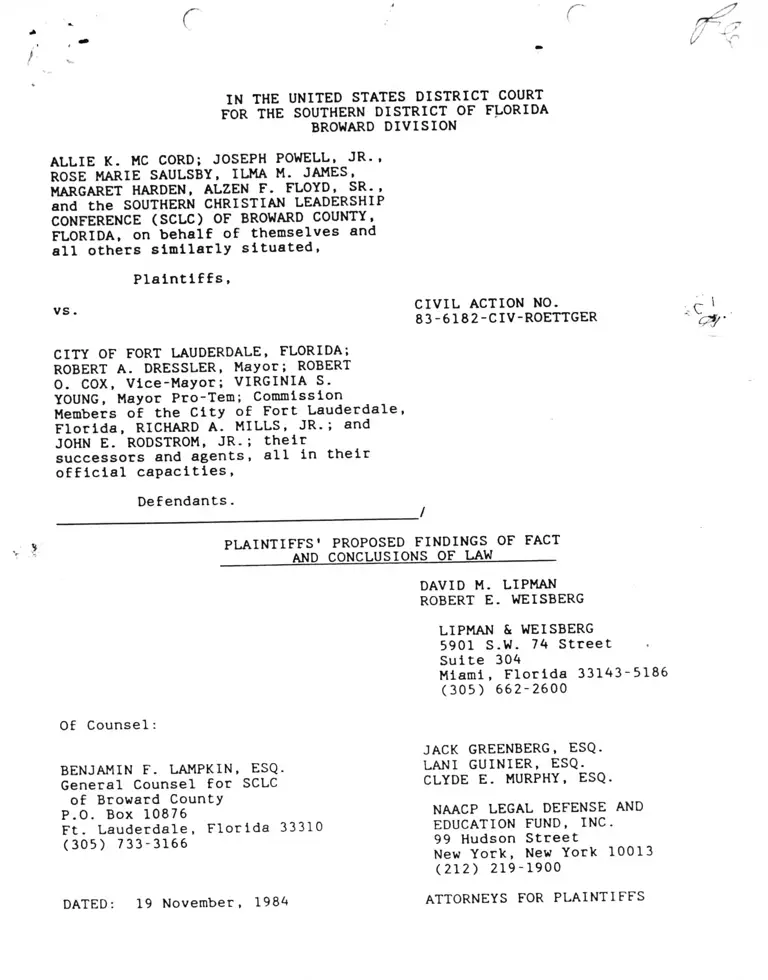

McCord v. City of Fort Lauderdale, Florida Plaintiffs Proposed Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law

Public Court Documents

November 19, 1984

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. McCord v. City of Fort Lauderdale, Florida Plaintiffs Proposed Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law, 1984. 45706778-bc9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/7449d3d0-4e03-43f7-bfe4-a842d1391404/mccord-v-city-of-fort-lauderdale-florida-plaintiffs-proposed-findings-of-fact-and-conclusions-of-law. Accessed February 17, 2026.

Copied!

r r

*

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF FLORIDA BROWARD DIVISION

ALLIE K. MC CORD; JOSEPH POWELL, JR.,

ROSE MARIE SAULSBY, ILMA M. JAMES,MARGARET HARDEN, ALZEN F. FLOYD, SR., and the SOUTHERN CHRISTIAN LEADERSHIP

CONFERENCE (SCLC) OF BROWARD COUNTY,

FLORIDA, on behalf of themselves and

all others similarly situated,

Plaintiffs,

CIVIL ACTION NO. 83-6182-CIV-ROETTGER

CITY OF FORT LAUDERDALE, FLORIDA;

ROBERT A. DRESSLER, Mayor; ROBERT

0. COX, Vice-Mayor; VIRGINIA S.

YOUNG, Mayor Pro-Tern; Commission Members of the City of Fort Lauderdale,

Florida, RICHARD A. MILLS, JR.; and

JOHN E. RODSTROM, JR.; their successors and agents, all in their

official capacities,

Defendants. /

PLAINTIFFS' PROPOSED FINDINGS OF FACT AND CONCLUSIONS OF LAW_______

DAVID M. LIPMAN

ROBERT E. WEISBERG

LIPMAN & WEISBERG

5901 S.W. 74 Street

Suite 304Miami, Florida 33143-5186

(305) 662-2600

Of Counsel:

BENJAMIN F. LAMPKIN, ESQ.

General Counsel for SCLC

of Broward County

P.O. Box 10876Ft. Lauderdale, Florida 33310

(305) 733-3166

JACK GREENBERG, ESQ.

LANI GUINIER, ESQ.

CLYDE E. MURPHY, ESQ.

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND

EDUCATION FUND, INC.

99 Hudson StreetNew York, New York 10013

(212) 219-1900

DATED: 19 November, 1984 ATTORNEYS FOR PLAINTIFFS

r r

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

I. FINDINGS OF FACT 1

A. PROCEDURAL BACKGROUND 1

B- GENERAL BACKGROUND 3

C. THE FACTS 3

1. HISTORY OF OFFICIAL RACIAL DISCRIMINATION 3

a. THE STATE OF FLORIDA 3

b. THE CITY OF FORT LAUDERDALE 4

(i) 1911 to 1940 4

(ii) 1940 to 1954 6

(iii) 1954 to the Present Era 9

2. LINGERING EFFECTS OF PAST DISCRIMINATION

AND CONTINUING PRESENT CONDITIONS 14

a. RESIDENTIAL SEGREGATION IS

b. MAINTENANCE OF CITY’S AT-LARGE

ELECTION SYSTEM 16

c. DISCRIMINATORY EMPLOYMENT PRACTICES 16

d. CITY ADVISORY BOARD AND COMMITTEE

APPOINTMENTS 18

(i) 1957-1983 19

(ii) 1984 - Boards and Committees 19

e. PUBLIC HOUSING 20

f. EDUCATION 21

3. PRESENT SOCIO-ECONOMIC STATUS OF BLACKS 22

4. RACIALLY POLARIZED VOTING - GENERAL FINDINGS 23

a. THE BI-VARIATE REGRESSION ANALYSIS 24

b. SUPPORT FOR WINNING CANDIDATES 26

-i-

c. SUPPORT FOR BLACK CANDIDATES

d. BLACKS IMPACT ON THE OUTCOME OF ELECTION

e. THE AVERAGE NUMBER OF VOTES CAST

BY THE VOTERS

f .

g-

THE MULTI-VARIATE ANALYSIS

THE BLACK CANDIDATES - 1957 to 1982

(i) 1957-1967

(ii) 1969-1971 - Alcee Hastings

(iii) 1973 - DeGraffenreidt

(iv) 1975-1977 - DeGraffenredit

(v) 1979 - DeGraffenredit

(vi) 1982

THE STRUCTURE OF THE ELECTION SYSTEM

a. LACK OF GEOGRAPHICAL SUBDISTRICTS

SIZE OF DISTRICT

THE EXTENT TO WHICH BLACKS HAVE BEEN ELECTED TO OFFICE

THE POLICY FOR USING THE AT-LARGE

ELECTION SYSTEM IS TENUOUS

8.

9 .

UNRESPONSIVENESS

BLACK ACCESS TO THE CANDIDATE

SLATING PROCESS

II. CONCLUSIONS OF LAW

A. OVERVIEW OF SECTION 2 STANDARDSB. APPLICATION OF TYPICAL FACTORS SHOWING

SECTION 2 VIOLATION

1. HISTORY OF OFFICIAL DISCRIMINATION

2. RACIALLY POLARIZED VOTING

3. THE STRUCTURE OF THE ELECTION SYSTEM

27

28

28

29

36

36

37

39

92

93

95

98

98

98

99

99

51

53

59

59

56

56

58

62

-ii-

( {

4. SLATING PROCESS 62

5. SOCIO-ECONOMIC FACTORS 62

6. OVERT AND SUBTLE RACIAL CAMPAIGNS 63

7. ELECTION OF BLACKS TO PUBLIC OFFICE 64

8. UNRESPONSIVENESS 65

9. TENUOUSNESS OF STATE POLICY 66

C. TOTALITY OF THE CIRCUMSTANCES 67

III. RELIEF 67

APPENDIX I 69a

CERTIFICATE <OF SERVICE * * * *

EXPLANATION OF ABBREVIATIONS

In order to facilitate reference to the Record in this

case, the Court has utilized the following abbreviations to the

trial transcript and parties' exhibits,

a. Trial Transcript

(Name of Witness), Vol. ____, Pg- ----

Reference is made to one of the 7

volumes of trial transcripts.

Note, all volumes are referred to

by their number except the

testimony of October 26, 1984

which is given a number Vol. 5A.

The name of the witness and page

number of the record volume is

identified.

- iii-

Exhibits

P. Ex.

D. Ex.

Referring to Plaintiffs' Exhibit

or Defendants' Exhibit with

numerical reference and page or

Table when necessary.

-iv-

r r

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF FLORIDA

BROWARD DIVISION

ALLIE K. MC CORD, et al.,

Plaintiffs,

CASE NO. 83-6182-CIV

ROETTGER

CITY OF FORT LAUDERDALE,

FLORIDA, et al.,

Defendants.

