Stat. Ann. §§41-3403, 432153 (1964 Repl. Vols.) .... 19

Ark. Stat. Ann. §41-3405 ................................................... 19

Ark Stat. Ann. §41-3411 ..................................................... 19

Fla. Stat. Ann. §794.01 (1964 Cum. Supp.) ................... 19

(la. Code Ann. §26-1302 (1963 Cum. Supp.) ................... 19

Ga. Code Ann. §26-1304 (1963 Cum. Supp.) ................... 19

Ky. Rev. Stat. Ann. §435.090 (1963) ............................... 19

La. Rev. Stat. Ann. §14:42 (1950) ............................... 19

Md. Ann. Code, art. 27, §12 ............................................... 19

Md. Ann. Code, art. 27, §§461, 462 (1957) ....................... 19

Miss. Code Ann. 1942 (Recomp. Vol. 1958), §1762 ....... 35

Miss. Code Ann. §2358 (Recomp. Vol. 1956) ................... 19

Vernon’s Mo. Stat. Ann. §559.260 (1953) ....................... 19

vi

PAGE

Nev. Rev. Stat. §200.360 (1963) ....................................... 19

Nev. Rev. Stat. §200.400 (1963) ....................................... 19

N. C. Gen. Stat. §14-21 (Recomp. Vol. 1953) ............... 19

Okla. Stat. Ann., tit. 21, §§1111, 1114, 1115 (1958) ....... 19

S. C. Code Ann. §§16-72, 16-80 (1962) ........................... 19

S. C. Code, 1952 §§38-52 ................................................... 35

Tenn. Code Ann. §§39-3702, 39-3703, 39-3704, 39-3705

(1955) ................................................................................ 20

Tex. Pen. Code Ann., arts. 1183, 1189 (1961) ............... 20

Va. Code Ann. §18.1-16 (1960) ....................................... 20

Va. Code Ann. §18.1-44 (Repl. Vol. 1960) ................... 20

Oth er A uthorities

Weihofen, The Urge to Punish, 164-165 (1956) ........... 27

Bullock, Significance of the Racial Factor in the Length

of Prison Sentences, 52 J. Crim. L., Crim. & Pol.

Sci. 411 (1961) ................................................................ 27

Fairman, Does the Fourteenth Amendment Incorporate

the Bill of Rights, 2 Stan. L. Rev. 5 (1949) ............... 22

Hartung, Trends in the Use of Capital Punishment,

284 Annals 8 (1952) ....................................................... 27

Lewis, The Sit-In Cases: Great Expectations, [1963]

Supreme Court Review 101 ........................................... 28

Packer, Making the Punishment Fit the Crime, 77

Harv. L. Rev. 1071 (1964) .........................................30,31

tenBroek, Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution

of the United States, 39 Calif. L. Rev. 171 (1951) .... 22

vii

PAGE

PAGE

viii

Wolfgang, Kelly & Nolde, Comparison of the Executed

and the Commuted among Admissions to Death

Row, 53 J. Crim. L., Crim. & Pol. Sci. 301 (1962) .... 27

Note, 109 U. Pa. L. Rev. 67 (1960) ................................... 28

Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess. 475 (Jan. 29, 1866)

1759 (4/4/1866) ............................................................... 24

Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess. 1758 (April 4, 1866) 24

New York Times, July 24, 1965, p. 1, col. 5 ................... 31

United States Department of Justice, Bureau of

Prisons, National Prisoner Statistics, No. 32: Ex

ecutions, 1962 (April 1963) ....................................... 21

I n t h e

(Eourt uf % llnitth States

October T erm, 1965

No..........

R obert Swain,

— v.—

A labama.

Petitioner,

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

SUPREME COURT OF ALABAMA

Petitioners pray that a writ of certiorari issue to review

the judgment of the Supreme Court of Alabama entered

in the above-entitled case on June 25, 1965.

Opinions Below

The order of the Supreme Court of Alabama denying

petition for leave to file petition for writ of error coram

nobis is unreported and is set forth in the appendix, infra,

p. la. No opinion accompained that order. The opinion

of the Supreme Court of Alabama affirmed by this Court

March 8, 1965, 380 U. S. 202, rehearing denied 381 U. S.

921, is reported at 275 Ala. 508, 156 So. 2d 368 (1963).

Jurisdiction

The judgment of the Supreme Court of Alabama was

entered June 25, 1965. The jurisdiction of this Court is

invoked pursuant to 28 U. S. C. § 1257(3), petitioner

2

having asserted below and asserting here deprivation of

rights secured by the Constitution of the United States.

Questions Presented

1. Whether petitioner was denied Fourteenth Amend

ment rights when tried and convicted by a jury chosen by

systematic and arbitrary exclusion of Negroes from jury

service as a result of an unvarying practice of the state’s

attorney who for 12 years always struck Negroes from

the petit jury or sought agreements with defense counsel

to strike all Negroes at the outset of the jury selection

procedure.

2. Whether petitioner, a Negro sentenced to death for

the rape of a white woman, was denied rights guaranteed

by the Fourteenth Amendment when he has shown that

11 times as many Negroes as whites have been executed

for rape in Alabama, a proportion at great variance with

the number of Negroes in the state’s population, or who

committed the crime of rape, and offers to show the grossly

disproportionate number of Negro executions can be ex

plained only by race.

3. Does Alabama’s grant to juries of unfettered dis

cretion to impose capital punishment for all offenses of

rape irrespective of the existence of aggravating circum

stances, permit cruel and unusual punishment in violation

of the Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments.

4. Whether petitioner was denied rights guaranteed by

the Fourteenth Amendment when the circuit solicitor

commented on petitioner’s failure to take the stand in his

3

own defense contrary to this Court’s decision in Griffin v.

California, 380 U. S. 609.

5. Whether petitioner was convicted in violation of his

Fourteenth Amendment rights when the State of Alabama

by statute makes women totally ineligible for jury service.

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved

This case involves the Eighth Amendment and Section 1

of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the

United States.

This case also involves the following statutes of the State

of Alabama:

Ala. Code Ann., Title 14, §395

Punishment of Rape. Any person who is guilty of the

crime of rape shall, on conviction, be punished, at the

discretion of the jury, by death or imprisonment in

the penitentiary for not less than ten years.

Ala. Code Ann., Title 30, §21

Qualifications of Persons on Jury Roll. The jury com

mission shall place on the jury roll and in the jury

box the names of all male citizens of the county who

are generally reputed to be honest and intelligent men

and are esteemed in the community for their integrity,

good character and sound judgment; but no person

must be selected who is under twenty-one or who is

an habitual drunkard, or who, being afflicted with a

permanent disease or physical weakness is unfit to

discharge the duties of a juror; or cannot read English

or who has ever been convicted of any offense involving

moral turpitude. I f a person cannot read English and

4

has all the other qualifications prescribed herein and

is a freeholder or householder his name may be placed

on the jury roll and in the jury box. No person over

the age of sixty-five years shall be required to serve

on a jury or to remain on the panel of jurors unless

he is willing to do so.

