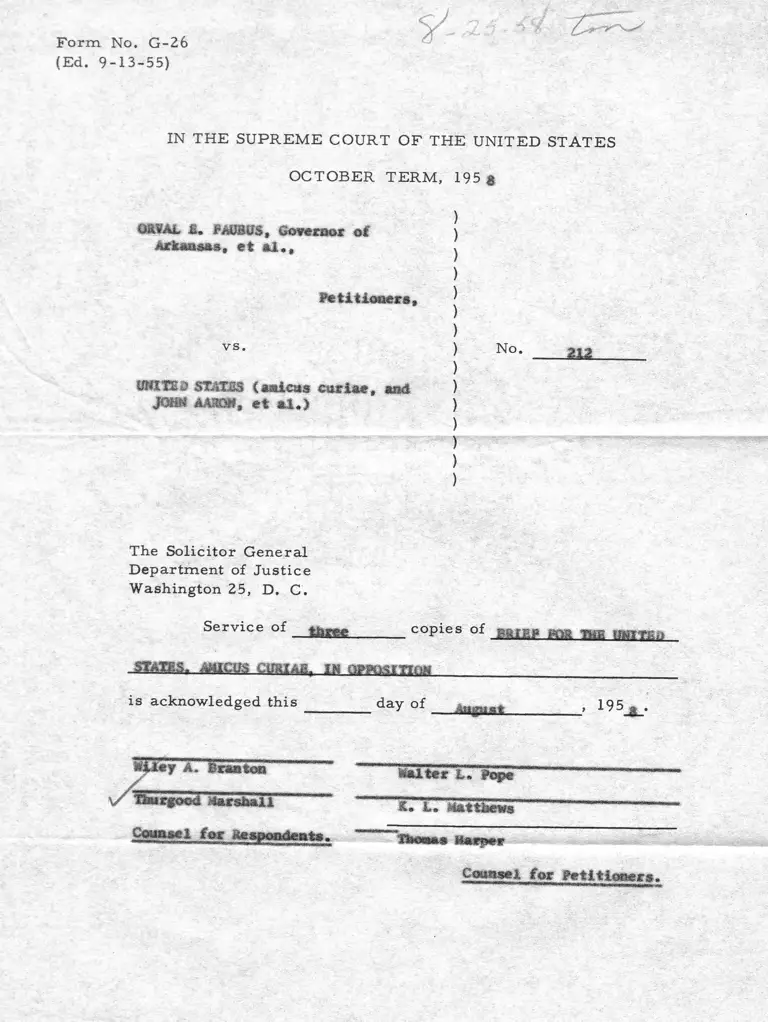

Faubus v. United States Brief Amicus Curiae in Opposition

Public Court Documents

August 25, 1958

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Faubus v. United States Brief Amicus Curiae in Opposition, 1958. 47ef2c7e-b19a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/74623d63-604a-45b4-8f57-779d6a2fcf15/faubus-v-united-states-brief-amicus-curiae-in-opposition. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

Form No. G -26

(Ed. 9 -1 3 -5 5 )

IN TH E S U P R E M E C O U R T O F TH E U N ITED S T A T E S

O C T O B E R T E R M , 195 *

oaVAL fAUBVS, Governor o f

i, et * 1 .,

Petitioners*

v s .

UNI IT,.' STATES ( arnicas curiae* and

JN3MN AAS3H* et * 1 .)

No. i l l

The S o lic ito r G en era l

D ep a rtm en t o f J u stice

W ash in gton 25, D . C .

S e r v ic e o f c o p ie s o f sa ra s ana fKfi W f i n

- J S X & B S . AMICUS CUMIAfi, IN O W M ItM l___

is a ck n ow led g ed th is day o f , 1 9 5 * .

a - rr&aton W aiter L . Pope

Thurgood darsfcali a . t . W attMws

Cgittsel for kespondeuta. y&oemm

Counsel fm Petitioners.

No. 212

J n the S u p re m e flfmtrt # f the S u ite d s t a t e s

October Teem, 1958

Orval E. Eaubus, Governor of A rkansas, et al.,

PETITIONERS

' ' . ' V.

United States of A merica, A mices Curiae, and

J ohn A aron, et al.

ON PETITION EON, A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED

STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE EIGHTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF FOR THE UNITED STATES, AMICUS CURIAE,

IN OPPOSITION

, - - ' - C' ■■ . , . .V ; ,

J. L E E R A N K IN ,

Solicitor General,

G EORGE CO C H R A N DOUB,

Assistant Attorney General,

M O RTON H O L L A N D E R ,

S E Y M O U R F A R B E R ,

Attorneys,

Department of Justice, Washington 25, D. C.