____/

PLAINTIFFS' PROPOSED FINDINGS OF FACT ________AND CONCLUSIONS OF LAW________

Aristotle has written:

If liberty and equality, as is thought by some, are chiefly to

be founded in democracy, they will be best attained when all

persons alike share in the government to the utmost.Aristotle, Politics, Book II

This case evokes consideration of the extent to which the Voting

Rights Act of 1965, as amended in 1982, 42 U.S.C §1973 compels adherence

to this principle in the context of Plaintiffs' challenge to the legality

of the at-large system of electing Fort Lauderdale City Commissioners.

The issue before this Court is whether Fort Lauderdale's at-large

election system results in blacks having "less opportunity" than whites

to "participate in the political process and to elect representatives of

their choice." (Id.)

I. FINDINGS OF FACT

A. PROCEDURAL BACKGROUND

1. Plaintiffs, six black citizens of Fort Lauderdale and the

Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) of Broward County,

Florida, filed this lawsuit on March 10, 1983, alleging that Fort

Lauderdale's election system unlawfully dilutes black voting strength in

violation of Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act.

Defendants are the City of Fort Lauderdale and Mayor, Vice-Mayor,

Mayor Pro-Tem, and two additional Commissioners, all sued in their

official capacity. 115, Complaint.

2. The case was certified as a class action on September 26, 1984,

pursuant to Rule 23(b)(2) F.R.C.P. Plaintiffs' class consists of "all

black citizens who reside in the City of Fort Lauderdale." (Vol. I, Pgs.

7-8.

3. Following extensive discovery by both parties, this case was

tried without jury commencing on September 26, 1984, and continued

intermittently over several weeks. Following the completion of the trial

on November 1, 1984, the parties filed extesnive post trial submissions

and the Court then entertained oral argument.

4. Having considered all of the evidence, the extensive post trial

submissions, and oral argument, the Court now, pursuant to Rule 52(a)

F.R.C.P., issues its Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law.1/

1/ This Court is mindful of the requirements of Rule 52(a) F.R.C.P., and

of the admonitions of binding precedent in our Circuit in Voting Rights

cases that "if the district court reaches a conclusion on one of the

Zimmer inquiries without discussing substantial relevant contrary evidence, the requirements of Rule 52 have not been met and a remand may

be called for if the court's conclusions on the other Zimmer inquiries

are not sufficient to support a judgment." Cross v. Baxter, 604 F.2d 875,

879 (5th Cir. 1979) ("Perhaps in no other area of the law is as much

specificity in researching and fact finding required . . "), vacated—on

other grounds, 704 F.2d 143 (5th Cir. 1983); Velasquez v. City of

Abllene, Texas, 725 F.2d 1017, 1020-21 (5th Cir. 1984).

This Court thus will carefully review the record evidence in this

case with transcript and exhibit citations, the applicable legal

authority, and the vying conclusions and inferences which the parties ask

to be drawn.

-2-

r

B. GENERAL BACKGROUND

5. Fort Lauderdale was incorporated in 1911 (P. Ex. 2). According

to the 1980 Census, its population totals 153,279 persons, of whom 21X or

32,225 are black (P. Ex. 15, Tab 1).

6. Linder Fort Lauderdale's election system, city commissioners run

in a primary and then general election. The ten candidates who obtain

the highest number of votes in the primary can run in the general elec

tion; and the five (5) candidates who receive the highest number of votes

in the general election become city commissioners. Each voter may vote

for up to 5 candidates in both elections (p. Ex. 2, Fact 12). All commis

sioners run at-large with no subdistrict residency requirement (P. Ex. 2).

C. THE FACTS

1. HISTORY OF OFFICIAL RACIAL DISCRIMINATION

a. THE STATE OF FLORIDA

7. Numerous judicial decisions have recounted Florida's long

history of discriminating against black citizens by depriving them

participation in the political process.2/ Dr. Jerrell Shofner,

Chairman of the History Department of the University of Central Florida,

testified that although the Civil War had ended slavery by law, the ideas

which produced slavery continued. (Shofner, Vol. Ill, Pg- 914).

e,g,, McGill v. Gadsden County2/ See , ~ ̂ , ----- -----------------(5th Cir. 1976) (widespread disenfranchisement

1900 ' s) ; McMillan v. Escambia County, Florida

Commission, 535 F.2d 277, of blacks by early

638 F.2d 1239, 1244

279

(5th

Cir. 1981) (Escambia I) (By early 1900's "the white citizens of Florida

had adopted various legislative plans either denying blacks the vote entirely or making their vote meaningless"); NAACP by Campbell v Gadsden

County. 691 F.2d 978, 982 (11th Cir. 1982) ("From 1901 through 1945,the contrivance of the all-white primary in Florida effectively denied blacks

access to the only election that had substantial meaning ).

-3-

( r

8. By the early 1900's, through a series of actions: (i) poll tax

requirements (Shofner, Vol. Ill, Pg. 420); (ii) the "Eight Ballot Box

Law," designed to prohibit blacks from voting (Shofner, Vol. Ill, Pg.

421); (iii) economic and violent intimidation against blacks (Shofner,

Vol. Ill, Pg. 420); (iv) the creation of the all-white Democratic Party

primary (Shofner, Vol. Ill, Pg. 424); and (v) the enactment of a series

of Jim Crow laws to perpetuate "a system of legal segregation to

reinforce the customary segregation that already had been in place"

(Shofner, Vol. Ill, Pgs. 421-422), blacks were disenfranchised from

participating in the electoral process throughout Florida.

b. THE CITY OF FORT LAUDERDALE

(i) 1911 to 1940

9. In 1911 the City of Fort Lauderdale incorporated. (Shofner, Vol.

Ill, Pg. 426). The City's initial charter required that poll taxes must

have been paid for the two years prior to initial City elections in order

to qualify for voting. (P. Ex. 2, Fact 7). Poll taxes remained a

requirement for voting in subsequent City elections through the 1930's.

(P. Ex. 14A, October 19, 1935).

10. By the end of World War I, Fort Lauderdale had become a segre

gated town by law. (Shofner, Vol. Ill, Pg.430). A 1922, City Ordinance

No. 140 had created a legal "color line" by segregating blacks into the

northwest area of the City, west of the railroad tracks. Any violation

of this Ordinance, which was passed with the expressed "purpose of promo

ting the general welfare of the City" was punishable by both imprisonment

and fine. (P. Ex. 6, Tab A), (Shofner, Vol. Ill, Pg. 430-431). This law

remained in effect for 25 years. (Shofner, Vol. Ill, Pg. 432).

-4-

r

11. The City's de lure segregation was refined in 1926, by Ordinance

No. 407, which divided the City into five residential districts designat

ed A-E (P. Ex. 3, Fact 8; Ex. 6, Tab C), and provided that "except in

Residence 'E' district designated by law as the 'Negro District' no resi

dence or apartment house could be used to house Negro families with the

exception of 'servants quarters.'" (P. Ex. 6, Tab C).

12. Fort Lauderdale's segregation laws were enforced. In 1929, when

306 white people requested the "immediate removal of a colony of blacks"

residing outside their legally defined borders, the City Commission ad

vised the City Manager to take steps to have the "Negroes removed from

their present location" (P. Ex. 3, Fact 18).

13. During the 1920's, Fort Lauderdale’s white citizens actively

sought to deny blacks equal societal participation (Shofner, Vol. Ill,

Pg. 421). For example, on a Thanksgiving Day afternoon in 1926, a

thousand members of the Ku Klux Klan, an organization very active

throughout the south, paraded through the City of Fort Lauderdale and

burnt crosses in Stranahan Park while several thousand spectators looked

on. (P. Ex. 14B, November 26, 1926).

14. In the 1930's the City continued to refine and enforce its

segregation laws. In 1936, the commission replaced segregation Ordinance

No. 407 with Ordinance No. 820. (P. Ex. 3, Fact 26), which redefined the

boundaries of the "Negro District" (Residence E district) (P. Ex. 3, Fact

26). These adjusted boundaries literally wedged all Fort Lauderdale

blacks into an area between the tracks of the Florida East Coast and Sea

board Railroads in the northwest section of the City. (P. Ex. 6, Tab E).

15. In 1939, based on a Planning and Zoning Commission recommenda

tion to increase the size of the "Negro District," the segregation law

-5-

( (

i

was amended again (Ord. No. 983) "to permanently enlarge [the] boundaries

of Negro District, Section E" (P. Ex. 3, Fact 34). However, Just five

months later, in response to over 500 white property owners who protested

"against the encroachment of Negroes" caused by the expansion, Ordinance

No. 983 was repealed and Ordinance No. 1005 restored the Negro District

to its earlier boundaries. (P. Ex. 3, Fact 39).

As the negro population grew, the City continued to enforce

aggressively its segregation laws. (P. Ex. 3, Fact 34). In 1939 the

Mayor took action to "get rid of the Negroes [outside their] section."

(P. Ex. 5, Fact 37).

16. By the 1930's, blacks were isolated from the mainstream.

(Shofner, Vol. Ill, Pg. 434). Blacks had their own medical and health

facilities (P. Ex. 3, Facts 25, 28, 32); could not use City recreational

facilities (colored ball team prohibited from using municipal park,

blacks denied use of beaches), (P. Ex. 3, Facts 14 and 23); and were

denied improvements in the "Negro District" (requests on improved

services and enforcement of sanitary code denied) (P. Ex. 3, Fact 36 and

Pg. 11B-D attached to Fact 31).)