Ala. Code Ann., Title 15, §305

The Defendant in Criminal Cases a Competent Witness

for Himself. On the trial of all indictments, complaints,

or other criminal proceedings, the person on trial shall,

at his own request, but not otherwise, be a competent

witness; and his failure to make such a request shall

not create any presumption againt him, nor be the

subject of comment by counsel. I f the solicitor or other

prosecuting attorney makes any comment concerning

the defendant’s failure to testify, a new trial must be

granted on motion filed within thirty days from entry

of the judgment.

Statement

The petitioner was indicted for rape by the Grand Jury

of Talladega County, Alabama and convicted in the Circuit

Court of the County, May 25, 1962. The jury fixed his

punishment at death by electrocution. On appeal, the

judgment was affirmed by the Supreme Court of Alabama,

Swain v. State, 275 Ala. 508, 156 So. 2d 368 (1963).

Subsequently, on writ of certiorari, this Court affirmed

the judgment of the Supreme Court of Alabama finding

petitioner had failed to prove (1) exclusion of Negroes

from county grand and petit jury venires and (2) exclu

sion of Negroes from jury venires by the state’s misuse

of peremptory strikes in violation of the Fourteenth

5

Amendment, 380 U. S. 202, rehearing denied 381 U. S. 921

(1965).

On June 25, 1965, petitioner filed in the Supreme Court

of Alabama petition for leave to file petition for writ of

error coram nobis in the circuit court of Talladega County

(hereafter referred to as coram nobis petition) and peti

tion for stay of execution. Argument was heard imme

diately following filing by the full court, and on the same

day both petitions were denied. The coram nobis petition

and the order of the Supreme Court appear in the

appendix, infra, pp. la-25a. On July 2, 1965, Mr. Justice

Black granted a stay of execution pending the disposi

tion of this petition.

The verified coram nobis petition alleges that petitioner

has been tried, convicted and sentenced in violation of

the Constitution of the United States on a number of

grounds set forth in the petition, with supporting

affidavits.1 A summary of these allegations follows.

Exclusion of Negroes from fury Panels

Petitioner contends that he was deprived of due process

of law and the equal protection of the laws as guaranteed

by the Fourteenth Amendment by reason of systematic

and arbitrary exclusion of Negroes from service on petit

juries in the Circuit Court of Talladega County, as a

result of a consistent and unvarying practice of the circuit

solicitor who during a period of 12 years (1) always

struck Negroes from petit jury venires or (2) sought or

1 The coram nobis petition prayed that the Supreme Court of Alabama

grant an evidentiary hearing on those issues as to which attached affida

vits did not suffice (17a).

6

entered into agreements with defense counsel to strike all

Negroes at the outset of the jury selection procedure.

No Negro has served on a petit jury in the County

between 1950 and the date of petitioner’s trial in 1962

in either a civil or criminal case and petitioner offered

to prove “that the Circuit Solicitor of Talladega County

was responsible for the total absence of Negroes . . . in

that he consistently struck all Negroes remaining on the

venire if he was unable to obtain the agreement of defense

counsel to the elimination of Negro veniremen” (6a). It

was alleged that this Court “ indicated in its opinion in

this case [380 U. S. 202] that such a practice, if proved,

would constitute a violation of the Fourteenth Amend

ment” and that the issue “had not been adequately heard”

(6a).

Petitioner also alleged that he was “unable to present

proof of misuse of peremptory strikes by affidavit because

the individual best able to execute such an affidavit would

be the Circuit Solicitor who represented the State of

Alabama at petitioner’s trial and who is adverse to the

interest of petitioner. The peremptory strike issue, there

fore, can only be decided after a full hearing with com

pulsory process, examination and cross-examination of

witnesses” (6a).

The Solicitor’s Remarks To The Jury

Petitioner contends that he was deprived due process

of law and equal protection of the laws as guaranteed by

the Fourteenth Amendment because the circuit solicitor

(1) unfairly commented on his failure to take the stand

in his own defense and (2) aroused racial prejudice and

inflamed the minds of the jury (3a). It was alleged that

the transcript of petitioner’s trial revealed the circuit

7

solicitor made the following comments during his argu

ment before the jury (7a, 8a) :2

Gentlemen do you think we have proved these ele

ments? I submit to you it is not denied, there is not

a word come from this stand that denied the charge

of rape. We have proved it to you, gentlemen, beyond

a reasonable doubt that this prosecuting witness was

raped. Now the only question that the defendant has

raised here by his attorneys is the question of

identify (sic). (Emphasis added.) (Transcript p. 354.)

The solicitor further remarked:

Do you think this young lady, Jimmie Sue Butter-

worth, consented to have this defendant have the

rough and rugged intercourse where this impact

against her body caused loose hairs to come out of

his privates? You gentlemen know the way a colored

person—you have seen them you have seen their hair.

You know, gentlemen, it is coarse. You know that

it is rough. You know from your own experiences

with everyday life that when any two forces meet

each other and that there is a rubbing or banging

there are going to be hairs lost. Most of you men

are married men. You have had everyday experiences.

You know from your own knowledge that people shed

hairs and they lose them, but gentlemen how many

of you if they took us out and shook our clothes would

find negroid hairs falling from our privates? (Tran

script p. 354.)

2 The transcript of petitioner’s trial is part o f the certified record of

petitioner’s original appeal on file with the Court.

8

The Application of the Death Sentence For Rape In Alabama

The Alabama Code, Tit. 14 §395, punishes rape, at the

discretion of the jury, by death or imprisonment in the

penitentiary for not less than ten years. Petitioner was

sentenced to death upon conviction of raping a white woman.

The petition alleged that the State arbitrarily and dis-

criminatorily imposes the sentence of death upon Negroes

charged with rape, but does not impose the same penalty

upon white men charged with rape under the same circum

stances in violation of the Fourteenth Amendment and that

§395 violates the Fourteenth Amendment because it affords

the jury unlimited, unrestricted and unreviewable discre

tion in choice of sentence and does not establish any pro

cedure to permit separate consideration of guilt and sen

tence (4a).

The population of Alabama between 1930 and the present

according to the U. S. Census, has been 35.7% nonwhite

in 1930, 34.7% in 1940, 32.1% in 1950, and 30.1% in 1960.

Between January 1, 1930 and December 31, 1964, the State

of Alabama executed 134 persons, of whom 107 or 79%

were Negroes and 27 or 20.2% were white. Between Jan

uary 1, 1930 and December 31, 1964 the State of Alabama

executed 22 persons for the crime of rape. Twenty or 90.9%

of these were Negroes while 2 or 9.1% were white (11a).

Records on file in the Supreme Court of Alabama show,

to the extent that they reveal information concerning the

victims’ race, that in every case involving the execution

of a Negro or white man for the crime of rape, the victim

has been a white woman.3 Eleven of these case records

contain explicit statements that the victim was white. In

3 Allegations were supported by case citations, docket numbers, dates

ot decision as well as affidavits of attorneys who had examined the records

of the cases cited (20a-24a).

9

five other cases involving the execution of Negroes, a rea

sonable inference may be drawn that the victim was white.

Five other cases resulting in the execution of Negroes do

not disclose the race of the victim. There is information

in the records on file of the only two cases resulting in

execution of white persons from which the inference may

reasonably be drawn that the victim was white (lla-13a).