——

I N D E X

Pase

Opinions below------------------------ : 1

Jurisdiction______________________________________________ 1

Questions presented______________________________________ 2

Statute involved_________________________________________ , 2

Statement_______________________________________________ 3

Preparation for carrying out the plan------------------------ 4

The placing of the Arkansas National Guard at Cen

tral High School_______________________________ — 5

The appearance of the United States as amicus curiae_ 6

The filing of the affidavit of bias and prejudice---------- 8

Argument_______________________________________________— 11

Conclusion_______________________________________________ 22

CITATIONS

Cases:

Aaron v. Cooper, Civil Action No. 3113 (E. D. Ark.),

certiorari denied, June 30, 1958------------------------------ 4

Aaron v. Cooper, 243 F. 2d 361---------------------------------- 4

A. B. Dick Co. v. Marr, 197 F. 2d 498, certiorari

denied, 344 U. S. 878------------------------------------------------- 19

Berger v. United States, 255 U. S. 22-------------------------- 16

Bishop v. United States, 16 F. 2d 410------------------------- 13

Bommarito v. United States, 61 F. 2d 355------------------------ 13

Booth v. Fletcher, 101 F. 2d 676, certiorari denied, 307

U. S. 628____________________________________________ 19

Bowles v. United States, 50 F. 2d 848, certiorari denied,

284 U. S. 648_______- ___________________________ 13

Brown v. Board oj Education, 347 U. S. 483--------------- 3

Chqfin v. United States, 5 F. 2d 592, certiorari denied,

269 U. S. 552________________________________________ 13

Craven v. United States, 22 F. 2d 605, certiorari

denied, 276 U. S. 627________________________________ 15

Dugas v. American Surety Co., 300 U. S. 414------------ 20

Exchange, The, 7 Cr. 116_ _____________________________ 18

476557— 58—— 1 (I)

II

Cases—Continued Pago

Helmbright v. John A. Gebelein, Inc., 19 F. Supp. 621 19

Henry v. Speer, 201 Fed. 869------------------------------------- 16

Hibdon v. United States, 213 F. 2d 869----------------------- 14

Julian v. Central Trust Company, 193 U. S. 93---------- 20

Kasper v. Brittain, 245 F. 2d 97, certiorari denied, 355

U. S. 834_________________________________________ 19,21

Kern River Company v. United States, 257 U. S. 147 20

Lipscomb v. United States, 33 F. 2d 33----------------------- 13

Lisman, In re, 89 F. 2d 898-------------------------------------- 16

Littleton -v. DeLashmutt, 188 F. 2d 973----------------------- 16

Local Loan Co. v. Hunt, 292 U. S. 234----------------------- 20

New York v. New Jersey, 256 U. S. 296--------------------- 20

Palmer v. United States, 249 F. 2d 8 -------------------------- 16

Price v. Johnston, 125 F. 2d 806, certiorari denied, 316

U. S. 677_________________________________________ 15

Root Refining Co. v. Universal Oil Products Co., 169

F. 2d 514, certiorari denied, 335 U. S. 912-------------- 18

Rossi v. United States, 16 F. 2d 712--------------------------- 13

Sanitary District v. United States, 266 U. S. 405-------- 20

Scott v. Beams, 122 F. 2d 777, certiorari denied, 315

U. S. 809_________________________________________ 15

Securities and Exchange Commission v. United States

Realty <& Improvement Co., 310 U. S. 434---------------- 18

Steelman v. All Continent Co., 301 U. S. 278-------------- 20

United States v. Calijornia, 332 U. S. 19-------------------- 20

United States v. Gilbert, 29 F. Supp. 507---------------------- 15

United States v. Onan, 190 F. 2d 1----------------------------- 15

United States v. United Aline Workers of America, 330

U. S. 258_________________________________________ 21

United States Realty & Improvement Co., In re, 108

F. 2d 794_________________________________________ 18

Universal Oil Products Co. v. Root Refining Co., 328

U. S. 575_________________________________________ 15, 17

Constitution and Statutes:

Constitution of the United States, Article II I ------------ 20

5U . S. C. 309_______________________________________ 19

5U . S. C. 316_______________________________________ 19

28 U. S. C. 144____________________________________ 2,8, 11

28 U. S. C. 1651_____________________________________ 20

28 U. S. C. 2284_____________________________________ 9

Arkansas Statutes, 1947 (1956 Replacement), 12-712. 13

Kn to Supreme aj-ottri of to Knitt& jStsies

October Term, 1958'

No. 212

Orval E. F aubus, Governor of A rkansas, et al.,

PETITIONEES

V.

U nited States of A merica, A micus Curiae, and

J ohn A aron, et al.

ON PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED

STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE EIGHTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF FOR THE UNITED STATES, AMICUS CURIAE,

IN OPPOSITION

O PIN IO N S B E L O W

The findings of fact, conclusions of law, and order

of the United States District Court for the Eastern

District of Arkansas (R. 65-74) are reported as

Aaron v. Cooper, 156 P. Supp. 220. The opinion of

the United States Court of Appeals for the Eighth

Circuit (Pet. App. la-21a) is reported at 254 E. 2d

797.