(ii). 1940-1954

17. The City's vigorous efforts to segregate blacks by law continued

in the 1940's. In 1941, two further ordinances had redefined the "Negro

District" (P. Ex. 3, Fact 45) (Ord. No. C-48); (P. Ex. 3, Fact 46), (Ord.

No. C- 51) .

18. In April, 1942, the City's Planning and Zoning Advisory Board

recommended that the City acquire land for a buffer area to create a

district dividing line between the white and colored area which if

possible could "eventually create a buffer entirely surrounding the

colored area" (P. Ex. 3, Fact 48). The City Commission recognized that

-6 -

r r

the "buffer zone is very important in solving the problems permanently"

(P. Ex. 3, Fact 51). (Shofner, Vol. Ill, Pg. 432).

19. World War II altered race relations within the City of Fort

auderdale (Shofner, Vol. Ill, Pgs. 435-436). During the war, Fort

Lauderdale blacks were viewed as a source of labor for local farms. The

Dillard School would be closed periodically so black children could work

in the vegetable fields. (Shofner, Vol. Ill, Pg- 455). Also, black men

were picked up arbitrarily by the Broward County Sheriff to do field

labor work. (Shofner, Vol. Ill, Pgs. 437-438).

20. At the end of World War II, blacks in Fort Lauderdale began to

press for equal governmental services, benefits, and employment.

(Shofner, Vol. Ill, Pg. 439) In 1945, blacks requested judicial relief,

challenging the school system's practice of closing the black Dillard

School during harvest season. Clarence C. Walker Civic League v. Board

of Public Instruction of Broward County, 154 F.2d 726 (5th Cir. 1946). In

January, 1946, Dr. Mizell, representing the Negro Businessman's

Improvement Association, asked the Commission to build a Negro park, but

was unsuccessful (P. Ex. 3, Fact 55). In April, 1946, the Negro Business

and Professional Men's League petitioned the Commission to hire Negro

patrolmen for the black community (P. Ex. 3, Fact 56). Two months later,

the Negro Ministerial Alliance made the same request (P. Ex. 3, Fact

58). The City refused. (P. Ex. 3, Fact 61).

21. The segregation ordinance (then Chapter 198 of the City's Code

of Ordinances) was not repealed until 1948 when the City finally

recognized its questionable constitutionality. (P. Ex. 3, Fact 62); (P.

Ex. 14B, March 17, 1947).

22. By 1947, the fact that blacks had constitutional rights to

participate in the electoral process was becoming evident. The United

7 -

r r

States Supreme Court had ruled in 1944 that the Texas White primary was

unconstitutional. Smith v. Allrlght. 321 U.S. 649 (1944), and in 1945,

the Florida Supreme Court had struck down the white primary. Davis v.

State ex rel. Cromwell. 156 Fla. 181, 23 So.2d 85 (1945) (en banc).

23. From 1929 to 1947, pursuant to a 1929 City Charter amendment,

four of the five City Commissioners were required to be residents of the

districts they represented (P. Ex. 2, Fact 10). This residency

requirement was eliminated in the 1947 Charter which provided for the

five Commissioners to be elected at large (P. Ex. 2, Fact 10).

24. On March 3, 1947, the Commission discussed holding a special

election to ascertain the desires of the electorate relative to

establishing five (5) commission districts in the City. (P. Ex. 3, Fact

65) .

25. On March 11, 1947, the Commission considered a proposed election

plan in which three of the five districts would each include "one-third

of the zoned residence 'E'area Negro District." After being advised that

a legal district could be based on population only, and that the "Negro

District" could not legally be divided into three districts, the

Commission withdrew the proposal for five commission districts from the

ballot. (P. Ex. 3, Fact 67).

26. Dr. Shofner concluded that the decision to eliminate the

residency district requirement in March, 1947, was taken to "keep blacks

off the City Commission" (Shofner, Vol. Ill, Pg. 455). This Court agrees

with Dr. Shofner's conclusion. First. by 1947, blacks had begun to

assert their political rights. In fact, on March 10th, the day before

the Commission’s decision to remove the district election question from

the ballot, the Commission had received a petition with several hundred

-8-

r

names which requested that a negro policeman be hired. (P. Ex. 3, Fact

66). Second, the City had recognized the questionable constitutionality

of de lure segregation, supra. 111121-23. Third, the decision by the City

of Fort Lauderdale to change its election system emulated the Florida

legislature, when in 1947, it changed the method of school board

elections from a district primary system to an at-large primary system

after the white primary had been declared illegal. See, NAACP by

Campbell v. Gadsden County School Board. 691 F.2d 978, 982 (11th Cir.

1982) (holding that the 1947 change to at-large school board elections

was racially motivated); McMillan v. Escambia County, 638 F.2d 1239,

1245-46 (5th Cir. 1981) (Escambia I) (same). Fourth, the explicit

language contained in the City Commission minutes reflects a conscious

intent to dilute black voting strength. (P. Ex. 3, Fact 67).

27. Throughout the 1940's, black citizens and organizations

unsuccessfully requested that a black be appointed to the City s police

department (P. Ex. 3, Facts 56, 58, 60, 61. 63, 66, 69), (Shofner, Vol.

Ill, Pgs. 442-444). It was not until September, 1952 that the City hired

its first black police officer. (P. Ex. 14B, September 4, 1952),

(Shofner, Vol. Ill, Pg. 442).

28. Black citizens continued to be isolated and their needs

rejected. In 1951, the County Health Director blamed the City for the

slum conditions in the Negro section, as the City had failed to enforce

its laws. The County Health Director noted a high incidence of

tuberculosis in the black section due to over-crowding and poor sanitary

conditions (P. Ex. 14B, September 11, 1951).

(iii). 1954 to the Present Era

29. The 1954 United States Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board

of Education, and its implementing decision in 1955 were cataclysmic

-9-

c

events within the South. (Shofner, Vol. Ill, Pg. 456). In Florida, a

committee established by the State Attorney General Richard Ervin

suggested that implementing the Brown decision would lead to widespread

violence in Florida. (Shofner, Vol. Ill, Pg. 457) The Fort Lauderdale

News criticized the Brown decision and predicted problems for the local

tourist industry if public facilities were forced to desegregate. (P. Ex.

14B, May 25, 1954).

30. On November 19, 1955, the City formally responded to judicial

decisions that mandated integration. Through Ordinance No. 61-55, the

City recognized the similarity of race relations in Fort Lauderdale to

that throughout the South and declared that any desegregation of

municipal facilities would not be taken voluntarily. (P. Ex. 6, Tab 5,

Ord. 61-55).

31. As part of the Ordinance, the City outlined its Policy setting

forth various facts which recognized that: (a) Fort Lauderdale's racial

pattern is a part of a larger pattern which has prevailed in much of the

United States for generations; (b) many Fort Lauderdale citizens do not

have a liberal view on segregation; (c) the City Commission did not seek

responsibility to desegregate facilities, but viewed it as a burden and

duty; (d) for the time being, the use of municipal facilities should be

maintained in the status quo (P. Ex. 6, Tab 5, Ord. No. 61-55, Section 1).

32. Throughout the 1950's and 1960's, blacks in Fort Lauderdale

continued to press for equal access to municipal facilities, and equal

employment opportunities. In September, 1955, 122 Negros presented the

Commission with a petition requesting the use of the City golf course (P.

Ex. 3, Fact 85). Two months later, the Commission decided the course

should remain segregated (P. Ex. 3, Fact 86) and appointed a committee to

review future action (P. Ex. 3, Fact 87). In January, 1956, the

-10-

r r

Northwest Golfers Association, a Negro organization, again requested to

use the course. (P. Ex. 3, Fact 89). In March, 1956, the City’s

/continual refusal to allow Negroes the use of the golf course (P. Ex. 3,

Fact 91) was approved by white citizens' organizations. (P. Ex. 14B,

March 20, 1956). In order to avoid integration, the City considered

possible options such as selling the golf course or creating a private

corporation to run it (P. Ex. 3, Fact 92). In January, 1957, the City

Commission rated the continued racially segregated operation of the

City's golf course and Country Club as a "highlight" of the Commission's

1955-56 fiscal year's accomplishments. (P. Ex. 14B, January 20, 1957).

33. On February 21, 1957, United States District Judge Emett C.

Choate ruled that the City's refusal to allow blacks' use of public

facilities violated the Fourteenth Amendment and enjoined the City's

segregation policy. Moorehead v. City of Fort Lauderdale, 152 F. Supp.

131 (S.D. Fla. 1957), aff'd per curiam. 248 F.2d 544 (5th Cir. 1957).

Immediately following the Court order, the City took steps to sell the

golf course (P. Ex. 3, Fact 94), and in October, 1957, its sale was

finalized. (P. Ex. 3, Fact 95).

34. Blacks had tried to gain access to the City's beaches since the

1920's, but repeated requests, spanning four decades, had been ignored.

Thus, in the late 1950's and early 1960's, blacks accelerated their

3 /efforts.