As of March 17, 1965, eighteen persons were committed

to Kilby Prison in Alabama awaiting execution, of whom

eleven were Negroes. Both of the men under sentence for

rape were Negroes convicted of raping white women (13a-

14a). At the time the petition was filed the only other

cases of defendants known to be presently under sentence

of death for rape were three Negro men separately tried

and convicted for rape of a white woman in Etowah County,

Alabama (13a).

The gross disparity shown between the proportion of

Negroes in the population and the proportion of Negroes

sentenced to death and executed for the crime of rape is

the result of a racially discriminatory system of justice

and is not explainable by other factors reasonably related

to a rational system of imposing sentence. Negroes have

been sentenced to death for a crime which, if committed by

persons of the white race, would not have resulted in im

position of the death penalty (14a).

Petitioner offered to prove that race is the sole explana

tion for this disproportion by reference to judicial records

and testimony of attorneys in rape cases in all counties of

Alabama, or a representative sample of Alabama counties.

He sought “ a full hearing with opportunity to prove his

allegations with the benefit of compulsory process of wit

nesses, production of records, examination and cross-exami

nation of witnesses,” and alleged that “ proper development

10

of this fundamental issue of constitutional law requires an

evidentiary hearing with the full opportunity for full and

effective preparation” (14a).

Cruel and Unusual Punishment

Petitioner alleged that he was deprived of Eighth and

Fourteenth Amendments rights in that (1) he was sen

tenced to death for the crime of rape without consideration

of aggravating or mitigating circumstances; and (2) on its

face and as applied Ala. Code Ann. Title 14, §395 prescribes

cruel and unusual punishment for the reason that it pro

vides for a jury verdict which simultaneously determines

guilt and fixes sentence at death without permitting separate

consideration of guilt and sentence (4a-5a).4

Capital punishment is retained for the crime of rape in

only 17 states and 4 countries. Petitioner alleged that

imposition of such a penalty for rape violates evolving

standards of decency which are almost universally accepted.

The taking of human life to protect a value other than

human life is inconsistent with the constitutional prescrip

tion against punishments which are greatly dispropor

tionate to the offense charged. Permissible aims of punish

ment, such as deterrence, isolation, and rehabilitation can be

achieved as effectively by punishing rape less severely than

by death and this penalty constitutes unnecesary cruelty

(15a-16a).

Exclusion of Women From Jury Service

Petitioner was indicted, tried and convicted by a jury

selected pursuant to Ala. Code Ann. Tit. 30 §21 which pro

vides that women are ineligible for service on grand and

In addition, petitioner alleged that he was deprived of the opportunity

to present evidence in mitigation without taking the stand in his own

defense and forfeiting the privilege against self incrimination (15a).

11

petit juries in violation of his rights under the Fourteenth

Amendment (5a, 6'a, 17a).

How the Federal Questions Were Raised and

Decided Below

Before his trial in the Circuit Court of Talladega County,

petitioner made motions raising the issue of racial dis

crimination in violation of his Fourteenth Amendment

rights in the selection of persons for the jury roll, the grand

jury venire, the grand jury, the petit jury venire and the

petit jury as sworn. These motions were denied by the

trial court and denial was affirmed by the Supreme Court

of Alabama, 275 Ala. 508, 156 So. 2d 368 (1963). On certio

rari, this Court affirmed, 380 U. S. 202, rehearing denied,

381 U. S. 921 (1965), on the ground that petitioner had

failed to prove racial discrimination in the selection of the

venires or of trial jury panels in violation of the Four

teenth Amendment, but indicated additional evidence might

show systematic misuse of peremptory strikes in violation

of the Constitution.

In affirming petitioner’s conviction, the Supreme Court

of Alabama also found (156 So. 2d at 378) that the circuit

solicitor had not violated Alabama law and commented on

the failure of petitioner to testify when during summation

to the jury he stated:

Gentlemen, do you think we have proved these three

elements? I submit to you that it is not denied the

charge of rape. We have proved it for you, gentlemen,

beyond a reasonable doubt that this prosecution wit

ness was raped. Now the only question that the defen

dant has raised here by his attorneys is the question

of identify (sic).

12

Subsequent to this Court’s affirmance of the judgment

of the Supreme Court of Alabama petitioner filed in that

court a petition for leave to file petition for writ of error

coram nobis in the Circuit Court of Talladega County

following recognized post-conviction procedure under Ala

bama law. After oral argument, the petition was denied

without opinion by the Supreme Court of Alabama, June

25, 1965 (la ).

The coram nobis petition alleged deprivation of peti

tioner’s rights under the Eighth Amendment and the due

process and equal protection clauses of the Fourteenth

Amendment to the Constitution by reason o f :

(a) systematic and arbitrary exclusion of Negroes from

jury service as a result of a systematic practice of the cir

cuit solicitor, who always struck Negroes from the petit

jury venire or sought or entered into agreements with de

fense counsel so that all Negroes would be struck;

(b) argument of the circuit solicitor before the jury

which unfairly commented on petitioner’s failure to take

the stand in his own defense;

(c) argument of the circuit solicitor before the jury

which aroused racial prejudice and inflamed the minds of

the jurors;

(d) arbitrary and discriminatory imposition of the pen

alty of death against Negroes charged with the crime of

rape against white women and not imposing the same pen

alty against white men charged with rape in similar circum

stances ;

(e) determination of sentence by a jury which had un

limited, undirected and unreviewable discretion in choice

of sentence;

13

(f) a jury verdict which simultaneously determined peti

tioner’s guilt and fixed his sentence at death and did not

permit separate consideration of the issues of guilt and

sentence;

(g) sentence of death for the crime of rape without con

sideration of aggravating or mitigating circumstances pur

suant to Title 14, §395, Ala. Code Ann., which statute on

its face and as applied prescribes the imposition of cruel

and unusual punishment;

(h) total exclusion of women from the jury which tried,

convicted and sentenced petitioner.

In support of these allegations, petitioner set forth facts

appearing on the record of his trial, and the records and

files of the Supreme Court of Alabama and reports of

agencies of the United States. Attached to the petitions

were affidavits which attested to the accuracy of those alle

gations founded on public records and government reports.

Certain of the allegations raised questions of fact as to

which petitioner requested an evidentiary hearing and the

opportunity to present proof.

14

Reasons for Granting the Writ

I.

Petitioner Adequately Alleged In His Petition For

Writ Of Error Coram Nobis Below That His Conviction

Deprived Him Of Due Process Of Law And Equal Pro

tection Of The Laws As Guaranteed By The Fourteenth

Amendment To The Constitution Of The United States

Because The Prosecutor Systematically Struck Negroes

From Petit Jury Venires.

In its earlier opinion in this case, the Court implied5

that persistent use by a prosecutor of peremptory chal

lenges to totally exclude Negroes from petit juries would

constitute a violation of the Fourteenth Amendent, saying

(380 U. S. 223-24):

[W]hen the prosecutor in a county, in case after

case, whatever the circumstances, whatever the crime

and whoever the defendant or the victim may be, is

responsible for the removal of Negroes who have been

selected as qualified jurors by the jury commissioners

and who have survived challenges for cause, with the

result that no Negroes ever serve on petit juries, the

Fourteenth Amendment claim takes on added signif

icance. Cf. Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 IT. S. 356. In

these circumstances, giving even the widest leeway

to the operation of irrational but trial-related suspi

cious and antagonisms, it would appear that the pur

poses of the peremptory challenge are being perverted.