JU R IS D IC T IO N

The judgment of the United States Court of Ap

peals for the Eighth Circuit was entered on April 28,

(i)

2

1958 (R. 102). The petition for a writ of certiorari

was filed on July 24, 1958. The jurisdiction of this

Court is invoked under 28 U. S. C. 1254 (1).

QUESTIONS P R E SE N T E D

1. Whether both courts below correctly held that the

particular facts of this ease showed that there was

undue delay in the filing of petitioner Faubus’ affi

davit of bias and prejudice against the district judge.

2. Whether, wholly apart from the question of

undue delay, the affidavit of bias was correctly stricken

because of legal insufficiency.

3. Whether the district court erred in refusing to

dismiss the amicus petition of the United States.

S T A T U T E IN V O L V E D

28 U. S. C. 144 provides:

Whenever a party to any proceeding in a

district court makes and files a timely and

sufficient affidavit that the judge before whom

the matter is pending has a personal bias or

prejudice either against him or in favor of any

adverse party, such judge shall proceed no fur

ther therein, but another judge shall be as

signed to hear such proceeding.

The affidavit shall state the facts and the

reasons for the belief that bias or prejudice

exists, and shall be filed not less than ten days

before the beginning of the term at which the

proceeding is to be heard, or good cause shall

be shown for failure to file it within such time.

A party may file only one such affidavit in any

case. It shall be accompanied by a certificate

of counsel of record stating that it is made in

good faith.

3

S T A T E M E N T

A brief summary of the prior proceedings in Aaron

v. Cooper may be helpful to the Court. The action

was brought originally on February 8, 1956, by cer

tain Negro school children in Little Rock, Arkansas,

to enjoin officials of the Little Rock School District

from operating the public school system in a manner

which allegedly discriminated against them because of

race (143 F. Supp. 855 (E. D. A rk.)). In answering

the complaint, the School District submitted to the

court a gradual three-phase plan of school desegrega

tion, which was scheduled to be put into effect in the

fall of 1957, and which was designed to accomplish

complete desegregation of the schools not later than

1963. The first phase of the plan, which was to begin

in the fall of 1957, was to commence desegregation at

the senior high school level. The second phase was to

begin at the junior high school level, following suc

cessful desegregation of the senior high school level

(estimated at two to three years). The third phase

was to be at the elementary school level, following

completion of the first two phases (R. 66).

On August 28, 1956, the district court, after a full

hearing, concluded that the School District had acted

in good faith, and that the Little Rock plan of gradual

school desegregation was in accord with this Court’s

mandate in Brown v. Board of Education, 347 II. S.

483. The court thereupon denied the Negro school

children’s request for injunctive relief, but specifically

retained jurisdiction of the case ‘ ‘ for the entry of such

other and further orders as may be necessary to obtain

the effectuation of the plan” (143 F. Supp. at 866;

4

R. 68). In affirming the judgment of the district

court, and in approving the Little Rock school plan

as “ in present compliance with the law” , the Court of

Appeals expressly noted that the district court was to

retain jurisdiction to ensure compliance with the plan.

Aaron v. Cooper, 243 P. 2d 361, 364 (C. A. 8 ) ! No

review of the judgment of affirmance was sought here.

Preparation for carrying out the plan: The district

court’s findings of fact (R. 65-72) are not disputed,

and may be summarized as follows: As provided in

the court-approved plan, desegregation was to com

mence in the fall of 1957 at the senior high school

level. Approximately forty to fifty Negro students

had applied for admission to Central High School.

Their applications had been carefully studied by the

responsible school authorities, and it was finally de

termined that thirteen of these students were partic

ularly suited to make the adjustment involved in

attending a school theretofore composed solely of

white children. All steps necessary for the enroll

ment of these thirteen students in Central High

School, including meetings with the students and their

parents to prepare them for the necessary adjustment,

were completed by the school authorities before the

opening of the 1957 fall term. Pour of the thirteen

students chose not to transfer to Central High School.

Thus, under the school plan for that term, there would 1

1 The district court, on June 20, 1958, ordered the suspension

o f the plan until mid-semester o f the 1960-61 semester. Aaron

v. Cooper, Civil Action No. 3118 (E. D. Ark.), cei'tiorari denied,

June 30, 1958. The Court o f Appeals for the Eighth Circuit

reversed this order on August 18, 1958.

be but nine Negro students in a student body of ap

proximately 2,000. Both the faculty and the student

body were prepared to accept the nine Negro students

(R. 68-69).

The placing of the Arkansas National Guard at

Central High School: On September 2, 1957, peti

tioner Faubus, Governor of Arkansas, caused units

of the Arkansas National Guard, under the command

of petitioners Clinger and Johnson,2 to be stationed

at Central High School with orders “ to place off

limits to colored students those schools theretofore

operated and recently set up for white students * * *”

(R. 69).