3/ In 1926, a delegation of Negro citizens requested a district for

ocean beach use. This request referred to City Manager (P. Ex. 3, Fact

9). In 1927, Negroes' use of the beach north of Las Olas Boulevard was

cited as a major problem by City Manager. (P. Ex. 14B, August 17, 1927).

In 1930, the Commission ordered the Police Chief to regulate Negro bathing

within city limits (P. Ex. 3, Fact 20). In 1932, the Commission warned

of the growing Negro menace on our beaches (P. Ex. 14B, July 12, 1932).

(Footnote continued to next page)

-11 -

r r

35. In 195**, the Fort Lauderdale News reported that Fort Lauderdale

was years behind other Florida communities in providing Negro citizens

with beach facilities and that Fort Lauderdale was an isolated trouble

spot:

Throughout the entire state, the Associated Press found

there was little or no agitation for admittance of Negroes

to white beaches. Said the AP: "The only potential

trouble spot at the moment appears to be the Fort Lauderdale area." (emphasis added) (P. Ex. 1**B, June 20,

195**)

36. In 1961, the Broward County Commission discussed the possibility

of a Negro beach (P. Ex. 1**B, December 6, 1961), while blacks in Fort

Lauderdale and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored

People (NAACP) contemplated litigation to integrate the City's beaches

(P. Ex. 1AB, August 6, 1961). Through the mid 1960's, the City beaches

remained segregated. (P. Ex. 3, Fact 11**).

37. Although in 1952 black citizens had persuaded the City to employ

black patrolmen, the City had not altered its discriminatory practices.

In 1959, the black community complained to the Commission about the

absence of Negroes on the police force (P. Ex. 3, Fact 99). In 1963, the

Bi-Racial Advisory Board requested that a "reasonable number" of Negroes

be hired as policemen (P. Ex. 3, Fact 116).

(Footnote continued from previous page)

In 19**6 the Colored Business and Professional Men's League again

requested a Negro beach. (P. Ex. 3, Fact 59). In 1952, the Commission

acknowledged Negroes interested in obtaining a beach (P. Ex. 3, tact /y;

In 1953, Negro community spokesman Dr. Mizell asked the City to provide

beach for its Negro citizens (P. Ex. 3, Fact 81) anywhere in the county long as it is centrally located and accessible (P. Ex. 1**B, February 9, 195*+). In 1956, Fort Lauderdale's Mayor expressed concern that opening

beaches to Negroes would be disastrous (P. Ex. 1**B, December 20, 19 ).

a

as

-12-

r r

38. During the 1960's, blacks repeatedly asked the city commission

to seek federal urban renewal funds to improve slum conditions within the

City (P. Ex. 3, Facts 125, 126). However, while the City objected to

obtaining federal funds for improvements in the black community, it

actively sought federal funds for improvements for white citizens. (P.

Ex. 3, Fact 109). In 1967, the NAACP initiated litigation to compel to

the City to obtain federal urban renewal funds for black areas also (P.

Ex. 14B, March 31, 1967).

39. In 1957, for the first time in the City's history, a Negro,

Nathaniel WilKerson, ran for the City Commission (P. Ex. 14a , March 4,

1957). Although unsuccessful, the Fort Lauderdale News deemed Mr.

Wilkerson's effort as a ’’commendable showing” in which "(h)e [Wilkerson]

polled 1,644 votes in the three Negro precincts and added 1,349 more in

city-wide balloting." (P. Ex. 14A, April 29, 1959). In 1963, the second

black candidate to make it to the runoff, Thomas Reddick, likewise polled

heavily in the Negro precincts. (P. Ex. 14A, April 10, 1963).

40. During the 1960's and 1970's, although cognizant of its adverse

effect on blacks' participation in the election system, the City retained

its at-large election system. In 1961, the Commission discussed, but

never acted upon, City Charter revisions to change the election system.

(P. Ex. 3, Fact 106; P. Ex. 10, Fact 6).

41. At a February 1973 Charter Revision Board meeting, Thomas

Reddick, the second black to have sought a City Commission position

recommended that "there be further discussion concerning Commissioners

running from districts rather than from the City at-large." (P. Ex. 10,

Fact 7, Minute Attachments, pg. 2).

42. In April, 1975, at a joint meeting with the City Commission and

the Charter Revision Board, the only black ever elected to the Fort

-13-

r c

Lauderdale City Commission, Andrew DeGraffenreidt, advocated districting

for city elections. (P. Ex. 10, Fact 10). Mr. DeGraffenreidt testified

that through his support for residency district requirements, he was

trying to condition the Commission to "the idea of [single] districting."

(DeGraffenreidt, Vol. I, Pg. 83).

2. LINGERING EFFECTS OF PAST DISCRIMINATION AND PRESENT CONDITIONS

43. The lingering effects of past discrimination against blacks in

Fort Lauderdale impairs their present-day ability to participate on an

equal footing in the political process and has "left blacks out of the

mainstream of the political process." (Shofner, Vol. Ill, Pgs. 463-464).

44. Dr. Shofner concluded that the progress blacks have been able to

achieve in Fort Lauderdale has been through litigation and the threats of

lawsuits. (Shofner, Vol. Ill, Pg. 463). Dr. Shofner further described

how two and a half decades of legal segregation has left blacks out of

the mainstream of the political process, evidenced by the City's failure

to employ black police officers; failure to provide blacks recreational

facilities unless compelled; and failure to modify its election system.

Significantly, the fact that the City is still segregated contributes to

the isolation of blacks from the political process. (Shofner, Vol. Ill,

Pgs. 463-464).

45. The effects of historical discrimination that presently linger

in the City include: (1) rigid residential segregation; (2) maintenance

of the City's at-large electoral system; (3) public discriminatory

employment practices; (4) lack of black appointments to City advisory

boards and committees; (5) discrimination in public housing; (6) a

racially isolated and segregated educational system; and (7) a depressed

socio-economic status of black citizens.

-14-

a. RESIDENTIAL SEGREGATION

46. Although residential segregation laws were repealed in 1948,

4 /their Impact on residential patterns have endured . (Shofner, Vol.

Ill, Pg. 464), (Dunn, Vol. IV, Pgs. 127-28). This Court has reviewed a

City map which demonstrates the present pattern of racial segregation.

(P. Ex. 29). (An exact duplicate of Exhibit 29 is attached hereto as Ap

pendix 1). It depicts the legal boundaries of the 1941 "negro district"

with 1980 census tract data showing a high concentration of black resi

dents. This color coded map illustrated that blacks concentrated in the

nqrthwest quadrajxt-^f— present approximately 87.21 of all black

IussidenX£-4n_the City. This concentration is literally within, ad joining

or adjacent to the boundaries of the 1941 legally defined "negro dis

trict." (See, P. Ex. 29).

47. Dr. Marvin Dunn, Community Psychologist and Professor at Florida

International University, stated, and the Court finds, that racially op

pressive laws, such as those used in Fort Lauderdale to segregate blacks,

would continue to have the effect of segregation after the legal barrier

had been removed. (Dunn, Vol. IV, Pgs. 127-129). Dr. Dunn also testified

that isolation by law over a long period of time creates a "psychological

ghettoization" which fosters a sense of "powerlessness, isolation and

alienation" (Dunn, Vol. IV, Pgs. 133-136) and limits "political

4/ Significantly, the lingering impact of the de jure residential segre

gation in the City does not stem from one isolated unreinforced hidden

ordinance. The City's legal efforts to segregate blacks began in 1922

(P. Ex. 6, Tab A, Ord. No. 140) continued in 1926 (P. Ex. 3, Fact 4, Ord.

No. 407); were publicly enforced in 1929 (P. Ex. 3, Fact 18); redefined

in 1936 (P. Ex. 3, Fact 76, Ord. No. 820); redefined in 1939 (P. Ex. 3, Fact 34, Ord. No. 983); redefined again in 1939 (Ord. No. 1005); publicly

enforced in 1939 (Plf. Ex. 3, Facts 34, 37); reinforced and redefined

with two ordinances in 1941 (P. Ex. 3, Facts 45 and 46, Ord. Nos. C-48

and C-51). In 1942 the City attempted to create a permanent buffer zone

to surround the black community. (P. Ex. 3, Facts 48, 51).

-15-

participation.” (Dunn, Vol. IV, Pg. 140).

b. MAINTENANCE OF CITY'S AT-LARGE ELECTION SYSTEM

48. Since 1957, when the first black candidate ran for the City

Commission, it has been obvious that black voters in this highly

segregated City provide overwhelming support for black candidates, infra,

111185-86). However, the City's at-large election system, coupled with

highly polarized racial bloc voting, has posed a severe obstacle to the

election of blacks. Despite the obvious problems the at-large election

system presents to black candidates, the system has been maintained. (P.

Ex. 12, Fact 10; P. Ex. 10, Facts 6-11).

49. The districting issue was raised squarely by a former

unsuccessful black candidate, now Judge Thomas Reddick, in 1973, during

Charter Revision meetings, supra, 1141. Two years later, the only black

ever elected to the City Commission, Andrew DeGraffenreidt, raised the

same issue, supra, 1142. Significantly, the City's present Mayor, RobertV

Dressier, candidly acknowledged the adverse impact of the City s at large

election system and that a district election system would result in a

black being elected to the Commission. (Dressier, Vol. V, Pg. 294).

.