If the State has not seen fit to leave a single Negro

on any jury in a criminal case, the presumption pro

•' Petitioner was not alone in reading this implication. See Mr. Justice

Harlan’s concurrence (380 U. S. at 228).

15

tecting the prosecutor may well be overcome. Such

proof might support a reasonable inference that Ne

groes are excluded from juries for reasons wholly

unrelated to the outcome of the particular case on

trial and that the peremptory system is being used

to deny the Negro the same right and opportunity to

participate in the administration of justice enjoyed

by the white population. These ends the peremptory

challenge is not designed to facilitate or justify.

Petitioner asks the Court to now make explicit what

it suggested earlier. Faced with this Court’s holding that

the record before it was insufficient to support petitioner’s

constitutional claims, petitioner attempted below to docu

ment the prosecutor’s abuse of the peremptory challenge

system.6 The court below refused to permit such a showing,

necessarily holding that petitioner’s allegations in his coram

nobis petition did not state a federal claim.7 Petitioner

contends the contrary.

The petition alleged (3a, 6 a ):

Petitioner, who is a Negro, was deprived of due

process of law and equal protection of the laws as

6 Petitioner averred that he was unable to offer conclusive evidence in

affidavit form, since only through a full evidentiary hearing, featuring the

testimony o f the circuit solicitox-, could he prove his federal claim (6a).

7 Writ of error coram, nobis is available in Alabama as a post-conviction

remedy for the hearing and determination of claimed denials of federal

constitutional rights. Ex parte Hamilton, 271 Ala. 88, 122 So. 2d 602

(1960), rev’d, 368 U. S. 52, coram nobis petition granted, Hamilton v.

State, 273 Ala. 504, 142 So. 2d 868 (1962); Brown v. State, 277 Ala. 353,

170 So. 2d 504 (1965). Where conviction has been appealed to the Su

preme Court of Alabama and affirmed, a petition for writ o f error coram

nobis may not be filed in the trial court without leave granted by the

Supreme Court o f Alabama. See, e.g., Ex parte Williams, 268 Ala. 535,

108 So. 2d 454 (1959), cert. den. 359 U. S. 1004. Thus, Swain petitioned

the Alabama Supreme, Court for leave to file a coram nobis petition in

the trial court.

16

guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment to the Con

stitution of the United States by reason of systematic

and arbitrary exclusion of Negroes from service on

petit juries in the Circuit Court of Talladega County,

as the result of a consistent and unvarying practice

of the Circuit Solicitor, who during a period of twelve

years always struck Negroes from the petit jury venire

and sought or entered into agreements with defense

counsel so that all Negroes would be struck at the

outset of the jury selection procedure.

# * *

No Negro served on a petit jury in Talladega County

between 1950 and the date of petitioner’s trial in 1962

in either a civil or criminal case. Petitioner offers to

prove that the Circuit Solicitor of Talladega County

was responsible for the total absence of Negroes on

petit juries in criminal cases in that he consistently

struck all Negroes remaining on the venire if he was

unable to obtain the agreement of defense counsel

to the elimination of Negro venireman.

Surely these allegations were sufficient to support proof

of the kind required by this Court, viz., proof to “ show

the prosecutor’s systematic use of peremptory challenges

against Negroes over a period of time” (380 U. S. at 227).

This proof, erroneously disallowed below, would document

a violation of the Fourteenth Amendment.

In an unbroken line of cases since 1880, this Court

has consistently held that a state cannot systematically

exclude persons from juries because of their race. Strauder

v. West Virginia, 100 U. S. 303; Ex parte Virginia, 100

U. S. 339; Neal v. Delaware, 103 U. S. 370; Gibson v.

Mississippi, 162 U. S. 565; Carter v. Texas, 177 U. S. 442;

Rogers v. Alabama, 192 U. S. 226; Martin v. Texas, 200

17

U. S. 316; Norris v. Alabama, 294 U. S. 587; Hale v. Ken

tucky, 303 U. S. 613; Pierre v. Louisiana, 306 U. S. 354;

Smith v. Texas, 311 U. S. 128; Hill v. Texas, 316 U. S. 400;

Akins v. Texas, 347 U. S. 475; Reece v. Georgia, 350 U. S.

85; Eubanks v. Louisiana, 356 U. S. 584 and Arnold v.

North Carolina, 376 U. S. 773. Whether by statute or by

administrative action, overtly or covertly, the unlawful

discrimination has been flushed out and condemned. “I f

there has been discrimination, whether accomplished in

geniously or ingenuously, the conviction cannot stand”

Smith v. Texas, 311 U. S. 128, 132. Abuse of the peremp

tory challenge system presents systematic exclusion of

Negroes from juries in a somewhat altered form; never

theless, the discrimination is substantial and poses the

same danger to “basic concepts of a democratic society

and a representative government.” Smith v. Texas, 311

U. S. 128, 130. The decisions of this Court do not say

that Negroes may be systematically excluded by state ac

tion from jury service as long as they are called for jury

service. The constitutional duty of state officers is clear

and unequivocal: “not to pursue a course of conduct in

the administration of their office which would operate to

discriminate in the selection of jurors on racial grounds.”

Hill v. Texas, 316 U. S. 400, 404; see also Hamilton v.

Alabama, 376 U. S. 650; Napue v. Illinois, 360 U. S. 204;

Anderson v. Martin, 375 U. S. 399. The equal protection

clause demands no less than recognition that Negroes may

not be systematically excluded by the state from jury ser

vice simpliciter. Carter v. Texas, 177 U. S. 442, 447;

Norris v. Alabama, 294 U. S. 587, 589; Patton v. Missis

sippi, 332 U. S. 463, 466; Hernandez v. Texas, 347 U. S.

475, 479; and Eubanks v. Louisiana, 356 U. S. 584, 585, 587.

To permit the insulation of abuses of peremptory chal

lenges from judicial scrutiny would be an exaltation of

18

form over substance so mischievous as to seriously weaken

the administration of justice in this country; it would

encourage state officials to accomplish by indirection what

they have been carefully taught by this Court over the last

85 years is forbidden by the equal protection clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment.

By denying the coram nobis petition, the Supreme Court

of Alabama failed to understand this Court’s opinion in

Swain v. Alabama, supra, which expressly provides for

petitioner to seek relief if he proves systematic Negro

exclusion by means of the prosecutor’s peremptory strikes.

If the Alabama Supreme Court misreads this Court’s

opinion in Swain, supra, there is every reason to expect

that a United States District Court on habeas corpus may

do likewise. Thus, this Court should grant certiorari to

free the matter from doubt rather than remitting petitioner

to an uncertain and probably futile habeas forum.

19

n.