Up to this time no crowds had gathered about the

school, nor had there occurred any threats or acts of

violence. The Mayor and Chief of Police at Little

Rock had, however, out of an abundance of caution,

conferred with the school authorities about taking

appropriate steps by the police to prevent any pos

sible disturbances or acts of violence. The Mayor,

the Chief of Police, and the school authorities made

no request to the Governor to assist in maintaining

order at the school; and neither the Governor nor

any State official consulted with the Little Rock au

thorities about whether the city police were prepared

to cope with any incidents which might arise or

whether there was any need of State assistance in

maintaining order (R. 70).

2 General Clinger is Adjutant General o f the Arkansas Na

tional Guard. Colonel Johnson is a Unit Commander of the

Guard.

6

The fall term at Central High School began on

September 3,1957, but none of the nine eligible Negro

students appeared at the school that day, having been

advised not to do so since the National Guard was

stationed at the school (R. 70). On that day, the

district court, after a hearing on a rule to show cause

issued against the school authorities, found that they

had, as a consequence of the stationing of military

guards at the school, requested the Negro students

not to attend school. The court further found that

there was no reason why the desegregation plan could

not be carried out and, accordingly, directed the school

authorities to integrate forthwith the senior high

school grades, in accordance with the previously ap

proved plan (R. 1-3, 71).

The next day, September 4, units of the Guard,

acting pursuant to petitioner Faubus ’ order, forcibly

prevented the nine Negro students from entering the

school grounds. At that time a crowd of spectators

congregated across the street from the school, but no

acts of violence were committed or threatened. The

evidence showed that the Guard could have main

tained order at the school without preventing the at

tendance of the Negro students (R. 70-71).

The appearance of the United States as amicus

curiae: That day, September 4, the district court

wrote the United States Attorney at Little Rock that

it was advised that its order directing the carrying

out of the school district’s integration plan “ has not

been’ complied with due to alleged interference with

the Court’s order” (R. 3-4). The United States At

torney was requested to make an investigation to de-

7

termine the responsibility for the interference, or the

failure to comply with the order, and to report his

findings to the court (R. 4). On September 9, after

having received this report from the United States

Attorney, the district court ordered the Attorney

General and the United States Attorney to appear in

the proceedings as amici curiae and to file a petition

seeking injunctive relief against petitioners (R. 6).

In accordance with this order, the United States, as

amicus curiae, acting through the Attorney General

and the United States Attorney, filed a petition on

September 10 against Governor Faubus, General

Clinger and Colonel Johnson. The petition for in

junctive relief alleged that, in using the Arkansas Ra

tional Guard to prevent eligible Negro students from

attending Central High School, the present petitioners

had obstructed and interfered with the carrying out

of the district court’s previous orders of August 28,

1956, and September 3, 1957; and that, in order to

protect and preserve the judicial process and to main

tain the due and proper administration of justice, it

was necessary that petitioners be made parties de

fendant, and enjoined from further interference with

the court’s orders (R. 6-9).

On the same day, the district court ordered that

petitioners be made parties defendant and that they

be served forthwith with a summons and a copy of the

Government’s petition and the court’s order. The

court set September 20 as the date for a hearing upon

the Government’s application for a preliminary in

junction (R. 9-10).

476557— 58~ --------2

8

The following day, September 11, the plaintiffs (the

school children) moved the court for an order per

mitting them to file a supplemental complaint against

petitioners, seeking the same relief as was sought in

the Government’s amicus petition (R. 10-11, 21-23).

The filing of the affidavit of bias and prejudice;

On September 10, petitioners were notified that they

had been made defendants (Pet. 14). On Sep

tember 19, the day prior to the date set for hearing

of the application by the Government for a prelimi

nary injunction, petitioner Faubus filed an affidavit

of bias and prejudice under 28 U. S. C. 144, supra,

p. 2. This affidavit stated petitioner Faubus’ belief,

based upon certain occurrences which had taken place

between September 3 and September 10, that District

Judge Davies had a personal prejudice against him

and a personal bias in favor of the plaintiff school

children and the United States, amicus curiae; that

he did not file the affidavit sooner because he was not

made a defendant until September 10; that the affi

davit was filed as soon as possible after petitioners

were made defendants, and the facts of bias and prej

udice became known to petitioner, and as soon as the

affidavit could be considered by Judge Davies

(R . 11-15).3

8 The affidavit made the following allegations:

(1) That between September 3 and September 7 the press

reported that representatives of the Department of Justice had

conferred with Judge Davies, that the United States Attorney

had received F B I reports on the investigation being made pur

suant to Judge Davies’ letter to the United States Attorney of

September 4, and that Judge Davies had conferred with the

Little Bock school superintendent, the United States Attorney,

9

Outlie next day, September 20, the United States,

as amicus curiae, moved the district court to strike

the affidavit of petitioner Faubus on the grounds that

it was not timely filed and that it was leg’ally insuffi

cient (R. 15-16). At the same time, petitioners moved

to dismiss the petition of the United States on juris

dictional grounds (R. 17-18), and for failure to con

vene a three-judge court under 28 U. S. C. 2284 (R.