C. DISCRIMINATORY EMPLOYMENT PRACTICES

50. On June 16, 1980, the United States government initiated a

lawsuit against the City of Fort Lauderdale challenging employment

practices within its Police and Fire Departments as racially

discriminatory. United States v. City of Fort Lauderdale, et al., Civ

No. 80-6289-CIV-ALH (S.D. 1980). (P. Ex. 23). The Federal District

Court, upon entry of a Consent Decree, required the City to (a) implement

a program to recruit qualified black applicants; and (b) adopt a goal to

employ, assign and promote blacks in sufficient numbers to eliminate

possible discrimination. (P. Ex. 23, Pgs. 2-3).

-16-

r f

51. when United States v. City of Fort Lauderdale was filed, there

were only six black police officers out of a sworn police force of

approximately 400 (Mills. Vol. VI. Pgs. 606-611). Not one black served

as a sergeant, lieutenant, captain, major, deputy chief, or chief.

(Mills, Vol. VI, Pg. 610).

52. Similarly, in the City's Fire Department, there were two black

firemen out of approximately 268 positions. (Mills. Vol. VI, Pgs. 606,

610). No blacks were employed at the higher level positions which

included approximately 80 driver engineers, 71 lieutenants, 15

commanders, one fire marshall, five batallion chiefs, one assistant

chief, one deputy chief, and a chief. (Mills, Vol. VI, Pg. 612).

53. The 1980 Order means that essentially one-half of the City s

entire work force is under a court decree to eliminate racial

discrimination. (P. Ex. 23, p. 7), (Mills, Vol. VI, Pg. 607).

54. A review of the City's work force as of June 30, 1983, based on

EEO-4 Reports submitted by the City to the federal government (P. Ex. 20,

Tabs 9-13) shows that blacks are clustered in lower paid, blue

collar-type positions.

55. Of the City's 353 black workers, 210 or 49.2% are classified as

Service Maintenance employees (P. Ex. 20, Table 13). Similarly, 193

black workers, or 54.6% of the City's 353 employees are concentrated in

two of the City's ten designated departments - Sanitation and Sewage and

Parks and Recreation. (P. Ex. 20, Table 12).

56. Blacks comprise less than 1% of the City’s work force that earns

in excess of $33,000.00 annually, less than 2% that earns between

$25,000.00 and $33,000.00 per year, and approximately 7% that earn

between $20,000.00 and $25,000.00 per year. This is contrasted by the

Fact that blacks comprise nearly 36% of the City's work force earning

-17-

between $10,000.00 and $13,000.00 per year, and 29X earn between

$13,000.00 and $16,000.00 per year. (P. Ex. 20, Table 11).

57. Bruce Larkin, Deputy Personnel Director for the City of Fort

Lauderdale, testified that racial disparities evident in the City's work

force are "reflective of perhaps hiring practices that went on many years

ago" prior to the application of the Civil Rights Act to state and local

governments." (Larkin, Vol. VI, Pgs. 698-699).

58. This Court agrees with Mr. Larkin's testimony that the fact that

black employees are concentrated in two City departments and

disproportionately occupy the lower paying positions can be traced in

part to the City's historical discrimination against blacks. The

relationship between past historical discrimination and the present

employment patterns is most dramatically apparent in the fact that

despite a 40 year effort by blacks to gain access to positions in the

Police Department, it took a lawsuit in 1980 to achieve that result. (P.

Ex. 23).

d. CITY ADVISORY BOARD AND COMMITTEE APPOINTMENTS

59. Historically and at present, blacks in Fort Lauderdale have been

denied appointments to the City's various citizen advisory boards and

committees. (P. Ex. 4 and 11).

60. Fort Lauderdale Mayor Robert Dressier testified to the very

important function of citizen advisory boards and committees in the

City's political process. (Dressier, Vol. V, Pg. 274). Dr. James Button,

Professor of Political Science from the University of Florida, stated

that board and committee appointments are important to black citizens for

two reasons. First, board appointments provide blacks with input into

Second, they serve "as a means by which thepolicy making areas.

J (

citizens are educated into the political process, how it works and how it

can be effective." (Button, Vol. IV, Pg. 202).

61. Plaintiffs submitted evidence, which the Court will now review,

listing all appointments to boards and committees of Fort Lauderdale from

January 1, 1957, and identifying each member's race. (P. Ex. 9 and 11).

(i) 1957-1983

62. From May, 1957 through June, 1983, there have been 66 different

City citizen advisory boards or committees in existence. (P. Ex. 9) On

90 of these boards and committees, no black had ever been appointed

during this 16-year period. On 13 of these committees there had been

only one black appointed during this period. Of the remaining 11 boards

and committees to which more than one black had been appointed during

this 16 year period, 7 of these Boards were created to address racial

issues or needs isolated to the black community.5/ The number of

individuals on these boards totaled 1,929, of which only 129, or 7.5T>

were black. (P. Ex. 9, Facts 1-67).

(ii) 1989-Boards and Committees

63. At the time of trial, as of October, 1989, there were 29 City

advisory boards and committees. (P. Ex. 11, Facts 1-29). There were no

black members on 13 of these boards. There were 237 members on these

5/ Boards and Committees which were created to address racial issues and

needs isolated to the black community were: 1) Bi-Racial Committee (P.Ex. 9, Fact 7); 2) Bi-Racial Advisory Board - Community Relations Board

(P. Ex. 9, Fact 8); 3) Community Relations Board (P. Ex. 9, Fact 9); 9)

Citizens' Advisory Committee (P. Ex. 9, Fact 20); 5) Sub-Library Board

(P. Ex. 9, Fact 99); 6) Negro Cemetary Committee (P. Ex. 9, Fact 50); 7)

Sunset Memorial Advisory Board (P. Ex. 9, Fact 61).

-19-

24 boards and committees, (P. Ex. 11), of which 18, or 7.6X were black.

(P. Ex. 11). Additionally, of the 18 black members, 5 serve on the

Community Services Board, which by ordinance requires appointment of

members from the northwest quadrant and blighted areas of the City. (P.

Ex. 11, Fact 12). Accordingly, of the remaining 23 boards and commit

tees, blacks comprise 13 of the total 221 members, or 5.9X. (P. Ex. 11).

64. A significant number of blacks were appointed to boards and

committees during the 6 year period that Andrew DeGraffenreidt

(1973-1979) had served on the City Commission. (DeGraffenreidt, Vol. I

Pg. 119). DeGraffenreidt cited his role, as one of his outstanding

achievements, in placing many blacks on various boards and committees as

a way of helping blacks "participate in the decision-making process in

the City of Fort Lauderdale after [his] tenure in office." He hoped it

might lead to a black board member becoming a City Commission member.

(DeGraffenreidt, Vol. I, Pg. 103). DeGraffenreidt said he had no trouble

locating interested, qualified black citizens for membership positions.

(DeGraffenreidt, Vol. I, Pg. 104).

e. PUBLIC HOUSING

65. The Housing Authority of the City of Fort Lauderdale operates

public housing within Fort Lauderdale. (Dressier, Vol. V, Pgs. 264-5).

The City Commission appoints the Authority's members and has certain

influence over the Authority, including its budgetary functions.

(Dressier, Vol. V, Pg. 266).

66. Public housing in Fort Lauderdale is segregated. The Fort

Lauderdale Housing Authority operates nine housing projects (P. Ex. 7.

Of these 9 housing projects, 6 are racially segregated. (P. Ex. 7).

-20-

r

F. EDUCATION

67. Dr. Gordon Foster, Professor of Education at the University of

Miami and Director of its School Desegregation Assistance Center for

Race, and one of the nation's leading desegregation experts, (Foster,

Vol. V-A, Pgs. 478-491), (P. Ex. 16), has served as a consultant to the

Broward County School Board since 1967, stemming from the Board's initial

desegregation efforts. (Foster, Vol. V-A, Pgs. 491-493). Drawing upon

that experience, as well as his desegregation background with virtually

every school board in the State of Florida, (Foster, Vol. V-A, Pg. 481),

Foster conducted a study to determine the: (i) extent of present

isolation and segregation of black students attending schools located in

or serving Fort Lauderdale; and (ii) how those conditions effect blacks'

ability to participate in the political process.

68. The Court finds, based upon Dr. Foster's study, that in the

schools located in or serving Fort Lauderdale: (1)(A) The number of black

students attending racially identifiable or segregated schools has almost

doubled since 1971, the year that the initial desegregation plan was

implemented through Court Order by the Fifth Circuit in Allen v. Board of

Public Instruction of Broward, 432 F.2d 362 (5th Cir. 1970), cert.

denied, 402 U.S. 952 (1971 ) to 1983. Four out of five (801.) black

students attend racially identifiable schools. In 1971, when integration

was ordered, 48% of the black students attended identifiable schools.

(Foster, Vol. I, Pgs. 5-7), (P. Ex. 24, Table 5A); (B) The number of

black students attending racially isolated schools has tripled since

1971, Id.; (C) and reciprocally, the number of black students attending

integrated schools has decreased from 52% in 1971 to 20% in 1983; (2) The

same schools that were segregated through de 1ure restriction in 1968,

(Foster, Vol. I, Pg. 11) are likely to be "still predominantly black."