Petitioner Was Denied Rights Under The Constitu

tion When (A ) Denied The Opportunity To Offer

Proof Of Racial Application Of The Death Penalty In

Alabama And (B ) The Jury Which Convicted And

Sentenced Him Had Unfettered Discretion To Impose

Capital Punishment For All Offenses Of Rape— In The

Absence of Aggravating Circumstances, Permitting

Cruel And Unusual Punishment.

A. Petitioner’s Equal Protection Contention Which The Court

Below Wrongly Refused To Permit Him To Establish

Presents An Important Question For Consideration By

This Court On Certiorari.

Seventeen American States retain capital punishment

for rape. Nevada permits imposition of the penalty only

if the offense is committed with extreme violence and

great bodily injury to the victim;8 the remaining sixteen

jurisdictions—which allow their juries absolute discretion

to punish any rape with death—are all southern or border

states.9 The federal jurisdiction and the District of

8 Nev. Rev. Stat. §200.360 (1963). See also §200.400 (aggravated as

sault with intent to rape).

9 The following sections punish rape or carnal knowledge unless other

wise specified. Ala. Code §§14-395, 14-397, 14-398 (Recomp. Vol. 1958);

Ark. Stat. Ann. §§41-3403, 432153 (1964 Repl. Y o ls .); see also §41-3405

(administering potion with intent to rape) ; §41-3411 (forcing marriage);

Fla. Stat. Ann. §794.01 (1964 Cum. S u pp.); Ga. Code Ann. §§26-1302,

26-1304 (1963 Cum. S u pp.); Ky. Rev. Stat. Ann. §435.090 (1963); La.

Rev. Stat. Ann. §14:42 (1950) (called aggravated rape but slight force

is sufficient to constitute offense; also includes carnal knowledge); Md.

Ann. Code, art. 27, §§461, 462 (1957); see also art. 27, §12 (assault with

intent to rape) ; Miss. Code Ann. §2358 (Recomp. Vol. 1956); Vernon’s

Mo. Stat. Ann. §559.260 (1953); N. C. Gen. Stat. §14-21 (Recomp. Vol.

1953); Okla. Stat. Ann., tit. 21, §§1111, 1114, 1115 (1958); S. C. Code

Ann. §§16-72, 16-80 (1962) (includes assault with attempt to rape as

20

Columbia, with its own strong southern traditions, also

allow the death penalty for rape.10

Between 1930 and 1962, the year in which petitioner

was sentenced to die, 446 person were executed for rape

in the United States. Of these, 399 were Negroes, 45

were whites, and 2 were Indians. All were executed in

Southern or border States or the District. The per

centages—89.5% Negro, 10.1% white—are revealing when

compared to similar racial percentages of persons executed

during the same years for murder and other capital

offenses. Of the total number of persons executed in the

United States, 1930-1962, for murder, 49.1% were Negro;

49.7% were white. For other capital offenses, 45.6%

were Negro; 54.4% were white. Louisiana, Mississippi,

Oklahoma, Virginia, West Virginia and the District of

Columbia never executed a white man for rape during

these years. Together they executed 66 Negroes. Arkan

sas, Delaware, Florida, Kentucky and Missouri each

executed one white man for rape between 1930 and 1962.

Together they executed 71 Negroes. Putting aside Texas

(which executed 13 whites and 66 Negroes), sixteen

Southern and border States and the District of Columbia

between 1930 and 1962 executed 30 whites and 333 Negroes

for rape; a ratio of better than one to eleven. Clearly,

unless the incidence of rape by Negroes is many times

that of rape by whites, capital punishment for rape

well as rape and carnal knowledge); Tenn. Code Ann. $§39-3702, 39-3703,

39-3704, 39-3705 (1955); Tex. Pen. Code Ann., arts. 1183, 1189 (1961);

Va. Code Ann. $18.1-44 (Repl. Vol. 1960); see also $18.1-16 (attempted

rape).

10 18 U. S. C. $2031 (1964) ; 10 U. S. C. $920 (1964); D. C. Code Ann.

$22-2801 (1961).

21

survives in the twentieth century principally as an instru

ment of racial repression.11

11 The figures in this paragraph are taken from United States Depart

ment of Justice, Bureau o f Prisons, National Prisoner Statistics, No. 32;

Executions, 1962 (April 1963). Table 1 thereof shows the following

executions under civil authority in the United States between 1930 and

1962:

Murder

Total White Negro Other

Number ............... 3298 1640 1619 39

Per cent ............. 100.0 49.7

Rape

49.1 1.2

Total White Negro Other

Number ............... 446 45 399 2

Per Cent ............. . 100.0 10.1

Other Offenses

89.5 .04

Total White Negro Other

Number ............... 68 37 31 0

Per Cent ............. 100.0 54.4 45.6 0.0

Table 2 thereof shows the following executions under civil authority in

the United States between 1930 and 1962, for the offense of rape, by State:

White Negro Other

Federal ........... ............ 2 0 0

Alabama........... ............ 2 20 0

Arkansas ......... ............ 1 17 0

Delaware ......... ............ 1 3 0

District o f Columbia ................ 0 2 0

Florida ............. ............ 1 35 0

Georgia ........... ............ 3 58 0

Kentucky ......... ............ 1 9 0

Louisiana ......... ............ 0 17 0

Maryland ......... ............ 6 18 0

Mississippi....... ............ 0 21 0

Missouri ........... ......... . 1 7 0

North Carolina ........... 4 41 2

Oklahoma......... ............ 0 4 0

South Carolina ............ 5 37 0

Tennessee......... ............ 5 22 0

Texas ............... ........... 13 66 0

Virginia ........... ........... 0 21 0

West Virginia ........... 0 1 0

45 399 2

22

If this be so—if the racially unequal results in these

States derive from any cause which takes account of

race as a factor in meting out punishment—a Negro

punished by death is denied, in the most radical sense,

the equal protection of the laws.12 One of the cardinal

purposes of the Fourteenth Amendment was the elimina

tion of racially discriminatory criminal sentencing. The

first Civil Rights Act of April 9, 1866, ch. 31, § 1, 14 Stat.

27, declared the Negroes citizens of the United States

and guaranteed that “ such citizens, of every race and

color , . . . shall be subject to like punishment, pains, and

penalties [as white citizens], and to none other, any law,

statute, ordinance, regulation, or custom, to the contrary

notwithstanding.” The Fourteenth Amendment was de

signed to elevate the Civil Rights Act of 1866 to constitu

tional stature. See e.g., tenBroek, Thirteenth Amendment

to the Constitution of the United States, 39 Calif. L. Rev.

171 (1951); Fairman, Does the Fourteenth Amendment

Incorporate the Bill of Rights, 2 Stan. L. Rev. 5 (1949).

The Enforcement Act of May 31, 1870, ch. 114, §§ 16, 18,

16 Stat. 140, 144, implemented the Amendment by reenact

ing the 1866 act and extending its protection to all persons.

Fhis explicit statutory prohibition of racially discrimina

The contention that racially discriminatory application o f the death

penalty in rape cases denies equal protection has been raised in a number

of cases now pending in state and federal courts, including this Court.