19).

After hearing argument, the district court, on Sep

tember 20, granted the Government’s motion to strike

the affidavit of bias and prejudice as not legally suffi

cient and not timely filed (R. 35), and granted the

motion of the plaintiff school children for leave to file

their supplemental complaint (R. 36). The court de-

the United States Marshal, and the attorney for the Little Rock

School Board (R. 12-13).

(2) That Judge Davies had received from the United States

Attorney a report of the investigation conducted pursuant to

the Judge’s letter of September 4; that the report contained

hearsay statements indicating that petitioner Faubus had acted

in bad faith, and that on the basis of this report Judge Davies

“has formed an opinion on the merits o f this controversy and

has prejudged the issues to be tried herein” (R. 13).

(3) That in connection with Judge Davis’ order o f Sep

tember 7, denying the school authorities a stay o f his order

o f September 3, Judge Davies had made reference to a state

ment, not in evidence, by the Mayor o f Little Rock that there

was no indication from sources available to him that there

would be any violence in regard to the situation (R. 13-14).

(4) That Judge Davies, in ordering the Department o f Jus

tice to “ intervene” in the action and to file the amicus peti

tion against petitioner Faubus, on the basis o f information

given him by persons not parties to the litigation, “has de

parted from the role of hnpartial arbiter of judicial questions

presented to him and has, in fact, assumed the role o f an advo

cate favoring adverse parties to this affiant” (R. 14).

10

rued petitioners' motions to dismiss the petition of the

United States (R. 58, 60).

As soon as the court ruled upon these motions, and

prior to the introduction of any testimony in support

of the applications of the United States, as amicus

curiae, and of the plaintiff school children for a pre

liminary injunction, counsel for petitioners stated that

he was standing on his motions and thereupon with

drew from the hearing (R. 60-61). At the close of

the testimony presented by the Government in sup

port of its application for a preliminary injunction,

counsel for the plaintiff school children adopted all of

that testimony as testimony on their behalf (R. 61).

At the conclusion of the hearing, the district court

found that the school board’s plan of integration,

approved by the district court and the Court of Ap

peals, “ has been thwarted by the Governor of Arkan

sas by the use of Rational Guard troops” and that

“ there would have been no violence in carrying out

the plan of integration and that there has been no

violence.” The court then granted the application of

the United States, as amicus curiae, for a preliminary

injunction against petitioners (R. 62).

The injunction order, reciting in detail the events

which culminated in its issuance, permanently re

strains petitioners (a) from obstructing or prevent

ing, by means of the Arkansas Rational Guard or

otherwise, eligible Regro students from attending

Central High School, (b) from threatening or coerc

ing the students not to attend that school, (e) from

obstructing or interfering in any way with the carry

ing out and effectuation of the court’s orders of Au

gust 28, 1956, and September 3, 1957, or (d ) from

otherwise obstructing or interfering with the consti

tutional right of the Negro children to attend the

school (R. 64) ,4

On April 28, 1958, the Court of Appeals unani

mously affirmed the order granting the preliminary

injunction.

A R G U M E N T

Petitioners do not challenge on the merits the in

junctive order presently outstanding against them.

Rather, they place principal reliance here on the con

tention that both courts below erred in ruling that the

affidavit of bias was, in fact, not timely filed. We

show below that this contention, as wTell as the re

maining arguments asserted by petitioners, are wholly

without substance, and that the decisions of both

courts below are correct in all respects and warrant

no further review here.

1. Petitioners’ contention (Pet. 12-22) that Gov

ernor Faubus’ affidavit of bias and prejudice was im

properly stricken by the district court is without

merit. The applicable statute, 28 U. S. C. 144, supra,

p. 2, provides in relevant part:

Whenever a party to any proceeding in a

district court makes and files a timely and

sufficient affidavit that the judge before whom

11

4 The injunction also provides that, it shall not be deemed to

prevent petitioner Faubus, as Governor o f Arkansas, “ from

taking any and all action he may deem necessary or desirable

for the preservation o f peace and order, by means of the A r

kansas National Guard, or otherwise, which does not hinder

or interfere with the right of eligible Negro students to attend

the Little Rock Central High School” (R. 65).

12

- the matter is pending has a personal bias or,

prejudice either against him or in favor of any

adverse party, such judge shall proceed no fur

ther therein, but another judge shall be as

signed to hear such proceeding.

The affidavit shall state the facts and the rea

sons for the belief that bias or prejudice exists,

and shall be filed not less than ten days before

the beginning of the term, at which the pro

ceeding is to be heard, or good cause shall be

shown for failure to file it within such time

* * *, [Emphasis added.]