-21 -

(Foster, Vol. I, Pg. 13), (P. Ex. 24, Table 6); (3) Schools In Fort

Lauderdale today have Increasingly higher enrollments of black students

than in 1968, in comparison to the entire County. (Foster, Vol. I, Pgs.

15-17), (P. Ex. 24, Table 7); (4) Black students in more racially

isolated schools have generally performed poorer on standardized

achievements tests, (Foster, Vol. I, Pg. 24), (P. Ex. 24, Table 8).

69. Based upon these findings, the Court determines, as related by

Dr. Foster, that blacks are "still less fitted than their white

counterparts" in Fort Lauderdale to "participate in the voting process."

(Foster, Vol. I, Pg. 48).

3. PRESENT SOCIO-ECONOMIC STATUS OF BLACKS

70. Dr. Marvin Dunn, Community Psychologist and Professor at Florida

International University, reviewed factors depicting the comparative

socio-economic status of blacks and whites in Fort Lauderdale and their

implications for black participation in the political process (Dunn, Vol.

IV, Pgs. 112-126). Various socio-economic factors which include income,

occupational status, educational level, home ownership, quality of

neighborhoods and family structure indicate that "blacks are

substantially less well-off in the City of Fort Lauderdale than whites"

(Dunn, Vol. IV, Pg. 123).

71. Blacks earn significantly less income than whites in Fort

Lauderdale (Dunn, Vol. IV, Pg. 114). In 1979, the average median income

for all families in Fort Lauderdale was $15,410, while the median income

for black families was $9,761. (P. Ex. 15, Tab 5).

72. Black adults in Fort Lauderdale are significantly under educated

as compared to white adults (Dunn, Vol. IV, Pg. 118). As of 1980, one of

every three (331) black adults had an eighth grade or less education as

compared to only one of every 10 (101) white adults. (P. Ex. 15, Table

-22-

r r

3). Over 421. of white adults had received some college education as

compared to only 13X of black adults. (P. Ex. 15, Tab 3). Similarly,

approximately 211 of white adults had four years of college as compared

to only 4. lit of black adults. (P. Ex. 15, Tab 3).

73. Blacks are grouped at the lower level of the employment scale

(Dunn, Vol. IV, Pg. 120). Approximately 281 of the white work force hold

professional and executive type positions as compared to 101 of the

blacks (P. Ex. 15, Tab 4), (Dunn, Vol. IV, Pg. 120). On the opposite end

of the scale, nearly one in every three blacks work in service

occupations. (P. Ex. 15, Tab 4).

74. Black households in Fort Lauderdale are nearly twice as likely

to be renters as opposed to home owners. (Dunn, Vol. IV, Pg. 122), (P.

Ex. 15, Tab 6). 611 of white households live in homes they own as

opposed to 301 of black families. (P. Ex. 15, Tab 6). Black households

also are more likely to occupy overcrowded living conditions and live in

slum and blighted areas (P. Ex. 18, Tab 7), (Dunn, Vol. IV, Pg. 122).

75. Blacks' lower socio-economic status impedes their participation

in the political process (Dunn, Vol. IV, Pg. 124). It deters their

participation in civic groups and organizations that are effective

instruments in a community's political participation. (Dunn, Vol. IV, Pg.

125). By being poorer, blacks are discouraged from seeking political

office because of the relative difficulty in raising campaign funds.

(Dunn, Vol. IV, Pg. 126). By being less educated, a group is less

knowledgeable and less likely to ascertain issues that are important to

their future. (Dunn, Vol. IV, Pg. 126).

4. RACIALLY POLARIZED VOTING - GENERAL FINDINGS

76. Racially polarized voting occurs when there is a difference in

political behavior between white voters and black voters. Racially

-23-

T

polarized voting, synonymous with racial bloc voting exists, as in this

case, when members of a particular race to a substantial degree vote for

candidates of the same race, (de la Garza, Vol. II, Pg. 161).

77. Dr. Rodolfo 0. de la Garza, qualified as an expert political

scientist in the area of electoral behavior, (de la Garza, Vol. II, Pgs.

150-157, 160, 280-281), testified on behalf of Plaintiffs concerning

generally, the differences in political behavior between blacks and

whites within the City of Fort Lauderdale over the past several decades,

and particularly, the extent of racially polarized voting in City

elections since black candidates first ran in 1957.

78. This Court now reviews the various measurements of racial

polarization as presented by the parties.

a. THE BI-VARIATE REGRESSION ANALYSIS

79. Dr. de la Garza conducted a series of different studies, one of

which involved a "regression analysis of support received by various

black candidates" who had run for the City Commission from 1957 to 1982.

(P. Ex. 25, Table 2).

80. One standard measure of gauging racially polarized voting in

this type of analysis examines the correlation between the number of

voters of one race and the number of votes received by a candidate of the

same race, (de la Garza, Vol. II, Pgs. 251-256), (P. Ex. 25, Table 2,

Column 1). This technique is utilized in order to determine if the first

variable, race, has had an impact or is associated with the second

variable, election results, (de la Garza, Vol. II, Pg. 251-252). The

regression coefficient, called "R", can range in size from 0 to 1. An

"R" of 0 means that there is no relationship between the variables while

a regression coefficient of 1.0 means a perfect relationship between the

two variables - as in this case, that the percentage of black registered

-24-

r r

voters per precinct and the percentage of the support received by a black

candidate per precinct are directly related, (de la Garza, Vol. V, Pg.

255). An analysis of voting, under this bi-variate model, showing

correlations of .2 or .3 is considered good; .5, .6, or .7 is very well,

and .9 is "extraordinary." (de la Garza, Vol. II, Pgs. 252-255) ("When

you get over .9, it is simply phenomenal in any statistical test that you

£o run."). Dr. de la Garza did calculations on the 18 elections in

which black candidates had run for office between 1957-1982. In

measuring the percentage of black registered voters per precinct and the

percentage of the support received by the black candidate, he found an

absolute value between .81 and .99 with 13 of the 18 elections over .90.

(P. Ex. 25, Table 2, Column 1).

81. In a second regression analysis, Dr. de la Garza, utilized the

identical regression coefficient methodology and addressed another

independent variable. Here, the same dependent variables were examined -

the percentage of votes received by a black candidate as a function of

another independent variable - the turnout ratio in a given precinct.

This independent variable, the turnout ratio, is simply the number of

votes actually cast in relation to the number of votes that could have

been cast, (de la Garza, Vol. II, Pgs. 256, 258), (P. Ex. 25, Table 2,

Column 2). Nine of the sixteen elections examined had correlations

calculated over .90; six elections fell between .72 and .89 and one

election (1982 - Alston Primary) was calculated at .51. (P. Ex. 25, Table

2, Column 2).

82. Finally, the two regressions were combined, resulting in

correlations calculated between .82 and .99 in sixteen elections,

fourteen of which had levels greater than .91. (de la Garza, Vol. II, Pg.

259, 261), (P. Ex. 25, Table 2, Column 3). Translated beyond its

-25-

statistical context, a level beyond .91 means simply that 91% of all

variance in votes received for the black candidate can be explained by

the race of the voter, (de la Garza, Vol. II, Pg. 251-254, 330).

b. SUPPORT FOR WINNING CANDIDATES

83. Dr. de la Garza further analyzed differing black and white

voters electoral behavior to determine polarization by measuring the two

racial communities' ultimate support for the 5 winning candidates in each

general election. (4 winning candidates in 1979). Voter support for the

ultimate winning candidates was analyzed in all general elections between

1971 through 1982 in racially homogenous precincts. In virtually every

case, in each white precinct white voters cast their votes for one of the

5 winning candidates more than 50% of the time and in many instances as

much as 60% to 70%. Among black voters, the percentage of support of

their votes for winning candidates was in the range of 10%-12% with the

exception of the DeGraffenreidt elections, (de la Garza, Vol. II, Pgs.

207- 208), (P. Ex. 25, Table 4). The pattern that emerged over this 11

year period, structured in graphic format in Plaintiffs' Exhibit 36, and

recognized by Defendants' own expert (Bullock, Vol. V-A, Pgs. 505, 508),

is that whites cast a disproportionate share of their votes for winners

as compared to their black counterparts, (de la Garza, Vol. II, Pgs.

208- 209).

84. Defendants' analysis, entitled "Success of Candidates Most

Favored by Blacks", (D. Ex. 13, Table 3 and 4, Pg. 12), did not address

the degree or percentage of support blacks gave any of the 5 winners.

(Bullock, Vol. V-A, Pg. 508). All Defendants measured in this analysis

was the numerical order in which winning candidates had finished in black

precincts.