See^e.g., Maxwell v. Stephens,------ F. 2 d -------- (8th Cir., decided June 30,

1965), petition for Writ of Certiorari pending No. 429, October Term,

1965; Mitchell v. Stephens, 232 F. Supp. 497, 507 (E. D. Ark. 1964)

appeal pending; Moorer v. MacDougall, U. S. Dist. Ct„ E. D. S. C., No!

AC-1583, petition for writ o f habeas corpus pending; Aaron v. Holman,

U. S. Dist. Ct., M. D. Ala., C. A. No. 2170-N, proceedings on petition for

writ o f habeas corpus stayed pending exhaustion of state remedies July

2, 1965; Alabama v. Billingsley, Cr. Ct. Etowah County, No. 1159, motion

for new trial and motion for reduction of sentence pending; Craig v

Florida, Sup. Ct. Fla., No. 34,101, appeal from denial of motion for re

duction of sentence pending; Louisiana ex rel. Scott v. Hanchey, 20th Jud.

Dist. Ct., Parish of West Feliciana, petition for habeas corpus pending.

23

tory sentencing survives today as Rev. Stat. §1977 (1875),

42 U. S. C. §1981 (1964).

For purposes of the prohibition, it is of course im

material whether a State writes on the face of its statute

books: “Rape shall be punishable by imprisonment . . .,

except that rape by a Negro of a white woman, or any

other aggravated and atrocious rape, shall be punishable

by death by electrocution,” or whether the State’s juries

read a facially color-blind statute to draw the same racial

line. Discriminatory application of a statute fair upon

its face is more difficult to prove, but no less violates the

State’s obligation to afford all persons within its juris

diction the equal protection of the laws. E.g., Yick Wo v.

Hopkins, 118 U. S. 356 (1886); Niemotko v. Maryland,

340 U. S. 268 (1951) (alternative ground); Fowler v.

Rhode Island, 345 U. S. 67 (1953); Hamilton v. Alabama,

376 U. S. 650 (1964) (per curiam).13 And it does not

matter that the discrimination is worked by a number of

separate juries functioning independently of each other,

rather than by a single state official. However, it may

divide responsibility internally, the State is federally

obligated to assure the equal application of its laws.14 *

This Court has long sustained claims of discriminatory

13 It is also immaterial whether a State imposes different penalties for

classes of cases defined in terms of race, or whether it imposes a penalty

of death in all cases of a given crime, subject to the option of the jury

in some racially defined sub-class of the cases. The Fourteenth Amend

ment’s obligation of equality extends not only to those “rights” which a

State is federally compelled to give its citizens, but also to any benefits

the State may choose to give any class of them, however gratuitously.

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483 (1954); Watson v. City of

Memphis, 373 U. S. 526 (1963) ; McLaughlin v. Florida, 379 U. S. 184.

14 Execution by the State of the death sentence which it has given juries

discretion to impose clearly provides that “ interplay of governmental and

private action,” N.A.A.C.P. v. Alabama, 357 U. S. 449, 463 (1958), quoted

in Anderson v. Martin,..375 U. S. 399, 403 (1964), which makes the State

responsible for the discrimination. Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1 (1948).

24

jury exclusion upon a showing of exclusion continuing

during an extended period of years, without inquiry

whether the same jury commissioners served throughout

the period. See e.g., Neal v. Delaivare, 103 U. S. 370

(1881); Bush v. Kentucky, 107 U. S. 110 (1882); Hernandez

v. Texas, 347 U. S. 475 (1954). Congress, when it enacted

the 1866 Civil Rights Act knowing that “In some com

munities in the South a custom prevails hy which different

punishment is inflicted upon the blacks from that meted

out to whites for the same offense,” 15 intended precisely

by the Act, and subsequently by the Fourteenth Amend

ment, to disallow such “custom” as it operated through

the sentences imposed hy particular judges and juries.16

Because Alabama has foreclosed petitioner’s opportunity

to establish racially discriminatory application of the

death penalty by denial of his coram nobis petition, the

only question is whether his allegations are reasonable

and sufficient if true to state a constitutional violation.

Pennsylvania ex rel. Herman v. Clandy, 350 TJ. S. 116;

Coleman v. Alabama, 377 U. S. 129,133; Taylor v. Alabama,

335 U. S. 252.

Examination of petitioner’s cor am nobis petition reveals

distinct, precise and positive allegations which place

beyond question petitioner’s reliance on a substantial

claim under the equal protection clause. Petitioner is a

Negro:

Who is charged with the rape of a white woman

and sentenced to death for that crime in the State

15 Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess. 1758 (4/4/1866) (remarks of

Senator Trumbull, who introduced, reported and managed the bill which

became the act).

16 See the text o f the act supra; see also, e.g., Cong. Globe, 39th Cong.,

1st Sess. 475 (1/29/1866), 1759 ( 4/4/1866) (remarks of Senator Trum

bull).

25

of Alabama which State, its subdivisions, instrumen

talities, officers and agents, through policy, practice,

custom and usage, arbitrarily and discriminatorily

imposes the death penalty against Negroes charged

with the crime of rape against white women but does

not impose this same penalty against white men

charged with the crime of rape in similar circum

stances (4a).

United States Census statistics show that Alabama’s

population from 1930 to the present consisted of a non

white population ranging from 30.1% to 35.7%. Between

1930 and 1964 the State executed 134 persons of whom

107 or 79.8% were Negroes and 27 or 20.2% were white.

As of March 17, 1965, 18 persons were committed to Kilby

Prison awaiting execution of whom 11 were Negroes and

seven were white. During this 24 year period, 1930-1964,

the State executed 22 persons for the crime of rape of

whom 20 or 90.9% were Negroes and two or 9.1% were

white. Two persons presently committed to Kilby Prison

awaiting execution for the crime of rape are both Negroes.

To the extent records on file in the Supreme Court of

Alabama, involving execution for rape indicate the race

of the victim they show that for the crime of rape, the

victim of the crime was a white woman in every case.17

17 Eleven of the cases reveal the race of the victim expressly. In five

other cases in which Negroes were executed for the crime of rape, infor

mation in the record leads to a fair inference that the victim was white.

In five of the cases resulting in the execution of Negroes for the crime of

rape, the transcript of trial does not disclose the race of the victim. In

the only two cases resulting in the execution of white persons for the crime

of rape, there is information in the record on file in the Supreme Court

of Alabama from which the inference may be fairly drawn that the victim

o f the crime was white. The docket numbers, dates o f decision or cita

tion of these cases are set forth in the petition. The two men presently

awaiting execution in Kilby Prison both have been convicted of the rape

of a white woman. One is petitioner in this case, and the other is

26

The petition expressly alleges that “ the gross disparity

shown above between the proportion of Negroes in the

population and the proportion of Negroes sentenced to

death and executed for the crime of rape is the result

of a racially discriminatory system of justice and is not

explainable of other factors reasonably related to the ra

tional system of imposing sentence” and that “ Negroes

have been sentenced to death for crimes which if com

mitted by persons of the white race would not have re

sulted in imposition of the death penalty” (14a). Peti

tioner offered to prove that race is the sole explanation

for the grossly disproportionate number of Negro execu

tions for rape by reference to judicial records and the

testimony of attorneys in rape cases in all counties of

Alabama or a representative sample of Alabama counties

(14a), and sought a “hearing with opportunity to prove

his allegations with the benefit of compulsory process of

witnesses, production of records, examination and cross-

examination of witnesses” (14a).