The district court struck the affidavit for two rea

sons: (1) that it was not timely filed, and (2) it was

not legally sufficient (R. 16). The court was correct

on both grounds.5

(a) The affidavit of bias and prejudice, although

based upon events known to have occurred between

September 3 and September 10 (R. 12-14), was not

filed until September 19, 1957, nine days after the

filing of the Government’s application for a prelimi

nary injunction, and one day prior to the date set for

hearing thereon. The delay in filing the affidavit was

particularly significant, for Judge Davies was the only

district judge then available in either District of Ar

kansas (Pet. App. 14a), and, if he had decided in favor

of petitioner Faubus, there would have been insufficient

time to communicate with the Chief Judge of the

Eighth Circuit and for the Chief Judge to arrange to

have another judge come to Little Rock to hear the ap

5 Agreeing with the district court that the affidavit was not

timely filed, the Court o f Appeals found it unnecessary to con

sider its legal sufficiency (Pet. App. 14a).

13

plication for injunction the next morning. A postpone

ment of the hearing would have been inevitable in a

situation where the utmost promptness was required.

In circumstances less urgent than those here, it has

been held that similar affidavits of bias and prejudice

were untimely. See Bommarito v. United States, 61

F. 2d 355 (C. A. 8 ) ; Boivles v. United States, 50 F. 2d

848 (C. A. 4), certiorari denied, 284 IT, S. 648; Lips

comb v. United States, 33 F. 2d 33 (C. A. 8 ); Bishop

v. United States, 16 F. 2d 410 (C. A. 8 ); Rossi v.

United States, 16 F. 2d 712 (C. A. 8) ; Chafin v.

United States, 5 F. 2d 592 (C. A. 4), certiorari denied,

269 U. S. 552.

Petitioners also argue (Pet. 14) that the affidavit

was timely because it was filed within the twenty

days provided by the rules for an answer to the peti

tion. The short and dispositive answer to this con

tention is that, of course, an application for a pre

liminary injunction may be heard, as it was here,

before expiration of the time to answer. ISTor is the

delay excused by the fact that petitioners chose to

retain private counsel rather than to utilize the serv

ices of the Attorney (ten era! of Arkansas.6 Certainly,

petitioners cannot delay selecting counsel and use that

delay as an excuse for not filing the affidavit of bias

and prejudice as soon as the alleged facts on which

8 Since petitioners contended that the Government’s amicus

petition amounted to a suit against the State of Arkansas

(R. 17-18), there can be no doubt that the Arkansas Attorney

General was authorized to represent them. See Arkansas

Statutes, 1947 (1956 Replacement), 12-712.

14

it is based come to their attention. Cf. Hibdon v.

United States, 213 F. 2d 869 (C. A. 6).

Equally untenable is petitioners’ contention (Pet.

15) that, even if the affidavit had been filed promptly,

it could not have been considered by Judge Davies

because he was not then present in Little Rock. The

record does not show the dates of Judge Davies’ ab

sence from Little Rock. Even it it be assumed, how

ever, that he was away from Little Rock during most

of the period between September 10 and 20, there is

no reason to think that, if the affidavit had been

promptly filed, it would not have been brought to his

attention, either by telephone or by mail, in time for

him to mile on it, and, if he had deemed it sufficient

in law, to have made arrangements with the Chief

Judge of the Eighth Circuit for the assignment of

another judge to hear the matters set for September

20. But, by not filing the affidavit until September

19, petitioner Faubus made it impossible to make ar

rangements for the designation of another judge with

out a delay in the hearing. Clearly, in these circum

stances, both courts below were correct in concluding

that the affidavit was not timely filed.

(b) Moreover, the affidavit was correctly stricken

because not a single allegation in it could reasonably

justify an inference of personal bias by Judge Davies

against Governor Faubus.

Paragraphs (1) through (4) of the affidavit allege,

in substance, that Judge Davies had conferred with

the United States Attorney and other representatives

of the Department of Justice about the case (R. 12-

13). This allegation can hardly constitute a legally

15

sufficient ground to support an affidavit of bias and

prejudice. Indeed, identical allegations have been

characterized as “ frivolous” in Craven v. United

States, 22 F. 2d 605, 607 (C. A. 1), certiorari denied,

276 U. S. 627, and United States v. Gilbert, 29 F.

Supp. 507, 509 (S. D. Ohio). See Scott v. Beams,

122 F. 2d 777, 788 (C. A. 10), certiorari denied, 315

U. S. 809, where the court held that an affidavit of

bias and prejudice asserting that the judge had dis

cussed issues in the case with an Assistant United

States Attorney, in the absence of opposing counsel,

“was not a fact showing bias and prejudice.” See,

also, United States v. Onan, 190 F. 2d 1 (C. A. 8).