-26-

c. SUPPORT FOR BLACK CANDIDATES

85. An additional and corollary measure of polarization focused upon

the different voting behavior of the black and white electorates in their

support for black candidates. Black? overwhelmingly support black

candidates. White voters do not.fln all elections analyzed from

1971-1982, 861 of black voters cast at least one vote for a black

candidate. Only 32* ofsll white voters cast a vote for a black

candidate. (P. Ex. 38). I

;is o'F’1786. An analysis oT~17 elections in which blacks ran for the

Commission over a 25 year period between 1957 to 1982, encompassing a

total of 89 black precincts and 968 white precincts, showed that in every

primary and general election other than the one in which Alston ran in

1982, a black finished first in every one of the black precincts -- every

time, (de la Garza, Vol. II, Pgs. 245), (P. Ex. 25. Table 3). In

contrast, (1) no black candidate has ever finished first in any one of

the white precincts. (P. Ex. 1, Pgs. 84-157); (2) in the white

precincts, black candidates in every election did significantly worse

than every other white candidate; and when it really counted in terms of

winning in the general rather than the primary, blacks faired even worse

in those precincts; (de la Garza, Vol. II, Pg. 246), (P. Ex. 25, Table

3), (Bullock, Vol. V-A, Pg. 541); and finally, (3) the only non-incumbent

black candidate who ever won, DeGraffenreidt in the 1973 general

election, finished in the top 5 in only 101 of the white precincts. (P.

Ex. 25, Table 3). Even Defendants' expert recognized that black

candidates, with the exception of DeGraffenreidt (1975 and 1979 primary),

faired significantly worse in the white precincts as compared to the

black precincts. (Bullock, Vol. V-A Pg. 537). See, also, (D. Ex. 13, Pg.

17). ("The behavior of black voters is quite unlike that of whites.

-27-

Except for Alston In 1982, and DeGraffenreidt in the 1975 primary, blacks

have always gotten the votes of more than 90X of those who turned out in

heavily black precincts.")

d. BLACKS IMPACT ON THE OUTCOME OF ELECTIONS

87. A further study conducted by Plaintiffs analyzed the election

results to determine whether the polarization of voting was substantively

significant. This inquiry simply addressed whether the voting was

sufficiently polarized so that the result of any of the twelve primary

and general elections between 1971 through 1982 would have been different

if it had been held with only white voters. In every election between

1971-1982, involving 120 candidates - other than one candidate in the

1971 primary and another in the 1973 general - the results as to which \

candidate won, or in the instance of a primary election had finished in a

Nposition to qualify for the general, would have been identical even if no

black voters had ever voted, (de la Garza, Vol. II, Pgs. 216-218), (P.

Ex. 25, Table 5).

88. The conclusion drawn from this analysis is that, with the

exception cited, in an at-large system, votes cast by black citizens

simply do not influence the outcome of the elections, (de la Garza, Vol.

II. Pg. 219).

e. THE AVERAGE NUMBER OF VOTES CAST BY THE VOTERS

89. Black voters use fewer of the votes available to them in an

attempt to ameliorate the discriminatory effect of Fort Lauderdale's

at-large elections. The ultimate measure of participation is the number

of votes cast by each voter because what counts insofar as a candidate's

success is simply the number of votes received, (de la Garza, Vol. II,

Pg. 195).

-28-

r c

90. Consistently and significantly, in order to increase the

possibility of electing candidates of their choice, black voters cast

less of their 5 ballots than white voters, (de la Garza, Vol. II. Pg-

190), (Bullock, Vol. V-A, Pg. 500). In all elections analyzed, other

than in 1979, white voters utilized more than A of their 5 votes, (de la

Garza. Vol. II. Pg- 202), (P. Ex. 25, Table 1). Black electoral behavior

significantly differs. In every election since 1971, black voters used

less than three of their votes. (Id.) Indeed, this strategy was one of

the factors attributable to the DeGraffenreidt victory in 1973, the only

time in the history of the City of Fort Lauderdale that a black

non-incumbent won. In that election, blacks cast less than two (1.7) of

their votes. (Id.)

91. The consequences of this electoral behavior, a behavior which

differs between black and white voters, is two-fold. First, it signifies

that white voters find almost twice the candidates of their choice to

vote for than do blacks. See, e^. . (P. Ex. 14A. April 10, 1963)

("Through 'one shot' voting a 'favored candidate gets a vote, and the

other 24 candidates are in effect, voted against.") Second, the ability

of blacks to influence the outcome of an election in Fort Lauderdale is

greatly reduced since in order to maximize their effort to elect

candidates of their choice, they must in turn forfeit their right to vote

for a full slate of candidates. On the other hand, white voters in this

system need not forfeit any of their votes in order to elect candidates

of their choice, (de la Garza, Vol. II, Pgs- 204-205).

f. THE MULTI-VARIATE ANALYSIS

92. The Court recognizes, as candidly admitted by the City's expert,

that the use of a multi-variate analysis to explain electoral behavior

has never been embraced by any Court. Indeed, this is the first time it

- 2 9 -

has ever been applied to voting dilution litigation. Further, it is the

invention of the City's expert. Dr. Bullock, who is the only scholar to

have written about it in one of his publications and has tested it out -

for the very first time - in this litigation. (Bullock, Vol. V-A Pgs.

517-518). Its very novelty, of course, does not in itself render the

analysis invalid. It does, however, raise certain problems in its

application to voting rights litigation which make the general findings

unsound.

93. First. Defendants' multi-variate analysis, with its

precision-1 ike crunch of numbers from the computer, as well as other

statistical compilations wrenched from the political-social context of

the City, lead to conclusions which are not supported by the reality of

Fort Lauderdale politics. For instance, (1) under the multi-variate

model for electoral success, Defendants have determined that candidates

run better if, among other factors, they are female. (Bullock, Vol. V,

Pg. 387), (D. Ex. 13, Pg. 58). However, the political reality of Fort

Lauderdale is simply that only one female--current Commissioner Virginia

Young--has ever been elected to City office in the past 95 years. (P. Ex.

5) (Genevieve Pynchon was elected in 1937.); (2) under other analysis,

Andrew DeGraffenreidt, the single black elected in Fort Lauderdale's

entire history, erroneously is counted as "three successful Black

candidates" (Bullock, Vol. V-A, Pg. 923) ignoring his obvious uniqueness

in city politics as well as his own personal unique characteristics

resulting in his success; (3) the fact that an incumbent--or even 2

incumbents as in the case of the initial DeGraffenreidt successful

election in 1973--chose not to run for re-election was never considered

as a factor in the multi-variate analysis. (Bullock, Vol. V-A, Pgs.

985-986). Since incumbency is recognized by both parties as a critical

-30-

r r /

factor in a candidate's success (Bullock, Vol. V-A, Pg. 475), (D. Ex. 13,

Pg. 73) ("[I]n Ft. Lauderdale incumbents rarely lose."), (de la Garza,

Vol. II, Pg. 220), the absence of this consideration simply defies the

political reality of one of the explanations for the only successful

non-incumbent black candidacy in the city history. (DeGraffenreidt, Vol.

I, Pgs. 61-62), (de la Garza, Vol. II, Pg. 234); (4) in the multi-variate

analysis, endorsements are considered a significant factor of candidate

success. (Bullock, Vol. V, Pg. 384), (D. Ex. 13. Pg. 58). However, black

candidates have received disproportionately more endorsements (Bullock,

Vol. V-A, Pgs. 490-491) and yet the endorsed black candidates - Kennedy

(Id.), Hastings (Id.), (Hastings, Dep., Pg. 34-35, 59-60), DeGraffenreidt

in 1979 (Pg. 555)--continue to lose; (5) Defendants' statistical analysis

of the success ratio of black candidates (D. Ex. 13, Tables 1 and 2)

ignored 9 unsuccessful black candidates who had run in more than one-half

of the elections in which black candidates ran and lost--all prior to

1971. (Bullock, Vol. V-A, Pgs. 493-496); (Bullock, Vol. V-A, Pg. 494)

(The explanation - "an arbitrary judgment" to discount these elections);

(6) Defendants’ definition of what constitutes support--whether a white

voter had cast a ballot for a black candidate (Bullock, Vol. V, Pg. 360),

is totally divorced from the reality of how a candidate is elected to

city office. That is, support insofar as having any meaning for a

candidate's success, can only be considered in the context of the total

number of votes a candidate receives in relationship to the total number

of votes received by the other candidates (Bullock, Vol. V-A, Pg- 534).

Simply, the political reality of an election is that a candidate succeeds

or fails by virtue of the total number of votes received; (7) the

Defendants' model for measuring electoral success (Bullock, Vol. V, Pg.

384-385), ("[M]ore likely to win if you are an incumbent, you spend more

-31- !

£ r

money, if the newspaper endorses you, and when white turnout is lower.”),

(D. Ex. 13, Pgs. 57-60) is virtually wrenched from the underlying factors

which explain the most important election raised in this lawsuit--the

DeGraffenreidt 1973 victory. In that election--so important because it

is the first and only time a non-incumbent black has ever won--the

factors which contributed to his victory, ignored in the multi-variate

success model, include: (i) a City_record^turnout, which Included a

record 41.8X of the black voters (P. Ex. 25A), infra, Hill; (ii) the

can d 7 d ^ 3 ^ d by a n ^ acially _ ^ en̂ flable laSt namG Wh°

actively p ^ ^ T ^ ^ i g n stra77gy in which he concealed his race from

many of the w M t T T u ^ r a t e . inf^T 111077111) a black electorate which

3.3 of their 5 votes in order to elect a single

candidate^ of their choice (P. Ex. 25, Table 1); (iv) an election in which

two white incumbents had chosen not to run (DeGraffendreidt, Vol. I, Pgs.

61^62v T ( de^lTGarzarv^l^lTPg. 234); (v) a primary election in which

DeGraffenreidt --virtually unknown in the white community--was able to

get "lost” among 30 other candidates (DeGraffenreidt, Vol. I, Pgs.