Petitioner should be accorded an opportunity to estab

lish these substantial allegations. Several considerations

support the holding.

First, the hypothesis of racial discrimination is par

ticularly likely in view of the coincidence between the

Alabama figures and those of the other jurisdictions—

all southern—which have executed persons for rape dur-

Drewey Aaron, Jr., a Negro also convicted of the rape of a white woman.

See Aaron v. State o f Alabama, 273 Ala. 337, 139 So. 2d 309, 1961. In

the only other case known to the petitioner of defendants presently under

sentence of death for the crime of rape in Alabama, three men were sep

arately tried, convicted and sentenced to death for the crime of rape

against a white woman in Etowah County. Motions for new trial and for

reduction of sentence are pending in the cases of Alabama v. Billingsley,

Jr., Cir. Ct., No. 743; Alabama v. Butler, Cir. Ct., No. 744; Alabama v.

Liddell, Cir. Ct., No. 745.

27

ing the past thirty years. For all jurisdictions, the Negro-

white ratio is nine to one— although for other crimes

than rape it is about one to one. Studies and observa

tions by students of the criminal process tend to support

the hypothesis of discrimination. E.g. Bullock, Significance

of the Racial Factor in the Length of Prison Sentences,

52 J. Crim. L., Crim. & Pol. Sci. 411 (1961); Wolfgang,

Kelly & Nolde, Comparison of the Executed and the

Commuted Among Admissions to Death Row, 53 J. Crim.

L., Crim. & Pol. Sci. 301 (1962); Hartung, Trends in the

Use of Capital Punishment, 284 Annals 8, 14-17 (1952);

Weihofen, The Urge to Punish 164-165 (1956).

Second, Alabama Law has long accorded differential

treatment in sexual matters on the basis of race. The

Alabama Constitution prohibits the legislature from per

mitting interracial marriages. Ala. Const. § 102. Marriage,

adultery and fornication between Negroes and whites are

felonies and an officer issuing a license for an interracial

marriage commits a misdemeanor. Ala. Code Ann. Tit.

14, § 360-61. In addition, Alabama public policy still sup

ports segregation of the races and the statute books of

the state still carry provisions which enforce segregation.

See Ala. Code Ann. Tit. 48, §§ 186, 196, 464 (intrastate

buses); Tit. 46, §189 (hospitals); Tit. 45, § 248 (schools

for the mentally deficient); Tit. 51, §244 (poll books must

indicate race). See also Lee v. Macon County Board of

Education, 231 F. Supp. 743 (M. D. Ala. 1964); Carr v.

Montgomery County Board of Education, 232 F. Supp. 715

(M. D. Ala. 1964).

Third, the absolute discretion which Alabama law gives

jurors to decide between life and death, undirected by any

rational standards for making that decision, see part

11(B), infra, invites the influence of arbitrary and dis

criminatory considerations. This Court has long been con

cerned with a vagueness of criminal statutes which “ licenses

the jury to create its own standard in each case.” 18 Hern

don v. Lowry, 301 U. S. 242, 263 (1937), See, e.g., Smith,

v. Cahoon, 283 U. S. 553 (1931) ; Cline v. Frink Dairy Co.,

274 U. S. 445 (1927); Connolly v. General Construction Co.,

269 U. S. 385 (1926); Winters v. New York, 333 U. S. 507

(1948). The vice of such statutes is not alone their failure

to give fair warning of prohibited conduct, but the breadth

of room they leave for jury caprice and suasion by imper

missible considerations, N.A.A.C.P. v. Button, 371 U. S.

415, 432-433 (1963); Freedman v. Maryland, 380 U. S. 51,

56 (1965); Lewis, the Sit-In Cases: Great Expectations,

[1963] Supreme Court Review 101, 110; Note 109 U. Pa.

L. Rev. 67, 90 (1960), including racial considerations, see

Louisiana v. United States, 380 U. S. 145 (1965); Dom-

browski v. Pfister, 380 U. S. 479 (1965); Cox v. Louisiana,

379 U. S. 536 (1965). Unlimited sentencing discretion in

a capital jury presents this vice in the extreme. To para

phrase Burstyn v. Wilson, 343 U. S. 495, 505 (1952): “ Un

der such a standard the most careful and tolerant [lay

juror] . . . would find it virtually impossible to avoid

favoring one [race] . . . over another.”

1 etitioner requests the Court to grant certiorari, that

it may review and reverse the judgment of the Supreme

( ourt of Alabama which denies petitioner’s right to demon-

*S l lle Petition alleges deprivation of petitioner’s rights in that (a) his

sentence to death was determined by a jury which had unlimited, un

directed and unreviewable discretion in choice of sentence to impose any

penalty between a term of 10 years to death, (b) no rational, fair, or

uniform standards were set by the statute and the trial judge gave the

jury no directions as to choosing among allowable sentences permitting the

jury to consider discriminatory racial factors and (c) that the jury’s ver

dict simultaneously determined his guilt and fixed the sentence at death

( ep riving petitioner of the opportunity to present evidence in mitigation

without taking the stand in his own defense and forfeiting the privilege

of himself against self incrimination (4a-15a).

29

strate that he had been denied equal treatment in the most

grievous penalty known to law. He seeks only a fair oppor

tunity to demonstrate that his present incarceration under

sentence of death is the product of a long continued and

continuing system of discriminatory administration of jus

tice operating in every gap of discretion left by the state’s

written law to deny him equal treatment and subject him

to extreme punishment which in practice is virtually never

applied to the white man but is reserved as the ultimate

weapon of terror to hold the Negro in his place. Peti

tioner asks this Court to consider whether he has the right

to demonstrate discrimination because of the Fourteenth

Amendment’s overriding purpose to secure racial equality

and because “ racial classifications [are] ‘constitutionally

suspect’ . . . and subject to the ‘most rigid scrutiny.’ . . . ”

MacLaughlin v. Florida, 379 U. S. 184, 192 (1964).

B. The Court Should Grant Certiorari To Consider Peti

tioner’s Contention That His Sentence Is Unconstitutional

Under The Eighth And Fourteenth Amendments.

Petitioner alleged that he was unconstitutionally sen

tenced without consideration of aggravating or mitigating

circumstances, pursuant to Title 14, §395 of the Alabama

Code, which statute on its face and as applied prescribes

the imposition of cruel and unusual punishment in vio

lation of the Fourteenth Amendment (4a, 15a). This ques

tion, which three Justices of the Court thought deserving

of certiorari in Rudolph v. Alabama, 375 U. S. 889 (1963),

has been deemed by both the Fourth and Eighth circuits

as one which “must be for the Supreme Court in the first

instance.” Maxicell v. Stephens,------ F. 2 d ------ (8th Cir.

decided June 30, 1965) petition for certiorari pending, No.

429, October Term, 1965. The Fourth Circuit has taken

the same view. Ralph v. Pepersack, 335 F. 2d 128, 141

30

(4th Cir. 1964). Petitioner respectfully requests the judg

ment of the Court on the issue.