Paragraphs (2) and (5) of the affidavit also assert

in substance that Judge Davies had received FBI

reports from the United States Attorney containing

hearsay statements, and that, on the basis of these

reports, Judge Davies “has formed an opinion on the

merits of this controversy and has prejudged the

issues to be tried herein” (R. 12-13). The mere re

ceipt of the FB I reports by the district court is, of

course, no basis for inferring prejudice. The dis

trict court was entitled to know what the facts were

with respect to alleged interference with its previous

orders (see R. 3-4), and, in a matter going to the

integrity of the judicial process, the court was clearly

entitled to call upon the law officers of the Govern

ment for assistance. Cf. Universal Oil Products Co.

v. Boot Refining Co., 328 U. S. 575, 581. The bare

allegation that Judge Davies had prejudged the is

sues on the basis of the FB I reports is wholly insuffi

cient under the statute. Price v. Johnston, 125 F. 2d

16

806, 812 (C. A. 9), certiorari denied, 316 U. S. 677.

In re Lisman, 89 F. 2d 898 (C. A. 2) ; Henry v. Speer,

201 Fed. 869, 872 (C. A. 5).

Paragraph (6) of the affidavit states that the

district court, in denying an application by the Little

Rock school authorities for a stay of its order of Sep

tember 3, referred to a statement not in evidence made

by the Mayor of Little Rock (R. 13-14). Even if it

be conceded arguendo that it was error for the court

to refer to a statement outside the record, the allega

tion is still legally insufficient. Nothing in the state

ment referred to, or in the fact that it was cited by

the district judge, supports an inference of personal

prejudice against petitioner Faubus. In any event,

a legal error by a judge would not be a basis for his

disqualification. Berger v. United States, 255 U. S.

22, 31; Palmer v. United States, 249 F. 2d 8 (C. A.

10); Littleton v. DeLashmutt, 188 F. 2d 973, 975

(C. A. 4).

Finally, paragraph (7) of the affidavit alleges that

the district court, on its own initiative, directed the

Attorney General, as amicus curiae, to file an appli

cation for an injunction against petitioner Faubus to

prevent interferences with the court’s order (R. 14).

In this regard, there can be no question that the court

was acting well within its authority. See, infra,

pp. 17-20.

It is clear, therefore, that each and every allega

tion in the affidavit was plainly insufficient as a matter

of law and that, on this ground also, it was properly

stricken by the district court.

17

2. Petitioners further contend here (Pet. 22-28),

as they did in both courts below, that the district

court lacked authority to permit the United States,

as amicus curiae, to file an application bringing in

petitioners as additional parties defendant, and seek

ing injunctive relief against them. This is purely

academic, since, as the Court of Appeals properly

noted (Pet. App. 15a-16a), the same relief which

was sought by the Government’s amicus petition was

sought by the supplemental complaint of the plaintiff

school children. Nevertheless, we show that the con

tention is wholly groundless.

Although it is true that ordinarily an amicus curiae

appears in a case only to advise the court on the issues

of law involved, there is no legal requirement that the

role of an amicus be so limited. Particularly where,

as here, a matter of public interest in the proper ad

ministration of justice was presented by petitioners’

forcible obstruction to the carrying out of the district

court’s orders of August 28 and September 3, it was

entirely proper for the district court to call upon the

Government’s law officers to assist it in resolving the

issues involved, even though this required the filing

of a petition seeking injunctive relief and the presen

tation of evidence in support of the petition.

In Universal Oil Products Go. v. Boot Refining Co.,

328 U. S. 575, 581, involving a question of the subver

sion of the due administration of justice by fraud, this

Court said: “ After all, a federal court can always call

on law officers of the United States to serve as amici.”

On the remand of that ease to the Court of Appeals,

that court authorized the Attorney General to appear

18

in the ease as amicus curiae and authorized a special

assistant to the Attorney General to appear for the

United States, as amicus curiae. The special assist

ant, with the approval of the court, filed a statement

of facts (which was the equivalent of a pleading) and

presented evidence before the Court of Appeals. Root

Ref,ning Co. v. Universal Oil Products Co., 169 F.

2d 514, 519-521, 537 (C. A. 3), certiorari denied, 335

U. S. 912. In disposing of the objection of one of the

parties that the court lacked jurisdiction to conduct

such proceedings, the court said: “ This argument com

pletely ignores the inherent power of a court to in

quire into the integrity of its own judgments. * * *

The matter is not one of merely private concern sub

ject to the action or inaction of the litigants, but is

one of vast public importance, so that it becomes im

material that the injured party may have been derelict

in bringing the fault to the court’s attention.” (169

F. 2d at 521-522.)

Similarly, in Securities and Exchange Commission

v. United States Realty <& Improvement Co., 310 U. S.

434, this Court held that where an issue of public

interest was involved it was proper for the Securities

and Exchange Commission, as an agency of the Gov

ernment, to intervene in a ease and seek affirmative

relief by way of vacating a prior order made by the

court.7 Again, in The Exchange, 7 Cr. 116, 118-119,

where another important public interest was involved,

7 The participation o f the Securities and Exchange Commis

sion in that case is set forth in detail in the earlier opinion

o f the Court o f Appeals, In re United States Realty <& Im

provement Go., 108 F. 2d 794,796 (C. A. 2).