56-57), (de la Garza, Vol. II, Pg- 234); (8) the fact that the City's

expert concluded that race plays an insignificant role in city elections

notwithstanding: (i) that only one black citizen has ever won in the

context of 16 other unsuccessful black candidacies spanning two and

one-half decades (P. Ex. 8. Fact 1); (ii) that racial separation,

isolation, and discrimination has and continues to play a major role in

the life of black citizens in Fort Lauderdale in the context of ((a))

residential segregation, supra, 111146-47; ((b)) municipal employment

practices, supra, 111150-58; ((c)) educational opportunities, supra,

111167-69; ((d)) blacks' participation in the very threshold of the

political process, membership on policy-making City boards and

-32-

r r

committees, supra, 111159-64; ((e)) and public housing facilities, supra,

111165-66; and (9) a finding by Dr. Bullock, that is in apparent conflict

with the highest ranking current city official, Mayor Dressier, who

candidly recognized that a single-member district system would highly

likely" result in a "black representative on the Commission." (Dressier,

Vol. V, Pg. 294).

94. Second. widely varying results may be obtained depending on

subjective judgments as to which data is to be included or excluded. For

instance, while political scientists - including Defendants’ expert

(Bullock, Vol. V-A), Pgs. 433-434) - agree that other factors can

significantly effect voting behavior, these factors or "independent

variables" were not tested in the analysis. They include, (i)

qualifications of the candidate, including education (Bullock, Vol. V-A,

Pg. 434); (ii) past involvement or exposure in the political process,

such as service on City boards or committees (Bullock, Vol. V-A, Pg.

437); (iii) support or endorsements from slating organization or

associations, for example, in Fort Lauderdale, the Broward Citizens'

Committee (Bullock, Vol. V-A Pgs. 437-438), (Shaw, Vol. V, Pg. 258, Dep.

Pgs. 11-20); (Dressier, Vol. V, Pg. 281-283); infra; (iv) how well a

candidate finishes in the primary beyond meeting the threshold of

qualifying for the general election; e.g., his position between 1st and

10th place. (Bullock, Vol. V-A, Pgs. 439-444); (v) the candidate’s name

recognition as it relates to the racial or ethnic identity as a cue that

influences voting behavior (Bullock, Vol. V-A, Pgs. 448-450); (vi) the

general political climate of the times (Bullock, Vol. V-A, Pgs. 451 452),

(vii) the varying socio-economic characteristics of the electorate which

influence political behavior from precinct-to-precinct or within areas of

-33-

(

the City. (Bullock, Vol. V-A, Pgs. 453-455); and (viii) the number of

incumbents choosing not to run in an election, a consideration which

directly increases the opportunity of success for a non-incumbent.

95. Third, significant methodological flaws exist as to those

independent variables that were utilized in the multi-variate analysis:

(i) a total dollar figure with an inflation index utilized to measure

/campaign contributions included only monetary donations (Bullock, Vol.

/ V-A, Pg. 460-461). However, non-monetary, in-kind campaign contributions

V/ from the black community played a powerful and valuable role in the black

candidates' campaigns. (DeGraffenreidt, Vol. I, Pgs. 53-54), (Free

I office space, cars, food since "[t]hat's what you get mostly in the

/ minority community bedcause there's limited funds in that area. ),

/ (Hastings, Dep., Pg. 26) (Tremendous in-kind contribution from black

community.). These black candidates, whose natural constituency, the

black community, has limited financial resources organized other forms of

campaign contributions which were not translated into a monetary figure

in the multi-variate computer runs. (Bullock, Vol. V-A, Pgs. 463-466),

(ii) a code for Incumbency was factored into the analysis, but there was

no differentiation in the value assigned to account for past number of

terms served or the incumbent's position, such as a mayor or

commissioner. Each of those later factors would affect name recognition

and reflect other built-in advantages derived from various incumbent

positions. (Bullock, Vol. V-A, Pgs. 472-473); (iii) endorsements were

factored into a code and utilized in the analysis, however, no

distinction between either the Fort Lauderdale News or Miami Herald was

made to account for circulation differences that were likely within the

(Bullock, Vol. V-A, Pgs. 485-486). >

-34-

r

City of Fort Lauderdale or between the black and white communities.

(Bullock, Vol. V-A, Pgs. 487-488).

96. Fourth, and most significantly, several of the independent

variables, while at least superficially unrelated to race, are in reality

highly associated and intertwined with the role which race has played in

the City's elections. Thus the causal factor that produces the values

assigned to the independent variables are in fact race related. Although

incumbency is viewed as a powerful factor in achieving success in Fort

Lauderdale Commission elections, the fact is that except for the unique

experience of the DeGraffenreidt incumbency campaigns of 1975 and 1977,

it is a characteristic limited solely to past and now present white

commissioners. It simply always has been and continues to be more

difficult for a black candidate to win city office since there are no

black incumbents (Bullock, Vol. V-A, Pgs. 480-481).

97. Campaign contributions, which along with incumbency in the

multi-variate computer run, explain a candidate's success, is also a race

related variable. Black candidates have consistently received most, if

not all, of their contributions from the black community (Reddick, Vol.

V, Pgs. 248-249); (Hastings, Pg. 11); (DeGraffenreidt, Vol. I, Pgs. 65.

79). The natural result of dependence on the isolated and segregated

black community of Fort Lauderdale, supra, 111146-47, which is poorer,

supra, 111170 - 74, (Bullock, Vol. V-A, Pg. 464); smaller and has drastically

less economical resources than its white counterpart, is a campaign in

which a black candidate is highly disadvantaged financially. (Bullock,

Vol. V-A, Pgs. 465-466).

98. Not only are the factors of incumbency and campaign

contributions directly related to race, there exists a statistically

significant association of each of the Independent variables, as well as

-35-

r(

a third variable - endorsements (Bullock, Vol. V-A, Pgs. 476-477) (Stat

istically significant relationship at .334 level between incumbency and

campaign expenditures); (Bullock, Vol. V-A, Pgs. 478-48<f) (Even greater

statistical relationship at .425 level between incumbency and endorsements).

99. Thus, where there exists a statistically significant, although

not necessarily perfect, correlation of three of the variables it becomes

difficult to disentangle their separate effects on the dependent

variable. Moreover, these variables, analyzed in an artificially

isolated manner, cannot be compartmentized from and indeed are directly

\____ ^

associated with race itself.

g. THE BLACK CANDIDATES - 1957 to 1982

(i) 1957-1967

100. In 1957, Nathaniel Wilkerson, the first black candidate to run

for City Commission, announced his candidacy by stating: "he hope(d) to

serve as a link between the negro population and the City government."

(P. Ex. 14A, March 4, 1957).

101. Although unsuccessful in his 1957 and 1959 campaigns, Wilkerson

received winning support from all the City "negro precincts. (P. Ex. 14A,

April 10, 1957; April 29, 1959), (P. Ex. 25, Table 3).

102. In 1963 and 1967, Thomas Reddick, described by the media as

a "negro lawyer," was a candidate for the Commission. (Reddick, Vol.

V, Pgs. 247-249). In those campaigns, Reddick relied primarily on

contributions from blacks because of difficulties raising funds from

whites. (Reddick, Vol. V, Pg. 248). He also focused his campaign in

the black community because of a lack of cooperation from the whites.

(Reddick, Vol. V. Pg. 256). Despite his qualifications, which

ultimately lead to his appointment as the first black County Judge in

Broward County. Reddick, in receiving significant support from black

-36-

r

voters, and less than minimal support from whites. (P. Ex. 25, Table 3).

103. In 1967, blacks developed a campaign strategy in which five

blacks ran for the Commission, (de la Garza, Vol. IV, Pgs. 221 222).

Alcee Hastings, an architect of that strategy, explained that the five

black candidate strategy was taken to encourage black turnout. (Hastings,

Dep., Pgs. 36-38). While not succeeding in electing any black

commisioners, this strategy lead to increase black voter turnout in

subsequent elections.

(ii) 1969-1971: ALCEE HASTINGS

109. Alcee L. Hastings, then an attorney in private practice in Fort

Lauderdale and currently a United States District Judge in the Southern

District of Florida, ran unsuccessfully in 1969 and 1971 for the City

Commission. (Hastings, Dep., Pg. 1). Judge Hastings, who had waged

perhaps more political campaigns than any present or past--white or

black--politician in the State of Florida (Hastings, Dep., Pgs. 8-10)

(Candidate for Florida House, Florida Senate, State Public Service

Commission and United States Senate), was one of the most politically

experienced candidates for City office.

105. As a black, his race had been an issue in both of the 1969 and

1971 campaigns. Hastings had been unable to secure significant campaign

contributions in either election from the white community (Hastings,

Dep., Pg. 11) (Whites didn't "want to be on record as making a

contribution"); had been limited to campaigning in certain areas in the

white community (Hastings, Dep., Pgs. 19-20, 29, 72); and had been

continually identified in the media by his race, unlike white candidates.

(Hastings, Dep., Pgs. 18, 28).

- 3 7 -

r r

106. Hastings' observations that he had lost the election because he

is black (Hastings, Dep. , Pgs. 13, 47-48) is corroborated by_the__elfiiLLioa