The question posed is not whether on any rational view

which one might take of the purpose of criminal punish

ment, the defendant’s conduct as the jury might have found

it at its worst could support a death sentence consistent

with civilized standards for the administration of criminal

law. For here the issue of penalty was submitted to the

jury in their unlimited discretion under Alabama pro

cedure. Their attention was directed to none of the pur

poses of criminal punishment, nor to any aspect or aspects

of the defendant’s conduct as they related to imposition

of sentence.

The charge of the trial judge to the jury which con

victed petitioner set forth the elements of the crime of rape

and the evidence which must be found to convict but as

to sentence merely stated:19

As I have told you, the punishment for the crime of

rape is either death or imprisonment in the peniten

tiary for not less than 10 years. The limit is on the

minimum sentence and not on the maximum.

The jury was not invited to consider the extent of physical

harm to the prosecutrix, the moral heinousness of the de

fendants’ acts, his susceptibility or lack of susceptibility

to reformation, the extent of the detrrent effect of killing

the defendant “ pour decourager les autres.” Cf. Packer,

Making the Punishment Fit the Crime, 77 Harv. L. Rev.

1071 (1964). They were permitted to choose between life

and death upon conviction for any reason, rational or ir-

i ational, or for no reason at a ll: at a whim, a vague

19 See p. 361 certified record on file with the Court in Swain v. Alabama,

380 IT. S. 202.

31

caprice, or because of the color of petitioner’s skin if that

did not please them. In making the determination to im

pose the death sentence, they acted wilfully and unreview-

ably, without standards and without direction. Nothing as

sured that there would he the slightest thread of connection

between the sentence they exacted and any reasonable jus

tification for exacting it. Cf. Skinner v. Oklahoma, 316

U. S. 535 (1942). A judgment so unconfined, so essentially

erratic, is per se cruel and unusual because it is purposeless,

lacking in any relationship by which its fitness to the of

fense, or to the offender or to any legitimate social pur

pose may be tested. It is cruel not only because it is

extreme but because it is wanton; and unusual not only

because it is rare, but because the decision to remove the

defendant from the ordinary penological regime is arbi

trary. To concede the complexity and interrelation of sen

tencing goals, see Packer, supra, is no reason to sustain

a statute which ignores them all. It is futile to put for

ward justifications for a death so inflicted; there is no

assurance that the infliction responds to the justification

or will conform to it in operation. Inevitably under such

a sentencing regime, capital punishment in those few, ar

bitrarily selected cases where it is applied both is “ ‘dis-

proportioned to the offenses charged’ ” and constitutes

“ ‘unnecessary cruelty.’ ” Rudolph v. Alabama, supra, 375

U. S. at 891.20

20 The United States Department of Justice has taken the following

position on continued imposition of the death penalty: “ We favor the

abolition of the death penalty. Modern penology with its correctional and

rehabilitation skills affords greater protection to society than the death

penalty which is inconsistent with its goals. This Nation is too great in

its resources and too good in its purposes to engage in the light of present

understanding in the deliberate taking of human life as either a punish

ment or a deterrent to domestic crime.” Letter of Deputy Attorney Gen

eral Ramsey Clark to the Honorable John L. McMillan, Chairman, District

o f Columbia Committee, House of Representatives, July 23, 1965, reported

in New York Times, July 24, 1965, p. 1, col. 5.

32

III.

Petitioner Was Denied Rights Under The Fifth And

Fourteenth Amendments When The Circuit Solicitor

Was Permitted To Comment On His Failure To Take

The Stand.

The constitutional privilege against self-incrimination,

which is available in state as well as federal proceedings,

Malloy v. Hogan, 378 U. S. 1, includes the right of a crim

inal defendant to be free from “ comment by the prosecu

tion on the accused’s silence or instructions by the court

that such silence is evidence of guilt.” Griffin v. California,

380 U. S. 609. In Griffin, the Court held that the standards

imposed upon federal courts and prosecutors by 18

lT. S. C. §3841, prohibiting such comment, reflect “ the

spirit of the Self-Incrimination Clause.” 380 U. S. at

613-614. In Wilson v. United States, 149 U. S. 60, 65 the

leading case under §3841, the Court stated: “ Comment,

especially hostile comment, upon such failure must neces

sarily be excluded from the jury. The minds of the jurors

can only remain unaffected from this circumstance by

excluding all reference to it.” Further, “ Counsel is for

bidden by the statute to make any comment which would

create or tend to create a presumption against the defen

dant for his failure to testify.” 149 U. S. at 67.

During his summation to the jury, the circuit solicitor

stated:

Gentlemen, do you think we have proved these three

elements? I submit to you it is not denied, there is

not a word come from this stand that denied the

charge of rape. Now the only question that the de

fendant has raised here by his attorneys is the ques

tion of identify [sic]. (Tr. 354; App. p. 7a.)21

Objection to these remarks was made by defendant’s counsel and

overruled. An exception was reserved (Tr. 355).

33

This was unfair comment on petitioner’s exercise of his

constitutional right to remain silent and rely on the pre

sumption of innocence. The Supreme Court of Alabama,

affirming the conviction, held that the solicitor’s remarks

did not violate Alabama’s statute forbidding comment,

Ala. Code, Tit. 15, §305, because they merely stated that

the evidence was uncontradicted or undenied. Swain v.

Alabama, 275 Ala. 508, 156 So. 2d 368, 378 (1963).22 How

ever, the solicitor did not merely state that evidence was

uncontradicted; he said that no word of denial had come

from the stand, in obvious reference to the defendant.

The comment alone is enough to invalidate petitioner’s

conviction under Griffin v. California, but it need not be

considered alone. Not content with allusion to petitioner’s

failure to testify, the solicitor proceeded to attack him as

a bootlegger without any justification in the record23 and

to arouse racial antagonism before the all-white jury. His

earthy description of the crime, with its patent racial

overtones,24 not only raises a question of elemental fair

22 Affirmance by the Supreme Court o f Alabama preceded this Court’s

decision in Malloy v. Hogan and Griffin v. California.

23 ‘‘Mr. Hollingsworth: Think what it has done to that child’s life.

When will she ever forget the day of February 7, 1962, when a bootlegger

was riding the road and decides he wants to stop and rape somebody in

that community right near the county line.

Mr. H all: I f your Honor please, we object to the use of the term ‘boot

legger’ . We don’t recall any testimony, any evidence coming from this

witness stand that this man was a bootlegger.

The Court: I ’ll sustain the objection and I ’ll instruct the jury not to

consider it.

Mr. Hall: We move for a mistrial, your Honor.

The Court: I ’ll overrule the motion for a mistrial.

Mr. Hall: We take exception.

Mr. Hollingsworth: The way I understand it, he said he was going to

get a load from Opelika” (Tr. 354).

24 “ Do you think this young lady, Jimmie Sue Butterworth, consented

to have this defendant have that rough and rugged intercourse where this

impact against her body caused loose hairs to come out of his privates?

You gentlemen know the way a colored person— you have seen them, you

34

ness of the trial, see, Viereck v. United States, 318 U. S.