19

the United States Attorney filed a “ suggestion” that

an attachment against a vessel be quashed and sub

mitted evidence to justify such relief. See, also A. B.

Dick Go. v. Marr, 197 F. 2d 498, 501-502 (C. A. 2),

certiorari denied, 344 IT. S. 878; Kasper v. Brittain,

245 F. 2d 97 (C. A. 6), certiorari denied, 355 IT. S.

834; Helmbright v. John A. Gebelein, Inc., 19 F. Supp.

621, 623 (D. Md.).

Moreover, the statutes prescribing the authority of

the Attorney General authorized him to appear in this

case and present the paramount interest of the Gov

ernment in contesting petitioners’ forcible obstruction

of the court’s orders. Congress, in 5 G. S. C. 309,

has authorized the Attorney General, “ whenever he

deems it for the interest of the United States,” to con

duct and argue, either in person or through any officer

of the Department of Justice, “ any case in any court

of the United States in which the United States is

interested * * Similarly, 5 U. S. C. 316 provides

that the Attorney General may send any officer of the

Department of Justice “ to attend to the interests of

the United States” in any suit pending in any of the

courts of the United States.

The authority given the Attorney General by these

statutes is obviously not limited to cases in which the

United States is a formal party. As stated in Booth

v. Fletcher, 101 F. 2d 676, 681-682 (C. A. D. C.),

certiorari denied, 307 U. S. 628:

* * * [5 U. S. C. 309] does not limit his [the

Attorney General’s] participation or the par

ticipation of his representatives to cases in

which the United States is a party; it does not

20

direct how he shall participate in such cases;

it gives him broad, general powers intended to

safeguard the interests of the United States

in any case, and in any court of the United

States, whenever in his opinion those interests

may be jeopardized. * * *

These provisions “ grant the Attorney General broad

powers to institute and maintain court proceedings in

order to safeguard national interests.” United

States v. California, 332 U. S. 19, 27. See, also,

Sanitary District v. United States, 266 U. S. 405,

425-426; Kern Biver Company v. United States, 257

U. S. 147, 154-155; New York v. New Jersey, 256

U. S. 296, 303-304, 307-308.

In addition, the district court had authority to

entertain the Government’s amicus petition for an

injunction against petitioners to prevent their forc

ible obstruction of the court’s decrees as an exercise

of the district court’s ancillary jurisdiction to ef

fectuate its orders and prevent their frustration.

28 U. S. C. 1651; Steelman v. All Continent Co., 301

U. S. 278, 288-289; Dugas v. American Surety Co.,

300 U. S. 414, 428; Local Loan Co. v. Hunt, 292 U. S.

234, 239; Julian v. Central Trust Company, 193

U. S. 93,112.

Petitioners suggest (Pet. 25) that the United

States had no interest in this case because the “ action

was one for the protection of private rights,” i. e.,

of the plaintiff school children. But this suggestion

completely ignores the vital interest the Federal

Government has in seeing that the due performance

by the federal courts of their constitutional function

under Art. I l l is not obstructed by force.

21

Finally, petitioners assert (Pet. 22-23) that the

Government’s amicus petition was unnecessary to

uphold the district court’s authority because there

was an adequate remedy by way of contempt pro

ceedings. But even if petitioners could have been pro

ceeded against for contempt, surely that was not an

exclusive remedy and the court had authority to invoke

the remedy utilized here.

Accordingly, the district court had jurisdiction to

enjoin petitioners from forcibly obstructing the court’s

order. Whether the district court had undertaken to

do this on its own motion, or chose (as it did) to call

upon the law officers of the Government for assistance,

and whether the Government’s pleading for that pur

pose had been by way of an amicus petition (as it

was), or by formal intervention in the case, or by

filing an independent action against petitioners, is

wholly immaterial. The injunction was proper, and

petitioners were not prejudiced by the choice of one

particular style of pleading rather than another. See

United States v. United Mine Workers of America,

330 U. S. 258, 295-301; Kasper v. Brittain, 245 F. 2d

97 (C. A. 6), certiorari denied, 355 IT. S. 834.8

8 Petitioners also contend that the lower court erred in pro

ceeding to trial on plaintiffs’ Supplemental Complaint which

was filed without notice to petitioners (Pet. 28-29). But, in

the first place, no specific objection to lack of notice was made,

either in the district court, when the plaintiffs moved to file

the Supplemental Complaint (see R. 35-36), or in the court

of appeals. Secondly, there could be no possible prejudice,

since the Supplemental Complaint was, in substance, a repeti

tion of the matters contained in the Government’s amicus

petition, o f which petitioners had due notice.

22

CONCLUSION

For the reasons stated, it is respectfully submitted

that the petition for a writ of certiorari should be

denied.

J. L ee R ankin ,

Solicitor General.

George Cochran D oiib,

Assistant Attorney General.

Morton H ollander,

Seymour F arber,

Attorneys.

A ugust 1958.

U. S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE: 1958